Abstract

Aims:

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by degeneration of cholinergic basal forebrain (CBF) neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM), which provides the major cholinergic input to the cortical mantle and is related to cognitive decline in patients with AD. Cortical histone deacetylase (HDAC) dysregulation has been associated with neuronal degeneration during AD progression. However, whether HDAC alterations play a role in CBF degeneration during AD onset is unknown. We investigated HDAC protein levels from tissue containing nbM and changes in nuclear HDAC2 and its association with neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) development during AD progression.

Methods:

We used semi-quantitative western blotting and immunohistochemistry to evaluate HDAC and sirtuin (SIRT) levels in individuals that died with a premortem clinical diagnosis of no cognitive impairment (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild/moderate AD (mAD), or severe AD (sAD). Quantitative immunohistochemistry was used to identify HDAC2 protein levels in individual cholinergic nbM nuclei and their colocalization with the early phosphorylated tau marker AT8, the late-stage apoptotic tau marker TauC3, and Thioflavin-S, a marker of β-pleated sheet structures in NFTs.

Results:

In AD patients, HDAC2 protein levels were dysregulated in the basal forebrain region containing cholinergic neurons of the nbM. HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity was reduced in individual cholinergic nbM neurons across disease stages. HDAC2 nuclear reactivity correlated with multiple cognitive domains and with NFT formation.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that HDAC2 dysregulation contributes to cholinergic nbM neuronal dysfunction, NFT pathology, and cognitive decline during clinical progression of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, basal forebrain, epigenetics, histone deacetylases, mild cognitive impairment, neurofibrillary tangles, nucleus basalis of Meynert, sirtuins

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by degeneration of cholinergic basal forebrain (CBF) neurons(1) in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM),(2–8) which are the main source of acetylcholine in the cortical mantle.(9) Cholinergic neuron loss in the nbM contributes to cognitive and attentional deficits (8, 10) and correlates with disease severity in AD.(11–13) Alterations in the balance between the high-affinity trkA (cell survival) and the low-affinity pan neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) (cell death) nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors(14, 15), dysregulation of NGF metabolism (16–18) and development of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) pathology(19–22) have been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of CBF neurons in AD. Interestingly, histone acetylation and deacetylation have been shown to be involved in the regulation of the expression of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), the synthetizing enzyme for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine,(23–25) suggesting a role for epigenetics in the selective vulnerability of cholinergic nbM neurons in AD.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs), a class of enzymes with deacetylase activity, are found in the nucleus and cytoplasm and are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of AD.(26–30) Multiple HDAC classes are associated with cellular events that are dysfunctional in AD, including endoplasmic reticulum stress (HDAC4),(31) autophagic regulation (HDAC6),(32) mitochondrial transport (HDAC6),(33) tau hyperphosphorylation (HDAC6), (30) and amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau accumulation (SIRT1).(34, 35) Studies also indicate that dysregulation of HDACs is associated with brain regions susceptible to NFT formation, including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, in AD.(26, 36) Although reports indicate that basal forebrain pathology precedes and predicts cortical pathology and memory impairment (37, 38) whether epigenetic dysregulation occurs and associates with the formation of NFTs in nbM cholinergic neurons is unknown.

Of the various HDACs, HDAC2 has received extensive investigation because of its role in the regulation of genes involved in learning and memory via modulation of chromatin plasticity.(39–41) Immunohistochemical analysis of HDAC1 and HDAC2 has revealed decreased reactivity in the entorhinal cortex.(36) However, HDAC2 (but not HDAC1 or HDAC3) is increased in the nuclei of CA1 hippocampal and entorhinal cortex neurons in AD compared with HDAC2 in non-cognitively impaired aged controls.(26) A western blotting study of the frontal cortex revealed significant increases in HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC4, and HDAC6 in MCI and mAD compared with those in NCI whereas HDAC2 levels remained stable across clinical groups (42). Conversely, cortical SIRT1 levels decreased during disease progression.(42) However, to our knowledge, no reports have examined HDAC modifications in the basal forebrain region containing the cholinergic cortical projection neurons during the progression of AD and their relation to cognitive performance and neuropathological criteria.

In the present study, we investigated the role of HDACs, especially HDAC2, in cholinergic nbM neuronal degeneration during the progression of AD. Using semi-quantitative western blotting, we analysed global levels of HDACs and SIRT1 proteins in basal forebrain tissue containing the nbM obtained from individuals who died with an antemortem clinical diagnosis of no cognitive impairment (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild/moderate AD (mAD), and severe AD (sAD) and who received a postmortem neuropathological diagnosis. In addition, we examined HDAC2 immunoreactivity and its association with early (AT8) and late (TauC3) tau epitopes that mark NFT evolution (21, 43–47) in individual nbM cholinergic neurons in tissue from the same clinicopathological groups. Our data provide evidence that reduced HDAC2 levels in the nbM are coincident with early posttranslational tau modifications in prodromal AD (MCI), which are associated with cognitive decline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Frozen and free-floating tissue containing nbM CBF neurons was obtained from individuals who died with an antemortem clinical diagnosis of NCI (n=20), MCI (n=13), or mild/moderate AD (n=12) from the Rush Religious Orders Study (RROS).(10, 48–50) Additional cases with a diagnosis of severe AD (n=16) were obtained from the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center (RADC). The Human Research Committees of Rush University Medical Center approved this study, and written informed consent for research and autopsy was obtained from the participants or their family or guardians.

Clinical and Neuropathologic Evaluations

Details of the clinical evaluation of the RROS cohort have been reported previously.(10, 48, 49, 51) Briefly, a team of investigators led by a neurologist performed annual neurological examinations and a cognitive battery in addition to reviewing each participant’s medical history. The average time from the last clinical evaluation to death was about 8 months. Neuropsychological testing included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Global cognitive score (GCS), and a composite z-score compiled from a battery of 19 cognitive tests,(49) including episodic memory z-score, semantic memory z-score, working memory z-score, perceptual speed z-score, and visuospatial ability z-score.(52) The 13 MCI cases had cognitive impairment insufficient to meet the criteria for dementia.(50) MCI subtypes include: amnestic MCI (aMCI) which is characterized by memory impairment and progresses to AD at a higher rate than non-amnestic (naMCI), which involves a cognitive domain(s) other than memory such as executive function, language, and visuospatial processing. Amnestic and non-amnestic MCI can be subcategorized into single (sdMCI) or multiple domain MCI (mdMCI) depending on how many cognitive domains are affected (53). Of the 13 MCI cases, 6 were amnestic and 7 were non-amnestic. A final clinical diagnosis applied to our cases was assigned after a team of neurologists and neuropsychologists reviewed the clinical data. Neuropathological diagnosis was based on Braak staging of NFTs,(54) the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Reagan criteria,(55) and recommendations of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD).(56) The recent criteria for the diagnosis of AD are currently being applied to all RROS cases.(57) Participants were excluded if they had mixed pathologies other than AD (e.g., TAR DNA-binding protein 43, large strokes, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, hippocampal sclerosis).

Semi-Quantitative Immunoblotting

Frozen basal forebrain regions were dissected rostrally at the crossing of the anterior commissure, and caudally where the anterior commissure recedes into the temporal pole containing the anterior, anterior medial and lateral and intermediate subregions of the nucleus basalis. Dissections did not include the hypothalamus, ventral globus pallidus, or the ventral putamen. Frozen tissue samples containing the nbM were denatured in sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) loading buffer to a final concentration of 5 mg/ml. Proteins (50 μg/sample) were separated by 4–20% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; Lonza, Rockland, ME) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Immobilon P, Millipore, Billerica, MA) electrophoretically.(10, 58) Membranes were first blocked in tris-buffered saline (TBS)/0.05%Tween-20/5% milk for 60 minutes at room temperature and primary antibodies against HDAC 1, 2, 3 and 4, HDAC6, and SIRT1 were added to the blocking buffers. A summary table describing the antibodies and their characteristics is shown in Table S1. Membranes were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes; and then incubated overnight at 4°C. After membranes were washed in TBS/0.05% Tween-20, they were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (1:5,000 and 1:3,000, respectively). Immunoreactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL) on a Kodak Image Station 440CF (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) and bands quantified with Kodak 1D Image Analysis Software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Basal forebrain protein immunoreactive signals were normalized to β-tubulin signals. Samples were analysed in three independent experiments, and only one band was visualized at the appropriate kilodalton (kDa) weight for each antibody. Controls included elimination of primary antibodies, resulting in no observable immunoreactivity.

