Abstract

Transmembrane protein 16 (TMEM16) family members play numerous important physiological roles, ranging from controlling membrane excitability and secretion to mediating blood coagulation and viral infection. These diverse functions are largely due to their distinct biophysical properties. Mammalian TMEM16A and TMEM16B are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs), whereas mammalian TMEM16F, fungal afTMEM16, and nhTMEM16 are moonlighting (multifunctional) proteins with both Ca2+-activated phospholipid scramblase (CaPLSase) and Ca2+-activated, nonselective ion channel (CAN) activities. To further understand the biological functions of the enigmatic TMEM16 proteins in different organisms, here, by combining an improved annexin V-based CaPLSase-imaging assay with inside-out patch clamp technique, we thoroughly characterized Subdued, a Drosophila TMEM16 ortholog. We show that Subdued is also a moonlighting transport protein with both CAN and CaPLSase activities. Using a TMEM16F-deficient HEK293T cell line to avoid strong interference from endogenous CaPLSases, our functional characterization and mutagenesis studies revealed that Subdued is a bona fide CaPLSase. Our finding that Subdued is a moonlighting TMEM16 expands our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of TMEM16 proteins and their evolution and physiology in both Drosophila and humans.

Keywords: membrane transport, membrane biophysics, ion channel, Drosophila, calcium-binding protein, Anoctamin, CaCC, phospholipid scramblase, protein moonlighting, TMEM16

Introduction

The groundbreaking discoveries of TMEM16A3 and TMEM16B as the long-sought CaCCs (1–3) revealed a novel membrane protein superfamily that includes the TMEM16 family and its closely related OSCA, TMEM63, and TMC membrane protein families (4, 5). TMEM16 proteins have been found in fungi (6, 7), amoeboids (8), insects (9), and vertebrates (10–12). The unexpected findings of mammalian TMEM16F as a moonlighting protein (13, 14), a special type of protein that can perform two or more distinct functions without gene fusions, multiple RNA splice variants, or multiple proteolytic fragments (15–18), advanced our understanding of the enigmatic TMEM16 family (10–12, 19, 20). Serving as a bona fide CaPLSase (13) and a small-conductance CAN (SCAN) channel (14), TMEM16F has evolved the capability to passively transport phospholipids and ions, two structurally distinct classes of permeants, down their chemical gradients.

Upon Ca2+ binding, TMEM16F–CaPLSase mediates the rapid flip-flopping of phospholipids across cell membranes and thus dissipates the asymmetric distribution of membrane phospholipids (13). During platelet activation, TMEM16F–CaPLSase–induced phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization is essential for prothrombinase assembly, subsequent thrombin generation, and blood coagulation (21). Consistent with its importance in blood coagulation, both the Scott syndrome patients who carried TMEM16F loss-of-function mutations (13, 22) and TMEM16F-deficient mice (14) exhibited prolonged-bleeding phenotype. Despite the known physiological function of TMEM16F–CaPLSase in blood coagulation, it is unclear whether and how TMEM16F's ion channel activity can participate in this process.

Recent structural and functional studies elegantly revealed that the fungal nhTMEM16, afTMEM16, and mammalian TMEM16E (6, 7, 12, 23–25) are also moonlighting proteins with CaPLSase and channel activities. Interestingly, the mammalian TMEM16A and TMEM16B CaCCs only displayed ion channel activities (13, 26), whereas an amoebozoa TMEM16 homolog from Dictyostelium discoideum only showed CaPLSase activity when heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells (8). To elucidate the biological functions of TMEM16 moonlighting, there is an urgent need to have an in-depth understanding of TMEM16 evolution and function in different kingdoms ranging from Protozoa and Fungi to Animalia.

TMEM16 moonlighting proteins have not been identified thus far in insects, despite a recent study that clearly demonstrated the physiological importance of CaPLSase in the degeneration of Drosophila sensory neurons (27). However, the molecular identity of the Drosophila CaPLSase responsible for the observed scramblase activities remains elusive. Among the five Drosophila TMEM16 homologs, Subdued is the only protein that has been thoroughly characterized using electrophysiological tools (9). When heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells, whole-cell patch clamp recordings suggested that Subdued was a CaCC. Interestingly, Subdued-deficient Drosophila exhibited severe defects in host defense when challenged with the pathogenic bacterium Serratia marcescens. It remains, however, unclear how Subdued CaCC function is involved in Drosophila's immunity.

Combining an improved annexin V-based CaPLSase imaging assay with inside-out patch clamping technique, we discovered that Subdued is also a moonlighting TMEM16 protein in Drosophila. Notably, we also found that Subdued harbors biophysical features that strikingly resemble those of the mammalian TMEM16F, which has been unambiguously shown to function as a CaPLSase and a CAN channel. Our results thus support the notion that TMEM16 moonlighting could be an ancient feature of TMEM16 family, which is conserved in fungi, insects, and vertebrates. We hope our findings can provide new insights into understanding the evolution of TMEM16 family, the molecular mechanisms of their ion and phospholipid permeation, and TMEM16 physiological functions in Drosophila.

