Abstract

Sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) promotes lipogenesis and tumor growth in various cancers. It is well known that clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), a major subtype of the kidney cancers, exhibits elevated lipid accumulation. However, it has not been fully understood how lipid metabolism might be associated with cell cycle regulation in ccRCC. In a recent issue, Lee et al. (Molecular and Cellular Biology (2017) pii: MCB.00265-17) demonstrate that SREBP-1c is up-regulated in ccRCC by ring finger protein 20 (RNF20) down-regulation, leading to aberrant lipid storage and pituitary tumor transforming gene 1 (PTTG1)-dependent cell cycle progression. These findings suggest that SREBP-1c serves as a molecular bridge between lipid metabolism and cell cycle control in ccRCC tumorigenesis.

Keywords: lipogenesis, renal cell carcinoma, SREBP-1c

Overview: sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c and tumor growth

Metabolic reprogramming is one of the hallmarks in most cancer cells. Tumor cells exhibit enhanced aerobic glycolysis and elevated lipogenesis to supply energy and building blocks, which are required for excessive cell growth [1]. Sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) are key transcription factors that regulate lipid metabolism and energy storage through the synthesis and uptake of fatty acids, triglycerides, and cholesterol. Mammals have three SREBP isoforms: SREBP-1a, SREBP-1c, and SREBP-2. SREBP-1 primarily controls the lipogenic pathway, whereas SREBP-2 is specific for cholesterol biosynthesis [2]. Previously, it has been reported that SREBPs are associated with aberrant lipid metabolism required for tumor growth [3]. For instance, it has been shown that the Akt/mTOR pathway stimulates SREBP-1c-dependent lipogenesis and SREBP-1c is required for cell survival and tumorigenesis in glioblastoma and breast cancers [4]. Although clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), a major subtype of the kidney cancer, shows ectopic lipid accumulation [5], the underlying mechanisms of the relationship between aberrant lipid metabolism and tumorigenesis in ccRCC are poorly understood. It has been reported that ring finger protein 20 (RNF20), a RING-finger containing E3 ubiquitin ligase, acts as a tumor suppressor by modulating histone monoubiquitination and epigenetic gene expression [6]. Remarkably, Lee et al. [7] demonstrate that RNF20 specifically stimulates polyubiquitination and degradation of SREBP-1c, thereby negatively regulating hepatic lipogenesis upon PKA activation. The present study provides a clue to understand how SREBP-1c is down-regulated by fasting signals to prevent excess lipogenesis. However, RNF20 had not been previously implicated in lipid metabolism-mediated tumor-suppressive function.

Interestingly, in a recent issue of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Lee et al. [8] provided a new clue between lipid metabolism and cell cycle regulation in tumor growth. They now suggest that SREBP-1c could function as a molecular linker between lipogenesis and cell cycle, particularly in ccRCC. In ccRCC patients, RNF20 down-regulation is a marker of poor prognosis. RNF20 inhibits lipogenesis and cell proliferation by suppressing SREBP-1c in ccRCC. Intriguingly, RNF20 represses cell cycle progression by modulating pituitary tumor transforming gene 1 (PTTG1) as a novel SREBP-1c target gene. Thus, the authors have clearly demonstrated that RNF20 acts as a metabolic tumor suppressor by inhibiting SREBP-1c-mediated lipogenesis and cell cycle progression in ccRCC.

New insights into SREBP-1c in kidney cancers

Histologically, ccRCC is characterized by the clear cell phenotype due to lipid accumulation, indicating that metabolic perturbations are a defining feature of this tumor. To date, it has been established that the primary etiology of ccRCC is resulted from inactivation of von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene and the consequent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) [5]. Accordingly, a recent study suggests that HIF-2α promotes lipid storage, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis, and cell viability in ccRCC via up-regulation of the lipid droplet protein PLIN2 [9]. Although this study demonstrates the HIF-2α/PLIN2 axis maintains lipid droplets to protect against ER stress in ccRCC, the underlying mechanisms that are involved in ectopic lipid accumulation and cell cycle regulation in ccRCC have not been fully elucidated. In recent work, Lee et al. [8] have investigated whether SREBP-1c and lipogenesis are required in ccRCC tumor growth. SREBP-1c overexpression promotes lipogenesis and proliferation, whereas genetic and pharmacological inhibition of SREBP-1c abrogates these effects in ccRCC cells. Furthermore, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) reveals that mRNA levels of SREBP-1c and lipogenic genes are up-regulated in ccRCC patients, which is accompanied with advanced tumor stages and poor survival [10]. Mechanistically, it has been found that RNF20 inhibits lipogenesis and cell cycle progression via SREBP-1c in both ccRCC cells and xenograft mouse models. These findings evidently indicate that RNF20 suppresses ccRCC tumorigenesis by inhibiting the SREBP-1c pathway.