HDAC2 Immunohistochemistry

Free-floating basal forebrain sections containing the cholinergic subfields termed Ch4 anteromedial, anterolateral, and intermediate were used for immunohistochemical analysis.(1) Serial 40-μm thick sections were washed in PBS and TBS, and then incubated in 0.1 mol/L sodium metaperiodate for 20 minutes (Sigma, St. Louis, IL) to inactivate endogenous peroxidase activity. Tissue was washed in a TBS solution with 0.25% Triton X (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and placed in TBST/Triton 3% goat serum for 1 hour. Sections were then incubated with an HDAC2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500 dilution; Table S1) overnight in a solution of 0.25% Triton X-100 and 1% goat serum. All washes and incubations were performed at room temperature on a shaker table. Sections were then washed in TBS and 1% goat serum before incubation with a biotinylated secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour. After TBS washes, HDAC2 staining was amplified using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour, rinsed in a 0.2 mol/L sodium acetate solution, 1.0 mol/L imidazole buffer (pH 7.4) and developed in an acetate-imidazole buffer containing 0.05% DAB (Sigma, St. Louis, IL) and 0.0015% H2O2. Histochemical reaction was terminated in an acetate-imidazole buffer, then tissue was mounted on slides and dehydrated through graded alcohols (70%−95%−100%), cleared in xylene, and cover-slipped using DPX mounting medium (Biochemica Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Immunohistochemical controls included deletion of the primary antibody, resulting in no observable immunoreaction. Additional HDAC2-immunoreactive (HDAC2-ir) sections were counterstained with cresyl violet to aid cytoarchitectural analysis. For each antibody, staining of all sections was performed at the same time to reduce reagent batch-to-batch variability.

Quantitation of HDAC2 Immunoreactivity

Quantitative HDAC2-ir was performed in 11 NCI, 11 MCI, 10 mAD, and 9 sAD cases, with an average of 6 slides per case and 50 cells per slide. More than 50% of these cases overlapped with the cohort used for western blotting. Measurements were performed blinded to clinical and pathological diagnosis. Cholinergic neurons containing nuclei positive for HDAC2-ir were identified by location and morphology using parallel sections counterstained with cresyl violet. HDAC2-ir nuclear area and intensity measurements were obtained using a Nikon Microphot-FXA microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) at 40 × magnification. An average background value was obtained from 5 microscopic fields lacking HDAC2-ir profiles to yield an average background value, which was subtracted from HDAC2-ir measurements.

Dual p75NTR and AT8 Immunohistochemistry

Adjacent sections were dual immunostained for the pan neurotrophin receptor, p75NTR, an excellent marker for human nbM neurons,(6) and with the tau pretangle marker AT8 (phosphorylated at Ser202 and Thr205). After development of the first antigen (p75NTR, 1:500), tissue was soaked in an avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories). Prior to co-staining, any remaining peroxidase activity was further quenched with 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Blocking buffer was reapplied for 1 hour at room temperature, and tissue was then incubated in the AT8 antibody (1:800) overnight at room temperature. Tissue was then incubated with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200) for 1 hour at room temperature and placed in an ABC solution as described above. All tissue was developed with the Vector SG Substrate Kit (blue-gray reaction product, Vector Laboratories). Tissue was mounted on slides, dehydrated through a graded series of alcohols, and coverslipped. Immunohistochemical controls were performed to rule out any cross-reactivity or non-specific staining, including omission of the primary and secondary antibodies. Controls were negative for immunoreactivity (data not shown). The tissue was not prepared for unbiased stereological counting.

Quantitation of nbM NFT Profiles

Counts of single p75NTR and AT8 and double AT8/p75NTR neurons within the nbM were performed in the same cases used for single HDAC2 immunostaining. An average of 5 sections per case was analysed using the Nikon Microphot-FXA microscope at 20× magnification. For each antibody, counts of all AT8- and AT8/p75NTR-labeled neurons were averaged per case, as described previously(51) and normalized to the total number of p75NTR-positive neurons. Fiduciary landmarks were used to prevent repetitive counting of labelled profiles.

Triple Immunofluorescence and Thioflavin-S Histochemistry

Immunofluorescence was conducted using additional free-floating nbM sections from the same cases used for single HDAC2 and dual p75NTR/AT8 immunohistochemistry. Sections were washed 3× for 10 minutes each in PBS, TBS, and TBS/Triton (0.25%), blocked in TBS/Triton/3% donkey serum for 1 hour at room temperature, and incubated overnight in TBS/Triton/1% donkey serum and the primary antibodies (p75NTR, HDAC2, AT8, or TauC3), then washed in TBS/1% donkey serum, and incubated in TBS/1% donkey serum containing the appropriate secondary antibody for 3 hours at room temperature. Sections were then washed, mounted on glass slides, and dried overnight in the dark. The following day, the sections were defatted in equal parts chloroform and 100% ethanol for 1 hour, rehydrated through graded alcohols (10 seconds), and then put in dH2O for 5 minutes. Slides were then placed in 0.02% Thioflavin-S for 20 minutes in the dark, differentiated in 80% ethanol for 30 minutes, incubated with an autofluorescence eliminator reagent to eliminate lipofuscin autofluorescence (Millipore, Temecula, CA), and coverslipped with Aqua-Mount (Lerner Laboratories, Cheshire, WA).

HDAC2 immunofluorescent nuclear intensity was measured in nbM neurons positive for p75NTR, p75NTR/AT8, p75NTR/TauC3, p75NTR/AT8/Thioflavin-S, and p75NTR/TauC3/Thioflavin-S. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using an Echo Revolve R4 microscope (San Diego, CA) at 40× magnification and HDAC2 intensity was analysed with ImageJ 1.47v. Background measurements were taken and subtracted from all nuclear measurements as described above. Photomicrographs were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Oberkochen, Germany) at 40× and 63× magnifications.

Statistical Analysis

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare differences between clinical groups, age at death, education, postmortem interval, brain weight at autopsy, and time between last clinical assessment and autopsy, as well as immunoblotting data, neuronal counts, immunoreactive intensity, and nuclear area. Chi-squared analysis was used to determine whether frequency differences for sex, apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 carrier status, Braak stage, CERAD diagnosis, and NIA-Reagan diagnosis were present across clinical groups. The Conover-Iman test was used to discern statistically significant groupwise comparisons. Associations between nuclear area and immunoreactive intensity with demographic, cognitive, and neuropathological variables were assessed using Spearman correlations. Spearman correlation was also used to assess within-group correlations of the cognitive measures with HDAC2. A Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of alpha = 0.007 was used to correct for multiple comparisons within each of the clinical groups. The false discovery rate (FDR) was used to correct for multiple comparisons in the correlation analyses to maintain a significance level of p < 0.05.(59) FDR adjustments were applied to all comparisons to avoid type I error.

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical, and Neuropathological Characteristics

Demographic, cognitive, and postmortem characteristics of each clinical group are presented in Table 1. The sAD group had a significantly younger age at death (78.75±9.10 years) compared with the MCI group (89.97±4.71 years, p = 0.01) and the mAD group (89.90±5.18 years, p = 0.01). Since the sAD group had a significantly younger age of death compared to the mAD and MCI groups, it is important to note is that the current study was not just comparing different stages in disease progression, but also different disease trajectories/ages of onset. For example, the 78-year-old sAD represented the most aggressive trajectory and the 89-year-old MCI the least aggressive. No statistically significant differences in groups were found for frequency of sex (p = 0.10), APOE ε4 carrier status (p = 0.28), years of education (p = 0.87), postmortem interval (p = 0.54), and brain weight at autopsy (p = 0.26). Limited demographic information was available for the RADC sAD cases. The mean postmortem interval for the sAD group was 6.78±4.24 (range 2–17.3) hours, 50% were female, and the mean brain weight was 1,077.30±134.71 (range 925–1325) grams.

Table 1.

