Abstract

The channel Orai1 requires Ca2+ store depletion in the endoplasmic reticulum and an interaction with Ca2+ sensor STIM1 to mediate Ca2+ signaling. Alterations in Orai1-mediated Ca2+ influx have been linked to several pathological conditions including immunodeficiency, tubular myopathy, and cancer. In this study, we screened large-scale cancer genomics datasets for dysfunctional Orai1 mutants. Five of the identified Orai1 mutations resulted in constitutively active gating and transcriptional activation. Our analysis showed that certain Orai1 mutations were clustered in the transmembrane 2 helix surrounding the pore, which is a trigger site for Orai1 channel gating. Analysis of the constitutively-open Orai1 mutant channels revealed two fundamental gates that enabled Ca2+ influx: Arginine side-chains were displaced so they no longer blocked the pore, and a chain of water molecules formed in the hydrophobic pore region. Together, these results enabled us to identify a cluster of Orai1 mutations that trigger Ca2+ permeation associated with gene transcription and provide a gating mechanism for Orai1.

Introduction

Classical store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOC) are distributed nearly ubiquitously and mainly consist of a two-component system, STIM1 and Orai1, the latter of which is critical for physiological functions in immune cells such as T-cell activation and gene regulation (1, 2). SOC channels are activated by cell surface receptors that deplete endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores through the soluble second messenger IP3 (1,4,5 inositol triphosphate) (3). STIM1 directly senses a drop in the ER Ca2+ concentration (4, 5), and subsequently binds to the Orai1 channel at sites of close contact between the ER and the plasma membrane (6–10). The STIM1/Orai1 complex generates a highly Ca2+-selective current that triggers many Ca2+-dependent signalling events, including activation of the transcription factor NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells), (11, 12).

In humans, the heavily suppressed SOC entry displayed by non-functional or non-expressing STIM1 and Orai1 mutants causes immunodeficiency, ectodermal dysplasia and muscular hypotonia (1, 13, 14). Conversely, constitutively active STIM1 or Orai1 mutants bypass the requirement for ER-dependent store-depletion, which results in thrombocytopenia, bleeding diathesis, miosis and tubular myopathy (14). Altered STIM1 and Orai1 abundance has been correlated to different stages of cancer progression, including proliferation (15), migration and metastasis (16, 17), and tumor growth (18, 19) as well as apoptosis resistance (15). However, researchers have not yet determined whether cancer associated mutagenesis within the almost ubiquitously distributed STIM1/Orai1 channel complex can alter cellular functions and contribute to pathogenesis (20). Moreover, it is still unknown precisely how Orai1 mutations that result in disease induce channel gating.

The atomic structure of Drosophila melanogaster Orai (dOrai) depicts a closed channel conformation with a central ion pore formed by six transmembrane (TM) 1 helices and surrounded by two rings, one of TM2/TM3 and one of TM4 helices (21). Crystallographic studies and functional experiments of the pore have provided insight into its structure, revealing the presence of two major sites that control Ca2+ permeation. The first site is a hydrophobic gate that spans the gap between the pore-lining residues Phe99 to Val102 and has been reported to require a pore helix rotation for activation (22, 23). Point mutations of these residues have resulted in the formation of constitutively active but non-selective channels (22, 23), and co-expression of STIM1 restores the Ca2+ selectivity of the Orai1-V102A mutant (22). The second site, which is made up of positively charged TM1 residues including Arg91, may form an internal electrostatic gate (21, 24, 25). A hydrophobic R91W mutation that causes severe combined immune-deficiency (SCID) fully occludes the channel pore and entirely abolishes Ca2+ entry (21, 24, 25). It is not known whether both gating sites are required to open the Orai1 channel and how the gating is controlled. In this study, we characterized several Orai1 mutants derived from human tumors. These mutants had constitutive Ca2+ influx and induced transcription factor activation independently of physiological stimuli. We propose a gating mechanism for constitutively active Orai1 channels and show how the membrane connectivity controls two gates.

Results

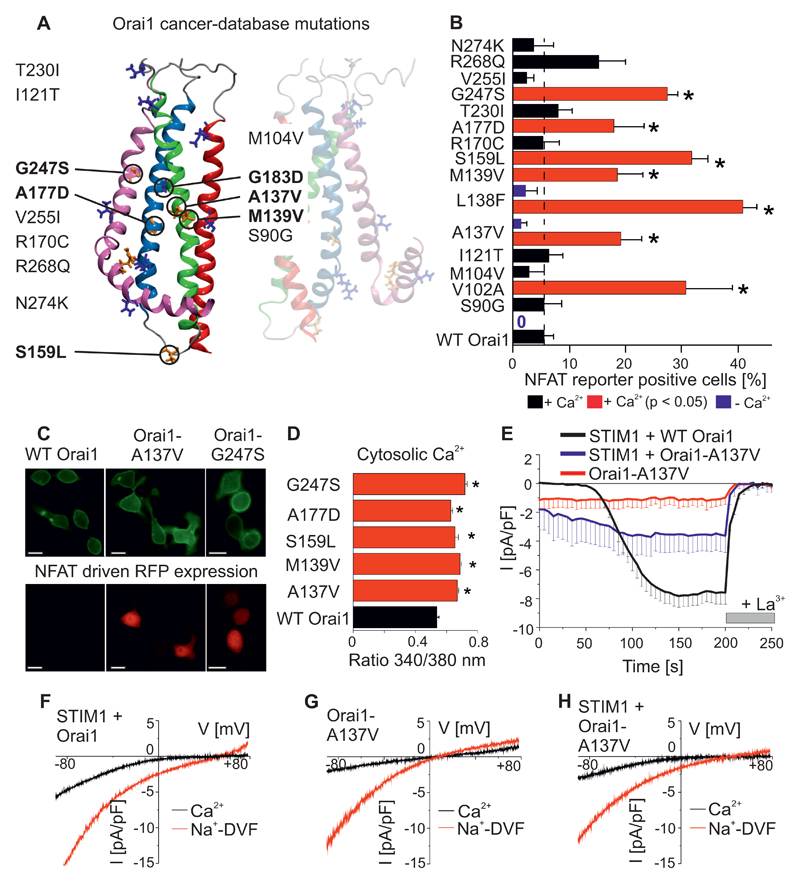

Several Orai1 mutations retrieved from cancer databases result in constitutive Ca2+ influx and NFAT-driven gene expression independently of physiological stimuli

Altered STIM1 and/or Orai channel abundance has frequently been linked to different stages of cancer progression (20, 26). The web resource cBioPortal (http://cbioportal.org) allows investigation of a large data set comprising more than 30 types of cancer from 11,000 patients analyzed using next-generation sequencing in combination with advanced bioinformatics data processing (27). By using cBioPortal, we sought to find gain-of-function Orai1 point mutations which potentially alter Ca2+ cell signaling. Cancer-derived Orai1 single point mutants affected 37 different amino-acids in different patients. These tumours contained several mutations in other proteins as well. Of the Orai1 mutations, fourteen mutants were selected because they occurred at residues that are conserved among species (Fig. 1A). Each of these Orai1 mutations occurred in a tumour of an individual patient. These Orai1 mutants were overexpressed and monitored for constitutively-active Ca2+ signals by using an approach based on fluorescence and measuring NFAT dependent gene expression (1). NFAT requires enhanced Ca2+ concentrations mediated by Orai1 or voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and calmodulin to activate the phosphatase calcineurin, which dephosphorylates NFAT, resulting in the translocation of NFAT into the nucleus to promote gene regulation (28–30). An NFAT reporter in which the expression of a red fluorescent protein (RFP) was under the control of an NFAT promotor served as a read-out for YFP-labeled Orai1 dependent NFAT signaling. The constitutively-active Orai1-L138F mutation which causes myopathy (31) and Orai1-V102A (22) served as positive controls. Heterologously-expressed Orai1-V102A and Orai1-L138F in RBL mast cells resulted in ~30 to 40% RFP positive cells in a media containing 2 mM Ca2+. Overexpression of wild-type Orai1, which served as a negative control, yielded ~ 5% RFP positive cells (Fig. 1B, C), because wild-type Orai1 requires store-depletion and STIM1 co-expression for NFAT stimulation. Of the fourteen Orai1 mutants investigated, five were identified as gain-of-function in our screen because they significantly enhanced constitutive NFAT activation. These were Orai1-A137V from a patient with colorectal adenocarcinoma (32), Orai1-M139V from a stomach carcinoma (33), Orai1-S159L from a uterine carcinoma (34), A177D from the cancer cell lines NCI-60 and G247S from a neck carcinoma (35). When heterologously expressed in HEK cells, all five of these Orai1 mutants yielded significantly-enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations at resting conditions compared to wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 1D), confirming that their constitutive Ca2+ entry drives NFAT signalling. Readdition of extracellular Ca2+ yielded robust Ca2+ entry in Orai1-A137V expressing cells but not in wild-type Orai1 expressing cells (Fig S1A). One of the Orai1 mutants studied, Orai1-G183D from a glioblastoma patient, was incorrectly integrated into the plasma membrane. Several other engineered Orai1-Gly183 mutants were also incorrectly localized, which would be expected to result in loss of function (Fig. S1D).

Figure 1. Constitutively-active Orai1 Ca2+ signals and NFAT activation induced by mutations detected through cancer database screening.

(A) Model of the human Orai1 protein structure, with Orai1 single-point mutants found in human tumors in conserved positions highlighted, as determined from large-scale cancer genomics data sets. (B) Percentage of RBL cells that express NFAT-driven RFP (average + SEM), measured 24h after co-transfection of the NFAT reporter and cancer-associated Orai1 mutants from (A), wild-type Orai1, or constitutively-active Orai1-V102A and Orai1-L138F mutants. Significantly increased number of RBL cells expressing NFAT-driven RFP (p < 0.05 by t-test) is indicated by the red bars and a star. Analogous experiments were performed in a nominally Ca2+ free bath solution for co-expression of NFAT reporter and wild-type Orai1 or Orai1-L138F, indicated by blue bars (n = 3 – 8 cell images, from at least 3 separate transfections). (C) Representative images of the co-expression of two cancer-associated Orai1 mutants (Orai1-A137V, Orai1-G247S) and wild-type Orai1 with the NFAT reporter in RBL mast cells. Scale bar, 10 µm. (D) Resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations in Fura-2-loaded HEK cells overexpressing wild-type Orai1 or cancer-associated Orai1 mutants (n = 31 – 70 cells, from 3 – 4 individual transfections). Significantly increased Ca2+ concentrations (p < 0.05 by t-test) are indicated by red bars and a star. (E) Time course of whole cell patch-clamp experiment in HEK cells co-expressing STIM1 and Orai1 (black), Orai1-A137V (blue), or Orai1-A137V alone (red) in a 10 mM extracellular Ca2+ (n = 7 – 10 cells, from at least 2 individual transfections). Store-operated currents were activated by 20 mM EGTA in patch pipette. (F-H) Representative current-voltage relationships for STIM1 and Orai1 expressing cells (F), Orai1-A137V (G), or STIM1 and Orai1-A137V (H) in a 10 mM Ca2+ (black) or Na+-based, divalent-free (Na-DVF, red) solution.

