Abstract

Current shoulder clinical range of motion (ROM) assessments (e.g., goniometric ROM) may not adequately represent shoulder function beyond controlled clinical settings. Relative inertial measurement unit (IMU) motion quantifies ROM precisely and can be used outside of clinic settings capturing “real-world” shoulder function. A novel IMU-based shoulder elevation quantification method was developed via IMUs affixed to the sternum/humerus, respectively. This system was then compared to in-laboratory motion capture (MOCAP) during prescribed motions (flexion, abduction, scaption, and internal/external rotation). MOCAP/IMU elevation were equivalent during flexion (R2 = 0.96, μError = 1.7 deg), abduction (R2 = 0.96, μError = 2.9 deg), scaption (R2 = 0.98, μError = −0.3 deg), and internal/external rotation (R2 = 0.90, μError = 0.4 deg). When combined across movements, MOCAP/IMU elevation were equal (R2 = 0.98, μError = 1.4 deg). Following validation, the IMU-based system was deployed prospectively capturing continuous shoulder elevation in 10 healthy individuals (4 M, 69 ± 20 years) without shoulder pathology for seven consecutive days (13.5 ± 2.9 h/day). Elevation was calculated continuously daily and outcome metrics included percent spent in discrete ROM (e.g., 0–5 deg and 5–10 deg), repeated maximum elevation (i.e., >10 occurrences), and maximum/average elevation. Average elevation was 40 ± 6 deg. Maximum with >10 occurrences and maximum were on average 145–150 deg and 169 ± 8 deg, respectively. Subjects spent the vast majority of the day (97%) below 90 deg of elevation, with the most time spent in the 25–30 deg range (9.7%). This study demonstrates that individuals have the ability to achieve large ROMs but do not frequently do so. These results are consistent with the previously established lab-based measures. Moreover, they further inform how healthy individuals utilize their shoulders and may provide clinicians a reference for postsurgical ROM.

Keywords: arthroplasty, shoulder, inertial measurement unit, rehabilitation, range of motion

Introduction

Range of motion (ROM) is one of the most commonly used objective metrics to judge a patient's shoulder disability level and the success of surgical interventions [1–4]. Maximum ROM is typically assessed in the clinic by the operating surgeon or other clinicians at regular intervals during the postoperative recovery period [5–7]. However, little is known about ROM utilization requirements for everyday activities outside of well-controlled environments. In short, the maximum ROM a patient demonstrates for a clinician may not correlate with the ROM they frequently utilize in their home environments. As with other joints, shoulder ROM can be assessed in three biomechanical planes. Per the International Society of Biomechanics (ISB) standards on thoracohumeral motion, these are elevation (i.e., how high the humerus is elevated), plane of elevation (i.e., forward flexion versus abduction), and axial rotation (i.e., internal/external rotation) [8]. However, several groups have identified that shoulder elevation is the most critical metric for completing the majority of activities of daily living (ADL) [9,10].

Improving shoulder elevation is also a fundamental goal during post-shoulder surgery physical therapy [11]. This is especially true after shoulder arthroplasty, the fastest-growing total joint arthroplasty procedure in the United States [12]. Currently, pre- and postoperative shoulder ROM is captured through techniques like fluoroscopy, optical motion-capture (MOCAP), and goniometry in controlled clinical settings while performing idealized movements (e.g., repeated forward flexion) [13–17]. These measurements accurately capture a single discrete time point. However, they consume significant financial and time resources, have limited scalability, and may not accurately represent “real-world” shoulder function. Therefore, ROM measurement techniques are needed that are more cost effective, scalable, and representative of how patients move outside of a clinical setting.

One promising method for capturing ROM outside the clinical environment is inertial measurement units (IMUs). IMUs are miniaturized, portable, electromechanical devices that consist of some combination of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. The relative motion between two IMUs mounted in different locations can be used to capture an angle of interest between the IMUs. For example, IMUs attached to the sternum and humerus, respectively, can be used to compute shoulder elevation in real time. Many groups have attempted this, though prior work has focused on improving IMU-based shoulder ROM measurement precision during short-term laboratory-based experiments [18,19]. While the precision of IMU-based shoulder ROM measurements has improved through these efforts, the current methods remain limited in terms of scalability and computational demand. Few studies have captured upper extremity kinematic features for longer durations outside of laboratory settings. Coley et al. captured upper extremity data for 8 h via IMUs attached only to the humerus [20]. They compared known upper extremity position/acceleration combinations to assess how frequently individuals moved their upper arm to specific ROMs (e.g., 0–20 deg and 20–40 deg). They found that individuals spent the majority of time (>90%) under 90 deg of elevation. While their work showed that long duration shoulder elevation monitoring was possible outside of the lab/clinic, their method was largely limited by only attaching IMUs to one bony segment (i.e., distal humerus). By doing so, the relative orientation of the humerus and torso was incalculable. Accordingly, distinguishing between true humeral elevation and whole upper body rotation was not feasible (i.e., it is not possible to differentiate between 90 deg of abduction and a side lying posture).