Demographic and Cognitive Variables.

| NCI | MCI | mAD | p-value | Groupwise Comparisons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 13 | 12 | - | - |

| Age at Death (years) | 86.02±6.18 | 89.97±4.71 | 89.90±5.18 | 0.01 | MCI>NCI |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 12/8 | 3/10 | 3/9 | 0.10 | - |

| ApoE ε4 (Carrier/Non-Carrier) | 4/15* | 1/12 | 4/8 | 0.28 | - |

| Education (years) | 17.60±4.39 | 17.38±2.47 | 17.67±3.34 | 0.87 | - |

| MMSE | 28.15±1.49 | 25.76±2.84 | 18.67±5.37 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI>mAD |

| Global Cognitive Score (z-score) | 0.25±0.43 | −0.56±0.35 | −1.49±0.56 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI>mAD |

| Episodic Memory (z-score) | 0.58±0.52 | −0.46±0.62 | −1.51±0.99 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI>mAD |

| Semantic Memory (z-score) | 0.22±0.58 | −0.46±0.63 | −1.06±0.92 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI, NCI>mAD |

| Working Memory (z-score) | 0.00±0.54 | −0.49±0.65 | −1.24±0.93 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI, NCI>mAD |

| Perceptual Speed (z-score) | −0.35±0.84 | −0.77±0.75 | −1.96±0.92 | <0.001 | NCI>mAD, MCI>mAD |

| Visuospatial (z-score) | 0.23±0.62 | −0.97±0.73 | −0.79±0.70 | <0.001 | NCI>MCI, NCI>mAD |

| Post-Mortem Interval (hours) | 5.98±1.58 | 5.61±2.23 | 5.45±2.33 | 0.54 | - |

| Brain Weight at Autopsy (grams) | 1,225.05±175.00 | 1,156.77±96.46 | 1,117.09±102.32 | 0.26 | - |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; PMI, Postmortem Interval; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NCI, no cognitive impairment.

One individual did not APOE genotype data.

Although the mAD group displayed significantly lower MMSE and GCS test scores than the NCI and MCI groups (p < 0.001, Table 1), the latter 2 groups were not significantly different (p = 0.07). A similar relationship was noted for episodic memory, with the mAD group scores significantly lower than those of the NCI and MCI groups (p < 0.001), whereas the MCI scores were significantly lower than those of the NCI group (p = 0.01). For semantic memory and visuospatial ability, the NCI group had significantly higher scores than both the MCI and mAD groups (p < 0.001). For working memory, the NCI group had significantly higher scores than both the MCI (p = 0.04) and mAD (p < 0.001) groups, whereas the MCI group scores were not significantly different from those of the mAD group (p = 0.06). No significant differences were noted for perceptual speed between the NCI and MCI groups (p = 0.87), whereas the mAD group had significantly lower scores than both the MCI and NCI groups (both p < 0.001). Limited cognitive data were available for the RADC sAD group. The mean MMSE score for this group was 2.50 ± 3.57 (range 0–9).

Neuropathological data for the NCI, MCI, and mAD groups are shown in Table 2. No significant differences were found for total neuritic (p = 0.18) or diffuse (p = 0.23) plaque counts, total NFT counts (p = 0.28), CERAD (p = 0.31), Braak Stage (p = 0.17), or NIA Reagan (p = 0.37) among MCI, mAD, and NCI groups. Limited neuropathological data were available for the sAD group. More than 70% of sAD cases were determined to be Braak IV, the rest were Braak stage V.

Table 2.

Neuropathological Characteristics

| NCI | MCI | mAD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Neuritic Plaque Count | 17.50 [0, 43] | 33 [0, 90.25] | 55.50 [3, 132.50] | 0.18 |

| Total Diffuse Plaque Count | 18 [0, 65] | 25 [0.75, 52.50] | 66 [11.50, 91] | 0.23 |

| Total Neurofibrillary Tangle Count | 17.50 [7.50, 44] | 28 [20.75, 66.50] | 44.50 [5.50, 106] | 0.28 |

| CERAD Neuropathological Diagnosis | ||||

| No AD | 9 | 4 | 3 | |

| Possible AD | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0.31 |

| Probable AD | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Definite AD | 2 | 3 | 6 | |

| Braak Stage | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| I | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| II | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0.17 |

| III | 4 | 5 | 1 | |

| IV | 9 | 5 | 3 | |

| V | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| NIA Reagan Diagnosis | ||||

| Not AD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.37 |

| Low Likelihood | 11 | 6 | 4 | |

| Intermediate Likelihood | 8 | 5 | 5 | |

| High Likelihood | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

Median [25th %ile, 75th %ile]; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NCI, no cognitive impairment; NIA, National Institute on Aging.

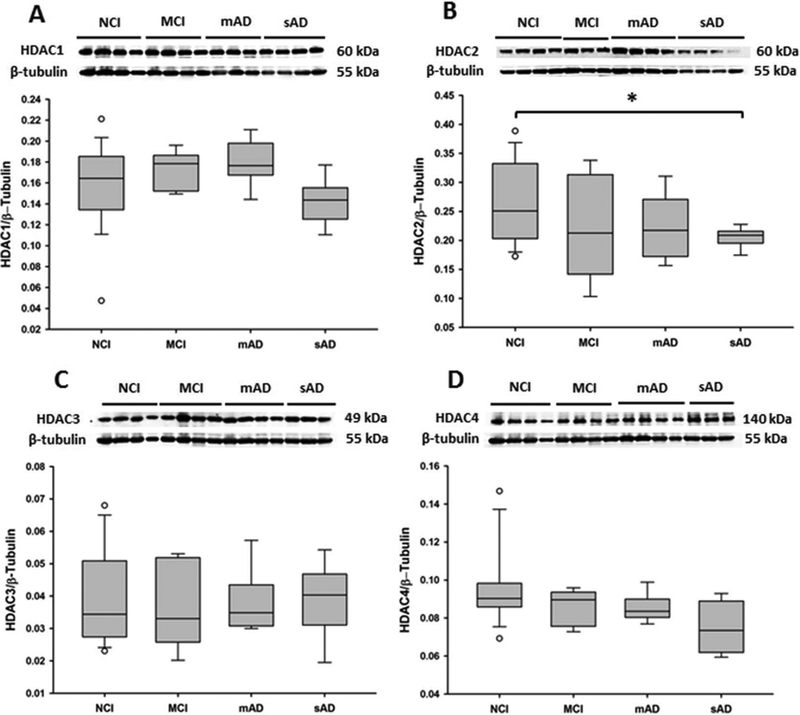

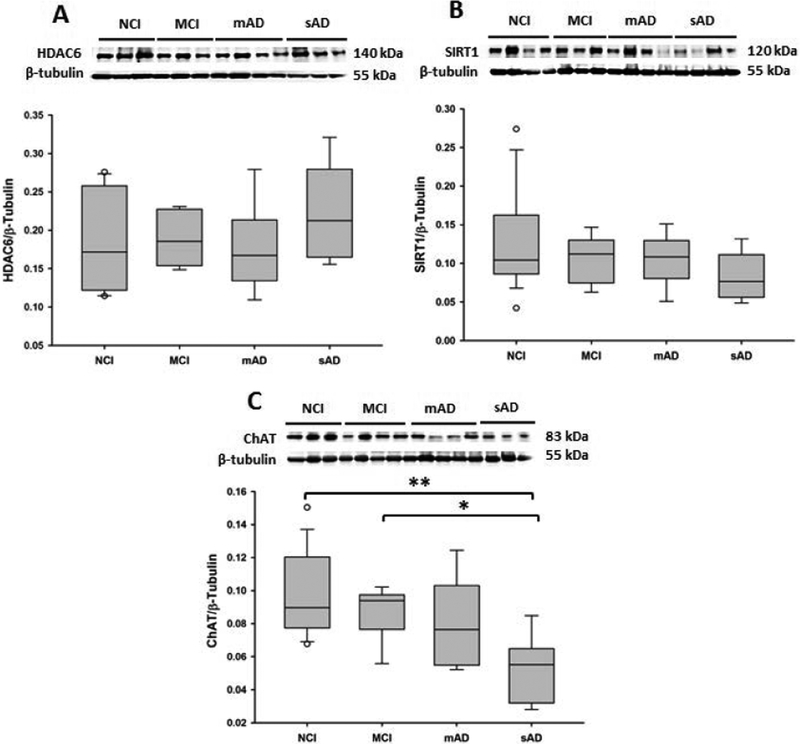

Reduction in Basal Forebrain HDAC2 and ChAT Protein Levels During AD Progression

Semi-quantitative western blotting was used to identify alterations in HDAC and SIRT protein levels in the basal forebrain region containing the nbM (Figure 1). HDAC1, HDAC3 (p = 0.29; p = 0.92, respectively, Figure 1A, C), HDAC4, HDAC6, and SIRT1 (p = 0.18, p = 0.46, p = 0.20) levels were stable, whereas HDAC2 levels were significantly decreased in the sAD group compared with the NCI, MCI, and mAD groups (p = 0.03, Figure 1B). HDAC2 levels in mAD did not reach significance, however, there was a trend for an increase compared to the NCI and MCI groups (p = 0.12, Figure 1B). ChAT levels (Figure 2C) were significantly decreased in the sAD group compared with the NCI (p < 0.001) and MCI (p = 0.04) groups. ChAT levels were not significantly different between the mAD and sAD groups (p = 0.07).

