SUMMARY

Genetic drivers of cancer can be dysregulated through epigenetic modifications of DNA. While the critical role of DNA 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in the regulation of transcription is recognized, the functions of other non-canonical DNA modifications remain obsure. Here, we report the identification of novel N(6)-methyladenine (N6-mA) DNA modifications in human tissues and implicate this epigenetic mark in human disease, specifically the highly malignant brain cancer, glioblastoma. Glioblastoma markedly upregulated N6-mA levels, which co-localized with heterochromatic histone modifications, predominantly H3K9me3. N6-mA levels were dynamically regulated by the DNA demethylase, ALKBH1, depletion of which led to transcriptional silencing of oncogenic pathways through decreasing chromatin accessibility. Targeting the N6-mA regulator, ALKBH1, in patient-derived human glioblastoma models inhibited tumor cell proliferation and extended survival of tumor-bearing mice, supporting this novel DNA modification as a potential therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Collectively, our results uncover a novel epigenetic node in cancer through the DNA modification, N6-mA.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

N6-methyladenine DNA modifications are enriched in human glioblastoma and decreasing this modification can inhibit cancer growth by limiting chromatin accessibility at oncogenic loci

INTRODUCTION

Aberrant epigenetic landscapes promote tumor initiation and progression (Elsasser et al., 2011; Loven et al., 2013; Northcott et al., 2014). To date, the focus of cancer research has been on the global and local aberrations of 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Genome-wide 5mC hypomethylation frequently occurs in cancer genomes, leading to widespread genomic instability and de-repression of repetitive elements (Cadieux et al., 2006; Feinberg and Vogelstein, 1983; Widschwendter et al., 2004). However, local hypermethylation of 5mC events are often found in close proximity to important tumor suppressor genes in a number of cancers (Esteller, 2002). Low grade gliomas and secondary glioblastomas commonly harbor mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 (IDH1/2), leading to DNA hypermethylation and manifesting as the glioma-CpG island methylator phenotype (G-CIMP) (Noushmehr et al., 2010; Turcan et al., 2012). Thus, DNA methylation is a critical epigenetic mark that regulates many important developmental processes and plays a fundamental role in cancer.

While numerous epigenetic modifications have been described in addition to DNA methylation, it is still unknown whether tumor cells can adopt novel epigenetic mechanisms that are rarely utilized in normal adult tissues. In addition to the canonical 5mC, other DNA methylation events, including N(6)-methyladenine (N6-mA), have been identified in bacteria (Vanyushin et al., 1968) and a limited number of eukaryotes, such as mosquitoes, plants, C. elegans and Drosophila (Fu et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2015; Rogers and Rogers, 1995; Yao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). We recently demonstrated that N6-mA DNA methylation occurs in mammals, where it acts mainly as a repressive mark to silence transcription of LINE transposons in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (Wu et al., 2016) and this modification has also been reported in human tissue (Xiao et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018). However, the roles of N6-mA in human cancer and in genome biology are largely unknown.

To interrogate N6-mA function, we utilized glioblastoma as a model human cancer. Glioblastoma is the most prevalent and aggressive primary intrinsic brain tumor and is characterized by widespread epigenetic dysregulation, including DNA hypermethylation of 5mC and alterations in chromatin remodelling enzymes, such as the polycomb complex proteins, EZH2 and BMI1 (Abdouh et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2017; Suva et al., 2009). Thus, we studied the N6-mA DNA modification in human patient-derived glioblastoma tumor models and functionally characterized its genomic localization and role in the regulation of glioblastoma.

RESULTS

Identification of N6-mA DNA modifications in human glioblastoma

To investigate the roles of the N6-mA DNA modification in human glioblastoma, we extracted genomic DNA from functionally validated human patient-derived glioblastoma stem cell (GSC) models (387, D456, GSC23, and 1919) and primary human tumor specimens (3028 and CW2386), then performed dot blot analysis using an N6-mA specific antibody that has been previously validated (Greer et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015). GSCs and primary human tumor specimens displayed strikingly elevated N6-mA levels relative to normal human astrocytes (Figure 1A). N6-mA levels were independently quantified by mass spectrometry (MS) using an established and highly sensitive (LOQ: 1.6 fmol) mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) approach with stable isotope-labeled [15N5] N6-mA as an internal standard for sample enrichment and quantification (Figures S1A and S1B), which demonstrated that N6-mA levels in GSCs were elevated more than hundredfold compared to normal human astrocytes (Figure 1B). N6-mA DNA levels were also measured by immunofluorescence staining. To eliminate signal from RNA, samples were treated with RNaseA prior to incubation with primary antibodies. N6-mA DNA levels detected by immunofluorescence validated dot blot and mass spectrometry results, with much higher N6-mA levels in the patient-derived GSCs than in normal human astrocytes (Figures 1C and 1D). Effects of cell culture conditions were ruled out using DNA N6-mA immunohistochemistry on a tissue microarray (TMA) with normal brain and glioblastoma tissues, confirming increased DNA N6-mA levels in glioblastoma (Figures 1E and 1F). Potential inter-individual heterogeneity in N6-mA levels was addressed using immunofluorescence staining of matched glioblastoma and surrounding normal brain tissue from the same patient following surgical resection. Consistently, glioblastoma tumor tissue contained increased levels of N6-mA (Figure S1C). N6-mA levels were elevated in other central nervous system cancers, including diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), meningioma, and medulloblastoma, compared to normal human astrocytes (Figure S1D). Of note, a recent study reported high levels of N6-mA in normal human adult tissues (at several hundred PPM), with downregulation in gastric and stomach cancers (Xiao et al., 2018). However, our current study, together with other previous studies (Zhu et al., 2018) did not find high levels of N6-mA in normal adult tissues or mammalian cells. Collectively, our results support elevation of a novel DNA modification, N6-mA, in glioblastoma, with likely involvement in other cancers.

Figure 1. Identification of N(6)-methyladenine (N6-mA) DNA modification in human glioblastoma. See also Figure S1.

(A) Levels of the N6-mA DNA modification were assessed via DNA dot blot in (1) normal human astrocytes, (2) patient-derived GSC models (387, D456, GSC23, and 1919) and (3) primary human glioblastoma specimens (3028, CW2386) using an N6-mA-specific antibody. Methylene blue detected DNA loading.

(B) Mass spectrometry analysis of N6-mA in two normal human astrocyte cell lines and two patient-derived GSC models (387 and D456). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two replicates were used for each sample. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test. P < 0.0001 for each human astrocyte vs. GSC comparison.

(C) N6-mA DNA immunofluorescence in normal human astrocytes and human patient-derived GSC models (387, D456, GSC23). DAPI indicates cell nuclei. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(D) Quantification of percentage of N6-mA positive cells by immunofluorescence staining in (C). N6-mA was quantified counting 100 cells from each sample. N = 3 slides/cell type. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Significance assessed by ANOVA. ***, P < 0.001.

(E) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of N6-mA in non-neoplastic brain tissues (6 total) and human primary glioblastoma specimens (67 total) from a tissue microarray. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(F) Quantification of N6-mA levels from immunohistochemistry staining in (E). N6-mA levels were scored from low levels (score = 0) to highest levels (score = 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test, P = 0.0006.

