Abstract

Icetexane diterpenoids are richly complex polycyclic natural products that have been described with a variety of biological activities. We report here a general synthetic approach toward the 6–7-6 tricyclic core structure of these interesting synthetic targets based on a two-step enolate alkylation and ring-closing metathesis reaction sequence.

Keywords: Icetexane, Alkylation, Metathesis, Synthesis design, Antitumor agents

Introduction

Icetexane diterpenoids are complex natural products that have been isolated from a variety of plant life known to several systems of traditional medicine in Asia.[1] Teas and other preparations derived from several genera of icetexane producing plants have been used for their beneficial antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects, as well as for the treatment of hepatic disorders, hypertonia, and other ailments.[2] Icetexanes are generally isolated as 6–7-6 tricyclic system, with geminal methyl substitution at C4, and an isopropyl unit at C13, with an aromatic ring comprising the C8–C14 ring and various units of unsaturation and oxidation in the tricyclic system.[3] These decorated tricyclic diterpenoids have been described with a variety of medicinally significant biological activities, however a particularly interesting member of this family is premnalatifolin A (1), a novel dimeric diterpene isolated from Premna latifolia Roxb in 2011.[4] Premnalatifolin A (1) was reported to have cytotoxic activity against seven human cancer cell lines in vitro including colon (HT-29), skin (A-431), liver (Hep-G2), prostate (PC-3), lung (A-549), kidney (ACHN), and breast cancer (MCF-7). The most potent activity was exhibited against breast cancer (MCF-7) with an IC50 of 1.11 ± 0.23 μg/mL (1.77 μM), which compared favorably with doxorubicin (Adriamycin),[5] one of the current standards of care and the positive control during that study (IC50 = 2.01 ± 0.03 μg/mL, 3.68 μM).

Results and Discussion

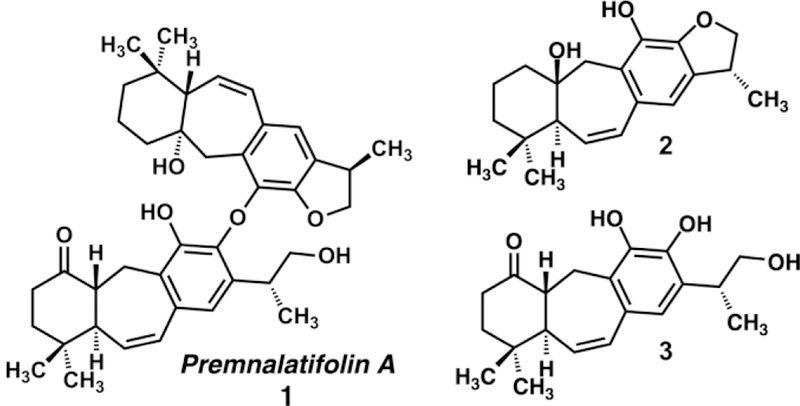

We are interested in the synthesis of monomeric and dimeric icetexane diterpenoid natural products (e.g. 2, 3, Figure 1), and have developed a simple strategy for the synthesis of the 6-7-6 monomeric units. We describe here a two-step sequence for the construction of the central seven-membered ring based on an enolate alkylation and an olefin metathesis reaction.

Figure 1.

Dimeric and monomeric icetexane diterpenoids.

Icetexane diterpenoids have been examined by other synthetic organic chemistry groups in the past owing to their interesting structures and important biological activities. Several distinct strategies have been described including cycloadditions and metal-mediated cycloisomerizations[6] and Friedel–Crafts type annulations and/or other cationic chemistry.[7] Some of these strategies are reliant upon enolate alkylations, carbonyl additions, or otherwise metalated carbonyl compounds,[8] but require several steps of processing to generate the central seven-membered ring and adjust functional groups. Our use of enolates derived from silylenol ether and prefunctionalized aromatic precursors ideally positions appropriate functional groups with the correct oxidation levels to make for short, convergent syntheses of monomeric icetexane terpenoids.

