Abstract

Hydrogen production by biological route is a potentially sustainable alternative. Nowadays, energy production from sustainable sources has become urgent for several countries as well as for international policies. In this perspective, hydrogen has gained substantial global attention as clean, sustainable, and versatile energy carrier. In the current work, the resulting effluent from dark fermentation, rich in organic acids, was used as substrate for the purple non-sulfur bacteria (PNS) Rhodobacter capsulatus. In the first stage, experiments were carried out in bioreactors of 50 mL to check the influence of the composition of the effluent dark fermentation. The results proved that the provision of a sugar source improved bio-H2 production. The lactose and lactic acid concentrations exceeding 4.4 and 12 g/L, respectively, resulted in a productivity of up to 37.14 mmol H2/L days. Based on initial conditions obtained on the previous assays, in the second stage, a photo-fermentation in enlarged scale (1.5 L) was performed with the purpose to monitor the production of hydrogen and metabolites, sugar consumption and growth cells during the process. It was observed that the maximum productivity obtained was 98.23 mmol H2/L days in 26 h of process.

Keywords: Hydrogen, Milk whey permeate, Photo-fermentation, Rhodobacter capsulatus

Introduction

The environment impacts and the repercussions concerning on the global climate changes are caused by emissions of greenhouse gases originated from limited fossil resources. Therefore, the search for alternative fuels of clean energy should be developed (Wu et al. 2012). Hydrogen is a source of potentially renewable energy with high energetic content (142 MJ/kg) in relation to others like natural gas (28 MJ/kg) and it does not emit pollutants to the atmosphere (Avcioglu et al. 2011).

Nowadays, the major proportion of hydrogen production is derived from fossil resources using steam reforming of natural gas, partial oxidation of heavy hydrocarbons, coal gasification and, in minor proportion, by electrochemical process (electrolysis of water). In general, these processes are expensive or require high energy demand. Nevertheless, hydrogen might be also produced by biological and sustainable technology that reduces the impacts to the environment; presents high purity, high theoretical yield and low energetic expenditure. In addition, it offers the possibility to use organic residues as substrate (Bianchi et al. 2010).

The biological route can be classified into three metabolic pathways related to cellular metabolism, that are, biophotolysis of water by algae or cyanobacteria, offering as advantages the use of water and CO2 as an abundant substrate and the formation of H2; dark fermentation from anaerobic digestion of organic matter and the photo-fermentation that is an anoxygenic photosynthesis by purple non-sulfur bacteria (PNS) that also degrade organic compounds (Das and Veziroglu 2008; Hallenbeck and Ghosh 2009). These processes have been largely studied in several investigations that focus in maximize the efficiency of H2 production. In addition, there are still hybrid systems assembled by the combination of two or more types of biological routes. Among the hybrid systems, the coupled system of dark fermentation in a first stage followed by photo-fermentation has been the most studied since this type of process increases the total yields due to the higher conversion of the substrates into the target product (Neves 2009).

In respect to the photo-fermentation, it should be highlighted that purple non-sulfur bacteria (PNS) bacteria are well known for their capacity of producing hydrogen from organic compounds (carbohydrates and organic acids), using light for energy and cultivated in photoheterotrophic conditions under limitation of ammonium nitrogen since it inhibits nitrogenase enzyme that catalyzes hydrogen formation (Özgür et al. 2010a; Urbaniec and Grabarczyk 2014). According to Özgür et al. (2010a), hydrogen was not produced in dark fermentation effluent with concentrations of ammonium superior to 2 mM. Organic acids, among them, acetic, lactic, butyric and propionic acids have been widely used as substrates in photo-fermentation (Oliveira et al. 2014; Lazaro et al. 2015). The use of this variety of compounds proves that PNS bacteria can be applied for wastewater treatment and as a second stage for a hybrid system after dark fermentation (Uyar et al. 2009).

Shi and Yu (2006) studied the production of hydrogen by Rhodopseudomonas capsulatus using acetate, propionate and butyrate as substrates. The best results were attained when acetic acid was used as isolated (yield of 0.65 mol H2/mol acetate) or as a mixture of acetic (1.9 g/L), propionic (0.4 g/L) and butyric (0.8 g/L) acids (yield of 0.34).

Wastewater of tofu factory was used as substrate by Rhodobacter sphaeroides immobilized in agar gels (Zhu et al. 1999). In this work, the maximum rate of hydrogen production using the wastewater was slightly higher than the production when glucose was the carbon source and the removal of total organic carbon (TOC) was 41% and similar to the process with glucose as substrate.

Besides wastewater, dark fermentation effluents, rich in carbon source, also can be used (Keskin and Hallenbeck 2012; Afsar et al. 2011; Silva et al. 2016; Tian et al. 2010). In dark fermentation, the yield is generally 33% and several organic acids are produced such as acetate, propionate and butyrate, formate, lactate, valerate, and caproate. Conversion of these compounds by PNS bacteria, either in a two-step or in a co-culturing process, is an alternative to increase the yield from 4 mol H2/mol of hexose to 12 mol of H2/mole of hexose. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the metabolic pathways of PNS bacteria for hydrogen evolution may differ between strains of the same species and the composition of the medium (Avcioglu et al. 2011; Özgür et al. 2010a; Shi and Yu 2006; Abo-Hashesh et al. 2013).

