Abstract

Spiritual care is recognised as an essential element of the care of patients with serious illness such as cancer. Spiritual distress can result in poorer health outcomes including quality of life. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and other organisations recommend addressing spiritual needs in the clinical setting. This paper reviews the literature findings and proposes recommendations for interprofessional spiritual care.

Keywords: spiritual care, interprofessional, cancer patients

Introduction

Scientific advances have caused a dramatic increase in the lifespan of patients with cancer over the last 30 years. Attention to the whole person arises from the recognition that patients with cancer experience psychosocial and spiritual suffering, as well as physical; suffering is ‘experienced by persons, not merely by bodies’ and ‘has its source in challenges that threaten the intactness of the person.’1 The concept of total pain was expressed by Cicely Saunders as ‘the suffering that encompasses all of a person's physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical struggles.’2 While increased attention in oncology has been given to psychological and social aspects, spiritual care is often neglected. This review will analyse the literature to understand better the importance of spirituality and spirituality-based interventions in cancer care, how spiritual care can be implemented in trajectory of care of patients with cancer and provide recommendations for the integration of spiritual care in oncology.

Consensus-based recommendations

Attention to patient spirituality is the topic of several consensus-based recommendations from both national and international organisations. These recommendations arose from a desire to reach consensus on how to integrate spirituality into healthcare models for all patients.

Puchalski et al published the deliberations of two consensus conferences on the integration of spirituality in systems of care.3 4 These conferences were held in 2012 (‘Creating More Compassionate Systems of Care’) and in 2013 (‘On Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: The Transformational Role of Compassion, Love and Forgiveness in Health Care’) and were built on the work of a 2009 Consensus Conference, ‘Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care’, whose deliberations had already been published.3 The 2009 conference described recommendations in these areas: spiritual care models, assessment and treatment, and interdisciplinary collaboration. These latter consensus conferences proposed clinical standards for spiritually centred healthcare systems. They proposed six working groups in research, clinical care, education, policy/advocacy, communication and community involvement. The final deliberation provided an operative model to integrate spiritual care in clinical care systems.

A joint statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine5 defined spiritual and cultural care as one of the nine components of high-quality palliative care in oncology practice. Osman et al described the importance of attending to spiritual issues of patients and families in the development of ASCO guidelines for integrating palliative care into general oncology care.6 In 2018, ASCO guidelines for palliative care include spiritual care as an essential element of care with patients with cancer.6

The European Association for Palliative Care created a taskforce to address this matter and produced guidelines on spiritual care in 2014.7 Early in 2006, the European Network for Health Care Chaplaincy issued a statement, signed by 38 European associations, on the importance of spiritual care within palliative care as a result of their consultation on this topic. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence included spiritual care as a component of care for an adult patient at the end of his/her life.8

This paper presents a literature review of spiritual care within oncology and proposes recommendations for integrating interprofessional spiritual care into oncology. The framework is as follows:

To define key terms, including spirituality, spiritual well-being and distress.

This report will include a systematic review of the available evidence on spirituality in cancer.

Approaches for clinical integration of spiritual issues will be discussed.

Recommendations for integrating interprofessional spiritual care into oncology care will be proposed.

Definitions of spirituality, spiritual well-being and spiritual distress

Spirituality and religion

Within palliative care, consensus conferences in the USA and Europe3 4 8 have defined spirituality as a broader construct, inclusive of religious and non-religious forms. Nursing literature defines spirituality as ‘the most human of experiences that seeks to transcend self and find meaning and purpose through connection with others, nature, and/or a Supreme Being, which may or may not involve religious structures or traditions.’9

In the field of psychology, Pargament defines spirituality as the search for the sacred.10 Also, many spirituality definitions are based on the search for ultimate meaning, purpose and connectedness to self, others and the significant or sacred in their lives,3 or as one’s relationship with the transcendent, expressed through one’s attitudes, habits and practices.11 A global consensus-derived definition states, ‘Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.’3

Globalisation is a challenge to the spiritual management of patients with cancer. The values and the beliefs of the patient may be quite different or even at odds with those of the healthcare practitioners. Spiritual care involves understanding and acceptance of this diversity.12

Spiritual well-being and spiritual distress

Spirituality is a domain of health, together with the physical, social and emotional domains. Spiritual well-being is the ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature and/or a power greater than oneself that can be strengthened.13

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) identifies spiritual distress to include ‘common, normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fear, to problems that become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, despair, and existential spiritual crises.’14

Literature review

A literature search was performed in MEDLINE via PubMed and Health Source, with the following keywords: cancer, oncology, spirituality, spiritual, care and health. Restrictions were set as to the publication year, and studies published between 2000 and July 2017 were taken into consideration. Studies were included only if they were published in English. These research parameters resulted in 1396 hits. After reading the titles and abstracts, 136 articles were initially selected, but after further content review, 106 papers were considered fitting for the purposes of the review. We also considered published guidelines from any national or international oncology or palliative care society.

The following categories of investigation structured this review: (1) spiritual care models; (2) spirituality, spiritual well-being, and spiritual distress and outcomes of patients with cancer; (3) clinician spiritual care; (4) patient desires for spiritual care; (5) spiritual screening, history taking and assessment; (6) treatment of spiritual distress; (7) professional ethical aspects; and (8) training.

