Abstract

BACKGROUND: Diffuse low-grade gliomas (DLGGs) represent several pathological entities that infiltrate and invade cortical and subcortical structures in the brain.

OBJECTIVE: To describe methods for rapid prototyping of DLGGs and surgically relevant anatomy.

METHODS: Using high-definition imaging data and rapid prototyping technologies, we were able to generate 3 patient DLGGs to scale and represent the associated white matter tracts in 3 dimensions using advanced diffusion tensor imaging techniques.

RESULTS: This report represents a novel application of 3-dimensional (3-D) printing in neurosurgery and a means to model individualized tumors in 3-D space with respect to subcortical white matter tract anatomy. Faculty and resident evaluations of this technology were favorable at our institution.

CONCLUSION: Developing an understanding of the anatomic relationships existing within individuals is fundamental to successful neurosurgical therapy. Imaging-based rapid prototyping may improve on our ability to plan for and treat complex neuro-oncologic pathology.

Keywords: 3-D printing, Brain tumor modeling, Diffusion tensor imaging

ABBREVIATIONS

- 3-D

3-dimensional

- DLGG

diffuse low-grade glioma

- HGG

high-grade glioma

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- CST

corticospinal tract

- WHO

World Health Organization

- ROI

region of interest

- GLISTR

Glioma Image Segmentation and Registration

Although rapid prototyping (or 3-dimensional [3-D] printing) has had widespread use in manufacturing and modeling for over a decade, medical applications have been relatively recent. Three-dimensional printed models have been used for customized anatomic modeling and as implantable devices.1,2 Neurosurgeons treat pathology involving some of the most complex and intricately organized anatomic structures in the human body. Three-dimensional printing technologies can serve neurosurgeons in allowing for the creation of easily interpreted, individual models of patient anatomy.

The majority of studies dealing with rapid prototyping and neurosurgical pathology have focused on models of intracranial aneurysms and cranial prostheses.3-8 Brain tumors, however, have received less attention with respect to rapid prototyping. This may be due to the wide variation in terms of brain tumor pathologies and their intrinsic involvement of the brain parenchyma. The most common primary brain tumors diagnosed in adults are of the high-grade glioma (HGG) subtypes, which are known for their molecular and pathological heterogeneity. As such, the imaging qualities of HGGs are variable.9,10 Given the vasogenic edema often associated with these tumors, representations of white matter tracts based on conventional diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can be difficult to generate and may be erroneous.11 Necrosis, multiplicity, and variations in enhancement further make HGGs radiologically diverse entities.12 These represent some of the reasons that 3-D rapid prototyping of HGGs with respect to their subcortical white matter tracts remains a challenge.

Diffuse low-grade gliomas (DLGGs) on the other hand, are nonenhancing tumors that are best seen on T2- and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).13 These tumors tend to affect subcortical white matter tracts—spreading along, displacing, or disrupting them—without exerting significant mass effect.13,14 As compared to HGGs, DLGGs are less likely to infiltrate white matter and are not as often associated with edema;15 several studies have demonstrated that DLGGs affect fractional anisotropy (FA) values less significantly as compared to HGGs.16-18 Furthermore, FLAIR imaging techniques may approximate the boundary of DLGGs.13 As such, volumetric models representing the generally homogenous FLAIR signal can be created utilizing tumor segmentation based on registration of a probabilistic atlas to the MR images of the patient.19 Using this volumetric data and DTI techniques (utilizing FA values that are relatively preserved), we have created individualized, 3-D scale models of DLGGs and their adjacent subcortical white matter tracts. Two cases and models follow our illustrative case.