A two-step process using molasses as substrate was investigated by Avcioglu et al. (2011), with dark fermentation by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and photo-fermentation by Rhodobacter capsulatus wild type (DSM 1710) and Rhodobacter capsulatus hup− (YO3). The maximum hydrogen yield obtained was using R. capsulatus hup−was 78% (of the theoretical maximum) and the maximum hydrogen productivity was 16 mmol H2/L days.

Tao et al. (2007) also evaluated hybrid system using mixed culture in dark fermentation of sucrose and photo-fermentation by R. sphaeroides SH2C. The metabolites produced in the first stage were mainly butyrate and acetate and small proportion of propionate, valerate, n-butyl alcohol, and caproate. These authors described that butyrate, acetate, propionate and valerate were totally converted during photofermentation and the total hydrogen yield was 6.63 molH2/mol sucrose.

Direct conversion of sugar was reported by Abo-Hashesh et al. (2013) and Keskin and Hallenbeck (2012). The results by Abo-Hashesh et al. (2013) were superior to the hybrid system, with the highest hydrogen yield, 9.0 mol H2/ mol glucose in the continuous mode (HRT of 48 h) by Rhodobacter capsulatus JP91 (hup−). Keskin and Hallenbeck (2012) used beet molasses, black strap and sucrose and the results of yield were 10.5 mol H2/mol sucrose; 8 mol H2/mol sucrose and 14 mol H2/mol sucrose, respectively, for 1 g/L as initial concentration of sugar. In this context, the aim of the current work was to evaluate the hydrogen production by photo-fermentation using the PNS bacteria, Rhodobacter capsulatus, and applying as substrate the effluent of dark fermentation of milk whey permeate (MWP). Two different scales (50 mL and 1.5 L) were compared, and the work focused on the effect of the culture medium composition, approaching the addition of lactose from MWP and type and concentration of organic acids produced during dark fermentation, in hydrogen formation by photo-fermentation.

The choice of the supplementation of the photo-fermentation medium with MWP is due to it is widely produced as by-product of dairy industry. In MWP, lactose represent the main fraction (90%) of the organic load. In addition, it presents also fat and protein in its composition. Milk whey is suitable to be treated by biological processes (Prazeres et al. 2012) and MWP is an alternative product that can be reused in food industry that is resulting from the precipitation and removal of milk casein in cheese-manufacturing process (Cuartas-Uribe et al. 2009). Milk whey has been studied as substrate in dark fermentation, but is not yet explored for photo-fermentation (Davila-Vazquez et al. 2009; Ferchichi et al. 2005; Kargi et al. 2012).

Materials and methods

Inoculum preparation and culture medium

Rhodobacter capsulatus (PNS) SB 1003 purchased from DSMZ bank (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Culture) was maintained in RCV medium (Weaver et al. 1975) prior to photo-fermentation assays. In RCV medium, the carbon source is malic acid (4.02 g/L) and the nitrogen source is ammonium sulfate (1 g/L). The first step was carried out in an up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor (UASB) using mixed anaerobic culture growing in a synthetic medium consisting of the following compounds (in g/L): lactose (20), yeast extract (3), meat extract (0.5), KH2PO4 (3), K2HPO4 (7), (NH4)2SO4 (1), FeSO4 (1) and MgSO4 (3). The second stage was carried out in batch reactors using as substrate the dark fermentative effluent after pre-treatments (centrifugation, supplementation, sterilization). Lactose was obtained from milk whey permeate, which was purchased from the Sooro Concentrado Industria de Produtos Lacteos Ltda (Brazil) (Romão et al. 2014).

Initially, the effluent from the dark fermentation (organic acids enriched) was centrifuged (10 min at 7730 g) and supplemented with components of the RCV medium in g/L: KH2PO4 (0.6 g/L), K2HPO4 (0.9 g/L), MgSO4⋅7H2O (0.12 g/L), CaCl2⋅2H2O (0.075 g/L), Na2EDTA⋅2H2O (0.02 g/L), micronutrients (1 mL) and thiamine (0.001 g/L), as proposed by Weaver et al. (1975). It should be noted that ammonium sulfate and malic acid, commonly found in the RCV medium, were not added. Dark fermentation effluent contains ammonium and the addition of extra ammonium could inhibit nitrogenase, and as the medium presented a variety of organic acids, the addition of malate was avoided. Before inoculation, this effluent was sterilized by autoclaving for the microbial inactivation and to remove colloidal materials that might interfere in the light penetration into the bioreactor (Özgür et al. 2010a). Finally, after cooling, it was inoculated with R. capsulatus.

