Abstract

Background:

Well over 700,000 United States military personnel participated in the Persian Gulf War in which they developed chronic health disorders of undetermined etiology. Up to 25% of Veterans had persistent and chronic GI symptoms, which they suspected were related to their military service in the Gulf.

Aim:

The overall aim of the current study was to evaluate intestinal permeability in previously deployed Gulf War Veterans who developed chronic GI symptoms during their tour in the Persian Gulf. Methods: To accomplish this, we evaluated intestinal permeability (IP) using the urinary lactulose/mannitol test. Measurements of intestinal permeability were then correlated with mean ratings of daily abdominal pain, frequency of bowel movements, and consistency of bowel movements on the Bristol Stool Scale in all Veterans.

Results:

A total of 73 veterans had documented chronic GI symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal pain) and were included in the study. A total of 29/73 (39%) of veterans has increased IP and had a higher average daily stool frequency (p<0.05); increased liquid stools as indicated by a higher Bristol Stool Scale (p<0.01); and a higher mean M-VAS abdominal pain rating (p<0.01). Pearson correlation coefficients revealed that there was a positive correlation between increased IP and stool frequency, Bristol Stool Scale, and M-VAS abdominal pain rating.

Conclusion:

Our study demonstrates that deployed Gulf War Veterans with persistent GI symptoms commonly have increased intestinal permeability that potentiates the severity of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and stool consistency. These new findings in our study are important as they may lead to novel diagnostic biomarkers for returning Gulf War Veterans who suffer from chronic functional gastrointestinal disorders. These advances are also important for an increasing number of veterans who are now serving in the Persian Gulf and are at a high risk of developing these chronic pain disorders.

Keywords: Intestinal Permeability (IP), Gastrointestinal (GI), Mechanical Visual Analog Scale (M-VAS)

INTRODUCTION

Well over 700,000 United States military personnel participated in the Persian Gulf War between August 1990 and March 1991. By April 1997, the Persian Gulf Registry had identified a large number of these veterans as having chronic health disorders of undetermined etiology. Within 6 to 12 months after their return from the war, up to 25% of Veterans had persistent, that is chronic, GI symptoms, which they suspected were related to their military service in the Gulf1,5,8. The economic impact of these chronic GI disorders (workup, treatment, indirect costs, lost work) is estimated to be over $897 million (VA Environmental Epidemiology Service). Indeed, costs continue to grow because a large number of veterans still serve in the Middle East and are at high risk for developing the same chronic disorders.

Among the symptoms most frequently reported by veterans with Gulf War Illness (GWI) were chronic fatigue, frequent or persistent headache, frequent or persistent muscle or joint pain, and GI symptoms. GI symptoms (e.g. diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain) reported by these veterans accounted for the majority of complaints.6,15,21 It is estimated that over 50% of veterans deployed in the Gulf during the Gulf war in 1990–1991 developed acute gastroenteritis.10 Thus, acute gastroenteritis may be an underlying factor leading Gulf War Veterans to develop GWI with persistent GI symptoms.19–20 In addition, veterans deployed to the Persian Gulf are exposed to a highly stressful environment, perhaps making them more susceptible to the development of chronic GI symptoms.

Because both animal and human studies of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)14 indicate that intestinal hyperpermeability is a potential mediating factor for chronic visceral pain, we investigated a possible role for intestinal hyperpermeability in the hypersensitivity to nociceptive stimuli observed in previously deployed Gulf War Veterans with chronic GI symptoms. Accordingly, the overall aim of the current study was to evaluate intestinal permeability in previously deployed Gulf War Veterans who developed chronic GI symptoms during their tour in the Persian Gulf. To accomplish this, we evaluated intestinal permeability using the urinary lactulose/mannitol test. Veterans with and without increased Intestinal permeability were then correlated with mean ratings of daily abdominal pain, frequency of bowel movements, and consistency of bowel movements on the Bristol Stool Scale.