Genomic profiling and pattern of N6-mA in glioblastoma

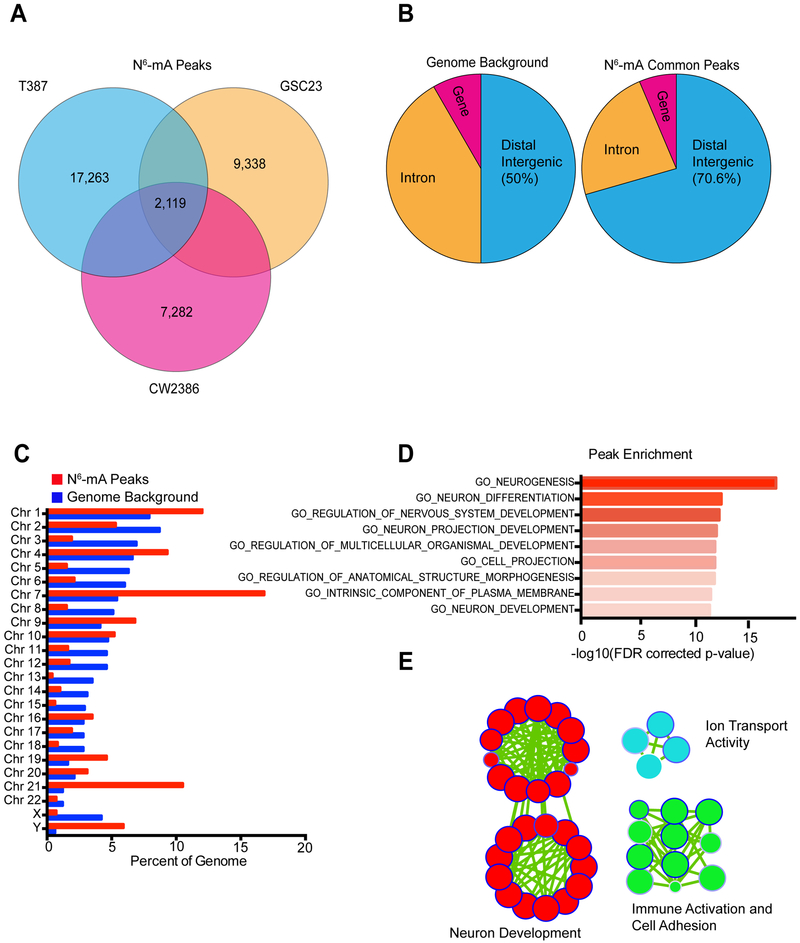

N6-mA genomic localization was analyzed using N6-mA DIP-seq (DNA immunoprecipitation with anti-N6-mA antibodies followed by next-generation sequencing) in two human patient-derived GSC models (387 and GSC23) and one primary human tumor specimen (CW2386) to identify N6-mA-enriched genomic regions. The number of N6-mA peaks measured by DIP-sequencing in glioblastoma ranged from 7,282 to 17,263 per model (Figure 2A). N6-mA peaks were most common in intergenic regions, consistent with our previous findings in murine ESCs (Wu et al., 2016) (Figure 2B). N6-mA peaks were present on each chromosome with mild enrichment on chromosomes 7, 19, and 21 (Figure 2C). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the closest gene to each of the shared N6-mA peaks revealed an enrichment in neurogenesis and neuronal development pathways (Figures 2D and 2E). GO analysis restricted to peaks within gene bodies revealed similar results (Figures S2A and S2B). Although adenine nucleotides are distributed throughout the genome, selective distribution of N6-mA could reflect sequence-specific recognition of molecular regulators. To investigate this, we identified DNA motifs enriched within N6-mA regions in the common shared peaks. One of the top ranking motifs (GGAAT) closely resembles human major satellite repeats that are enriched at constutitive heterochromatic regions (Figure S2C). Consistent with findings that DNA N6-mA functions as a repressive mark in murine ESCs and brains (Wu et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2017), these data suggest that N6-mA-mediated repression of neurodevelopmental pathways may serve a role in heterochromatin formation that contributes to glioblastoma tumorigenesis.

Figure 2. Genomic localization of N6-mA enrichment in glioma stem cells. See also Figure S2.

(A) N6-mA enrichment was identified using SICER for a human primary glioma sample (CW2386) and two in vitro human patient-derived glioma models (T387 and GSC23). The number of N6-mA peaks are shown with the number of shared peaks in the center.

(B) Genome Ontology analysis showing the fraction of common N6-mA peaks present in distal intergenic, intronic, or gene regions compared to genome background. (Chi-squared test, P < 0.0001)

(C) Genome Ontology analysis showing the fraction of common N6-mA peaks on each chromosome compared to genome background. Chromosome 7: p = 1.2 × 10−208; Chromosome 21: p = 2.2 × 10−322; Chromosome 3: p = 5.1 × 10−68; Chromosome 5: p = 1.2 × 10−69.

(D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the closest gene to each of the common N6-mA peaks. Values are expressed as −log10 (FDR corrected p-value).

(E) Enrichment map demonstrating key pathways identified in the GO enrichment analysis in panel (D). Circles represent individual gene sets. The size of the circle depicts the number of genes in the gene set and the edge color depicts the FDR-corrected p-value of the enrichment, with dark blue representing the most significant gene sets.

N6-mA is enriched in heterochromatin

To explore the molecular mechanism of N6-mA as a repressive epigenetic modification, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) for two heterochromatin marks [histone 3 lysine 9 trimethyl (H3K9me3) and histone 3 lysine 27 trimethyl (H3K27me3)] and a euchromatin mark [histone 3 lysine 4 trimethyl (H3K4me3)] in a patient-derived GSC model. Over 80% of N6-mA peaks intersected with regions bearing heterochromatic histone modifications (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3), while few peaks (3.5%) overlapped with euchromatic histone modifications (H3K4me3) (Figures 3A-C). Most commonly, N6-mA marks occurred in regions bound by both heterochromatin marks. N6-mA marks in regions bound by only a single heterochromatin mark were increased near peaks bound by H3K9me3 alone (26.4%), while peaks bound by H3K27me3 alone (16.2%) were less frequently enriched (Figures 3A and 3B). Aggregation analysis showed that N6-mA peaks common to all three glioma models (Figure 2A) were directly superimposed with those of the heterochromatic histone marks (Figure 3C). All N6-mA peaks in the 387 patient-derived GSC model, some of which were unique in this model, were strongly correlated with these heterochromatic marks (Figure 3D). Genomic overlap between the N6-mA DNA modification and the canonical 5mC DNA methylation mark was interrogated through whole genome bisulfite sequencing analysis of the 387 patient-derived GSCs and mapping of the intersection with N6-mA. As expected, 5mC marks were depleted in promoter regions, but slightly increased in N6-mA peaks compared to randomly selected genomic regions (Figures S2D-G). Thus, our data suggest that N6-mA strongly co-localizes with heterochromatic histone modifications and with the largely repressive canonical DNA methylation mark, 5mC.

Figure 3. Intersection of N6-ma peaks with heterochromatin-associated histone modification domains in glioma stem cells. See also Figure S3.

(A) The fraction of N6-mA peaks in a patient derived GSC model (387) that overlap with matched H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K4me3 histone modification domains in the same model.

(B) Number of overlaps between N6-mA peaks and histone modification domains in a patient derived GSC model (387) relative to genome background.

(C) Heatmap and Profile plot demonstrating the intersection of N6-mA common peaks with H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 signal over scaled window 5kb upstream and downstream of the common N6-mA peak.

(D) Heatmap of N6-mA peaks in a GSC model (387) divided into those that are cobound with H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, those bound by H3K9me3 or H3K27me3 alone, and those bound by H3K4me3 alone. Signal is shown over a scaled window 5kb upstream and downstream of the N6-mA peak and the height of the heatmap is directly proportional to the number of regions present in each segment.

As the N6-mA DNA modification acts as a repressive mark that is highly associated with the H3K9me3 heterochromatin histone modification, the high levels of N6-mA may function to support GSC survival by repressing key tumor suppressor genes. To investigate this possibility, the Tumor Suppressor Gene (TSG) Database (Zhao et al., 2016) was leveraged to identify potential tumor suppressor genes that contain both N6-mA and H3K9me3 enrichment. Several tumor suppressor genes, including CDKN3, RASSF2 and AKAP6, appear to be repressed by N6-mA and H3K9me3 (Figure S3).

ALKBH1 is a DNA N6-mA demethylase that actively modulates gene expression in human glioblastoma

DNA methylation is dynamically regulated by a number of enzymes. We next investigated the enzymes controlling DNA N6-mA modification in glioblastoma. Our previous study in murine ESCs identified Alkylated DNA Repair Protein AlkB Homolog (ALKBH1) as a demethylase for DNA N6-mA (Wu et al., 2016), so we focused on its human homolog as a potential regulatory node. In vitro DNA demethylation assays demonstrated strong N6-mA demethylase catalytic activity of the human ALKBH1 protein toward N6-mA in oligonucleotides using dot blotting (Figure 4A) or UHPLC-MS (Figure 4B). To investigate its functions in glioblastoma, ALKBH1 expression was targeted by two independent, non-overlapping small hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral constructs (designated shALKBH1.1008 and shALKBH1.1551) compared to a non-targeting control sequence shRNA insert (shCONT), which increased DNA N6-mA levels in two patient-derived GSCs (387 and D456; Figure 4C). As a recent study indicated that ALKBH1 might have activities against tRNA (Liu et al., 2016), we further investigated and found that ALKBH1 does not function as a tRNA-1mA demethylase in patient-derived GSCs (data not shown).

Figure 4. ALKBH1 is a N6-mA DNA demethylase in human glioblastoma and contributes to N6-mA co-localization with H3K9me3 genome wide. See also Figure S4.

(A) N6-mA labelled DNA oligonucleotides were treated in a cell-free in vitro demethylase reaction with recombinant human ALKBH1 proteins. Results are depicted by dot blot after treatment of two quantities of substrate DNA oligonucleotides.

(B) In vitro demethylation reaction was quantified by LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry following addition of ALKBH1 protein to N6-mA labelled DNA oligonucleotides. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. (Student’s t-test. ***, P < 0.001. N = 3)

(C) ALKBH1 expression was decreased using two independent shRNAs in human patient-derived GSC models and N6-mA levels were assessed using a DNA dot blot. Methylene blue detected DNA loading. ALKBH1 protein level was assessed using western blot.

(D) RNA-seq analysis in a human patient-derived GSC model following ALKBH1 knockdown. Blue dots indicate the most highly upregulated genes following ALKBH1 knockdown (37), while the red dots indicate the most highly downregulated genes following ALKBH1 knockdown (321).

(E) Venn Diagram indicates overlap between (1) genomic regions with gained N6-mA after ALKBH1 knockdown and (2) downregulated genes after ALKBH1 knockdown.

(F) Genome wide differentially accessible sites were identified by ATAC-seq. 1,632 sites of differential accessibility (FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05) were identified and are visualized in a MA-plot. 1,389 sites were identified with decreased accessibility after ALKBH1 knockdown while 243 sites displayed increased accessibility. Log2 fold change > 0.5; p < 0.05.