Illustrative Cases

Patient A

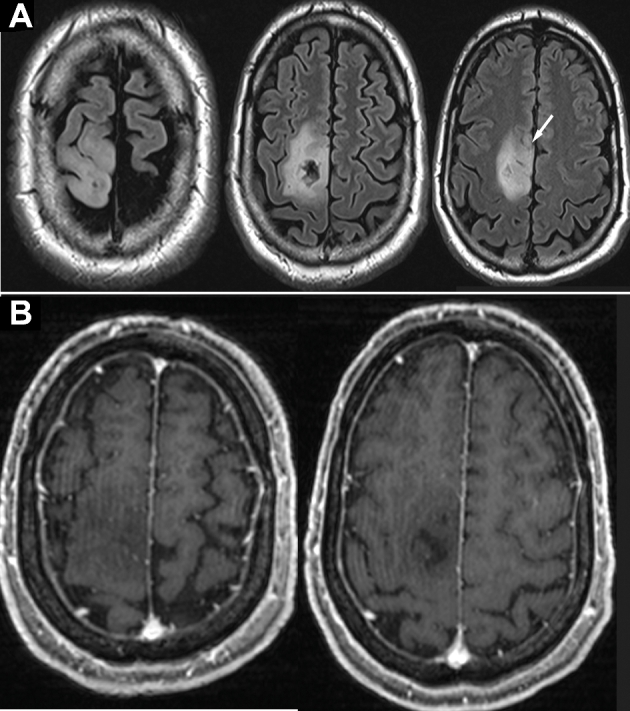

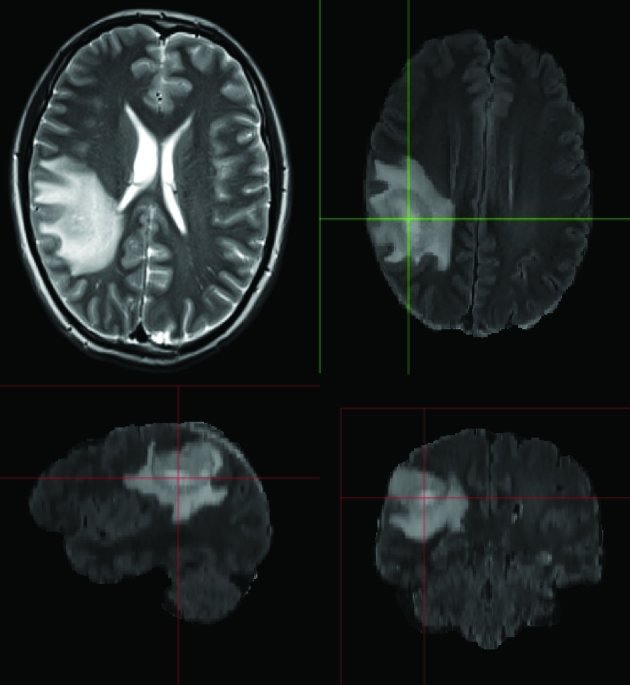

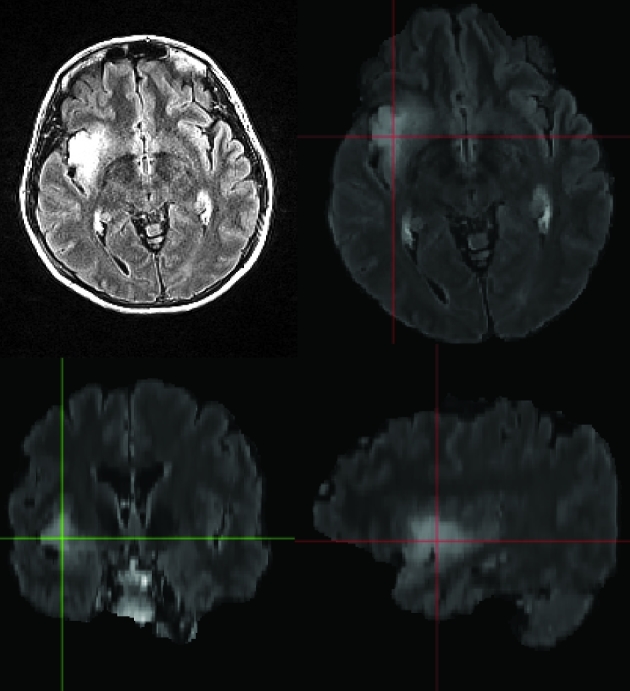

Patient A presented after a generalized tonic–clonic seizure while exercising and was found to have a nonenhancing lesion in the right posterior frontal region. DTI demonstrated close association of the posterior tumor border with the corticospinal tract (CST). Figure 1 depicts the patient's brain tumor on preoperative imaging.

FIGURE 1.

Patient A, preoperative MRI of right posterior frontal DLGG. A, T2-weighted imaging demonstrating tumor. The white arrow indicates anterior inferior extension (demonstrated further on 3-D model). B, T1-weighted imaging with gadolinium administration shows no enhancement.

The patient elected for an awake craniotomy with cortical and subcortical motor mapping. A current of 1 to 3 mA, pulse frequency of 60 Hz, single-pulse phase duration of 1 ms was applied for 2 to 4 s using a 5-mm spaced bipolar (Ojemann) stimulator. Motor function was identified at the cortical level under local anesthesia based on weakness in the left lower extremity during stimulation. Using subcortical stimulation during resection of the posterior aspect of the tumor, we identified tonic movements in the distal left lower extremity but no weakness. At this point, the surgical resection cavity was within 1 to 2 mm of the posterior aspect of the tumor based on neuronavigation. Intraoperatively, the CST fibers were not immediately visible. Resection proceeded. The patient recovered well from surgery with slight weakness in his distal left lower extremity (4+/5) discovered postoperatively. His strength recovered to full strength (5/5) after 2 months of intensive rehabilitation. Postoperative imaging demonstrated a subtotal resection. Pathology demonstrated a World Health Organization (WHO) grade II oligoastrocytoma.

Patient B

Patient B presented with intermittent left hand numbness and weakness preceding a generalized tonic–clonic seizure. The patient was found on imaging studies to have a 3.6-cm T2-hyperintense lesion based in the right parietal lobe with cortical and subcortical involvement extending into the atrial ependyma. The patient elected for surgery under general anesthesia. Somatosensory evoked potential phase reversal (using a 4-electrode subdural array) was utilized in order to localize the central sulcus following craniotomy. Electromyography and motor evoked potential monitoring were utilized upon making corticectomy and particularly in the subcortical region at the posteromedial aspect of the tumor resection. The white matter tract anatomy was not clearly visible in the operating room, even with microscope magnification. The patient experienced a 15% decrease in motor evoked potential signals relating to the left upper extremity. Strength was noted full postoperatively, although the patient noted subjective weakness which improved with rehabilitation. Postoperative imaging demonstrated a subtotal resection and the patient was found to have a WHO grade II diffuse (gemistocytic) astrocytoma.

Patient C

Patient C presented with olfactory auras and a generalized tonic–clonic seizure. The patient was found to have a 1.4-cm right temporal/insular nonenhancing mass. The patient underwent surgery under general anesthesia without motor mapping adjuncts. The tumor appeared to be visualized well, although white matter tracts were not specifically encountered during surgery. The patient awoke with a left hemiparesis that gradually improved. Pathology demonstrated a WHO grade II oligodendrogliomas with deletions of 1p and 19q.

METHODS

T1-, T2-, T2 FLAIR-, and diffusion-weighted images were acquired using a 3T MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Verio, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Parameters for diffusion imaging were as follows: repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 6300/90 ms, resolution = 1.7 × 1.7 × 3 mm, 30 diffusion directions with b = 1000 s/mm2. Diffusion tensors were fitted to the resultant DTI data and FA maps were computed. Deterministic tractography was performed, after which regions of interest (ROIs) were placed and tracts were extracted using TrackVis (www.Trackvis.org, Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts).20,21 ROIs were chosen through which FA values were calculated to generate DTI maps. Colorization of the white matter tracts as represented by DTI was performed according to our specifications.

Each ROI was more than 1 slice wide to ensure that all relevant fibers were included. In addition, a multiple-ROI approach was used for each track (except the corpus callosum) to ensure accuracy. For the CST, ROIs were in the cerebral peduncle and the internal capsule. ROIs for the arcuate fasciculus were chosen in the anterior and posterior segments and were identified as an intense green tract on coronal and axial slices. The corpus callosum ROI was placed midsagittally and included the genu, body, and splenium. Tumor segmentation was performed using Glioma Image Segmentation and Registration (GLISTR) software. We exported the tracts as well as the brain tumor as represented by FLAIR imaging in stereolithography (.STL) format. Using Solidworks (Dassault Systems SolidWorks Corporation, Waltham, Massachusetts), we generated solid objects from the DTI data and merged adjacent fibers to create resultant solids. The right CST, right arcuate fasciculus, and corpus callosum were chosen based on the tumor's location. The CST and corpus callosum were specifically identified as tracts impinged upon based on preoperative imaging studies.

