Abstract

Hydralazine is a commonly used anti-hypertensive medication. It can, however, contribute to the development of autoimmunity, in the form of drug-induced lupus and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated vasculitis. We report a 45-year-old patient with hypertension managed with hydralazine for four years who presented with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), requiring hemodialysis, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), requiring mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The patient’s autoantibody profile was consistent with a drug-induced autoimmune process and renal histology revealed focal necrotizing crescentic GN. She was treated with high-dose steroids, plasma exchange and rituximab. DAH resolved and her renal function improved, allowing discontinuation of hemodialysis. This case reveals that rituximab can be successfully used in the setting of hydralazine-induced vasculitis, including critically ill patients with severe DAH and acute kidney injury from RPGN.

Introduction

Hydralazine is a commonly used medication in the treatment of hypertension through induction of peripheral vasodilation through relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. Hydralazine is often utilized in patients with difficult to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure as it confers survival benefit in the latter group.1 It can, however, contribute to the development of autoimmunity, in the form of drug-induced lupus (DIL) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV). Hydralazine-induced DIL was described within the first several years of its introduction into clinical practice.2–4 DIL from hydralazine is characterized by positive anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and negative anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies.5 While the mechanism underlying DIL remains unclear, it has been previously suggested to arise from cytotoxic metabolites generated by myeloperoxidase (MPO) in immune cells.6

In contrast to DIL, AAV is a rare but serious adverse event from hydralazine that manifests primarily as glomerulonephritis with skin, joint and lung involvement.5 Hydralazine-induced AAV is associated with a positive ANA, anti-histone antibodies, ANCA, and high-titer anti-MPO antibodies.5,7,8 In addition, dsDNA antibodies have been reported in 26% of cases of hydralazine-induced AAV.5 The presence of multi-antigenicity in drug-induced vasculitis is not fully understood but may be due to drug-induced modifications of MPO granules and subsequent death of neutrophils, leading to exposure of multiple neutrophil auto-antigens from neutrophil extracellular traps.6,9 Awareness of this unusual drug toxicity is important to enable prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody to CD20 that depletes B cells and has been shown to be as efficacious as cyclophosphamide in the treatment of AAV.10 However since the initial trials did not enroll patients with respiratory failure or on dialysis, there has been some reluctance to embrace treatment with rituximab in settings of severe AAV.11 We present a case of life-threatening hydralazine-induced AAV that was successfully treated with rituximab in a patient that was treated with hydralazine for four years.

Case Report

A 45-year-old African-American female with Marfan’s syndrome and hypertension presented with three weeks of sharp chest pain, radiating to the back, left arm, and abdomen. She was on hydralazine, which had been increased over the last four years to 100 mg TID. Blood pressure was 210/107 with a heart rate of 47. Initial serum creatinine was 1.9 mg/dL (prior baseline 0.9), which corresponded to an estimated glomerular filtration rate (calculated with modification of diet in renal disease MDRD) of 35 mL/min/1.73 m2. Urinalysis showed specific gravity >1.030, protein 4+, blood 3+, leukocyte 1+. Automated urine microscopy revealed 20–50 white blood cells/ hpf and >50 red blood cells (RBCs)/hpf. She received prochlorperazine for nausea, which led to oropharyngeal angioedema complicated by cardiac arrest with successful resuscitation. A computerized tomography angiogram revealed a type B dissection spanning the entire descending aorta. She underwent percutaneous endovascular repair of the aorta with stent placement. Postoperatively, she developed anuria and serum creatinine rose to 4.3 mg/dL. Urine microscopy by the nephrology service revealed dysmorphic RBCs and no granular casts. She was started on emergent hemodialysis.

