Abstract

Background

Society of Surgical Oncology and American Society for Radiation Oncology guidelines define clear margins in breast‐conserving therapy (BCT) as ‘no ink on tumour’, in contrast to the attainment of margins of at least 1 mm widely practised in the UK. The primary aim of this study was to explore clinical, surgical and tumour‐related factors associated with local recurrence after BCT, with a secondary aim of assessing the impact of margin re‐excision on the risk of local recurrence.

Methods

Patient demographics, surgical details, tumour characteristics and local recurrence were recorded for consecutive women with BCT undergoing surgery between January 1997 and January 2007. Margins were defined as clear (greater than 1 mm), close (less than 1 mm but no ink on tumour), reaches (ink on tumour) and clear after re‐excision.

Results

A total of 1045 women of median age 54 (range 18–86) years were studied. Median follow‐up was 89 (range 4–196) months. Local recurrence occurred in 52 patients (5·0 per cent). Ink on tumour was associated with local recurrence (hazard ratio (HR) 4·86, 95 per cent c.i. 1·49 to 15·79; P = 0·009). Risk of local recurrence was the same for close and clear margins (HR 1·03, 0·40 to 2·62; P = 0·954). In women with involved margins, re‐excision was still associated with an increased local recurrence risk (HR 2·50, 1·32 to 4·72; P = 0·005). Oestrogen receptor negativity increased risk (HR 2·28, 1·28 to 4·06; P = 0·005).

Conclusion

Adequately excised margins, even when under 1 mm, provide equivalent outcomes to wider margins in BCT. Achieving complete excision at primary surgery achieves the lowest rates of local recurrence.

Introduction

Breast‐conserving therapy (BCT) for invasive breast cancer combines wide local excision (WLE) with adjuvant radiotherapy and provides equivalent outcomes to mastectomy for early‐stage breast cancer1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Preservation of the breast has a number of advantages over mastectomy, including psychological benefits7, shorter operating times, less postoperative pain, and fewer clinically significant complications such as haematoma and seroma8 9. A shorter recovery period allows earlier return to work and reduces the economic impact of the cancer treatment. The cosmetic outcome following WLE is generally superior to that achieved by mastectomy and reconstruction10.

Local recurrence represents a significant event for the patient. Data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group11 suggest that avoidance of local recurrence reduces the rate of breast cancer death by 25 per cent. Local control in BCT can be attributed to two main factors: clear resection margins and adjuvant radiotherapy to the remaining breast, with the latter shown to reduce local recurrence by 19 per cent12. In 2014, the Society of Surgical Oncology and American Society for Radiation Oncology (SSO–ASTRO) published their updated consensus guideline13 on margins, for breast‐conserving surgery with whole breast irradiation for invasive disease, in response to a meta‐analysis14 of data on surgical margins and local recurrence following BCT in 28 162 women. This study14 found a median local recurrence rate of 5·3 per cent and showed that, although the risk of local recurrence was doubled in patients with positive margins, as long as there was ‘no ink on tumour’ wider margins did not reduce the risk. The SSO–ASTRO consensus guideline13 on margins for BCT now recommends the use of no ink on tumour as the standard for an adequate margin in invasive breast cancer.

In the UK and Ireland, the 2016 National Margins Audit15 found large variation in margin policy and re‐excision rates across breast units. Although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence defines a margin clearance of 2 mm for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)16, the Association of Breast Surgery recommends minimum margins of 1 mm for both DCIS and invasive disease17. Lack of margin consensus and resultant variation in practice across the UK and Ireland raises a number of concerns. Excising too much tissue may result in poor cosmesis, which can be exacerbated by adjuvant radiotherapy. Some women may be subjected to unnecessary additional surgery. Margin re‐excision may further worsen cosmesis as well as contribute to the emotional burden of cancer treatment and increase the risk of postoperative complications. Additional procedures for margin clearance and to correct poor cosmesis, such as lipofilling, increase healthcare costs18.