METHODS

Participants

The study was done at The Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Cincinnati, Ohio and the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating centers. All veterans signed informed consent documents prior to the start of the study. We enrolled consecutive veterans that were seen in the VA outpatient clinics who were previously deployed to the Persian Gulf and developed chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain during their Persian Gulf War tour from January 2016 through June 2017. To be eligible for inclusion into the study, Gulf War Veterans needed to be deployed and had developed chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain while serving in the Persian Gulf, that had lasted for at least 5 years. They all previously had upper endoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies and a capsule endoscopy that were normal; a normal lactulose breath test to exclude bacterial overgrowth; a negative serum tissue transglutaminase to exclude celiac sprue; and negative stool studies.

Veterans who had consumed alcohol and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents during the 4 weeks prior to study entry, which could affect intestinal permeability, were excluded.12–13 All Gulf War Veterans completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).2,22 Depressive and anxiety disorders were exclusions if they were severe enough to interfere with the individual’s ability to participate in the study. Therefore, veterans who scored ≥30 on the BDI and/or ≥53 on the STAI were excluded. Such scores are at least one standard deviation above the mean for general medical patients. All veterans underwent a 7-day screening period during which their daily abdominal pain score was recorded on a Mechanical Visual Analog Scale (M-VAS) and a mean was calculated for each veteran.18 All veterans also underwent a 7-day screening period during which their daily stool frequency and stool form on the Bristol Stool Scale were recorded and a mean was calculated for each.

Following collection of 7 days of data above, on day 7, participants then underwent a 24-hour urine collection for intestinal permeability testing following ingestion of a solution of lactulose and mannitol. This intestinal permeability test directly measures the ability of mannitol and lactulose to permeate across the intestinal mucosa. After an overnight fast, each veteran emptied his or her bladder and then ingested 5 g of lactulose together with 2 g of mannitol dissolved in 100 ml of water. Each veteran was then instructed on how to collect their urine every 5 hours over the next 24 hours. The sample were then analyzed for lactulose and mannitol. Increased intestinal permeability (increases in permeability between intestinal epithelial cells) was defined as a urinary lactulose/mannitol ratio of ≥ 0.07. Veterans were stratified into two groups, one with increased intestinal permeability (IP) (urinary lactulose/mannitol ratio ≥ 0.07) and one with normal permeability as previously described.26 In comparison to lactulose, mannitol is easily absorbed and serves as a marker of transcellular uptake, while lactulose is only slightly absorbed and serves as a marker for paracellular permeability and mucosal integrity.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SAS software, Version 9.4 of the SAS system (SAS Institute Inc., city, state) and Prism version 6. Sample size calculations were based on a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. A total enrollment of 70 Gulf War Veterans was needed to attain a power of 80% to detect an absolute difference between patients with increased vs. normal intestinal permeability. The analysis involved one between- (IP) and two within-subject (stool form/frequency) variables. Differences between veterans with normal and increased permeability were tested. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s comparison was used to analyze the data. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Pearson correlations between the lactulose/mannitol ratio and the M-VAS abdominal pain ratings, average daily stool frequency, and the Bristol Stool Scale were analyzed.

RESULTS

A total of 298 veterans were recruited from the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida (n=27) and Cincinnati VAMC in Cincinnati, Ohio (n=46) who had been deployed to the Persian Gulf for a duration of 6–24 months (mean: 16.3 months). A total of 73/298 (24.4%) of these veterans had documented chronic GI symptoms and abdominal pain. These GI symptoms started during their deployment to the Persian Gulf and continued after their return from that deployment. We did not include Gulf War Veterans without GI symptoms and diarrhea as a preliminary study done revealed they have normal intestinal permeability. Prior to deployment, none of the veterans had any history of co-of functional bowel disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or bacterial overgrowth. Veterans were excluded who consumed >2 alcohol drinks/day, regularly took NSAIDs, antidepressants, and/or opiate medications. Veterans were stratified into 2 groups based on the results of the intestinal permeability testing: (1) increased intestinal permeability (increased urinary lactulose/mannitol (L/M) ratio of ≥ 0.07) and (2) normal intestinal permeability. Analysis of the data revealed that there were 2 groups of veterans (with/without increased permeability) and that the data did not Demographics of the enrolled Gulf War Veterans were similar in the 2 groups (Table 1). Mean age of the veterans with normal IP was 46.1±2.9 and in the increased IP group, 47.4±3.1years and 100% were male. There was no significant difference between the two groups in age or ethnicity (p=0.8, 0.7).