The influence of lactose as carbon source in photo-fermentation was also evaluated. It is important to note that the lactose used in a 50-mL bioreactor was from milk whey permeate (MWP) while the analytical grade lactose (Dinamica Chemical Contemporary) was used in 1.5-L bioreactor assays. In this work, MWP was used to maintain the same composition of the substrate in all assays since the composition of milk whey in nature obtained from local dairy industry may differ from the production batch. In the current work, the analytical grade lactose and lactose from milk permeate lactose (MWP) were used as supplements in bacteria culture media. The objective was to observe the influence of an isolated component (lactose), as well as complex component (MWP) containing lactose on the hydrogen production by PNS bacterium. MWP is rich in several nutrients potentially useful for PNS bacteria. In addition, the use of MWP adds value to industrial waste.

Effect of the composition of dark fermentation effluent on hydrogen production by R. capsulatus

Initially, the experiments were carried out in 50-mL bioreactors with working volume of 37.5 mL, and incubated at 32 ± 1 °C under light intensity of 30 µmol photons/m2/s fluorescent lamps. After inoculation, the bioreactor was purged with argon gas for 3 min to ensure an anaerobic environment. Then it was sealed with a butyl rubber septum and aluminum seal. The biogas was collected after 5 days in 10-mL syringes previously coupled to the system. The vials were prepared in duplicate. The samples were stored in Gasometric ampoules (Construmaq LTDA, Brazil) for analysis of its composition by gas chromatography. In addition, to measure sugar, organic acid and ethanol concentrations, 10 mL of the cell suspension culture was collected and centrifuged (15 min at 7730 g) and the supernatant was analyzed by HPLC. The aim of the first assays (from 1 to 4) was to verify the influence of content of residual lactose and lactic acid which was an organic acid with the highest concentration in dark fermentation effluent, in the hydrogen production by R. capsulatus (Table 1). In these assays, the effect of MWP addition was also investigated by adjusting the C/N ratio to 35:1 and 70:1. After that, supplementary analyses (assays from 5 to 16) were performed to better understand the behavior of photo-fermentation concerning the composition of dark fermentation effluent. The C/N ratio varied according to the lactose concentration. The C/N ratio was monitored by TOC analysis and then, if necessary, lactose (C source) and ammonium sulfate (N source) were added.

Table 1.

Different compositions of a carbon source in photo-fermentation assays by R. capsulatus

| Fermentation medium | Lactose (g/L) | Lactic acid (g/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Assay 1 | 5.5 | 0.58 |

| Assay 2 | 5.1 | 12.3 |

| Assay 3 | 0.7 | 8.83 |

| Assay 4 | 9.1 | 8.80 |

| Assay 5 | 3.0 | 11.00 |

| Assay 6 | 4.3 | 11.76 |

| Assay 7 | 6.7 | 4.59 |

| Assay 8 | 2.27 | 11.67 |

| Assay 9 | 5.44 | 13.77 |

| Assay 10 | 8.70 | 10.89 |

| Assay 11 | 9.50 | 10.67 |

| Assay 12 | 10.14 | 0.10 |

| Assay 13 | 6.43 | 12.91 |

| Assay 14 | 7.96 | 14.25 |

| Assay 15 | 0.00 | 19.32 |

| Assay 16 | 0.00 | 18.27 |

Evaluation of hydrogen production with time in a 1.5-L photobioreactor

The luminous intensity can greatly affect the productivity of photo-fermentation so that the amount and distribution of light homogeneous during the fermentation is very important. Besides, the production of hydrogen might be considerably improved in an amplified scale under controlled conditions of temperature, agitation, light intensity and pH. Thus, in the following stage of this work, experiments were also carried out in a 1.5-L bioreactor, working volume of 700 mL, at 32 ± 1 °C, 130 rpm and light intensity of 70 µmol photons/m2/s. It is important to note that the initial lactose concentration was adjusted to 10 g/L, according to previous results obtained in a 50-mL bioreactor. After inoculation, the argon gas was bubbled into the system for 15 min to ensure an anaerobic environment. The volume of biogas produced was measured by a volumetric flow meter MilliGas-Counter of Ritter Type MGC-1. Samples of the reaction broth were periodically collected and centrifuged for 15 min at 7730g to measure cell density, besides lactose, organic acid and ethanol concentrations. The composition of the biogas was also determined during the photo-fermentation assay.

Analytical methods

The cell density (gvs/L) was determined by spectrophotometry and the optical density at 660 nm was converted to gvs/L by predetermined correlation equation between OD660 and grams of volatile solids per liter (Clesceri et al. 1998).

The biogas composition was determined by gas chromatography using the chromatograph Shimadzu model GC 17A equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a capillary column Carboxen 1010 (length 30 m; internal diameter 0.53 mm). The operating temperatures of the injection port, the oven and the detector were 230, 30 and 230 °C, respectively. Argon was used as carrier gas.

The concentration of total carbon and nitrogen organic was evaluated using the TOC-L Carbon Analyzer CSH, Shimadzu, operated at 680 °C using platinum supported on alumina.

