Abstract

Background

The phytopathogenic bacterium Xylella fastidiosa was thought to be restricted to the Americas where it infects and kills numerous hosts. Its detection worldwide has been blooming since 2013 in Europe and Asia. Genetically diverse, this species is divided into six subspecies but genetic traits governing this classification are poorly understood.

Results

SkIf (Specific k-mers Identification) was designed and exploited for comparative genomics on a dataset of 46 X. fastidiosa genomes, including seven newly sequenced individuals. It was helpful to quickly check the synonymy between strains from different collections. SkIf identified specific SNPs within 16S rRNA sequences that can be employed for predicting the distribution of Xylella through data mining. Applied to inter- and intra-subspecies analyses, it identified specific k-mers in genes affiliated to differential gene ontologies. Chemotaxis-related genes more prevalently possess specific k-mers in genomes from subspecies fastidiosa, morus and sandyi taken as a whole group. In the subspecies pauca increased abundance of specific k-mers was found in genes associated with the bacterial cell wall/envelope/plasma membrane. Most often, the k-mer specificity occurred in core genes with non-synonymous SNPs in their sequences in genomes of the other subspecies, suggesting putative impact in the protein functions. The presence of two integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) was identified, one chromosomic and an entire plasmid in a single strain of X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca. Finally, a revised taxonomy of X. fastidiosa into three major clades defined by the subspecies pauca (clade I), multiplex (clade II) and the combination of fastidiosa, morus and sandyi (clade III) was strongly supported by k-mers specifically associated with these subspecies.

Conclusions

SkIf is a robust and rapid software, freely available, that can be dedicated to the comparison of sequence datasets and is applicable to any field of research. Applied to X. fastidiosa, an emerging pathogen in Europe, it provided an important resource to mine for identifying genetic markers of subspecies to optimize the strategies attempted to limit the pathogen dissemination in novel areas.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-019-5565-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 16S rRNA gene, Horizontal gene transfer, Phylogeny, K-mer, SkIf, Taxonomy

Background

Xylella fastidiosa is a species of plant pathogenic bacteria endemic in the Americas, but listed as quarantine pests elsewhere (https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/XYLEFA/categorization). However, since 2013, various cases of emergences have been reported in Europe (Italy, France, Germany and Spain) on large ranges of host plants including olive trees, grapevine, and ornamentals [1–5]. In Italy, assuming that X. fastidiosa started spreading in 2010, a recent model approach suggested that it will progress through olive orchards to infect the northernmost recorded orchards within 43.5 years [6]. In France, bacterial introduction was estimated between 1985 and 2001, depending on the modeled scenarios [7, 8]. Several records of X. fastidiosa in imported materials (i.e. mostly coffee plants) were also reported over the same period in Europe [9–12].

X. fastidiosa is a genetically diverse species that is currently divided into six subspecies (subsp. fastidiosa, pauca, multiplex, sandyi, morus, tashke), the four-first being the most damaging and now being found in numerous countries worldwide. But the genetic diversity of the genus Xylella is undoubtedly underestimated. Yet another species, X. taiwanensis, was recently proposed for the strains causing leaf scorch on nashi pear tree, a disease that was reported more than 25 years ago in Taiwan and initially thought to be caused by a X. fastidiosa strain [13]. Recombination is known to drive X. fastidiosa evolution and adaptation to novel hosts [11, 14–16]. For example, the subspecies morus has been proposed for grouping strains issued from large events of intersubspecific recombination that were associated with a host shift [16]. The recent outbreaks and interception of imported, contaminated materials in Europe as well as investigations in South America also revealed the existence of previously unknown Sequence Types of several X. fastidiosa subspecies [2, 9, 11, 17, 18].

Because management and regulations of X. fastidiosa outbreaks in France depends on the subspecies of X. fastidiosa, it is of major importance to precisely define these subspecies, understand the robustness of these groupings and their meaning in terms of specific or shared genetic material. One way to resolve such a series of interrogations is the achievement of comparative genomics to identify similarities and specificities between groups of individuals. Yet, exploring big datasets is not trivial and requires dedicated bioinformatic tools to be cost- and time-effective. Various applications use k-mers mostly to analyze sequence reads to improve the quality of genome, transcriptome and metagenome assembly [19–26]. K-mer are all the possible substrings of length k that are contained in a nucleotide character string. K-mer-based methods can also be employed on whole genome sequences to taxonomically assign organisms [27, 28]. Moreover, several tools were developed to calculate pairwise relationships, like the average nucleotide identities using blast (ANIb) or MUMmer (ANIm) algorithms, and the tetranucleotide frequency correlation coefficients (TETRA), which can be accessed online through JSpecies [29] or with workstation installation of python3 pyani module [30].

Here, we developed SkIf (Specific k-mers Identification) and applied it to gain a better understanding of X. fastidiosa clustering in subspecies through the detection of genomic regions specifically associated with X. fastidiosa subspecies. We also used this tool to identify specific k-mers within 16S rRNA gene and assess the occurrences of X. fastidiosa in the SILVA database as a first attempt to mine large databases to evaluate the worldwide dispersion of X. fastidiosa subspecies.

Results

The genome sequence dataset

The dataset used in this study gathered 47 Xylella genomes sequences, including 46 X. fastidiosa and one X. taiwanensis specimen (Table 1). The X. fastidiosa subspecies tashke could not be included as no strain or genome sequence are available. In some analyses, the three strains belonging to X. fastidiosa subsp. sandyi were separated into two groups, containing either the original strain Ann-1 (sandyi) or the more recently discovered relatives CO33 and CFBP 8356 (sandyi-like) both belonging to the unusual sandyi ST72 [17]. The CFBP 8073 strain, described as an atypical X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa strain [11] was either included or not for analyses of this subspecies. The X. fastidiosa genome sequences involve 39 publicly available ones and seven newly individuals. The strains sequenced in this work were selected based on their country of isolation, genetic diversity and host range, inferred from their belonging to the subspecies fastidiosa (CFBP 7969, CFBP 7970, CFBP 8071, CFBP 8082, and CFBP 8351), sandyi (CFBP 8356) and multiplex (CFBP 8078). Genome sequence characteristics are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

List of the 47 Xylella genome sequences used in this study

| Genotype | Strain | STa | Host plant | Country (year)b | Accession number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X. fastidiosa | ATCC 35879 | 2 | Vitis vinifera | FL, USA (1987) | NZ_JQAP00000000 | Unpublished |

| subsp. | DSM 10026 | 2 | Vitis vinifera | FL, USA (1987) | NZ_FQWN01000006 | Unpublished |

| fastidiosa | CFBP 7969 | 2 | Vitis rotundifolia | NC, USA (1985) | PHFQ00000000 | This study |

| CFBP 7970 | 2 | Vitis vinifera | FL, USA (1987) | PHFR00000000 | This study | |

| CFBP 8071 | 1 | Prunus dulcis | CA, USA (1987) | PHFP00000000 | This study | |

| CFBP 8073 | 75 | Coffea canephora | Mexico (2012) | LKES00000000 | [11] | |

| CFBP 8082 | 2 | Ambrosia artemifolia | FL, USA (1983) | PHFT00000000 | This study | |

| CFBP 8351 | 1 | Vitis sp. | CA, USA (1993) | PHFU00000000 | This study | |

| EB92–1 | 1 | Sambucus nigra | FL, USA (1992) | AFDJ00000000 | [67] | |

| GB514 | 1 | Vitis vinifera | TX, USA (2007) | NC_017562 | [68] | |

| M23 | 1 | Prunus dulcis | CA, USA (2003) | NC_010577 | [69] | |

| Stag’s Leap | 1 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA (1994) | LSMJ010000 | [70] | |

| Temecula1 | 1 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA 1998) | NC_004556 | [58] | |

| X. f. subsp. | ATCC 35871 | 41 | Prunus salicina | CA, USA (1983) | NZ_AUAJ00000000 | Unpublished |

| multiplex | BB01 | 42 | Vaccinium corymbosum | GA, USA (2016) | NZ_MPAZ01000000 | [71] |

| CFBP 8078 | 51 | Vinca sp. | FL, USA (1983) | PHFS00000000 | This study | |

| CFBP 8416 | 7 | Polygala myrtifolia | COR, FR (2015) | LUYC00000000 | [2] | |

| CFBP 8417 | 6 | Spartium junceum | COR, FR (2015) | LUYB00000000 | [2] | |

| CFBP 8418 | 6 | Spartium junceum | COR, FR (2015) | LUYA00000000 | [2] | |

| Dixon | 6 | Prunus dulcis | CA, USA (1994) | AAAL00000000 | [72] | |

| Griffin-1 | 7 | Quercus rubra | GA, USA (2006) | AVGA00000000 | [73] | |

| M12 | 7 | Prunus dulcis | CA, USA (2003) | NC_010513 | [69] | |

| Sy-VA | 8 | Platanus occidentalis | VA, USA (2002) | JMHP00000000 | [74] | |

| X. f. subsp. | Ann-1 | 5 | Nerium oleander | CA, USA (1995) | CP006696 | [75] |

| sandyi | CFBP 8356 | 72 | Coffea arabica | Costa Rica (2015) | PHFV00000000 | This study |

| Co33 | 72 | Coffea arabica | Costa Rica (2014) | LJZW00000000 | [76] | |

| X. f. subsp. | Mul0034 | 30 | Morus alba | USA (2003) | CP006740 | [77] |

| morus | Mul-MD | 29 | Morus alba | MD, USA (2011) | AXDP00000000 | [77] |

| X. f. subsp. | 32 | 16 | Coffea arabica | Brazil (1997) | AWYH00000000 | [78] |

| pauca | 3124 | 16 | Coffea sp. | Brazil (2009) | CP009829 | Unpublished |

| 11,399 | 12 | Citrus cinensis | Brazil (1996) | NZ_JNBT01000030 | [79] | |

| 6c | 14 | Coffea arabica | Brazil (1997) | AXBS00000000 | [78] | |

| 9a5c | 13 | Citrus cinensis | Brazil (1992) | NC_002488 | [57] | |

| CFBP 8072 | 74 | Coffea Arabica | Ecuador (2012) | LKDK00000000 | [11] | |

| CoDiRO | 53 | Catharanthus roseus c | Italy (2013) | JUJW00000000 | [33] | |

| COF0324 | 14 | Coffea sp. | Costa Rica (2006) | LRVG01000000 | Unpublished | |

| COF0407 | 53 | Coffea sp. | Costa Rica (2009) | LRVJ00000000 | Unpublished | |

| CVC0251 | 12 | Citrus cinensis | Brazil (1999) | LRVE01000000 | Unpublished | |

| CVC0256 | 12 | Citrus cinensis | Brazil (1999) | LRVF01000000 | Unpublished | |

| Fb7 | 69 | Citrus sinensis | Argentina (1998) | CP010051 | Unpublished | |

| Hib4 | 70 | Hibiscus fragilis | Brazil (2000) | CP009885 | Unpublished | |

| J1a12 | 12 | Citrus sp. | Brazil (2001) | CP009823 | Unpublished | |

| OLS0478 | 53 | Nerium oleander | Costa Rica (2010) | LRVI00000000 | Unpublished | |

| OLS0479 | 53 | Nerium oleander | Costa Rica (2010) | LRVH00000000 | Unpublished | |

| Pr8x | 14 | Prunus (Plum) | Brazil (2009) | CP009826 | Unpublished | |

| U24D | 13 | Citrus sinensis | Brazil (2000) | CP009790 | Unpublished | |

| X. taiwanensis | PLS 229 | – | Pyrus pyrifolia | Taiwan (−) | JDSQ00000000 | [80] |

aSequence Type determined following the MSLT scheme dedicated to X. fastidiosa [52]

bExact year of isolation or oldest year of literature citing the stain

cDNA was recovered from infected periwinkle. This genome is the one of the CoDiRO strain, the agent responsible for the Olive Quick Decline Syndrome in Italy (46)

Table 2.