Table 1.

Demographics of Gulf War Veteran*

| Normal IP (N=44) |

Increased IP (N=29) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ||

| Age−years | 46.1±2.9 | 47.4±3.1 |

| Sex−no. (%) | ||

| Male | 44 (100) | 29 (100) |

| Female | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnic group-no. (%) | ||

| White | 27 (61) | 19 (66) |

| Black | 17 (39) | 10 (34) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

Plus-minus values are means±SD. Intestinal Permeability (IP)

Intestinal Permeability (L/M ratio)

Of the 73 Gulf War veterans with abdominal pain and diarrhea, 29 (39.7%) had intestinal hyperpermeability (L/M ≥ 0.07) (0.10±0.03). The rest had normal permeability (L/M < 0.07): n = 44 (60.3%) (0.04±0.02) (p<0.001). Additional analysis revealed that there was no significant effect of age, race, or deployment time on intestinal permeability.

Daily Stool frequency (#/day)

All Gulf War Veterans with chronic GI symptoms had an increased frequency of bowel movements. There was a significant difference in stool frequency between the two groups. There was higher stool frequency in the veteran group with intestinal hyper-permeability ~ 1.8-fold greater number of stools per day than veterans with normal intestinal permeability (*p<0.05) (Figure 1). Additional analysis revealed that there was no significant effect of age, race, or deployment time on stool frequency.

Figure 1.

Average Daily Stool Frequency, Gulf War Veteran with normal permeability (N-IP), Gulf War Veterans with increased permeability (I-IP), *p<0.05. Error bars =SD

Stool Consistency (Bristol Stool Scale)

All Gulf War Veterans with chronic GI symptoms and increased permeability had semi-formed to liquid stools. Veterans with intestinal hyperpermeability exhibited a 2.2-fold higher mean Bristol Stool Scale rating compared to veterans with normal permeability (**p<0.01) (Figure 2). Additional analysis revealed that there was no significant effect of age, race, or deployment time on stool consistency.

Figure 2.

Average Daily Bristol Stool Scale, Gulf War Veteran with normal permeability (N-IP), Gulf War Veterans with increased permeability (I-IP), **p<0.01. Error bars=SD.

