Abstract

Background and Purpose

Cervicocerebral vascular calcification on computed tomography angiography is a known sign of advanced atherosclerosis. However, the clinical significance of calcification pattern remains unclear. In this study we aimed to investigate the potential association between spotty calcium (SC) and acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

This study included patients with first-time nonlacunar ischemic stroke (N=50) confirmed by brain MRI or non-enhanced head CT, as well as control subjects with asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis (N=50) confirmed by carotid ultrasonography. Subjects in both groups underwent contrast-enhanced cervicocerebral CTA within a week after the initial imaging exam. Spotty calcification was evaluated at eleven arterial segments commonly affected by atherosclerosis along the carotid and vertebrobasilar circulation. Statistical analysis was performed comparing the frequency and spatial pattern of spotty calcification between the two groups.

Results

Spotty calcification in the Stroke group was markedly more prevalent than that in the Control group (total SC count: 8.74±4.96 vs 1.84±1.82, p<0.001). The odds ratio for stroke (and 95% confidence interval) was 2.49 (1.55~4.00) for spotty calcification at bilateral carotid bifurcation, 1.52 (1.13~2.04) at carotid siphon, and 1.98 (1.45~2.69) at all evaluated locations. A total number of 3 spotty calcifications was determined as the optimal cutoff threshold for increased risk of stroke. Spotty calcium showed significantly greater area under the receiver-operating characteristics curve (AUC) than that of total calcium volume irrespective of size (0.88 versus 0.77). Within the Stroke group, ipsilateral lateral side showed significantly more spotty calcium than the contralateral side (5.18±3.05 vs. 3.56±2.67, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Nonlacunar ischemia stroke was associated with markedly increased incidence of spotty calcification with a distinct spatial pattern on cervicocerebral computed tomography compared with subclinical atherosclerosis, suggesting the potential role of spotty calcification for improving the risk-stratification for ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Computed Tomography Angiography, Calcification, Acute Ischemic Stroke, Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Vascular calcification is an important component of advanced atherosclerosis and a known risk factor for stroke in the general population1-3. Cervical carotid artery calcification, along with calcifications in several specific segments of intracranial arteries such as carotid siphon and vertebral arteries are frequently observed on craniocervical computed tomography angiography (CTA). Noninvasive quantification of vascular calcification is also feasible with CTA, typically performed by visual scoring4, 5 or semiautomatic computational image analysis6. Although the pathophysiological mechanism underlying vascular calcification is not well understood, more evidence is emerging supporting the association between cervicocerebral vascular calcification (CVC) and neurovascular events including ischemic stroke7 and lacunar infarct8. However, the clinical significance of CVC remains controversial. For example, no difference was observed in the amount of cavernous calcifications between acute stroke and age-matched controls5. On the contrary, a lower degree of calcification is found in symptomatic carotid artery plaques than in asymptomatic ones, suggesting a possible indication by CVC for stable, low-risk lesions9.

Unlike the relatively limited clinical data on CVC, a large body of clinical evidence has been documented for coronary artery calcification. Extensive histological evidence has established the universal existence of calcification in culprit coronary lesions, albeit its amount is substantially variable10. Some recent studies focused particularly on the pattern of calcification, and found that small, scattered calcium deposits, known as “spotty calcifications”, have unique association with high-risk lesions. Ehara et al. reported that patients with acute myocardial infarction tend to have spotty calcifications, whereas patient with stable angina typically have much longer calcium depositions11. Tamaru et al. suggested using spotty calcification as a surrogate marker for predicting the need for future revascularization as they observed 3 times higher frequency of spotty calcifications in lesions that required revascularization compared with the ones that did not12.

To the best of our knowledge, no authors have yet investigated the potential association between spotty calcification and acute ischemic stroke. The purpose of our study, therefore, is to address this open question.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Population

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or the appropriate family members.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was determined by a power analysis based on the pilot data for this study which included 12 subjects (6 per group). In the pilot data, we observed 6.5±5.4 and 2.7±1.5 of total spotty calcium count (the main statistical comparison in this study) for the Stroke group and Control group, respectively. The effect size was determined as 0.95 for such group means and standard deviations. Assuming Type I error probability of 0.01 (α), and Type II error probability of 0.05 (1-β), the minimal sample size is 42 per group to reach statistical significance. A total of 75 consecutive stroke patients were recruited for the Stroke group which yielded 50 subjects after exclusion. The same number of subjects were recruited in the Control group.