List of Xylella fastidiosa strains sequenced for this study and genome properties

| Strain | Accession | Nb of readsa | Cover.b | Assemby size (bp) | Nb contigsc | N50 | Mean size (bp) | Largest (bp) | GC % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFBP 7969 | PHFQ00000000 | 7,952,452 | 957x | 2,436,752 | 89 | 116,341 | 27,379 | 445,308 | 51.48 |

| CFBP 7970 | PHFR00000000 | 8,041,300 | 968x | 2,493,794 | 93 | 104,928 | 26,815 | 258,911 | 51.45 |

| CFBP 8071 | PHFP00000000 | 7,606,748 | 916x | 2,489,737 | 101 | 104,990 | 24,651 | 297,538 | 51.48 |

| CFBP 8082 | PHFT00000000 | 7,610,344 | 916x | 2,532,132 | 118 | 104,927 | 21,459 | 301,313 | 51.51 |

| CFBP 8351 | PHFU00000000 | 8,741,758 | 1053x | 2,479,202 | 93 | 104,608 | 26,658 | 266,361 | 51.45 |

| CFBP 8078 | PHFS00000000 | 8,807,962 | 1060x | 2,602,010 | 191 | 87,559 | 13,623 | 204,167 | 51.67 |

| CFBP 8356 | PHFV00000000 | 8,088,406 | 974x | 2,541,621 | 197 | 93,086 | 12,902 | 190,454 | 51.58 |

apair-end (301 bp)

bCoverage calculated for a mean genome of 2.5 Mb

cLarger than 500 bp

Evaluation of strain synonymy using k-mers

CFBP 7970, the X. fastidiosa and X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa type strain [31], has various synonymous names (ATCC 35879, DSM 10026, LMG17159, http://www.straininfo.net/strains/901514 or http://www.bacterio.net/xylella.html) in other collections, as a result of strain exchanges between the American (ATCC), German (DSMZ), Belgian (LMG), and French (CIRM-CFBP) collections [32]. As no genome sequences were available at the beginning of this study for any of these strains, CFBP 7970 was included in our dataset and its genome was sequenced. Later on, the genome sequences of the strains ATCC 35879 and DSM 10026 were released. Although the genome sequences of the three strains were very similar (99.83–99.97% ANIb), they were not strictly identical (Additional file 1). The use of SkIf identified DNA fragments that were specific to two genome sequences, but absent in the third one, yielding in 95, 192, and 594 k-mers specifically present in the pairs ATCC 35879/DSM 10026, CFBP 7970/DSM 10026, ATCC 35879/CFBP 7970, respectively (Additional file 2). The absence of some mers in genome sequence could be due to sequencing artefacts (e.g. sequencing technology employed, average coverage and assembly methods) that resulted in specific SNPs (Table 3). However, 16 mers (ranging from 29 to 9,178 nt and totalizing 36,845 bp in size) were detected in a single contig (41,458 bp) in CFBP 7970 and into several DSM 10026 contigs but were absent from ATCC 35879 genome sequence (Additional file 2). These sequences shared high identity levels with a plasmid found in multiple Xylella subspecies, known as pXF-De Donno (subsp. pauca De Donno strain), pXF-RIV5 (subsp. multiplex RIV5 strain), pXF-FAS01 (subsp. fastidiosa M23 strain) or present but unnamed elsewhere (like in subsp. pauca CoDiRO strain and subsp. multiplex Dixon strain) [2, 33–35]. But the blast analysis suggested its possible presence, as partial matches (3.8 -6 kb in total) with high but not perfect identity levels (95–99%) were found when searched against the genome sequence of ATCC 35879 (Additional file 2; Additional file 3).

Table 3.

Properties of genome sequences of strains CFBP 7970, DSM 10026 and ATCC 35879

| CFBP 7970a | DSM 10026b | ATCC 35879c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing technology | Ilumina MiSeq | Shot gun | Illumina MiSeq |

| Assembling method | Velvet SOAPdenovo SOAPGapCloser |

Not available | CLC Genomic Workbench |

| Genome size | 2,493,794 bp | 2,426,538 bp | 2,522,328 bp |

| Number of contigs | 93 | 72 | 16 |

| Minimal size of contigs | 500 bp | 1 kb | 1.2 kb |

| Coverage | 968x | 416x | 1380x |

a Data from the present study

b More details at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/173?genome_assembly_id=295121

c More details at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/173?genome_assembly_id=212014

Data mining of the 16S rRNA SILVA database to assign occurrences of Xylella sp.

The availability of the 47 Xylella genome sequences renders possible the analysis of the allelic diversity of the 16S rRNA marker gene. This housekeeping marker is widely used in bacterial phylogeny and taxonomy studies for various reasons including its vertical inheritance and ubiquity in prokaryotes. It is also commonly used to survey microbial communities and as such is a marker to survey largely the environment. A total of 74 16S rRNA gene sequences was retrieved from our dataset, these either being present in one (n = 20) or two copies (n = 27) in X. fastidiosa and X. taiwanensis (Table 4). We detected 19 SNPs (over 1547 nucleotides, 1.22%) specific to X. taiwanensis PLS 229 16S rRNA (Additional file 4).

Table 4.

Repertoire of 16S rRNA gene sequences in 47 genomes of Xylella sp

| Xylella genomes (total; with 1 copy; with 2 copies) | Codes of strains having one copy of 16S rRNA | Codes of strains having two copies of 16S rRNA |

|---|---|---|

| X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa (n = 13;3;10) | EB92–1, CFBP 8073, CFBP 8351 | ATCC 35879, CFBP 7969, CFBP 7970, CFBP 8071, CFBP 8082, DSM10026, GB514, M23, Stag’s Leap, Temecula1 |

| X. fastidiosa subsp. multiplex (n = 10;8;2) | ATCC 35871, BB01, CFBP 8078, CFBP 8417, CFBP 8418, Dixon, Griffin-1, Sy-VA | CFBP 8416, M12 |

| X. fastidiosa subsp. morus(n = 2;1;1) | Mul-MD | Mul0034 |

| X. fastidiosa subsp. sandyi (n = 3;1;2) | CFBP 8356 | Ann-1, CO33 |

| X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca (n = 18;6;12) | CFBP 8072, COF0324, COF0407, OLS0479, Xf6c, Xf32 | 11,399, 3124, 9a5c, CoDiRO, CVC0251, CVC0256, Fb7, Hib4, J1a12, OLS0478, Pr8x, U24D |

| X. taiwanensis (n = 1;1;0) | PLS 229 | – |

Specific mers were searched for within the Xylella genus (i.e., the in-group included the 74 Xylella 16S rRNA copies; the out-group included all the SSU sequences from the Silva database other than Xylella-tagged) and the X. fastidiosa species (i.e., the genome sequence of X. taiwanensis PLS 229 strain was included in the out-group). Five long-mers (referred to as LongXyl#1 to #5) specific to Xylella genus and four long-mers (referred to as LongXylefa#1 to #4) specific to the X. fastidiosa species were identified. LongXyl (23-43 nt) and LongXylefa (23-31 nt) mers located between positions 212 and 866, and positions 202 and 1013, respectively, which include the V3-V4 hypervariable regions widely used in community profiling approaches (Additional file 5). Specific signatures obtained from eight nucleotide positions in the 16S rRNA alignment discriminated alleles from X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa, multiplex, morus, sandyi and pauca (Table 5).

Table 5.

Specific signatures in 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences to discriminate X. fastidiosa subspecies

| X. fastidiosa subsp. (nb of genome sequences) | SNPs at the designed positionsa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75a | 76 | 151 | 455 | 474 | 1127 | 1264 | 1340 | |

| fastidiosa (n = 13) | C | A | C | G | – | G | A | C |

| morus (n = 2) | C | A | C | G | – | T | A | C |

| multiplex (n = 10) | C | A | T | A | – | G | G | C |

| sandyi (n = 1)b | C | A | T | A | T | G | A | C |

| sandyi-like (n = 2)c | T | A | C | A | – | G | G | C |

| pauca (n = 18) | C | G | T | A | – | G | A | T |

arefers to SNP positions within the alignment of the copies of 16S rRNA (Additional file 4)

brefers to Ann-1strain only

crefers to strains CFBP 8356 and CO33 strains

The occurrence of these specific mers in 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences was investigated within the SILVA rRNA database (Additional file 4). A large proportion of the sequences retrieved from the SILVA database (n = 118/195) covered less than half of the total gene length, and only a minority (n = 70/195) covered at least three fourth of the length. After nucleotide alignment, 53 of these sequences including the LongXyl and LongXylefa specific signatures were retained (Additional file 4). Based on their genetic signatures, 51 sequences were assigned to subsp. multiplex (n = 32), fastidiosa (n = 11), pauca (n = 5), sandyi (n = 2) and morus (n = 1), while two sequences (EU560720.1 and EU560722.1) could not be assigned because they did not cover most of the eight discriminant nucleotide positions (Additional file 5). The validity of this presumptive taxonomic affiliation was consolidated by the description of the sample, which were in adequacy with the current host range of these subspecies. Indeed, samples from subsp. fastidiosa mainly come from alfalfa or grapevine, while those from subsp. multiplex were collected on various oak species, those from subsp. sandyi were isolated from oleander, those from subsp. pauca from periwinkle, coffee or olive trees, and the one from subsp. morus came from mulberry.

Identification of allelic variants specific to each X. fastidiosa subspecies

Beyond focusing on a single gene (16S rRNA), we applied SkIf to a whole genome-based analysis. Seven groups of strains were defined: fastidiosa (two groups), pauca, multiplex, morus and sandyi (two groups). The two fastidiosa groups differed by the presence/absence of the strain CFBP 8073, while one sandyi group included only the original member Ann-1, and the sandyi-like group included only CFBP 8356 and CO33 strains. Specific mers were searched for in each group against all the others.