We originally intended to employ the enolate–OQM coupling reaction developed in our laboratories[9] to join a vinyl-bearing silylenol ether derived from 4,4-dimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one with a highly functionalized tert-butyldimethylsilyloxybenzyl chloride under the action of tetramethylammonium fluoride (Scheme 1). The central seven-membered ring of the monomeric icetexanes would then be completed by a ring-closing metathesis reaction;[10] our proposed two-step strategy is distinctly different from prior efforts and would represent the most convergent synthesis of these natural products to date.

Scheme 1.

An enolate–OQM coupling reaction followed by hemiacetal formation.

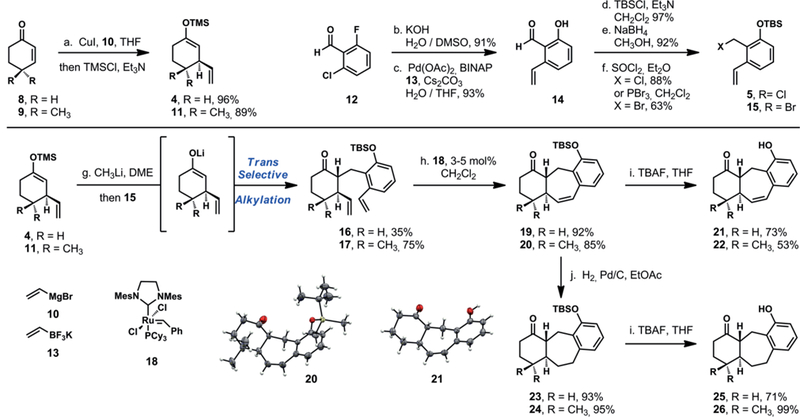

As a means of assessing the feasibility of this reaction sequence, we prepared a simplified model system with a silylenol ether derived from 2-cyclohexen-1-one and a silyloxy benzyl chloride derived from 2-chloro-6-fluorobenzaldehyde (Scheme 2a). The silylenol ether is available in a one-pot operation; conjugate addition of vinylmagnesium bromide in the presence of copper(I) iodide to 2-cyclohexen-1-one in THF at −78 °C gives the corresponding enolate which is then trapped with chlorotrimethylsilane to give the silyl ether 4 in 96 % yield.[11] The silyloxybenzyl chloride 5 was synthesized in five steps. A nucleophilic aromatic substitution with potassium hydroxide and 2-chloro-6-fluorobenzaldehyde (12) gave the corresponding chlorosalicylic acid in 91 % yield.[12] The vinyl group was installed by a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling with potassium vinyltrifluoroborate under the action of palladium(II) acetate with (±)-BINAP as ligand in DMF/water to give the styrene aldehyde 14 in 93 % yield.[13] Finally, silyl protection, reduction of the aldehyde and conversion of the resultant alcohol to the corresponding benzyl chloride (5) was achieved in three steps and 79 % overall yield (See Supporting Information for the detailed preparation of each component).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the Premnalatifolin A core structure. Conditions: (a) CuI, 10, THF, –78 °C, then TMSCl, Et3N, −78 → 23 °C. (b) KOH, H2O/DMSO, 23 °C. (c) Pd(OAc)2, (±)-BINAP, 13, Cs2CO3, H2O/THF (1:9), 135 °C. (d) TBSCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 23 °C. (e) NaBH4, CH3OH, 0 → 23 °C. (f ) SOCl2, Et2O, 0 → 23 °C or PBr3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C. (g) CH3Li, DME, 0 °C, then 15, 0 → 23 °C. (h) 18 (3–5 mol-%), CH2Cl2, 40 °C. (i) TBAF (1.0 M in THF), THF, 23 °C. (j) H2, 10 % Pd/C, EtOAc, 23 °C.