Figure 1.

Representative immunoblots and box plots of levels of (A) HDAC1, (B) HDAC2, (C) HDAC3, and (D) HDAC4 in the basal forebrains of non-cognitively impaired (NCI), mild cognitively impaired (MCI), mild/moderate AD (mAD), and severe AD (sAD). Immunoreactive signals obtained by densitometry were normalized to levels of β-tubulin. (A) HDAC1 levels were stable across clinical groups. (B) HDAC2 levels were significantly decreased in the sAD group compared with those in the NCI group (p = 0.03). (C) HDAC3 and (D) HDAC4 levels did not change significantly across groups. Circles in box plots indicate outliers. Asterisk indicates p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Representative immunoblots and box plots of (A) HDAC6, (B) SIRT1, and (C) ChAT basal forebrain levels in the non-cognitively impaired (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild/moderate AD (mAD), and severe AD (sAD) groups. Immunoreactive signals obtained by densitometry were normalized to levels of β-tubulin. HDAC6 (A, p = 0.46) and SIRT1 (B, p = 0.20) levels were stable across clinical groups. (C) ChAT levels were significantly decreased in the sAD group compared with those in the NCI (p < 0.001) and MCI (p = 0.04) groups. Circles in box plots indicate outliers. One asterisk indicates p < 0.05. Two asterisks indicate p < 0.001.

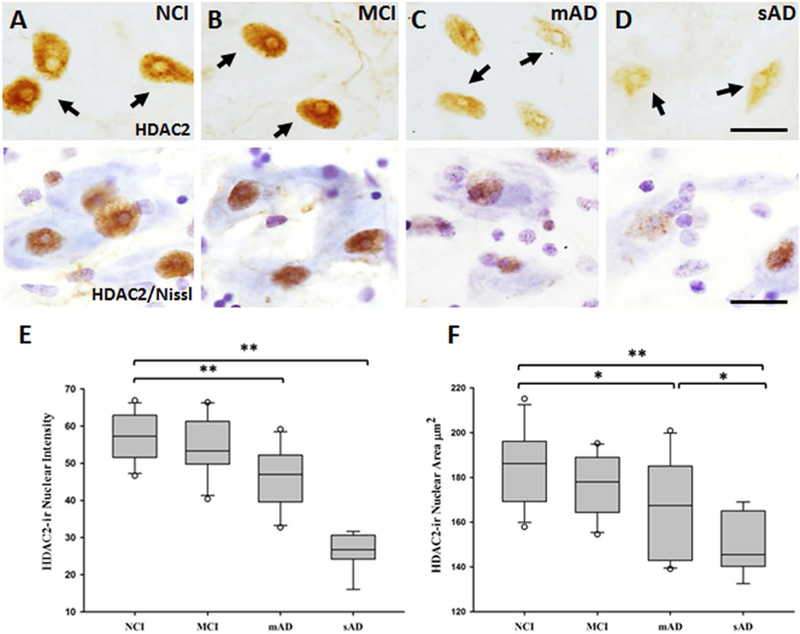

HDAC2 Immunoreactivity Decreases in the nbM in Mild and Severe AD

Since HDAC2 nuclear levels are reduced in entorhinal and hippocampal neurons in persons with AD,(26, 36) we evaluated alterations in this protein in the nuclei of individual nbM neurons during AD progression (Figure 3). Nuclei positive for HDAC2-ir lost their rounded shape, becoming ovoid, flattened, and displaced to the periphery of the soma in the MCI, mAD, and sAD groups (Figure 3B-D). HDAC2-ir intensity was significantly lower in the sAD group than in the other clinical groups (p < 0.001, Figure 3E), whereas HDAC2-ir intensity was significantly lower in the mAD group than in the NCI and MCI groups (both p < 0.001) (Figure 3E). However, the HDAC2-ir intensity in the NCI and MCI groups was not significantly different (p = 0.54, Figure 3E). Significant group differences were noted for nuclear area: those in the sAD group were significantly smaller (153.32±13.95 μm2) than those in the NCI (184.93±17.55 μm2, p < 0.001), MCI (175.91±13.07 μm2, p < 0.001), and mAD (166.13±22.66 μm2, p = 0.04) groups (Figure 3F). The mAD group also had significantly smaller nuclear area than the NCI group (p = 0.03, Figure 3F). HDAC2-ir glial profiles were observed surrounding cholinergic neurons in the MCI, mAD, and sAD groups, which was confirmed by their smaller HDAC2 nuclear area compared with that of the nbM nuclei positive for HDAC2 (10.71±2.08 μm2).

Figure 3.

(A-D) Photomicrographs of sections stained for HDAC2 and cresyl violet, and (E and F) box plots of HDAC2 intensity and nuclear area in non-cognitively impaired (NCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild/moderate AD (mAD), and severe AD (sAD) groups. Nuclei positive for HDAC2 lost their rounded shape (A) and were displaced to the periphery of the soma in the MCI, mAD, and sAD groups (B, C, and D). (E) HDAC2-ir was significantly decreased in mAD compared to NCI and MCI (p < 0.001), and sAD compared to NCI, MCI, and mAD (p < 0.001). (F) The area of the nuclei positive for HDAC2-ir was significantly decreased in mAD compared to NCI (p = 0.03) and in sAD compared to NCI (p < 0.001), MCI (p < 0.001), and mAD (p = 0.04) groups. Circles in box plots indicate outliers. One asterisk indicates p < 0.05; two asterisks indicate a p < 0.001. Scale bars: 10μm.

Since HDAC2 is involved in the aberrant expression of genes involved in learning and memory, we examined the association between nbM HDAC2 intensity and area with cognitive test performance (Table S2). After correcting for multiple comparisons, we found significant correlations between HDAC2-ir intensity and working memory (r = 0.56, p = 0.003, Figure S1A) and between HDAC2-ir intensity and GCS (r = 0.54, p = 0.004, Figure S1B).

