Abstract

Purpose:

To develop an efficient distortion- and blurring-free multi-shot EPI technique for time-resolved multiple-contrast/quantitative imaging.

Methods:

EPI is a commonly used sequence but suffers from geometric distortions and blurring. Here, we introduce a new multi-shot EPI technique termed Echo Planar Time-resolved Imaging (EPTI), which has the ability to rapidly acquire distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast dataset. The EPTI approach performs encoding in ky-t space and utilizes a new highly-accelerated spatio-temporal CAIPI sampling trajectory to take advantage of signal correlation along these dimensions. Through this acquisition and a B0-informed parallel imaging reconstruction, hundreds of ‘time-resolved’ distortion- and blurring-free images at different TEs across the EPI readout window can be created at sub-millisecond temporal increments using a small number of EPTI-shots. Moreover, a method for self-estimation and correction of shot-to-shot B0-variations was developed. Simultaneous-multislice acquisition was also incorporated to further improve the acquisition efficiency.

Results:

We evaluated EPTI under varying simulated acceleration factors, B0-inhomogeneity and shot-to-shot B0-variations to demonstrate its ability to provide distortion- and blurring-free images at multiple TEs. Two variants of EPTI were demonstrated in vivo at 3T: i) A combined gradient- and spin-echo EPTI for quantitative mapping of T2, T2*, proton density, and susceptibility at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 whole-brain in 28 s (0.8 s/slice); and ii) a gradient-echo EPTI, for multi-echo and quantitative T2* fMRI at 2×2×3 mm3 whole-brain at a 3.3 s temporal resolution.

Conclusion:

EPTI is a new approach for multi-contrast/quantitative imaging that can provide fast acquisition of distortion- and blurring-free images at multiple TEs.

Keywords: EPI, distortion-free, multi-contrast, quantitative imaging, fMRI

Introduction

Echo planar imaging (EPI) is a rapid MRI acquisition technique capable of producing a 2D image in a single shot using a readout of a few tens of milliseconds (1,2). Due to its ability to achieve high temporal resolution, single-shot EPI (ss-EPI) has been widely used in diffusion imaging (3,4), functional imaging (5,6) and perfusion imaging (7,8). Multi-echo EPI can also be used to increase the functional sensitivity in functional MRI (fMRI) (9–11) or to measure T2* time courses in BOLD experiments (12,13). Combined spin and gradient multi-echo EPI sequence has also been developed to extract BOLD signal that is more confined to microvasculature (14), to achieve fast quantification of T2 and T2* (15) or to assess vascular properties in perfusion imaging (16–18).

Despite EPI’s advantage of rapid k-space coverage, the prolonged readout time for high-resolution image leads to several major problems: i) severe geometric distortion due to B0-inhomogeneity disrupting the encoding along the low bandwidth phase-encoding (PE) direction, ii) spatial filtering from the time dependent T2/T2* decay across the EPI readout, and iii) typically only a single-contrast image (with blurring and distortion effects) at the effective echo time is produced. If multi-TE acquisitions are applied, the minimum temporal spacing of the multiple TEs is set by the readout length, and this long readout duration makes it difficult to acquire multiple image echoes prior to significant T2/T2* decay. The first two problems significantly compromise the quality of high-resolution EPI images and limit its application to high-quality structural imaging. The third issue precludes multi-echo EPI from common use for quantitative multi-contrast imaging.

A number of distortion mitigation approaches have been developed for ss-EPI. The most popular post-processing approaches include field-map based corrections (19,20), and image-based corrections through a modified acquisition, such as reversed phase encoding (21). These methods correct for distortion by using estimated local pixel shifts in the image. Parallel imaging techniques (22,23) with in-plane acceleration have also been applied to ss-EPI to reduce distortion/blurring by decreasing the effective echo spacing. However, all of these methods have limited capability in correcting severe distortions in regions with strong susceptibility, leading to inaccurate anatomical information and loss of effective resolution. Multi-shot EPI techniques, including interleaved multi-shot EPI (ms-EPI) (4,24–27) and readout-segmented EPI (rs-EPI) (28,29), have been developed as alternatives to ss-EPI to further increase the sampling bandwidth in the PE direction and thus provide less distortion and blurring. These approaches, however, come a cost of longer scan time and a need for phase navigation/estimation for shot-to-shot B0-variations.

The distortion and blurring in EPI is caused by the nuisance signal evolution from susceptibility-induced phase accumulation and magnitude signal decay during prolonged echo train acquisition. If this nuisance signal evolution can be sampled, that is, with each echo time-point along the EPI train, all of the k-space lines composing an image can be acquired with the same susceptibility-induced phase and T2/T2* decay, then hundreds of distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast images can be created along the readout train at a temporal resolution in the order of a millisecond (equal to that of the echo-spacing). This can be achieved by Echo Planar Spectroscopic Imaging (EPSI) (30) in which different phase encodings are acquired in a multi-shot manner to obtain a full image at each echo time. Another multi-shot technique, Point-Spread Function mapping EPI (PSF-EPI) (31–33), which has currently been used to acquire distortion-free images, is also able to sample and extract such information. However, both PSF-EPI and EPSI require hundreds of acquisition shots to fully-sample the ky-t space, leading to an extremely long acquisition (e.g., ~200 times longer when compared to ss-EPI for brain imaging at 1 mm resolution). Even after parallel imaging acceleration (and reduced FOV approach in the case of PSF-EPI), more than 30 shots are still needed to achieve acceptable image quality (33–35), limiting their routine usage in high-resolution quantitative imaging or dynamic imaging. Significant improvements of EPSI have been made recently in fast spectroscopic imaging through exploring spatiospectral correlation and subspace model-based reconstruction (36–38).

In this study, we proposed a new imaging technique termed Echo Planar Time-resolved Imaging (EPTI), to achieve fast, distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast imaging with resolved signal evolution for EPI, first described in (39). With this approach, a novel spatio-temporal CAIPI sampling trajectory was developed to efficiently cover the desired ky-t space using several EPI readouts. The undersampled ky-t space is then recovered by exploring the signal correlation across the time and coil dimensions in a B0-informed parallel imaging reconstruction. To provide robustness to shot-to-shot B0-variations, a self-B0-variation estimation and correction method was also developed that takes advantage of the unique ky-t sampling of EPTI. To further accelerate the acquisition, simultaneous multislice (SMS) (40,41) was incorporated into EPTI, with an optimized ky-kz-t trajectory and reconstruction.

EPTI provides hundreds of distortion- and blurring-free T2&T2*-weighted images across the EPI readout, spaced at a time interval equal to an EPI echo-spacing (~1 ms), providing new signal evolution information. An acceleration factor up to 20–40× can be achieved along the PE direction, which allows high-resolution time-resolved brain imaging to be performed in less than 10 EPI-shots. Here, EPTI was demonstrated for two in vivo applications: i) fast quantitative mapping via Gradient-Echo and Spin-Echo EPTI (GESE-EPTI) to provide, simultaneously, maps of proton-density, T2, T2*, B0, tissue-phase, and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 resolution whole-brain in ~28 s, and ii) dynamic imaging via GE-EPTI to acquire whole-brain BOLD fMRI and T2* maps at 2×2×3 mm3 resolution with a temporal resolution of 3.3 s. The high efficiency of EPTI should also make it useful for a number of other applications where high-SNR undistorted images, multiple-contrast images or quantitative mapping are desired.

Theory

Phase Encoding-Time (ky-t) space

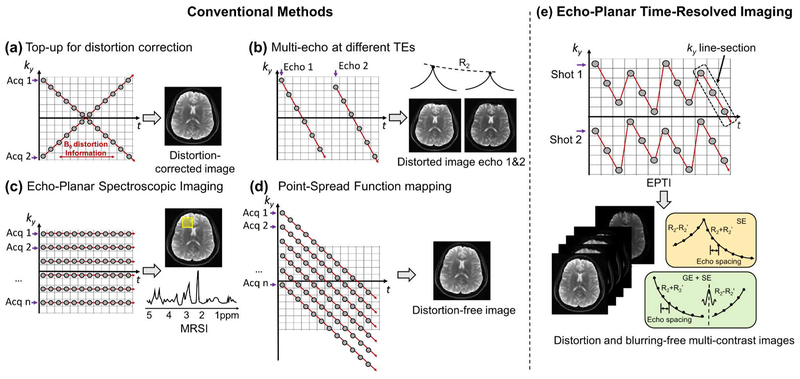

Figure 1 demonstrates the ky-t space sampling strategy of EPTI. In contrast to the usual signal space used in conventional k-t based methods (42,43), the time dimension here represents the echo time of each ky-line within an EPI readout train as in (30,44,45). Each gray circle in the figure represents an EPI readout line. For traditional ss-EPI, the sampling is expressed in the ky-t space as a diagonal line. Magnitude T2* decay and susceptibility-induced phase accumulates over time, leading to blurring and distortion. To correct for distortion, a pair of datasets with reversed phase-encoding can be acquired (21), shown as a pair of reversed diagonal lines in the ky-t space (Fig. 1a). To obtain multiple-contrast images, multi-echo EPI methods (9,15) can be used as shown in Figure 1b to help fill the ky-t space.

FIG. 1.

The ky-t trajectories of (a) ‘top-up’ distortion correction using reversed phase encoding acquisition, (b) multi-echo EPI combined with parallel imaging for multi-contrast imaging, (c) EPSI for spectroscopic imaging, (d) PSF-EPI for distortion- and blurring-free imaging, and (e) the proposed EPTI using an efficient spatial and temporal CAIPI sampling trajectory for distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast imaging, which is able to provide signal evolution information across EPI readout as shown in the bottom yellow and green boxes. Here, each dot represents an EPI readout line.

