Abstract

Context

Behavioral studies suggest that responses to food consumption are altered in children with obesity (OB).

Objective

To test central nervous system and peripheral hormone response by functional MRI and satiety-regulating hormone levels before and after a meal.

Design and Setting

Cross-sectional study comparing children with OB and children of healthy weight (HW) recruited from across the Puget Sound region of Washington.

Participants

Children (9 to 11 years old; OB, n = 54; HW, n = 22), matched for age and sex.

Intervention and Outcome Measures

Neural activation to images of high- and low-calorie food and objects was evaluated across a set of a priori appetite-processing regions that included the ventral and dorsal striatum, amygdala, substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area, insula, and medial orbitofrontal cortex. Premeal and postmeal hormones (insulin, peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide-1, active ghrelin) were measured.

Results

In response to a meal, average brain activation by high-calorie food cues vs objects in a priori regions was reduced after meals in children of HW (Z = −3.5, P < 0.0001), but not in children with OB (z = 0.28, P = 0.78) despite appropriate meal responses by gut hormones. Although premeal average brain activation by high-calorie food cues was lower in children with OB vs children of HW, postmeal activation was higher in children with OB (Z = −2.1, P = 0.04 and Z = 2.3, P = 0.02, respectively). An attenuated central response to a meal was associated with greater degree of insulin resistance.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that children with OB exhibit an attenuated central, as opposed to gut hormone, response to a meal, which may predispose them to overconsumption of food or difficulty with weight loss.

Using functional neuroimaging to test visual food cue responses before and after a meal, we found an attenuated central satiety and normal gut hormone response in 9- to 11-year-old children with obesity.

Behavioral studies demonstrate that uncontrolled eating, poor satiety responsiveness, and increased eating in the absence of hunger (1, 2) are more frequent among children with obesity (OB), who also find food more reinforcing (3) and are more responsive to food cues (2) than are children of healthy weight (HW). Altered circulating levels of satiety-related hormones (4, 5) are one possible explanation for such findings. Alternatively, previous functional MRI (fMRI) studies demonstrated hyperactivation in response to food images in reward regions in adults with OB (6, 7), potentially enhancing perception or anticipation of food reward (8–10). Existing findings suggest that children with OB are also hyperresponsive to food images in brain regions linked to motivation, reward, and cognitive control (11–13). These findings all point to the potential for a neurobiological basis of disturbed satiety in childhood OB, but the relationship and relative importance of peripheral hormone vs central responses remain uncertain.

To address these questions, we used fMRI to assess children’s central response to a standardized meal in a set of key appetite-processing brain regions that included the ventral striatum (VS), dorsal striatum (DS), medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), amygdala, substantia nigra (SN)/ventral tegmental area (VTA) and insula. The degree of response to high-calorie food cues within these regions is heightened by fasting (14), is responsive to satiety-regulating hormones (15–17), reflects subjective satiety (18), and, critically, also predicts food choice and caloric intake (18, 19). We simultaneously monitored concentrations of circulating appetite-regulating hormones and glucose, all of which are known to modulate activation by food cues within several of these regions (15, 17, 20, 21).

We investigated the hypothesis that, in the selected brain regions noted above, children with OB would not reduce activation by high-calorie food cues after eating a standardized test meal relative to children of HW. We furthermore hypothesized that a hunger-promoting hormonal profile would be related to fMRI findings.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Fifty-four children with OB [53 with body mass index (BMI) >95th percentile, 1 with BMI of 94th percentile for sex and age] with at least one overweight parent (BMI >27 kg/m2) were enrolled and committed to 6 months of family-based behavioral treatment of OB (current study includes only pretreatment data). Controls were 22 children of HW (BMI 5th to 85th percentile) (22). Both groups were 9 to 11 years old and were recruited through advertisements and direct mailings. Exclusion criteria included serious medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, cognitive disorders); contraindications to MRI; inability to consume study foods (e.g., allergies, vegetarianism); and current use of medications known to alter appetite, body weight, or brain response (e.g., antiepileptics, glucocorticoids, stimulants). Parents provided consent, children provided assent. The study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

Study procedures

The study visit occurred prior to treatment of the group with OB. Study visit procedures are detailed in Fig. 1A. Participants arrived fasted (≥10 hours), underwent IV placement and a blood draw, and, 30 minutes later, were given a standardized breakfast (milk, toast with butter and jam) representing 10% of their estimated daily caloric requirements (15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrate; calculated with the Mifflin–St. Jeor equation and a standard activity factor of 1.3) (23). All participants finished breakfast within 15 minutes [mean kilocalories consumed (range): HW, 143 kcal (113 to 167); OB, 186 kcal (153 to 286)] except for one participant with OB who consumed ∼75% of the meal. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (Quantum II; RJL Systems, Detroit, MI) was used to assess body composition 1 hour after breakfast and parameters were calculated by validated methods (24, 25). Hydration was standardized for bioelectrical impedance analysis to 8 ounces (237 mL, HW) or 12 ounces (355 mL, OB) of water intake. Height, weight, and waist circumference measurements were obtained using standardized procedures (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm).

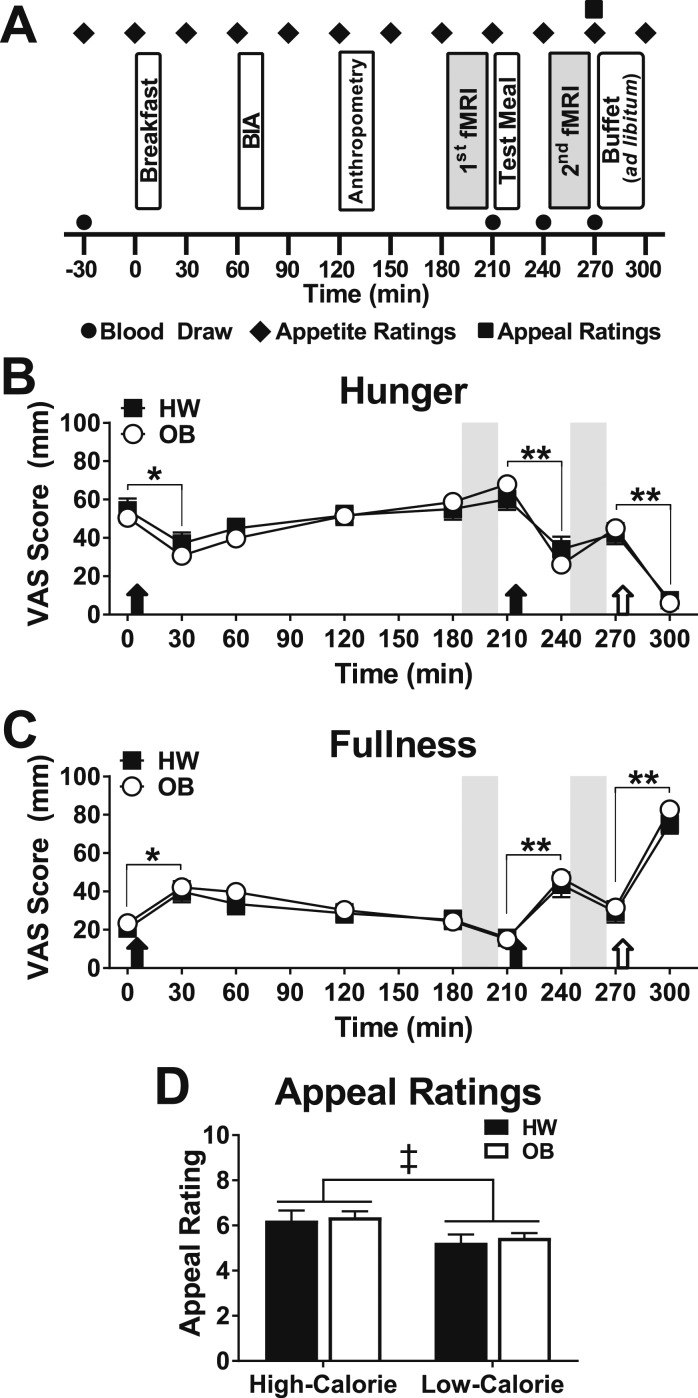

Figure 1.

