Abstract

Background

Acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is a common disease across the world and is associated with significant socioeconomic costs. Although contemporary guidelines support the role of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ELC), there is significant variation among units adopting it as standard practice. There are many resource implications of providing a service whereby cholecystectomies for acute cholecystitis can be performed safely.

Methods

Studies that incorporated an economic analysis comparing early with delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy (DLC) for acute cholecystitis were identified by means of a systematic review. A meta‐analysis was performed on those cost evaluations. The quality of economic valuations contained therein was evaluated using the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) analysis score.

Results

Six studies containing cost analyses were included in the meta‐analysis with 1128 patients. The median healthcare cost of ELC versus DLC was €4400 and €6004 respectively. Five studies had adequate data for pooled analysis. The standardized mean difference between ELC and DLC was −2·18 (95 per cent c.i. −3·86 to −0·51; P = 0·011; I 2 = 98·7 per cent) in favour of ELC. The median QHES score for the included studies was 52·17 (range 41–72), indicating overall poor‐to‐fair quality.

Conclusion

Economic evaluations within clinical trials favour ELC for ACC. The limited number and poor quality of economic evaluations are noteworthy.

Introduction

Acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is a common and significant disease around the world and may often have a high socioeconomic impact1. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the best treatment for ACC in the majority of patients2, 3, and contemporary evidence, including randomized studies, population studies and meta‐analyses, has clearly demonstrated the clinical benefit of early cholecystectomy in which surgery is undertaken during the index admission4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. These benefits include reduced morbidity, shorter duration of hospital stay and higher patient satisfaction. Importantly, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ELC) has not been associated with an increase in bile duct injury, bile leak or conversion rates4. In fact, there may be fewer complications12. Time allowed to overcome the initial inflammatory response (usually 6–8 weeks) may itself be associated with increased morbidity in terms of repeat attacks and further admissions to hospital. This may impact patient quality of life with respect to pain, anxiety, and lost days of work and other forms of social functioning. The acute readmission rate varies from 19 to 36 per cent during this waiting period, compared with a readmission rate of only 4 per cent following cholecystectomy13.

The definition and recommended management of ACC are available in evidence‐based guidelines14, 15. These guidelines include significant support for the role of ELC in managing ACC. In spite of this, there is still wide variation in practice within and between countries, and surgery is often delayed16, 17, 18. A paucity of emergency general surgical resources, including dedicated operating theatre time, is probably the most significant barrier19. Additional challenges may include perceived surgeon skill mix and competence to perform a cholecystectomy in the setting of ACC, as well as competition with elective practice demands18.

Economic evaluation has become an increasingly important decision‐making tool to determine effectiveness and address resource allocation issues. Trial‐based cost‐effectiveness studies are appealing because of their high internal validity and timeliness. However, the economic evaluation within clinical trials in isolation is often not a tool that considers all decision‐making factors, including feasibility, budget impact, patient/provider perception and equity20. By combining the results of similar studies, meta‐analysis may be a useful tool to consider economic value along with clinical efficacy21. The aim of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to assess and evaluate the current evidence base for the cost‐effectiveness of early cholecystectomy in the setting of acute cholecystitis.

Methods

A systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines22. Institutional review board approval was not required.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search using a combination of free‐text terms and controlled vocabulary, when applicable, was undertaken in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library. The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal and ClinicalTrials.gov were also searched to identify further trials. Details of the search strategy are provided in Table S1 (supporting information). The related articles function in PubMed was used to broaden the search, and all abstracts, studies and citations identified were reviewed. References of the identified trials were searched to find additional trials for inclusion. No restrictions were made based on language. The year of publication was limited from January 2000 to June 2017.

Briefly, the following search headings were used: ‘early cholecystectomy, delayed cholecystectomy’, and the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms ‘cholecystectomy’, ‘cholecystitis’, and ‘healthcare costs’. All titles were initially screened and relevant abstracts reviewed with consensus agreements between the reviewers. Each of the appropriate publication reference sections and Google Scholar were also screened to look for publications. The last date of search was 26 September 2017.

Inclusion criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria: report on patients having laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis; compare early versus delayed/interval cholecystectomy; report economical comparisons for each cohort and have a clear research methodology. Studies relying on economic modelling as their only means of cost‐effectiveness analysis (not including actual patient data) were excluded from the meta‐analysis.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed the available literature according to the above predefined strategy and criteria. Each reviewer extracted the following data variables: title and publication details (first author, journal, year and country), study population characteristics (number in study, number treated by each approach, sex and age, severity of acute cholecystitis or biliary pancreatitis). Economic differences and outcomes for each approach (early versus delayed cholecystectomy) were recorded. If available, postoperative complications, reoperation/reintervention rates, duration of surgery, operative blood loss, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain and time to return to work were noted.

