Short abstract

Diarrheal disease is a severe global health problem. It is estimated that secretory diarrhea causes 2.5 million deaths annually among children under the age of five in the developing world. A critical barrier in treating diarrheal disease is lack of easy-to-use effective treatments. While antibiotics may shorten the length and severity of diarrhea, oral rehydration remains the primary approach in managing secretory diarrhea. Existing treatments mostly depend on reconstituting medicines with water that is often contaminated which can be an unresolved problem in the developing world. Standard treatments for secretory diarrhea also include drugs that decrease intestinal motility. This approach is less than ideal because in cases where infection is the cause, this can increase the incidence of bacterial translocation and the potential for sepsis. Our goal is to develop a safe, effective, easy-to-use, and inexpensive treatment to reduce fluid loss in secretory diarrhea. We have developed Rx100, which is a metabolically stable analog of lysophosphatidic acid. We tested the hypothesis that Rx100, similarly to lysophosphatidic acid, inhibits the activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator Cl− channel and also reduces barrier permeability resulting in the decrease of fluid loss in multiple etiologies of secretory diarrhea. Here we have established the bioavailability and efficacy of Rx100 in cholera toxin-induced secretory diarrhea models. We have demonstrated the feasibility of Rx100 as an effective treatment for Citrobacter rodentium infection-induced secretory diarrhea. Using both the open- and closed-loop mouse models, we have optimized the dosing regimen and time line of delivery for Rx100 via oral and parenteral delivery.

Impact statement

A critical barrier in treating diarrheal disease is easy-to-use effective treatments. Rx100 is a first in class, novel small molecule that has shown efficacy after both subcutaneous and oral administration in a mouse cholera-toxin- and Citrobacter rodentium infection-induced diarrhea models. Our findings indicate that Rx100 a metabolically stable analog of the lipid mediator lysophosphatidic acid blocks activation of CFTR-mediated secretion responsible for fluid discharge in secretory diarrhea. Rx100 represents a new treatment modality which does not directly block CFTR but attenuates its activation by bacterial toxins. Our results provide proof-of-principle that Rx100 can be developed for use as an effective oral or injectable easy-to-use drug for secretory diarrhea which could significantly improve care by eliminating the need for severely ill patients to regularly consume large quantities of oral rehydration therapies and offering options for pediatric patients.

Keywords: Secretory diarrhea, cholera toxin, Citrobacter rodentium, lysophosphatidic acid, lysophosphatidic acid receptor, oral rehydration therapy, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, Rx100, G-protein-coupled receptors

Introduction

Secretory diarrhea (SED) is a major cause of death in the worldwide and is a major health challenge in developing countries that experience epidemics of select enterotoxin-producing bacteria. It affects individuals of all ages.1–3 In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified acute watery diarrhea/cholera an emergency with over 80,000 cases (suspected and confirmed) in just two countries (Somalia and Yemen) from January–April 2017.4,5 SED can be caused by infection of the gut by the enterotoxin-producing bacteria primarily Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. These enterotoxins bind to receptors on the apical surface of crypt cells and activate the adenylate cyclase located on the basolateral membrane. Increased production of cAMP leads to the activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel that is responsible for an osmotic gradient which moves water and electrolytes mostly via paracellular transport due to the impairment of the gut barrier function6–8 that collectively are the hallmarks of SED.8,9

The current standard therapy for SED is oral rehydration therapy (ORT) which involves fluid replacement using a mixture of water, salts, and glucose in specific proportions. ORT is useful and may reduce diarrhea mortality by up to 93% in children under the age of 5.10 However, ORT is primarily a supportive care that has many serious limitations: (1) In many cholera outbreaks, clean water and storage vessels are not readily available for use in preparing oral rehydration solutions (ORSs) resulting in bacterial contamination of ORS.11 (2) According to the WHO fluid replacement recommendations, in cases of just mild dehydration, a child five years of age may require up to 2.2 L of ORT in the first 4 h. However, this amount of clean water is rarely available in areas of developing countries stricken by diarrhea epidemic.12 (3) In addition, for severe dehydration it is recommended that IV fluids and sometimes antibiotics be given in addition to ORT which is even more rarely available primitive rural settings. (4) Vomiting is often associated with SED which curtails the effectiveness of ORT.13 In addition to ORT, current therapies include antimotility, antispasmodic drugs. These therapies also have many limitations as they tend to reduce the clearance of infectious agents from the gut lumen that if coupled with barrier damage can lead to the development of systemic infection. A product, Fulyzaq™ (crofelemer), was recently approved by FDA for the treatment of diarrhea caused by antiretroviral therapy.14–16

The involvement of CFTR and the intestinal Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) in SED is supported by numerous studies.8,9,17,18 There is evidence that the CFTR is the main pathway involved in SED.18 A recent study using a V. cholerae infection model in adult mice confirmed the CFTR as a major host factor determining intestinal fluid secretion in cholera.19 Fluid loss in SED is caused by active transepithelial Cl− secretion creating the electrochemical force and the osmotic driving force for massive paracellular and transcellular Na+ and water efflux into the lumen.20 CTX has been shown to disrupt the tight junctions of the intestinal epithelial barrier21 and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) have been shown to enhance the junctional complexes.22 Because CFTR is expressed at the luminal membrane of crypt enterocytes, it represents a unique target for the development of drug candidates for the control of SED.

In an attempt to develop anti-secretory drug therapy for cholera, several classes of CFTR inhibitors have been identified and demonstrated to effectively reduce CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion in both rats and mice.6,7,23 However, CFTR has very important homeostatic functions in the lung and other secretory epithelial cells (sweat and salivary glands) that limit the applicability of agents that cause systemic inactivation of CFTR leading to cystic-fibrosis-like symptoms. Thus, as opposed to systemic blockade of CFTR, a targeted inactivation of CFTR on the luminal surface of GI enterocytes is required.

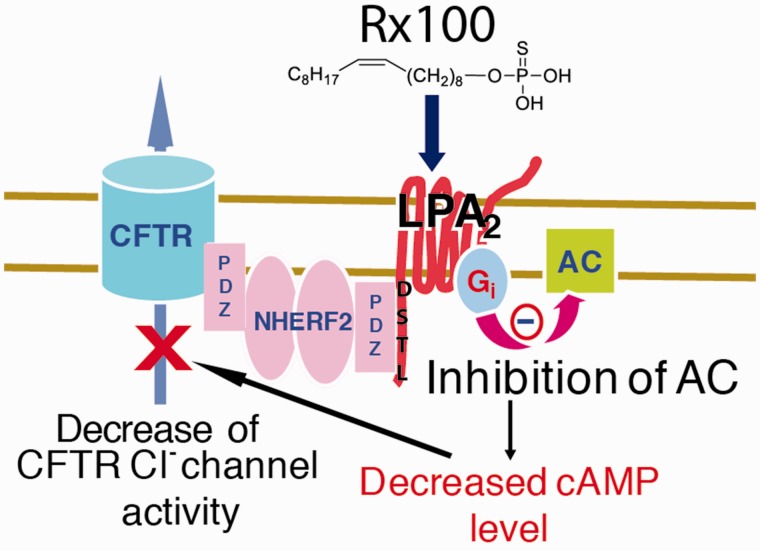

The growth factor-like lipid mediator LPA plays an important regulatory role in the integrity and regeneration of the gastrointestinal tract. LPA is both a lipid mediator and an intermediate in phospholipid absorption/biosynthesis.24 LPA acts through six GPCR.20,25–27 GI enterocytes abundantly expresses LPA2.28–31 We have previously determined that the (LPA) receptor subtype 2 (LPA2) and CFTR are physically associated via the Na-H exchange response factor 2 (NHERF2).32–34 This clusters the LPA2 receptor, and CFTR into a macromolecular complex at the apical plasma membrane of intestinal epithelial cells (Figure 1).32 LPA via the LPA2 GPCR that is coupled to Gi heteromeric G-protein, when in physical complex with CFTR, inhibits this Cl− channel by reducing cAMP production in the membrane microdomain.32 We have demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of LPA on CFTR-dependent fluid secretion in the ileal loop is absent in LPA2 knockout mice demonstrating the essential role of LPA2 in this pathway.32,33

Figure 1.