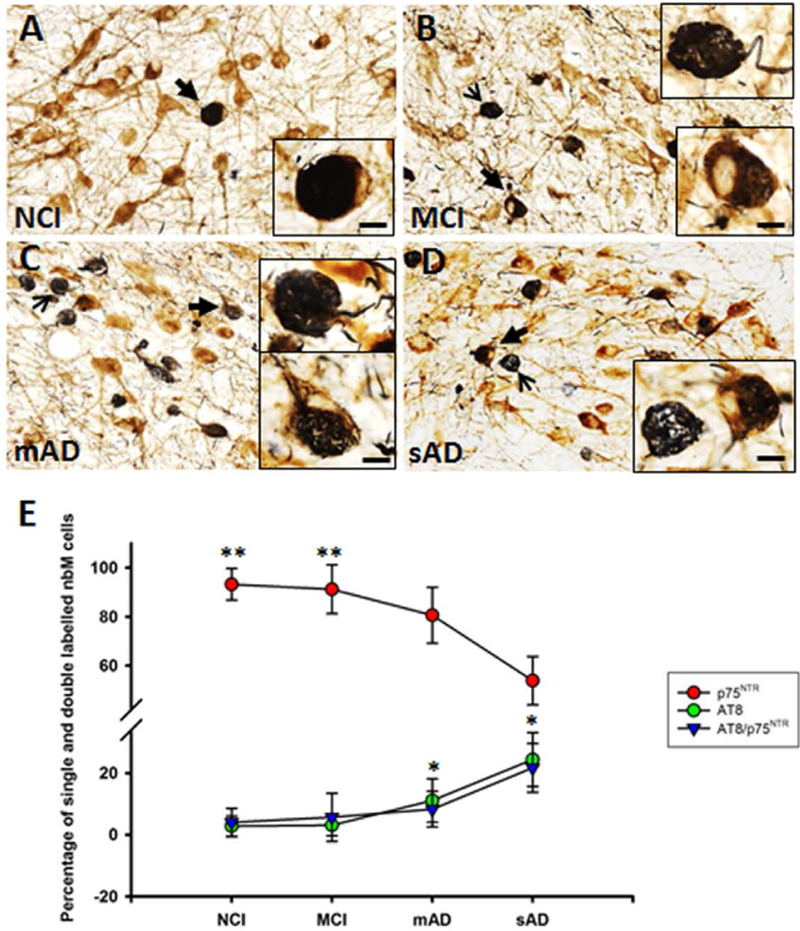

Quantitation of AT8 and p75NTR nbM Neuron Numbers Across Clinical Groups

Neuronal counts were performed to determine the number of single p75NTR versus AT8-positive and p75NTR/AT8-positive nbM neurons within the NCI, MCI, mAD, and sAD groups (Figure 4). Analysis of variance revealed that the percentage of p75NTR-positive neurons was significantly decreased in the mAD and sAD groups compared with the MCI and NCI groups (p < 0.001, Figure 4E), whereas the percentage of AT8-positive neurons increased significantly in the mAD and sAD groups (p < 0.01, Figure 4E) compared with the NCI and MCI groups. However, no significant differences in the percentage of p75NTR/AT8-positive neurons were detected across the groups (p = 0.05, Figure 4E). AT8-positive neuropil threads were also scattered within the basal forebrain. Increased HDAC2 nuclear staining strongly correlated with p75NTR-ir neuronal counts across clinical groups (r = 0.65, p < 0.001, Figure S2A). Counts of AT8-positive perikarya were negatively correlated with HDAC2-ir (r= −0.60, p < 0.001, Figure S2B). AT8/p75NTR-positive neuronal counts were negatively correlated with HDAC2-ir in the nbM (r= −0.59, p < 0.001, Figure S2C). The HDAC2-ir nuclear area was not correlated with AT8 (r= −0.33, p = 0.06) or AT8/p75NTR (r= −0.17, p = 0.32) neuronal counts. The percentage of AT8-positive cells in the nbM was negatively correlated with semantic memory z-scores (r= −0.50, p = 0.008, Table S2, Figure S2D).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of nbM tissue dual immunostained for p75NTR (brown) and AT8 (dark blue/black) in (A) NCI, (B) MCI, (C) mAD, and (D) sAD groups. Note the presence of more p75NTR/AT8-positive (closed arrow) and AT8-positive perikarya (open arrow) in (B) MCI, (C) mAD, and (D) sAD. The percentage of p75NTR-positive neurons (red circles, E) was significantly greater in the NCI and MCI groups than in the mAD and sAD groups (p < 0.001). The percentage of AT8-positive perikarya (green circles, E) increased significantly in the mAD and sAD groups (p < 0.01) compared to the NCI and MCI groups. No significant differences in the percentage of p75NTR/AT8-positive neurons (blue triangle, E) were detected across the groups (p = 0.05). One asterisk indicates p < 0.05; two asterisks indicate a p < 0.001. Scale bars: 50 μm, 10 μm for inset.

HDAC2 Levels Decline in AT8- and TauC3-Positive nbM Neurons

We examined whether HDAC2 nuclear levels related to the development of NFTs within nbM neurons during disease onset. We identified whether changes in HDAC2-ir nuclei were associated with an early phosphorylation-dependent (AT8) or a later stage caspase cleavage-dependent (TauC3) tau isoform. In addition, we also used Thioflavin-S histochemistry to reveal the presence of β-pleated sheet structures in NFTs in cholinergic neurons. Data related to HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity in tangle and non-tangle bearing cholinergic neurons are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 5. HDAC2-ir was significantly decreased in non-NFT–bearing p75NTR-positive neurons across disease progression (p < 0.001, NCI>mAD and sAD; MCI>mAD and sAD; mAD>sAD, Figure 5A, F, K, P, respectively). Moreover, cholinergic neurons, which were AT8-positive (Figure 5B, G, L, Q) or TauC3-positive (Figure 5D, I, N, S), contained even less HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity across clinical groups (p < 0.001, NCI, MCI, and mAD>sAD, Figure 5B-E, G-J, L-O, Q-T, respectively). Similarly, AT8/Thioflavin-S–positive and TauC3/Thioflavin-S–positive cholinergic neurons showed a greater decrease in HDAC2-ir during disease progression (p < 0.001, NCI>sAD, MCI>mAD>sAD; NCI, MCI, and mAD>sAD, respectively, Table 3). A within-group analysis across all clinical groups revealed that HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactive levels were highest in single p75NTR neurons negative for AT8, TauC3, AT8/Thioflavin-S, or TauC3/Thioflavin-S (p < 0.05, Table 3). In the MCI group, HDAC2-ir was greater in cholinergic neurons bearing AT8, TauC3, or AT8/Thioflavin-S than in those bearing TauC3/Thioflavin-S (p < 0.05, Table 3). In the mAD group, HDAC2-ir was greater in AT8-positive, TauC3-positive, or p75NTR-positive neurons than in AT8/Thioflavin-S–positive or TauC3/Thioflavin-S–positive neurons (p < 0.05, Table 3). Cholinergic neurons, which were AT8 positive, had greater HDAC2-ir than neurons bearing AT8/Thioflavin-S or TauC3/Thioflavin-S in the sAD group (p < 0.05, Table 3). Interestingly, nuclear HDAC2-ir in cholinergic nbM neurons labeled for AT8 (p = 0.03) or TauC3/Thioflavin-S (p < 0.05) was significantly lower in females than in males across clinical groups. We previously reported sex differences in trkA mRNA in cholinergic nbM neurons during AD onset.(60) After correcting for multiple comparisons, within-group correlations revealed a significant correlation between HDAC2-ir intensity in AT8 positive cholinergic neurons with working memory scores in MCI (r= −1.0, p<0.0001), and a significant correlation between HDAC2-ir intensity in TauC3 positive cholinergic neurons with visuospatial scores (r= −1.0, p<0.0001) in NCI.

Table 3.

HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity in tangle and non-tangle bearing nbM neurons

| HDAC2-ir | NCI | MCI | mAD | sAD | p-value | Groupwise Comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p75NTR | 139.03±19.97 | 139.46±5.98 | 116.34±7.97 | 89.84±8.92 | <0.001 | NCI>mAD, sAD MCI>mAD, sAD mAD>sAD |

| p75NTR/AT8 | 81.90±13.91 | 85.93±12.05 | 74.64±11.40 | 41.58±10.13 | <0.001 | NCI, MCI, mAD>sAD |

| p75NTR/TauC3 | 93.80±19.14 | 95.02±6.26 | 78.13±14.68 | 36.52±22.26 | <0.001 | NCI, MCI, mAD>sAD |

| p75NTR/AT8/T | 72.15±26.85 | 84.24±12.16 | 52.50±7.59 | 18.91±6.97 | <0.001 | NCI>sAD MCI>mAD, sAD mAD>sAD |

| p75NTR/TauC3/T | 69.90±20.25 | 64.24±13.15 | 46.90±15.70 | 18.20±6.74 | <0.001 | NCI, MCI, mAD>sAD |

|

Within-Group Comparisons |

p75NTR > other groups | p75NTR > other groups; p75 NTR /AT8, p75 NTR /TauC3, p75NTR/AT8/T > p75 NTR /TauC3/T |

p75NTR > other groups; p75 NTR /AT8, p75 NTR /TauC3 > p75NTR/AT8/T, p75NTR/TauC3/T |

p75NTR > other groups p75 NTR /AT8 > p75NTR/AT8/T, p75NTR/TauC3/T |

p < 0.05 | N/A |

Mean ± standard deviation; mAD, mild/moderate Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NCI, no cognitive impairment, sAD, severe Alzheimer’s disease; HDAC2, histone deacetylase 2; p75NTR, pan neurotrophin receptor; T, Thioflavin-S

Figure 5.