If the ky-t space is fully-sampled, a 2D k-space (kx-ky) without any phase accumulation or signal decay along the PE direction, can be obtained at each echo time point. Therefore, a series of images with different contrasts, spaced at a time interval of just an echo-spacing, can be generated without any distortions and blurring. Such fully-sampled ky-t data can be acquired via EPSI (30), using a multi-shot acquisition with step-wise increase of PE gradient after each shot (Fig. 1c). On the other hand, the PSF mapping approach (31–33) uses acquisitions with additional PE gradients before a conventional EPI readout, which creates diagonal lines in the ky-t space as shown in Figure 1d.

Echo Planar Time-resolved Imaging (EPTI)

The key assumption underlying the EPTI concept is that one can highly undersample the ky-t space, and recover the missing data points by exploiting the correlation across the time and PE directions. Here, we demonstrate that this is possible through an optimized ky-t sampling and a B0-informed reconstruction.

Optimized ky-t space sampling

Instead of acquiring one or all of the ky lines with each EPI shot, each EPTI shot covers a ky segment in ky-t space using a spatio-temporal CAIPI trajectory as shown in Figure 1e. This ky-t trajectory ensures that the neighboring diagonal ky line-sections within each EPTI-shot are acquired only a few milliseconds apart, and thus contain only a small amount of B0-inhomogeneity induced phase accumulation and T2* decay that can be well approximated by parallel imaging and B0-informed reconstruction (46).

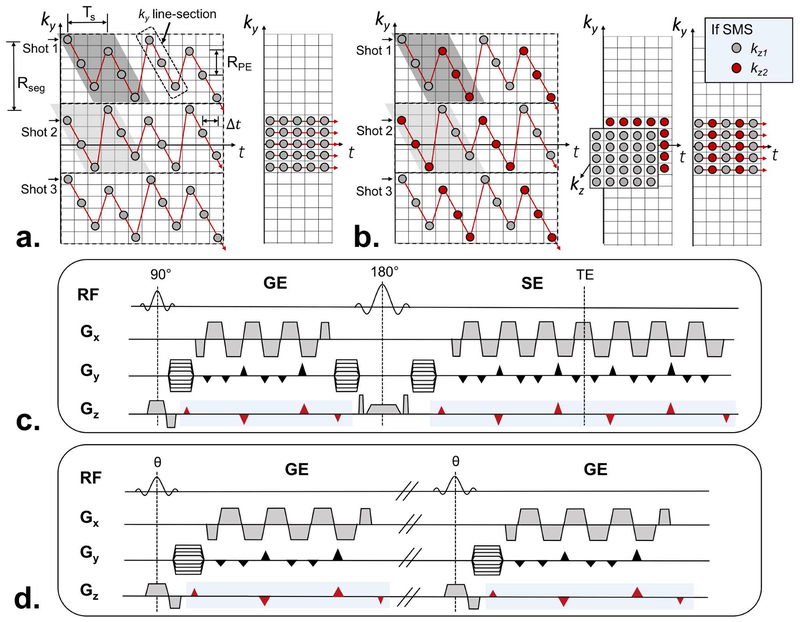

Figure 2a provides a detailed description of EPTI using a 3-shot EPTI acquisition as an example. Each EPTI-shot includes several diagonal ky line-sections that contain a plurality of temporally adjacent readout lines acquired in a temporally sequential manner. These readout lines are spaced apart in time by an EPI echo-spacing (Δt) and in PE direction by RPE. Within each EPTI-shot, two temporally adjacent ky line-sections are interleaved in the PE direction with complementary ky sampling, and repeated multiple times across the readout. An example of such interleaved pair of ky line-sections for shot 1 is highlighted in dark-gray in Figure 2a. This complementary undersampling is designed to better utilize the coil sensitivity in the B0-informed reconstruction. Here, the two adjacent ky line-sections are separated by another temporal spacing Ts, equal to the product of the echo spacing (Δt) and the number of data samples in each ky line-section (Ns). As such, the number of ky lines covered by each EPTI shot, Rseg, is RPE×Ns. For a typical brain acquisition at 3T (1 mm resolution with 200 ky lines, FOVy = 20 cm), Rseg will usually be set to 20–40, resulting in 5–11 EPTI-shots. Ns is usually selected to keep Ts to be in the order of 5–10 ms, to ensure that the phase accumulation and signal decay are small between adjacent ky line-sections. The different EPTI-shots are acquired in consecutive TRs, with a modified starting ky line-section pattern for even-numbered EPTI-shots (light-gray highlight in Fig. 2a) to ensure a uniform undersampling across the shots along the ky line-sections. With this strategy, only a small number of GRAPPA-like (23) kernel patterns are needed in the shot-combined reconstruction (see below).

FIG. 2.

Detailed description of EPTI sampling pattern and sequence diagram. (a) Multiple shots are used to cover the ky-t space, each with a spatial and temporal CAIPI trajectory that contains multiple diagonal ky line-sections. Each of these ky line-sections includes a number of temporally adjacent readout lines (dot) spacing apart in time by an EPI echo spacing Δt and in PE direction by RPE. The two adjacent ky line-sections are interleaved in the PE direction (highlighted in gray), and separated in time by a spacing of Ts, equal to the product of the echo spacing (Δt) and the number of data samples in each ky line-section (Ns). The segment size along PE direction of each shot (Rseg) can be determined by the product of RPE and Ns. A low-resolution calibration scan can be acquired by 20–30 EPI readouts without any phase encoding blips as shown on the right. (b) The red and gray color illustrate the sampling pattern when SMS is applied into EPTI acquisition at MB=2. The fully-sampled low resolution calibration data (kx-ky-kz-t) can be acquired as shown in the middle. This fully-sampled acquisition can be further accelerated using blipped-CAIPI SMS as shown on the right, in which case additional short SMS calibration data is acquired and used to reconstruct the EPTI calibration data first. The sequence diagrams of (c) GESE-EPTI, and (d) GE-EPTI are also shown, where EPTI readout can be continuously played out in the sequence to achieve high efficiency. The marked blue region indicates the Gz gradients that should be applied when SMS is employed.

B0-informed parallel imaging reconstruction

The EPTI reconstruction uses GRAPPA-like (23) compact kernels to interpolate the undersampled kx-ky-t data, similar to the approach that has previously been employed for accelerated PSF-EPI data (46). For each horizontal line in ky-t space, the signal differences of the neighboring k-space points would be i) B0-inhomogeneity-induced phase, and ii) T2* decay/T2’ recovery. Since the neighboring points along time are close together, the signal differences should be small. The small and spatially-smooth phase accumulation can be considered as an additional encoding information that can be estimated by a convolutional kernel in k-space, while the small T2* decay/T2’ recovery can be approximated by a linear interpolation within the kernel. Here, each reconstruction kernel is designed to cover two adjacent ky line-sections, spanning several milliseconds. The missing data points are recovered by a weighted combination of their neighboring points in a multi-channel dataset as follows (46),

| (1) |

Where si(kx, ky, t) is the missing data point of the i-th channel at position (kx, ky, t) to be reconstructed, is the acquired data point inside the kernel denoted by K, j is the index of channels counting from 1 to the total number of channels Nc, and wi is the weights of the kernel containing coil sensitivity and B0-inhomogeneity information.

After this ky-t reconstruction, inverse Fourier transforms are applied along the phase- and frequency-encoding directions at each time point to obtain a series of images with different T2/T2*-weighted contrasts. The reconstruction kernels are trained using a low-resolution kx-ky-t calibration data as shown on the right panel of Figure 2a. Typically, 20–30 phase encodings are acquired in the training dataset, using an EPSI-like acquisition.

SMS-EPTI

To further accelerate EPTI, SMS is incorporated into the sequence using multiband RF excitation and an optimized ky-kz-t sampling trajectory (Fig. 2b). The blipped-CAIPI acquisition technique (41) is used here to improve the reconstruction quality by better utilizing the coil sensitivity. For SMS acquisition with a multiband (MB) acceleration of 2, a partition-encoding blip is applied after each ky line-section in an EPTI-shot. The polarity of this Gz blip alternates as the acquisition moves from one ky line-section to the next as shown in Figure 2c&d. This moves the kz sampling positions from +dkz to −dkz, and then from −dkz to +dkz for subsequent ky line-section to achieve good sampling coverage in ky-kz-t space. Note that other suitable Gz blip schemes can also be employed for different acquisition protocols and MB accelerations. For B0-informed reconstruction, the reconstruction kernel is extended by one more dimension along slice direction to jointly reconstruct the k-space for simultaneously acquired slices.

The fully-sampled low resolution calibration data (kx-ky-kz-t) should be acquired as shown in Figure 2b (middle). To minimize the time needed for calibration, this fully-sampled acquisition can also be accelerated using the blipped-CAIPI SMS as shown in Figure 2b (right), in which case additional short SMS calibration data is acquired and used to reconstruct the EPTI calibration data first using slice-GRAPPA (41).

Sequence diagram

The EPTI acquisition can be incorporated into different sequences to acquire different contrasts and signal evolution information. As a proof of concept, two types of EPTI sequences were created: i) GESE-EPTI as shown in Figure 2c, and ii) GE-EPTI as shown in Figure 2d. In GESE-EPTI, a 90° and a 180° pulse are played out, while the EPTI readout is employed to fill any dead time in the sequence to obtain the signal evolution of an FID followed by a SE. The resulting multi-contrast data enables the calculation of a number of quantitative maps including T2, T2*, proton density, B0, and SWI/quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). In GE-EPTI, no 180° pulse is added to the sequence, allowing for a shorter TR for fast multi-contrast dynamic imaging such as in dynamic T2* imaging, multi-echo BOLD fMRI and functional QSM (fQSM).