Schematic model of Rx100 and mechanism of action. Upon stimulation by agonists like Rx100 or LPA, the LPA2 GPCR and CFTR become physically associated via the NHERF2 scaffold protein, which clusters the LPA2 receptor, and CFTR into a macromolecular complex at the apical plasma membrane of intestinal epithelial cells in the immediate vicinity of adenylyl cyclase. The localized inhibition of cAMP production by the heterotrimeric Gi protein diminishes the opening of CFTR and reduces Cl− flux into the intestinal lumen. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

LPA has short half-life in blood estimated to be ∼9 min;35 thus, it is unsuitable for pharmaceutical applications. We developed an LPA “mimic,” octadecyl thiophosphate (18:1δ9, aka. Rx100) that stimulates all LPA GPCR with EC50 values in the nanomolar range36 and with improved metabolic stability in vitro. Agents that inhibit the CFTR Cl− channel tend to reduce CFTR-dependent diarrhea. Thus, our previous reports establishing the ligand-activation of the macromolecular complex of LPA2—NHERF2—CFTR is the foundation of functional inhibition between LPA2 signaling and CFTR-mediated Cl− efflux responsible for fluid loss from the GI system. Of note, LPA also stimulates intestinal Na+ and fluid absorption by activating NHE3 through an LPA5-mediated signaling cascade which increases Na+ and fluid absorption that counteracts toxin-activated secretion.37

Here we provide pharmacokinetic evidence for the drug-like pharmacokinetic properties and oral bioavailability underlying the high efficacy of Rx100 in rodents. We provide evidence for the anti-diarrheal actions of Rx100 in ileal open- and closed loop murine models of the SED disease. We show that oral administration of Rx100 significantly inhibited CTX-induced CFTR-mediated SED and SED induced by C. rodentium in mice. LPA has been shown previously to strengthen tight- and adherens-junctions between enterocytes and enhance the intestinal epithelial barrier.38 We provide evidence that Rx100 increases trans-epithelial resistance (TER), reduces inulin permeability of Caco-2 cell monolayers, and maintains tight junction integrity following CTX exposure. Rx100 due to its simple structure and ease of manufacture coupled with its multiple cytoprotective actions in the gastrointestinal system has the potential to overcome many limitations of existing therapies in both industrialized and developing countries in the treatment of SED.39,40

Materials and methods

Reagents

Rx100 (Lysine salt) was synthesized under cGMP conditions by Johnson Matthey Pharma Services. Rx100 was prepared in 10 mM histidine and sterile filtered; 10 mM histidine was used for vehicle. CTX was obtained from Sigma and was reconstituted in HyClone water for injection (WFI) quality water (Fisher Scientific). Citrobacter rodentium (strain DBS100) was purchased from ATCC. Bicarbonate (7% W/V) buffer was used as the vehicle and diluents for the CTX studies.

Animals

All animal studies were conducted under protocols reviewed and approved by The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Cannulated male Wistar Rats sourced from Charles River (∼200 g) were used for pharmacokinetic studies. C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Laboratories were used for the mouse pharmacokinetic and infection studies. CD1 mice (Jackson Labs) were used for the CTX studies. Animals with a loss ≥25% of starting body weight or showing signs of distress were euthanized.

Determination of RX100 pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability in rodents

Forty male and forty female C57BL/6 mice received a single subcutaneous dose of Rx100 (1 mg/kg in WFI). Blood was collected from four male and four female mice at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 18, 24, and 48 h after dosing via cardiac puncture and processed as described below.

For the determination of oral bioavailability, three rats of each sex received a dose of 2 mg/kg Rx100 via intragastric gavage (1 mg/mL, 2 µL dosing solution per g body weight) and three rats received an IV dose of 1 mg/kg (1 mg/mL, 1 µL dosing solution per g body weight). Blood was collected via jugular cannula at the indicated time points and collected into microtainer plasma separator tubes containing lithium heparin. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored frozen at −80°C until analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed for Rx100 concentration using a previously developed test method. This analytical test method is for use with an API 4000 LC/MS/MS System (AB SCIEX), a PVA Sil column (2.00 ×50 mm, YMC America, Inc., Allentown, PA), and a mobile phase of chloroform:methanol:water:ammonium hydroxide (250/100/10/1) with 10 mM ammonium acetate. The method included calibration standards ranging from 1 ng/mL to 2000 ng/mL and used 50 µL plasma with a water-saturated 1-butanol extraction. The injection volume was 10 µL with an isocratic flow rate of 300 µL/min using MRM scanning and negative mode (Rx100, 363/94.8 Q1/Q3; IS, 402.1/95 Q1/Q3).

Concentration data were imported into Phoenix 6.4 software (Certara Inc., Princeton, NJ) and statistical analysis was performed on concentrations with sorting of route of administration and time points. A non-compartmental analysis was performed on the mean concentration at each time for both routes of administration.

Closed-loop studies

Closed-loop studies were conducted similarly to previously published methods with minor modifications.41,42 Prior to the study initiation, mice were deprived of food for 18 h with free access to water. Mice were given Rimadyl (7.5 mg/kg, subcutaneously (SC)) 2 h prior to surgery to ameliorate post-operative pain. Animals were anesthetized by a single injection of xylazine/ketamine (87/13 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (IP)). Body temperature was maintained during surgery using a heated circulating water pad. A small abdominal incision was made to exteriorize the small intestine. Two ileal loops were ligated using suture and injected with 25 µl CTX (1 µg) + 25 µl of 10 mM histidine buffer or 25 µl CTX (1 µg) + 25 µl Rx100 (7.2 µg/mL).19,32 The abdominal and skin incisions were closed and mice were allowed to recover. Animals were sacrificed 6 h later and ileal loops were isolated and weighed before and after removal of fluid by longitudinal incision. Loop lengths were also measured and recorded. Fluid accumulation ratio (FAR) was calculated as weight of the loop with fluid/weight of the loop after fluid removal.

Open-loop studies

CTX (10 µg) prepared in bicarbonate buffer was delivered by oral gavage at time zero. Rx100 treatment was administered via SC or oral (PO) delivery of Rx100 at varying times in relation to CTX administration. Mice were sacrificed 6 h after CTX treatment. The gut was clamped at the pylorus and cecum, cleared of mesenteric tissue, and the length was measured and recorded. The weight of the intestinal segment from the pylorus to the cecum was recorded before (wet) and after removal of fluid by cutting longitudinally and gently blotting (dry). The weight ratio was calculated as above.

