Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Engaging with parents in care improves pediatric care quality and patient safety; however, parents of hospitalized children often lack the information necessary to effectively participate. To enhance engagement, some hospitals now provide parents with real-time online access to information from their child’s inpatient medical record during hospitalization. Whether these “inpatient portals” provide benefits for parents of hospitalized children is unknown. Our objectives were to identify why parents used an inpatient portal application on a tablet computer during their child’s hospitalization and identify their perspectives of ways to optimize the technology.

METHODS:

Semistructured in-person interviews were conducted with 14 parents who were given a tablet computer with a commercially available inpatient portal application for use throughout their child’s hospitalization. The portal included vital signs, diagnoses, medications, laboratory test results, patients’ schedule, messaging, education, and provider pictures and/or roles. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and continued until reaching thematic saturation. Three researchers used an inductive approach to identify emergent themes regarding why parents used the portal.

RESULTS:

Five themes emerged regarding parent motivations for accessing information within the portal: (1) monitoring progress, (2) feeling empowered and/or relying less on staff, (3) facilitating rounding communication and/or decision-making, (4) ensuring information accuracy and/or providing reassurance, and (5) aiding memory. Parents recommended that the hospital continue to offer the portal and expand it to allow parents to answer admission questions, provide feedback, and access doctors’ daily notes.

CONCLUSIONS:

Providing parents with real-time clinical information during their child’s hospitalization using an inpatient portal may enhance their ability to engage in caregiving tasks critical to ensuring inpatient care quality and safety.

Effective parent-provider communication is a necessary component to ensuring that children who are hospitalized receive safe and high-quality care.1 Unfortunately, hospitalizations pose unique challenges for parents. Often sleep-deprived and meeting their child’s inpatient provider for the first time, parents are inundated with information that is rarely supplemented with written materials and are expected to make quick, informed, high-stakes decisions during morning rounds. As a result, substantial information gaps exist between parents and providers, with 45% of parents in 1 study lacking a shared understanding about their child’s care plan with their inpatient provider.2

To narrow this information gap, a growing number of hospitals offer patients and caregivers “inpatient portals.” Inpatient portals are Web-based applications on tablet computers that provide real-time access to clinical information from the electronic health record (EHR) (eg, diagnoses, medications, test results, and education).3 Research with adult inpatients and/or caregivers4–17 and families of children who are hospitalized and undergoing a bone marrow transplant18–21 suggests that use of an inpatient portal may play a role in improving patient and caregiver knowledge. Whether inpatient portals would similarly be used by and provide benefits for parents of children hospitalized with general medical and surgical conditions was unknown.

To address these gaps, we first conducted a pilot study to evaluate parent use of a commercially available inpatient portal application (MyChart Bedside; Epic Systems, Verona, WI) after its implementation on a pediatric medical and/or surgical unit.22,23 Over 6 months, 329 parents were offered the portal application on a hospital-owned tablet computer. Of these, 296 (90.0%) used it during their child’s hospitalization.22 According to tablet data, parents most frequently accessed features that provided information about their child’s inpatient vital signs, diagnoses, medications, providers, daily schedule, and test results. Our objective for this qualitative follow-up study was to identify why parents used the portal, their suggestions for improvement, and their perspectives of new features being considered by the hospital.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

In this qualitative study, semistructured in-person interviews were conducted with parents of children hospitalized on a general medical surgical unit in a tertiary care children’s hospital in the Midwest starting in September 2016. On this 24-bed unit, children with acute or chronic conditions are admitted to 1 of multiple pediatric services, including hospitalist, subspecialty, surgery, or rehabilitation. As standard practice on admission, nurses give parents of hospitalized children <12 years old a tablet computer (Apple iPad 32 GB; Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) to use throughout the hospitalization. This tablet includes an online inpatient portal application linked to real-time clinical information from their child’s EHR. On discharge, tablets are collected, cleared of data, and reissued to subsequent parents.

In this study, available English-speaking parents were eligible and approached if their child had been admitted to any bed on the unit for >24 hours. Parents who did not speak English were excluded because of limitations of the inpatient portal technology to provide only English-language content. Parents of children 12 years and older were excluded because of legal limitations on the ability of parents to access certain adolescent health information.

