Abstract

Regional anesthesia is a commonly used adjunct to orofacial dental and surgical procedures in companion animals and humans. However, appropriate techniques for anesthetizing branches of the mandibular and maxillary nerves have not been described for rhesus monkeys. Skulls of 3 adult rhesus monkeys were examined to identify relevant foramina, establish appropriate landmarks for injection, and estimate injection angles and depth. Cadaver heads of 7 adult rhesus monkeys (4 male, 3 female) were then injected with thiazine dye to demonstrate correct placement of solution to immerse specific branches of the mandibular and maxillary nerves. Different volumes of dye were injected on each side of each head to visualize area of diffusion, and to estimate the minimum volume needed to saturate the area of interest. After injection, the heads were dissected to expose the relevant nerves and skull foramina. We describe techniques for blocking the maxillary nerve as well as its branches: the greater palatine nerve, nasopalatine nerve, and infraorbital nerve. We also describe techniques for blocking branches of the mandibular nerve: inferior alveolar nerve, mental (or incisive) nerve, lingual nerve, and long buccal nerve. Local anesthesia for the mandibular and maxillary nerves can be accomplished in rhesus macaques and is a practical and efficient way to maximize animal welfare during potentially painful orofacial procedures.

Rhesus macaques are one of the most common NHP species housed in research facilities in North America.13 Treatment of dental disease and orofacial trauma is part of routine veterinary care for these animals. Furthermore, macaques are used as models of dental disease, including studies involving surgical manipulation.1,5 Adequate analgesia during painful procedures is pivotal to providing the best possible quality of life for research macaques and is listed in the Guide as a key component of good veterinary care.11,26

For most routine dental extractions and minor laceration repairs, local anesthetics can be used effectively as local infiltration applied adjacent to the surgical site.6,12 However, some circumstances warrant the use of regional blocks. First, because mandibular bone is denser than maxillary bone, anesthetics do not diffuse into mandibular bone as effectively as for maxillary bone.21 For this reason, regional blocks may be better suited to complicated mandibular extractions than local infiltration. Second, local anesthetics may not be as effective when injected into inflamed compared with noninflamed tissue.15 Therefore, when working in areas with severe periodontal disease or infection, a regional block applied in an area remote to the surgical site is useful. Third, extensive orofacial trauma or multiple extractions may require local infiltration in excess of dosage limits; regional blocks numb larger areas with relatively small amounts of anesthetic, avoiding possible systemic toxicity. Fourth, complicated extractions of teeth with large deep roots, such as maxillary canines, may benefit from a block of the entire affected area. And finally, injection in an area remote to the surgical site is indicated to avoid tumor seeding when providing analgesia for biopsy or removal of orofacial neoplasms.

Regional blocks are used in both humans and companion animals during orofacial surgical procedures as an adjunct to general anesthesia and systemic analgesics. In human dentistry, local anesthetics are used for procedures performed without general anesthesia. In companion animals, local anesthetics are used to decrease the amount of general anesthetic and systemic analgesics necessary, to provide preemptive analgesia, and to provide effective analgesia in the immediate postoperative phase.6,14 All of these reasons likewise apply in NHP dental procedures. In addition, local anesthetics have negligible systemic effects when appropriately administered. This characteristic makes them a good option for NHPs on studies that may limit the use of other classes of analgesics.

Despite many resources describing appropriate techniques for orofacial regional anesthesia in companion animals and humans, these techniques have not been specifically described for rhesus macaques.6-8,12,14 This dearth has left practitioners to extrapolate from techniques used in other species. However, macaque anatomy is well described and is sufficiently different from that of both carnivores and humans to necessitate technique descriptions for NHP species.

In this project, we examined skulls and intact heads of adult rhesus monkeys to satisfy 3 main goals: 1) to establish anatomic landmarks to access relevant branches of the maxillary and mandibular nerves; 2) to verify that agents injected at a predetermined angle and depth consistently reached the desired nerves; and 3) to establish appropriate injection volumes to saturate the area of interest.

Materials and Methods

No living animals were used in this study. Three preserved skulls of adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were examined; intact heads of 7 adult rhesus macaques (3 female, 4 male; age, 5 y 11 mo to 9 y 4 mo) were used also.