C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea model in mice

C57BL/6 mice were acclimated for seven days prior to use. C. rodentium (strain DBS100) from a frozen glycerol stock was streaked onto LB agar plates and incubated at 37°C overnight to obtain single colonies; 5 mL of sterile LB broth in a falcon culture tube was inoculated with a single colony from the nutrient agar plate and grown overnight at 37°C. Cell density was determined by measuring the optical density (OD) of the culture medium at 610 nm. Cell number corresponding to OD610 was determined by serial dilution and plating. Accordingly, mice were inoculated with 2 × 108 cells (100–150 µL) via oral gavage on study day 0. Beginning on day 1, mice received either Rx100 (SC, 0.1 or 1 mg/kg) or a volume matched vehicle. Dosing continued through study day 14. Animals were weighed every other day and stool samples were collected on study days 8, 10, and 12. Fecal pellet wet weights were recorded and pellets were stored at 37°C for 48 h at which time dry weights were collected. The water content of the fecal pellet was determined. Dry fecal pellets were extracted using HyClone WFI quality water (Fisher Scientific. and subjected to chloride assay (QuantiChrome Chloride Assay Kit, BioAssays Systems, Highland, UT) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture and treatments

Caco-2bbe cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD) were grown under standard cell culture conditions as described previously.43 Experiments were conducted using cells grown in polycarbonate membrane transwell inserts (6.5 mm diameter) (Costar, Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for nine days. Cell monolayers in transwell were preincubated with 20 µM of LPA or Rx100 15 min prior to incubation with CTX (5.1 µg/mL). Charcoal-stripped BSA (20 µM) and histidine (100 µM) were used a vehicle control for LPA and Rx100, respectively. After every 15 min, TER and inulin flux were measured as described previously.44

Epithelial barrier function

Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) was measured using a Millicell-ERS Electrical Resistance System (Millipore, Bedford, MA). TER was calculated as Ohms cm2 by multiplying it with the surface area of monolayer. To evaluate the paracellular permeability, cell monolayers were incubated with fluorescein isothio-cyanate (FITC)-inulin (6 kDa; 0.5 mg/mL) in the apical well and measured the unidirectional flux of FITC-inulin as described previously.44

Fluorescence microscopy

Caco-2 cell monolayers were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Following permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100™, monolayers were blocked in 4% nonfat milk in TRIS-buffered saline with Tween 20 (20 mM Tris, pH 7.2 and 150 mM NaCl) and stained for Occludin (green) and ZO-1 (red) by immunofluorescence methods as described previously.43 The fluorescence was examined by using a Zeiss LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope and 20× objective lens. Images from x–y (1 mm) sections were collected using the Zen software. Images from sections were stacked using Image J (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) and processed by Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Statistical analysis

Graphs are the representation of group means ± standard error of the mean unless otherwise noted. Statistical analysis was performed on efficacy studies using analysis of variance with a Tukey post hoc test. Results were considered statistically significant with a P value ≤0.05.

Results

Pharmacokinetic properties and oral bioavailability of Rx100 in rodents

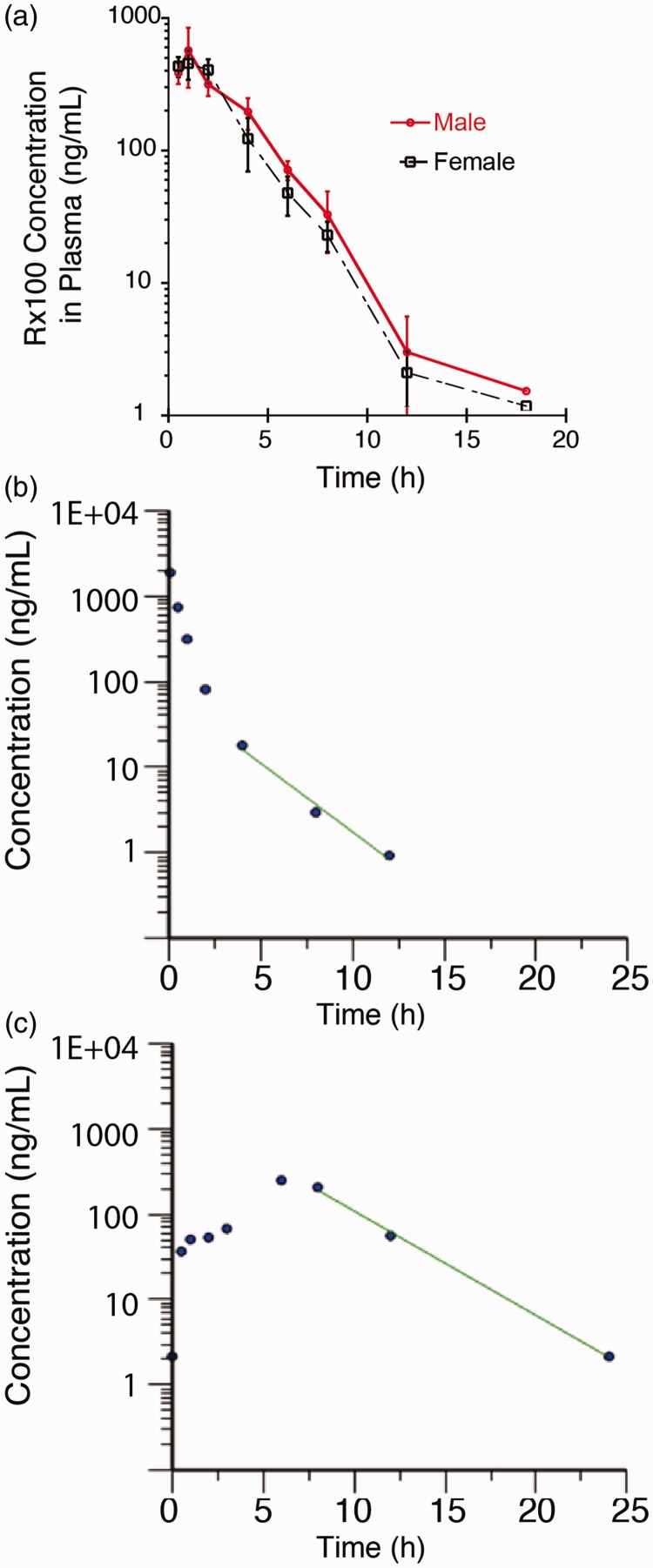

The pharmacokinetic properties of Rx100 were initially characterized in mice and was focused on the subcutaneous (SC) route of administration (Figure 2(a) and Table 1). Rx100 was rapidly absorbed after SC administration to healthy subjects with a Tmax of 1.0 h and a corresponding Cmax of 455 ng/mL in females and 570 ng/mL in males. The exposure (area under the curve, AUC) in females was 1593 h×ng/mL very similar to that of 1751.1 ng/mL in males.

Figure 2.

Panel (a). Plasma concentration profile of Rx100 administered subcutaneously to male and female mice (n = 4/sex/time point). Note that there were no sex-dependent differences in the plasma profile of Rx100 after SC administration. Panel (b). Plasma concentration profile of Rx100 administered intravenously to male rats (n = 3). Panel (c). Plasma concentration profile of Rx100 administered orally to male rats (n = 3). Note that Rx100 was rapidly absorbed and highly bioavailable (∼80%). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of a subcutaneously administered single dose (1 mg/kg) of Rx100 in mice.

| Gender | Cmax(ng/mL) | Tmax(h) | HL_Lambda_z(h) | AUCINF_obs(h×ng/mL) | CLss_F(mL/h/kg) | Vz_F(mL/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 454.50 | 1.00 | 1.84 | 1593.20 | 627.71 | 1664.32 |

| Male | 570.00 | 1.00 | 1.91 | 1751.12 | 571.10 | 1570.87 |

Establishing bioavailability of Rx100 in rats given orally expands its range of applications. The bioavailability was calculated by comparing the total exposure (AUC) of Rx100 in mice over the course of the study period normalized for dose. As expected, the maximum concentration observed was much greater in the IV group compared with the oral group (1880 ng/mL vs. 125 ng/kg) because of the immediate availability of the compound after IV administration. The bioavailability of Rx100 when administered orally in 10 mM histidine was approximately 80% as illustrated in the plasma concentration vs. time curve (Figure 2(b) and (c)). This suggests that 80% of the dose given orally was absorbed into the blood stream and was available for drug action. These data confirm our hypothesis and support the development of Rx100 use for both oral and SC routes of administration.