Stroke group

In the Stroke group, 75 consecutive patients presenting with first-time acute ischemic stroke were recruited. The patients underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or non-enhanced head CT as part of their initial clinical workup followed by contrast-enhanced cervicocerebral CTA in the week afterwards. The definite diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke was confirmed by the associated symptoms and imaging results from MRI or non-enhanced CT, according to American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology guidelines13. Nonlacunar ischemic stroke in the anterior or posterior circulations were included in the Stroke group. Transient ischemic attack (TIA) and lacunar ischemic strokes were not included. Patients with previous history of stroke, cardioembolic stroke, rare causes of stroke, amaurosis fugax, carotid artery dissection or vasculitis were also excluded. A total of 50 patients were included in the final analysis.

Control group

In the Control group, 50 patients with subclinical carotid artery arteriosclerosis disease were recruited from the annual physical examination and health screening workflow at our hospital. As a part of the whole-body exam, carotid ultrasonography was performed to evaluate the risk of stroke. Patients with ultrasound-confirmed carotid artery atherosclerosis were referred for elective CTA for more detailed evaluation of the entire cervicocerebral vasculature. All patients recruited in the Control group underwent cervicocerebral CTA within a week after the initial ultrasound exam.

Imaging Protocols

Head MRI

Head MRI were performed on a 3.0T system (Signa Excite HDx, General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) equipped with an 8-channel phased array head coil. Foam pads were inserted into the space between the subject’s head and the MRI head coil to minimize head motion. The MRI protocol included routine T1WI, T2WI, T2-Flair and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). DWI was performed with a spin echo-planar sequence (field of view = 240 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm, number of slices = 18, slice gap = 1 mm, acquisition matrix = 160 × 160, b-value = 1000 s/mm²). The ADC pictures were built later by using MR host image tool14.

Non-enhanced head CT

Non-enhanced CT head scan was performed on a dual-source 64-slice CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using routine scan protocol (120 kV, 320 mA, contiguous 5 mm axial slices).

Cervicocerebral CTA

All cervicocerebral CTA examinations were performed on a 256-slice CT scanner (Brilliance iCT; Philips Healthcare, Netherlands). The patients were scanned in the caudocranial direction from the aortic arch up to the skull vertex. The following acquisition parameters were used: detector collimation 128 × 0.625 mm, slice acquisition 128 × 0.625 mm by means of a z-flying focal spot, and gantry rotation time 0.27 seconds, helical scan mode. Tube voltage and tube current were set as follows: pitch 0.9 mm, tube current 125–150 mAs per rotation, and tube voltage 100–120 kVp according to the patients’ BMI (BMI≤20/80kVp, 20< BMI<25/100 kVp, BMI≥25/120 kVp)15. Contrast media (Ultravist Solution 370 mg I/mL; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) was intravenously injected through an antecubital vein via a 20-gauge needle by a power injector (SCT-211; Medrad Inc., Indianola, PA, USA). Contrast injection timing was controlled by the bolus-tracking technique in the ascending aorta (signal attenuation threshold 100–120 Hounsfield units [HU]). Data acquisition was initiated with a mean delay of 6 seconds after the threshold in the ascending aorta was reached. A total amount of 60–80 mL of contrast material was injected at a flow rate of 4.5–5 mL/sec followed by 60 mL of saline solution.

The cervicocerebral CTA radiation dose, exclusive of the dose from the scout image and trigger radiation, was generated from the volume CT dose index and dose-length product (DLP), which were recorded automatically16. The effective radiation dose (in mSv) was estimated by multiplying the DLP by a conversion factor (k value) according to published guidelines. The values of k are dependent only on the region of the body being scanned ( k = 0.0031 mSv mGy−1 cm−1 for head and neck imaging)17.

Image Analysis

The CTA data from the Stroke group and Control group were pooled together, anonymized and randomized to avoid any bias in reading. The reviewing radiologist was blinded to the group information when analyzing the imaging data. All images were transferred to a clinical workstation (Brilliance, Philips Healthcare, Netherlands) for image analysis. Images were reconstructed using a section thickness of 0.8–1.0 mm with a hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm (iDose) 4 with interval of 0.45 mm. Volume-rendered, maximum intensity projection, multiplanar reformatted, and curved planar reformatted images were generated to evaluate the cervicocerebral arteries18.