The EHR and Inpatient Portal

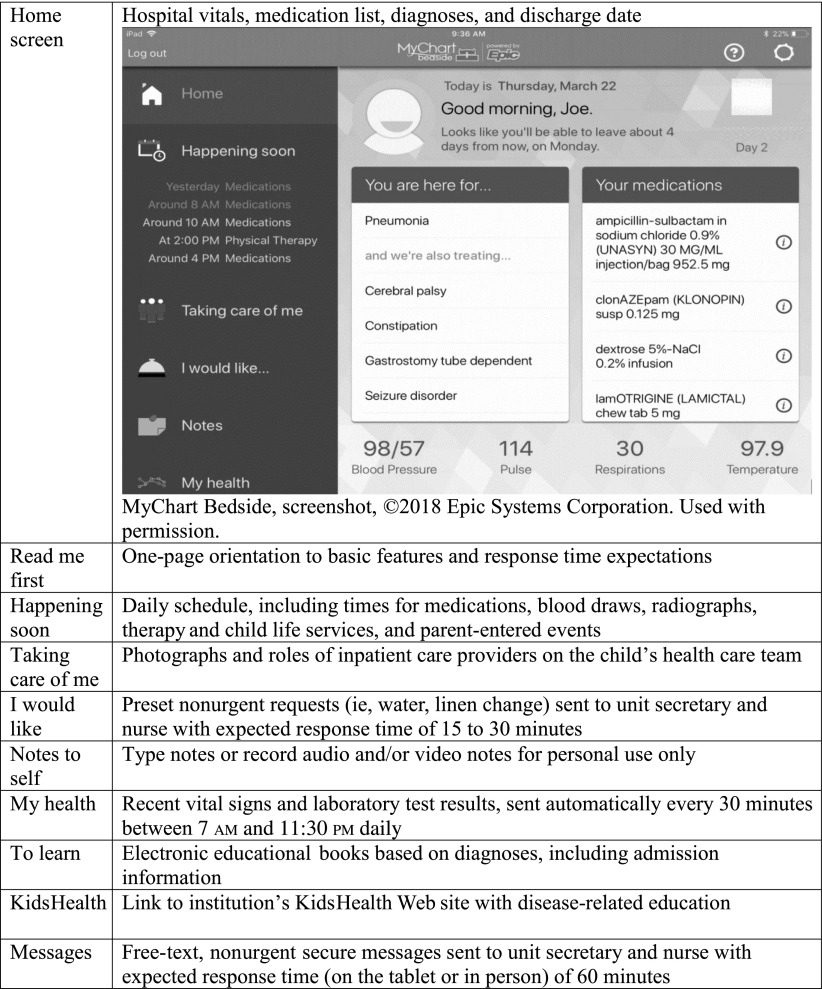

At this organization, an EHR (Epic Systems) has been used since 2008, an outpatient portal (MyChart) since 2009, and an inpatient portal (MyChart Bedside; Fig 1) since 2015. Linked to hospital EHR data, this inpatient portal application is given to parents on a hospital-owned tablet. It provides parents with real-time access to clinical information about their child’s hospital stay. The inpatient portal’s features and hospital staff expectations are outlined in Fig 1, including an orientation to features, expected staff response times, release frequency of laboratory test results, and educational content. Drug testing, pregnancy, tumor markers, culture, and radiology and pathology test results are not released to the inpatient portal. During this study, tablets did not include access to the Internet more broadly or other applications.

FIGURE 1.

Inpatient portal home screen and descriptions of portal features. Adapted from Kelly MM, Hoonakker PL, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):153–161.

Interview Guide

We constructed and piloted a semistructured interview guide, which can be accessed in the free online toolkit.24 Interview domains and example probes are included in Table 1. Interview questions were included to capture parent and child characteristics, including parent sex, number of previous child hospitalizations (excluding birth), number of days currently hospitalized, previous outpatient portal use, whether they were shown how to use the inpatient portal, and average daily use.

TABLE 1.

Parent Semistructured Interview Script Domains and Example Probes

| Interview Domain | Example Probes |

|---|---|

| Why parents used the inpatient portal | Why did you use the inpatient portal? |

| Usefulness of the portal | How useful did you find the portal? What feature(s) were most useful? What feature(s) did you like the most? Why? |

| Suggestions for improvement | How do you like this feature? What could be done to improve this feature? |

| Whether the hospital should keep using the portal | Would you recommend that we keep using the portal at this hospital? Why or why not? |

| Future inpatient portal features | |

| Admission and discharge surveys | The nurse asked you many questions on admission. How would you feel about filling this survey out yourself by using the portal instead? |

| Usually we send a paper survey to your home asking about your experiences at the hospital. How would you feel about completing the survey on this tablet in the hospital before leaving the hospital? | |

| Sharing doctors’ inpatient notes | How would you feel about being able to see your child's doctor’s daily notes through the portal? |

| Patient safety reporting | Were any mistakes or errors made during your child’s hospital stay? |

| Would you consider reporting problems, errors, or mistakes by using the portal? Can you tell me more about it? |

