Abstract

Fabrication of microchip-based devices using 3-D printing technology offers a unique platform to create separate modules that can be put together when desired for analysis. A 3-D printed module approach offers various advantages such as file sharing and the ability to easily replace, customize, and modify the individual modules. Here, we describe the use of a modular approach to electrochemically detect the ATP-mediated release of nitric oxide (NO) from endothelial cells. Nitric oxide plays a significant role in the vasodilation process; however, detection of NO is challenging due to its short half-life. To enable this analysis, we use three distinct 3-D printed modules: cell culture, sample injection and detection modules. The detection module follows a pillar-based Wall-Jet Electrode design, where the analyte impinges normal to the electrode surface, offering enhanced sensitivity for the analyte. To further enhance the sensitivity and selectivity for NO detection the working electrode (100 μm gold) is modified by the addition of a 27 μm gold pillar and platinum-black coated with Nafion. The use of the pillar electrode leads to three-dimensional structure protruding into the channel enhancing the sensitivity by 12.4 times in comparison to the flat electrode (resulting LOD for NO = 210 nM). The next module, the 3-D printed sample injection module, follows a simple 4-Port injection rotor design made of two separate components that when assembled can introduce a specific volume of analyte. This module not only serves as a cheaper alternative to the commercially available 4-Port injection valves, but also demonstrates the ability of volume customization and reduced dead-volume issues with the use of capillary-free connections. Comparison between the 3-D printed and a commercial 4-Port injection valve showed similar sensitivities and reproducibility for NO analysis. Lastly, the cell culture module contains electrospun polystyrene fibers with immobilized endothelial cells, resulting in 3-D scaffold for cell culture. With the incorporation of all 3 modules, we can make reproducible ATP injections (via the 3-D printed sample injection module) that can stimulate NO release from endothelial cells cultured on a fibrous insert in the cell culture module which can then be quantitated by the pillar WJE module (0.19 ± 0.03 nM/cell, n = 27, 3 inserts analyzed each day, on 9 different days). The modular approach demonstrates the facile creation of custom and modifiable fluidic components that can be assembled as needed.

Here we show that separate modules fabricated using 3-D printing technology can be easily assembled to quantitate the amount of nitric oxide released from endothelial cells following ATP stimulation.

Introduction

Three-dimensional (3-D) printing has been gaining substantial attention recently in various areas within the biological and chemical sciences. This rapid prototype technology can build a product in a “layer-by-layer” process. Since its inception in the 1980s by Charles Hull, there are now multiple 3-D printing technology platforms on the market offering diversity in the printing resolution and the materials used.1, 2 While plenty of the applications have been catered towards bio-engineering of tissue and organs,3, 4 the use within the chemical sciences includes production of custom-made reaction ware, utility in making batteries, and fabrication of macro/microfluidic devices.1 Cronin’s group has been 3-D printing reaction devices that are being used in chemical synthesis.5 Furthermore, this same group have been able to produce a reactor device that can easily be connected to a mass spectrometer (ESI-MS) for real-time analysis. With the ability to print multiple materials layer-by-layer, 3-D printing technology has also been applied to producing energy storage devices, with Sun and colleagues being able to 3-D print a micro-lithium battery that exhibit high energy and power densities.6 Lastly, this technology has seen a lot of advancement within microfluidics. For example, the Breadmore group has been able to create visibly transparent microchips that are capable for in-chip isotachophoresis; moreover, they have been able to include micromixers and droplet extractors within the device.7

Microfluidics deals with the manipulation of fluids within micrometer-sized channels. Advantages offered by microchip-based devices as an analytical platform, such as use of small sample volumes and increased throughput, have been described previously.8 Applications of this analytical tool have encompassed molecular analysis and separation studies using electrophoresis,9, 10 as well as remote field sensors and microelectronics.11 Microfluidics has become a powerful tool for conducting cell studies. For example, the Roper group was able to synchronize mice islets using oscillating glucose levels produced by a liver-pancreas feedback loop on a microfluidic device.12 Additionally, our group has published several microfluidic approaches that involve the use of investigating multiple processes, such as the analysis of neurotransmitters released from various cell lines via electrochemical detection.13–15 Microfluidic devices are commonly fabricated by soft lithography using PDMS.2 However, with 3-D printing, a microfluidic device can have some unique features for cell studies. 3-D printing can offer a more streamlined and rapid production platform, addition of unique design features such as threads16 and O-rings17 for leak-free connections, the ability to modify device designs as per need and sharing of design files between different laboratories.16 Fluid manipulation, using valves and pumps incorporated within 3-D printed devices have also been accomplished by various groups. Au and colleagues have been able to use a four-valve switch system to stimulate CHO-K1 cells with ATP and observe calcium release in response.18 Specific uses of 3-D Polyjet printing technology (the type of printer used here) within microfluidics involves producing microfluidic circuitry19 and gradient generators.20 Furthermore, on-chip cell integration of these 3-D printed devices have also been accomplished. The Spence group have been able to investigate cell-to-cell interactions, hormone transport and endocrine secretions by using a 3-D printed system that combined pancreatic β-cells, endothelial cells and a blood flow, clearly demonstrating that 3-D printing can improve the multiplexity, versatility and reusability of such systems.21

Microchip-based cell study devices are traditionally created as a single-chip device. With a totally integrated device, if any part of the chip fails (due to issues such as clogging, cell detachment, etc.), the entire experiment is sacrificed. While many of these highly integrated systems have the temporal resolution and minimal dilution to measure near real-time release from cells, they are relatively low throughput, with each chip having just one layer of cells. Fabrication of multiple device systems can be accomplished via 3-D printing, where in different modules or components can be assembled for analysis. This approach can increase flexibility and robustness of the system; without replacing the entire system; individual modules can easily be optimized, redesigned and fabricated.2 To address some of the aforementioned issues, the modular approach would enable flexible assembly of multiple components serving distinct functions. 3-D printing facilitates the development of modular microfluidics by enabling robust and accurate connecting mechanisms (i.e., threads) between chips. For example, Lee et al. showed a few proof-of-concept 3-D printed modules including mixer and reaction chambers that can be assembled together.20