Spiritual care models

Based on the aforementioned data, it is clear that spirituality plays a fundamental role in care of patients with cancer and may offer a positive impact on outcomes of care. Spiritual care should be attentively structured according to patient needs.

At an International Consensus Conference in 2009, palliative healthcare professionals from 27 countries reached agreement on a model of implementation of spiritual care that integrates dignity-centred and compassionate care into the biopsychosocial framework that is the basis of palliative care. Fundamental to this model is the recognition of the role of all clinicians to attend to the whole person—body, mind and spirit.

This model has two main components:

The clinician–patient relationship. Spiritual care builds on the relationship between the clinician and patient and acknowledges the patient’s serious illness. Inherent to this aspect of spiritual care is the practice of compassionate presence, which can be characterised as being fully present with another as a witness to his or her own experience. Healing may occur by finding meaning, hope or a sense of coherence in the midst of illness.3

The clinical assessment and treatment of spiritual distress. The NCCN described spiritual care in two domains. One, assessment and treatment of spiritual distress, has chaplains serving as spiritual care specialists and clinicians providing generalist spiritual care. Thus, all clinicians should address patients’ spirituality, identify and treat spiritual distress and support spiritual resources of strength. In-depth spiritual counselling is referred to the trained chaplain.14

FICA (Faith and belief, Importance, Community, Address in care) is a validated standard tool, serving as a guide for clinicians to incorporate open-ended questions regarding spirituality into the standard comprehensive history.15 FICA was validated for patients with cancer at the City of Hope Cancer Center; this study demonstrated that this tool is able to assess several dimensions of spirituality based on correlation with the spirituality indicators in the City of Hope-Quality of Life tool, specifically religion, spiritual activities, change in spirituality, positive life change, purpose and hopefulness. This study also supported the broad definition of spirituality.16

Frick et al 17 assessed the feasibility and usefulness of a semistructured interview for the assessment of spiritual or faith needs and preferences (SPIR) of patients with cancer. Their study showed the tool was useful for learning about their patient’s faith concerns.

Epstein-Peterson et al assessed the types of spiritual care offered to patients with advanced cancer in four Boston (Massachusetts, USA) cancer centres and interviewed the receiving patients about the impact of these spiritual care interventions. Spiritual care included spiritual history taking, making referrals to spiritual assistants’ support systems and praying with the patient.18

Kao et al described the experience of interdisciplinary rounds, where chaplains and consultation/liaison psychiatrists discussed oncology patients together at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.19 Sinclair and Chochinov proposed supporting the integral role of spiritual care professionals as a standard part of oncology interdisciplinary teams.20

Spirituality, spiritual well-being, and spiritual distress and cancer outcomes

Spirituality has been demonstrated to impact health outcomes of patients with cancer across the trajectory of disease. Table 1 describes and summarises studies and/or trials that were designed to demonstrate the impact of spirituality and/or spiritual well-being on health outcomes. We considered both interventional and non-interventional (observational) studies. Spirituality and spiritual well-being have been studied in patients with all stages of cancer21–27 and also in more specific settings, such as in patients with advanced-stage cancer28–31 and early-stage cancer,32 and patients on active treatment32–36 and in palliative care.30 31 37 Some studies only considered patients affected by a particular type of cancer, mainly breast,34 35 38–44 prostate,32 45–48 colorectal,48–50 lung36 51 and brain52 tumours. Some other studies considered social or socioeconomical aspects, focusing on low-income or indigent patients45–47 or patients from a particular ethnicity, such as African-American35 40 53 or Latino ethnicity.44 Special attention has been paid to cancer survivors39 44 48 50 54–56 and their caregivers or family members.39 40 49 52 57 58

Table 1.

Summary of studies on the impact of religion, spirituality and spiritual care on outcomes of patients with cancer

| First author, year | Patients (n) | Observational versus interventional | Quality of the study | Setting | Disease | Outcome |

| Garssen, 201521 | 10 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients | All cancers, but brain tumours | Coping with cancer diagnosis |

| Ripamonti, 201622 | 276 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients with cancer | – | Hope |

| Visser, 201023 | 40 studies | – | Literature review | Patient with cancer | – | Well-being |

| Jim, 201524 | Over 32 000 | – | Meta-analysis | Patients with cancer | – | Overall physical health |

| Sherman, 201525 | 78 independent samples (14 277 patients) | – | Meta-analysis | Patient with cancer | – | Social health |

| Salsman, 201526 | 148 studies | – | Meta-analysis | Patient with cancer | – | Mental health |

| Bai, 201527 | 36 studies | – | Literature review | Patients with cancer | – | Quality of life |

| Trevino, 201428 | 603 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients with advanced cancer (life expectancy <6 months) | – | Lower risk for suicidal intention |

| Balboni, 201129 | 339 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Advanced cancer | – | Greater spiritual care provision is associated with better quality of life (QOL), less aggressive end-of-life medical care (and costs). |

| López-Sierra, 201530 | 26 studies | – | Literature review | End-of-life and palliative care patients with cancer | – | Meaning Well-being |

| Kandasamy, 201131 | 50 | Observational | Prospective, cross sectional | Palliative care patient with cancer | – | Spiritual well-being negatively associated with fatigue, symptom distress, memory disturbance, loss of appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth and sadness. |