In light of the recently published SSO–ASTRO guidelines13, the primary aim of this study was to explore clinical, surgical and tumour‐related factors associated with local recurrence risk. The secondary aim was to assess the role of margin re‐excision in reducing the risk of local recurrence.

Methods

This project was approved as a service evaluation by the Royal Marsden NHS Trust, protocol BR068. A database of patients with invasive breast cancer treated by BCT between 8 January 1997 and 3 January 2007 was generated with the collaboration of clinicians in the Breast Unit and the Department of Information Technology and Statistics at the Royal Marsden NHS Trust. Data collection comprised patient demographics, surgical details, tumour characteristics, adjuvant therapy and clinical outcomes, including local recurrence, distant metastasis, breast cancer‐related and all‐cause mortality. Margin status was defined as involved, clear (1 mm or more), close (less than 1 mm but no ink on tumour), reaches (ink on tumour) and clear after re‐excision. During the study interval, the institutional policy was to accept margins of 1 mm or greater. However, individual case discussion by the multidisciplinary team resulted in some cases where margins were close (under 1 mm but not reaching ink) being accepted.

Tumour characteristics recorded in the original histology reports were retrieved from the hospital's electronic patient records. Local recurrences were identified by examining all histology reports indicating further surgery and excision of recurrent tumour, and by reviewing all follow‐up clinic letters. A true local recurrence was determined by the presence of a subsequent carcinoma of similar biology (grade and receptor status) within the same quadrant of the breast as the first presenting carcinoma. Any new carcinomas within the same breast that did not fulfil the above criteria were considered new primary lesions.

Statistical analysis

The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to compare the hazards of patients in each group, using univariable models. A two‐sided 5 per cent α level was used to assess statistically significant difference in the models. A multivariable model was used to identify the independent predictors of local recurrence and disease‐free survival. Variables found to be significant at P ≤ 0·200 in the univariable model were included in a forward stepwise method, which was used to fit the multivariable model. SPSS® version 16.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the time to local recurrence and disease‐free survival from the date of wide local excision. Diagnosis of local recurrence in the ipsilateral breast was the defining event for time to local recurrence; axillary recurrence, supraclavicular fossa (SCF) recurrence, metastasis and death without local recurrence were censored as independent events. For disease‐free survival, defining events included local recurrence, axillary recurrence, SCF recurrence, metastasis and death from any cause. Patients who were alive and disease‐free or lost to follow‐up were censored at the date of their last follow‐up or upon discharge.

Results

Data were collected on 1440 women who had BCT during the study period. Some 253 women were excluded from further analysis because their initial surgery had been performed at a different hospital and clinical data from the referring hospital could not be accessed. A further 66 women were excluded because they did not receive radiotherapy as part of BCT. Seventy‐six patients had bilateral cancers and only one record (first surgery, or right breast if on the same date) was retained for the purposes of analysis. The median age of the 1045 remaining women was 54 (range 18–86) years. Margins were clear in 798 patients, and 110 had close margins. There was ink on tumour in 137 but, of this group, 122 women had subsequent re‐excision of margins, leaving 15 patients with ink on tumour. Patient and tumour characteristics, and surgical factors (type of axillary procedure and margin status) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics

| No. of patients (n = 1045) | |

|---|---|

| Axillary procedures | 980 (93·8) |

| Sentinel node biopsies | 390 |

| Axillary sampling | 29 |

| Axillary dissection | 561 |

| Tumour type | |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 892 (85·4) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 104 (10·0) |

| Mixed invasive ductal and lobular carcinoma | 32 (3·1) |

| Other* | 17 (1·6) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Yes | 333 (31·9) |

| No | 712 (68·1) |

| ER status | |

| Positive | 881 (84·3) |

| Negative | 164 (15·7) |

| Excision margin | |

| Clear (≥ 1 mm) | 798 (76·4) |

| Close (< 1 mm) | 110 (10·5) |

| Reaches | 15 (1·4) |

| Re‐excision | 122 (11·7) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Includes invasive mucinous, micropapillary, medullary carcinoma. ER, oestrogen receptor.