All data were recorded independently by both reviewers in separate databases, and compared only at the end of the reviewing process to limit selection bias. The database was also reviewed by a third person. Duplicates were removed and disparities clarified.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcome used in the meta‐analysis was cost comparison differences between early and delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. The secondary outcome was total duration of hospital stay. This represented all lengths of stay including the index and any subsequent admissions.

Quality assessment

The quality of the economic evaluation of included studies was evaluated using the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) tool23. This has been validated and shown to be both simple and reliable. This tool includes 16 questions answered as ‘yes’ or ‘no’, and each question has an assigned value ranging from 1 to 9. It assesses several economic study criteria including: whether the stated objectives, analytical perspective and time horizon, outcome measures, data abstraction methods and analysis (incremental analysis and handling of uncertainty) are clearly stated; the appropriateness of selected economic models and associated cost measurements; and whether a clearly defined process to reduce the risk of bias was included. Questions answered ‘yes’ receive the full point value and those answered ‘no’ receive no points. The sum of these points generates a summary score on a scale of 0–100, with 0 indicating extremely poor quality and 100 indicating high quality.

Studies of clinical effectiveness were also assessed using criteria based on the National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Report Number 424. In the assessment of cost‐effectiveness, in order to accommodate the multiple forms of economic evaluation that were reported, relevant studies were also evaluated and assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement25.

Risk of bias was assessed based on the Cochrane Collaboration risk‐of‐bias domains: allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and vested interest bias. For each of these domains, studies were categorized as at low, uncertain or high risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata® Data Analysis and Statistical Software version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Binary outcome data were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95 per cent c.i., and estimated using the Mantel–Haenszel method. For continuous data, standardized mean differences (MDs) and 95 per cent c.i. were estimated using random‐effects models. MD was calculated as: (new treatment improvement − standard treatment improvement)/pooled standard deviation26. In this analysis, the new treatment, ELC, was compared with delayed/interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy (DLC) as the standard treatment. A MD value of zero denotes equivalent effects between ELC and DLC. For continuous data such as healthcare cost and length of stay, MD below zero indicates that ELC is better than DLC, and vice versa. Comparative parameters were recorded either as mean(s.d.) or median (range) values. For continuous data, mean(s.d.) values were estimated from the median (range) and size of the sample27. Heterogeneity was assessed by I 2 statistics, with a value above 50 per cent indicating considerable heterogeneity. Statistical significance was attributed at P < 0·050.

Healthcare costs are expressed in euros (€). If a paper did not report in euros, conversion was performed via XE Currency Data28 (currency conversion rates per market value on 26 September 2017).

Results

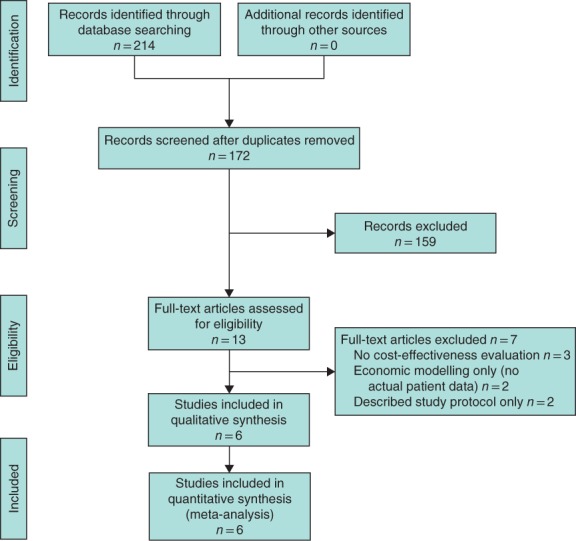

A total of 214 articles were initially identified using the search strategy (Fig. 1). On full‐text screening, four RCTs9, 10, 11, 29 and two observational studies30, 31 met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). All studies were published between 2009 and 2016.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing the selection of articles for review

Table 1.