| Mollica, 201632 | 1114 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patient with localised disease | Prostate cancer | Decision-making difficulty and decision-making satisfaction |

| Lewis, 201433 | 200 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patient on active treatment | – | Fatigue |

| Barlow, 201334 | 12 | Interventional | Prospective, descriptive | Women on long-term hormonal therapy | Breast | Therapy adherence |

| Morgan, 200635 | 11 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | African-American women on cancer treatment | Breast | Quality of life |

| Piderman, 201536 | 1917 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients on active treatment | Lung | Motivational levels for physical activity |

| Vallurupalli, 201237 | 69 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients receiving palliative radiotherapy | – | Quality of life Coping |

| Neugut, 201638 | 445 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Adjuvant therapy | Breast | Chemotherapy discontinuation |

| Gesselman, 201739 | 498 couples | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivors and partners | Breast | Post-traumatic growth |

| Sterba, 201440 | 45 (23 patients+22 caregivers) | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivors and caregivers (African-American) | Breast | Spirituality provides global guidance, guides illness management efforts and facilitates recovery. |

| Jafari, 201341 | 68 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Iranian patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy | Breast | Quality of life, spiritual well-being |

| Jafari, 201342 | 68 (34 in the interventional arm) | Interventional | Prospective, descriptive | Patients undergoing radiotherapy | Breast | Quality of life, spiritual well-being |

| Tate, 201143 | 13 studies | – | Literature review | Patient with cancer | Breast | Coping |

| Wildes, 200944 | 117 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Latina cancer survivors | Breast | Health-related quality of life |

| Bergman, 201145 | 35 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Low-income patients with cancer | Prostate | Greater palliative treatment use |

| Zavala, 200946 | 86 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Low-income patients | Metastatic prostate cancer | Health-related quality of life |

| Krupski, 200647 | 222 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Indigent patient with cancer | Prostate | Health-related quality of life |

| Leach, 201748 | 1188 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivors | Breast Prostate Colon and rectum |

Preparedness to transition to post-treatment care |

| Asiedu, 201449 | 73 (21 patients+52 family members) | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patient with cancer and family members | Colorectal cancer | Coping with cancer diagnosis |

| Salsman, 201150 | 258+568 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivor | Colorectal cancer | Health-related quality of life |

| Meraviglia, 200651 | 60 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patient with cancer | Lung | Quality of life |

| Piderman, 201536 | 11 | Interventional | Analytical, cohort study | Patients with brain tumours and their supportive person | Brain | Quality of life Spiritual coping and spiritual well-being |

| Holt, 200953 | 23 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | African-American with cancer | – | Coping |

| Miller, 201754 | 193 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Adult survivors of childhood cancer | Any kind of cancer developed in childhood | Healthcare self-efficacy |

| Canada, 201655 | 8405 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivors | – | Functional quality of life |

| Gonzalez, 201456 | 102 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Survivors | – | Depression |

| Borjalilu, 201657 | 42 | Interventional | Randomised controlled trial | Mothers of children with cancer | – | Less anxiety |

| Frost, 201258 | 96 (70 patients+26 spouses) | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patients and their spouses | Ovarian | Quality of life |

| des Ordons, 201859 | 37 articles | – | Literature review | Patients with cancer and advanced disease | – | Effects of spiritual distress |

| Jim, 201560 | 101 unique samples | – | Meta-analysis | Patient with cancer | – | Overall physical health, physical well-being, functional well-being, physical symptoms |

| Seyedrasooly, 201461 | 206 | Observational | Prospective, descriptive | Patient with cancer | – | Perception of prognosis |

Spirituality and impact on quality of life, coping, lower symptom burden and adherence to treatment

Patients with cancer can also experience significant spiritual distress. In a recent systematic review study, the point prevalence of spiritual distress within inpatient setting ranges from 16% to 63%, and 96% of patients had experienced spiritual pain, a pain ‘deep in the being that is not physical’, at some point in their lives.59 Several studies have shown the spiritual distress is associated with worse physical, social and emotional distress.60 61

Clinician spiritual care provision

Spirituality has been assessed in patients with advanced-stage cancer, and studies have paid attention to health professionals’ provision of spiritual care to patients. Phelps et al 62 evaluated 75 patients with advanced cancer and 339 cancer physicians and nurses through semistructured interviews and web-based survey, respectively. Most patients (77.9%), physicians (71.6%) and nurses (85.1%) believed that routine spiritual care would be of positive impact on patients, but physicians had more negative perceptions of spiritual care than patients (p<0.001) and nurses (p=0.008). Balboni et al 63 published further data highlighting that most patients had never received any form of spiritual care from their oncology nurses or physicians (87% and 94%, respectively) and found out that the strongest predictor of spiritual care provision by nurses and physicians was their receiving training in spiritual care provision, underscoring the need for training in spiritual care provision.

Patient desires for spiritual care

Studies have shown that most patients would like their clinicians to address their spiritual concerns.64

Spiritual screening, history taking and assessment

Spiritual s creening is important for providing initial information about a patient in spiritual emergencies (ie, spiritual distress which needs attention by a trained chaplain), or for referral to an in-depth spiritual assessment when indicated. The patient can be asked, ‘How important is religion and/or spirituality in your coping?’ If patient responds affirmatively, then a follow-up question could be, ‘How well are those resources working for you at this time?’