Concentration of lactose, ethanol and organic acids were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The sample standard deviation was ± 0.08 (g/L) for the concentration of organic acids, ethanol and sugars. Samples were diluted with ultrapure water filtered through a membrane (0.22 µm pore size; Millipore) and injected into a chromatographic system (Shimadzu model LC-20A Prominence Supelcogel C-610H column) equipped with ultraviolet–visible and refractive index detectors. The former was used to measure organic acids at a wavelength of 210 nm and the latter quantified lactose and ethanol. Analyses were carried out using phosphoric acid 0.1% as carrier solution pump flow rate at 0.5 mL/min temperature oven at 32 °C. The sample volume injected into the chromatograph was 20 µL. The response monitored was hydrogen productivity (mmol H2/L day) obtained in accordance with the following equation:

| 1 |

Results and discussion

Effect of the composition of dark fermentation effluent on hydrogen production by R. capsulatus

This section reports results observed from photo-fermentation assays by Rhodobacter capsulatus using a 50-mL bioreactor. In general, the substrate for photo-fermentation was the effluent from dark fermentation by mixed culture using lactose from MWP as the carbon source. It is important to note that the influence of effluent composition in terms of lactose and lactic acid, that was the metabolite in the highest concentration in the effluent, was analyzed. Besides that, in assay from 1 to 4, the influence of the substrate with MWP (86 to 92% of lactose) was tested (Table 2).

Table 2.

Volumetric hydrogen productivity in the R. capsulatus photo-fermentation using a 50-mL bioreactor

| Assay | C lactosea (g/L)a | C lactic acida (g/L)a | C/Nb | Productivity (mmol H2/L day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.50 | 0.58 | Without MWPc | 8.00 ± 1.40 |

| 35:1 | 9.62 ± 2.42 | |||

| 70:1 | 4.74 ± 1.35 | |||

| 2 | 5.10 | 12.30 | Without MWP | 10.16 ± 1.84 |

| 35:1 | 6.94 ± 4.66 | |||

| 70:1 | 11.24 ± 6.34 | |||

| 3 | 0.70 | 8.83 | Without MWP | 0.44 ± 0.32 |

| 35:1 | 4.67 ± 0.07 | |||

| 70:1 | 8.66 ± 9.14 | |||

| 4 | 9.10 | 8.80 | Without MWP | 14.33 ± 9.78 |

| 35:1 | 11.43 ± 0.28 | |||

| 70:1 | 8.93 ± 2.60 |

aInitial concentration

bCorrelation of carbon and nitrogen (based on the MWP)

cMWP: milk whey permeate (from 86 to 92 % of lactose)

By analysis of Table 2, assays 1–4, the highest productivity (14.33 mmol H2/L day) was obtained in experiment 4. In this case, the effluent from dark fermentation contained residual lactose and lactic acid above 9.1 g/L and 8.8 g/L, respectively. Analyzing the results of the assays without supplementation of MWP, it is possible to observe that, fixing the initial concentration of lactose of around 5.5 g/L and increasing lactic acid (assays 1 and 2), the hydrogen synthesis increased 27%. Using a dark effluent with higher initial concentration of both lactose and lactic acid corresponded to 79% (assays 1 and 4) and 41% (assays 2 and 4). Experiment 3, with neglected residual lactose in dark effluent and 8.83 g/L of lactic acid, did not result in hydrogen production. In this case, the supplementation of MWP (35:1 and 70:1 of C/N ratios) promoted improvements in hydrogen formation. These results indicate that the addition of lactose in the dark effluent by mixed consortium fermentation can enhance hydrogen productivity.

In respect to test C/N ratios of 35:1 and 70:1, for all assays, it was verified that MWP addition did not result in increasing productivity, by comparing the formation of H2 with the assays without addition of MWP. Except for the assay in the absence of lactose (assay 3) in the dark effluent, the productivity is slightly higher or even lower. The influence of increasing C/N ratio by the addition of MWP was not clear since in experiments 1 and 4, the increase of C/N ratio promoted a decrease in H2 productivity. In assay 3, in which lactic acid initial concentration was higher than initial lactose content, hydrogen formation decreased by increasing the C/N ratio to 35:1 and increased when C/N ratio was even higher (70:1). It is important to remind that MWP contains lactose and, in smaller percentage, protein, fat and other nutrients that may have influenced hydrogen synthesis. Nevertheless, understanding how the composition of MWP affects R. capsulatus metabolism needs an in-depth study and it was not within the scope of this work.

Thereafter, further experiments, from 5 to 11 (Table 3), were carried out using the substrate without the addition of MWP. The highest volumetric hydrogen productivity (20.34 mmol H2/L day) was attained in experiment 7, in which the initial concentrations of lactose and lactic acid of 6.7 and 4.59 g/L, respectively, were used. Furthermore, it is noted that the volumetric hydrogen productivity in the photo-fermentation by PNS bacteria was strongly affected by the bacterial metabolism as can be seen by different organic acid (lactic, acetic, butyric and propionic acids) production profiles. Surprisingly, increases in both carbon sources, as in experiments 10 and 11, did not result in increments on the productivity. Besides that, the bottle browning was verified for the fifth and eighth conditions, probably, due to iron precipitation or formation of sulfide compounds according to the literature. Therefore, concentration of dissolved iron was analyzed to determine if the browning was caused by iron oxidation. Nevertheless, the results did not allow concluding the relation between the dissolved iron concentration, hydrogen production and the browning of the medium during photofermentation. As discussed by Eroglu et al. (2011), browning was also observed after the addition of Fe2+ to the culture medium. Moreover, Zhu et al. (2007) commented that iron coagulation had a negative effect on hydrogen production since the iron precipitates on the surface of the cells. A lower initial concentration of lactose and the precipitation of iron can explain the neglected production of hydrogen in these assays. In addition, iron–sulfur cluster can be observed.