Our group has been developing various methods to integrate cell culture with analysis. In this work, we moved a step forward by creating a novel 3-D printed microfluidic system incorporating three functional modules that enables online stimulant delivery to endothelial cells and downstream quantitation. The first module we focused on is a pillar WJE device for the direct quantitation of nitric oxide (NO) (Figure 1C). As previously reported, in this configuration the analyte hits the electrode normal to the surface and then spreads out radially, increasing mass transfer at the electrode surface and thus enhancing detection sensitivity.16 Quantitation of NO has been challenging due to its short half-life (2–3 seconds), which leads to the formation of various oxidized species in the presence of oxygen.22–24 Therefore, in this work, modifications of the electrode were developed to enhance its ability for NO quantitation. First, we show that a 3-D pillar on the WJE electrode allows increased mass transfer of the analyte in comparison to a flat electrode. Furthermore, electrode coating with platinum-black and Nafion increases the sensitivity and selectivity of NO, respectively.15

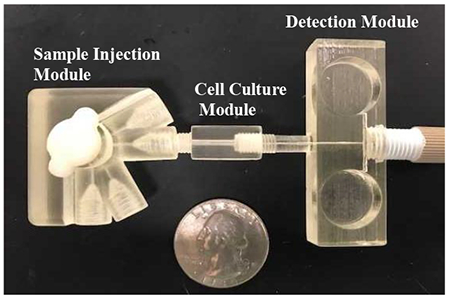

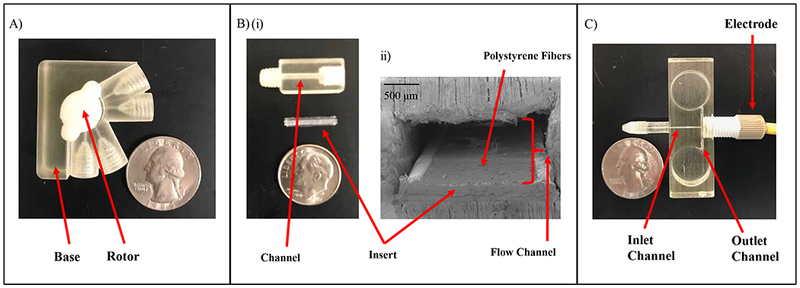

Figure 1.

Modular microfluidic approach using 3-D printing technology. (A) Micrograph of the injection module. This module is a simple 4-Port injector rotor design consisting of 2 components - a base and rotor (containing grooves) that can be assembled. (B) The cell culture module: (i) Micrograph of the fluidic cell culture device and insert separately, (ii) Cross section (SEM image) of an insert with fibers integrated into the cell culture module. (C) Micrograph of the pillar wall-jet module. The working electrode within the IDEX fitting is threaded into the module. The inlet channel is 375 µm × 375 µm and the outlet channel is 750 µm × 750 µm.

The next module was the sample injection module (Figure 1A), which is a customized nanoliter injection device comprised of a two component (base and rotor) system. Commercial 4-Port injection valves offer many advantages such as low dead volumes and integration with different systems, however they are expensive and require additional fittings and capillaries to integrate within the system. Here, 3-D printing allows us to create a cheaper alternative which enables capillary free connections, injection volume customization, low dead volumes and integration with multiple systems.

Lastly, the third module that was developed and characterized is the endothelial cell culture device (Figure 1B). In this module, electrospun fibers were incorporated as a 3-D endothelial cell culture scaffold.25 While most endothelial cell studies are conducted with 2-D cell cultures due to its inexpensive and well-established protocol, issues with the growth media and expansion of cells do pose some limitations. Three-dimensional cell cultures, on the other hand, demonstrate the in vivo microenvironment more holistically and can be integrated to different flow regimes.26, 27 With the incorporation of all three modules, we can conduct on-line stimulation studies on endothelial cells. Endothelium-derived NO is an important messenger molecule within the circulatory system and is involved in various activities such as smooth muscle relaxation, inhibition of platelet activation, and endothelium permeability.28 Thus, discrepancies in NO production have been found to be related to diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular complications. Furthermore, endothelial cells can produce NO in response to various stimuli, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and shear stress.28–31 In this study, with the incorporation of the 3 modules we demonstrate the use of injecting discreet plugs of ATP to stimulate the production of NO from endothelial cells, which is detected in the downstream electrochemistry module. Having the capability to conduct a close to real-time, online stimulation study enables the user to get a better idea about the complex dynamics involved between ATP and NO production from endothelial cells.

Experimental

Chemicals and materials

The following chemicals and materials were used as received: catechol, sodium carbonate, lead (II) acetate, chloroplatinic acid hydrate, potassium dicyanoaurate (I), Nafion perfluorinated resin solution, nitrite ion standard solution, adenosine 5’- triphosphate disodium salt hydrate, N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride, Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS), glutaraldehyde solution and acridine orange hemi (zinc chloride) salt (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA); Armstrong C-7 resin and Activator A (Ellsworth Adhesives, Germantown, WI, USA); Loctite 5 minute clear epoxy (Home Depot); 100 µm gold wire (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA); copper electrical wire, soldering wire and heat shrink tubes (Radioshack); colloidal silver (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA); Fingertight fitting F-120X, capillary tubing connectors F-230 and Super Flangeless Fitting P-131 (IDEX Health & Science, Oak Habor, WA, USA); BAS electrode polishing kit (Bioanalytical Systems Inc, West Lafayette, IN, USA); 75 µm ID flexible fused silica capillary tubing (Polymicro Technologies, Lisle, IL, USA).

Device fabrication

The 3-D printed devices used in these studies were designed using Autodesk Inventor Professional 2016 (San Rafael, CA, USA). The standard tessellation language files (.STL file) created were then sent to the printers to produce the individual modules. The detection module, cell culture module and the sample injection module base (Fig 4-B) are produced using the Objet Eden 260V (Stratsys, Ltd., Edina, MN, USA). The printing material associated with this printer is the Full Cure 720 and Full Cure 705 support material (Stratsys, Ltd., Edina, MN, USA). The composition of the Full Cure 720 material is propriety, but approximately containing 10–30% isobornyl acrylate, 10–30% acrylic monomer, 15–30% acrylate oligomer, 0.1–1% photoinitiator.32 After removing majority of the support material from the device by high pressure water or by hand, a quick rinse with isopropanol allows for some of the leftover support material to be removed. The rotor component of the sample injection module (Fig 4-A) was produced using the MOJO Desktop 3D Printer (Stratsys, Ltd., Edina, MN, USA). The printing material used here is Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) based material, P430 ABS Plus in ivory, and the support material is Polylactic Acid (PLA) based material, SR-30 (Stratsys, Ltd., Edina, MN, USA). The support material can be removed by using the WaveWash 55 Support Cleaning System, using NaOH solution (Stratsys, Ltd., Edina, MN, USA). To help create a smooth surface on the rotor, this component was put into an acetone vapor exposure for 10 minutes and then allowed to air dry overnight. To ensure a leak-free seal, the rotor was also wrapped with Teflon tape (area around grooves being removed). The detailed engineering sketch of the designs of the devices can be found in SI (Figures S1-S3).

