Abstract

Background:

Currently, the leading theme in mucogingival surgery is the correction of gingival recession defects. Free gingival graft (FGG) has been successfully in use in this category of reconstructive therapeutic modality.

Objectives:

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the literature with respect to efficacy of FGG in the management of Miller Class I and II localized gingival recessions.

Data Sources:

Search strategies were performed via electronic database which included Pubmed-Medline, Google scholar and manual search using University library resources. Two reviewers assessed the eligibility of the studies.

Study Eligibility Criteria:

Controlled clinical trials, randomized clinical trials and longitudinal studies evaluating recession areas treated by FGG with minimum of 6 months follow up were included. In-vitro and animal studies, studies mainly done on Miller Class III and IV gingival recession defect, studies on multiple gingival recessions and case series and case reports were excluded from the search.

Results:

The electronic and manual search identified a total of 557 articles. A final screen consisted of 39 articles out of which 17 articles were selected for full-text assessment. Finally, 7 articles were selected for detailed evaluation for this systematic review. FGG has shown significant results in all the studies except for one study.

Conclusion:

FGG produces substantial results, however, highly depends on the case selection and operator's skill and experience. FGG gives an impression of being the best alternative option in zones where gingival recession presents with inadequate width of attached gingiva and depth of vestibular fornix.

Keywords: Graft(s), gingival recession, mucogingival surgery, systematic reviews and evidence-based medicine

INTRODUCTION

Various mucogingival surgeries are described for the insufficient dimension of soft-tissue recession and keratinized gingiva. From the past few decades, several surgical techniques, not only for the preservation but also for the increase of the gingival dimension as part of periodontal treatment, were described in the periodontal literature.[1,2,3,4,5] The 1996 World Workshop in Periodontics[6] has stressed primarily on regaining gingival tissue coverage over the denuded root surface, with the ultimate goal of complete root coverage (CRC) and esthetics satisfaction rather than increasing width of attached gingiva.

Mucogingival surgery done for recession coverage becomes a necessity when esthetics, dentinal sensitivity, and carious and noncarious cervical lesions poses a problem.[7] Moreover, the presence of recession defects creates unfavorable contour of the gingival margin or leads to insufficient keratinized gingiva, thereby, limiting the proper plaque control.

Many surgical techniques have been reported in literature to perform root coverage such as lateral pedicle flap, double papilla flap, oblique rotated flap, free gingival graft (FGG), coronally advanced flap (CAF), semilunar coronally repositioned flap, and subepithelial connective tissue graft (SCTG) with combinations of grafting techniques and flap designs.[8,9,10]

Even though all the above procedures have demonstrated potential for recession coverage, meta-analysis from several systematic reviews and the Consensus report of the 6th European Workshop on Periodontology in 2014 affirmed that the CAF as a stand-alone technique and predictable method for recession coverage in localized Miller Class I and Class II gingival recessions.[11,12]

The majority of the published literature on Miller Class I and Class II soft-tissue recession have demonstrated better results with SCTG, hence, regarded as “gold standard” approach for root-coverage procedures.[13] On the contrary, a survey conducted by Zaher et al.,[14] indicated that FGG was the favorite choice of the clinicians for the management of denuded root surface despite of its disadvantages, followed by the SCTG, and the CAF.

The FGG has been used in root surface coverage associated with isolated recession defect since the first report outlining the rationale and surgical principles described by Sullivan and Atkins in 1968.[15] Primary root coverage, noted immediately following grafting, is seen due to bridging that is persistent of grafted soft tissue on avascular root surfaces, whereas secondary root coverage refers to the “creeping attachment” as described by Goldman.[16,17] This creeping attachment was also noticed by many authors as a postsurgical migration of the gingival margin in an upward direction, to cover partially or completely previously exposed root surface as contrast to the reports of Rateitschak where there was no improvement noted in the degree of recession after 5 years postoperatively.[18,19,20,21,22,23,24]

