Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) can hydrolyze many peptides and plays a central role in controlling blood pressure. Moreover, ACE overexpression in monocytes and macrophages increases resistance of mice to tumor growth. ACE is composed of two independent catalytic domains. Here, to investigate the specific role of each domain in tumor resistance, we overexpressed either WT ACE (Tg-ACE mice) or ACE lacking N- or C-domain catalytic activity (Tg-NKO and Tg-CKO mice) in the myeloid cells of mice. Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice exhibited strongly suppressed growth of B16-F10 melanoma because of increased ACE expression in macrophages, whereas Tg-CKO mice resisted melanoma no better than WT animals. The effect of ACE overexpression reverted to that of the WT enzyme with an ACE inhibitor but not with an angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist. ACE C-domain overexpression in macrophages drove them toward a pronounced M1 phenotype upon tumor stimulation, with increased activation of NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and decreased STAT3 and STAT6 activation. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) is important for M1 activation, and TNFα blockade reverted Tg-NKO macrophages to a WT phenotype. Increased ACE C-domain expression increased the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and of the transcription factor C/EBPβ in macrophages, important stimuli for TNFα expression, and decreased expression of several M2 markers, including interleukin-4Rα. Natural ACE C-domain–specific substrates are not well-described, and we propose that the peptide(s) responsible for the striking ACE-mediated enhancement of myeloid function are substrates/products of the ACE C-domain.

Keywords: melanoma, macrophage, NF-kappa B (NF-KB), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), cellular immune response, ACE, Macrophage polarization, STAT

Introduction

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 is part of the renin–angiotensin system and plays a central role in the control of blood pressure and other aspects of cardiovascular physiology (1). Unlike renin, which is very limited in tissue distribution and enzymatic specificity, ACE is expressed by the great majority of tissues and is enzymatically promiscuous. Because of this, ACE can hydrolyze many bioactive peptides and has several physiologic functions in addition to blood pressure control (1).

Our laboratory reported that the overexpression of ACE in monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils markedly enhanced the response of these cells to immune challenge (2, 3). For example, mice termed ACE 10/10, which overexpress ACE in monocytes and macrophages, have substantially greater resistance to tumor growth, bacterial infection, and Alzheimer's disease–like cerebral plaque deposition than WT mice (4–6). At present, the mechanism by which ACE overexpression induces such a marked increase in immune behavior is poorly understood. Structurally, ACE is a single peptide chain, but it is composed of two functionally independent catalytic domains, termed the N- and C-domains (1). Although the domains are the result of an ancient gene duplication and are structurally homologous, there are important differences in substrate specificity (1, 7). By investigating the effect of each of the two ACE domains on immune function, we may obtain important information as to which substrates of ACE are responsible for the enhancement of myeloid immune function observed with ACE overexpression. To investigate the specific role of the ACE N- and C-domains in tumor resistance, we generated three transgenic mouse models that overexpress ACE in macrophages: the Tg-ACE mice overexpress WT ACE having both active domains, whereas the Tg-NKO mice and the Tg-CKO mice overexpress a full-length ACE in which point mutations have eliminated catalytic activity of the N- or C-domain, respectively. We found that ACE overexpression by the macrophages of Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice strongly suppressed the growth of melanoma. In contrast, macrophages from Tg-CKO mice, in which macrophages overexpress ACE with a functional N-domain, resist melanoma no better than WT mice. Macrophages from Tg-ACE or Tg-NKO mice showed up-regulation of M1 signaling, including activation of TNFα, NF-κB, and STAT1, while down-regulating the M2 signals STAT3 and STAT6. This appears to reprogram these cells toward a more “classically” activated M1 phenotype that is responsible for the enhanced tumor resistance. Thus, our studies show again that the overexpression of ACE by macrophages is a powerful mechanism to enhance resistance to melanoma growth and that this is due to the catalytic activity of the ACE C-domain, which biochemically drives macrophages to a more aggressive phenotype.

Results

Characterization of transgenic mice for ACE expression

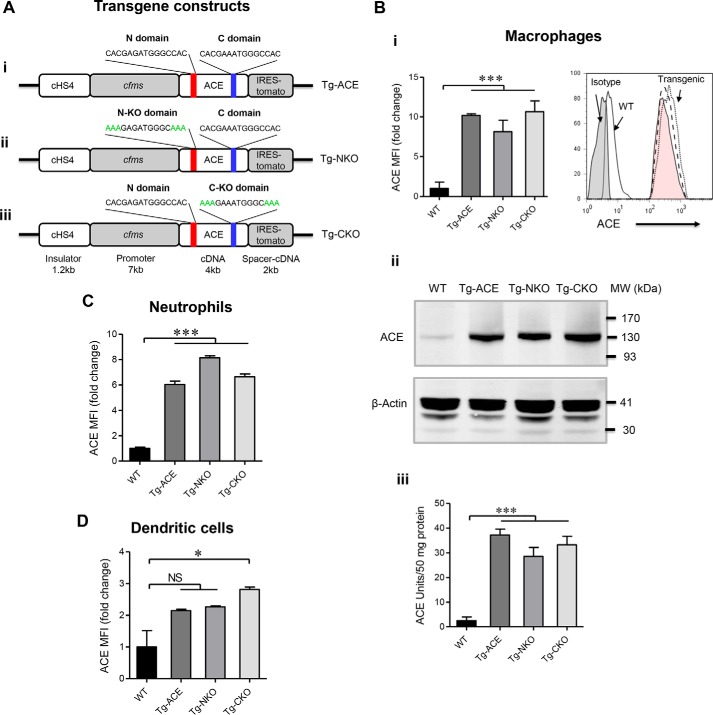

Mice were made transgenic for one of three different ACE constructs in which ACE cDNA is under the control of the mouse c-fms promoter (Fig. 1A). This promoter targets myeloid cells. The three mouse lines overexpress a full-length ACE protein with either 1) both active catalytic domains (called Tg-ACE mice), 2) ACE lacking N-domain activity (called Tg-NKO), or 3) ACE lacking C-domain activity (called Tg-CKO). The ACE mutations used to eliminate N- or C-domain catalytic activity prevent the targeted domain from binding zinc as previously described (7, 8).

Figure 1.

Characterization of transgenic mice. A, schematic diagram of the c-fms–ACE cDNA constructs used for generating transgenic mice. The figure shows the N- and C-domain zinc-binding regions (panel i), as well as the mutations present in the N-KO and C-KO constructs (panels ii and iii). Such mutations convert His361 and His365 (N-domain) or His959 and His963 (C-domain) to Lys, which does not bind zinc. cHS4 is a chromatin insulator. B, determination of ACE expression in macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were collected 4 days after i.p. thioglycolate injection. Panel i, FCM analysis (Tg-ACE; Tg-NKO (pink tinted); Tg-CKO). The data presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Panel ii, Western blotting. Panel iii, ACE activity assay (n = 5). C, FCM analysis for ACE expression in blood neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+). D, FCM analysis for ACE expression in blood dendritic cells (CD11b+CD11c+). Tg-ACE, both ACE domains are active; Tg-NKO, the ACE C domain is active; Tg-CKO, the ACE N-domain is active. One-way ANOVA (nonparametric) was used for statistical analysis. *, p ≤ 0.05; ***, p ≤ 0.0005.