Results

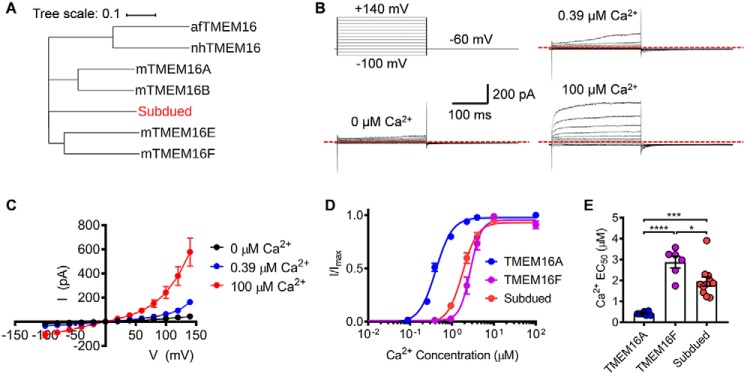

Subdued channel differs from TMEM16A–CaCC in Ca2+ and voltage dependence

Consistent with a previous report using whole-cell patch clamp recording (9), our inside-out patch clamp characterization showed that Subdued heterologously expressed in HEK293T cells also robustly elicited Ca2+- and voltage-dependent current (Fig. 1, B and C). Similar to TMEM16A–CaCC and TMEM16F–SCAN (Fig. S1), Subdued channel opening requires the synergistic action of both intracellular Ca2+ and membrane depolarization. However, one hallmark of TMEM16A–CaCC is that it adopts two distinct modes of Ca2+-dependent activation (Fig. S1, A and B). On the one hand, under submicromolar intracellular Ca2+ level (e.g. 0.39 μm), TMEM16A–CaCC is partially opened and exhibits time- and voltage-dependent activation and deactivation kinetics. On the other hand, when exposed to saturating Ca2+ level (e.g. 100 μm), TMEM16A–CaCC becomes constitutively open to give rise to a linear current-voltage (I–V) relationship (Fig. S1, A and B). However, this fingerprint feature was not observed in Subdued (Fig. 1, B and C) (9), as well as TMEM16F–SCAN (Fig. S1, C and D). Without membrane depolarization, Subdued and TMEM16F channels could barely open even in the presence of 100 μm Ca2+ (Fig. 1, B and C, and Fig. S1, C and D). In addition, both Subdued and TMEM16F channels are less sensitive to Ca2+ than TMEM16A–CaCC, as evidenced by the rightward shift of their Ca2+ dose-response curves compared with TMEM16A–CaCC (Fig. 1, D and E), in addition to minimal activation under 0.39 μm Ca2+ (Fig. 1, B and C, and Fig. S1, C and D). Therefore, Subdued's channel activation bears more similarities to TMEM16F–SCAN than to TMEM16A–CaCC.

Figure 1.

Subdued encodes a Ca2+- and voltage-activated ion channel that is different from TMEM16A–CaCC. A, phylogenic tree showing the evolutionary relationship between Subdued and other well-characterized members of TMEM16 family. Sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega, and the phylogenetic tree was plotted using iTOL-v4. B, Subdued current traces elicited by different voltages and various intracellular Ca2+ concentrations from inside-out patch recordings. Voltage protocol used is shown on the top left. C, current–voltage (I–V) relationship of Subdued current measured at 0, 0.39, and 100 μm Ca2+. D, Ca2+ dose-response curves of mTMEM1A, mTMEM16F, and Subdued. E, half-maximal activation concentrations of Ca2+ (EC50) of mTMEM16A, mTMEM16F, and Subdued channels. With one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, in E, p values are <0.0001 (TMEM16A versus TMEM16F), 0.0001 (TMEM16A versus subdued), and 0.0181 (TMEM16F versus Subdued). Error bars indicate S.E.

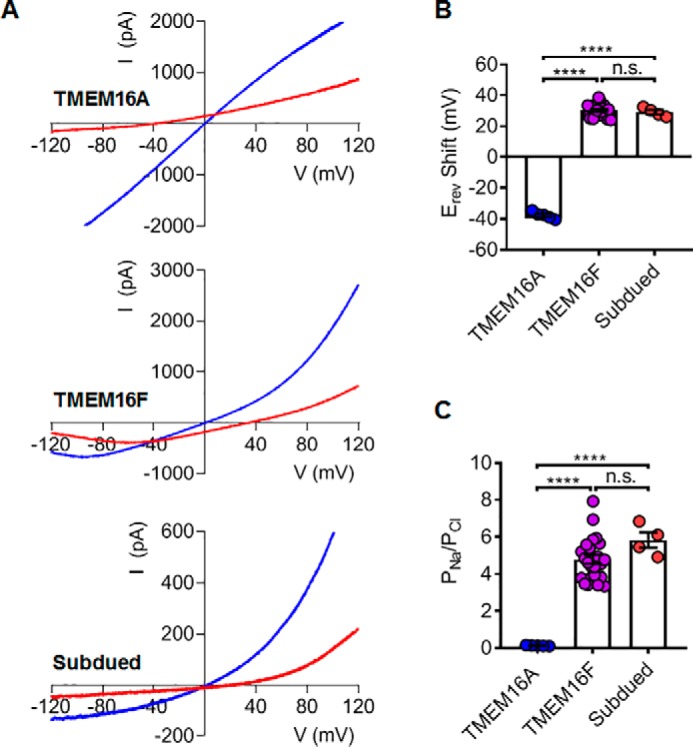

Similar to TMEM16F, Subdued is a nonselective channel with higher cation permeability

To further characterize the Subdued channel, we measured its ion selectivity using inside-out patches by switching intracellular NaCl concentration from symmetric 140 mm to asymmetric 14 mm. The 10-fold change of ion gradients would result in a large shift of the reversible potentials. For TMEM16A–CaCC, we observed a −37.6 ± 1.0 mV leftward shift of reversible potential, which was close to the predicted −58 mV shift for a strict Cl− permeable channel (Fig. 2, A and B). The small Na+ permeability (Na+/Cl− permeability ratio PNa/PCl of 0.14 ± 0.05) of TMEM16A–CaCC (Fig. 2C) is consistent with previous reports (1–3, 14, 26). On the contrary, we observed a +29.1 ± 5.8 mV rightward shift for Subdued when switching intracellular NaCl from 140 to 14 mm in the presence of 100 μm intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2, A and B). The shift is strikingly similar to the reversible potential change for TMEM16F–SCAN (+30.2 ± 0.84 mV) (14). The PNa/PCl ratios of Subdued and TMEM16F are 5.83 ± 0.42 and 4.79 ± 0.24, respectively (Fig. 2C). Our inside-out patch clamp recordings thus demonstrate that Subdued is not a CaCC. Instead, similar to TMEM16F–SCAN, it has higher permeability toward cations than anions in 100 μm intracellular Ca2+.

Figure 2.

Subdued is a nonselective ion channel with higher cation permeability. A, measurements of the reversal potentials (Erev) for mTMEM16A, mTMEM16F, and Subdued. Blue traces denote currents at symmetric 140 mm NaCl. Red traces denote currents upon switching to an intracellular solution with low 14 mm NaCl. A voltage ramp ranging from −120 to +120 mV was used to elicit channel activation and followed by a reserved +120 to −120 mV ramp, which was used to measure reversal potentials. Currents were recorded under 100 μm intracellular Ca2+. B, changes in the reversal potential (ΔErev) of mTMEM16A, mTMEM16F, and Subdued. C, permeability ratio PNa/PCl mTMEM16A, mTMEM16F, and Subdued calculated based on ΔErev in B using the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz equation (see “Experimental procedures”). With one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons tests, in B, p values are <0.0001 (TMEM16A versus TMEM16F), <0.0001 (TMEM16A versus subdued), and 0.8393 (TMEM16F versus subdued); and in C, p values are <0.0001 (TMEM16A versus TMEM16F), <0.0001 (TMEM16A versus subdued), and 0.1792 (TMEM16F versus subdued). Error bars indicate S.E. n.s. denotes nonsignificant.

