Abstract

ALDH1L1 (cytosolic 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase) is the enzyme in folate metabolism commonly downregulated in human cancers. One of the mechanisms of the enzyme downregulation is methylation of the promoter of the ALDH1L1 gene. Recent studies underscored ALDH1L1 as a candidate tumor suppressor and potential marker of aggressive cancers. In agreement with the ALDH1L1 loss in cancer, its re-expression leads to inhibition of proliferation and to apoptosis, but also affects migration and invasion of cancer cells through a specific folate-dependent mechanism involved in invasive phenotype. A growing body of literature evaluated the prognostic value of ALDH1L1 expression for cancer disease, the regulatory role of the enzyme in cellular proliferation, and associated metabolic and signaling cellular responses. Overall, there is a strong indication that the ALDH1L1 silencing provides metabolic advantage for tumor progression at a later stage when unlimited proliferation and enhanced motility become critical processes for the tumor expansion. Whether the ALDH1L1 loss is involved in tumor initiation is still an open question.

Keywords: ALDH1L1 promoter methylation, folate metabolism, tumor suppression, JNK, p53, cofilin

Introduction

Folate (vitamin B9) is an important coenzyme in numerous biochemical reactions of one-carbon transfer (this is why the network of folate-dependent reactions is called one-carbon metabolism) [1-3]. Folate-dependent reactions are involved in the biogenesis of common amino acids (serine, glycine, histidine and methionine), in the biosynthesis of purine nucleotides and thymidylate, and the utilization of formic acid (normally produced by several biochemical pathways [4]) [1-3, 5]. Overall, these reactions enable protein and nucleic acid biosynthesis, cellular methylation and the generation of NAD(P)H from the carbon atom oxidation. These key biological pathways are indispensable for cellular proliferation, and abnormalities in folate metabolism are linked to certain diseases including cancer [3, 6]. It has been known since the late 1940s that folate is important for proliferation of cancer cells as the administration of folic acid accelerated the progression of leukemia in children while the antifolate aminopterin resulted in the disease remission [3, 7]. Since that time, the antifolate methotrexate (MTX) has been used for the treatment of leukemia as well as other cancers [8], and over the years new antifolate drugs have been developed [9, 10]. MTX is a very specific inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) [11], one of the key enzymes in folate metabolism, which is responsible for the incorporation of folic acid (dietary sources) and dihydrofolate (the second product in the TMP biosynthesis pathway) into the reduced folate pool [1]. Other enzymes in folate pathways bring one-carbon groups into the folate pool, oxidize/reduce folate-bound groups, or use them in biosynthetic reactions [1].

ALDH1L1, a common folate enzyme

One of the most abundant folate enzymes is cytosolic 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (ALDH1L1; also called FDH and FTHFD) [12]. ALDH1L1 converts 10-formyl-THF to THF (tetrahydrofolate) and carbon dioxide in a NADP+-dependent reaction. This reaction clears one-carbon groups (in the form of CO2) from the cell thus limiting their flux toward folate-dependent biosynthetic reactions (Fig. 1) [13, 14]. This reaction is also important for replenishing the pool of THF [15], which is the only folate coenzyme capable of accepting one-carbon groups and thus is central to folate metabolism [16]. In agreement with such function, genome-wide association studies revealed that SNPs in the ALDH1L1 gene are associated with serine to glycine ratio in serum [17] (the product of the ALDH1L1-catalyzed reaction, THF, is the coenzyme in the reaction of the conversion of serine to glycine [1]). Furthermore, ALDH1L1 might regulate de novo purine biosynthesis [13, 18], formate degradation [5] and methylation status of the cell [14]. Another function originally proposed for this enzyme is to serve as the folate depot, though this hypothesis is primarily based on the phenomenon that the protein was purified in complex with THF [19]. ALDH1L1 also catalyzes NADPH generation coupled with the final step of carbon oxidation to CO2. Interestingly, such reaction catalyzed by the ALDH1L1 mitochondrial homolog, ALDH1L2 [20, 21], was proposed as one of the main sources of the NADPH production in mitochondria [22, 23]. While similar outcome could be expected from cytosolic ALDH1L1, which is expressed in several tissues at much higher levels than mitochondrial ALDH1L2 [20], it has not been established whether the cytosolic enzyme is also a main contributor to the intracellular NADPH pool.

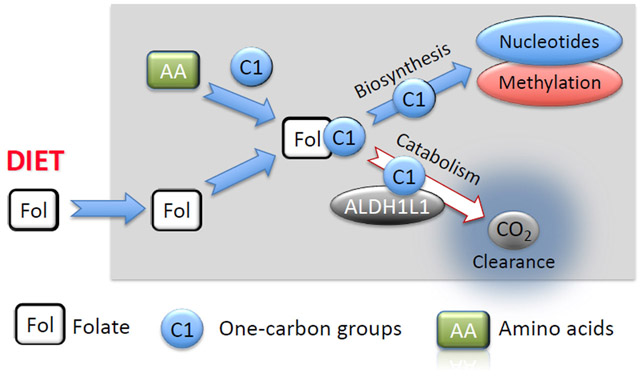

Fig. 1.

Flow of one-carbon groups through the intracellular folate pool. Folate coenzymes (Fol) transfer one-carbon groups (C1) in numerous biochemical reactions. One-carbon groups, derived from oxidation of amino acids Ser, Gly and His, enter the folate pool and are directed towards methylation processes (through methionine and SAM generation) or de novo nucleotide biosynthesis (purines and thymidylate). ALDH1L1 diverts these groups from the biosynthetic pathways clearing them as CO2, thus serving a catabolic function. Input of folate (Fol) from diet is required to support the intracellular levels of the coenzyme.

In contrast to other folate-metabolizing enzymes, ALDH1L1 (and its mitochondrial homolog ALDH1L2) belongs to the family of aldehyde dehydrogenases [12, 24, 25]. In humans, this family includes 19 genes with members of this family being involved in the conversion of numerous aldehyde substrates to corresponding acids (reviewed in [26, 27]). The ALDH1L1 gene originated from a natural fusion of three unrelated primordial genes [12, 24]. The resulting protein is a tetramer of identical 902 aa subunits; each monomeric subunit has a modular organization with three domains being structurally and functionally distinct [12]. The carboxyl-terminal core domain (residues 400-902) forms a tetramer and is a structural and functional homolog of aldehyde dehydrogenases [28-30] whereas the amino-terminal folate-binding hydrolase domain resembles methionine-tRNA formyltransferase [31, 32]. The two catalytic domains communicate via the intermediate domain, which is a structural and functional homolog of acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) [21, 33, 34] (also a part of fatty acid synthase complex [35]). As with other ACPs, the intermediate domain has the prosthetic group, 4’-phosphopantetheine (4’-PP), which functions as a flexible arm reaching catalytic centers and carrying the reaction intermediate from one center to another [33, 36]. Thus, while capable of oxidation of short-chain aldehydes to corresponding acids in vitro, ALDH1L1 is not a typical aldehyde dehydrogenase [37, 38]. This reaction does not require either the N-terminal or intermediate domains: separately expressed C-terminal domain can perform this catalysis [38]. Physiological aldehyde substrates for ALDH1L1, however, have not been identified and it is not known whether the enzyme catalyzes any aldehyde dehydrogenase reaction in vivo.