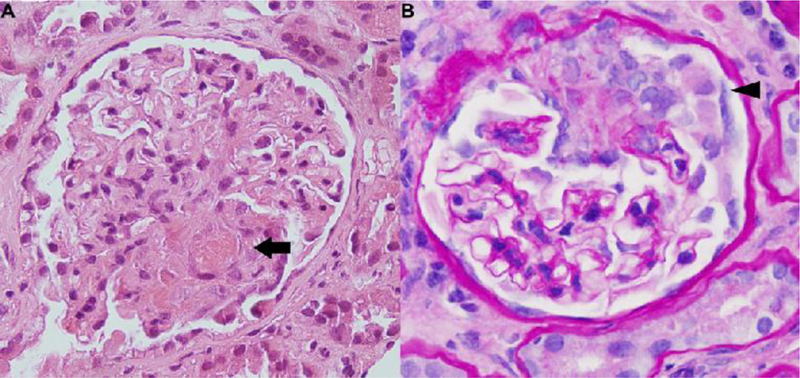

ANA and ANCA were positive at 1:320 (speckled pattern) and 1:1280 (p-ANCA) respectively. Further workup showed positive SSA, dsDNA (255 IU/mL), anti-histone (4.9U), and anti-MPO (98U) antibodies, and low C3 (71 mg/dL). Antibodies to proteinase three and glomerular basement membrane were negative. Renal biopsy was performed and pathology showed pauci-immune diffuse necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Renal biopsy in a patient with hydralazine-induced ANCA associated vasculitis. (a). Light microscopic examination with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain demonstrating segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis with obliteration of the capillary lumen by fibrinous material (arrow). (b) Periodic acid-Schiff stain demonstrating cellular crescents (arrowhead) (×40).

She was diagnosed with hydralazine-induced AAV (Table 1). She was treated with methylprednisolone 1 g intravenous (IV) for three days followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. On day 4 of oral prednisone, frank blood was noted in her endotracheal tube. She became hypoxemic despite maximum ventilatory support and was started on ECMO. Chest X-ray revealed bilateral lung opacities consistent with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). She underwent plasma exchange for six cycles followed by two doses of rituximab, 1 g IV, two weeks apart.

Table 1.

Distinct teaching points about hydralazine-induced ANCA associated vasculitis.

| Distinct teaching points |

|---|

| • Hydralazine-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis is associated with multiple autoantibodies: ANA, ANCA, anti-histone, high-titer anti-MPO antibodies and occasionally anti-dsDNA antibodies. |

| • Examination of urine sediment is essential to establishing the etiology of acute kidney injury, even in the setting of nephrotoxic agents or hypoperfusion. |

| • Rituximab can be an effective therapy for hydralazine-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis including life-threatening disease. |

| • ECMO can be an effective therapy for respiratory failure due to hydralazine-induced ANCAassociated vasculitis until the benefits of immunosuppression manifest. |

| • A clinical benefit of Rituximab may take up to 3 weeks to become apparent in ANCA-associated vasculitis. |

The patient remained ECMO-dependent for three weeks. After a five-week intensive care unit stays, she underwent a prolonged hospitallization and rehabilitation for sepsis, fungemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, wound infection, neuropathy, and myopathy. Her tracheostomy was decannulated after six weeks and dialysis was discontinued after eight weeks. Her renal function improved to near baseline after three months and serum creatinine stabilized at 1.1 mg/dL after six months.

Discussion

This case illustrates three salient points. One, this patient’s acute kidney injury (AKI) could have been attributed to multifactorial ischemic and toxic acute tubular necrosis (ATN) from radiographic IV contrast, transcutaneous aortic repair and hypotension from cardiac arrest. However, the presence of dysmorphic RBCs without granular casts on urine microscopy suggested glomerulonephritis and led to a renal biopsy with a diagnosis of hydralazine-induced AAV. This reiterates the importance of examining the urine sediment in patients with AKI.12 Kidney biopsy should be pursued in unexplained causes of AKI if urine sediment does not indicate ATN since treatment and prognosis vary significantly between different etiologies. In a patient with ATN, approximately 75% of patients who survive hospitalization may recover renal function in about 60 days.13 For patients with RPGN, the prognosis for renal recovery is guarded, especially with severe crescentic lesions on renal pathology. However, aggressive care with immunosuppression and plasma exchange can improve renal survival as demonstrated by the MEPEX trial.14 Two, hydralazine induced vasculitis, although uncommon, occurs. Hydralazine-associated autoimmunity is a dose-dependent phenomenon that often presents as DIL.15 A less common, but life-threatening manifestation is AAV.5 Unlike DIL, where discontinuation of hydralazine is often sufficient, hydralazine-induced AAV often requires aggressive immunosuppression.5 Given the lack of experience with rituximab in hydralazine-induced AAV, cyclophosphamide is still recommended as first-line therapy.16 This case demonstrates that rituximab can be an effective therapeutic option for hydralazine-induced AAV.