Navigator-free estimation and correction of shot-to-shot B0-variations

The B0-inhomogeneity can vary across different EPTI-shots due to respiration and/or physiological noises. As such, each reconstructed ky segment from a given EPTI-shot is contaminated with an added image phase from B0-variation specific to that shot, causing artifacts in the segment-combined images. This issue is analogous to that in rs-EPI for diffusion imaging (29,47), with phase corruption being much smaller than in diffusion. In rs-EPI, the phase contaminations are estimated and corrected using additional navigators and an image-based phase-correction for each segment (29). Unlike diffusion rs-EPI, in EPTI, the amount of phase contamination will increase linearly during each readout at multiple TEs, causing images at the later time-points to contain larger phase contaminations (with GESE-EPTI, it will also decrease linearly between the 180o and the spin-echo as B0 phase unwinds). If the shot-to-shot B0-variations (sB0) can be estimated, the amount of phase contamination at each time-point along the EPTI readout can be corrected for.

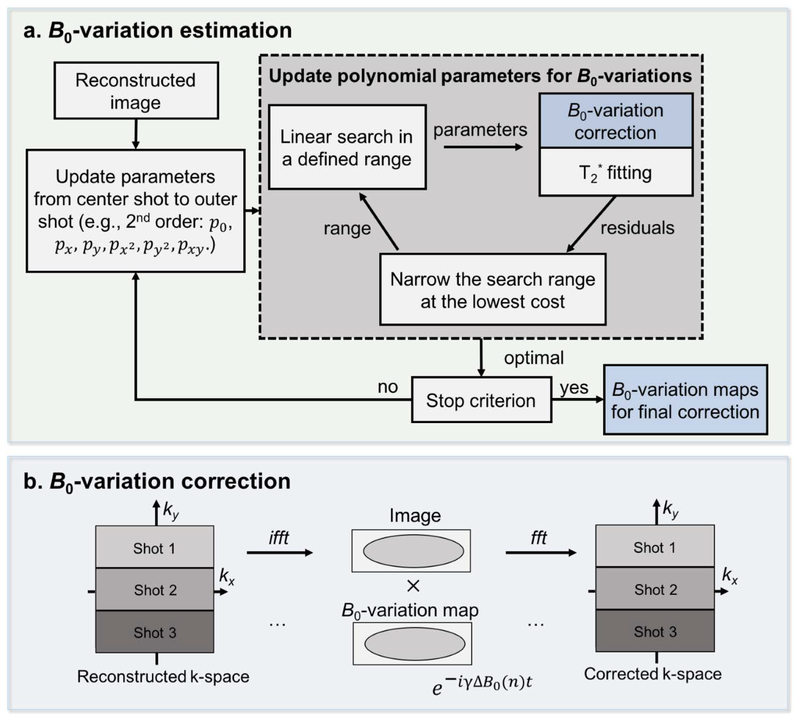

With our current acquisition, we expect sB0 to be small and spatially smooth, such that they can be approximated well using a low order polynomial. With this assumption, a navigator-free B0-variation estimation and correction method was developed (Fig. 3). This method is a data driven approach which relies on a greedy search algorithm (48,49) to find polynomial coefficients that can best approximate sB0 using the acquired EPTI data. The goodness of fit is chosen to be the root mean square error of the T2* fitting from the reconstructed GE EPTI image-series, as reducing phase corruptions should reduce image artifacts and fitting errors. The estimated B0-variation maps are then used to correct the phase for each segment in the image domain as shown in Figure 3b, similar to the phase correction in rs-EPI (29).

FIG. 3.

An illustration of the proposed self-B0 variation estimation (a) and correction (b). After reconstruction, fully-sampled EPTI-shots can be obtained but with different B0-variations. Polynomial maps are used to estimate these B0-variations assuming they are of sufficient low spatial frequency. To estimate the variation maps, the polynomial parameters are updated iteratively from the center to the outer segments. A linear greedy search algorithm within a selected range is performed for each parameter by selecting the value that gives the minimal residual errors of T2* fitting, assuming that the clean images without artifacts will have minimized residual errors. The estimated B0-variation maps are then used to correct the phase for each segment in the image domain as shown in (b). The corrected segments are combined to obtain the final image series.

Methods

All data were acquired with a consented institutionally approved protocol on a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner with a 32-channel head coil (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Both the simulated and in vivo EPTI data (GE and SE) were reconstructed using low-resolution calibration GE data with 29 PE lines and 23 echotimes, using the same echo spacing as in the imaging data.

Simulation experiments

There are several factors that will affect the performance of EPTI, including the undersampling rates along the time (Ts) and the PE (RPE) directions, the level of B0-inhomogeneity (dB0), and the shot-to-shot B0-variations. Since the effect of RPE is mostly determined by coil sensitivity, an RPE of 4 was selected in our experiments for 32-channel acquisition, which is considered to be at the limit of what this coil can achieve when accelerating across one direction (note that the ‘effective’ acceleration along the phase-encoding in EPTI here is somewhat smaller than 4, as data from adjacent ky line-sections that contain complementary ky undersamplings will be jointly reconstructed). With RPE fixed at 4, simulation experiments were performed to investigate the effect of Ts, dB0, and sB0. Since the gradient-echo and spin-echo EPTI data should behave similarly in terms of these three factors, only the gradient-echo EPTI data were examined in this section.

Acceleration factors

Bloch simulations were used to simulate ky-t EPTI data at different acceleration factors. In order to perform this simulation, proton density, T2, T2*, B0 and coil sensitivity maps were obtained from multiple-TE acquisitions of the single-echo SE sequence and the multi-echo 2D GRE sequence on a healthy subject at a 1×1×3 mm2 resolution. With these parameter maps, a fully-sampled ky-t EPTI data was simulated with a realistic T2/T2* decay and B0-inhomogeneity induced phase. An echo spacing of 0.93 ms was used, which corresponds to the minimum echo spacing achievable for this 1-mm EPTI protocol on the Prisma scanner. Four EPTI acquisitions that utilize different total numbers of acquisition shots (5, 7, 9, 11 shots) and hence different Rseg sizes (44, 32, 24, 20 lines) were created by undersampling the simulated fully-sampled data. The RPE was kept at 4 for all of the four cases, resulting in time intervals between adjacent ky line-sections (Ts) of 10.23 ms, 7.44 ms, 5.58 ms, and 4.65 ms, respectively. Note that the data matrix sizes (kx×ky×t) of the different EPTI cases will be slightly different, since the number of total ky-lines is the product of the number of shots and Rseg, and t should be a multiple of Ns. Nonetheless, its effect on the image resolution is negligible and should not affect the comparison between acquisitions. The matrix sizes used were (kx=224) × (ky=220, 224, 216, 220) × (t=88, 96, 96, 100). Spatially uncorrelated Gaussian noise was also added to the k-space data to mimic the in vivo conditions, with the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) set to 40. Reconstruction was performed for the four EPTI cases, and the normalized Root Mean Squared Error (nRMSE) between the reference images and the reconstructed images were calculated for evaluation.

Levels of B0-inhomogeneity (dB0)

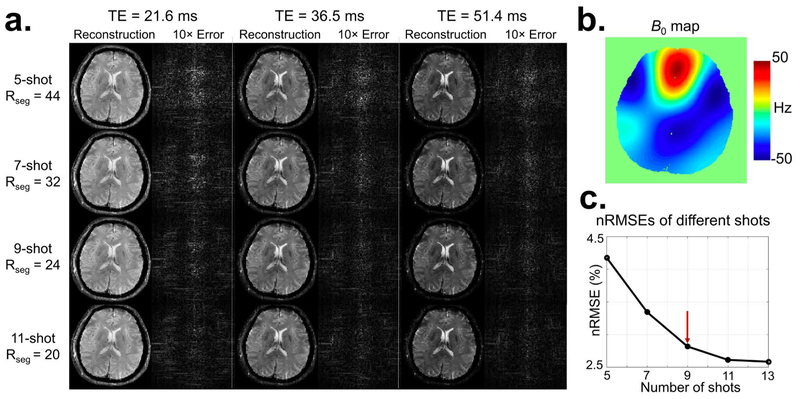

In order to investigate the performance of EPTI under different B0-inhomogeneity levels, fully-sampled reference data and 9-shot EPTI data with B0-inhomogeneity with ranges of ±25 Hz, ±50 Hz, ±75 Hz, ±100 Hz were simulated. The B0-inhomogeneity maps used in these simulations are scaled versions of the acquired in vivo map shown in Figure 4b that has a range of ±50 Hz.

FIG. 4.

The results of simulation experiments investigating varying acceleration factors. A larger size of each EPTI shot (Rseg), and thus higher undersampling along PE and time, leads to reduced shot numbers for a given resolution. (a) Reconstructed images of different EPTI shots and their corresponding 10× error maps at 3 selected TEs. All EPTI datasets were simulated using a B0 map with a range of ±50 Hz (b). Figure 4c shows a plot of the average nRMSEs across all TEs vs. the number of EPTI shots. EPTI performed well at all shot numbers with relatively small errors, and the error decreases as the shot number increases due to the reduced undersampling rate. In addition, 9-shot EPTI provides a good tradeoff between image quality and acquisition time.