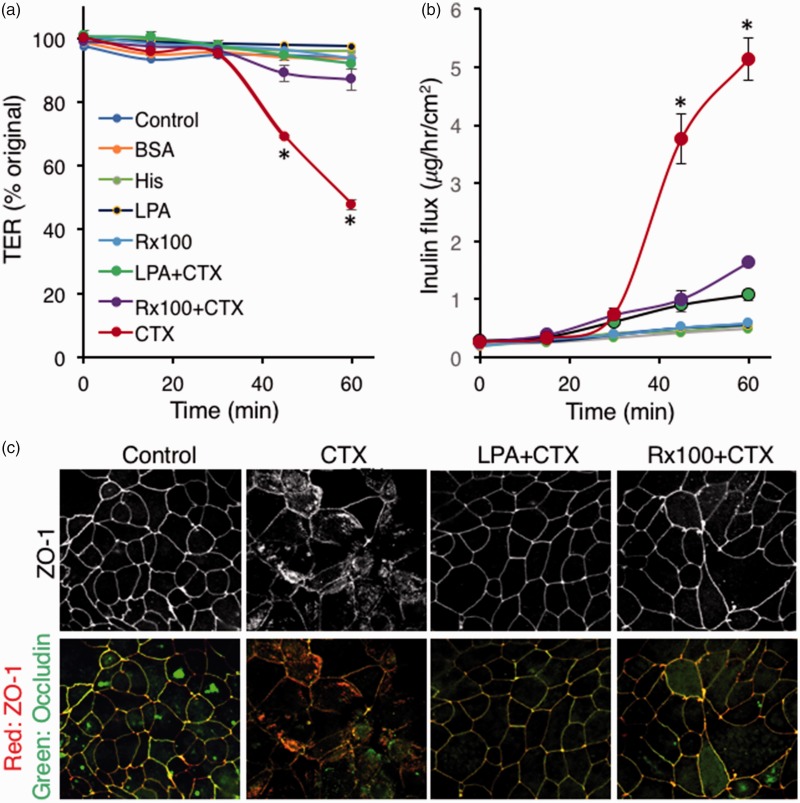

LPA and Rx100 decrease CTX-activated paracellular transport via enhancement of tight junctions. CFTR-mediate Cl− transport leads to the development of a luminal osmotic gradient that causes water movement into the lumen. The paracellular pathway is a major route of water and cation movement into the lumen. We examined whether LPA or Rx100 applied to Caco-2 polarized monolayer cultures would inhibit CTX-induced barrier leakiness measured by TER. LPA and Rx100 both significantly reduced CTX-induced decrease in TER by keeping the TER values similar to that seen in vehicle-treated controls (Figure 3(a)). We also tested inulin flux under these conditions and found that LPA and Rx100 significantly reduced CTX-induced inulin flux across the Caco-2 monolayer (Figure 3(b)). Next we examined the effect of LPA and Rx100 on the integrity of tight junctions using immunofluorescence staining for Occludin and zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1, Figure 3(c)). These immunofluorescence experiments revealed massive disruption of tight junctions following CTX application that was evident from the lack of colocalization of Occludin with ZO-1. LPA or Rx100 treatment of the Caco-2 cultures attenuated the disruption in the colocalization of these two tight junction proteins indicating that these agents effectively prevented disorganization of tight junctions.

Figure 3.

LPA and Rx100 prevent CTX-induced barrier leakiness, inulin transport, and the disruption of tight junctions. Panel (a). TER measurements showed that CTX (5.1 µg/mL) caused a robust time-dependent decrease in TER. Treatment of these cultures with 20 µM LPA or Rx100 blocked the action of CTX by maintaining TER close to that of the vehicle-treated monolayer cultures. Error bars represent SEM, P < 0.05 relative to CTX treatment. Panel (b). LPA and Rx100 reduced CTX-induced inulin influx (µg/h/cm2 ± SEM) of the polarized Caco-2 monolayers indicated by the significant reduction in the transport of fluorescently labeled inulin. Panel (c). Rx100 restores colocalization of Occluding with ZO1 after CTX treatment. Note that CTX disrupted the membrane localization of the junctional complexes marked by the colocalization of these two proteins. LPA and Rx100 maintained the colocalization of Occludin with ZO-1 tight junction markers after CTX (5.1 µg/mL) treatment (200× magnification). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

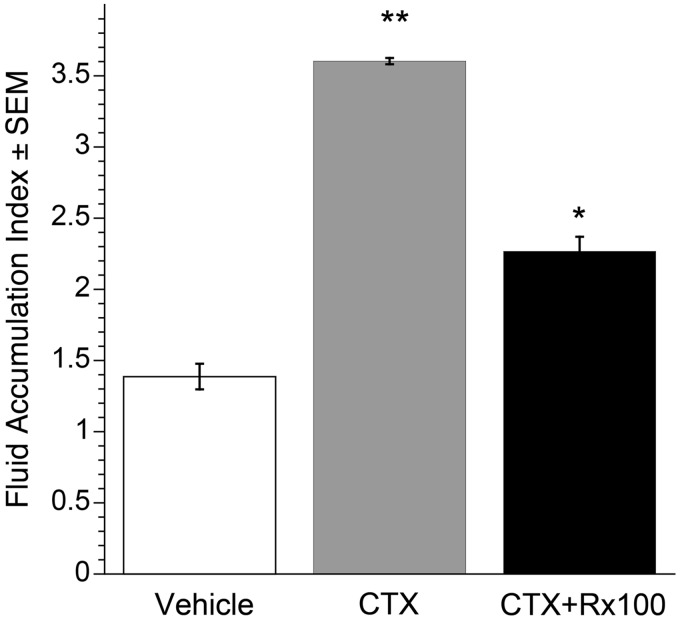

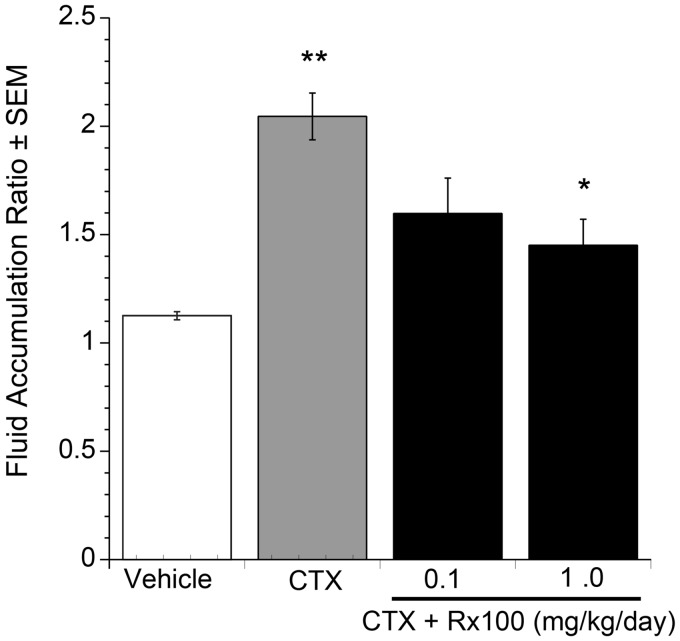

Rx100 inhibits CTX-induced fluid accumulation in an ileal closed-loop model. To provide proof of concept that Rx100 could be used as a drug therapy for SED, we first tested the effect of Rx100 on CTX-induced diarrhea in a closed-loop mouse model (Figure 4). We determined fluid accumulation in response to CTX injection in an isolated loop compared to that elicited by the injection of buffer or Rx100 alone. In this model, an increase in FAR measured by the wet vs. dry weight ratio is a marker of increased fluid secretion. Vehicle/buffer negative controls and CTX + vehicle positive controls were included in each study. The CTX groups were significantly different from the vehicle/buffer groups in each study (P ≤ 0.05). It is important to note that Rx100 alone had no effect on fluid accumulation. These results demonstrate the validity of our model and that Rx100 does not alter intestinal fluid basal secretion/absorption homeostasis.

Figure 4.

Rx100 is effective when administered (20 µM) in a closed ileal loop model. Data were collected at +4 h after CTX. **P<0.005 CTX causes significant increase in fluid secretion compared with vehicle. *P<0.05 Rx100 significantly reduces fluid secretion 6 h after CTX and Rx100 administration compared with CTX alone. Error bars represent SEM (n = 4–6 per group).