Free autogenous gingival graft, derived from attached gingiva, used both as a one-step or a two-step technique for root coverage, is a multipurpose therapeutic approach and is used in different clinical conditions.[25] The good vascularity of the oral mucosa augments the FGG applicability for the correction of recession defects.[26]

The relationship in-between graft thickness and functional resistance has been a material of argument. Increase in functional resistance has been accredited to the thickness of gingival grafts. Although this method can produce an unesthetic result at the recipient site.[27] The subepithelial connective tissue produces a good esthetic result but requires a thicker donor palatal tissue than the FGG technique where FGG of 0.9 mm thickness has been demonstrated to be functionally adequate.[27,28]

There have been many systematic reviews comparing various treatment modalities used in the management of gingival recession.[8,29] However, there is no systematic review available concerning the efficacy of FGG in the management of Miller Class I and Class II localized marginal tissue recession.

Focused question

What is the feasibility of FGG in the management of Miller Class I and Class II localized gingival recessions?

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review was to assess the literature regarding the efficacy of FGG in the management of Miller Class I and Class II localized gingival recessions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility criteria

Articles were screened considering the inclusion and rejection criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Studies qualified for consideration, in this review were controlled clinical trials, randomized clinical trials (RCTs), and longitudinal studies evaluating Miller Class I and Class II marginal tissue recessions which included treatment with FGG with no <6 months of follow-up.

Rejection criteria

Studies done in vitro or on animal were excluded; studies reporting case series, case reports, or multiple gingival recessions were eliminated; and studies primarily done on Miller Class III to Class IV recessions were also excluded from the study.

Information sources and search protocol

A comprehensive search convention was created and taken after as indicated by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis). Search strategies were performed through an electronic database which included PubMed-Medline, Google Scholar, and manual search using university library resources. Articles in English were preferred. These databases were looked up to December 2016 utilizing the search strategies. All cross-references list of the chosen articles were screened for extra literature that could meet the qualification criteria.

Study selection

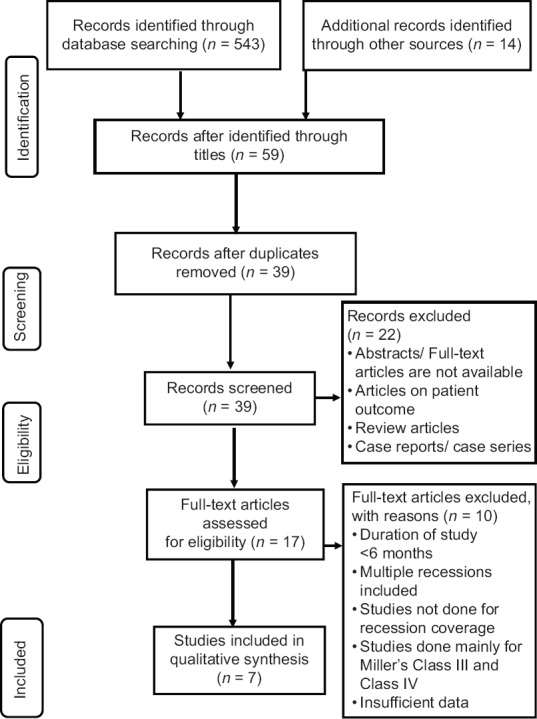

After entering the search strategy, preliminary screening was done. The primary screening comprised cumulative of 557 articles, of which 59 articles were distinguished through the title, and 39 articles remained after the removal of duplicates. All these articles were screened. Of these, 22 articles were excluded due to nonavailability of the articles or by reading abstracts as they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Seventeen full-content articles were evaluated for qualification. Again, out of which, ten articles were omitted as they were unable qualify eligibility criteria. Finally, 7 out of 17 were considered appropriate for the review [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis flow diagram. n – Number of articles

Selected studies quality evaluation

RCTs and clinical evaluation study were included in this study. Three main quality criteria were examined as follows: technique used to prevent selection bias, investigators blinding, and completion of evaluation time.[30] Quality assessment was based on as follows:

The study was regarded to be at lower risk of bias if all the three criteria were fulfilled

The study was regarded to be at high risk of bias if one criterion was fulfilled.