Timing of study procedures and appetite and appeal ratings in children of HW and children with OB. (A) Participants arrived fasting and underwent four blood draws [fasting (t−30), prior to the test meal (t210), then 30 (t240) and 60 (t270) min after the meal]. The first MRI scan session occurred 3 h after the standardized breakfast and was immediately followed by a standardized test meal, consumed within 10 min. The second MRI scan session began 30 min after the start of the test meal. The breakfast and test meal were titrated to represent 10% and 33%, respectively, of each participant’s estimated daily caloric intake whereas the buffet meal was ad libitum. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) was used to measure body composition. Appetite ratings were performed serially using visual analog scales (VAS) for hunger and fullness, whereas appeal ratings were obtained once, immediately prior to the buffet meal. (B and C) Appetite ratings of hunger (B) and fullness (C) were not different between groups [hunger, χ2(1) = 0.06, P = 0.80; fullness, χ2(1) = 0.53, P = 0.47]. All meals (filled arrows mark standardized meals; open arrows indicate ad libitum buffet meal) significantly suppressed hunger and increased fullness. (D) Participants rated high-calorie images as more appealing [χ2(1) = 9.99, P < 0.01]. Data are means ± SEM. P values for appetite and appeal ratings were determined by linear mixed models (unadjusted). Gray bars indicate fMRI sessions. n = 22 children of a HW, 54 children with OB (n = 2 missing for appeal ratings in the OB group). *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001, premeal vs postmeal appetite ratings for both groups; ‡P < 0.01, vs low-calorie images.

The first fMRI occurred 3 hours after breakfast, followed by a premeal blood draw, then a standardized test meal of macaroni and cheese titrated to meet 33% of estimated daily caloric needs (10% protein, 50% fat, 40% carbohydrate). With few exceptions, participants consumed the entire test meal within 10 minutes (one participant of HW and five patients with OB consumed <90% of the provided meal). Where indicated, analyses were adjusted for percentage of their estimated daily caloric needs consumed at the test meal. Postmeal blood draws occurred 30 and 60 minutes after the start of the test meal. The second fMRI followed the test meal. Then participants were presented with an ad libitum buffet meal and had 30 minutes to select and consume food. Children were not informed that their food consumption was monitored until a subsequent debriefing. The buffet meal was child-friendly, varied in nutritional properties (e.g., pizza, fruits, cookies), and exceeded participants’ estimated daily calorie requirements (∼5000 kcal). Uneaten food was weighed back to determine the macronutrient percentages and kilocalories consumed (ProNutra; VioCare, Princeton, NJ).

Visual analog scale ratings of hunger and fullness assessed subjective appetite every 30 to 60 minutes (26). Appeal ratings of a subset of photographs viewed during the fMRIs were completed on a 10-point Likert scale prior to the ad libitum buffet (Fig. 1) (18, 27).

Blood sampling and hormone assays

Plasma glucose and acylated ghrelin were measured by glucose oxidase and magnetic beads (EMD Millipore, St. Charles, MO), respectively. Plasma insulin, total peptide YY (PYY), and active glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 were measured by commercially available immunoassays (EMD Millipore). Intra-assay coefficients of variation were <8%, and interassay coefficients of variation were <10%. Unsuccessful IV placement (one participant of HW, five participants with OB) or individual blood draws (numbers for analyses are included in tables and graphs) resulted in missing data. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (28) and the percentage change from premeal to postmeal (average of samples taken before and after the second fMRI scan; Fig. 1A) in insulin, ghrelin, PYY, GLP-1, and glucose concentrations (5, 29) were calculated.

fMRI paradigm, acquisition, processing and analyses

Previously validated, child-friendly images were commercial-quality stock photographs and were grouped into three categories: high-calorie foods (e.g., desserts, pizza, burgers), low-calorie foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, lean meats), and nonfood objects (e.g., sports equipment, household items, clothing items). Each fMRI session (premeal and postmeal) included a distinct set of 13 blocks with 10 images each presented for 2.4 seconds. Nonfood blocks (n = 7) alternated with high-calorie (n = 3) and low-calorie (n = 3) food blocks and the order was counterbalanced across participants (half viewed high-calorie images as the first food block). All food images were ready to eat (i.e., fruits were depicted peeled), were displayed on a black background, were equal in size (600 × 400 dpi), and were matched for luminosity across blocks [F(51,480) = 0.26, P = 1.00). To encourage attention to the task, a memory test to distinguish images seen in the scanner from distractor images was conducted after each fMRI. Groups performed equivalently at all time points [premeal: OB, 84% ± 8.7% correct vs HW, 86% ± 7.6% correct; postmeal: OB, 81% ± 10% correct vs HW, 83% ± 11% correct; χ2(1) = 0.32, P value for the group-by-time interaction (PInt) = 0.57].

Scans were acquired with a 32-channel SENSE head coil on a 3-Tesla Philips Achieva MR System with software version 5.1.7 (Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) with dual Quasar gradients. In both sessions, a 133 volume, T2*-weighted single-shot echo-planar imaging time series [44 ascending axial slices, 2.75 × 2.75 × 3.00-mm voxels, repetition time (TR) of 2400 milliseconds, echo time (TE) of 30 milliseconds, flip angle of 76°, SENSE factor of 2] was acquired during passive picture viewing. For distortion correction and registration a B0 field map (TR of 10 milliseconds, minimum TE of 2.8 milliseconds, change in TE of 1.0 milliseconds, flip angle of 10°) and a three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo image with 176 sagittal slices (TR of 7.5 milliseconds, TE of 3.5 milliseconds, flip angle of 7°, SENSE factor of 2, matrix of 256 × 256, 1-mm isotropic voxels) were acquired.

Time series data were processed using FSL 6.0 [Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library], FreeSurfer 5.3, and Analysis of Functional NeuroImages. Preprocessing included dropping the first three volumes, simultaneous slice-timing and motion correction, removal of nonbrain tissue and spike artifacts, spatial smoothing (full width at half maximum of 5 mm), grand-mean intensity normalization, and high-pass temporal filtering (90 seconds). Using boundary-based registration in FSL, the registration matrix and warp field for each time series to the participant’s structural scan were calculated, then the structural scans were registered to the Montreal Neurologic Institute template space through an intermediate template [created by an iterative template-building method using brains from children 9 12 years of age from the Neurodevelopmental MRI Database (30, 31)] using diffeomorphic registration in the ANTs toolkit. Using fMRI Expert Analysis Tool (FEAT), a general linear model was applied to each participant’s first-level data and included nuisance covariates (e.g., motion). Condition effects were estimated from the average response across blocks for our contrasts of interest (high-calorie foods vs objects, low-calorie foods vs objects). fMRI data were excluded for scanner artifact (one participant with OB) and excessive motion (subjects with root mean square of absolute motion parameters >1.5 were excluded; two participants with OB before meal, eight participants with OB and one participant of HW after meal).

The primary outcome was average activation across six a priori regions in which activation by high-calorie food cues was previously shown to be a marker of satiety or predictor of food intake or food choice (18, 19). Regions of interest (ROIs) were the mOFC, SN/VTA, bilateral amygdala, DS, VS, and insula; each has a recognized role in appetitive processing. Except for the SN/VTA [which was anatomically defined as published recently (19)], anatomically defined masks were based on the Harvard-Oxford probabilistic atlas (32) using a minimum criterion of 25%. A functional criteria of a minimum level of responsivity to food cues was applied to exclude voxels with no measurable activation by food cues (high-calorie vs object or low-calorie vs object; before or after meal; whole brain; P < 0.05, uncorrected), resulting in a nominal reduction in the anatomic extent of the masks. The ROI masks were used to extract each subject’s mean ROI activation (measured as parameter estimates via fslstats) for contrasts of interest, then all ROIs were averaged into a single value representing the mean activation of all a priori ROIs. This value was the primary outcome used in statistical analyses of children of HW vs children with OB as described below; secondary analyses considered a priori ROIs separately.

Methods for voxel-wise exploratory analyses

Using a voxel-wise approach, an exploratory analyses of all voxels outside of the a priori ROIs were mapped with FEAT v6.0 (part of FSL) using a FLAME statistical model. Z statistic images (Gaussianized T/F) were corrected for multiple comparisons using a cluster-threshold correction with an individual voxel threshold at Z > 2.3 and a corrected cluster significance threshold of P = 0.05.