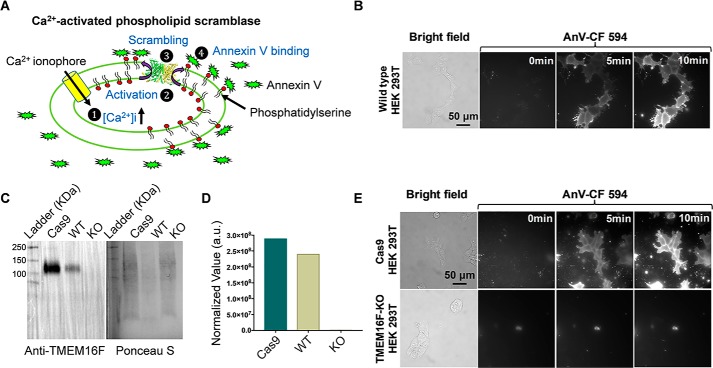

Endogenous TMEM16F in HEK293T cells strongly interferes the measurement of phospholipid scrambling

Our electrophysiological characterizations of Subdued demonstrate its resemblance to TMEM16F channel. Because TMEM16F is a moonlighting protein, we next tested whether the Subdued channel could also function as a moonlighting protein with CaPLSase activity. Nevertheless, our microscopy-based imaging assay (Fig. 3A; see “Experimental procedures” for details) revealed that the commonly used HEK293T cell line exhibited strong endogenous CaPLSase activity following addition of 5 μm Ca2+ ionophore (ionomycin) (Fig. 3B), as monitored by the time-dependent accumulation of fluorescently conjugated annexin V (AnV), a PS-specific probe, on the cell surface. This strong endogenous CaPLSase activity in HEK293T cells could severely confound the interpretation of heterologously expressed TMEM16 CaPLSases. To explicitly measure CaPLSase activity, it is therefore necessary to eliminate the contaminating endogenous CaPLSases from HEK293T cells.

Figure 3.

Generation of a TMEM16F deficient HEK293T cell line to eliminate endogenous CaPLSase interference. A, schematic demonstration of the microscopy-based, live-cell scrambling assay. In this assay, TMEM16 CaPLSases are activated by ionomycin-induced intracellular Ca2+ elevation (step 1), which subsequently mediates PS externalization (steps 2 and 3) and quickly attracts freely floating fluorescently tagged AnV (step 4). Increase in PS externalization will lead to the accumulation of AnV signal at the cell surface over time. B, WT HEK293T cells exhibited strong endogenous CaPLSase activity as examined using the assay shown in A. The CF 594–tagged AnV signal representing scrambling activity was recorded by time-lapse imaging for 10 min following application of 5 μm ionomycin (0 min) at a 5-s acquisition interval. C, Western blots showing endogenous TMEM16F expression in WT, Cas9 control (Cas9), and TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells. Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TMEM16F antibody (left panel). Total protein loading was visualized via Ponceau S staining (right panel). D, the amount of TMEM16F expression from the Western blotting was normalized to the total protein loading from Ponceau S staining. E, endogenous CaPLSase activity in HEK293T cells was eliminated from the TMEM16F–KO cell line, whereas the Cas9-HEK293T cell line retained robust endogenous CaPLSase activity.

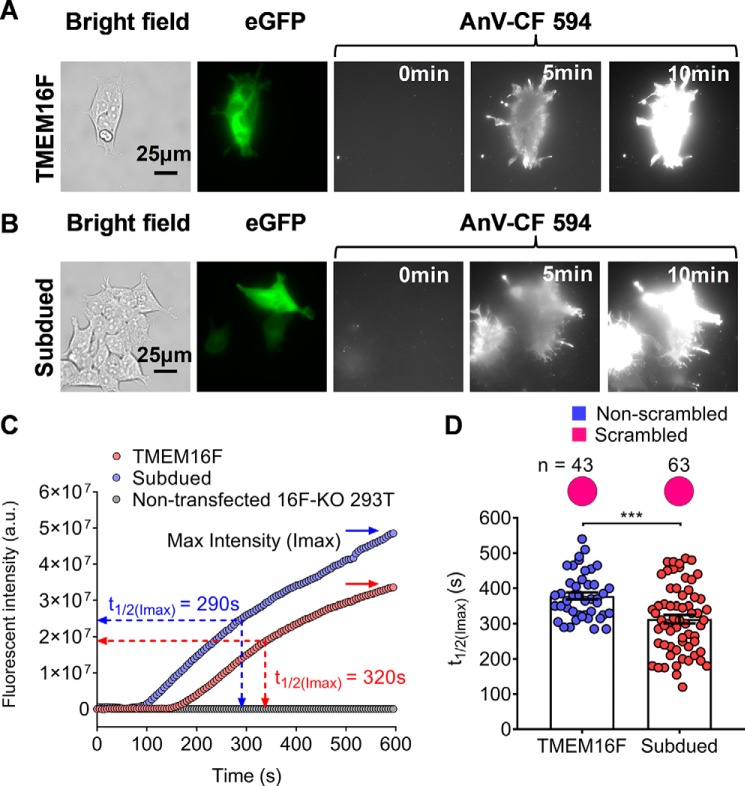

Consistent with the previous RT-PCR finding (28), we found that endogenous TMEM16F protein was indeed expressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3C). Hence, we applied the CRISPR–Cas9 method to generate a TMEM16F-deficient (TMEM16F–KO) HEK293T cell line, which not only is devoid of TMEM16F protein expression (Fig. 3, C and D) but also lacks the endogenous CaPLSase activity (Fig. 3E). Reintroducing murine TMEM16F with C-terminally tagged eGFP to the TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells resulted in robust, ionomycin-induced CaPLSase activity (Fig. 4, A and C, and Video S1). Hence, all of our subsequent scrambling characterizations of Subdued were conducted in the verified TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells.

Figure 4.