Median follow‐up for this study was 89 (range 4–196) months. Ninety‐seven (9·3 per cent) of the women died from their breast cancer (Table 2). Some 81·6 per cent remained disease‐free, 5·0 per cent relapsed first with local recurrence, and 11·2 per cent of patients developed metastatic disease. In women who relapsed, the overall mortality rate was 50·5 per cent. This varied with type of relapse; the mortality rate was 60 per cent in women who developed local recurrence first. There was a significantly greater risk of death from all causes in women with local recurrence compared with that in women with no local recurrence (46 per cent (24 of 52) versus 14·4 per cent (142 of 988) respectively; P < 0·001), as well as a significantly greater risk of breast cancer‐related death (42 per cent (22 of 52) versus 7·3 per cent (72 of 988) respectively; P < 0·001).

Table 2.

Type of disease relapse and breast cancer‐specific death

| No. of patients | Breast cancer‐specific death | |

|---|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 1045 | 97 (9·3) |

| Disease‐free | 853 (81·6) | n.a. |

| Relapse (all types) | 192 (18·4) | 97 (50·5) |

| Local recurrence | 52 (5·0) | 31 (60) |

| Axillary recurrence | 15 (1·4) | 8 (53) |

| SCF recurrence | 8 (0·8) | 3 (38) |

| Metastasis | 117 (11·2) | 67 (57·3) |

Values in parentheses are percentages. n.a., Not applicable; SCF, supraclavicular fossa.

The results of the univariable analysis of local recurrence are presented in Table 3. Women with ink on tumour were almost five times as likely as those with clear margins to develop local recurrence (hazard ratio (HR) 4·86; P = 0·009). Women with close margins had the same risk of local recurrence as women who had clear margins at initial surgery (HR 1·03; P = 0·954). Despite undergoing margin re‐excision and deemed to be clear, women who had re‐excision had double the risk of local recurrence compared with women with clear margins at primary surgery (HR 2·50; P = 0·005). In those who underwent re‐excision, the finding of residual disease in the re‐excision shaves was not associated with local recurrence (P = 1·000).

Table 3.

Cox univariable analysis of local recurrence

| n | Local recurrence events | Hazard ratio* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, continuous† | 1045 | 57 (5·5) | 0·97 (0·95, 1·00) | 0·022 |

| Age (years)† | ||||

| < 50 | 346 | 27 (7·8) | 1·66 (1·00, 2·80) | 0·056 |

| ≥ 50 | 699 | 30 (4·3) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Tumour size, continuous | 1039 | 56 (5·4) | 1·02 (1·00, 1·04) | 0·032 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 667 | 31 (4·6) | 1·00 (reference) | 0·098 |

| > 2 | 372 | 25 (6·7) | 1·56 (0·92, 2·64) | |

| Excision margin | ||||

| Clear | 798 | 36 (4·5) | 1·00 (reference) | 0·004 |

| Reaches | 15 | 3 (20) | 4·86 (1·49, 15·79) | 0·009 |

| Re‐excision | 122 | 13 (10·7) | 2·50 (1·32, 4·72) | 0·005 |

| Close | 110 | 5 (4·5) | 1·03 (0·40, 2·62) | 0·954 |

| Tumour grade‡ | ||||

| 1 | 160 | 3 (1·9) | 1·00 (reference) | 0·016 |

| 2 | 463 | 22 (4·8) | 2·66 (0·80, 8·88) | 0·112 |

| 3 | 420 | 32 (7·6) | 4·47 (1·37, 14·61) | 0·013 |

| Lymphovascular invasion‡ | ||||

| No | 699 | 35 (5·0) | 1·00 (reference) | 0·608 |

| Yes | 333 | 21 (6·3) | 1·15 (0·67, 1·98) | |

| ER status | ||||

| Negative | 164 | 16 (9·8) | 2·28 (1·28, 4·06) | 0·005 |

| Positive | 881 | 41 (4·7) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Final node group | ||||