To establish anatomic landmarks to access relevant branches of the maxillary and mandibular nerves, 3 adult skulls were examined. The following fissure and foramina were identified: pterygomaxillary fissure, infraorbital foramina, greater palatine foramen, nasopalatine foramen, mandibular foramen, and mental foramen. Then landmarks were identified to estimate appropriate injection angles and depth to deposit solution near these foramina. The reliability of these landmarks was verified during subsequent dissection of each intact head. In addition, these anatomic landmarks were noted during each dissection to ensure that they did not differ markedly between male and female macaques or among subjects of the same sex.

Thiazine dye was injected into intact heads to verify that agents injected at predetermined angles and depth consistently reached the desired nerves. Dye was injected to saturate proximal portions of the maxillary, greater palatine, nasopalatine, infraorbital, inferior alveolar, mental (or incisive), lingual nerve, and long buccal nerves. After injection, relevant nerves and skull foramina were isolated during dissection of each head to verify that dye had reached the desired area. Minor adjustments were made with each head until results were consistent.

Different volumes of thiazine dye were injected on each side of each intact head to establish the minimal volumes needed to saturate the area of interest. The area of diffusion was noted during subsequent dissection. The palatine, nasopalatine, mental (or incisive), lingual, and long buccal nerves were injected at volumes of 0.1 and 0.2 mL. The inferior alveolar, infraorbital, and maxillary nerves received volumes of 0.2 and 0.4 mL.

Results

Maxillary nerve.

The maxillary nerve supplies sensation to the side of the nose, lower eyelid, upper lip, maxillary palate, maxillary teeth, and maxillary gingiva. The maxillary nerve exits the skull via the foramen rotundum, travels briefly through the pterygopalantine fossa, and then enters the inferior orbital fissure.2 The nerve is best accessed as it travels through the narrow pterygopalantine fossa. The fossa was found to be accessible by using 2 approaches. The pterygopalantine fossa communicates with the infratemporal fossa through the pterygomaxillary fissure (Figure 1 A). A 1- to 1.5-in., 22-gauge needle was found to be most appropriate, with shorter needles being adequate for smaller, female macaques. The needle was inserted at the mucobuccal fold dorsal to M2 at an angle of 30 to 45 degrees from the hard palate and 45 degrees lateral to midline (Figure 1 A and B). The needle was then directed along the caudal surface of the maxilla until it contacted the bone of the infratemporal fossa. Prior to injection, the needle tip was withdrawn a few millimeters. Keeping the needle flush with the caudal surface of the maxilla avoided injection into the masseter muscle as compared with between the muscle and bone. Volumes of 0.2 and 0.4 mL of thiazine dye were injected by using this technique; 0.4 mL of solution provided a wider area of saturation and covered the area of interest, even with some variation in injection technique.

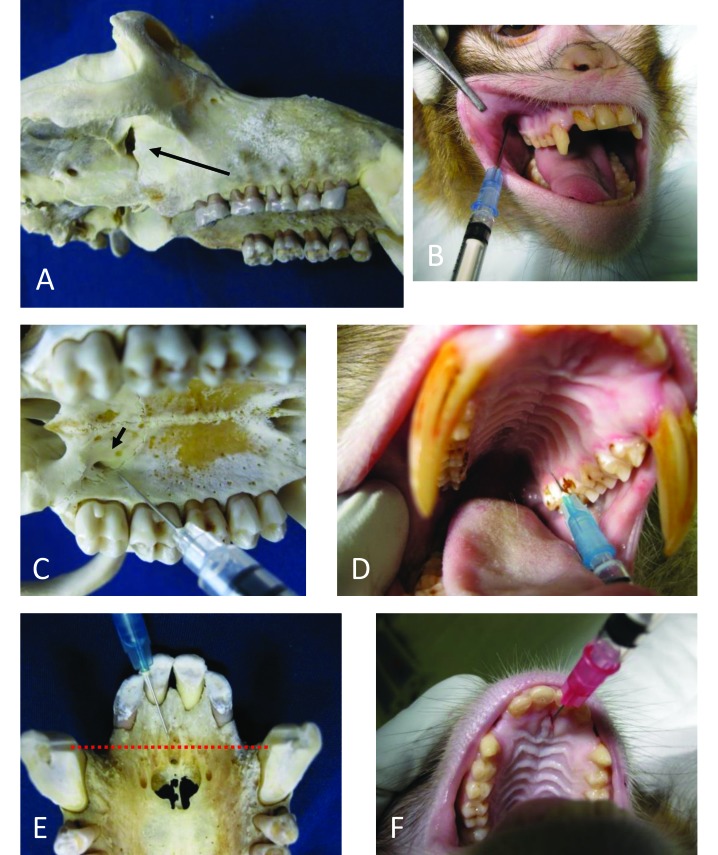

Figure 1.