We selected an Orai1-A137V mutant that had been identified in a colorectal tumor and a Orai1-L138F myopathy mutant for further analysis in live cell experiments. As in HEK cells, Orai1-A137V yielded significantly-enhanced Ca2+ concentrations at resting conditions in colorectal carcinoma HCT-116 cells (Fig S1B,C). The store-operated activation of the Orai1-A137V mutant, which was induced by the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin, generated Ca2+ peaks that were similar to those seen in mock-transfected cells (Fig. S1B,C). In addition, we carried out patch-clamp measurements in HEK cells to examine the current activation of Orai1-A137V mutants in the presence of 10 mM Ca2+ in the cell-bath, either with or without co-expressed STIM1. Store-dependent activation was induced by buffering cytosolic Ca2+ with 20 mM EGTA. Co-expression of STIM1 and Orai1 resulted in store-operated, Ca2+-selective currents (Fig. 1E,F). Expression of Orai1-A137V alone resulted in the production of a small, constitutively-active current (Fig. 1E), and co-expression with STIM1 enhanced the activation of the store-operated currents (Fig. 1E). In addition, both the constitutive Orai1-A137V currents and the store-operated currents that were produced upon STIM1 coexpression exhibited Na+ permeation in a divalent-free bath solution (Fig. 1G,H). However, these currents were less selective than those of wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 1F, Table S1), suggesting that the mutation affected not only the activation state but also the selectivity of the channel. In analogous experiments, the Orai1-L138F myopathy mutant yielded small constitutive currents that were further enhanced by STIM1 co-expression upon store-depletion (Fig. S1E-G, Table S1). Hence, these two Orai1 mutants, which are located close together in the protein, switch the channel into an active state, which activates NFAT-dependent transcription in the absence of store-depletion.

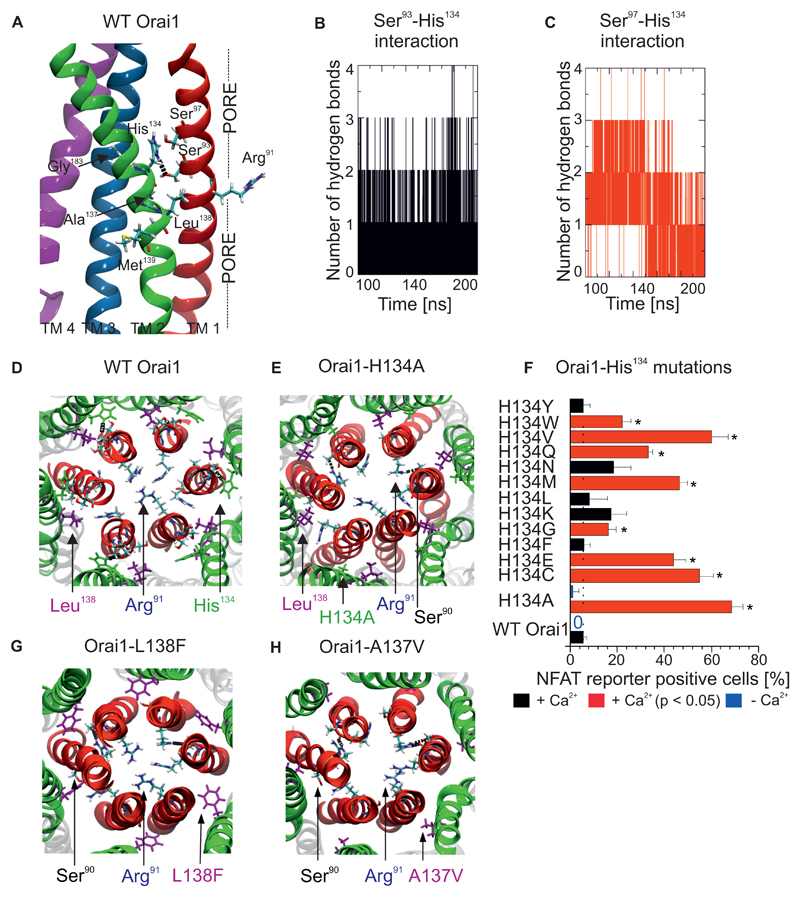

A central TM2 segment is connected to the pore helix by hydrogen bonds

Three constitutively-active Orai1 mutations (Ala137, Leu138 and Met139), two of which were obtained from the cancer database and one of which is related to myopathy, are clustered within the central TM2 segment (Fig. 2A). Because this TM2 helix segment is near the side-chains of neighbouring TM1 and TM3 helices, we examined if these three mutations could potentially interfere with side-chain interactions occurring in these TM helices. We conducted molecular dynamics simulations of the human Orai1 (12) embedded into a lipid bilayer to detect potential TM2 residue interactions with the neighbouring TM helices. Frequent electrostatic interactions were observed between His134 in TM2 and either Ser93 (Fig. 2A, B) or Ser97 (Fig. 2C, D, S2A) in the TM1 pore helix. We attempted to disrupt the hydrogen bond experimentally with an engineered Orai1-H134A mutation (Fig. 2E). Overexpression of this mutant resulted in greater NFAT-driven gene expression (Fig. 2F) compared to the other Orai1 mutants (Fig. 1B). To examine this critical His134 residue in detail, we used the NFAT reporter to analyze several Orai1-His134 point mutations. Mutations of His134 to Cys, Glu, Gly, Met, Gln, Val and Trp resulted in a significantly-increased number of RFP positive cells (Fig. 2F), indicating that substitutions of amino acids with mainly small, negatively-polarized or negatively-charged side-chains at His134 resulted in greater constitutive NFAT-driven gene expression. To determine how the connectivity between TM2 and the pore helix was altered by constitutively active mutations we used molecular dynamics simulations for the constitutively-active Orai1-H134A mutation which increased NFAT signalling (Fig. 2E), the Orai1-L138F mutation related to myopathy (Fig. 2G), and the colorectal Orai1-A137V mutation (Fig. 2H). Mutating His134 to Ala disrupted the hydrogen bond with the pore helix. The mutated, larger side-chains of Phe138 and Val137 exhibited increased numbers of hydrophobic contacts (Fig. 2G,H) with the pore helix (TM1) compared to wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 2D), but hydrogen bonds still formed between His134 and Ser93 and Ser97 in the pore (Fig. S2B, C). The results of these experiments provide evidence of the regulatory effect of TM connectivity, which is formed by specific hydrogen bonds between the pore and the surrounding TM2 helices. Disruptions of these hydrogen bonds (as in Orai1-H134A) or the induction of hydrophobic contacts (as in Orai1-A137V and Orai1-L138F) are expected to turn Orai1 into a constitutively-active channel that fully or partially stimulates NFAT signalling.

Figure 2. Interaction between a central TM2 segment and the pore helix controls Orai1 channel gating.

(A) Details of the central TM2 segment in Orai1 mutants, including pathophysiological and cancer-associated mutations (A137V, L138F, M139V), near TM1 and TM3 (Gly183). A hydrogen bond is observed between His134 and Ser93. (B,C) The number of hydrogen bonds between (B) Ser93 and His134 and (C) Ser97 and His134 in wild-type Orai1 as determined by molecular dynamics simulations. (D) Top view of a representative image of molecular dynamics simulations of the wild-type Orai1 pore, with the side-chains of Arg91, His134 and Leu138 highlighted. (E, G, H) Similar snapshots are shown of molecular dynamics simulations of Orai1-H134A (E), Orai1-L138F (G) and Orai1-A137V (H). (F) Percentage of RBL cells that express NFAT-driven RFP (average + SEM), measured 24h after co-transfection of the NFAT reporter and various Orai1 His134 mutants or wild-type Orai1. Cells were in a bath solution containing 2 mM Ca2+. Significantly increased number of cells (t-test, p < 0.05) positive for NFAT-driven RFP are indicated by a red bar and a star (*). Analogous experiments were performed in a nominally Ca2+-free bath solution to detect the co-expression of the NFAT reporter and wild-type Orai1 or Orai1-H134A, indicated by blue bars (n = 3 – 5 cell images, each from a separate transfection).

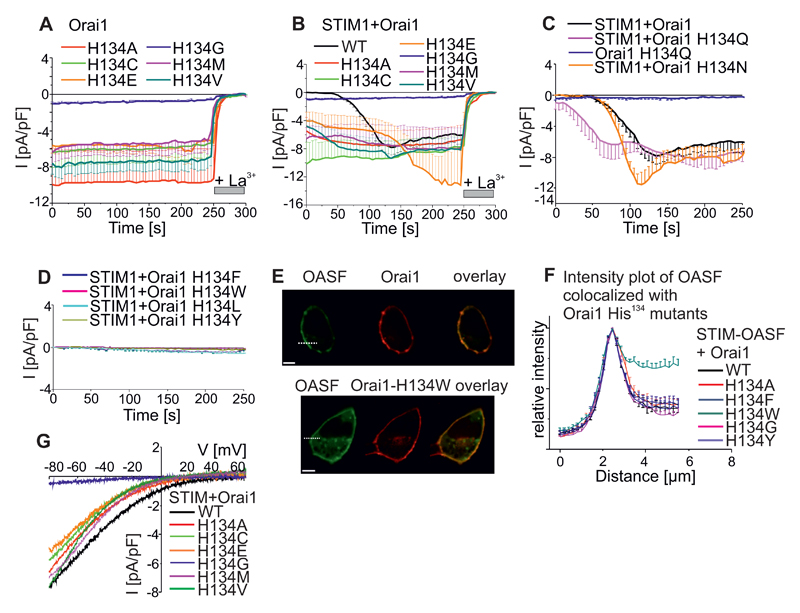

Distinct mutations of His134 induce constitutively-active, store-operated, or mainly inactive Orai1 currents

To evaluate the role of the hydrogen bonds between His134 and the pore helix more directly, we conducted patch-clamp experiments with Orai1-His134 mutants overexpressed in HEK cells. Orai1-H134A-expressing cells yielded large, constitutive, inward currents immediately after whole-cell break-in (Fig. 3A). The maximum currents measured for Orai1-H134A did not increase further when STIM1 was co-expressed and were comparable to those of wild-type STIM1/Orai1-mediated channel activity (Fig. 3B). Electrophysiological analysis indicated that the Orai1-His134 point mutants were either constitutively active, store-dependent, or mainly inactive. Similar to the mutants assessed with the NFAT reporter (Fig. 2F), the first group of constitutively active Orai1-His134 mutants (with substitutions of Ala, Cys, Glu, Gly, Met, or Val) were not further activated upon STIM1 co-expression and store-depletion (Fig. 3B). However, Orai1-H134E currents were additionally enhanced by this store-operated protocol (Fig. 3B). The second group of store-dependent Orai1-His134 mutants consisted of Orai1-H134N and Orai1-H134Q. Orai1-H134Q exhibited mild constitutive activation and both Orai1-H134N and Orai1-H134Q exhibited enhanced store-dependent activation (Fig. 3C). The third group of mutants with strongly reduced, store-dependent activation mainly had large, hydrophobic side-chain substitution at His134 (Phe, Trp, Tyr, Leu) (Fig. 3D). Orai1-H134W showed reduced binding affinity to an ORAI1-activating small fragment (OASF) from the C-terminus of STIM1, which is sufficient for Orai1 activation (7, 36) (Fig. 3E,F, S3A), implying that the Trp134 mutation induced larger structural rearrangements than other mutations. Apart from the drastic effect of the Orai1-H134A mutation on gating, the current of this mutant remained Ca2+-selective (Vrev ~ +40mV, Fig. 3G, Table S1). Of all the constitutively-active Orai1-His134 mutants, Orai1-H134V mediated the lowest amount of Ca2+-selective current (Vrev ~ +10 mV). Compared to the Ca2+-selective, constitutively-active Orai1-H134A mutant described here, the Orai1-V102C and Orai1-G98D mutants that have been previously reported are less selective (~ +20 mV (22) and ~ 0mV (25), respectively). In the presence of STIM1, the Ca2+-selectivity of constitutively-active Orai1 His134 mutants was increased (Table S1, Fig. S3B,C) in a similar, but less pronounced, way as for Orai1-V102A (22). Orai1 His134 mutants that remained STIM1- and store-dependent exhibited Ca2+-selectivity (Vrev ~ +60mV) similar to that exhibited by wild-type Orai1 (Table S1). In addition, we investigated whether the constitutively-active Orai1-L138F mutant related to myopathy could be reversed into an inactive state upon mutating Ala138. Indeed, Orai1-L138A was targeted to the plasma membrane (Fig. S3D), but lacked current activation upon STIM1 co-expression and store-depletion (Fig. S1E). Thus, we identified the His134 residue in TM2 as a hydrogen-bond-dependent trigger that gates Orai1 channels and stimulates Ca2+-dependent gene transcription.