Study characteristics, number of participants and healthcare costs

| Reference | Country | Payer | Time period | Single or multiple centre | No. of cholecystectomies | QHES score‡ | Costs (€)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELC | DLC | ELC | DLC | ||||||

| MacAfee et al.10 (2009) | UK | State | 2004–2007 | Single | 36 | 36 | 72 | 6070 (6741(2788))† | 6004 (6993(3699))† |

| Gutt et al.9 (2013) | Germany | State | 2010–2011 | Multiple | 304 | 314 | 56 | 2919 (2812–3026) | 4262 (3021–4494) |

| Ozkardeş et al.11 (2014) | Turkey | State | 2011–2012 | Single | 30 | 30 | 43 | n.s. (859(259))† | n.s. (1274(178))† |

| Roulin et al.29 (2016) | Switzerland | State | 2009–2014 | Single | 42 | 44 | 53 | 9349 (7865–11 142) | 12 361 (10 753–14 253) |

| Tan et al.30 (2015) | Singapore | State | 2011–2013 | Single | 134 | 67 | 41 | 4400 (3600–5600) | 5500 (4000–7500) |

| Minutolo et al.31 (2014) | Italy | State | 2011–2013 | Multiple | 32 | 59 | 48 | 4171 | 6041 |

Values are median (range) unless indicated otherwise;

values in parentheses are mean(s.d.).

Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) score for each study employing an economic evaluation: score above 75 implies an article of high quality; score 51–75 implies an article of fair quality; score 25–50 implies an article of poor quality; score below 25 implies an article of extremely poor quality. ELC, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy; DLC, delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy. n.s., not stated.

On review of the extracted data, there was 100 per cent agreement between the two reviewers. Study characteristics are outlined in Table S2 (supporting information).

Demographics

Analysis involved 1128 patients, of whom 578 (51·2 per cent) had ELC and 550 (48·8 per cent) had DLC. All studies involved patients operated on between 2004 and 2014 (Table 1). Across the six studies, female sex was more common, accounting for 56·6 per cent of all cholecystectomies. There was no difference in terms of age and BMI between the groups, although only two studies9, 29 reported median BMI. Median age across the six studies was 55 and 56·5 years for ELC and DLC respectively.

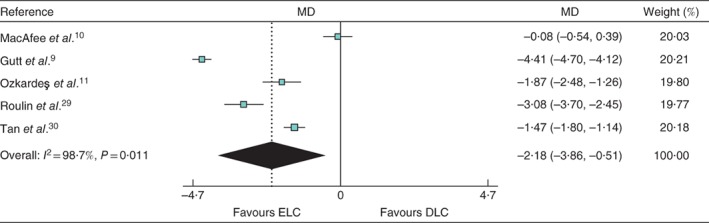

The median healthcare cost for ELC and DLC was €4400 and €6004 respectively. Five studies had adequate data for pooled analysis. The MD between ELC and DLC was −2·18 (95 per cent c.i. −3·86 to −0·51; P = 0·011; I 2 = 98·7 per cent) in favour of ELC (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing healthcare cost between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Mean differences (MDs) are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Weights are from random‐effects analysis. ELC, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy; DLC, delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy

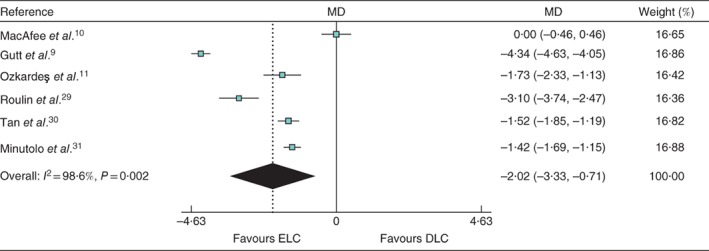

All six studies reported the conversion rate to open cholecystectomy: 11·6 per cent (67 of 578) for ELC and 11·6 per cent (64 of 550) for DLC. Postoperative complications occurred in 11·8 per cent (68 of 578) of patients undergoing ELC and 12·0 per cent (66 of 550) of those having DLC. The rate of bile leak was 1·2 per cent (5 of 412) and 0·5 per cent (2 of 424) in ELC and DLC groups respectively. Median length of hospital stay was 5·4 and 7 days respectively. All six studies had adequate data for pooled analysis to assess length of hospital stay; the MD was −2·02 (95 per cent c.i. −3·33 to −0·71; P = 0·002; I 2 = 98·6 per cent) in favour of ELC (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing length of hospital stay between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Mean differences (MDs) are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Weights are from random‐effects analysis. ELC, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy; DLC, delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Quality assessment

The median QHES score for the included studies was 52·17 (range 41–72). Questions from the QHES tool that were not addressed consistently related to lack of analyses performed between alternatives for resources and costs, the transparency of reporting the economic model used, and the lack of explicit discussion on the direction and magnitude of potential biases. With the exception of one study10, the others included in the meta‐analysis were, in general, non‐compliant with the CHEERS checklist, primarily because they were not designed to report economic evaluations of this particular health intervention.