Table 3.

Volumetric hydrogen productivity and organic acid evolution in the R. capsulatus photo-fermentation using a 50-mL bioreactor

| Assay | Clactose(1) (g/L) | Clactic acid (1) (g/L) | Productivity (mmol H2/L day) | Lactic (%) | Acetic (%) | Butyric (%) | Propionic (%) | Lactic + butyric (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 3 | 11.00 | 0.94 ± 0.19 | 17.03 | 35.86 | 18.01 | 29.10 | 35.03 |

| 6 | 4.3 | 11.76 | 11.67 ± 3.23 | 18.90 | 22.06 | 43.02 | 16.01 | 61.93 |

| 7 | 6.7 | 4.59 | 20.34 ± 2.85 | 63.63 | 14.95 | 18.55 | 2.87 | 82.18 |

| 8a | 2.27 | 11.67 | 3.83 ± 1.00 | 14.68 | 30.79 | 22.21 | 32.03 | 36.89 |

| 9 | 5.44 | 13.77 | 15.63 ± 4.15 | 60.01 | 7.48 | 26.65 | 3.82 | 86.66 |

| 10 | 8.7 | 10.89 | 15.55 ± 0.28 | 70.53 | 11.81 | 15.52 | 2.15 | 86.05 |

| 11 | 9.5 | 10.67 | 14.89 ± 2.76 | 66.21 | 9.98 | 22.18 | 1.63 | 88.39 |

aBottle browning was observed

The differences in the magnitudes of volumetric hydrogen productivity may be assigned to the influence of organic acid (lactic, acetic, propionic, butyric and formic) concentrations on the substrate. It should be emphasized that these compounds may be varied depending on the dark fermentation conditions. Therefore, to get a better comprehension of the influence of the effluent composition from the dark fermentation on the photo-fermentation, the initial concentrations of other organic acids were evaluated as well (assays 12–16). Table 4 summarizes the findings. The experiments from 12 to 16 (Table 4) indicated that lactose is an essential carbon source for hydrogen-producing PNS bacterium; once in experiments 15 and 16, without lactose, the strain presented a negligible volumetric hydrogen productivity (0.37 and 0.48 mmol H2/L day), even with a high initial lactic acid concentration, 19.32 and 18.27 g/L, respectively. The same result was observed in assay 3 with initial concentration of 0.70 g/L of lactose and 8.83 g/L of lactic acid and in assays 5 and 8 with initial concentration of lactose around 3 g/L and of lactic acid around 11 g/L.

Table 4.

Volumetric hydrogen productivity and the evolution of metabolic compounds in photo-fermentation using a 50-mL bioreactor

| Assay | Ci.lact (g/L) | Vbiogas (mL) | Productivity (mmol H2/L day) | Ci.lac (g/L) | Cf.lac (g/L) | Ci.acet (g/L) | Cf.acet (g/L) | Ci.prop (g/L) | Cf.prop (g/L) | Ci.but (g/L) | Cf.but (g/L) | Ci.form (g/L) | Cf.form (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 10.14 | 77.67 | 17.12 ± 0.99 | 0.10 | 6.18 | 1.59 | 2.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 2.44 | 3.97 | 0.84 | 0.55 |

| 13 | 6.43 | 98.33 | 37.23 ± 3.08 | 12.91 | 11.46 | 1.46 | 1.55 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 1.69 | 4.92 | 0.39 | 0.47 |

| 14 | 7.96 | 100.00 | 31.57 ± 4.88 | 14.25 | 11.69 | 1.31 | 0.97 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 4.78 | 0.49 | 0.35 |

| 15a | 0.00 | 23.00 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 19.32 | 6.27 | 2.27 | 5.28 | 0.31 | 4.44 | 0.21 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| 16a | 0.00 | 21.33 | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 18.27 | 1.67 | 3.01 | 6.06 | 0.26 | 5.21 | 0.00 | 1.20 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

i initial, f final, lact lactose, lac lactic acid, acet acetic acid, prop propionic acid, but butyric acid, form formic acid

aBottle browning was observed

Table 4 also reports that, in the lack of lactose, lactic acid was consumed mainly for the acetic and propionic acid production (assays 15 and 16). In experiments 13 and 14, in which the initial lactose concentration was around 7 g/L, the lactic acid was slightly consumed and from the formed acids, a greater variation was established in the content of butyric acid. Complementarily, in experiments 13 and 14, an increase of cell density to about 2-fold and 3.4-fold, respectively, was verified once the initial cell density was 0.58 g/L. Besides that, as seen in experiments from 7 to 11 (Table 3), assays from 12 to 16 (Table 4) indicated that increases in the initial lactose concentration above 6.43 g/L (assay 13) did not result in increments in the hydrogen production, with 37.23 mmol H2/L day being the maximum H2 productivity. In addition, in most of the cases where higher hydrogen productivity was observed (7, 13 and 14). the initial lactose concentration was between 6 and 9 g/L.