| Negative | 637 | 36 (5·7) | 1·00 (reference) | 0·079 |

| Positive (N1) | 266 | 10 (3·8) | 0·63 (0·31, 1·26) | |

| Positive (N2–N3) | 82 | 4 (5) | 0·93 (0·33, 2·60) | |

| Unknown | 60 | 7 (12) | 2·25 (1·00, 5·06) | |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Age and tumour size were analysed as continuous and then as categorical variables.

Missing data for this variable.

ER, oestrogen receptor; N1, one to three nodes involved; N2, four to nine nodes involved; N3, ten or more nodes involved.

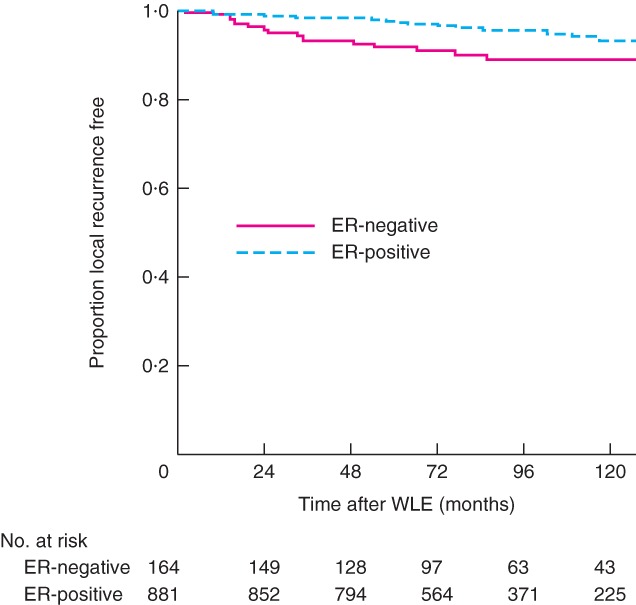

Each millimetre increase in tumour size increased the hazard of local recurrence by 1·02 (P = 0·032). Conversely, each year increase in age reduced the hazard by 0·03 (P = 0·022). Oestrogen receptor (ER)‐negative tumours were more likely to be associated with local recurrence than ER‐positive tumours (HR 2·28; P = 0·005). Local recurrence was more likely in grade 3 tumours (HR 4·47; P = 0·013). Both lymphovascular invasion and final node group were not associated with an increased risk of LR (P = 0·608 and P = 0·079 respectively) (Table 3).

In a multivariable model incorporating age, tumour size, excision margin status, grade, ER status and final node grouping, only involved excision margin and ER negativity predicted local recurrence (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox multivariable analysis of local recurrence

| Hazard ratio | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Excision margin | ||

| Clear | 1·00 (reference) | 0·002 |

| Reaches | 4·79 (1·47, 15·59) | 0·009 |

| Re‐excision | 2·70 (1·43, 5·13) | 0·002 |

| Close | 1·08 (0·42, 2·76) | 0·873 |

| ER status | ||

| Negative | 2·41 (1·35, 4·31) | 0·003 |

| Positive | 1·00 (reference) |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. Margins were defined as clear (over 1 mm), reaches (ink on tumour), re‐excision (deemed clear after re‐excision) and close (less than 1 mm but no ink on tumour). ER, oestrogen receptor.