(A-T) Fluorescent photomicrographs of p75NTR-ir nbM tissue stained for HDAC2 (cyan), p75NTR (green), AT8 (red), TauC3 (red), and Thioflavin-S (blue). HDAC2-ir decreases in nbM neurons labelled for p75NTR and AT8 from (A) NCI, (F) MCI, to (K) mAD, and (P) sAD (arrow identifies HDAC2-ir nucleus shown in colour inset). Nuclear HDAC2-ir declines in p75NTR-positive neurons labelled for AT8/HDAC2 and HDAC2 alone (arrow identifies same nucleus in black and white images) in NCI (B, C), MCI (G, H), mAD (L, M), and sAD (Q, R) and in nbM neurons triple-labelled for p75NTR/HDAC2/TauC3, and HDAC2 alone in NCI (D, E), MCI (I, J), mAD (N, O), and sAD (S, T). Note displacement and shrinkage of nuclei positive for HDAC2-ir in tangle-bearing cholinergic nbM neurons. Scale bars: 50 μm (A, F, K, P); 10 μm (B-E, G-J, L-O, Q-T).

DISCUSSION

HDACs are dynamic enzymes capable of altering chromatin structure and shifting the epigenetic landscape of the brain. These proteins have multiple cellular functions, including gene transcription important for learning, memory, and neuroinflammation,(26, 28, 61, 62) regulation of genome stability,(63), and cellular toxicity.(64) Increasing evidence from animal studies suggests not only that HDAC2 plays a negative role in hippocampus-dependent cognition in aging but also that protein alterations are present in multiple regions in the AD brain.(34, 36, 39, 42) Our data demonstrate that cholinergic nbM HDAC2 levels are selectively altered in AD, correlating with impaired cognitive performance, and that they are concomitant with NFT formation during disease progression.

Semi-quantitative western blotting revealed that nbM HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC6, and SIRT1 levels were stable, whereas HDAC2 levels were significantly decreased in the sAD group compared with those in the NCI, MCI and mAD groups. Recent investigations suggest that changes in epigenetic markers are not similar across brain regions in AD. A clinical pathological investigation identified significant increases in protein levels of HDAC1 and HDAC3 in MCI and mAD and a decrease in sAD compared with NCI individuals in the frontal cortex.(42) However, HDAC2 levels in the frontal cortex remained stable across clinical groups. HDAC4 was significantly increased in the MCI and mAD groups, but not in the sAD group compared with the NCI group. HDAC6 increased significantly during disease onset, whereas SIRT1 decreased in the MCI, mAD, and sAD groups compared with the NCI group.(42) These latter results suggest that epigenetic changes differ across brain regions during the progression of AD. This regional specificity of HDAC alterations could differentially affect the suggested epigenetic blockade of neuroplasticity-related gene expression by which memory may become permanently impaired in AD. Functionally, HDAC2 is a modulator of chromatin plasticity that forms co-repressor complexes with HDAC1 to alter gene expression. HDAC2 negatively regulates structural and functional synaptic plasticity,(65) altering synaptic transcript levels, immediate early gene expression, and the neuronal survival protein brain-derived neurotrophic factor.(26, 28) In addition, HDAC2 regulates expression of neuroinflammatory genes, and in combination with other transcription factors mediates the cellular response to oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis (61, 62). Thus, HDAC2 is situated in an important position to control expression of multiple proteins important for neuronal survival and programmed cell death in AD. ChAT mRNA and protein levels are epigenetically regulated via hyperacetylation of the core promoter region of the ChAT gene in NG108–15 neuronal cultures.(24) Despite a reduction in HDAC2 nuclear levels in cholinergic nbM neurons in MCI, ChAT protein levels were significantly decreased only in AD compared with the levels in the NCI and MCI suggesting that the downregulation of HDAC2 does not affect ChAT activity in nbM neurons. The maintenance of basal forebrain ChAT levels until sAD supports our previous findings showing a reduction in cortical ChAT activity in sAD compared to that in NCI and MCI subjects.(66) The stability of ChAT activity in both the basal forebrain and frontal cortex lends support to the suggestion that the cholinergic system displays a neuroplasticity response during the early stages of the disease,(66, 67) which is not affected by changes in HDAC2 levels.

This reduction in HDAC2 within cholinergic nbM neurons is similar to the reduction seen in entorhinal cortex layer II neurons and other methylation factors in AD patients.(36) HDAC2 but not HDAC1 or HDAC3 has been found to be increased in CA1 hippocampal and entorhinal cortex nuclei in AD patients compared with non-cognitively impaired aged controls.(26) The discrepancy between these findings may be related to the case selection criteria used in each study. Graff et al.(26) indicated that their cases were chosen based upon a Braak tangle score, whereas the method of selection was not clearly stated by Mastroeni et al.(36) Moreover, there is limited clinical information about the control and AD cases in each study. In addition, in MCI we observed a 95% reduction of HDAC2-ir nuclear diameter compared with that in NCI cases. In mAD and sAD patients, the nuclear diameter was reduced to 89% and 81%, respectively. Our findings are similar to a reported 79% reduction in the nbM nuclear area of AD patients compared with that of controls.(5) With regard to cognition, impaired spatial and associative memory in murine models of neurodegeneration is rescued by short-hairpin knockdown of neuronal HDAC2, which has been suggested to accumulate and block transcription of memory-related genes in the rodent hippocampus.(26, 28) We found that nbM HDAC2 levels were correlated positively with working memory and global cognitive z-scores, which indicate that preserved HDAC2 levels in the basal forebrain, may be indicative of better cognitive function, thereby supporting the use of HDAC drugs for the treatment of AD.

The decline in nbM nuclear HDAC2 levels is exacerbated by the presence of NFT pathology. The current findings agree with previous reports of a reduction in HDAC2 nuclear reactivity in the entorhinal cortex in AD (36) and its association with early NFT formation.(26) We also found that as the number of p75NTR neurons decreased across disease stages, there was a concomitant decrease in HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity. Furthermore, the reduction in HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity inversely correlated with an increase in the number of AT8-positive nbM neurons. Quantitative analysis of the intensity of HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity revealed a significant reduction in non-tangle bearing p75NTR-positive neurons in the mAD and sAD groups compared with those in the NCI and MCI groups. Cholinergic nbM neurons triple-labelled for p75NTR, AT8, or TauC3 displayed an even greater reduction in HDAC2 immunoreactivity in the mAD and sAD groups compared with the non-tangle bearing p75NTR neurons at each disease stage. Within-group analyses indicated that HDAC2 immunoreactivity was highest in non-tangle bearing cholinergic neurons in each clinical group. Interestingly, HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity was further reduced in cholinergic nbM neurons co-labelled for either HDAC2/AT8/Thioflavin-S or HDAC2/TauC3/Thioflavin-S in the MCI and mAD groups. Both of these findings suggest that, although a reduction in HDAC2 occurs before the onset of fibrillar tau pathology; this reduction is exacerbated by the presence of phosphorylated and conformational tau epitopes during the progression of AD. Since cholinergic nbM neurons contain oligomeric tau early in the disease process,(47) the role that oligomeric tau plays in the reduction of HDAC2 before the development of NFTs remains to be determined.

Abnormal phosphorylation and truncation of tau has not been directly linked to HDAC2 dysregulation in patients with AD; however, aberrant kinase and caspase activation has been associated with alterations in HDAC2 expression.(26) In this regard, proline-directed serine/threonine tau kinases, which include cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5)(68) affect tau phosphorylation at Ser202/Thr205 (AT8) and Ser396/Ser404 (PHF-1) sites.(69) Cdk5 also functions as a glucocorticoid receptor kinase, and when bound to the glucocorticoid responsive element within the proximal HDAC2 promoter region, it stimulates HDAC2 expression.(26, 39) Thus Cdk5 may be involved in both tau hyperphosphorylation and HDAC2 transcript regulation via glucocorticoid receptor kinase activity in AD pathogenesis. This interaction may underlie the reduction in HDAC2 reactivity observed in AT8-bearing neurons. However, further examination of the relationship among Cdk5, AT8, and HDAC2 in AD is required.