Arterial segment selection

Previous pathological studies showed that atherosclerotic lesions are not randomly distributed along the cervicocerebral arterial tree but mostly focused only at certain segments19. We selected 11 segments commonly affected by atherosclerosis including both the carotid arterial system and the vertebrobasilar circulation. In the carotid arterial system, the bilateral common carotid artery bifurcation (Lbi and Rbi), bilateral siphon (Lsi and Rsi), and the first segment of bilateral middle cerebral artery (LMCA1 and RMCA1) were selected. In the vertebrobasilar circulation, the first and fourth segments of bilateral vertebral arteries (LV1, RV1, LV4 and RV4), as well as the basilar artery (BA) were included in the analysis (Figure I in Supplemental Material).

CTA analysis process

The CTA images were analyzed to measure the extent of spotty calcium in the entire cervicocerebral arterial tree using a custom semi-automated software package (AutoPlaque, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, CA, USA), which showed excellent reproducibility in previous coronary studies20, 21. An expert reader (10-year experience in radiology) identified and marked all lesions, their locations and measured longitudinal diameter of each lesion. MIP or MPR images are obtained of the level of the circle of Willis, the carotid bifurcations and vertebral arteries in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes. Analysis of the degree of carotid artery stenosis is based the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial criteria22.

Definition of spotty calcification

In this study, calcium is defined as a region with one or more contiguous pixels with CT attenuation equal to or greater than 130 HU in each image slice 23. Spotty calcium is defined based on the length of calcium (extent of the calcification parallel to the longitudinal direction of the vessel on curved MPR image) below 3 mm AND the maximum arc below 90°. A superficial spotty calcification is defined if it is in the area adjacent to the vessel lumen with no visible gap to the lumen on any cross-sectional images. A non-superficial spotty calcium is defined if it is laying inside of the plaque with a clear gap away from vessel lumen (Figure II in Supplemental Material).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed, using commercially available software (SPSS20.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations and categorical variables were expressed as a frequency or percentage. Comparisons between groups were performed using the one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables with normal distributions, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for continuous variables with non-normal distributions. The chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Univariable logistic regression was performed to determine the respective odds ratio of the spotty calcium counts at various vascular locations, total count of spotty calcium, and total calcium volume. The presence of first-time nonlacunar stroke was set as the dependent variable.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Clinical characteristics of the patient population enrolled in this study are included in the Supplemental Material (Table I). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was significantly higher in the Stroke group than the Control group. Otherwise, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in age, BMI, statin use, or other cardiovascular risk factors such as the presence of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, or smoking status.

Spotty Calcium Frequency and Spatial Pattern

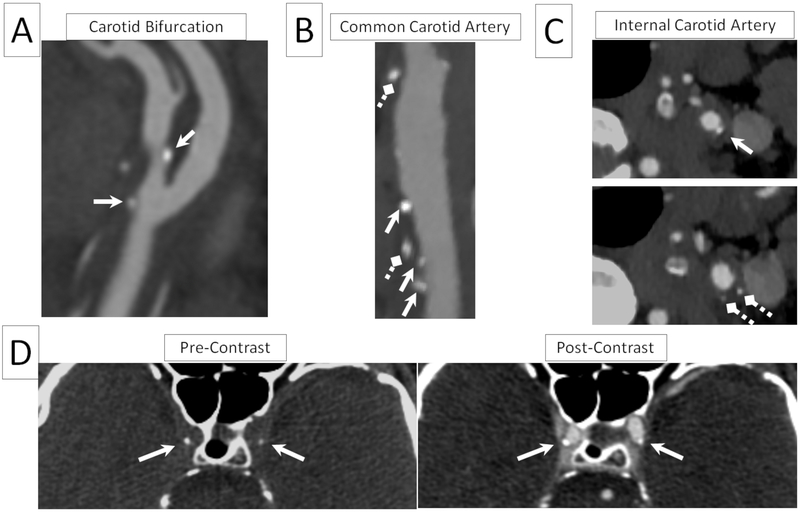

Spotty calcium was observed on cervicocerebral CTA images in both Stroke group and Control group at various vascular segments, as shown in representative examples in Figure 1A-C. The co-registered pre- and post-contrast images greatly facilitated the identification of spotty calcium and its spatial localizations, as demonstrated by the examples in Figure 1D.

