Abstract

We examined college student reactions to a statewide public smoke-free policy, campus policies and private restrictions through an online survey among 2260 students at a 2-year college and a university and 12 focus groups among smokers. Among survey participants, 34.6% smoked in the past month (35.0% daily, 65.0% non-daily). Correlates of receptivity to public policies included attending the university, not living with smokers and non-smoker status (versus daily and non-daily smoking). Correlates of receptivity to outdoor campus policies included being a university student, unmarried, without children, from homes where parents banned indoor smoking and a non-smoker. Correlates of having home restrictions included not living with smokers, no children, parents banning indoor smoking and non-smoker status. Correlates of having car restrictions included attending the university, not living with smokers, having children, parents banning indoor smoking and non-smoker status. Qualitative findings indicated support for smoke-free policies in public (albeit greater support for those in restaurants versus bars) and on campus. Participants reported concern about smokers’ and bar/restaurant owners’ rights, while acknowledging several benefits. Overall, 2-year college students and smokers (non-daily and daily) were less supportive of smoke-free policies.

Introduction

Over 18 million students are enrolled in colleges and universities in the United States [1]. During college, many people experiment with or initiate smoking and one-third become addicted [2, 3]. Although pro-tobacco marketing attempts to normalize smoking particularly among young adults [4], smoke-free policies make smoking less socially acceptable [5–8]. Unfortunately, 83% of students reported any secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure in the past week, with exposure being most common in restaurants or bars or in personal settings (i.e. homes, cars) (38%) [9]. Thus, it is important to examine college student reactions to smoke-free policies in public places and on campuses as well as the practice of implementing private restrictions.

Firstly, assessing student reactions to public smoke-free policies is important in understanding their attitudes regarding tobacco control. In October 2007, Minnesota implemented a statewide smoking ban, the Freedom to Breathe Act. This law is applied to all public places, including bars, restaurants, private clubs, bowling alleys, hotel lobbies and public transportation. Minnesota was preceded by 22 other states, Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico in passing such a policy. Greater support for smoke-free policies has been associated with being female [10, 11], higher education and higher income [10–13]. Among smokers, support for these policies is related to greater intent to quit and lower cigarette consumption [14]. The current investigation examines student reactions to the Minnesota ban.

Secondly, it is critical to understand college student reactions to campus policies. Although restrictive smoking policies on college campuses may discourage smoking onset or facilitate cessation, many colleges and universities are reluctant to establish them for fear of student objections [15]. A 2003 national study [16] indicated that 54% of the colleges banned smoking in all campus buildings and student residences [17]. Most students (88% of never smokers and 58% of smokers) favor smoke-free indoor policies, with less support for outdoor policies (43% of never smokers and 7% of smokers). Interestingly, the vast majority (98% of never smokers and 82% of smokers) indicates that the right to breathe clean air should take priority over the right to smoke [15]. Other research has corroborated these findings [18]. Central to the current study, this study examines reactions to current policies on two campuses that have not established outdoor smoke-free policies but are exploring that possibility, as endorsed by several national organizations, including the American College Health Association.

Third, it is important to understand how college students approach tobacco control and the management of SHS exposure in their personal settings, such as their homes and cars. This is especially relevant given that public smoke-free policies may increase implementation of private restrictions [19]. Having home restrictions is associated with lower reported levels of smoking and less SHS exposure [20]. Furthermore, having restrictions is associated with recent quit attempts [21], quitting smoking [22] and preventing relapse [23, 24]. Less is known about the impact of having restrictions in vehicles. Thus, research is needed to examine this area.

Rates of non-daily smoking have increased alongside a national decline in daily tobacco consumption [25, 26]. While non-daily smoking has been viewed as an unstable condition between daily smoking and quitting, newer research shows that this pattern of tobacco use may represent a chronic low-level (≤10 cigarettes per day) form of consumption [27–29]. This group represents a wide range of smoking patterns among the general population and particularly among college students [30]. The young adulthood population has been particularly affected [25]. This change may have occurred as a result of a rise in tobacco control policies [25, 28]. Smokers enforcing smoke-free policies at home are much more likely to be light or intermittent smokers [25]. Thus, it is critical to examine how daily versus non-daily smokers respond to smoke-free policies.

Another interesting factor to consider in relation to attitudes regarding tobacco control policies is type of post-secondary education pursued. Two-year college and university students differ in their sociodemographic characteristics, as well as their smoking behaviors and attitudes. Two-year college students are more likely to be female, older, married and employed [31]. After controlling for sociodemographics, attending a 2-year college predicts smoking [31]. Moreover, 2-year college students have more positive attitudes regarding smoking; specifically, they are more open to relationships with smokers, less concerned about smoking-related health consequences and less supportive of tobacco control policies (e.g. tax increases, restricting tobacco marketing) [32]. Thus, these differences in attitudes toward smoke-free policies among technical college students and university students may be critical in developing effective intervention strategies for the two settings.

Given the aforementioned literature, the purpose of this study was to examine college student attitudes regarding public and campus smoke-free policies, implementation of private policies and specific factors related to reactions to smoke-free policies among students at a 2-year college and a 4-year university.