We found that the silyl ether 4 and the silyloxybenzyl chloride 5 joined smoothly in minutes upon exposure to TMAF in cold dichloromethane, and did so diastereoselectively to give the 1,2-trans alkylation product 6 exclusively (Scheme 1).[14] Despite this success, the enolate–OQM reaction strategy was undermined by a post-alkylation addition of the phenol to the carbonyl function to give a robust diastereomeric (and separable) pair of cyclic hemiketals 7. We were able to characterize one epimer by X-ray crystal diffraction, however each epimer slowly equilibrates back to a statistical mixture upon prolonged standing in protic solvent. We observed similar complications with other ketophenol substrates during our development of the enolate–OQM coupling reaction but unlike those simpler systems, we were unable to develop conditions under which the open ketophenol 6 could be captured.[9]

We attempted the ring-opening process under basic and acidic conditions, as well as conditions under which the phenol might be captured as the corresponding ether in order to prevent reclosure.[9,11] We overcame this complication by retreating to a more traditional enolate alkylation approach employing the silyloxybenzyl bromide 15 and the lithium enolate obtained by treating the silyl ether 4 with methyllithium in DME at −78 °C.[15] In contrast to the rapid enolate–OQM reaction, this traditional alkylation proceeds very slowly and takes several hours to reach completion presumably due to the lower reactivity of the alkyl halide relative to the corresponding OQM, and the significant steric congestion. This reaction keeps the silyl group intact to prevent the unproductive carbonyl addition, and also proceeds diastereoselectively to give the 1,2-trans alkylation product 16 in 35 % yield. The balance of the material was a regioisomeric alkylation product that presumably arises via enolate isomerization that can occur upon prolonged stirring of starting materials and products under these reaction conditions. The alkylation also functioned well with the enolate generated from 4,4-dimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one, giving the highly substituted cyclohexanone 17 in 75 % yield; the balance of the material in that reaction was also the regioisomeric alkylation product. Our efforts to suppress the formation of the regioisomeric alkylation product and enhance the rate of these alkylation reactions with additives such as 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6- tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone (DMPU), hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA), and metal salts were unsuccessful.[16]

Following the alkylation events, the vinyl groups were joined under the action of the Grubbs second generation catalyst[9] in straightforward ring-closing metathesis reactions to give the corresponding seven-membered rings 19 and 20, featuring the core structure of monomeric icetexane natural products in 92 % and 85 % yield, respectively. Alternatively, rigorous separation of the alkylation products proved unnecessary; the mixture of alkylation products could be subjected to the ring closing metathesis reaction directly to give the cycloheptenes in 32 % and 48 % yield, respectively, over two steps.[17] Moreover we were able to characterize the tricyclic gem-dimethyl-substituted product by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Following both olefin metathesis reactions, we further diversified our scaffold preparations by generating the fully saturated icetexane skeletons. The analogues 23 and 24 were prepared in 93 % and 95 % yield, respectively, by hydrogenation of the cyclohexene products under the action of palladium on carbon in ethyl acetate. Finally, we removed the tert- butyldimethylsilyl protecting groups by treatment with tetra-n- butylammonium fluoride in tetrahydrofuran at 23 °C to give ketophenols 21, 22, 25, and 26 in 53–99 % yield.

We are now exploring the potential of icetexane natural products and simplified analogues as anticancer agents. To determine the effect of our simplified analogues on cell viability, the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line was treated with increasing concentrations of each compound. Cell viability was determined 72 hours following treatment with compound using a standard commercially available MTT cell viability assay. Issues arising from the poor solubility of compounds 21, 22, and 26 in the cell culture media precluded detailed study of these materials; only the effect of compound 25 on cell viability was determined. Cell survival of the MCF-7s decreased with increasing concentrations of compound 25, and we determined a LD50 of 250 μM (Figure 2). In addition, SUM159 cells treated with increasing concentrations of compound 25 showed a similar decline in cell viability (data not shown). This activity is far from that reported for the premnalatifolins and other similar icetexanes, but is important information nonetheless, as we assess these compounds for future analogue synthesis.

Figure 2.

MCF-7 cell viability following treatment with 25.