We next used this model to study the efficacy of Rx100 in preventing the CTX-induced diarrhea. Treatment with 20 µM Rx100 injected intraluminally at the same time as CTX reduced FAR 2-fold (Figure 4, P < 0.05). The histidine/bicarbonate vehicle was used as a negative control in these experiments and showed no effect in reversing the CTX-induced increase in FAR. The efficacy of Rx100 in the closed loop model justified further investigation of the effect of Rx100 using the open-loop model.

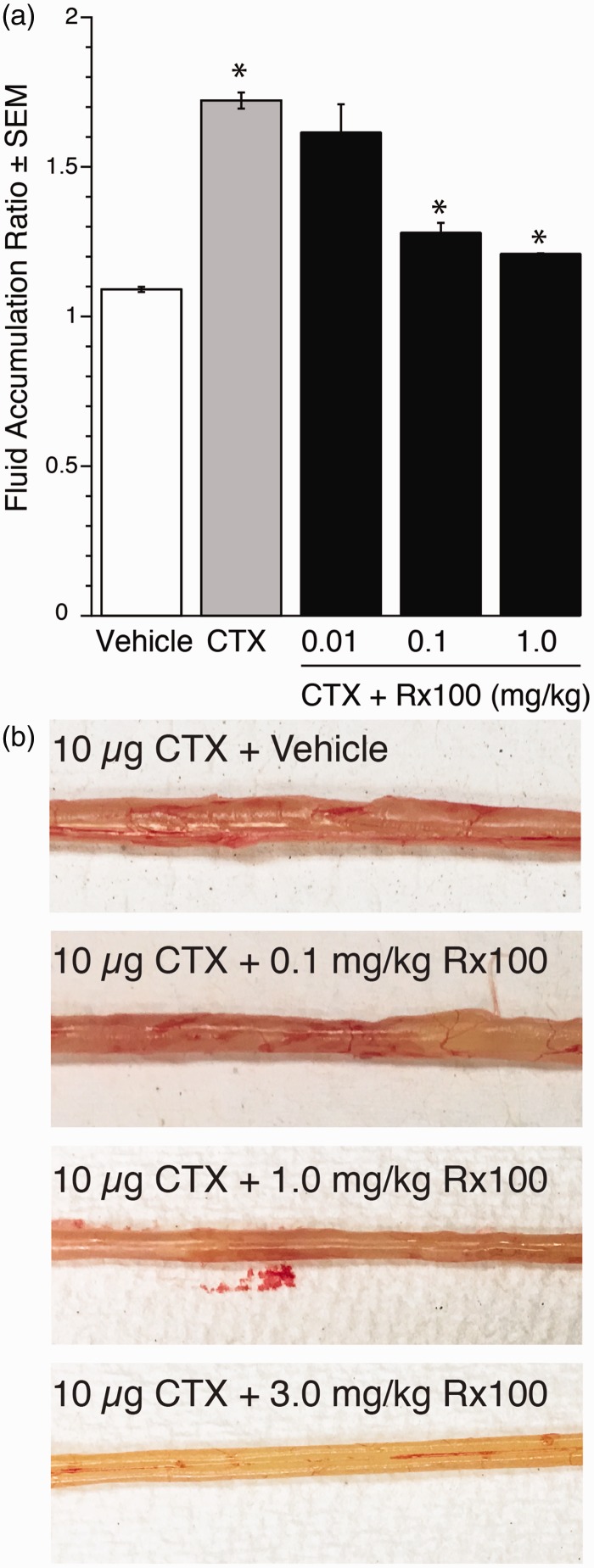

Rx100 inhibits CTX-induced fluid accumulation in the open ileal-loop model. The open loop model provides a more comprehensive assessment of fluid movement in the entire gut. In this model, when CTX was administered into the stomach, fluid secretion increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5), which validated the usefulness of our open loop model. Rx100 administered SC reduced the fluid accumulation in the CTX-treated open loops in a dose-dependent manner that was already statistically significant at the 0.1 mg/kg dose (Figure 6, P < 0.01). We next used the lowest effective dose to examine the effect of delaying administration in the open loop model.

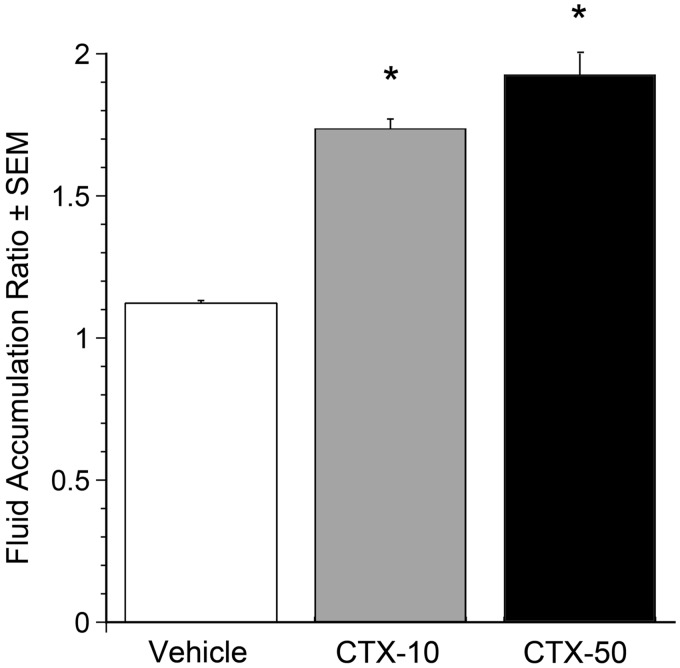

Figure 5.

Selection of 10 µg CTX for the open loop model. CTX (0, 10, or 50 µg) was administered orally at t = 0. 6 h after administration FAR was assessed. CTX at both 10 and 50 µg significantly increased FAR compared with vehicle *P<0.001. Error bars represent SEM; n = 7 for Vehicle and CTX-10, n = 2 for CTX-50. The submaximally effective 10 µg oral dose was chosen for subsequent experiments.

Figure 6.

Rx100 is effective when administered subcutaneously in the open loop CTX model. Panel (a). CTX and Rx100 (0.01–1 mg/kg, SC) were administered at 0 h (n = 3–4 per group). Samples were collected 6 h after CTX administration. **P<0.005 CTX causes significant increase in fluid secretion compared with vehicle (n = 8 per group). *P ≤ 0.01 Rx100 significantly reduces fluid accumulation compared with CTX + Vehicle treatment; error bars represent standard error of the mean Panel (b). Photographs of intestinal sections collected 6 h after CTX administration demonstrates the dose-dependent reduction of intestinal fluid accumulation by Rx100. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