Materials and methods

Our mixed-methods approach utilized a quantitative survey and focus groups to examine college student reactions to public, campus and private smoke-free policies. This research was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB# 0712S22941).

Survey research

In October 2008, a random sample of 5500 undergraduate students at a 4-year university (yielded from a random number generator and the list of student e-mails) and all 3334 young adults at a technical college were invited to complete an online survey. Students received up to three e-mails containing a link to the consent form with the option of declining participation. Students who consented were directed to the survey. As an incentive for participation, participants were entered into a drawing for cash prizes of $2500, $250 and $100 at each school.

Of those invited to participate, 2700 (30.6%) completed the survey (technical college: 30.1%, N = 1004; university: 30.8%, N = 1696). This response rate approximates response rates previously found using an online administration among college students [33, 34]. Moreover, Internet surveys yield similar statistics regarding health behaviors compared with mail and phone surveys despite yielding lower response rates [35]. The present study focused on students aged 18–25 years; thus, 2260 (748 technical colleges and 1512 university students) are included in these analyses. Although we cannot assume that our sample is representative of the student populations present within the college settings, preliminary analyses indicated that gender, age and ethnic representations were not significantly different from the overall student body populations.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics assessed included age, gender, ethnicity and parental educational attainment.

Social factors.

We assessed marital status, place of residence (i.e. whether living with parents or elsewhere) and other smokers living in the home, children living in the home, parental home smoking rules and whether parents smoked.

Smoking behaviors.

Participants were asked, ‘In the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke a cigarette (even a puff)?’ and ‘On the days that you smoke, how many cigarettes do you smoke on average?’ These questions have been used in previous research and have been shown to be reliable and valid with similar populations [36, 37]. Students reporting smoking ≥1 day in the past 30 days were considered current smokers. For the multivariate analyses, smokers were further categorized into non-daily smokers (i.e. smoked between 1 and 29 days in the past 30 days) and daily smokers (i.e. smoked every day of the past 30 days) [38–40]. Among smokers, we assessed readiness to quit smoking in the next 30 days.

Attitudes regarding public smoke-free policies.

Participants were asked, ‘Because of the public smoking ban on smoking in restaurants and bars, do you go out more, less or does it make no difference?’ (1 = ‘less’, 2 = ‘no difference’, 3 = ‘more’) [41]. We asked, ‘How important is it to you to have a smoke-free environment inside bars, lounges, clubs and restaurants?’ using a four-point Likert-type scale (1 = ‘not at all important’ to 4 = ‘very important’) [42]. We also asked, ‘How do you feel about the law prohibiting smoking in all public buildings and restaurants?’ and ‘How do you feel about smoking being prohibited in Minnesota bars?’ using a four-point Likert-type scale (1 = ‘disapprove strongly’ to 4 = ‘approve strongly’) [42]. Exploratory factor analysis identified a common underlying factor among these items. Thus, the responses to these four questions were added to develop an overall score indicating level of receptivity to public smoke-free policies and demonstrated internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86).

Attitudes about campus smoking policies.

Participants were asked, ‘What effect, if any, do you think a policy making this campus completely smoke-free would have on: student quality of life, student learning and student enrollment?’ using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = ‘extremely negative’ to 5 = ‘extremely positive’) [43]. Exploratory factor analysis identified a common underlying factor among these items. Thus, the responses to these three questions were added to develop an overall score indicating level of receptivity to campus smoke-free policies and demonstrated internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86).

Private smoking policies.

Participants were asked, ‘Which of the following best describes the rules about smoking in your home?: (i) no one is allowed to smoke anywhere, (ii) smoking is allowed in some places or at some times, or (iii) smoking is permitted anywhere; there are no rules’ [44]. This question was adapted to examine rules in cars; participants were asked which statement best describes the rules about smoking in their cars with the same response options as well as an option stating ‘I do not own a car’. These variables were dichotomized as complete restrictions versus other (partial or no restrictions).

Data analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted examining differences between schools, genders and smoking status. Ordinary least squares regression was used to examine correlates of receptivity to public and campus policies, and binary logistic regression was used to determine correlates of implementation of private restrictions. Variables with a statistically significant bivariate relation to the outcomes of interest at P < 0.05 were entered into the models; using backwards stepwise entry, factors significantly contributing to the models at α = 0.05 were allowed to remain in the model. PASW 17.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses.

Focus group research

In Spring 2009, we conducted 12 in-person focus groups with 73 college student smokers (i.e. any smoking in the past 30 days) aged 18–25 years recruited from the online survey. Focus group participants were recruited from those who completed the online survey the prior semester and indicated that they had smoked in the past 30 days. For each group, approximately 30 participants were invited to participate via telephone and e-mail. As an incentive, participants received $50. Participants were recruited into 1 of 12 groups (ranging from 6 to 12 participants per group), each being homogenous in gender (male and female) and school (2-year college, university; i.e. three groups per stratum).

Prior to beginning the focus groups, participants read and signed an informed consent and completed a brief questionnaire assessing demographics and smoking behavior using questions similar to those described above.