Blocks of the maxillary, greater palatine, and nasopalatine nerves in rhesus macaques. (A) The arrow points to the pterygomaxillary fissure and shows the approximate path of the needle from the mucobuccal fold dorsal to M2. (B) Injection angle to access the maxillary nerve via the pterygomaxillary fissure shown on a cadaver. (C) Arrow points to the greater palatine foramen medial to M3. (D) Injection angle to saturate the greater palatine nerve as it exits the greater palatine foramen shown on a cadaver. (E) Incisive foramina. The dotted line shows ideal placement of local anesthetic between the cranial edge of the canines. (F) Injection lateral to the incisive papilla shown on a cadaver.

The pterygopalantine fossa also communicates with the oral cavity through the greater palatine foramen. This foramen is found 2 to 3 mm medial to the 3rd maxillary molar (Figure 1 C). A 0.5-in., 27-gauge needle was used to enter the greater palatine foramen and was then advanced a few millimeters for injection. Holding pressure over the injection site after injection encouraged diffusion into the foramen and pterygopalantine fossa. Delivery of thiazine dye at 0.1 and 0.2 mL were attempted by using this technique, but only 0.1 mL was successful due to the small size of the foramen and fossa. The risk of lacerating the greater palatine nerve is considerable when using this technique, but it is technically easier to perform.

Greater palatine nerve.

The greater palatine nerve is a branch of the maxillary nerve supplying sensory enervation to the maxillary palate abutting the maxillary molars and premolars. It exits the skull via the greater palatine foramen, which is located 2 to 3 mm medial to the 3rd molar2 (Figure 1 C). A 0.75-in., 25-gauge (or smaller) needle was used. The needle was inserted into the palate at the caudomedial edge of M2 and angled slightly toward M3. It was then advanced dorsally until the tip contacted the bone of the hard palate (Figure 1 D). There is no need to enter the greater palatine foramen. If the needle slips inside of the foramen, it should be withdrawn slightly before injection, to avoid affecting the entire maxillary nerve. There was very little space between the hard palate and underlying bone. Delivery of thiazine dye at 0.1 and 0.2 mL were attempted, and 0.2 mL provided a greater area of saturation. However, with good placement, 0.1 mL was sufficient to diffuse around the greater palatine nerve at its exit point from the greater palatine foramen.

Nasopalatine nerve.

The nasopalatine nerve is a branch of the maxillary nerve and exits the skull at the incisive foramen.2 All of the skulls examined and heads dissected had smaller accessory foramina on either side of the incisive foramen, where smaller branches of the nerve exit (Figure 1 E). The nasopalatine nerve supplies sensory innervation to the hard palate abutting the maxillary canines and incisors.2 This injection was best performed by using a 0.75-in, 25-gauge needle. A volume of 0.2 mL was sufficient to block all of the branches emerging from all foramina simultaneously, when injected immediately lateral to the incisive papilla, directed dorsally approximately 15 degrees from the hard palate (Figure 1 F). The ideal placement was along an imaginary line drawn between the cranial edges of the canines (Figure 1 E); 0.1 mL of solution was sufficient to diffuse around the nerve unilaterally. For a unilateral block, the needle was inserted between incisors 1 and 2, aimed at the cranial edge of the canine; 0.1 mL was injected when the needle contacted the bone of the hard palate.

Infraorbital nerve and superior alveolar nerves.