Statistical analyses

Data are reported as mean ± SEM and are unadjusted unless otherwise noted. Group comparisons for descriptive variables were done by χ2 test (categorical), linear regression (normally distributed), or by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (nonnormally distributed). Linear mixed models with the restricted maximum likelihood estimation tested group differences in outcomes and included fixed effects (e.g., time) and interaction terms. Formal post hoc stratified analyses were performed when a significant group-by-time interaction was present. Nonnormally distributed variables were transformed for regression analyses. Simple and multiple linear regression models tested associations and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for descriptive purposes. Apart from the exploratory analyses performed in FSL, all statistics were completed by STATA (v13.1) and GraphPad Prism (v6.05) using extracted values (parameter estimates) for fMRI measures.

Results

Participant characteristics

Groups were balanced for sex and age and did not differ significantly in race or ethnicity. Fasting plasma concentrations for participants with OB were lower for active ghrelin but higher for insulin and leptin compared with participants of HW; however, there were no differences in PYY or GLP-1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Children of HW (n = 22) | Children With OB (n = 54) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, % | 45 | 44 | 0.94a |

| Race | 0.09a | ||

| White, % | 91 | 67 | |

| Multiple, % | 5 | 20 | |

| Other, % | 5 | 13 | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino, % | 95 | 78 | 0.06b |

| Age, y | 10.4 (0.9) | 10.4 (0.8) | 0.95b |

| BMI parameters | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 16.9 (1.3) | 29.1 (6.3) | n/a |

| BMI, Z scorec | −0.1 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.3) | n/a |

| BMI, percentilec | 46 (18) | 98 (1.1) | n/a |

| BMI, % over the 95th percentilec,d | −26.2 (4.7) | 26.7 (26.0) | n/a |

| Body composition | |||

| Fat mass, kg | 7.6 (3.3) | 31.9 (13.0) | n/a |

| Fat mass, % | 21.5 (6.1) | 48.6 (6.6) | n/a |

| Lean mass, kg | 26.6 (3.0) | 32.2 (5.1) | n/a |

| Lean mass, % | 78.5 (6.1) | 51.4 (6.6) | n/a |

| Fasting plasma concentrations | |||

| Leptin, ng/mL | 3.22 (2.79–5.54) | 29.2 (22.7–37.5) | <0.0001e |

| PYY, pg/mL | 164 (136–194) | 167 (133–217) | 0.69e |

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | 52.8 (44.7–65.7) | 35.6 (24.3–51.6) | 0.002e |

| GLP-1, pM | 3.00 (1.43–4.64) | 2.45 (1.49–4.20) | 0.87e |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 94.5 (7.0) | 97.4 (5.6) | 0.09b |

| Insulin, uU/mL | 5.6 (3.85–5.95) | 14.4 (9.8–18.7) | 0.0001e |

| HOMA-IR | 1.25 (0.93–1.51) | 3.51 (2.46–4.63) | <0.0001e |

Data are means (SD) or medians (interquartile range) unless otherwise reported. Group comparisons are unadjusted and were done by the indicated method. Body composition was measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Children with OB had significantly higher BMI parameters and body fat mass compared with children of HW. For fasting plasma concentrations and HOMA-IR, n = 20 to 21 for children of HW and n = 43 to 46 for children with OB.

χ 2 Test (categorical).

Linear regression (normally distributed).

BMI parameters were calculated with least mean square values by sex and age.

BMI percentage over the 95th percentile was calculated as the percentage that the current BMI was over the estimated 95% BMI percentile (https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/percentile_data_files.htm).

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (nonnormal distribution).

Appetite, food appeal, and food intake

Overall subjective appetite ratings did not differ between groups (Fig. 1B and 1C). All meals significantly suppressed hunger and increased fullness in both groups similarly (Fig. 1B and 1C) except that participants with OB reported a greater reduction in hunger by visual analog scale from pretest to posttest meal (OB, −43 ± 4.1 mm vs HW, −29 ± 5.1 mm; P < 0.05). Participants rated images of high-calorie foods as more appealing than low-calorie foods (Fig. 1D) without group differences [χ2(1) = 0.02, PInt = 0.90].

Participants with OB consumed 44% more calories at the ad libitum buffet meal compared with participants of HW. Macronutrient choice did not differ (Table 2) nor did caloric intake based on estimated daily caloric needs (OB, 62% ± 2.9% vs HW, 58% ± 5.0%, P = 0.45). A trend was present when the total caloric intake was adjusted to measured lean body mass (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ad Libitum Caloric Intake at a Buffet Meal

| Children of HW (n = 22) | Children With OB (n = 54) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kilocalories consumed | |||

| Unadjusted | 802.7 (64.4) | 1156.1 (56.8) | 0.001 |

| Adjusted for lean mass | 917.4 (86.7) | 1109.4 (52.3) | 0.08 |

| Macronutrients consumed | |||

| Fat, % | 35.7 (2.3) | 36.2 (1.3) | 0.84 |

| Carbohydrate, % | 52.6 (2.6) | 51.9 (1.5) | 0.79 |

| Protein, % | 11.7 (0.7) | 12.0 (0.5) | 0.75 |

Data are means (SEM) and are unadjusted unless otherwise noted. Group comparisons were done by linear regression.

Average brain activation before and after a test meal within a priori regions

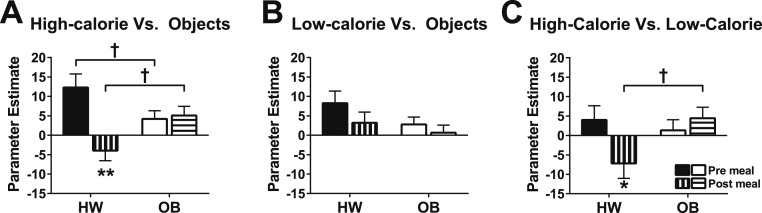

A single model tested whether premeal or postmeal activation in a priori regions by images of high-calorie foods (vs objects) differed between the OB and HW groups. There was no main effect of group [χ2(1) = 0.03, P = 0.86], but there was a main effect of time [premeal vs postmeal χ2(1) = 7.60, P < 0.01] and, importantly, the presence of a group by time (premeal vs postmeal) interaction [χ2(1) = 9.41, PInt < 0.01; Fig. 2A] indicated that premeal and postmeal responses differed between groups, requiring stratified analyses. Using fully corrected post hoc methods, group comparisons revealed that activation by high-calorie food images (vs objects) was significantly reduced from premeal to postmeal in the HW group (Z = −3.5, P < 0.0001), but not in the OB group (z = 0.28, P = 0.78). Premeal activation by high-calorie foods was significantly lower in the OB group compared with the HW group (Z = −2.1, P = 0.04), and postmeal activation was significantly higher in the OB group compared with the HW group (Z = 2.3, P = 0.02). In sensitivity analyses, the interaction remained significant when estimated daily caloric needs consumed at the test meal were added to the model [χ2(1) = 9.34, PInt < 0.01, adjusted]. In contrast, no group or time effects were present [χ2(1) = 2.56, P = 0.11 and χ2(1) = 2.26, P = 0.13, respectively] for the average response to low-calorie foods (vs objects) across a priori regions, nor was an interaction found [χ2(1) = 0.38, PInt = 0.54; Fig. 2B]. However, a group-by-time interaction was present for high-calorie (vs low-calorie) activation [χ2(1) = 4.63, PInt = 0.03; Fig. 2C].

Figure 2.

Effect of a meal on average activation across a priori appetite-processing regions. (A–C) Mean parameter estimates across a priori regions in children of HW and children with OB were measured before (filled/open bars) and after (striped bars) a standardized test meal for the contrasts of (A) high-calorie foods vs objects, (B) low-calorie foods vs objects, and (C) high-calorie vs low-calorie foods. Data are means ± SEM. P values were determined by linear mixed models. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0001, vs premeal within same group; †P < 0.05, HW group vs OB group.