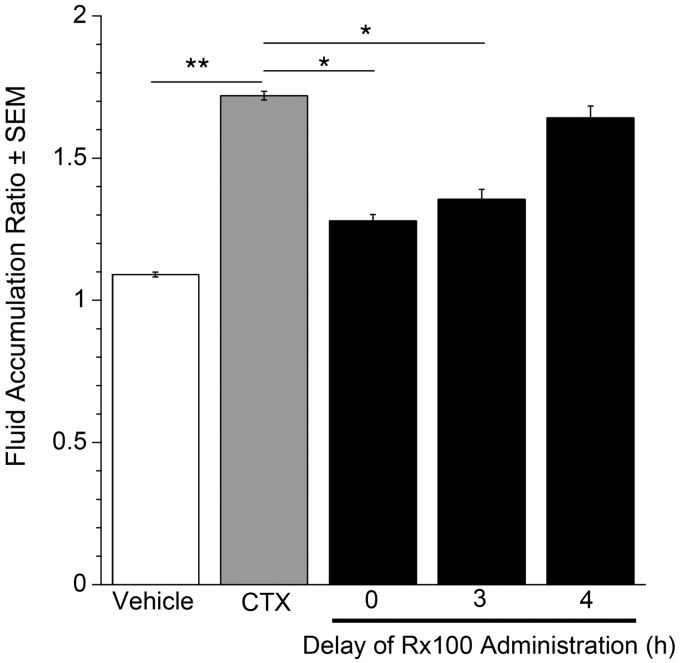

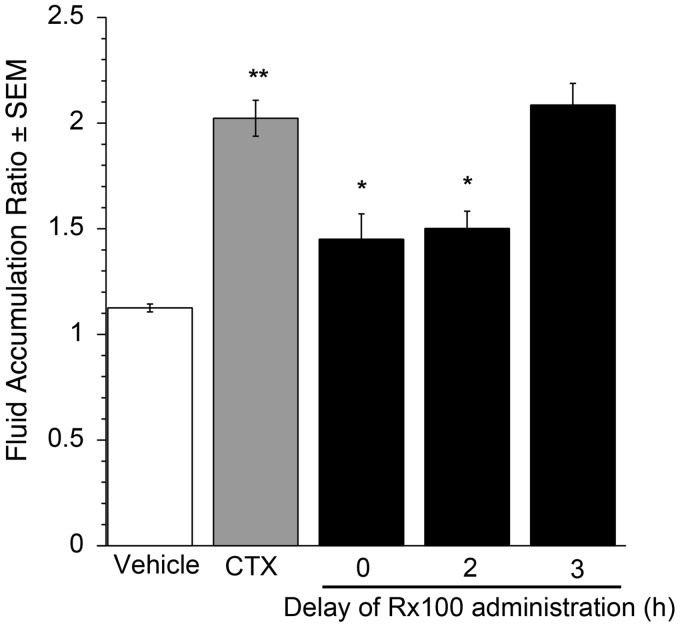

Rx100 is effective when administered to mice with full-blown CTX-induced diarrhea. Using the open-loop model established above, we examined the efficacy of Rx100 when administration was delayed after CTX exposure. Delayed administration of the drug in the open loop model is pathophysiologically more relevant for the assessment of its therapeutic potential for the treatment of patients with full-blown SED. Rx100 at its lowest effective dose of 0.1 mg/kg (SC) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced FAR when administration was delayed up to 3 h after exposure to CTX (Figure 7), and remained effective as late as 4 h after administration.

Figure 7.

The effective time-window for Rx100 treatment relative to CTX administration. Rx100 is effective when administered subcutaneously in the open loop CTX model. CTX was administered at 0 h and Rx100 (0.1 mg/kg, SC) was administered 0–4 h after CTX administration. **P<0.001 CTX causes significant increase in fluid accumulation compared with vehicle (n = 8 per group). *P ≤ 0.05 Rx100 significantly reduces fluid accumulation compared with CTX + Vehicle treatment (n = 10); error bars represent standard error of the mean. All samples were collected 6 h after CTX administration.

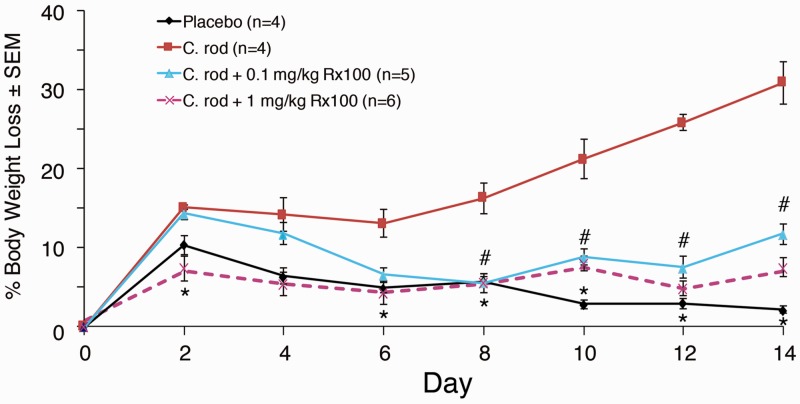

Rx100 inhibits C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea in mice. To better mimic the condition that accompanies infection with toxin-producing bacteria, we used a C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea model in mice to further elucidate the effect of Rx100 on SED. In this model, C. rodentium caused significant weight loss which accompanied increased fecal chloride content and demonstrated the suitability of the infection model for the diarrhea study (Figures 8 and 9). The time course of weight loss showed that Rx100 at the higher dose of 1 mg/kg was effective in completely preventing weight loss over the entire 14-day duration of the experiment (P ≤ 0.05). The lower 0.1 mg/kg dose has reversed weight loss by day 4 and the body weight in this group trailed that seen in the high-dose group for the remainder of the experiment (P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 8.

Rx100 prevents infection-induced weight loss. Animals were infected on Day 0 with C. rodentium orally. Mice received placebo or Rx100 (SC, 0.1 or 1 mg/kg) on days 1–14. #P ≤ 0.05; *P ≤ 0.01 Rx100 significantly prevents weight loss in animals infected with C. rodentium compared with infected animals not receiving Rx100. Error bars represent SEM; control groups n = 4, other groups n = 5–6. (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

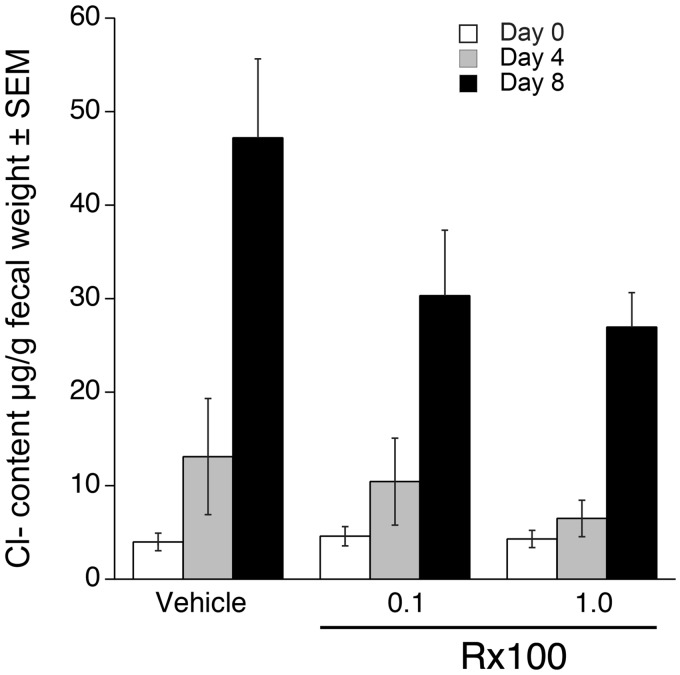

Figure 9.

Rx100 prevents infection-induced fecal chloride secretion. Animals were infected on Day 0 with C. rodentium orally. Mice received vehicle or Rx100 (SC, 0.1 or 1 mg/kg/day) on days 1–14. Samples were collected on day of infection and on postinfection days 4 and 8. Rx100 at both concentration reduced fecal Cl− content but it has not reached significance. Error bars represent SEM; uninfected/control group n = 4, other groups n = 6–12.

In the group of mice treated with Rx100 at 24 h post-infection, Cl− secretion measured by the Cl− content of stool pellets was reduced compared to the vehicle-treated group on day 4 (Figure 9). This decrease in Cl− secretion continued and increased by day 8 (Figure 9). Interestingly, both the 0.1 and 1.0 mg/kg doses of Rx100 caused similar decreases in chloride secretion on day 8 that parallels the lack of difference in body weight between these two groups of mice (Figures 8 and 9). In summary, these experiments consistently demonstrated that Rx100 prevented infection-induced diarrhea as evidenced by prevention of weight loss and lower fecal chloride content.