ALDH1L1 is a tightly regulated protein

ALDH1L1 is an abundant protein in several tissues with its levels reaching up to 1.2% of the total protein in liver cytosol, but the enzyme is not uniformly expressed [19, 39]. In addition to the liver, highest levels of its mRNA were detected in kidney and pancreas while the levels in several tissues including placenta, spleen, thymus, small intestine, leukocytes, testis, and ovary were undetectable [13, 20] (see also The Protein Atlas, www.proteinatlas.org, for the ALDH1L1 expression for the extended list of tissues). Interestingly, ALDH1L1 is differentially expressed in central nervous system during development: most quiescent cells in developing mouse brain are ALDH1L1 positive while proliferating cells do not express this protein [40]. The levels of ALDH1L1 were also changed in the cerebellum of the ataxin-1 protein knockout mice [41]. Curiously, levels of this protein significantly fluctuate (up to about 7-fold change) in the liver of golden-mantled ground squirrel depending on the seasonal stage [42]. In further support of highly regulated expression of this protein, its levels were decreased in the liver of cobalamin-deficient rats [43] and rats treated with the peroxisome proliferator clofibrate [44], and increased in zebrafish embryos exposed to ethanol [45]. The regulation of ALDH1L1 through the promoter methylation could also be a common cellular response to the environmental conditions. Thus, it has been reported that the prolonged exposure to isoflavone through dietary supplementation significantly reduces Aldh1l1 promoter methylation in rat mammary tissue [46]. In addition, the methylation of ALDH1L1 could be responsible for the individual variation in the protein expression. For example, higher CpG methylation in the body of the ALDH1L1 gene was significantly correlated with its lower transcript expression in normal breast tissue in women [47]. An additional mechanism of ALDH1L1 regulation, through ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, is associated with the cell cycle progression: levels of the enzyme are dropped dramatically during the transition from G1- to S-phase but are restored in resting or quiescent cells [48]. Such phenomenon is in line with the role of the enzyme as one of the master-regulators of cellular proliferation (discussed below).

Down-regulation of ALDH1L1 in cancer

The most remarkable example of ALDH1L1 regulation, however, is its silencing in malignant tumors [13]. In a study published in 2001, a microarray-based global gene expression profiling of approximately 42,000 genes in primary hepatocellular carcinomas and in liver metastases revealed that ALDH1L1 was among the 20 most underexpressed genes in each group [49]. Of note, ALDH1L1 was one of the three genes underexpressed in both groups. A 2002 report from our laboratory has shown that the ALDH1L1 expression is often lost at both mRNA and protein levels in malignant tumors of different origin [13]. In agreement with this finding, levels of this protein were undetectable by Western blot assays in several established cancer cell lines while spontaneously immortalized cells of a non-cancer origin express ALDH1L1 [13, 48]. Likewise, The Protein Atlas Database (www.proteinatlas.org) indicates a very low or undetectable levels of ALDH1L1 mRNA in most cell lines. One of the cell lines with undetectable levels of both ALDH1L1 mRNA (www.proteinatlas.org) and protein [13, 18, 50-55] was the A549 human lung carcinoma cell line, which was a common tool in our numerous studies of ALDH1L1. Contrary to these data, one study reported the presence of the ALDH1L1 protein in these cells [56]. Even more surprisingly, in this study the authors linked the ALDH1L1 activity to the increase in the NADH production (the NADH/NAD+ ratio). In fact, ALDH1L1 has a strong preponderance for NADP+ as a coenzyme with the Km for NAD+ being three order of magnitude higher [38]. In this case, it is unlikely that NADH can be produced in vivo in the ALDH1L1-catalyzed reaction and it is not clear how ALDH1L1 can be involved in the NADH production unless it is an indirect effect.

A recent analysis of gene expression profiles across 33 human cancer types using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data has shown that the expression of ALDH1L1 gene is down-regulated in early-stage cancers compared to normal tissues, and is even more strongly down-regulated in late-stage cancers [57]. This study has also identified ALDH1L1 as the gene down-regulated in high-grade malignant tumors to a higher extent than in low-grade tumors as compared to normal tissues. Of note, only three genes including ALDH1L1 were common between these two groups (late/early stage cancer and low/high grade tumors) [57]. Under-expression of the ALDH1L1 gene could be a marker of a more aggressive tumor phenotype and it was associated with poor clinical outcomes in cancer. Thus, decreased expression of ALDH1L1 was associated with aggressive subtypes of sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma [58], poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma [59], and low overall survival in neuroblastoma [60]. It should be mentioned that the association between decreased ALDH1L1 expression and malignant tumor progression could be cancer type-specific. For example, though decreased expression of ALDH1L1 was demonstrated in NSCLC [53, 61], cervical cancer [62], renal cell carcinoma [63] and peripheral cholangiocarcinoma [64], the extent of its expression in other cancers is not clear. In line with the idea that ALDH1L1 prognostic role could be cancer type-specific, SNPs in the ALDH1L1 gene were significantly associated with altered risk of breast cancer [65] and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma [66] and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [67-69] but no SNPs were associated with the risk of prostate cancer [70].

Several studies also evaluated the utility of the mRNA expression of a set of ALDH1 enzymes, including ALDH1L1, as a prognostic tool for specific cancer types [71-76]. The interest to the ALDH enzyme family in relationship to cancer was instigated by the finding that human cancer cells with increased aldehyde dehydrogenase activity have stem/progenitor properties [77, 78]. It is not clear though whether this phenomenon is relevant to ALDH1L1, which is not a typical aldehyde dehydrogenase and has no established role in the aldehyde conversion. In fact, a common Aldefluor Assay for stem cells does not detect ALDH1L1 activity [79]. It has been speculated that the enzyme decreases acetaldehyde concentrations thus enhancing DNA stability and decreasing cancer susceptibility but so far there are no experimental data to support this hypothesis [80]. The analysis of the TCGA data for the levels of mRNA for ALDHs as a cancer prognostic marker did not identify any specific pattern to predict the outcome. With regard to ALDH1L1, the data rather indicate a cancer type-dependent effect. Thus, one of these studies indicated the down-regulation of ALDH1L1 mRNA in liver cancer compared to normal tissues and better clinical outcomes in HBV-related HCC patients with high ALDH1L1 expression [75]. High expression of ALDH1L1 mRNA also correlated with better overall survival in breast cancer patients [74]. In contrast, there was no correlation between high levels of ALDH1L1 mRNA and overall survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer [76] while high transcriptional activities of ALDH1L1 predicted worsen overall survival in patients with gastric cancer [71, 73].

