Abstract

Canonical or classical transient receptor potential 4 and 5 proteins (TRPC4 and TRPC5) assemble as homomers or heteromerize with TRPC1 protein to form functional nonselective cationic channels with high calcium permeability. These channel complexes, TRPC1/4/5, are widely expressed in nervous and cardiovascular systems, also in other human tissues and cell types. It is debatable that TRPC1 protein is able to form a functional ion channel on its own. A recent explosion of molecular information about TRPC1/4/5 has emerged including knowledge of their distribution, function, and regulation suggesting these three members of the TRPC subfamily of TRP channels play crucial roles in human physiology and pathology. Therefore, these ion channels represent potential drug targets for cancer, epilepsy, anxiety, pain, and cardiac remodelling. In recent years, a number of highly selective small‐molecule modulators of TRPC1/4/5 channels have been identified as being potent with improved pharmacological properties. This review will focus on recent remarkable small‐molecule agonists: (−)‐englerin A and tonantzitlolone and antagonists: Pico145 and HC7090, of TPRC1/4/5 channels. In addition, this work highlights other recently identified modulators of these channels such as the benzothiadiazine derivative, riluzole, ML204, clemizole, and AC1903. Together, these treasure troves of agonists and antagonists of TRPC1/4/5 channels provide valuable hints to comprehend the functional importance of these ion channels in native cells and in vivo animal models. Importantly, human diseases and disorders mediated by these proteins can be studied using these compounds to perhaps initiate drug discovery efforts to develop novel therapeutic agents.

Abbreviations

- A54

analogue 54

- A498 cells

human renal cell carcinoma cell line 498

- BTD

benzothiadiazine derivative

- EA

(−)‐englerin A

- EB

(−)‐englerin B

- SW982 cells

human synovial sarcoma cells

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- TRPC

transient receptor potential canonical

- TZL

tonantzitlolone

1. INTRODUCTION

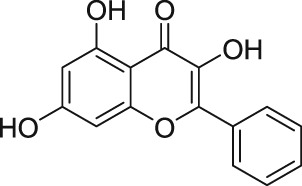

Ion channels are pore‐forming proteins, which are involved and play critical roles in very important physiological and pathological processes, such as neuronal signalling and cardiac excitability. Therefore, ion channels serve as therapeutic drug targets (Bagal et al., 2013; Rubaiy, 2017). The human transient receptor potential (TRP) proteins comprise a family of 27 cation channels that are predominately calcium (Ca2+)‐permeable (Nilius & Szallasi, 2014). The TRP proteins were first described in Drosophila melanogaster, commonly known as the fruit fly (Minke, Wu, & Pak, 1975). The TRP channels are divided into six subfamily according to their amino acid sequence, TRP canonical or classical (TRPC), TRP vanilloid (TRPV), TRP melastatin (TRPM), TRP ankyrin (TRPA), TRP polycystin (TRPP), and TRP mucolipin. The TRP channel superfamily consists of six transmembrane domains, termed S1–S6, with cytoplasmic N‐ and C‐terminal regions and the pore region formed by S5 and S6 segments, Figure 1, (Beech, 2013; Clapham, 2003). They are ubiquitously expressed in different tissues and cell types in the human body and are a key player in the regulation of intracellular calcium by depolarizing the membrane potential or delivering the Ca2+ influx pathway (Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017).

Figure 1.

Proposed membrane topology structure of the TRPC1/4/5 channels. (a) The suggested structure topology of monomeric TRPC1/4/5 channels consist of six membrane‐spanning domains, S1–S6, interconnected by short loops and the putative pore region loop between transmembrane segments S5 and S6 enabling entry of cations primarily Ca2+. The amino (N) and carboxyl (C) termini are located intracellularly and mediate downstream signalling. (b) Schematic structure of functional tetrameric assembly for a monomeric or a heteromeric complex of TRPC1/4/5. The recent novel and most potent agonists and antagonists are shown in (b)

The first subfamily of TRP gene cloned in mammals was TRPC channels (Wes et al., 1995). So far, seven members of the TRPC subfamily have been identified (TRPC1–TRPC7). In humans, apes, and old‐world monkeys, the TRPC2 is a pseudogene, and moreover, the TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC5 are believed to cluster together (TRPC1/4/5) to form homomeric or heteromeric channels. It is worth mentioning that the function of TRPC1 is a matter of debate, as when expressed alone, it does not form a functional ion channel (Beech, 2013; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). For the past two decades, a plethora of studies have reported that the TRPC channels play vital roles in many physiological and pathological mechanisms (Beech, 2013; Nilius & Szallasi, 2014; Rubaiy, 2017).

1.1. Calcium signalling and regulation of cell function

The transport of ions across the cell membrane plays a vital role in normal cell functions (Clapham, 2007; Rubaiy, 2017). The Ca2+ ion is a universal second messenger that regulates a wide variety of very important functions in almost all cell types (Clapham, 2007). These cellular functions include muscle contraction, neuronal transmission, cell migration, cell growth, gene transcription, and cell death. Therefore, dysregulation of Ca2+ signals is linked to major diseases in humans including cardiovascular and neurological disorders, and cancer (Clapham, 2007).

1.2. Activation and regulation of TRPC1/4/5 channels

The main mechanisms of activation for TRPC1/4/5 channels are GPCRs and receptor TKs and their downstream components. The receptor‐mediated activation of TRPC1/4/5 mechanism is well established (Beech, 2013; Clapham, 2003; Freichel, Tsvilovskyy, & Camacho‐Londono, 2014; Zholos, 2014) In response to agonist binding, such as histamine, angiotensin II, and endothelin‐1, to the GPCRs, the receptor‐operated channels, which are membrane‐spanning nonselective cation channels, mediate Ca2+ entry into the cells (Beech, 2013; Clapham, 2003). The activation of GPCRs by agonists binding and, subsequently, activation of PLC cleave the phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate (PIP2) into two products: DAG and inositol 1,4,5‐triphosphate (Beech, 2013; Clapham, 2003; Kim et al., 2012).

In 2012, the lipid‐sensing properties of TRPC channels were reviewed in depth by Beech (2012). In addition to PIP2, several other lipid factors, such as oxidized phospholipids, lysophosphatidic acid, some steroidal derivatives, and PAF, also regulate the activity of the TRPC1/4/5 channels (Beech, 2012). The depletion of PIP2 which occurs after GPCR‐mediated activation of the Gq‐PLCβ and/or receptor TK‐mediated activation of the PLCγ signaling, stimulates the TRPC1/4/5 channels (Beech, 2013; Clapham, 2003; Kim et al., 2012; Storch et al., 2017). Notably, in contrast to other TRPC channel members (TRPC2, 3, 6, and 7), TRPC1/4/5 are not activated by DAG. However, recently, Storch et al. (2017) reported that the dissociation of scaffolding proteins Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 1 and 2 from TRPC4 and TRPC5 is critical for the activation of DAG‐mediated channels. Therefore, DAG sensitivity is a characteristic hallmark of the TRPC family of channels.

Many groups have reported that the TRPC1/4/5 channel activity clearly depends on calmodulin (CaM) and intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i; Freichel et al., 2014; Zholos, 2014). Okada et al. (1998) showed that at least 10 nM [Ca2+]i is required for homomeric TRPC5 channel activation. Two CaM‐binding domains for homomeric TRPC4 and three for TRPC5 (closely related to TRPC4) have been identified (Ordaz et al., 2005; Zhu, 2005). However, the regulation of TRPC4 by Ca2+/CaM is probably more complex and different from TRPC5 channels (Zholos, 2014).

In addition, the mammalian TRPC subfamily is able to interact with many other proteins that are associated with vesicle trafficking, plasma membrane expression, cytoskeletal linking, protein scaffolding, and regulating Ca2+ signalling (Freichel et al., 2014; Zholos, 2014). Bezzerides, Ramsey, Kotecha, Greka, and Clapham (2004) showed the cellular trafficking of TRPC5 channels is controlled by growth factor stimulation. In more detail, the growth factor stimulation evoked the rapid incorporation of expressed homomeric TRPC5, but not TRPC1, into the plasma membrane of the HEK 293 cells (Bezzerides et al., 2004). The rapid translocation was regulated by phosphatidylinositide 3‐kinase, Rac1, and phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate 5‐kinase (Bezzerides et al., 2004).

1.3. TRPC1/4/5 channels in human health and disease

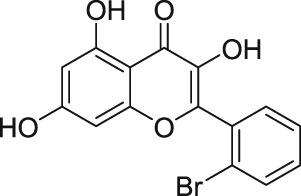

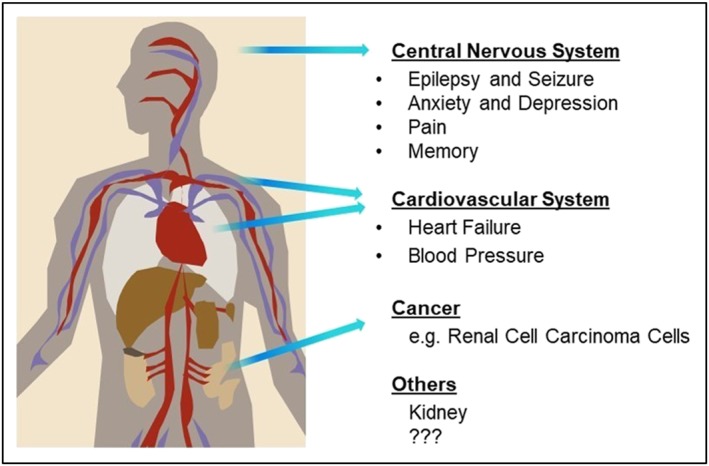

The TRPC4 and TRPC5 proteins assemble as homomers or heteromerize with TRPC1 to form functional Ca2+‐permeable nonselective cationic channels in numerous mammalian cell types and they are involved in many physiological and pathological processes (Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). TRPC1/4/5 have been suggested to play multiple roles in various conditions, including epilepsy, fear, pain, severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, vascular inflammation in arthritis, and cardiac remodelling (Figure 2). However, the lack of modulators to study the functional roles of these channels have limited progress into their exact role (Alawi et al., 2017; Camacho Londono et al., 2015; Francis, Xu, Zhou, & Stevens, 2016; Minard et al., 2018; Phelan et al., 2013; Riccio et al., 2009; Riccio et al., 2014; Westlund et al., 2014; Zheng & Phelan, 2014). The identification of high‐quality, reliable, selective, and subtype‐specific TRPC1/4/5 pharmacological tools and modulators would perhaps enable a better understanding of TRPC1/4/5 channels in human health and disease.