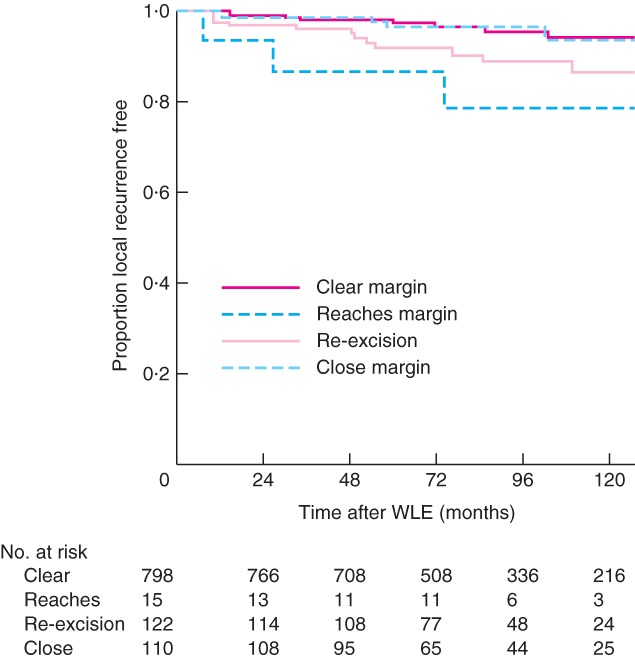

Kaplan–Meier curves of time from BCT to local recurrence for excision margin categories and ER status are shown in Figs 1 and 2 respectively. Patients known to be alive and those lost to follow‐up were censored at the time of last follow‐up or discharge from the clinic. There was no difference in local recurrence between women with clear margins and those with close margins (Fig. 1). In contrast, patients who had re‐excision of margins had an increased risk of local recurrence. Women with involved margins had the highest risk of local recurrence; this difference was most marked in the first 100 months after surgery, after which there were very few new events. Kaplan–Meier curves for ER status showed a higher local recurrence risk for ER‐negative breast cancers (Fig. 2). Local recurrence occurred within the first 100 months after surgery for ER‐negative cancers in contrast to ER‐positive tumours, which demonstrated local recurrence events at regular intervals over 200 months.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to local recurrence according to margin status. WLE, wide local excision

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to local recurrence according to oestrogen receptor status. ER, oestrogen receptor; WLE, wide local excision. Correction Note: the y‐axis for Figures 1 and 2 has been amended since first published on 26 December

Discussion

In line with previous studies13 19, 20, the univariable analysis performed here shows an association between local recurrence and young age, large tumour size, higher grade, involved margins and ER negativity. In multivariable analysis, only two variables, margin status and ER status, remained significantly associated with local recurrence. As expected, women with involved margins had the highest risk of local recurrence and were almost five times as likely to develop local recurrence compared with those with clear margins. This difference was most marked in the first 100 months after BCT, with very few events after this time.

No difference in local recurrence was seen in women with clear margins and close margins. Although there is no clear consensus regarding acceptable margin width in the UK, these findings are in line with the SSO–ASTRO guideline13 on adequate margin width in BCT. This American guideline is defined by the use of no ink on tumour as the standard for adequate margin in invasive cancer, and was introduced following the publication of a meta‐analysis of 33 studies on 28 162 patients.

An important new finding in the present study is that margin re‐excision confers only partial protection from local recurrence. Women who initially had involved margins and subsequently underwent margin re‐excision still had twice the risk of local recurrence compared with women who had clear margins at primary surgery. Furthermore, similar local recurrence rates were seen in women with residual disease in their re‐excision shaves and those who had no residual disease in the new re‐excision margin. An explanation is that the imprecise nature of margin re‐excisions can miss residual disease, and therefore those deemed to have clear margins after re‐excision in fact still had residual disease. Steps should be taken to improve the accuracy of margin re‐excision. Ideally, such surgery should be performed by the same surgeon who, in conjunction with pathology colleagues, should apply considerable effort in identifying, orienting and examining the surgical cavity and specimens. The technical challenges of returning to a previous operative site for margin clearance include failure to identify the previous cavity accurately and missing further disease by taking inadequate or inaccurate margin shavings. A study21 that compared immediate re‐excision with delayed re‐excision in wide local excisions with positive margins found almost twice as much residual disease in the early re‐excision group (P < 0·001) and supports early return to theatre before significant local repair mechanisms are established. Combined, all these issues highlight the significance of achieving clear margins at the time of the primary operation.