Subdued expression induces CaPLSase activity. A and B, exogenous expression of murine TMEM16F (A) and Subdued (B) in TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells induced strong CaPLSase activity. The C-terminal eGFP tagged WT–TMEM16F was used to identify TMEM16F- or Subdued-expressing cells. The CF 594–tagged AnV signal representing phospholipid scrambling was recorded by time-lapsed imaging for 10 min following application of 5 μm ionomycin (0 min) at a 5-s acquisition interval (see Videos S1 and 2 for details). C, representative AnV fluorescent intensity changes over time for TMEM16F-WT and Subdued expressing cells in A and B. TMEM16F–KO HEK cells lacking CaPLSase activity were used as a negative control. t½(Imax) is defined as the time needed to reach 50% of the maximum fluorescence intensity (Imax) after ionomycin stimulation (see “Experimental procedures”). D, ionomycin-induced CaPLSase activity for WT–TMEM16F and Subdued as quantified by their t½(Imax). Each data point represents one single cell, and n denotes the total number of expressing cells analyzed. The pie charts represent the percentages of the Subdued-expressing cells that scrambled after ionomycin application. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-sided t test. *** indicates statistical significance corresponding to p value = 0.0002. Error bars indicate S.E.

Optimizing a live cell imaging assay to quantify CaPLSase activity

Using TF3-DEVD-FMK, a fluorescent caspase dye, we observed strong fluorescent signals of AnV and TF3-DEVD-FMK in both TMEM16F-positive and -negative cells at 20 and 30 min following ionomycin stimulation (Fig. S2), which is indicative of ongoing apoptotic events. By contrast, no obvious sign of apoptosis was observed in TMEM16F-overexpressed cells as evidenced by the lack of TF3-DEVD-FMK signal at 10 min after ionomycin treatment (Fig. S2). Therefore, to avoid potential complications caused by Ca2+ overload-induced apoptosis and subsequent apoptosis-activated phospholipid scrambling (29), we limit our PS scrambling analyses within a 10-min window. To quantify CaPLSase activity, we conducted single cell analysis of AnV signal increase for each TMEM16F-expressing cell using t½(Imax), the time point at which the cell reaches 50% of its maximum AnV fluorescent intensity within 10 min following ionomycin stimulation, to evaluate CaPLSase activity (Fig. 4C).

Subdued is a CaPLSase

With the optimized CaPLSase assay, we tested whether Subdued could serve as a CaPLSase. C-terminally eGFP-tagged Subdued was readily expressed in the TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells following 24 h of transfection (Fig. 4B). Treatment with 5 μm ionomycin induced rapid and time-dependent accumulation of AnV fluorescent signal on the surfaces of Subdued-expressing cells (Fig. 4, B and C, and Video S2). The t½(Imax) value of Subdued is 313 ± 12 s, which is slightly shorter than that of TMEM16F (378 ± 10 s) (Fig. 4D). Our results on the heterologous expression of Subdued in TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells thus suggest that Subdued can function as a CaPLSase.

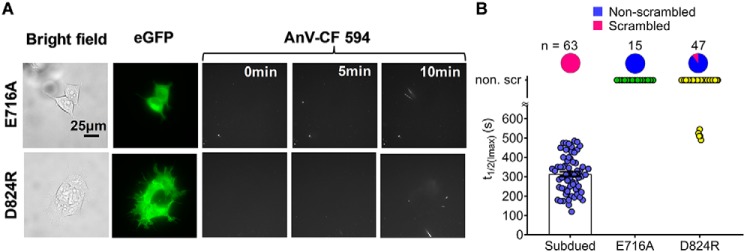

To further validate Subdued as a bona fide CaPLSase, we mutated two well-characterized and conserved residues. First, the residue corresponding to Subdued Glu-716 has been proposed to serve as an extracellular entrance controlling phospholipid permeation through nhTMEM16–CaPLSase (30). Mutating this residue in fungal nhTMEM16– and TMEM16F–CaPLSase abolished phospholipid scrambling (24, 31, 32). Consistent with the importance of this residue in controlling phospholipid permeation, Subdued E716A also abrogated ionomycin-induced phospholipid scrambling and PS externalization (Fig. 5, A and B). Second, we characterized subdued Asp-824, which is equivalent to Asp-703 in TMEM16F and Asp-734 in TMEM16A, a highly conserved Ca2+ binding aspartate. Introducing a positively charged mutation to this residue likely disrupted Ca2+ binding as evidenced by the lack of TMEM16A channel activation (33) and TMEM16F CaPLSase activity (data not shown) upon Ca2+ activation. Consistent with its importance in Ca2+ binding, a majority of the Subdued D824R–expressing cells exhibited no detectable PS externalization (Fig. 5, A and B). Only a small population (5 of 47) of Subdued D824R–expressing cells displayed weak AnV surface binding toward the end of our 10-min recording with significantly prolonged t½(Imax) values (Fig. 5B). The residual CaPLSase activity from this small percentage of cells may reflect residual activities from Subdued D824R mutant or emerging apoptosis-induced phospholipid scrambling in these cells. In summary, the mutagenesis studies using our optimized CaPLSase assay demonstrate that Subdued is a bona fide CaPLSase.

Figure 5.

Mutations of Subdued alter its CaPLSase activity. A, representative images of ionomycin-induced scrambling activity of TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells transiently transfected with plasmids encoding eGFP-tagged Subdued mutations E716A and D824R. Expression was detected by the C terminus–tagged eGFP signal. The CF 594–tagged AnV signal representing phospholipid scrambling was recorded by time-lapsed imaging for 10 min following application of 5 μm ionomycin (0 min) at a 5-s acquisition interval. B, ionomycin-induced CaPLSase activity for WT and mutant Subdued as quantified by their t½(Imax). Each data point represents one single cell, and n denotes the total number of expressing cells that were analyzed. The pie charts represent the percentages of the Subdued-expressing cells that scrambled after ionomycin application. Error bars indicate S.E. non. scr indicates nonscrambling.

Discussion

Protein moonlighting as both ion channels and phospholipid scramblases has been observed in mammal and fungal TMEM16 proteins (6, 7, 12–14, 23–25). By using patch clamp electrophysiology and an improved phospholipid scrambling assay, our studies reveal that Drosophila Subdued, an insect TMEM16, is also a moonlighting protein that can serve as both a CAN channel and a CaPLSase.

In this study, we also showed that the widely used HEK293T cell line had endogenous TMEM16F expression and strong CaPLSase activity (Fig. 3B). The endogenous CaPLSase activity can interfere with our characterization of exogenous TMEM16 CaPLSases and complicate subsequent interpretation. To circumvent this complication, we applied the CRISPR–Cas9 method to generate a TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cell line, which lacks endogenous CaPLSase activity and thereby can serve as an ideal heterologous expression system to characterize CaPLSase activities (Fig. 3E). When Subdued was heterologously expressed in this KO cell line, we observed robust Subdued-mediated CaPLSase activity (Fig. 4, B and D). Disrupting a key conserved residue at the extracellular entrance of Subdued abolished its CaPLSase activity. In addition, when one of the conserved Ca2+-binding residues was replaced with a positively charged Arg residue, the mutant Subdued failed to scramble phospholipids (Fig. 5). Collectively, our data show that Subdued is a bona fide CaPLSase.