Overall, the consensus in the literature is that the expression of ALDH1L1 is decreased in malignant tumors compared to normal tissues. In some tumors though levels of the protein can be as high as in normal tissues. For example, in our study of non-small cell lung cancer, out of ten analyzed patient adenocarcinoma samples (matched pairs of normal and tumor tissues) four tumors lost ALDH1L1 protein, four had much lower expression than normal tissues, and two had levels similar to normal tissues [53]. The Protein Atlas Database (www.proteinatlas.org) also indicates high expression of ALDH1L1 at the protein levels in several cases. This, however, should not be interpreted as the overexpression of ALDH1L1 in cancers but rather as the lack of its down-regulation. Of note, the majority of cancers listed in this database has undetectable levels of ALDH1L1 based on histoimmunochemical staining with ALDH1L1-specific antibodies.

ALDH1L1 expression in cancer is regulated by the promoter methylation

We have demonstrated that the silencing of the ALDH1L1 gene in cancers is achieved through extensive methylation of the promoter region [53]. This gene has a CpG island with 96 CpGs spread over 1.45 kilobase pairs, covering the promoter, first exon and first intron immediately downstream of the exon [53]. In three tested cancer cell lines (A549, HCT116 and HepG2), the CpG island is heavily methylated, which explains undetectable levels of the ALDH1L1 protein in these cells [53]. Furthermore, in lung adenocarcinomas the levels of ALDH1L1 mRNA and protein correlate well with the methylation within this CpG island, with tumor samples demonstrating down-regulation of expression or even complete silencing of the gene [53]. In support of the role of methylation as the mechanism of the ALDH1L1 downregulation in cancers, the treatment of several ALDH1L1-deficient cancer cell lines with the inhibitor of DNA-methyltransferases 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine lead to the appearance of ALDH1L1 mRNA and protein in these cells [53].

Another study, which applied a microarray approach to assess methylation of a set of genes on chromosome 3 as potential biomarkers of non-small cell lung cancer, confirmed increased methylation frequency of ALDH1L1 in lung cancer [61]. Of note, in this study the frequency of the mRNA decrease was higher than the methylation frequency. Methylation of the ALDH1L1 gene was observed as well in 23% of cervical cancer samples [62] and 17% of clear cell renal cell carcinoma [63]. In the latter study, the frequency and extent of the decrease in mRNA levels was strongest for ALDH1L1 out of 22 analyzed genes and the ALDH1L1 downregulation was also more profound in tumors of more advanced stage. A recent study has investigated the extent of the ALDH1L1 CpG island methylation in 16 matched pairs from breast cancer patients with the emphasis on the assessment of methylation of each specific CpG [81]. This study indicated that the expression of ALDH1L1 (mRNA) was suppressed in all examined samples up to 200-fold with the average hypermethylation level correlating positively with the gene downregulation. This study also implies that there is no consensus between methylation of specific CpGs and the gene downregulation though several CpGs in the intron region appeared to be more often affected by methylation [81].

Metabolic advantage of the ALDH1L1 loss for cancer cells

It is well established in the literature that gene expression profiles are different between normal tissues and malignant tumors [82-84]. In this regard, several enzymes involved in folate metabolism are commonly up-regulated in cancer in agreement with increased demand for DNA biosynthesis in proliferating cells [3, 23, 85-88]. The consequences of up- or down-regulation of a specific gene for the cell can be complex and not always apparent [89]. However, the silencing of a gene in cancer is a much more rare event than just an alteration of gene expression, and could provide selective advantage for a proliferative phenotype. For example, the folate regulated enzyme GNMT (glycine-N-methyltransferase), which is often silenced in cancer, also inhibits cancer cells proliferation [90-94]. Likewise, re-expression of ALDH1L1 in cultured cancer cells produces drastic antiproliferative effects including cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [13, 18, 51, 55, 95]. The metabolic explanation of this phenomenon is based on ALDH1L1 catalysis: the enzyme competes with the de novo purine biosynthesis for the same substrate, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, which is involved in two steps of the pathway (Fig. 2) [96, 97]. Thus, this coenzyme deficiency caused by the ALDH1L1 activity compromises the ability of cancer cells to support sufficient levels of purines required for the nucleic acid biosynthesis.

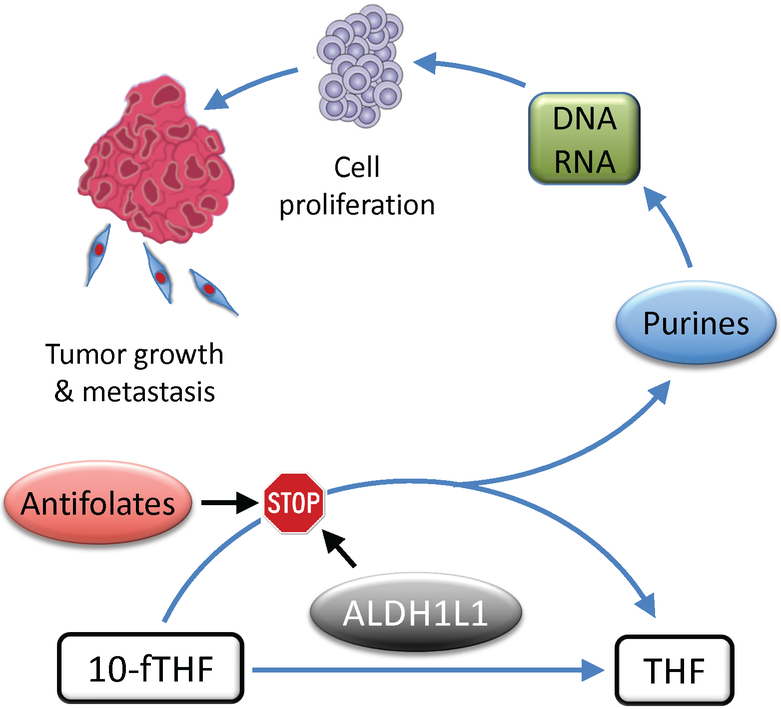

Fig. 2.

Proposed role for ALDH1L1 in proliferating cells. The ALDH1L1 substrate, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate (10-fTHF), is also a substrate in two reactions of the de novo purine biosynthesis. In the de novo purine reactions, 10-fTHF is converted to tetrahydrofolate (THF) while the formyl group becomes a part of the purine ring. In rapidly proliferating cancer cells there is an increased demand for purines to support increased biosynthesis of nucleic acids, DNA and RNAs. Therefore, antifolates targeting enzymes in the purine pathways have strong antiproliferative effects. ALDH1L1 competes with the de novo purine biosynthesis for the same substrate, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate (10-fTHF) preventing the use of the formyl group for biosynthesis. If the activity of ALDH1L1 is sufficiently high, it is likely to produce the effect similar to antifolates targeting the de novo pathway. Overall, high ALDH1L1 activity is expected to inhibit cellular proliferation, an essential component of the malignant tumor growth.