Founder mice were screened for ACE overexpression in macrophages, and mice homozygous for transgene expression were made by mating heterozygotes. By flow cytometry (FCM), peritoneal macrophages from transgenic mice express 8–10-fold more ACE than equivalent cells from WT animals (Fig. 1B, panel i). As measured by Western blotting or analysis of ACE activity, transgenic macrophages express 11–14-fold higher levels of ACE as compared with WT macrophages (Fig. 1B, panels ii and iii). In transgenic mice, neutrophils have a 6–8-fold increase in ACE expression by FCM (Fig. 1C). Splenic dendritic cells from Tg-CKO mice have a mild increase in ACE expression (∼3-fold), whereas no significant difference from WT was observed in the Tg-ACE or Tg-NKO dendritic cells (Fig. 1D). No differences in ACE expression by lymphocytes or in several organs (lung, kidney, liver, and spleen) from levels in WT mice were observed, indicating normal endogenous ACE gene function (Fig. S1). The number of peripheral monocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and dendritic cells was not different from WT levels (Fig. S2).

ACE C-domain is predominately responsible for macrophage anti-tumor response

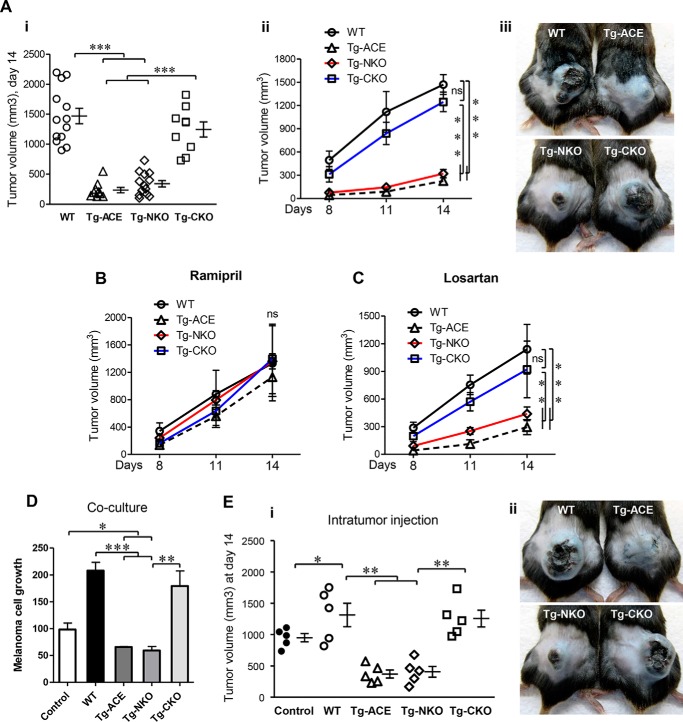

To study tumor growth, we injected 1 × 106 B16-F10 melanoma cells intradermally into WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO mice. B16-F10 is an aggressive mouse melanoma that produced tumor nodules in all mice (9). Tumor volume was measured on days 8, 11, and 14 after injection (Fig. 2A). Tumor growth was profoundly less in Tg-ACE mice as compared with WT mice throughout the study. Tumor volume in Tg-ACE mice at day 14 was 235 ± 44 mm3 as compared with 1469 ± 128 mm3 in WT mice (Fig. 2A, p ≤ 0.0005). Despite having only one active catalytic domain, Tg-NKO mice suppressed tumor growth (339 ± 53 mm3 tumor volume, p ≤ 0.0005). In contrast, Tg-CKO mice showed significantly lower tumor resistance (1244 ± 125 mm3 tumor volume). Thus, an active ACE C-domain appears critical for tumor suppression. To confirm the role of ACE in tumor resistance, we treated mice with the ACE inhibitor ramipril for 7 days prior to tumor inoculation and during the experiment. ACE inhibition eliminated the difference in tumor growth between transgenic and WT mice (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Melanoma growth in mice. A, after intradermal injection of B16-F10 melanoma cells (106 cells/mouse), tumor volume was determined on days 8 and 11 and at sacrifice on day 14. Panel i, final tumor volume at day 14. Panel ii, tumor volume over time (N ≥ 9). Panel iii, representative images of tumors at day 14. B, tumor volume with ramipril treatment. C, tumor volume with losartan treatment. B and C, mice were treated with ramipril (40 mg/liter) or losartan (600 mg/liter) in drinking water for 7 days before tumor cell injection. The drugs were given continuously until the end of the experiment. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. ns, nonsignificant; **, p ≤ 0.005; ***, p ≤ 0.0005. D, effect of ACE overexpressing macrophages on melanoma cell growth in co-culture. B16-F10 cells were cultured in 24-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 104/well. Peritoneal macrophages from WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, or Tg-CKO mice were co-cultured in Transwell inserts (0.4-μm pore size) at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells. After 48 h, B16-F10 cell growth was determined using Cell Titer Glow (n = 4). E, measurement of melanoma growth in vivo following intratumor injection of macrophages. Melanoma tumors were elicited in WT mice by intradermal injection of B16-F10 cells (106 cells). After 1 week, tumors were visualized in all animals (∼350 mm3). The tumors were then injected with 3 × 106 peritoneal macrophages originating from either WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, or Tg-CKO mice in 50 μl of PBS. Panel i, tumor volume at day 14. Panel ii, representative images of tumors at day 14. One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.005; ***, p ≤ 0.0005.

Other than macrophages, ACE expression is increased in the neutrophils of transgenic mice. To examine whether neutrophil ACE overexpression plays a role in tumor resistance, tumor growth was assessed in neutrophil-depleted mice. Groups of WT and Tg-ACE mice were treated with anti-PMN antibody for neutrophil depletion (5), but elimination of neutrophils did not significantly reduce the tumor resistance of Tg-ACE mice versus WT (Fig. S3, p < 0.005), indicating that neutrophils do not contribute to tumor regression in transgenic mice.

Ang II is an important product of ACE C domain that exerts most effects following binding to cell surface AT1 receptors (10, 11). To study the role of the Ang II/AT1 axis in vivo, similar experiments were performed with losartan, an angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonist, to investigate the involvement of this receptor pathway (5). However, we found no significant effect of losartan on tumor growth (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that although ACE activity is critical to the phenotype, the angiotensin II AT1 receptor pathway is not involved in the increased tumor suppression seen in Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice (Fig. 2C). To examine the role of other angiotensin peptides, Tg-ACE mice were treated with the renin inhibitor aliskiren throughout the experiment. The mice were then implanted with B16-F10 tumor, as described above. Aliskiren treatment showed no effect on tumor growth in Tg-NKO versus WT mice (Fig. S4), indicating that no angiotensin peptides participate in tumor resistance in Tg-NKO mice. Further, blocking other known ACE C-domain peptide pathways, such as bradykinin/B2R and substance P/NK1R, had no effect on tumor growth in mice (Fig. S4).

ACE C-domain overexpressing macrophages suppress melanoma cell viability and tumorigenicity

To directly assess the effect of ACE overexpressing macrophages on melanoma growth, we co-cultured B16-F10 melanoma cells with macrophages isolated from WT and transgenic mice. Melanoma cells were cultured in 24-well plates, whereas macrophages were cultured in a Transwell insert. After 48 h, the viability of the melanoma cells was determined by a CellTiter-Glo assay. There was approximately a 35% reduction of melanoma cell growth when co-cultured with Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO macrophages as compared with control without co-culture (Fig. 2D, p < 0.05). In contrast, co-culture of WT and Tg-CKO macrophages resulted in a doubling in growth of the melanoma cells as compared with the control (p < 0.005).