In 2017, the UK National Margins Audit15 found a margin re‐excision rate of 17·2 (range 0–41) per cent. The study also found22 that the current standard method of intraoperative margin assessment is specimen X‐ray (used by 96 per cent of participating UK breast units) and that patients with DCIS, invasive lobular carcinoma, higher‐grade disease, lower BMI and smaller breast cup size are at higher risk of margin re‐excision. In that study, the majority of margin re‐excisions took place for involved rather than for close margins.

Achieving complete excision in BCT without the need for re‐excision lowers local recurrence rates, enhances patient experience and reduces healthcare costs. Patients at increased risk of margin involvement should be identified and counselled appropriately when making their surgery choice. Studies have shown that patients with DCIS are at increased risk of margin re‐excision23 24, and that underestimation of tumour size by current imaging techniques is a major factor associated with incomplete excision25. The accuracy of preoperative tumour size measurements may be improved by employing additional imaging modalities such as digital tomosynthesis and MRI. Discrepancies between preoperative imaging and postoperative histological tumour size should be identified and preoperative images reviewed. The current standard for intraoperative margin assessment using specimen X‐ray suffers from poor pooled diagnostic accuracy26. New intraoperative methods of assessing margins are being developed (for example MarginProbe®, Dune Medical Devices, Framingham, Massachusetts, USA27; ClearEdge™ (LS BioPath, Saratoga, California, USA28; and Rapid Evaporative Ionization Mass Spectrometry™ (REIMS™) iKnife™, Waters Corporation, Milford, Massachusetts, USA29) and will need to be evaluated formally in clinical trials.

Although the pathophysiology of local recurrence is not fully understood, it is generally recognized that there are two distinct types: recurrences that arise in the residual organ not involved in the surgery for the primary tumour, and scar recurrences that develop at the site of the previous tumour resection30. Field cancerization, in which there are genetically altered but microscopically normal cells, may offer an explanation for in situ recurrences, whereas scar recurrences can be accounted for by the presence of minimal residual disease31. Lesions that form in situ recurrences may not be apparent at histopathological examination, but can be detected by molecular analyses for phenotypic, genetic or epigenetic alterations, which include p53 mutations, loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite instability, DNA methylation and integrated viral DNA. Studies32 33 have confirmed such changes at increasing distances from the wide local excision site. In the context of broader field change, concentrating on the immediate surrounds of the tumour alone accounts only partially for local recurrence risk. In the present study, the local recurrence rate of 5·0 per cent is in line with the 2014 meta‐analysis14 of margins and local recurrence, which found a median rate of 5·3 per cent. This residual local recurrence rate of 5·0 per cent in the presence of microscopic clearance provides additional support for the field effect. In breast cancer, cells affected by field change are subjected to similar environmental carcinogens such as oestrogen. For ER‐positive cancers, adjuvant endocrine treatment alters the non‐tumour breast as well as the tumour bed environment and generates conditions less favourable to local disease relapse34, 35, 36. However, the increased likelihood of local recurrence in ER‐negative cancers seen in the present study, and other studies37, 38, 39 showing increased relapse in triple‐negative cancers even following mastectomy, suggest that other variables such as chemokines and growth factors must also contribute to local relapse. Because of the early study period (1997–2007), there were insufficient retrospective data to assess the effect of progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 on local recurrence. Prospective studies are indicated to investigate the impact of these receptors and other methods of tumour profiling such as Ki‐67 and Oncotype DX® (Genomic Health, Redwood City, California, USA) testing on local recurrence in a UK cohort.