Data Collection Procedure

A convenience sample of parents was recruited on weekdays from 9 am to 12 pm, when research staff was available. Eligible parents were identified by the unit secretary through the EHR, approached by the nurse, and offered a study information sheet. A researcher (M.M.K. and P.L.T.H.) approached parents willing to learn more about the study and obtained informed consent. Consenting parents were interviewed in a location of their choice (at the bedside or in a private conference room). Researchers (M.M.K. and P.L.T.H.) met regularly to review emerging themes, and recruitment continued until thematic saturation (the point at which no new themes emerged despite additional interviews25) regarding why parents used the inpatient portal was reached. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Audio recordings and any identifying information unintentionally collected were deleted after transcription was complete. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board of the study site approved this study.

Data Analysis

Interview transcript data were uploaded to DeDoose (www.dedoose.com), which is software that is used to assist with qualitative data management and analysis. Parent-reported characteristics were analyzed by using descriptive statistics. Interview text was systematically categorized into themes by using a standard inductive, qualitative content analysis approach.26,27 Three researchers trained in qualitative methods (M.M.K., P.L.T.H., and A.S.T.) independently reviewed data and then generated the thematic coding scheme through consensus. Interview data were then independently coded, and discrepancies were again resolved through consensus.

Results

Of 16 approached, 14 parents consented and completed an interview. Interviews each lasted from 24 to 65 minutes. Parent and child characteristics are shown in Table 2. Parents were predominantly mothers (86%), had access to the inpatient portal for 2 to 20 days (mean: 6 days; median: 3 days), and reported using it an average of 2 times per day (range: 1–5 times per day).

TABLE 2.

Parent Participant–Reported Characteristics and Inpatient Portal Use, N = 14

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Parent participant sex | |

| Female | 12 (86) |

| Previous child hospitalizationsa | |

| None | 5 (36) |

| 1–2 | 3 (21) |

| 3–4 | 1 (7) |

| >5 | 5 (36) |

| Previous ambulatory patient portal useb | 7 (50) |

| Previous inpatient portal useb | 4 (29) |

| Instructed how to use the inpatient portal by nurses on admission | 14 (100) |

| Days with inpatient portal during current hospitalization | |

| 1–2 | 3 (21) |

| 3–4 | 6 (43) |

| 5–10 | 2 (14) |

| >10 | 3 (21) |

| Average daily use of the inpatient portal during current hospitalization, logins per d | |

| <2 | 7 (50) |

| 2–3 | 5 (36) |

| >3 | 2 (14) |

Number of previous hospitalizations of participant’s child who is currently admitted, not including birth or current hospitalization.

Before current hospitalization.

Parent Perceptions of the Inpatient Portal

Five themes emerged regarding parent motivations for accessing information within the portal: (1) monitoring their child’s progress, (2) feeling empowered and/or relying less on staff, (3) facilitating communication and/or decision-making on rounds, (4) ensuring information accuracy and/or providing reassurance, and (5) aiding memory. Themes and representative quotes are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Themes and Representative Quotes Related to Parent Participant Motivations for Using the Inpatient Portal

| Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Monitoring their child’s progress | “I appreciated the medication tracking and the blood pressure, pulse, temperature, respiration tracking.” (Parent B) |

| “We were really keeping an eye on [his pulse], so it was nice to see that trajectory.” (Parent A) | |

| Feeling empowered and/or relying less on staff | “It gives you a sense of control…I don’t always want to have to ask, ‘Did this happen, did this get done?’ It’s not that I’m worrying about bothering people, but you also recognize that there’s a lot going on, and so it kind of gives you, some of those questions you might have, you can get answered with this.” (Parent B) |

| “You kind of more feel free with it. You’re not having to rely so much on the staff, where you can look and see the test results and see all that stuff. Like, we really like that instead of waiting for a nurse to come into the room to log into the computer, find your child’s information, look for the results you’re questioning…” (Parent D) | |