A trained focus group moderator (the lead author) facilitated group discussion on (i) attitudes about the statewide smoking ban, (ii) reactions to current campus policies and the potential implementation of outdoor smoke-free policies and (iii) the implementation of restrictions in private spaces (within the home or car). Each session lasted 90 min. All sessions were audiotaped, transcribed and observed by a research assistant.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed according to the principles outlined in Morgan and Krueger [45]. NVivo 7.0 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used for text coding and to facilitate the organization, retrieval and systematic comparison of data. Transcripts were independently reviewed by the first author and two master of public health graduate students to generate preliminary codes. They then refined the definition of primary (i.e. major topics explored) and secondary codes (i.e. recurrent themes within these topics) and independently coded each transcript. The independently coded transcripts were compared, and consensus for coding was reached. Quantitative data from the focus group surveys were analyzed using PASW 17.0 (IBM).

Results

Survey research

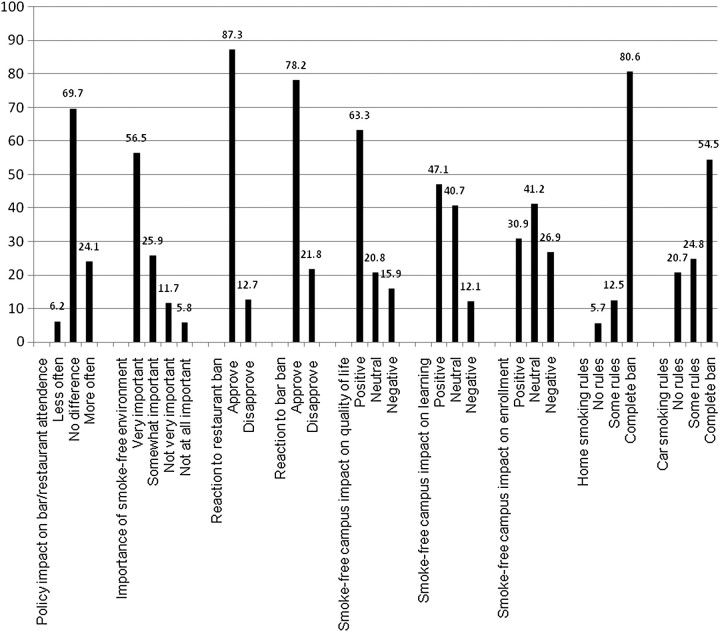

Table I provides survey participant characteristics as well as bivariate analyses comparing 2-year college and university students and males and females. Results of individual questions regarding receptivity to public and campus policies and implementation of private restrictions are presented in Fig. 1.

Table I.

Survey participant characteristics and attitudes regarding smoke-free policies

| Variable | Total, N (%) or mean (SD) | 2-Year college, N (%) or mean (SD) | University, N (%) or mean (SD) | P |

| N | 2260 (100.0) | 748 (33.1) | 1512 (66.9) | — |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age (SD) | 20.38 (1.89) | 20.24 (1.93) | 20.44 (1.86) | 0.02 |

| Female (%) | 1400 (61.9) | 499 (66.7) | 901 (59.6) | 0.001 |

| Two-year college (%) | 748 (33.1) | — | — | — |

| Non-Hispanic White (%) | 1935 (85.5) | 704 (93.9) | 1231 (81.4) | 0.001 |

| Parental education ≥ bachelors (%) | 861 (38.1) | 172 (22.9) | 689 (45.7) | <0.001 |

| Married/living with/partner (%) | 475 (21.0) | 231 (30.8) | 244 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Smoker living in home (%) | 834 (37.3) | 323 (43.5) | 511 (34.2) | <0.001 |

| Children in the home (%) | 382 (17.1) | 178 (24.0) | 204 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| Parents allow smoking in home (%) | 422 (18.9) | 195 (26.2) | 227 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Parents smoked in home (%) | 908 (40.7) | 363 (49.1) | 545 (36.6) | <0.001 |

| Smoking variables | ||||

| Days smoked in past 30 days (SD) | 5.88 (10.77) | 8.36 (12.53) | 4.65 (9.54) | <0.001 |

| Average cpd (SD) | 4.96 (4.88) | 5.99 (5.42) | 4.27 (4.36) | <0.001 |

| Smoked in the past 30 days (%) | 781 (34.6) | 317 (43.5) | 466 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Daily smokers (%) | 273 (12.2) | 149 (19.9) | 125 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Non-daily smokers (%) | 508 (22.5) | 168 (22.5) | 341 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Ready to quit in next 30 days (%) | 230 (31.5) | 83 (27.1) | 147 (34.7) | 0.030 |

| Smoking restrictions | ||||

| Receptivity to public policies (SD) | 12.29 (2.76) | 11.83 (2.87) | 12.53 (2.67) | <0.001 |

| Receptivity to campus ban (SD) | 10.50 (3.01) | 10.10 (2.81) | 10.69 (3.09) | <0.001 |

| Complete home ban (%) | 1°825 (81.3) | 595 (80.0) | 1°230 (82.0) | 0.14 |

| Complete car ban (%) | 1°196 (53.4) | 340 (45.8) | 856 (57.1) | <0.001 |

cpd, Cigarettes per day.