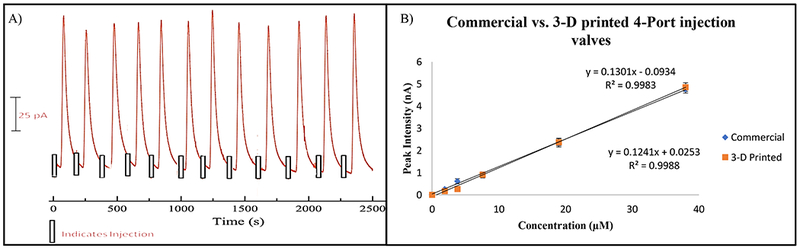

Figure 4.

The 3-D printed sample injection module characterization. (A) The graph shows 12 repeatable injections of 100 µM catechol using the 3-D printed sample injection module. (B) NO calibration curve comparison between a commercial 4-Port (200 nL volume) and the 3-D Printed sample injection module (195 nL volume) using the pillar 100 µm Au electrode. (errors shown as standard deviation)

Nitric oxide analysis and nitrite sample preparation

For all NO studies, a standard stock solution (1.9 mM) was prepared daily by deoxygenating HBSS with Ar for 30 minutes, followed by saturating with pure NO gas (99.5%) for 30 minutes. The NO gas was purified before use by passing through a column packed with KOH pellets to remove trace NO degradation products.33, 34 Individual standards were made in deoxygenated volumetric flasks (sealed with suba seals) and deoxygenated HBSS buffer. Use of air-tight syringes and capillaries limit oxygen contact to the sample. NO standards (varying concentrations 0.5–195 µM) were used for all the studies. In addition to NO for the Nafion study, a 95 µM nitrite standard in HBSS was made from 0.1 M nitrite ion standard solution (Millipore-Sigma, St Louis, MO). Amperometric detection of NO and nitrite samples was performed with a 3-electrode system using a CH Instruments potentiostat (Austin, TX, USA) at +0.85 V. The working electrode here was the 100 µm gold pillared electrode used in the WJE device as will be described below; platinum wire was used as the auxillary and Ag/AgCl (3.0 M KCl filling solution) was the reference. The auxillary and reference electrodes were placed in the outlet reservoir during the studies.

Pillar wall-jet module - preparation and characterization

Fabrication of the working electrode in the IDEX Flangeless fitting begins with affixing (soldering and connecting with colloidal silver) a 100 µm diameter gold wire to a copper extending wire. Heat shrink tubing is used to insulate the connection before affixing it into the fitting. As previously reported, proper centering of the electrode material within the fitting is accomplished by threading the wire through 3-D printed disks (diameter: 3.2 mm, hole size: 0.25 mm and thickness up to 1.5 mm). Epoxy (5-minute clear) is applied to the base to hold the electrical wire within the fitting.16 Following the assembly, a thoroughly mixed combination of 0.5750 g Armstrong C-7 Adhesive (resin) and 48 µL Armstrong Activator A is applied drop wise onto the electrode. The mixture is then cured over night at room temperature followed by wet polishing to allow the electrode to become flush with the fitting.

A gold pillar (27.1 ± 2.2 µm, n = 20 different gold pillars, Figure 2) on a 100 µm gold electrode is produced by electrodeposition. The electrodeposition was carried out by the electrode surface in a small beaker with a 1 ml solution of 50 mM dicyanoaurate (I) and 0.1 M Na2CO3 solution and applying a potential of −1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) to the gold electrode. For the platinum - black deposition on the working electrode, a 300 µL reservoir in a 3-D printed device with threads allowing the working electrode to be screwed into the reservoir filled with 3.5% chloroplatinic acid (w/v) and 0.005% lead (II) acetate trihydrate solution over the working electrode. Electrodeposition is achieved by cycling the potential from +0.6 to −0.35 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 20 mVs−1. Nafion coating over the pillared Pt-blk coated working electrode was accomplished by pipetting 10 µL of a 0.075 or 0.1% Nafion solution (diluted with IPA and made from a 5% solution of Nafion, Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and allowing it to air dry for 30 minutes.

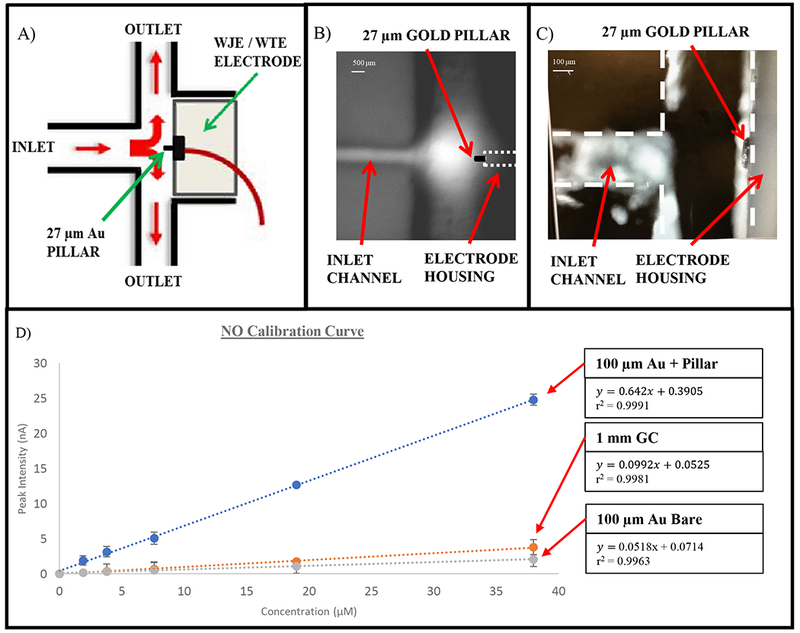

Figure 2.

