Abstract

Rupture of the pectoralis major remains an infrequent injury, although, recently, it has been reported more commonly as a result of the expansion and increasing popularity of competitive sports, as well as developments in sports medicine. A number of surgical repair techniques have been described for direct repair in the acute setting. However, on occasion, the pectoralis major muscle is so retracted that a tension-free direct repair is not possible. We describe a technique for allograft reconstruction of the pectoralis major, with our preliminary outcomes, where it is found or anticipated that a direct repair is not possible.

Keywords: allograft, outcomes, pectoralis major, reconstruction, technique, tendo-achilles

Introduction

Rupture of the pectoralis major remains an uncommon injury, but has been reported more recently as a result of the expansion and increasing popularity of competitive sports and weight training. The injury usually occurs at the humeral insertion as a tendinous avulsion associated with resistance upper limb activities.1,2 This injury is more common in men and the bench press exercise is the most frequently cited mechanism of injury.3–5 Diagnosis of this condition is best made using a cluster approach comprising a good history, examination and focused imaging.6

A number of surgical repair techniques have been described for direct repair including the use of bone tunnels, sutures, screws and staples, as well as a suture anchor technique, which we have reported previously.5,7 All of these techniques have been reported with success for acute direct repairs. However, in chronic and significantly retracted tears, a tension-free direct repair is not possible.8,9 Chronic tears may sometimes be well tolerated; however, some patients may complain of residual symptoms, including cramping, functional weakness and an unsatisfactory appearance.4,9,10 The main indication for surgery is pain and functional loss that adversely affects a manual worker to perform their job or competitive sporting activity. Cosmesis is not the primary indication for this surgery.

We describe a technique for allograft reconstruction of the pectoralis major where a direct repair is not possible. This has been employed by the senior author (LF) with good results for the past 15 years.

Surgical technique

Indication for allograft

This technique involves the use of cadaveric tendo-achilles allograft to reconstruct the pectoralis major tendon attachment to the humerus. Because the allograft will usually need to be prearranged, the technique is only indicated when a direct repair is not anticipated. These cases are usually chronic and the musculotendinous unit is markedly retracted. We have found this clinically where the muscle is retracted to the nipple line in the vertical plane without contraction or approximately 4 cm medial to the axilla. We have not found magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to be particularly useful in the decision-making for allograft reconstruction. However, it is difficult to be certain of the need for allograft pre-operatively as a result of variations in muscle mobility after the full release of all adhesions is performed at surgery (similar to a large rotator cuff tear).

Operative details

Surgery is performed under a general anaesthetic with an interscalene block. The patient is positioned supine, prepped and draped, leaving the shoulder and ipsilateral chest wall exposed. The arm is placed in a mobile arm positioner (Trimano; Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA). The skin incision is made superior and medial to the anterior axillary fold, allowing access to the retracted muscle and humerus. Alternatively, the incision may be determined by the palpatory and radiological location of the tendon end. The subcutaneous tissues are dissected and the entire pectoralis major muscle is fully mobilized to the sternal and clavicular attachments, taking care not to injure the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. The mobility and lateral reducibility of the tendon to the humeral insertion can then be determined with the arm in neutral. If this is not easily reducible, then the allograft bridging reconstruction is indicated.

The humeral insertion site is identified and prepared using a small osteotome to roughen the cortical surface, exposing raw bleeding cancellous bone. An area of approximately 3.5 cm × 1 cm is prepared, allowing a footprint repair technique.