Figure 3. His134 mutations switch Orai1 between generating constitutively-active, store-dependent, or suppressed currents.

(A) Time course of whole cell patch-clamp recordings of HEK cells overexpressing Orai1 His134 (Ala, Cys, Glu, Gly, Met, Val) mutants. These mutants show constitutive activity (n = 7 – 14 cells, from at least 2 individual transfections). (B) Analogous experiments to those conducted on Orai1 His134 mutants as in (A) or wild-type Orai1 co-expressed with STIM1 (n = 7 – 14 cells, from at least 2 individual transfections). (C,D) Time courses for store-dependent activation for Orai1 His134 (Gln, Asn) mutants or wild-type Orai1 coexpressed with STIM1 (D) or reduced currents generated by Orai1 His134 (Phe, Trp, Tyr, Leu) coexpressed with STIM1 (n = 6 – 14 cells, from at least 2 individual transfections). All currents were recorded at -86 mV in a 10 mM Ca2+-containing bath solution and store-depletion was induced by 20 mM EGTA in the pipette. (E) Representative images of CFP-OASF and YFP-Orai1 wild-type (upper panel) and Orai1-H134W mutant (lower panel). Scale bar, 10 µm. (F) Intensity plots for regions close to the plasma membrane measured at the dashed lines for individual cells(E) (n= 4 – 16 cells, from at least 2 individual transfections). (G) Representative current-voltage relationships for maximum currents of Orai1 His134 mutants of (A) are shown.

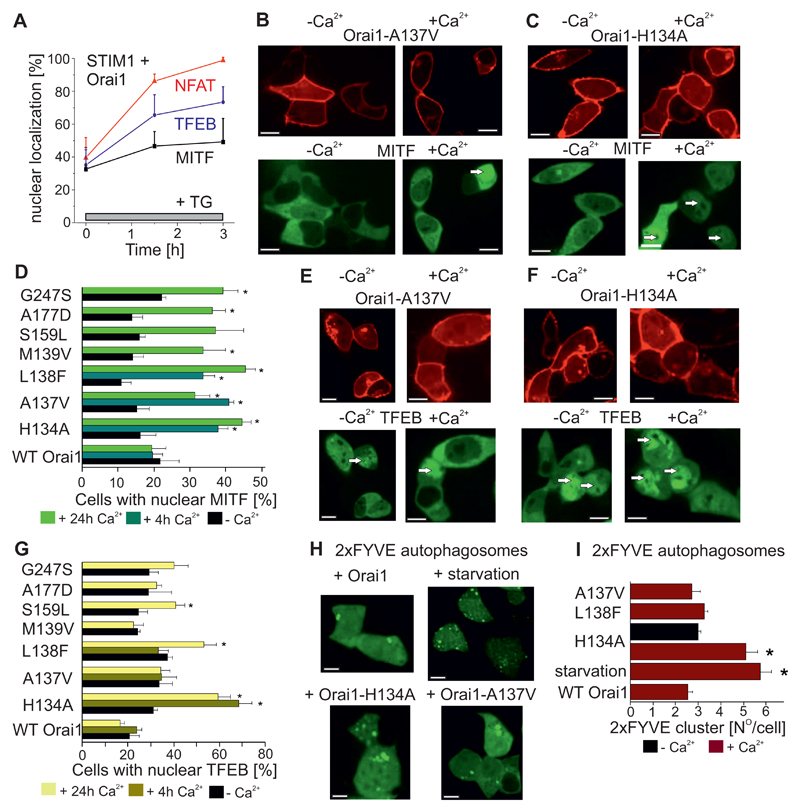

Constitutively-active Orai1 mutants identified from the cancer database activate the Ca2+-dependent transcription factor MITF and the open Orai1-H134A channel also induces autophagy

The constitutive Ca2+ entry mediated by the Orai1 mutants would be expected to have broad-ranging effects on Ca2+-dependent gene regulation, in addition to NFAT signalling. High cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations are toxic to cells; however, overexpression of the constitutively-active Orai1 mutants identified through the cancer database screen, the myopathy mutant, or the H134A mutant did not significantly enhance cytotoxicity (Fig. S4A). The phosphatase calcineurin not only activates NFAT but also the transcription factor EB (TFEB) (37). TFEB and the closely related MITF (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) translocate from the cytosol into the nucleus upon cell starvation (Fig. S4B) to activate genes involved in autophagy and mitophagy (37, 38). The constitutive nuclear localization and dysfunctional gene regulation of MITF and TFEB serve as oncogenic drivers for pancreatic cancer metabolism (39, 40). For these reasons, we asked whether either the constitutively-active Orai1 mutants activated other calcium-regulated transcription factors in addition to NFAT. In HEK cells coexpressing STIM1 and Orai1 in a bath solution containing 2 mM Ca2+, thapsigargin treatment to trigger store-operated Ca2+ entry induced complete nuclear translocation of CFP-tagged NFAT (12) and varying degrees of nuclear translocation of CFP-TFEB and CFP-MITF (Fig. 4A). Next, nuclear translocation of MITF (Fig. 4B-D) and TFEB (Fig. 4E-G) was evaluated in HEK cells overexpressing the constitutively-active Orai1 mutants in the presence or absence of external Ca2+. The bath solution containing 2 mM Ca2+ did not increase MITF nuclear translocation in cells expressing wild-type Orai1 (negative control), but induced MITF nuclear localization in almost half of the cells that expressed Orai1-L138F and Orai1-H134A (Fig. 4D). In the presence of external Ca2+, cells expressing the constitutively-active Orai1 cancer database mutants or the Orai1-L138F myopathy mutant showed significantly-increased nuclear MITF localization but not TFEB nuclear translocation even after 24h. Cells expressing Orai1-H134A alone showed TFEB nuclear translocation after only four hours after exposure to Ca2+-containing media. TFEB is a master regulator of autophagy (41) and starvation induced clear autophagosome formation as determined by the PIP3 reporter GFP-2xFYVE (Fig. 4H,I). Of the constitutively-active Orai1 mutations tested, only the overexpression of Orai1-H134A induced autophagosome formation in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Fig. 4H, I). These results show that the Ca2+ signals induced by several Orai1 mutants identified through cancer database screening are uncoupled from physiological stimuli and activate MITF and NFAT transcription.

Figure 4. Activation of auto- and mitophagy transcription factor by Orai1 mutants identified via cancer database screening and myopathy mutants.

(A) Time course of transcription factor activation by thapsigargin (TG) treatment (1 µM, 5 min) as measured by cytosol-to-nuclear translocation for NFAT (red), TFEB (blue) and MITF (black) in STIM1 and Orai1 co-expressing HEK cells (n = 6-8 cell images, each from 3 separate transfections). (B, C) Representative images of HEK cells co-expressing YFP-tagged Orai-A137V (B) or YFP-tagged Orai-H134A (C) and CFP-MITF in the absence or presence of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+. Scale bar, 10 µm. (D) Average number of HEK cells exhibiting nuclear MITF localization upon co-expression with cancer-associated Orai1 mutants, a myopathy-associated Orai1-L138F mutant or the Orai1-H134A mutant determined after 24 hours with or without 2 mM Ca2+ in the media (n = 6 – 8 cell images, each from 3 - 5 separate transfections). Additional bar indicates similar experiments in which cells were exposed to a Ca2+-containing media for 4 hours (n = 6-8 cell images, each from 3 separate experiments). Significantly increased (p < 0.05 by t-test) nuclear localization of MITF induced by Orai1 mutants with respect to Ca2+ in the media is indicated by a star. (E,F) Representative images of HEK cells co-expressing YFP-tagged Orai-A137V (E) or Orai-H134A (F) and CFP-TFEB in the absence or presence of 2 mM extracellular Ca2+. (G) Average number of HEK cells exhibiting nuclear TFEB localization upon co-expression with wild-type Orai1, Orai1-L138F, Orai1-A137V, or Orai1-H134A determined after 24 hours with or without 2 mM Ca2+ in the media (n = 3 – 5 cell images, each of individual transfection). Additional bar indicates similar experiments in which cells were exposed to Ca2+-containing media for 4 hours (n = 6-8 cell images, each from 3 separate transfections). Significantly increased nuclear localization (p < 0.05, t-test) of TFEB induced by Orai1 mutants with respect to Ca2+ in the media is indicated by a star (*). (H) Autophagosomes were visualized by GFP-2xFYVE in HEK cells expressing YFP-tagged wild-type Orai1, Orai1-H134A, or Orai1-A137V. Scale bar, 10 µm. (I) Quantification of the average number of GFP-2xFYVE clusters in the presence or absence of 2 mM Ca2+ in the bath (n=70-90 cells, from 3 individual transfections). Significantly increased (p < 0.05 by t-test) autophagosome formation is indicated by a star (*).

The constitutively-active Orai1-H134A mutant shows locally-increased pore size

To understand how TM2 mutations mechanistically induce Orai1 channel gating, we initially focused on Orai1-H134A, because this mutant exhibits both substantial Ca2+ selectivity and high constitutive activity. Furthermore, pharmacological characterization revealed that application of the potent Orai1 channel blocker, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) (42), also inhibited Orai1-H134A currents (Fig. S5A). Moreover, in the presence of STIM1, Orai1-H134A showed fast inactivation to a similar extent (Fig. S5B) as wild-type Orai1. However, Orai1-H134A currents lacked fast inactivation in the absence of co-expressed STIM1, further highlighting the key-role played by STIM1 in fast inactivation (43–45) (Fig. S5B).

Molecular dynamics simulations of wild-type Orai1 (12) (Fig. 5A,B) and Orai1-H134A (Fig. 5B,C) in a lipid bilayer were performed to visualize structural changes that occurred upon gating. Two gating sites have been identified in the pore (21, 22, 46): A hydrophobic gate mainly formed by Val102 and Phe99 and a basic gate predominantly formed by Arg91. Homology modelling revealed that human wild-type Orai1 had a similar pore profile to that of the drosophila Orai1 (dOrai1) channel (Fig. S6, A to C). In the 200ns molecular dynamics simulations performed for the human wild-type Orai1, the obtained pore structure remained unaltered. Molecular dynamics simulations for Orai1-H134A showed that the pore for the mutant had small but essential configuration changes within the pore. The selectivity filter formed by the pore-lining Glu106 residues of both mutants was maintained (Fig. 5A-C) with a bound Ca2+ ion. However, the pore helical segment that includes the selectivity filter was more rigid in Orai1-H134A simulations, based on backbone flexibility measurements (Fig. 5D). The central hydrophobic pore segment formed a narrow part of the wild-type Orai1 pore and was slightly widened in the Orai1-H134A simulation (Fig. 5A-C). In wild-type Orai1 simulations, the most rigid segment of the pore helix (Fig. 5D) was composed of Arg91 side-chains. These arginine residues were oriented towards the centre of the pore and formed the narrowest part of the pore surface (Fig. 5A,B). This rigid structure (Fig. 5D) forced the Arg91 side-chains to face inward into the pore and overcame their electrostatic repulsion. Unlike wild-type Orai1, the basic pore segment of the Orai1-H134A channel exhibited increased flexibility (Fig. 5D). This increased backbone flexibility had important consequences in that it extended the radius of the basic pore segment by 1-2 Å. The more cytosolic portion of the pore segment had a radius similar to that of wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 5B), which showed a local displacement of Arg91 without an additional overall pore extension. These simulations provided evidence that Arg91 functions as a gate in the Orai1 channel. Mutations in Arg91 have been proposed to be pathophysiologically relevant because patients carrying the Orai1-R91W mutation suffer from severe combined immunodeficiency symptoms (1). Trp91 side-chains project into the pore and extend the hydrophobic barrier in Orai1 to completely block Ca2+ permeation (21). Instead, an Orai1-G98D-R91W double mutant shows constitutive Ca2+ influx. Hence, the G98D mutation induces a greatly extended pore that overcomes the hydrophobic barrier of Trp91. Patch-clamp experiments revealed that an engineered Orai1-H134A-R91W double mutant did not generate Ca2+ currents (Fig. S7A), similar to a previously studied Orai1-V102A-R91W mutant (22). Hence, the opened Orai1-H134A pore is not as greatly altered as the Orai1-G98D pore, and remains more Ca2+-selective than the Orai1-V102A pore.