Figure 1.

Representative reformatted cervicocerebral CTA images of superficial and deep spotty calcium at commonly affected vascular segments such as carotid bifurcation (A), common carotid artery (B), and internal carotid artery (C). Both superficial spotty calcium, defined as spotty calcification in immediate proximity to the lumen (pointed by the solid regular arrows), as well as deep spotty calcium (pointed by the diamond dashed arrows) were present. Both types could develop in the same vessel segment as shown in (B) and (C). Spotty calcium can be seen in both pre and post images (D), whereas arterial lumen is only visible in the post image. Assessing both images at the same time allows accurate identification of spotty calcium and its spatial location relative to arterial lumen.

Stroke group vs. Control group

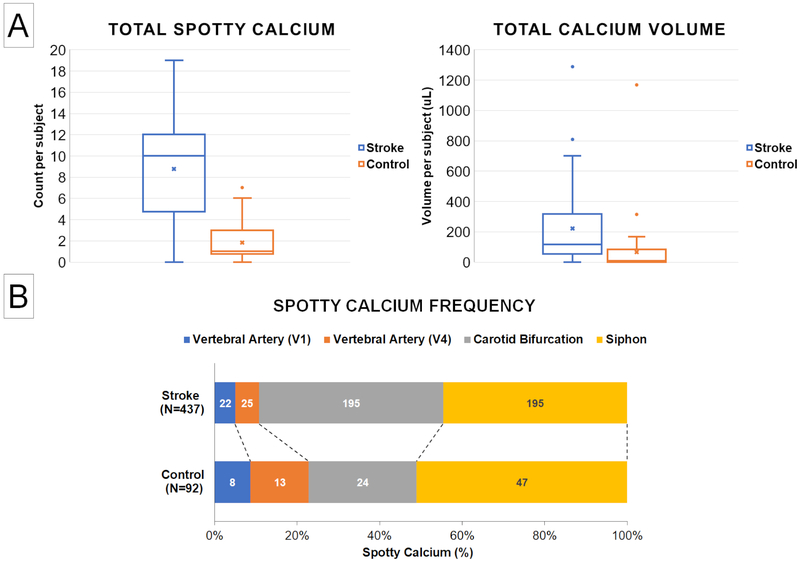

Table 1 summarizes the spotty calcification frequency per patient at all evaluated segments in the Stroke group and Control group. Notably, the total number of spotty calcifications among all evaluated vascular locations in the Stroke group was on average approximately five times as many as the Control group (p<0.001). Significantly larger amount of spotty calcification was observed in the Stroke group at each of the four evaluated vascular locations where spotty calcification was found. The global total calcification volume, including both spotty calcification and non-spotty calcification of all evaluated locations, was also larger in the Stroke group, although there were large individual variations within each group (Figure 2A).

Table 1.

Comparison of spotty calcium frequency and total calcium volume between Stroke group and Control group.

| Stroke group(N=50) |

Control group(N=50) |

Ratio | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spotty Calcium Frequency (count per patient) | ||||

| Carotid bifurcation, bilateral | 3.90±3.14 | 0.50±0.71 | 7.80 | <0.001 |

| Siphon, bilateral | 3.90±3.08 | 0.96±1.41 | 4.06 | <0.001 |

| VA1, bilateral | 0.44±0.76 | 0.14±0.40 | 3.14 | 0.016 |

| VA4, bilateral | 0.50±1.11 | 0.24±0.52 | 2.08 | 0.14 |

| MCA1, bilateral | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Basilar | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| All evaluated segments | 8.74±4.96 | 1.84±1. 82 | 4.75 | <0.001 |

| Total Calcium Volume (mm3) | ||||

| All evaluated segments | 221.6±265.3 | 65.0±171.3 | 3.41 | 0.001 |

Figure 2.