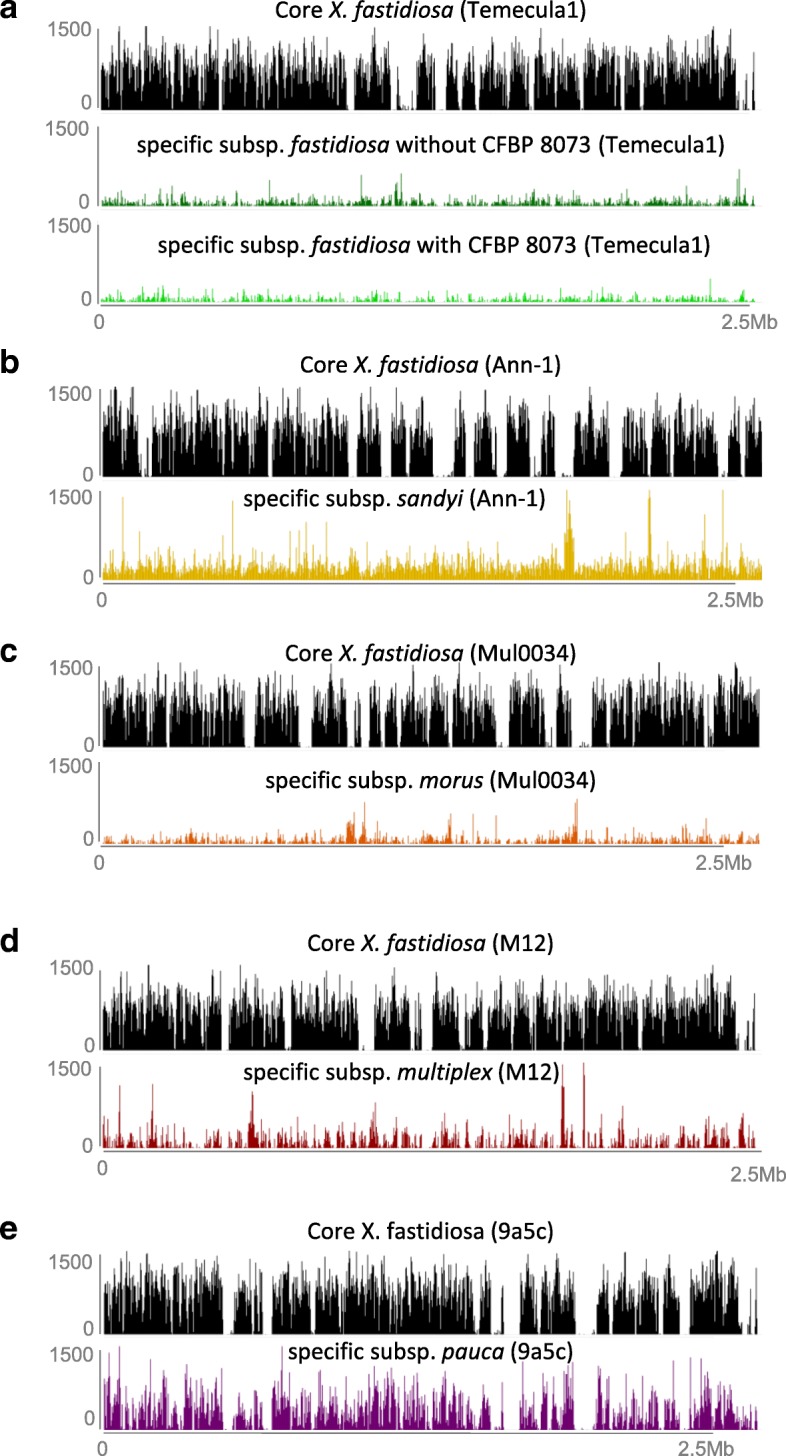

Overall, long-mers were identified all along the genomes (Fig. 1), mainly matching coding sequences (71–80% depending on the subspecies), with one to several long-mers in the identified CDS (Table 6A; Additional file 6). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed by comparing the predicted functions associated with these specific CDSs to the overall predicted proteomes. Fischer’s exact test revealed multiple GO terms over- (mostly) or under- (rarely) represented for the seven groups. Overall, only one GO term (catalytic activity) was always found enriched, except for the subspecies morus, while 10 other GO terms were found enriched in all groups except in subspecies morus and sandyi (Table 7; Additional file 7; Fig. 2). Several GO terms were only identified in a single subspecies (Table 8), suggesting that associated mechanisms might be key markers of X. fastidiosa subspecies evolution. As for subspecies pauca it concerned 175 GO terms, including 20 terms associated with the bacterial cell wall/envelope/plasma membrane and 16 related to nucleotide metabolic/biosynthetic process, especially for purine, as well as 4 terms under-represented dealing with viral or symbiont processes. As for subspecies fastidiosa (without CFBP 8073) it concerned six GO terms related to DNA modification and vitamin process. The subspecies multiplex specific GO terms deal with metabolic process, catalytic activity and conformation of DNA and organelle organization. The subspecies morus had only one ontology enriched, associated with DNA replication.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of k-mers along the X. fastidiosa genome sequences. Frequency of core (black) and specific (colored) k-mers mapped onto the genome of reference (mentioned into brackets) of each subspecies. a subsp. fastidiosa with or without CFBP 8073 strain. b subsp. sandyi. c subsp. morus. d subsp. multiplex. e subsp. pauca

Table 6.

Main features related to the specific mers identified in X. fastidiosa subspecies

| A. X. fastidiosa subspecies | FAS1 | FAS21 | SAN1 | SAN21 | MOR1 | MUL1 | PAU1 | |

| number of mers | 2905 | 1978 | 9808 | 5765 | 3094 | 4906 | 11,365 | |

| number of unique mers | 2836 | 1957 | 9431 | 5636 | 2995 | 4813 | 11,162 | |

| total mer size (bp) | 133,179 | 85,038 | 518,683 | 292,740 | 142,614 | 258,228 | 627,685 | |

| number of mers in CDS | 2172 | 1411 | 7783 | 4161 | 2341 | 3603 | 9088 | |

| number of unique CDS | 1142 | 811 | 2406 | 1646 | 1115 | 1119 | 1711 | |

| total mer size in CDS (bp) | 100,015 | 60,092 | 414,736 | 215,901 | 108,336 | 189,973 | 504,054 | |

| number of mers in intergenic regions | 733 | 567 | 2025 | 1604 | 753 | 1303 | 2277 | |

| total mer size in intergenic regions (bp) | 33,164 | 24,946 | 103,947 | 76,839 | 34,278 | 68,255 | 123,631 | |

| B. Combination morus + other subspecies | MOR-FAS1 | MOR-FAS21 | MOR-SAN1 | MOR-SAN21 | MOR-SAN-SAN21 | MOR-SAN-SAN2-FAS21 | MOR-MUL1 | MOR-PAU1 |

| number of mers | 495 | 1236 | 352 | 371 | 237 | 3389 | 2131 | 71 |

| number of unique mers | 491 | 1222 | 347 | 358 | 235 | 3369 | 2072 | 71 |

| total mer size (bp) | 20,058 | 53,052 | 13,123 | 14,066 | 8019 | 136,470 | 98,450 | 2377 |

| number of mers in CDS | 331 | 825 | 258 | 243 | 116 | 2367 | 1638 | 58 |

| number of unique CDS | 216 | 430 | 192 | 178 | 103 | 806 | 572 | 41 |

| total mer size in CDS (bp) | 13,428 | 36,147 | 9816 | 9275 | 4249 | 96,946 | 76,167 | 2018 |

| number of mers in intergenic regions | 164 | 411 | 94 | 128 | 121 | 1022 | 493 | 13 |

| total mer size in intergenic regions (bp) | 6630 | 16,905 | 3307 | 4791 | 3770 | 39,524 | 22,283 | 359 |

| C. Within subspecies pauca | pauca I.11 | pauca I.21 | pauca I.31 | CFBP 80721 | Hib41 | |||

| number of mers | 1266 | 2360 | 3885 | 4775 | 4694 | |||

| number of unique mers | 1238 | 2323 | 3644 | 4663 | 4596 | |||

| total mer size (bp) | 59,733 | 121,367 | 207,098 | 283,540 | 341,563 | |||

| number of mers in CDS | 1003 | 1776 | 3194 | 3150 | 3338 | |||

| number of unique CDS | 486 | 716 | 1147 | 1205 | 1324 | |||

| total mer size in CDS (bp) | 47,655 | 92,528 | 173,936 | 194,240 | 269,888 | |||

| number of mers in intergenic regions | 263 | 584 | 690 | 1625 | 1356 | |||

| total mer size in intergenic regions (bp) | 12,078 | 28,839 | 33,162 | 89,300 | 71,675 | |||

1Composition of the groups:

MOR (subsp. morus): Mul-MD and Mul0034 (Reference: 2,666,577 bp). FAS (subsp. fastidiosa): ATCC 35879, DSM 10026, CFBP 7969, CFBP 7970, CFBP 8071, CFBP 8082, CFBP 8351, EB92–1, GB514, M23, Stag’s Leap and Temecula1 (Reference: 2,521,148 bp). FAS2 (subsp. fastidiosa): All the members of the group FAS (with Temecula1 as reference), plus CFBP 8073. MUL (subsp. multiplex): ATCC 35871, BB01, CFBP 8078, CFBP 8416, CFBP 8417, CFBP 8418, Dixon, Griffin-1, Sy-VA and M12 (Reference: 2,475,130 bp). SAN (subsp. sandyi): Ann-1 (Reference: 2,780,908 bp). SAN2 (subsp. sandyi-like): CFBP 8356 and CO33 (Reference: 2,416,985 bp). PAU (subsp. pauca): 32, 3124, 11,399, 6c, CFBP 8072, CoDiRO, COF0324, COF0407, CVC0251, CVC0256, Fb7, Hib4, J1a12, OLS0478, OLS0479, Pr8x, U24D and 9a5c (Reference: 2,731,750 bp). pauca I.1 (subsp. pauca): U24D, Fb7, CVC0251, CVC0256, J1a12, 11,399, 3124, 32 and 9a5c (Reference: 2,731,750 bp). pauca I.2 (subsp. pauca): 6c, COF0324 and Pr8x (Reference: 2,666,242 bp). pauca I.3 (subsp. pauca): COF0407, OLS0478, OLS0479 and CoDiRO (Reference: 2,542,932 bp). CFBP 8072 (subsp. pauca; 2,496,662 bp). Hib4 (subsp. pauca; 2,877,548 bp)

Table 7.

Main Gene Ontologies (GO) identified as enriched in almost all the subspecies for the CDS harboring specific mers

| GO term1 | Description | FAS2,3 | FAS22,3 | MUL2,3 | PAU2,3 | SAN2,3 | SAN22,3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0003824 | catalytic activity | 473/368 669/912 1.64e-7/7.48e-11 |

343/498 468/1113 4.79e-5/4.20e-8 |

358/308 761/935 0.0082/1.18e-4 |

672/143 1039/796 4.35e-37/3.55e-40 |

779/86 1627/311 0.0108/1.34e-5 |

630/229 1016/670 1.05e-7/4.37e-11 |

| GO:0000166 | nucleotide binding | 138/96 1004/1184 0.0246/1.46e-4 |

106/128 705/1483 0.0115/7.90e-5 |

143/90 976/1153 9.99e-4/8.70e-6 |

240/32 1471/907 2.40e-18/2.18e-20 |

– | 228/54 1418/845 2.30e-7/3.81e-10 |

| GO:0017076 | purine nucleotide binding | 109/73 1033/1207 0.0469/3.69e-4 |

87/95 724/1516 0.0077/3.91e-5 |

118/70 1001/1173 0.0012/1.25e-5 |

197/20 1514/919 4.04e-18/4.45e-20 |

– | 181/44 1465/855 2.08e-5/7.77e-8 |

| GO:0032553 | ribonucleotide binding | 114/74 1028/1206 0.0246/1.33e-4 |

89/99 722/1512 0.0086/5.12e-5 |

121/72 998/1171 0.0011/1.12e-5 |

203/23 1508/916 2.25e-17/2.67e-19 |

– | 186/48 1460/851 5.83e-5/2.89e-7 |

| GO:0032555 | purine ribonucleotide binding | 108/73 1034/1207 0.0469/4.80e-4 |

87/94 724/1517 0.0060/2.64e-5 |

117/70 1002/1173 0.0015/1.70e-5 |

197/19 1514/920 1.07e-18/8.34e-21 |

– | 181/44 1465/855 2.08e-5/7.77e-8 |

| GO:1901265 | nucleoside phosphate binding | 138/96 1004/1184 0.0246/1.46e-4 |

106/128 705/1483 0.0115/7.90e-5 |

143/90 976/1153 9.99e-4/8.70e-6 |

240/32 1471/907 2.40e-18/2.18e-20 |

– | 228/54 1418/845 2.30e-7/3.81e-10 |

| GO:0036094 | small molecule binding | 153/103 989/1177 0.0077/2.11e-5 |

114/142 697/1469 0.0142/1.10e-4 |

155/100 964/1143 8.42e-4/5.87e-6 |

266/33 1445/906 1.49e-21/6.68e-24 |

– | 251/62 1395/837 2.30e-7/2.82e-10 |

| GO:0043168 | anion binding | 140/87 1002/1193 0.0030/4.98e-6 |

102/125 709/1486 0.0206/2.07e-4 |

140/88 979/1155 0.0010/9.88e-6 |

242/27 1469/912 4.32e-21/2.11e-23 |

– | 226/59 1420/840 7.16e-6/1.77e-8 |

| GO:0097367 | carbohydrate derivative binding | 117/81 1025/1199 0.0469/4.68e-4 |