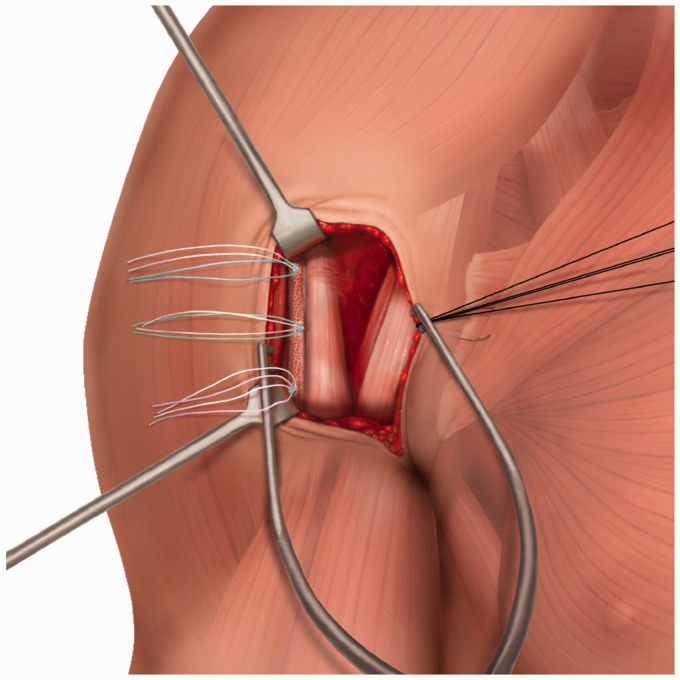

Three double-loaded suture anchors are then placed in the prepared attachment area on the humerus in a triangular pattern with two anchors laterally, superiorly and inferiorly. A third anchor placed medially halfway between the two lateral anchors (Fig. 1). We currently use 2.8-mm Q-Fix all suture anchors (Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA, USA), having previously used 5-mm SuperQuick Anchors (Depuy Mitek, Raynham, MA, USA).

Figure 1.

Three anchors placed in a stepwise longitudinal pattern lateral to biceps to allow a footprint repair.

The proximal end of the tendo-achilles allograft tendon is laid onto the superficial surface of the pectoralis major muscle, with at least 4 cm of coverage (Fig. 2). This is sutured to the pectoralis major muscle and overlying fascia in a quilt technique, with multiple lines of stitching, using No. 2 high strength Orthocord sutures (Depuy Mitek). The stability of this attachment is tested by pulling with force in the line of the muscle towards the humeral insertion. The tendon is then trimmed to size distally to allow appropriate eventual tension (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Proximal end of allograft tendon secured to pectoralis major muscle followed by trimming of tendon distally. Suture anchors are also shown.

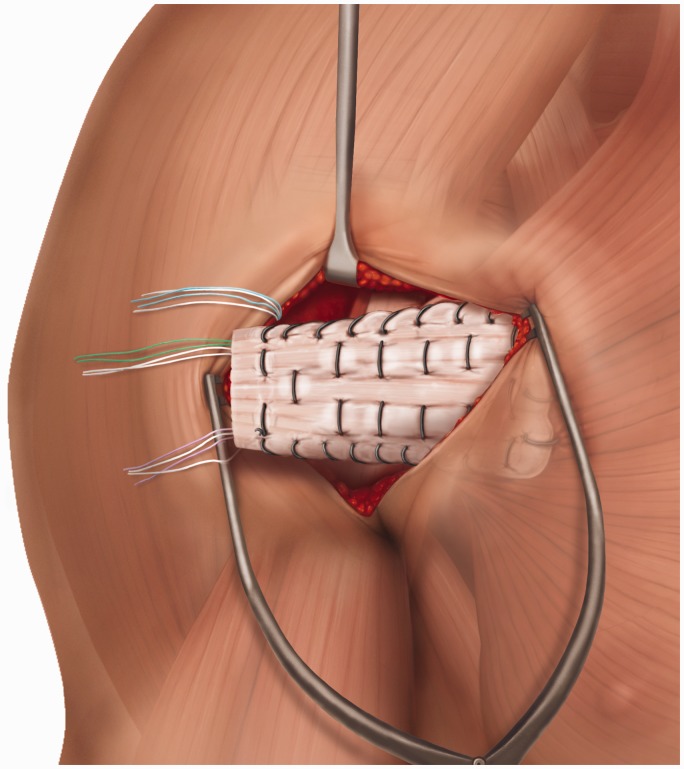

The anchors are sutured to the allograft distally, using the modified whip-stitch technique previously published.7 This creates a footprint of insertion over which the allograft is attached (Figs 3 and 4). During this part of the procedure, it is important to maintain the arm in neutral rotation and avoid letting the arm sag back. The arm positioner is useful for this purpose.