If the patient describes difficulty with coping and/or that spiritual or religious resources are not working well for him or her, referral to a trained chaplain is advised.

If there are no difficulties identified by screening, the spiritual history should be obtained by a clinician involved in the admission process.

Spiritual history—FICA (Box 1) is a spiritual history tool that assesses for spiritual strength or distress with spirituality defined broadly. It helps clinicians to understand the patient’s spiritual needs and resources. The tool is intended to invite patients to share about their Faith,Belief, or sources of Meaning ( F ); the Importance ( I ) of spirituality on an individual’s life and the influence that belief system or values have on the person’s healthcare decision-making; the individual’s spiritual Community ( C ); and interventions to Address (A) spiritual needs.15

Box 1. FICA spiritual history tool.

F—Faith and belief

‘Do you consider yourself spiritual or religious?’ or ‘Is spirituality something important to you’ or ‘Do you have spiritual beliefs that help you cope with stress/difficult times?’

If the patient responds, ‘No,’ the healthcare provider might ask, ‘What gives your life meaning?’ Sometimes patients respond with answers such as family, career or nature.

I–Importance

‘What importance does your spirituality have in your life?

Has your spirituality influenced how you take care of yourself, your health?

Does your spirituality influence you in your healthcare decision making? (eg, advance directives, treatment, etc)’

C—Community

‘Are you part of a spiritual community?

Communities such as churches, temples, and mosques, or a group of like-minded friends, family, or yoga, can serve as strong support systems for some patients.

Is this of support to you and how?

Is there a group of people you really love or who are important to you?’

A—Address in care

‘How would you like me, your healthcare provider, to address these issues in your healthcare?’

Referral to chaplains, clergy and other spiritual care providers.

The spiritual history is performed as part of the social or personal history of the patient and should be done routinely as part of the initial intake evaluation. The reasons for assessing for spiritual issues or distress at follow-up visits are:

A change in clinical status.

Follow-up on spiritual distress or issues addressed at prior visit.

Increased pain or distress.

Unclear aetiologies for patients’ presenting concerns to evaluate for all aetiologies including spiritual.

The checklist below includes all the parts of a social history including a spiritual history such as FICA.

Social and spiritual history checklist (George Washington University School of Medicine)

Living situation (alone or with others and type of home, eg, house, apartment, assisted living, shelter, etc).

Significant relationships.

Occupation.

Sexual activity.

Tobacco use.

Alcohol use.

Recreational drugs use.

Diet.

Exercise.

Hobbies, interests.

Spiritual history (FICA).

Spiritual assessment

Spiritual assessment is an in-depth, ongoing process of evaluating the spiritual needs and resources of patients. A professional chaplain listens to a patient’s story to understand the patient’s needs and resources. The 7×7 model for spiritual assessment was developed by a team of chaplains and nursing faculty.65 It employs a multidimensional view of spirituality, including spiritual beliefs, behaviour, emotions, relationships and practices.

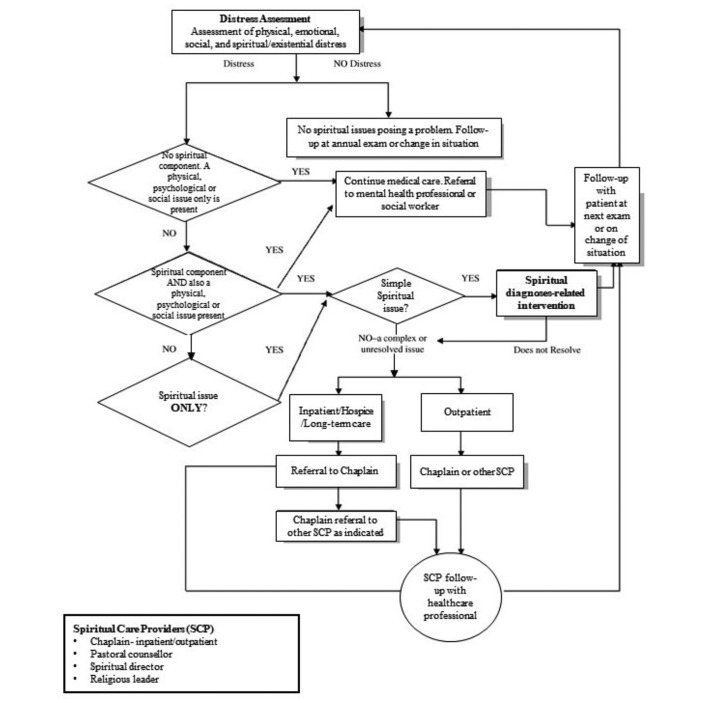

Table 2 presents a decision pathway in identifying or diagnosing the spiritual distress and providing appropriate interprofessional spiritual care interventions. This was developed based on the recommendations of the 2009 Consensus Conference, ‘Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care’.3

Table 2.

Examples of spiritual health interventions3

| Therapeutic communication techniques |

|

| Therapy |

|

| Self-care |

|

As seen in figure 1, physicians and other clinicians can use existing tools, such as those listed in this flow chart, to assess for physical, emotional, social and spiritual/existential distress. The patient may exhibit one or more of these areas of distress. It is important to identify the source of the distress. A patient who has physical pain, social isolation and spiritual distress needs pain management, social support and treatment of the spiritual distress.

Figure 1.