Cancer cells have accelerated biosynthesis of “building blocks” such as nucleotides [98]. It has been suggested that the strong preponderance of cancer cells for aerobic glycolysis is not energy-driven but rather due to increased requirement for production of pentose phosphate, a structural component of nucleotides [98, 99]. Of note, upregulation of nucleotide biosynthesis is often observed across tumors [84]. Therefore, cancer cells are particularly susceptible to compromised folate metabolism [100]. In this regard, the effect of ALDH1L1 would be similar to the effect of antifolate drugs targeting folate-dependent enzyme in the de novo purine pathway (Fig. 2) [9, 10, 101]. In agreement with such mechanism, we have demonstrated that re-expression of ALDH1L1 in ALDH1L1-deficient cancer cells indeed leads to a dramatic drop in levels of 10-formyl-THF, ATP and GTP [18, 54]. The rescue of cells from the cytotoxic effects of ALDH1L1 by high doses of hypoxanthine [13], which is converted to purine nucleotides through the salvage pathways thus bypassing the de novo pathway [102], further supports the role of ALDH1L1 in the regulation of the de novo purine biosynthesis. High levels of reduced folate leucovorin (5-formyltetrahydrofolate or folinic acid) can also partially rescue ALDH1L1 antiproliferative effects, apparently through the constant supply of other reduced folate pools and overloading the catalytic capacity of ALDH1L1. This can be a mechanism for cancer cells to develop resistance against ALDH1L1 and could also explain high levels of this protein in some tumors [54].

Signaling pathways mediating ALDH1L1-dependent cellular response

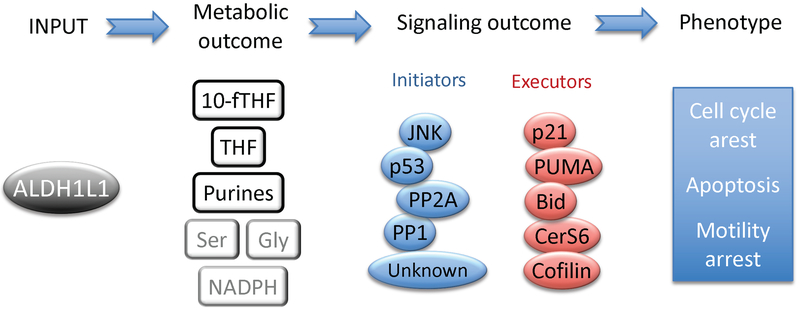

The effect of ALDH1L1 on intracellular folate and purine pools is translated to specific signaling pathways (Fig. 3). Thus, we have demonstrated that ALDH1L1 expression in cancer cells activates the p53 tumor suppressor [18]. In this regard, a reversible activation of p53 by the ribonucleotide depletion was reported although precise molecular mechanisms of this process are not well understood [103]. Furthermore, antifolates directly targeting the de novo purine biosynthesis evoke antiproliferative effects in cancer cells independent of the p53 status [104-106]. In contrast to such antifolates, the signaling mechanisms underlying the ALDH1L1 antiproliferative effect could involve p53-dependent pathways or could be p53-independent. For example, the p53 activation by ALDH1L1 in A549 cells proceeds through phosphorylation of p53 at a specific residue, Ser6 by JNK1 and JNK2 (c-Jun activated protein kinases) [51]. Of note, a similar mechanism of the p53 activation was seen in A549 cells treated with a potent anticancer drug aziridinylquinone [107]. It appears that the activation of JNKs is a common cellular mechanism in response to ALDH1L1, although the downstream JNK targets can be different depending on the cell type. Hence, in the p53-deficient prostate cancer cell line PC-3, ALDH1L1 expression activates phosphorylation of the canonical JNK target c-Jun [95] as well as the pro-apoptotic protein Bid [108]. In the latter case, phosphorylation of Bid by JNK1/2 at Thr59 prevents its cleavage by caspase-3 leading to dramatic Bid accumulation and activation of apoptosis [108]. The activation of Bid in response to ALDH1L1 takes place in p53-deficient as well as p53-proficient cells [108], an indication that the ALDH1L1-mediated signaling pathways are not mutually exclusive and that their combination is likely to define the overall cellular response.

Fig. 3.

Metabolic and signaling pathways responding to ALDH1L1 elevation in cancer cells. Expression of ALDH1L1 in ALDH1L1-deficient cancer cells (input) decreases 10-fTHF and purines and increases THF (metabolic outcome; the effect on Ser, Gly and NADPH is likely but was not directly measured). Signaling molecules activated in response to ALDH1L1 can be immediately downstream of ALDH1L1 (initiators) or can be downstream targets of initiators (executors). Resulting cellular response (phenotype) includes cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and inhibitory effect on cellular motility.

Bid phosphorylation is induced in response to ALDH1L1 independent of p53, but several other responding signaling molecules, including PUMA and p21, are down-stream targets of p53 [18, 109]. Depending on the cell type, the activation of p21 upon ALDH1L1-induced metabolic stress leads to either G1 or G2 cell cycle arrest [109], which is likely a pro-survival response. Indeed, the silencing of p21 accelerated ALDH1L1-dependent apoptosis [109]. The elevation of PUMA in turn is the main signal for ALDH1L1-dependent apoptosis in p53-positive cells since PUMA silencing promotes survival of ALDH1L1-transfected cancer cells [109]. We have also identified another target responding to ALDH1L1, ceramide synthase 6 (CerS6) [110]. This enzyme is one of six ceramide synthases, which make the wide variety of sphingolipid ceramides in the cell [111-113]. Importantly, the product of the CerS6 catalysis, C16-ceramide, is a signaling molecule with a pro-apoptotic effect [114]. In agreement with the role of CerS6 and the ceramide, activation of CerS6 by ALDH1L1 observed in our studies, with subsequent C16-ceramide elevation, was a strong apoptotic stimulus in cancer cells [110]. Curiously, the effect of ALDH1L1 on CerS6 and C16-ceramide levels was strictly p53-dependent [110]. The explanation of this phenomenon was found in the follow-up study, which demonstrated that the CerS6 gene is a direct transcriptional target of p53 [115]. To add up to this story, the p53/CerS6 couple works in a feed-back type self-enhancing mode: while p53 transcriptionally activates the CerS6 gene, CerS6-produced C16-ceramide in turn activates p53 by releasing it from the MDM2-driven proteasomal degradation [116]. Thus, the induction of this pathway could be a rapid self-destructing fate for cancer cells.

ALDH1L1 targets in signaling pathways are not limited by those discussed above. Thus, ALDH1L1 causes strong dephosphorylation of the actin-depolymerazing factor cofilin by the serine/threonine protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A [52]. Cofilin is one of the main regulators of actin-dependent cellular motility and plays an important role in migration and invasion of cancer cells [117]. ALDH1L1-induced cofilin dephosphorylation leads to the inhibition of actin dynamics and formation of actin stress fibers thus decreasing the ability of cells to migrate. These findings indicate that the loss of ALDH1L1 perhaps provides selective advantage for metastasizing tumors, which might explain stronger down-regulation of ALDH1L1 mRNA in metastases compared to primary tumors [49]. Of note, though the ALDH1L1-dependent pathways regulating cellular motility are different from pathways regulating proliferation, in both cases the cellular response is associated with the ALDH1L1 effect on cellular folate metabolism. In support of this notion, enhanced folate supplementation can partially rescue effects of ALDH1L1 on activation of CerS6 and cofilin dephosphorylation while folate withdrawal produces effects similar to ALDH1L1 expression [52, 110]. The effect of ALDH1L1 on cellular migration and invasion through the regulation of folate metabolism also implies that re-activation of the enzyme in malignant tumors could be a therapeutic goal to inhibit metastasis. Though the influence of dietary folate on metastasis is not well understood, we have previously demonstrated that feeding mice folate-restricted diet dramatically decreases metastasis and increases survival [50].