We next used SolidWorks (Dassault Systems SolidWorks Corporation) to process the solid object files. In order to create an anatomically correct composite model, we used Meshmixer 10.9.297 (Autodesk, Berkeley, California) to generate small bridges or 3-D connections between the CST, the arcuate fasciculus, and the corpus callosum/tumor. We printed the tumor and tracts using the ProJet 6000 3-D Printer (3-D Systems Corporation, Rock Hill, South Carolina) at our institution's Mechanical Engineering prototyping lab. This device generates objects by using a polycarbonate-like photoreactive polymer. In order to generate complex models, a scaffold is automatically printed in order to support the structure as it is made. Models are then placed in a base bath at 60°C in order to dissolve the supporting scaffold.

Evaluation of Technique

To evaluate the utility of these models and this concept we used a brief survey that was administered to 4 faculty and 5 residents within our academic program. Each of these individuals was provided with the 3-D models, patient case histories, imaging studies for the group of patients, and a description of our methods. We used a survey utilizing a Likert scale (1 = definitely no, 2 = likely no, 3 = neutral, 4 = likely yes, 5 = definitely yes) to assess the utility of our technique (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

RESULTS

Patient A

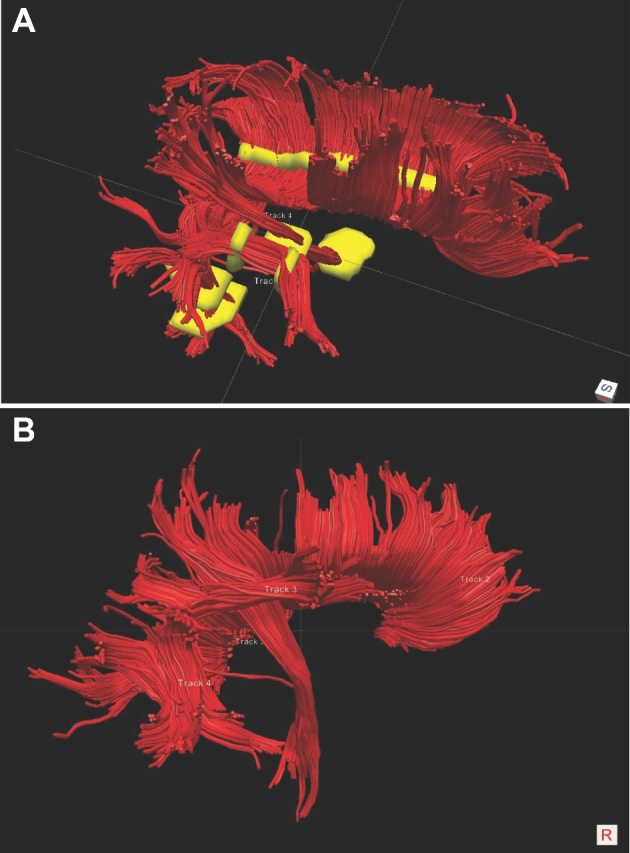

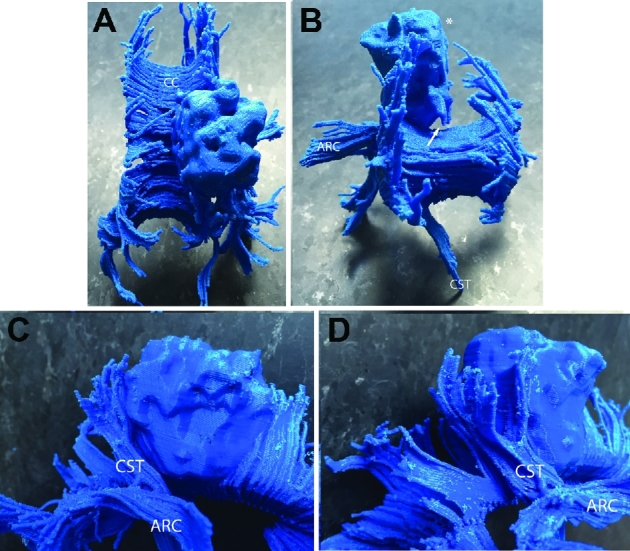

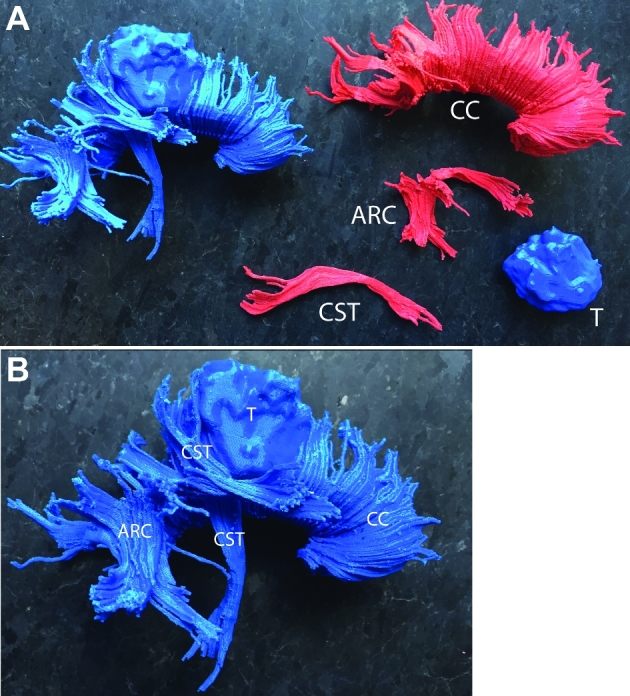

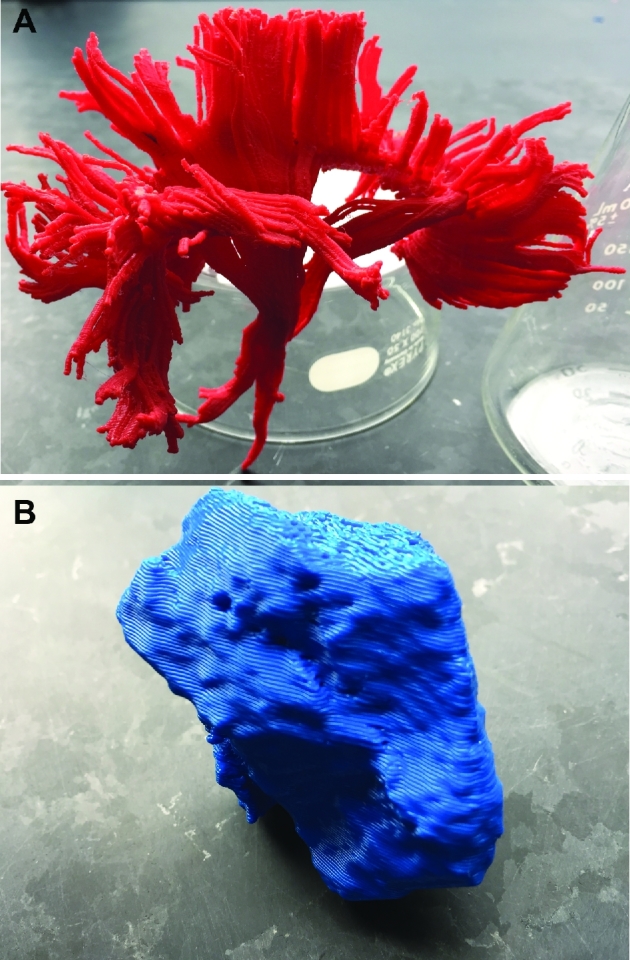

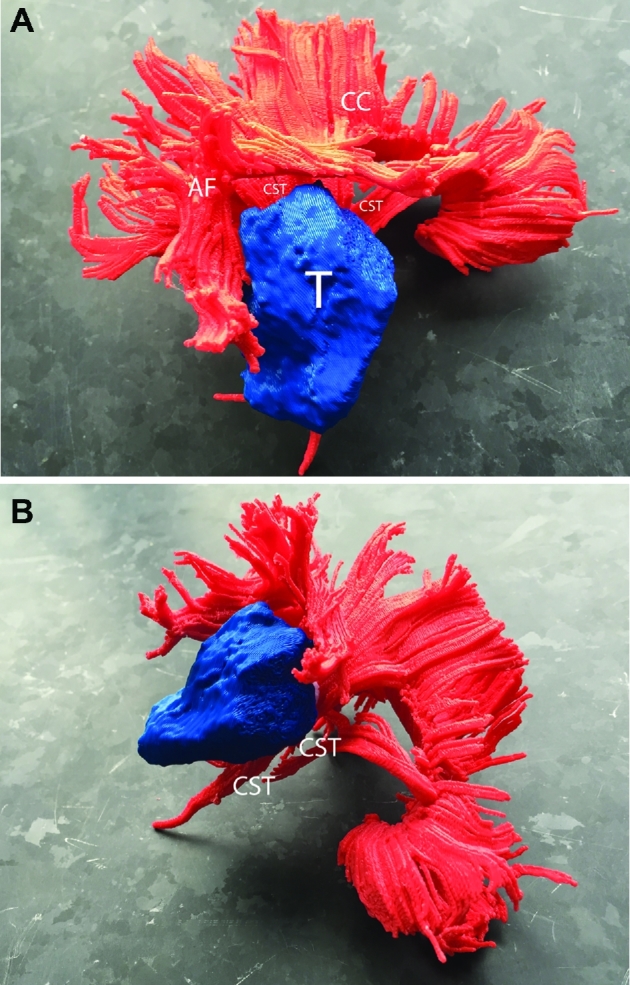

Patient A serves as our main illustrative case. Preoperative imaging studies are seen in Figure 1 (patient A). As seen in Figures 2 to 5, ROIs were chosen to generate DTI maps. Figures 3 to 8 show the individual and composite 3-D printed models that were generated. Patient A's tumor was printed in blue and took 3 h to generate. The right CST, arcuate fasciculus, and corpus callosum (printed in red) took 0.5, 1.5, and 6 h, respectively, to print. A composite model (10 h) was then printed with solids made to bridge the tumor and tracts (Figure 7). In this manner, we were able to preserve the spatial orientation of the tumor and white matter tracts according to our patient's individual anatomy. Based on correlative anteroposterior, transverse, and cross-section measurements of the tumor using digital caliper measurements, we determined that the model was also within <0.1 mm in terms of accuracy relative to imaging. Small extensions of the tumor were apparent in the model (white arrows in Figures 1, 6, and 8). The pial boundaries of the tumor (Figure 1A) were visible in the 3-D printed model at the interhemispheric fissure (asterisk, Figure 8) and at the posterior frontal cortex (gyral pattern, Figure 6).