Spontaneous deletion of VHL is the most common cause of hereditary and sporadic forms of ccRCC [5]. Apart from VHL loss, ccRCC patients exhibit remarkable genetic heterogeneity and frequent mutations in various metabolic genes such as MET, FLCN, and TSC1/2 [11]. Given that metabolic reprogramming is tightly associated with ccRCC, this type of tumor is often called a metabolic disease [12]. Moreover, it has been reported that HIF-2α antagonists might be beneficial against ccRCC [13,14]. However, there are ccRCC tumors that are resistant to HIF-2α antagonists in both VHL wild-type (SLR21) ccRCC cell lines and patient-derived xenograft tumors with low level of HIF-2α [13,14]. In order to overcome the limited effects of HIF-2α antagonists, alternative therapeutic targets against ccRCC should be elucidated. Lee et al. [8] have identified a novel pathway of SREBP-1c-dependent ccRCC tumor, independent of VHL mutation. First, they show that low level of RNF20 is significantly associated with poor prognosis in ccRCC patients, regardless of VHL mutation status. Second, RNF20 represses SREBP-1c expression and cell growth in both VHL wild-type (ACHN) and VHL-deficient (A498) ccRCC cell lines. Last, the SREBP inhibitor betulin suppresses ccRCC proliferation by down-regulating SREBP-1c and lipogenesis with or without VHL mutation. Therefore, they elucidate a novel pathway involved in a VHL-independent ccRCC tumorigenesis.

Previous studies have shown that SREBP-1c appears to be associated with cell cycle regulation in several aspects. For example, SREBP-1c stimulates expression of key genes involved in cell cycle control [15]. In addition, cell cycle regulated kinases including Cdk1 and Plk1 promote phosphorylation-dependent activation of SREBP-1c during mitosis [16,17]. Moreover, SREBP-regulated miRNAs such as miR-33 and miR-182 co-operate to regulate cell proliferation and cell cycle [18,19]. In the recent study, Lee et al. [8] have found that SREBP-1c promotes cell cycle progression by enhancing expression of PTTG1, a novel target gene of SREBP-1c. PTTG1, also known as securin, not only prevents premature chromosome separation by inhibiting separase activity, but also promotes cell cycle dysregulation by regulating cell cycle genes [20]. The authors clearly demonstrate that SREBP-1c potently stimulates the expression of several cell cycle genes such as PCNA and cyclin A in a PTTG1-dependent manner, potentiating cell proliferation in ccRCC. Thus, SREBP-1c–PTTG1 axis provides new insights that SREBP-1c can directly regulate cell cycle in addition to controlling lipid metabolism through its well-known lipogenic targets.

Lipid availability is crucial for cell viability and cell cycle regulation. For instance, unsaturated fatty acids increase cyclin D1 expression and cell proliferation by activating β-catenin in ccRCC [21]. In addition, the inhibitor of lipogenic enzyme SCD1 suppresses tumor growth and invasiveness of ccRCC [22]. Lee et al. also addressed the question whether lipogenesis is required for induction of PTTG1 and cell cycle genes [8]. They found that the expression of PTTG1 and cell cycle genes is not affected by pharmacological inhibition of lipogenesis using the ACC inhibitor TOFA or the FASN inhibitor C75 or by siRNA-mediated suppression of FASN. These results suggest that SREBP-1c separately regulates lipogenesis and PTTG1-mediated cell cycle progression. Taken together, the present work proposes that SREBP-1c serves as a molecular bridge between lipid metabolism and cell cycle regulation by modulating different pathways, which eventually coalesce to drive ccRCC tumorigenesis. Further insight into connection points between the lipid metabolism and cell cycle might pave the way for the development of effective therapies that target metabolic vulnerabilities of ccRCC.