(G) Chromatin accessibility heatmap for the differentially accessible sites (absolute value of Log2 fold change > 1). Two replicates were performed for each treatment group. Signal is shown over a scaled window 5 kb upstream and downstream of the differentially accessible region.

(H) Supervised heatmap showing the correlation between the ATAC-seq counts in non-targeting and ALKBH1-knockdown samples. Two replicates were performed for each sample.

(I) Profile plot showing ATAC-seq signal over sites of decreased chromatin accessibility in ALKBH1-knockdown samples. Scaled signal is shown 5 kilobases upstream and downstream of each ATAC peak.

(J) Heatmap and profile plot showing the N6-mA DIP-seq and ATAC-seq signals over the top 10,000 ranked ATAC-seq peaks in the 387 GSC model.

(K) Graph showing the mRNA fold change following ALKBH1 knockdown for genes with sites of decreased accessibility. Among genes with decreased accessibility sites within 2KB of their transcriptional start site, 37 genes were downregulated while 19 genes were upregulated.

We next aimed to identify N6-mA methyltransferases in GSCs. N-6 adenine-specific DNA methyltransferase 1 (N6AMT1) was recently suggested as a DNA N6-mA methyltransferase in human cells (Xiao et al., 2018). In light of these findings, we interrogated the function of N6AMT1 in patient-derived GSCs. In contrast to this previous report, genomic knockout of N6AMT1 in GSCs did not alter the levels of DNA N6-mA, assessed by dot blot (Figures S4A and S4B). Further, purified N6AMT1 recombinant protein incubated with DNA oligonucleotides in vitro did not alter DNA N6-mA levels, suggesting that N6AMT1 does not serve as an N6-mA methyltransferase, at least in glioblastoma (Figures S4C and S4D). Our findings are consistent with a previous study that also did not support N6AMT1 as an N6-mA methyltransferase (Liu et al., 2010). Thus, we focused our attention on ALKBH1, the only definitive modulator of N6-mA in GSCs, to understand the role of N6-mA regulation in glioblastoma.

Our data suggest ALKBH1 may control specific genetic pathways in glioblastomas. To investigate this, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to interrogate the effects of ALKBH1-knockdown on the whole transcriptome. 321 genes were downregulated by twofold or greater, while only 37 genes were upregulated by more than twofold upon ALKBH1 depletion (Figure 4D), suggesting that an increase of N6-mA DNA levels primarily represses gene expression in human glioblastoma. To further elucidate the genomic sites of ALKBH1 demethylase activity, N6-mA DIP-seq was performed on a patient derived GSCs (387) after transduction with either one of two independent ALKBH1 shRNAs or shCONT. 68% of downregulated genes after ALKBH1 knockdown were associated with genomic regions with increased N6-mA levels (Figure 4E), strongly suggesting that the transcriptional downregulation is a direct consequence of elevated N6-mA levels due to ALKBH1 depletion. To understand the role of N6-mA in regulating chromatin accessibility, ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) was performed following knockdown of ALKBH1. Consistent with our finding of co-localization of N6-mA with heterochromatic regions, ALKBH1 knockdown led to a greater number of genomic loci with decreased chromatin accessibility (1,389 sites) than sites with increased accessibility (243 sites) (Figures 4F-I). ATAC-seq peaks, representing sites of open chromatin, negatively correlated with N6-mA peaks, indicating that N6-mA is depleted at sites of high chromatin accessibility (Figures 4J). Overlayed ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data showed that more genes bearing a significantly decreased accessibility site within 2 Kb of their transcriptional start sites tended to transcriptionally repressed (37 genes) rather than upregulated (19 genes) (Figure 4K). To further investigate the interaction between ALKBH1 and N6-mA modifications, biotin-labelled oligonucleotides with or without N6-mA modifications were used to perform ALKBH1 pulldowns using whole cell lysates from patient-derived GSCs. N6-mA modified oligonucleotides preferentially bound ALKBH1 relative to unlabelled oligonucleotides, suggesting that ALKBH1 binds regions bearing N6-mA modifications (Figure S5A). To assess the preference of ALKBH1 to bind N6-mA genome-wide, ALKBH1 ChIP-seq identified ALKBH1 binding sites were mapped to N6-mA peaks. ALKBH1 ChIP-seq peaks were preferentially enriched within N6-mA marked regions compared to the genome background (Figures S5B and S5C). Thus, ALKBH1 functions as a transcriptional activator by binding to regions of N6-mA enrichment and removing repressive N6-mA marks at selected genomic loci.

ALKBH1 depletion facilitates heterochromatin formation in human glioblastoma through N6-mA DNA modification

We next analyzed co-localization of N6-mA peaks and genomic sites directly regulated by ALKBH1 (i.e. N6-mA peaks gained after ALKBH1 knockdown). Consistent with the strong association of N6-mA and heterochromatin marks at a genome-wide level, N6-mA sites directly increased upon ALKBH1 knockdown were even more strongly correlated with heterochromatin histone modifications, particularly H3K9me3 (Figures 5A and 5B). Genes marked by N6-mA peaks overlapped with those marked by H3K9me3 (Figures 5C, 5D, and S5D). For example, two genes downregulated upon ALKBH1 depletion, RFTN2 and LOX, were marked by increased N6-mA levels that co-localized with H3K9me3 demarcated heterochromatin regions (Figures S5G and S5H).

Figure 5. ALKBH1 regulates downstream gene expression through N6-mA-dependent heterochromatin formation. See also Figures S5 and S6.

(A) Pie chart depicts the fraction of N6-mA peaks gained after ALKBH1 knockdown in a patient derived GSC model (387) that overlap with matched H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K4me3 histone modification domains in the same model.

(B) Overlaps between N6-mA peaks gained following ALKBH1 knockdown and histone modification domains in a patient derived GSC model (387) relative to genome background. **, p < 0.01.

(C) Pie chart shows the percentage of genes targeted by the N6-mA DNA modification that overlap with the H3K9me3 histone modification.

(D) Heatmap shows gained N6-mA peaks after ALKBH1 knockdown with shRNA (shALKBH1.1008) and co-localization with H3K9me3. Signal is shown over a scaled window 10kb upstream and downstream of the gained N6-mA peak.

(E) Volcano plot shows the number of H3K9me3 peaks gained (red: 9,999) and lost (blue: 2,995) following ALKBH1 knockdown in the 387 GSC model.

(F) Heatmap indicating sites of H3K9me3 enrichment following ALKBH1 knockdown with shALKBH1.1551. Signal is shown over a scaled window 5 kb upstream and downstream of the gained N6-mA peak.

(G) Examples of genes (SDK1 and BMT2) showing co-localization of gained N6-mA DNA modification peaks with gained H3K9me3 peaks following knockdown of ALKBH1 with shALKBH1.1551.

To assess the effects of ALKBH1-mediated alterations of N6-mA on the global H3K9me3-marked heterochromatin landscape, we performed H3K9me3 ChIP-seq following ALKBH1 knockdown in a patient derived GSCs, revealing an increased number of H3K9me3 peaks following ALKBH1 knockdown (9,999 peaks with increased H3K9me3 signal vs. 2,995 peaks with decreased H3K9me3 signal) (Figures 5E and 5F), which was confirmed in two additional patient-derived GSCs (Figures S5E and S5F). The genes SDK1 and BMT2 gained N6-mA peaks co-localizing with gained H3K9me3 signal following ALKBH1 knockdown (Figure 5G). Collectively, these results suggest that N6-mA plays an important role in facilitating heterochromatin formation in human glioblastoma, particularly acting through the H3K9me3 histone modification.

ALKBH1 regulates hypoxia-response genes

To interrogate the gene pathways regulated by ALKBH1-sensitive N6-mA sites, we performed GO analysis on genes downregulated upon ALKBH1 depletion, revealing enrichment of key oncogenic pathways previously implicated in glioblastoma pathogenesis, including hypoxia responses, nervous system development, cellular and tissue development, and plasma membrane structure pathways (Figures S6A and S6B). Of note, hypoxia response genes were modulated by ALKBH1, even when cells were grown under room air conditions. As hypoxia-related gene signatures were the top enrichment following ALKBH1 knockdown, the comparative transcriptional effects of ALKBH1 knockdown were assesseed under hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen) by RNA-seq. Similarly to the normoxic conditions, genes in the hypoxia pathway were downregulated following ALKBH1 knockdown when cells were grown in hypoxia (Figures S6C and S6D). Upregulated genes upon ALKBH1 knockdown in hypoxia included DNA damage and p53 pathway genes (Figures S6E and S6F). To support the clinical significance of these findings, an ALKBH1-regulated gene signature highly correlated with a hypoxia signature in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) glioblastoma dataset (Figure S6G). To explore the correlation between hypoxia and ALKBH1-dependent N6-mA demethylation sites, RNA-seq of GSCs under hypoxia identified over 50% of genes upregulated in hypoxia were suppressed by ALKBH1 knockdown (Figure S6H). N6-mA peaks that decreased following hypoxia tended to be located closer to upregulated genes in hypoxia (e.g. MIAT) than randomly selected peaks (genome background) (Figures S6I-K). Thus, ALKBH1 regulates key processes previously implicated in GSC biology through alterations in the N6-mA landscape. H3K9me3 has been previously linked to repression of hypoxia-induced genes during development and tumorigenesis (Luo et al., 2012), including in glioblastoma (Intlekofer et al., 2015). Collectively, our results demonstrate an unexpected role of N6-mA and ALKBH1 in modulating hypoxia-induced genes in human glioblastoma.