In each clinical group, HDAC2 nuclear immunoreactivity was the lowest in cholinergic TauC3/Thioflavin-S–positive neurons. TauC3 is a caspase-dependent cleavage epitope associated with apoptotic events and the phenotypic loss of p75NTR in nbM neurons.(21) Epigenetic shifts are thought to orchestrate entry or re-entry into the cell cycle, which would lead to apoptosis in post-mitotic neurons, including in those in AD patients.(70) The role of HDAC2 in apoptotic signalling in cancer is well established. Downregulation of HDAC2 expression inhibits cell proliferation, arrests the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase, and induces cell apoptosis in cell culture models of cancer.(71) Activation of caspase 3 and caspase 7 is significantly increased in vivo upon depletion of HDAC2 (72); silencing HDAC2 is sufficient to decrease NF-κB activity induced by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and to sensitize cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis.(73) Thus, either HDAC2 changes in combination with the loss of DNA methylation or other factors may explain the reported neuronal cell cycle re-entry, apoptosis, or caspase activation in AD.(74)

The current findings indicate that nuclear HDAC2 levels are initially altered in cholinergic nbM neurons in MCI, which suggests that HDAC2 may be used as a preclinical AD biomarker. Neuroepigenetic imaging has recently become available with the advent of HDAC positron emission tomography tracers such as [11C] Martinostat, which detects class I and II HDACs.(75–78) These imaging tools may be used to identify regional HDAC changes in the human brain in light of the apparent complex multiregional response of epigenetic dysregulation observed in the entorhinal cortex,(26, 36) hippocampus,(26) frontal cortex,(42) and basal forebrain (current study). Mapping epigenetic alterations in different brain regions and uncovering the molecular and cellular mechanisms related to disease pathogenesis may provide the basis for novel therapeutic platforms for the treatment of dementia.

Supplementary Material

Figure S2. (A-D) Scatterplots showing correlations between HDAC2 nuclear intensity and percentages of single-labelled and dual-labelled p75NTR/AT8 perikarya and cognitive measures.HDAC2-ir was positively correlated with the percentage of single-labelled p75NTR-ir neurons (r=0.65, p < 0.001, A) and was negatively correlated with the percentage of single-labelled AT8-ir (r= −0.60, p < 0.001, B) and double-labelled p75NTR/AT8-ir perikarya (r= −0.59, p < 0.001, C). The percentage of AT8-ir perikarya was negatively correlated with the semantic memory z-score (r= −0.50, p = 0.008, D). NCI, circles; MCI squares; mAD, triangles; sAD, diamonds.