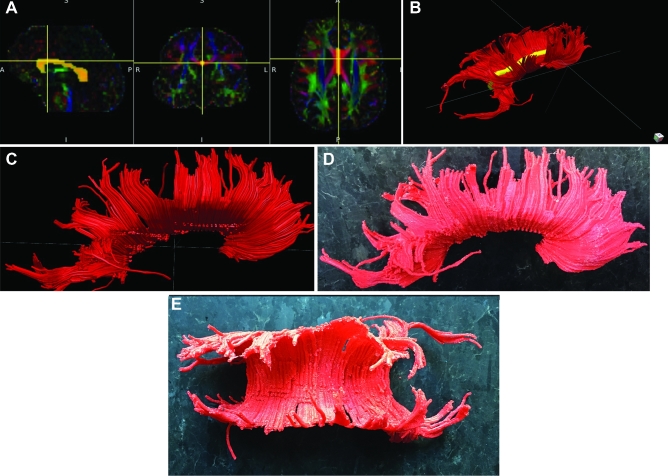

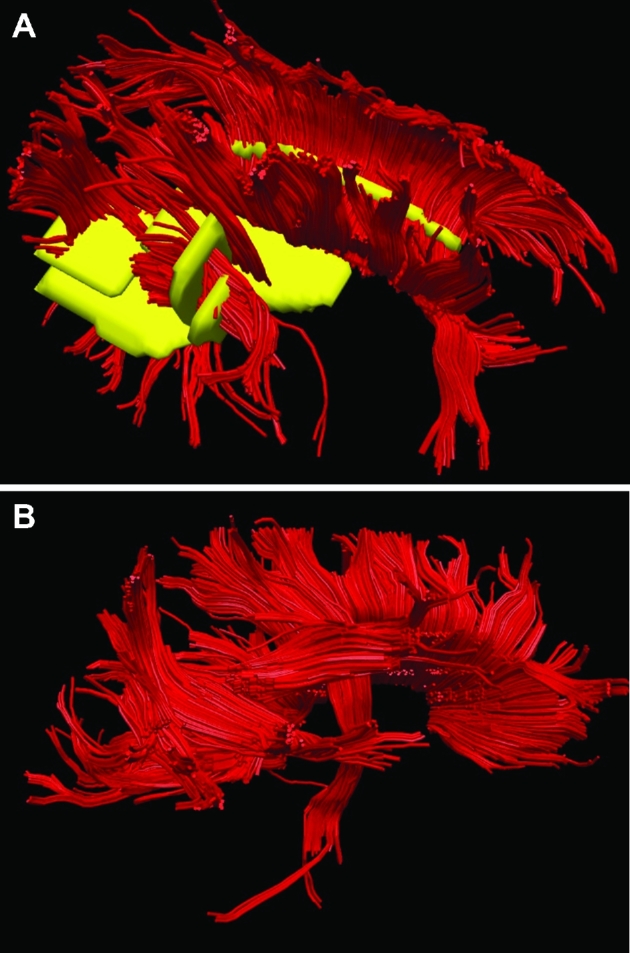

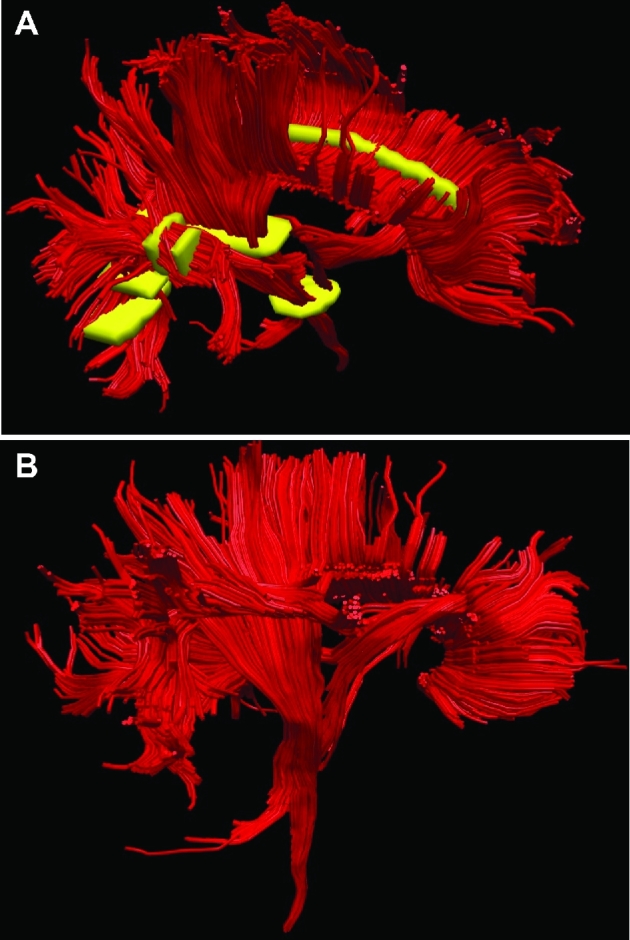

FIGURE 2.

Patient A, ROIs to generate DTI maps. A, ROIs (yellow) were chosen for the corpus callosum, arcuate fasciculus anterior and posterior, and CST. B, Right lateral view of corpus callosum, arcuate fasciculus (composite), and CST based on ROIs as chosen.

FIGURE 5.

Patient A, corpus callosum. A-C. ROIs chosen to delineate the corpus callosum based on DTI. D, Lateral view of 3-D printed corpus callosum. E, Superior view of 3-D printed corpus callosum.

FIGURE 3.

Patient A, CST. A-C, ROIs chosen to delineate CST based on DTI. D, Lateral view of 3-D printed CST. E, Anterior view of 3-D printed CST.

FIGURE 8.

Patient A, 3-D printed composite model, various views. A, Superior view. The cortical boundary of the brain tumor (refer to Figure 1A) is seen. The right posterior corpus callosum is invaded by the tumor. B, Anterior view. The flat medial cortical boundary adjacent to the interhemispheric fissure/falx is indicated by asterisk. The anterior–inferior extension (seen in Figure 1A, white arrow) is seen and indicated by a white arrow. The arcuate fasciculus projects away from the lateral surface of the tumor and CST projects through the peduncle of the midbrain toward the medulla. C and D, Lateral/anterior view C and lateral/posterior D views: rostral fibers of the CST abut the tumor at its posterior margin. Abbreviations: CC = corpus callosum, ARC = arcuate fasciculus, CST = corticospinal tract, T = tumor.

FIGURE 7.

Patient A, 3-D printed models. A, Composite model incorporating the right posterior frontal tumor, CST, arcuate fasciculus, and corpus callosum. Each component in the composite model is bridged by a small 3-D solid to preserve anatomic relationships and connect the features in space as in the patient. B, The CST is closely associated with the posterior aspect of the brain tumor. The tumor invades into the right posterior fibers of the corpus callosum. Abbreviations: CC = corpus callosum, ARC = arcuate fasciculus, CST = corticospinal tract, T = tumor.