| Facilitating communication and/or decision-making on rounds | “I receive the results before the rounds. I have time to prepare, and I can ask questions, and [the] doctor can give me better answer[s].” (Parent F) |

| “I was putting stuff in there [to] bring up during the rounds in the morning.” (Parent E) | |

| “I showed [the heart rate and blood pressure trends] to them, and that was part of what created that change [in the plan].” (Parent B) | |

| Ensuring information accuracy and/or providing reassurance | “I check on the home screen to see that they have the medications right.” (Parent D) |

| “I knew that the nurses had everything under control, but it was for my peace of mind.” (Parent E) | |

| Aiding memory | “I can remember, or it can remember for me.” (Parent A) |

Parent Suggestions for Improvement

Parent quotes representing their perceptions of the usefulness and suggestions for improvement of each portal feature are show in Table 4. Parents made multiple suggestions, including modifications to the portal interface (eg, highlighting medication changes), content (eg, releasing more information and simplifying educational materials), and explanation of features (eg, clarifying expectations for where messages go and response expectations). Parents recognized that it was possible that they could see laboratory test results before providers but didn’t think that the release frequency of results should be changed: “I don’t mind that. I think that’s kind of the nature of [it]. I’m focusing on one thing, and they’re focusing on my child and other children” (Parent A).

TABLE 4.

Representative Parent Quotes of Usefulness and Suggestions for Improvement of Each Inpatient Portal Feature

| Inpatient Portal Feature | Why Was It Useful? | What Could Be Done to Improve This Feature? |

|---|---|---|

| Home screen: vital signs, discharge date, and problem and/or medication list | “…being able to check where his blood pressures were and where his heart rate has been.” (Parent D) | “The discharge date wasn’t always updated.” (Parent A) |

| “Maybe if there was a subcategory that said this med was changed, if there’s a dosage change, or if there’s a new medication.” (Parent D) | ||

| Happening soon: child’s daily schedule | “I like seeing the medication schedule...if I go outside or go for a walk and I’m not always sure if he got his medication, I can check on here and see if they did it.” (Parent B) | “It would also be nice to see when he’s scheduled for physical therapy and when the resident is going to be coming by, what needs to be done for discharge and what are our goals for the day.” (Parent A) |

| “[I would like to see] the whole day, the whole week in one picture.” (Parent F) | ||

| Taking care of me: photographs and names of the care team | “It’s overwhelming to see so many people at once, and it was nice to take a look back later and say, ‘Okay, I remember.’” (Parent I) | “It would be nice to see maybe if there was two tabs…see who is taking care but who had taken care of me in the past.” (Parent A) |

| I would like: requests for nonurgent items | “…to be able to have a way to communicate with the nurses in a non-emergent way, I think it’s nice.” (Parent L) | “I don’t know what happens to this. Does this buzz my nurse who’s connected to me? Maybe having that better clarification…Where does it go?.” (Parent A) |

| Note to self: parent text, audio, and video notes | “I was putting stuff in there to bring up during the rounds.” (Parent E) | “It would be helpful to see this note to self in outpatient MyChart.” (Parent E) |

| My health: laboratory test result trends (released every 30 min, 7 am–11 pm) | “I find [it] useful that I don’t have to ask the nurses or bother the nurses about how his labs are…” (Parent J) | “I think it could be better with the linked information for, like, what exactly a test does…” (Parent D) |

| To learn: e-books of admission information | “There were quite a few [education materials].” (Parent D) | “I don’t have enough time to read the long article, but if there’s any like abstract or simple things…” (Parent F) |

| KidsHealth: KidsHeath Web site | “...it gave, you know, nice basic information, you know, so, and that's good.” (Parent B) | No improvements described by parents: “Nope. It’s perfectly good the way it is.” (Parent J) |

| Messaging: secure, nonurgent messages for the care team | “[It is useful] to message the doctor, and then when he gets the time, he can see it and then message back.” (Parent E) | “…it seemed like it took a long time for [staff] to reply. Maybe have an auto-response when if, like, they’re going to come talk to you in person.” (Parent D) |

e-book, electronic book; lab, laboratory test results; med, medication.