Our inside-out excised patch clamp recordings demonstrated that Subdued is a CAN channel with higher cation permeability than chloride (PNa/PCl = 5.83) in 100 μm intracellular Ca2+. This conclusion stands in stark contrast to a previous study reporting that Subdued functioned as a CaCC (PNa/PCl = 0.16) based on whole-cell patch recordings (9). We postulate that this discrepancy might be derived from the inherent differences between the two patch clamp configurations. First, infusion of pipette solution with high micromolar Ca2+ into cytosol could disrupt intracellular environment, which might subsequently alter channel activity. In the case of Subdued, channel current run-up was observed in whole-cell recording (9). When whole-cell recording was used to measure TMEM16F current, a 5–15-min delay of channel activation has been frequently observed after membrane break-in (26). Under inside-out configuration, both Subdued (Figs. 1 and 2) and TMEM16F current (14) can be immediately recorded after membrane excision. Without the long delay to obtain stable current, the reversal potential measured using inside-out configuration may reflect the intrinsic channel selectivity. Second, whole-cell patch clamp may suffer from larger leak current during recording, especially when infusing with high micromolar Ca2+ into the cytosol. The potential leak current could confound the reversible potential measurement. Third, measuring the reversal potential requires exchanging solutions with drastically different ionic concentrations. Whole-cell recording usually requires whole-chamber solution exchange, which can induce large liquid junction potential to complicate reversal potential measurement. In our inside-out patch clamp experiments, we used a pressurized focal perfusion system to achieve rapid solution exchange directly to the excised patch membrane. Because this process is fast and only requires a small volume of solution, the impact of liquid junction potential is negligible.

We also found that Subdued ion permeability resembles that of the mammalian TMEM16F–SCAN. Similar to TMEM16F–SCAN (14), common CaCC blockers such as niflumic acid, flufenamic acid, and 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid cannot block Subdued current (9), further supporting that Subdued channel is different from TMEM16A–CaCC. Interestingly, the fungal afTMEM16 and nhTMEM16 channels also exhibit substantial cation permeability (7, 24, 25). The nonselective nature of the moonlighting TMEM16 proteins toward phospholipids and ions suggests that their ancestors may have experienced low selective pressure during evolution, so that they could mediate simultaneous permeation of different ions and phospholipids without expanding the genome size. Interestingly, TMEM16A and TMEM16B are more selective to anions and lack CaPLSase function. We hope our current findings can shine new lights on understanding TMEM16 evolution and molecular mechanisms for substrate selectivity.

Our study also provides new insights into understanding the physiological functions of TMEM16 moonlighting proteins. Previous studies have shown that Subdued knockout or knockdown Drosophila strains harbored defects in their host defense and exhibited lethality upon ingestion of the pathogenic bacteria S. marcescens (9, 34). It is thus far not clear whether Subdued's CaPLSase function and/or ion channel function play a major role in participating host defense. Interestingly, the moonlighting protein TMEM16F has also been reported to express in immune cells and play an important role in immune responses (35–37). Considering the fact that channel activation of both Subdued and TMEM16 CAN current (14) requires both high Ca2+ and membrane depolarization (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1D), both of which conditions are unlikely to be achieved under physiological conditions, it is likely that their CaPLSase functions might play the major role in immunity. A recent study suggested that PS externalization induced by overexpressing mammalian TMEM16F–CaPLSase played an important role in controlling neurite degeneration in Drosophila sensory neurons (27). Our current finding that Subdued as a bona fide CaPLSase might help identify the CaPLSase that is responsible for Drosophila neuronal degeneration.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were purchased from Duke Cell Culture Facility and authenticated by Duke University DNA Analysis Facility. HEK293T, Cas9 control HEK 293T, and TMEM16F–KO HEK 293T were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, catalog no. 11995-065) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. X-tremeGENETM 9 DNA transfection reagent (Sigma) was used to transiently transfect HEK293T cells according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Generating TMEM16F knockout cell line and cell culture

HEK 293T cells were transduced with lentiCas9-blast (Addgene catalog no. 52962) to generate stable Cas9-expressing cells. CHOPCHOP (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/index.php) (38, 39)4 was used to design sgRNA (5′-AATAGTACTCACAAACTCCG-3′), which targets exon 2 of ANO6/TMEM16F. The sequence was then cloned into lentiguide-puro (Addgene catalog no. 52962) to generate TMEM16F-knockout (TMEM16F–KO) cells. The lentivectors, psPAX2 and pMD2.g, were co-transfected into HEK 293T using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus) to prepare lentiviruses. All transductions were done at a multiplicity of infection of <1 in the presence of 4 μg/ml Polybrene. After 24 h hours of infection, 10 μg/ml blasticidin or 2 μg/ml puromycin was applied to select cells for 48–72 h. The selected cells were then expanded. One week after transduction with sgRNA, genomic DNA was harvested from cells. The presence of deletions was confirmed by PCR amplifying ANO6 exon 2 locus from genomic DNA and subsequently analysis using the Surveyor assay (Integrated DNA Technologies). The forward primer 5′-TTTTCAGTGGTAGACCTTGCCT-3′ and reversed primer 5′-AAGTTCAGCAACCTATTCCCAA-3′ were used in the PCR.

The initial TMEM16F–KO HEK 293T was serial-diluted in 96-well plates to select for single-cell colonies. After 10–14 days, the single-cell colonies were expanded and screened for the absence of TMEM16F expression and CaPLSase function using Western blots and phospholipid scrambling assay.