Shot-to-shot B0-variations (sB0)

To evaluate the effect of shot-to-shot B0-variations, EPTI data were simulated with added sB0 using a time-series of B0 maps obtained from an in vivo scan with a 5-echo spin and gradient echo EPI (SAGE-EPI) sequence (15). A time series of data was acquired with the following parameters: FOV = 224×224 mm2; in-plane resolution = 2×2 mm2; slice thickness = 4 mm, Rinplane = 3, TEs = 25, 68, 111, 154, 197 ms (with the first two TEs acquired prior to the 180o), TR = 2.2 s. The T2 and T2* maps were measured by fitting the images to the signal equation (50), and the B0 map for each TR was calculated using the phase difference. The SAGE-EPI data were interpolated to match with another 1-mm single-echo ss-EPI data (for proton density estimation). This high-resolution image and the interpolated T2, T2* and 9-dynamic B0 maps were used to simulate a 9-shot EPTI data with sB0 corruption. Here, the magnitude of sB0 was scaled by 1.5× to slightly exaggerate the level of shot-to-shot phase variations. Other imaging parameters for this simulation were kept the same as in previous simulations. An additional 9-shot EPTI data without B0-variations was also simulated for comparison.

The proposed self-B0-variation estimation and correction was applied to the reconstructed EPTI data using: a 3rd order polynomial, 2 iterations, a searching range of ±3 Hz. Both the uncorrected and the corrected EPTI data were evaluated against the reconstruction from the EPTI data without shot-to-shot variations. Additionally, resolution and artifact characterizations using PSF analysis was conducted for EPTI, which was then compared against the conventional 3-shot ms-EPI at the same resolution and echo spacing.

In-vivo experiments

Acceleration factors

The first in vivo dataset of prospectively accelerated EPTI was designed to evaluate the performance of EPTI at four different acceleration levels. GESE EPTI data were acquired using the following parameters: FOV = 240 × 240 mm2; in-plane resolution = 1.1×1.1 mm2; slice thickness = 3 mm; number of slices = 19; number of shots = 5, 7, 9, 11; segment size Rseg = 44, 32, 24, 20; RPE = 4; number of echotimes (GE/SE) = 44/88, 48/96, 48/96, 40/80; echo time range of GE/SE = 6.9–48.2 ms/65.8–149.3 ms, 6.7–50.4 ms/68.4–156.7 ms, 6.7–50.4 ms/69.4–157.7 ms, 6.4–42.7 ms/61.8–135.3 ms; TR per shot, TRshot = 3.8 s. The echo-spacing used for the 5-shot acquisition is slightly larger (0.96 ms) than the other acquisitions (0.93 ms) due to the enlarged Gy phase-encoding blips to achieve a large Rseg. After EPTI reconstruction, the self-B0-variation correction was applied to both spin- and gradient-echo data using the B0-variation parameters estimated from gradient-echo data. The final image-series at multiple TEs was then used to calculate T2, T2* and tissue phase.

For comparison, spin-echo ss-EPI and gradient-echo ss-EPI data were also acquired on the same subject with matching resolution, using the following parameters: Rinplane = 3; echo spacing = 0.93 ms; TE/TR for SE = 95/3000 ms and TE/TR was 27/3000 ms for GE. To match the SNR level of the EPTI data, 9 averages of this data were acquired and averaged for comparison. Additionally, standard single-echo SE and multi-echo 2D GRE were acquired to obtain the reference T2, T2* and tissue phase maps, using the following parameters: TEs for SE = 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175 ms; TEs for multi-echo 2D GRE = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 ms.

GESE SMS-EPTI for fast whole brain quantitative imaging

In this experiment, SMS acceleration was incorporated into EPTI to provide faster, whole-brain multi-contrast and quantitative imaging. Whole-brain data were acquired using GESE SMS-EPTI on a healthy volunteer. A 9-shot EPTI acquisition was used with a multiband (MB) acceleration of 2 and a TRshot of 3.1 s for 34 slices, while the other imaging parameters were kept the same as before. The total acquisition time for this whole-brain 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 quantitative imaging acquisition is 27.9 s (3.1 s × 9 shots). Three averages were acquired to boost the SNR of the quantitative maps. A low-resolution calibration data was also acquired with MB = 2 (total ~23 s).

GE SMS-EPTI for fMRI

The feasibility of EPTI for dynamic quantitative imaging was tested using a time-series of GE SMS-EPTI acquisition to provide dynamic T2* quantification in a blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) fMRI experiment. Imaging parameters were: FOV = 240×240×102 mm3; in-plane resolution = 2×2 mm2; slice thickness = 3 mm; number of shots = 3; Rseg = 40; RPE×MB = 4×2; echo spacing = 0.66 ms; number of GE echotimes = 60; echo time range = 6.2–45.1 ms; flip angle = 64°; TRshot = 1.1 s (providing a temporal resolution to the fMRI experiment of 3.3 s). Data were acquired for a total of 6 minutes, with visual stimulus presentation following a standard block-design paradigm consisting of a 25-second full-field black-and-white “checkerboard” pattern contrast-reversing at 12 Hz followed by a 30-second uniform gray field. An initial 20-second fixation period was performed. To assist with fixation, a red dot with time-varying brightness was positioned at the center of the screen, and the subjects were asked to press a button as soon as they detected a change in brightness. Data were reconstructed using EPTI reconstruction with self-B0-variation correction. For each TR, T2* was estimated through a mono-exponential fit of the multi-contrast images, and a weighted-average based combination of images acquired at different TEs was also generated by using the method in (9,51). Statistical analysis was then performed on both the weighted-average magnitude data and the T2* time course using a General Linear Model (GLM) as implemented in FSL (52–55). The data were motion corrected and smoothed with a Gaussian kernel with 5-mm FWHM, and activation was identified with a standard GLM using the stimulus timing convolved with a canonical double-gamma hemodynamic response function (HRF) that included a temporal derivative term to account for slight temporal offsets in the response timing. Clusters were determined by Z>2.3 and a cluster significance threshold of p=0.05 was used to threshold the statistical maps.

Results

Figure 4 shows the results from the simulation experiments investigating the effects of Rseg acceleration. Figure 4a shows reconstructed images of the different acceleration cases and their corresponding 10× error maps at 3 selected TEs, with the corresponding B0 map (range ±50 Hz) shown in Figure 4b. The reconstructed images at all Rseg acceleration levels are of high quality and low errors. The error decreases with decreasing Rseg and hence increasing number of EPTI-shots as expected. Figure 4c shows the plot of the average nRMSE across all TEs vs. the number of EPTI shots, where 9-shot EPTI provides a good tradeoff between image quality and scan time for this acquisition at 1 mm in-plane resolution, and therefore 9-shot EPTI was used in all subsequent tests. The effect of the level of B0 inhomogeneity on EPTI reconstruction was also investigated in the Supporting Information (Fig. S1), which shows the ability of EPTI to provide high quality images even in presence of large B0 inhomogeneity (±100 Hz).

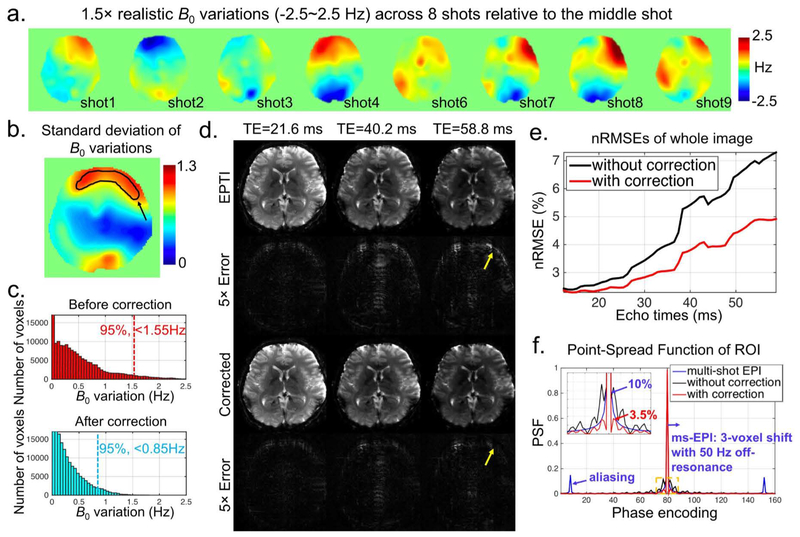

Figure 5 examines the effects of B0 shot-to-shot variations on EPTI and the effectiveness of the proposed self-B0-variation correction. Figure 5a shows the B0-variations (±2.5 Hz) across 8 EPTI-shots relative to the middle 5th EPTI-shot in a simulated 9-shot EPTI acquisition. A standard deviation map of sB0 across the 9 EPTI-shots is also shown in Figure 5b. Figure 5c depicts the histograms of the original simulated B0-variations and the residual effective B0-variations after correcting B0-variation induced phase. The residual effective B0-variations are the equivalent field variations corresponding to the corrected phase values. The proposed correction reduces the maximum B0-variation component from 2.5 Hz to 1.5 Hz, and the upper bound of the B0-variation components in 95% of the voxels from 1.55 Hz to 0.85 Hz. Figure 5d shows the reconstructed images with and without self-B0-variation correction, as well as their corresponding 5× error maps at 3 selected TEs. Overall, the errors from B0-variations in EPTI are relatively mild, and are reduced by the proposed correction method. The yellow arrows mark the region where the B0 field varies the most (indicated by a black arrow in Fig. 5b) and where the signal intensity is high. As expected, large image errors and artifacts are observed in this region, and they increase with TE as the shot-to-shot phase variation accumulates along the EPTI readout. Figure 5e shows that the nRMSE increases with echo time as expected, with the proposed correction providing markedly lower errors at all echo points.