The first goal of the present work is to develop a novel ROM measurement method capable of deployment outside the laboratory and clinical setting (i.e., in the patient's home environment) using the relative motion between two IMUs to continuously capture shoulder elevation. The second goal of this work is to perform a prospective analysis of the previously developed method to continuously capture shoulder elevation for long durations (7 consecutive days, approximately 12 h/day). A large gap exists in the literature with respect to normal shoulder ROM in healthy individuals outside of laboratory and clinical settings. As such, the focus population for this work is healthy individuals with no pre-existing shoulder dysfunction.

We hypothesize that the study cohort will achieve similar maximal ROM values to the previously established lab-based norms (≥150 deg) when calculated by the proposed IMU method [9,10,21–23]. Second, we hypothesize that the study cohort will spend a similarly low amount of time (<10% of each day) with their shoulder elevated above 90 deg when assessed by the proposed IMU method as compared to results noted in Coley et al. [20].

Methods

A four-step process was employed to develop and validate a tool capable of precisely measuring shoulder elevation over long durations with IMUs. First, analyses were completed on the theoretical function of IMUs as well as the geometric assumptions of the joint of interest (shoulder). Second, the proposed IMU-based ROM measurement system was validated against optical MOCAP during a series of prescribed upper extremity movements. Third, a workflow was developed to facilitate daily IMU use and data capture. Finally, utilizing this workflow, the system was deployed in an Institutional Review Board approved prospective study capturing long-term continuous shoulder elevation in healthy individuals.

Methods: Theoretical Analyses.

As noted earlier, IMUs capture some combination of acceleration, angular velocity, and magnetic field strength on up to three orthogonal axes. Using these inertial measures, the goal was to develop an efficient solution with respect to computational complexity, battery-life, and data management using the fewest possible number of sensing modalities and processing steps. Given their precision and ease of implementation, accelerometers were chosen. Triaxial accelerometers capture both static and dynamic linear acceleration in three dimensions. Their primary frame of reference (FOR) is the Earth's static gravitational field. However, accelerometers also sense dynamic acceleration applied to them. Thus, a static accelerometer aligned with gravity experiences 1g on the axis parallel to gravity and 0g elsewhere. In contrast, a dynamic accelerometer experiences both gravity and acceleration dynamically applied to it. In the most general sense, accelerometers capture the acceleration of the local inertial FOR.

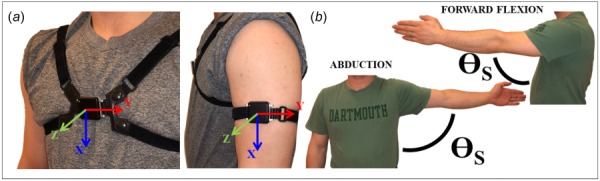

To further minimize computational complexity, each accelerometer signal (Ai) can be converted to a single three-dimensional vector (i.e., A1 = [X1, Y1, Z1] and A2 = [X2, Y2, Z2]). Thus, two accelerometers generate two 3D vectors. As with other vector mathematics, an angle can then be computed between the local coordinate system of each acceleration vector and the global gravitational coordinate system. This extrapolates to multiple accelerometers quantifying unique angles with respect to gravity for each accelerometer. Given the same gravitational FOR, comparing two accelerometers yields a single angle difference. Furthermore, if each accelerometer is rigidly affixed to a distinct bony segment, a single joint angle can be computed. Specifically for the shoulder, when two accelerometers are rigidly attached to the sternum and humerus, respectively, a shoulder joint angle can be computed (Fig. 1(a); sternum: approximately in line with the fourth costal notch, humerus: deltoid tuberosity). However, in contrast to the anatomic restrictions of ginglymoid joints such as the knee, the shoulder permits large ROM in multiple planes. With this additional flexibility, individuals can move their arms in nearly infinite combinations of sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes. However, an inherent limitation of only using accelerometers with one FOR (i.e., gravity) is an inability to distinguish between equal shoulder elevations in different planes of elevation and/or axial rotations (Fig. 1(b)). The proposed system is, therefore, unable to determine plane of elevation or axial rotation without additional inputs (e.g., gyroscope). Nevertheless, comparing the relative motion between two IMUs attached to the upper body as noted allows computation of shoulder elevation.

Fig. 1.