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous recent studies have established that ALDH1L1 expression is often strongly decreased in human cancers, and in many cases the gene is completely silenced. Though based on these data this gene has been proposed as putative tumor suppressor [13, 53, 58, 62, 63], it is still not clear whether the ALDH1L1 loss contributes to tumorigenesis of whether its loss provides selective advantage for aggressive or late-stage malignant tumors. ALDH1L1 might also have a role in metastasis but underlying molecular mechanisms await further investigation. Nevertheless, there is significant body of evidence indicating that ALDH1L1 is a key regulator of proliferation. Interestingly, another one-carbon metabolism gene, SHMT2 (mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyltransferase), was identified as a gene necessary for tumor cell survival but insufficient for transformation [118]. On the other hand, the folate regulated enzyme GNMT appears to be involved in the regulation of tumorigenesis as well as proliferation [93, 94, 119-121]. It is likely that the ALDH1L1 silencing is not required for tumor initiation but is beneficial for tumor progression at a later stage when unlimited proliferation and enhanced motility become critical processes for the tumor expansion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SAK was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants DK054388 and CA095030; NIK was supported the National Institutes of Health Grants CA193782. The authors would like to thank Dr. David Horita for helpful discussions and carefully reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- ALDH1L1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1

- MTX

methotrexate

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Tibbetts AS, Appling DR, Compartmentalization of Mammalian folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism, Annu Rev Nutr, 30 (2010) 57–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fox JT, Stover PJ, Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism, Vitam Horm, 79 (2008) 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ducker GS, Rabinowitz JD, One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease, Cell Metab, 25 (2017) 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Casteels M, Sniekers M, Fraccascia P, Mannaerts GP, Van Veldhoven PP, The role of 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase, a thiamin pyrophosphate-dependent enzyme, in the peroxisomal metabolism of 3-methyl-branched fatty acids and 2-hydroxy straight-chain fatty acids, Biochem Soc Trans, 35 (2007) 876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brosnan ME, MacMillan L, Stevens JR, Brosnan JT, Division of labour: how does folate metabolism partition between one-carbon metabolism and amino acid oxidation?, Biochem J, 472 (2015) 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stover PJ, Physiology of folate and vitamin B12 in health and disease, Nutr Rev, 62 (2004) S3–12; discussion S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Strickland KC, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Molecular mechanisms underlying the potentially adverse effects of folate, Clin Chem Lab Med, 51 (2013) 607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bertino JR, Karnofsky memorial lecture. Ode to methotrexate, J Clin Oncol, 11 (1993) 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goldman ID, Chattopadhyay S, Zhao R, Moran R, The antifolates: evolution, new agents in the clinic, and how targeting delivery via specific membrane transporters is driving the development of a next generation of folate analogs, Curr Opin Investig Drugs, 11 (2010) 1409–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Visentin M, Zhao R, Goldman ID, The antifolates, Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 26 (2012) 629–648, ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bertino JR, Cancer research: from folate antagonism to molecular targets, Best Pract Res Clin Haematol, 22 (2009) 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krupenko SA, FDH: an aldehyde dehydrogenase fusion enzyme in folate metabolism, Chem. Biol. Interact, 178 (2009) 84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Krupenko SA, Oleinik NV, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, one of the major folate enzymes, is down-regulated in tumor tissues and possesses suppressor effects on cancer cells, Cell Growth Differ, 13 (2002) 227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Anguera MC, Field MS, Perry C, Ghandour H, Chiang EP, Selhub J, Shane B, Stover PJ, Regulation of Folate-mediated One-carbon Metabolism by 10-Formyltetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase, J Biol Chem, 281 (2006) 18335–18342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Champion KM, Cook RJ, Tollaksen SL, Giometti CS, Identification of a heritable deficiency of the folate-dependent enzyme 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase in mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 91 (1994) 11338–11342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wagner C, Biochemical role of folate in cellular metabolism, in: Bailey LB (Ed.) Folate in Health and Disease, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, 1995, pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dharuri H, Henneman P, Demirkan A, van Klinken JB, Mook-Kanamori DO, Wang-Sattler R, Gieger C, Adamski J, Hettne K, Roos M, Suhre K, Van Duijn CM, Consortia E, van Dijk KW, t Hoen PA, Automated workflow-based exploitation of pathway databases provides new insights into genetic associations of metabolite profiles, BMC Genomics, 14 (2013) 865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Priest DG, Krupenko SA, Cancer cells activate p53 in response to 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase expression, Biochem J, 391 (2005) 503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cook RJ, Wagner C, Purification and partial characterization of rat liver folate binding protein: cytosol I, Biochemistry, 21 (1982) 4427–4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Krupenko NI, Dubard ME, Strickland KC, Moxley KM, Oleinik NV, Krupenko SA, ALDH1L2 is the mitochondrial homolog of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, J. Biol. Chem, 285 (2010) 23056–23063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Strickland KC, Krupenko NI, Dubard ME, Hu CJ, Tsybovsky Y, Krupenko SA, Enzymatic properties of ALDH1L2, a mitochondrial 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, Chem. Biol. Interact, 191 (2011) 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fan J, Ye J, Kamphorst JJ, Shlomi T, Thompson CB, Rabinowitz JD, Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production, Nature, 510 (2014) 298–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ducker GS, Chen L, Morscher RJ, Ghergurovich JM, Esposito M, Teng X, Kang Y, Rabinowitz JD, Reversal of Cytosolic One-Carbon Flux Compensates for Loss of the Mitochondrial Folate Pathway, Cell Metab, 23 (2016) 1140–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Krupenko NI, Holmes RS, Tsybovsky Y, Krupenko SA, Aldehyde dehydrogenase homologous folate enzymes: Evolutionary switch between cytoplasmic and mitochondrial localization, Chem Biol Interact, 234 (2015) 12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Strickland KC, Holmes RS, Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Phylogeny and evolution of aldehyde dehydrogenase-homologous folate enzymes, Chem. Biol. Interact, 191 (2011) 122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Marchitti SA, Brocker C, Stagos D, Vasiliou V, Non-P450 aldehyde oxidizing enzymes: the aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily, Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, 4 (2008) 697–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vasiliou V, Thompson DC, Smith C, Fujita M, Chen Y, Aldehyde dehydrogenases: from eye crystallins to metabolic disease and cancer stem cells, Chem Biol Interact, 202 (2013) 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tsybovsky Y, Donato H, Krupenko NI, Davies C, Krupenko SA, Crystal structures of the carboxyl terminal domain of rat 