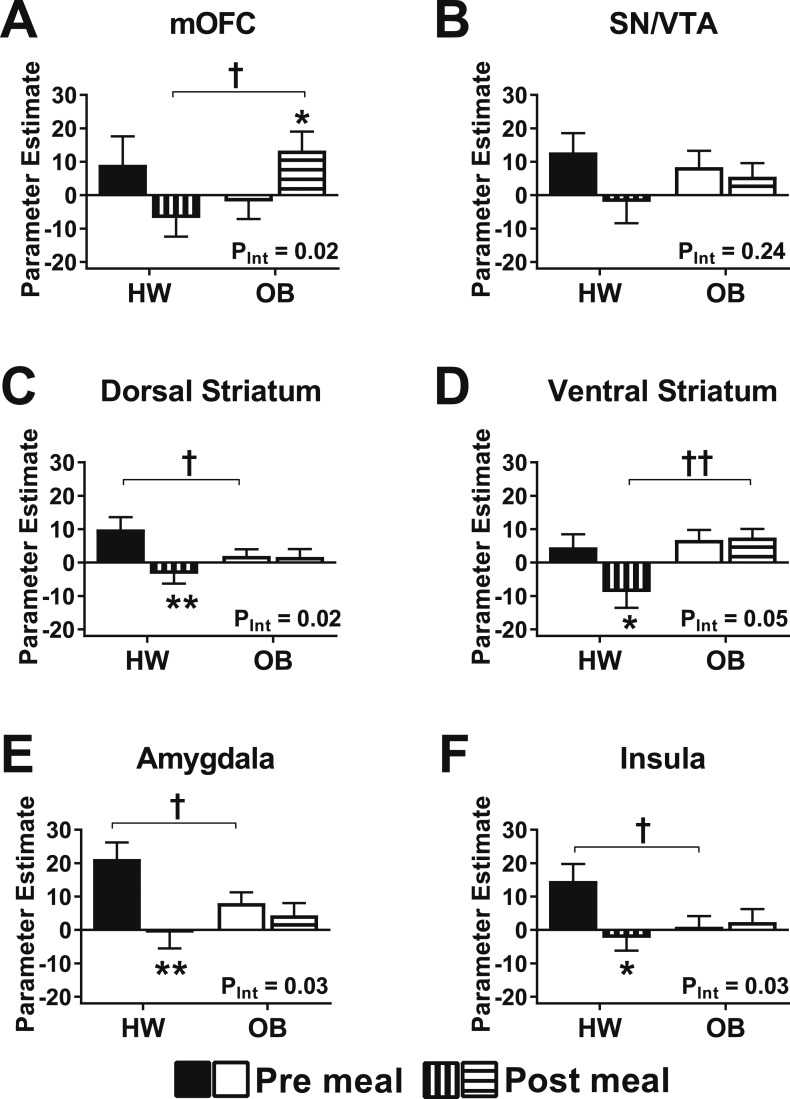

Secondary analyses of a priori regions confirmed there was no effect of brain side within any bilateral ROIs (linear mixed model including side as a factor, all main effects of side were P > 0.05). Therefore, secondary regional analyses considered the bilateral mean parameter estimates of each region (where appropriate) to examine group-by-time interactions. For activation by high-calorie foods (vs objects) all regions demonstrated a significant group-by-time interaction except the SN/VTA and VS (Fig. 3), suggesting a consistent pattern not driven by one particular regional response. Postmeal brain activation by high-calorie images was consistently suppressed bilaterally by the test meal in subjects of HW, but not in subjects with OB (Fig. 3). These data require cautious interpretation, however, because no interactions met Bonferroni-adjusted criteria for multiple comparisons within the individual regions (PInt < 0.008 for six models). For activation by low-calorie foods (vs objects) there was no significant group-by-time interaction in any of the a priori regions.

Figure 3.

Effect of a meal on regional activation. (A–F) Mean parameter estimates in regions considered separately in children of HW and children with OB were measured before (filled/open bars) and after (striped bars) a standardized test meal for high-calorie foods vs objects. (A) mOFC, (B) SN/VTA, (C) DS, (D) VS, (E) amygdala, (F) insula. Data are means ± SEM. P values were determined by linear mixed models. *P < 0.05 vs **P < 0.01, vs premeal within same group; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, HW group vs OB group.

Test meal-induced changes in hormones and glucose

Immediately prior to the test meal, plasma ghrelin concentrations were significantly lower whereas insulin levels were higher in the OB group compared with the HW group (Table 3). The HW group had a greater percentage reduction in plasma ghrelin from before to after the test meal and percentage rise in insulin than did the OB group. However, adjusting for caloric consumption at the test meal attenuated the effect for meal-induced reduction of plasma ghrelin (OB, −26.0% ± 3.7% vs HW, −37.7% ± 5.2%; P = 0.07 adjusted), but not insulin (P = 0.03, adjusted).

Table 3.

Plasma Hormone Concentrations

| Children of HW | Children With OB | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest meal plasma concentrations | |||

| PYY, pg/mL | 161 (129–192) | 137 (110–193) | 0.91a |

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | 77.2 (55.8–103) | 47.0(34.7–59.7) | 0.0003a |

| GLP-1, pM | 2.17 (0.33–3.83) | 2.25 (1.08–4.27) | 0.74a |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 88.9 (1.08) | 89.5 (0.99) | 0.68b |

| Insulin, uU/mL | 0.50 (0.50–5.15) | 17.1 (8.91–29.2) | 0.0001a |

| Percentage change by the test meal | |||

| PYY, % | 37.2 (4.30) | 43.0 (3.74) | 0.35b |

| Ghrelin, % | −38.9 (5.16) | −22.2 (4.87) | 0.04b |

| GLP-1, % | 170 (70.4–720) | 162 (52.8–525) | 0.91a |

| Glucose, % | 13.3 (2.34) | 18.5 (1.49) | 0.06b |

| Insulin, % | 2538 (317–3493) | 353 (114–750) | 0.02a |

Data are medians (interquartile range) or means (SEM). Group comparisons are unadjusted and were done by the indicated method. The percentage change was calculated as the percentage change from premeal (t210) to the mean of postprandial time points (t240, t270). n = 21 for children of HW and n = 43 to 46 for children with OB.

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (nonnormally distributed).

Linear regression (normally distributed).

Peripheral hormones and average activation in a priori regions

Prior to the test meal, there were no significant associations of average brain activation by high-calorie food cues (vs objects) in a priori appetite-processing regions to the square root of GLP-1 (P = 0.49), the log of ghrelin (P = 0.31), the log of PYY (P = 0.81), the square root of insulin (P = 0.73), or glucose concentrations (P = 0.73), nor were interactions present suggesting that relationships differed based on adiposity (PInt = 0.31 to 0.98). Furthermore, fasting concentrations of leptin and HOMA-IR scores (square root and log transformed, respectively) were also not associated with average brain activation to high-calorie images prior to test meal consumption (P = 0.40 and P = 0.91, respectively).