Conclusion

We are presently generating the fully functionalized monomeric subunits of premnalatifolin A as well as a series of closely related analogues in order to gain a more detailed survey of the biological potential of these interesting natural products. These studies will be reported in due course.

CCDC 1538503 (for 7), 1538504 (for 20), and 1538505 (for 21) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallo-graphic Data Centre.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA163287) and the University of Delaware is gratefully acknowledged. Spectral data were acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIS funding (NSF CHE0421224, CHE1229234, and CHE0840401; NIH P20GM103541, P20GM104316, P30GM110758, S10RR02692, and S10OD016267). We thank Materia, Inc. for a generous donation of ruthenium catalyst.

References

- [1].For a recent review, see: Simmons EM, Sarpong R, Nat. Prod. Rep 2009, 26, 1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2] a).Devi KP, Anandan R, Devaki T, Apparanantham T, Balakrishna K, Biomed. Res 1998, 19, 339–342; [Google Scholar]

- b).Pandima Devi K, Sai Ram M, Sreepriya M, Ilavazhagan G, Devaki T, Biomed. Pharmacother 2003, 57, 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].For recent examples, see: a) Naidu VGM, Atmakur H, Katragadda SB, Devabakthuni B, Kota A, Reddy SCK, Kuncha M, Vardhan MVPSV, Kulkarni P, Janaswamy MR, Sistla R, Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 497; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- b).Salae A, Rodjun A, Karalai C, Ponglimanont C, Chantrapromma S, Kanjana-Opas A, Tewtrakul S, Fun H, Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 819 [Google Scholar]

- c).Uchiyama N, Kiuchi F, Ito M, Honda G, Takeda Y, Khodzhimatov OK, Ashurmetov OA, J. Nat. Prod 2003, 66, 128; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d).Rekha K, Richa P, Babu KS, Rao JM, Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci 2015, 4, 317; [Google Scholar]

- e).Suresh G, Babu K, Rao V, Rao M, Nayak V, Ramakrishna S, Tetrahedron Lett 2011, 52, 1273. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Suresh G, Babu K, Rao M, Rao V, Yadav P, Nayak V, Ramakrishna S, Tetrahedron Lett 2011, 52, 5016. [Google Scholar]

- [5].For a review, see: Tacar O, Sriamornsak P, Dass CR, J. Pharm. Pharmacol 2013, 65, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].For representative examples, see: a) Padwa A, Chughtai MJ, Boonsombat J, Rashatasakhon P, Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 4758; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- b).de Cortez JF, Lapointe, Hamlin AM, Simmons EM, Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 5665.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- c).Simmons M, Sarpong R, Org. Lett 2006, 8, 2883.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d).Simmons EM, Yen JR, Sarpong R, Org. Lett 2007, 9, 2705.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e).Kametani T, Kondoh H, Tsubuki M, Honda T, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1990, 5; [Google Scholar]

- f).Padwa A, Boonsombat J, Rashatasakhon P, Willis J, Org. Lett 2005, 7, 3725; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- g).Kolodziej I, Green JR, Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 10852–10864; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- h).Xing S, Li Y, Li Z, Liu C, Ren J, Wang Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 12605–12609; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2011, 123, 12813. [Google Scholar]

- [7].For representative examples, see: a) Majetich G, Zhang Y, Feltman TL, Belfoure V, Tetrahedron Lett 1993, 34, 441; [Google Scholar]

- b).Majetich G, Zou G, Org. Lett 2008, 10, 81.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- c).Thommen C, Neuburger M, Gademann K, Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 120.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d).Matsumoto T, Imai S, Yoshinari T, Matsuno S, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1986, 59, 3103.; [Google Scholar]

- e).Deb S, Bhattacharjee G, Ghatak UR, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1990, 1453; [Google Scholar]

- f).Wang X, Cui Y, Pan X, Chen Y, Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg 1995, 104, 563; [Google Scholar]

- g).Majetich G, Hicks R, Zhang Y, Tian X, Feltman TL, Fang J, Duncan S Jr., J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 8169; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- h).Tuckett MW, Watkins WJ, Whitby RJ, Tetrahedron Lett 1998, 39, 123; [Google Scholar]