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase: implications for the catalytic mechanism of aldehyde dehydrogenases, Biochemistry, 46 (2007) 2917–2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tsybovsky Y, Krupenko SA, Conserved Catalytic Residues of the ALDH1L1 Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Domain Control Binding and Discharging of the Coenzyme, J. Biol. Chem, 286 (2011) 23357–23367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tsybovsky Y, Malakhau Y, Strickland KC, Krupenko SA, The mechanism of discrimination between oxidized and reduced coenzyme in the aldehyde dehydrogenase domain of Aldh1l1, Chem Biol Interact, 202 (2013) 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chumanevich AA, Krupenko SA, Davies C, The crystal structure of the hydrolase domain of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase: mechanism of hydrolysis and its interplay with the dehydrogenase domain, J Biol Chem, 279 (2004) 14355–14364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Reuland SN, Vlasov AP, Krupenko SA, Modular organization of FDH: Exploring the basis of hydrolase catalysis, Protein Sci, 15 (2006) 1076–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Donato H, Krupenko NI, Tsybovsky Y, Krupenko SA, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase requires a 4'-phosphopantetheine prosthetic group for catalysis, J Biol Chem, 282 (2007) 34159–34166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Strickland KC, Hoeferlin LA, Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Acyl carrier protein-specific 4'-phosphopantetheinyl transferase activates 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, J. Biol. Chem, 285 (2010) 1627–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Finzel K, Lee DJ, Burkart MD, Using modern tools to probe the structure-function relationship of fatty acid synthases, Chembiochem, 16 (2015) 528–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Horita DA, Krupenko SA, Modeling of interactions between functional domains of ALDH1L1, Chem Biol Interact, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cook RJ, Lloyd RS, Wagner C, Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones for rat liver 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, J Biol Chem, 266 (1991) 4965–4973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Krupenko SA, Wagner C, Cook RJ, Expression, purification, and properties of the aldehyde dehydrogenase homologous carboxyl-terminal domain of rat 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, J. Biol. Chem, 272 (1997) 10266–10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kisliuk RL, Folate biochemistry in relation to antifolate selectivity, in: Jackman AL (Ed.) Antifolate drugs in cancer therapy, Humana Press, Totowa, New Jersey, 1999, pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Anthony TE, Heintz N, The folate metabolic enzyme ALDH1L1 is restricted to the midline of the early CNS, suggesting a role in human neural tube defects, J Comp Neurol, 500 (2007) 368–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sanchez I, Balague E, Matilla-Duenas A, Ataxin-1 regulates the cerebellar bioenergetics proteome through the GSK3beta-mTOR pathway which is altered in Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), Hum Mol Genet, 25 (2016) 4021–4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Epperson LE, Dahl TA, Martin SL, Quantitative analysis of liver protein expression during hibernation in the golden-mantled ground squirrel, Mol Cell Proteomics, 3 (2004) 920–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].MacMillan L, Tingley G, Young SK, Clow KA, Randell EW, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT, Cobalamin Deficiency Results in Increased Production of Formate Secondary to Decreased Mitochondrial Oxidation of One-Carbon Units in Rats, J Nutr, 148 (2018) 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Leonard JF, Courcol M, Mariet C, Charbonnier A, Boitier E, Duchesne M, Parker F, Genet B, Supatto F, Roberts R, Gautier JC, Proteomic characterization of the effects of clofibrate on protein expression in rat liver, Proteomics, 6 (2006) 1915–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hsiao TH, Lin CJ, Chung YS, Lee GH, Kao TT, Chang WN, Chen BH, Hung JJ, Fu TF, Ethanol-induced upregulation of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase helps relieve ethanol-induced oxidative stress, Mol Cell Biol, 34 (2014) 498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blei T, Soukup ST, Schmalbach K, Pudenz M, Moller FJ, Egert B, Wortz N, Kurrat A, Muller D, Vollmer G, Gerhauser C, Lehmann L, Kulling SE, Diel P, Dose-dependent effects of isoflavone exposure during early lifetime on the rat mammary gland: Studies on estrogen sensitivity, isoflavone metabolism, and DNA methylation, Mol Nutr Food Res, 59 (2015) 270–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Song MA, Brasky TM, Marian C, Weng DY, Taslim C, Llanos AA, Dumitrescu RG, Liu Z, Mason JB, Spear SL, Kallakury BV, Freudenheim JL, Shields PG, Genetic variation in one-carbon metabolism in relation to genome-wide DNA methylation in breast tissue from heathy women, Carcinogenesis, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Khan QA, Pediaditakis P, Malakhau Y, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Ashkavand Z, Sereda V, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, CHIP E3 ligase mediates proteasomal degradation of the proliferation regulatory protein ALDH1L1 during the transition of NIH3T3 fibroblasts from G0/G1 to S-phase, PLoS One, in press, available July 6, 2018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tackels-Horne D, Goodman MD, Williams AJ, Wilson DJ, Eskandari T, Vogt LM, Boland JF, Scherf U, Vockley JG, Identification of differentially expressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver tumors by oligonucleotide expression profiling, Cancer, 92 (2001) 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Oleinik NV, Helke KL, Kistner-Griffin E, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Rho GTPases RhoA and Rac1 Mediate Effects of Dietary Folate on Metastatic Potential of A549 Cancer Cells through the Control of Cofilin Phosphorylation, J Biol Chem, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Cooperation between JNK1 and JNK2 in activation of p53 apoptotic pathway, Oncogene, 26 (2007) 7222–7230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, ALDH1L1 inhibits cell motility via dephosphorylation of cofilin by PP1 and PP2A, Oncogene, 29 (2010) 6233–6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Epigenetic silencing of ALDH1L1, a metabolic regulator of cellular proliferation, in cancers, Genes and Cancer, 2 (2011) 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Reuland SN, Krupenko SA, Leucovorin-induced resistance against FDH growth suppressor effects occurs through DHFR up-regulation, Biochem Pharmacol, 72 (2006) 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Oleinik NV, Krupenko SA, Ectopic expression of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase in a549 cells induces g(1) cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, Mol Cancer Res, 1 (2003) 577–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kang JH, Lee SH, Lee JS, Nam B, Seong TW, Son J, Jang H, Hong KM, Lee C, Kim SY, Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition combined with phenformin treatment reversed NSCLC through ATP depletion, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 49397–49410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li M, Sun Q, Wang X, Transcriptional landscape of human cancers, Oncotarget, 8 (2017) 34534–34551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rodriguez FJ, Giannini C, Asmann YW, Sharma MK, Perry A, Tibbetts KM, Jenkins RB, Scheithauer BW, Anant S, Jenkins S, Eberhart CG, Sarkaria JN, Gutmann DH, Gene expression profiling of NF-1-associated and sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma identifies aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) as an underexpressed candidate biomarker in aggressive subtypes, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 67 (2008) 1194–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chen XQ, He JR, Wang