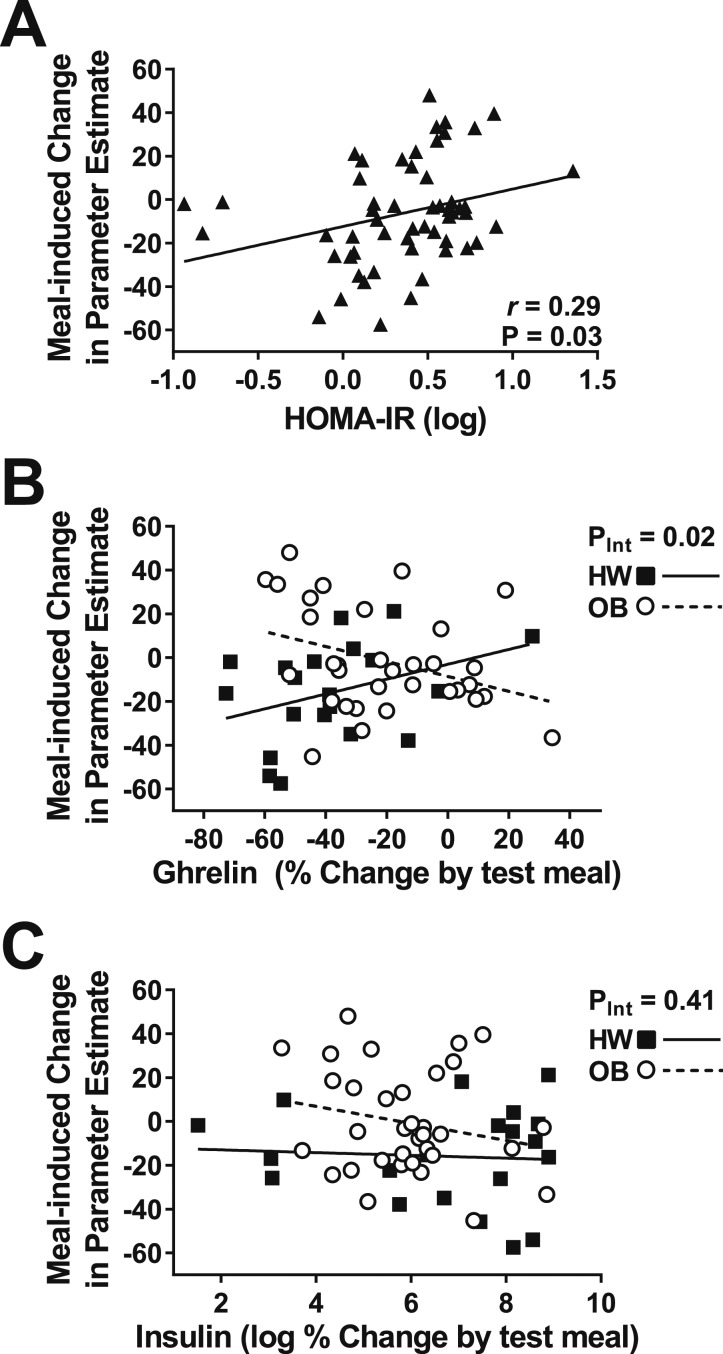

We then examined whether meal-induced changes in activation were associated with HOMA-IR scores, meal-induced excursions of appetite-regulating hormones, or glucose. Lower log HOMA-IR scores were related to greater meal-induced suppression of brain activation by high-calorie images (vs objects), indicating that children who were more insulin resistant showed less suppression of brain activation by a meal (Fig. 4A). However, this finding was not fully independent of adiposity and calories consumed (β = 4.70, P = 0.28; adjusted for body fat mass and estimated daily caloric need consumed at test meal). Percentage change in plasma GLP-1 (P = 0.68), ghrelin (P = 0.91), PYY (P = 0.34), the log of insulin (P = 0.16), and glucose (P = 0.95) concentrations by the test meal were all unrelated to the change in brain activation by high-calorie food cues. We next tested for interactions indicative of differences in the slopes between groups and found a significant interaction for ghrelin (Fig. 4B), such that in children of HW, greater reductions in plasma ghrelin concentration reflected greater suppression of brain activation by high-calorie food cues whereas postmeal activation by high-calorie food cues remained high in children with OB even when ghrelin was appropriately suppressed by the meal. The finding was independent of calories consumed (t = −2.85, PInt = 0.01, adjusted). No interactions were found for changes in GLP-1, PYY, glucose (PInt = 0.30 to 0.46), or the log of insulin (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Relationship between meal-induced change of average activation across satiety-processing regions and HOMA-IR and meal-induced changes of circulating ghrelin and insulin. (A) Across all participants, a higher HOMA-IR score was associated with less reduction in brain activation by high-calorie food cues. (B) Considering groups separately, there was a significant interaction between group and meal-induced change in circulating plasma ghrelin on the change in brain activation by a meal. (C) No interaction was present for the meal-induced change in plasma insulin and brain activation by high-calorie food cues. P values were determined by simple linear regression (A) and linear regression with an interaction term (B and C). A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for descriptive purposes.

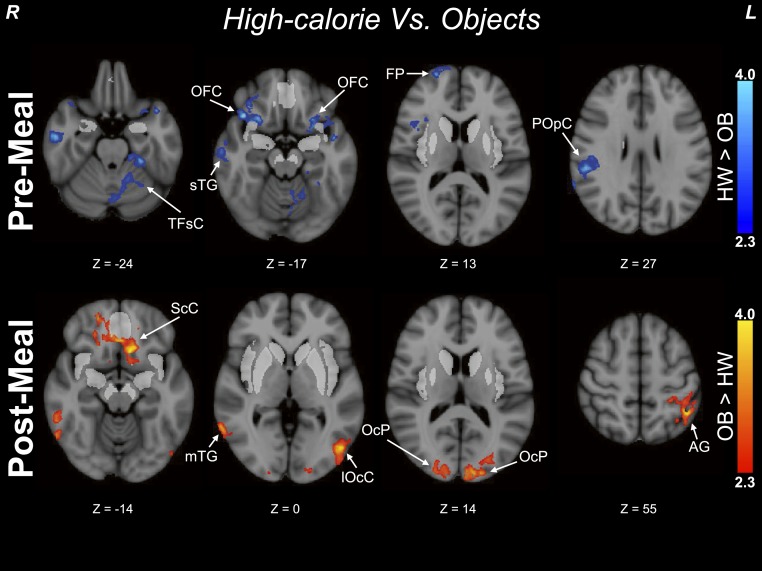

Exploratory voxelwise analyses outside of a priori regions

Prior to the meal, there were no areas outside of the a priori regions in which the OB group had greater activation to images of high-calorie foods (vs objects) compared with the HW group. However, the HW group exhibited greater activation (vs the OB group; Figure 5; Table 4) by high-calorie images in areas involved with decision-making [frontal pole (ventromedial prefrontal cortex), frontal orbital cortex adjacent to the insular ROI)], visual processing (fusiform gyrus), somatosensory processing (parietal operculum), and auditory processing (temporal gyrus). Conversely, after the test meal, there were no areas in which the HW group had greater activation compared with the OB group, but the OB group had greater activation in areas related to visual association (occipital pole and lateral occipital cortex, Brodmann areas 18 and 19) and language and memory processing (middle temporal gyrus, angular gyrus), as well as the limbic system (subcallosal cortex adjacent to the mOFC and ventral striatal ROIs). There were no significant clusters in which the HW group had greater activation compared with the OB group or vice versa (OB > HW) to images of low-calorie foods (vs objects) prior to the meal; however, after the meal the HW group (vs the OB group) had greater activation by low-calorie images in the supramarginal gyrus.

Figure 5.

Exploratory voxelwise analyses outside of a priori regions. The top panel shows clusters of greater activation in children of HW vs children with OB prior to the standardized meal. The bottom panel shows clusters with greater activation in children of HW vs children with OB after consumption of a standardized meal. Analyses excluded previously tested a priori ROIs, and all clusters depict activation by high-calorie foods vs objects. Z statistic maps were corrected for multiple comparisons and were thresholded at Z > 1.65 and a cluster significance threshold of P = 0.05 (FWE corrected). Premeal, n = 22 children of HW, n = 51 children with OB; postmeal, n = 21 children of HW, N = 46 children with OB. Color scales provide Z values of functional activation. Montreal Neurologic Institute coordinates are indicated. A priori ROIs are depicted in bright gray. Peak Montreal Neurologic Institute coordinates are provided in Table 4. AG, angular gyrus; FP, frontal pole; lOcC, lateral occipital cortex; mTG, middle temporal gyrus; OcP, occipital pole; POpC, parietal operculum cortex; ScC, subcallosal cortex; sTG, superior temporal gyrus; TFsC, temporal fusiform cortex.

Table 4.