94/104 717/1507 0.0060/2.74e-5 |

126/73 993/1170 5.43e-4/2.60e-6 |

209/23 1502/916 2.40e-18/2.31e-20 |

– | 190/50 1456/849 7.27e-5/3.90e-7 |

| GO:0005488 | binding | 323/277 819/1003 0.0253/1.61e-4 |

247/353 564/1258 0.0020/5.52e-6 |

296/245 823/998 0.0078/1.06e-4 |

547/140 1164/799 1.14e-20/6.54e-23 |

– | 502/187 1144/712 3.03e-5/1.25e-7 |

| GO:0008152 | metabolic process | 465/411 677/869 0.0055/1.26e-5 |

355/521 456/1090 4.79e-5/4.37e-8 |

397/331 722/912 5.94e-4/3.44e-6 |

723/168 988/771 4.40e-36/5.38e-39 |

– | 644/264 1002/635 1.36e-4/7.91e-7 |

1Complete datasets are provided in Additional file 7

2Top line: number of GO-associated CDSs in the list of CDSs harboring specific mers (query) / number of GO-associated CDSs in the CDSs of reference genome that do not harbor specific mers. Middle line: number of non-annotated (no GOs) CDSs in the list of CDSs harboring specific mers (query) / number of non-annotated (no GOs) CDSs in the CDSs of reference genome that do not harbor specific mers. The addition of the four values in each column correspond to the total number of CDS of the reference genome. The addition of the numerator values corresponds to the number of CDS in the query list. The addition of the denominator values corresponds to the number of CDSs of the reference genome that are not in the list of CDSs harboring specific mers. Bottom line: FDR/ P-value

3Composition of the groups: FAS (subsp. fastidiosa, 12): ATCC 35879, DSM 10026, CFBP 7969, CFBP 7970, CFBP 8071, CFBP 8082, CFBP 8351, EB92–1, GB514, M23, Stag’s Leap, Temecula1. FAS2 (subsp. fastidiosa, 13): All the members of the group FAS, plus CFBP 8073. MUL (subsp. multiplex, 10): ATCC 35871, BB01, CFBP 8078, CFBP 8416, CFBP 8417, CFBP 8418, Dixon, Griffin-1, M12, Sy-VA. SAN (subsp. sandyi, 1): Ann-1. SAN2 (subsp. sandyi-like, 2): CO33 and CFBP 8356. PAU (subsp. pauca, 18): 32, 3124, 11,399, 6c, 9a5c, CFBP 8072, CoDiRO, COF0324, COF0407, CVC0251, CVC0256, Fb7, Hib4, J1a12, OLS0478, OLS0479, Pr8x, U24D

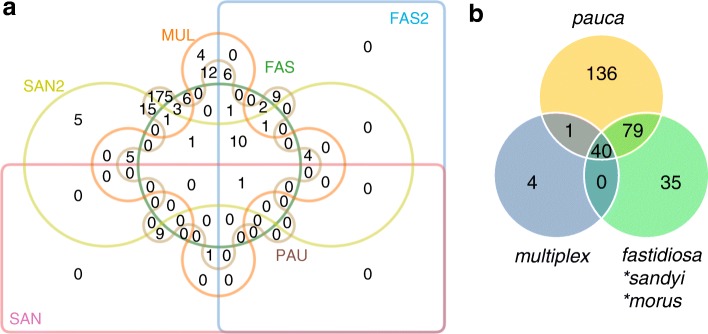

Fig. 2.

Overlap between gene ontologies differentially represented (over or under) in genes harboring specific k-mers. a Relationships between six groups: FAS and FAS2, subsp. fastidiosa without or with CFBP 8073, respectively; MUL, subsp. multiplex; SAN and SAN2, subsp. sandyi and sandyi-like, respectively; PAU, subsp. pauca. Note: the subsp. morus is not indicated on the Venn diagram as it was identified only one GO term, specific to it. b Relationships between three groups (pauca, multiplex and the third one resulting from the grouping of subsp. fastidiosa, sandyi and morus)

Table 8.

Selected differentially represented Gene Ontologies of CDS with specific mers in X. fastidiosa subspecies or subclades

| GO term1 | Description | FDR/p-value | Annot. test/ref2 | Non annot. Test/ref3 | Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific to subsp. pauca: associated with the bacterial cell wall/envelope/plasma membrane; nucleotide metabolic/biosynthetic process, especially for purine | |||||

| GO:0000270 | peptidoglycan metabolic process | 4.40e-36/5.38e-39 | 723/168 | 988/771 | over |

| GO:0000902 | cell morphogenesis | 4.21e-4/2.27e-5 | 25/0 | 1686/939 | over |

| GO:0005886 | plasma membrane | 0.0017/1.15e-4 | 96/23 | 1615/916 | over |

| GO:0009252 | peptidoglycan biosynthetic process | 0.0029/2.08e-4 | 20/0 | 1691/939 | over |

| GO:0009273 | peptidoglycan-based cell wall biogenesis | 0.0029/2.08e-4 | 20/0 | 1691/939 | over |

| GO:0009279 | cell outer membrane | 0.0346/0.0035 | 19/1 | 1692/938 | over |

| GO:0009653 | anatomical structure morphogenesis | 4.21e-4/2.272e-5 | 25/0 | 1686/939 | over |

| GO:0016021 | integral component of membrane | 0.0060/4.49e-4 | 292/112 | 1419/827 | over |

| GO:0019867 | outer membrane | 0.0458/0.0047 | 25/3 | 1686/936 | over |

| GO:0030312 | external encapsulating structure | 0.0088/7.40e-4 | 22/1 | 1689/938 | over |

| GO:0031224 | intrinsic component of membrane | 0.0049/3.68e-4 | 293/112 | 1418/827 | over |

| GO:0042546 | cell wall biogenesis | 0.0029/2.08e-4 | 20/0 | 1691/939 | over |

| GO:0044036 | cell wall macromolecule metabolic process | 0.0012/7.19e-5 | 23/0 | 1688/939 | over |

| GO:0044038 | cell wall macromolecule biosynthetic process | 0.0029/2.08e-4 | 20/0 | 1691/939 | over |

| GO:0044425 | membrane part | 0.0014/8.82eE-5 | 302/112 | 1409/827 | over |

| GO:0044462 | external encapsulating structure part | 0.0346/0.0035 | 19/1 | 1692/938 | over |

| GO:0045229 | external encapsulating structure organization | 0.0023/1.55e-4 | 26/1 | 1685/938 | over |

| GO:0048856 | anatomical structure development | 4.21e-4/2.27e-5 | 25/0 | 1686/939 | over |

| GO:0071554 | cell wall organization or biogenesis | 0.0094/7.93e-4 | 23/1 | 1688/938 | over |

| GO:0071555 | cell wall organization | 0.0346/0.0035 | 19/1 | 1692/938 | over |

| GO:0006164 | purine nucleotide biosynthetic process | 0.0079/6.34e-4 | 27/2 | 1684/937 | over |

| GO:0009127 | purine nucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process | 0.0088/7.40e-4 | 22/1 | 1689/938 | over |

| GO:0009144 | purine nucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.0035/2.62e-4 | 28/1 | 1686/938 | over |

| GO:0009152 | purine ribonucleotide biosynthetic process | 0.0122/0.0010 | 26/2 | 1685/937 | over |

| GO:0009168 | purine ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process | 0.0088/7.4042e-4 | 22/1 | 1689/938 | over |

| GO:0009205 | purine ribonucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.0035/2.6218e-4 | 25/1 | 1686/938 | over |

| GO:0072522 | purine-containing compound biosynthetic process | 0.0346/0.0034 | 18/1 | 1693/938 | over |

| GO:0072528 | pyrimidine-containing compound biosynthetic process | 0.0034/2.457e-4 | 29/2 | 1682/937 | over |

| GO:0009117 | nucleotide metabolic process | 0.0012/7.00e-5 | 64/11 | 1647/928 | over |

| GO:0009123 | nucleoside monophosphate metabolic process | 1.59e-5/5.71e-7 | 49/3 | 1662/936 | over |

| GO:0009124 | nucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process | 0.0014/8.89e-5 | 32/2 | 1679/937 | over |

| GO:0009141 | nucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.0034/2.45e-4 | 29/2 | 1682/937 | over |

| GO:0009156 | ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthetic process | 6.00e-4/3.25e-5 | 30/1 | 1681/938 | over |

| GO:0009165 | nucleotide biosynthetic process | 0.0106/8.96e-4 | 43/7 | 1668/932 | over |

| GO:0009199 | ribonucleoside triphosphate metabolic process | 0.0023/1.55e-4 | 26/1 | 1685/938 | over |

| GO:0009260 | ribonucleotide biosynthetic process | 6.15e-4/3.36e-5 | 35/2 | 1676/937 | over |

| GO:0016032 | viral process | 0.0213/0.0019 | 0/6 | 1711/933 | under |

| GO:0019058 | viral life cycle | 0.0213/0.0019 | 0/6 | 1711/933 | under |

| GO:0019068 | virion assembly | 0.0213/0.0019 | 0/6 | 1711/933 | under |

| GO:0044403 | Symbiont process | 0.0213/0.0019 | 0/6 | 1711/933 | under |

| Specific to subsp. fastidiosa (without CFBP 8073; group FAS): associated with DNA modification; vitamin process | |||||

| GO:0006304 | DNA modification | 0.0030/5.64e-6 | 16/0 | 1126/1280 | over |

| GO:0006305 | DNA alkylation | 0.0469/5.31e-4 | 10/0 | 1132/1280 | over |

| GO:0006306 | DNA methylation | 0.0469/5.31e-4 | 10/0 | 1132/1280 | over |

| GO:0044728 | DNA methylation or demethylation | 0.0469/5.31e-4 | 10/0 | 1132/1280 | over |

| GO:0009110 | vitamin biosynthetic process | 0.0469/5.56e-4 | 18/3 | 1124/1277 | over |

| GO:0042364 | water-soluble vitamin biosynthetic process | 0.0469/5.56e-4 | 18/3 | 1124/1277 | over |