Figure 2.

The putative roles of TRPC1/4/5 channels in human health and diseases

1.4. Cancer

The transport of ions across the cell membrane plays a vital role in normal cell functions. In particular, the [Ca2+]i ion acting as a second messenger plays a critical role in many physiological processes and is involved in the regulation of a variety of cell functions, such as gene transcription, cell proliferation, migration, and death. At present, it is well documented that [Ca2+]i homeostasis is altered in cancer cells and that a dysregulation of Ca2+ signalling plays a role in tumour initiation, progression, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Therefore, the targeting Ca2+ signalling and nonselective calcium permeable TRP channels have become an emerging research field for cancer therapy (Gaunt, Vasudev, & Beech, 2016; Liberati, Morelli, Nabissi, Santoni, & Santoni, 2013; Rubaiy, 2017). However, in this review, we will focus on the involvement of TRPC1/4/5 channels in cancer and their potential therapeutic target by using small molecules, such as (−)‐englerin A (EA) and tonantzitlolone (TZL; Gaunt et al., 2016; Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018; Sourbier et al., 2015).

Beutler and his colleagues (Ratnayake, Covell, Ransom, Gustafson, & Beutler, 2009) revealed that EA has a strong selectivity for the renal cancer cell line panel with five of eight renal lines having GI50 values (concentration that causes 50% reduction in proliferation of cancer cells) of under 20 nM; these include human renal cell carcinoma (RCC) cell line 498 (A498 cells) and 786‐0 cell lines of <10 nM. EA is a natural product extracted from the Phyllanthus engleri tree and structurally unique. Since current therapies for renal cancer are ineffective and expensive, many groups are trying to develop an EA analogue that is potent, metabolically stable, and non‐toxic. Recently, Akbulut et al. (2015) reported that EA is a selective and potent activator of TRPC1/4/5 channels that particularly targets the heteromeric endogenous TRPC1/TRPC4 in A498 cells causing cytotoxicity. Interestingly, after the identification of the EA target by Akbulut et al., Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research coincidentally confirmed that activation of TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels by EA inhibits tumour cell line proliferation, suggesting EA targets these proteins. Novartis' extensive work revealed that EA is not just able to inhibit the growth of RCCs but also that of over 500 other cancer cell lines (Carson et al., 2015).

A novel approach using small molecules, such as EA to target TRPC1/4/5 channels as in cancer therapy, was recently comprehensively reviewed by Gaunt et al. (2016). Activation of TRPC1/TRPC4 channels in certain cancer cell lines leads to rapid cell death. This suggests a bell‐shaped relationship between intracellular Ca2+ concentration and cell function. While modest increases in Ca2+ are beneficial for cells, promoting proliferation and migration, a surge of Ca2, for example, 1 μM, is toxic for cells, promoting apoptosis, and necrosis (Gaunt et al., 2016). With a highly potent and efficacious activator (EA, TZL, or their analogues), it is possible to achieve rapid cytotoxicity, and perhaps such activators might lead to novel anticancer drugs (Akbulut et al., 2015; Carson et al., 2015; Cheung et al., 2018; Gaunt et al., 2016; Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018; Sourbier et al., 2015). Notably, EA's mechanism of action (cytotoxicity) is mediated by Na+ influx and not Ca2+ as previously thought. In more detail, EA cytotoxicity in A498 cells is achieved by inducing sustained Na+ entry through activation of TRPC1/TRPC4 channel complexes. This effect can be potentiated by inhibiting Na+/K+‐ATPase (Ludlow et al., 2017). Just recently, Cheung et al. (2018) have revealed another important finding in the field of EA and cancer; they showed that TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels mediate an adverse reaction to the cancer cell cytotoxic agent EA.

Veliceasa et al. (2007) studied the role of thrombospondin‐1, an angiogenesis inhibitor in RCC, in normal tissue and its secretion by the normal renal epithelium (human kidney cells). The group disclosed that RCC cells failed to take up Ca2+ in response to growth factor. Possible factors include low expression levels of the two Ca2+ exchange proteins, calbindin, and TRPC4. In addition, they stated that TRPC4 is a key regulator of Ca2+ intake in renal tissue, suggesting that a reduction in TRPC4 might be an adaption of RCC cells during the lack of a calbindin protective function. Their results showed a significant decrease in TRPC4 Ca2+ channel expression in RCC cells and that TRPC4 silencing in human normal kidney cells led to thrombospondin‐1 retention and impaired secretion (Veliceasa et al., 2007).

A separate study by Wei et al. (2017) revealed the roles of TRPC4‐containing channels in medulloblastoma cells. They suggested that TRPC4 and TRPC5 activation might enhance the motility of certain types of medulloblastoma, the most common paediatric brain tumour. An increase in motility is necessary for transformed cells to invade and induce metastasis. In this study, UW228‐1 cells, derived from a nonmetastatic tumour of the vermis, were blocked by EA suggesting that the cells depend on both TRPC4 and TRPC5 activation. They believe that TRPC4‐ and TRPC5‐dependent depolarization of the cell membrane may play a role in TRPC4 and TRPC5 activation, which inhibits UW228‐1 cell migration (Wei et al., 2017).

Moreover, Batova et al. (2017) revealed in a recent study that EA significantly alters lipid metabolism in clear cell renal carcinoma (cc‐RCC) cell lines and produced substantial ceramide levels causing high toxicity to these cells. They reported that the cc‐RCC is very sensitive to alterations in lipid metabolism and endoplasmic reticulum stress suggesting that these sensitivities should be targeted for the treatment of lipid storing cancers including cc‐RCC. Furthermore, the study revealed that EA triggered an inflammatory response possibly due to endoplasmic reticulum stress, which can mediate antitumour immunity (Batova et al., 2017).

Recently, Muraki et al. (2017) reported that heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels are a target for EA in human synovial sarcoma cells (SW982 cells). In more detail, the study revealed that the EA‐induced cation channel current in SW982 cells was characteristic of that of the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels. In brief, electrophysiological patch clamp recording of SW982 cells depleted of TRPC1 revealed a typical homomeric TRPC4 EA‐induced current–voltage relationship, and importantly, deletion of TRPC1 or TRPC4 suppressed the EA‐induced cytotoxicity. Also, EA‐induced cytotoxicity in synovial sarcoma cells has been shown to be mediated through Na+ entry of heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels (Muraki et al., 2017). This work demonstrated how small‐molecule activators, such as EA, or inhibitors, such as Pico145, of TRPC1/4/5 can be useful as tools to study the physiological and pathological role of TRPC/1/4/5 channels in vitro and in vivo (Minard et al., 2018).

1.5. Cardiovascular

There have been numerous studies that have shown the involvement of TRPC channels within the cardiovascular system (Alawi et al., 2017; Camacho Londono et al., 2015; Francis et al., 2016; Lau et al., 2016; Xiao, Liu, Shen, Cao, & Li, 2017). Camacho Londono et al. (2015) reported that TRPC1 and TRPC4 proteins play a pivotal role in a background Ca2+ entry pathway, which fine‐tunes Ca2+ cycling in cardiomyocytes. When this channel activity was blocked through a double knockout of TRPC1/TRPC4, pathological cardiac remodelling in mice was protected without causing any disruption in normal cardiac function. A separate group has also found that inactivation of TRPC4 improves survival in rats with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (Alzoubi et al., 2013). This was ascribed to diminished occlusive remodelling of blood vessels in knockout animals. Also, there have been suggestions that TRPC channels acting as baroreceptors are involved in the regulation of blood pressure (Lau et al., 2016).

1.6. Neurological diseases and disorders

TRPC channels are also involved in a number of neurological diseases and disorders including memory, pain, epilepsy, fear, and anxiety. Recently, a group led by Freichel identified TRPC1/4/5 channels and mixed populations of TRPC1/TRPC4, TRPC1/TRPC5, and TRPC4/TRPC5 channels in hippocampal cells of rats (Broker‐Lai et al., 2017). They found that slices of neurons and hippocampus from TRPC1/4/5 triple knockout mice displayed decreased (action potential‐triggered) postsynaptic responses. This study reported that the TRPC1/4/5 channels are involved in spatial working memory and learning/adaptation (Broker‐Lai et al., 2017). Another study suggested that the TRPC1/4/5 channels are involved in different types of pain (Westlund et al., 2014). Also, different groups showed that TRPC1/4/5 channels are involved in epilepsy (Phelan et al., 2013; Tai, Hines, Choi, & MacVicar, 2011; von Spiczak et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017). The TRPC1/4/5 channels are expressed in the brain, particularly the TRPC5 protein is highly expressed in the regions, linked to fear and anxiety (Riccio et al., 2009; Riccio et al., 2014). Remarkably, Riccio et al. (2009) reported that TPRC5 knockout mice had less fear behaviour compared to wild‐type mice. Interestingly, equal anxiolytic phenotype was reported in TRPC4 knockout mice and in those mice given the selective and potent blocker of TRPC1/4/5 channels, HC‐070 (the in vitro properties of HC‐070 comparable to Pico145), confirming the role of TPRC1/4/5 channels in fear and anxiety (Just et al., 2018). The above studies suggest that the TRPC1/4/5 channels are a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of neurological diseases and disorders.