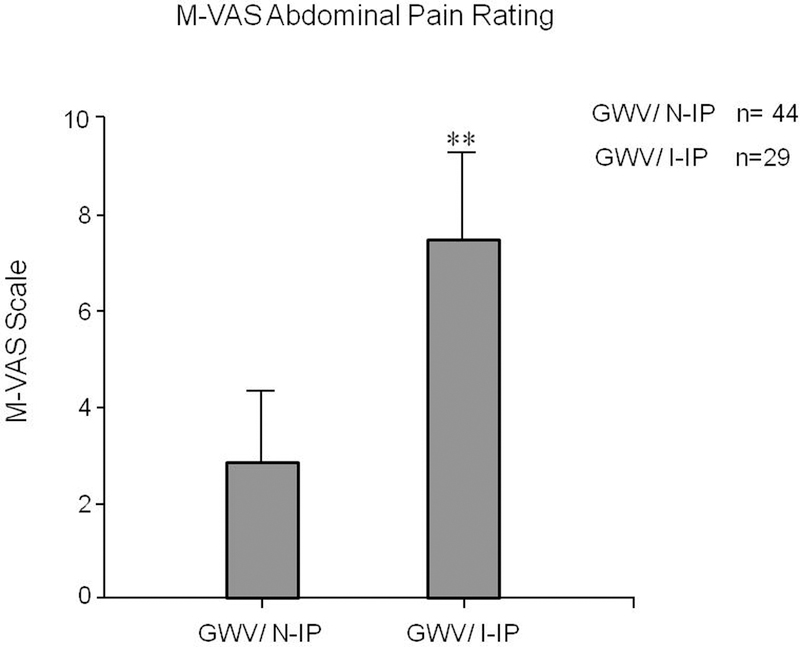

M-VAS Abdominal Pain Ratings

M-VAS abdominal pain readings were done in both groups of the veterans. Veterans with increased intestinal permeability had a higher mean M-VAS abdominal pain reading compared to veterans with normal intestinal permeability (**p<0.01) (Figure 3). Additional analysis revealed that there was no significant effect of age, race, or deployment time on M-VAS Abdominal Pain Ratings.

Figure 3.

Average Daily M-VAS Abdominal Pain Rating, Gulf War Veteran with normal permeability (N-IP), Gulf War Veterans with increased permeability (I-IP), **p<0.01. Error bars=SD.

Intestinal Permeability Correlations

Pearson correlations between intestinal permeability (lactulose/mannitol ratio) and the main outcome measures of abdominal pain, stool frequency, and stool consistency were calculated (Table 2). Among Gulf War Veterans with GI symptoms and increased intestinal permeability, there were significant positive correlations between IP and M-VAS abdominal pain ratings, between IP and daily stool frequency, and between IP and stool consistency. Among veterans with GI symptoms but normal intestinal permeability, there were no significant correlations between these pairs of variables. Correlation obviously does not prove causation, but these findings are consistent with there being an effect of intestinal hyperpermeability on GI symptoms in-affected veterans.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients for increased IP vs. normal IP

| Normal IP (N=44) |

Increased IP (N=29) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Permeability (IP) (Lactulose/Mannitol ratio) | ||

|

M-VAS Abdominal Pain Rating |

0.17, p=0.08 | 0.723, p<0.01 |

| Stool frequency (no./day) | 0.20, p=0.1 | 0.761, p<0.01 |

|

Stool consistency Baseline |

0.19, p=0.1 | 0.692, p<0.01 |

| *Intestinal Permeability | 0.04 | 0.10, p<0.001 |

Plus-minus values are means±SD

Stool consistency was measured using the Bristol Stool Scale

Intestinal permeability (IP) was measured with the urinary lactose/mannitol ratio

DISCUSSION

We found, consistent with earlier reports, that the onset of GI symptoms in veterans with GWI is common during deployment of veterans to the Persian Gulf, and often persists after deployment.6,21 Our study also provides several important new findings. First, intestinal hyperpermeability is very common in veterans – it occurs in ~39% of those who develop chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. To our knowledge, this the first study to examine intestinal permeability in returning Gulf War Veterans. Second, our results show that veterans with intestinal hyperpermeability have higher abdominal pain ratings, greater stool frequency, and looser bowel movements – 2 to 3-fold higher – than veterans without intestinal hyperpermeability. These findings were also clinically significant as they could lead to targeted therapy aimed at restoring more normal intestinal permeability and reducing GI symptoms in veterans with chronic GI symptoms (e.g., visceral pain, diarrhea) and intestinal hyperpermeability.

The major function of the GI tract is to act as an absorptive organ and as a barrier to bacteria, macromolecules, and toxic compounds.3 Disruption of this barrier can lead to local GI dysfunction as well as systemic abnormalities such as bacterial translocation and sepsis. Abnormalities of the immune system or of mechanical barriers of the GI epithelium lead to enhanced uptake of inflammatory luminal macromolecules and pathogenic bacteria. Intestinal inflammation creates a vicious circle by further increasing the permeability of the intestinal barrier, thereby enhancing the uptake and systemic distribution of bacteria and potentially injurious macromolecules such as endotoxin. Alternatively, increased intestinal permeability may result in a feedback loop that maintains or propagates intestinal inflammation. Increased barrier permeability appears to correlate with a number of clinical disorders: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), food allergies, allergic disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, chronic dermatological conditions, and alcoholic cirrhosis.12–13,16 Intestinal permeability may be increased by exogenous factors such as alcohol, NSAIDs, starvation, and stress. More recent literature has focused on increased intestinal permeability as a potential etiologic factor in IBS.23,26,30 Patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS have increased intestinal permeability.7,24,26,30 This increased intestinal permeability may be due to low-grade inflammation that has been reported in mucosal biopsies of a subset of diarrhea-predominant (D-IBS) and post-infectious (PI-IBS) patients, but less commonly in constipation-predominant (C-IBS) and mixed (M-IBS) patients.7