| Specific to subsp. multiplex: associated with metabolic process, catalytic activity and conformation of DNA; organelle organization | |||||

| GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | 0.0021/2.52e-5 | 53/21 | 1066/1222 | over |

| GO:0071103 | DNA conformation change | 0.0324/5.80eE-4 | 13/1 | 1106/1242 | over |

| GO:0140097 | catalytic activity, acting on DNA | 0.0018/2.11eE-5 | 33/8 | 1086/1235 | over |

| GO:0006996 | organelle organization | 0.0256/4.47e-4 | 162 | 1103/1241 | over |

| Specific to subsp. morus: associated with DNA replication | |||||

| GO:0006260 | DNA replication | 0.0485/1.99e-5 | 31/10 | 1084/1491 | over |

| Specific to the combination of subsp. morus and multiplex: associated with amino acid biosynthetic processes; ion binding | |||||

| GO:1901607 | alpha-amino acid biosynthetic process | 0.0390/2.30e-4 | 26/35 | 546/2009 | over |

| Specific to the combination of subsp. morus, fastidiosa (including CFBP 8073), sandyi, sandyi-like (=clade III): associated with cellular component or protein complex disassembly; signaling; metabolic process; ATP generation; carbohydrates / polysaccharides; nucleoside/nucleotides; peptidyl-proline; response to chemical; tRNA binding; chemotaxis | |||||

| GO:0022411 | cellular component disassembly | 0.0168/8.44e-4 | 6/0 | 800/1810 | over |

| GO:0032984 | macromolecular complex disassembly | 0.0168/8.44e-4 | 6/0 | 800/1810 | over |

| GO:0043241 | protein complex disassembly | 0.0168/8.44e-4 | 6/0 | 800/1810 | over |

| GO:0023052 | signaling | 0.0496/0.0031 | 18/14 | 788/1796 | over |

| GO:0007165 | signal transduction | 0.0496/0.0031 | 18/14 | 788/1796 | over |

| GO:0006090 | pyruvate metabolic process | 0.0086/3.44e-4 | 13/5 | 793/1805 | over |

| GO:0006096 | glycolytic process | 0.0149/5.74e-4 | 17/10 | 789/1800 | over |

| GO:0006733 | oxidoreduction coenzyme metabolic process | 0.0343/0.0018 | 8/2 | 798/1808 | over |

| GO:0044264 | cellular polysaccharide metabolic process | 0.0149/7.01e-4 | 9/2 | 797/1808 | over |

| GO:0006757 | ATP generation from ADP | 0.0078/3.08e-4 | 11/3 | 795/1807 | over |

| GO:0016052 | carbohydrate catabolic process | 0.0359/0.0020 | 10/4 | 796/1806 | over |

| GO:0005976 | polysaccharide metabolic process | 0.0359/0.0020 | 9/3 | 797/1807 | over |

| GO:0006165 | nucleoside diphosphate phosphorylation | 0.0168/8.36e-4 | 11/4 | 795/1806 | over |

| GO:0009132 | nucleoside diphosphate metabolic process | 0.0066/2.55e-4 | 10/2 | 796/1808 | over |

| GO:0009135 | purine nucleoside diphosphate metabolic process | 0.0066/2.55e-4 | 10/2 | 796/1808 | over |

| GO:0009179 | purine ribonucleoside diphosphate metabolic process | 0.0066/2.55e-4 | 10/2 | 796/1808 | over |

| GO:0009185 | ribonucleoside diphosphate metabolic process | 0.0383/0.0022 | 13/7 | 793/1803 | over |

| GO:0019362 | pyridine nucleotide metabolic process | 0.0383/0.0022 | 13/7 | 793/1803 | over |

| GO:0046496 | nicotinamide nucleotide metabolic process | 0.0066/2.58e-4 | 7/0 | 799/1810 | over |

| GO:0003755 | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity | 0.0066/2.58e-4 | 7/0 | 799/1810 | over |

| GO:0000413 | protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization | 0.0066/2.58e-4 | 7/0 | 799/1810 | over |

| GO:0016859 | cis-trans isomerase activity | 0.0383/0.0022 | 13/7 | 793/1803 | over |

| GO:0018208 | peptidyl-proline modification | 0.0168/8.36e-4 | 11/4 | 795/1806 | over |

| GO:0042221 | response to chemical | 0.0454/0.00275 | 5/0 | 801/1810 | over |

| GO:0000049 | tRNA binding | 0.0454/0.00275 | 5/0 | 801/1810 | over |

| GO:0006935 | chemotaxis | 0.0454/0.00275 | 5/0 | 801/1810 | over |

| GO:0040011 | locomotion | 0.0168/8.44e-4 | 6/0 | 800/1810 | over |

| GO:0042330 | taxis | 0.0168/8.44e-4 | 6/0 | 800/1810 | over |

| Specific to the subclade I.3 from subsp. pauca: transport, recombination, organelle part | |||||

| GO:0006310 | DNA recombination | 0.0093/5.91e-4 | 0/12 | 1147/1281 | under |

| GO:0006812 | cation transport | 0.0368/0.0029 | 2/15 | 1145/1278 | under |

| GO:0015672 | monovalent inorganic cation transport | 0.0282/0.0022 | 1/13 | 1146/1280 | under |

| GO:0034220 | ion transmembrane transport | 0.0089/5.56e-4 | 2/19 | 1145/1274 | under |

| GO:0098655 | cation transmembrane transport | 0.0167/0.0012 | 1/14 | 1146/1279 | under |

| GO:0098660 | inorganic ion transmembrane transport | 0.0103/6.72e-4 | 1/15 | 1146/1278 | under |

| GO:0098662 | inorganic cation transmembrane transport | 0.0488/0.0040 | 1/12 | 1146/1281 | under |

| GO:0008324 | cation transmembrane transporter activity | 0.0282/0.0022 | 1/13 | 1146/1280 | under |

| GO:0044422 | organelle part | 0.0167/0.0012 | 1/14 | 1146/1279 | under |

| GO:0044446 | intracellular organelle part | 0.0167/0.0012 | 1/14 | 1146/1279 | under |

| Specific to the CFBP 8072 genome from subsp. pauca: nucleoside and carboxylic acid biosynthetic processes | |||||

| GO:0009142 | nucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 0.0303/0.0020 | 0/8 | 1205/1024 | under |

| GO:0072330 | monocarboxylic acid biosynthetic process | 0.0158/9.28e-4 | 0/9 | 1205/1023 | under |

| Specific to the Hib4 genome from subsp. pauca: response to stress, transfer/transport activity, iron-sulfur binding, component assembly/organization | |||||

| GO:0006950 | response to stress | 1.39e-4/1.05e-5 | 1/17 | 1323/1047 | under |

| GO:0006979 | response to oxidative stress | 0.0279/0.0034 | 0/7 | 1324/1057 | under |

| GO:0033554 | cellular response to stress | 0.0153/0.0017 | 1/11 | 1323/1053 | under |

| GO:0008565 | protein transporter activity | 0.0279/0.0034 | 1/10 | 1323/1054 | under |

| GO:0009055 | electron transfer activity | 0.0279/0.0034 | 0/7 | 1324/1057 | under |

| GO:0015197 | peptide transporter activity | 0.0153/0.0017 | 1/11 | 1323/1053 | under |

| GO:0016667 | oxidoreductase activity, acting on a sulfur group of donors | 0.0135/0.0015 | 0/8 | 1324/1056 | under |

| GO:0051540 | metal cluster binding | 0.0055/5.56e-4 | 2/14 | 1322/1050 | under |

| GO:0051536 | iron-sulfur cluster binding | 0.0055/5.56e-4 | 2/14 | 1322/1050 | under |

| GO:0051539 | 4 iron, 4 sulfur cluster binding | 0.0279/0.0034 | 1/10 | 1323/1054 | under |

| GO:0022607 | cellular component assembly | 0.0023/2.15e-4 | 1/13 | 1323/1051 | under |

| GO:0043933 | macromolecular complex subunit organization | 0.0066/6.79e-4 | 0/9 | 1324/1055 | under |

1Complete datasets are provided in Additional file 7

2Annot test/ref.: number of GO-associated CDS in the list of CDS harboring specific mers (query) / number of GO-associated CDS in the reference genome

3Non-annot test/ref.: number of non-annotated (no GOs) CDS in the list of CDS harboring specific mers (query) / number of non-annotated (no GOs) CDS in the reference genome

Reconstruction of the parental origin of the subspecies morus

The subspecies morus was proposed to group strains pathogenic on Morus that derived from largescale intersubspecific homologous recombination events between ancestors from at least subspecies fastidiosa and multiplex. This assumption is based on the analysis of seven housekeeping genes [16]. We challenged it with whole-genome sequence datasets to further understand the contribution of the subspecies fastidiosa, multiplex and others in the parenthood of the subspecies morus. We used SkIf to identify mers specific of the morus group (i.e. two strains, Mul-MD and Mul0034) plus one of each of the other groups (Table 6B; Additional file 6). The highest level of specific mers was found for the combination morus x fastidiosa x sandyi: the highest mer cumulated size represented 5% of the Mul0034 genome in size (which does not mean that all the 5% are unique to Mul0034). The morus x multiplex (3.6%) and morus x pauca (< 0.1%) relationships were lower. To illustrate these findings, the specific mers were mapped onto the Mul0034 genome and were found to be distributed all along the sequence (Fig. 3). These results on closest relationships between genomes of subspecies fastidiosa, sandyi, and morus are coherent with the ANIb values (Additional file 1). Enrichment tests identified shared GO terms for the various combinations indicated (Table 6B). For the combination morus x multiplex, one GO term linked to the amino acid biosynthetic process was specifically recorded. At the level of fastidiosa x sandyi x sandyi-like x morus, 28 GO terms were specifically identified, associated with various processes like cellular component or protein complex disassembly, peptidyl-proline activity and chemotaxis.

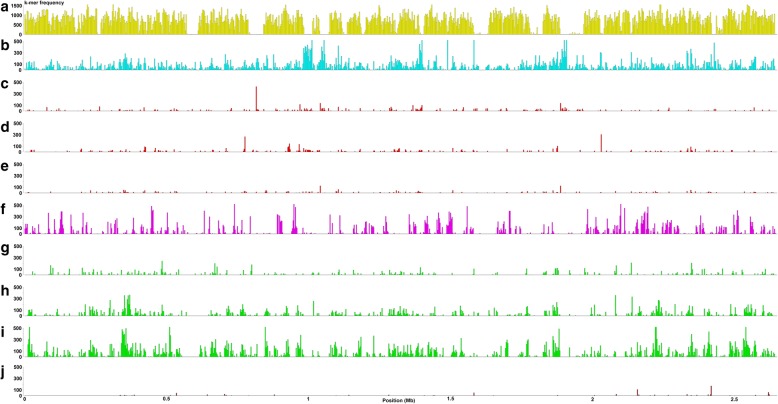

Fig. 3.