Example instrumentation including (a) IMU donning locations on the sternum and humerus with associated coordinate systems and (b) angle equivalency between forward flexion and abduction

One inherent potential error source using this method is added dynamic acceleration via human movement. Unfortunately, because only accelerometers are used, accounting for these dynamics is impossible without additional inputs (e.g., bony segment length and gyroscope magnitudes). As such, the shoulder elevation computed by the proposed method is true shoulder elevation plus error from dynamic accelerations (θIMU = θTrue + θDyn). However, this error source is unlikely to impact the final shoulder elevation calculations due to the low acceleration of upper extremity movements [24–26]. For example, combining typical shoulder angular velocities during ADL and humeral lengths (ω = 0.52 rad/s, r = 0.30 m, and |a| = rω2) gives added accelerations of 0.08 m/s2 (0.008g) resulting in 0.8% error [27,28]. Moreover, digital filtration methods (described in section Methods: Validation) employed in the final algorithm ensure that unrealistically high accelerations (e.g., sensor collision with door frame) are removed from the final calculations.

Methods: Validation.

To assess the accuracy of the proposed method, validation via comparison to optical MOCAP was completed in a laboratory setting (OptiTrack Motive Body 1.10, NaturalPoint, Inc., Corvallis, OR). Six S250e cameras were temporally synchronized and calibrated per the manufacturer's specifications. Retroreflective markers were placed on appropriate bony landmarks on the upper body (Fig. 2). IMUs were simultaneously donned as described previously. Three-dimensional position data from retroreflective markers and acceleration data from IMUs were simultaneously captured at 128 Hz during a series of prescribed movements (forward flexion, abduction, scaption, and internal/external rotation). Two healthy subjects with no known shoulder dysfunction participated in the validation experiments. Each subject performed three repetitions of each movement at a self-selected comfortable speed and the best repetition of each movement (defined as the trial with the least amount of optical MOCAP marker loss) was utilized for final analysis.

Fig. 2.

Upper extremity marker set utilized during validation experiments comparing IMU-based ROM and MOCAP-based ROM methods

Validation analyses included calculating shoulder elevation by both MOCAP and IMU methods. Shoulder elevation was computed by the MOCAP system (θMOCAP) via calculation of the relative joint angle quaternion between the humerus and the torso during each movement. Quaternions were then converted per ISB recommendations to shoulder elevation, plane of elevation, and axial rotation [8]. Simultaneously, shoulder elevation was computed from accelerometer data via matlab as follows (matlab R2016a, Mathworks, Natick, MA). IMU data collection began immediately following removal from charging docks and continued after IMU doffing. Thus, there were periods with unusable data after removal from charging docks/prior to IMU donning and after IMU doffing/prior to redocking. These two time periods were removed automatically by locating the first and last time point when IMUs were correctly placed. This was defined as the first and last time point when IMUs were primarily aligned with gravity (i.e., ±1g) and the subject was stationary (Fig. 3(a)). There were potentially additional time periods where subjects removed the IMUs in the middle of data collection (i.e., bathing and swimming). These time periods were automatically detected via variance analysis and removed. Specifically, any period of time longer than 5 s that fell below a preset acceleration variability threshold indicating IMU removal (<0.5g) was located and removed (Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 3.

Example data removal including (a) prior to initial IMU donning via magnitude analysis and (b) data between initial donning and final doffing via variability analysis

Following data removal, all three axes on both IMUs (sternum/humerus, see Fig. 1 for coordinate system definitions) were filtered in the forward and backward directions using a fifth-order low pass Butterworth filter (fcutoff = 5 Hz) [29,30]. Following filtration, both sets of triaxial IMU data were converted to independent acceleration vectors (AHumerus and ASternum). Next, a rotation matrix (RInitial) was computed between AHumerus and ASternum during a period of time when the subject was stationary. RInitial was then used to account for both anatomical offset between the humerus and sternum and any sensor misalignment. Specifically, RInitial was used to rotate AHumerus to the sternum coordinate system and generate AHumerus_in_Sternum. AHumerus_in_Sternum and ASternum were then compared to calculate shoulder elevation throughout the entire movement (θIMU). Finally, θMOCAP and θIMU were compared and the error between the two methods was calculated for all time during each movement (θError). θError was then averaged over each movement. Average and maximum error are reported in addition to cross-plots of θMOCAP versus θIMU to assess how well the two methods were matched.

Methods: Daily Workflow Development.

In addition to theoretical analyses and in-lab validation, a daily workflow was created to facilitate daily data capture from prospective study subjects (Fig. 4). In practice, subjects awoke, removed the IMUs from the charging dock, and donned them. Sensors then automatically synced via meshed local area network. In this scheme, both IMUs send a “sync packet” allowing comparison of their own clock against the other IMU's clock. This process allowed both IMUs to continuously check and reset any asynchronization.