The increased intestinal permeability itself may be due to several factors including stress, inflammation, allergic disorders and/or through decreased glutamine synthetase activity, resulting in decreased intestinal glutamine levels. Several potential causes have been considered including a post-infectious, IBS-like syndrome.23–24 The acute symptoms will usually resolve within a week, although abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating often persist. Interestingly, transient bowel inflammation may cause sensitization of the gut that persists long after resolution of the inflammation, similar to the sensitization shown in animal models of GI pain.4,9,25,27–29

One of the earliest studies of Persian Gulf War veterans with abdominal symptoms was conducted at the Boston Veterans Affairs Medical Center.21 The investigators evaluated deployed and non-deployed members of a single National Guard unit in an attempt to better define the etiology and prevalence of chronic GI symptoms in Persian Gulf War veterans. After a 6–12 month deployment to the Persian Gulf region, up to 80% of the deployed group reported disturbances in their GI functioning. Symptoms included excessive flatulence, loose stools or >3 stools per day, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, watery bowel movements at the onset of abdominal pain and abdominal pain relieved with defecation. About 20% of the deployed veterans reported GI symptoms that persisted following their deployment. The study concluded that the abrupt onset of GI symptoms was coincidental with deployment of the veterans to a stressful wartime environment and was thus suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome; however, the symptom cluster could have been the result of other physical and environmental factors as well.

The current findings extend our previous studies of Gulf War Veterans with chronic GI pain disorders.6,17 The pathophysiologic mechanisms causing chronic GI symptoms are not well understood, but these mechanisms lead to significant morbidity in the Gulf War Veterans population. Indeed, chronic GI symptoms reported by these Veterans accounted for the majority of complaints.8,11,15 In the current study, we identified deployed veterans with chronic GI symptoms who have increased intestinal permeability similar to what we have observed in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.26,30 Although the pathophysiology of chronic GI symptoms in veteransis unknown, increased intestinal permeability could be a major contributing factor.

There are a few limitations of our study. The study was conducted over 20 years after the war and there may be recall bias. Our study population mainly consisted of Gulf War Veterans enrolled in the Gulf War Registry at the Malcom Randall VAMC and at the Cincinnati VAMC. It is not clear whether these findings are applicable to veterans at other VAMCs. Our veterans were more likely to be deployed and to serve in active combat. Also, veterans who agree to participate may be a biased sample that is more likely to report a higher prevalence of disorders. The higher prevalence of bowel disorders after the Gulf War may be due to increased health care utilization and higher reporting by the Veterans after returning from the War.