Evaluation of hydrogen production with time in 1.5-L photobioreactors

The H2 evolution was also carried out in a 1.5-L bioreactor to verify the productivity and the time of fermentation on the target-product synthesis. The characterization of the substrate showed that the composition of the dark fermentation effluent was in g/L: 0 of lactose, 12.54 of lactic acid, 0.32 formic acid, 1.20 acetic acid, 0.82 butyric acid and 0.79 of propionic acid and the C/N ratio was 11.29 (mg/mg). Based on previous results (assays 1–16), to increase the hydrogen production by R. capsulatus, the initial lactose concentration in the dark fermentation effluent was adjusted to 10 g/L. This assay was performed at 32 ± 1 °C with initial cell concentration of 0.49 g/L.

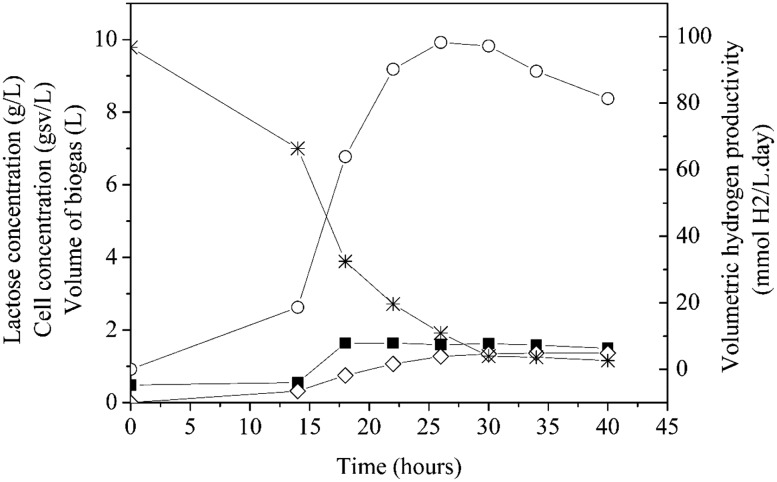

The results of cell concentration, biogas volume, volumetric hydrogen productivity and the concentration of consumed lactose during this photo-fermentation experiment are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Profile of cell concentration (filled square), biogas volume (open diamond), volumetric hydrogen productivity (open circle) and lactose concentration (asterisk) during the photo-fermentation assay by R. capsulatus. The initial lactose concentration was 10 g/L and the temperature was 32 ± 1 °C

In this assay, the amount of accumulated hydrogen achieved 0.08 mol after 40 h of photo-fermentation by R. capsulatus. Within this time, the maximum volumetric hydrogen productivity was 98.23 mmol H2/L day attained in 26 h of process. At the end of 40 h, the productivity decreased 17% to 81.36 mmol H2/L day. It should be emphasized that this result is about twofold higher than the productivity of experiment 13 (50 mL bioreactor). In respect to growth of cells, it can be observed that the highest cell concentration (1.64 gvs/L) was obtained in 18 h and remained constant until the end of the assay. Maximum production of biogas (1.36 L) was verified in 30 h and, similar to accumulate hydrogen, it was constant after this time. The lactose consumption was 88.16%, that is, the lactose concentration decreased from 9.78 to 1.16 g/L in 40 h of the process. Figure 2 illustrates the behavior of metabolite concentrations during the photo-fermentation assay by R. capsulatus.

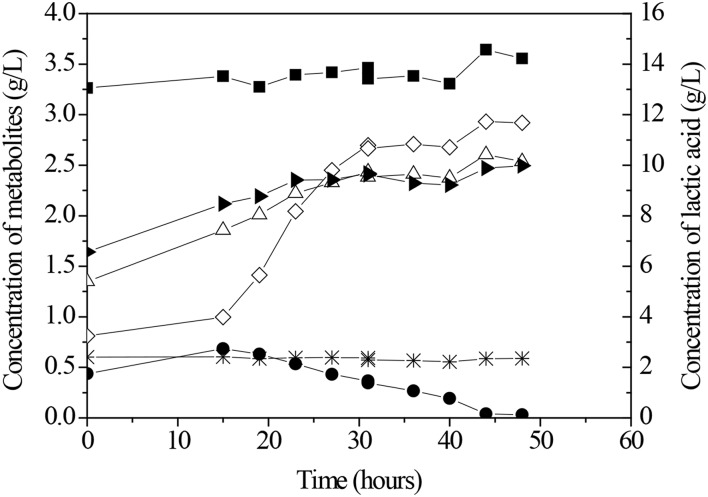

Fig. 2.