For in vivo study, control WT mice were implanted with B16-F10 melanoma which, by 1 week, resulted in visible tumors of ∼350 mm3. Macrophages were then isolated from nontumor bearing WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO mice, and 3 × 106 cells were injected into the tumors of the control mice on day 7. Tumor size was measured 7 days after macrophage injection (day 14). The tumor-bearing mice receiving Tg-ACE or Tg-NKO macrophages had significantly smaller tumors (370 ± 64 and 405 ± 84 mm3) as compared with equivalent mice receiving Tg-CKO or WT macrophages (1139 ± 175 and 1315 ± 186 mm3) (Fig. 2E, p < 0.005). This in vitro study suggests that macrophages overexpressing the ACE C-domain release diffusible component(s) that suppress tumor cell growth.

ACE C-domain up-regulation stimulates macrophages to an M1 phenotype

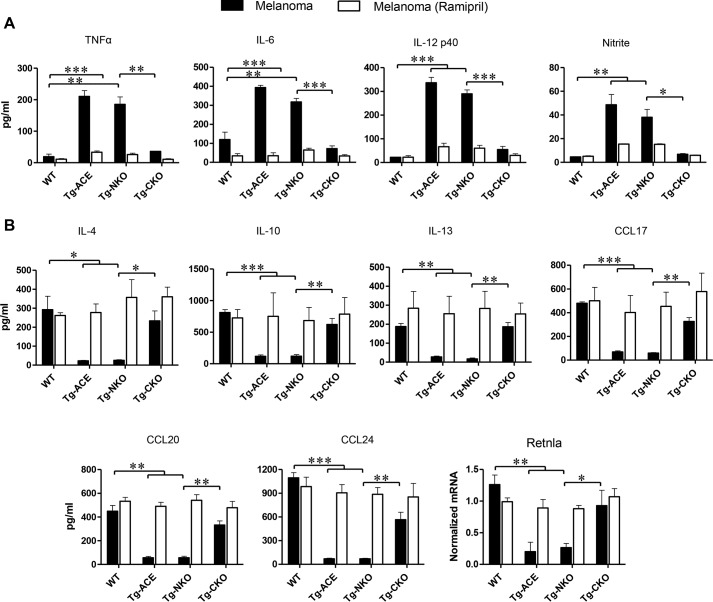

To investigate whether ACE affects M1 versus M2 activation of macrophages in response to tumor challenge, we cultured thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from WT and transgenic mice with the supernatant from cultured B16-F10 cells. After 72 h of tumor conditioning, cytokine levels in the supernatant were measured by ELISA. In response to B16 supernatant conditioning, Tg-ACE macrophages were phenotypically more pro-inflammatory (M1-like) than WT macrophages. Specifically, the production of M1 markers such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-12p40, and nitric oxide was significantly higher in Tg-ACE macrophages as compared with WT. In contrast, the expression of M2 markers including IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, CCL17, CCL20, CCL24, and Retnla (Fizz1) was significantly lower in Tg-ACE macrophages as compared with WT macrophages (Fig. 3). Tg-CKO mice have a cytokine profile very similar to that of WT mice. In contrast, macrophages from Tg-NKO had a macrophage profile similar to Tg-ACE cells, supporting the idea that ACE C-domain activity is responsible for the M1-like activation of macrophages upon tumor challenge. To verify the catalytic role of ACE, we examined M1 versus M2 macrophage polarization following ramipril treatment of mice for 7 days before macrophage isolation. The inhibitor was also added in vitro (1 μm) throughout the experiment. This showed that ACE inhibition eliminated any differences between WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

M1 versus M2 macrophage activation. Thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated from WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO mice and cultured in 6-well plates (3 × 106 cells/well). To challenge with tumor factors, macrophages were co-cultured with fresh supernatant of B16-F10 cells every 24 h for 72 h. The final 24 h, supernatants were collected for cytokine and nitrite measurement. To examine the role of ACE, similar experiments were done in the presence of ramipril. Cell production of cytokines was assessed by ELISA. Nitric oxide (nitrite) was determined by the Griess Assay (Promega). The expression of Retnla was determined by qRT-PCR. A, pro-inflammatory markers TNFα, IL-6, IL-12, and nitrite. B, anti-inflammatory markers IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, CC17, CCL20, CCL24, and Retnla (n = 4/group). One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.005; ***, p ≤ 0.0005).

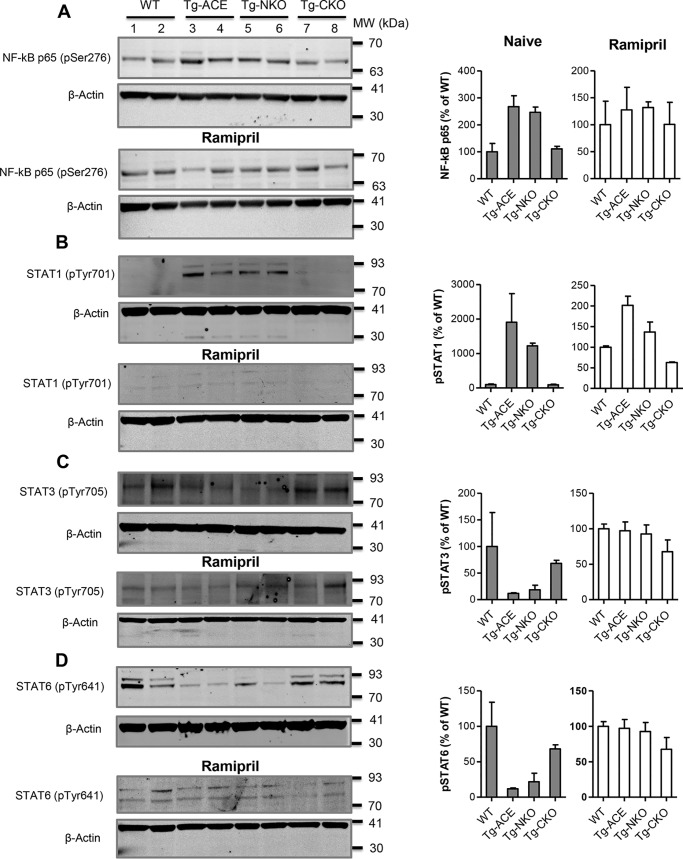

The ACE C-domain induces activation of NF-κB and STAT1

Alterations in STAT and NF-κB pathways play a major role in determining the M1 versus M2 polarization of macrophages (12). To study whether these pathways are affected by ACE up-regulation and, if so, by which ACE domain, macrophages were isolated from WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO mice and conditioned for 3 days with supernatant from B16-F10 cells. The macrophages were then lysed to assess the levels of phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (pSer276), STAT1 (pTyr701), STAT3 (pTyr705), and STAT6 (pTyr641) by Western blotting. We found increased phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 (∼2.5-fold) and STAT1 (19-fold) in Tg-ACE macrophages as compared with WT cells (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, Tg-ACE macrophages showed decreased phosphorylation of STAT3 (8.4-fold) and STAT6 (4.6-fold) (Fig. 4, C and D). Tg-NKO macrophages were similar in phosphorylation pattern to Tg-ACE cells, whereas Tg-CKO macrophages resembled WT macrophages (Fig. 4). This again indicates a critical role for the ACE C-domain in stimulating an M1-like phenotype. To verify the role of ACE, we measured phosphorylation levels in cells treated with ramipril. ACE inhibition eliminated the differences between WT and transgenic macrophages for NF-κB and STAT activation.