N6-mA is a potential therapeutic target in glioblastoma

To address the functional significance of N6-mA in tumor biology, we investigated ALKBH1 as a potential therapeutic target. ALKBH1 protein levels were modestly, but consistently, elevated in GSCs compared to their matched differentiated non-stem tumor cells by immunoblotting (Figure S7A). Silencing ALKBH1 decreased GSC proliferation (Figure 6A). To control for the potential off-target effects of shRNAs in additional experiments, we depleted ALKBH1 using sgRNAs by CRISPR-Cas9 technology with two independent non-overlapping single-guide RNAs (sgALKBH1#4 and sgALKBH1#5). Following ALKBH1 depletion with sgRNAs, glioma cells displayed reduced cell growth, consistent with the shRNA results (Figure 6B). Sphere formation is surrogate marker of self-renewal, albeit with caveats. In vitro limiting dilution sphere formation assays revealed that ALKBH1 knockdown resulted in a more than tenfold decrease in the frequency of sphere formation (Figure 6C). GSCs are functionally defined by their ability to initiate tumors in vivo, prompting us to evaluate the potential anti-tumor effects of ALKBH1 targeting in vivo. Two different patient-derived GSCs (387 and D456) transduced with either one of two non-overlapping ALKBH1-targeting shRNAs (shALKBH1) or control non-targeting shRNA (shCONT) were implanted into the brains of immunocompromised mice. Consistent with our in vitro results, animals bearing tumors derived from GSCs expressing shRNAs or sgRNAs targeting ALKBH1 displayed increased survival relative to those bearing GSCs expressing shCONT or sgCONT, respectively (Figures 6D and 6E). In light of the role of ALKBH1 in the regulation of hypoxia pathways, we determined the effects of ALKBH1 knockdown in hypoxic conditions. Depleting ALKBH1 mRNA levels by shRNAs in hypoxia revealed reduced cell viability in vitro, similarly to in normoxia (Figure S7B). ALKBH1 knockdown in hypoxia impaired sphere formation capacity in a limiting dilution assay, mirroring our findings in normoxia (Figure S7C). Over expression of ALKBH1 diminished N6-mA levels in GSCs (Figure S7D). In contrast to the knockdown studies, ALKBH1 over expression did not alter cell viability, self-renewal, or in vivo tumor formation (Figures S7E-G). Although N6-mA was reduced initially, its levels return to baseline after 3 days, despite continuous over expression of ALKBH1 (data not shown). This implies that compensatory mechanisms, which likely include currently unknown DNA demethylases and methyltransferases, exist to maintain the levels of N6-mA within a relatively narrow range that is compatible with cellular survival. In summary, ALKBH1 is essential for maintaining cell viability and stemness properties under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Figure 6. ALKBH1 is essential for glioblastoma stem cell growth, self-renewal, and tumor formation capacity. See also Figure S7.

(A) (Top) Cell proliferation was assessed over a 4 day time course after treatment with a non-targeting control shRNA (shCONT) or two independent non-overlapping shRNAs (shALKBH1.1008 and shALKBH1.1551) in two human patient derived GSC models (387 and D456). Significance was determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett multiple test correction. P < 0.0001. (Bottom) Knockdown efficiency of shRNAs targeting ALKBH1 was assessed by immunoblot.

(B) (Top) Cell proliferation was assessed over a four day time course following treatment with a non-targeting control sgRNA (sgCONT) or two independent non-overlapping sgRNAs (sgALKBH1#4 and sgALKBH1#5). Significance was determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett multiple test correction. P < 0.0001. (Bottom) Immunoblot showing ALKBH1 protein level following treatment with a non-targeting control sgRNA (sgCONT) and two independent non-overlapping sgRNAs targeting ALKBH1 (sgALKBH1#4 and sgALKBH1#5).

(C) Tumorsphere formation efficiency and self-renewal capacity were measured by extreme in vitro limiting dilution assays (ELDA) in two human patient derived GSC models (387 and D456) after transduction with shCONT or shALKBH1. 387, p = 7.28e-14. D456, p = 4.19e-13.

(D) Kaplan-Meier curves depict survival of immunocompromised mice bearing intracranial tumors grown from human patient-derived GSC models (387 and D456) following transduction with shCONT or shALKBH1. Significance was determined by log-rank analysis. **, p < 0.01. N = 5 for each group.

(E) Kaplan-Meier curve depicts survival of immunocompromised mice bearing intracranial tumors grown from human patient-derived GSC models (387) following transduction with single guide RNAs (sgRNA) targeting ALKBH1 or a non-targeting control. Significance was determined by log-rank analysis. **, p < 0.01. N = 5 for each group.

To determine the clinical relevance of these findings, we performed in silico studies on the TCGA glioblastoma dataset. While correlation with patient outcome does not universally indicate the importance of any individual gene targets (Kaelin, 2017), ALKBH1 was highly expressed in glioblastomas relative to non-tumor brain tissue and associated with reduced survival and increased glioma grade (Figures 7A-C). An ALKBH1-regulated gene signature, defined by downregulated genes following ALKBH1 knockdown, correlated with tumor grade and shorter patient survival in several datasets (Figures 7D-G). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that ALKBH1 and regulation of N6-mA is necessary for glioma growth and may be a therapeutically targetable node.

Figure 7. ALKBH1 is associated with poor clinical outcomes in glioblastoma patient datasets.

(A) Relative mRNA expression levels of ALKBH1 in non-tumor brain and glioblastoma were determined in The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset. (Student’s t-test, p < 0.001)

(B) ALKBH1 gene (mRNA) expression was determined for all samples in The Cancer Genome Atlas glioblastoma and low-grade glioma datasets. The mRNA expression is plotted after dividing samples by glioma grade. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis, p < 0.001 for grade II vs grade IV and grade III vs grade IV comparisons. Grade II: n = 226; Grade III: n = 244; Grade IV: n = 150.

(C) Kaplan-Meier curve of patient survival in The Cancer Genome Atlas clinical data set. Patients are stratified by ALKBH1 expression status, with the “ALKBH1 high group” defined as patients with greater than the median ALKBH1 expression. Significance was determined by log-rank analysis. P = 0.0386. Median survival is 13.8 months for the “ALKBH1 mRNA High” group (n = 243) and 14.5 months for the “ALKBH1 mRNA Low Group (n = 245).

(D) An ALKBH1 regulated gene expression signature score was calculated for all samples in The Cancer Genome Atlas glioblastoma and low-grade glioma datasets. The signature score is plotted after dividing samples by glioma grade. Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with tukey multiple test correction. P < 0.0001 for Grade II vs. Grade IV; p < 0.0001 for Grade III vs. Grade IV; not significant for Grade II vs. Grade III. Grade II: n = 226; Grade III: n = 244; Grade IV: n = 150).

(E) Kaplan-Meier curve of patient survival in The Cancer Genome Atlas clinical data set. Patients are stratified by ALKBH1-regulated gene signature status, with the “High” group defined as patients with greater than the median value of the ALKBH1-regulated gene signature. Significance was determined by log-rank analysis. P = 0.0043. Median survival is 11.7 months for the “ALKBH1 signature High” group (n = 95) and 14.5 months for the “ALKBH1 signature Low Group” (n = 95).

(F) Kaplan-Meier curve of patient survival in the Gravendeel clinical data set. Patients are stratified by ALKBH1-regulated gene signature status, with the “High” group defined as patients with greater than the median value of the ALKBH1-regulated gene signature. (log-rank analysis. P = 0.0053)

(G) Kaplan-Meier curve of patient survival in the REMBRANDT clinical data set. Patients are stratified by ALKBH1-regulated gene signature status, with the “High” group defined as patients with greater than the median value of the ALKBH1-regulated gene signature. (log-rank analysis. P = 0.0183)

DISCUSSION

N6-mA was originally described as a DNA modification that discriminates the original and newly synthesized DNA strand in bacteria (O'Brown and Greer, 2016). We and others reported that DNA undergoes rare N6-mA modification in low and high eukaryotes (Fu et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). However, the biological function of N6-mA in human cancers remains unclear. Here we elucidated the function of N6-mA in human glioblastoma. N6-mA levels were elevated in tumor relative to normal brain tissues and in GSCs compared to normal human astrocytes, suggesting that GSCs co-opt the regulatory potential of N6-mA to promote a tumorigenic chromatin landscape. As in murine ESCs, N6-mA repressed gene expression. Our ChIP-seq results strongly associated N6-mA sites with a common heterochromatin marker H3K9me3 in glioblastoma, which has not been demonstrated previously. H3K9me3 is not involved in transcriptional silencing of N6-mA at young LINE-1s in ESCs. These results indicate that glioma cells have hijacked and further adapted N6-mA-mediated silencing mechanisms typically employed during early embryogenesis. Previous studies have implicated H3K9me3 in the regulation of DNA methylation and shown that complete removal of DNA methylation affects H3K9me3 levels and disrupts heterochromatin architecture (Du et al., 2015; Saksouk et al., 2014). Our findings corroborate the potential crosstalk between DNA N6-mA and H3K9me3 and possible collaboration of these modifications in transcription silencing in human cancers. Future experiments will inform the relationship between N6-mA, 5mC, and H3K9me3 to discern the temporal sequence of transcriptional silencing mediated by these marks. The precise roles of N6-mA and its interplay with the canonical 5mC DNA methylation mark as well as other histone modifications remain to be uncovered.