Microscope-based phospholipid scrambling assay

TMEM16F–KO cells were seeded on poly-l-lysine–coated (Sigma) no. 0 glass coverslips overnight (Assitent). pEGFP-N1 vector carrying coding sequences of either mouse TMEM16F (Open Biosystems cDNA catalog no. 6409332), Subdued (FlyBase identification no. FBcl0155770), or their mutations with C-terminal eGFP tag were transiently transfected to the seeded TMEM16F–KO HEK 293T cells by using X-tremeGENE9 transfection reagent (Millipore–Sigma). After 5 h of transfection, medium was changed to regular Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, catalog no. 11995-065). After 24–48 h of transfection, the cells were examined for their scrambling activity. CF-594 tagged annexin V (Biotium catalog no. 29011) with the concentration of 50 μg/ml was diluted to 1:100 ratio by using annexin V–binding solution (10 mm HEPES, 140 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4). The diluted CF 594–tagged-AnnexinV and coverslips with transfected cells were added subsequently into a homemade imaging chamber. eGFP signal from the expressing cells was used to adjust focus on the cells. An equal volume of annexin V–CF 594 with 10 μm ionomycin, which was diluted from a fresh aliquot of 5 mm ionomycin (Alomone) stock solution, was added into the chamber to reach the final concentration of 5 μm to activate phospholipid scramblase. The PS exposure of the cells was represented by the accumulation of annexin V–CF 594 on the cells membrane captured with time-lapse imaging with 5-s intervals by a Prime 95B Scientific CMOS Camera (Photometrics) connected to an Olympus IX71 inverted epifluorescent microscope (Olympus IX73) for 10 min upon ionomycin application (0 min). A 60× oil objectives with NA of 1.35 was used for imaging. Image acquisition was controlled by Metafluor software (Molecular Devices).

Live cell TF3-DEVD-FMK staining assay

Live cell Caspase 3/7 binding assay kit (AAT Bioquest, catalog no. 20101) was used to detect cleaved Caspase 3/7 level in live TMEM16F-positive and -negative cells. TMEM16F–KO 293T were seeded and transfected on poly-l-lysine–coated no. 0 coverslips. After 24 h of transfection, the cells were washed with fresh medium and then incubated with 1× TF3-DEVD-FMK (diluted in culture medium) for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The 150× stock solution of TF3-DEVD-FMK was prepared and stored as recommended by the manufacturer (AAT Bioquest). The cells were then treated with 5 μm ionomycin in the presence of 1X TF3-DEVD-FMK for 10, 20, and 30 min. After ionomycin treatment, the cells were washed twice with the kit's washing buffer and then imaged with 1:100 dilution of CF 640R-tagged AnV (Biotium catalog no. 29014). The results were collected with a 63×/1.4 NA Oil Plan-Apochromat DIC in Zeiss 780 inverted confocal microscope and analyzed with ImageJ and Zeiss.

Quantifying phospholipid scrambling activity

t½(Imax), which is the amount of time each individual cell takes to reach 50% of its maximum AnV fluorescent intensity within 10 min following ionomycin stimulation, was used to quantify TMEM16F scrambling activity. The value of t½(Imax) was extracted from the AnV fluorescent intensity change over time of each cell by using a customized MATLAB program (Mathworks). From the written MATLAB program, we define a region of interest around the scrambling cells, and the AnV fluorescent intensity was calculated using the following equation for each frame,

| (Eq. 1) |

where i equals the intensity of each pixel, and N is the number of pixels in the region of interest. The time reaching half of Imax was defined as t½(Imax). t½(Imax) values were plotted and statistically analyzed using Prism (GraphPad).

Immunoblotting

WT, Cas9 control, and TMEM16F–KO HEK293T cells, grown to 80–90% confluence in 96-mm culture disks, were trypsinized and pelleted by centrifugating at 900 -rpm at 4 °C for 5 min. After washing twice with cold PBS, cell pellets were incubated with radioimmune precipitation assay lysate buffer supplemented with 5 mm EDTA and 1× protease inhibitor mixture on ice for 30 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and supplemented with 1× Laemmli with 112 mm DTT at room temperature for 30 min. SDS-PAGE gel was then used to separate the proteins, which were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer system (Bio-Rad). Ponceau S was used to stain the blot for 15 min, followed by three washes with 5% acetic acids. The Ponceau S staining was imaged by a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with PBS supplemented with 5% nonfat milk, 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-TMEM16F antibody (Millipore–Sigma, catalog no. HPA038958) was applied and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBST (PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20) for three times, the membrane was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule)–peroxidase secondary antibody (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescence signals from protein bands were detected by the ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad), and band intensity was analyzed by the Bio-Rad Imaging software. The TMEM16F bands intensity from the chemiluminescence were normalized to the total protein loading detected by Ponceau S.

Electrophysiology

All electrophysiology recordings were done at room temperature within 24–48 h after transfection. Glass pipettes were prepared using P1000 puller (Sutter Instruments) and were fire-polished using a microforge (Narishge) and had a resistance of ∼2–3 MΩ. Following formation of gigaohm seal, membrane patches were excised from cells to form inside-out patches. The pipette solution (external) contained 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.3 (NaOH), and the bath solution (internal) contained 140 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 (NaOH). For solutions containing 100 μm Ca2+, calculated CaCl2 was directly added into the internal solution without further measurement. Solutions that contained internal free Ca2+ less than 100 μm, desired amounts of CaCl2 were added into an EGTA-buffered solution containing 140 mm NaCl and 10 mm HEPES, 5 mm EGTA, adjusted to pH 7.3 (NaOH). The amounts of CaCl2 added were calculated using WEBMAXC. Free Ca2+ concentrations of EGTA-buffered Ca2+ solutions were further verified using the ratiometric Ca2+ dye Fura-2 (ATT Bioquest) and plotted against a Ca2+ standard curve generated from a Ca2+ calibration buffer kit (Biotium).

Perfusion of intracellular solutions to the cytoplasmic side of inside-out patches was done using the ALA-VM8 pressurized perfusion apparatus (ALA Scientific Instruments). All electrophysiology data were low pass–filtered at 5 kHz (Axopatch 200B) and digitally sampled at 10 kHz (Axon Digidata 1550A) and digitized by Clampex 10 (Molecular Devices).

For current–voltage relationship (I–V) recordings, the membrane was held at −60 or −80 mV, and 250-ms-long voltage steps ranging from −100 to +140 mV with a 20-mV increment were applied. Currents were elicited by perfusion of different intracellular solutions of desired free Ca2+.

For Ca2+ concentration-dependent recordings of TMEM16A, the membrane was constantly held at +60 mV, and the dose-dependent currents were elicited by perfusion of intracellular solutions with various free Ca2+ concentrations. Quasi-steady state current amplitudes were measured for each Ca2+ puff and normalized to the peak current elicited by 100 μm Ca2+. For TMEM16F and Subdued, a repeated voltage step protocol (−80 mV and +80 mV, holding at 0 mV) was used to avoid rapid rundown of channel activity. Different Ca2+-containing solutions were perfused to obtain currents for each voltage step. Peak currents at +80 mV were used to construct the Ca2+ dose-response curves.