Figure 4.

Measurement of NF-κB and STATs activation. Following a 72-h culture with B16-F10 melanoma supernatant, macrophage phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT6 was determined by Western blotting. A, phosphorylated NF-κB p65. B, phosphorylated STAT1. C, phosphorylated STAT3. D, phosphorylated STAT6. For ACE inhibition, the mice were administrated ramipril for 7 days before thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages isolation. Ramipril was also added to macrophage cultures (5 μm) for continuous blockade of ACE. The protein band intensity was quantified by Odyssey version 3.0 software. After adjusting values for loading using the β-actin band, the data are presented as percentages of WT values for both naïve and ramipril treatment (n = 4/group).

To determine the early effects of ACE C-domain overexpression on M1 macrophage activation, we examined the pro-inflammatory signals TNFα, phospho-NF-κB p65, and phospho-STAT1 at 12 and 24 h following melanoma challenge. At 12 h, TNFα, phospho-NF-κB p65, and phospho-STAT1 in Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO macrophages averaged 3.6-fold the levels in WT cells. In contrast, Tg-CKO averaged 1.2-fold. The differences at 24 h were even more pronounced where the values for Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO averaged 5-fold those of WT, whereas Tg-CKO was equivalent to WT (Fig. S5).

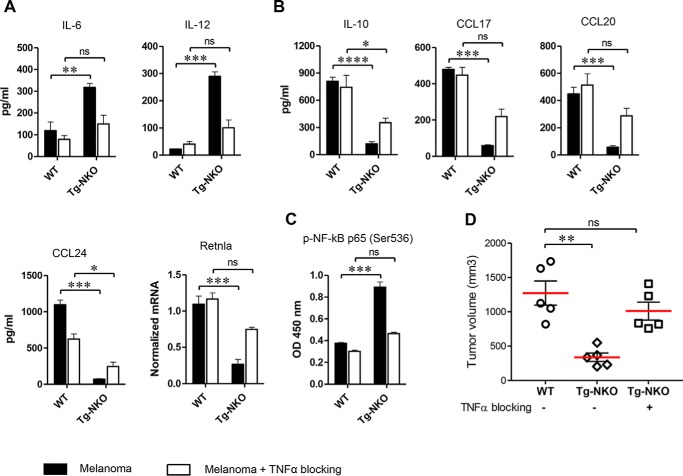

TNFα is critical for increased M1 polarization by the ACE C-domain

TNF signaling is thought to play a crucial role in M1 activation of macrophages, at least in part by counterbalancing stimuli for M2 activation (13, 14). To test the role of TNFα in ACE-mediated tumor resistance, we examined Tg-NKO macrophage activation by melanoma-conditioned medium in the presence of anti-TNFα antibody. This significantly suppressed M1 activation of Tg-NKO macrophages, as indicated by a substantial reduction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12 and an increase of several anti-inflammatory markers including IL-10, CCL17, and CCL20 (Fig. 5, A and B). Further, TNFα blockade eliminated the difference in NF-κB activation between Tg-NKO and WT mice (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Role of TNFα in enhanced M1 macrophage polarization by ACE C-domain up-regulation. Perityoneal macrophages were isolated from WT and Tg-CKO mice and conditioned 24 h with supernatant from B16-F10 melanoma (as described in Fig. 3A) in the presence of TNFα neutralizing antibody (500 ng/ml). The production of cytokines was determined in the macrophage supernatant by ELISA (n = 4/group). Cellular expression of Retnla was measured by qRT-PCR. A, pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12. B, Anti-inflammatory markers IL-10, CC17, CCL20, CCL24, and Retnla. C, measurement of NF-κB p65 phosphorylation (Ser536) by ELISA (n = 4 for A–C). D, determination of melanoma growth with TNFα blockade. Either WT or Tg-NKO macrophages were injected intratumorally in WT mice, as described in Fig. 2E. For TNFα blockade, Tg-NKO macrophages were pretreated for 24 h with TNFα neutralizing antibody before intratumor injection, and then after injection, these mice were given the TNFα inhibitor C87 (12.5 mg/kg) by i.p. injection on days 0 and 3 (n = 5). Final tumor volume was measured 1 week after intratumor injection (day 14). One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.005; ***, p ≤ 0.0005).

To study tumor growth, B16-F10 melanoma was implanted in WT mice. After 1 week, WT and Tg-NKO macrophages were isolated from non–tumor-bearing mice. Although all the cells were incubated overnight, the Tg-NKO cells were incubated either with or without anti-TNFα antibody. The cells were then injected into the B16-F10 tumors. Tumor volume was measured on day 14 when the mice were sacrificed. The tumors injected with Tg-NKO macrophages were significantly smaller than the tumors injected with WT macrophages (Fig. 5D). However, overnight incubation of the Tg-NKO cells with anti-TNFα antibody reverted the tumor suppressive ability of Tg-NKO macrophages to that of WT macrophages.

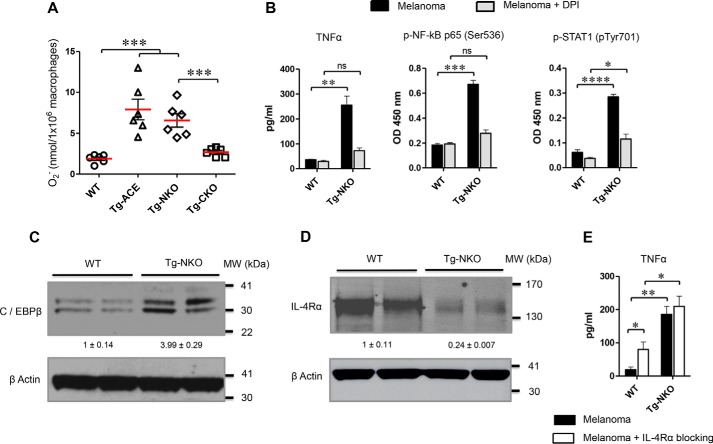

How does ACE C-domain overexpression increase TNFα production?

ACE overexpression strongly enhances the oxidative response of neutrophils (5). To study whether ACE overexpression also increases macrophage oxidative responses and induces TNFα, peritoneal macrophages were challenged with 10 μm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 10 min, and then superoxide production was determined by cytochrome c reduction. ACE overexpression strongly enhanced superoxide production in Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO macrophages as compared with WT macrophages (3.8- and 3.15-fold; Fig. 6A). Again, this phenotype depends on ACE C-domain activity because superoxide levels in Tg-CKO macrophages were very similar to WT macrophages (Fig. 6A). To understand whether the ACE C-domain induces M1 macrophage activation through an ROS-mediated pathway, we challenged macrophages with melanoma conditioned medium in the presence of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), an inhibitor of ROS production by flavoenzymes. This significantly decreased production of TNFα by Tg-NKO macrophages as opposed to WT macrophages, which showed no such effect (Fig. 6B). ROS inhibition also strongly down-regulated NF-κB and STAT1 expression in Tg-NKO macrophages (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Mechanism of TNFα regulation by the ACE C-domain. A, measurement of superoxide generation by WT and transgenic macrophages (Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO). Peritoneal macrophages were isolated and challenged with 10 μm PMA. After 10 min, superoxide generation was measured by cytochrome c reduction. B, to study the role of ROS in macrophage polarization, macrophages were treated with B16-F10 supernatant for 24 h in the presence of DPI, and then the production of TNFα, phospho-NF-κB p65, and phospho-STAT1 was measured by ELISA (n = 4). C, measurement of C/EBPβ by Western blotting. D, measurement of IL-4Rα by Western blotting. E, for blocking IL-4Rα in macrophages, the cells were conditioned with melanoma supernatant for 24 h in the presence of IL-4Rα neutralizing antibody (500 ng/ml). TNFα was then measured by ELISA.

The CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) also plays an important role in the production of TNFα (15, 16). To test whether ACE overexpression changes C/EBPβ expression, we measured levels of this transcription factor in Tg-NKO and WT macrophages. Tg-NKO macrophages showed a 4-fold increase in the levels of C/EBPβ as compared with WT cells (Fig. 6C).

In the tumor microenvironment, the IL-4/IL-13 signaling pathway is critical for M2 activation of macrophages through STAT6 activation (12, 17). ACE C-domain overexpression reduced the level of IL-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) in Tg-NKO macrophages (Fig. 6D). To examine whether IL-4Rα inhibition enhances TNFα expression by reducing inhibitory effects on NF-κB and STAT1, we compared TNFα production in WT and Tg-NKO macrophages in the presence of IL-4Rα neutralizing antibody. Following challenge with melanoma supernatant, IL-4Rα neutralization significantly increased production of TNFα in WT macrophages, although not to the levels present in Tg-NKO cells (Fig. 6E). There were also lower levels of M2 markers in WT macrophages following IL-4Rα blockade (Fig. S6). In contrast, anti-IL4Rα treatment of Tg-NKO macrophages resulted in no significant change in TNFα expression.

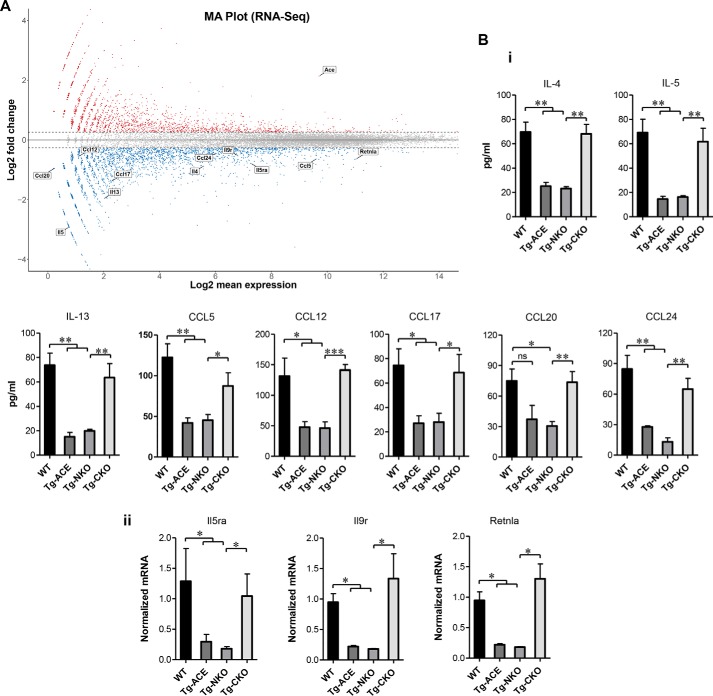

ACE C-domain down-regulates basal expression of several M2 genes

To understand further how ACE affects macrophage phenotype, we performed RNA-Seq of macrophages isolated from WT and Tg-ACE mice. This identified differential expression of many genes in ACE overexpressing macrophages as compared with WT (Fig. 7A). ACE up-regulation suppressed basal expression of several important genes previously linked to tumor-associated macrophage M2 polarization, including down-regulation of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, Ccl5, Ccl12, Ccl17, Ccl20, Ccl24, IL-5ra, IL-9r, and Retnla (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Basal expression of M2 macrophage markers. A, MA plot for RNA-Seq. Total RNA was extracted from purified peritoneal macrophages of WT and Tg-ACE mice, and next generation sequencing was performed to measure gene expression (n = 4/group). Shown is an MA plot comparing Tg-ACE macrophages to WT macrophages. Values on the x axis are the log 2 mean expression values of a gene, whereas the y axis shows the log 2 of the fold change in expression values where increased expression in Tg-ACE is indicated by a positive number. Tg-ACE macrophages showed down-regulation of the M2 macrophage genes IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, Ccl5, Ccl12, Ccl17, Ccl20, Ccl24, IL-5ra IL-9r, and Retnla. B, confirmation of basal M2 gene expression. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO mice, and cultured as described under “Experimental procedures.” Panel i, the production of cytokines was determined in the macrophage supernatant by ELISA (n = 4/group). Panel ii, measurement of gene expression by real-time qRT-PCR (n = 4/group).

To examine domain-specific down-regulation of these M2 genes at basal level, we compared protein expression of these proteins in Tg-NKO versus Tg-CKO macrophages. Consistent with the RNA-Seq data, we found strong inhibition of M2 gene expression (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, CCL5, CCL12, CCL17, CCL20, CCL24, Il9r, Il5ra, and Retnla) in Tg-ACE macrophages. Again, Tg-NKO macrophages resembled Tg-ACE cells, whereas Tg-CKO cells showed an expression pattern closer to that of WT cells (Fig. 7B).

Thus, our data suggest that overexpression of the ACE C-domain coupled with both increased M1 and decreased M2 gene expression. This may underpin the increased tumor resistance observed in Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice.

Discussion

The importance of ACE, angiotensin II, and the renin-angiotensin system in hypertension, heart failure, and renal disease often obscures the fact that ACE is a relatively nonspecific enzyme with many substrates in addition to angiotensin I (1, 2, 19, 20). Although never as prominent as the role of ACE in cardiovascular disease, evidence for involvement of ACE in inflammation goes back to the 1975 report that patients with active sarcoidosis have elevated serum ACE levels and that resolution of sarcoidosis restored serum ACE to normal (21). Further study indicated that macrophages and giant cells comprising sarcoid granuloma and many other granulomatous diseases make ACE, presumably as part of the activation of these cells (22, 23). Other publications also showed that activated macrophages produce ACE (24). For example, analysis of human atherosclerotic lesions by Diet et al. (25) and Ohishi et al. (26) established that in all stages of atherosclerosis, the macrophages within the lesions produce large amounts of ACE. Further, when the human monocytoid cell line THP-1 was differentiated to macrophages with PMA, the expression of ACE by macrophages increased ∼3-fold. When the cells were differentiated with PMA plus acetylated low-density lipoprotein, ACE expression increased ∼6-fold (25). These and other findings establish the association of macrophage activation with ACE expression. However, it was not until recently that experiments in mice showed that ACE is not only associated with macrophage activation but is an active participant contributing to an increase in the immune response. This was best observed in two mouse lines in which genetic manipulation was used to force increased myeloid ACE expression. Specifically, animals called ACE 10/10 overexpress ACE in monocytes and macrophages, whereas NeuACE mice overexpress ACE only in neutrophils (4, 5). In both mouse lines, overexpression of ACE is associated with an increased immune response. For example, in ACE 10/10 mice, there is increased resistance to tumors, infection, and a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (4, 6, 27, 28). When ACE 10/10 mice are immunized with ovalbumin, they produce higher levels of antibody than equivalently treated WT mice (3, 29). The resistance of NeuACE mice to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is much better than mice with WT neutrophil levels of ACE expression, which in turn is much better than mice lacking ACE in neutrophils (5). In NeuACE mice, treatment with an ACE inhibitor reverts MRSA resistance to that of similarly treated WT animals (5). In fact, treatment with the ACE inhibitor ramipril decreased bacterial clearance in all animals, even in WT mice. Thus, there are now substantial data indicating that ACE activity is not only associated with myeloid cell activation but participates in increasing the immune response.