FIG. 5.

The effects of shot-to-shot B0-variations on EPTI. (a) 1.5× realistic B0-variations with a range of ±2.5 Hz were used to simulate a 9-shot EPTI dataset with phase variations. Eight maps are shown here relative to the middle shot. (b) Spatial distribution of standard deviation of B0-variations across 9 time points, with a marked ROI showing the region with the most-varied B0. (c) The histograms of the original simulated B0-variations and the residual effective B0-variations after correcting B0-variation induced phase. The maximum B0-variation component was reduced from 2.5 Hz to 1.5 Hz, and the upper bound of the B0-variation components in 95% of the voxels from 1.55 Hz to 0.85 Hz. (d) The reconstructed images and their corresponding 5× error maps at three selected TEs, with yellow arrows indicating the regions with the most varied B0 field as shown in (b). (e) The nRMSEs of the whole image as a function of echo times with and without correction. (f) PSFs of the conventional interleaved multi-shot EPI, and EPTI with and without correction. Note that only the middle part of the PE direction is shown here (the actual size is 224).

Results from the voxel’s PSF analysis of the shot-to-shot B0-variations are shown in Figure 5f. Here, the EPTI data without (black) and with (red) correction were compared against conventional 3-shot ms-EPI (blue). Noted that in all three cases, the PSF was generated at a long TE of 58.8 ms with large shot-to-shot phase variations. In all simulations, B0 off-resonance of 50 Hz was used, along with shot-to-shot B0-variation profiles taken from representative voxels in the high-variation area of the image (Fig. 5b black region) to represent a worst-case scenario. As shown in the figure, PSF of the conventional ms-EPI has been broadened across multiple voxels (with ~10% sidelobe) by T2* blurring along the PE direction (assuming T2*=35 ms). Moreover, it also has ~15% ghosting artifacts at ±FOV/3 positions from the shot-to-shot phase variations, as well as an approximately 3-voxel shift along the PE direction due to the imposed 50 Hz off-resonance (not shown). In comparison, the PSF of EPTI does not contain any ghosting artifacts, shifting, or T2* blurring, but only contains local blurring due to shot-to-shot phase variations (black curve). This blurring effect was well mitigated through the proposed correction method, as indicated by the red curve, where the PSF sidelobes are reduced to only ~3.5%.

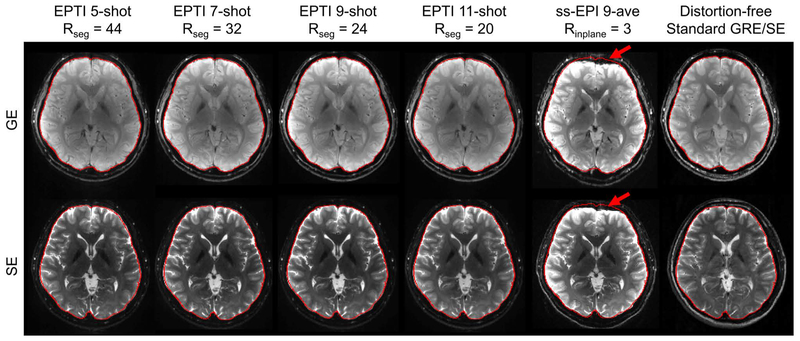

Figure 6 shows the reconstruction results of in vivo GESE-EPTI at different prospective acceleration levels. For each acquisition, gradient-echo and spin-echo images were averaged respectively to obtain a combined GE and a combined SE image. These combined EPTI images show high-SNR and good image quality without any noticeable artifacts, even at a large Rseg undersampling rate of 44. In addition, these images are free from geometric distortion as their brain boundaries are identical to those extracted from distortion-free standard GRE/SE images shown on the right. Here, a ss-EPI image at Rinplane=3, averaged across 9 repetitions is included for comparison where severe distortions can be seen on both GE and SE images (red arrows). Note the contrast differences in the GE and SE images from EPTI vs. ss-EPI or standard GRE/SE, which can be attributed to differences in the effective TEs, slightly different TRs, and the fact that the GE data in EPTI was acquired as part of a 90o-180o GESE acquisition, with the additional 180o causing changes in spin-history/contrast.

FIG. 6.

Results of in-vivo experiments with different EPTI shots at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 resolution. Combined GE and SE EPTI images eliminated the severe distortion appeared in ss-EPI (red arrows), and achieved high-SNR artifact-free images under all acceleration factors. The brain boundaries were extracted from distortion-free standard GRE/SE acquisition as shown on the right and overlaid on the EPTI and ss-EPI images for comparison.

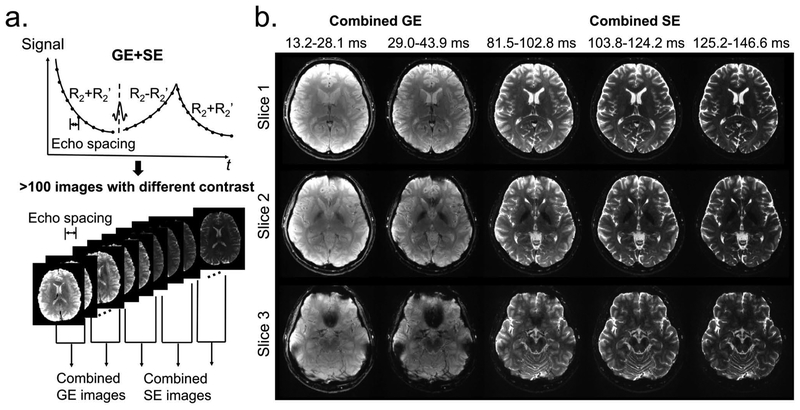

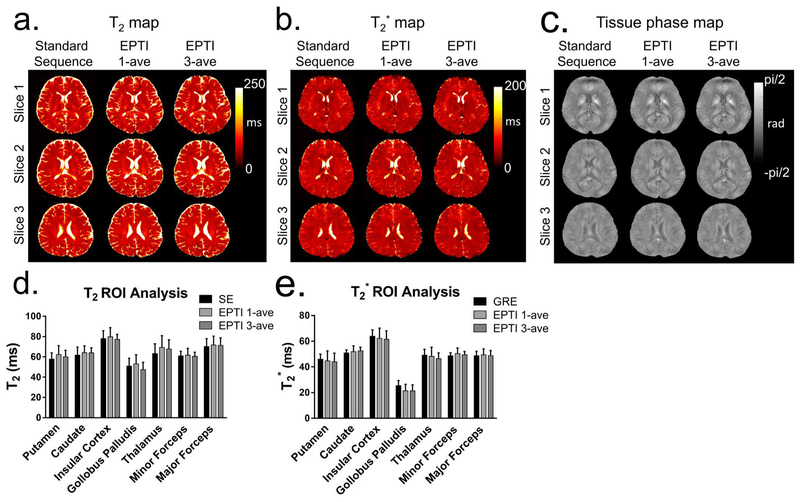

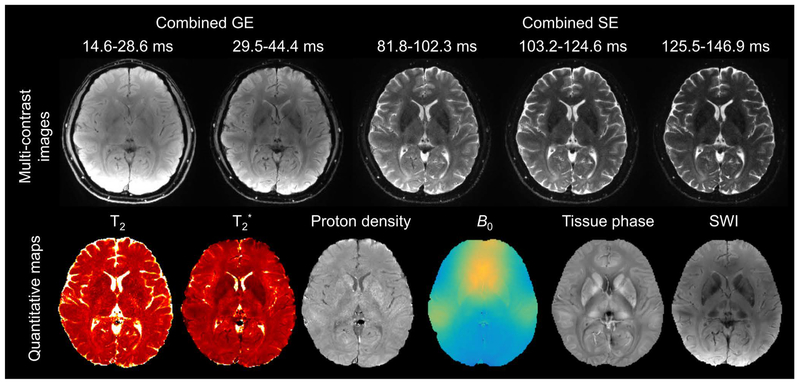

Multi-contrast images obtained from the 9-shot GESE-EPTI acquisition are shown in Figure 7, where a series of images were created at different time points on the signal evolution curve (Fig. 7a), and averaged across several TE ranges to generate combined multi-contrast images with enhanced SNR (Fig. 7b). It can be seen that the resulting multi-contrast images are of high-quality and are distortion-free. Signal and contrast variations across TEs are well captured, with the amount of signal dropout in strong B0 through-slice dephasing regions increasing with TE and then refocusing back as expected at the center SE image. T2, T2* and tissue phase were also calculated and shown in Figure 8 using 1-average 9-shot EPTI, 3-average 9-shot EPTI, and standard GRE/SE method, respectively. It can be seen that EPTI can be used to acquire high-resolution quantitative maps with image quality close to that of the conventional standard methods. The 3-average acquisition further increases image SNR especially in regions in the middle of the brain that inherently have relatively poor coil sensitivity. A ROI analysis of different tissues is shown (Fig. 8e&f) for quantitative comparison. The quantitative values of EPTI in different ROIs are relatively consistent with the standard sequence. The sources of small differences between these acquisitions could be i) subject movements during and between the scans, especially for the long standard acquisitions; ii) different fitting methods and different sampled echo times; and iii) reconstruction errors and noise. To provide further quantification, fully-sampled ky-t data was acquired on a phantom containing a number of T2 and T2* compartments, and retrospectively undersampled to EPTI pattern. Details of the acquisition and evaluations are included in Supporting Information (Fig. S2).