Distribution of k-mers specific to the X. fastidiosa subspecies morus and others. a core k-merome of X. fastidiosa species. b specific subsp. morus. c, d, e specific subsp. morus + sandyi and/or sandyi-like. f specific subsp. morus + multiplex. g, h specific subsp. morus + fastidiosa (with/without CFBP 8073 strain). i specific subsp. morus + fastidiosa (with CFBP 8073) + subsp. sandyi + subsp. sandyi-like. j specific subsp. morus + pauca. Frequency of k-mers are mapped onto the genome of reference for subsp. morus (Mul0034)

A focus on these 28 categories was performed. Due to the redundancy within the GO hierarchical nomenclature, the 28 GOs were reduced to six. All the CDS harboring specific long-mers in Mul0034 genome were retrieved, as well as their closest homologs in the in- (subsp. fastidiosa, sandyi, sandyi-like, morus) and the out- (subsp. multiplex or pauca) groups. This corresponded to 26 CDS found each in a single copy in all the 46 Xf genomes, indicating that they belong to the Xf core genome. For each gene, the sequences were aligned together with the specific long-mers (80 long-mers in total), against the sequence in Mul0034 used as a reference. First, perfect identity in long-mer sequence was conserved among all the genomes of subsp. fastidiosa, sandyi, sandyi-like, and morus. In contrast, SNPs were always found in the alignment of multiplex and pauca sequences. In comparison with multiplex, 46/80 long-mers had only synonymous SNPs and 34 had non-synonymous SNPs in the gene sequences. Considering the 26 CDS, 18 harbored non-synonymous SNPs. In comparison with pauca, half long-mers had only synonymous SNPs and half had non-synonymous SNPs in the gene sequences. Considering the 26 CDS, 21 harbored non-synonymous SNPs (Additional file 8).

Genetic diversity within the subspecies pauca

ANIb values clearly showed genetic heterogeneity among strains of the subspecies pauca. Three lineages were differentiated: subclade I.1 included seven citrus strains (9a5c, U24D, Fb7, CVC0251, CVC0256, J1a12 and 11,399) and two coffee strains (3124 and 32); subclade I.2 included two coffee (6c and COF0324) and one Prunus (Pr8x) strains, and subclade I.3 included the ST53 strains CoDiRO, COF0407, OLS0478 and OLS0479. Two strains, CFBP 8072 and Hib4 were isolated, as they appeared outside (Additional file 1).

A search for specific mers within these three subclades (Table 6C, Additional file 6) and the identification of associated GO terms (Table 8; Additional file 7) were performed. At the level of subspecies pauca it concerned 175 GO terms, including 16 terms related to nucleotide metabolic/biosynthetic process, especially for purine and 20 terms associated with the bacterial cell wall/envelope/plasma membrane. A focus on these 20 categories was performed. Due to redundancy within the GO hierarchical nomenclature, the 20 GOs were reduced to eight. All the CDS harboring specific long-mers in 9a5c genome were retrieved, as well as their closest homologs in the in- (subsp.pauca) and the out- (subsp. multiplex or fastidiosa, sandyi, sandyi-like, and morus) groups. This correspond to 105 CDS found each in a single copy in almost all the 46 Xf genomes. For each gene, the sequences were aligned together with the specific long-mers (746 k-mers in total), against the sequence in 9a5c used as a reference. First, perfect identity in long-mer sequence was conserved among all the genomes of subsp. pauca, except for 6 long-mers with small variants in a few pauca strains. In contrast, SNPs were always found in the alignment with multiplex and fastidiosa, sandyi, sandyi-like, morus sequences. In comparison with multiplex, 390/746 long-mers had only synonymous SNPs, 354 had non-synonymous SNPs and 2 long-mers were not found. Considering the 105 CDS, 93 harbored non-synonymous SNPs. In comparison with fastidiosa, sandyi, sandyi-like, and morus, 368 long-mers had only synonymous SNPs and 378 had non-synonymous SNPs in the gene sequences. Considering the 105 CDS, 92 harbored non-synonymous SNPs (Additional file 8). The search for enriched GO was also performed at the subclade level. For the subclade I.1, only one term was found (catalytic activity, GO:0003824). In all other studied cases (subclades or individual strains within subsp. pauca), all the GO terms identified were under-represented. This might be explained by a recent evolution in these strains/subclades, rendering the corresponding SNPs in these functional gene ontologies less frequent. Two regions harboring specific mers in 13 pauca strains (subclades I.2 and I.3, plus Hib4) and absent in the others (subclade I.3 plus CFBP 8072) were identified (Fig. 4). These include genes encoding various enzymes (endonuclease, hydrogenase, hydrolase, integrase/recombinase, methyltransferase, peptidase, polyketide synthase, reductase, terminase, topoisomerase) and genes associated with bacteriophages (Additional file 6). For subclade I.3, 10 GO terms were specific, dealing with transport, recombination, and organelle part. CFBP 8072 has two specific GO terms nucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process and monocarboxylic acid biosynthetic process. As for the Hib4 genome, 12 terms were found as unique, associated with iron-sulfur complex, or transport activity.

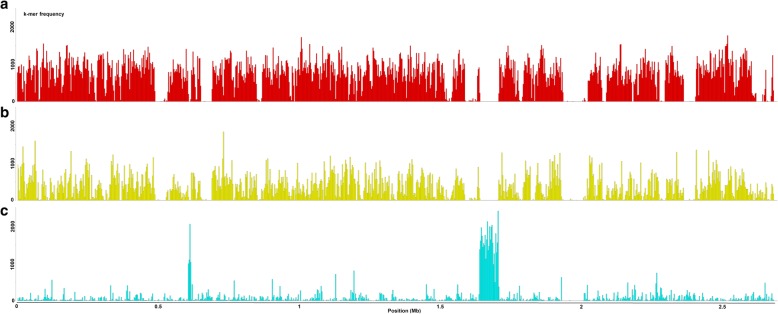

Fig. 4.

Distribution of k-mers specific to the X. fastidiosa subspecies pauca and its subclades. a core k-merome of X. fastidiosa species. b specific subsp. pauca. c specific of subclade I.2, I.3 and strain Hib4 from subsp. pauca. Frequency of k-mers are mapped onto the genome of reference for subsp. morus (Mul0034)

Identification of chromosome and plasmid specific islands unique in X. fastidiosa Hib4

The k-mer approach identified three large genomic regions that were specific to the strain Hib4. A fragment of 34,148 bp (long-mer2422 in Additional file 6) appeared to be chromosomic. It contained 34 genes coding for 12 hypothetical/conserved proteins, 8 conjugal transfer proteins (including TraG), 3 membrane proteins, 2 methyltransferases, and one acriflavine resistance protein B, DEAD/DEAH box helicase, DSBA oxidoreductase, hemolysin secretion protein D, integrating conjugative element protein pill (pfgi-1), lytic transglycosylase, multidrug transporter, RAQPRD family plasmid, and superoxide dismutase (Additional file 6). The screen (blastn) of the Nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database revealed that it shared high identities (> 90%) with sequences of Cupriavidus sp., Comamonas testosterone, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Bordetella petrii, but the largest fragments cover no more than 60% of the X. fastidiosa long-mer (Additional file 9).

Two large regions of 32,804 bp (long-mer4538 in Additional file 6) and 16,015 bp (long-mer4596) localized onto the plasmid pXF64-HB. Together with smaller specific long-mers (long-mer4536 to 4596), they accounted for 60,224 bp over the 64,251 bp total size of this plasmid https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_CP009886.1). It contained 39 genes, including genes coding hypothetical proteins (23), conjugal transfer proteins (7; TraH, I, J, K, N, Q, U, W), and one DNA topoisomerase, endonuclease, helicase, lytic transglycosylase, membrane protein, mobilization protein, protein mobD, relaxase, and TrbA (Additional file 6). The plasmid could have been acquired from a strain of Paraburkholderia hospita (93% identity over 86% length of the plasmid), P. aromaticivorans (86% identity over 83% length) or even Burkholderia vietnamiensis (81% identity over 76% length) or Xanthomonas euvesicatoria (80% identity over 72% length) (Additional file 9).