Discussion

This meta‐analysis of economic evaluations within clinical trials favoured ELC in ACC. The number of high‐quality studies that incorporated a cost analysis into their design in comparing the role of ELC and DLC for acute cholecystitis was small, and the quality of these studies as indicated by QHES scores was poor. Nevertheless, meta‐analysis of clinical studies can provide a sound basis for economic evaluation by giving a more precise and more representative estimate of treatment effect than a single clinical trial32.

Cost savings with ELC were accounted for mainly by the reduction in further admissions. All but one10 of the RCTs are notable for giving only total costs of the hospital visit and not accounting for the economic effects of hospitalization such as loss of earned income, loss to society, cost of physician visits outside of hospital related to these episodes, or medication costs. All of these are expected to be higher for the DLC group, and so the cost savings may be underestimated in these reports.

Although there are several guidelines available to surgeons and physicians on the clinical benefits of ELC, only one14 has incorporated health economic evidence, based solely on cost–utility analysis. Its limitations were acknowledged in Appendix J of those same guidelines14. These included a limited time horizon, assumptions made in the data sources used, and a delay between ELC and DLC longer than that found in most clinical papers (up to 3 times longer). The recurrence of symptoms (and associated costs) in the DLC group was also not considered. Crucially, the model32 did not account for patient co‐morbidities, often the unavoidable cause of DLC. Current perceptions of ELC together with relatively low rates of ELC33 indicate that surgical teams may require additional training before adopting ELC34. The costs of additional training and potentially higher conversion rates during this transition require consideration as contributors to a one‐off ‘transition cost’. Similarly, although ELC is often regarded as an ‘upper gastrointestinal surgery’ procedure, units with less specialized surgeons are also likely to be required to provide an ELC service. This aspect of service provision will also require training for surgical teams and logistical arrangements to accommodate these procedures in such units.

The reality of practice has been evaluated by the CholeS Study Group in a model‐based cost–utility analysis from the perspective of the UK National Health Service on 4653 patients who had surgery for acute gallbladder disease across 167 hospitals in the UK and Ireland between 1 March and 1 May 2014. They demonstrated low uptake by surgeons in implementing the practice of ELC, but established its cost‐effectiveness across all willingness‐to‐pay values up to £100 000 (approximately €112 000, exchange rate 30 October 2018), albeit at much smaller numerical cost values and quality‐adjusted life‐years (QALYs) than previously anticipated16.

The limited number of studies employing cost‐effectiveness analysis, despite clear benefit, reflects the overall poor uptake of economic evidence beyond the area of Health Technology Assessment35. Because of poor uptake, it is important not only to examine what economic evidence is available but also to see how its translation can be improved to increase efficiency, akin to the Research Agenda for Health Economic Evaluation (RAHEE) project being undertaken by the WHO, the European Commission, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and a range of academic partners, that will look at contextual factors important for the translation of such knowledge in practice36. Improving the quality and uniformity of trial‐based cost‐effectiveness studies will increase their value to those who consider evidence of economic value along with clinical efficacy when making resource allocation decisions20. Although cost‐effectiveness analyses have improved due to the development of methods of synthesizing evidence, there is no consensus on the best methods for carrying out appropriate meta‐analyses.

Resource implications of providing a service whereby cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis can be performed safely are many. Evaluation should be based on well conducted clinical trials in which interventions are provided in a routine service setting, and in which benefits are assessed among other things on the basis of the patient's perceived quality of life37. The integration of clinical trials into clinical practice, however, is not straightforward, and economic assessment often needs data beyond those collected in a clinical trial, however pragmatic the trial design38. Although it is unlikely that economists will ever dispense with modelling, improving the quality and uniformity of these studies will increase their value to decision‐makers who consider evidence of economic value along with clinical efficacy when making resource allocation decisions.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Detailed search strategy