A: Comparison of total spotty calcium and total calcium volume between the Stroke group and Control group. The Stroke group showed five times as many spotty calcium compared with the Control group, whereas the difference in total calcium volume was not statistically significant. B: Comparison of spotty calcification (SC) spatial distribution patterns between the Stroke group and Control group. Each number in the bar segments represent the SC count at each corresponding vessel segment whereas the length of each bar segment represents its relative proportion to the total SC count. Although larger amount of SC was observed at every arterial segment, carotid bifurcation appeared a particularly susceptible location for SC formation in the Stroke group.

Figure 2B summarizes the spatial distribution pattern of spotty calcium found in the study population. In the Stroke group, bilateral common carotid bifurcations and siphon were the most commonly affected locations for spotty calcification, followed by the 1st and 4th segments of vertebral arteries. In the Control group, bilateral siphon presented most of the spotty calcification, followed by the common carotid bifurcation and the vertebral artery segments. No spotty calcification was observed at middle cerebral arteries or basilar artery in either group. The spatial distribution of spotty calcium was different in the Stroke group and Control group, with carotid bifurcation showing the highest increase in spotty calcium frequency in the Stroke group.

Ipsilateral side vs. Contralateral side

Within the Stroke group, both superficial and non-superficial spotty calcification could be observed on the ipsilateral side and contralateral side of the stroke in cervicocerebral vasculature, sometimes within the same vascular segment, as shown in an example in Figure 1C. However, significantly larger amount of spotty calcium was observed on the ipsilateral side compared with the contralateral side, at an overall ratio of 1.41:1 (p<0.001). Such trend was consistent for both superficial and non-superficial spotty calcification, as summarized in Table 2. The proportion of superficial spotty calcification among all spotty calcification was not statistically different between the ipsilateral side and the contralateral side.

Table 2.

Comparison of superficial and non-superficial spotty calcification frequency between ipsilateral side and contralateral side of stroke.

| Ipsilateral side (N=50) |

Contralateral side (N=50) |

Ratio | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial spotty calcification | 1.36±1.25 | 0.86±0.92 | 1.58 | 0.011 |

| Non-superficial spotty calcification | 3.82±2.61 | 2.70±2.20 | 1.41 | 0.0032 |

| All spotty calcification | 5.18±3.05 | 3.56±2.67 | 1.46 | <0.001 |

| Proportion of superficial spotty calcification | 27.3% | 25.5% | 1.07 | 0.87 |

Relationship between Spotty Calcium and Ischemic Stroke

Logistic regression analysis determined that spotty calcification count at bilateral carotid bifurcation and carotid siphon were associated with increased risk of stroke (odds ratio of 2.49 and 1.52, respectively), as shown in Table 3. The total amount of spotty calcium, combining counts from all inspected anatomical locations, also demonstrated a positive association with stroke (odds ratio of 1.98). Total calcium volume, however, did not show statistical significance in the analysis.

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of spotty calcium counts and total calcium volume for predicting the presence of stroke.

| All evaluated segments | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Spotty calcium, carotid bifurcation | 2.49 (1.55~4.00) | <0.001 |