Figure 3.

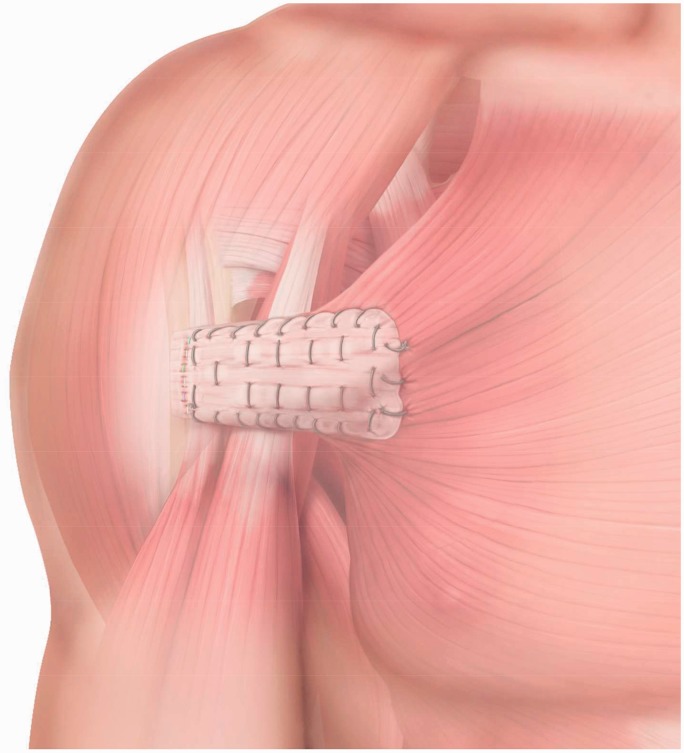

Final appearance: schematic illustration of the final reconstruction.

Figure 4.

Final appearance: clinical photograph post left pectoralis major allograft reconstruction. Note the incision just medial to the axilla.

The safe zone range of motion is assessed by moving the shoulder and assessing the tension of the repair. This is documented for the postoperative rehabilitation. Careful haemostasis is undertaken and the deep and superficial layers closed including the skin. The arm is immobilized in internal rotation with a sling.

Postoperative rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is supervised by a physiotherapist within a comfortable safe zone, as defined at surgery. An arm immobilizer is provided for comfort and worn for sleeping and outdoor activities. Closed chain exercises, under supervision, commence as soon as comfortable postoperatively. Isometric exercises are also allowed within days after surgery as comfort allows. They are advised to not actively contract their pectoralis major muscle. We have also incorporated taping of the pectoralis muscle for the first 2 weeks postoperatively in some cases.

Following review at 3 weeks, patients can progress to active range of motion as tolerated, avoiding stretching or forcing of the shoulder. Progression to resistance exercises usually commences after 6 weeks without forcing or stretching. Most patients return to light open chain resistance weight training at 2 months to 3 months after surgery, although full weight training can take longer. We do advise against bench pressing beyond 90° (or the neutral coronal plane) again.