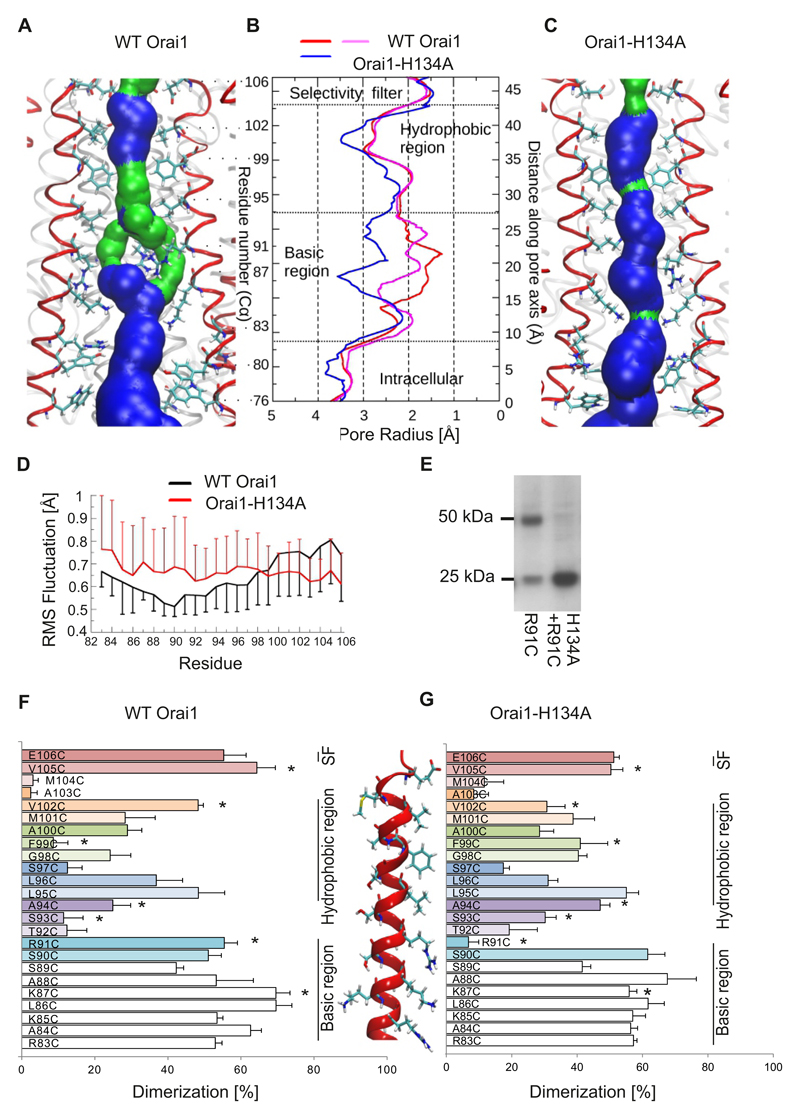

Figure 5. Increased pore size in the open conformation of Orai1-H134A channels.

(A,C) Representative snap shot (time point at 192 ns) of the equilibrated part of 200 ns long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1 (A) or Orai1-H134A (C) showing the pore forming TM1 helices (4 out of 6 TM1 helices shown in red) and pore lining residues from Glu106 to Trp76. The pore surface is shown in blue (radius > 1.15Å) and in green (radius is between 0.6 to 1.15Å). (B) Average pore radius of wild-type Orai1 (red and magenta) and Orai1-H134A (blue) for a 2 ns bin corresponding to the time points shown in A and C. (D) Fluctuations of individual TM1 residues of (black) wild-type Orai1 and (red) Orai1-H134A are measured as the root mean square (RMS) deviation of Cα atom for the last 50 ns of the 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations. (E) Representative western blot of a crosslinking experiment overexpressing Orai1-R91C and Orai1-H134A-R91C showing monomer and dimer formation. (F, G) Dimerization efficiency in (%) of cysteine crosslinking for engineered cysteines (R83C to E106C) in the (F) wild-type Orai1 or (G) Orai1-H134A TM1 pore segment. A cysteine-free Orai1 background was used. For each cysteine position, parallel experiments (n = 5 - 8 individual transfection for each cysteine position) with wild-type Orai1 and Orai1-H134A background were performed on the same day, and significant differences (t-test, p < 0.05) are indicated by a star (*).

To experimentally evaluate the differences in the pores of the wild-type Orai1 and Orai1-H134A channels, we used a systematic cysteine scanning approach with wild-type Orai1 and Orai1-H134A. Efficient crosslinking between cysteines at specific residues in TM1 provides evidence for their close proximity in the channel pore (12, 47). We engineered single cysteine substitutions within the Orai1 pore-forming TM1 helix (Arg83 to Glu106) in a cysteine-free Orai1/Orai1-H134A background and determined the degree of dimerization. In the presence of Cu2+-phenanthroline to induce cysteine crosslinking, the cysteine-free Orai1 or Orai1-H134A remained monomers, while single cysteine substitutions resulted in both monomeric and dimeric bands, dependent on their position in the channel (Fig. 5E-G). We found that the highest degree of dimerization of pore-lining Orai1 residues occurred at positions Glu106, Val105, Val102, Leu95 and Arg91 and Ser90, which are separated by stretches of residues that show less reactive cysteine crosslinking (Fig. 5F). These findings suggest a pore facing position of these residues in agreement with results from our Orai1 molecular dynamics simulations, the crystal structure of the dOrai pore and previous results (21, 47, 48). Furthermore, analysis of the atomic dOrai structure (21) allowed the identification of Phe99 as an additional constriction site, while the results from previous studies and our cysteine scanning approaches suggested that Gly98 is located closer to the centre of the pore (47, 48) (Fig. 5F). Next, taking an analogous cysteine scanning approach, we determined the channel conformation of the constitutively-active Orai1-H134A mutant. As in wild-type Orai1, efficient cysteine crosslinking (Glu106, Val105) included the selectivity filter, as well as Leu95. Crosslinking of V105C and V102C (Fig. 5G) was significantly reduced compared that in wild-type Orai1 with identical mutations. As in our molecular dynamics simulations, a decrease in the side-chain flexibility of these cysteines would interfere with crosslinking efficiency (Fig. 5D). The middle segment of the Orai1-H134A pore (Phe99 to Ser93) exhibited overall enhanced amounts of crosslinking (Fig. 5G, which was significant for F99C, G98C, A94C and S93C) that agreed with the enhanced flexibility observed within the open pore in molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 5D). The largest difference in crosslinking was observed for R91C and F99C. R91C cross-linked in wild-type Orai1 but not in the Orai1-H134A mutant (Fig. 5E-G). Instead, F99C dimerized only in the Orai1-H134A mutant. The altered flexibility of the side-chains is presumably not the only factor contributing to the difference observed for R91C. Instead, these results suggest that the R91C side-chains are differently oriented in the open channel conformation. Molecular dynamics simulations of Orai1-H134A also showed an increased pore size at Arg91 (Fig. 5B) and an increased distance between the side-chains compared to wild-type Orai1 (Fig. S7B). Overall, these results indicate that wild-type Orai1 and Orai1-H134A have similar pores with two local, but essential, conformational changes: increased pore diameters in the hydrophobic segment and the segment near Arg91. Such small changes upon Orai1 gating are expected to retain some structural restrictions within the pore and explain the extraordinarily low femto Siemens (fS) conductance of Ca2+ ions in Orai1.

Gating in the Orai1-H134A channel is mediated by a switch in the position of Arg91 side-chains