The quality evaluation of the involved articles uncovered a high inclination towards bias for all except for the study done by Kuru and Yıldırım.[31]

Data collection method

A standard trial form in Excel sheet was preliminary prepared and after that each one of those headings not relevant was removed by the reviewer. Data extraction was done for one article, and this frame was finalized by an expert.

Data items

Study design, sample size, participants’ description, condition, intervention/exposure, mean root coverage (MRC), evaluation time, confounders, recession depth (RD), recession width (RW), pocket depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), width of keratinized gingiva (WKG), exposed root surface (ERS), and the result were extracted from the articles if mentioned. Data extraction of only FGG group was done in the case of studies having a comparative group.

Outcome measurement

The accompanying result measures were considered as follows:

Main outcome:

Gingival recessions that attained MRC.

Secondary outcomes:

Change in RD expressed as reduction in recession (in mm) at final evaluation

Change in PD expressed (in mm) at final evaluation

Change in CAL expressed as CAL gain (in mm) at final evaluation

Change in WKG expressed as WKG gain (in mm) at final evaluation.

RESULTS

Data regarding the percentage of root coverage obtained, changes in RD, WKG, PD and CAL are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Author | Location | Year of publication | Study design | Setting | Intervention/exposure | Sample size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Borghetti and Gardella[1] | France | 1990 | Clinical evaluation | Dental Institute | FGG | 23 | |||

| 2 | Tolmie et al.[16] | Carolina | 1991 | RCT | Private practice | FGG | 103 | |||

| 3 | Jahnke et al.[32] | Bethesda | 1993 | RCT | Dental Institute | FGG | 9 | |||

| 4 | Paolantonio et al.[33] | Rome | 1997 | RCT | Private practice | FGG | 35 | |||

| 5 | Ito et al.[34] | Japan | 2000 | RCT | Dental Institute | FGG | 4 | |||

| 6 | Kuru and Yıldırım[31] | Turkey | 2013 | RCT | Dental Institute | FGG involving marginal gingiva and papillae | 8 | |||

| FGG | 9 | |||||||||

| 7 | Jenabian et al.[35] | Iran | 2016 | RCT | Dental Institute | FGG involving marginal gingiva and papillae | 9 | |||

| FGG | 9 | |||||||||

| Author | Participants description | Condition | Evaluation time | MRC | ||||||

| Number of patients | Gender of patients | Age range (years) | Percentage | SD | ||||||

| Borghetti and Gardella[1] | 14 | 2 males, 12 females | 16-62 | Miller Class I, Class II, and Class III | 1 year | 85.2 | ||||

| Tolmie et al.[16] | 58 | NR | NR | Miller Class I and Class II | 15 months | 86.7 | ||||

| Jahnke et al.[32] | 10 | 5 males, 5 females | 16-51 | Miller Class I and Class II | 6 months | 43 | ||||

| Paolantonio et al.[33] | 70 | 32 males, 38 females | 25-48 | Miller Class I and Class II | 5 years | 53.19 | 21.48 | |||

| Ito et al.[34] | 6 | 3 males, 3 females | 22-58 | Miller Class I and Class II | 1 year | 87.8 | 17.4 | |||

| Kuru and Yıldırım[31] | 8 | 5 males, 12 females | NR | Miller Class I and Class II | 8 months | 91.62 | 9.74 | |||

| 9 | 5 males, 12 females | NR | Miller Class I and Class II | 8 months | 68.97 | 13.67 | ||||

| Jenabian et al.[35] | 9 | NR | NR | Miller Class I and Class II | 6 months | 60.52 | 21.22 | |||

| 9 | NR | NR | Miller Class I and Class II | 45.52 | 21.94 | |||||

| Author | Confounders | RD (mm) | RW (mm) | PD (mm) | CAL (mm) | |||||

| Baseline | Final | Narrow baseline | Wide baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | ||