For reversal potential (Erev) measurements, inside-out configuration was used for rapid exchange of the intracellular solutions (bath solutions). First, the channels were activated in which the pipette solution and perfusion solution (symmetric 140 mm Cl−) both contained 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 (NaOH) and osmolarity of ∼300 (d-mannitol). For TMEM16A, inward and outward currents were elicited by a repeated ramp protocol from −120 to +120 mV. For TMEM16F and Subdued, because of the stringent requirement for depolarization during activation, an inverted V-shaped ramp protocol in which the membrane was ramped from −120 to +120 mV and back to −120 mV. The second ramp phase (+120 to −120 mV) was used to construct the I–V plots used for Erev measurements of TMEM16F and Subdued. Changes in Erev were triggered by replacing intracellular solution with a solution (low 14 mm Cl−) containing 14 mm NaCl, 5 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 (NaOH), 100 μm Ca2+ and osmolarity of ∼300 (adjusted with d-mannitol). The reversal potential was determined as the membrane potential at which the current was 0. The shift in Erev (ΔErev) was calculated as the difference between the Erev of intracellular 14 mm NaCl from the Erev measured in symmetric 140 mm NaCl.

Data analysis for electrophysiology

Offline data analysis was performed in Clampfit, Microsoft Excel, and Prism (GraphPad). For quantification of Ca2+ dose-dependent concentrations (EC50), Ca2+-induced currents were normalized to the max current elicited by 100 μm Ca2+ and fit into a nonlinear regression curve fit with the equation,

| (Eq. 2) |

where I/Imax denotes current normalized to the max current elicited by 100 μm Ca2+, [Ca2+] denotes free Ca2+ concentration, H denotes Hill coefficient, and EC50 denotes the half-maximal activation concentration of Ca2+.

The permeability ratio PCl/PNa was calculated using the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz (GHK) equation,

| (Eq. 3) |

where Vm is the measured shift in membrane potential; PNa and PCl are the relative permeability for Na+ and Cl−, respectively; [Na]o and [Na]i are external and internal Na+ concentrations, respectively; [Cl]o and [Cl]i are external and internal Cl− concentrations, respectively; F is the Faraday's constant (96485 C mol−1); R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1); and T is the absolute temperature (298.15 K at 25 °C).

Structural and sequence analysis

Sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega with default parameters (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) (40).4 The phylogenetic tree was visualized and plotted using iTOL v4 (https://itol.embl.de/) (41).4

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Prism software (GraphPad). Comparisons yielding p values <0.05 are considered to be statistically significant. Data in summary graphs are represented as means ± S.E, and each data point represents a single recording experiment. *, **, ***, and **** denote statistical significance corresponding to p values < 0.05, < 0.01, < 0.001, < 0.0001, respectively.

Author contributions

T. L. and S. C. L. formal analysis; T. L. and S. C. L. investigation; T. L., S. C. L., and H. Y. methodology; T. L., S. C. L., and H. Y. writing-original draft; H. Y. conceptualization; H. Y. resources; H. Y. supervision; H. Y. funding acquisition; H. Y. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. So Young Kim (Duke Functional Genomics Shared Resource) for assistance generating the CRISPR HEK293T TMEM16F knockout cell lines.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DP2 GM126898 (to H. Y.) and R00-NS086916 (to H. Y.) and by funds from the Whitehead Foundation (to H. Y.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1 and S2 and Videos S1 and S2.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- TMEM

- transmembrane protein

- CaPLSase

- Ca2+-activated phospholipid scramblase

- CaCC

- Ca2+-activated Cl− channels

- CAN

- Ca2+-activated, nonselective ion channel

- SCAN

- small-conductance CAN

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- AnV

- annexin V

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FMK

- fluoromethyl ketone.