We demonstrated that ALKBH1 is a critical N6-mA demethylase that acts to regulate a number of gene networks critical to GSC identity, including the hypoxia response pathway. Most epigenetic regulation functions optimally in a specific range with either loss or gain of function leading to disruption of cellular biology. Concordantly, elevation of N6-mA levels by targeting its demethylase ALKBH1 inhibited tumor formation. Although it may appear paradoxical, both N6-mA levels as well as the N6-mA demethylase were upregulated in glioblastoma. This apparent discrepancy can be resolved by understanding that the regulation of N6-mA is a highly dynamic process that depends on both a demethylase and a (currently unknown) methyltransferase. We hypothesize that the flux of N6-mA is important, not just the absolute levels. We interrogated the role of N6-mA in glioblastoma through modulating the only known regulator of N6-mA, ALKBH1. Disruption of the dynamic regulation of N6-mA through knockdown of ALKBH1 led to decreased proliferation, self-renewal, and tumor formation capacity, suggesting that efficient regulation of N6-mA is a GSC dependency.

Although we identified the N6-mA demethylase, further studies are required to identify the methyltransferases active in glioblastoma to model N6-mA in cancer. We posit that glioblastoma cells have elevated genome-wide N6-mA levels, whereas at selected genomic loci, uncontrolled increases will be detrimental to the tumor cells. The active regulation of this modification at local sites by both a demethylase and methyltransferase likely play important roles in the tuning of biological processes. While global N6-mA enrichment is localized near genes involved in neurodevelopmental processes, those modifications that are specifically regulated by ALKBH1 tend to be localized near hypoxia response genes. It should be noted that methyl-6-adenosine (m6A) modifications of RNA have been recently reported as well, including in glioblastoma (Cui et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). The biochemical relationship between N6-mA and m6A modifications on DNA and RNA appear to be distinct.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the N6-mA DNA modification exists in human tissues, is dynamically regulated in GSCs by the DNA demethylase ALKBH1, and that maintenance of this regulatory circuitry is critical to cell survival and proliferation. Our findings reveal a new class of DNA modification in human disease and identify a potential therapeutic vulnerability that can be exploited for cancer therapy. Therefore, our results offer a novel therapeutic and discovery paradigm for deadly cancers.

METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

The authors are willing to distribute all materials, datasets, and protocols used in the manuscript. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jeremy N. Rich (drjeremyrich@gmail.com).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Glioblastoma stem cell derivation and xenograft maintenance

Glioblastoma tissues were obtained from excess surgical resection samples from patients at the Case Western Reserve University after review by neuropathology with appropriate consent and in accordance with an IRB-approved protocol (090401). All patient studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Glioma stem cell models 387 and 3565 were derived by our laboratory and transferred via a material transfer agreement from Duke University. All GSC models were cultured in Neurobasal media (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 without vitamin A (Invitrogen), EGF, and bFGF (20 ng/ml each; R&D Systems), sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies, Cat # 11360070), and glutamax (Life Technologies, Cat # 35050061). For normoxia experiments, cells were cultured in cell culture incubators at 37°C with 20% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide. For hypoxia experiments, cells were cultured in cell culture incubators at 37°C with 1% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide. To decrease the incidence of cell culture-based artifacts, patient-derived xenografts were produced and propagated as a renewable source of tumor cells for study. Xenografted tumors were dissociated using a papain dissociation system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. STR analyses were performed on each tumor model used in this study for authentication. The 3565 GSC model was derived from a glioblastoma from a 32-year old male patient. The T387 GSC model was derived from a GBM from a 76-year old female patient. The D456 GSC model was derived from a glioblastoma biopsy from an 8-year old female patient and was provided as a generous gift from Darell Bigner (Duke University). The GSC23 model was derived from a recurrent glioblastoma biopsy from a 63-year old male patient and was provided as a generous gift by Erik Sulman (MD Anderson Cancer Center). The 1919 GSC model was derived from a glioblastoma from a 53-year old male patient. The 3028 GSC model was derived from a recurrent glioblastoma from a 65-year old female patient. The 2386 tissue was derived from a glioblastoma from a 71-year old female patient. The 2752 tissue was derived from a glioblastoma from a 53-year old male patient. The 2762 tissue was derived from a glioblastoma from a 74-year old male patient.

| Glioblastoma Stem Cell

Model or Tissue |

Patient Age (Years) | Patient Sex |

|---|---|---|

| T387 | 76 | Female |

| 3565 | 32 | Male |

| D456 | 8 | Female |

| GSC23 | 63 | Male |

| 1919 | 53 | Male |

| 3028 | 65 | Female |

| 2386 | 71 | Female |

| 2752 | 53 | Male |

| 2762 | 74 | Male |

In Vivo Tumorigenesis

Intracranial xenografts were created by implanting 10,000 human-derived GSCs into the right cerebral cortex of NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) mice at a depth of 3.5 mm. All mouse experiments were performed under an animal protocol approved by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Healthy, wild-type female mice of NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) background, 4–6 weeks old, were randomly selected and used in this study for intracranial injection. Mice had not undergone prior treatment or procedures. Mice were maintained in 14 hours light/10 hours dark cycle by animal husbandry staff at the University of California, San Diego, with no more than 5 mice per cage. Housing conditions and animal status were supervised by a veterinarian. Animals were monitored until neurological signs were observed, at which point they were sacrificed. Neurological signs or signs of morbidity included hunched posture, gait changes, lethargy and weigh loss. In parallel survival experiments, mice were observed until the development of neurological signs. Healthy female mice of NSG, 4–6 weeks old, were randomly selected and used in this study for intracranial injection.

Additional experimental cell lines

293FT cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# R70007) were used to generate lentiviral particles as described in the method details section. 293FT cells were derived from embryonic kidney cells from a female human. Human astrocytes (ThermoFisher Scientific Cat#N7805100) were derived from an 18-week old female fetus and human astrocytes (SciencCell Cat#1800) were derived from a 23-week old human fetus of unknown gender (not reported by the manufacturer). The IOMM-Lee cell line was derived from a meningioma biopsy from a 61 year-old male and was provided as a courtesy of Dr. Randy Jensen (University of Utah). The CH-157MN cell line was derived from a meningioma biopsy from a 41-year old female and was a kind gift from Dr. Yancey Gillespie (University of Alabama-Birmingham). The SU-DIPG-XIII (DIPG 13) cell line was derived from a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma specimen from a 6 year-old female pretreated with XRT. The SU-DIPG-XVII (DIPG 17) cell line was derived from a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma specimen from an 8 year old male pretreated with XRT, avastin, panobinostat, and everolimus. Both DIPG cell lines were a kind gift from Michelle Monje (Stanford University). The ONS-76 cell line was derived from a medulloblastoma specimen from a 2 year-old female. The DAOY cell line was derived from a medulloblastoma specimen from a 4 year-old male. Both medulloblastoma cell lines were a kind gift from Robert Wechsler-Reya (Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute).

| Cell Model | Cell Type | Patient Age

(Years) |

Patient Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 293FT Cells | Embryonic Kidney | Embryo | Female |

| IOMM-Lee | Meningioma | 61 | Male |

| CH-157MN | Meningioma | 41 | Female |

| SU-DIPG-XIII | DIPG | 6 | Female |

| SU-DIPG-XVII | DIPG | 8 | Male |

| ONS-76 | Medulloblastoma | 2 | Female |

| DAOY | Medulloblastoma | 4 | Male |

| Human Astrocytes (Thermo Fisher) | Astrocyte | 18 weeks | Female |

| Human Astrocytes (ScienCell) | Astrocyte | 23 weeks | Unknown |

METHOD DETAILS

Enzymatic hydrolysis of DNA

The enzymatic digestion of DNA was performed as described here. One μg of genomic DNA was first spiked with uniformly 15N-labeled 2′-deoxyadenosine and D3-labeled N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine. DNA hydrolysis was performed with the addition of nuclease P1 (0.1 U), phosphodiesterase 2 (0.000125 U), erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)adenine (EHNA) (0.25 nmol) and 4.5 μL solution containing 300 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.6) and 10 mM zinc chloride to the DNA solution. Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 24 hours. A second step digestion was carried out with 0.1 unit of alkaline phosphatase, 0.00025 unit phosphodiesterase I, 6 μL of 0.5 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.9) at 37°C for 2 hours. Subsequently, the digestion mixture was neutralized by the addition of formic acid and the enzymes in the digestion mixture were removed by chloroform extraction.