Fig. 1.

Percent of students reporting reactions to public policies, campus policies and private policies.

We examined correlations among our outcomes of interest, which are as follows: receptivity to public policies and to campus policies: r = 0.58, P < 0.001; receptivity to public policies and implementing home smoking restrictions: r = 0.31, P < 0.001; receptivity to public policies and implementing car smoking restrictions: r = 0.46, P < 0.001; receptivity to campus policies and implementing home smoking restrictions: r = 0.19, P < 0.001; receptivity to campus policies and implementing car smoking restrictions: r = 0.42, P < 0.001 and implementing home smoking restrictions and car smoking restrictions: r = 0.27, P < 0.001.

Attitudes regarding policies differed by gender, type of school and smoking status (see Table I). Females, in comparison to males, were more receptive to public and campus policies and were more likely to have restrictions in their homes. Two-year college students were less receptive to public and campus policies and were less likely to have restrictions in their cars. Smokers, in comparison to non-smokers, were less receptive to public and campus policies and less likely to have restrictions in their homes or cars.

Multivariate analyses

Correlates of receptivity to public smoke-free policies.

Correlates of receptivity to public smoke-free policies included being older, being female, attending a university, being from an ethnic minority background, not living with smokers and being a non-smoker versus a non-daily smoker or a daily smoker (Table II).

Table II.

Regression models predicting reactions to smoke-free policies in public, on campus and in private spaces

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI | P |

| Receptivity to public policies | |||

| Constant | 10.83 | 9.72, 11.94 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.11 | 0.05, 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.00 | 0.80, 1.21 | <0.001 |

| Two-year college | −0.18 | −0.40, 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Married/living with partner | −0.25 | −0.50, 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Other smokers in home | −0.59 | −0.81, −0.38 | <0.001 |

| Children in home | −0.29 | −0.55, −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Parents allowed smoking in home | −0.48 | −0.74, −0.23 | <0.001 |

| Non-daily smoker | −1.60 | −1.84, −1.36 | <0.001 |

| Daily smoker | −3.73 | −4.05, −3.41 | <0.001 |

| Receptivity to campus policies | |||

| Constant | 10.45 | 9.18, 11.73 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.02, 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Female | 0.73 | 0.50, 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | −1.14 | −1.47, −0.81 | <0.001 |

| Other smokers in home | −0.70 | −0.94, −0.45 | <0.001 |

| Non-daily smoker | −1.69 | −1.97, −1.41 | <0.001 |

| Daily smoker | −3.21 | −3.58, −2.85 | <0.001 |

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Private policies | |||

| Smoke-free home | |||

| Age | 1.08 | 1.01, 1.55 | 0.02 |

| Female | 1.92 | 1.49, 2.44 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.96 | 1.43, 2.70 | <0.001 |

| Other smokers in home | 0.39 | 0.31, 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Children in home | 1.72 | 1.20, 2.44 | 0.003 |

| Parents allowed smoking in home | 0.23 | 0.18, 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Non-daily smoker | 0.42 | 0.32, 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Daily smoker | 0.24 | 0.17, 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Smoke-free car | |||

| Two-year college | 0.79 | 0.64, 1.00 | 0.04 |

| Other smokers in home | 0.47 | 0.37, 0.58 | <0.001 |

| Children in home | 1.33 | 1.01, 1.79 | 0.04 |

| Parents allowed smoking in home | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.88 | 0.002 |

| Smoked in past 30 days | 0.13 | 0.11, 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Daily smoker | 0.05 | 0.03, 0.07 | <0.001 |

Correlates of receptivity to campus smoke-free policies.

In the multivariate model predicting receptivity to campus smoke-free policies (Table II), correlates included older age, being female, attending a university, not being married or living with a partner, not having children in the home, parents banning smoking in their home and being a non-smoker versus a non-daily smoker or a daily smoker.

Correlates of smoke-free policies in the home and car.

In the multivariate model predicting having complete home smoking restrictions (Table II), correlates included being older, being female, being non-Hispanic White, not living with other smokers, having children in the home, parents banning smoking in the home and being a non-smoker versus being a non-daily smoker or a daily smoker. Independent correlates of having complete car smoking restrictions included attending a university, not living with other smokers, having children in the home, parents banning smoking in the home and being a non-smoker versus a non-daily smoker or a daily smoker.

Focus group research

Table III provides the demographics and smoking-related characteristics of research participants by gender and type of school attended. Table IV highlights the themes that emerged in the discussion.

Table III.