1.7. Others

TRPC channels have also been found to play roles in other functions, such as in the kidney where kidney filter barrier damage and the resultant albuminuria triggered by LPS has been found to be prevented in TRPC5−/− knockout mice (Schaldecker et al., 2013). The knockout of TRPC5 also led to protection of podocytes from barrier damage caused by protamine‐sulphate. This has also been shown in wild‐type animals that have been administered ML204, which is a homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 inhibitor (Schaldecker et al., 2013). Likewise, another recently identified small‐molecule blocker, AC1903, of the homomeric TRPC5 channels has been found to suppress progressive kidney diseases (Zhou et al., 2017). Another study recently suggested that Ca2+ permeable channels containing TRPC1 block exercise‐induced protection against high‐fat diet‐induced obesity and type II diabetes suggesting that the TRPC1 plays an vital role in the regulation of adiposity (Krout et al., 2017).

1.8. The electrophysiological characteristics of TRPC1/4/5 channels

The homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 and the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 and TRPC1/TRPC5 channels display a distinct complex I–V relationship. It is well established that homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 exhibit a similar I–V relationship (Lee et al., 2003; Minard et al., 2018; Okada et al., 1998; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Schaefer et al., 2000). The homomeric channels have a doubly rectification relationship with a typical seat like inflection in the I–V relationship and fairly large inward currents. In contrast, the heteromeric channels have small inward currents at negative potentials and mainly smooth outward rectification (Clapham, 2003; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017).

In 2000, Schaefer et al. studied the seat like inflection of the I–V relationship of homomeric channels. They reported that the flat segment between +10 and +40 mV of homomeric TRPC5 channels is caused by a blockage of intracellular Mg2+ ([Mg2+]i). This inhibition of the current brings the slope to almost zero and notably, the block is relieved at voltages more than +40 mV (Schaefer et al., 2000). Later, Obukhov and Nowycky (2005) demonstrated that a single cytosolic residue (D633) mediates Mg2+ inhibition and contributes to the control of the inward current amplitude of homomeric TRPC5 channels. The biophysical properties and I–V relationship of heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 channels differ from homomeric TRPC5 channels such that they lack of Mg2+ sensitivity, this can possibly be explained by the structural alteration of the putative D633 ring (Obukhov & Nowycky, 2005). Likewise, the homomeric TRPC4 channels are possibly blocked by [Mg2+]i; however, no studies to date have addressed this experimentally.

Obukhov and Nowycky (2008) also studied the gating properties of homomeric TRPC5 channels. They concluded that the gating can switch reversibly between voltage‐dependent and voltage‐independent states during its activation cycle. However, functionally, the homomeric TRPC5 channels mainly exist in a voltage‐independent state (Obukhov & Nowycky, 2008).

TRPC1 was first reported in 1995 and its mRNA is expressed in five splice variants. However, only α, β, and ε can be translated and form functional proteins (Sakura & Ashcroft, 1997; Wes et al., 1995). Until now, 11 splice variants for TRPC4 and just one splice variant for the TRPC5 gene have been reported (Freichel et al., 2014). The most functionally characterized splice variants of TRPC4 are α and β. In 2002, the functional differences between TRPC4 splice variants were studied in depth (Schaefer et al., 2000). This group reported that the TRPC4α and TRPC4β are abundantly expressed and across various species, the TRPC4β is the functional cation channel (Freichel et al., 2014; Schaefer, Plant, Stresow, Albrecht, & Schultz, 2002).

In contrast to homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5, it is still a matter of debate whether TRPC1 proteins form functionally physiological homomeric channels (Dietrich, Fahlbusch, & Gudermann, 2014; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). However, in 1996, Zitt et al. reported the first functional data for TRPC1 channels. The human cDNA, TRPC1, was identified from a human fetal brain cDNA library and transiently expressed in CHO cells for electrophysiological study (Zitt et al., 1996). In this study, the single‐channel analysis of TRPC1 activated by 10 μM inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate, added to the pipette solution, revealed a conductance of 16 pS (Harteneck, Plant, & Schultz, 2000; Zitt et al., 1996). Notably, the I–V relationship for TRPC1 did not exhibit a typical seat‐like inflection as with homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels.

In 2001, Strübing, Krapivinsky, Krapivinsky, and Clapham, for the first time, showed that TRPC1 and TRPC5 or TRPC1 and TRPC4 isoforms are able to form heteromeric channels in mammalian brain. This study characterized the electrophysiological properties of heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 or TRPC1/TRPC4 channel complexes (Strübing et al., 2001). The group revealed that TRPC1 and TRPC5 proteins can assemble as heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 neuronal channels activated by Gq‐coupled receptors but not by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. The biophysical properties of this channel complex (TRPC1/TRPC5) were notably unlike any reported homomeric TRPC, and the TRPC1/TRPC5 currents displayed significantly altered permeation properties. Moreover, cell‐attached single‐channel recordings of homomeric TRPC5 and heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 channels expressed in the HEK 293 cell line stably expressing the muscarinic M1 receptor (HEK 293‐M1) revealed the heteromeric channels had smaller slope conductance (5 pS) compared with the homomeric channels (38 pS; Strübing et al., 2001). In addition, the I–V relationship of the currents of heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 channels were unequivocally distinct from the inwardly rectifying relationship of homomeric TRPC5 channels (Strübing et al., 2001). Notably, a co‐immunoprecipitation study showed a physical interaction between native TRPC1 and TRPC5 subunits in rat brain microsomes. As TRPC4 and TRPC5 proteins share 65% amino acid sequence identity (highly conserved N‐terminal and transmembrane regions), Strübing et al. (2001) also tested the combination of TRPC1 with TRPC4 and for the first time showed that TRPC4 immunoprecipitated with TRPC1 from rat brain.

The biophysical properties of homomeric TRPC4 channels were studied by Tsvilovskyy et al. (2009). Single‐channel analysis of outside‐out patches in the presence of carbachol (100 μM) in intestinal smooth muscle cells revealed activity of TRPC4 channels with unitary conductance 55 pS which underlied more than 80% of the muscarinic receptor‐induced cation current (Tsvilovskyy et al., 2009). In other studies, the unitary channel conductance of heterologously expressing TRPC4 was as follows: 41 pS (mTRPC4β), 30 pS (hTRPC4α), 28 pS (rTRPC4α), 30 pS (hTRPC4β), and 18 pS (mTRPC4β; Schaefer et al., 2002; Walker, Koh, Sergeant, Sanders, & Horowitz, 2002).

Many studies have reported that TRPC1 joins as a partner with other TRPC isoforms to form functional heteromeric channels, after heterologous expression in HEK 293 or COS (fibroblast‐like cell line derived from African green monkey kidney) cell lines. These channels are as follows: TRPC1/TRPC3 (Lintschinger et al., 2000; Storch et al., 2017), TRPC1/TRPC4 (Hofmann, Schaefer, Schultz, & Gudermann, 2002), TRPC1/TRPC5 (Hofmann et al., 2002; Strübing et al., 2001), TRPC1/TRPC6, and TRPC1/TRPC7 (Dietrich et al., 2014; Storch, Forst, Philipp, Gudermann, & Mederos y Schnitzler, 2012). It is worth mentioning that TRPC1 is also able to interact with other TRP channel subfamilies (TRPP1, TRPV1, TRPV4, and TRPV6) and other proteins (Dietrich et al., 2014). Also, it has been reported that TRPC4 is able to join as a partner with other TRPC subfamilies (TRPC3, TRPC5, and TRPC6) as heterologous expression (Freichel et al., 2014).

In addition, as mentioned earlier, native heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels have been reported in different cancer cell lines (Minard et al., 2018). Whole‐cell patch clamp currents of native heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels activated by 100 nM EA in A498 cells and SW982 cells were described in different studies (Akbulut et al., 2015; Muraki et al., 2017). Interestingly, in both cancer cells, A498 and SW982, the EA‐induced cytotoxicity was mediated by Na+ entry and not Ca2+ through heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels. Likewise, another study showed that the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels are involved in cardiac remodelling (Camacho Londono et al., 2015). These studies and others suggest the native TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC5 channels involved in human physiology and pathology predominantly exist as heteromeric channels or in combination with other subfamilies of TRPC channels or proteins (Akbulut et al., 2015; Broker‐Lai et al., 2017; Camacho Londono et al., 2015; Minard et al., 2018; Muraki et al., 2017; Schaefer, 2005; Strübing et al., 2001; Sukumar et al., 2012).

1.9. The pharmacology of TRPC1/4/5 channels

Just recently, nonselective and weak pharmacological tools, such as lanthanide ions (La3+, Gd3+), GPCR agonists, (carbachol), and 2‐aminoethoxydiphenyl borate or SFK96365 were used as activators or blockers of TRPC1/4/5 channels, respectively, to determine the contributions of these proteins to human physiology and pathology (Beech, 2007; Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017). However, remarkable progress with small‐molecule modulation of TRPC1/4/5 channels has occurred and treasure troves of pharmacological tools to study TRPC1/4/5 channels have been identified (Akbulut et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2011; Minard et al., 2018; Naylor et al., 2016; Richter, Schaefer, & Hill, 2014a; Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017). Recent publications that have identified and characterized novels of high‐quality, potent, and selective modulators of TRPC1/4/5 channels, such as EA, TZL, Pico145, and ML204 and others, will be discussed in this review (Akbulut et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2011; Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018).

1.10. The novel TRPC1/4/5 channels agonists

1.10.1. (−)‐Englerin A

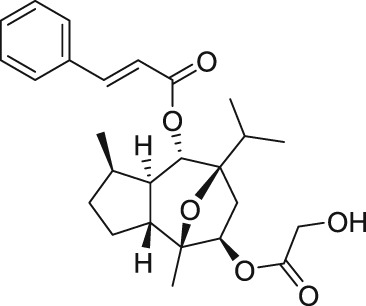

EA derives from the bark of the Phyllanthus engleri tree, an East African plant (Table 1). The EA molecule was first isolated in 2009 and a group led by Professor Echavarren was the first to achieve total synthesis of EA a year later (Molawi, Delpont, & Echavarren, 2010; Ratnayake et al., 2009). The EA compound has the ability to selectively destroy renal cancer cells through the activation of TRPC1/4/5 (Akbulut et al., 2015). Renal cancer is commonly treated surgically and it responds poorly to existing drugs, which have serious side effects (Gaunt et al., 2016). However, there are two issues which prevent the use of EA in the pharmaceutical treatment of cancer, that is, the compound is too unstable and toxic (Cheung et al., 2018). Therefore, there is a high demand for an EA analogue, which is potent, metabolic stable, and non‐toxic that could lead to a more effective treatment against renal cancer.