Fig. 4.

Data processing workflow including (1) raw accelerometer signal input, (2) processing accelerometer signals (bony segment differentiation, low pass filtration, offsetting anatomical/sensor misalignment, and distal to proximal coordinate transformation), (3) continuous shoulder elevation calculation, (4) daily metric calculation (average, maximum bin > 10×, maximum elevation, binned movement rate, binned percentage), (5) weekly metric averages, and (6) total subject averages

Following synchronization, data were continuously captured for a desired duration (8–12 h/day) and stored locally on each respective IMU. On-board 16 GB MicroSD cards and high capacity LiPo batteries allowed daily captures up to 18 h for 60 days. At the end of each day, subjects doffed both IMUs and redocked them, terminating the daily capture. This process was repeated for the duration of the study. At the end of study participation, sensors were returned to the study team for analyses. Data were downloaded and processed offline as described earlier in Methods: Validation. Appropriate figures and datasets were then exported as needed.

Methods: Prospective Study.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and a prospective analysis was conducted on 10 healthy individuals (4M/6F, 69 ± 20 years) with no known shoulder dysfunction. Subjects were captured from the local retirement community via mass email advertisement with inclusion criterion of age > 21, an ability to achieve full forward flexion (>150 deg), extension (>40 deg), abduction (>130 deg), external rotation (>90 deg), and internal rotation (>60 deg) [10]. Following consent and enrollment, handedness was captured for all subjects utilizing the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory to determine on what arm IMUs would be donned [31].

All subjects participated in a sensor use tutorial. The tutorial lasted approximately 30 min and included information on plugging charging docks into a standard 60 Hz/120 V AC wall outlet, placing IMUs on charging docks, donning IMUs (where/how on each bony segment each IMU was worn), and duration of use. Subjects were allowed to ask questions throughout the tutorial and were given an instruction manual with contact information in case questions arose posttutorial.

Subjects wore two IMUs as noted previously (APDM, Inc., Portland, OR) on their dominant arm (determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Questionnaire) [31] and sternum for 1 week with no clinical interventions (e.g., injection or physical therapy) offered during this period. IMUs were then donned/doffed as instructed upon waking/prior to sleeping, respectively, each day for the duration of the study. Each day's data from both sensors were processed as previously noted. From each day's shoulder elevation data, elevation was binned in 0.5 s and 5 deg increments (e.g., 0–5 deg and 5–10 deg). The average elevation during each time bin was computed and the corresponding angle bin count was incremented. For example, if average elevation in a time bin was 23 deg, the 20–25 deg angle bin was incremented. The total bin count was converted to a percentage. Other major outcome metrics computed were daily average shoulder elevation, daily maximum shoulder elevation, and maximum elevation bin with >10 occurrences. Daily metrics were then averaged weekly and weekly metrics were averaged across subjects. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) were also captured including pain scores, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeon's (ASES) survey scores, and Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-10 mental and physical component summary scores [32,33]. Clinical goniometric ROM was also captured including flexion, abduction, and internal/external rotation.

Results

Results: Validation.

Cross-plots are shown in Fig. 5 comparing shoulder elevation calculated by MOCAP (θMOCAP) and the proposed IMU-based method (θIMU) for both validation subjects combined for each movement (flexion, abduction, scaption, and internal/external rotation). Also displayed is a cross plot comparing θMOCAP and θIMU for both validation subjects during all movements (Fig. 5(e)). Velocity profiles were single peaked and reached typical maximum magnitudes compared to literature-based values (ω = 41 ± 4 deg/s, 38 ± 11 deg/s, 51 ± 15 deg/s, and 5 ± 1 deg/s for respective movements) [28]. θIMU was well matched with θMOCAP during all movements (R2 = 0.96, 0.96, 0.98, and 0.90 for respective motions) with low average error (Ē = 1.7 deg, 2.9 deg, −0.3 deg, and 0.4 deg for respective motions), and low maximum error that was generally proportionate to the overall magnitude of the movement (EMAX = 2.1 deg, 3.3 deg, 2.0 deg, and 1.5 deg for respective movements). More critically, with all movements analyzed together, θIMU remained well matched with θMOCAP (R2 = 0.98) with low average (Ē = 1.4 deg) and maximum error (EMAX = 2.2 ± 0.8 deg).

Fig. 5.

Validation results comparing shoulder elevation calculated by MOCAP versus shoulder elevation calculated by IMU for two subjects during a variety of movements including (a) forward flexion, (b) abduction, (c) scaption, (d) internal/external rotation, and (e) all movements

Results: Prospective Study.