Focus group participant characteristics

| Variable | Total, N (%) or mean (SD) | 2-Year college, N (%) or mean (SD) | University, N (%) or mean (SD) | P |

| N | 73 | 36 | 37 | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age (SD) | 20.6 (1.8) | 20.7 (1.8) | 20.5 (1.8) | 0.58 |

| Female (%) | 41 (56.2) | 18 (50.0) | 23 (62.2) | 0.21 |

| Two-year college (%) | 36 (49.3) | — | — | — |

| Non-Hispanic White (%) | 65 (92.9) | 34 (52.3) | 31 (86.1) | 0.03 |

| Parental education ≥ bachelors (%) | 28 (38.4) | 8 (22.2) | 20 (54.1) | 0.01 |

| Married or living with partner (%) | 18 (24.7) | 11 (30.6) | 7 (18.9) | 0.19 |

| Any children in the home (%) | 16 (21.9) | 10 (27.8) | 6 (16.2) | 0.18 |

| Smoking variables | ||||

| Days smoked in past 30 days (SD) | 13.4 (12.9) | 14.6 (12.5) | 12.3 (13.2) | 0.45 |

| Average cpd (SD) | 4.2 (5.0) | 4.9 (5.5) | 3.5 (4.4) | 0.24 |

| Smoked ≥25 days of past 30 days (%) | 24 (32.9) | 12 (33.3) | 12 (32.4) | 0.57 |

| Complete home ban (%) | 34 (47.2) | 15 (41.7) | 19 (52.8) | 0.24 |

| Complete car ban (%) | 16 (22.9) | 5 (14.3) | 11 (31.4) | 0.08 |

cpd, Cigarettes per day.

Table IV.

Reactions to smoking policies in public, on campus and in private spaces

| Topic | Quote |

| Reactions to public smoke-free policies | |

| Positive reactions | |

| Reduced smoking level | When you're drunk in a bar, you want to smoke constantly. When you have to go outside to smoke, you won't smoke as much. |

| Prevents exposure to SHS | In my opinion, if you want to kill yourself, go right ahead. Don't do it to others. If you can, stay away from people who don't smoke, or children especially. |

| Appreciate not having smoke and smell | Going out is more enjoyable. Especially in restaurants, I often wonder if smokers even realizes how annoying it is when you're trying to eat and smoke is all around you. It's really uncomfortable, and I didn't like it. Now it's much more enjoyable. |

| Quick acclimation to law | A lot of places are just adjusting. Places are making an outdoor smoking areas. You can go out and it's actually warm. People will adjust, and it will be fine again. |

| Benefits bars/restaurants that favor smoke-free policies | There were businesses that would not allow smoking because they care about their customers and didn't want them exposed to smoke. But then they would lose business, where the other bars would say, ‘Smoke, we don't care.’ Now it makes it a more fair because you're not punished for caring about your customers. |

| Concerns | |

| Concern about economic impact and infringement of rights of bar/restaurant owners | I think it should be the owner's decision if they want to do enforce a smoking ban. I don't like the fact that it's a law now because that's one more thing making us more communistic versus democratic. |

| Concern about smokers’ rights | It shouldn't be inconvenient—it's an inconvenience for us to have to go outside, but it's also an inconvenience for others to have to smell smoke and inhale it. |

| Difference between bars and restaurants in acceptability of ban | In family-oriented places, it's perfectly acceptable to ask people not to smoke. But like everyone else said, in the bar scene, don't complain. |

| Reactions to campus policies | |

| Positive reactions | |

| Reduced smoking level | It actually helps me if I want to smoke and I'm in school because I have to walk over there, so I say, ‘Never mind, I'll stay here.’ |

| Protects non-smokers | I don't think they should be allowed to smoke anywhere, so I think it's nice that they accommodated for those people that do smoke. |

| Cleaner campus | You walk around and see the butts everywhere. People just get lazy, and you'll see a pile of butts sitting next to the ashtray. They can't even put them in the ashtrays. It's just a nuisance; it just takes away from the look of the campus. |

| Concerns | |

| Concern about burden of policies on smokers | Once in a while it kind of gets annoying not being able to go out the door and smoke where my friends are, but then I guess some times it's a good thing. |

| Concern about enforcement of policies | The rules could be enforced better, but they're fair. They probably just need to post someone outside of the library, post someone outside a couple of the doors… |

| Private smoke-free policies | |

| Major motivators | |

| Protecting others from SHS exposure | It's not healthy to inhale it, for non-smokers and smokers. A lot of times, you're re-breathing in the smoke that you just let out, and you're in a confined area. |

| Maintaining a clean, smell-free space | Old cigarette smoke in somebody's house is just so gross. Your clothes and everything just smell like an ash tray and that's really gross. |

| Impact of parental rules | My mom used to smoke, and we used to have to clean the walls. It was disgusting. I don't ever smoke inside because of that. My mom smokes in the house and didn't care where I smoked. It would really help if your parents taught you not to smoke and actually got mad when they found out. |

Public smoke-free policies

Among this sample of college student smokers, there was a high level of support for the public policy. Participants reported support for the ban for several reasons, including that the policy (i) reduced their smoking levels, (ii) protected people from SHS exposure; (iii) demonstrated respect for the rights of others, (iv) promoted freedom from smoke and smell, (v) was quickly acclimated to by the general public and bar and restaurant owners and (vi) allowed bars and restaurant owners who favored smoke-free policies to implement them without risk of substantially losing business. Participants indicated concern about the rights of smokers and bar and restaurant owners, particularly the economic impact that the policy may have on these businesses. They also reported more support for the ban in restaurants versus the ban in bars.