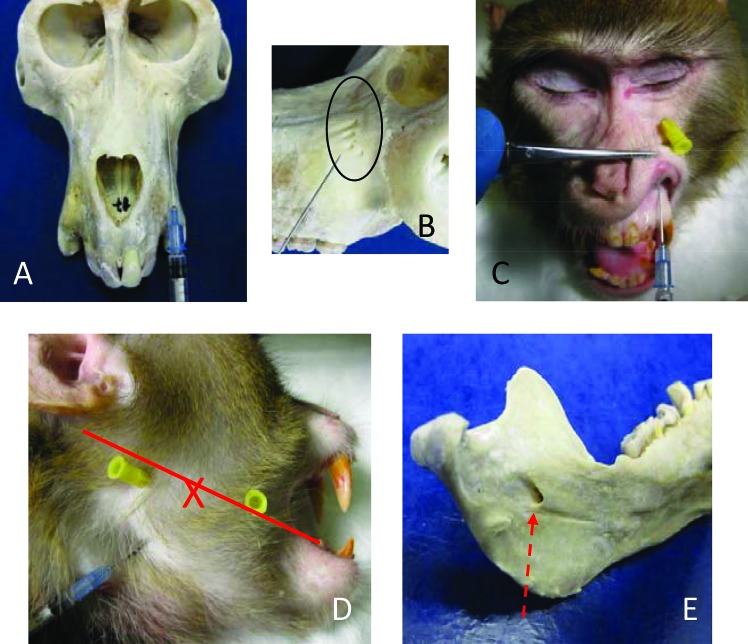

The infraorbital nerve is a branch of the maxillary nerve that exits the skull through the infraorbital foramina, located along the bony ridge just ventral to the eye.2 All of the skulls and heads examined had multiple infraorbital foramina (3 to 5). The largest foramen was at the midpoint of the orbit, with any accessory foramina trailing laterally (Figure 2 B). The anterior and middle superior alveolar nerves, which supply the maxillary incisors, canines, and premolars, branch off the infraorbital nerve as it travels along the floor of the orbit from the inferior orbital fissure to the infraorbital foramina. The alveolar nerves then enter the cancellous bone of the maxilla.2 Therefore, any effective block depends on diffusion into the infraorbital foramina and into the porous bone of the maxilla. A 1-in., 22-gauge needle was needed. The most reliable approach was to insert the needle at the mucobuccal fold over the canine and to direct the tip toward the midpoint of the eye along the maxillary bone (Figure 2 A and C). When the needle contacted the bony ridge below the eye; before injection, the tip was withdrawn a few millimeters. After injection, pressure was applied over the site to encourage diffusion into the foramina. We test-injected 0.2 and 0.4 mL; a volume of 0.4 mL provided for a better diffusion area, encompassing all of the infraorbital foramina.

Figure 2.

Blocks of the infraorbital and inferior alveolar nerves. (A) Injection angle aimed at the largest infraorbital foramen. (B) Multiple infraorbital foramina. (C) Infraorbital block injection shown on cadaver. The yellow-hubbed needle is inserted into the largest infraorbital foramen for reference. (D) Inferior alveolar injection shown on intact head; yellow-hubbed needles mark the caudal and cranial margins of the vertical mandibular ramus. The red line marks the occlusal plain of the mandibular molars. The X marks the midpoint of the line and approximate location of the mandibular foramen. (E) Medial surface of the mandible showing the mandibular foramen. The red dotted arrow shows path of needle during injection.

Inferior alveolar nerve.

The inferior alveolar nerve is a branch of the mandibular nerve; it travels down the ramus of the mandible and enters the caudomedial surface of the mandible through the mandibular foramen. The inferior alveolar nerve innervates the roots of all mandibular teeth and associated soft tissue, with the possible exception of the buccal aspect of the molars.2 An extraoral approach was most effective at avoiding the lingual nerve. A 1-in., 22-gauge needle was used. The injection point was found by palpating the edges of the vertical mandibular ramus on a line parallel to the occlusal surface of the mandibular molars; the mandibular foramen is at the midpoint of the ramus along this line (Figure 2 D). The needle was inserted on the curve of the ramus, angled against the mandible and toward the midpoint of the line. Solution was injected once the midpoint was reached (Figure 2 D and E). The needle should be kept as close to the bone as possible to avoid injecting into the medial pterygoid muscle or lingual nerve. A volume of 0.2 mL of dye provided adequate diffusion on all of the female macaques examined; the male macaques examined required 0.4 mL of dye for adequate diffusion.

Mental nerve.