LC–ESI-MS/MS and MS/MS/MS analysis

The LC-MS/MS and MS/MS/MS experiments were conducted on an LTQ-XL linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with an EASY-nLC II system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). HPLC separation was performed by employing a homemade trapping column (150 μm × 40 mm) and an analytical column (75 μm × 200 mm), both packed with Magic C18 AQ (200 Å, 5 μm, Michrom BioResource, Auburn, CA). The mass spectrometer was set up for acquiring the MS/MS of the [M + H]+ ions of 2′-deoxyadenosine (m/z 252.1) and [15N5]-2′-deoxyadenosine (m/z 257.1), as well as the MS/MS/MS for the further cleavages of the [M + H]+ ions for the nucleobase portions of N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine (m/z 150.1) and [D3]-N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine (m/z 153.1).

Dot blotting

DNA samples were denatured at 99°C for 10 minutes, cooled down on ice for 3 minutes, neutralized with 10% vol of 6.6 M ammonium acetate. Samples were spotted on the membrane (Amersham Hybond-N+, GE) and air dry for 5 minutes, followed by UV-crosslink (2× auto-crosslink, 1800 UV Stratalinker, STRATAGENE). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 2 hours at room temperature, incubated with N6-mA antibodies (1:1000, Synaptic Systems, 202-003) for 16 hours at 4°C. After 5 washes, membranes were incubated with HRP linked secondary anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:5,000, Cell Signaling 7074) for 1 hour at room temperature. Signals were detected with ECL Plus Western Blotting Reagent Pack (GE Healthcare).

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. After permeabilization, samples were treated with 2N HCl for 30 min and subsequently neutralized for 10 minutes with 0.1 M sodium borate buffer pH 8.5. Then, the samples were blocked for 2h in blocking solution (5% donkey serum in PBS, RNaseA was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml), followed by incubation with Ns-mA antibodies (1:200, Synaptic Systems, 202-003). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by species appropriate secondary antibodies (1:1000, Alexa 488; Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) with incubation for 1 hour. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, and slides were then mounted using Fluoromount (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Images were taken using a Leica DM4000 Upright microscopy.

Immunohistochemical quantification of glioblastoma tissue microarrays (TMAs)

DNA N6-mA levels in glioblastoma were investigated in glioblastoma TMAs (US Biomax, GL805b). Briefly, a TMA of deidentified formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) glioblastoma specimens was immunostained for N6-mA antibodies (1:100, Synaptic Systems, 202-003). Secondary antibodies used were EnVision labeled polymer-HRP (horseradish peroxidase) anti-mouse or anti-rabbit as appropriate. Staining was visualized using 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Each tumor was represented by three separate 2 mm cores on the TMA, with each core embedded in a separate TMA block. Each TMA core was semi-quantified on a relative scale from 0 to 3, with 0 = negative and 3 = strongest.

Vectors and lentiviral transfection

Lentiviral clones to express shRNA directed against ALKBH1 (shALKBH1.1008:TRCN0000235019, shALKBH1.1551: TRCN0000146838), or a control shRNA insert that does not target human and mouse genes (shCONT, SHC002) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The CRISPR design tool from ChopChop (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/index.php) was used to design the guide RNA (gRNA). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Fisher, and annealed and cloned into LentiCRISPR v2 plasmid, which was a gift from Dr. Feng Zhang (Addgene, plasmid 52961). The target sequence for SgRNAs used were as follows: ALKBH1 SgRNA#4: TCCGCTTCTACCGTCAGAGC, ALKBH1 SgRNA#5: GATCCTGAATTACTACCGCC. N6AMT1 SgRNA#1: GGGCTCGTACACGTCGCTGA, SgRNA#2: AAGCAGAAACGTGTCCTCCG, SgRNA#3: GGGCTGGTGGCAGAAATGGT, SgRNA#4: TTGAGGTGGAGTCACTACAT. Lentiviral particles were generated in 293FT cells in stem cell media with co-transfection with the packaging vectors pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr and pCI-VSVG (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using Cell-Titer Glo (Promega, Madison, WI). For this assay, 1,000 cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. Cells were plated in 100μL of Neurobasal media (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 without vitamin A (Invitrogen), EGF, and bFGF (20 ng/ml each; R&D Systems), sodium pyruvate, and glutamax. To assess cell viability, 40μL of the Cell-Titer Glo (Promega, Madison, WI) reagent was added to each well. Plates were placed on an orbital shaker at 100rpm for 10 minutes to promote cell lysis and covered with aluminum foil to prevent exposure to light. Plates were incubated in the dark for 2 minutes and then plates were read using a luminometer. All data were normalized to day 0 and presented as mean ± SEM.

Generation of lentiviral particles

293FT cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# R70007) were used to generate lentiviral particles through co-transfection of the packaging vectors pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr (Addgene, Plasmid # 8455) and pCl-VSVG (Addgene, Plasmid # 1733) with the appropriate overexpression, shRNA, or other plasmid. 293FT cells were seeded at a density of 1.2 million cells in DMEM, high glucose (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 11995073) in 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 26140079 with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat # 15140122). Cells were incubated for 24 hours prior to transfection. Transfection was performed using LipoD293™ In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Cat # SL100668) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 5μg each of the packaging plasmids and the plasmid of interest were combined into a tube, the transfection reagent was diluted and added followed by a 15 minute incubation. The transfection mixture was then added to the 293FT cells. Media was changed after 16 hours. Virus was collected 48 hours after media change and concentrated using the Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech Takara Bio USA, Cat # 631232) according to the manufacturers instructions. Viral supernatants were centrifuged at 1,500 x g for 45 minutes and viral pellets were frozen at −80°C for future use.

In vitro limiting dilution assay

For in vitro limiting dilution assays, decreasing numbers of cells per well (20, 10, 5, and 1) were plated in 96-well plates in neurobasal media supplemented with the components listed above. Ten days after plating, the presence and number of neurospheres in each well was quantified. Extreme limiting dilution analysis was performed using software available at http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda, as previously described.

Glioblastoma Stem Cell Differentiation

For in vitro differentiation, glioblastoma stem cells were cultured for one week in DMEM, high glucose (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 11995073) in 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 26140079 with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat # 15140122) as part of a previously established differentiation protocol. Cellular differentiation was verified by observing depleted expression of SOX2 protein by western blot.

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in hypotonic buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% NP-40; 50 mM NaF with protease inhibitors) on ice for 15 minutes and cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were mixed with reducing Laemmli loading buffer, boiled and electrophoresed on NuPAGE Gels (Invitrogen), then transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Blocking was performed for 1 hour with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST and blotting performed with primary antibodies for 16 hours at 4°C. Antibodies included ALKBH1 (Abeam, abl26596, Cambridge, MA), SOX2 (R&D Systems, AF2018), N6AMT1 (Abcam, ab173804, Cambridge, MA), GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 2118).

Patient database bioinformatics

For survival analyses, TCGA data for survival analysis was accessed through the Gliovis web portal http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/ (Bowman et al., 2017).

Intracranial tumor formation and in vivo bioluminescence imaging

GSCs were transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing ALKBH1 or a non-targeting, control (shCONT) shNRA for the knockdown experiments. 36 hours post infection, viable cells were counted and engrafted intracranially into NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice under a University of California, San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved protocol. In parallel survival experiments, animals were monitored until they developed neurological signs.

N6-mA DIP sequencing

Genomic DNA from patient-derived glioblastoma stem cell models was purified with a DNeasy kit (QIAGEN, 69504). For each sample, 5 μ g DNA was sonicated to 200–300 bp with Bioruptor. Then, adaptors were ligated to genomic DNA fragments following the Illumina protocol. The ligated DNA fragments were denatured at 95 degree for 5 minutes. Then, the single-stranded DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with N6-mA antibodies (5 μ g for each reaction, 202-003, Synaptic Systems) overnight at 4°C. N6-mA enriched DNA fragments were purified according to the Active Motif hMeDIP protocol. IP DNA and input DNA were PCR amplified with NEBNext indexing primers, and were then subjected to multiplexed library construction and sequencing with Illumina HiSeq sequencing.

ChIP-sequencing

Formaldehyde-fixed cells were lysed and sheared (Branson S220) on wet ice. The sheared chromatin was cleared and incubated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg H3K9me3 antibody (Abcam, ab8898), H3K27me3 (active motif, 39155), or H3K4me3 (Abcam) respectively. Antibody-chromatin complexes were immunoprecipitated with protein G magnetic Dynal beads (Life Technologies), washed, eluted, reverse crosslinked, and treated with RNAse A followed by proteinase K. ChIP DNA was purified using Ampure XP beads (Beckmann Coulter) and then used to prepare sequencing libraries by NEB NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina for sequencing.

ChIP-sequencing Data Analysis

Raw FASTQ files were trimmed using TrimGalore (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) and aligned to the hg19 human genome using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (Zhang et al., 2008). Identical ChIP-seq sequence reads were collapsed to a single read to avoid PCR duplicates using Picard and SamTools was used to sort and index the BAM files.