| Borghetti and Gardella[1] | Miller Class III also included | 3.04±0.82 | 0.45±0.50 | 2.47±0.44 | 4.16±0.65 | NR | 1.96±0.63 | 1.34±0.39 | NR | NR |

| Tolmie et al.[16] | 3.15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Jahnke et al.[32] | 2.9 | 1.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4.7 | 3.1 | |

| Paolantonio et al.[33] | 3.11±0.28 | 1.50±0.39 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Ito et al.[34] | 3.63±0.92 | 0.50±0.76 | NR | NR | NR | 1.25±0.46 | 1 | 4.88±0.64 | 1.5±0.76 | |

| Kuru and Yıldırım[31] | 3.50±0.53 | 0.31±0.37 | NR | NR | NR | 1.25±0.46 | 0.81±0.25 | 4.75±0.70 | 1.12±0.44 | |

| 3.55±0.88 | 1.16±0.79 | NR | NR | NR | 1.33±0.50 | 1.22±0.36 | 4.88±0.78 | 2.27±0.79 | ||

| Jenabian et al.[35] | 4.11±1.63 | 1.83±1.47 | 3.00±1.19 | 1.94±0.72 | 1.22±083 | 0.83±0.25 | 5.33±1.85 | 2.66±1.56 | ||

| 3.72±1.46 | 2.00±1.11 | 3.16±1.54 | 2.44±1.21 | 1.44±0.28 | 1.00±0.08 | 5.05±1.66 | 3.00±1.17 | |||

| Author | WKG (mm) | ERS (mm2) | Result | Remark | ||||||

| Baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | |||||||

| Borghetti and Gardella[1] | 1.72±1.45 | 7.20±2.36 | NR | NR | Thick FGG results in considerable coverage. Narrow recessions give better results for root coverage | Good results with small sample size | ||||

| Tolmie et al.[16] | NR | NR | NR | NR | Predictable procedure in selected cases | Good results with large sample size | ||||

| Jahnke et al.[32] | 1 | 4 | NR | NR | Width and depth of gingival recession did not have association with the amount of root coverage | Less root coverage and also small sample size used | ||||

| Paolantonio et al.[33] | 1.57±0.34 | 5.23±0.48 | 7.54±1.15 | 3.70±1.30 | Results in good accordance with the mean values reported in the literature | Averages results | ||||

| Ito et al.[34] | 2.13±0.84 | 7.88±2.03 | NR | NR | Effective for adjacent root coverage | Good results but small sample size | ||||

| Kuru and Yıldırım[31] | 1.43±0.62 | 7.12±0.58 | NR | NR | Acceptable results with gingival unit grafting | Excellent results | ||||

| 1.72±0.83 | 5.94±1.18 | NR | NR | Conventional technique is more useful in increasing WKG | Significant result seen | |||||

| Jenabian et al.[35] | 2.44±1.52 | 5.05±1.01 | NR | NR | Superior clinical and esthetic outcomes | Significant result seen | ||||

| 2.16±1.47 | 4.38±1.36 | NR | NR | Significant improvement in clinical parameters | Averages results | |||||

RCT – Randomized clinical trial; FGG – Free gingival graft; RD – Recession depth; RW – Recession width; PD – Pocket depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; MRC – Mean root coverage; SD – Standard deviation; WKG – Width of keratinized gingiva; ERS – Exposed root surface; NR – Not Reported

The evaluation of root coverage obtained by thick gingival graft in 23 gingival recessions showed mean recession coverage of 2.59 ± 0.67 mm at 1 year, where mean graft thickness was 1.81 ± 0.32 mm. It was concluded by the author that the thick gingival autograft results in considerable coverage of 85.2% of the denuded root surfaces where creeping attachment contributes to 28% of the final degree of recession coverage. Furthermore, narrow recessions showed better results than wide recessions.[1]

Treatment of denuded root surface with FGG was performed by a group of multiple clinicians in 103 Miller Class I and Class II gingival recession defects reported average root coverage of 87.6% after 12 months. The outcomes of these studies indicated that the success in this procedure could be attained by appropriate case selection and the technique.[16]