Orally administered Rx100 inhibits CTX-induced intestinal fluid secretion. Based on the evidence that Rx100 was orally bioavailable (Figure 2), we determined its effectiveness on SED of using the oral administration route. We applied the open loop mouse model of CTX-induced fluid secretion and found that 1.0 mg/kg Rx100 administered orally significantly reduced fluid secretion (P ≤ 0.01, Figure 10). A lower dose of 0.1 mg/kg dose of Rx100 also inhibited fluid secretion but was not significantly lower than CTX alone. We next determined the time course of effectiveness after oral delivery of Rx100 at the 1.0 mg/kg dose. Delaying treatment with Rx100 (1 mg/kg, PO) as long as 2 h after CTX maintained drug treatment efficacy in this model (Figure 11). The effectiveness of Rx100 even after delaying treatment by 2 h demonstrates promise for expanding practical field use. Together, these results establish that 1.0 mg/kg Rx100 delivered orally is highly effective in preventing CTX-induced diarrhea in mice. Furthermore, these results indicate that Rx100 is effective when delivered post-infection or after the onset of diarrhea.

Figure 10.

Rx100 is effective when orally administered in the open loop CTX model. CTX and Rx100 (0.1–1 mg/kg, PO) were administered at 0 h. Samples were collected 6 h after CTX administration. **P ≤ 0.02 CTX significantly increases fluid accumulation compared with vehicle. Rx100 administered at 1 mg/kg significantly reduces fluid accumulation compared with animals receiving CTX and vehicle *P ≤ 0.01; Error bars represent SEM; n = 6–12 per group.

Figure 11.

Effect of delayed administration of Rx100 on the FAR in the open loop CTX model. CTX was administered at 0 h and Rx100 (1 mg/kg, PO) was administered with delays between 0 and 3 h after CTX administration. Samples were collected 6 h after CTX administration. CTX significantly increases fluid accumulation compared with vehicle **P ≤ 0.005. Delaying administration by up to 2 h after CTX administration results in significantly reduced fluid accumulation than in animals receiving CTX and vehicle *P ≤ 0.001, Error bars represent SEM; n = 6 per group.

Discussion

SED is a major public health problem, especially in the developing world where sophisticated medical care that can rapidly replenish excessive fluid losses is rarely available compounded by the epidemic occurrence of the disease. The objective of the present study was to determine whether Rx100, a metabolically stabilized analog of LPA, would be effective in reducing fluid loss due to the toxin-mediated activation of the CFTR Cl− channel in the crypt enterocyte. Based on experiments conducted using CTX-induced closed- and open-loop models, and C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea models in mice, our findings establish that Rx100 has a therapeutic effect.

Rx100 alone did not affect the basal rate of fluid secretion in the ileum closed loop model. However, it significantly reduced FAR, a measure of luminal fluid secretion, indicative of decreased fluid excretion. This effect was already significant at the low 0.1 mg/kg dose delivered SC (Figure 6). Rx100 reduced fluid loss when administered to mice with full blown CTX-induced diarrhea. This suggests that the drug not only prevents but also reverses CTX-induced diarrheal fluid loss. Thus, it might prove to be beneficial in patients with symptomatic SED.

The observations made in the closed loop model were closely matched with our findings in the open-loop model that more closely resembles the human disease. In open loop model, Rx100 was proven effective when administered several hours after the onset of CTX-induced fluid discharge. These observations in the closed- and open-loop CTX-induced SED models are similar to our earlier observations made with the natural agent LPA.32 Mechanistically, we have previously determined and reported that LPA via the activation of the LPA2 GPCR makes a PDZ-motif-dependent physical interaction with NHERF2 and CFTR, and via Gi inhibits CTX-induced activation of cAMP production in the enterocyte.32 We have also shown that disruption of the assembly of this ternary macromolecular complex abolishes the inhibitory effect of LPA2 on CFTR-mediated Cl− efflux into the lumen.32 Rx100 is a full agonist of the LPA2 receptor and has a longer half-life than LPA has in vivo.

We also found that Rx100 protected Caco-2 cell monolayers from CTX-induced barrier leakiness. Our data shown in Figure 3 extend previous intestinal barrier protection studies conducted with LPA to Rx100, which with an efficacy similar to the natural mediator maintained TER and reduced inulin flux across the monolayer.38 Mechanistically, we provide evidence that Rx100 achieved a part of its barrier protective effect by maintaining the integrity of tight junctions in CTX-treated monolayers indicated by the preservation of ZO-1 and Occludin colocalization. These results taken together make Rx100 a drug-like compound that has similar therapeutic benefits to LPA with multiple protective mechanisms in toxin-challenged epithelial layers.

We have extended the testing of Rx100 to the C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea in mice. This model better mimics the human disease because it is accompanied by the complex immune response as well as the bacterial invasion of the entire organism. For these reasons, it is most important to recognize that Rx100 showed similar anti-diarrheal action in this model as it did in the CTX-injection models. Here we also determined stool Cl− concentration that confirmed our hypothesis that Rx100 reduced Cl− influx into the gut lumen.

ORT is the most widely used field therapy for the treatment of SED. However, some SED patients also vomit which limits the effectiveness of ORT. In this context, SC administration using a self-injectable syringe to deliver Rx100 appears to be a feasible drug delivery method in patients who cannot keep ORT down. However, many patients can consume ORT and in such cases the ease of orally delivered Rx100 pills would be preferred. A pharmacokinetic study was completed in mice and aided in the Rx100 dose and interval selection in the initial studies; however, to test the feasibility of oral delivery of Rx100, we determined its oral bioavailability and found that approximately 80% of the drug is bioavailable. This established the feasibility of oral testing in the C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea model. Rx100 was effective when delivered PO as evidenced by the lack of weight loss in treated mice. The therapeutic effect was most robust at the higher 1 mg/kg/day dose group but from day 4 even the lower 0.1 mg/kg/day group showed no weight loss. Taken together, Rx100 offers therapeutic benefits when given subcutaneously or orally in the C. rodentium infection-induced diarrhea model. Thus, it might also show similar therapeutic benefits in patients with toxin-induced SEDs. In the next stage of our studies, we aim to initiate human phase 1 studies to assess the therapeutic feasibility of using Rx100 in the treatment of SED.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in some parts of the design, interpretation of the resulting data, and review of the manuscript. KET, RMR, SA, WG, AB, AM, and PKS conducted the experiments. KET, RMR, AB, and GT designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests

GT, LRJ, and WSM are founders of and shareholders in RxBio Inc. KT and AB are shareholders in RxBio, Inc.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH Grants 1R43DK105719-01A1 (KT), U01AI080405 (GT), The VA Research System 1101BX001187 (GT), and the Van Vleet Endowment (GT).

References

- 1.Deshpande ADS, Lever E. Soffer acute diarrhea, www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/gastroenterology/acute-diarrhea/ (2016, accessed 14 September 2018)

- 2.Organization WH. The top 10 causes of death, www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ (2016, accessed 14 September 2018)

- 3.Thiagarajah JR, Yildiz H, Carlson T, Thomas AR, Steiger C, Pieretti A, Zukerberg LR, Carrier RL, Goldstein AM. Altered goblet cell differentiation and surface mucus properties in Hirschsprung disease. PLoS One 2014; 9:e99944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. Somalia-Cumulative number of Acute Watery Diarrhea/Cholera cases from 2 January to 21 May 2017, www.who.int/emergencies/famine/Somalia-cholera-020117-210517.png?ua=1 (accessed 14 September 2018)

- 5.Organization WH. Yemen-cumulative number of acute watery diarrhea/cholera cases from 27 April to 27 May 2017, www.who.int/emergencies/famine/Yemen-cholera-270417-270517.png?ua=1 (accessed 14 September 2018)