Exploratory Voxelwise Cluster Analyses Outside of a Priori ROIs

| Primary Gray Matter Anatomic Area of Z Maximuma | Hemi-sphereb | MNI Coordinatesc |

Brodmann Aread | Cluster Size (No. Voxels) | Z Maxe | P | Other Anatomic Areas in Clusterf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| Premeal: high-calorie foods > objects | |||||||||

| HW > OB | |||||||||

| OFC | R | 41 | 22 | −17 | 47 | 4798 | 4.17 | 0.0003 | Temporal pole, insular cortex, frontal pole, inferior frontal gyrus, frontal operculum cortex |

| Adjacent to insular ROI | |||||||||

| Temporal fusiform cortex | L | −27 | −35 | −24 | 37 | 4758 | 3.52 | 0.0003 | Parahippocampal gyrus, temporal occipital fusiform cortex, cerebellum, brainstem (pons; middle cerebellar peduncle) |

| Parietal operculum cortex | R | 54 | −33 | 27 | 40 | 4365 | 3.60 | 0.0006 | Planum temporale, supramarginal gyrus, angular gyrus, postcentral gyrus |

| Frontal pole | R | 23 | 63 | 13 | 10 | 3185 | 3.50 | 0.006 | — |

| OFCg (bilateral to above) | L | −27 | 11 | −14 | n/a | 2463 | 3.79 | 0.03 | Insular cortex, temporal pole, planum polare |

| Adjacent to insular ROI | |||||||||

| Superior temporal gyrus | R | 56 | −5 | −13 | 22 | 2444 | 3.62 | 0.03 | Middle temporal gyrus, planum polare |

| OB > HW | |||||||||

| No significant clusters | |||||||||

| Premeal: low-calorie foods > objects | |||||||||

| HW > OB | |||||||||

| No significant clusters | |||||||||

| OB > HW No significant clusters | |||||||||

| Postmeal: high-calorie foods > objects | |||||||||

| HW > OB | |||||||||

| No significant clusters | |||||||||

| OB > HW | |||||||||

| Subcallosal cortex | L | −10 | 21 | −14 | 11 | 5124 | 3.85 | 0.0002 | Frontal orbital cortex, frontal pole (left and right), frontal medial cortex (left and right), frontal orbital cortex (right), subcallosal cortex (right) Adjacent to mOFC and ventral striatial ROIs |

| Occipital pole | L | −12 | −95 | 14 | 18 | 4489 | 3.43 | 0.0006 | Lateral occipital cortex, cuneal cortex |

| Angular gyrus | L | −44 | −51 | 55 | 40 | 4201 | 3.77 | 0.001 | Supramarginal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, lateral occipital cortex, superior parietal lobule |

| Lateral occipital cortex | L | −48 | −73 | 0 | 19 | 3783 | 3.69 | 0.002 | — |

| Occipital poleg (bilateral to above) | R | 16 | −99 | 9 | 18 | 2705 | 3.63 | 0.02 | Lateral occipital cortex, cuneal cortex |

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 64 | −54 | −1 | 37 | 2613 | 3.48 | 0.02 | Inferior temporal gyrus, lateral occipital cortex |

| Postmeal: low-calorie foods > objects | |||||||||

| HW > OB | |||||||||

| Supramarginal gyrus | R | 68 | −41 | 12 | 22 | 2182 | 3.34 | <0.05 | Middle temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, planum temporale |

| OB > HW | |||||||||

| No significant clusters | |||||||||

Exploratory analyses excluded previously tested regions of interest (VS, amygdala, DS, insula, VTA/SN, and mOFC). Clusters abutting these regions are indicated in italics. Analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons with a cluster-threshold correction with an individual voxel threshold at Z = 2.3 and a corrected cluster significant threshold of P = 0.05.

Harvard–Oxford Atlas identified regions of local maximum.

Hemisphere of local maximum (L, left; R, right).

Montreal Neurologic Institute coordinates of peak location.

Brodmann area of local maximum (when local maximum was near, but just outside of a Brodmann area, the closest adjacent area was listed).

Maximum Z score.

Other areas identified within the cluster (areas listed are ipsilateral to primary area unless otherwise indicated).

When the local maximum appeared in white matter, the closest gray matter structure within the cluster was listed.

Discussion

In the present study, children with OB showed minimal premeal to postmeal reduction in average activation by high-calorie food cues from before to after a meal across a set of key brain regions that participate in satiety processing (14, 18), including the DS, insula, amygdala, and dopaminergic reward regions (VS, SN/VTA, mOFC). In contrast, there was marked reduction in activation premeal to postmeal for children of HW. As such, the resultant average postmeal activation was significantly greater in children with OB. It is noteworthy that these activation differences between children with OB vs children of HW were not observed for low-calorie food cues. In contrast to previous studies in children (11, 12), there was no evidence for hyperactivation to food cues among children with OB vs children of HW before the meal and, in fact, children of HW demonstrated more activation premeal compared with children with OB in this sample. Although there were baseline differences between children with OB and children of HW in fasting leptin, insulin, and ghrelin concentrations, only insulin resistance (as assessed by HOMA-IR) in the presence of excess adiposity was associated with meal-induced changes in activation. Percentage changes in circulating levels of glucose and hormones from before to 60 minutes after eating were unrelated to either weight status or changes in brain activation. Moreover, the significant interaction that was present for ghrelin suggests that the lack of postmeal reduction among the OB group occurred despite their intact peripheral gut responses to nutrients. In summary, the findings demonstrate a possible neurobiological signature for behavioral findings of reduced satiety responsiveness and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children with OB wherein the hormonal response to food intake does not appropriately suppress neural activity in key appetite-processing brain regions, particularly in response to high-calorie food cues.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in children to investigate the relative roles of gastrointestinal hormones and neural activation in response to food intake. In fMRI studies, ghrelin has been shown to enhance response in brain regions associated with appetite and hedonic regulation (17, 33). In contrast, anorexigenic hormones have the opposite effect (15, 20). In the HW group, a greater percentage reduction in ghrelin concentration by a meal showed the expected pattern of a greater reduction in activation by high-calorie food cues. However, children in the OB group demonstrated persistent meal-induced brain activation by high-calorie food cues even when reductions in postprandial ghrelin were substantial. This finding implicates a defect in central responsiveness to reduced postmeal circulating ghrelin in the OB group, which also may have limited our ability to detect a relationship in the overall group between reductions in ghrelin concentrations and neural activation.

In contrast to gut hormone responses, we found that after a test meal, persistent activation of satiety-processing areas in response to viewing high-calorie food cues vs objects was associated with a greater degree of insulin resistance. These results highlight the impact of insulin signaling in the brain and the concept of co-occurrence of peripheral and central insulin resistance (34), and they furthermore support prior findings showing that food cue–induced neural responses are impacted by insulin sensitivity (35).

The findings suggest that the central response to a meal is altered in children with OB, but meal-related behavioral and hormone responses are similar to children of HW. Specifically, despite a subjectively satiating meal and a typical gut hormone response, postmeal reactivity to high-calorie food cues in reward- and appetite-regulating brain regions remained activated. As OB is increasingly conceived as a chronic condition in which the primary defect is a defense of elevated body weight (36), one interpretation is that the children are eating to maintain their current state of energy balance. An attenuated central response to a meal could be an adaptation that is acquired with increasing adiposity to stimulate the excess caloric consumption necessary to maintain diet-induced adiposity at the higher “set point,” as demonstrated in rodents (37). Hence, the primary defect is not overconsumption in these children, but the fact that brain responses do not promote a return to the previous, healthier level of adiposity. It is equally possible that our findings reflect genetic predispositions toward altered central satiety responses and weight gain (19, 38). Longitudinal data are required to discern whether this phenotype is acquired or inherited, and whether this phenotype would be reversible, once acquired. Finally, the interpretation of the findings as suggestive of a reduced central response to a meal in obese children is still consistent with models of incentive sensitization in that devaluation of high-calorie food images does not occur appropriately in the fed state [consistent with findings from studies of attentional bias in adults (39, 40)], and the enhanced responsiveness is thereby more readily detected after a meal.

Prior studies comparing subjects with OB to controls of HW found greater neural activation in response to visual food cues in brain regions implicated in reward, visual attention, cognition, and memory, findings frequently interpreted as neural hyperactivity that might pose a risk for caloric overconsumption (6, 7, 41–45). Our premeal findings contrast with these studies in that children of HW had consistently higher activation but they agree with others (46, 47). Previous studies using premeal to postmeal responses in children with OB relative to children of HW demonstrated hyperresponsivity to visual food cues in the prefrontal cortex premeal and mOFC postmeal (11, 12), whereas another study showed significantly less brain activation to food logos in the prefrontal cortex (48). At this time, we do not have a complete explanation for the relatively lower activation among the children with OB premeal. It may be that social, psychological, or attentional factors influencing activation by food cues could predominate in a premeal state over appetitive factors. This complex balance could vary in children of HW vs children with OB (especially those who are treatment-seeking) and requires further study.