Thirteen parents recommended that the hospital continue to offer parents access to the portal. Although they emphasized that parents might use the portal differently, interviewees thought providing parents with the option was important: “Some people will probably use it more, and maybe people will use it less, but I think access is what is most important—just getting it to them and saying, ‘This is for you, use it as you will.’ I think it’s a great tool” (Parent H). The remaining parent was positive about its potential but had multiple suggestions: “Right now, it has a nice foundation to be really useful. This is clearly just kind of pulling a little bit from his current record, and [staff] are not being interactive with it. I think it would be nice to have the nursing staff really be on board and talk about it and…be the ones to sit there and kind of advocate for it” (Parent A). Other parents wanted the hospital to continue to use the portal but requested increased access to information: “It would be nice to have access to all of his chart, not just selective pieces” (Parent B).

Additional Inpatient Portal Features

Parents were open to additional portal features being considered by the hospital.

Admission and Discharge Surveys

Parent participants were willing to use the portal to answer questions currently asked by nursing staff on admission (eg, child’s vaccination status and chicken pox exposure) and about their experience in the hospital. Some parents preferred to use the tablet to answer these questions: “If we can just read it ourselves, we can get it done a lot quicker” (Parent D) and “[w]ould more likely respond [to a tablet discharge survey] than getting a piece of mail” (Parent G). Other parents had reservations about completing nonemergent tasks on the tablet: “It might not be the best idea because when you are being admitted, that’s usually not the thing on your mind” (Parent K) and “[answering discharge questions] might be hard because [we are] also trying to make sure we’ve got everything” (Parent D).

Inpatient Doctors’ Notes

Of 14 parents, 13 were interested in having access to their child’s inpatient doctor’s notes in the portal: “I don’t know that doctors necessarily keep it a secret, but in my son’s entire medical history, I’ve only had one doctor really turn the screen to me and sit there and say like ‘Here’s what we’re seeing, here’s what’s happening.’ So, if I could see things like [notes] in here, that would be amazing” (Parent A). Parents suggested that notes would improve their ability to remember their child’s plan and improve understanding: “Sometimes talking is different than writing. Sometimes I will forget the point. [With notes], we’ll know where’s the problem and what’s the next step” (Parent F) and “When you read, you can understand it much better” (Parent C). Others suggested that they would like to refer to notes when they were unavailable during rounds: “I wasn’t here [during rounds]. So, if they say the doctor’s notes are on there, I could be able to read them and see what [the doctor’s] suggesting” (Parent J). Other parents had reservations: “It could be too much information in the wrong hands” (Parent L) and “I don’t know how comfortable [doctors] would feel. It may feel like an invasion of [doctors’] privacy” (Parent H).

Patient Safety Reporting

Parents would consider using the portal’s messaging feature to report a concern, mistake, or error: “I think that would be a nice way to [report concerns]…it’s still linked to you, but you can think through what you’re saying, and maybe present [it] a little bit clearer” (Parent L). Others would prefer to report mistakes/errors in person because of concerns about communication timeliness and/or the potential of being misunderstood through online communication: “I do prefer a face-to-face [communication]…everybody knows if you really want to get misunderstood, then you send a message” (Parent B).

Discussion

This study is the first to reveal why parents used an inpatient portal during their child’s hospitalization. Parents used it to access information, which facilitated their ability to monitor their child’s progress, remember the care plan, ensure information accuracy, and communicate during rounds. The portal also provided a sense of empowerment and the ability for some parents to feel less reliant on staff. Participants recommended that the hospital continue to offer parents the portal and had multiple suggestions for improvement, such as increasing the amount of their child’s EHR information that is released. These findings could help vendors, health care organizations, researchers, and policy makers optimize inpatient portals and their implementation and inform next steps toward rigorous evaluation of the effects of their use.

Our findings complement those of studies conducted with adults who were hospitalized and their caregivers.11,12,14 In 1 qualitative study, adult inpatients similarly used an inpatient portal to obtain information to monitor, understand, remember, engage in, and ensure the safety of their care.14 In fact, authors highlighted the potential for adult patients to find errors in their medication list using their inpatient portal14 (a finding reinforced through our study). Children who are hospitalized are particularly vulnerable to medical errors,28 and parents play an important role in identifying and reporting errors.29 By providing parents with access to information through inpatient portals, they may be able to better identify potential errors and alert providers, who can take action and prevent harm. It is important to note, however, that parents were less comfortable with using the portal as a mechanism to report their safety concerns.