Another RCT included in this study compared and determined the clinical efficacy of root-coverage procedures (thick FGG verses SCTG) in 10 subjects having 20 Miller Class I and Class II recession defects. FGG resulted in a significant improvement in WKG and PD during the first 3 months, and no noteworthy changes were noticed at the end of 6 months postsurgically. The average root coverage for the FGG was 43% at the two-time frames.[32]

A RCT comparing FGG (n = 35) and bilaminar connective subpedicle grafts (n = 35) showed mean percentage of root coverage of 53.19% ± 21.48 with FGG at the end of 5 years.[33] The comparison of FGG to that of guided tissue regeneration technique showed average root coverage of 87.80% after FGG surgical intervention.[34]

Last two RCT studies involved gingival unit transfer comparison with conventional FGG. Both the studies have reported good results with gingival unit transfer.

DISCUSSION

The result of this systematic review presented with greater reduction in gingival recession depth with gain in WKG and CAL and reduction in probing depth compared to baseline parameters. Except for the study done by Jahnke et al.,[32] all other individual studies reported in this review have shown statistically significant results. Although Paolantoni et al.[33] have shown statistically significant result, the outcome produced clinically with FGG after 5 years of follow-up could be considered as average.

The best result has been shown by Kuru and Yıldırım[31] using modification in the FGG harvesting technique and also proposed that conventional technique should be used only in cases where WKG is inadequate. However, unfortunately, there are not enough studies done on gingival unit grafts to determine its efficacy.

A limitation in the analysis of this review was seen due to appearance of insufficient clinical parameters in some of the selected articles. Another shortcoming seen with the studies was the varied number of participants ranging from 4 to 103.[1,16,31,32,33,34,35] This variation could have strongly influenced statistical analysis.

Studies conducted on Miller Class I and Class II gingival recession were included in this present systematic review except for the study done by Borghetti et al.[1] where Class III gingival recession would have acted as a confounding factor in the treatment outcome. However, the recession coverage outcomes seen were good when compared to baseline.

Holbrook and Ochsenbein[9] showed CRC on 22 out of 50 teeth which accounts for 44%. Furthermore, they noticed recession coverage of 95.5% when RD was <3 mm which was in agreement with other studies.[1,36] Michaelides and Wilson[37] have reported 96% of root coverage in 26 sites out of 27 sites where Miller[17] has shown 92.15% of root coverage in 79 sites. Pini-Prato et al.,[38] in their retrospective study, had observed 25.5% and 13.5% of CRC in the absence and presence of non-carious cervical lesion when treated with FGG, respectively.

Some authors when assessed the purpose of FGG for increasing the width of attached gingiva, also noticed improvement in the recession depth.[39,40] Ward[18] noted a remarkable reduction in the amount of recession in the two-thirds of the cases when FGG was used in the management of localized area of recession defects associated with frenal pull. Graft stabilization with different methods has shown to have no significant improvements in clinical parameters when compared to sutures. However, the surgical time was reduced by 40% compared to the conventional method.[41]

Changes in the other parameters

Great reduction was seen in the RD in the studies. PD reduction was statistically significant in three studies where there was no difference throughout in the PD in one study. An increase in WKG was reported in all the studies. However, Tolmie et al.[16] have presented with insufficiency in the study parameters.

In light of clinical evaluation of soft and hard periodontal tissues, PD Miller in 1985, gave a classification for gingival recession and also proposed prognosis for root-coverage outcome following FGG technique based on the gingival recession classification.[42] However, patient-related (e.g., smoking, palate vault depth, patient compliance), tooth/site-related (e.g., depth and width of baseline recession, presence or absence of cervical lesions), and procedure-related (e.g., presence or absence of releasing incisions) prognostic factors and the surgeon's skill can impact the root coverage which contradict the root-coverage predictability given by PD Miller.[43]

The studies conducted by the diversity of clinicians on Miller Class I and Class II gingival recession with FGG has presented with different results. Considering all the seven studies, four studies were in favor of FGG out of seven studies. The reason could be attributed to the case selection and the technique performed. Kuru and Yıldırım[31] have obtained a significant root coverage with conventional FGG technique. More studies are required to assess the efficacy of gingival unit graft. Therefore, it can be concluded that the use of FGG with proper case selection can produce substantial results.