Our data echo prior findings of higher postprandial activation in the OFC among 10 children with OB compared with 10 children of HW 11 to 17 years of age (11) and also of OB-prone adults (46). Although premeal activation was less robust in children with OB, their postmeal parameter estimates remained positive, suggesting sustained activation by high-calorie food cues (vs objects), whereas children of HW had postmeal parameter estimates that were negative (i.e., greater activation to objects compared with high-calorie images postmeal). This pattern was similar across all a priori regions tested in this study, including the bilateral amygdala and insula [areas of the “salience network” that process environmental stimuli, reward, and memory (18, 44)], as well as the VS, SN/VTA, and mOFC (43), which are critical regions of the dopaminergic reward system (49), and the DS. The DS is linked to permissive aspects of feeding (50) and to general motor inhibition (51, 52). Although the study was not powered to define which of these regions predominantly drove differences between lean and obese children, our secondary regional analyses did not detect evidence that individual anatomic regions or selected appetitive processing functions (e.g., reward, attention) explained the overall postmeal group differences among the children with OB. Moreover, our exploratory analysis among cortical and subcortical regions outside of the a priori ROIs revealed a similar pattern of activation differences between the two groups. The HW group had greater activation premeal in the frontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, and angular gyrus, regions involved in executive function and memory retrieval. In contrast, the OB group had significantly greater activation postmeal by high-calorie food images within primary visual cortex as well as visual processing and association regions. The latter is in accord with findings in adults showing that OB is associated with persistent visual attention to high-calorie food cues after eating (39). Taken together, such findings suggest that fundamental aspects of processing sensory information about food in the environment are altered once OB is present, even in childhood.

Strengths of the current study include its relatively large sample size for a neuroimaging study in young children, the variety of appetite and satiety measures obtained including direct measures of actual food intake, the high success rate of blood draws, and the minimal loss of scans due to excessive motion. However, the study has limitations. The subcortical dopaminergic reward system might not be fully developed in children. We minimized this issue by using a narrow age range. All obese children were treatment-seeking. Furthermore, caloric needs for the test meal were based on calculated estimates. We are aware that without using calorimetry, determinations of energy expenditure using different predictive equations can vary in accuracy (53). However, the current method achieved excellent concordance in perceived satiety prior to the fMRI sessions between the HW and OB groups. Furthermore, subjective ratings of hunger and fullness might be susceptible to reporting bias. We think that combined assessment of subjective ratings with neuroimaging and hormonal measures are further strengths of our study and, in fact, provide insight into the discrepancy between subjective reporting in children and brain response to images. We are aware that IQ has been shown to modestly (negatively) relate to child adiposity, but we did not assess IQ in our study and a recent meta-analysis suggested that IQ does not affect or explain the relationship between childhood OB/adiposity and executive function or reward systems (54). Additionally, the order of premeal/postmeal scans was not counterbalanced, and the two groups could have differential time effects, but counterbalancing premeal and postmeal scans would have required multiple scans and a greater participant burden for testing hormone responses. Finally, we are aware that this study requires careful interpretation of the results, in particular as the premeal average activation to high-calorie food cues across appetite-processing regions was lower in children with OB vs children of HW, and, although postmeal activation was higher in children with OB than in children of HW, their activation was still lower compared with children of HW at premeal. This finding contrasts with models implicating an increased overall reward value of food or enhanced sensitivity of the reward circuitry to conditioned stimuli linked to energy-dense food in individuals with OB (55–58). In this study, all children with OB were treatment-seeking, a potentially important factor that has unknown effects on the food cue responses and could contribute to weaker premeal activation by high-calorie food cues compared with children of HW. Decreased sensitivity to food cues has been reported in obese adults after weight reduction compared with lean controls (59), but data in treatment-seeking individuals are lacking. Given prior literature using food cues (14, 15, 17, 18), the reduction of activation among children of HW after eating is consistent with a reduced reward value of high-calorie food cues during satiety after a meal, but direct studies linking the increased postmeal activation in children with OB to increased motivation to eat or overeat are still needed.

In conclusion, our results suggest that an attenuated central response to food intake in appetite-processing brain regions is a feature of OB in children. The findings also suggest that, in children with OB, attention to and the reward value of high-calorie food cues in the environment may not be appropriately reduced after eating. Furthermore, peripheral satiety responses by gut hormones were largely intact in these young children, implicating a possible lack of central action in OB, particularly by insulin and/or ghrelin. Further studies should focus on the potentially important clinical implications of the findings, as the lack of a postmeal suppression of brain activation to high-calorie food cues may contribute to further weight gain in children with OB or resistance to weight loss (19).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Michael Schwartz and Kenneth Maravilla (University of Washington) for important contributions toward planning this study. Furthermore, we thank the participants and their parents for efforts to participate in the study, as well as Gabrielle D’Ambrosio (Seattle Children’s Research Institute) and Holly Callahan and Habiba Mohamed (University of Washington) for excellent support for performing the study visits.

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK098466 and R01DK104936 (to C.L.R.), R01DK089036 (E.A.S.), P30DK035816 (to the University of Washington Nutrition and Obesity Research Center), and by the University of Washington Institute of Translational Health Sciences (supported by National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grants UL1TR000423, KL2TR000421, and TL1TR000422).

Clinical Trial Information: ClinicalTrials.gov no. NCT02484976 (registered 30 June 2015).

Author Contributions: C.L.R., E.A., B.E.S., and E.A.S. designed the study; S.J.M., C.T.E., K.S., M.R.B.D.L., M.R., and S.K. acquired data; C.T.E. performed assays; S.J.M., T.J.G., and E.A.S. designed and/or performed fMRI analyses; S.J.M., C.T.E., C.L.R., and E.A.S. performed statistical analyses; E.A. and B.E.S. made important contributions to the manuscript; and C.L.R., S.J.M., C.T.E., and E.A.S. wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BMI