Concentration profiles of formic acid (filled circle), ethanol (right angle triangle), acetic acid (triangle), propionic acid (asterisk), butyric acid (open diamond) and lactic acid (filled square) during the photo-fermentation assay by R. capsulatus. The initial lactose concentration was 10 g/L and the temperature was 32 ± 1 °C

It can be noted that the concentrations of lactic acid, propionic acid and ethanol within 40 h of the process were around 12.54 ± 0.5 g/L, 0.79 g/L and 1.47 ± 0.10 g/L, respectively. In relation to further organic acids, an increase in their concentrations was observed. The concentration of formic acid increased 2.6-fold, from 0.32 to 0.83 g/L in 18 h. The synthesis of acetic acid raised its concentration twice, from 1.20 to 2.39 g/L. Butyric acid was produced in higher amounts. There was incremented of fivefold, in which its concentration varied from 0.82 to 4.09 g/L.

These data of metabolites evolution followed the same trend verified in the experiments carried out in 50-mL bioreactors. The sum of the percentage of lactic acid and butyric acid concentrations was superior to 80%. Although the lactic acid concentration was high, it was not consumed by cells.

It was observed that the C/N ratio was constant during the photo-fermentation process (40 h) around of 17 mg/mg. This result indicates that there was a conversion of lactose in other complex metabolites (ethanol and organic acids) which agrees with the metabolite profiles presented in Fig. 2 and the low fraction of CO2 is detected in the biogas (10–15%).

This current study proved that the hybrid system is a promising alternative to produce hydrogen and better results are attained when the dark fermentation effluent is supplemented with a sugar as a carbon source, like in the particular study, lactose.

Based on the small-scale experiments, large scale produced the better results. So, hydrogen yield was much higher even by the improvement of the experimental apparatus, with higher reaction volume and light intensity and agitation.

It is important to note that by comparing the results of this current work with those reported in the literature, the production of hydrogen was higher, even in reduced scale of 50 mL. According to Özgür et al. (2010b), a volumetric hydrogen productivity of 16.16 mmol H2/L day was obtained using R. capsulatus at a C/N ratio of 35. They evaluated the effect of acetate concentration in H2 production and cell growth, by varying the initial concentration of acetic acid from 10 to 50 mM with a fixed concentration of sodium glutamate (2 mM). These authors obtained C/N ratios from 15 to 55. Their results showed that cell growth and H2 production were successful in all evaluated acetate concentrations. Nevertheless, the hydrogen production started sooner at lower acetic acid concentrations.

In the work developed by Avcioglu et al. (2011), the hybrid system to hydrogen production was investigated by applying dark fermentation effluent of beet molasses in the first stage, followed by photo-fermentation by R. capsulatus in a photobioreactor. This strategy resulted in maximum productivity of 12.0 mmol H2/L day and a yield of 0.50 mol H2/mol of consumed substrate.

Tests were performed according to Afsar et al. (2011) to study the production of hydrogen by R. palustris and R. capsulatus utilizing dark fermentation effluent containing acetate (114 mM), lactic acid (6 mM), glucose (20 mM) and NH4Cl (1 mM), after diluting three times. Their productivity was 10.32 mmol H2/L day and 7.92 mmol H2/L day for R. capsulatus and R. palustris, respectively.

Concerning the use of sugar as carbon source, similar to this present work, Abo-Hashesh et al. (2013), who used glucose as a substrate in a single-stage photo-fermentation to produce hydrogen, reported to find a production rate twice the productivity obtained from organic acid. Keskin and Hallenbeck (2012), who studied the production of hydrogen by one-stage photo-fermentation processes from black strap and beet molasses, also presented promising results and concluded that photo-fermentation is an attractive system that can even be applied as single stage to direct conversion of sugar to hydrogen.

Conclusion

In this study, the maximum volumetric hydrogen productivity was 98.23 mmol H2/L day after 26 h, in which the culture medium contained 12.54 g/L of lactic acid, 0.32 g/L of formic acid, 1.20 g/L of acetic acid, 0.82 g/L of butyric acid and 0.79 g/L of propionic acid and lactose initially adjusted to 10 g/L. The results also confirm that there is a need to provide a sugar source for hydrogen production because in its absence the target product was negligible. Therefore, this study highlights the use of industrial effluent as an alternate to hydrogen production by different biological routes.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from FAPEMIG, CNPq, CAPES and Vale S.A.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abo-Hashesh M, Desaunay N, Hallenbeck PC. High yield single stage conversion of glucose to hydrogen by photo-fermentation with continuous cultures of Rhodobacter capsulatus JP91. Biores Technol. 2013;128:513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afsar N, Özgür E, Gürgan M, Akköse S, Yücel M, Gündüz U, Eroglu I. Hydrogen productivity of photosynthetic bacteria on dark fermenter effluent of potato steam peels hydrolysate. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2011;36:432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Avcioglu SG, Ozgur E, Eroglu I, Yucel M, Gunduz U. Biohydrogen production in an outdoor panel photobioreactor on dark fermentation effluent of molasses. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2011;36:11360–11368. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi L, Mannelli F, Viti C, Adessi A, De Philippis R. Hydrogen-producing purple non-sulfur bacteria isolated from the trophic lake Averno (Naples, Italy) Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010;35:12216–12223. [Google Scholar]