Pillar wall-jet module with Platinum-Black. (A) Schematic of the WJE electrode with the gold pillar extending into the channel (not to scale). (B) Micrograph depicting a fluorescein injection plume hitting the electrode housing. The dotted line represents the pillar electrode for clarity. (C) Micrograph of a 27 µm gold pillar electrodeposited on the 100 µm gold electrode. The dotted channel and electrode housing surface is shown for clarity. (D) NO calibration curve comparison between a 1 mm glassy carbon, 100 µm gold electrode with and without a pillar (errors shown as standard deviation). To increase NO sensitivity, all electrodes were electrodeposited with Pt-Blk.

Sample injection module – preparation and characterization

Following the acetone vapor treatment, the injection groove volume (on the rotor component) was calculated via a casting method followed by SEM imaging using an Inspect F50 Scanning Electron Microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). Half-cured PDMS cast were created by making a 20:1 (elastomer: curing agent) mold of the injection groove (cured for 20 minutes). The cast was removed from the rotor, sputter coated with gold, and imaged with SEM. Images of the width, length and height were made to yield the volume of the groove.

Catechol standards (varying concentrations 0.5–200 µM) were used for the comparison between a commercial 4-Port injection valve (Vici Rotor, Valco Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) and the 3-D printed sample injection module. These solutions were prepared in TES buffer (pH 7.4) from a 10 mM catechol stock solution. A TES buffer flow stream was continuously pumped at 3.0 µL/min to the device via a 500 µL syringe (SGE Analytical Science) and a syringe pump (Harvard 11 plus, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The syringe was connected to a 75 µm ID capillary tubing using a finger tight PEEK fitting and a Luer adapter (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA, USA). The 3-D printed sample injection module was connected to the WJE detection module via the embedded threads on the device, whereas the commercial 4-Port injection valve was connected via the use of a finger tight PEEK fitting, a Luer adapter and a 75 µm ID capillary to transition from the 4-Port injector to the detection module. The commercial 4-Port injection valve enabled a reproducible 200 nL injections to the microchip channel and the 3-D printed sample injection module enabled a reproducible 195 nL injections. Amperometric detection of catechol samples was performed with a 3-electrode system using a CH Instruments potentiostat (Austin, TX, USA) at +0.9 V. The working electrode here was the 100 µm gold pillared electrode; platinum wire (500 µm) was used as the auxiliary and Ag/AgCl (3.0 M KCl filling solution) was the reference. The auxiliary and reference electrodes were placed in the outlet reservoir during the studies.

Insert-based cell culture module – preparation and characterization

To prepare the inserts for cell immobilization, the inserts were affixed to the bottom of a 40 mm petri dish using double sided tape and then placed in the laminar flow hood for 4 hours under UV light, after which time bovine pulmonary endothelial cells (bPAECs; ATCC Manassas, VA, USA) were harvested from a confluent culture flask using established methods (see SI for details).15 The harvested cells were centrifuged at 500 G for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, followed by the addition of 1 mL of fresh DMEM to resuspend the cells. A 500 µL aliquot of the cell suspension (see section 1 in SI for information about endothelial cell culture) was pipetted onto the inserts followed by incubation (37 °C, 5 % CO2) for 4 hours, after which the remainder of the cell suspension plus 4 mL of fresh media were added to the inserts. The inserts were then allowed to incubate (37 °C, 5 % CO2) for 24 hours. After examining an example insert to assure cell growth under an optical microscope, another insert was placed into the printed slots along the channel in the cell culture module, as seen in Figure 2B. followed by sliding an insert into the cell culture module using tweezers for analysis. The detection of NO from these cells was accomplished by injecting a plug of ATP stimulant (100 µM) through the 3-D printed sample injection module flowing over the cell culture to stimulate the endothelial cells to produce NO, which will then flow through the WJE device. Changes in NO oxidation are continuously monitored at the working electrode within the WJE detection device. Figure 6A has a schematic of how the 3 modules are assembled for the analysis.

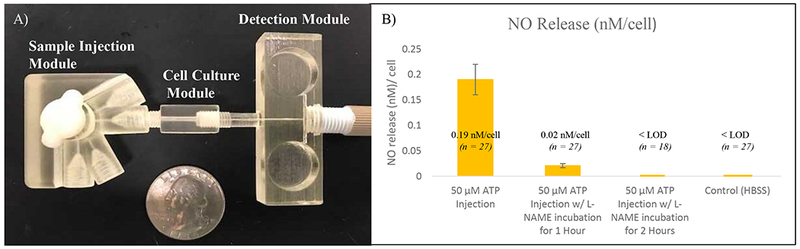

Figure 6.

The fully assembled modular quantitation. (A) Micrograph of all 3 modules put together using the threaded ports. (B) NO cell release data per cell after a 50 µM injection of ATP under normal conditions, incubation with L-NAME for 1 hour and 2 hours and HBSS control

To normalize the amount of NO release to per cell, the Hoechst assay was conducted to determine the number of endothelial cells on each insert after an analysis.35 Following ATP stimulation and subsequent NO detection, the insert was removed from the cell culture module and soaked in 500 µL of DI water in a 1.7 mL centrifuge vial for 2 hours. Complete cell lysis, with in the vial, is then accomplished by vigorous vortex mixing for 10 minutes. Cell counting on the insert can be accomplished by quantifying the amount of released DNA using the Hoechst assay. The stock Hoechst 33258, pentahydrate (Life Technologies, OR, USA) was first diluted from 10 mg/ mL to 0.02 mg/ mL with TNE buffer (42 mM Tris-HCl, 4.2 mM EDTA and 8.4 M NaCl, all chemicals from Millipore-Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Using a 96 well plate, 50 µL of the prepared Hoechst assay, 100 µL of TNE buffer and 100 µL of the cell lysate was added together immediately before analysis with the plate reader (MoleularDevices, CA, USA) under fluorescence mode (350 nm for excitation and 460 nm for emission). A calibration curve was constructed by first counting a certain number of cells with a hemocytometer and then lysing them in DI water to make a stock solution. The stock solution was then serially diluted to acquire standards of various lysed cell numbers, which were then measured with the Hoechst assay.