What remains unknown is the mechanism of how ACE overexpression changes myeloid cell function. The ACE protein contains two distinct catalytic sites. Although the substrate specificities of the two domains are overlapping, they are not identical (1, 3). Further, ACE 10/10 mice overexpress ACE in monocytes and macrophages, but the genetic change creating these mice also eliminated ACE expression by vascular endothelium (4). The transgenic lines Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, and Tg-CKO have the advantage of permitting study of the two ACE domains in mice that maintain normal expression of ACE by endothelium and other nonmyeloid tissues. This showed that Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice strongly resist melanoma growth as compared with Tg-CKO mice and mice with WT levels of ACE expression. Thus, a catalytically active ACE C-domain is critical in the ability of ACE to induce increased myeloid cell resistance to tumor. Because neutrophil deletion has no effect on tumor growth, we believe that it is ACE activity by monocytes and macrophages that is critical for tumor resistance.

Macrophages readily adopt different phenotypes depending on the tissue environment. The functional heterogeneity of macrophages has been broadly classified into two types: “classically” activated (M1) or “alternatively” activated (M2). M1 macrophages typically produce pro-inflammatory molecules such as TNFα, IL-12, inducible nitric-oxide synthase, and increased major histocompatibility complex class 2 expression (12, 30). In contrast, M2 macrophages are generally considered anti-inflammatory with decreased expression of the M1 markers (12, 30, 31). They express other signature molecules, including elevated IL-10, arginase, and scavenger receptors (12, 30). Closely related to M2 macrophages are tumor-associated macrophages, which are often found within tumors and are thought to support tumor growth and limit the anti-cancer inflammatory response (12, 31). Given the strong anti-tumor phenotype of macrophages from Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO mice, it is not surprising that such macrophages produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-6, IL-12, and nitric oxide as compared with macrophages from Tg-CKO mice or WT mice. In contrast, Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO macrophages produced less of several anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, than Tg-CKO and WT macrophages. Thus, these findings indicate that it is increased activity of the ACE C-domain that induces the biochemical pattern of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages.

The concept that overexpression of the C-domain of ACE drives cells toward a more pro-inflammatory state is consistent with a previous study from our group in which we investigated the effect of ACE on the formation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (32). This heterogenous population of relatively immature myeloid cells is immunosuppressive. We found that ACE levels were inversely correlated with the number of MDSCs. In a model of chronic inflammation induced by injection of complete Freund's adjuvant, ACE 10/10 mice produced less MDSCs than WT mice, whereas animals null for ACE expression produced abundantly more MDSCs than WT (32, 33). In fact, mice lacking ACE have a bone marrow shift toward increased numbers of immature myeloid precursors (19). In the context of the present study, these findings indicate an important role for ACE in myeloid cell differentiation toward pro-inflammatory cells.

One of the major signals for M1 polarization is TNFα (13, 14). To study whether TNFα signaling pathways play a role in ACE-mediated tumor resistance, Tg-NKO macrophages were stimulated with melanoma-conditioned medium in the presence of anti-TNFα antibody. This suppressed M1 activation of Tg-NKO macrophages and increased M2 marker expression. TNFα blockade eliminated the increased NF-κB activation normally present in Tg-NKO versus WT macrophages following tumor challenge. In vivo, TNFα blockade decreased the anti-tumor effectiveness of Tg-NKO macrophages when these cells were injected into tumors.

Although TNFα is affected by several cellular signals, we showed that ROS play an important role in the production of this cytokine by Tg-ACE and Tg-NKO cells. Specifically, the increased production of TNFα in these cells is blocked by treatment of cells with the ROS inhibitor DPI.

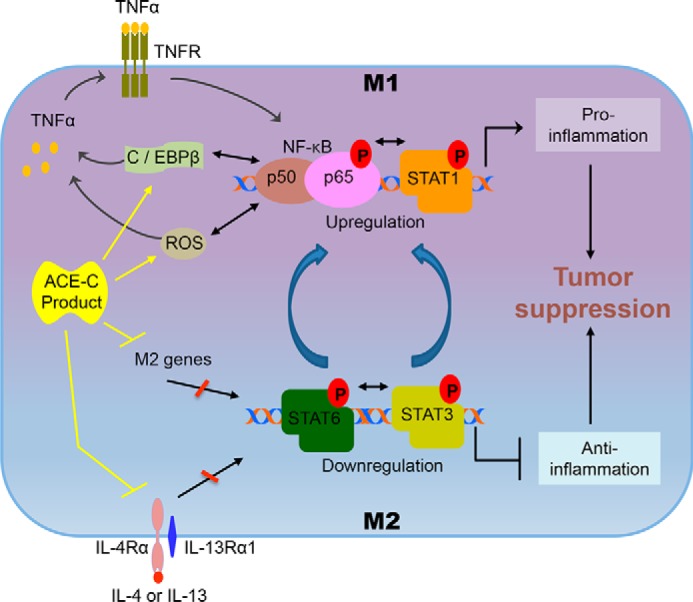

Tg-NKO macrophages make increased levels of C/EBPβ protein an important transcriptional factor for TNFα production (15, 16). Also, Tg-NKO macrophages express less IL-4Rα and other M2 markers, which probably augments the M1 stimulus of TNFα. The M1 and M2 pathways are dynamic and counteract each other at several levels (12, 34). As indicated in Fig. 8, ACE overexpression in macrophages changes a constellation of biochemical signals—C/EBPβ, IL-4Rα, ROS, NF-κB, STAT1, and others—that collectively enhance M1-like activation of macrophages. The net effect is an increase of the immune response substantially beyond that of WT mice. In mice, the ACE C-domain is the predominant domain converting angiotensin I to angiotensin II (7). However, the data presented here, as well as in previous publications, show that neither angiotensin II nor any angiotensin peptide is responsible for ACE-mediated enhancement of myeloid function (2). Also, neither bradykinin/B2R nor substance P/NK1R appear to play a role. Although artificial ACE C-domain substrates have been described, we know of no known natural ACE substrates that are thought to be C-domain–specific (1). Nonetheless, whatever the unknown peptides responsible for the immune effect, we believe they are substrates and products of only the ACE C-domain.

Figure 8.