FIG. 7.

Multi-contrast images obtained by 9-shot EPTI acquisition at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 resolution. (a) The signal evolution curve acquired by GESE-EPTI consists of more than 100 images with a time interval of an echo spacing. These images are averaged in several TE ranges to generate combined multi-contrast images with enhanced SNR as shown in (b). Multi-contrast images at 3 slices and 5 TE ranges are shown without distortion/blurring.

FIG. 8.

(a, b and c) T2, T2* and tissue phase maps calculated from the single-average and 3-average 9-shot EPTI, as well as standard GRE/SE. EPTI acquired high-resolution quantitative maps with image quality close to that of the standard GRE/SE, but with dramatically reduced scan time: EPTI obtained these maps simultaneously within 34.2 s (19 slices, up to 21 slices), which was much faster than the conventional SE (~28 min, 10 slices) and GRE (~7 min, 10 slices). The 3-average acquisition further increases image SNR for more accurate quantification. (e and f) An ROI analysis of T2 and T2* for different tissues is shown for quantitative comparison.

Figure 9 shows the in vivo results from GESE SMS-EPTI, where whole-brain scan at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 can be performed in only 27.9 s. This rapid scan provides distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast images that can be used to extract multiple quantitative maps as shown in Figure 9. Here, 3 averages were used to boost the SNR, and with a calibration scan of 23 s, the total scan time of this dataset is 107 s. As shown in the figure, the selected multi-contrast images, T2, T2*, proton density, B0 maps, as well as tissue phase and SWI show high SNR and good image quality.

FIG. 9.

Multi-contrast images and quantitative maps acquired by GESE SMS-EPTI at 1.1×1.1×3 mm3 resolution with whole-brain coverage (34 slices) using 9-shot EPTI. The acquisition time for a single average was 27.9 s, and 3 averages were used to boost the SNR. The calibration scan was about 23 s. The combined multi-contrast images, T2, T2*, proton density, B0 map, as well as tissue phase and SWI were obtained simultaneously, demonstrating the high efficiency of EPTI to obtain high-resolution high-quality multi-contrast and quantitative images without distortion/blurring.

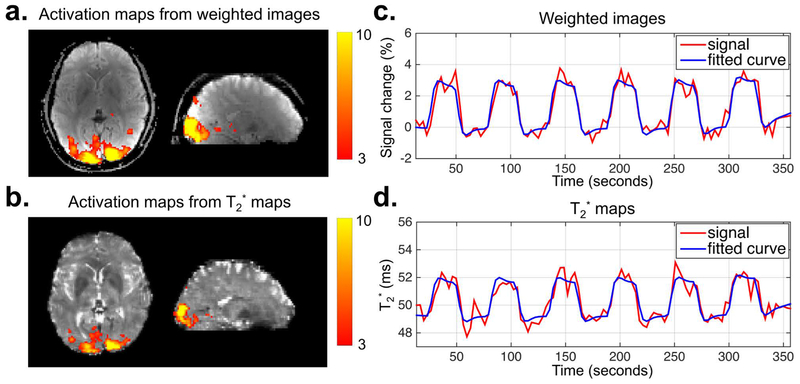

The results of the fMRI response to visual stimulation calculated from time-series of the weighted images and T2* maps acquired using GE-EPTI are shown in Figure 10, including the z-score activation maps, the percent signal change for weighted images and the T2* signal values of a voxel with the peak z-score. In this experiment, 3-shot GE-EPTI was used to provide a temporal resolution of 3.3 s for a whole-brain acquisition at 2×2×3 mm3 resolution, where distortion-free images at 34 echotimes were obtained for each TR. Strong activation was observed within the occipital cortex in both of the activation maps calculated by the weighted images and T2* maps, and there is a strong correspondence between the signal and the visual stimulus timing as shown in Figure 10c&d. Moreover, the result from T2* maps shows a smaller activation region compared to that of the weighted images, probably due to the higher contrast-to-noise ratio of the weighted images (11). Overall, these results demonstrate the potential in using EPTI for multi-echo fMRI to enhance functional sensitivity and to provide a means of detecting BOLD activation from quantitative imaging data.

FIG. 10.

The results of the fMRI experiment acquired by GE SMS-EPTI with visual stimuli from a single subject. The z-score activation maps (a and b), the percentage signal change curve of the weighted images (c) and the T2* value curve (d) (from the maximum z statistic voxel) are shown. A temporal resolution of 3.3 s per volume was provided by 3-shot GE SMS-EPTI with a whole-brain coverage at a 2×2×3 mm3 resolution. The multi-contrast images acquired at 34 TEs for each TR were used to generate a time series of weighted images and T2* maps for activation analysis as shown in the top and bottom row respectively. Both results show strong activation in the occipital cortex, and strong correspondence between the signal changes (red) and the task contrast (blue).

Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, EPTI was proposed as a new rapid imaging technique for distortion- and blurring-free multi-contrast imaging and quantitative imaging. A new spatial-temporal sampling trajectory was developed to achieve high accelerations, and to ensure the robustness to artifacts from shot-to-shot B0-variations, that have plagued many existing ms-EPI approaches. The approach was demonstrated in vivo for brain imaging, both in retrospectively and prospectively accelerated acquisitions, where EPTI was shown to be robust to both B0 inhomogeneity and shot-to-shot B0-variations. The efficacy of EPTI for fast, high-resolution ‘time-resolved’ imaging was then demonstrated through a GESE SMS-EPTI acquisition. This acquisition provides hundreds of multi-contrast images that can be used to estimate T2, T2*, proton density, B0 and SWI maps at about 1.1 mm in-plane resolution in a timeframe of 0.8 s per imaging slice. The application of EPTI for dynamic imaging was also demonstrated through a GE SMS-EPTI acquisition for whole-brain multi-echo and quantitative T2* fMRI at a 2-mm in-plane resolution and a 3.3 s temporal resolution. This preliminary results show the feasibility of EPTI for multi-echo fMRI, which has been demonstrated in the past to provide enhanced functional sensitivity (9,51), and to reduce vulnerability to physiological noise and motion/spin-history artifacts by measuring BOLD activation from quantitative T2* (12,56). EPTI should also prove useful to a number of other current and new applications that could benefit from fast quantitative and dynamic imaging, and the adaption of the EPTI acquisition concept into other sequences/contrasts is readily feasible.

The spatio-temporal CAIPI undersampling in EPTI allows for an efficient coverage of a large section of ky-t space with each EPTI-shot, and the B0-informed parallel imaging reconstruction allows this highly undersampled data to be reconstructed using compact k-space kernels that can effectively interpolate data in ky-t space (For SMS-EPTI, the acquisition and reconstruction are done jointly in kx-ky-kz-t space). The proposed ky-t acquisition not only enables image formation from all ky lines at the same echo time, thus achieving distortion- and blurring-free imaging, but also provides a ‘time-resolved’ imaging series with a rapid temporal sampling rate equal to that of the echo-spacing (~1 ms). With this time-resolved approach, the EPTI readout can be applied continuously within the sequence to fill any dead time, leading to a very high acquisition efficiency. Compared to a multi-echo EPI approach which can also fill out sequence dead time, the spatial resolution specification in EPTI does not dictate the desired number of image TEs acquired, but rather depends on the number of EPTI-shots and the ky coverage of each shot (Rseg).

The selection of the undersampling rate along ky (RPE), kz (MB) and time (Ts) will affect the performance of EPTI. The use of larger RPE and Ts factors will help increase ky coverage of each EPTI-shot (Rseg), which will reduce the number of acquisition shots and provide faster scan. The key factors that determine the achievable RPE, MB and Ts are i) the ability of coil sensitivities of the receiver array to approximate spatial harmonics to interpolate along ky and kz (57); and ii) the ability of B0-informed interpolation to approximate the image phase evolution along t. The spatio-temporal CAIPI undersampling pattern and joint kx-ky-kz-t reconstruction should also play key roles in helping push the achievable RPE, MB and Ts. According to the simulation experiment, 9-shot EPTI with 32 channels was able to achieve high-quality images at about 1 mm resolution even in the presence of exaggerated B0-inhomogeneity with a range up to ±100 Hz, using RPE = 4, Ts ~5.6 ms, and Rseg = 24. Note that since coil sensitivities should also contribute to approximate B0-inhomogeneity induced image phase, not only the level but also the spatial frequency content of the B0-inhomogeneity are important in determining Ts. In brain imaging, areas of high B0-inhomogeneity with strong spatial variabilities are typically located at the air-tissue interface in the periphery of the brain, where the coil sensitivities are also varying rapidly in space and thus providing good encoding ability. This likely helped contribute to the ability of EPTI to achieve very high accelerations. The use of shared information among neighboring echoes in the spatio-temporal interpolation enables high acceleration, but also results in temporal noise correlation along echo-time domain. The degree to which this happens is analyzed in the supplementary figure (Fig. S3). This spatio-temporal reconstruction also complicates the g-factor calculation. Hence, empirical g-factor (58,59) was calculated based on the reduction factor along PE and noise correlation along echo-time direction (Fig. S4).

The effect of shot-to-shot B0-variations on the EPTI acquisition and reconstruction was characterized. Instead of inducing strong ghosting artifacts along y as in conventional ms-EPI, B0-variations only lead to a small local spatial smoothing in the EPTI PSF. The self-B0-variation estimation and correction method was developed to mitigate this smoothing, and was demonstrated to provide ~70% reduction in the PSF sidelobes, resulting in sidelobes level of only 3.5% even in an area with strong B0-variations. Our current approach utilizes a polynomial fitting to estimate B0-variations and the use of more complex fittings or approaches that exploit data structures or priors similar to (27,60) could allow for further mitigation.