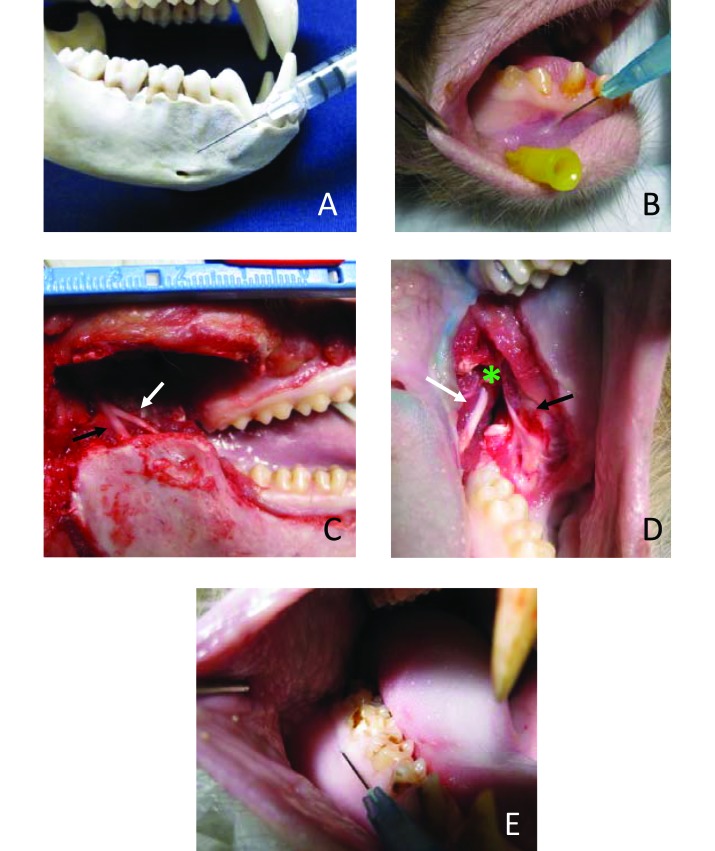

The mental nerve exits the mandible at the mental foramen and enervates the soft tissues of the mandible abutting the canines and incisors. Just inside the mental foramen, the incisive nerve continues rostrally, to supply the roots of the mandibular canines and incisors.2 On all skulls and heads examined, the mental foramen was located along the ventral edge of the mandible, between premolars 1 and 2 (Figure 3 A). A 0.75- or 0.5-in., 25-gauge needle was used. The needle was inserted at the mucobuccal fold below the canine and angled caudally toward the foramen (Figure 3 A and B). Pressure was held on the site after injection to encourage diffusion into the foramen, affecting the incisive nerve. A volume of 0.1 mL of dye was sufficient to provide adequate diffusion in all of the male and female macaques examined.

Figure 3.

Blocks of the mental, lingual, and long buccal nerves. (A) Mental foramen and injection angle. (B) Mental injection on cadaver. Yellow-hubbed needle is inserted into mental foramen for reference. (C) Cadaver with vertical mandibular ramus removed. The black arrow indicates the inferior alveolar nerve; the white arrow indicates lingual nerve. (D) Lingual nerve shown passing over the mandible at the mandibular notch (green asterisk). The white arrow indicates the lingual nerve; the black arrow indicates the long buccal nerve. (E) Long buccal block injection into the buccal gingiva adjacent to the mandibular molars.

Lingual nerve.

The lingual nerve branches off the mandibular nerve after it exits the foramen ovale. The lingual nerve then runs craniomedial to the inferior alveolar nerve along the vertical mandibular ramus. It then crosses over the mandible just caudal to M3, and enters the soft tissue of the tongue (Figures 3 C and D). The lingual nerve provides sensory innervation to the rostral 2/3 of the tongue.2 Applications for this block are limited. However, the nerve can be accessed as it crosses the mandible by injection of solution into the soft tissue between the mandibular notch and the 3rd mandibular molar (Figure 3 D). A volume of 0.2 mL of dye provided adequate diffusion.

Long buccal nerve.

The long buccal nerve is a branch of the mandibular nerve that supplies the buccal soft tissue of the mandibular molars. The main branch can be found at the mandibular notch with smaller fibers running into the buccal gingiva and cheek around the molars. (Figure 3 D). The long buccal nerve block can be used as an adjunct to the inferior alveolar nerve block when extracting mandibular molars. A 0.75-in., 25-gauge or smaller needle was adequate; the needle was inserted 2 to 3 mm into the buccal gingiva adjacent to the molar to be extracted (Figure 3 E). A volume of 0.1 mL provided adequate diffusion. When 0.2 mL was injected adjacent to the 3rd molar, dye diffused caudally to reach the lingual nerve.