Effect of ACE C-domain up-regulation on macrophage polarization. The interaction of pathways for M1 and M2 macrophage polarization is outlined. By inducing anti-inflammatory signals, the M2 pathway is associated with tumor progression. This pathway is regulated by the activation of STAT3 and STAT6. In contrast, the M1 macrophage pathway suppresses tumor growth by inducing pro-inflammatory signals. The M1 pathway is mainly controlled by the activation of TNFα, NF-κB, and STAT1. The M1 and M2 pathways cross-talk with each other, which results in reciprocal modulation. NF-κB and STAT1 activation reduces STAT3 and STAT6 activation, or vice versa. As discussed in the text, TNFα plays a critical role in ACE C-domain–mediated M1 activation of macrophages and tumor resistance. Mechanistically, we found up-regulation of ROS and C/EBPβ in ACE C-domain overexpressing macrophages, which is known to enhance TNFα production. The enhanced level of TNFα can induce activation of NF-κB in a positive feedback loop leading to increased M1 signals and reduced M2 signals. ACE C-domain up-regulation also reduced expression of several key M2 markers including IL-4Rα, IL-4, IL-13, CCL17, CCL20, CCL24, and Retnla, which typically induce M2 macrophage signals and inhibit M1 macrophage activation, including up-regulation of TNFα expression. These data suggest that increased activation of TNFα, NF-κB, and STAT1, as well as decreased activation of STAT3 and STAT6, underpin the increased inflammatory phenotype induced by ACE C-domain up-regulation.

Experimental procedures

Mice

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee. To generate Tg-ACE transgenic mice, mouse ACE cDNA was modified to contain the mouse c-fms promoter before the transcription start site (Fig. 1A) (4, 35). C57BL/6 mice were then made transgenic for this construct using standard approaches. For generating Tg-NKO and Tg-CKO transgenic mice, we used ACE cDNA constructs with point mutations to inactivate either the N- or the C-domain of ACE (Fig. 1A). Founder lines were identified with ACE overexpression in macrophages. The transgenic families were then bred to homozygosity for the transgenic construct. All mice were 8–12 weeks old. Both male and female mice were studied, and no phenotypic differences were noted. WT mice (C57BL/6) were used as a control group.

Cells and tumor model

The B16-F10 melanoma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Before use, melanoma cells were detached using 0.025% trypsin for 5 min, washed, and counted. The cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 107 cells/ml with PBS. A single tumor per animal was created by intradermal injection of B16-F10 melanoma cells (106 cells in 100 μl) into the flank. The growth of the tumor was monitored using calipers until 2 weeks. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula V = [L × W2] × 0.52, where V is volume, L is length, and W is width (length is greater than width) (36).

To investigate the role ACE and the angiotensin (Ang) II AT1 receptor on tumor resistance, we performed tumor growth experiments in mice pretreated for 7 days with either the ACE inhibitor ramipril (40 mg/liter in drinking water) or the AT1 receptor blocker losartan (600 mg/liter in drinking water) (5). The drug treatments were continued throughout the study.

To study the role of neutrophils in tumor resistance, we measured tumor growth in neutrophil-depleted mice. Before tumor implantation, the mice were made neutropenic as described previously (5, 37). In brief, neutrophils were depleted by i.p. injection of 100 μl of rabbit anti-mouse PMN antibody (Cedarlane Labs, 2.5 mg/ml) 2 days prior to tumor implantation. One injection every 24 h was continued until the end of experiment. Tumor size was measured at day 14.

To directly access whether ACE overexpressing macrophages suppress tumor growth, we adoptively transferred macrophages into tumor-bearing WT mice. At 7 days after melanoma implantation in WT mice, the tumor was visualized in all mice (∼50 mm3) and was injected with 3 × 106 macrophages derived from either WT, Tg-ACE, Tg-NKO, or Tg-CKO mice. Final tumor volume was determined at day 14. To investigate the role of TNFα, this experiment also done with TNFα inhibition. We treated macrophages with anti-TNFα antibody overnight to block TNFα before injecting into tumors. In addition, tumor-bearing mice were injected i.p. with C87 (12.5 mg/kg), a chemical TNFα inhibitor (Tocris, catalog no. 5484), as previously used (18). In toto, two doses were given to mice: one on the day of intratumor macrophage injection and a second dose 3 days later.

Other methods

All other methods, such as macrophages isolation, flow cytometry analysis, Western blotting, real-time quantitative PCR, ELISA, ACE activity assay, and RNA-Seq are described in detail in the supporting text.

Author contributions

Z. K. and K. E. B. conceptualization; Z. K., D.-Y. C., and J. F. G. data curation; Z. K. and G. Y. L. formal analysis; Z. K. investigation; Z. K., D.-Y. C., J. F. G., E. A. B., L. C. V., S. F., and Z. P. methodology; Z. K. and K. E. B. writing-original draft; Z. K. and K. E. B. writing-review and editing; Y.W. and M.K. software; K. E. B. resources; K. E. B. supervision; K. E. B. funding acquisition; K. E. B. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Makoto Katsumata (Mouse Genetics Core, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA) for help in generating the transgenic mice.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01HL129941 (to K. E. B.), AI143599 (to K. E. B.), R21AI114965 (to K. E. B.), R01HL142672 (to J. F. G.), and P30DK063491 (to J.F.G.) and American Heart Association Grants 17GRNT33661206 (to K. E. B.) and 16SDG30130015 (to J. F. G.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supporting text, references, and Figs. S1–S6.

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE123952.

- ACE

- angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AT1

- angiotensin II type 1

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- FCM

- flow cytometry

- IL

- interleukin

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- DPI

- diphenyleneiodonium

- IL-4Rα

- IL-4 receptor α

- MRSA

- methicillin-resistant S. aureus

- MDSC

- myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- Ang

- angiotensin

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR.