HY, Decreased expression of ALDH1L1 is associated with a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma, Med Oncol, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hartomo TB, Van Huyen Pham T, Yamamoto N, Hirase S, Hasegawa D, Kosaka Y, Matsuo M, Hayakawa A, Takeshima Y, Iijima K, Nishio H, Nishimura N, Involvement of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A2 in the regulation of cancer stem cell properties in neuroblastoma, Int J Oncol, 46 (2015) 1089–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Dmitriev AA, Kashuba VI, Haraldson K, Senchenko VN, Pavlova TV, Kudryavtseva AV, Anedchenko EA, Krasnov GS, Pronina IV, Loginov VI, Kondratieva TT, Kazubskaya TP, Braga EA, Yenamandra SP, Ignatjev I, Ernberg I, Klein G, Lerman MI, Zabarovsky ER, Genetic and epigenetic analysis of non-small cell lung cancer with NotI-microarrays, Epigenetics, 7 (2012) 502–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Senchenko VN, Kisseljova NP, Ivanova TA, Dmitriev AA, Krasnov GS, Kudryavtseva AV, Panasenko GV, Tsitrin EB, Lerman MI, Kisseljov FL, Kashuba VI, Zabarovsky ER, Novel tumor suppressor candidates on chromosome 3 revealed by NotI-microarrays in cervical cancer, Epigenetics, 8 (2013) 409–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Dmitriev AA, Rudenko EE, Kudryavtseva AV, Krasnov GS, Gordiyuk VV, Melnikova NV, Stakhovsky EO, Kononenko OA, Pavlova LS, Kondratieva TT, Alekseev BY, Braga EA, Senchenko VN, Kashuba VI, Epigenetic alterations of chromosome 3 revealed by NotI-microarrays in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, Biomed Res Int, 2014 (2014) 735292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Darby IA, Vuillier-Devillers K, Pinault E, Sarrazy V, Lepreux S, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P, Desmouliere A, Proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in peripheral cholangiocarcinoma, Cancer Microenviron, 4 (2010) 73–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Pavluck AL, Talbot JT, Feigelson HS, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Association of polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism genes and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 16 (2007) 1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhang H, Liu C, Han YC, Ma Z, Zhang H, Ma Y, Liu X, Genetic variations in the one-carbon metabolism pathway genes and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a case-control study, Tumour Biol, 36 (2015) 997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lim U, Wang SS, Hartge P, Cozen W, Kelemen LE, Chanock S, Davis S, Blair A, Schenk M, Rothman N, Lan Q, Gene-nutrient interactions among determinants of folate and one-carbon metabolism on the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: NCI-SEER case-control study, Blood, 109 (2007) 3050–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee KM, Lan Q, Kricker A, Purdue MP, Grulich AE, Vajdic CM, Turner J, Whitby D, Kang D, Chanock S, Rothman N, Armstrong BK, One-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Australia, Hum Genet, 122 (2007) 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Li Q, Lan Q, Zhang Y, Bassig BA, Holford TR, Leaderer B, Boyle P, Zhu Y, Qin Q, Chanock S, Rothman N, Zheng T, Role of one-carbon metabolizing pathway genes and gene-nutrient interaction in the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Cancer Causes Control, 24 (2013) 1875–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Stevens VL, Rodriguez C, Sun J, Talbot JT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, No association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism genes with prostate cancer risk, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 17 (2008) 3612–3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Li K, Guo X, Wang Z, Li X, Bu Y, Bai X, Zheng L, Huang Y, The prognostic roles of ALDH1 isoenzymes in gastric cancer, Onco Targets Ther, 9 (2016) 3405–3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ma YM, Zhao S, Prognostic values of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 isoenzymes in ovarian cancer, Onco Targets Ther, 9 (2016) 1981–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Shen JX, Liu J, Li GW, Huang YT, Wu HT, Mining distinct aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) isoenzymes in gastric cancer, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 25340–25349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wu S, Xue W, Huang X, Yu X, Luo M, Huang Y, Liu Y, Bi Z, Qiu X, Bai S, Distinct prognostic values of ALDH1 isoenzymes in breast cancer, Tumour Biol, 36 (2015) 2421–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Yang CK, Wang XK, Liao XW, Han CY, Yu TD, Qin W, Zhu GZ, Su H, Yu L, Liu XG, Lu SC, Chen ZW, Liu Z, Huang KT, Liu ZT, Liang Y, Huang JL, Xiao KY, Peng MH, Winkle CA, O'Brien SJ, Peng T, Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) isoform expression and potential clinical implications in hepatocellular carcinoma, PLoS One, 12 (2017) e0182208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].You Q, Guo H, Xu D, Distinct prognostic values and potential drug targets of ALDH1 isoenzymes in non-small-cell lung cancer, Drug Des Devel Ther, 9 (2015) 5087–5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S, Schott A, Hayes D, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS, Dontu G, ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome, Cell Stem Cell, 1 (2007) 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, Todd NW, Deepak J, Xing L, Wang H, Liu Z, Su Y, Stass SA, Katz RL, Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer, Mol Cancer Res, 7 (2009) 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Morgan CA, Parajuli B, Buchman CD, Dria K, Hurley TD, N,N-diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB) as a substrate and mechanism-based inhibitor for human ALDH isoenzymes, Chem Biol Interact, 234 (2015) 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Hwang PH, Lian L, Zavras AI, Alcohol intake and folate antagonism via CYP2E1 and ALDH1: effects on oral carcinogenesis, Med Hypotheses, 78 (2012) 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Beniaminov AD, Puzanov GA, Krasnov GS, Kaluzhny DN, Kazubskaya TP, Braga EA, Kudryavtseva AV, Melnikova NV, Dmitriev AA, Deep Sequencing Revealed a CpG Methylation Pattern Associated With ALDH1L1 Suppression in Breast Cancer, Front Genet, 9 (2018) 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, Roberts C, Linsley PS, Bernards R, Friend SH, Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer, Nature, 415 (2002) 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ramaswamy S, Tamayo P, Rifkin R, Mukherjee S, Yeang CH, Angelo M, Ladd C, Reich M, Latulippe E, Mesirov JP, Poggio T, Gerald W, Loda M, Lander ES, Golub TR, Multiclass cancer diagnosis using tumor gene expression signatures, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98 (2001) 15149–15154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hu J, Locasale JW, Bielas JH, O'Sullivan J, Sheahan K, Cantley LC, Vander Heiden MG, Vitkup D, Heterogeneity of tumor-induced gene expression changes in the human metabolic network, Nat Biotechnol, 31 (2013) 522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Jain M, Nilsson R, Sharma S, Madhusudhan N, Kitami T, Souza AL, Kafri R, Kirschner MW, Clish CB, Mootha VK, Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation, Science, 336 (2012) 1040–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Nilsson R, Jain M, Madhusudhan N, Sheppard NG, Strittmatter L, Kampf C, Huang J, Asplund A, Mootha VK, Metabolic enzyme expression highlights a key role for MTHFD2 and the mitochondrial folate pathway in cancer, Nat Commun, 5 (2014) 3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wu J, Li S, Ma R, Sharma A, Bai S, Dun B, Cao H, Jing C, She J, Feng J, Tumor profiling of co-regulated receptor tyrosine kinase and chemoresistant genes reveal different targeting options for lung and gastroesophageal cancers, Am J Transl Res, 8 (2016) 5729–5740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ryu B, Kim DS, Deluca AM, Alani RM, Comprehensive expression profiling of tumor cell lines identifies molecular signatures of melanoma progression, PLoS One, 