Third, some clinicians avoid the use of rituximab in critically-ill patients, for example, DAH requiring mechanical ventilation or serum Cr >4 mg/dL, based on the RAVE trial which excluded such patients.10 This patient would have been excluded from the RAVE trial due to both DAH and her serum Cr. Accordingly, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) guidelines from 2012 recommend using cyclophosphamide with steroids as the initial treatment for severe pauci-immune focal and segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis. KDIGO further recommends that rituximab with steroids can be used as an alternative initial treatment in patients without severe disease or in whom cyclophosphamide is contraindicated.17 In contrast, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative commentary on the KDIGO guidelines suggested that rituximab be considered as equivalent to cyclophosphamide in the initial treatment of severe disease.18 In support of this recommendation, several recent retrospective reports suggest that rituximab can be clinically efficacious in the setting of severe AAV.19,20 While these multicenter studies were small (only 14 and 37 cases), they demonstrated comparable rates of dialysis independence compared to the RAVE trial despite a more severe clinical presentation (MDRD eGFR of ≤20 mL/min/ 1.73 m2). Similarly, rituximab was effectively used in this patient in the setting of life-threatening hydralazine-induced AAV.

Conclusion

Hydralazine-induced autoimmunity can be severe and potentially life-threatening. To our knowledge, this is the first report of successful use of rituximab and ECMO to treat hydralazine-induced AAV and highlights their therapeutic efficacy in this condition. A high degree of vigilance is required to recognize and treat this serious complication of a commonly used medication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Franciosa JA, Taylor AL, Cohn JN, et al. African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-heFT): Rationale, design, and methodology. J Card Fail 2002;8:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posey EL, Stephenson SL Jr. Syndrome resembling disseminated lupus occurring during apresoline therapy. Miss Doct 1954;32:43–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhardt DJ, Waldron JM. Lupus erythematosus-like syndrome complicating hydralazine (apresoline) therapy. J Am Med Assoc 1954;155:1491–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shackman NH, Swiller AI, Morrison M. Syndrome simulating acute disseminated lupus erythematosus: Appearance after hydralazine (apresoline) therapy. J Am Med Assoc 1954; 155:1492–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokogawa N, Vivino FB. Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: Comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol 2009;19:338–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Khursigara G, Rubin RL. Transformation of lupus-inducing drugs to cytotoxic products by activated neutrophils. Science 1994;266:810–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, Niles JL. Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: Prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43: 405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cambridge G, Wallace H, Bernstein RM, Leaker B. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in idiopathic and drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panda R, Krieger T, Hopf L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain selected antigens of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Front Immunol 2017;8:439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:221–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronbichler A, Jayne DR. Con: Should all patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis be primarily treated with rituximab? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30:1075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perazella MA. The urine sediment as a biomarker of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66:748–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palevsky PM, O’Connor TZ, Chertow GM, et al. Intensity of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury: Perspective from within the acute renal failure trial network study. Crit Care 2009;13:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayne DR, Gaskin G, Rasmussen N, et al. Randomized trial of plasma exchange or highdosage methylprednisolone as adjunctive therapy for severe renal vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron HA, Ramsay LE. The lupus syndrome induced by hydralazine: A common complication with low dose treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:410–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bomback AS. An elderly man with fatigue, dyspnea, and kidney failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:836–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radhakrishnan J, Cattran DC. The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: Reading between the (guide)lines - Application to the individual patient. Kidney Int 2012;82: 840–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck L, Bomback AS, Choi MJ, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:403–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah S, Hruskova Z, Segelmark M, et al. Treatment of severe renal disease in ANCA positive and negative small vessel vasculitis with rituximab. Am J Nephrol 2015;41:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geetha D, Hruskova Z, Segelmark M, et al. Rituximab for treatment of severe renal disease in ANCA associated vasculitis. J Nephrol 2016;29:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]