Spiritual diagnosis decision pathways3.

Treatment of spiritual distress

Spiritual distress includes existential distress, hopelessness, despair and anger at God. It can be a severe source of pain and distress for patients with cancer. In 2002, Breitbart66 conducted a literature review of interventions for spiritual suffering at the end of life for patients with cancer. At that time, very few resources existed. In 2005, Cunningham67 included spiritual aspects in a brief psychoeducational course demonstrating that addressing spiritual issues within the framework of group therapy might be beneficial.

In the generalist specialist model described above,3 all clinicians on the team assess for spiritual distress. The experts in spiritual care are the trained chaplains or spiritual care professionals. Healthcare providers may intervene by being attentive to what they observe as potential resources, for example, sacred texts, spiritual music, spiritual symbols in the room, or in what the patient is wearing. Healthcare providers should screen for spiritual struggle.68

Renz et al 69 explored patients’ spiritual experiences of transcendence and analysed how these experiences impacted patients. Siegel70 found that mindfulness and concentration helped a patient with debilitating pain.71

Chaplaincy interventions

Chaplains often play a ‘representative’ role with patients, that is, patients may experience them as representing God or the spiritual community.72 If the chaplain is attentive and caring, the patient’s negative experience of God or spiritual community may change in a more positive direction.

Clinicians should work in close partnership with chaplains and always consider referral. Trained chaplains or spiritual care professionals are the experts in spiritual care; clinicians are the generalists. Table 2 includes examples of spiritual interventions that can be used by the clinicians to help patients express their distress and offer additional support to patients.

Documenting spiritual assessment and plan in the patient medical chart

In the clinical setting, it is critical to identify the spiritual/existential distress, to treat it and to document that in the patient’s chart. A case example (table 3) to illustrate how clinical spiritual care can be integrated and documented in clinical care is as follows:

Table 3.

Joanne's assessment and plan (integrating spiritual issues with the psychosocial and physical)

| Joanne is a 68-year-old woman with end-stage metastatic breast cancer, severe pain managed on opioids, medication-associated nausea, constipation, occasional insomnia, and spiritual and existential distress | |

| Physical | Continue with current pain regimen, add 5-HT3 antagonists, add trazodone prn, and bowel regimen referral to ortho-oncologist for possible surgery to treat pain and improve mobility so patient can travel. |

| Emotional | Supportive counselling, presence |

| Social | Encourage family meeting to discuss prognosis, goals of care, encourage patient sharing if she would like. |

| Spiritual | Spiritual counselling with chaplain, team continues to be present, exploring sources of hope, life story, meaning. |

Joanne is a 68-year-old woman recently diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer with severe hip pain from a pathologic fracture. She has a life partner, James, and two adult children. She feels so sad that her life is cut short; she is angry with God—‘Why me?’ She does not share her deep despair with anyone, as she does not want to burden her family.

Using the FICA© spiritual history tool, physicians and nurses can address her spiritual issues.15

F: Methodist; church is important to her. Praying to God helps (‘Although now my prayer is about my anger with him’).

I: Very important in her life, has always helped her cope.

C: Strong Community at church; but she does not really want to burden them so she stays at home.

-

A: Likes to talk with the chaplain but is afraid to share her anger about God with her pastor for fear she will be judged. She does wonder about her life and whether something she did caused this.

Her review of systems, which is a standard part of the medical history, is:

Physical: Pain 8–10/10, managed on slow release oral morphine and hydromorphone, occasional nausea associated with hydromorphone, constipation, occasional insomnia.

Emotional: Sad, not depressed, not anxious, uncertain about surgery decision (her decision vs her family’s).

Social: Good support, but no one to talk to about deep issues.

Spiritual: Anger at God, fear of uncertainty, existential distress, despair.

Integration of spiritual care into oncology care: professional aspects

Compassionate presence and attentiveness

Integral to the 2009 model described above is the role of being present to the patient and family in the midst of their suffering. Spiritual care involves helping people navigate their encounter with suffering and loss.

The primary intervention in spiritual care is creating a connection with the patient that enables them to express their deepest concerns. The clinician, in practising deep, non-judgemental listening helps the patient give voice to their suffering.

Being present challenges the clinician to be open to the patient’s suffering story without feeling the need to fix or change that suffering. No one can take that deep suffering away but in the presence of a compassionate listener, the patient may feel less alone, less afraid and come to a sense of coherence, healing and hope.

Ethical aspects of spiritual care

In its palliative care resolution, WHO notes that it is the ‘ethical obligation of all health care professionals and all health care systems to address spiritual issues of patients.’73 The American College of Physicians cites that it is the ethical duty of all physicians to attend to all dimensions of suffering psychosocial and spiritual, as well as physical.74

Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) also supports this position.