Table 1.

TRPC1/4/5 channels activators

| Name | EC50 (channel) | Chemical structure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| (−)‐Englerin A | 11.2 nM (TRPC4) |

|

Akbulut et al. ( 2015 ) |

| 7.6 nM (TRPC5) | |||

| Tonantzitlolone | 123 nM (TRPC4) |

|

Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al. ( 2018 ) |

| 83 nM (TRPC5) | |||

| 140 nM (TRPC4‐TRPC1, concatemers) | |||

| 61 nM (TRPC5‐TRPC1, concatemers) | |||

| BTD | 1.4 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Beckmann et al. ( 2017 ) |

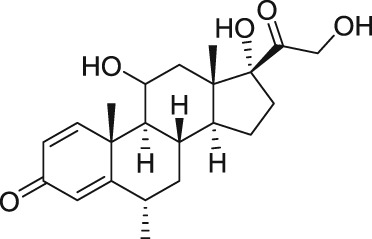

| Methylprednisolone | 12 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Beckmann et al. ( 2017 ) |

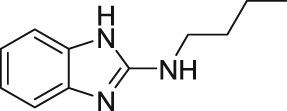

| Riluzole | 9.2 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Richter et al. ( 2014b ) |

| Rosiglitazone | 31 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Majeed et al. ( 2011 ) |

EA has shown effect on the outside‐out patch, suggesting EA binds directly to human homomeric TRPC5 channels overexpressed in HEK 293 cells (Ludlow et al., 2017; Naylor et al., 2016). Ludlow et al. (2017) reported that the effect of EA is through Na+ instead of what was previously thought through Ca2+ in TRPC4‐containing channels.

EA is a highly potent, and specific activator of both homomeric and heteromeric TRPC1/4/5 channels; therefore, it can be used as a pharmacological tool to study these proteins (Akbulut et al., 2015; Cheung et al., 2018; Ludlow et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018). As stated, EA has a potent cytotoxic effect on a number of cancer cell types which are mediated by TRPC1/4/5 channels (Akbulut et al., 2015; Ludlow et al., 2017; Ratnayake et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2017). The concentration of EA required for 50% activation (EC50) of human homomeric TRPC4 channels overexpressed in HEK 293 cells demonstrated a potent value of 11.2 nM, and for homomeric TRPC5, the potency was also at a high value of 7.6 nM (Akbulut et al., 2015).

The mechanism of action of EA is still poorly understood; however, EA activates the overexpressed human homomeric TRPC4 or TRPC5 channels in HEK 293 cells (Akbulut et al., 2015; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). There is no strong evidence that EA directly binds to the TRPC1/4/5 channels. Nevertheless, EA is effective in outside‐out patches, suggesting EA probably acts directly on the extracellular site of these channels or that part accessible only at the external leaflet of the bilayer (Akbulut et al., 2015; Ludlow et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). Previously, it was thought that EA kills A498 cancer cells through Ca2+ entry (Akbulut et al., 2015). Recently, two different studies aimed to understand how activation of TRPC4‐containing channels by EA results in rapid cancer cell death in two different cancer cells A498 and SW982 (Ludlow et al., 2017; Muraki et al., 2017). Strikingly, they reported that EA‐evoked cytotoxicity is mediated by Na+ influx through the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels in these two different cancer cell lines (Ludlow et al., 2017; Muraki et al., 2017).

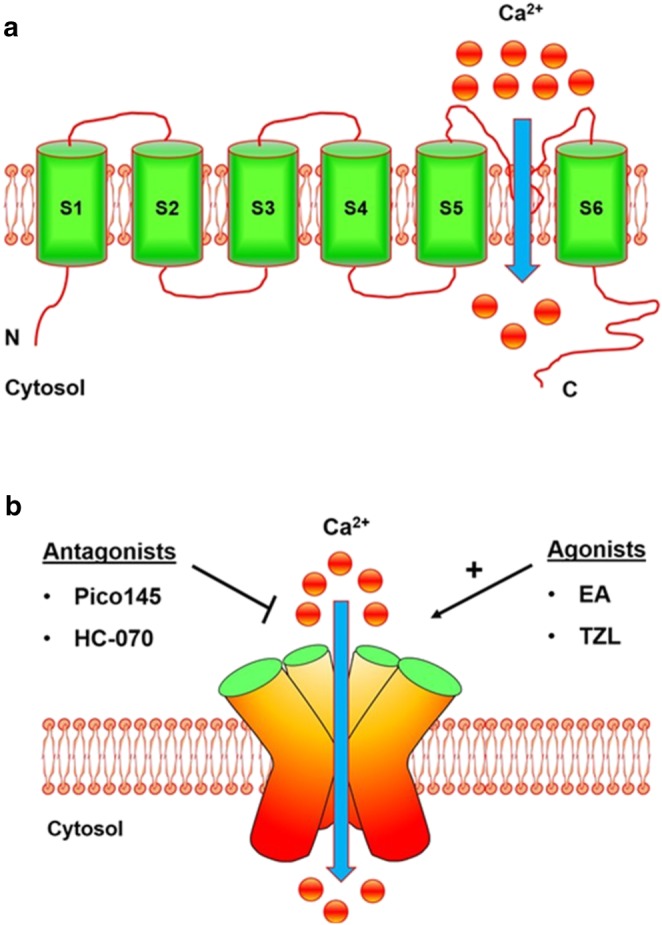

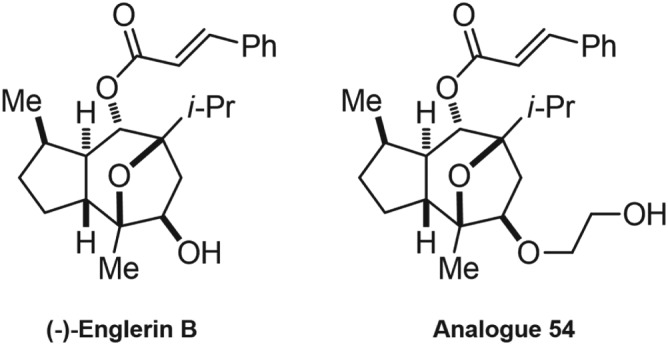

More recently, Rubaiy, Seitz, et al. (2018) also identified an analogue of EA, analogue 54 (A54, Figure 3), which has a competitive antagonist effect on EA and can possibly be administered as an antidote to EA poisoning. The study revealed that A54 was a potent inhibitor of the EA response, causing 50% inhibition at 62 nM in the A498 cells expressing endogenous EA‐responsive TRPC1/TRPC4 heteromeric channels (Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018). Moreover, the study revealed that 1 μM of A54 did not activate TRPC3 or inhibit or potentiate TRPC3‐mediated Ca2+ entry activated by the TRPC3 agonist 1‐oleoyl‐2‐acetyl‐sn‐glycerol (OAG). This suggests that A54 has no effect on other family members of the TRPC channels, namely TRPC3 (Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

The chemical structures of EA inactive metabolite, (−)‐englerin B, and the EA analogue, 54, which antagonizes EA at TRPC1/4/5 channels

1.10.2. (−)‐Englerin B

The chemical structure of (−)‐englerin B (EB) is shown in Figure 3. The EA inactive metabolite, EB, lacks the glycolic acid compared with EA (Table 1), which possibly indicates that this glycolic acid has an important role in EA's activity. Notably, EB is a useful tool to use as a control in the TRPC1/4/5 channels (Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018) and moreover, unlike EA, the EB did not cause toxicity in an in vivo study (Carson et al., 2015).

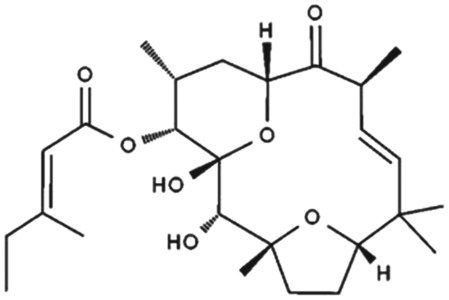

1.10.3. Tonantzitlolone

Recently, Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al. (2018) reported that the TZL is a potent activator of TRPC1/4/5 channels at nM concentrations. The diterpene ester TZL (Table 1) is a natural product isolated from the Mexican plant Stillingia sanguinolenta Müll. Arg. belonging to the Euphorbiaceae plant family (Busch et al., 2016; Busch & Kirschning, 2008; Jasper, Wittenberg, Quitschalle, Jakupovic, & Kirschning, 2005). TZL has been used as a medical plant in native Mexican, Navajo, and Creek traditional medicine, and importantly, it displays cytotoxicity against certain types of human cancer cell, including renal, ovarian, and breast cancer cells, at nM concentrations. Therefore, TZL has received much attention and is considered as a potential anticancer drug for certain cancers, such as renal cancer (Sourbier et al., 2015).

When TZL was screened against 60 human cancer cell lines, many cell lines were resistant to this compound. In this 60 human cancer cell lines cytotoxicity screen, TZL showed selectivity towards subtypes of cancer cells at high μM concentrations, indicating that it is selective for some cancer cells (Sourbier et al., 2015). Notably, the chemical structures of EA and TZL are completely distinctive (Table 1); however, the TZL profile in the screening was extremely comparable to EA (Ratnayake et al., 2009; Sourbier et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2017).