Overall, parents’ experiences with the inpatient portal were positive, and their suggestions were focused on expanding (as opposed to fixing) portal functionalities. Parents desired more information, specifically the ability to view their child’s physician’s notes. This sentiment has been echoed by adult inpatients in other studies.6,12–14 OpenNotes is an international movement in which providers are encouraged to give patients online access to their notes,30 which routinely detail the patients’ diagnoses, progress, and treatment plan. Results from studies of adult patients in the ambulatory setting reveal that providing access to notes may help patients remember their care plan, ensure information accuracy, and feel more in control of their care.31–33 However, many physicians fear that sharing their inpatient notes will result in unintended negative consequences,34 such as disclosure of information that could lead to patient anxiety, confusion, anger, and loss of trust and privacy and/or increase litigation. These concerns are heightened in pediatrics with the complexities of protection of children and of access for adolescents.35,36 Future research is needed to evaluate how to optimally share physician notes through inpatient portals to support parents as true partners in hospital care while mitigating negative consequences.

It was notable that parents did not have concerns about the possibility of seeing test results before their provider. To the contrary, parents used the portal to access test results and other information so that they did not have to rely as much on staff. Although directly releasing test results in patient portals appears to be valued by patients in the ambulatory setting37 and may enhance their engagement, it has the potential to increase patient anxiety and health care use.38 Our organization chose not to release certain laboratory test results, such as drug testing, pregnancy, tumor markers, and pathology results. Organizations may need to make such decisions, accounting for local context, to offset the potential negative effects of releasing this information directly to patients and families. The optimal types and timing of release of results through inpatient portals in the acute hospital setting is unknown and is an important area for investigation.

More than simply tools for displaying information, inpatient portals could be used to capture parent-reported data (eg, admission and discharge questionnaires) and facilitate more meaningful parent-provider communication, thus having the potential to help parents become more effective partners in their child’s care. Although the expansion of portal functions could further foster parent engagement, it should be approached carefully and after consideration of privacy protections, usability testing,39 and integration within complex hospital workflows and processes (eg, rounds). The impact of inpatient portal use on provider workload and health services use (eg, length of stay, readmissions, outpatient engagement, and visits) and costs associated with technology implementation and maintenance also need to be quantified.

Whether the use of inpatient portals ultimately translates to demonstrable improvements in meaningful health constructs is largely unknown. Among adult patients, interventional studies used to evaluate the effect of inpatient portal use on process and outcome measures are emerging with mixed results. In the only published controlled trial used to evaluate the effect of inpatient portal use,9 adult inpatients with access to the portal had improved knowledge of provider names and roles compared with those receiving usual care. However, there was no significant difference in patient engagement or knowledge about planned medications, tests, and procedures. In another study, portal implementation in an adult ICU was associated with a significant increase in patient satisfaction and reduction in adverse events but no change in care plan concordance.40 Future comparative-effectiveness research in the pediatric setting should be used to clarify the effect of inpatient portal use on parent knowledge, engagement, and experience; parent-provider communication; shared decision-making; and patient safety (eg, safety perceptions, diagnostic errors, and adverse drug events).

This study had several limitations. We evaluated the use of 1 inpatient portal by English-speaking parents of children hospitalized on a single pediatric medical surgical unit, which limit the generalizability of findings. However, these findings may be useful for those organizations that are considering implementing this commercially available portal or for the 140 organizations that are already committed to using it (J. Campbell, personal communication, 2018). The design and use of inpatient portals by non–English-speaking patients and caregivers and hospitalized adolescents are important areas for future study. Interviews were completed with a convenience sample of parents available on weekdays, which may reflect a more engaged population of parents. Although we collected participant information on previous outpatient portal use, we did not capture their age or experience with technology in general, nor did we link their reported use to actual use using tablet data. Identifying parent portal use timing and trends and parent and child characteristics associated with use is an important area for future research. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation regarding why parents used the portal was reached. Thus, this qualitative study was not designed to detect differences in parent use or perceptions across characteristics (eg, previous ambulatory patient portal use).

Although engaging parents in the care of their child improves health outcomes,41 limited evidence-based interventions exist to truly engage parents as partners in the inpatient setting.42 Providing parents with real-time clinical information during their child’s hospitalization by using an inpatient portal may enhance their ability to engage in the caregiving tasks endorsed as essential to improving pediatric patient safety and the quality of hospital-based care.

Acknowledgments

We thank parent portal users, unit staff, and the portal implementation and steering committees for their valuable feedback and support.