body mass index

- DS

dorsal striatum

- fMRI

functional MRI

- GLP

glucagon-like peptide

- HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- HW

healthy weight

- mOFC

medial OFC

- OB

obesity

- OFC

orbitofrontal cortex

- PInt

P value for the group-by-time interaction

- PYY

peptide YY

- ROI

region of interest

- SN

substantia nigra

- TE

echo time

- TR

repetition time

- VS

ventral striatum

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

References

- 1. Lansigan RK, Emond JA, Gilbert-Diamond D. Understanding eating in the absence of hunger among young children: a systematic review of existing studies. Appetite. 2015;85:36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carnell S, Wardle J. Appetite and adiposity in children: evidence for a behavioral susceptibility theory of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(1):22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Temple JL, Legierski CM, Giacomelli AM, Salvy SJ, Epstein LH. Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1121–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roth CL, Reinehr T. Roles of gastrointestinal and adipose tissue peptides in childhood obesity and changes after weight loss due to lifestyle intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(2):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roth CL, Doyle RP. Just a gut feeling: central nervous effects of peripheral gastrointestinal hormones. Endocr Dev. 2017;32:100–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rothemund Y, Preuschhof C, Bohner G, Bauknecht HC, Klingebiel R, Flor H, Klapp BF. Differential activation of the dorsal striatum by high-calorie visual food stimuli in obese individuals. Neuroimage. 2007;37(2):410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stoeckel LE, Weller RE, Cook EW III, Twieg DB, Knowlton RC, Cox JE. Widespread reward-system activation in obese women in response to pictures of high-calorie foods. Neuroimage. 2008;41(2):636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berridge KC. From prediction error to incentive salience: mesolimbic computation of reward motivation. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(7):1124–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Veldhuizen MG, Small DM. Relation of reward from food intake and anticipated food intake to obesity: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(4):924–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Epstein LH, Leddy JJ, Temple JL, Faith MS. Food reinforcement and eating: a multilevel analysis. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(5):884–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bruce AS, Holsen LM, Chambers RJ, Martin LE, Brooks WM, Zarcone JR, Butler MG, Savage CR. Obese children show hyperactivation to food pictures in brain networks linked to motivation, reward and cognitive control. Int J Obes. 2010;34(10):1494–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davids S, Lauffer H, Thoms K, Jagdhuhn M, Hirschfeld H, Domin M, Hamm A, Lotze M. Increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation in obese children during observation of food stimuli. Int J Obes. 2010;34(1):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burger KS, Stice E. Variability in reward responsivity and obesity: evidence from brain imaging studies. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(3):182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldstone AP, Prechtl de Hernandez CG, Beaver JD, Muhammed K, Croese C, Bell G, Durighel G, Hughes E, Waldman AD, Frost G, Bell JD. Fasting biases brain reward systems towards high-calorie foods. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30(8):1625–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Silva A, Salem V, Long CJ, Makwana A, Newbould RD, Rabiner EA, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Matthews PM, Beaver JD, Dhillo WS. The gut hormones PYY3–36 and GLP-17–36 amide reduce food intake and modulate brain activity in appetite centers in humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Batterham RL, ffytche DH, Rosenthal JM, Zelaya FO, Barker GJ, Withers DJ, Williams SC. PYY modulation of cortical and hypothalamic brain areas predicts feeding behaviour in humans. Nature. 2007;450(7166):106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malik S, McGlone F, Bedrossian D, Dagher A. Ghrelin modulates brain activity in areas that control appetitive behavior. Cell Metab. 2008;7(5):400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehta S, Melhorn SJ, Smeraglio A, Tyagi V, Grabowski T, Schwartz MW, Schur EA. Regional brain response to visual food cues is a marker of satiety that predicts food choice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(5):989–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Melhorn SJ, Askren MK, Chung WK, Kratz M, Bosch TA, Tyagi V, Webb MF, De Leon MRB, Grabowski TJ, Leibel RL, Schur EA. FTO genotype impacts food intake and corticolimbic activation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(2):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farooqi IS, Bullmore E, Keogh J, Gillard J, O’Rahilly S, Fletcher PC. Leptin regulates striatal regions and human eating behavior. Science. 2007;317(5843):1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Page KA, Seo D, Belfort-DeAguiar R, Lacadie C, Dzuira J, Naik S, Amarnath S, Constable RT, Sherwin RS, Sinha R. Circulating glucose levels modulate neural control of desire for high-calorie foods in humans. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4161–4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barlow SE; Expert Committee . Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(2):241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schaefer F, Georgi M, Zieger A, Schärer K. Usefulness of bioelectric impedance and skinfold measurements in predicting fat-free mass derived from total body potassium in children. Pediatr Res. 1994;35(5):617–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cleary J, Daniells S, Okely AD, Batterham M, Nicholls J. Predictive validity of four bioelectrical impedance equations in determining percent fat mass in overweight and obese children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(1):136–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shields BJ, Palermo TM, Powers JD, Grewe SD, Smith GA. Predictors of a child’s ability to use a visual analogue scale. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(4):281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schur EA, Kleinhans NM, Goldberg J, Buchwald DS, Polivy J, Del Parigi A, Maravilla KR. Acquired differences in brain responses among monozygotic twins discordant for restrained eating. Physiol Behav. 2012;105(2):560–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mittelman SD, Klier K, Braun S, Azen C, Geffner ME, Buchanan TA. Obese adolescents show impaired meal responses of the appetite-regulating hormones ghrelin and PYY. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(5):918–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Evans AC; Brain Development Cooperative Group . The NIH MRI study of normal brain development. Neuroimage. 2006;30(1):184–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanchez CE, Richards JE, Almli CR. Age-specific MRI templates for pediatric neuroimaging. Dev Neuropsychol. 2012;37(5):379–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldstone AP, Prechtl CG, Scholtz S, Miras AD, Chhina N, Durighel G, Deliran SS, Beckmann C, Ghatei MA, Ashby DR, Waldman AD, Gaylinn BD, Thorner MO, Frost GS, Bloom SR, Bell JD. Ghrelin mimics fasting to enhance human hedonic, orbitofrontal cortex, and hippocampal responses to food. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1319–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anthony K, Reed LJ, Dunn JT, Bingham E, Hopkins D, Marsden PK, Amiel SA. Attenuation of insulin-evoked responses in brain networks controlling appetite and reward in insulin resistance: the cerebral basis for impaired control of food intake in metabolic syndrome? Diabetes. 2006;55(11):2986–2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Lacadie C, Small DM, Sherwin RS, Potenza MN. Neural correlates of stress- and food cue-induced food craving in obesity: association with insulin levels. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, Drewnowski A, Ravussin E, Redman LM, Leibel R. Obesity pathogenesis: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38(4):267–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Ravussin Y, LeDuc CA, Watanabe K, Mueller BR, Skowronski A, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Effects of chronic leptin infusion on subsequent body weight and composition in mice: can body weight set point be reset? Mol Metab. 2014;3(4):432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schur E, Carnell S. What twin studies tell us about brain responses to food cues. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(4):371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Castellanos EH, Charboneau E, Dietrich MS, Park S, Bradley BP, Mogg K, Cowan RL. Obese adults have visual attention bias for food cue images: evidence for altered reward system function. Int J Obes. 2009;33(9):1063–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nijs IM, Muris P, Euser AS, Franken IH. Differences in attention to food and food intake between overweight/obese and normal-weight females under conditions of hunger and satiety. Appetite. 2010;54(2):243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin LE, Holsen LM, Chambers RJ, Bruce AS, Brooks WM, Zarcone JR, Butler MG, Savage CR. Neural mechanisms associated with food motivation in obese and healthy weight adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(2):254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stice E, Yokum S, Bohon C, Marti N, Smolen A. Reward circuitry responsivity to food predicts future increases in body mass: moderating effects of DRD2 and DRD4. Neuroimage. 2010;50(4):1618–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murdaugh DL, Cox JE, Cook EW III, Weller RE. fMRI reactivity to high-calorie food pictures predicts short- and long-term outcome in a weight-loss program. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2709–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nummenmaa L, Hirvonen J, Hannukainen JC, Immonen H, Lindroos MM, Salminen P, Nuutila P. Dorsal striatum and its limbic connectivity mediate abnormal anticipatory reward processing in obesity. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van der Laan LN, de Ridder DT, Viergever MA, Smeets PA. The first taste is always with the eyes: a meta-analysis on the neural correlates of processing visual food cues. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cornier MA, McFadden KL, Thomas EA, Bechtell JL, Eichman LS, Bessesen DH, Tregellas JR. Differences in the neuronal response to food in obesity-resistant as compared to obesity-prone individuals. Physiol Behav. 2013;110-111:122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Puzziferri N, Zigman JM, Thomas BP, Mihalakos P, Gallagher R, Lutter M, Carmody T, Lu H, Tamminga CA. Brain imaging demonstrates a reduced neural impact of eating in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(4):829–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bruce AS, Lepping RJ, Bruce JM, Cherry JB, Martin LE, Davis AM, Brooks WM, Savage CR. Brain responses to food logos in obese and healthy weight children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(4):759–764.e2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49. Berthoud HR. The vagus nerve, food intake and obesity. Regul Pept. 2008;149(1–3):15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palmiter RD. Dopamine signaling in the dorsal striatum is essential for motivated behaviors: lessons from dopamine-deficient mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zandbelt BB, Vink M. On the role of the striatum in response inhibition. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ghahremani DG, Lee B, Robertson CL, Tabibnia G, Morgan AT, De Shetler N, Brown AK, Monterosso JR, Aron AR, Mandelkern MA, Poldrack RA, London ED. Striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptors mediate response inhibition and related activity in frontostriatal neural circuitry in humans. J Neurosci. 2012;32(21):7316–7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Acar-Tek N, Ağagündüz D, Çelik B, Bozbulut R. Estimation of resting energy expenditure: validation of previous and new predictive equations in obese children and adolescents. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(6):470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pearce AL, Leonhardt CA, Vaidya CJ. Executive and reward-related function in pediatric obesity: a meta-analysis. Child Obes. 2018;14(5):265–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Baler RD. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake: implications for obesity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rolls ET. Taste, olfactory and food texture reward processing in the brain and obesity. Int J Obes. 2011;35(4):550–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Orr PT, Stice E, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Neural correlates of food addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):808–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4360–4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cornier MA, Salzberg AK, Endly DC, Bessesen DH, Rojas DC, Tregellas JR. The effects of overfeeding on the neuronal response to visual food cues in thin and reduced-obese individuals. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]