SUMMARY

Our study demonstrates that deployed Gulf War Veterans with persistent GI symptoms commonly have increased intestinal permeability that potentiates the severity of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and stool consistency. The findings of this study may be applicable as well to veterans returning from other deployment assignments, so future studies of Veterans from other military conflicts is needed. Currently, there are few available treatments for veterans with chronic GI symptoms. The new findings in our study are important as they may lead to novel diagnostic biomarkers for returning Gulf War Veterans who suffer from chronic functional gastrointestinal disorders.31 Therefore, increased understanding of the alterations in intestinal permeability in these veterans may allow the development of new, more effective treatments, aimed at normalizing intestinal permeability such as oral glutamine therapy, that can reduce chronic gastrointestinal symptoms and decrease the predisposition to other chronic pain conditions in Gulf War Veterans. These advances are also important for an increasing number of veterans who are now serving in the Persian Gulf and are at a high risk of developing these chronic pain disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (CX000642–01A1 and CX001477–01); and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK099052).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or other relationship to report that might lead to a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker DG, Mendenhall CL, Simbartl LA, Magan LK, Steinberg JL. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported physical symptoms in Persian Gulf War veterans. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2076–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilleri M, Madsen K, Spiller R, Van Meerveld BG, Verne GN. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:503–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaloner A, Rao A, Al-Chaer ED, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Importance of neural mechanisms in colonic mucosal and muscular dysfunction in adult rats following neonatal colonic irritation. Int J Dev Neurosci 2010;28:99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press; 2014: 10.17226/18623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunphy RC, Bridgewater L, Price DD, Robinson ME, Zeilman CJ, 3rd, Verne GN. Visceral and cutaneous hypersensitivity in Persian Gulf war veterans with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Pain 2003;102:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlop SP, Hebden J, Campbell E, Naesdal J, Olbe L, Perkins AC, Spiller RC. Abnormal intestinal permeability in subgroups of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(6):1288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA 1998;280:981–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Prusator DK, Johnson AC. Animal models of gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Animal models of visceral pain: pathophysiology, translational relevance, and challenges. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;308(11):G885–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyams KC, Bourgeois AL, Merrell BR, et al. Diarrheal disease during Operation Desert Shield. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med 2000; 42(5):491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keshavarzian A, Holmes EW, Patel M, Iber F, Fields JZ, Pethkar S. Leaky gut in alcoholic cirrhosis: A possible mechanism for alcohol-induced liver damage. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94(1):200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshavarzian A, Fields JZ, Vaeth J, Holmes EW. The differing effects of acute and chronic alcohol on gastric and intestinal permeability. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89(12):2205–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130(5):1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy FM, Kang HK, Dalager NA, Lee KY, Allen RE, Mather SH, Kizer KW. The health status of Gulf War veterans: lessons learned from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Registry. Mil Med 1999; 164(5):327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porras M, Martin MT, Yang PC, Jury J, Perdue MH, Vergara P. Correlation between cyclical epithelial barrier dysfunction and bacterial translocation in the relapses of intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price DD, Craggs JG, Zhou Q, Verne GN, Perstein WM, Robinson ME. Widespread hyperalgesia in irritable bowel syndrome is dynamically maintained by tonic visceral impulse input and placebo/nocebo factors: Evidence from human psychophysics, animal models, and neuroimaging. Neuroimage 2009;47(3):995–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain 1994;February;56:217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Tribble DR. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;74:891–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez JL, Gelnett J, Petruccelli BP, Defraites RF, Taylor DN. Diarrheal disease incidence and morbidity among United States military personnel during short-term missions overseas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;58:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sostek MB, Jackson S, Linevsky JK, Schimmel EM, Fincke BG. High prevalence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in a National Guard Unit of Persian Gulf veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:2494–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spielberger CD, Gorusch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2003;124(6):1662–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiller RC. Role of infection in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007;42[Suppl XVII]:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Price DD, Verne GN. Visceral and somatic hypersensitivity in a subset of rats following TNBS-Induced colitis. Pain 2008;134(1–2):9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Q, Souba WW, Croce CM, Verne GN. MicroRNA-29a regulates intestinal membrane permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2010;59:775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Q, Costinean S, Croce C, Brasier A, Verne GN. MicroRNA-29 targets nuclear factor-κB-repressing factor and Claudin 1 to increase intestinal permeability. Gastroenterology 2015;148:158–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Q & Verne GN. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity-clinical implications in IBS Patients. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou Q, Verne GN. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity-clinical implications in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8(6):349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang B, Verne M, Verne GN, Zhou Q. Mechanisms of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Gulf War Illness. Gastroenterology 2016;150(4):Supp1, S740. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Q, Zhang B, Verne GN. Intestinal membrane permeability and hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain 2009;146:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]