Although the mechanisms that underpin local recurrence after BCT are multifactorial, this study reinforces the importance of complete margin clearance and ER status. Narrow margin widths, even if less than 1 mm, confer equivalent local control compared with wider margins. The improvement in outcome is attributed to better adjuvant therapies in an era of aromatase inhibitors, taxanes and biological therapy, along with more consistent delivery of radiotherapy. Further reduction in local recurrence rates in the future should be seen if complete margin clearance can be achieved at the time of primary surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all members of the Royal Marsden Hospital multidisciplinary team who contributed to patient care during this study. They also acknowledge their colleague, the late G. Querci della Rovere, who initiated this project with a pilot study of the Sutton patients at the Royal Marsden NHS Trust.

This study was funded by a Joint BASO ∼ The Association for Cancer Surgery and Royal College of Surgeons One Year Fellowship in Cancer Research, the Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden NHS Trust, the Institute of Cancer Research and the Shocking Pink Party Appeal.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information

2010 Joint BASO ∼ The Association for Cancer Surgery and Royal College of Surgeons One Year Fellowship in Cancer Research

Biomedical Research Centre at Royal Marsden NHS Trust

Institute of Cancer Research

Shocking Pink Party Appeal

References

- 1. Poggi MM, Danforth DN, Sciuto LC, Smith SL, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ et al Eighteen‐year results in the treatment of early breast carcinoma with mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy: the National Cancer Institute Randomized Trial. Cancer 2003; 98: 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arriagada R, Lê MG, Guinebretière JM, Dunant A, Rochard F, Tursz T. Late local recurrences in a randomised trial comparing conservative treatment with total mastectomy in early breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 1617–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blichert‐Toft M, Nielsen M, Düring M, Møller S, Rank F, Overgaard M et al Long‐term results of breast conserving surgery vs. mastectomy for early stage invasive breast cancer: 20‐year follow‐up of the Danish randomized DBCG‐82TM protocol. Acta Oncol 2008; 47: 672–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Dongen JA, Voogd AC, Fentiman IS, Legrand C, Sylvester RJ, Tong D et al Long‐term results of a randomized trial comparing breast‐conserving therapy with mastectomy: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 10801 trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER et al Twenty‐year follow‐up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1233–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A et al Twenty‐year follow‐up of a randomized study comparing breast‐conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Al‐Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36: 1938–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hashemi E, Kaviani A, Najafi M, Ebrahimi M, Hooshmand H, Montazeri A et al Seroma formation after surgery for breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2004; 2: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez EA, Saltzstein EC, Riedner CS, Nelson BK. Seroma formation following breast cancer surgery. Breast J 2003; 9: 385–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger‐Raab A, Sauer H, Hölzel D. Quality of life following breast‐conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5‐year prospective study. Breast J 2004; 10: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) , Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor C, Arriagada R et al Effect of radiotherapy after breast‐conserving surgery on 10‐year recurrence and 15‐year breast cancer death: meta‐analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378: 1707–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, Davies C, Elphinstone P, Evans V et al; Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15‐year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005; 366: 2087–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, Harris JR, Khan SA, Horton J et al Society of Surgical Oncology–American Society for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast‐conserving surgery with whole‐breast irradiation in stages I and II invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 704–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, Morrow M. The association of surgical margins and local recurrence in women with early‐stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast‐conserving therapy: a meta‐analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang SS, Kaptanis S, Haddow JB, Mondani G, Elsberger B, Tasoulis MK et al Current margin practice and effect on re‐excision rates following the publication of the SSO–ASTRO consensus and ABS consensus guidelines: a national prospective study of 2858 women undergoing breast‐conserving therapy in the UK and Ireland. Eur J Cancer 2017; 84: 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. Clinical Guideline CG80; 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG80 [accessed 5 November 2018].

- 17.Association of Breast Surgery. ABS Consensus Statement: Margin Width in Breast Conservation Surgery; 2015. https://associationofbreastsurgery.org.uk/media/64245/final‐margins‐consensus‐statement.pdf [accessed 8 November 2018].