- Clesceri L, Eaton AD, Greenberg AE. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 20. Washington: American Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cuartas-Uribe B, Alcaina-Miranda MI, Soriano-Costa E, Mendoza-Roca JA, Iborra-Clar MI, Lora-García J. A study of the separation of lactose from whey ultrafiltration permeate using nanofiltration. Desalination. 2009;241:244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Das D, Veziroglu TN. Advances in biological hydrogen production processes. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2008;33:6046–6057. [Google Scholar]

- Davila-Vazquez G, Cota-Navarro CB, Rosales-Colunga LM, de León-Rodríguez A, Razo-Flores E. Continuous biohydrogen production using cheese whey: improving the hydrogen production rate. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:4296–4304. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu E, Gunduz U, Yucel M, Eroglu I. Effect of iron and molybdenum addition on photofermentative hydrogen production from olive mill wastewater. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2001;36:5895–5903. [Google Scholar]

- Ferchichi ME, Crabbe ME, Gil G-H, Hintz W, Almadidy A. Influence of initial pH on hydrogen production from cheese whey. J Biotechnol. 2005;120:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck PC, Ghosh D. Advances in fermentative biohydrogen production: the way forward? Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargi F, Eren NS, Ozmihci S. Hydrogen gas production from cheese whey powder (CWP) solution by thermophilic dark fermentation. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2012;37:2260–2266. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskin T, Hallenbeck PC. Hydrogen production from sugar industry wastes using single-stage photo-fermentation. Biores Technol. 2012;112:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro CZ, Bosio M, dos Ferreira S, Varesche J, Silva MBA. The biological hydrogen production potential of agroindustrial residues. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2015;6:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Neves LMV (2009) Bio-hydrogen production by bacteria from fermentable waste. Dissertation presented at the Faculty of Science and Technology of the New University of Lisbon to obtain a Master ‘s Degree in Chemical Engineering and Biochemistry

- Oliveira TV, Bessa LO, Oliveira FS, Ferreira JS, Batista FRX, Cardoso VL. Insights Into the effect of carbon and nitrogen source on hydrogen production by photosynthetic bacteria. Chem Eng Trans. 2014;38:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Özgür E, Afsar N, de Vrije T, Yücel M, Gündüz U, Claassen PAM, Eroglu I. Potential use of thermophilic dark fermentation effluents in photofermentative hydrogen production by Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Clean Prod. 2010;18:S23–S28. [Google Scholar]

- Özgür E, Uyar B, Öztürk Y, Yücel M, Gündüz U, Eroğlu I. Biohydrogen production by Rhodobacter capsulatus on acetate at fluctuating temperatures. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2010;54:310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Prazeres AR, Carvalho F, Rivas J. Cheese whey management: a review. J Environ Manag. 2012;110:48–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romão BB, Batista FRX, Ferreira JS, Costa HCB, Resende MM, Cardoso VL. Biohydrogen production through dark fermentation by a microbial consortium using whey permeate as substrate. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:3670–3685. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-0778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi XY, Yu HQ. Conversion of individual and mixed volatile fatty acids to hydrogen by Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2006;58:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Silva FTM, Moreira LR, Ferreira JS, Batista FRX, Cardoso VL. Replacement of sugars to hydrogen production by Rhodobacter capsulatus using dark fermentation effluent as substrate. Biores Technol. 2016;200:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Chen Y, Wu Y, He Y, Zhou Z. High hydrogen yield from a two-step process of dark- and photo-fermentation of sucrose. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2007;32:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Liao Q, Zhu X, Wang Y, Zhang P, Li J, Wang H. Characteristics of a biofilm photobioreactor as applied to photo-hydrogen production. Biores Technol. 2010;101:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniec K, Grabarczyk R. Hydrogen production from sugar beet molasses—a techno-economic study. J Clean Prod. 2014;65:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Uyar B, Eroglu I, Yücel M, Gündüz U. Photofermentative hydrogen production from volatile fatty acids present in dark fermentation effluents. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:4517–4523. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver PF, Wall JD, Gest H. Characterization of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Arch Microbiol. 1975;105:207–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00447139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TY, Hay JXW, Kong LB, Juan JC, Jahim JM. Recent advances in reuse of waste material as substrate to produce biohydrogen by purple non-sulfur (PNS) bacteria. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2012;16:3117–3122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Suzuki T, Tsygankov AA, Asada Y, Miyake J. Hydrogen production from tofu wastewater by Rhodobacter sphaeroides immobilized in agar gels. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 1999;24:305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Fang HHP, Zhang T, Beaudette LA. Effect of ferrous ion on photoheterotrophic hydrogen production by Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2007;32:4112–4118. [Google Scholar]