Fluorescent imaging of endothelial cells was accomplished using Acridine Orange (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). A cell insert was first washed with HBSS, followed by 10 minutes of incubation at 37 °C with 5 µg/mL acridine orange in HBSS. After 4 additional rinses with HBSS, images of the cells were taken using an upright fluorescent microscope (Olympus EX 60) equipped with a 100 W Hg Arc lamp and a cooled 12-bit monochrome Qicam Fast digital CCD camera (QImagind, Montreal, Canada). Images were captured with Streampix Digital Video Recording software (Norpix, Montreal, Canada). The SEM images were captured after rinsing the cell inserts with HBSS followed by fixing the cells with a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in HBSS. After incubating the cells for 30 minutes at 37 °C, the cell inserts were rinsed 4 times with HBSS. The cell inserts are then allowed to air dry for 2 hours before sputter coating the inserts followed by SEM imaging.

Results and Discussion

In this work, we used a 3-module microfluidic approach that includes a sensitive and selective electrochemical module, a flexible endothelial cell culture module, and a nano-liter sample injection module. With this setup, endothelial cells cultured on fibrous inserts can be first examined under a microscope to confirm a successful culture, which will then be integrated in the cell culture module. The customized injection module allows delivery of ATP plugs to stimulate endothelial cells, with the downstream electrochemical module being used to quantitate endothelium derived NO down to mid nM level. Compared with fully integrated microfluidic devices, the modular approach makes it possible to control the quality of each module separately and replace/rearrange modules flexibly. Also, by using 3-D printing, customized connection threads were designed on the modules so that they can be easily connected with minimal dead volume.

The Pillar Wall-Jet Module

The widespread interest in NO due to its diverse biological roles has generated a significant demand for analytical techniques to quantitate this molecule.24, 36, 37 However, such measurements can be difficult due to NOs widely ranging concentrations and high instability (half-life = 2–3 seconds).38, 39 An analytical tool that can effectively detect NO demands a proper dynamic range, sufficient sensitivity and fast response time. The method must also be selective towards NO over interfering species that arise from complex biological samples and NO derivatives. There have been a few methods developed for the detection of NO (direct detection with fluorescence) and its products or metabolites, such as NO2− (indirect detection with UV-vis spectroscopy).40, 41 While the sensitivity offered by fluorescence is good, quantitation of NO is done for an accumulated amount of time (tens of minutes) rather than at a particular time point.40, 41 With the UV-vis method, NO is measured indirectly via its oxidized product nitrite.40 This indirect method requires an incubation step and does not offer low limits of detection.40 Electrochemistry, on the other hand, provides another way to directly quantitate NO, which can potentially achieve near real-time measurements. Traditional microchip-based devices follow the thin-layer electrode design due to the planar nature of the fabrication process.16 While NO quantitation has been accomplished by using this device design, not all the analyte is detected at the electrode. In this design, the flow of the analyte is adjacent to the electrode hence only the analyte close to the electrode can be detected. To overcome this, our group reported the use of an alternate electrode design for microfluidics: a wall-jet electrode (WJE),16 where the analyte hits the electrode normal to the surface and then spreads out radially, increasing the mass transfer at the electrode surface and thus improving the detection sensitivity. The previously described WJE device used a 1 mm glassy carbon electrode.16 In this work however, we wanted to explore the use of a smaller electrode with modifications to detect NO with enhanced sensitivity down to nM range.

Firstly, we incorporated the use of a micro (100 µm) gold electrode in the electrochemical module. A smaller electrode is more attractive for detecting NO due to some inherent advantages. First, a smaller electrode offers a more efficient mass transport.42 The edges of an electrode are considered active sites of the electrode; thus by decreasing the electrode size, the edges contribute more substantially to the overall diffusion current increasing the mass transfer rates.43, 44 Secondly, a smaller electrode has a reduced double layer, which can decrease the charging current (background), thus increasing the signal-to-noise ratio.43, 44 To truly get the detection limits in the mid-nanomolar regime for NO, modifications were then made to this working electrode. The first modification was the addition of a gold pillar onto the electrode. A 90-minute gold deposition time resulted in an approximate 27.1 ± 2.2 µm tall gold pillar on the electrode material (Figure 2B and C). The protrusion of this 3-D pillar into the outlet channel allows the access of more analyte in the wall-jet plume, thus enhancing the signal as can be seen by the calibration curves in Figure 2D. The next modification was to platinize the pillared electrode. Several groups have demonstrated the use of Pt-Blk electrodes to increase the electrode surface area and act as a catalyst to increase the electron transfer rate, with the resulting signal being increased from 8–13 times for the detection of NO, as compared to the use of unmodified electrodes.15, 45–48 The platinization process involves the electrochemical deposition of platinum-black particles on the surface of the electrode; this creates a rough surface and thus adds more area to the pillar electrode being used.15 To prove the efficacy of the modification protocols, we conducted a comparison study between a 1 mm glassy carbon/Pt-Blk, a flat (no pillar) 100 µm gold/Pt-Blk electrode and a pillar 100 µm gold/Pt-Blk electrode (Figure 2D shows a same day NO calibration curve comparison between the 3 electrodes). As seen here, the sensitivity is 12.4 times greater for the pillar gold/Pt-Blk electrode versus the flat gold/Pt-Blk electrode. Furthermore, the LOD was also significantly improved with the use of the platinized pillar electrode. The resulting LODs for the 1 mm glassy carbon/Pt-Blk is 1.8 µM, the flat 100 µm gold/Pt-Blk electrode is 0.84 µM and the pillar 100 µm gold/Pt-Blk electrode is 0.054 µM (54 nM), respectively.