Campus smoking policies

At the 2-year college, campus policies included an indoor smoking ban and smoking being allowed only in designated areas outdoors. At the university, campus policies included indoor smoke-free policies and smoking at least 20 feet from all building entrances. Reported benefits of these policies included that it (i) helped to reduce smoking, (ii) protected non-smokers and (iii) improved the cleanliness of the campus. Concerns included the burden these policies imposed on smokers and difficulty enforcing these rules. Participants were largely receptive to implementing an outdoor smoke-free policy but reported concern about its impact on smokers living on campus and its impact on enrollment.

Smoking in private spaces

In regard to home smoking restrictions, the majority of participants had complete restrictions and the majority of the remaining participants had at least partial restrictions (see Table III). In regard to restrictions in cars, half of the focus group participants had complete restrictions. The major motivators for implementing smoke-free policies included protecting others from SHS exposure and maintaining a clean smell-free space. Many participants commented on whether their parents had smoking restrictions, with mixed results regarding how they impacted their own implementation of restrictions.

Discussion

The current study describes college student reactions to smoke-free public policies and campus policies and implementation of private smoking restrictions. College students largely support smoke-free policies in public, on campus and in private spaces. As has been documented in prior research, those who were older [11, 13, 46–49], female [10, 11, 50] and non-smokers [10, 11, 50] were more receptive to smoke-free policies in all three domains.

Our findings indicated that non-smokers were more receptive to smoke-free policies and more likely to implement personal restrictions (in homes and cars) than non-daily smokers and that non-daily smokers were more receptive to smoke-free policies and more likely to implement personal restrictions than daily smokers. Thus, current findings confirm and extend research documenting that non-smokers have more positive attitudes about smoke-free policies [10, 11, 50] and that smokers who enforce smoke-free policies at home have nearly three times the odds of being a light or intermittent user rather than a daily smoker [25].

In addition, compared with 2-year college students, university students were consistently more receptive to smoke-free policies and were more likely to have smoking bans in their cars. Although this greater receptivity among university students in comparison to 2-year college students has not been previously documented, higher rates of smoking have been found among 2-year college students [31]. Furthermore, it is important to note that parental education level did not contribute significantly to the models. We examined whether forcing parental education into the models would have changed the results; however, doing so did not yield different results. Thus, the differences in student body populations are not solely attributable to socioeconomic status.

Other factors were related to receptivity to public policies; specifically, being married or living with partner, having other smokers in the home, having children in the home and having parents that allowed smoking in the home were associated with more negative attitudes regarding the policies. These findings have not been previously documented; in fact, it seems counterintuitive that those with children in the home would be less receptive. However, it is reasonable that parents allowing smoking in the home may be associated with more negative attitudes regarding smoke-free policies. Interestingly, students were concerned about the impact of the public policy on rights of non-smokers, smokers and bar/restaurant owners. The vast majority recognized the impact of the policies on reducing SHS exposure. Smokers generally approved of the ban because of its impact on reducing smoking; they also continued to go to bars and restaurants despite the new policies. Prior research has documented that businesses, in fact, are not negatively impacted by such bans [51, 52]. Thus, despite concern about the impact of these policies on smokers and other stakeholders, these groups reap some benefit or at least are not significantly harmed by them.

Similar to the reactions to the public ban, participants acknowledged that more restrictive campus policies increase burden on smokers but may ultimately benefit smokers by helping them quit or reduce their smoking. Moreover, participants were also supportive of outdoor smoke-free campus policies. They reported concern about the appearance of their campuses and believed that more smoking restrictions would result in improved campus cleanliness. Despite the challenges faced by campuses to implement tobacco control initiatives [53], receptivity to and compliance with campus policies can be increased by having activities on campus facilitated through campus coalitions [54], increasing enforcement, establishing consequences for non-compliance, improving signage and distributing reminder cards [55]. In addition, receptivity to campus policies was related to being single, not having children and parents not allowing smoking in their home; these relationships have not been previously documented. One explanation is that prior experience with one's family having home smoking restrictions and concern about children being exposed to SHS may make an individual more open to having increased smoking restrictions. In addition, single people may have had more exposure to smoke-free policies in bars that have prepared them to acclimate to campus smoking restrictions. These findings require further examination.

Having home and car smoking restrictions was associated with not having other smokers in the home and having children in the home, which has been previously documented [56]. In addition, coming from homes where parents banned indoor smoking was related to implementing restrictions. Interestingly, parental smoking status was not associated with having private restrictions. Thus, as has been shown previously [57], parental attitudes about smoking may be more important than their smoking behavior. In the focus group discussions, several students reported that they had home smoking restrictions because their parents had restrictions, while others reported having smoking restrictions because they disliked the smell of smoke in the homes where they grew up.