Ten healthy individuals completed the 7-day study to continuously capture shoulder elevation. Subject demographics are displayed in Table 1. Four males and six females were enrolled. Nine were right handed and subsequently wore IMUs on their right arm. All subjects wore IMUs for 7 days for an average of 13.5 ± 2.9 h/day. Subjects were 69 ± 20 years on average; however, no significant connection was found between age and any outcome metric discussed herein. PROMs and clinical ROM are displayed in Table 2. All PROMs were normal including low pain scores (2 ± 1) and high PROMIS-10 physical component summary, PROMIS-10 mental component summary, and ASES scores (56.7 ± 6.6, 57.4 ± 7.0, and 92.3 ± 8.6, respectively). Similarly, all clinical ROM metrics were normal with flexion of 158 ± 19 deg, abduction of 164 ± 16 deg, and external rotation of 73 ± 20 deg. Internal rotation achieved by all subjects was well matched with the literature [34].

Table 1.

Subject demographics

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender | 4M, 6F |

| Age (years) | 69 ± 20 |

| Handedness | 9R, 1 L |

| Sensor side | 9R, 1 L |

| Days | 7 ± 0 |

| Hours/day | 13.5 ± 2.9 |

Table 2.

Patient reported outcome measures and clinical goniometric ROM. Pain is listed as median ± median absolute deviation; PROMIS P, PROMIS M, and ASES are listed as mean ± SD

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Pain | 2 ± 1 |

| PROMIS P | 56.7 ± 6.6 |

| PROMIS M | 57.4 ± 7.0 |

| ASES | 92.3 ± 8.6 |

| Forward flexion (deg) | 158 ± 19 |

| Abduction (deg) | 164 ± 16 |

| External rotation (deg) | 73 ± 20 |

Daily IMU-based outcome metrics (average elevation, maximum bin >10 movements, maximum elevation) are displayed in Fig. 6. Daily average shoulder elevation was 40 ± 6 deg. Maximum shoulder elevation greater than ten movements was 148 ± 14 deg. Daily maximum shoulder elevation was 169 ± 8 deg. Shown in Fig. 7 is the binned shoulder elevation data as a percentage. Binned data were normally distributed with the highest percentage spent in the 25–30 deg bin (9.7 ± 1.8%). Combining bins in to 45 deg increments, subjects spent 65.6 ± 3.0%, 30.6 ± 2.0%, 3.5 ± 0.2%, and 0.3 ± 0.04% of the day in the 0–45 deg, 45–90 deg, 90–135 deg, and 135–180 deg bins, respectively. Combining bins further to 90 deg increments, 96.2% of time was spent under 90 deg of elevation.

Fig. 6.

Daily shoulder elevation metrics for all subjects including average shoulder elevation, maximum binned shoulder elevation > 10 occurrences, and maximum shoulder elevation

Fig. 7.

Binned shoulder elevation data in 5 deg increments with movement percentage average as bars and movement percent average ± one standard deviation as dashed lines

Discussion

Prior studies on shoulder ROM in both patients and healthy individuals have traditionally captured data in well-controlled settings during idealized movements (e.g., passive ROM via goniometry). These simplified methods may not adequately capture the shoulder ROM patients utilize in their home environment.

Discussion: Validation.

We leveraged the relative motion between two accelerometers rigidly affixed to the sternum and upper extremity to quantify shoulder elevation, which is critical for upper extremity function during many daily activities [9]. Validation showed that the proposed IMU-based ROM measurement method was well matched to optical MOCAP (R2 = 0.98) with low error (Ē = 1.4 deg) during a series of prescribed upper extremity movements. Despite the success, there are several potential error sources. Notably, as the subject reaches the highest amplitude of the movement, slack develops in the strap attached to the sternal sensor causing the IMU to lose fixation with the sternum. This loss of fixation artificially reduces the calculated shoulder elevation angle and simultaneously increases error. A second error source discussed previously (see Methods) is added accelerations not currently accounted for by using only accelerometers. Critically, during high amplitude elevation motions in the validation experiments, we found movement speeds of 0.76 rad/s on average. With this velocity and a humeral length of approximately 0.3 m, the added accelerations were 0.173 m/s2 (0.018g) on average, which corresponded to 1.8% additional error from unaccounted dynamic acceleration. Although these error sources are real and recognized, the method is clinically comparable to currently utilized methods for measuring shoulder ROM with the added benefit of allowing data capture outside of overly idealized clinic/laboratory environments [35,36].

Discussion: Maximum Elevation.

A prospective analysis of ten healthy individuals with no known shoulder dysfunction using the validated IMU-based method for capturing shoulder elevation was completed. Prior to data capture, we hypothesized that subjects in our study would exhibit similar maximal shoulder elevation levels (>150 deg) to the previously established values from in-lab experiments [9,10,21–23]. The maximum elevation calculated for this cohort by our validated method was on average 169 deg, supporting our first hypothesis. This likely indicates that the cohort assessed in our study is capable of accomplishing nearly all ADL without accommodations. More critically, the proposed method is capable of capturing similar information to that obtained in the clinic with the added benefit of capturing data from patients in their home-environment.