It has been suggested that the target for EA and TZL is the PKCθ, a PKC isoform (Sourbier et al., 2013; Sourbier et al., 2015). In more detail, Sourbier et al. (2015) reported that TZL is a potent PKC activator with tumour cytotoxicity that is commonly mediated by PKCθ. Nevertheless, the potency of TZL and EA at activating PKCθ is perhaps less than their potency in cytotoxicity assays (Sourbier et al., 2013; Sourbier et al., 2015). Therefore, Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al. (2018) reflected whether additional higher affinity targets might exist for these compound. Indeed, the Rubaiy et al. study showed that TZL is a novel potent agonist for TRPC1/4/5 channels, which should be useful for testing the functionality of these members of the TRPC subfamily and perhaps in understanding how TRPC1/4/5 agonists achieve cytotoxicity against certain types of cancer cells.

The potency of TZL on different isoforms of TRPC1/4/5 channels is shown in Table 1. TZL activated overexpressed channels with EC50s of 123 nM (homomeric TRPC4), 83 nM (homomeric TRPC5), 140 nM (TRPC4‐TRPC1, concatemers), and 61 nM (TRPC5‐TRPC1, concatemers; Table 1). Also, the effects of TZL were reversible on washout in patch‐clamp recordings and were strongly inhibited by the selective TRPC1/4/5 antagonist Pico145 (Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018;Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017 ; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). Interestingly, TZL activated TRPC5 channels when bath‐applied to excised outside‐out but not inside‐out patches. Moreover, TZL failed to activate endogenous store‐operated Ca2+ entry in HEK 293 cells or overexpressed TRPC3, TRPV4, or TRPM2 channels (Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018).

Similar to EA, TZL exhibited cytotoxicity against certain types of human cancer cell including A498 cells at nM concentrations (Sourbier et al., 2015). Also, TZL was effective in outside‐out patches, suggesting TZL possibly acts directly at the extracellular site of TRPC1/4/5 channels, but there is no evidence that TZL directly binds to the channels (Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018). However, TZL‐evoked cytotoxicity is likely mediated by Na+ influx through the heteromeric TRPC4/TRPC1 channels. Nevertheless, so far this topic has not been addressed experimentally.

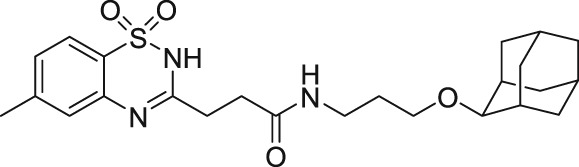

1.10.4. Benzothiadiazine derivative and methylprednisolone

Recently, two novel TRPC5 agonists, a benzothiadiazine derivative (BTD; Table 1) with EC50 = 1.4 μM and the glucocorticoid methylprednisolone with EC50 = 12 μM, have been identified through a screen of a ChemBioNet compound library by Beckmann et al. (2017). Moreover, these two activators were sensitive to clemizole (TRPC5 blocker; Table 2) and reversible (Beckmann et al., 2017). The BTD displayed selectivity for TRPC5 channels and failed to activate other TRP channels (TRPC3, TRPC6, TRPC7, TRPA1, TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPV4, TRPM2, and TRPM3). Also, the glucocorticoid methylprednisolone showed selectivity for TRPC5 and had no effect on other TRP channels but interestingly, it potentiated the carbachol‐induced activation of TRPC4 (Beckmann et al., 2017). What has not yet been identified is the binding sites for physiological activators of homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels such as BTD and methylprednisolone. Therefore, Beckmann et al. (2017) anticipated that a conclusive distinction between orthosteric and allosteric modes of TRPC5 activation is not yet possible.

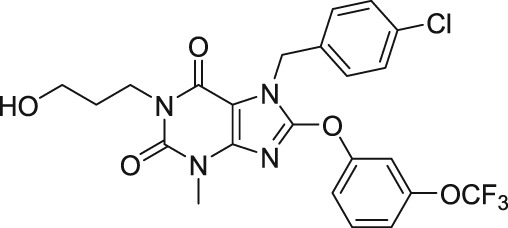

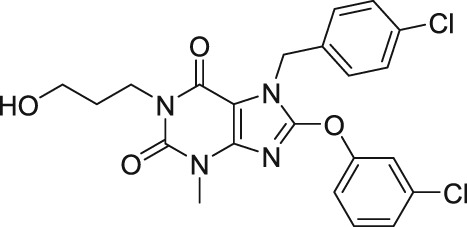

Table 2.

TRPC1/4/5 channels blockers

| Name | IC50 (channel) | Chemical structure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pico145 (HC‐608) | 49 pM (TRPC1/TRPC4, endogenous) |

|

Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al. ( 2017 ) |

| 33pM (TRPC4‐TRPC1, concatemers) | |||

| 199 pM (TPRC5‐TRPC1, concatemers) | |||

| 63 pM (TRPC4) | |||

| 1.3 nM (TRPC5) | |||

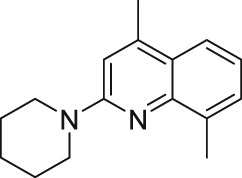

| HC‐070 | 0.3–2 nM (TRPC1/4/5) |

|

Just et al. ( 2018 ) |

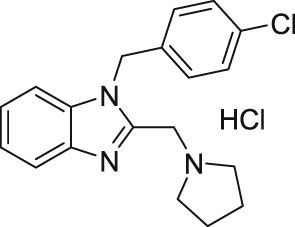

| Clemizole Hydrochloride | 6.4 μM (TRPC4) |

|

Richter et al. ( 2014a ) |

| 1.1 μM (TRPC5) | |||

| 9.1 μM (TRPC3) | |||

| 1.3 μM (TRPC6) | |||

| 26.5 μM (TRPC7) | |||

| ML204 | 0.99 μM (TRPC4) |

|

Miller et al. ( 2011); Zhou et al. ( 2017 ) |

| 9.2 μM (TRPC5) | |||

| M084 | 3.7–10.3 μM (TRPC4) |

|

Yang et al. ( 2015 ) |

| 8.2 μM (TRPC5) | |||

| 8.3 μM (TRPC1/TRPC4) | |||

| ~50 μM (TRPC3) | |||

| ~60 μM (TRPC6) | |||

| AC1903 | IC 50 > 100 μM (TRPC4) |

|

Zhou et al. ( 2017 ) |

| 14.7 μM (TRPC5) | |||

| Galangin | 0.45 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Naylor et al. ( 2016 ) |

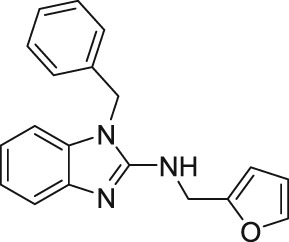

| AM‐12 | 0.28 μM (TRPC5) |

|

Naylor et al. ( 2016 ) |

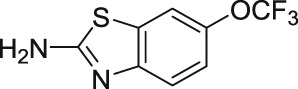

1.10.5. Riluzole

Riluzole (Table 1), a derivative of benzothiazole, has been identified as an activator of TRPC5 channels with an EC50 of 9.2 μM (Richter et al., 2014b). Its mechanism of action is independent of G protein signalling and PLC activity. TRPC5 activation by riluzole is reversible upon washout. Riluzole has been shown not to activate any other members of the TRPC family; thus, it could be a useful pharmacological tool for identifying drug targets for TRPC channel modulation. Currently, riluzole is administered clinically to treat psychiatric disorders and to delay the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Grant, Song, & Swedo, 2010; Schuster, Fu, Siddique, & Heckman, 2012). Excised inside‐out patch recordings revealed a relatively direct effect of riluzole on homomeric TRPC5 channels (Richter et al., 2014a).

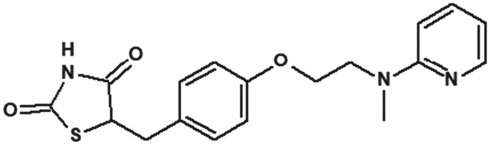

1.10.6. Rosiglitazone

Rosiglitazone, a high‐affinity ligand of the PPAR‐γ, activates TRPC5 channels with an EC50 of 31 μM and is reversible upon washout (Majeed et al., 2011). It has also been reported that rosiglitazone activates heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC5 channels (Sukumar et al., 2012). Rosigliatzole belongs to an antidiabetic drug group called thiazolidendione and acts as an insulin sensitizer. It has been withdrawn from clinical use in most countries, including the European market due to an increased risk of heart attacks and death. However, rosiglitazone is still available in the U.S. market without any restrictions. Rosiglitazone, as a potent agonist at PPAR in target tissues, is involved in insulin's action on adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver. Activated PPAR‐γ regulate the transcription of insulin‐responsive genes that are involved in the control of glucose production, its transport, and utilization resulting in enhanced tissue sensitivity to insulin.

1.10.7. Other activators of TRPC1/4/5 channels

Lanthanides (gadolinium ions [Gd3+] and lanthanum ions [La3+])

In contrast to TRP channels, which are inhibited or unaffected by lanthanides, the TPRC4 and TRPC5 channels are activated by external lanthanides (La3+ or Gd3+) at 1–100 μM (Jung et al., 2003; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018). However, the TPRC4 and TRPC5 channels are also inhibited by Gd3+ at higher concentrations (more than 100 μM; Beech, 2007). It has been suggested that the top end of the fifth membrane‐spanning segment of TRPC5 channels is the agonist‐binding site for the lanthanides.

In 2003, Jung et al. studied the effect of lanthanides (La3+ and Gd3+) on homomeric TRPC5 channels in depth. They reported that the lanthanides potentiate the homomeric TRPC5 currents by an action at extracellular sites close to the pore mouth of the channel (Jung et al., 2003). Interestingly, this study found that neutralization of three glutamates residues (E543, E595, and E598) results in a loss of this La3+‐mediated potentiation. These residues are similarly conserved in TRPC4 and located close to the transmembrane segments TM5 and TM6 of TRPC5 (Jung et al., 2003). Moreover, Jung et al. (2003) also reported that the lanthanides are able to increase the open probability of homomeric TRPC5 channels in single‐channel analysis and decrease the conductance in a dose‐dependent manner.