Limitations

First, screening may not be comprehensive due to constrained availability

Sample size was small in a few studies having potential to affect the statistical power of analysis

Only one study was at lower inclination of bias

Absence of histologic examination which could have been more noteworthy in deciding the efficacy of the FGG

Lack of longer follow-up periods in some studies to assess creeping attachment in the outcome of FGG.

CONCLUSION

FGG produces substantial results and shows improvements in the recession depth, probing depth, CAL and width of keratinized gingiva. Its outcome highly depends on the case selection based on the patient-related and tooth/site-related factors, technical factors, and operator's skill and experience. The FGG gives an impression of being the best treatment option in zones where the gingival recession is present with inadequate width of attached gingiva and vestibular depth.

Future implications

Studies involving RCT fulfilling CONSORT guidelines are recommended

RW should be included as a clinical parameter in all the studies as the width of the recession acts as an important criterion in the success of the graft

More studies with longer period of follow-ups are needed

Multicenter studies with large sample size are essential to achieve adequate statistical analysis

Studies should perform histologic analysis for determining the efficacy of the FGG.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borghetti A, Gardella JP. Thick gingival autograft for the coverage of gingival recession: A clinical evaluation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1990;10:216–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spahr A, Haegewald S, Tsoulfidou F, Rompola E, Heijl L, Bernimoulin JP, et al. Coverage of miller class I and II recession defects using enamel matrix proteins versus coronally advanced flap technique: A 2-year report. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1871–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Sanctis M, Zucchelli G. Coronally advanced flap: A modified surgical approach for isolated recession-type defects: Three-year results. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:262–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smukler H. Laterally positioned mucoperiosteal pedicle grafts in the treatment of denuded roots. A clinical and statistical study. J Periodontol. 1976;47:590–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.10.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch A, Goldstein M, Goultschin J, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. A 2-year follow-up of root coverage using sub-pedicle acellular dermal matrix allografts and subepithelial connective tissue autografts. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1323–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.8.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wennström JL. Commentary: Treatment of periodontitis: Effectively managing mucogingival defects. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1639–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zucchelli G, Mounssif I, Mazzotti C, Montebugnoli L, Sangiorgi M, Mele M, et al. Does the dimension of the graft influence patient morbidity and root coverage outcomes? A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:708–16. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambrone L, Tatakis DN. Periodontal soft tissue root coverage procedures: A systematic review from the AAP regeneration workshop. J Periodontol. 2015;86:S8–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.130674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holbrook T, Ochsenbein C. Complete coverage of the denuded root surface with a one-stage gingival graft. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1983;3:8–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairo F, Nieri M, Pagliaro U. Efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures in the treatment of localized facial gingival recessions. A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(Suppl 15):S44–62. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairo F, Pagliaro U, Nieri M. Treatment of gingival recession with coronally advanced flap procedures: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:136–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonetti MS, Jepsen S. Working Group 2 of the European Workshop on Periodontology. Clinical efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures: Consensus report of group 2 of the 10th European workshop on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(Suppl 15):S36–43. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambrone L, Chambrone D, Pustiglioni FE, Chambrone LA, Lima LA. Can subepithelial connective tissue grafts be considered the gold standard procedure in the treatment of miller class I and II recession-type defects? J Dent. 2008;36:659–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaher CA, Hachem J, Puhan MA, Mombelli A. Interest in periodontology and preferences for treatment of localized gingival recessions. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:375–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2005.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan HC, Atkins JH. Free autogenous gingival grafts 3. Utilization of grafts in the treatment of gingival recession. Periodontics. 1968;6:152–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolmie PN, Rubins RP, Buck GS, Vagianos V, Lanz JC. The predictability of root coverage by way of free gingival autografts and citric acid application: An evaluation by multiple clinicians. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1991;11:261–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller PD., Jr Root coverage using the free soft tissue autograft following citric acid application. III. A successful and predictable procedure in areas of deep-wide recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:14–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward VJ. A clinical assessment of the use of the free gingival graft for correcting localized recession associated with frenal pull. J Periodontol. 1974;45:78–83. doi: 10.1902/jop.1974.45.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matter J, Cimasoni G. Creeping attachment after free gingival grafts. J Periodontol. 1976;47:574–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.10.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matter J. Creeping attachment of free gingival grafts. A five-year follow-up study. J Periodontol. 1980;51:681–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1980.51.12.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollack RP. Bilateral creeping attachment using free mucosal grafts. A case report with 4-year follow-up. J Periodontol. 1984;55:670–2. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.11.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris RJ. Creeping attachment associated with the connective tissue with partial-thickness double pedicle graft. J Periodontol. 1997;68:890–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.9.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otero-Cagide FJ, Otero-Cagide MF. Unique creeping attachment after autogenous gingival grafting: Case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:432–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rateitschak KH, Egli U, Fringeli G. Recession: A 4-year longitudinal study after free gingival grafts. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:158–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camargo PM, Melnick PR, Kenney EB. The use of free gingival grafts for aesthetic purposes. Periodontol 2000. 2001;27:72–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.027001072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brackett RC, Gargiulo AW. Free gingival grafts in humans. J Periodontol. 1970;41:581–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.10.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mörmann W, Schaer F, Firestone AR. The relationship between success of free gingival grafts and transplant thickness. Revascularization and shrinkage – A one year clinical study. J Periodontol. 1981;52:74–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wara-aswapati N, Pitiphat W, Chandrapho N, Rattanayatikul C, Karimbux N. Thickness of palatal masticatory mucosa associated with age. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1407–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oates TW, Robinson M, Gunsolley JC. Surgical therapies for the treatment of gingival recession. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:303–20. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1. 2008. Sep, [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 15]. p. 195. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org .