Discussion: Movement Percentage.

A second hypothesis developed prior to data collection based on the work of Coley et al. was that individuals would spend the vast majority of their time with their shoulders elevated under 90 deg [20]. Utilizing our validated method, we discovered that this cohort did in fact spend the vast majority of time (∼97%) under 90 deg of shoulder elevation, supporting our second hypothesis. More specifically, while individuals captured in our study were healthy and capable of achieving high maximal shoulder ROM as noted previously, they were seldom required to do so. It is likely that moving above 90 deg of elevation occurs infrequently each day (e.g., reach overhead to grab a coffee cup from a cabinet). This may reflect that our living environments are arranged for the majority of our time to be spent with our arms below 90 deg of elevation. Perhaps more critically, the proposed method is capable of capturing richer ROM data than the currently accepted gold standards.

Discussion: Limitations and Future Work.

Although this work highlights shortcomings of currently implemented clinical shoulder ROM measurement methods and the benefits of IMU-based methods, there are many questions that remain unknown. Notably, one limitation of the current study is only sagittal plane thoracohumeral motion or shoulder elevation was captured. However, the other planes of shoulder motion (frontal: plane of elevation, transverse: internal/external rotation) may be clinically relevant in specific pathologies. Accordingly, future work should include efforts expanding the capabilities of the current system to include other planes of motion. This has been attempted in other joints by more effectively computing the axes of rotation, adding additional sensing modalities beyond accelerometers (i.e., gyroscope, magnetometer), and precisely quantifying sensor locations relative to joint centers of rotation [37–39]. A second limitation with the current approach is only capturing the dominant arm of subjects in this study. However, it is well known that there are many upper extremity ADLs that are performed bilaterally. Moreover, in certain patient populations, this ability is likely reduced. Accordingly, in future iterations, it would be ideal to place IMUs on both humeri to establish both the independent and the bilateral function of both upper extremities in the populations of interest.

Conclusion

We successfully developed a method for continuously capturing shoulder ROM out of well-controlled environments. This method is equal to current ROM measurement methods (e.g., optical MOCAP) with the added benefit of portability. Implementing the proposed method showed that data management and long-duration computations were feasible. Moreover, the results can be utilized to establish “norms” for healthy individuals. As such, the results of this study may be utilized as a baseline for future studies involving patients with a variety of shoulder pathologies before and after surgical intervention. Using it in this manner will facilitate continuous feedback to clinicians on the joint status of their patients. This will allow further understanding of typical and atypical pre- and postsurgical biomechanical performance.

Contributor Information

Ryan M. Chapman, Thayer School of Engineering, , Dartmouth College, , 14 Engineering Drive, , Hanover, NH 03755 , e-mail: rmchapman.th@dartmouth.edu

Michael T. Torchia, Department of Orthopaedics, , Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, , Lebanon, NH 03766

John-Erik Bell, Department of Orthopaedics, , Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, , Lebanon, NH 03766.

Douglas W. Van Citters, Thayer School of Engineering, , Dartmouth College, , Hanover, NH 03755

Funding Data

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001086, Funder ID. 10.13039/100006108).