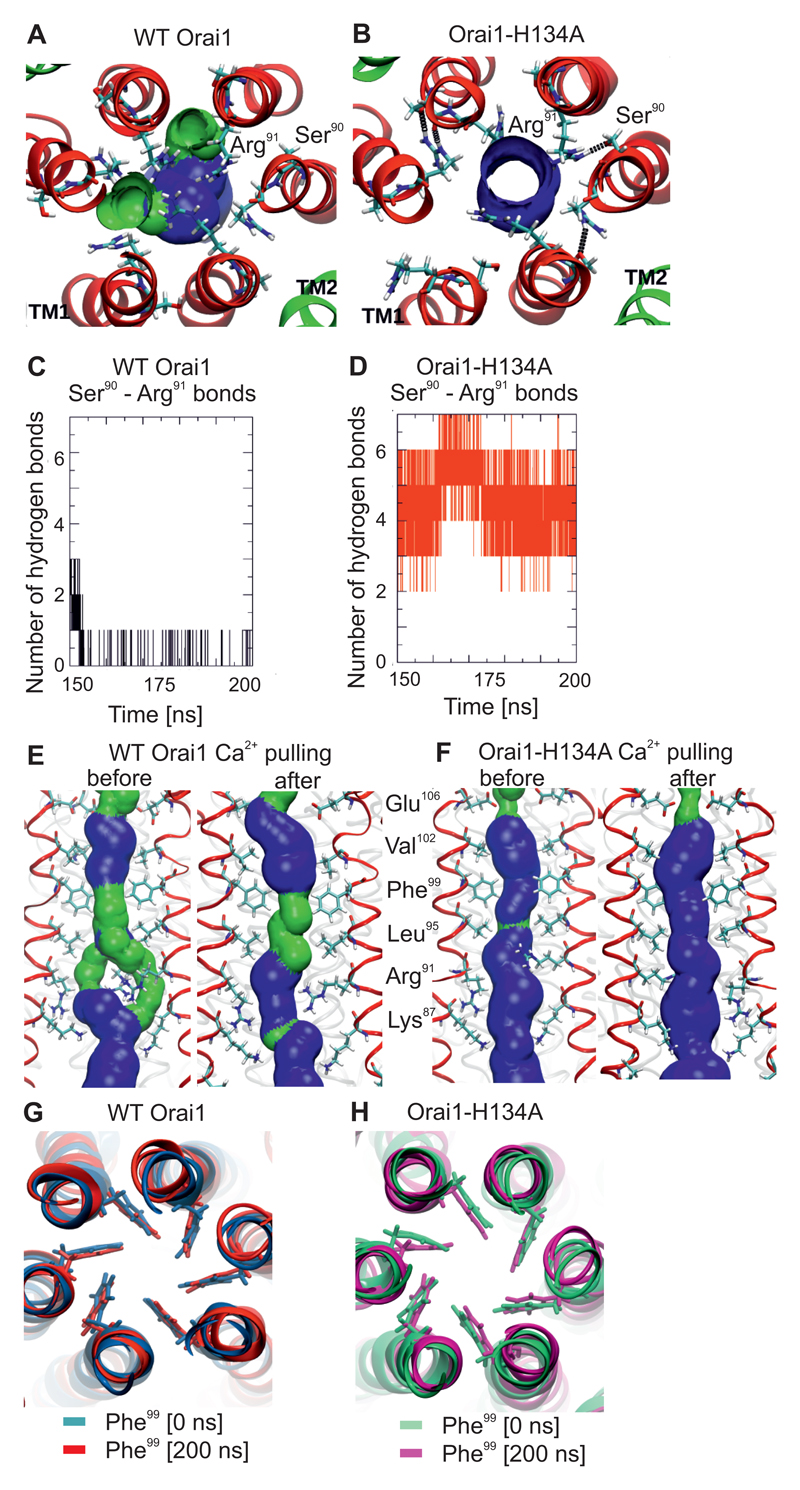

Closer inspection of the Arg91 residue in the wild-type Orai1 simulations revealed that three side-chains were constantly positioned in the centre of the pore (Fig. 6A, S8A). In contrast, in the Orai1-H134A simulations, all Arg91 side-chains were twisted toward the outside of the pore (Fig. 6B, S7B) to form hydrogen bonds with the backbone or side-chain of Ser90. These hydrogen bonds were rare in wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 6A,B) but occurred frequently in Orai1-H134A channels, with almost all Arg91 side-chains bound to Ser90 in the simulations (Fig. 6C,D). Furthermore, we used steered molecular dynamics to assess how the Arg91 side-chains were affected when a single Ca2+ ion was pulled through the pore of either wild-type Orai1 (Fig. S8A, C, Movie S1) or Orai1-H134A (Fig. S8B, D). In wild-type Orai1, the Arg91 side-chains switched their position, moving out of the pore centre when Ca2+ crossed (Fig. S8C) and creating a larger pore surface (Fig. 6E). This conformation is strikingly similar to that in the Orai1-H134A pore (Fig. 6E,F). When Ca2+ was pulled through the Orai1-H134A pore, the position of the Arg91 side-chains was largely unaffected, as this channel had already adopted a Ca2+-permeable configuration (Fig. 6F, S8B,D). The force that was required to pull a Ca2+ ion through Arg91 was also higher for the wild-type Orai1 as compared to the Orai1-H134A pore (Fig. S8E). Hence, the results of these experiments indicate the large positive charge of Arg91 side-chains contribute to hindered permeation in wild-type Orai1, and that a gating trigger site located at TM2 opens the Arg91 gate.

Figure 6. Side-chain twist of the Arg91 gate induced by constitutively-active Orai1-H134A channels.

(A,B) Representative snap shot of the equilibrated part of the 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1 (A) and Orai1-H134A (B) showing the position of Arg91 residues and Ser90 in the TM1 helices, which are surrounded by TM2 helices (His134 or Ala134 respectively shown) from a top view. (C, D) Hydrogen bonds between Arg91 and Ser90 in wild-type Orai1 (C) and the Orai1-H134A simulations (D) in a time-course (150 to 200 ns). (E,F) Comparison of pore surfaces of wild-type Orai1 (E) and Orai1-H134A (F) before and after Ca2+ is pulled through the pore. The pore surface is shown in blue (radius > 1.15Å) and green (radius is between 0.6 to 1.15Å). (G,H) Representative snap shots of the start and end of 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1 (G) and Orai1-H134A (H) illustrates the position of Phe99 residues in the pore helix.

Formation of a water molecule chain in the constitutively-active Orai1-H134A decreases hydrophobic gating barriers

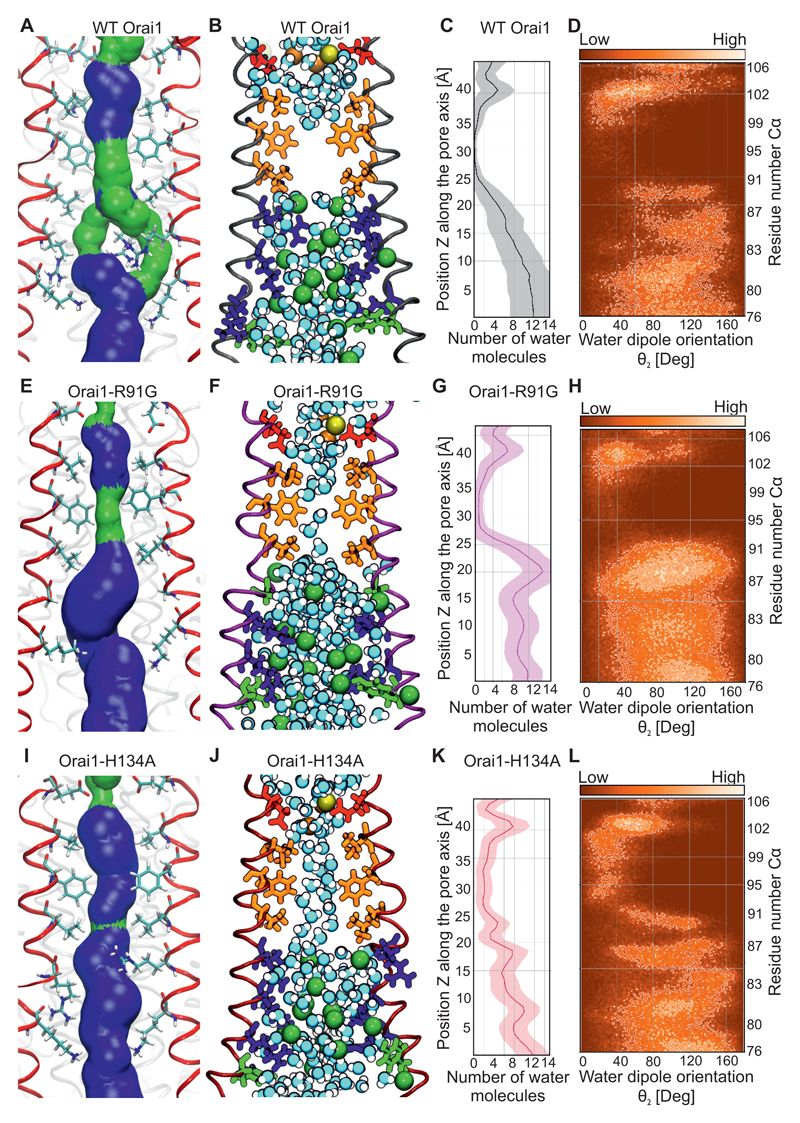

Is the Arg91 side-chain switch alone responsible for Orai1 channel gating? A helix turn that mainly affects the hydrophobic pore segment of the Orai1 channel has been reported as a main mechanism for STIM1 dependent channel gating (23). However, in all our simulations of various human wild-type Orai1 and mutants, the pore helix orientation was unaltered (Fig. 6G, H, S9A). To further address this question, we focused on the effects of substituting a small glycine at Arg91. This Orai1-R91G mutant lacks constitutively active Ca2+ permeation even with a small side-chain substitution of the Arg91 gate (24, 46). To compare the roles of Arg91 and the hydrophobic side-chains in gating, the wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 7A-D), Orai1-R91G mutant (Fig. 7E-H), and Orai1-H134A (Fig. 7I-L) were examined in molecular dynamics simulations. The pore size around the Arg91 position was more extended in Orai1-R91G channels than in Orai1-H134A, indicating that the increased space around Arg91 was not enough to exclusively gate Orai1 channels. In the hydrophobic pore segment, Orai1-R91G exhibited a similar arrangement of pore lining residues (Fig. 7E) as wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 7A). The hydrophobic pore segment of the Orai1 mutant and wild-type channels completely lacked any ions (Fig. 7B,F,J, Fig. S9B-D). In the wild-type and mutant Orai1 channels, Ca2+ and Na+ ions were present close to the selectivity filter and the extracellular CAR region (12), and several Cl- ions were present within the basic pore segment. In wild-type Orai1, water molecules were absent from the hydrophobic pore segment during most of the simulation time (Fig. 7B,C), and only single water molecules were observed within the Orai1-R91G channel (Fig. 7F,G). In contrast, the slight pore size increase observed in Orai1-H134A channels resulted in the presence of a double chain of water molecules along the length of the channel (Fig. 7J,K). The presence of this water chain within the hydrophobic Orai1-H134A pore segment yielded a highly-ordered dipole moment (Fig. 7L), with hydrogen groups facing the selectivity filter of the channel. The enhanced presence of water in a constitutively-active Orai1 Val102 mutant has previously been calculated to reduce the energetic barrier for cation permeation (49). Our results indicate a chain of water molecules exclusively in the constitutively-active Orai1-H134A channels, which favours the concept of Ca2+ permeation by way of water in Orai1 channels.

Figure 7. Formation of a chain of water molecules in the hydrophobic pore segment of Orai1-H134A.

(A,E,I) Representative snap shots of the equilibrated part of 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1 (A), Orai1-R91G (E) and Orai1-H134A (I) showing the pore forming TM1 helices (4 out of 6 TM1 helices shown in red) and pore lining residues from Glu106 to Lys87. The pore surface is shown in blue (radius > 1.15Å) and green (radius: 0.6 to 1.15Å). (B,F,J) Similar snap shots for wild-type Orai1 (B), Orai1-R91G (F) and Orai1-H134A (I) showing the water molecules, Ca2+ (yellow ball), Na+ (orange ball) and Cl- (green ball) in the pore. Acidic residues, non-polar residues, basic residues and polar residues are depicted in red, orange, blue and green, respectively. (C,G,K) Average number and standard deviation (shaded area) of water molecules (over the last 100 ns of respective simulations) inside the pores of wild-type Orai1 (C), Orai1-R91G (G) and Orai1-H134A (K) channels are calculated. (D,H,L) Water orientation inside the pores of wild-type Orai1 (D), Orai1-R91G (H) and Orai1-H134A (L) channels are determined as defined by the angle between the dipole vector of the water molecule and the z axis. Water molecules that locally are similarly oriented within the respective pores are depicted in brighter colors.