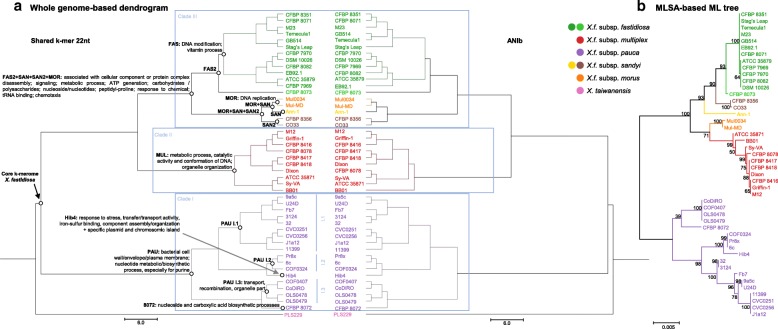

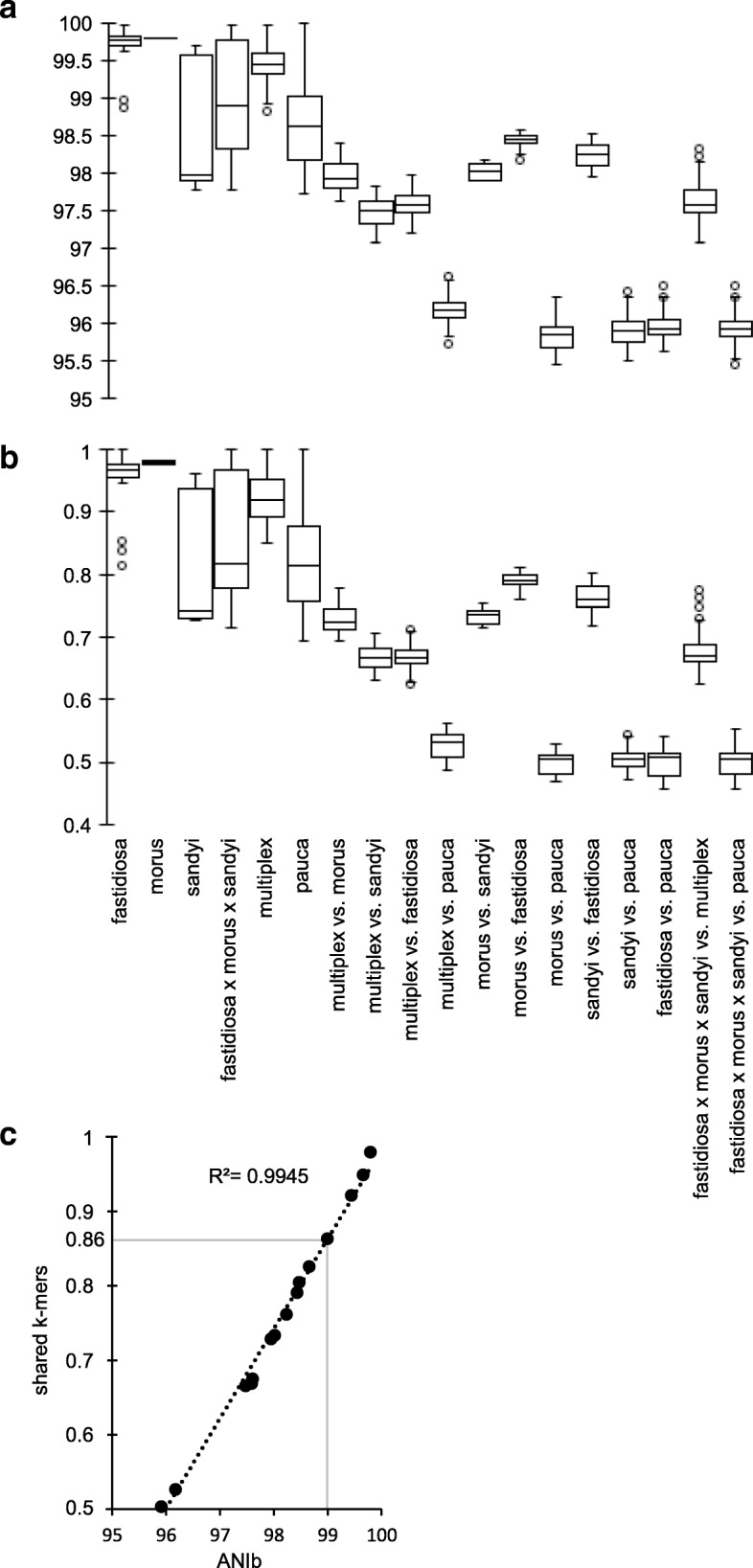

Robust whole genome-based X. fastidiosa clustering with shared k-mers

After looking at specific k-mers in whole genome sequences using SkIf, we employed a complementary approach to draw a robust image of the genetic relationships among individuals, based on shared k-mers. Simka [23] provided a distance matrix that was transformed in a similarity matrix corresponding to the percent of shared k-mers to assess strain relationships (Additional file 10). The k-mer-based dendrogram showed a general distribution into three major clades, represented by the subspecies pauca (clade I), multiplex (clade II), and the union of subspecies fastidiosa¸ sandyi and morus (clade III; Fig. 5). It is congruent with the one obtained with ANIb illustrated by with a strong linear regression (r2 = 0.9945; Fig. 6). The current clustering of X. fastidiosa in five subspecies should be restricted to three subspecies, a proposal that is supported by ANIb and shared k-mers values (99.00% and 0.86, respectively) for clade III (Fig. 6, Additional files 1 and 10). This mostly differ from the view obtained with a MLSA scheme (7 genes) by the repositioning of the subspecies morus (Fig. 5). We finally mapped the key points resulting from SkIf (specific k-mers) analysis on the dendrogram (shared k-mers) to illustrate how X. fastidiosa genetic diversity can be associated with particular traits (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic representation of X. fastidiosa using k-mers, ANIb and MLSA schemes. All the representations were constructed using the 46 X. fastidiosa, with addition of the X. taiwanensis genome sequence. a Whole genome-based dendrogram built with distance matrixes obtained after running simka (shared k-mers of 22 nucleotides) or ANIb (1020 nt) algorithms. Some specificities and similarities in enriched gene ontologies or identification of plasmid and chromosomic sequences specific to X. fastidiosa are highlighted at nodes or subclades. b Maximum-Likelihood (ML) tree constructed with 1000 replicates for bootstrap values using the concatenated sequences (4161 bp) of seven housekeeping genes from a MultiLocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) scheme. Key features related to X. fastidiosa subspecies obtained through the combination of specific k-mer identified and gene ontologies enrichment tests are indicated at nodes

Fig. 6.

Inter- and intrasubspecies comparisons of ANIb and shared k-mers values. a Boxplot of the ANIb values calculated from our genome dataset. b Boxplot of the shared k-mer values. c Dot plot of the ANIb and shared k-mer mean values. Linear regression and its corresponding r2 is indicated. For intrasubpecies comparisons, the number of plotted values corresponds to [(number of genome) 2 - number of genome]. For intersubspecies comparisons, it corresponds to [(2 * number of genome subspecies A * number of genome subspecies B)]. Number of genomes: fastidiosa (13), morus (2), sandyi (3), multiplex (10), pauca (18)

Discussion

While tools based on k-mers are mainly used to improve genome assembly [36, 37], SkIf (https://sourcesup.renater.fr/wiki/skif/) was developed to quickly extract information from genomic datasets from already assembled genomes. It allows to decipher genomic fragments associated with traits shared by a group of sequences of interest. This strategy is applicable to any scientific questions requesting the comparison of user-defined groups of sequences.

Because management of X. fastidiosa outbreaks in France depends on the subspecies of X fastidiosa, it is of major importance to precisely define these subspecies, understand the robustness of these groupings and their meaning in terms of shared and specific genetic material. In order to detect genomic regions specifically associated with a group of organisms (i.e. a subspecies) we applied SkIf to gain a better understanding of X. fastidiosa clusterings in subspecies. This tool was also used to mine large databases as a first step to evaluate worldwide dispersion of X. fastidiosa in natural settings.

The phylogeny provided by shared k-mers was highly similar to the one based on ANIb, a reference method for analyzing phylogeny of bacteria [38, 39]. However, phylogenies were much more quickly constructed using shared k-mers than were ANI calculations in JSpecies. Here, k-mers of 22 nt were used while ANIb and TETRA are calculated from k-mers of 1020 and 4 nt, respectively, and ANIm values result from the maximal unique match decomposition of two genomes [40–42].

The current grouping of X. fastidiosa in five subspecies is inappropriate and is not supported by genomic data. This is obvious regarding the phylogenies reconstructed using shared-k-mers and ANIb (Fig. 5) and it is coherent with a previous proposal [43]. Three-well demarcated genomic clusters were retrieved in phylogenetic trees reconstructed from 46 genome sequences. X. fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa embraced, in addition to the classical subsp. fastidiosa strains, the more recently proposed sandyi and morus subspecies. Mean ANIb values of 99% are found within the former subspecies, while ANIb value with the two later are below 98% (Fig. 6). The two-other subspecies, multiplex and pauca, were well supported, even if subsp. pauca showed a clear divergence between the lineage of strains isolated from citrus and coffee in Brazil vs. the lineage of other strains isolated from coffee from Central America and olive. Indeed, mean ANIb value of 99.44% was calculated within the multiplex subspecies, while ANIb values below than 97% were found with the other two subspecies. Concerning pauca, mean ANIb value of 98.48% was calculated for the 18 genome sequences included in this subspecies while ANIb values of less than 97% were obtained with the two-other species. This mean ANIb value of only 98.66% within pauca clearly illustrate the largest diversity found in this subspecies in comparison to the fastidiosa and multiplex ones. This grouping in a subsp. fastidiosa sensu largo also matches with an enrichment in 28 GO terms associated with various processes like cellular component or protein complex disassembly, peptidyl-proline activity and chemotaxis. Interestingly, GO-enriched associated CDSs, which harbor k-mers specific to this clade, have homologs in all other X. fastidiosa genomes, but most often these homologs present non-synonymous SNPs, avoiding perfect matches with the k-mers. More importantly, this suggests diversity in protein sequences with putative impact on their functions. Referring to the definition of the species and a threshold value of ANI at 95% [39] values calculated here on 46 genomes sequences indicate that X. fastidiosa with its diversity forms a unique species.

Grouping the subspecies morus within a subspecies fastidiosa sensu largo is coherent with the results of the analysis made to uncover the origin of the subsp. morus. This subspecies was proposed to group strains pathogenic on mulberry trees that derived from recombination events between ancestors of the subspecies fastidiosa and multiplex [16]. The use of SkIf showed that the cumulated size of the mers uniquely shared within genomes of the clade III (subsp. morus, fastidiosa, sandyi and relatives) represents 5% of the Mul0034 genome, while those uniquely shared between subsp. morus and multiplex count for 3.7%. That showed a closest proximity of morus with fastidiosa and sandyi strains than with multiplex. But because some mers are uniquely associated with the two morus genomes (Additional file 6), some genetic material of an unknown origin has been introduced in morus subspecies genome during evolutionary history.

The evolutionary history of X. fastidiosa is also driven by the acquisition of genetic material from heterologous origin. Recently the genome sequence of Hib4 strain was released. This strain presents three large genomic fragments that are unique within X. fastidiosa. One of these regions is chromosomic, the two others locate on a large plasmid (~64kbp) that is not found in any other X. fastidiosa genome sequence but share strong homology with plasmids from Burkholderia hospita DSM17164 [44], P. aromaticivorans BN5 [45], Burkholderia vietnamensis G4 [46], or Xanthomonas euvesicatoria LMG930 [47] strains (Additional file 9). It should be mentioned that so far it is the only case of a plasmid that is not distributed in various strains within X. fastidiosa and that originates from a non-Xylella strain. Thus, it is tempting to hypothesize on how the acquisition could have occurred, while not easy as these species were isolated from various natural environments including water, soil and plants. Interestingly, X. euvesicatoria LMG932 was isolated from Capsicum frutescensi in Brazil [48], the country of origin of X. fastidiosa Hib4 strain isolated from Hibiscus fragilis. Several strains of Burkholderia vietnamensis were isolated from Coffee plants in Mexico [49], while other were isolated from a Brazilian cystic fibrosis patient [50]. These findings illustrate the presence of putative plasmid donor either in the country (Brazil) were Hib4 was isolated and on a host (coffee) in a country (Mexico) were X. fastidiosa is known to occur. Another particularity of Hib4 is that its harbors two specific regions, only shared with strains of the subsp. pauca subclades I.1 and I.2 (Fig. 4). These genomic regions presumably result from a bacteriophage origin. They could have been acquired specifically by a common ancestor of subclades I.1, I.2 and Hib4 or they could have been lost during evolution, accentuating the degree of divergence with other pauca strains.

Microbial collections exchange strains, but mistakes during collection curation cannot be totally excluded, engendering distribution of mislabeled strains, as already shown for X. fastidiosa [51]. SkIf proved useful to survey microbial collections for synonyms. Here, following the release of the genome sequence of the X. fastidiosa type strain from three origins (CFBP 7970 in the present study, ATCC 35879, DSM 10026), SkIf was used to check the relevance of their synonymy. While not strictly identical due to sequencing and assembly biases, the most striking feature was the putative absence of a large fragment in ATCC 35879, corresponding to a plasmid carrying a complete type IV secretion system [34]. Yet, based on our analysis, it is possible that the plasmid could be present in ATCC 35879, but could have been partially lost during the read filtering and assembly process, or even during strain cultivation. The synonymy between the three strains would therefore be valid. An alternative scenario might be that the plasmid-like sequences have been integrated into the chromosome of ATCC 35879 whilst the plasmid was lost, and in this case, only CFBP 7970 and ATCC 35879 are indeed synonymous. The definite answer will come from an analysis of the raw reads of ATCC 35879 to check for the presence/absence of the plasmid (raw reads are currently not available in SRA) or from a plasmid extraction from the specimen stored at ATCC.

Occurrences of X. fastidiosa found in Silva rRNA database were assigned to subspecies that are coherent with sample designation. Specific mers of the genus Xylella and of the various subspecies of X. fastidiosa were retrieved in the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA encoding genes. One use of these tools is to taxonomically assign at the subspecies level the occurrences of X. fastidiosa from large database. The sample description and especially the name of the plant species of isolation allow to validate the assignation provided by specific mers. It should however be noticed, that some plant species like almond, olive tree, oleander, coffee tree, or citrus may be host of several X. fastidiosa subspecies (www.pubmlst.org/xfastidiosa) [52] and in consequence this a posteriori validation will not always be possible. Long read sequencing will generate more full length 16 s rRNA gene sequences which will facilitate subspecies discrimination. Another tempting use of these tools could be to survey large metagenome database for occurrences of these markers. This is however currently not feasible due to an astonishingly too long time required to download data or incapacity to browse those databases using our markers. Another use will be to design primers and if required probes for PCR detection-identification of X. fastidiosa in plant material.