Preliminary outcomes

We performed a total of 142 pectoralis major repairs over a 10-year period, of which 19 required allograft reconstruction. Of these 19 patients, 11 were available for response. All 11 patients were male with a mean age of 38.3 years (21 years to 48 years). The mean time between injury and surgery was 12.2 months (4 months to 30 months). The commonest mechanism of injury was the bench press (72.7%), with the others being rugby tackle, motorcycle and skiing injuries. One patient had a previous failed direct repair. The mean time between operation and review was 45.5 months (9 months to 86 months). All patients were manual workers or professional athletes. Ten patients (91%) were unable to perform their previous level of work pre-operatively, with all patients returning to pre-injury occupation levels postoperatively. The main complaint prior to surgery was pain on pushing and moving the affected arm across the body, which improved in nine patients (82%), with no improvement reported in two patients. Strength improved significantly postoperatively, with only three patients reporting no improvement (paired t-test p = 0.01). Six patients reported an improvement in cosmesis (50%). We are currently undertaking a more detailed outcomes study, which will include postoperative MRI scans.

Discussion

Pectoralis major ruptures are increasingly reported and occur most commonly at the humeral insertion.1,2 Although non-operative management has been used for older low functional demand patients, surgery is more commonly advised for young patients, sportsmen, manual workers and other high demand groups.2,4,5,10,11

Musculotendinous retraction is a well recognized feature over time and makes primary repair more difficult10,11. Joseph et al.12 reported a case where direct repair of a pectoralis major rupture was not possible eight weeks after injury and an allograft reconstruction was required, whereas Alho et al.13 described a similar case where direct primary repair was difficult 12 weeks after injury. In this situation, the repair may be performed under tension, which places the repair at risk during rehabilitation and may predispose to shoulder pain and stiffness. Alternatively, a technique of medial fascial release through a separate incision has been described allowing advancement of the pectoralis major tendon to the normal point of insertion. This technique has been used to gain up to 2 cm of additional length and to allow direct repair, although it may incur an additional risk of injury to the pectoral nerves during medial fascial release and dissection.13

It has been suggested and appears intuitive that partial tears are less likely to retract in this way because residual tendinous fibres act as a tether holding the musculotendinous unit out to length. This has allowed direct surgical repair as late as 13 years after injury.14 However, in some cases with more extensive musculotendinous injury, it may be necessary to overcome shortening. We have found allograft reconstruction to be useful in this situation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical review and patient consent

All patients in this study signed consent forms for their anonymized data to be used for scientific and research purposes. Data was analyzed retrospectively and there was no change in the patients' standard of care or decision-making.

References

- 1.Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Tramatol Arthrosc 2000; 8: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pochini A, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV, et al. Pectoralis major muscle rupture in athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38: 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakwaki RG, Matthews JJ, Mohtadi N. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: surgical treatment in athletes. Int Orthop 2007; 31: 159–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petilon J, Carr DR, Sekiya JK, Unger DV. Pectoralis major muscle injuries: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005; 13: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butt U, Mehta S, Funk L, Monga P. Pectoralis major ruptures: a review of current management. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butt U. Pectoralis major. In: Monga P, Funk L. (eds). Diagnostic clusters in shoulder conditions, Cham: Springer, 2017, pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah NH, Talwalker S, Badge R, Funk L. Pectoralis major rupture in athletes: footprint technique and results. Tech Should Elbow Surg 2010; 11: 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sikka RS, Neault M, Guanche CA. Reconstruction of the pectoralis major tendon with fascia lata allograft. Orthopedics 2005; 28: 1199–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zacchilli MA, Fowler JT, Owens BD. Allograft reconstruction of chronic pectoralis major tendon ruptures. J Surg Orthop Adv 2013; 22: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schepsis AA, Grafe MW, Jones HP, Lemos MJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Sports Med 2000; 28: 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkila J, Helttula I, Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32: 1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph TA, Defranco MJ, Weiker GG. Delayed repair of a pectoralis major tendon rupture with allograft: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alho A. Ruptured pectoralis major tendon: a case report on delayed repair with muscle advancement. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; 65: 652–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anbari A, Kelly JD, Moyer RA. Delayed repair of a ruptured pectoralis major muscle. A case report. Am J Sports Med 2000; 28: 254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]