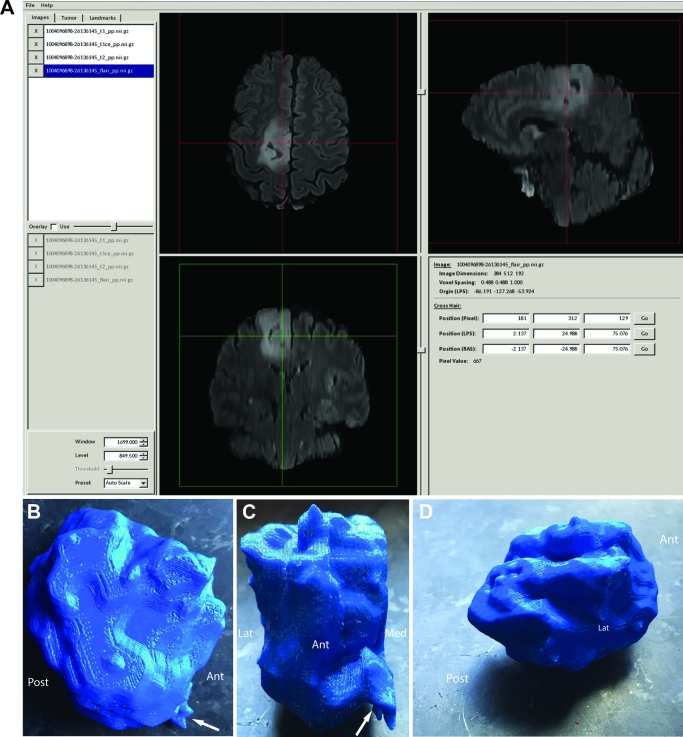

FIGURE 6.

Patient A, right posterior frontal tumor segmentation and model. A, GLISTR software screenshot depicting segmentation using the FLAIR imaging sequence images. B, Lateral view of tumor. White arrow indicates anteroinferior feature best seen in Figure 1A (white arrow). C, Anterior view of tumor. White arrow indicates anteroinferior feature best seen in Figure 1A (white arrow). The medial cortical boundary of the tumor is flat relating to the medial aspect of the hemisphere abutting the falx and interhemispheric fissure. D, Cortical pial boundary of tumor en face. Gyral features of the tumor are demonstrated in the model (refer to Figure 1A for comparison). Abbreviations: Ant = anterior, Post = posterior, Lat = lateral, Med = medial.

FIGURE 4.

Patient A, arcuate fasciculus. A and B, ROIs chosen to delineate arcuate fasciculus anterior and posterior based on DTI. C, Lateral view of 3-D printed arcuate fasciculus (composite). D, Lateral view of 3-D printed arcuate fasciculus.

Patient B

Preoperative imaging studies for this patient are detailed in Figure 9. Figure 10 shows the ROIs utilized in DTI maps and generating fiber tracts. As seen in Figure 11, the corpus callosum, arcuate fasciculus, and CST fibers are represented in blue and were generated in 7 h. Viewed from the lateral aspect, the gyral characteristics of the tumor's area of involvement are appreciated (Figure 11). The tumor was printed in off-white and took 2 h to generate. The tumor's juxtaposition with the CST is apparent and seen in Figure 12.

FIGURE 9.

Patient B, preoperative MRI of a right parietal gemistocytic astrocytoma. T2-weighted imaging demonstrating the tumor. GLISTR software screenshot depicting segmentation using the FLAIR imaging sequence images.

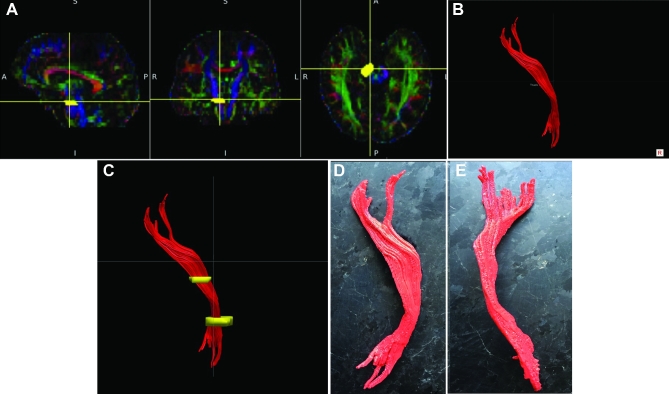

FIGURE 10.

Patient B, ROIs to generate DTI maps. A, ROIs (yellow) were chosen for the corpus callosum, arcuate fasciculus anterior and posterior, and CST. B, A lateral representation of the DTI model is shown.

FIGURE 11.

Patient B, 3-D printed models, various views. A, Lateral view of white matter tract anatomy. B, Rostral-caudal view of white matter tract anatomy. C, Lateral view of tumor.

FIGURE 12.

Patient B, 3-D printed composite model, various views. A, Lateral view. The infiltrating tumor lies adjacent to the CST and corpus callosum medially and the arcuate fasciculus both medially and anteriorly. B, Rostral-caudal view. C, Oblique rostral-caudal view. Abbreviations: CC = corpus callosum, ARC = arcuate fasciculus, CST = corticospinal tract, T = tumor.