- 6.Muanprasat C, Kaewmokul S, Chatsudthipong V. Identification of new small molecule inhibitors of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein: in vitro and in vivo studies. Biol Pharm Bull 2007; 30:502–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muanprasat C, Sirianant L, Soodvilai S, Chokchaisiri R, Suksamrarn A, Chatsudthipong V. Novel action of the chalcone isoliquiritigenin as a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) inhibitor: potential therapy for cholera and polycystic kidney disease. J Pharmacol Sci 2012; 118:82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiagarajah JR, Verkman AS. Chloride channel-targeted therapy for secretory diarrheas. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2013; 13:888–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namkung W, Thiagarajah JR, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels by gallotannins as a possible molecular basis for health benefits of red wine and green tea. FASEB J 2010; 24:4178–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munos MK, Walker CL, Black RE. The effect of oral rehydration solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhoea mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2010;( 39 Suppl 1):i75–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels NA, Simons SL, Rodrigues A, Gunnlaugsson G, Forster TS, Wells JG, Hutwagner L, Tauxe RV, Mintz ED. First do no harm: making oral rehydration solution safer in a cholera epidemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 60:1051–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization WH. WHO global task force on cholera control. Geneva: Author, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organization WH. The treatment of diarrhoea A manual for physicians and other senior health workers. 4th revision Geneva: Author. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frampton JE. Crofelemer: a review of its use in the management of non-infectious diarrhoea in adult patients with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs 2013; 73:1121–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clay PG, Crutchley RD. Noninfectious diarrhea in HIV seropositive individuals: a review of prevalence rates, etiology, and management in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Infect Dis Ther 2014; 3:103–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro JG, Chin-Beckford N. Crofelemer for the symptomatic relief of non-infectious diarrhea in adult patients with HIV/AIDS on anti-retroviral therapy. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2015; 8:683–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiagarajah JR, Song Y, Haggie PM, Verkman AS. A small molecule CFTR inhibitor produces cystic fibrosis-like submucosal gland fluid secretions in normal airways. FASEB J 2004; 18:875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiagarajah JR, Ko EA, Tradtrantip L, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Discovery and development of antisecretory drugs for treating diarrheal diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:204–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Clin Invest 2002; 110:1651–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi JW, Herr DR, Noguchi K, Yung YC, Lee CW, Mutoh T, Lin ME, Teo ST, Park KE, Mosley AN, Chun J. LPA receptors: subtypes and biological actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2010; 50:157–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canani RB, Cirillo P, Buccigrossi V, Ruotolo S, Passariello A, De Luca P, Porcaro F, De Marco G, Guarino A. Zinc inhibits cholera toxin-induced, but not Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin-induced, ion secretion in human enterocytes. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryu JM, Han HJ. Autotaxin-LPA axis regulates hMSC migration by adherent junction disruption and cytoskeletal rearrangement via LPAR1/3-dependent PKC/GSK3beta/beta-catenin and PKC/Rho GTPase pathways. Stem Cells 2015; 33:819–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luerang W, Khammee T, Kumpum W, Suksamrarn S, Chatsudthipong V, Muanprasat C. Hydroxyxanthone as an inhibitor of cAMP-activated apical chloride channel in human intestinal epithelial cell. Life Sci 2012; 90:988–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukushima N, Chun J. The LPA receptors. Prostagland Other Lipid Mediat 2001; 64:21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem 1987; 56:615–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun J, Hla T, Lynch KR, Spiegel S, Moolenaar WH. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev 2010; 62:579–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tigyi G. Aiming drug discovery at lysophosphatidic acid targets. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 161:241–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukushima N, Ishii I, Contos JJ, Weiner JA, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2001; 41:507–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng W, Balazs L, Wang DA, Van Middlesworth L, Tigyi G, Johnson LR. Lysophosphatidic acid protects and rescues intestinal epithelial cells from radiation- and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:206–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yun CC, Sun H, Wang D, Rusovici R, Castleberry A, Hall RA, Shim H. LPA2 receptor mediates mitogenic signals in human colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2005; 289:C2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Morito K, Kinoshita M, Ohmoto M, Urikura M, Satouchi K, Tokumura A. Orally administered phosphatidic acids and lysophosphatidic acids ameliorate aspirin-induced stomach mucosal injury in mice. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58:950–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C, Dandridge KS, Di A, Marrs KL, Harris EL, Roy K, Jackson JS, Makarova NV, Fujiwara Y, Farrar PL, Nelson DJ, Tigyi GJ, Naren AP. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits cholera toxin-induced secretory diarrhea through CFTR-dependent protein interactions. J Exp Med 2005; 202:975–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh AK, Riederer B, Krabbenhoft A, Rausch B, Bonhagen J, Lehmann U, de Jonge HR, Donowitz M, Yun C, Weinman EJ, Kocher O, Hogema BM, Seidler U. Differential roles of NHERF1, NHERF2, and PDZK1 in regulating CFTR-mediated intestinal anion secretion in mice. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:540–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Fujii N, Naren AP. Recent advances and new perspectives in targeting CFTR for therapy of cystic fibrosis and enterotoxin-induced secretory diarrheas. Future Med Chem 2012; 4:329–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albers HM, Dong A, van Meeteren LA, Egan DA, Sunkara M, van Tilburg EW, Schuurman K, van Tellingen O, Morris AJ, Smyth SS, Moolenaar WH, Ovaa H. Boronic acid-based inhibitor of autotaxin reveals rapid turnover of LPA in the circulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:7257–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virag T, Elrod DB, Liliom K, Sardar VM, Parrill AL, Yokoyama K, Durgam G, Deng W, Miller DD, Tigyi G. Fatty alcohol phosphates are subtype-selective agonists and antagonists of lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2003; 63:1032–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin S, Yeruva S, He P, Singh AK, Zhang H, Chen M, Lamprecht G, de Jonge HR, Tse M, Donowitz M, Hogema BM, Chun J, Seidler U, Yun CC. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates the intestinal brush border Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 and fluid absorption via LPA(5) and NHERF2. Gastroenterology 2010; 138:649–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gangwar R, Meena AS, Shukla PK, Nagaraja AS, Dorniak PL, Pallikuth S, Waters CM, Sood A, Rao R. Calcium-mediated oxidative stress: a common mechanism in tight junction disruption by different types of cellular stress. Biochem J 2017; 474:731–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng W, ES, R, Tsukahara WJ, Valentine G, Durgam V, Gududuru L, Balazs V, Manickam M, Arsura L, VanMiddlesworth LR, Johnson AL, Parrill DD, Miller G. Tigyi The lysophosphatidic acid type 2 receptor is required for protection against radiation-induced intestinal injury. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:1834–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng W, Kimura Y, Gududuru V, Wu W, Balogh A, Szabo E, Thompson KE, Yates CR, Balazs L, Johnson LR, Miller DD, Strobos J, McCool WS, Tigyi GJ. Mitigation of the hematopoietic and gastrointestinal acute radiation syndrome by octadecenyl thiophosphate, a small molecule mimic of lysophosphatidic acid. Radiat Res 2015; 183:465–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luan J, Zhang Y, Yang S, Wang X, Yu B, Yang H. Oridonin: a small molecule inhibitor of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) isolated from traditional Chinese medicine. Fitoterapia 2015; 100:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muanprasat C, Wongkrasant P, Satitsri S, Moonwiriyakit A, Pongkorpsakol P, Mattaveewong T, Pichyangkura R, Chatsudthipong V. Activation of AMPK by chitosan oligosaccharide in intestinal epithelial cells: mechanism of action and potential applications in intestinal disorders. Biochem Pharmacol 2015; 96:225–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao RK, Basuroy S, Rao VU, Karnaky KJ, Jr, Gupta A. Tyrosine phosphorylation and dissociation of occludin-ZO-1 and E-cadherin-beta-catenin complexes from the cytoskeleton by oxidative stress. Biochem J 2002; 368:471–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samak G, Suzuki T, Bhargava A, Rao RK. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-2 mediates osmotic stress-induced tight junction disruption in the intestinal epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010; 299:G572–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]