Discussion

Multimodal analgesia is recommended to maximize pain control yet minimize the side effects of any one particular drug.10 Local anesthesia is an essential part of the analgesic arsenal. Local anesthetics provide preemptive analgesia via sensory blockade, allowing the practitioner to use lower doses of cardiovascular depressants such as isoflurane and opioids.15,23,27 Decreased use of such depressants is a welfare benefit to any animal but is especially advantageous in geriatric or ill patients. The presence of a local sensory block is also beneficial in the immediate postoperative period, because it decreases the need to provide analgesia either parenterally or by mouth while the local block is in effect. In addition, effective postoperative pain control encourages the patient to eat, which can sometimes be an issue after oral surgery.

Lidocaine and bupivacaine are commonly used local anesthetics in veterinary medicine. The approximate onset of action of lidocaine is 10 to 15 min, with an effective duration of 1 to 2 h. Bupivacaine may take as long as 30 min to provide sensory blockade and is effective for a maximum of 6 h. The duration of action of both drugs can be extended by the addition of epinephrine to the local injection.8 Additional evidence suggests that using a combination of bupivacaine and the opioid buprenorphine as a local injection may provide analgesia for more than 24 h.19,23

Overall, the techniques that we described here for rhesus macaques are similar to those performed in humans and companion animals. However, some differences should be mentioned. In humans, the 2nd and 3rd maxillary molars can be blocked by anesthetizing the posterior superior alveolar nerve.7,12 In people, this nerve branches off of the maxillary nerve before it enters the orbit, exits the pterygomaxillary fissure, and travels rostrally to enter the infratemporal surface of the maxilla.18 We were unable to isolate this nerve during dissection of any of the heads examined, because it branches off of the infraorbital nerve within the orbit and enters the maxilla with the other superior alveolar nerves.2 Therefore, the only regional block that affects the maxillary molars of rhesus macaques is a block of the entire maxillary nerve.

However, the need for the maxillary nerve block is limited owing to the porous nature of the maxilla. Given that solution readily diffuses into the maxilla, routine maxillary extractions can be performed with simple local infiltration. Local infiltration—the injection of a small amount of local anesthetic into the gingiva overlying the tooth of interest—is easy to perform and provides analgesia to the area of diffusion.8,9 However, multiple local infiltration injections would be needed to anesthetize large areas and thus may cumulatively surpass the dosage limits of the anesthetic. Therefore, the maxillary block may be needed to avoid anesthetic overdose with extensive repairs or to avoid large areas of inflammation.

With the exception of the mandibular foramen, the skull foramina of rhesus macaques are smaller than those in humans and companion animals. This difference is especially marked when examining the infraorbital foramen. Carnivores have a single, relatively large, infraorbital foramen. Humans have a large main infraorbital foramen and may have smaller accessory foramina. In these species, techniques are described in which a needle is directed into the foramen to block the middle and anterior superior alveolar nerves with a relatively low chance of lacerating the infraorbital nerve.9,14,18 In contrast, rhesus macaques have 2 or more, small, infraorbital foramina25 (Figure 2 B). In rhesus macaques, the infraorbital block relies on diffusion into the infraorbital foramina and through the cancellous bone of the maxilla to provide anesthesia of the alveolar nerves supplying the teeth. Inserting a needle into any of the infraorbital foramina of a rhesus macaque would be technically challenging, would risk laceration of the nerve passing through the foramen, and is unnecessary to saturate the nerves of interest.

The location of the lingual nerve is described largely so that it can be avoided while blocks of the inferior alveolar nerve or long buccal nerve are applied. The lingual nerve is separated from the mandibular foramen by less than 1 cm of soft tissue and lies adjacent to the long buccal nerve as it passes over the mandibular notch (Figure 3 C and D). Inadvertently numbing the lingual nerve could lead to tongue chewing. However, the application of a lingual block may be indicated if the rostral 2/3 of the tongue is damaged. Socially housed rhesus macaques do occasionally sustain traumatic tongue injuries during fights.

Complications associated with orofacial regional anesthesia are rare and usually transient. There is the possibility for self-mutilation when the lips, cheeks, or tongue are numb. In humans, this drawback is of most concern for patients that cannot follow postoperative instructions well, such as children or mentally disabled people.4,12 Injury of numbed lips, cheeks, or tongue has also been reported in companion animals.6 We have not seen any self-trauma in the few rhesus macaques that have received these blocks. However, close monitoring of patients during the postoperative period is advised.