- 18. Yu J, Elmore LC, Cyr AE, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Margenthaler JA. Cost analysis of a surgical consensus guideline in breast‐conserving surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2017; 225: 294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mechera R, Viehl CT, Oertli D. Factors predicting in‐breast tumor recurrence after breast‐conserving surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 116: 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miles RC, Gullerud RE, Lohse CM, Jakub JW, Degnim AC, Boughey JC. Local recurrence after breast‐conserving surgery: multivariable analysis of risk factors and the impact of young age. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 1153–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nasir N, Rainsbury RM. The timing of surgery affects the detection of residual disease after wide local excision of breast carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2003; 29: 718–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tang SS, Kaptanis S; National Margins Audit Collaborative. Variables associated with margin re‐excision in breast conserving therapy (BCT) – results from the National Margins Audit. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017; 43: S4. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Langhans L, Jensen MB, Talman MM, Vejborg I, Kroman N, Tvedskov TF. Reoperation rates in ductal carcinoma in situ vs invasive breast cancer after wire‐guided breast‐conserving surgery. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeevan R, Cromwell DA, Trivella M, Lawrence G, Kearins O, Pereira J et al Reoperation rates after breast conserving surgery for breast cancer among women in England: retrospective study of hospital episode statistics. BMJ 2012; 345: e4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dixon JM, Newlands C, Dodds C, Thomas J, Williams LJ, Kunkler IH et al Association between underestimation of tumour size by imaging and incomplete excision in breast‐conserving surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 830–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. St John ER, Al‐Khudairi R, Ashrafian H, Athanasiou T, Takats Z, Hadjiminas DJ et al Diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative techniques for margin assessment in breast cancer surgery: a meta‐analysis. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thill M. MarginProbe: intraoperative margin assessment during breast conserving surgery by using radiofrequency spectroscopy. Expert Rev Med Devices 2013; 10: 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon JM, Renshaw L, Young O, Kulkarni D, Saleem T, Sarfaty M et al Intra‐operative assessment of excised breast tumour margins using ClearEdge imaging device. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. St John ER, Balog J, McKenzie JS, Rossi M, Covington A, Muirhead L et al Rapid evaporative ionisation mass spectrometry of electrosurgical vapours for the identification of breast pathology: towards an intelligent knife for breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res 2017; 19: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Höckel M, Dornhöfer N. The hydra phenomenon of cancer: why tumors recur locally after microscopically complete resection. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 2997–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer 1953; 6: 963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vaidya JS, Vyas JJ, Chinoy RF, Merchant N, Sharma OP, Mittra I. Multicentricity of breast cancer: whole‐organ analysis and clinical implications. Br J Cancer 1996; 74: 820–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holland R, Veling SH, Mravunac M, Hendriks JH. Histologic multifocality of Tis, T1–2 breast carcinomas. Implications for clinical trials of breast‐conserving surgery. Cancer 1985; 56: 979–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liljegren G. Is postoperative radiotherapy after breast conserving surgery always mandatory? A review of randomised controlled trials. Scand J Surg 2002; 91: 251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yaghan R, Stanton PD, Robertson KW, Going JJ, Murray GD, McArdle CS. Oestrogen receptor status predicts local recurrence following breast conservation surgery for early breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 1998; 24: 424–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fredriksson I, Liljegren G, Palm‐Sjövall M, Arnesson LG, Emdin SO, Fornander T et al Risk factors for local recurrence after breast‐conserving surgery. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 1093–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang SL, Li YX, Song YW, Wang WH, Jin J, Liu YP et al Triple‐negative or HER2‐positive status predicts higher rates of locoregional recurrence in node‐positive breast cancer patients after mastectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 80: 1095–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lowery AJ, Kell MR, Glynn RW, Kerin MJ, Sweeney KJ. Locoregional recurrence after breast cancer surgery: a systematic review by receptor phenotype. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 133: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kyndi M, Sørensen FB, Knudsen H, Overgaard M, Nielsen HM, Overgaard J; Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group . Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER‐2, and response to postmastectomy radiotherapy in high‐risk breast cancer: the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1419–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]