| Spotty calcium, carotid siphon | 1.52 (1.13~2.04) | 0.005 |

| Spotty calcium, VA1 | 1.83 (0.68~4.92) | 0.23 |

| Spotty calcium, VA4 | 0.73 (0.32~1.66) | 0.46 |

| Total spotty calcium | 1.98 (1.45~2.69) | <0.001 |

| Total calcium volume (mm3) | 1.00 (0.99~1.01) | 0.11 |

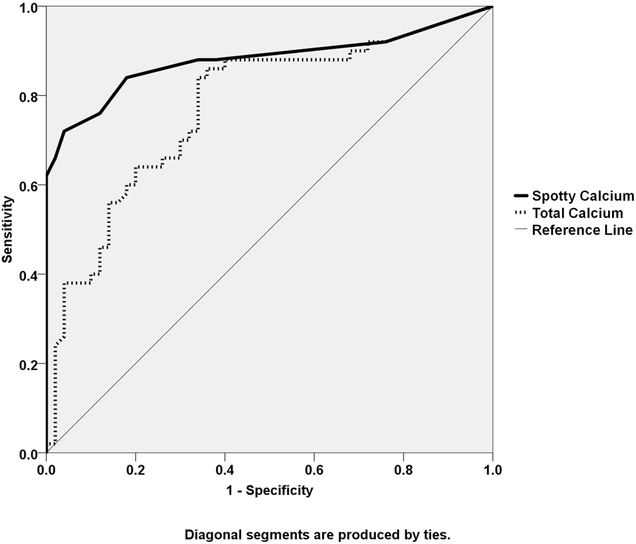

Receiver-operating characteristics analysis determined that a total number of 3 spotty calcifications was the optimal cutoff threshold for diagnosing stroke, corresponding to sensitivity and specificity at 0.84 and 0.83, respectively. The optimal cutoff threshold with total calcium volume to determine stroke was 47.8μL, corresponding to sensitivity of 0.82 and specificity of 0.66. As shown in Figure 3, the overall diagnostic value of spotty calcification was superior to that of total calcium amount, with the former showing an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.88 (95% CI:0.80~0.95) versus and AUC of 0.77 (95% CI:0.68~0.87) for the latter.

Figure 3.

Receiver operate curve (ROC) analysis showed superior diagnostic characteristics of spotty calcium count (Spotty Ca) compared with that of total calcium volume (Total Ca).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that “spotty calcium”, a specific type of small arterial calcification visible on cervicocerebral CTA, was frequently observed in patients who suffered from first-time nonlacunar stroke. Significantly greater prevalence of spotty calcium was observed in the stroke patients compared with the control population who had subclinical atherosclerosis. The total amount of spotty calcium was highly predictive of stroke.

The superior diagnostic characteristics of spotty calcium for stroke than that of total calcium volume observed in this study, indicated the additional clinical value of the differential analysis of vascular calcium, beyond a more general “whole-sale” measure of total CVC. Previous studies investigating the clinical significance of CVC mainly focused on the incidence and total amount of calcium without drawing clear distinctions between different types of arterial calcium. Chen et al were the first to report in a cross-sectional study that the incidence of intracranial arterial calcification is higher in ischemic stroke patients in an Asian cohort and its presence is an independent risk factor 24. Similarly, Bugnicourt et al reported that intracranial calcium signifies the risk of future major clinical events including both ischemic stroke and death 7. More evidence is accumulating to suggest that the amount of arterial calcium on cervicocerebral CTA can be utilized as a general indicator of the extent of atherosclerosis of head and neck vessels, and a potentially important risk factor for ischemic stroke.

However, the exact hemodynamic effects of CVC remain unclear. For example, despite the suggestion of a direct link between intracranial calcium and high-grade diseases by Kassab et al25, only a weak correlation between measures of calcium burden and the degree of luminal stenosis was found in the later study by Baradaran et al26. No significant correlation was found between intracranial vascular calcium and abnormal cerebral blood flow in the study by Sohn et al27. Its clinical significance is not well defined, either. No consensus is reached regarding whether its presence and/or extent provide any meaningful diagnostic or prognostic information beyond indicating long-standing atherosclerosis. For example, Babiarz et al reported no difference in the extent of cavernous carotid artery calcification in patients with and without infarctions in the middle cerebral artery distribution5. The mixed messages regarding the clinical significance of CVC to ischemic stroke may result partly from the well-known heterogeneity of ischemic stroke, which arises from various pathologies such as cardioembolism, atherosclerosis of the large arteries, and occlusion of the small vessels28. Another important reason could be that the simplistic measure of calcium amount all grouped in one would mix different forms of calcification with the degrees of calcification, therefore misrepresenting the clinical behavior of CVC.

Further investigation is needed to clarify the pathological nature of small spotty calcium observed on CT to better delineate its clinical significance. Extrapolating from the existing evidence on coronary arteries, we hypothesize that spotty calcium is likely to be calcified nodules in lipid-rich plaques that have extensive positive remodeling11. Thick, large pieces of calcium are more likely to be fibrocalcific plaques with thick fibrous cap overlying extensive calcium in the intima 29. Though irrelevant for the current single-center study, it is important to note that the appearance of calcium as well as its quantifications are impacted by scanner type and protocols30.