Partially-active Orai1 mutants display similar but less pronounced gating conformation

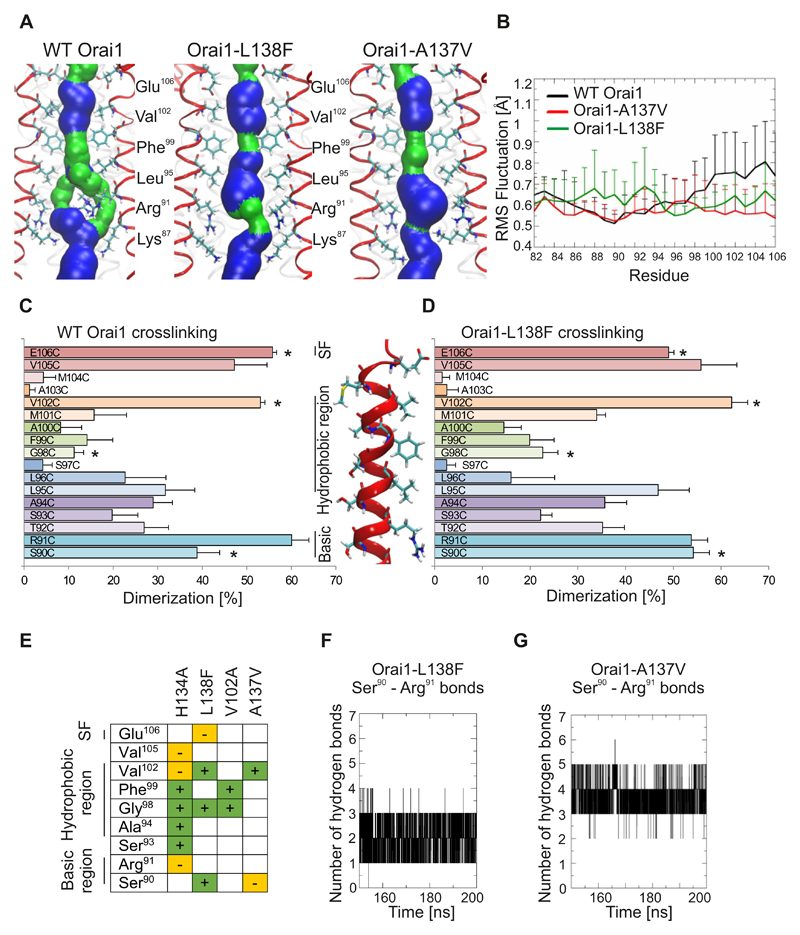

The concept of two gating sites, a hydrophobic and an Arg91 gate, was further investigated in the patho-physiologically relevant Orai1-L138F mutant and in Orai1-A137V because they showed limited Ca2+ permeation. Molecular dynamics simulations of Orai1-L138F and Orai1-A137V indicated that the pore lining residues were conserved as in wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 8A). Still, the surface constriction of the hydrophobic part was shortened in Orai1-L138F and the pore surface increased around Arg91 in both mutants (Fig. 8A). No pore helix rotations were observed in these mutants. The backbone flexibility was decreased in the hydrophobic part of both Orai1 mutants, and the flexibility of the basic segment increased in Orai1-L138F, in a similar way as to that previously observed in Orai1-H134A (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Pore rearrangements in Orai1 mutants related to myopathy and identified by cancer database screening.

(A) Representative snap shots of the equilibrated part of 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1, Orai1-R91G and Orai1-H134A showing the pore forming TM1 helices (4 out of 6 TM1 helices shown in red) and pore lining residues from Glu106 to Lys87. The pore surface is shown in blue (radius > 1.15Å) and green (radius: 0.6 to 1.15Å). (B) Differences among individual TM1 residues for wild-type Orai1, Orai1-A137V and Orai1-L138F are measured as root mean square (RMS) deviation of Cα atom for the last 50 ns of 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations. (C,D) Dimerization efficiency (%) of cysteine crosslinking for engineered cysteines (S90C to E106C) in the wild-type Orai1 (C) and Orai1-L138F (D) TM1 pore segment. For each cysteine position, wild-type Orai1 and Orai1-L138F mutations were performed on the same day (n = 5 – 8 transfections for each cysteine position), and significant differences (t-test, p < 0.05) are indicated by a star (*). (E) The crosslinking results Orai1-H134A, Orai1-L138F, Orai1-V102A and Orai1-A137V as compared to wild-type Orai1. + and green, significantly-increased crosslinking. – and orange, significantly-decreased crosslinking. (F,G) The time course depicts the number of hydrogen bonds formed between residues Arg91 and Ser90 for last 50 ns of the Orai1-L138F (F) and Orai1-A137V (G) simulations.

To experimentally address these alterations, we carried out cysteine scanning experiments on Orai1-L138F (Fig. 8C,D), Orai1-A137V (Fig. S10A), and the constitutively-active pore mutant, Orai1-V102A (Fig. S10B). All three Orai1 mutants (L138F, A137V, V102A) exhibited similar crosslinking profiles as wild-type Orai1, experimentally supporting the hypothesis that pore lining residues are conserved. These results, as well as those of the molecular dynamics simulations, provide support for our hypothesis that local rather than global rearrangements affect Orai1 channel gating in the constitutively-active mutants. Moreover, fewer cysteine positions resulted in significantly-altered crosslinking compared to those of Orai1-H134A, a result that agrees with the partial activity of these Orai1 mutants. Significantly-increased dimerization of residues mainly occurred in the hydrophobic segment between Val102 to Gly98 (Fig. 8E, Fig. S10A,B). Instead, crosslinking of Arg91 was unaltered in all three Orai1 mutants. Still, Orai1-L138F (Fig. 8F) and Orai1-A137V (Fig. 8G) exhibited increased binding between Arg91 and Ser90 compared to wild-type Orai1 but reduced binding compared to Orai1-H134A, suggesting the presence of a partially active Arg91 gate.

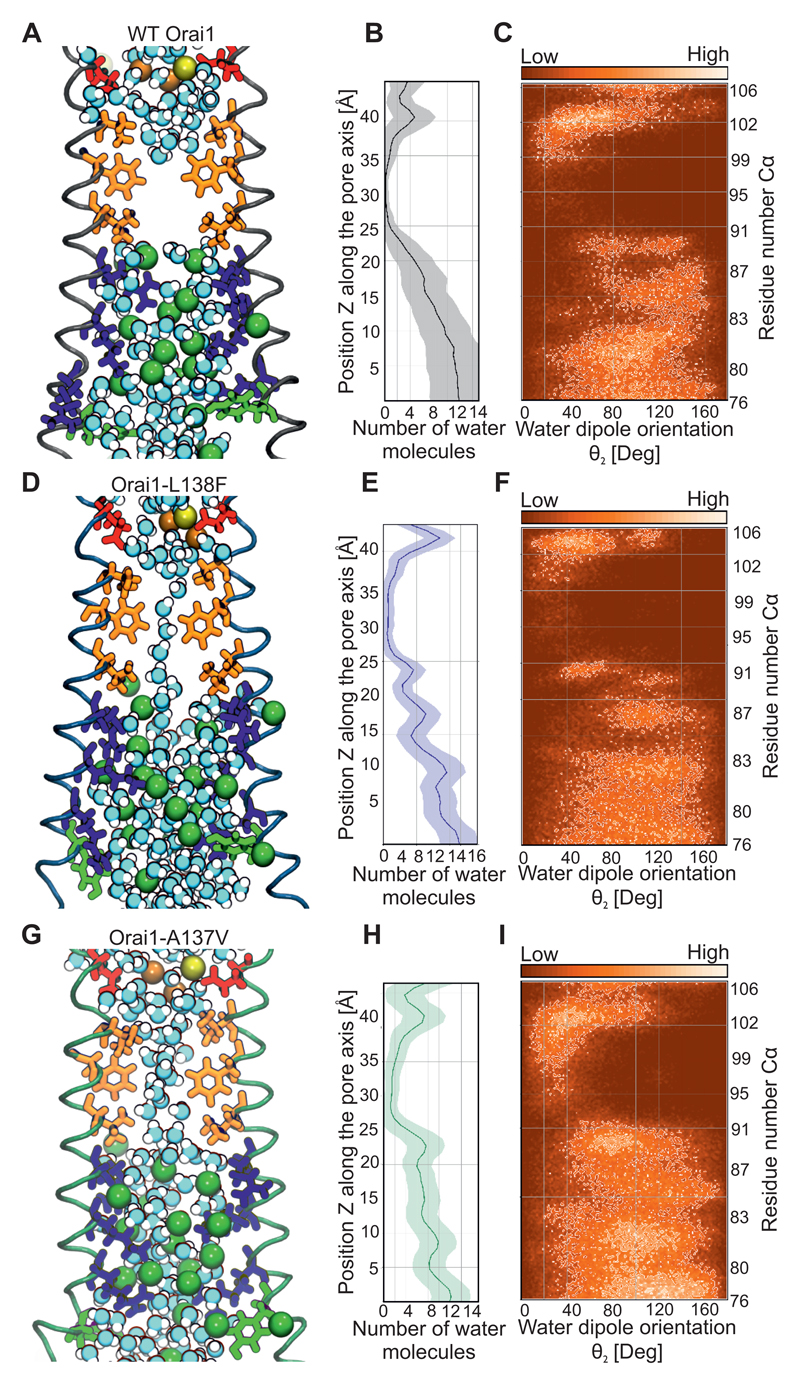

The hydrophobic pore gating site was evaluated by visualizing the chain of water molecules and its orientation in wild-type Orai1 (Fig. 9A-C), Orai1-L138F (Fig. 9D-F) and Orai1-A137V (Fig. 9G-I). A single chain of water molecules was visualized in the hydrophobic part in the Orai1-L138F channel (Fig. 9D, E), while water molecules formed a double-chain in the Orai1-A137V channel (Fig. 9G, H), similar to the Orai1-H134A channel (Fig. 6F). The water molecules showed dipole orientation within the hydrophobic part of the pore (Fig. 9C, F,I) The dynamic movement of water molecules within the wild-type Orai1 and mutants (Orai1-H134A, Orai1-L138F, Orai1-A137V, Orai1-R91G) was determined by measuring the water survival probability in restricted segments of the selectivity filter, the hydrophobic and basic parts of these channels (Fig. S11). In simulations for all channels, water molecules left the hydrophobic part quickly (Fig. S11). In contrast, water molecules remained longest near the basic segment, presumably due to orientation of Cl- ions and positively-charged side-chains. The absence of Arg91 side-chains accelerated the water mobility in the Orai1-R91G channel (Fig. S11). Thus, two gates control the channel activity in the constitutively active Orai1 mutants. The open channel configuration is less pronounced in the partially active Orai1 channels. Hence, these experiments provide evidence for a TM2-located gating trigger that controls Ca2+ permeation of Orai1 channels by two distinct gates.

Figure 9. Water permeation in Orai1 mutants related to myopathy and identified through cancer database screening.

(A,D,G) Representative snap shots of the equilibrated part of 200-ns-long molecular dynamics simulations for wild-type Orai1 (A), Orai1-L138F (D) and Orai1-A137V (G) illustrates the pore-forming TM1 helices (4 out of 6 TM1 helices) and pore-lining residues from Glu106 to Phe76. Water molecules, Ca2+ (yellow ball), Na+ (orange ball) and Cl- (green ball) are shown in the respective pores. (B,E,H) Average number and standard deviation (shaded area) of water molecules (over the last 100 ns of respective simulations) lining the pores of wild-type Orai1 (B), Orai1-L138F (E) and Orai1-A137V (H) are calculated. (C,F,I) Water orientation lining the pores of wild-type Orai1 (C), Orai1-L138F (F) and Orai1-A137V (I) are determined as defined by the angle between the dipole vector of the water molecule and the z-axis. Water molecules that are locally oriented in a similar way within the respective pores are indicated by brighter colours.

Discussion

Systematic analysis of Orai1 large-scale cancer genomics data identified five constitutively active Orai1 mutants, derived from various human cancers. The increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations caused by these Orai1 mutations resulted in activation of NFAT and MITF without requiring physiological stimuli. The transcription factor MITF and TFEB remain in the cytosol because of phosphorylation by MTOR and translocate into the nucleus upon starvation or other stimuli (39). Although Ca2+ efflux from lysosomes activates these transcription factors under physiological conditions (37), constitutively active Orai1 mutants can bypass this signalling cascade due to overall enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. Our work on the Orai1 channel may serve as a template for investigating cancer-associated mutations in many Ca2+ signalling proteins. Hence, the mutations in a Ca2+ channel characterized here could serve as an additional point of investigation in addition to assessing the abundance of Ca2+ channels and downstream signalling proteins in cancer biology.