2 (2007) e594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP, Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102 (2005) 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Chen YM, Shiu JY, Tzeng SJ, Shih LS, Chen YJ, Lui WY, Chen PH, Characterization of glycine-N-methyltransferase-gene expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma, Int J Cancer, 75 (1998) 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Huang YC, Lee CM, Chen M, Chung MY, Chang YH, Huang WJ, Ho DM, Pan CC, Wu TT, Yang S, Lin MW, Hsieh JT, Chen YM, Haplotypes, loss of heterozygosity, and expression levels of glycine N-methyltransferase in prostate cancer, Clin Cancer Res, 13 (2007) 1412–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Goonesekere NCW, Andersen W, Smith A, Wang X, Identification of genes highly downregulated in pancreatic cancer through a meta-analysis of microarray datasets: implications for discovery of novel tumor-suppressor genes and therapeutic targets, J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 144 (2018) 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].DebRoy S, Kramarenko II, Ghose S, Oleinik NV, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, A novel tumor suppressor function of glycine N-methyltransferase is independent of its catalytic activity but requires nuclear localization, PLoS One, 8 (2013) e70062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Yen CH, Lu YC, Li CH, Lee CM, Chen CY, Cheng MY, Huang SF, Chen KF, Cheng AL, Liao LY, Lee YH, Chen YM, Functional characterization of glycine N-methyltransferase and its interactive protein DEPDC6/DEPTOR in hepatocellular carcinoma, Mol Med, 18 (2012) 286–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ghose S, Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase-induced c-Jun-NH2-kinase pathways diverge at the c-Jun-NH2-kinase substrate level in cells with different p53 status, Mol Cancer Res, 7 (2009) 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Pedley AM, Benkovic SJ, A New View into the Regulation of Purine Metabolism: The Purinosome, Trends Biochem Sci, 42 (2017) 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Baggott JE, Tamura T, Folate-Dependent Purine Nucleotide Biosynthesis in Humans, Adv Nutr, 6 (2015) 564–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Tong X, Zhao F, Thompson CB, The molecular determinants of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in cancer cells, Curr Opin Genet Dev, 19 (2009) 32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation, Science, 324 (2009) 1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Newman AC, Maddocks ODK, One-carbon metabolism in cancer, Br J Cancer, 116 (2017) 1499–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Beardsley GP, Moroson BA, Taylor EC, Moran RG, A new folate antimetabolite, 5,10-dideaza-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate is a potent inhibitor of de novo purine synthesis, J Biol Chem, 264 (1989) 328–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Brault JJ, Terjung RL, Purine salvage to adenine nucleotides in different skeletal muscle fiber types, J Appl Physiol (1985), 91 (2001) 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Linke SP, Clarkin KC, Di Leonardo A, Tsou A, Wahl GM, A reversible, p53-dependent G0/G1 cell cycle arrest induced by ribonucleotide depletion in the absence of detectable DNA damage, Genes Dev, 10 (1996) 934–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Bronder JL, Moran RG, Antifolates targeting purine synthesis allow entry of tumor cells into S phase regardless of p53 function, Cancer Res, 62 (2002) 5236–5241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Bronder JL, Moran RG, A defect in the p53 response pathway induced by de novo purine synthesis inhibition, J Biol Chem, 278 (2003) 48861–48871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Fekry B, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, Ceramide Synthase 6 Is a Novel Target of Methotrexate Mediating Its Antiproliferative Effect in a p53-Dependent Manner, PLoS One, 11 (2016) e0146618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Stulpinas A, Imbrasaite A, Krestnikova N, Sarlauskas J, Cenas N, Kalvelyte AV, Study of Bioreductive Anticancer Agent RH-1-Induced Signals Leading the Wild-Type p53-Bearing Lung Cancer A549 Cells to Apoptosis, Chem Res Toxicol, 29 (2016) 26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Prakasam A, Ghose S, Oleinik NV, Bethard JR, Peterson YK, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, JNK1/2 regulate Bid by direct phosphorylation at Thr59 in response to ALDH1L1, Cell Death Dis, 5 (2014) e1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Hoeferlin LA, Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Activation of p21-Dependent G1/G2 Arrest in the Absence of DNA Damage as an Antiapoptotic Response to Metabolic Stress, Genes Cancer, 2 (2011) 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Hoeferlin LA, Fekry B, Ogretmen B, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, Folate stress induces apoptosis via p53-dependent de novo ceramide synthesis and up-regulation of ceramide synthase 6, J Biol Chem, 288 (2013) 12880–12890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Holmes RS, Barron KA, Krupenko NI, Ceramide Synthase 6: Comparative Analysis, Phylogeny and Evolution, Biomolecules, 8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Mullen TD, Hannun YA, Obeid LM, Ceramide synthases at the centre of sphingolipid metabolism and biology, Biochem J, 441 (2012) 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Levy M, Futerman AH, Mammalian ceramide synthases, IU BMB Life, 62 (2010) 347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Renert AF, Leprince P, Dieu M, Renaut J, Raes M, Bours V, Chapelle JP, Piette J, Merville MP, Fillet M, The proapoptotic C16-ceramide-dependent pathway requires the death-promoting factor Btf in colon adenocarcinoma cells, J Proteome Res, 8 (2009) 4810–4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Fekry B, Jeffries KA, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Ogretmen B, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, CerS6 Is a Novel Transcriptional Target of p53 Protein Activated by Non-genotoxic Stress, J Biol Chem, 291 (2016) 16586–16596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Fekry B, Jeffries KA, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Szulc ZM, Knagge KJ, Kirchner DR, Horita DA, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI, C16-ceramide is a natural regulatory ligand of p53 in cellular stress response, Nat Commun, 9 (2018) 4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Wang W, Eddy R, Condeelis J, The cofilin pathway in breast cancer invasion and metastasis, Nat Rev Cancer, 7 (2007) 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Lee GY, Haverty PM, Li L, Kljavin NM, Bourgon R, Lee J, Stern H, Modrusan Z, Seshagiri S, Zhang Z, Davis D, Stokoe D, Settleman J, de Sauvage FJ, Neve RM, Comparative oncogenomics identifies PSMB4 and SHMT2 as potential cancer driver genes, Cancer Res, 74 (2014) 3114–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Frau M, Simile MM, Tomasi ML, Demartis MI, Daino L, Seddaiu MA, Brozzetti S, Feo CF, Massarelli G, Solinas G, Feo F, Lee JS, Pascale RM, An expression signature of phenotypic resistance to hepatocellular carcinoma identified by cross-species gene expression analysis, Cell Oncol (Dordr), 35 (2012) 163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Martinez-Chantar ML, Vazquez-Chantada M, Ariz U, Martinez N, Varela M, Luka Z, Capdevila A, Rodriguez J, Aransay AM, Matthiesen R, Yang H, Calvisi DF, Esteller M, Fraga M, Lu SC, Wagner C, Mato JM, Loss of the glycine N-methyltransferase gene leads to steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice, Hepatology, 47 (2008) 1191–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Liao YJ, Liu SP, Lee CM, Yen CH, Chuang PC, Chen CY, Tsai TF, Huang SF, Lee YH, Chen YM, Characterization of a glycine N-methyltransferase gene knockout mouse model for hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications of the gender disparity in liver cancer susceptibility, Int J Cancer, 124 (2009) 816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.