Conclusions

Skif is a freely available, bioinformatic tool dedicated to the identification of specific mers. Although the results presented here were applied in the context of the emerging plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa in Europe, this software is useful to answer many other questions beyond this scope. It is adapted to mine various group of sequences (gene, protein, genome, metagenome databases) defined by the user to identify specific or shared features. In the context of X. fastidiosa it allowed to i) refine the current grouping in subspecies that are not supported by genomic data; ii) trace the origin of the subspecies morus, a plasmid from Hib4 strain and the extent of synonymy among specimen representing the same initial strain in microbial collections; and iii) design markers that are specific to each subspecies of X. fastidiosa.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The seven strains of X. fastidiosa (Table 2) used in this study were provided by the French Collection of Plant-Associated Bacteria (CIRM-CFBP; http://www6.inra.fr/cirm_eng/CFBP-Plant-Associated-Bacteria). Strains were grown on B-CYE [53] medium up to 8 weeks at 28 °C. Experiments with X. fastidiosa living cells were carried out under quarantine at IRHS, Centre INRA, Beaucouzé, France under the agreement no. 2013119–0002 from the Prefecture de la Région Pays de la Loire, France.

Genomic DNA extraction

For genome sequencing, bacterial material was harvested on agar plates and suspended in 4.5 ml of sterile, ultrapure water. Genomic DNA was extracted with the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA was recovered in 100 μl of elution buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.5) with final concentration ranging from 3 to 12 μg. Quality and quantity of extracted genomic DNA were checked by depositing an aliquot on agarose gel combined to the use of a nanodrop (Thermo Scientific).

Library preparation

Genomic DNA solutions were homogenized at 20 ng/μl in 55 μl of resuspension buffer to prepare libraries of sonicated, purified, blunted, and adenylated DNA fragments of 350 bp, following the instructions of the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Guide – Low Sample (LS) Protocol (Catalog #FC-121-9006DOC, Part #150361887 Rev. B, November 2013). Adapters were ligated using the Illumina TruSeq DNA Free PCR LT kit. Libraries were individually quantified and then mixed in a single, equimolar pool (40 nM) also quantified by qPCR following the recommendations of the Library Quantification kit (Kapa Biosystems).

Genome sequencing, assembling, and annotation

For sequencing, diluted libraries (4 nM) were denatured as described (Illumina Preparing DNA libraries for Sequencing on the MiSeq protocol), resulting in 20pM denatured DNA. The final DNA concentration used for sequencing was 12pM in a 600 μl volume containing 1% of PhiX control. The sample was deposited in a V3 cartridge. The seven X. fastidiosa genomes were sequenced with the Illumina MiSeq v3 600 cycles technology at the ANAN plateform, SFR QuaSav, Angers, Fr. Genome assembly was performed using a combination of Velvet [54], SOAPdenovo and SOAPGapCloser [55] assemblers. Structural and functional annotations were conducted with Eugene-PP algorithm [56], using a concatenation of the Swissprot database and the publicly available X. fastidiosa 9a5c [57] and Temecula1 [58] genomes.

Definition of the acronyms

In this study, we used the following definitions for these five key terms: i) mer: a sequence within a nucleotide character string; ii) k-mers: all the possible substrings of length k that are contained in a nucleotide character string; iii) long-mer: a result of the concatenation of overlapping and/or consecutive mers; iv) specific mers: sequences that are exclusively found for members of the group of interest (in-group) while small variants (i.e. with a few indels or SNPs) can be found in some members of the out-groups without being strictly identical; and (v) shared mers: sequences that are found in all the members of different groups of interests or that are common to two individuals in the case of pairwise comparisons.

Identification of shared or specific k-mers

The percent of shared k-mers between two genome sequences were calculated from the distance matrix built using Simka [23]. Parameters were selected as follow: “-kmer-size 22”, “-abundance-min 1”. SkIf (v1.2) was developed in C ++ and sequence reading was done using Bio++ bpp-seq library [59]. To identify genomic regions that are specific to a group of sequences of interest, SkIf construct an abundance matrix of all mers of sequences. This matrix is used to identify the mers present in all the sequences of the group of interest (in-group) and absent in all the other sequences. Parameters were selected as follow: “-k 22”, “-a dna”, “-g = in-group list”. Then, it maps the specific mers of the in-group to the reference genome sequence of the group and provides their precise locations. By comparing mer length and the positions of the various occurrences, SkIf concatenates the overlapping mers into long-mer using the script “getLongestKmersNC.pl” (option: -k 22; available with Skif). A list of located mers or long-mers specific to the group of interest was hence obtained. Finally, we developed a wrapper for accessing this process in a user-friendly Galaxy tool (https://iris.angers.inra.fr/galaxypub-cfbp). Hence, SkIf allows to extract all specific mers of a dataset. The optimal size of the mer was fixed to 22 nt to optimize the ratio of in-group to out-group specific sequences, after a comparison of a range from 18 to 26 nt was done (data not shown).

Analyses of genome and nucleotide sequences and phylogeny

For the analyses of the seven housekeeping genes used in MLSA-MLST scheme designed for X. fastidiosa (https://pubmlst.org/xfastidiosa/info/primers.shtml) and the 16S rRNA gene and the synonymy of SNPs, nucleotide sequences were aligned using the Geneious suite, with the default parameters of the ‘MUSCLE Alignment’ and the ‘Map to Reference’ options [60]. Maximum-Likelihood (ML) tree was constructed with 1000 replicates for bootstrap values using the concatenated sequences (4161 bp) of seven housekeeping genes from the MLSA scheme. ANIb values were calculated using Pyani [30]. Similarity matrix (based on ANIb or shared k-mers) were transformed into distance matrix (1-ANIbs*100 or 1-shared k-mers*100) in the dist format of R using as.dist and clustered using Ward’s method [61] for hierarchical clustering. Conversion of the distance matrix into dendrograms relied on as.phylo function from R ape package [62]. Blastn (v2.8.0+) analyses were run against the nucleotide collection (nt; 46,977,437 sequences) [63].

Enrichment tests and Venn diagram representations

Enrichment analyses with a Fisher’s Exact Test were performed with Blast2GO v4.1 [64], using the Gene Ontology functional annotations to compare gene lists carrying specific k-mers against all the gene of the reference genomes to identify statistically significant enrichment in biological processes or molecular functions. Venn diagrams were built using jvenn (http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/index.html [65].

Development of a galaxy-based website and user guidelines

The SkIf pipeline is free for use online (https://iris.angers.inra.fr/galaxypub-cfbp). Required input files are a zip file with all the fasta files for the in-group genome sequences; a zip file with all the fasta files for the outgroup genome sequences; the length of the k, and the identifier of the reference genome sequence from the in-group. Output files are text files with the list of the k-mers and long-mers specific to the in-group if existing. A wiki page describing SkIf is accessible at https://sourcesup.renater.fr/wiki/skif.

Mining of 16S rRNA database

For the genus analysis, the in-group included the 74 Xylella 16S rRNA copies and the out-group included all the small subunit rRNA gene (SSU) sequences from the Silva database (https://www.arb-silva.de/; release 128) [66] other than Xylella-tagged. For the species analysis, X. taiwanensis PLS 229 strain was included in the out-group. All sequences affiliated to X. fastidiosa were included in the in-group, while all the other, non-X. fastidiosa, were included in the out-group. Ambiguous sequences (e.g. double assignation to Xylella and Xanthomonas) were excluded. SkIf software was used as described above to identify specific k-mers (−k 22) in the in-group and to concatenate consecutive ones in long-mers.

Additional files

Pairwise comparison of 47 Xylella sp. genomes using average nucleotide identity based on blast (ANIb). (DOCX 63 kb)

K-mers resulted from the comparison of synonymous strains CFBP 7970, DSM 10026 and ATCC 35879. (ZIP 45 kb)

Blast analysis of the known X. fastidiosa plasmid sequences against the genome sequence of ATCC 35879. (DOCX 30 kb)

Raw data of analyses of the 16S rRNA gene repertoire in Xylella. (ZIP 12 kb)

X. fastidiosa 16S rRNA sequences from Silva database carrying the five long-mers and taxonomically assigned to a subspecies with the SNP-based code. (DOCX 21 kb)

Raw data of the k-mers identified to be specific of the different X. fastidiosa subspecies or combinations of several subspecies. (ZIP 3012 kb)

Raw data of the gene ontologies enrichments tests with Blast2GO. (ZIP 22422 kb)

Analysis of (non-)synonymous SNPs in homologs to CDS harboring specific k-mers for selected enriched GOs. (ZIP 549 kb)

Blast analysis of the three large fragments specific to X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca Hib4 strain. (DOCX 34 kb)

Pairwise comparison of 47 Xylella sp. genomes using the occurrence of shared k-mers of length 22 bp. (DOCX 68 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Muriel Bahut (ANAN technical facility, SFR QUASAV, Angers, FR) for genome sequencing, CIRM-CFBP (Beaucouzé, INRA, France; http://www6.inra.fr/cirm_eng/CFBP-Plant-Associated-Bacteria) for strain preservation and supply, and the CATI BBRIC for the galaxy tools allowing assembling the reads and annotating the sequences, and using Blast2GO. We acknowledge Charles Manceau (Anses, Angers, FR) for his contribution while applying for funding. We thank Matthieu Barret for fruitful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

ND salary was funded by the regional program “Objectif Végétal, Research, Education and Innovation in Pays de la Loire”, project SapAlien 2015–2017, supported by the French Region Pays de la Loire, Angers Loire Métropole and the European Regional Development Fund. This work received support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement 635646 POnTE (Pest Organisms Threatening Europe). The present work reflects only the authors’ view and the EU funding agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Availability of data and materials

Strains of Xylella fastidiosa deposited at the CIRM-CFBP (Angers, FR) are available upon request (https://www6.inra.fr/cirm_eng/CFBP-Plant-Associated-Bacteria). The SkIf pipeline is free to use online (https://iris.angers.inra.fr/galaxypub-cfbp). All the sequence files related to the k-mer analyses (raw data, alignments, blast, GO enrichment tests) are submitted together with the manuscript as Additional files. Genome sequences were deposited at NCBI under the following accessions numbers: PHFQ00000000 (CFBP 7969), PHFR00000000 (CFBP 7970), PHFP00000000 (CFBP8071), PHFS00000000 (CFBP 8078), PHFT00000000 (CFBP 8082), PHFU00000000 (CFBP 8351), and PHFV00000000 (CFBP 8356). Related data and reannotation of the public genomes (fasta, genbank and gff3 formats) are available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ANIb

Average nucleotide identities using blast

- ANIm

Average nucleotide identities using MUMmer

- CDS

Coding sequence

- GO

Gene ontology

- ICE

Integrative and conjugative elements

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNA

- SkIf

Specific k-mers Identification

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TETRA

Tetranucleotide frequency correlation coefficients

Authors’ contributions

ND designed the in silico analyses. MB, RG, and SG designed the bioinformatics tools. ND and MB performed the in silico analyses and interpreted the data. MAJ conceived the study, applied for funding, and interpreted the data. ND and MAJ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nicolas Denancé, Email: nicolas.denance@orange.fr.

Martial Briand, Email: martial.briand@inra.fr.

Romain Gaborieau, Email: romain.gaborieau@hotmail.fr.

Sylvain Gaillard, Email: sylvain.gaillard@inra.fr.

Marie-Agnès Jacques, Phone: +33 241 225 707, Email: marie-agnes.jacques@inra.fr.

References