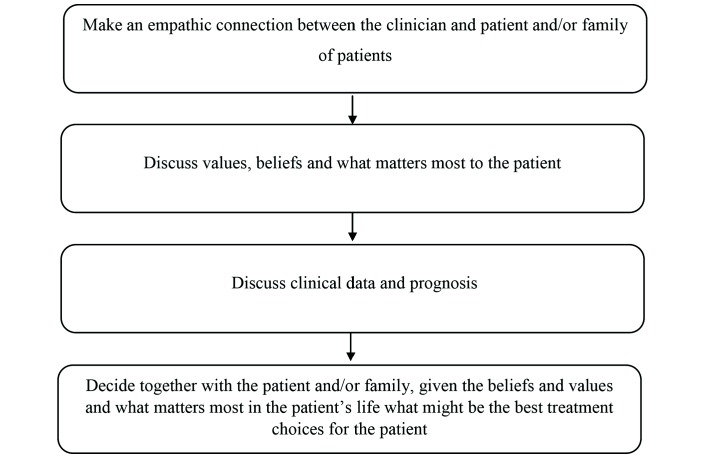

One way to help broaden the conversation about end-of-life choices beyond just the physical (eg, resuscitation) is to integrate the spiritual beliefs and values of patients in the goals of care discussions. It is important to open a space to a discussion about what matters most to the patient.

An example of how to integrate spiritual values and beliefs into a goals of care discussion is shown below in the flow chart (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Goals of Care Discussion Flowchart.

Training of clinicians

In a survey conducted among 69 oncology professionals,75 only 45% felt able to address their patients’ spiritual needs and identified the lack of education in this field as a barrier to such activity. A study conducted among medical students and faculty members at Harvard Medical School76 underlines that spirituality/religion is an important component of assistance to patients, and it has an important role in the medical student's socialisation: it helps them in the process of coping with suffering patients, as well as in establishing relationships with other members of the medical team.

Training should be offered to all health professionals involved in the care of patients with cancer in order to help them address patients’ spiritual needs. In a survey conducted among 87 programme directors of radiation oncology residency programmes in the USA,77 only 34% of the respondents reported that their residency programmes offered training activity on how to recognise and assess the role of spirituality, underscoring the importance of improving the education about patients’ spiritual concerns.

In a study published by Balboni et al and conducted among nurses and physicians assisting end-of-life patients,78 23% of the interviewed nurses and 45% of physicians believe that it is not their professional role to engage patients in spirituality. This is associated with a high feeling of unpreparedness (60% of nurses and 62% of physicians reported inadequate training), which further supports the importance of training in this field.

Recommendations for integration of spiritual care into oncology

Based on the above described empirical, theoretical and consensus-based recommendations for spiritual care, we suggest the following recommendations for how interprofessional spiritual care can be integrated into oncology practice. All authors participated in the development of items and conducted a final review, rating each item with greater than 90% endorsement of all items.

Spiritual care models

Spiritual care is integral to compassionate, person-centred care and is a standard for all oncology clinical care settings.

Spiritual care models are based on a biopsychosocial and spiritual model of care where spirituality is an equal domain to all other aspects of clinical care.

Spiritual care professionals such as trained chaplains should be part of the healthcare teams in clinical settings.

Spiritual screening, history and assessment

All clinicians who develop assessment and treatment plans should assess patients for spiritual or existential distress and for spiritual resources of strength and integrate that assessment into the assessment and treatment or care plan.

All clinicians who do screening of patient’s symptoms and concerns should integrate a spiritual screening.

All clinicians should recognise when and how to refer to and work with trained spiritual care professionals.

Treatment of spiritual distress

Clinicians are responsible for attending to the suffering of their patients.

Clinicians should treat patient spiritual distress, as with any other distress.

Patients’ spiritual resources of strength should be supported and integrated into the treatment or care plan.

Follow-up evaluations for spiritual distress should be done regularly, especially when there is a change in clinical status.

Professional ethical standards

All clinicians including chaplains have an ethical obligation to practise compassionate presence and attentive listening with their patients.

Clinicians should follow ethical standards for addressing spirituality with patients; discussions are patient centred and patient directed.

Training

All oncologists and clinicians practising in oncology settings should be trained in spiritual care. This training should be required as part of continuing education.

Clinicians should be trained in spiritual care, commensurate with their scope of practice in regard to the spiritual care model.

Healthcare professionals should be trained in doing a spiritual history or screening.

Healthcare professionals who are involved in diagnosis and treatment of clinical problems should be trained in the basics of spiritual distress diagnosis and treatment.

As part of cultural competency, all clinicians should have training in spiritual and religious values and beliefs that may influence clinical decision-making.

Training should also include opportunities for all members of the clinical teams to reflect on the role of their own spirituality and how it impacts their professional call and their own self-care.