Table S2. Study demographics, surgical and postoperative outcomes

Funding information No funding

References

- 1. Campanile FC, Pisano M, Coccolini F, Catena F, Agresta F, Ansaloni L. Acute cholecystitis: WSES position statement. World J Emerg Surg 2014; 9: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomes CA, Junior CS, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Kelly MD, Gomes CC et al Acute calculous cholecystitis: review of current best practices. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9: 118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cao AM, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Early cholecystectomy is superior to delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta‐analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19: 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gurusamy K, Samraj K, Gluud C, Wilson E, Davidson BR. Meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (6)CD005440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menahem B, Mulliri A, Fohlen A, Guittet L, Alves A, Lubrano J. Delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy increases the total hospital stay compared to an early laparoscopic cholecystectomy after acute cholecystitis: an updated meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17: 857–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu XD, Tian X, Liu MM, Wu L, Zhao S, Zhao L. Meta‐analysis comparing early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1302–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhou MW, Gu XD, Xiang JB, Chen ZY. Comparison of clinical safety and outcomes of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta‐analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014: 274516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutt CN, Encke J, Köninger J, Harnoss JC, Weigand K, Kipfmüller K et al Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicenter randomized trial (ACDC study, NCT00447304). Ann Surg 2013; 258: 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Macafee DA, Humes DJ, Bouliotis G, Beckingham IJ, Whynes DK, Lobo DN. Prospective randomized trial using cost‐utility analysis of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute gallbladder disease. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ozkardeş AB, Tokaç M, Dumlu EG, Bozkurt B, Ciftçi AB, Yetişir F et al Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective, randomized study. Int Surg 2014; 99: 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Mestral C, Rotstein OD, Laupacis A, Hoch JS, Zagorski B, Alali AS et al Comparative operative outcomes of early and delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a population‐based propensity score analysis. Ann Surg 2014; 259: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Mestral C, Rotstein OD, Laupacis A, Hoch JS, Zagorski B, Nathens AB. A population‐based analysis of the clinical course of 10 304 patients with acute cholecystitis, discharged without cholecystectomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 74: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warttig S, Ward S, Rogers G; Guideline Development Group . Diagnosis and management of gallstone disease: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2014; 349: g6241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yamashita Y, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ et al; Tokyo Guideline Revision Committee. TG13 surgical management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013; 20: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CholeS Study Group, West Midlands Research Collaborative . Population‐based cohort study of variation in the use of emergency cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 1716–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamashita Y, Takada T, Hirata K. A survey of the timing and approach to the surgical management of patients with acute cholecystitis in Japanese hospitals. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006; 13: 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Mestral C, Laupacis A, Rotstein OD, Hoch JS, Haas B, Gomez D et al Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a population‐based retrospective cohort study of variation in practice. CMAJ Open 2013; 1: E62–E67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lankisch PG, Weber‐Dany B, Lerch MM. Clinical perspectives in pancreatology: compliance with acute pancreatitis guidelines in Germany. Pancreatology 2005; 5: 591–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, Reed SD, Augustovski F, Jonsson B et al Cost‐effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II – an ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health 2015; 18: 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D et al; ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines–CHEERS Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) – explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013; 16: 231–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010; 8: 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ofman JJ, Sullivan SD, Neumann PJ, Chiou CF, Henning JM, Wade SW et al Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm 2003; 9: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowdon AJ, Kleijnen J. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD's Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews (2nd edn). CRD Report No. 4. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D et al Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Eur J Health Econ 2013; 14: 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. P T 2008; 33: 700–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. XE . XE Live Exchange Rates https://www.xe.com [accessed 1 November 2018].

- 29. Roulin D, Saadi A, Di Mare L, Demartines N, Halkic N. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis, are the 72 hours still the rule?: A randomized trial. Ann Surg 2016; 264: 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan CH, Pang TC, Woon WW, Low JK, Junnarkar SP. Analysis of actual healthcare costs of early versus interval cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015; 22: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minutolo V, Licciardello A, Arena M, Nicosia A, Di Stefano B, Calì G et al Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the treatment of acute cholecystitis: comparison of outcomes and costs between early and delayed cholecystectomy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014; 18(Suppl): 40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pang F, Drummond M, Song F. The Use of Meta‐analysis in Economic Evaluation, Working Papers No. 173chedp. Centre for Health Economics, University of York: York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gomi H, Yoshida M et al; Tokyo Guidelines Revision Committee . TG13: updated Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013; 20: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Teoh AY, Chong CN, Wong J, Lee KF, Chiu PW, Ng SS et al Routine early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis after conclusion of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg 2007; 94: 1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tordrup D, Bertollini R. Consolidated research agenda needed for health economic evaluation in Europe. BMJ 2014; 349: g5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chao TE, Sharma K, Mandigo M, Hagander L, Resch SC, Weiser TG et al Cost‐effectiveness of surgery and its policy implications for global health: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e334–e345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brazier JE, Johnson AG. Economics of surgery. Lancet 2001; 358: 1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Detailed search strategy

Table S2. Study demographics, surgical and postoperative outcomes