Nonlanthanides activators of TRPC1/4/5 channels

Several groups in various cell types have shown that homomeric TRPC4 or TRPC5 channels are activated by S1P, thioredoxin, ATP, thrombin, UTP, bradykinin, carbachol, histamine, and PGE2 (Beech, 2007; Ohta, Morishita, Mori, & Ito, 2004; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Rubaiy, Seitz, et al., 2018; Schaefer et al., 2000; Tabata et al., 2002; Venkatachalam, Zheng, & Gill, 2003; Xu et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2004).

2. THE NOVEL TRPC1/4/5 CHANNELS ANTAGONISTS

2.1. Pico145

Until recently, there has been no reliable selective and potent blocker for the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 or TRPC1/TRPC5 channels; however, investigators from Hydra Biosciences and Boehringer‐Ingelheim have examined the effects of substituted xanthines on TRPC5 channels and disclosed in a patent numerous compounds with IC50s less than 100 nM (Chenard & Gallaschun, 2014; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). A further in depth study was performed by Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, and Beech (2017) and Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al. (2017) to characterize the potency, specificity, and subtype selectivity of one of the most promising compounds in the patent, Pico145 (Table 2). The characterization of this high‐quality and remarkable small‐molecule antagonist revealed a potency ranging from 9 to 1,300 pM on the different TRPC1/4/5 subtypes. Therefore, this impressive pharmacological tool was named Pico145 (Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). Interestingly, the most striking result to emerge from the data was that the heteromeric channels TRPC4–TRPC1 and TRPC5–TRPC1 concatemers were more sensitive to Pico145 with IC50 values of 33 and 199 pM respectively. Moreover, Pico145 inhibited the endogenous EA‐evoked Ca2+ entry of heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels in A498 cells with an IC50 = 49 pM (Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). The most astonishing aspect of the data was that the other TRP channel types examined were unaffected by Pico145, including TRPC3, TRPC6, TRPV1, TRPV4, TRPA1, TRPM2, TRPM8, and store‐operated Ca2+ entry mediated by Orai1 (Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). Interestingly, the Pico145 was used in a separate study by its inventors, who identified it as HC‐608 (Just et al., 2018). Furthermore, anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of HC‐070, a close analogue of Pico145 (HC‐608), were demonstrated in mice in the same study by Just et al. (2018). As yet, the mechanism of action of Pico145 is still not known. Also, there is no evidence that Pico145 directly binds to the TRPC1/4/5 channels; however, Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al. (2017) showed that Pico145 is effective in outside‐out patches. These results suggest Pico145 has a direct effect on TRPC1/4/5 channels via the extracellular surface of the channels.

2.2. Clemizole

In 2014, Richter et al. (2014a) demonstrated the the histamine H1‐receptor agonist, clemizole hydrochloride (Table 2), as a novel potent inhibitor of mouse homomeric TRPC5 channels. The experiments (patch‐clamp recording and Ca2+ measurement assays) revealed that homomeric TRPC5 channels were inhibited by clemizole with an IC50 of 1.0–1.3 μM (Table 2). TRPC5 were sixfold more sensitive to clemizole compared to TRPC4 (IC50 = 6.4 μM) channels and 10‐fold more sensitive compared to TRPC3 (IC50 = 9.1 μM) and TRPC6 (IC50 = 11.3 μM) channels (Richter et al., 2014a). Interestingly, the same group revealed that the heteromeric TRPC1‐TRPC5 (heterologous coexpression) channels were also sensitive to clemizole (Richter et al., 2014a). In addition to its antihistaminergic effect, clemizole also blocks monoamine reuptake in the brain (Richter et al., 2014a). Richter et al. (2014a) studied the pharmacological effect of clemizole on homomeric TRPC5 channels. They reported that clemizole inhibits the homomeric TRPC5 currents regardless of the mode of activation such as stimulation of GPCRs or by the direct activator riluzole (Richter et al., 2014a). Furthermore, they showed that clemizole blocks the homomeric TRPC5 channels independently from its cytosolic components (in excised inside‐out membrane patches) or PLC activity. These results suggest a direct block of homomeric TRPC5 channels by clemizole. Notably, riluzole‐evoked TRPC5 currents in the U‐87 glioblastoma cell line (natively expressed) were also blocked by clemizole (Richter et al., 2014a). Richter et al. (2014a) concluded that clemizole does not inhibit GPCR, G protein, or PLC signalling, and soluble cytosolic components are not essential for its inhibitory effect on homomeric TRPC5 channels.

2.3. ML204

The small‐molecule ML204 (Table 2) was identified as an antagonist of homomeric TRPC4 (IC50 = 0.99 μM) and TRPC5 (IC50 = 9.2 μM) channels from a fluorescent screen evaluating compounds from the Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository library (Miller et al., 2011). Moreover, ML204 displayed a 19‐fold selectivity against muscarinic receptor‐coupled TRPC6 channel activation (Miller et al., 2011). Notably, the native TRPC1/4/5 channels predominantly exist as heteromeric combinations; therefore, a recent study by Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al. (2017) assessed the sensitivity of the heteromeric TRPC4‐TRPC1 (concatemers) channels to ML2014. The data revealed that the heteromeric TRPC4‐TRPC1 are less sensitive to ML204 with an IC50 = 58 μM (activation by EA 10 nM; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). To characterize the pharmacological effects of ML204, Miller et al. (2011) studied the effect of ML204 on homomeric TRPC4 by activating the channel via different mechanisms in whole‐cell patch clamp electrophysiology experiments. ML204 inhibited the homomeric TRPC4 currents, which were activated through either μ receptor stimulation or intracellular dialysis of GTPγS. These results proposed a direct interaction of ML204 with the homomeric TRPC4 channels and no blocking of the signal transduction pathways. Also, they showed that ML204 inhibition of homomeric TRPC4 channels is independent of GPCR activation Miller et al. (2011).

2.4. M084

M084, an (amino) benzimidazole‐based compound, inhibits homomeric TRPC4 and TRPC5 as well as heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channels. Its inhibitory action is reversible, although it is not as potent as ML204, it is more stable and has better inhibitory kinetics (Table 2). It has been reported that M084‐induced inhibition of TRPC1/4/5 channels has anxiolytic and antidepressant effects in mice; however, it is yet to be established if its effects are on homomeric or heteromeric channels (Yang et al., 2015). M084 could be a useful pharmacological tool providing an alternative structural scaffold for developing more potent TRPC4‐ and TRPC5‐selective antagonists (Zhu et al., 2015). Notably, since M084 and ML204 have similar structure–activity relationship profiles, Zhu et al. (2015) suggested that the mechanism of action of M084 is similar to that of ML204.

2.5. AC1903

Zhou et al. (2017) synthesized and tested a series of compounds (50 molecules) based on the structures of ML204 and clemizole and identified AC1903 as a promising candidate against TRPC4, TRPC5, and TRPC6. This group utilized AC1903 as a small‐molecule blocker of homomeric TRPC5 channels to suppress progressive kidney disease (Zhou et al., 2017). The homomeric TRPC4 channels were less sensitive to AC1903 with an IC50 > 100 μM compared to homomeric TRPC5 channels with an IC50 = 14.7 μM (Zhou et al., 2017). This study did not report on the sensitivity of heteromeric channels TRPC1/TRPC4 or TRPC1/TRPC5 to AC1903; however, this compound had no inhibitory effect at 100 μM on homomeric TRPC6 channels (Zhou et al., 2017). So far, the mechanism of action of AC1903 on homomeric TRPC4 or TRPC5 channels is not known. Since the identification of AC1903 was based on the structures of ML204 and clemizole, possibly, its mechanism of action is similar to that of ML204 or clemizole (Zhou et al., 2017).

2.6. Galangin and AM12

By screening a number of natural products, Naylor et al. (2016) found that the flavonol galangin (Table 2) blocks the human overexpressed homomeric TRPC5 channels in HEK293 cells. Galangin, which is from the ginger family, blocked the lanthanide‐evoked Ca2+ entry with IC50 = 0.45 μM (Naylor et al., 2016). Following this, structure–activity relationship studies of 48 natural and synthetic flavonols revealed a more potent analogue, AM12, with an IC50 = 0.28 μM at homomeric TRPC5 channels (Table 2). Furthermore, AM12 did not block other types of TRP channels (TRPC3, TRPV4, and TRPM2) or store‐operated calcium entry (Naylor et al., 2016). Furthermore, Naylor et al. (2016) reported that galangin and AM12 were effective in excised outside‐out membrane patches, suggesting these compounds possibly have a direct effect on the homomeric TRPC5 channels. However, there is no evidence that galangin and AM12 directly bind to the homomeric TRPC5 channels (Naylor et al., 2016). This group speculated that the mechanism of action of flavonoids on homomeric TRPC5 channels is local perturbation of the bilayer, which subsequently modulates the channel activity (Naylor et al., 2016).

In conclusion, in recent years, a remarkable evolution in the pharmacology of TRPC1/4/5 channels has emerged and several potent and selective small‐molecule modulators of TRPC1/4/5 channels have been identified. Perhaps, these treasure troves of pharmacological tools will permit the study of TPRC1/4/5 channels, as potential drug targets, in different tissues and cell types and aid in the understanding of the role of these channels in human health and disease.

3. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The TRPC ion channels are ubiquitously expressed and permit the influx of Ca2+ and Na+ ions into the cells. Therefore, they play important roles in many physiological and pathological mechanisms (Minard et al., 2018). The free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and voltage across the plasma membrane are major determinants of cell function and both are regulated by Ca2+‐permeable nonselective cation channels, such as TRPC1/4/5 (Clapham, 2007; Minard et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017). Nevertheless, our understanding of these ion channels in human health and diseases remains elusive. The breakthrough in TRPC1/4/5 pharmacology and the development of highly potent and highly selective TRPC1/4/5 agonists EA and TZL and antagonists Pico145 and HC‐070 offer for the first time opportunities to study TRPC1/4/5 channels in human health and disease, particularly Pico145 and HC‐070 for in vivo studies (Akbulut et al., 2015; Just et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, et al., 2018; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Bon, & Beech, 2017; Rubaiy, Ludlow, Henrot, et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2017).