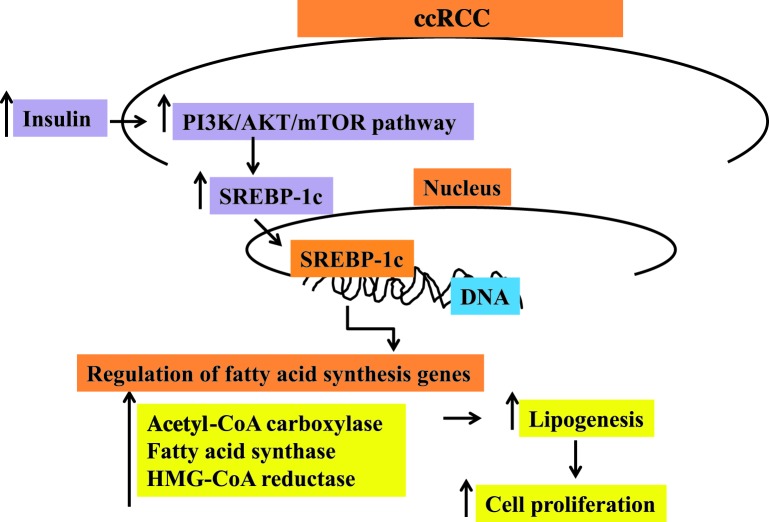

Another SREBP isoform, SREBP-2 plays a key role in tumor transformation and invasion through mevalonate pathway [23]. As described earlier, ccRCC is characterized by the accumulation of neutral lipids such as triglycerides and cholesterol esters. Previous studies have shown that the activity of esterification of cholesterol is significantly higher in ccRCC than in biosynthesis and uptake of cholesterol [24,25]. In accordance with these, Lee et al. [8] observed that the expression of SREBP-2 and cholesterol metabolism genes such as HMG-CoA reductase and LDL receptor appear to be decreased in ccRCC patients. While further studies on the effect of SREBP-2 on ccRCC tumorigenesis are needed, it is plausible to speculate that SREBP-1c will play more oncogenic roles in ccRCC. Figure 1 briefly summarizes the various signal transduction pathways involved in the regulation of SREBP-1c in ccRCC.

Figure 1. Regulation of SREBP-1c in ccRCC.

Future directions

Many studies have reported that SREBP-1c is associated with cell cycle regulation. In recent paper, Lee et al. have identified a novel pathway by which SREBP-1c directly regulates the cell cycle through PTTG1 [8]. Moreover, they have proposed that SREBP-1c seems to regulate lipid metabolism and cell cycle pathways in a separate manner. Although Lee et al. revealed a novel mechanism of SREBP-1c-mediated cell cycle regulation, this study raises a number of important questions that require further investigation [8]. These experiments show that RNF20, a negative regulator of SREBP-1c, is down-regulated in ccRCC. However, it is still unknown how RNF20 expression is down-regulated in ccRCC. Recently, it has been demonstrated that epigenetic regulation of certain genes is important during the tumorigenic [26,27] and metabolic processes [28]. For example, the RNF20 promoter contains prominent CpG islands and is hypermethylated in human breast cancer [6]. In addition, miRNAs have been shown to control the expression of tumor suppressors and oncogenes in various cancers [29]. Thus, it seems that RNF20 expression might be reduced by epigenetic modifications or miRNAs in ccRCC. On the other hand, this work highlights the tumor-suppressive role of RNF20 in ccRCC by inhibiting SREBP-1c. To date, the requirement of the SREBP-1c for tumorigenesis has been reported in several solid tumors, including glioblastoma, breast, prostate, and colon cancer cells [4]. Inflammation is a key driver of cancer progression and also plays an important role in cancer initiation and promotion [30–36]. RNF20 heterozygous null mice are prone to inflammation-mediated colon cancer [37]. According to these studies, it is possible that RNF20 suppresses tumorigenesis by modulating SREBP-1c in a number of solid tumors. Conversely, RNF20 promotes oncogenic transcriptional program in leukemia in which SREBP and fatty acid biosynthesis are suppressed [38,39]. Thus, future studies are needed to reveal whether RNF20–SREBP-1c axis would play central roles in various cancers. Clinically, ccRCC is resistant to cytotoxic agents widely used for cancer treatment. Instead, targetted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and immunotherapy are preferred for ccRCC treatment [40]. To overcome the limitations of conventional therapeutic approaches against ccRCC, many researchers have been studying the underlying mechanisms of ccRCC tumorigenesis. From a mechanistic standpoint, this is a very important finding what Lee et al. have elucidated in VHL-independent ccRCC tumorigenesis [8]. Therefore, it is likely that targetting RNF20–SREBP-1c pathway opens the door to another strategy against ccRCC therapy.

Abbreviations

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ccRCC

clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- Cdk1

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- CpG

5′—C—phosphate—G—3′

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- FLCN

folliculin

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HMG-CoA reductase

3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)

- PKA

protein Kinase A

- PLIN2

Perilipin 2

- Plk1

Polo like kinase 1

- PTTG1

pituitary tumor transforming gene 1

- RNF20

ring finger protein 20

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c

- SCD1

stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1

- TOFA

5-(Tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid

- VHL

von Hippel–Lindau

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Author contribution

M.K.S., A.P.K., and G.S. designed and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Medical Research Council of Singapore, Medical Science Cluster, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore and by the National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under its Research Centers of Excellence initiative to Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, National University of Singapore to Dr. Alan Prem Kumar.