Figure S1. (A, B) Scatter plots depicting correlations between HDAC2-ir intensity and cognitive test scores. (A) HDAC2 nuclear intensity correlated positively with working memory z-scores (r=0.56, p = 0.003) and (B) Global cognitive scores (r=0.54, p < 0.004) across disease progression. Cognitive data were not available for sAD cases. NCI, circles; MCI, squares; mAD, triangles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We are indebted to the nuns, priests, and lay brothers who participated in the Rush Religious Orders Study and to the members of the Rush ADC. The authors thank the staff of Neuroscience Publications at Barrow Neurological Institute for assistance with manuscript preparation.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This study was supported by grants P01AG014449, P30AG019610, P30AG010161, RO1AG043375 and RO1AG042146 from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, Barrow Neurological Institute, and Barrow Beyond.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1-Ch6). Neuroscience. 1983;10(4):1185–201. Epub 1983/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Clark AW, Coyle JT, DeLong MR. Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Annals of neurology. 1981;10(2):122–6. Epub 1981/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etienne P, Robitaille Y, Wood P, Gauthier S, Nair NP, Quirion R. Nucleus basalis neuronal loss, neuritic plaques and choline acetyltransferase activity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1986;19(4):1279–91. Epub 1986/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doucette R, Fisman M, Hachinski VC, Mersky H. Cell loss from the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 1986;13:435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinne JO PL, Rinne UK. Neuronal size and density in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1987;79:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mufson EJ BM, Kordower JH. Loss of nerve growth factor receptor-containing neurons in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative analysis across subregions of the basal forebrain. Experimental Neurology. 1989;105:221–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iraizoz I dLS, Gonzalo LM. Cell loss and nuclear hypertrophy in topographical subdivisions of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1991;41:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iraizoz I, Guijarro JL, Gonzalo LM, de Lacalle S. Neuropathological changes in the nucleus basalis correlate with clinical measures of dementia. Acta neuropathologica. 1999;98(2):186–96. Epub 1999/08/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rye DB, Wainer BH, Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Saper CB. Cortical projections arising from the basal forebrain: a study of cholinergic and noncholinergic components employing combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase. Neuroscience. 1984;13(3):627–43. Epub 1984/11/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mufson EJ, He B, Nadeem M, Perez SE, Counts SE, Leurgans S, et al. Hippocampal proNGF signaling pathways and beta-amyloid levels in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2012;71(11):1018–29. Epub 2012/10/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry EK, Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Bergmann K, Gibson PH, Perry RH. Correlation of cholinergic abnormalities with senile plaques and mental test scores in senile dementia. British medical journal. 1978;2(6150):1457–9. Epub 1978/11/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcock GK, Esiri MM, Bowen DM, Smith CC. Alzheimer’s disease. Correlation of cortical choline acetyltransferase activity with the severity of dementia and histological abnormalities. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1982;57(2–3):407–17. Epub 1982/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeKosky ST, Harbaugh RE, Schmitt FA, Bakay RA, Chui HC, Knopman DS, et al. Cortical biopsy in Alzheimer’s disease: diagnostic accuracy and neurochemical, neuropathological, and cognitive correlations. Annals of neurology. 1992;32:625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mufson EJ, Ma SY, Cochran EJ, Bennett DA, Beckett LA, Jaffar S, et al. Loss of nucleus basalis neurons containing trkA immunoreactivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;427:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mufson EJ, Ma SY, Dills J, Cochran EJ, Leurgans S, Wuu J, et al. Loss of basal forebrain P75(NTR) immunoreactivity in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2002;443:136–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuello AC, Bruno MA, Bell KF. NGF-cholinergic dependency in brain aging, MCI and Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer research. 2007;4(4):351–8. Epub 2007/10/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iulita MF, Cuello AC. The NGF Metabolic Pathway in the CNS and its Dysregulation in Down Syndrome and Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Alzheimer research. 2016;13(1):53–67. Epub 2015/09/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng S, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, Fahnestock M. Increased proNGF levels in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2004;63(6):641–9. Epub 2004/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasool CG SC, Selkoe DJ. Neurofibrillary degeneration of cholinergic and noncholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology. 1986;20:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sassin I SC, Thal DR, Rub U, Arai K, Braak E, Braak H. Evolution of Alzheimer’s disease-related cytoskeletal changes in the basal nucleus of Meynert. Acta neuropathologica. 2000;100:259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vana LC KN, Ugwu IC, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, Binder LI. Progression of tau pathology in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in MCI and AD. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2533–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesulam M, Shaw P, Mash D, Weintraub S. Cholinergic nucleus basalis tauopathy emerges early in the aging-MCI-AD continuum. Annals of neurology. 2004;55(6):815–28. Epub 2004/06/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aizawa S, Yamamuro Y. Involvement of histone acetylation in the regulation of choline acetyltransferase gene in NG108–15 neuronal cells. Neurochemistry international. 2010;56(4):627–33. Epub 2010/01/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aizawa S TK, Yamamuro Y. Histone deacetylase 9 as a negative regulator for choline acetyltransferase gene in NG108–15 neuronal cells. Neuroscience. 2012;205:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.RA B Choline and the Brain: An Epigenetic Perspective In: Essa M AM, Guillemin G, editor. The Benefits of Natural Products for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Springer, Cham; 2016. p. 381–99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graff J, Rei D, Guan JS, Wang WY, Seo J, Hennig KM, et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature. 2012;483(7388):222–6. Epub 2012/03/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook C, Gendron TF, Scheffel K, Carlomagno Y, Dunmore J, DeTure M, et al. Loss of HDAC6, a novel CHIP substrate, alleviates abnormal tau accumulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(13):2936–45. Epub 2012/04/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan JS, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg JH, Joseph N, Gao J, et al. HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2009;459(7243):55–60. Epub 2009/05/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu K, Dai XL, Huang HC, Jiang ZF. Targeting HDACs: a promising therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2011;2011:143269 Epub 2011/09/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding H, Dolan PJ, Johnson GV. Histone deacetylase 6 interacts with the microtubule-associated protein tau. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008;106(5):2119–30. Epub 2008/07/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen X, Chen J, Li J, Kofler J, Herrup K. Neurons in Vulnerable Regions of the Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Display Reduced ATM Signaling. eNeuro. 2016;3(1). Epub 2016/03/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey UB, Nie Z, Batlevi Y, Mccray BA, Ritson GP, Nedelsky NB, et al. HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS. Nature. 2007;447:859–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen S, Owens GC, Makarenkova H, Edelman DB. HDAC6 regulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. PloS one. 2010;5(5):e10848 Epub 2010/06/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Julien C, Tremblay C, Emond V, Lebbadi M, Salem N Jr., Bennett DA, et al. Sirtuin 1 reduction parallels the accumulation of tau in Alzheimer disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2009;68(1):48–58. Epub 2008/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalla R, Donmez G. The role of sirtuins in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2013;5:16 Epub 2013/04/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mastroeni D, Grover A, Delvaux E, Whiteside C, Coleman PD, Rogers J. Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer’s disease: decrements in DNA methylation. Neurobiology of aging. 2010;31(12):2025–37. Epub 2009/01/02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz TW, Nathan Spreng R. Basal forebrain degeneration precedes and predicts the cortical spread of Alzheimer’s pathology. Nature communications. 2016;7:13249 Epub 2016/11/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teipel SJ FM, Heinsen H, Bokde ALW, Schoenberg SO, Stockel S, Dietrich O, et al. Measurement of basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. Brain. 2005;128:2626–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graff J, Tsai LH. Histone acetylation: molecular mnemonics on the chromatin. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(2):97–111. Epub 2013/01/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150(1):12–27. Epub 2012/07/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volmar CH WC. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) and brain function. Neuroepigenetics. 2015;1:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahady L NM, Malek-Ahmadi M, Chen K, Perez SE, Mufson EJ. Frontal Cortex Epigenetic Dysregulation During the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018;62:115–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Garcia-Sierra F, Reynolds MR, Horowitz PM, Fu Y, Wang T, et al. Tau truncation during neurofibrillary tangle evolution in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2005;26(7):1015–22. Epub 2005/03/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Sierra F, Ghoshal N, Quinn B, Berry RW, Binder LI. Conformational changes and truncation of tau protein during tangle evolution in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2003;5(2):65–77. Epub 2003/04/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Binder LI, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Garcia-Sierra F, Berry RW. Tau, tangles, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2005;1739(2–3):216–23. Epub 2004/12/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Combs B HC, Kanaan NM. Pathological conformations involving the amino terminus of tau occur early in Alzheimer’s disease and are differentially detected by monoclonal antibodies. Neurobiology of disease. 2016;94:18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tiernan CT, Mufson EJ, Kanaan NM, Counts SE. Tau Oligomer Pathology in Nucleus Basalis Neurons During the Progression of Alzheimer Disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2018;77(3):246–59. Epub 2018/01/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett DA SJ, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Mild cognitive impairment is related to Alzheimer disease pathology and cerebral infarctions. Neurology. 2005;64:834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mufson EJ, Chen EY, Cochran EJ, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Kordower JH. Entorhinal cortex beta-amyloid load in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Exp Neurol. 1999;158(2):469–90. Epub 1999/07/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59(2):198–205. Epub 2002/07/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez SE, Getova DP, He B, Counts SE, Geula C, Desire L, et al. Rac1b increases with progressive tau pathology within cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:526–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bach J, Evans DA, et al. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging. 2002;17(2):179–93. Epub 2002/06/14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersen R Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica. 1991;82(4):239–59. Epub 1991/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newell KL, Hyman BT, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET. Application of the National Institute on Aging (NIA)-Reagan Institute criteria for the neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 1999;58(11):1147–55. Epub 1999/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mirra SS. The CERAD neuropathology protocol and consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a commentary. Neurobiology of aging. 1997;18(4 Suppl): S91–4. Epub 1997/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2007;6(8):734–46. Epub 2007/07/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Counts SE NM, Wuu J, Ginsberg SD, Saragovi HU, Mufson EJ. Reduction of cortical TrkA but not p75(NTR) protein in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of neurology. 2004;56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glickman ME RS, Schultz MR. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:850–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Counts SE, Che S, Ginsberg SD, Mufson EJ. Gender differences in neurotrophin and glutamate receptor expression in cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2011;42(2):111–7. Epub 2011/03/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng S, Zhao S, Yan F, Cheng J, Huang L, Chen H, et al. HDAC2 selectively regulates FOXO3a-mediated gene transcription during oxidative stress-induced neuronal cell death. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35(3):1250–9. Epub 2015/01/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsing CH, Hung SK, Chen YC, Wei TS, Sun DP, Wang JJ, et al. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Trichostatin A Ameliorated Endotoxin-Induced Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Dysfunction. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015:163140 Epub 2015/08/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan L, Penney J, Tsai LH. Chromatin regulation of DNA damage repair and genome integrity in the central nervous system. Journal of molecular biology. 2014;426(20):3376–88. Epub 2014/08/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coppede F The potential of epigenetic therapies in neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in genetics. 2014;5:220 Epub 2014/07/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akhtar MW RJ, Nelson ED, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 form a developmental switch that controls excitatory synapse maturation and function. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:8288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Styren SD, Beckett L, Wisniewski S, Bennett DA, et al. Upregulation of choline acetyltransferase activity in hippocampus and frontal cortex of elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Annals of neurology. 2002;51(2):145–55. Epub 2002/02/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mufson EJ, Malek-Ahmadi M, Snyder N, Ausdemore J, Chen K, Perez SE. Braak stage and trajectory of cognitive decline in noncognitively impaired elders. Neurobiology of aging. 2016;43:101–10. Epub 2016/06/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson GV, Stoothoff WH. Tau phosphorylation in neuronal cell function and dysfunction. Journal of cell science. 2004;117(Pt 24):5721–9. Epub 2004/11/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Plattner F, Angelo M, Giese KP. The roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 in tau hyperphosphorylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(35):25457–65. Epub 2006/06/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golubnitschaja O Cell cycle checkpoints: the role and evaluation for early diagnosis of senescence, cardiovascular, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. Amino acids. 2007;32(3):359–71. Epub 2006/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li S, Wang F, Qu Y, Chen X, Gao M, Yang J, et al. HDAC2 regulates cell proliferation, cell cycle progression and cell apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma EC9706 cells. Oncology letters. 2017;13(1):403–9. Epub 2017/01/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schuler S, Fritsche P, Diersch S, Arlt A, Schmid RM, Saur D, et al. HDAC2 attenuates TRAIL-induced apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells. Molecular cancer. 2010;9:80 Epub 2010/04/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaler P ST, Shirasawa S, Augenlicht L, Klampfer L. HDAC2 deficiency sensitizes colon cancer cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis through inhibition of NF-κB activity. Experimental Cell Research. 2008;314:1507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Y ME, Herrup K. Neuronal Cell Death Is Preceded by Cell Cycle Events at All Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2557–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schroeder FA, Wang C, Van de Bittner GC, Neelamegam R, Takakura WR, Karunakaran A, et al. PET imaging demonstrates histone deacetylase target engagement and clarifies brain penetrance of known and novel small molecule inhibitors in rat. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(10):1055–62. Epub 2014/09/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J, Yu JT, Tan MS, Jiang T, Tan L. Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Ageing research reviews. 2013;12(4):1024–41. Epub 2013/05/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang C, Schroeder FA, Wey HY, Borra R, Wagner FF, Reis S, et al. In vivo imaging of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the central nervous system and major peripheral organs. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2014;57(19):7999–8009. Epub 2014/09/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wey HY, Gilbert TM, Zurcher NR, She A, Bhanot A, Tailon BD, et al. Insights into neuroepigenetics through human histone deacetylase PET imaging. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S2. (A-D) Scatterplots showing correlations between HDAC2 nuclear intensity and percentages of single-labelled and dual-labelled p75NTR/AT8 perikarya and cognitive measures.HDAC2-ir was positively correlated with the percentage of single-labelled p75NTR-ir neurons (r=0.65, p < 0.001, A) and was negatively correlated with the percentage of single-labelled AT8-ir (r= −0.60, p < 0.001, B) and double-labelled p75NTR/AT8-ir perikarya (r= −0.59, p < 0.001, C). The percentage of AT8-ir perikarya was negatively correlated with the semantic memory z-score (r= −0.50, p = 0.008, D). NCI, circles; MCI squares; mAD, triangles; sAD, diamonds.

Figure S1. (A, B) Scatter plots depicting correlations between HDAC2-ir intensity and cognitive test scores. (A) HDAC2 nuclear intensity correlated positively with working memory z-scores (r=0.56, p = 0.003) and (B) Global cognitive scores (r=0.54, p < 0.004) across disease progression. Cognitive data were not available for sAD cases. NCI, circles; MCI, squares; mAD, triangles.