In the past few years, the resolution revolution in cryo‐electron microscopy brought several high‐resolution structures of TRP channels. Recently, two different groups solved the electron cryo‐microscopy structure of the TRPC4 ion channel (Duan et al., 2018; Vinayagam et al., 2018). Vinayagam et al. (2018) reported a structure of mouse TRPC4 in its apo state to an overall resolution of 3.3 Å. The comparison of the mouse TRPC4 structure with other TRP channel structures solved earlier (human TRPM4, mouse TRPV1, human TRPA1, human TRPP1, and mouse TRP mucolipin 1) revealed similarities as expected (Duan et al., 2018). The TRPC4 organization of six helices in each transmembrane domain is comparable to that of other TRP channels, although the intracellular architecture is different. Interestingly, overlaying a TRPC4 monomer with representative TRP monomers from each TRP subfamily revealed that the overall fold of TRPC4 was closest to that of TRPM4 (Vinayagam et al., 2018). Conceivably, this insight into TRPC4 structures permits predictions about binding sites, which probably exist on the channel for modulators such as EA, TZL, and Pico145 and can preferably be supplemented by costructural data for ligands and the channel together.

Together, these treasure troves of agonists and antagonists of TRPC1/4/5 channels offer valuable aids to comprehend the functional importance of these channels in native cells and in vivo animal models. Importantly, diseases mediated by these channels can be studied using these compounds, perhaps initiating drug discovery efforts to develop novel therapeutic agents.

3.1. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander, Christopoulos et al., 2017; Alexander, Cidlowski et al., 2017; Alexander, Fabbro et al., 2017; Alexander, Kelly et al., 2017; Alexander, Striessnig et al., 2017).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Rubaiy HN. Treasure troves of pharmacological tools to study transient receptor potential canonical 1/4/5 channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:832–846. 10.1111/bph.14578

REFERENCES

- Akbulut, Y. , Gaunt, H. J. , Muraki, K. , Ludlow, M. J. , Amer, M. S. , Bruns, A. , … Waldmann, H. (2015). (−)‐Englerin A is a potent and selective activator of TRPC4 and TRPC5 calcium channels. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 54, 3787–3791. 10.1002/anie.201411511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alawi, K. M. , Russell, F. A. , Aubdool, A. A. , Srivastava, S. , Riffo‐Vasquez, Y. , Baldissera, L. Jr. , … Brain, S. D. (2017). Transient receptor potential canonical 5 (TRPC5) protects against pain and vascular inflammation in arthritis and joint inflammation. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 76, 252–260. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Christopoulos, A. , Davenport, A. P. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein‐coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S17–S129. 10.1111/bph.13878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Cidlowski, J. A. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Nuclear hormone receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S208–S224. 10.1111/bph.13880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S272–S359. 10.1111/bph.13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , Harding, S. D. , … Davies, J. A. (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Overview. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(Suppl 1), S1–S16. 10.1111/bph.13882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Striessnig, J. , Kelly, E. , Marrion, N. V. , Peters, J. A. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators (2017). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Voltage‐gated ion channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174(S1), S160–S194. 10.1111/bph.13884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzoubi, A. , Almalouf, P. , Toba, M. , O'Neill, K. , Qian, X. , Francis, M. , … Stevens, T. (2013). TRPC4 inactivation confers a survival benefit in severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. The American Journal of Pathology, 183, 1779–1788. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagal, S. K. , Brown, A. D. , Cox, P. J. , Omoto, K. , Owen, R. M. , Pryde, D. C. , … Swain, N. A. (2013). Ion channels as therapeutic targets: A drug discovery perspective. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 56, 593–624. 10.1021/jm3011433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batova, A. , Altomare, D. , Creek, K. E. , Naviaux, R. K. , Wang, L. , Li, K. , … Yu, A. L. (2017). Englerin A induces an acute inflammatory response and reveals lipid metabolism and ER stress as targetable vulnerabilities in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One, 12, e0172632 10.1371/journal.pone.0172632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, H. , Richter, J. , Hill, K. , Urban, N. , Lemoine, H. , & Schaefer, M. (2017). A benzothiadiazine derivative and methylprednisolone are novel and selective activators of transient receptor potential canonical 5 (TRPC5) channels. Cell Calcium, 66, 10–18. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech, D. J. (2007). Canonical transient receptor potential 5. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 109–123. 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech, D. J. (2012). Integration of transient receptor potential canonical channels with lipids. Acta Physiologica (Oxford, England), 204, 227–237. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02311.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech, D. J. (2013). Characteristics of transient receptor potential canonical calcium‐permeable channels and their relevance to vascular physiology and disease. Circulation Journal, 77, 570–579. 10.1253/circj.CJ-13-0154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzerides, V. J. , Ramsey, I. S. , Kotecha, S. , Greka, A. , & Clapham, D. E. (2004). Rapid vesicular translocation and insertion of TRP channels. Nature Cell Biology, 6, 709–720. 10.1038/ncb1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broker‐Lai, J. , Kollewe, A. , Schindeldecker, B. , Pohle, J. , Nguyen Chi, V. , Mathar, I. , … Freichel, M. (2017). Heteromeric channels formed by TRPC1, TRPC4 and TRPC5 define hippocampal synaptic transmission and working memory. The EMBO Journal, 36, 2770–2789. 10.15252/embj.201696369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, T. , Drager, G. , Kunst, E. , Benson, H. , Sasse, F. , Siems, K. , & Kirschning, A. (2016). Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of new tonantzitlolone‐derived diterpene derivatives. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 14, 9040–9045. 10.1039/C6OB01697A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, T. , & Kirschning, A. (2008). Recent advances in the total synthesis of pharmaceutically relevant diterpenes. Natural Product Reports, 25, 318–341. 10.1039/b705652b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Londono, J. E. , Tian, Q. , Hammer, K. , Schroder, L. , Camacho Londono, J. , Reil, J. C. , … Lipp, P. (2015). A background Ca2+ entry pathway mediated by TRPC1/TRPC4 is critical for development of pathological cardiac remodelling. European Heart Journal, 36, 2257–2266. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, C. , Raman, P. , Tullai, J. , Xu, L. , Henault, M. , Thomas, E. , … Solomon, J. M. (2015). Englerin A agonizes the TRPC4/C5 cation channels to inhibit tumor cell line proliferation. PLoS One, 10, e0127498 10.1371/journal.pone.0127498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenard, B. , & Gallaschun, R. (2014). Substituted xanthines and methods of use thereof.ed. Organization I.P.A.W.I.P.