Footnotes

Dr Kelly conceived and designed the study, led data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and drafted and revised the manuscript; Ms Thurber participated in data analysis and interpretation and made critical manuscript revisions; Drs Coller, Khan, and Dean, and Ms Smith substantially contributed to data interpretation and made critical manuscript revisions; Dr Hoonakker assisted with study design and data collection and analyses and made critical manuscript revisions; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards program through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant UL1TR000427). Dr Hoonakker’s involvement in the study was also partially supported by National Science Foundation grant CMMI 1536987. The funding agencies had no involvement in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data nor in the decision regarding manuscript submission. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Stucky ER; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan A, Baird J, Rogers JE, et al. Parent and provider experience and shared understanding after a family-centered nighttime communication intervention. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):389–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly MM, Coller RJ, Hoonakker PL. Inpatient portals for hospitalized patients and caregivers: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:1428–1435 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caligtan CA, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, Gersh-Zaremski R, Dykes PC. Bedside information technology to support patient-centered care. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(7):442–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dykes PC, Stade D, Chang F, et al. Participatory design and development of a patient-centered toolkit to engage hospitalized patients and care partners in their plan of care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:486–495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo S, Lee KH, Baek H, et al. Development and user research of a smart bedside station system toward patient-centered healthcare system. J Med Syst. 2015;39(9):86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin CT. Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):856–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, Killarney A, Randy Smith G, Jr, Liebovitz DM. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, et al. Acute care patient portals: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e9–e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: a preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):80–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, et al. Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions of a mobile portal application for hospitalized patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcox L, Woollen J, Prey J, et al. Interactive tools for inpatient medication tracking: a multi-phase study with cardiothoracic surgery patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):144–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):446–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huerta TR, McAlearney AS, Rizer MK. Introducing a patient portal and electronic tablets to inpatient care. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):816–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker DM, Menser T, Yen PY, McAlearney AS. Optimizing the user experience: identifying opportunities to improve use of an inpatient portal. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(1):105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen PY, Walker DM, Smith JMG, Zhou MP, Menser TL, McAlearney AS. Usability evaluation of a commercial inpatient portal. Int J Med Inform. 2018;110:10–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maher M, Hanauer DA, Kaziunas E, et al. A novel health information technology communication system to increase caregiver activation in the context of hospital-based pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(4):e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):94–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher M, Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, et al. User-centered design groups to engage patients and caregivers with a personalized health information technology tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(2):349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Runaas L, Hanauer D, Maher M, et al. BMT roadmap: a user-centered design health information technology tool to promote patient-centered care in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(5):813–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PL, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly MM, Dean SM, Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Hoonakker PL. Healthcare team perceptions of a portal for parents of hospitalized children before and after implementation. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):265–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Partnering With Parents of Hospitalized Children Using an Inpatient Portal. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Department of Pediatrics, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program; 2017. Available at: www.hipxchange.org/InpatientPortal. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1st ed. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P, Rogers JE, Schuster MA, Landrigan CP. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):e154608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.OpenNotes. Available at: https://www.opennotes.org/. Accessed June 15, 2018

- 31.Delbanco T, Walker J, Darer JD, et al. Open notes: doctors and patients signing on. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(2):121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell SK, Gerard M, Fossa A, et al. A patient feedback reporting tool for OpenNotes: implications for patient-clinician safety and quality partnerships. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(4):312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes: hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):414–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourgeois FC, DesRoches CM, Bell SK. Ethical challenges raised by OpenNotes for pediatric and adolescent patients. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chimowitz H, Gerard M, Fossa A, Bourgeois F, Bell SK. Empowering informal caregivers with health information: OpenNotes as a safety strategy. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(3):130–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krasowski MD, Grieme CV, Cassady B, et al. Variation in results release and patient portal access to diagnostic test results at an academic medical center. J Pathol Inform. 2017;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pillemer F, Price RA, Paone S, et al. Direct release of test results to patients increases patient engagement and utilization of care. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0154743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Britto MT, Jimison HB, Munafo JK, Wissman J, Rogers ML, Hersh W. Usability testing finds problems for novice users of pediatric portals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):660–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dykes PC, Rozenblum R, Dalal A, et al. Prospective evaluation of a multifaceted intervention to improve outcomes in intensive care: the promoting respect and ongoing safety through patient engagement communication and technology study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):e806–e813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAllister JW, Sherrieb K, Cooley WC. Improvement in the family-centered medical home enhances outcomes for children and youth with special healthcare needs. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32(3):188–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan A, Cray S, Mercer AN, Ramotar MW, Landrigan CP. Engaging families as true partners during hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(5):358–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]