References

- [1]. Norris, T. R. , and Iannotti, J. P. , 2002, “Functional Outcome After Shoulder Arthroplasty for Primary Osteoarthritis: A Multicenter Study,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 11(2), pp. 130–135. 10.1067/mse.2002.121146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Hawkins, R. , Bell, R. , and Jallay, B. , 1989, “Total Shoulder Arthroplasty,” Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 242(1), pp. 188–194. 10.1097/00003086-198905000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Sirveaux, F. , Favard, L. , Oudet, D. , Huquet, D. , Walch, G. , and Molé, D. , 2004, “Grammont Inverted Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in the Treatment of Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis With Massive Rupture of the Cuff,” Bone Jt. J., 86(3), pp. 388–395. 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Ilfeld, B. M. , Wright, T. W. , Enneking, F. K. , and Morey, T. E. , 2005, “Joint Range of Motion After Total Shoulder Arthroplasty With and Without a Continuous Interscalene Nerve Block: A Retrospective, Case-Control Study,” Reg. Anesth. Pain Med., 30(5), pp. 429–433. 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Brown, D. D. , and Friedman, R. J. , 1998, “Postoperative Rehabilitation Following Total Shoulder Arthroplasty,” Orth. Clin. North Am., 29(3), pp. 535–547. 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70027-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Gore, D. R. , Murray, M. P. , Sepic, S. B. , and Gardner, G. M. , 1986, “Shoulder-Muscle Strength and Range of Motion Following Surgical Repair of Full-Thickness Rotator-Cuff Tears,” JBJS, 68(2), pp. 266–272. 10.2106/00004623-198668020-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Ide, J. , and Takagi, K. , 2004, “Early and Long-Term Results of Arthroscopic Treatment for Shoulder Stiffness,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 13(2), pp. 174–179. 10.1016/j.jse.2003.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Wu, G. , Van der Helm, F. C. T. , Veeger, H. E. J. , Makhsous, M. , Van Roy, P. , Anglin, C. , Nagels, J. , Karduna, A. R. , McQuade, K. , Wang, X. , Werner, F. W. , and Buchholz, B. , 2005, “ISB Recommendation on Definitions of Joint Coordinate Systems of Various Joints for the Reporting of Human Joint Motion—Part II: Shoulder, Elbow, Wrist and Hand,” J. Biomech., 38(5), pp. 981–992. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Magermans, D. J. , Chadwick, E. K. , Veeger, H. E. , and van der Helm, F. C. , 2005, “Requirements for Upper Extremity Motions During Activities of Daily Living,” Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon), 20(6), pp. 591–599. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Boone, D. , and Azen, S. , 1979, “Normal Range of Motion of Joints in Male Subjects,” JBJS, 61(5), pp. 756–759. 10.2106/00004623-197961050-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Boardman, N. D., 3rd , Cofield, R. H. , Bengtson, K. A. , Little, R. , Jones, M. C. , and Rowland, C. M. , 2001, “Rehabilitation After Total Shoulder Arthroplasty,” J Arthroplasty, 16(4), pp. 483–486. 10.1054/arth.2001.23623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Fisher, E. S. , Bell, J.-E. , Tomek, I. M. , Esty, A. R. , and Goodman, D. C. , 2010, “Trends and Regional Variation in Hip, Knee, and Shoulder Replacement,” Dartmouth Atlas Surg. Rep., 1(1), pp. 1–24.http://archive.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Joint_Replacement_0410.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Jackson, M. , Michaud, B. , Tetreault, P. , and Begon, M. , 2012, “Improvements in Measuring Shoulder Joint Kinematics,” J. Biomech., 45(12), pp. 2180–2183. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Riddle, D. L. , Rothstein, J. M. , and Lamb, R. L. , 1986, “Goniometric Reliability in a Clinical Setting: Shoulder Measurements,” Phys. Ther., 67(5), pp. 668–673. 10.1093/ptj/67.5.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Windolf, M. , Gotzen, N. , and Morlock, M. , 2008, “Systematic Accuracy and Precision Analysis of Video Motion Capturing Systems—Exemplified on the Vicon-460 System,” J. Biomech., 41(12), pp. 2776–2780. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Hassan, E. A. , Jenkyn, T. R. , and Dunning, C. E. , 2007, “Direct Comparison of Kinematic Data Collected Using an Electromagnetic Tracking System Versus a Digital Optical System,” J. Biomech., 40(4), pp. 930–935. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Braun, S. , Millett, P. J. , Yongpravat, C. , Pault, J. D. , Anstett, T. , Torry, M. R. , and Giphart, J. E. , 2010, “Biomechanical Evaluation of Shear Force Vectors Leading to Injury of the Biceps Reflection Pulley: A Biplane Fluoroscopy Study on Cadaveric Shoulders,” Am. J. Sports Med., 38(5), pp. 1015–1024. 10.1177/0363546509355142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. El-Gohary, M. , and McNames, J. , 2012, “Shoulder and Elbow Joint Angle Tracking With Inertial Sensors,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 59(9), pp. 2635–2641. 10.1109/TBME.2012.2208750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Luinge, H. J. , Veltink, P. H. , and Baten, C. T. , 2007, “Ambulatory Measurement of Arm Orientation,” J. Biomech., 40(1), pp. 78–85. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Coley, B. , Jolles, B. M. , Farron, A. , and Aminian, K. , 2008, “Arm Position During Daily Activity,” Gait Posture, 28(4), pp. 581–587. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Barnes, C. J. , Van Steyn, S. J. , and Fischer, R. A. , 2001, “The Effects of Age, Sex, and Shoulder Dominance on Range of Motion of the Shoulder,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 10(3), pp. 242–246. 10.1067/mse.2001.115270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Soucie, J. M. , Wang, C. , Forsyth, A. , Funk, S. , Denny, M. , Roach, K. E. , and Boone, D. , 2011, “Range of Motion Measurements: Reference Values and a Database for Comparison Studies,” Haemophilia, 17(3), pp. 500–507. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Bassey, E. J. , Morgan, K. , Dallosso, H. M. , and Ebrahim, S. B. J. , 1989, “Flexibility of the Shoulder Joint Measured as Range of Abduction in a Large Representative Sample of Men and Women Over 65 Years of Age,” Eur. J. Appl. Phys., 58(4), pp. 353–360. 10.1007/BF00643509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. de los Reyes-Guzman, A. , Dimbwadyo-Terrer, I. , Trincado-Alonso, F. , Monasterio-Huelin, F. , Torricelli, D. , and Gil-Agudo, A. , 2014, “Quantitative Assessment Based on Kinematic Measures of Functional Impairments During Upper Extremity Movements: A Review,” Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon), 29(7), pp. 719–727. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Garland, S. J. , Stevenson, T. J. , and Ivanova, T. , 1997, “Postural Responses to Unilateral Arm Perturbation in Young, Elderly, and Hemiplegic Subjects,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab., 78(10), pp. 1072–1077. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Rogers, M. E. , Fernandez, J. E. , and Bohlken, R. M. , 2001, “Training to Reduce Postural Sway and Increase Functional Reach in the Elderly,” Occup. Rehab., 11(4), pp. 291–298. 10.1023/A:1013300725964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Mall, G. , Hubig, M. , Büttner, A. , Kuznik, J. , Penning, R. , and Graw, M. , 2001, “Sex Determination and Estimation of Stature From the Long Bones of the Arm,” Sci. Int., 117(1–2), pp. 23–30. 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00445-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Melton, C. , Mullineaux, D. , Mattacola, C. , Mair, S. , and Uhl, T. , 2011, “Reliability of Video Motion-Analysis Systems to Measure Amplitude and Velocity of Shoulder Elevation,” J. Sport Rehab., 20(4), pp. 393–405. 10.1123/jsr.20.4.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Winter, D. A. , 1982, “Camera Speeds for Normal and Pathological Gait Analyses,” Med. Biol. Eng. Comp., 20(4), pp. 408–412. 10.1007/BF02442398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Pezzack, J. , Norman, R. , and Winter, D. , 1977, “An Assessment of Derivative Determining Techniques Used for Motion Analysis,” J. Biomech., 10(5–6), pp. 377–382. 10.1016/0021-9290(77)90010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Oldfield, R. C. , 1971, “The Assessment and Analysis of Handedness: The Edinburgh Inventory,” Neuropsychologia, 9(1), pp. 97–113. 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Michener, L. A. , McClure, P. W. , and Sennett, B. J. , 2002, “American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form, Patient Self-Report Section: Reliability, Validity, and Responsiveness,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 11(6), pp. 587–594. 10.1067/mse.2002.127096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Hung, M. , Baumhauer, J. F. , Latt, L. D. , Saltzman, C. L. , SooHoo, N. F. , and Hunt, K. J. , 2013, “Validation of PROMIS® Physical Function Computerized Adaptive Tests for Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Outcome Research,” Orth. Rel. Res., 471(11), pp. 3466–3474. 10.1007/s11999-013-3097-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Yun, Y.-H. , Jeong, B.-J. , Seo, M.-J. , and Shin, S.-J. , 2015, “Simple Method of Evaluating the Range of Shoulder Motion Using Body Parts,” Clin. Shoulder Elbow, 18(1), pp. 13–20. 10.5397/cise.2015.18.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Lowe, B. D. , 2004, “Accuracy and Validity of Observational Estimates of Shoulder and Elbow Posture,” Appl. Ergon., 35(2), pp. 159–171. 10.1016/j.apergo.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Hayes, K. , Walton, J. R. , Szomar, Z. L. , and Murrell, G. A. , 2001, “Reliability of Five Methods for Assessing Shoulder Range of Motion,” Aus. J. Phys., 47(4), pp. 289–294. 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60274-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Favre, J. , Jolles, B. M. , Aissaoui, R. , and Aminian, K. , 2008, “Ambulatory Measurement of 3D Knee Joint Angle,” J. Biomech., 41(5), pp. 1029–1035. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Favre, J. , Aissaoui, R. , Jolles, B. M. , de Guise, J. A. , and Aminian, K. , 2009, “Functional Calibration Procedure for 3D Knee Joint Angle Description Using Inertial Sensors,” J. Biomech., 42(14), pp. 2330–2335. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Kawano, K. , Kobashi, S. , Yagi, M. , Kondo, K. , Yoshiya, S. , and Hata, Y. , 2007, “Analyzing 3D Knee Kinematics Using Accelerometers, Gyroscopes and Magnetometers,” IEEE Int. Conf., 1(1), pp. 1–6. 10.1109/SYSOSE.2007.4304332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]