Pain and paresthesia from intraneural injection are possible complications of any regional block. This side effect can be avoided by depositing anesthetic close to the foramen, rather than entering the foramen with the needle.6 In addition, nerve damage is more severe when local anesthetics are injected under pressure. Anesthetics should be injected slowly, and the needle should be withdrawn if the operator must exert undue pressure during injection.17

Systemic toxicity is another potential complication of local anesthetic use. Unintended intravascular injection of large amounts of anesthetic can lead to almost immediate cardiovascular collapse and seizures.8,17,20 Fortunately, this outcome can be avoided by repeated aspiration prior to injection.15 An overdose of local anesthetics can also cause toxicity, even if properly placed. As the anesthetic is absorbed, and plasma levels become excessive, a more delayed display of CNS and cardiovascular signs can be seen.15 It is very important to be aware of the dosage limits of the anesthetic used relative to the weight of the patient. In addition, the effects of different local anesthetics are cumulative, so a second anesthetic cannot be used after dosage limits have been reached with the first drug administered.17,20 In one study, seizure activity was induced in adult rhesus macaques after cumulative intravenous injection of 22.5 mg/kg lidocaine or 4.4 mg/kg bupivacaine.22 In practice, maximum safe doses of local anesthetics for rhesus macaques are often extrapolated from recommendations for humans and dogs, which are both well below the seizure threshold for macaques. For dogs, the recommended cumulative dose for lidocaine is 5 mg/kg and for bupivacaine is 2 mg/kg.8 In humans, the recommended cumulative dose of lidocaine is 4.4 mg/kg and of bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine is 1.3 mg/kg.20

The inferior alveolar nerve block has a variable reported success rate in people.16,21 In addition, this block is the most likely to result in self-mutilation, the most likely to result in inadvertent intravascular or intraneural injection, and can result in myotoxicity and trismus.17 The reported increased likelihood of self-mutilation and intraneural injection with the inferior alveolar block are more commonly associated with damage to the lingual nerve rather than the inferior alveolar nerve. The extraoral approach that we described here is less likely to damage the lingual nerve than the intraoral approach commonly used in people. However, due to the many complications that can occur if this block is administered incorrectly, it should be used sparingly. There is evidence that 4% articaine may be capable of providing analgesia of the mandibular teeth with simple infiltration injections.12,17 In addition, injection into the periodontal ligament, or directly into the alveolar bone associated with the tooth of interest both show promise to supplant the inferior alveolar block. However, intraligamentary and intraosseous injections are best performed with specialized equipment to ensure that the anesthetic is injected with appropriate pressure to force diffusion into the cancellous bone of the mandible.21

In people, the superior alveolar and inferior alveolar regional blocks have been reported to cause rare but serious neurologic complications including facial nerve palsy, abducens nerve palsy, and defects of the auditory and visual systems.3,17,24 The maxillary and inferior alveolar nerve blocks we described in the current study require similar placement into areas of the head crowded with nerves and vessels supplying the face, eyes, and ears of rhesus macaques. Neurologic complications can arise from direct nerve damage during injection, diffusion of the injected anesthetic to unintended structures, or inadvertent intravascular injection carrying anesthetic to sites remote from the injection site.3,24 Recommendations for avoiding these complications include injecting slowly, aspirating frequently, and carefully placing the anesthetic. However, even with perfect injection technique, it is possible to numb adjacent nerves.17

Orofacial regional anesthesia is a useful adjunct to systemic analgesics. Applications in rhesus macaques include analgesia related to dental procedures, treatment of trauma, and pain control during study procedures. Complications of similar techniques in other species are rare and largely transitory. Further data are needed to evaluate the frequency of complications in rhesus macaques.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michelle Browning, Dr Jessica Izzi, Dr Kelly Rice, and the laboratories of Dr Malcolm Martin and Dr Jeffrey Lifson for project support. We also thank Dr Victoria Hoffmann and Dr Lauren Brinster for their help with tissue collection.