The present study has implications for research and practice. Firstly, the differences found between these student groups may reflect the variability that exists among young adults more broadly. For example, smoking rates for individuals in this age group are highest among young adults who did not finish high school (46%), followed by those who do not attend college (42%), those who attend 2-year colleges (34%) and those who attend 4-year colleges (29%) [58]. Future research is encouraged to target other segments of young adults, such as those not enrolled in college (e.g. those in the workforce or military). In addition, understanding attitudes about smoke-free policies among these groups as well as other psychosocial variables that contribute to different attitudes is critical for developing effective policies for campuses and promoting the implementation of private restrictions.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it included two colleges in the Mid-west, with participants being primarily female and White/Caucasian. Although these characteristics reflect the demographics of the colleges from which the sample was selected, they may not reflect the demographics of all American colleges nor young adults more generally, limiting generalizability. In particular, the fact that these young adults are pursuing college educations might reflect a higher socioeconomic background than direct-to-work young adults; thus, the high rates of support for smoke-free policies might be reflective of the sample's higher socioeconomic background [44, 59, 60]. Also, because information from non-respondents was not assessed, we cannot infer how representative our sample is of the larger student populations. The same can be said of the focus group participants. In addition, we did not assess details regarding the nature of the home dwelling for these college students (i.e. dormitory, apartment, with parents). Thus, the extent to which their home smoking restrictions were volitional was not assessed. For example, the university students who lived in the dormitories were unable to smoke in their homes because of campus policies rather than because they elected to have restrictions. However, additional analyses of only students that lived in off-campus housing on their own (i.e. not with their parents) indicated similar findings, with 579 (55.8%) of 4-year university students and 317 (47.5%) of 2-year college students having complete home smoking restrictions. Furthermore, smoking status was assessed using self-report (i.e. no biochemical verification). However, there is no reason to assume differential rates of biased reporting. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to determine causality.

Conclusions

Technical college students, compared with university students, report less receptivity toward smoke-free policies in public and on campus and less commonly implement private restrictions. Moreover, non-smokers have more positive attitudes about smoke-free policies than non-daily smokers, and likewise, non-daily smokers are more receptive to smoke-free policies than daily smokers. Therefore, tobacco control initiatives should attend to different psychosocial and smoking-related factors that influence attitudes toward smoke-free policies and implementation of private smoking restrictions among 2-year college and university students. Future research should identify other factors that might influence attitudes among these populations and test intervention strategies among these college settings in order to inform smoke-free policies affecting college students.