- i).Wang X, Pan X, Cui Y, Chen Y, Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 10659; [Google Scholar]

- j).Li Y, Li L, Guo Y, Xie Z, Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 9282–9286. [Google Scholar]

- [8].For representative examples, see: a) Majetich G, Zhang Y, Feltman TL, Duncan S Jr., Tetrahedron Lett 1993, 34, 445; [Google Scholar]

- b).Koft ER, Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 5775; [Google Scholar]

- c).Martinez-Solorio D, Jennings MP, Org. Lett 2009, 11, 189; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d).Wang X, Pan X, Zhang C, Chen Y, Synth. Commun 1995, 25, 3413; [Google Scholar]

- e).Wang XC, Pan XF, J. Indian Chem. Soc 1996, 73, 497; [Google Scholar]

- f).Ning C, Wang X-C, Pan X-F, Synth. Commun 1999, 29, 2115; [Google Scholar]

- g).Sengupta S, Drew MGB, Mukhopadhyay R, Achari B, Banerjee AK, J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 7694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- h).Suto Y, Nakajima-Shimada J, Yamagiwa N, Onizuka Y, Iwasaki G, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 25, 2967–2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lewis RS, Garza CJ, Dang AT, Pedro T-KA, Chain WJ, Org. Lett 2015, 17, 2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10] a).Grubbs RH, Chang S, Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 4413; [Google Scholar]

- b).Fürstner A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2000, 39, 3012; Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 3140; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- c).Grubbs RH, Handbook of Metathesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2003; Vol 1, p. 2 [Google Scholar]

- d).Grubbs RH, Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7117; [Google Scholar]

- e).Grubbs RH, Vougioukalakis GC, Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11] a).Chen Y, Huang J, Liu B, Tetrahedron Lett 2010, 51, 4655; [Google Scholar]

- b).Jones TK, Denmark SE, J. Org. Chem 1985, 50, 4037; [Google Scholar]

- c).Bergmann ED, Ginsburg D, Pappo R, Org. React 1959, 10, 179; [Google Scholar]

- d).Little RD, Masjedizadeh MR, Wallquist O, McLoughlin JI, Org. React 1995, 47, 316. [Google Scholar]

- [12] a).Anelli PL, Banfi S, Legramandi F, Montanari F, Pozzi G, Quici S, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1993, 1345; [Google Scholar]

- b).Vilain S, Maillard P, Momenteau M, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1994, 1697.

- [13] a).Alacid E, Nájera C, J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 8191; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- b).Birkholz M-N, Freixa Z, van Leeuwen P, Chem. Soc. Rev 2009, 38, 1099; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- c).Molander GA, Brown AR, J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 9681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].For discussions of the stereoselective alkylation of substituted cyclohexanones, see: a) Evans DA, in Asymmetric Synthesis (Ed.: Morrison JD), Academic: Orlando, 1984, vol. 3, pp. 1–110; [Google Scholar]

- b).House HO, Tefertiller BA, Olmstead HD, J. Org. Chem 1968, 33, 935; [Google Scholar]

- c).Kuwajima I, Nakamura E, Shimizu M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 1025. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stork G, Hudrlik PF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1968, 90, 4464. [Google Scholar]

- [16] a).Seebach D, Bossler H, Gruendler H, Shoda S, Wenger R, Helv. Chim. Acta 1991, 74, 197; [Google Scholar]

- b).Miller SA, Griffiths SL, Seebach D, Helv. Chim. Acta 1993, 76, 563; [Google Scholar]

- c).Bossler HG, Seebach D, Helv. Chim. Acta 1994, 77, 1124. [Google Scholar]

- [17].The chromatographic separation of 16 and 17 from the regioisomeric alkylation product is tedious, but unnecessary. The yield of the ring-closing metathesis reaction is unaffected by the presence of the isomeric alkylation products, which are easily separated from the ring-closed products 19 and 20.