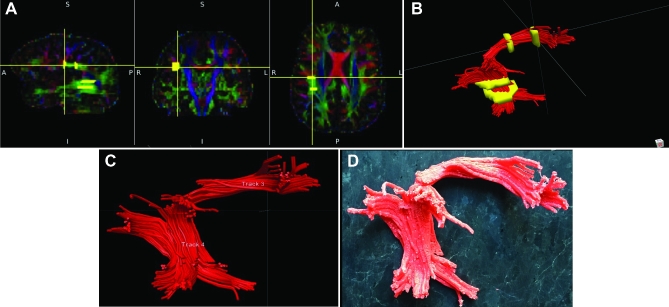

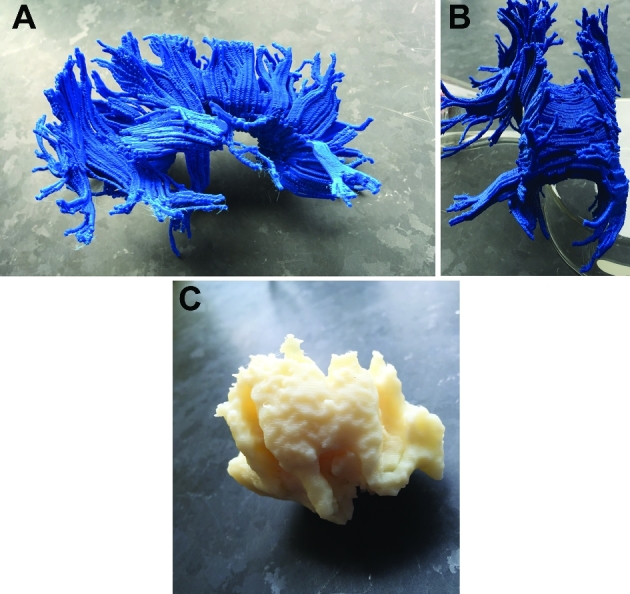

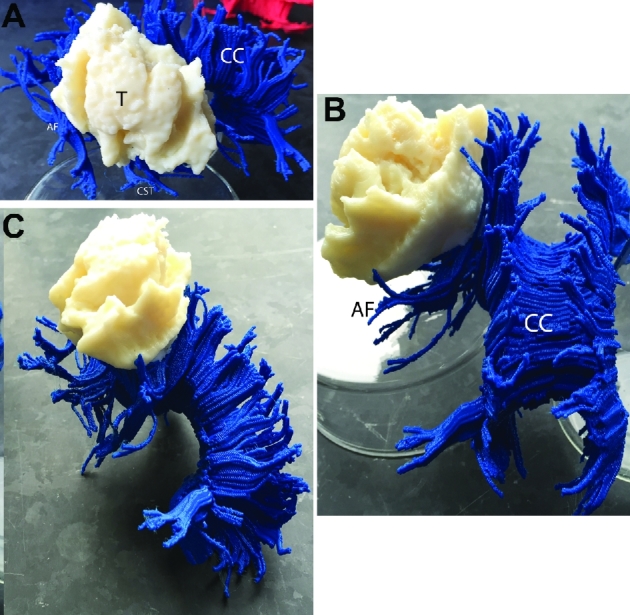

Patient C

Preoperative imaging studies for this patient are detailed in Figure 13. Figure 14 shows ROIs used in generating fiber tracts. Figure 15 shows the lateral aspect of the composite model with the corpus callosum, CST, and arcuate fasciculus represented in red. The model took 6.5 h to generate. The tumor shown in blue was generated in 45 min (Figure 15). The 3-D model views merging the tumor and white matter tract anatomy demonstrate the CST's location just medial to the tumor (Figure 16).

FIGURE 13.

Patient C, preoperative MRI of a right temporal/insular oligodendroglioma. GLISTR software screenshot depicting segmentation using the FLAIR imaging sequence images.

FIGURE 14.

Patient C, ROIs to generate DTI maps. A, ROIs (yellow) were chosen for the corpus callosum, arcuate fasciculus anterior and posterior, and CST. B, A lateral representation of the DTI model is shown.

FIGURE 15.

Patient C, 3-D printed models, various views. A, Lateral view of white matter tract anatomy. B, Lateral view of the prototyped tumor.

FIGURE 16.

Patient C, 3-D printed composite model, various views. A, Lateral view. The tumor lies adjacent to the CST and corpus callosum medially. B, Oblique rostral-caudal view. Abbreviations: CC = corpus callosum, ARC = arcuate fasciculus, CST = corticospinal tract, T = tumor.

Evaluation of technique

We found that faculty scores ranged from 4.25 to 5.0 (mean 4.75) and resident (postgraduate years 3-6) scores ranged from 4.6 to 5.0 (mean 4.77). These data and our survey have been included as supplementary data (Tables, Supplemental Digital Content 1 and 2). The individuals surveyed were not authors of the study. The response to this study was positive from both groups. Faculty comments highlighted the utility of this technology in presurgical planning, as patients may have difficulty understanding the context of their pathology or why certain procedures (such as awake craniotomies) are recommended based on the anatomic traits of their pathology. Faculty and resident comments supported the use of this technology in education and in facilitating operative teamwork when patients undergo awake craniotomies. If the model were readily available in the operating room (survey item 2), faculty (mean 4.75) and residents (mean 5.0) would favor use.

DISCUSSION

DLGGs are infiltrative lesions that often cause symptoms through interference and deafferentation of subcortical white matter tracts.13 An intimate knowledge of the orientation of the white matter tracts around the tumor border is necessary in order to preserve optimal function during tumor resection.13,14,22,23 As lesions that are not commonly associated with edema, FA data associated with DLGGs can be used to provide for more accurate 3-D representations of the tumor–white matter tract interface.

Using methods we have described, 3-D printed tumors and white matter tracts based on DTI can be used to generate individualized models. Although FA is less affected in DLGGs as compared to HGGs, the resulting tracts as approximated by DTI may be less accurate compared to true anatomic white matter tracts. Furthermore, the volumetric FLAIR imaging techniques that we utilized may be limited in that possible areas of anaplastic transformation, or variability within the tumor, are not represented in the model. T2 or FLAIR signal remains our best but imperfect imaging approximation for the pathological boundary of DLGGs.13 Still, these techniques can be used to make clearer the spatial relationship between the tumor to be resected and adjacent white matter tracts. Ultimately, cortical and subcortical stimulation as observed in the operating room with the interactive patient should be used to ascertain function and make surgical judgments during resection.

To date, there are only 2 scientific papers that describe rapid prototyping or 3-D printing techniques applied to brain tumors. Waran and Aziz et al24 demonstrated a tumor resection using multimaterial 3-D printed models. This impressive model allows for the user to go through the basic steps of a craniotomy while using intraoperative navigational techniques. Although it provides for training in the systematic planning to resect a brain tumor, it does not incorporate white matter tract elements and provide for a 3-D sense of the tumor in relation to the white matter tracts.24 Another study published by Waran and Kirollos et al25 used 3-D printing technology to create a model of obstructive hydrocephalus incorporating a pineal region tumor. These models were used for training in intraventricular surgery, and surveys demonstrated an educational benefit.25 The existing literature does not provide for 3-D representations of neuro-oncologic pathology in relation to the surrounding cerebral anatomy.