In this study, patients with nonlacunar ischemic stroke manifested a distinct spatial pattern of spotty calcium compared with the control population. Spotty calcium was frequently seen at bilateral extracranial carotid bifurcations, particularly in the Stroke group, accounting for 45% of all detected. That was a considerable increase of 20% in proportion and a remarkable 8-times increase in absolute number compared with the Control group. Such observation draws an interesting parallel with the Rotterdam study, the largest cohort study with data on cerebral calcium, which showed a stronger correlation between extracranial carotid calcification and brain infarct than intracranial calcium3. Carotid siphon is also a frequently calcified vascular area which was shown to correlate with lacunar infarction in the study by Hong et al8. In line with their findings, we observed markedly more spotty calcium at carotid siphon in the Stroke group than the Control group. There was a similar trend in both groups that about half of the observed spotty calcium was located at carotid siphon, even though the absolute amount in the Stroke group was higher. By contrast, only about 10% of the spotty calcium we observed were from vertebral arteries in the Stroke group, whereas in the Control group the proportion was over 20%. Overall, these observations suggested that not only spotty calcium was significantly more prevalent in symptomatic patients, there was possibly preferential vascular locations of the early calcification activities in the atherosclerosis process that eventually leads stroke. Further study on spotty calcium distribution in different ischemic subtypes is warranted as distinct etiologies may exist 31.

We also observed the imbalance in the distribution of spotty calcium between the ipsilateral side and contralateral side relative to the ischemic stroke region, with the ipsilateral side presenting significantly more spotty calcium. Such finding appeared in accordance with the study by Kamel et al, in which they reported greater calcium in the ICA ipsilateral to the compared with the contralateral side in patients with cryptogenic stroke32. By contrast, Babiarz et al reported no difference in CT score or thickness when comparing the infarction side versus contralateral side5. The discrepancy is possibly a result of mixing the different forms of calcifications, compared with the specific type of spotty calcium evaluated in our study. Our observation suggested inhomogeneous development and progression of atherosclerosis even in the same type of vascular beds depending on the spatial location, possibly due to different anatomical or hemodynamic predispositions, thus highlighting the importance of the disease information specific to the local lesion.

Limitations

The current results are limited by the nature of cross-sectional study, which can only probe the association between spotty calcium and clinical manifestation at a particular time point, without any suggestion of causality. However, current results warrant a further prospective study to elucidate the prognostic value of spotty calcium. Although statistical significance was reached in the main comparisons in the study, the number of patients and control subjects in the current study remain relatively low. Thus, a clinical study in a larger population is required to test the generalizability of the quantitative results including the relative risks and thresholds.

Conclusions

Compared with subclinical atherosclerosis, nonlacunar ischemia stroke is associated with high incidence of spotty calcification and a distinct spatial pattern on cervicocerebral computed tomography angiography. The specific analysis of spotty calcification may provide a potential means for improving noninvasive risk-stratification for ischemic stroke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NHLBI (R01HL096119), National Science Foundation of China (81322022, 81229001).

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosure

Dr. Berman reported grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center outside the submitted work.

Social media handles

Biomedical Imaging Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center @csmcbiri