N6-mA Specific Analysis Parameters

BAM files from the N6-mA DIP-seq and matched inputs were converted to BED using the Bedtools “bamtobed”function (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). N6-mA peaks were called with the SICER algorithm (Xu et al., 2014) using the EPIC wrapper script (https://github.com/biocore-ntnu/epic) with input DIP-seq files used as a control and using the default significance cutoff of False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05. Peak intersections were calculated using the Bedtools “intersect” function (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). HOMER was used to perform genome annotation using the “annotatePeaks” function and for motif analysis using the “findMotifsGenome” function (Heinz et al., 2010). CEAS was also used for genome ontology analysis and for determining chromosome distribution of DIP-seq peaks (Ji et al., 2006). For gene set enrichment analysis, peaks were mapped to the closest transcription start site using the HOMER “annotatePeaks” function. Genes were then used as inputs into the online Gene Set Enrichment Analysis web portal (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.isp)(Subramanian et al., 2005) (Mootha et al., 2003). Pathway enrichment bubble plots were generated using the Bader Lab Enrichment Map Application (Merico et al., 2010) and Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org). For subsequent visualization of N6-mA signal, bigwig files were generated using the DeepTools “bamCoverage” script using default settings (http://deeptools.readthedocs.io/) (Ramirez et al., 2014). Signal tracks were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer, IGV (Robinson et al., 2011; Thorvaldsdottir et al., 2013). For the generation of heatmaps and profile plots, the DeepTools “computeMatrix”, “plotHeatmap”, and “plotProfile” functions were used with specific parameters given in the figure legends of the manuscript.

Histone Modification Specific Analysis Parameters

BAM files from H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments and matched inputs were converted to BED using the Bedtools “bamtobed” function (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Histone modification peaks were called with the SICER algorithm (Xu et al., 2014) using the EPIC wrapper script (https://github.com/biocore-ntnu/epic) with input ChIP-seq files used as a control and using the default significance cutoff of False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05. Intersections between N6-mA and various histone modification peaks were calculated using the Bedtools “intersect” function (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). To identify regions of gained H3K9me3 enrichments following ALKBH1 knockdown, the SICER algorithm was used as described above with the ALKBH1-knockdown H3K9me3 ChIP-seq file serving as the “treatment” file and the non-targeting shRNA H3K9me3 ChIP-seq file serving as the “control” file using default settings as described above. Reciprocally, to identify regions of lost H3K9me3 enrichments following ALKBH1 knockdown, the SICER algorithm was used as described above with the non-targeting H3K9me3 ChIP-seq file serving as the “treatment” file and the ALKBH1-knockdown H3K9me3 ChIP-seq file serving as the “control” file. Consensus gained and lost peaks were generated by identifying peaks observed in both technical replicates using the bedtools “intersect” function (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) and results are plotted as a volcano plot using the R programming language. For subsequent visualization of histone modification ChIP-seq signal, bigwig files were generated using the DeepTools “bamCoverage” script using default settings (http://deeptools.readthedocs.io/) (Ramirez et al., 2014). Signal tracks were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer, IGV (Robinson et al., 2011; Thorvaldsdottir et al., 2013). For the generation of heatmaps and profile plots, the DeepTools “computeMatrix”, “plotHeatmap”, and “plotProfile” functions were used with specific parameters given in the figure legends of the manuscript.

ALKBH1 ChIP-seq Specific Parameters

Peaks were called using the MACS2 “callpeak” function using default settings using paired-end BAM files from ALKBH1 ChIP-seq experiments using the “−f BAMPE” parameter and the default FDR-corrected q-value of 0.05 with a matched ChIP-seq input file serving as the control. The bedtools “intersect” function was used to calculate overlaps with N6-mA peaks, and the bedtools “shuffle” function was used to generate a “genome background” expected overlaps file (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). For subsequent visualization of ALKBH1 ChIP-seq signal, bigwig files were generated using the DeepTools “bamCoverage” script using default settings (http://deeptools.readthedocs.io/) (Ramirez et al., 2014). For the generation of heatmaps and profile plots, the DeepTools “computeMatrix”, “plotHeatmap”, and “plotProfile” functions were used with specific parameters given in the figure legends of the manuscript.

RNA-sequencing

Cellular RNA was extracted using the Qiagen miRNeasy Mini Kit (catalog number 217004) according to the manufacturers instructions. Total RNA was prepared for sequencing using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit. For samples treated in normoxia, FASTQ sequencing files were trimmed and then aligned to the hg19 human genome using the STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013). Differential expression analysis was performed using CuffDiff (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/cuffdiff/). For samples treated in hypoxia, FASTQ sequencing reads were trimmed using Trim Galore (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/) and transcript quantification was performed using Salmon in the quasi-mapping mode (Patro et al., 2017). Salmon “quant” files were converted using Tximport (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/tximport.html) and differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed by selecting differentially expressed genes (FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05), generating a pre-ranked list using the gene expression fold change as the ranking metric, and inputting a pre-ranked list into the GSEA desktop application (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/downloads.jsp) (Subramanian et al., 2005) (Mootha et al., 2003). Pathway enrichment bubble plots were generated using the Bader Lab Enrichment Map Application (Merico et al., 2010) and Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org).

ATAC-seq library generation

ATAC-seq was performed on 50,000 nuclei. The samples were permeabilized in cold permabilization buffer (0.2% IGEPAL-CA630 (I8896, Sigma), 1 mM DTT (D9779, Sigma), Protease inhibitor (05056489001, Roche), 5% BSA (A7906, Sigma) in PBS (10010-23, Thermo Fisher Scientific)) for 10 minutes on the rotator in the cold room and centrifuged for 5 min at 500 xg at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in cold tagmentation buffer (33 mM Tris-acetate (pH = 7.8) (BP-152, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 66 mM K-acetate (P5708, Sigma), 11 mM Mg-acetate (M2545, Sigma), 16 % DMF (DX1730, EMD Millipore) in Molecular biology water (46000-CM, Corning)) and incubated with Tagmentation enzyme (FC-121-1030; Illumina) at 37 °C for 30 min with shaking 500 rpm. The tagementated DNA was purified using MinElute PCR purification kit (28004, Qiagen). The libraries were amplified using NEBNext High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix (M0541, NEB) with primer extension at 72°C for 5 minutes, denaturation at 98°C for 30s, followed by 8 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 63°C for 30 seconds and extension at 72°C for 60 seconds. After the purification of amplified libraries using MinElute PCR purification kit (28004, Qiagen), the double size selection was performed using SPRIselect bead (B23317, Beckman Coulter) with 0.55X beads and 1.5X to sample volume. Finally, the libraries were sequenced on HiSeq4000 (Paired-end 50 cycles, Illumina).

ATAC-seq data processing

Adapter-trimmed fastq files were aligned to hg19 by Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) using parameters “−X2000 --mm --local”. After filtering by using samtools (Li et al., 2009) with “−q 30 −F 1804 −f 2”, only primary and proper mated reads were left to remove PCR duplicate by using “markduplicate” from Picard tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). The remaining mapped reads were shift +4 bp and −5 bp for “+” and “−” strand respectively to adjust for TN5 dimer so that the first base of each reads represents the cutting site. Then the peak calling was performed by using MACS2 (Zhang et al., 2008) with “−f bed −p 0.01 −shift −75 −extsize 150”. The output “narrowPeaks” were further filtered out the blacklist regions (Consortium, 2012). The detailed pipeline can be found in https://github.com/epigen-UCSD/atac_seq_pipeline, which is based on Kundaje lab’s pipeline https://github.com/kundajelab/atac_dnase_pipelines with a few small changes documented on the repo.

To calculate gained and lost peaks following ALKBH1 knockdown, ATAC-seq BAM files along with narrowpeak files were analyzed using DiffBind (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DiffBind.html) (Ross-Innes et al., 2012) and DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) to identify regions of quantitatively differential chromatin accessibility following ALKBH1 knockdown. DiffBind was used to generate MA-plots and supervised counts heatmaps. For the generation of heatmaps and profile plots, the DeepTools “computeMatrix”, “plotHeatmap”, and “plotProfile” functions were used with specific parameters given in the figure legends of the manuscript.