References

- 1. Yang Y. D., Cho H., Koo J. Y., Tak M. H., Cho Y., Shim W. S., Park S. P., Lee J., Lee B., Kim B. M., Raouf R., Shin Y. K., and Oh U. (2008) TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455, 1210–1215 10.1038/nature07313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caputo A., Caci E., Ferrera L., Pedemonte N., Barsanti C., Sondo E., Pfeffer U., Ravazzolo R., Zegarra-Moran O., and Galietta L. J. (2008) TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322, 590–594 10.1126/science.1163518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schroeder B. C., Cheng T., Jan Y. N., and Jan L. Y. (2008) Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 134, 1019–1029 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Milenkovic V. M., Brockmann M., Stöhr H., Weber B. H., and Strauss O. (2010) Evolution and functional divergence of the anoctamin family of membrane proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 319 10.1186/1471-2148-10-319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Medrano-Soto A., Moreno-Hagelsieb G., McLaughlin D., Ye Z. S., Hendargo K. J., and Saier M. H. Jr. (2018) Bioinformatic characterization of the anoctamin superfamily of Ca2+-activated ion channels and lipid scramblases. PLoS One 13, e0192851 10.1371/journal.pone.0192851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brunner J. D., Lim N. K., Schenck S., Duerst A., and Dutzler R. (2014) X-ray structure of a calcium-activated TMEM16 lipid scramblase. Nature 516, 207–212 10.1038/nature13984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malvezzi M., Chalat M., Janjusevic R., Picollo A., Terashima H., Menon A. K., and Accardi A. (2013) Ca2+-dependent phospholipid scrambling by a reconstituted TMEM16 ion channel. Nat. Commun. 4, 2367 10.1038/ncomms3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pelz T., Drose D. R., Fleck D., Henkel B., Ackels T., Spehr M., and Neuhaus E. M. (2018) An ancestral TMEM16 homolog from Dictyostelium discoideum forms a scramblase. PLoS One 13, e0191219 10.1371/journal.pone.0191219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong X. M., Younger S., Peters C. J., Jan Y. N., and Jan L. Y. (2013) Subdued, a TMEM16 family Ca2+-activated Cl− channel in Drosophila melanogaster with an unexpected role in host defense. Elife 2, e00862 10.7554/eLife.00862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pedemonte N., and Galietta L. J. (2014) Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins). Physiol. Rev. 94, 419–459 10.1152/physrev.00039.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whitlock J. M., and Hartzell H. C. (2017) Anoctamins/TMEM16 proteins: chloride channels flirting with lipids and extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 79, 119–143 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suzuki J., Fujii T., Imao T., Ishihara K., Kuba H., and Nagata S. (2013) Calcium-dependent phospholipid scramblase activity of TMEM16 protein family members. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 13305–13316 10.1074/jbc.M113.457937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki J., Umeda M., Sims P. J., and Nagata S. (2010) Calcium-dependent phospholipid scrambling by TMEM16F. Nature 468, 834–838 10.1038/nature09583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang H., Kim A., David T., Palmer D., Jin T., Tien J., Huang F., Cheng T., Coughlin S. R., Jan Y. N., and Jan L. Y. (2012) TMEM16F forms a Ca2+-activated cation channel required for lipid scrambling in platelets during blood coagulation. Cell 151, 111–122 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jeffery C. J. (1999) Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 8–11 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01335-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huberts D. H., and van der Klei I. J. (2010) Moonlighting proteins: an intriguing mode of multitasking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 520–525 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jeffery C. J. (2016) Protein species and moonlighting proteins: very small changes in a protein's covalent structure can change its biochemical function. J. Proteomics 134, 19–24 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Copley S. D. (2014) An evolutionary perspective on protein moonlighting. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 1684–1691 10.1042/BST20140245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Falzone M. E., Malvezzi M., Lee B. C., and Accardi A. (2018) Known structures and unknown mechanisms of TMEM16 scramblases and channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 933–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang H., and Jan L. Y. (2016) TMEM16 membrane proteins in health and disease. In Ion Channels in Health and Disease (Pitt G. S., ed) pp. 165–197, Academic Press, Boston [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bevers E. M., and Williamson P. L. (2016) Getting to the outer leaflet: physiology of phosphatidylserine exposure at the plasma membrane. Physiol. Rev. 96, 605–645 10.1152/physrev.00020.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castoldi E., Collins P. W., Williamson P. L., and Bevers E. M. (2011) Compound heterozygosity for 2 novel TMEM16F mutations in a patient with Scott syndrome. Blood 117, 4399–4400 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whitlock J. M., Yu K., Cui Y. Y., and Hartzell H. C. (2018) Anoctamin 5/TMEM16E facilitates muscle precursor cell fusion. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 1498–1509 10.1085/jgp.201812097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiang T., Yu K., Hartzell H. C., and Tajkhorshid E. (2017) Lipids and ions traverse the membrane by the same physical pathway in the nhTMEM16 scramblase. Elife 6, e28671 10.7554/eLife.28671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee B. C., Menon A. K., and Accardi A. (2016) The nhTMEM16 scramblase is also a nonselective ion channel. Biophys. J. 111, 1919–1924 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu K., Whitlock J. M., Lee K., Ortlund E. A., Cui Y. Y., and Hartzell H. C. (2015) Identification of a lipid scrambling domain in ANO6/TMEM16F. Elife 4, e06901 10.7554/eLife.06901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sapar M. L., Ji H., Wang B., Poe A. R., Dubey K., Ren X., Ni J. Q., and Han C. (2018) Phosphatidylserine externalization results from and causes neurite degeneration in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 24, 2273–2286 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shimizu T., Iehara T., Sato K., Fujii T., Sakai H., and Okada Y. (2013) TMEM16F is a component of a Ca2+-activated Cl− channel but not a volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying Cl− channel. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C748–C759 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Suzuki J., Denning D. P., Imanishi E., Horvitz H. R., and Nagata S. (2013) Xk-related protein 8 and CED-8 promote phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptotic cells. Science 341, 403–406 10.1126/science.1236758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bethel N. P., and Grabe M. (2016) Atomistic insight into lipid translocation by a TMEM16 scramblase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14049–14054 10.1073/pnas.1607574113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee B. C., Khelashvili G., Falzone M., Menon A. K., Weinstein H., and Accardi A. (2018) Gating mechanism of the extracellular entry to the lipid pathway in a TMEM16 scramblase. Nat. Commun. 9, 3251 10.1038/s41467-018-05724-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gyobu S., Ishihara K., Suzuki J., Segawa K., and Nagata S. (2017) Characterization of the scrambling domain of the TMEM16 family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6274–6279 10.1073/pnas.1703391114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tien J., Peters C. J., Wong X. M., Cheng T., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y., and Yang H. (2014) A comprehensive search for calcium binding sites critical for TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel activity. Elife 3, 02772 10.7554/eLife.02772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cronin S. J., Nehme N. T., Limmer S., Liegeois S., Pospisilik J. A., Schramek D., Leibbrandt A., Simoes Rde M., Gruber S., Puc U., Ebersberger I., Zoranovic T., Neely G. G., von Haeseler A., Ferrandon D., et al. (2009) Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies genes involved in intestinal pathogenic bacterial infection. Science 325, 340–343 10.1126/science.1173164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ousingsawat J., Wanitchakool P., Kmit A., Romao A. M., Jantarajit W., Schreiber R., and Kunzelmann K. (2015) Anoctamin 6 mediates effects essential for innate immunity downstream of P2X7 receptors in macrophages. Nat. Commun. 6, 6245 10.1038/ncomms7245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kmit A., van Kruchten R., Ousingsawat J., Mattheij N. J., Senden-Gijsbers B., Heemskerk J. W., Schreiber R., Bevers E. M., and Kunzelmann K. (2013) Calcium-activated and apoptotic phospholipid scrambling induced by Ano6 can occur independently of Ano6 ion currents. Cell Death Dis. 4, e611 10.1038/cddis.2013.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu Y., Kim J. H., He K., Wan Q., Kim J., Flach M., Kirchhausen T., Vortkamp A., and Winau F. (2016) Scramblase TMEM16F terminates T cell receptor signaling to restrict T cell exhaustion. J. Exp. Med. 213, 2759–2772 10.1084/jem.20160612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Labun K., Montague T. G., Gagnon J. A., Thyme S. B., and Valen E. (2016) CHOPCHOP v2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W272–W276 10.1093/nar/gkw398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Montague T. G., Cruz J. M., Gagnon J. A., Church G. M., and Valen E. (2014) CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W401–W407 10.1093/nar/gku410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li W., Cowley A., Uludag M., Gur T., McWilliam H., Squizzato S., Park Y. M., Buso N., and Lopez R. (2015) The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W580–W584 10.1093/nar/gkv279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ciccarelli F. D., Doerks T., von Mering C., Creevey C. J., Snel B., and Bork P. (2006) Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science 311, 1283–1287 10.1126/science.1123061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.