References

- 1.Alzarea BK. 2014. Selection of animal models in dentistry: State of art, review article. J Anim Vet Adv 13:1080–1085. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen K. 1961. The cranial nerves, p 290–306. In: Hartman CG, Straus WL, The Anatomy of the Rhesus Monkey, New York (NY) Hafner Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crean SJ, Powis A. 1999. Neurological complications of local anaesthetics in dentistry. Dent Update 26:344–349. 10.12968/denu.1999.26.8.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crespi PV, Friedman RB. 1986. Prevention of postanesthetic oral self-mutilation. Spec Care Dentist 6:68–69. 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1986.tb00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner MB, Luciw PA. 2008. Macaque models of human infectious disease. ILAR J 49:220–255. 10.1093/ilar.49.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorrel C, Andersson S. 2013. Anesthesia and analgesia, p 15–29. In: Gorrel C, Andersson S, Verhaert L, Veterinary dentistry for the general practitioner, 2nd ed Philadelphia (PA) Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gremillion HA, Spencer CJ, Erlich AD. 2011. Local anesthesia of the masticatory region, p 483–504. In: Kaye AD, Urman RD, Vadivelu N, Essentials of regional anesthesia. New York (NY) Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heavner JE. 1999. Local anesthetic and analgesic techniques, p 192–224. In: Thurmon JC, Tranquilli WJ, Benson GJ, Essentials of small animal anesthesia and analgesia, 1st ed Philadelphia (PA) Lippencott Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmstrom SE, Fitch PF, Eisner ER. 2004. Regional and local anesthesia, p 625–636. In: Holmstrom SE Fitch PF Eisner ER, Veterinary dental techniques for the small animal practitioner, Philadelphia (PA) Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2009. Recognition and alleviation of pain in laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones JE, Dean JA. 2016. Local anesthesia and pain control for the child and adolescent, p 274–285. In: Dean JA, McDonald and Avery's dentistry for the child and adolescent, 10th ed Philadelphia (PA) Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lankau EW, Turner PV, Mullan RJ, Galland GG. 2014. Use of nonhuman primates in research in North America. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 53:278–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lantz GC. 2003. Regional anesthesia for dentistry and oral surgery. J Vet Dent 20:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lirk P, Picardi S, Hollmann MW. 2014. Local anaesthetics: 10 essentials. Eur J Anaesthesiol 31:575–585. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malamed SF. 2011. Is the mandibular nerve block passé? J Am Dent Assoc 142 Suppl 3:3S–7S. 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meechan JG. 2009. Local anaesthesia: risks and controversies. Dent Update 36:278–280. 10.12968/denu.2009.36.5.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merritt G, Walji AH, Tsui BCH. 2016. Clinical anatomy of the head and neck, p 135–147. In: Tsui BCH, Suresh S, Pediatric atlas of ultrasound and nerve stimulation-guided regional anesthesia. New York (NY) Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modi M, Rastogi S, Kumar A. 2009. Buprenorphine with bupivacaine for intraoral nerve blocks to provide postoperative analgesia in outpatients after minor oral surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 67:2571–2576. 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore PA, Hersh EV. 2010. Local anesthetics: pharmacology and toxicity. Dent Clin North Am 54:587–599. 10.1016/j.cden.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore PA, Cuddy MA, Cooke MR, Sokolowski CJ. 2011. Periodontal ligament and intraosseous anesthetic injection techniques: alternatives to mandibular nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc 142 Suppl 3:13S–18S. 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munson ES, Tucker WK, Ausinsch B, Malagodi MH. 1975. Etidocaine, bupivacaine, and lidocaine seizure thresholds in monkeys. Anesthesiology 42:471–478. 10.1097/00000542-197504000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder LBC, Snyder CJ, Hetzel S. 2016. Effects of buprenorphine added to bupivacaine infraorbital nerve blocks on isoflurane minimum alveolar concentration using a model for acute dental/oral surgical pain in dogs. J Vet Dent 33:90–96. 10.1177/0898756416657232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steenen SA, Dubois L, Saeed P, deLange J. 2012. Ophthalmologic complications after intraoral local anesthesia: case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 113:e1–e5. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan WE. 1961. Skeleton and joints, p 43–84. In: Hartman CG, Straus WL, The anatomy of the rhesus monkey, New York (NY) Hafner Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinuela-Fernandez I, Weary DM, Flecknell P. 2011. Pain, p 64–77. In: Appleby MC, Mench JA, Olsson IAS, Hughes BO, Animal Welfare, 2nd ed Boston (MA) CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- 27.White PF. 2005. The changing role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 101 5 Suppl:S5–S22. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000177099.28914.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]