Bisulfite Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from human patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells and bisulfite conversion was performed. Following paired-end sequencing, FASTQ files separated into 11 paired-end fastq files to facilitate processing. Reads were trimmed using Trim Galore to remove 10bp from the 5’ and 3’ end of both reads. Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) was used to map the reads to a pre-prepared hg19 genome in the non-directional and paired-end mode. The De-duplicate function in Bismark (Krueger and Andrews, 2011) was used to remove duplicate reads. All of the mapping results from each pair of small fastq files were merged together using the samtools merge method, with the −n option to sort the reads by names. The function “bismark_methylation_extractor” was applied on the merged mapping results to extract the methylation information. The coverage2cytosine function was used to generate a genome-wide cytosine methylation report. The MakeTagDirectory function in homer was applied on the cytosine methylation report, with the option of -format bismark, -minCounts 5 –checkGC to calculate percentage of methylation in the CpG locations across the genome. The annotatePeaks.pl script from HOMER (Heinz et al., 2010) was used to obtain the methylation level of selected regions of interest. We calculated the average methylation in the 12,000 bp regions centered on the N6-mA peaks as described in the manuscript and TSS. The cytosine methylation report was also used to calculate the methylation level for each individual N6-mA peak, 1000 bp regions ahead of the TSS, and also for a bed file with shuffled chip-seq peak across the genome. Three violin plots were generated. Rank-sum test was applied between three of the distributions.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis for each plot is listed in the figure legend and/or in corresponding methods above. In brief, all grouped data are presented as mean ± s.d. All box and whisker plots of expression data are presented as median (middle line of box) ± the 25 percentile (top and bottom line of box, respectively). P-values presented are calculated by two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated and log-rank (Mantel–Cox) analysis was performed to generate P values using GraphPadPrism software (GraphPad Software). Sample sizes for each experiment are given in corresponding figures and/or methods above. Sizes were chosen based on previous experience with given experiments, or in the case of retrospective analysis, all available samples were included.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

All raw and selected processed data files are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). All data can be accessed at the SuperSeries accession number: GSE118093 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE118093). Direct links to the RNA-sequencing data can be found at the SubSeries accession number: GSE117632. Direct links to ATAC-sequencing data can be found at the SubSeries accession number: GSE118092. Direct links to ChIP-sequencing, whole genome bisulfite sequencing, and N6-mA DIP-sequencing data can be found at the SubSeries accession number: GSC119081.Additional data will be provided upon request. There are no restrictions on data availability.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Dot blot, Immunofluorescence, LC–ESI-MS/MS and MS/MS/MS analysis of N6-mA, related to Figure 1.

(A) The selected-ion chromatograms for monitoring the m/z 266.1 → 150.1 → 94.0 and m/z 269.1 → 153.1 → 94.0 transitions, which monitored the neutral losses of CH3-N=C=NH and CD3-N=C=NH from the [M + H]+ ions of N6-methyladenine (m/z 150.1) and [D3]-N6-methyladenine (m/z 153.1), respectively. Depicted in the insets of (a) are the full-scan MS/MS/MS for the protonated ions of N6-methyladenine and [D3]-N6-methyladenine, which arise from the neutral loss of a 2-deoxyribose from the [M + H]+ ions of N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine and [D3]-N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine.

(B) The selected-ion chromatograms for monitoring the m/z 252.1 → 136.1 (top) and m/z 257.1 → 141.1 transitions, which monitored the neutral losses of a 2-deoxyribose from the [M+H]+ ions of 2′-deoxyadenosine and [15N5]-2′-deoxyadenosine, respectively. Displayed in the insets of (b) are the full-scan MS/MS for the [M+H]+ ions of 2′-deoxyadenosine and [15N5]-2′-deoxyadenosine.

(C) N6-mA DNA immunofluorescence in human glioblastoma tumor tissue and matched normal brain tissue from the same patient. DAPI is used to indicate cell nuclei. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(D) Levels of the N6-mA DNA modification were assessed via DNA dot blot in (1) normal human astrocytes, (2) patient-derived diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) models (13 and 17), (3) patient-derived meningioma models (IOM-Lee, CH-157MN) and (4) medulloblastoma models (DAOY and ONS-76) using a previously validated N6-mA-specific antibody. Methylene blue was used as a DNA loading control.

Figure S2. Analysis N6-mA peaks in gene body, related to Figure 2.

(A) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the closest gene to each of the common N6-mA peaks that fall within a gene body. Values are expressed as −log10 (FDR corrected p-value).

(B) Enrichment map demonstrating key pathways identified in the GO enrichment analysis in panel (A). Circles represent individual gene sets, with the size of the circle depicting the number of genes present in the gene set.

(C) HOMER de-novo motif analysis of N6-mA peaks. “Target” shows the percentage of peaks containing the identified motif. “Background” shows the percentage of genome background regions that contain the identified motif.

(D) The distribution of CpG methylation level in N6-mA peaks (N = 17,024; median = 0.774), random genomic regions (N = 15,511; median = 0.656) and promoter regions (N = 18,023; median = 0.185). Rank-sum p-value < 1e−100 for all comparisons.

(E) The distribution of CpH methylation level in N6-mA peaks (N = 17,1086; median = 0.000558), random genomic regions (N = 15,565; median = 0.000519) and promoter regions (N = 18,046; median = 0.000483). Rank-sum p-value < 1e−60 for all comparisons.

(F) The average 5mC DNA methylation level at CpG sites at regions flanking N6-mA peaks genome wide.

(G) The average 5mC DNA methylation level at CpG sites at regions surrounding transcription start sites (TSS) genome wide.

Figure S3. Regions of N6-ma and H3K9me3 enrichments contain putative tumor suppressor elements, related to Figure 3.

(A) Visualization of N6-mA DIP-seq and H3K9me3 ChIP-seq signal surrounding the CDKN3 locus.

(B) Visualization of N6-mA DIP-seq and H3K9me3 ChIP-seq signal surrounding the RASSF2 locus.

(C) Patients in the TCGA HG-U133A microarray database were stratified based on median expression of AKAP6 into “high” (greater than or equal to the median expression, n=263) or “low” (less than median expression, n=262) groups. Survival is shown as a Kaplan-meier plot. Significance was determined by log-rank test. P = 0.0316.

(D) Log mRNA expression of AKAP6 in non-tumor tissue and glioblastoma tissue is plotted from the TCGA HG-U133A microarray database. Significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test. P < 0.001.

(E) Visualization of N6-mA DIP-seq and H3K9me3 ChIP-seq signal surrounding the AKAP6 locus.

Figure S4. N6AMT1 does not function as an N6-mA methyltransferase in patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells, related to Figure 4.

(A) Immunostaining of N6AMT1 after CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genomic knockout using 4 different sgRNAs.

(B) Dot blot showing levels of DNA N6-mA following genomic knockout of N6AMT1 using CRISPR-Cas9.

(C) Silver staining of purified Flag-N6AMT1 from overexpressed 293T cells.

(D) Dot blot showing purified Flag-N6AMT1 does not methylate the DNA oligonucleotides in vitro.

Figure S5. Overlap of N6-mA peaks with H3K9me3 peaks, related to Figure 5.

(A) Biotin labelled oligonucleotides with or without the N6-mA modification were incubated with whole cell lysates from the 387 GSC model for 1 hour followed by pull down with avidin beads. GAPDH was used as a loading control for the input.

(B) Overlap of ALKBH1 ChIP-seq peaks with consensus N6-mA ChIP-seq peaks genome wide compared to background. Permutation test was performed with 500 permutations to calculate significance, p = 0.002.

(C) Profile plot and heatmap showing overlap between ALKBH1 ChIP-seq peaks with consensus N6-mA ChIP-seq peaks genome wide

(D) Heatmap showing gained N6-mA peaks following ALKBH1 knockdown with shRNA (shALKBH1.1551) and colocalization with H3K9me3. Signal is shown over a scaled window 10 kb upstream and downstream of the gained N6-mA peak.

(E) Volcano plot showing the number of H3K9me3 peaks gained (red) and lost (blue) following ALKBH1 knockdown in the D456 GSC tumor model.

(F) Volcano plot showing the number of H3K9me3 peaks gained (red) and lost (blue) following ALKBH1 knockdown in the GSC23 GSC tumor model.

(G) and (H) Example tracks showing co-localization of gained N6-mA peaks and the H3K9me3 histone modification following ALKBH1 knockdown with two independent non-overlapping shRNAs. Two sample regions are shown in close proximity to the RFTN2 and LOX genes.

Figure S6. ALKBH1 regulated genes are enriched in hypoxia response pathways, related to Figure 5.

(A) Gene ontology enrichment analysis of differentially regulated genes following ALKBH1 knockdown with two independent non-overlapping shRNAs compared to a non-targeting control in normoxic conditions (20% oxygen). Gene set enrichments are depicted as a pathway connectivity diagram showing the pathways enriched among downregulated genes.

(B) Gene set enrichment diagrams of top downregulated gene pathways following ALKBH1 knockdown in normoxic conditions (20% oxygen). Elvidge Hypoxia Up and Manalo Hypoxia Up, FDR-corrected q-value < 0.001. The green line indicates the enrichment profile, the vertical black lines indicate genes that fall within the pathway, the gray lines indicate the ranking metric scores.

(C) Gene ontology enrichment analysis of differentially regulated genes following ALKBH1 knockdown with two independent non-overlapping shRNAs compared to a non-targeting control in hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen). Gene set enrichments are depicted as a pathway connectivity diagram showing the pathways enriched among downregulated genes.

(D) Gene set enrichment diagrams of top downregulated gene pathways following ALKBH1 knockdown in hypoxic conditions (1% oxygen). Elvidge Hypoxia by DMOG Up, FDR-corrected q-value =0.088 and Manalo Hypoxia Up, FDR-corrected q-value <0.008. The green line indicates the enrichment profile, the vertical black lines indicate genes that fall within the pathway, the gray lines indicate the ranking metric scores.

(E) Patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells were grown under hypoxia (1% oxygen) and transduced with either a control, non-targeting shRNA sequence (shCONT) or one of two shRNAs against ALKBH1. RNA-seq was then performed on the resulting cultures. Enrichment bubble plot showing pathways enriched among genes that are upregulated following ALKBH1 knockdown in hypoxia.