NO can be readily oxidized into NO2− and other products in an aqueous solution.49 More importantly, NO2− can be electrochemically oxidized at a similar potential as NO. Therefore, the continuous accumulation of NO2− in a sample can interfere the detection of NO production from endothelial cells at a certain time. To minimize this interference, in addition to the platinized pillar electrode, the electrode was further coated with a layer of Nafion, a perm-selective anionic membrane, to selectively permit neutral and positive small molecules to the electrode.50, 51 However, this additional porous layer can potentially reduce diffusion of the target molecule to the electrode surface. To investigate the effect of the Nafion layer, the platinized pillar 100 µm gold electrode was coated with 10 µL 0.1% Nafion to compare NO and NO2− exclusion (using 95 µM concentration for both NO and NO2−). Preparation and application of the Nafion solution is described in the experimental section. The bare platinized pillar electrode gave an average signal of 3.40 ± 0.1 nA (n = 5) for NO and 0.580 ± 0.02 nA (n = 5) for NO2−, giving a peak height ratio of NO to NO2− of 5.9. Using the 0.1 % Nafion concentration, significant exclusion of NO2− (95 µM) was achieved (average peak height = 0.162 ± 0.007 nA, n = 5) compared to signal obtained from equimolar injections of NO (average peak height = 1.79 ± 0.04 nA, n = 5), giving a NO to NO2− ratio of 11.1. A loss in NO sensitivity (as compared to the use of no Nafion) is probably caused by the membrane thickness, however some membrane thickness is needed for nitrite exclusion. Using the 0.1 % Nafion coating, a NO calibration curve demonstrates a sensitive calibration curve with an LOD of 210 nM. Figure S4 show the NO and NO2− exclusion after the application of 0.1% Nafion to the electrode surface.

Sample Injection Module

This module was designed to create a 3-D printed injector capable of providing a low cost and robust method of introducing a defined volume of sample to a carrier stream. Commercial 4-Port injection valves provide precise injections and can be integrated with various systems; however, are often not portable and expensive to buy and maintain. With 3-D printing we can create a cheaper alternative that is easy to maintain, offers low dead volumes, withstands different flow rates and can be integrated to multiple systems. To develop this module, a simple rotary valve design was used in two distinct components: a rotor containing a groove (Figure 3A) capable of making specific and reproducible volume injections, and a base (Figure 3B) that houses the rotor component (Figure 3C). With this design, two separate streams (buffer and sample) can intersect once the rotor is rotated. For example, we can introduce a sample plug (from the analyte in the groove) into the buffer stream. Fabrication of this module involved the use of two different 3-D printing materials to create a robust module and minimize leaking as injection are made during analysis. The rotor was printed with the ABS material and surface roughness of the material can be smoothed by use of an acetone vapor exposure. This was essential because printing both components using the Full Cure 720 can result in leakage due to surface roughness that could not be addressed with the use of acetone vapor treatment. It was found that the Full Cure 720 material softens, swells, and loses rigidity with an acetone vapor treatment. The acetone treatment process helps to smoothen the surface of the ABS printed rotor via slightly dissolving and smoothing the outer layer of the rotor. To ensure a leak-free seal, the rotor was also wrapped with Teflon tape (area around grooves being removed).

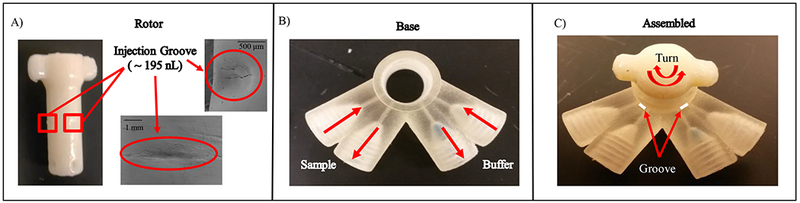

Figure 3.

The 3-D printed sample injection module. (A) Micrograph on the left shows the first component of the sample injection module, the rotor. This rotor contains two injection grooves and is made of the ABS material. The image shows the smooth surface of ABS after acetone vapor treatment. The SEM images on the right show the injection groove from two different angles. (B) Micrograph shows the base of the sample injection module that houses the rotor and is made of the Full Cure 720 material. (C) Micrograph shows the full assembly of the sample injection module showing how the assembly turns. (Arrows and groove outline added to describe the operation)

Injection groove volume measurements can be conducted by first creating a PDMS mold of the groove followed by SEM imaging. The resulting groove (sample injection) volume was 195 nL in comparison to 200 nL offered by the commercial 4-Port injection valve used in this comparison study. To further verify if this customized module can make reproducible injections, it was connected to the WJE detection module via the threaded ports designed on the devices. The module robustness was accomplished by measuring reproducible injections of 100 µM catechol in TES buffer electrochemically. As seen in Figure 4A, 12 reproducible injections of catechol led to an average peak height of 124 ± 10.4 pA. Finally, a comparison study between the 3-D printed module and a commercially available 4-Port injection valve was conducted. With all the electrode modifications added as mentioned earlier, same day calibration curves were conducted for NO. As seen in Figure 4B, both injection valves yield similar sensitivities. As demonstrated, the 3-D printed sample injection module can provide reproducible peaks and comparable results to the commercial 4-Port injection valve. While commercially available 4-Port injection valves do have their advantages, they are often expensive to purchase (costing $500-$2000) and can be costly to maintain (each rotor costing ~$150). Conversely, here we show a cheaper alternative that can be modified to accommodate different volumes and printed on demand. More importantly, we have created a 3-D printed injection system capable of low dead volumes by directly connecting to the other modules through the designed threaded ports, without the use of capillaries or fittings (Figure 6A).