- Cheung, S. Y. , Henrot, M. , Al‐Saad, M. , Baumann, M. , Muller, H. , Unger, A. , … Vasudev, N. S. (2018). TRPC4/TRPC5 channels mediate adverse reaction to the cancer cell cytotoxic agent (−)‐englerin A. Oncotarget, 9, 29634–29643. 10.18632/oncotarget.25659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, D. E. (2003). TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature, 426, 517–524. 10.1038/nature02196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, D. E. (2007). Calcium signaling. Cell, 131, 1047–1058. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, A. , Fahlbusch, M. , & Gudermann, T. (2014). Classical transient receptor potential 1 (TRPC1): Channel or channel regulator? Cell, 3, 939–962. 10.3390/cells3040939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J. , Li, J. , Zeng, B. , Chen, G. L. , Peng, X. , Zhang, Y. , … Zhang, J. (2018). Structure of the mouse TRPC4 ion channel. Nature Communications, 9, 3102 10.1038/s41467-018-05247-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. , Xu, N. , Zhou, C. , & Stevens, T. (2016). Transient receptor potential channel 4 encodes a vascular permeability defect and high‐frequency Ca(2+) transients in severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. The American Journal of Pathology, 186, 1701–1709. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freichel, M. , Tsvilovskyy, V. , & Camacho‐Londono, J. E. (2014). TRPC4‐ and TRPC4‐containing channels. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 222, 85–128. 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt, H. J. , Vasudev, N. S. , & Beech, D. J. (2016). Transient receptor potential canonical 4 and 5 proteins as targets in cancer therapeutics. European Biophysics Journal, 45, 611–620. 10.1007/s00249-016-1142-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, P. , Song, J. Y. , & Swedo, S. E. (2010). Review of the use of the glutamate antagonist riluzole in psychiatric disorders and a description of recent use in childhood obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 20, 309–315. 10.1089/cap.2010.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteneck, C. , Plant, T. D. , & Schultz, G. (2000). From worm to man: Three subfamilies of TRP channels. Trends in Neurosciences, 23, 159–166. 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01532-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, T. , Schaefer, M. , Schultz, G. , & Gudermann, T. (2002). Subunit composition of mammalian transient receptor potential channels in living cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 7461–7466. 10.1073/pnas.102596199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper, C. , Wittenberg, R. , Quitschalle, M. , Jakupovic, J. , & Kirschning, A. (2005). Total synthesis and elucidation of the absolute configuration of the diterpene tonantzitlolone. Organic Letters, 7, 479–482. 10.1021/ol047559e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S. , Muhle, A. , Schaefer, M. , Strotmann, R. , Schultz, G. , & Plant, T. D. (2003). Lanthanides potentiate TRPC5 currents by an action at extracellular sites close to the pore mouth. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278, 3562–3571. 10.1074/jbc.M211484200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just, S. , Chenard, B. L. , Ceci, A. , Strassmaier, T. , Chong, J. A. , Blair, N. T. , … Moran, M. M. (2018). Treatment with HC‐070, a potent inhibitor of TRPC4 and TRPC5, leads to anxiolytic and antidepressant effects in mice. PLoS One, 13, e0191225 10.1371/journal.pone.0191225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Kim, J. , Jeon, J. P. , Myeong, J. , Wie, J. , Hong, C. , … So, I. (2012). The roles of G proteins in the activation of TRPC4 and TRPC5 transient receptor potential channels. Channels (Austin), 6, 333–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout, D. , Schaar, A. , Sun, Y. , Sukumaran, P. , Roemmich, J. N. , Singh, B. B. , & Claycombe‐Larson, K. J. (2017). The TRPC1 Ca(2+)‐permeable channel inhibits exercise‐induced protection against high‐fat diet‐induced obesity and type II diabetes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292, 20799–20807. 10.1074/jbc.M117.809954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, O. C. , Shen, B. , Wong, C. O. , Tjong, Y. W. , Lo, C. Y. , Wang, H. C. , … Yao, X. (2016). TRPC5 channels participate in pressure‐sensing in aortic baroreceptors. Nature Communications, 7, 11947 10.1038/ncomms11947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. M. , Kim, B. J. , Kim, H. J. , Yang, D. K. , Zhu, M. H. , Lee, K. P. , … Kim, K. W. (2003). TRPC5 as a candidate for the nonselective cation channel activated by muscarinic stimulation in murine stomach. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 284, G604–G616. 10.1152/ajpgi.00069.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, S. , Morelli, M. B. , Nabissi, M. , Santoni, M. , & Santoni, G. (2013). Oncogenic and anti‐oncogenic effects of transient receptor potential channels. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 13, 344–366. 10.2174/1568026611313030011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintschinger, B. , Balzer‐Geldsetzer, M. , Baskaran, T. , Graier, W. F. , Romanin, C. , Zhu, M. X. , & Groschner, K. (2000). Coassembly of Trp1 and Trp3 proteins generates diacylglycerol‐ and Ca2+‐sensitive cation channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275, 27799–27805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, M. J. , Gaunt, H. J. , Rubaiy, H. N. , Musialowski, K. E. , Blythe, N. M. , Vasudev, N. S. , … Beech, D. J. (2017). (−)‐Englerin A‐evoked cytotoxicity is mediated by Na+ influx and counteracted by Na+/K+‐ATPase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292, 723–731. 10.1074/jbc.M116.755678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, Y. , Bahnasi, Y. , Seymour, V. A. , Wilson, L. A. , Milligan, C. J. , Agarwal, A. K. , … Beech, D. J. (2011). Rapid and contrasting effects of rosiglitazone on transient receptor potential TRPM3 and TRPC5 channels. Molecular Pharmacology, 79, 1023–1030. 10.1124/mol.110.069922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. , Shi, J. , Zhu, Y. , Kustov, M. , Tian, J. B. , Stevens, A. , … Zhu, M. X. (2011). Identification of ML204, a novel potent antagonist that selectively modulates native TRPC4/C5 ion channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286, 33436–33446. 10.1074/jbc.M111.274167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard, A. , Bauer, C. C. , Wright, D. J. , Rubaiy, H. N. , Muraki, K. , Beech, D. J. , & Bon, R. S. (2018). Remarkable progress with small‐molecule modulation of TRPC1/4/5 channels: Implications for understanding the channels in health and disease. Cell, 7, E52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke, B. , Wu, C. , & Pak, W. L. (1975). Induction of photoreceptor voltage noise in the dark in Drosophila mutant. Nature, 258, 84–87. 10.1038/258084a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molawi, K. , Delpont, N. , & Echavarren, A. M. (2010). Enantioselective synthesis of (−)‐englerins A and B. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English), 49, 3517–3519. 10.1002/anie.201000890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraki, K. , Ohnishi, K. , Takezawa, A. , Suzuki, H. , Hatano, N. , Muraki, Y. , … Beech, D. J. (2017). Na(+) entry through heteromeric TRPC4/C1 channels mediates (−)englerin A‐induced cytotoxicity in synovial sarcoma cells. Scientific Reports, 7, 16988 10.1038/s41598-017-17303-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, J. , Minard, A. , Gaunt, H. J. , Amer, M. S. , Wilson, L. A. , Migliore, M. , … Bon, R. S. (2016). Natural and synthetic flavonoid modulation of TRPC5 channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173, 562–574. 10.1111/bph.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius, B. , & Szallasi, A. (2014). Transient receptor potential channels as drug targets: From the science of basic research to the art of medicine. Pharmacological Reviews, 66, 676–814. 10.1124/pr.113.008268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obukhov, A. G. , & Nowycky, M. C. (2005). A cytosolic residue mediates Mg2+ block and regulates inward current amplitude of a transient receptor potential channel. The Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 1234–1239. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4451-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obukhov, A. G. , & Nowycky, M. C. (2008). TRPC5 channels undergo changes in gating properties during the activation‐deactivation cycle. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 216, 162–171. 10.1002/jcp.21388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada, T. , Shimizu, S. , Wakamori, M. , Maeda, A. , Kurosaki, T. , Takada, N. , … Mori, Y. (1998). Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel receptor‐activated TRP Ca2+ channel from mouse brain. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273, 10279–10287. 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordaz, B. , Tang, J. , Xiao, R. , Salgado, A. , Sampieri, A. , Zhu, M. X. , & Vaca, L. (2005). Calmodulin and calcium interplay in the modulation of TRPC5 channel activity. Identification of a novel C‐terminal domain for calcium/calmodulin‐mediated facilitation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280, 30788–30796. 10.1074/jbc.M504745200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, T. , Morishita, M. , Mori, Y. , & Ito, S. (2004). Ca2+ store‐independent augmentation of [Ca2+]i responses to G‐protein coupled receptor activation in recombinantly TRPC5‐expressed rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. Neuroscience Letters, 358, 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, K. D. , Shwe, U. T. , Abramowitz, J. , Wu, H. , Rhee, S. W. , Howell, M. D. , … Zheng, F. (2013). Canonical transient receptor channel 5 (TRPC5) and TRPC1/4 contribute to seizure and excitotoxicity by distinct cellular mechanisms. Molecular Pharmacology, 83, 429–438. 10.1124/mol.112.082271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnayake, R. , Covell, D. , Ransom, T. T. , Gustafson, K. R. , & Beutler, J. A. (2009). Englerin A, a selective inhibitor of renal cancer cell growth, from Phyllanthus engleri. Organic Letters, 11, 57–60. 10.1021/ol802339w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio, A. , Li, Y. , Moon, J. , Kim, K. S. , Smith, K. S. , Rudolph, U. , … Clapham, D. E. (2009). Essential role for TRPC5 in amygdala function and fear‐related behavior. Cell, 137, 761–772. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio, A. , Li, Y. , Tsvetkov, E. , Gapon, S. , Yao, G. L. , Smith, K. S. , … Clapham, D. E. (2014). Decreased anxiety‐like behavior and Gαq/11‐dependent responses in the amygdala of mice lacking TRPC4 channels. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 3653–3667. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2274-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, J. M. , Schaefer, M. , & Hill, K. (2014a). Clemizole hydrochloride is a novel and potent inhibitor of transient receptor potential channel TRPC5. Molecular Pharmacology, 86, 514–521. 10.1124/mol.114.093229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, J. M. , Schaefer, M. , & Hill, K. (2014b). Riluzole activates TRPC5 channels independently of PLC activity. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171, 158–170. 10.1111/bph.12436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaiy, H. N. (2017). A short guide to electrophysiology and ion channels. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences, 20, 48–67. 10.18433/J32P6R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaiy, H. N. , Ludlow, M. J. , Bon, R. S. , & Beech, D. J. (2017). Pico145—Powerful new tool for TRPC1/4/5 channels. Channels (Austin, Tex.), 11, 362–364. 10.1080/19336950.2017.1317485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaiy, H. N. , Ludlow, M. J. , Henrot, M. , Gaunt, H. J. , Miteva, K. , Cheung, S. Y. , … Beech, D. J. (2017). Picomolar, selective, and subtype‐specific small‐molecule inhibition of TRPC1/4/5 channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292, 8158–8173. 10.1074/jbc.M116.773556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaiy, H. N. , Ludlow, M. J. , Siems, K. , Norman, K. , Foster, R. , Wolf, D. , … Beech, D. J. (2018). Tonantzitlolone is a nanomolar potency activator of TRPC1/4/5 channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 3361–3368. 10.1111/bph.14379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubaiy, H. N. , Seitz, T. , Hahn, S. , Choidas, A. , Habenberger, P. , Klebl, B. , … Beech, D. J. (2018). Identification of an (−)‐englerin A analogue, which antagonizes (−)‐englerin A at TRPC1/4/5 channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 830–839. 10.1111/bph.14128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura, H. , & Ashcroft, F. M. (1997). Identification of four trp1 gene variants murine pancreatic beta‐cells. Diabetologia, 40, 528–532. 10.1007/s001250050711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M. (2005). Homo‐ and heteromeric assembly of TRP channel subunits. Pflügers Archiv, 451, 35–42. 10.1007/s00424-005-1467-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M. , Plant, T. D. , Obukhov, A. G. , Hofmann, T. , Gudermann, T. , & Schultz, G. (2000). Receptor‐mediated regulation of the nonselective cation channels TRPC4 and TRPC5. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275, 17517–17526. 10.1074/jbc.275.23.17517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M. , Plant, T. D. , Stresow, N. , Albrecht, N. , & Schultz, G. (2002). Functional differences between TRPC4 splice variants. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277, 3752–3759. 10.1074/jbc.M109850200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaldecker, T. , Kim, S. , Tarabanis, C. , Tian, D. , Hakroush, S. , Castonguay, P. , … Greka, A. (2013). Inhibition of the TRPC5 ion channel protects the kidney filter. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 123, 5298–5309. 10.1172/JCI71165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, J. E. , Fu, R. , Siddique, T. , & Heckman, C. J. (2012). Effect of prolonged riluzole exposure on cultured motoneurons in a mouse model of ALS. Journal of Neurophysiology, 107, 484–492. 10.1152/jn.00714.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourbier, C. , Scroggins, B. T. , Mannes, P. Z. , Liao, P. J. , Siems, K. , Wolf, D. , … Neckers, L. (2015). Tonantzitlolone cytotoxicity toward renal cancer cells is PKCtheta‐ and HSF1‐dependent. Oncotarget, 6, 29963–29974. 10.18632/oncotarget.4676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]