The proposed EPTI reconstruction utilizes coil and B0 information to recover k-t data, and approximates signal decay by linear interpolation in local kernels. However, such interpolation might lead to temporal smoothing or local errors in the signal curve if decay rates are different for calibration data and target undersampled data. Therefore, the Ts and hence the temporal kernel width in this work is in the range of several milliseconds, which causes only local signal smoothing or small errors for the T2 and T2* range of interest in the brain (see Fig. S2 for supporting evidence). The effect of the different decay rates of calibration and target data on reconstruction was also proved minor in Figure S5. Future work will explore the use of a model based reconstruction that can directly account for the signal decay information, and the partial separability and sparsity constraints similar to ones in (61,62). Such an approach could allow further accelerations and more accurate signal-evolution reconstruction for short T2* species. Moreover, to allow for motion robustness, motion-corrected reconstruction approaches could also be integrated into EPTI, either using the image domain (63,64) or k-space (65) approach.

EPTI utilizes a continuous readout that helps it achieve high SNR acquisition efficiency. Nonetheless, owing to its fast encoding and short scan, the reconstructed images at high spatial resolution can still be noisy and multiple data averages might still be required. In this work, SMS has been incorporated to boost the SNR efficiency of EPTI, and the development of 3D-EPTI to further boost SNR will be explored in future work. In addition, including inversion preparation or a variable flip angle train could sensitize EPTI to more contrast (e.g. T1) (66) and also achieve further acceleration. The ability of EPTI to provide rapid time-resolved imaging opens up new possibilities in a number of directions, including multicompartment tissue fitting, numerous dynamic imaging applications, and the development of new techniques to fully-harness the rich information that the EPTI acquisition can provide.

Supplementary Material

FIG. S1. Simulation for different levels of B0-inhomogeneity using 9-shot EPTI acquisition. The reconstructed images and the corresponding 10× error maps under four levels of B0-imhomogeneity (±25 Hz, ±50 Hz, ±75 Hz, ±100 Hz) are shown. A higher level of inhomogeneity leads to larger image errors, and nRMSE increases with echo time due to signal decay. However, the error is still relatively low at ±100 Hz without any obvious image artifacts.

FIG. S2. A fully-sampled ky-t data was acquired on a phantom at 1×1×3 mm3 resolution using 216 shots. The fully-sampled data was then retrospectively undersampled to generate a 9-shot GESE-EPTI dataset with Rseg = 24 to evaluate the performance of EPTI for quantitative T2/T2* mapping. The imaging parameters were: FOV = 216×216 mm2, echo spacing = 0.95 ms, TRshot = 2.5 s, echo time range of GE/SE = 16.3–53.4 ms / 84.3–161.3 ms. The T2 and T2* maps calculated from fully-sampled data and EPTI are shown in (a, b) and (d, e), and the corresponding ROI analysis of T2 and T2* are shown in (c) and (f) respectively. The estimated T2 and T2* values of EPTI are similar to the fully-sampled data even at a reduction factor of 24 along PE direction, which demonstrates the ability of EPTI for quantitative mapping under high accelerations. Figure S2 (g) and (h) present the signal curves (GE and SE) of a single image pixel using fully-sampled and EPTI-reconstructed data. The zoomed-in GE signal evolution of EPTI data is also shown in (i).

FIG. S3. A Monte Carlo based simulation was performed on a 9-shot EPTI dataset with 45 echoes. The voxel-wise noise correlation (a) of the 45 echoes relative to the middle 23rd echo was calculated using 128 replicas. The high noise correlation of the adjacent echoes results from the use of shared information among neighboring echoes in the EPTI reconstruction, which then drops quickly after 3–4 echoes. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the mean noise correlation of all voxels is 7.6 echoes (~ 7 ms). The noise covariance matrix of all 45 echoes is also shown in (b). As can be seen, the temporal correlation exists as expected, but there is still sufficient amount of independency for linear regression, considering EPTI is able to provide more than 100 echoes in a single scan.

FIG. S4. (a) The empirical g-factor of 9-shot EPTI was calculated using 128 replicas according to the reduction factor along phase-encoding direction (Rseg = 24) and the effective width of neighboring data along echo-time domain that is used to reconstruct a single echo image. Here, the effective data width is characterized by the correlation along echo-time dimension (FWHMcorr), and is specified by the FWHM of the noise correlation as shown in Fig. S3. SD represents standard deviation of the real part for each voxel location through the stack of replicas. The maximum g-factor is 2.01, and the mean g-factor is 1.30. (b) In addition, empirical SNR maps of fully-sampled single-echo, EPTI single-echo and EPTI echo-combined are shown.

FIG. S5. The T2 (a) and T2* (b) maps obtained from the reconstructed 9-shot EPTI images using GE and SE calibration data with different signal decay rates. (c, d, and e) The signal evolution curves of three selected voxels reconstructed using GE and SE calibration data were compared with the signal evolution of a fully-sampled data. As shown in the plots, the signal evolutions of the data reconstructed from GE and SE calibration both agree well with the fully-sampled data, and the difference between their corresponding quantitative maps are small, indicating the minor effects of using calibration data with different decay rates for local interpolation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH NIBIB (R01-EB020613, R01-EB019437, R01-MH116173, P41-EB015896 and U01-EB025162) and by the MGH/HST Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging; and was made possible by the resources provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grants S10-RR023401, S10-RR023043, and S10-RR019307.