The main purpose of this technology is to provide the neurosurgeon and/or trainee with a better idea of the spatial anatomy of a patient's tumor with respect to the adjacent and at-risk subcortical white matter tracts during surgery. Although patient A had a favorable outcome following surgery, his operative course invoked in us a need for a better understanding of or representation of the anatomy associated with his tumor. Patients B and C similarly experienced deficits postoperatively. In the future, tumor and white matter tract models could be used in planning for craniotomies to augment awake surgeries and/or those incorporating brain-mapping techniques. These techniques in particular require a fundamental understanding of the subcortical white matter tract anatomy.13

Neurosurgeons and trainees may derive educational benefits from rapid prototyping of subcortical white matter tracts on a case-by-case manner given their involvement in preparing for and carrying out surgery relating to these relevant structures. White matter tract atlases based on DTI have been described previously and can be used effectively in teaching outside of the context of patient care.11,26,27 Although the accuracy of DTI in terms of delineating tracts has been questioned particularly in cases involving large tumors associated with edema (such as HGGs), specialized computational techniques can be utilized to better approximate white matter tracts.11 In this manner, rapid prototyping could have further applications beyond those reported here. With increasing access to 3-D printing technology, personalized anatomic models may enhance our ability to safely resect brain tumors.

CONCLUSION

We report the first 3-D printed models of patient brain tumors (DLGGs) with respect to the subcortical white matter tract anatomy. Modeling of tumors and white matter tracts was achieved through FLAIR imaging data and DTI, respectively. Three-dimensional printing technologies may benefit patients and practitioners by providing high-resolution, personalized, 3-D models at a low cost. Future work may demonstrate educational and practical benefits.

Disclosures

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 NS096606; principal investigators Drs Verma and Brem), and the Chera Family Foundation (Brain Mapping Grant, principal investigator Dr Brem). The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content is available for this article at www.neurosurgery-online.com.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article at www.neurosurgery-online.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. McGurk M, Amis AA, Potamianos P, Goodger NM. Rapid prototyping techniques for anatomical modelling in medicine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79(3):169-174. Available at: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2502901&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed July 28, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schubert C, van Langeveld MC, Donoso LA. Innovations in 3-D printing: a 3-D overview from optics to organs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(2):159-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abla AA, Lawton MT. Three-dimensional hollow intracranial aneurysm models and their potential role for teaching, simulation, and training. World Neurosurg. 2015;83(1):35-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson JR, Thompson WL, Alkattan AK et al. Three-dimensional printing of anatomically accurate, patient specific intracranial aneurysm models. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015. doi:10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mashiko T, Otani K, Kawano R et al. Development of three-dimensional hollow elastic model for cerebral aneurysm clipping simulation enabling rapid and low cost prototyping. World Neurosurg. 2015;83(3):351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Esses SJ, Berman P, Bloom AI, Sosna J. Clinical applications of physical 3-D models derived from MDCT data and created by rapid prototyping. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(6). doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rubino PA, Bottan JS, Houssay A et al. Three-dimensional imaging as a teaching method in anterior circulation aneurysm surgery. World Neurosurg. 82(3-4):e467-e474. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liew Y, Beveridge E, Demetriades AK, Hughes MA. 3-D printing of patient-specific anatomy: a tool to improve patient consent and enhance imaging interpretation by trainees. Br J Neurosurg. 2015:1-3. doi:10.3109/02688697.2015.1026799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kao HW, Chiang SW, Chung HW, Tsai FY, Chen CY. Advanced MR imaging of gliomas: an update. Biomed Res Int. 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/970586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mabray MC, Barajas RF, Cha S. Modern brain tumor imaging. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2015;3(1):8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akbari H, Macyszyn L, Da X et al. Pattern analysis of dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging demonstrates peritumoral tissue heterogeneity. Radiology. 2014;273(2):502-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim HS, Goh MJ, Kim N, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Kim JH. Which combination of MR imaging modalities is best for predicting recurrent glioblastoma? Study of diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility. Radiology. 2014;273(3):831-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duffau H, ed. Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults. London: Springer; 2013. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2213-5. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duffau H. Surgery of low-grade gliomas: towards a “functional neurooncology”. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21(6):543-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goebell E, Paustenbach S, Vaeterlein O et al. Low-grade and anaplastic gliomas: differences in architecture evaluated with diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 2006;239(1):217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tropine A, Vucurevic G, Delani P et al. Contribution of diffusion tensor imaging to delineation of gliomas and glioblastomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(6):905-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inoue T, Ogasawara K, Beppu T, Ogawa A, Kabasawa H. Diffusion tensor imaging for preoperative evaluation of tumor grade in gliomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107(3):174-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Price SJ, Burnet NG, Donovan T et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of brain tumours at 3T: a potential tool for assessing white matter tract invasion? Clin Radiol. 2003;58(6):455-462. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12788314. Accessed August 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gooya A, Pohl KM, Bilello M et al. GLISTR: glioma image segmentation and registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31(10):1941-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN, Wang R et al. Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography. Brain. 2007;130(pt 3):630-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wedeen VJ, Wang RP, Schmahmann JD et al. Diffusion spectrum magnetic resonance imaging (DSI) tractography of crossing fibers. Neuroimage. 2008;41(4):1267-1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duffau H. New concepts in surgery of WHO grade II gliomas: functional brain mapping, connectionism and plasticity–a review. J Neurooncol. 2006;79(1):77-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mert A, Kiesel B, Wöhrer A et al. Introduction of a standardized multimodality image protocol for navigation-guided surgery of suspected low-grade gliomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38(1):E4 doi:10.3171/2014.10.FOCUS14597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waran V, Narayanan V, Karuppiah R, Owen SLF, Aziz T. Utility of multimaterial 3-D printers in creating models with pathological entities to enhance the training experience of neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(2):489-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waran V, Narayanan V, Karuppiah R et al. Neurosurgical endoscopic training via a realistic 3-dimensional model with pathology. Simul Healthc. 2015;10(1):43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dini LI, Vedolin LM, Bertholdo D et al. Reproducibility of quantitative fiber tracking measurements in diffusion tensor imaging of frontal lobe tracts: a protocol based on the fiber dissection technique. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:51 doi:10.4103/2152-7806.110508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arnts H, Kleinnijenhuis M, Kooloos JGM, Schepens-Franke AN, van Cappellen van Walsum, AM. Combining fiber dissection, plastination, and tractography for neuroanatomical education: Revealing the cerebellar nuclei and their white matter connections. Anat Sci Educ. 7(1):47-55. doi:10.1002/ase.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental digital content is available for this article at www.neurosurgery-online.com.