The localization of three Orai1 mutations derived from the cancer database or associated with myopathy (A137V, L138F, M139V) within the TM2 helix directly pointed to a structural site that controls Orai1 channel gating. In particular, His134 was identified to frequently interact with the pore helix residues Ser93 and Ser97. Omission of one His134 related hydrogen bond per Orai1 subunit initiated gating by switching the channel to an open conformation. Conversely, large hydrophobic substitutions of His134 locked the channel in its closed conformation and STIM1 overexpression and store-depletion were largely insufficient to induce Ca2+ permeation. Hence, the presence and absence of His134 hydrogen bonds is critical for the transition between closed and open channel conformations. Substitutions of A137V and L138F increased the hydrophobic contacts between the regulatory TM2 site and the pore helices, thereby switching the Orai1 channel in a partially active conformation. Therefore, our experiments show that the constitutively active Orai1 mutations (H134A, A137V and L138F) are part of a trigger site that resides in TM2 and gates Orai1. The His134 trigger is likely mandatory for STIM1 induced Orai1 gating as well, as the closed conformation induced by large hydrophobic His134 substitutions was not altered by STIM1. Coupling of STIM1 to the Orai1 channel might alter the transmembrane connectivity by directly binding to the N- and/or C-terminus of the channel (50–53), transmitting a force to the Orai1 channel that could destabilize the TM2-pore helix interactions and switch the channel to an open conformation. Binding of STIM1 to the N-terminus could be a direct way to induce such a conformational change (8, 50–52). In contrast, an interaction of STIM1 to the C-terminus may require a cascade of local conformational changes, including uncoupling of the TM3 helix from the nexus region, a loop connecting TM4 and the C-terminus (53). Mutations within the nexus region result in constitutive Orai1 channel activity. Additionally, any mutation of Pro245 within TM4 results in constitutive Orai1 Ca2+ entry (54). This proline controls the orientation of the TM4 helix and might mimic uncoupling of the nexus region. The close connection of Gly183 with His134 might direct this conformational step further. Accordingly, mutations in Gly183 also affect Orai1 channel gating (55). Hence, these residues may provide a network to signal the docking of STIM1 to the C-terminus to the central pore.

Compared to previously investigated constitutively active pore mutants (22, 47), the Orai1 TM2 mutants allowed us to directly monitor the sequential regulation of gating sites in the pore. Moreover, the constitutively active Orai1-H134A mutant substantially retained Ca2+ selectivity even in the absence of STIM1. Gating was initiated by increased flexibility of the cytosolic pore segment, while the selectivity filter segment became more rigid. Pore helix flexibility was altered by disrupting hydrogen bonds through a H134A mutation, or by enhanced hydrophobic contacts through A137V or L138F mutations. The slight increase in hydrophobic pore size induced by these TM2 mutations caused a chain of water molecules to form in the pore. In contrast, the closed pore of wild-type Orai1 was free of any water molecules. Within the hydrophobic segment, Val102 and Phe99 have been previously characterized as a hydrophobic gate because mutation of these residues results in constitutive channel activity (22, 23). Based on earlier molecular dynamics simulations the open conformation has been reported to require a rotation of the pore helix that would switch Phe99 out of the pore centre (23). These molecular dynamics simulations differ from ours with respect to the force field used and solvent and membrane composition which apparently lead to differences in the stability of the closed wild-type Orai1 channel conformation, as we did not observe any rotation of the pore helix in our molecular dynamics simulations in the absence of an external stimuli or trigger. The wild-type Orai1 channel remained in the closed conformation as represented by the crystallized Orai channel (21).

STIM1 triggers conformational changes in Val102 and the selectivity filter (46) and restores Ca2+ selectivity in Orai1-V102A mutants (22). Simulations on an equivalent V102A mutation in the dOrai channel suggests that the energetic barrier of the hydrophobic segment is largely attenuated (49). Here, we showed that Orai1 mutations that confer constitutive activation induced the formation of chain of water molecules that would be expected to lower the energetic barrier for Ca2+ permeation. Hence our results demonstrate that the hydrophobic gate is regulated by transmembrane connectivity.

In the closed conformation of the wild-type Orai1 pore, the highly positively-charged cluster is the most rigid segment, which forces the positively-charged Arg91 side-chains to face the centre. Consequently, Ca2+ ions are efficiently repelled by this positive charge. The crystal structure of the Drosophila melanogaster Orai channel shows a negatively-charged iron-hexachloride plug interacting with Arg91 and side-chains of a positively charged cluster of residues located deeper in the pore. Cl- ions might also help to stabilize the closed conformation of the pore (21). The increased flexibility of the positively-charged pore segment in constitutively-active Orai1 mutants allows Arg91 to form hydrogen bonds with the neighbouring Ser90 residue and twist out of the pore centre. A similar twist involving Arg91 side-chains occurs when a Ca2+ ion is pulled through the wild-type Orai1 channel. This essential Arg91 gating rearrangement widens the local constriction site by 1 - 2Å and thus, reduces the positively-charged barrier. A decrease in the crosslinking of Arg91 has also been observed for an Orai1-G98P mutant that yields constitutively-active but non-selective channels (25).

The hydrophobic and Arg91 gates require minimal energetic effort to switch in the open channel conformation but retain some constriction during Ca2+ permeation. This gating mechanism therefore is expected to allow only slow Ca2+ permeation, which is indeed a hallmark of store-operated Ca2+ channels (56). Although a single gate in many ion channels is sufficient to control permeation, others have more than one gate (57). A comparison of Orai1 pore mutants that lack one of the two gates, such as Orai1-V102A and Orai1-R91G channels, indicates that the hydrophobic gate is predominant, as only the Orai1-V102A channels are constitutively active (24, 46). However, the V102A substitution lowered the energetic barrier not only of the hydrophobic gate but also the Arg91 gate to some extent (49).

In conclusion, our screen of the cancer database for Orai1 mutations revealed that a TM2 segment functions as a trigger site for Orai1 channel gating. Our results described a sequential process for Orai1 channel gating. The connectivity of the transmembrane helices directly regulated the hydrophobic and Arg91 gates. Analysis of this gating mechanism provided important insights into STIM1-induced Orai1 gating as well as Ca2+ permeation; namely, that even minute structural manipulations open the channel gate. We showed that the resulting Ca2+ signals activated the transcription factors NFAT and MITF. Hence, the results of these studies have allowed us to structurally link a trigger site in cancer- and myopathy-associated Orai1 mutations with channel gating and Ca2+-dependent gene transcription.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

N-terminally tagged Orai1 constructs (accession number NM_032790.3) were cloned into the SalI and SmaI restriction sites of pECFP-C1 and pEYFP-C1 expression vectors (Clontech). GFP-TFEB and GFP-MITF were purchased from Addgene and subcloned into peCFP vectors. hOrai1 Δ1-64, N223A, and cysteine-free (C126V, C143V, C195V) constructs were used for crosslinking as described in (12). Point mutations in Orai1 constructs were introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The integrity of all resulting mutants was confirmed by sequence analysis (Eurofins Genomics).

Transfections

HEK293T cells were transfected with Transfectin (Biorad) with 0.5 µg Orai1 constructs or mutants and 1 µg STIM1. RBL cells were electroporated with 6 µg STIM1, 6 µg Orai1 or mutants and 12 µg pNFAT-TA-mRFP. Cells were regularly tested for mycoplasm contamination.

Membrane preparation

HEK293T cells cultured in 12 cm dishes were transfected with 15 µg plasmid using Transfectin (Biorad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. 24 hours after transfection, cells were harvested and washed twice in an HBSS (Hank’s balanced salt solution) buffer containing 1 mM EDTA. After centrifugation (1000 g/2 min), cell pellets were resuspended in homogenization buffer [25 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor (Roche)] and incubated on ice for 15 min. Lysed cells were passed 10 times through a 27G ½” needle and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min at 4°C to pellet debris. 21 µl of the supernatant were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE either without or after the addition of 1 mM CuP (copper-Phenanthroline) or 5 mM BMS.

Disulphide Crosslinking

Supernatants (21 µl) were mixed with 1 mM CuSO4/1.3 mM o-phenanthroline (final concentration) (Sigma) and incubated 10 min on ice. Reactions were stopped by the addition of an equal volume of quenching solution [50 mM Tris HCl, 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.4]. Samples were mixed with nonreducing Laemmli’s buffer, heated 15 min at 55°C, and subjected to a 12% SDS PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and immunoblotted with an antibody recognizing Orai1 (Sigma). Each experiment was performed at least 5 independent times. The quantification of percentage of crosslinking was calculated with the program ImageJ (National Institute of Mental Health).

Electrophysiological recordings

HEK293T cells were transfected (Transfectin, Bio-Rad) with 1 µg mCherry-STIM1 and 0.5 μg DNA of eYFP-Orai1 constructs. Electrophysiological experiments were performed 24 to 34 hours after transfection, using the patch-clamp technique in whole-cell recording configurations at 21–25°C. An Ag/AgCl electrode was used as reference electrode. Voltage ramps were applied every 5 s from a holding potential of 0 mV, covering a range of –90 to 90 mV over 1 s. For passive store depletion, the internal pipette solution included (in mM): 145 Cs methane sulphonate, 20 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 8 NaCl, 3.5 MgCl2, pH 7.2. Standard extracellular solution consisted of (in mM) 145 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10 CaCl2, 10 Glucose, 5 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4. Na-DVF solution included 150 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10 Glucose, and 10 EDTA. A liquid junction potential correction of +12 mV was applied, resulting from a Cl−-based bath solution and a sulphonate-based pipette solution. All currents were leak corrected by subtracting the initial voltage ramps obtained shortly following break-in with no visible current activation from the measured currents or at the end of the experiment using La3+ (10µM).

Fluorescence-based Ca2+ imaging

HCT-116 cells were loaded with 1 µM Fura-2AM (in RPMI + 10%FCS + 10mM HEPES) and measurements were performed in Ringer solution containing [mM]: 155 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 10 Glucose, 5 HEPES and 2 MgCl2 + 1 CaCl2 for 1 mM Ca2+; 3 MgCl2 + 1 EGTA for 0 mM Ca2+. SOCE was triggered using 1 µM thapsigargin in Ringer solution.

Fluorescence imaging

For CFP/YFP-labelled constructs, a QLC100 Real-Time Confocal System (VisiTech Int., UK) connected to two Photometrics CoolSNAPHQ monochrome cameras (Roper Scientific) and a dual port adapter (dichroic: 505lp; cyan emission filter: 485/30; yellow emission filter: 535/50; Chroma Technology Corp.) was used for recording fluorescence images. This system was attached to an Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss, Germany) in conjunction with two diode lasers (445 nm, 515 nm) (Visitron Systems). Image acquisition and control of the confocal system was performed with Visiview 2.1.1 software (Visitron Systems). For YFP/RFP experiments an Axiovert 100 TV microscopy was used and fluorescence was recorded from individual cells with excitation of 514 and 565 nm, respectively. Extracellular solution was identical as for fluorescence microscopy.

Molecular dynamics simulations

A structural model of human Orai1 channel was obtained using homology modelling procedure as described previously in Frischauf et al. (12). Orai1 mutants were created by in silico point mutation in YASARA (58). Proteins were inserted into a pre-equilibrated palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) bilayer using the Inflategro method. The initial (closed) protein conformation was maintained in presence of cholesterol and POPC. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed in GROMACS 4.6.5 using OPLS all-atom force field as previously described in Frischauf et al.(12). Molecular dynamics simulations were run for 200 ns. The program HOLE was used for the pore dimensions analysis (59). GROMACS analysis tools (g_hbond, g_rms, g_dist) were used to calculate the number of hydrogen bonds, root mean square fluctuations and distances. VMD was utilized to visualize trajectories and for figure preparation (60). For water molecule analysis, only the water molecules contained within a cylinder of 8 Å around the centre of the pore of the Orai channel where considered. The trajectories were analysed using MD Analysis (61) and the water analysis module (62). The Cα z-position of W76 is taken for the zero reference. Mean z-positions for the Cα residues lining the pore are given on the right of the water orientation graphs.