References

- 1.Bernstein MA, King KF, Zhou XJ. Handbook of MRI pulse sequences: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansfield P. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J Phys C: Solid State Phys. 1977;10:L55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warach S, Gaa J, Siewert B, Wielopolski P, Edelman RR. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butts K, de Crespigny A, Pauly JM, Moseley M. Diffusion‐weighted interleaved echo‐planar imaging with a pair of orthogonal navigator echoes. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswal B, Zerrin Yetkin F, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo‐planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong K. Functional magnetic resonance imaging with echo planar imaging. Functional MRI: Springer. 1996; p73–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelman RR, Siewert B, Darby DG, Thangaraj V, Nobre AC, Mesulam MM, Warach S. Qualitative mapping of cerebral blood flow and functional localization with echo-planar MR imaging and signal targeting with alternating radio frequency. Radiology 1994;192:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kucharczyk J, Vexler ZS, Roberts TP, Asgari HS, Mintorovitch J, Derugin N, Watson A, Moseley M. Echo-planar perfusion-sensitive MR imaging of acute cerebral ischemia. Radiology 1993;188:711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posse S, Wiese S, Gembris D, Mathiak K, Kessler C, Grosse-Ruyken M-L, Elghahwagi B, Richards T, Dager SR, Kiselev VG. Enhancement of BOLD-contrast sensitivity by single-shot multi-echo functional MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiskopf N, Klose U, Birbaumer N, Mathiak K. Single-shot compensation of image distortions and BOLD contrast optimization using multi-echo EPI for real-time fMRI. Neuroimage 2005;24(4):1068–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poser BA, Versluis MJ, Hoogduin JM, Norris DG. BOLD contrast sensitivity enhancement and artifact reduction with multiecho EPI: parallel‐acquired inhomogeneity‐desensitized fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1227–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagberg G, Indovina I, Sanes J, Posse S. Real‐time quantification of T changes using multiecho planar imaging and numerical methods. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowland P, Bowtell R. Theoretical optimization of multi-echo fMRI data acquisition. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jochimsen TH, Möller HE. Increasing specificity in functional magnetic resonance imaging by estimation of vessel size based on changes in blood oxygenation. Neuroimage 2008;40:228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmiedeskamp H, Straka M, Newbould RD, Zaharchuk G, Andre JB, Olivot JM, Moseley ME, Albers GW, Bammer R. Combined spin‐and gradient‐echo perfusion‐weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiselev VG, Strecker R, Ziyeh S, Speck O, Hennig J. Vessel size imaging in humans. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichner C, Jafari‐Khouzani K, Cauley S, Bhat H, Polaskova P, Andronesi OC, Rapalino O, Turner R, Wald LL, Stufflebeam S. Slice accelerated gradient‐echo spin‐echo dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging with blipped CAIPI for increased slice coverage. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:770–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emblem KE, Mouridsen K, Bjornerud A, Farrar CT, Jennings D, Borra RJ, Wen PY, Ivy P, Batchelor TT, Rosen BR. Vessel architectural imaging identifies cancer patient responders to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Med. 2013;19:1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reber PJ, Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Correction of off resonance‐related distortion in echo‐planar imaging using EPI‐based field maps. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:328–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson JL, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 2003;20:870–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong HK, Gore JC, Anderson AW. High‐resolution human diffusion tensor imaging using 2‐D navigated multishot SENSE EPI at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong Z, Wang F, Ma X, Zhang Z, Dai E, Yuan C, Guo H. Interleaved EPI diffusion imaging using SPIR i T‐based reconstruction with virtual coil compression. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1525–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen N-k, Guidon A, Chang H-C, Song AW. A robust multi-shot scan strategy for high-resolution diffusion weighted MRI enabled by multiplexed sensitivity-encoding (MUSE). Neuroimage 2013;72:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mani M, Jacob M, Kelley D, Magnotta V. Multi‐shot sensitivity‐encoded diffusion data recovery using structured low‐rank matrix completion (MUSSELS). Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:494–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter D, Mueller E. Multi-shot diffusion-weighted EPI with readout mosaic segmentation and 2D navigator correction. In Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2004; p 442. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holdsworth SJ, Skare S, Newbould RD, Guzmann R, Blevins NH, Bammer R. Readout-segmented EPI for rapid high resolution diffusion imaging at 3T. Eur J Radiol 2008;65:36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansfield P Spatial mapping of the chemical shift in NMR. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1:370–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng H, Constable RT. Image distortion correction in EPI: comparison of field mapping with point spread function mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robson MD, Gore JC, Constable RT. Measurement of the point spread function in MRI using constant time imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.In M-H, Posnansky O, Speck O. High-resolution distortion-free diffusion imaging using hybrid spin-warp and echo-planar PSF-encoding approach. NeuroImage 2017;148:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin FH, Tsai SY, Otazo R, Caprihan A, Wald LL, Belliveau JW, Posse S. Sensitivity‐encoded (SENSE) proton echo‐planar spectroscopic imaging (PEPSI) in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaitsev M, Hennig J, Speck O. Point spread function mapping with parallel imaging techniques and high acceleration factors: fast, robust, and flexible method for echo‐planar imaging distortion correction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam F, Ma C, Clifford B, Johnson CL, Liang ZP. High‐resolution 1H‐MRSI of the brain using SPICE: data acquisition and image reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:1059–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma C, Lam F, Ning Q, Johnson CL, Liang ZP. High‐resolution 1H‐MRSI of the brain using short‐TE SPICE. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:467–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng X, Lam F, Li Y, Clifford B, Liang ZP. Simultaneous QSM and metabolic imaging of the brain using SPICE. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang F, Dong Z, Reese TG, Bilgic B, Manhard MK, Wald LL, Setsompop K. Echo Planar Time-resolved Imaging (EPTI). In Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2018; p 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larkman DJ, Hajnal JV, Herlihy AH, Coutts GA, Young IR, Ehnholm G. Use of multicoil arrays for separation of signal from multiple slices simultaneously excited. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Setsompop K, Gagoski BA, Polimeni JR, Witzel T, Wedeen VJ, Wald LL. Blipped‐controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for simultaneous multislice echo planar imaging with reduced g‐factor penalty. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1210–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang F, Akao J, Vijayakumar S, Duensing GR, Limkeman M. k‐t GRAPPA: A k‐space implementation for dynamic MRI with high reduction factor. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1172–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsao J, Boesiger P, Pruessmann KP. k‐t BLAST and k‐t SENSE: Dynamic MRI with high frame rate exploiting spatiotemporal correlations. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1031–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lam F, Liang ZP. A subspace approach to high‐resolution spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:1349–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Posse S, Tedeschi G, Risinger R, Ogg R, Bihan DL. High speed 1H spectroscopic imaging in human brain by echo planar spatial‐spectral encoding. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong Z, Wang F, Reese TG, Manhard MK, Bilgic B, Wald LL, Guo H, Setsompop K. Tilted-CAIPI for highly accelerated distortion-free EPI with point spread function (PSF) encoding. Magn Reson Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porter DA, Heidemann RM. High resolution diffusion‐weighted imaging using readout‐segmented echo‐planar imaging, parallel imaging and a two‐dimensional navigator‐based reacquisition. Magn Reson Med 2009;62:468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cauley SF, Setsompop K, Bilgic B, Bhat H, Gagoski B, Wald LL. Autocalibrated wave‐CAIPI reconstruction; Joint optimization of k‐space trajectory and parallel imaging reconstruction. Magn Reson Med 2017;78:1093–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luenberger DG, Ye Y. Linear and nonlinear programming: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmiedeskamp H, Straka M, Bammer R. Compensation of slice profile mismatch in combined spin‐and gradient‐echo echo‐planar imaging pulse sequences. Magn Reson Med 2012;67:378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kundu P, Voon V, Balchandani P, Lombardo MV, Poser BA, Bandettini PA. Multi-echo fMRI: A review of applications in fMRI denoising and analysis of BOLD signals. NeuroImage 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, Beckmann C, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage 2009;45:S173–S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004;23:S208–S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woolrich MW, Ripley BD, Brady M, Smith SM. Temporal autocorrelation in univariate linear modeling of FMRI data. Neuroimage 2001;14:1370–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gowland P, Bowtell R. Theoretical optimization of multi-echo fMRI data acquisition. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sodickson DK, Manning WJ. Simultaneous acquisition of spatial harmonics (SMASH): fast imaging with radiofrequency coil arrays. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robson PM, Grant AK, Madhuranthakam AJ, Lattanzi R, Sodickson DK, McKenzie CA. Comprehensive quantification of signal‐to‐noise ratio and g‐factor for image‐based and k‐space‐based parallel imaging reconstructions. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:895–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breuer FA, Kannengiesser SA, Blaimer M, Seiberlich N, Jakob PM, Griswold MA. General formulation for quantitative G‐factor calculation in GRAPPA reconstructions. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uecker M, Lai P, Murphy MJ, Virtue P, Elad M, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. ESPIRiT—an eigenvalue approach to autocalibrating parallel MRI: where SENSE meets GRAPPA. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:990–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao B, Haldar JP, Christodoulou AG, Liang Z-P. Image reconstruction from highly undersampled (k, t)-space data with joint partial separability and sparsity constraints. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2012;31:1809–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tamir JI, Uecker M, Chen W, Lai P, Alley MT, Vasanawala SS, Lustig M. T2 shuffling: Sharp, multicontrast, volumetric fast spin‐echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:180–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guhaniyogi S, Chu ML, Chang HC, Song AW, Chen Nk. Motion immune diffusion imaging using augmented MUSE for high‐resolution multi‐shot EPI. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:639–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang F, Bilgic B, Dong Z, Manhard MK, Ohringer N, Zhao B, Haskell M, Cauley SF, Fan Q, Witzel T. Motion‐robust sub‐millimeter isotropic diffusion imaging through motion corrected generalized slice dithered enhanced resolution (MC‐gSlider) acquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:1891–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dong Z, Wang F, Ma X, Dai E, Zhang Z, Guo H. Motion‐corrected k‐space reconstruction for interleaved EPI diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1992–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL, Griswold MA. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature 2013;495:187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIG. S1. Simulation for different levels of B0-inhomogeneity using 9-shot EPTI acquisition. The reconstructed images and the corresponding 10× error maps under four levels of B0-imhomogeneity (±25 Hz, ±50 Hz, ±75 Hz, ±100 Hz) are shown. A higher level of inhomogeneity leads to larger image errors, and nRMSE increases with echo time due to signal decay. However, the error is still relatively low at ±100 Hz without any obvious image artifacts.

FIG. S2. A fully-sampled ky-t data was acquired on a phantom at 1×1×3 mm3 resolution using 216 shots. The fully-sampled data was then retrospectively undersampled to generate a 9-shot GESE-EPTI dataset with Rseg = 24 to evaluate the performance of EPTI for quantitative T2/T2* mapping. The imaging parameters were: FOV = 216×216 mm2, echo spacing = 0.95 ms, TRshot = 2.5 s, echo time range of GE/SE = 16.3–53.4 ms / 84.3–161.3 ms. The T2 and T2* maps calculated from fully-sampled data and EPTI are shown in (a, b) and (d, e), and the corresponding ROI analysis of T2 and T2* are shown in (c) and (f) respectively. The estimated T2 and T2* values of EPTI are similar to the fully-sampled data even at a reduction factor of 24 along PE direction, which demonstrates the ability of EPTI for quantitative mapping under high accelerations. Figure S2 (g) and (h) present the signal curves (GE and SE) of a single image pixel using fully-sampled and EPTI-reconstructed data. The zoomed-in GE signal evolution of EPTI data is also shown in (i).

FIG. S3. A Monte Carlo based simulation was performed on a 9-shot EPTI dataset with 45 echoes. The voxel-wise noise correlation (a) of the 45 echoes relative to the middle 23rd echo was calculated using 128 replicas. The high noise correlation of the adjacent echoes results from the use of shared information among neighboring echoes in the EPTI reconstruction, which then drops quickly after 3–4 echoes. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the mean noise correlation of all voxels is 7.6 echoes (~ 7 ms). The noise covariance matrix of all 45 echoes is also shown in (b). As can be seen, the temporal correlation exists as expected, but there is still sufficient amount of independency for linear regression, considering EPTI is able to provide more than 100 echoes in a single scan.

FIG. S4. (a) The empirical g-factor of 9-shot EPTI was calculated using 128 replicas according to the reduction factor along phase-encoding direction (Rseg = 24) and the effective width of neighboring data along echo-time domain that is used to reconstruct a single echo image. Here, the effective data width is characterized by the correlation along echo-time dimension (FWHMcorr), and is specified by the FWHM of the noise correlation as shown in Fig. S3. SD represents standard deviation of the real part for each voxel location through the stack of replicas. The maximum g-factor is 2.01, and the mean g-factor is 1.30. (b) In addition, empirical SNR maps of fully-sampled single-echo, EPTI single-echo and EPTI echo-combined are shown.

FIG. S5. The T2 (a) and T2* (b) maps obtained from the reconstructed 9-shot EPTI images using GE and SE calibration data with different signal decay rates. (c, d, and e) The signal evolution curves of three selected voxels reconstructed using GE and SE calibration data were compared with the signal evolution of a fully-sampled data. As shown in the plots, the signal evolutions of the data reconstructed from GE and SE calibration both agree well with the fully-sampled data, and the difference between their corresponding quantitative maps are small, indicating the minor effects of using calibration data with different decay rates for local interpolation.