Conclusion

Our literature review demonstrates that spirituality is an important component of health and general well-being of patients with cancer, and that spiritual distress has a negative impact on quality of life of patients with cancer. This makes the implementation of spirituality-based interventions essential in order to support the spiritual well-being of patients with cancer. Spirituality and spiritual well-being have been proven to have a positive effect on patients with cancer. Many national (eg, Great Britain) and international oncology palliative care as well as supportive care societies (ie, MASCC) have already created specific recommendations, guidelines and working groups on this matter, but it is important to widen oncology health professionals’ knowledge about spirituality and to implement spirituality as a cornerstone of oncological patients’ care. More research is needed to further our understanding of the role of spirituality in different cultural and clinical settings and to develop standardised models and tools for screening and assessment. Findings from this literature review also point to the need for more robust studies to assess the effectiveness of spiritual care interventions in improving patient, family and clinician's outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the preparation and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. Loss Grief Care 1998;8:129–42. 10.1300/J132v08n01_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ong C-K, Forbes D. Embracing cicely saunders's concept of total pain. BMJ 2005;331:576.5–7. 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.576-d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885–904. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, et al. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med 2014;17:642–56. 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bickel KE, McNiff K, Buss MK, et al. Defining high-quality palliative care in oncology practice: an American society of clinical Oncology/American Academy of hospice and palliative medicine guidance statement. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e828–38. 10.1200/JOP.2016.010686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S. Palliative care in the global setting: ASCO Resource-Stratified practice guideline. J Glob Oncol 2018;4:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. EAPC Task force on spiritual care in palliative care 2018;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE Quality standard [QS13]: end of life care for adults. 2011, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buck HG. Spirituality: concept analysis and model development. Holist Nurs Pract 2006;20:288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, practice. Guilford Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Markowitz AJ, McPhee SJ. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: "It's okay between me and God". JAMA 2006;296:2254 10.1001/jama.296.18.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balducci L, Innocenti M. Quality of life at the end of life : Beck L, Dying and death in oncology. Springer International Company, 2017: 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herdman TH. NANDA International nursing diagnoses: definitions & classification, 2009-2011. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2003;1:344–74. 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Puchalski C, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med 2000;3:129–37. 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:163–73. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frick E, Riedner C, Fegg MJ, et al. A clinical interview assessing cancer patients' spiritual needs and preferences. Eur J Cancer Care 2006;15:238–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Epstein-Peterson ZD, Sullivan AJ, Enzinger AC, et al. Examining forms of spiritual care provided in the advanced cancer setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:750–7. 10.1177/1049909114540318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kao LE, Lokko HN, Gallivan K, et al. A model of collaborative spiritual and psychiatric care of oncology patients. Psychosomatics 2017;58:614–23. 10.1016/j.psym.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sinclair S, Chochinov HM. The role of chaplains within oncology interdisciplinary teams. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:259–68. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283521ec9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garssen B, Uwland-Sikkema NF, Visser A. How spirituality helps cancer patients with the adjustment to their disease. J Relig Health 2015;54:1249–65. 10.1007/s10943-014-9864-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ripamonti CI, Miccinesi G, Pessi MA, et al. Is it possible to encourage hope in non-advanced cancer patients? we must try. Ann Oncol 2016;27:513–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdv614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 2010;19:565–72. 10.1002/pon.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jim HS, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2015;121:3760–8. 10.1002/cncr.29353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sherman AC, Merluzzi TV, Pustejovsky JE, et al. A meta-analytic review of religious or spiritual involvement and social health among cancer patients. Cancer 2015;121:3779–88. 10.1002/cncr.29352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Jim HS, et al. A meta-analytic approach to examining the correlation between religion/spirituality and mental health in cancer. Cancer 2015;121:3769–78. 10.1002/cncr.29350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bai M, Lazenby M. A systematic review of associations between spiritual well-being and quality of life at the scale and factor levels in studies among patients with cancer. J Palliat Med 2015;18:286–98. 10.1089/jpm.2014.0189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trevino KM, Balboni M, Zollfrank A, et al. Negative religious coping as a correlate of suicidal ideation in patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2014;23:936–45. 10.1002/pon.3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balboni T, Balboni M, Paulk ME, et al. Support of cancer patients' spiritual needs and associations with medical care costs at the end of life. Cancer 2011;117:5383–91. 10.1002/cncr.26221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. López-Sierra HE, Rodríguez-Sánchez J. The supportive roles of religion and spirituality in end-of-life and palliative care of patients with cancer in a culturally diverse context: a literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9:87–95. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kandasamy A, Chaturvedi SK, Desai G. Spirituality, distress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Indian J Cancer 2011;48:55–9. 10.4103/0019-509X.75828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mollica MA, Underwood W, Homish GG, et al. Spirituality is associated with better prostate cancer treatment decision making experiences. J Behav Med 2016;39:161–9. 10.1007/s10865-015-9662-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lewis S, Salins N, Rao MR, et al. Spiritual well-being and its influence on fatigue in patients undergoing active cancer directed treatment: a correlational study. J Cancer Res Ther 2014;10:676–80. 10.4103/0973-1482.138125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barlow F, Walker J, Lewith G. Effects of spiritual healing for women undergoing long-term hormone therapy for breast cancer: a qualitative investigation. J Altern Complement Med 2013;19:211–6. 10.1089/acm.2012.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morgan PD, Gaston-Johansson F, Mock V. Spiritual well-being, religious coping, and the quality of life of African American breast cancer treatment: a pilot study. Abnf J 2006;17:73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piderman KM, Sytsma TT, Frost MH, et al. Improving spiritual well-being in patients with lung cancers. J Pastoral Care Counsel 2015;69:156–62. 10.1177/1542305015602711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 2012;10:81–7. 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neugut AI, Hillyer GC, Kushi LH, et al. A prospective cohort study of early discontinuation of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: the breast cancer quality of care study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;158:127–38. 