Because cholesterol-depleted membranes lead to an open conformation of Orai1 (63), cholesterol was included in the simulated system. Cholesterol parameters (64, 65) for the all-atom Optimized-Potentials-for-Liquid-Simulations (OPLS-AA) force field were used. AutoDock VINA (66, 67) implemented in YASARA was used to place the cholesterol molecules in close proximity to the Orai1 channel, using docking in which the protein was kept rigid and the ligand was flexible was performed to identify potential cholesterol binding sites across the whole hexameric structure. Docked poses having a root mean square (RMS) deviation for the heavy atoms < 5 Å were clustered together. The three highest ranked poses were selected from the most populated clusters and the resulting complex was embedded into a pre-equilibrated palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) bilayer. Throughout all molecular dynamics simulations the WT-Orai1/cholesterol/POPC system maintains its initial conformation (as measured by RMS fluctuations and secondary structure over time) and the pore profile stays similar to the one observed in the initial structure and the Drosophila crystal structure, making it a suitable system for introducing point mutations that would alter the pore profile.

Steered molecular dynamics, as implemented in GROMACS pull code, was utilized to pull calcium ion through the Orai1 wt and H134A mutant structures. Calcium ion in the CAR (calcium accumulating region) was selected as starting point for pulling along Z axis through the central pore toward intracellular side. Pulling method umbrella was used where pulling group (calcium ion) is harmonically attached to the reference particle. By applying force the reference particle is moved with constant pulling rate. The pulling group (calcium) harmonically attached to the reference particle is moved according to the equation F = k (vt - x), where F is force, k- spring constant, v - pulling rate (velocity), t - time, x - displacement of the pulled group. Pulling rate was -0.00055 nm/ps (minus is required to pull in negative Z direction) and spring constant was 1000 kJ mol-1 nm-2.

The HOLE program was used to calculate pore dimensions. The starting point, approximately at the centre of the channel, and a vector are required for the initiation of the search. The vector was defined along Z axis of the channel. After the initial point and vector are defined, a sphere is put at the initial point without overlapping with protein atoms. Monte Carlo simulated annealing procedure is applied to maximize the sphere radius in all three dimensions until the largest radius is reached at the current position. Then a new point is assigned at a distance of 0.2 Å in the z-direction. This procedure is repeated to find the maximum radius along the whole pore. VMD tool was used to visualize the final output of HOLE run.

The survival probability gives the probability for a group of particles to remain in a certain region. This probability is computed by using the following formula

where T corresponds to the simulation time length, τ is the time lag and N(t) is the number of particles at a time t. This function is evaluated for different regions at constant interval along the z axis, axis normal to the membrane. Only the water molecules present in the cylinder defining the pore are taken into account. A steep decrease of P(τ) would indicate a fast exchange rate of water molecules in a given area, or molecules with a short permanence time. Conversely, a slow decay of the survival probability would describe an area where molecules have slower dynamics.

Supplementary Material

Steered molecular dynamics simulation of wild-type Orai1 shows a Ca2+ ion in purple that is pulled through the pore. Other Ca2+ ions are depicted in yellow, Cl- ions in green and two TM1 helices are highlighted in red including pore lining side-chains.

One-sentence summary.

Characterization of disease-associated Orai1 mutants reveals the multistep gating mechanism for the CRAC channel.

Acknowledgments

V.Z. wishes to thank Saurabh Pandey for the technical assistance and help with pore profile analysis. I.B. and S.C. thank Prof. Markus Hoth for his continuous support. S. Crockett is thanked for proofreading and copyediting the manuscript. We thank A. Rao (Harvard Medical School) for providing human Orai1, T. Meyer (Standford University) for providing N-terminally ECFP- and EYFP-tagged STIM1, Ralph Kehlenbach (Scripps Research Institute) for providing GFP-NFAT, and Y. Usachev (University of Iowa) for providing pNFAT-TA-mRFP (NFAT-driven RFP expression).

Funding

This work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) through several projects (P28872 to I.F., P26067 to Ra.S. and C.R., P28701 to Ra.S., P27263 to C.R., P28498 to M.M., and BMWF HRSM project to C.R.), by the Czech Science Foundation through a grant to R.E. (13-21053S) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) project and research grant to I.B. (SFB1027 project C4 and BO3643/3-1 research grant, respectively). Ra.S., C.R., I.B. and R.H.E. were funded in part through a COST action (BM1406) and by the program Inter-COST (project LTC17069 to R.E.). B.S. received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): W 1226, DK Metabolic and Cardiovascular Disease at the Medical University of Graz. Access to modelling facilities was supported by the Czech research infrastructure for systems biology C4SYS (project no. LM2015055).

Footnotes

Author contributions

Ra.S., I.F., R.H.E., C.R., I.B., V.Z. conceived the ideas, directed the work and designed the study. I.F. designed and generated all the plasmid constructs. Ra.S. and I.B. performed the initial analysis of tumour genomes. Ra.S. and M.L. performed the patch-clamp experiments. M.L., Ro.S., M.M. and S.C. performed the fluorescence experiments. V.Z., D.B., L.T. and R.H.E. performed the computational modelling, molecular dynamics simulations and Ca2+-pulling experiments. I.F., B.S., V.L., A.S. and T.P. prepared the membranes and crosslinking experiments. I.F., M.L., Ro.S., V.Z., B.S., S.C., M.M., I.V., R.H.E., I.B., D.B. and Ra.S. analysed data, with input from the other authors. Ra.S. wrote the manuscript with the input of I.F., M.L., Ro.S., V.Z., B.S., D.B., K.G., I.B., R.H.E. and C.R. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun A, Varga-Szabo D, Kleinschnitz C, Pleines I, Bender M, Austinat M, Bosl M, Stoll G, Nieswandt B. Orai1 (CRACM1) is the platelet SOC channel and essential for pathological thrombus formation. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streb H, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luik RM, Wang B, Prakriya M, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 2008;454:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nature07065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muik M, Fahrner M, Schindl R, Stathopulos P, Frischauf I, Derler I, Plenk P, Lackner B, Groschner K, Ikura M, Romanin C. STIM1 couples to ORAI1 via an intramolecular transition into an extended conformation. EMBO J. 2011;30:1678–1689. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136:876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF, Muallem S. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:337–343. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stathopulos PB, Schindl R, Fahrner M, Zheng L, Gasmi-Seabrook GM, Muik M, Romanin C, Ikura M. STIM1/Orai1 coiled-coil interplay in the regulation of store-operated calcium entry. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3963. 2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kar P, Parekh AB. Distinct spatial Ca2+ signatures selectively activate different NFAT transcription factor isoforms. Mol Cell. 2015;58:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frischauf I, Zayats V, Deix M, Hochreiter A, Jardin I, Muik M, Lackner B, Svobodova B, Pammer T, Litvinukova M, Sridhar AA, et al. A calcium-accumulating region, CAR, in the channel Orai1 enhances Ca(2+) permeation and SOCE-induced gene transcription. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra131. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmeier W, Weidinger C, Zee I, Feske S. Emerging roles of store-operated Ca(2)(+) entry through STIM and ORAI proteins in immunity, hemostasis and cancer. Channels (Austin) 2013;7:379–391. doi: 10.4161/chan.24302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacruz RS, Feske S. Diseases caused by mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1356:45–79. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubois C, Vanden Abeele F, Lehen'kyi V, Gkika D, Guarmit B, Lepage G, Slomianny C, Borowiec AS, Bidaux G, Benahmed M, Shuba Y, et al. Remodeling of Channel-Forming ORAI Proteins Determines an Oncogenic Switch in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YF, Chiu WT, Chen YT, Lin PY, Huang HJ, Chou CY, Chang HC, Tang MJ, Shen MR. Calcium store sensor stromal-interaction molecule 1-dependent signaling plays an important role in cervical cancer growth, migration, and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15225–15230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103315108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang S, Zhang JJ, Huang XY. Orai1 and STIM1 are critical for breast tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanisz H, Saul S, Muller CSL, Kappl R, Niemeyer BA, Vogt T, Hoth M, Roesch A, Bogeski I. Inverse regulation of melanoma growth and migration by Orai1/STIM2-dependent calcium entry. Pigm Cell Melanoma R. 2014;27:442–453. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanisz H, Vultur A, Herlyn M, Roesch A, Bogeski I. The role of Orai-STIM calcium channels in melanocytes and melanoma. J Physiol. 2016;594:2825–2835. doi: 10.1113/JP271141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoth M. CRAC channels, calcium, and cancer in light of the driver and passenger concept. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:1408–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou X, Pedi L, Diver MM, Long SB. Crystal structure of the calcium release-activated calcium channel Orai. Science. 2012;338:1308–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1228757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNally BA, Somasundaram A, Yamashita M, Prakriya M. Gated regulation of CRAC channel ion selectivity by STIM1. Nature. 2012;482:241–245. doi: 10.1038/nature10752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita M, Yeung P, Ing C, McNally B, Pomès R, Prakriya M. STIM1 activates CRAC channels through rotation of the pore helix to open a hydrophobic gate. Nature Communications. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derler I, Fahrner M, Carugo O, Muik M, Bergsmann J, Schindl R, Frischauf I, Eshaghi S, Romanin C. Increased hydrophobicity at the N terminus/membrane interface impairs gating of the severe combined immunodeficiency-related ORAI1 mutant. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15903–15915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Hu J, Amcheslavsky A, Zheng H, Cahalan MD. Mutations in Orai1 transmembrane segment 1 cause STIM1-independent activation of Orai1 channels at glycine 98 and channel closure at arginine 91. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17838–17843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114821108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jardin I, Rosado JA. STIM and calcium channel complexes in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:1418–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao JJ, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun YC, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Science Signaling. 2013;6 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northrop JP, Ho SN, Chen L, Thomas DJ, Timmerman LA, Nolan GP, Admon A, Crabtree GR. NF-AT components define a family of transcription factors targeted in T-cell activation. Nature. 1994;369:497–502. doi: 10.1038/369497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCaffrey PG, Luo C, Kerppola TK, Jain J, Badalian TM, Ho AM, Burgeon E, Lane WS, Lambert JN, Curran T, et al. Isolation of the cyclosporin-sensitive T cell transcription factor NFATp. Science. 1993;262:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.8235597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG. Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: portrait of a low-affinity signalling interaction. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endo Y, Noguchi S, Hara Y, Hayashi YK, Motomura K, Miyatake S, Murakami N, Tanaka S, Yamashita S, Kizu R, Bamba M, et al. Dominant mutations in ORAI1 cause tubular aggregate myopathy with hypocalcemia via constitutive activation of store-operated Ca(2)(+) channels. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:637–648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nature. Vol. 487. TCGA; 2012. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer; pp. 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nature. Vol. 513. TCGA; 2014. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma; pp. 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Getz G. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;500:67. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nature. Vol. 517. TCGA; 2015. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas; pp. 576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muik M, Fahrner M, Derler I, Schindl R, Bergsmann J, Frischauf I, Groschner K, Romanin C. A Cytosolic Homomerization and a Modulatory Domain within STIM1 C Terminus Determine Coupling to ORAI1 Channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8421–8426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800229200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, Settembre C, et al. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:288–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Garcia Arencibia M, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Erdin SU, Huynh T, Medina D, Colella P, Sardiello M, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perera RM, Stoykova S, Nicolay BN, Ross KN, Fitamant J, Boukhali M, Lengrand J, Deshpande V, Selig MK, Ferrone CR, Settleman J, et al. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature. 2015;524:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature14587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, Getz G, Berger AJ, Ramaswamy S, Beroukhim R, Milner DA, Granter SR, Du J, Lee C, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]