Flexible Endothelial Cell Culture Module

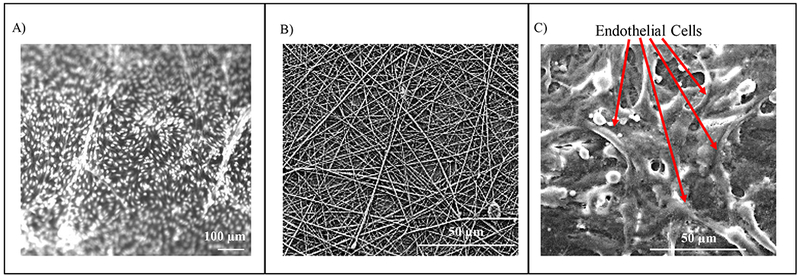

Endothelial cells constitute the inner wall of blood vessels forming a continuous smooth monolayer of cells.22, 49, 52 Some of its physiological functions involve the maintenance of vascular tone or structure, maintenance of proper blood viscosity and NO production.49, 52 One of the main pathways of NO production is stimulated by ATP released from red blood cells (RBCs).53 There have been reports that state the release of ATP from RBCs following the exposure to mechanical stress, low oxygen levels, β-adrenergic receptor agonist and prostacyclin analogs.49, 52–54 Evidence shows that the ATP derived NO release from endothelial cells may play a key role in vasodilation.55 Furthermore, Sprague and Ellsworth have also been able to link RBC-derived ATP and the activation of purinergic receptors on the endothelium, which can result in the production of NO.54 To enable the quantitation of endothelial derived NO in this module, we first cultured endothelial cells using removable fibrous inserts. The use of fibrous inserts serves to create a 3-D cell culture mimicking the in vivo environment more accurately.25, 56 Two-dimensional cell cultures do not take the natural 3D environment of the cells adequately into account and often issues arise with the growth media and cell expansion.27, 57 Cell cultures created within a scaffold are more relevant to cell models and can better simulate the living organism along with the integration to flow.58, 59 The scaffold here, was created using electrospun polystyrene fibers on a polystyrene film, which is then laser cut as we have demonstrated in a previous report.60 With the insert protocol, the cells were first cultured on the fibrous inserts in a petri dish (6 inserts), which were then plugged in the fluidic cell culture module one at a time for analysis. Prior to analysis, one of the 6 inserts was removed from the petri dish to examine under the microscope for quality control using staining procedures, such as acridine orange, as seen in Figure 5A. Furthermore, the inserts were examined using SEM before and after cell culturing as seen in Figure 5B and C. Also, after the analysis, the inserts can be removed easily for subsequent studies such as cell counting (as was done here after cell lysis).

Figure 5.

Endothelial cells on the fibers. (A) 10 X magnification fluorescent image using acridine orange. Here the bright dots are the endothelial cells. (B) SEM image of fibers only on the insert. (C) SEM image of endothelial cells on the fibers.

The three modules were connected in the order of sample injection, cell culture and finally the WJE detection module, as seen in Figure 6A. For the cell studies, a larger rotor groove volume was used (1.8 µL), demonstrating the ability to customize these module parts with 3D printing. An injection plug of 50 µM ATP (made in HBSS solution) was delivered to the endothelial cells using the 3-D printed sample injection module, after which, a near real-time detection of NO using the WJE device with the modified gold pillar electrode was accomplished. As a control, HBSS (without ATP) injections were also conducted. The average NO concentration observed after the 50 µM ATP injection was 29 ± 5.3 µM (n = 27, 3 inserts analyzed each day on 9 different days). After a detection, the insert with endothelial cells on them was removed for cell quantitation so that the detected NO amount can be normalized to NO release per cell. The cells were simply lysed in DI water to release DNA, which was subsequently quantitated with the Hoechst assay.25 With this method it was found that there were on average 1.53 ± 0.11 × 105 cells per insert. By combining the results, it can be calculated that an average of 0.19 ± 0.03 nM NO was released per cell under 50 µM ATP stimulation. As a comparison, with the HBSS only injection, no signal was detected (Figure 6B).

It has been reported that N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME) can inhibit endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS).61, 62 To validate if our 3-module system can perform an inhibition measurements, we first incubated the cells cultured on the inserts with 100 µM L-NAME for 1 hour or 2 hours. After that, cell confluency on the inserts was double checked with a microscope. Next, the same ATP stimulation was applied to the cells. As can be seen in Figure 6B, significant NO release inhibition was seen in the control studies. Cell inserts incubated with L-NAME for 2 hours resulted in no observed detectable signal after the 50 µM ATP injection (n = 18, 2 inserts analyzed each day on 9 different days). Cells incubated with L-NAME for 1 hour gave an average NO concentration of 3.1 ± 0.7 µM after the 50 µM ATP injection (n = 27, 3 inserts analyzed each day on 9 different days). With an average cell count of 1.54 ± 0.14 × 105 cells per insert, NO released per cell is 0.02 ± 0.004 nM/cell, indicating a L-NAME mediated decrease in NO release by approximately 88% (as expected). With the insert-based cell culture module, we could just switch insert with cell of different treatments without making new devices, which can make such a study more efficiently. Overall, this 3-modular microfluidic system enables flexible cell culture, discrete stimulant delivery without using external tubing/capillaries, and sensitive near real-time NO quantitation.