References

- 1. Bernstein K. E., Ong F. S., Blackwell W. L., Shah K. H., Giani J. F., Gonzalez-Villalobos R. A., Shen X. Z., Fuchs S., and Touyz R. M. (2013) A modern understanding of the traditional and nontraditional biological functions of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Pharmacol. Rev. 65, 1–46 10.1124/pr.112.006809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernstein K. E., Khan Z., Giani J. F., Cao D. Y., Bernstein E. A., and Shen X. Z. (2018) Angiotensin-converting enzyme in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 14, 325–336 10.1038/nrneph.2018.15,10.1038/s41582-018-0002-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shen X. Z., Billet S., Lin C., Okwan-Duodu D., Chen X., Lukacher A. E., and Bernstein K. E. (2011) The carboxypeptidase ACE shapes the MHC class I peptide repertoire. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1078–1085 10.1038/ni.2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen X. Z., Li P., Weiss D., Fuchs S., Xiao H. D., Adams J. A., Williams I. R., Capecchi M. R., Taylor W. R., and Bernstein K. E. (2007) Mice with enhanced macrophage angiotensin-converting enzyme are resistant to melanoma. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 2122–2134 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan Z., Shen X. Z., Bernstein E. A., Giani J. F., Eriguchi M., Zhao T. V., Gonzalez-Villalobos R. A., Fuchs S., Liu G. Y., and Bernstein K. E. (2017) Angiotensin-converting enzyme enhances the oxidative response and bactericidal activity of neutrophils. Blood 130, 328–339 10.1182/blood-2016-11-752006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernstein K. E., Koronyo Y., Salumbides B. C., Sheyn J., Pelissier L., Lopes D. H., Shah K. H., Bernstein E. A., Fuchs D. T., Yu J. J., Pham M., Black K. L., Shen X. Z., Fuchs S., and Koronyo-Hamaoui M. (2014) Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in myelomonocytes prevents Alzheimer's-like cognitive decline. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1000–1012 10.1172/JCI66541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuchs S., Xiao H. D., Hubert C., Michaud A., Campbell D. J., Adams J. W., Capecchi M. R., Corvol P., and Bernstein K. E. (2008) Angiotensin-converting enzyme C-terminal catalytic domain is the main site of angiotensin I cleavage in vivo. Hypertension 51, 267–274 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fuchs S., Xiao H. D., Cole J. M., Adams J. W., Frenzel K., Michaud A., Zhao H., Keshelava G., Capecchi M. R., Corvol P., and Bernstein K. E. (2004) Role of the N-terminal catalytic domain of angiotensin-converting enzyme investigated by targeted inactivation in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15946–15953 10.1074/jbc.M400149200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fidler I. J., and Nicolson G. L. (1976) Organ selectivity for implantation survival and growth of B16 melanoma variant tumor lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 57, 1199–1202 10.1093/jnci/57.5.1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim S., and Iwao H. (2000) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 11–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benigni A., Cassis P., and Remuzzi G. (2010) Angiotensin II revisited: new roles in inflammation, immunology and aging. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 247–257 10.1002/emmm.201000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sica A., and Bronte V. (2007) Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1155–1166 10.1172/JCI31422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schleicher U., Paduch K., Debus A., Obermeyer S., König T., Kling J. C., Ribechini E., Dudziak D., Mougiakakos D., Murray P. J., Ostuni R., Körner H., and Bogdan C. (2016) TNF-mediated restriction of arginase 1 expression in myeloid cells triggers type 2 NO synthase activity at the site of infection. Cell Reports 15, 1062–1075 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kratochvill F., Neale G., Haverkamp J. M., Van de Velde L. A., Smith A. M., Kawauchi D., McEvoy J., Roussel M. F., Dyer M. A., Qualls J. E., and Murray P. J. (2015) TNF counterbalances the emergence of M2 tumor macrophages. Cell Reports 12, 1902–1914 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pope R. M., Leutz A., and Ness S. A. (1994) C/EBPβ regulation of the tumor necrosis factor α gene. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 1449–1455 10.1172/JCI117482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiyama A., Hiraishi S., Sakai D., and Mochida J. (2016) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β regulates the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α in the nucleus pulposus cells. J. Orthop. Res. 34, 865–875 10.1002/jor.23085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Dyken S. J., and Locksley R. M. (2013) Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 317–343 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma L., Gong H., Zhu H., Ji Q., Su P., Liu P., Cao S., Yao J., Jiang L., Han M., Ma X., Xiong D., Luo H. R., Wang F., Zhou J., and Xu Y. (2014) A novel small-molecule tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor attenuates inflammation in a hepatitis mouse model. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 12457–12466 10.1074/jbc.M113.521708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin C., Datta V., Okwan-Duodu D., Chen X., Fuchs S., Alsabeh R., Billet S., Bernstein K. E., and Shen X. Z. (2011) Angiotensin-converting enzyme is required for normal myelopoiesis. FASEB J. 25, 1145–1155 10.1096/fj.10-169433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fuchs S., Frenzel K., Xiao H. D., Adams J. W., Zhao H., Keshelava G., Teng L., and Bernstein K. E. (2004) Newly recognized physiologic and pathophysiologic actions of the angiotensin-converting enzyme. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 6, 124–128 10.1007/s11906-004-0087-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lieberman J. (1975) Elevation of serum angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) level in sarcoidosis. Am. J. Med. 59, 365–372 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90395-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rømer F. K. (1984) Clinical and biochemical aspects of sarcoidosis. With special reference to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Acta Med. Scand. Suppl. 690, 3–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iannuzzi M. C., Rybicki B. A., and Teirstein A. S. (2007) Sarcoidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2153–2165 10.1056/NEJMra071714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okabe T., Yamagata K., Fujisawa M., Watanabe J., Takaku F., Lanzillo J. J., and Fanburg B. L. (1985) Increased angiotensin-converting enzyme in peripheral blood monocytes from patients with sarcoidosis. J. Clin. Invest. 75, 911–914 10.1172/JCI111791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diet F., Pratt R. E., Berry G. J., Momose N., Gibbons G. H., and Dzau V. J. (1996) Increased accumulation of tissue ACE in human atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Circulation 94, 2756–2767 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohishi M., Ueda M., Rakugi H., Naruko T., Kojima A., Okamura A., Higaki J., and Ogihara T. (1997) Enhanced expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme is associated with progression of coronary atherosclerosis in humans. J. Hypertens. 15, 1295–1302 10.1097/00004872-199715110-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okwan-Duodu D., Datta V., Shen X. Z., Goodridge H. S., Bernstein E. A., Fuchs S., Liu G. Y., and Bernstein K. E. (2010) Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in mouse myelomonocytic cells augments resistance to Listeria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39051–39060 10.1074/jbc.M110.163782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernstein K. E., Gonzalez-Villalobos R. A., Giani J. F., Shah K., Bernstein E., Janjulia T., Koronyo Y., Shi P. D., Koronyo-Hamaoui M., Fuchs S., and Shen X. Z. (2014) Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in myelocytes enhances the immune response. Biol. Chem. 395, 1173–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhao T., Bernstein K. E., Fang J., and Shen X. Z. (2017) Angiotensin-converting enzyme affects the presentation of MHC class II antigens. Lab. Invest. 97, 764–771 10.1038/labinvest.2017.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Biswas S. K., and Mantovani A. (2010) Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 11, 889–896 10.1038/ni.1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qian B. Z., and Pollard J. W. (2010) Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 141, 39–51 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen X. Z., Okwan-Duodu D., Blackwell W. L., Ong F. S., Janjulia T., Bernstein E. A., Fuchs S., Alkan S., and Bernstein K. E. (2014) Myeloid expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme facilitates myeloid maturation and inhibits the development of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Lab. Invest. 94, 536–544 10.1038/labinvest.2014.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shah K. H., Shi P., Giani J. F., Janjulia T., Bernstein E. A., Li Y., Zhao T., Harrison D. G., Bernstein K. E., and Shen X. Z. (2015) Myeloid suppressor cells accumulate and regulate blood pressure in hypertension. Circ. Res. 117, 858–869 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang N., Liang H., and Zen K. (2014) Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1-m2 polarization balance. Front. Immunol. 5, 614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sasmono R. T., Ehrnsperger A., Cronau S. L., Ravasi T., Kandane R., Hickey M. J., Cook A. D., Himes S. R., Hamilton J. A., and Hume D. A. (2007) Mouse neutrophilic granulocytes express mRNA encoding the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (CSF-1R) as well as many other macrophage-specific transcripts and can transdifferentiate into macrophages in vitro in response to CSF-1. J. Leukocyte Biol. 82, 111–123 10.1189/jlb.1206713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang J., Sun L., Myeroff L., Wang X., Gentry L. E., Yang J., Liang J., Zborowska E., Markowitz S., and Willson J. K. (1995) Demonstration that mutation of the type II transforming growth factor β receptor inactivates its tumor suppressor activity in replication error-positive colon carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22044–22049 10.1074/jbc.270.37.22044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Savov J. D., Gavett S. H., Brass D. M., Costa D. L., and Schwartz D. A. (2002) Neutrophils play a critical role in development of LPS-induced airway disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 283, L952–L962 10.1152/ajplung.00420.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.