References

- 1.Schulze A. and Harris A.L. (2012) How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature 491, 364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao W. and Espenshade P.J. (2012) Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism. Cell Metab. 16, 414–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon T.I. and Osborne T.F. (2012) SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 65–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo D., et al. (2014) Targeting SREBP-1-driven lipid metabolism to treat cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 2619–2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaelin W.G. (2007) Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2, 145–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shema E., et al. (2008) The histone H2B-specific ubiquitin ligase RNF20/hBRE1 acts as a putative tumor suppressor through selective regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 22, 2664–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J.H., et al. (2014) Ring finger protein20 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism through protein kinase A-dependent sterol regulatory element binding protein1c degradation. Hepatology 60, 844–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.H., et al. (2017) RNF20 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting SREBP1c-PTTG1 axis in kidney cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. pii: MCB.00265–17, 10.1128/MCB.00265-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu B., et al. (2015) HIF2alpha-dependent lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 5, 652–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 499, 43–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlinger M., et al. (2012) Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 883–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linehan W.M., Srinivasan R. and Schmidt L.S. (2010) The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Urol. 7, 277–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho H., et al. (2016) On-target efficacy of a HIF-2alpha antagonist in preclinical kidney cancer models. Nature 539, 107–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W., et al. (2016) Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature 539, 112–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motallebipour M., et al. (2009) Novel genes in cell cycle control and lipid metabolism with dynamically regulated binding sites for sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and RNA polymerase II in HepG2 cells detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation with microarray detection. FEBS J. 276, 1878–1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bengoechea-Alonso M.T. and Ericsson J. (2006) Cdk1/cyclin B-mediated phosphorylation stabilizes SREBP1 during mitosis. Cell Cycle 5, 1708–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bengoechea-Alonso M.T. and Ericsson J. (2016) The phosphorylation-dependent regulation of nuclear SREBP1 during mitosis links lipid metabolism and cell growth. Cell Cycle 15, 2753–2765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cirera-Salinas D., et al. (2012) Mir-33 regulates cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle 11, 922–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeon T.I., et al. (2013) An SREBP-responsive microRNA operon contributes to a regulatory loop for intracellular lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 18, 51–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlotides G., Eigler T. and Melmed S. (2007) Pituitary tumor-transforming gene: physiology and implications for tumorigenesis. Endocr. Rev. 28, 165–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H., et al. (2015) Unsaturated fatty acids stimulate tumor growth through stabilization of beta-catenin. Cell Rep. 13, 496–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Roemeling C.A., et al. (2013) Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 is a novel molecular therapeutic target for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 2368–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baenke F., et al. (2013) Hooked on fat: the role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Dis. Model Mech. 6, 1353–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebhard R.L., et al. (1987) Abnormal cholesterol metabolism in renal clear cell carcinoma. J. Lipid Res. 28, 1177–1184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito K., et al. (2016) Lipidomic signatures and associated transcriptomic profiles of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 6, 28932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akincilar S.C., et al. (2016) Long-range chromatin interactions drive mutant TERT promoter activation. Cancer Discov. 6, 1276–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones P.A. and Baylin S.B. (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu B., et al. (2014) NUCKS is a positive transcriptional regulator of insulin signaling. Cell Rep. 7, 1876–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garzon R., Calin G.A. and Croce C.M. (2009) MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., et al. (1999) Human papillomavirus type 16 E6-enhanced susceptibility of L929 cells to tumor necrosis factor alpha correlates with increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24819–24827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dey A., et al. (2008) Hexamethylene bisacetamide (HMBA) simultaneously targets AKT and MAPK pathway and represses NF kappaB activity: implications for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle 7, 3759–3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sethi G. and Tergaonkar V. (2009) Potential pharmacological control of the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30, 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sethi G., et al. (2012) Multifaceted link between cancer and inflammation. Biosci. Rep. 32, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong L. and Tergaonkar V. (2014) Rho protein GTPases and their interactions with NFκB: crossroads of inflammation and matrix biology. Biosci. Rep. 34, pii: e00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chai E.Z., et al. (2015) Analysis of the intricate relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer. Biochem. J. 468, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanmugam M.K., et al. (2016) Cancer prevention and therapy through the modulation of transcription factors by bioactive natural compounds. Semin. Cancer Biol. 40-41, 35–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarcic O., et al. (2016) RNF20 links histone H2B ubiquitylation with inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer. Cell Rep. 14, 1462–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang E., et al. (2013) Histone H2B ubiquitin ligase RNF20 is required for MLL-rearranged leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 3901–3906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gottfried E.L. (1967) Lipids of human leukocytes: relation to cell type. J. Lipid Res. 8, 321–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rini B.I., Campbell S.C. and Escudier B. (2009) Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet 373, 1119–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]