- 31.Kuru B, Yıldırım S. Treatment of localized gingival recessions using gingival unit grafts: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:41–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jahnke PV, Sandifer JB, Gher ME, Gray JL, Richardson AC. Thick free gingival and connective tissue autografts for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1993;64:315–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paolantonio M, di Murro C, Cattabriga A, Cattabriga M. Subpedicle connective tissue graft versus free gingival graft in the coverage of exposed root surfaces. A 5-year clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:51–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito K, Oshio K, Shiomi N, Murai S. A preliminary comparative study of the guided tissue regeneration and free gingival graft procedures for adjacent facial root coverage. Quintessence Int. 2000;31:319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenabian N, Bahabadi MY, Bijani A, Rad MR. Gingival unit graft versus free gingival graft for treatment of gingival recession: A Randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dent (Tehran) 2016;13:184–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mlinek A, Smukler H, Buchner A. The use of free gingival grafts for the coverage of denuded roots. J Periodontol. 1973;44:248–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.4.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michaelides PL, Wilson SG. An autogenous gingival graft technique. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14:112–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pini-Prato G, Magnani C, Zaheer F, Rotundo R, Buti J. Influence of inter-dental tissues and root surface condition on complete root coverage following treatment of gingival recessions: A 1-year retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:567–74. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy JE, Bird WC, Palcanis KG, Dorfman HS. A longitudinal evaluation of varying widths of attached gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:667–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorfman HS, Kennedy JE, Bird WC. Longitudinal evaluation of free autogenous gingival grafts. A four year report. J Periodontol. 1982;53:349–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.6.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaeger U, Andreoni C, Kopp FR, Strub JR. Sutures vs. Adhesives: Two fixation methods for free gingival grafts. A six-year follow-up study. Quintessence Int. 1987;18:691–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller PD., Jr A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pini-Prato G. The miller classification of gingival recession: Limits and drawbacks. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:243–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]