10.1007/s10549-016-3855-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gesselman AN, Bigatti SM, Garcia JR, et al. Spirituality, emotional distress, and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors and their partners: an actor-partner interdependence modeling approach. Psychooncology 2017;26:1691–9. 10.1002/pon.4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sterba KR, Burris JL, Heiney SP, et al. "We both just trusted and leaned on the Lord": a qualitative study of religiousness and spirituality among African American breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. Qual Life Res 2014;23:1909–20. 10.1007/s11136-014-0654-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, et al. Spiritual well-being and quality of life in Iranian women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:1219–25. 10.1007/s00520-012-1650-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jafari N, Zamani A, Farajzadegan Z, et al. The effect of spiritual therapy for improving the quality of life of women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Health Med 2013;18:56–69. 10.1080/13548506.2012.679738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tate JD. The role of spirituality in the breast cancer experiences of African American women. J Holist Nurs 2011;29:249–55. 10.1177/0898010111398655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wildes KA, Miller AR, de Majors SS, et al. The religiosity/spirituality of Latina breast cancer survivors and influence on health-related quality of life. Psychooncology 2009;18:831–40. 10.1002/pon.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bergman J, Fink A, Kwan L, et al. Spirituality and end-of-life care in disadvantaged men dying of prostate cancer. World J Urol 2011;29:43–9. 10.1007/s00345-010-0610-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, et al. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2009;18:753–61. 10.1002/pon.1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krupski TL, Kwan L, Fink A, et al. Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:121–31. 10.1002/pon.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leach CR, Troeschel AN, Wiatrek D, et al. Preparedness and cancer-related symptom management among cancer survivors in the first year post-treatment. Ann Behav Med 2017;51:587–98. 10.1007/s12160-017-9880-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Asiedu GB, Eustace RW, Eton DT, et al. Coping with colorectal cancer: a qualitative exploration with patients and their family members. Fam Pract 2014;31:598–606. 10.1093/fampra/cmu040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salsman JM, Yost KJ, West DW, et al. Spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer: a multi-site examination of the role of personal meaning. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:757–64. 10.1007/s00520-010-0871-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meraviglia M. Effects of spirituality in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006;33:E1–7. 10.1188/06.ONF.E1-E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Piderman KM, Radecki Breitkopf C, Jenkins SM, et al. The impact of a spiritual legacy intervention in patients with brain cancers and other neurologic illnesses and their support persons. Psychooncology 2017;26:346–53. 10.1002/pon.4031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holt CL, Caplan L, Schulz E, et al. Role of religion in cancer coping among African Americans: a qualitative examination. J Psychosoc Oncol 2009;27:248–73. 10.1080/07347330902776028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Miller KA, Wojcik KY, Ramirez CN, et al. Supporting long-term follow-up of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: correlates of healthcare self-efficacy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:358–63. 10.1002/pbc.26209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. Re-examining the contributions of faith, meaning, and peace to quality of life: a report from the American cancer society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Ann Behav Med 2016;50:79–86. 10.1007/s12160-015-9735-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gonzalez P, Castañeda SF, Dale J, et al. Spiritual well-being and depressive symptoms among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:2393–400. 10.1007/s00520-014-2207-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Borjalilu S, Shahidi S, Mazaheri MA, et al. Spiritual care training for mothers of children with cancer: effects on quality of care and mental health of caregivers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17:545–52. 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.2.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Frost MH, Johnson ME, Atherton PJ, et al. Spiritual well-being and quality of life of women with ovarian cancer and their spouses. J Support Oncol 2012;10:72–80. 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. des Ordons A, Sinuff T, Stelfox H, et al. Spiritual distress within inpatient settings—a scoping review of patient and family experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;156:122–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jim HSL, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2015;121:3760–8. 10.1002/cncr.29353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seyedrasooly A, Rahmani A, Zamanzadeh V, et al. Association between perception of prognosis and spiritual well-being among cancer patients. J Caring Sci 2014;3:47–55. 10.5681/jcs.2014.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Phelps AC, Lauderdale KE, Alcorn S, et al. Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. JCO 2012;30:2538–44. 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Amobi A, et al. Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:461–7. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. JCO 2007;25:555–60. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Farran CJ, Fitchett G, Quiring-Emblen JD, et al. Development of a model for spiritual assessment and intervention. J Relig Health 1989;28:185–94. 10.1007/BF00987750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Breitbart W. Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:272–80. 10.1007/s005200100289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cunningham AJ. Integrating spirituality into a group psychological therapy program for cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther 2005;4:178–86. 10.1177/1534735405275648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. King SD, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, et al. Determining best methods to screen for religious/spiritual distress. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:471–9. 10.1007/s00520-016-3425-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Renz M, Mao MS, Omlin A, et al. Spiritual experiences of transcendence in patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:178–88. 10.1177/1049909113512201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Siegel R. Psychophysiological disorders-embracing pain. Mindful Psychother 2005:173–96. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med 1985;8:163–90. 10.1007/BF00845519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Proserpio T, Piccinelli C, Clerici CA. Pastoral care in hospitals: a literature review. Tumori 2011;97:666–71. 10.1177/030089161109700521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. World Health Organization Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Snyder L, American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee . American college of physicians ethics manual: sixth edition. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:73–104. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201031-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kichenadasse G, Sweet L, Harrington A, et al. The current practice, preparedness and educational preparation of oncology professionals to provide spiritual care. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:e506–14. 10.1111/ajco.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Balboni MJ, Bandini J, Mitchell C, et al. Religion, spirituality, and the hidden curriculum: medical student and faculty reflections. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:507–15. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wei RL, Colbert LE, Jones J, et al. Palliative care and palliative radiation therapy education in radiation oncology: a survey of US radiation oncology program directors. Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:234–40. 10.1016/j.prro.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:400–10. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]