Conclusion

In this work, we have demonstrated the use of modules fabricated using 3-D printing technology to quantitate the amount of NO released from endothelial cells following ATP stimulation. The modules incorporated include a sample injection, cell culture and detection modules, connected via threaded ports directly eliminating the use of capillaries and other connection fittings. The detection module followed the WJE design optimized for NO detection by electrode modifications (addition of a gold pillar, platinum black and nafion) to the 100 µm gold electrode, offering increased sensitivity and selectivity for the analyte. The sample injection module created by 3-D printing is a simple rotor device capable of the introduction of a defined sample volume into the buffer system. This module is not only a cheaper alternative to commercially available 4-Port injection valve but can be customized for varying injection volumes and offers reduced dead volume issues through the designed threaded ports incorporated for direct assembly to the other modules. Lastly, the cell culture module incorporates the use of fibrous inserts where cells can be cultured to create a 3-D cell culture offering a realistic mimic of the in vivo environment. The modular approach demonstrates the ability to create custom and modifiable components that can be easily assembled, increasing the robustness and flexibility of the system. Once optimized, one can envision printing totally integrated devices containing each module if desired. Furthermore, we feel confident that with the ease of sharing the CAD designs of our devices and our robust characterization/ optimization of each module, this setup can also be used for other biological/ physiological studies in other laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Award Number R15GM084470–04) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Gross BC, Erkal JL, Lockwood SY, Chen C and Spence DM, Anal. Chem, 2014, 86, 3240–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen C, Mehl BT, Munshi AS, Townsend AD, Spence DM and Martin RS, Anal. Methods, 2016, 8, 6005–6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rengier F, Mehndiratta A, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Zechmann CM, Unterhinninghofen R, Kauczor H-U and Giesel FL, Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg, 2010, 5, 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein GT, Lu Y and Wang MY, World Neurosurg, 2013, 80, 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathieson JS, Rosnes MH, Sans V, Kitson PJ and Cronin L, Beilstein J. Nanotechnol, 2013, 4, 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun K, Wei T-S, Ahn BY, Seo JY, Dillon SJ and Lewis JA, Adv. Mater, 2013, 25, 4539–4543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shallan AI, Smejkal P, Corban M, Guijt RM and Breadmore MC, Anal. Chem, 2014, 86, 3124–3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li MW, Bowen AL, Batz NG and Martin RS, Lab on a Chip Technology, Part II: Fluid Control and Manipulation, Caister Academic Press, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.García CD and Henry CS, Anal. Chem, 2003, 75, 4778–4783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hulvey MK, Frankenfeld CN and Lunte SM, Anal. Chem, 2010, 82, 1608–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nge PN, Rogers CI and Woolley AT, Chem. Rev, 2013, 113, 2550–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Daou A, Truong TM, Bertram R and Roper MG, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab, 2011, 301, E742–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen AL and Martin RS, Electrophoresis, 2010, 31, 2534–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson AS, Mehl BT and Martin RS, Anal. Methods, 2015, 7, 884–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selimovic A and Martin RS, Electrophoresis, 2013, 34, 2092–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munshi AS and Martin RS, Analyst, 2016, 141, 862–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paydar OH, Paredes CN, Hwang Y, Paz J, Shah NB and Candler RN, Sens. Actuators, A, 2014, 205, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Au AK, Bhattacharjee N, Horowitz LF, Chang TC and Folch A, Lab Chip, 2015, 15, 1934–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sochol RD, Sweet E, Glick CC, Venkatesh S, Avetisyan A, Ekman KF, Raulinaitis A, Tsai A, Wienkers A, Korner K, Hanson K, Long A, Hightower BJ, Slatton G, Burnett DC, Massey TL, Iwai K, Lee LP, Pister KSJ and Lin L, Lab on a chip, 2016, 16, 668–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KG, Park KJ, Seok S, Shin S, Kim DH, Park JY, Heo YS, Lee SJ and Lee TJ, RSC Adv, 2014, 4, 32876–32880. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Chen C, Summers S, Medawala W and Spence DM, Integr. Biol, 2015, 7, 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiel VE and Audus KL, Antioxid. Redox. Signal, 2001, 3, 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bian K, Doursout MF and Murad F, J. Clin. Hypertens , 2008, 10, 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacher P, Beckman JS and Liaudet L, Physiol. Rev, 2007, 87, 315–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C, Townsend AD, Sell SA and Martin RS, Anal. Methods, 2017, 9, 3274–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Justice BA, Badr NA and Felder RA, Drug Discov. Today, 2009, 14, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edmondson R, Broglie JJ, Adcock AF and Yang L, Assay Drug Dev. Technol, 2014, 12, 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE and Chaudhuri G, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci , 1987, 84, 9265–9269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furchgott RF and Zawadzki JV, Nature, 1980, 288, 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubanyi GM, Romero JC and Vanhoutte PM, Am. J. Physiol, 1986, 250, H1145–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer RM, Ashton DS and Moncada S, Nature, 1988, 333, 664–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratsys 3D Printers. Materials, http://www.stratasys.com/materials, (accessed April 8, 2018).

- 33.Lee Y, Oh BK and Meyerhoff ME, Anal. Chem, 2004, 76, 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin JH, Privett BJ, Kita JM, Wightman RM and Schoenfisch MH, Anal. Chem, 2008, 80, 6850–6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim Y-J, Sah RLY, Doong J-YH and Grodzinsky AJ, Anal. Biochem, 1988, 174, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.<j/>Malinski T, Mesaros S and Tomboulian P, Nitric oxide measurement using electrochemical methods, Academic Press, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Privett BJ, Shin JH and Schoenfisch MH, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2010, 39, 1925–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas DD, Liu X, Kantrow SP and Lancaster JR, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 2001, 98, 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X, Miller MJS, Joshi MS, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Clark DA and Lancaster JR, J. Biol. Chem, 1998, 273, 18709–18713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bryan NS and Grisham MB, Free Radic. Biol. Med, 2007, 43, 645–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kojima H, Nakatsubo N, Kikuchi K, Kawahara S, Kirino Y, Nagoshi H, Hirata Y and Nagano T, Anal. Chem, 1998, 70, 2446–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griveau S, Dumézy C, Séguin J, Chabot GG, Scherman D and Bedioui F, Anal. Chem, 2007, 79, 1030–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Analytical Electrochemistry, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gileadi E, Physical Electrochemistry: Fundamentals, Techniques and Applications, WILEY-VCH, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feltham AM and Spiro M, Chem. Rev, 1971, 71, 177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilic B, Czaplewski D, Neuzil P, Stanczyk T, Blough J and Maclay GJ, J. Mater. Sci, 2000, 35, 3447–3457. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sherstyuk OV, Pron’kin SN, Chuvilin AL, Salanov AN, Savinova ER, Tsirlina GA and Petrii OA, Russ. J. Electrochem, 2000, 36, 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee Y, Yang J, Rudich SM, Schreiner RJ and Meyerhoff ME, Anal. Chem, 2004, 76, 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flammer AJ and Luscher TF, Swiss Med. Wkly, 2010, 140, w13122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kristensen EW, Kuhr WG and Wightman RM, Anal. Chem, 1987, 59, 1752–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmerman JB and Wightman RM, Anal. Chem, 1991, 63, 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heller R, Unbehaun A, Schellenberg B, Mayer B, Werner-Felmayer G and Werner ER, J. Biol. Chem, 2001, 276, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sprague RS, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML, Keller C and Lonigro AJ, Exp. Biol. Med, 2001, 226, 434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sprague RS and Ellsworth ML, Microcirculation, 2012, 19, 430–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crecelius AR, Kirby BS, Richards JC, Garcia LJ, Voyles WF, Larson DG, Luckasen GJ and Dinenno FA, Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol, 2011, 301, H1302–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen C, Townsend AD, Hayter EA, Birk HM, Sell SA and Martin RS, Anal. Bioanal. Chem, 2018, 410, 3025–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shamir ER and Ewald AJ, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol, 2014, 15, 647–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sell S, Barnes C, Smith M, McClure M, Madurantakam P, Grant J, McManus M and Bowlin G, Polym. Int, 2007, 56, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang F, Murugan R, Ramakrishna S, Wang X, Ma YX and Wang S, Biomaterials, 2004, 25, 1891–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen C, Townsend AD, Hayter EA, Birk HM, Sell SA and Martin RS, Anal. Bioanal. Chem, 2018, DOI: 10.1007/s00216-018-0985-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murohara T, Witzenbichler B, Spyridopoulos I, Asahara T, Ding B, Sullivan A, Losordo DW and Isner JM, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 1999, 19, 1156–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfeiffer S, Leopold E, Schmidt K, Brunner F and Mayer B, Br. J. Pharmacol, 1996, 118, 1433–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.