Funding

ClearWay Minnesota (RC-2007-0024).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Snyder T, Dillow S, Hoffman C. Digest of Education Statistics 2007 (NCES 2008-022) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everett SA, Husten CG, Kann L, et al. Smoking initiation and smoking patterns among US college students. J Am Coll Health. 1999;48:55–60. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Everett SA, Warren CW, Sharp D, et al. Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among us high school students. Am J Prev Med. 1999;29:327–33. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. 2008. NCI tobacco control monograph series, 19. NIH publication; no. 07–6242. Bethesda, MD:U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thrasher J, Swayampakala K, Villalobos V. México: Salud Publica; Differential Impact of Local and Federal Smoke-Free Legislation in Mexico: A Longitudinal Study of Campaign Exposure, Support for Smoke-Free Policies and Secondhand Tobacco Smoke Exposure among Adult Smokers. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigotti N, Lee JE, Wechsler H. US college students’ use of tobacco products: results of a national survey. JAMA. 2000;284:699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown A, Moodie C. The influence of tobacco marketing on adolescent smoking intentions via normative beliefs. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:721–33. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thrasher J. Translating the world health organization's framework convention on tobacco control: policy support, norms and secondhand smoke exposure before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free policy in Mexico City. Aust J Polit Hist. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfson M, McCoy TP, Sutfin EL. College students' exposure to secondhand smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:977–84. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Support for smoke-free policies: a nationwide analysis of immigrants, US-born, and other demographic groups, 1995–2002. Aust J Polit Hist. 2010;100:171–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doucet JM, Velicer WF, Laforge RG. Demographic differences in support for smoking policy interventions. Addict Behav. 2007;32:148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong EK, Tang H, Tsoh J, et al. Smoke-free policies among Asian-American women: comparisons by education status. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:S144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borland R, Yong HH, Siahpush M, et al. Support for and reported compliance with smoke-free restaurants and bars by smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15:iii34–41. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigotti NA, Regan S, Moran SE, et al. Students' opinion of tobacco control policies recommended for US colleges: a national survey. Tob Control. 2003;12:251–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson B, Coronado GD, Chen L, et al. Preferred smoking policies at 30 Pacific Northwest colleges. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:586–93. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin AC, Rigotti NA. US public universities' compliance with recommended tobacco-control policies. J Am Coll Health. 2003;51:181–8. doi: 10.1080/07448480309596349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler H, Kelley K, Seibring M, et al. College smoking policies and smoking cessation programs: results of a survey of college health center directors. J Am Coll Health. 2001;49:205–12. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigotti NA, Moran SE, Wechsler H. US college students' exposure to tobacco promotions: prevalence and association with tobacco use. Aust J Polit Hist. 2004;94:138–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borland R, Yong HH, Cummings KM, et al. Determinants and consequences of smoke-free homes: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15:iii42–50. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman BA, Wong GC, Bastani R, et al. Household smoking behavior and ETS exposure among children with asthma in low-income, minority households. Addict Behav. 2003;28:111–28. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman GJ, Ribisl KM, Howard-Piney B, et al. The relationship between home smoking bans and exposure to state tobacco control efforts and smoking behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 2000;15:81–8. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farkas AJ, Pierce JP, Zhu JP, et al. Addiction versus stages of change models in predicting smoking cessation. Addiction. 1996;91:1271–80. discussion 1281–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilpin EA, White MM, Farkas AJ, et al. Home smoking restrictions: which smokers have them and how they are associated with smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:153–62. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pizacani BA, Martin DP, Stark MJ, et al. A prospective study of household smoking bans and subsequent cessation related behaviour: the role of stage of change. Tob Control. 2004;13:23–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce JP, White MM, Messer K. Changing age-specific patterns of cigarette consumption in the United States, 1992–2002: association with smoke-free homes and state-level tobacco control activity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:171–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking—United States, 1996–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:303–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, et al. Nondaily smokers: who are they? Aust J Polit Hist. 2003;93:1321–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiffman S. Light and intermittent smokers: background and perspective. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:122–5. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. Occasional smoking in a Minnesota working population. Aust J Polit Hist. 1996;86:1260–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutfin EL, Reboussin BA, McCoy TP, et al. Are college student smokers really a homogeneous group? A latent class analysis of college student smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:444–54. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanem JR, Berg CJ, Lawrence C, et al. Differences in tobacco use among two- and four-year college students in Minnesota. J Am Coll Health. 2009;58:151–9. doi: 10.1080/07448480903221376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg CJ, An LC, Thomas JL. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr017. (Under review). Differences in smoking patterns, attitudes, and motives among two-year college and four-year university students. Health Educ Res. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplowitz MD, Hadlock TD, Levine R. A comparison of web and mail survey response rates. Public Opin Q. 2004;68:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford S, McCabe S, Kurotsuchi Inkelas K. Using the Web to Survey College Students: Institutional Characteristics That Influence Survey Quality. Fontainebleau Resort, Miami Beach, FL: American Association For Public Opinion Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.An LC, Hennrikus DJ, Perry CL, et al. Feasibility of Internet health screening to recruit college students to an online smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:S11–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment Spring 2007 reference group data report (abridged) J Am Coll Health. 2008;56:469–79. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance: national college health risk behavior survey—United States, 1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997;46:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment Spring 2008 reference group data report (abridged) J Am Coll Health. 2009;57:477–88. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.477-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2006. Report. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schane RE, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Nondaily and social smoking: an increasingly prevalent pattern. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1742–4. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minnesota Department of Health. Tobacco Use in Minnesota, 1999 to 2007: The Minnesota Adult Tobacco Survey. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Health; Available at: http://www.mntobacco.nonprofitoffice.com/. Accessed: 10 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease, Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use Prevention Program of the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Adult Tobacco Survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2006. Available at http://tobaccofree.mt.gov/publications/surveillancereports/april2006.pdf. Accessed: 31 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minnesota Department of Health. 2006 Minnesota State University Moorhead Secondhand Smoke Study of Students and Faculty/Staff. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okah FA, Okuyemi KS, McCarter KS, et al. Predicting adoption of home smoking restriction by inner-city Black smokers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1202–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The Focus Group Kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lader D, Meltzer H. London, UK: Office of National Statistics; 2003. Smoking related attitudes and behaviour, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lader D, Goddard E. London, UK: Office of National Statistics; 2005. Smoking related attitudes and behaviour, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrie EM, et al. Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:591–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thrasher JF, Besley JC, Gonzalez W. Perceived justice and popular support for public health laws: a case study around comprehensive smoke-free legislation in Mexico City. Soc Sci Med. 2009;70:787–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loukas A, Garcia MR, Gottlieb NH. Texas college students' opinions of no-smoking policies, secondhand smoke, and smoking in public places. J Am Coll Health. 2006;55:27–32. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.1.27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magzamen S, Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Print media coverage of California's smokefree bar law. Tob Control. 2001;10:154–60. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Llaguno-Aguilar SE, del Carmen Dorantes-Alonso A, Thrasher JF, et al. Analysis of coverage of the tobacco issue in Mexican print media. Salud Publica Mex. 2008;50:S348–54. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baillie L, Callaghan D, Smith M, et al. A review of undergraduate university tobacco control policy process in Canada. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:922–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JG, Goldstein AO, Kramer KD. Statewide diffusion of 100% tobacco-free college and university policies. Tob Control. 2010;19:311–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris KJ, Stearns JN, Kovach RG, et al. Enforcing an outdoor smoking ban on a college campus: effects of a multicomponent approach. J Am Coll Health. 2009;58:121–6. doi: 10.1080/07448480903221285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berg CJ, Cox LS, Nazir N, et al. Correlates of home smoking restrictions among rural smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:353–60. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berg C, Choi WS, Kaur H, et al. The roles of parenting, church attendance, and depression in adolescent smoking. J Community Health. 2009;34:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Sciences, Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pizacani BA, Martin DP, Stark MJ, et al. Household smoking bans: which households have them and do they work? Prev Med. 2003;36:99–107. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kegler M, Malcoe L. Smoking restrictions in the home and car among rural Native American and white families with young children. Am J Prev Med. 2002;35:334–42. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]