Yibin Xie @yibinxiephd

References

- 1.Bos D, Portegies ML, van der Lugt A, Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, et al. Intracranial carotid artery atherosclerosis and the risk of stroke in whites: The rotterdam study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W Jr., et al. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, american heart association. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1995;15:1512–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos D, Ikram MA, Elias-Smale SE, Krestin GP, Hofman A, Witteman JC, et al. Calcification in major vessel beds relates to vascular brain disease. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2011;31:2331–2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodcock RJ Jr, Goldstein JH, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Phillips CD Angiographic correlation of ct calcification in the carotid siphon. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1999;20:495–499 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babiarz LS, Yousem DM, Bilker W, Wasserman BA. Middle cerebral artery infarction: Relationship of cavernous carotid artery calcification. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2005;26:1505–1511 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subedi D, Zishan US, Chappell F, Gregoriades ML, Sudlow C, Sellar R, et al. Intracranial carotid calcification on cranial computed tomography: Visual scoring methods, semiautomated scores, and volume measurements in patients with stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2015;46:2504–2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugnicourt JM, Leclercq C, Chillon JM, Diouf M, Deramond H, Canaple S, et al. Presence of intracranial artery calcification is associated with mortality and vascular events in patients with ischemic stroke after hospital discharge: A cohort study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:3447–3453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong NR, Seo HS, Lee YH, Kim JH, Seol HY, Lee NJ, et al. The correlation between carotid siphon calcification and lacunar infarction. Neuroradiology. 2011;53:643–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwee RM. Systematic review on the association between calcification in carotid plaques and clinical ischemic symptoms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke AP, Weber DK, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Taylor AJ, Virmani R. Pathophysiology of calcium deposition in coronary arteries. Herz. 2001;26:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, Shimada K, Shimada Y, Fukuda D, et al. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: An intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–3429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamaru H, Fujii K, Fukunaga M, Imanaka T, Miki K, Horimatsu T, et al. Impact of spotty calcification on long-term prediction of future revascularization: A prospective three-vessel intravascular ultrasound study. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:881–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, et al. 2015 american heart association/american stroke association focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2015;46:3020–3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Y, Han Q, Ding X, Chen Q, Ye K, Zhang S, et al. Defining core and penumbra in ischemic stroke: A voxel- and volume-based analysis of whole brain ct perfusion. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo S, Zhang LJ, Meinel FG, Zhou CS, Qi L, McQuiston AD, et al. Low tube voltage and low contrast material volume cerebral ct angiography. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:1677–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Z, Wang X, Duan Y, Wu L, Wu D, Chao B, et al. Low-dose prospective ecg-triggering dual-source ct angiography in infants and children with complex congenital heart disease: First experience. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JM, Reed MS, Burbank HN, Filippi CG. Quality of extracranial carotid evaluation with 256-section ct. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1626–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang JL, Liu BL, Zhao YM, Liang HW, Wang GK, Wan Y, et al. Combining coronary with carotid and cerebrovascular angiography using prospective ecg gating and iterative reconstruction with 256-slice ct. Echocardiography. 2015;32:1291–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohr JP, Albers GW, Amarenco P, Babikian VL, Biller J, Brey RL, et al. American heart association prevention conference. Iv. Prevention and rehabilitation of stroke. Etiology of stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1997;28:1501–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dey D, Cheng VY, Slomka PJ, Nakazato R, Ramesh A, Gurudevan S, et al. Automated 3-dimensional quantification of noncalcified and calcified coronary plaque from coronary ct angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3:372–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuhbaeck A, Dey D, Otaki Y, Slomka P, Kral BG, Achenbach S, et al. Interscan reproducibility of quantitative coronary plaque volume and composition from ct coronary angiography using an automated method. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:2300–2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dey D, Achenbach S, Schuhbaeck A, Pflederer T, Nakazato R, Slomka PJ, et al. Comparison of quantitative atherosclerotic plaque burden from coronary ct angiography in patients with first acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shemesh J, Evron R, Koren-Morag N, Apter S, Rozenman J, Shaham D, et al. Coronary artery calcium measurement with multi-detector row ct and low radiation dose: Comparison between 55 and 165 mas. Radiology. 2005;236:810–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen XY, Lam WW, Ng HK, Fan YH, Wong KS. Intracranial artery calcification: A newly identified risk factor of ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17:300–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassab MY, Gupta R, Majid A, Farooq MU, Giles BP, Johnson MD, et al. Extent of intra-arterial calcification on head ct is predictive of the degree of intracranial atherosclerosis on digital subtraction angiography. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baradaran H, Patel P, Gialdini G, Giambrone A, Lerario MP, Navi BB, et al. Association between intracranial atherosclerotic calcium burden and angiographic luminal stenosis measurements. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2017;38:1723–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sohn YH, Cheon HY, Jeon P, Kang SY. Clinical implication of cerebral artery calcification on brain ct. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:332–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu XH, Chen XY, Wang LJ, Wong KS. Intracranial artery calcification and its clinical significance. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12:253–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: A comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000;20:1262–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detrano RC, Anderson M, Nelson J, Wong ND, Carr JJ, McNitt-Gray M, et al. Coronary calcium measurements: Effect of ct scanner type and calcium measure on rescan reproducibility--mesa study. Radiology. 2005;236:477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dijk AC, Fonville S, Zadi T, van Hattem AM, Saiedie G, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Association between arterial calcifications and nonlacunar and lacunar ischemic strokes. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45:728–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamel H, Gialdini G, Baradaran H, Giambrone AE, Navi BB, Lerario MP, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and nonstenosing intracranial calcified atherosclerosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:863–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.