Introduction

In addition to counseling and educating patients, genetic counselors are critical in teaching genetic concepts and counseling techniques to genetic counseling students, both as faculty within accredited programs or as supervisors of new graduates during the initial on-the-job training. The majority of counselors surveyed by the National Society of Genetic Counselors (72%) reported involvement in teaching and other education activities (NSGC 2016). Moreover, the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) included “Education” as one of the four core domains for the genetic counseling profession (ACGC 2013; Doyle et al. 2016). These four core domains help to categorize the 22 practice-based competencies (PBC) that genetic counselors should master to successfully practice, and to inform genetic counseling training (ACGC 2013). PBC#16 (III Domain) specifically addresses the genetic counselors’ educational role, which include goals assessment, curriculum development, and the use of feedback, and it is distinct from clinical supervision (PBC#21in IV Domain) (ACGC 2013; Doyle et al. 2016). Although their role supervising students in clinical settings (clinical supervision) has been explored (Atzinger et al. 2014; Finley et al. 2016; Atzinger et al. 2016), no research is available on the experience of genetic counselors in their role as teachers, the resources used to prepare for this role, or the tools used to give and receive feedback.

Srinivasan et al. (2011) built the “Teaching as a Competency” framework utilizing a variety of methods, which included review of teaching literature, a 2-day medical educator conference focusing on educational competencies, and presentations at regional and national meetings. This conceptual model for medical educators utilizes the six core physician competencies initially developed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to evaluate trainees in medical education programs (Srinavasan et al. 2011; Joyner 2004; Swing 2007; ACGME 2016). The ACGME competencies were modified to identify the skills critical for medical education: (1) medical (or content) knowledge, (2) learner-centeredness, (3) interpersonal and communication skills, (4) professionalism and role modeling, (5) practice-based reflection, and (6) systems-based practice. This framework aims to enhance teaching quality and promote dialog about medical educator training, development, and outcomes. Recently, this framework has been further evaluated by Brink et al. (2018) using a modified Delphi process.

Data directly evaluating genetic counselors’ teaching is difficult to obtain from direct observation, when considering the limited size of each program and the lack of formalized tools for gathering information. In the past, self-efficacy, the personal belief in one’s capability of performing a task, has been investigated as predictor of performance within the context of medical education, both assessing students’ academic performance (de Saintonge and Dunn 2001; Valentine et al. 2004; Gore 2006; Burgoon et al. 2012) and physicians’ teaching (Dybowski et al. 2016). Self-efficacy has been postulated to influence behavior and have predictive value on outcomes (Bandura 1995, 1997, 2006). Perceived self-efficacy is an important measure because it affects behavior and influences goals, perceived barriers, and outcome expectations, which remain important in teaching (Bandura 1997). Although self-perceived efficacy does not guarantee actual ability, Bandura’s framework has shown an association to positive classroom outcomes (Klassen and Tze 2014). Genetic counselors’ perceived self-efficacy has been evaluated in clinical supervision competencies, reporting generally high self-efficacy ratings for all the competencies explored (Finley et al. 2016). We have employed the framework presented by Srinivasan et al. (2011), modifying the competency wording to more closely align with teaching in the genetic counseling profession, and surveyed genetic counselors’ perceived self-efficacy in the following competencies: (a) content knowledge, (b) student centeredness, (c) interpersonal and communication skills, (d) role-modeling and professionalism, (e) ability to reflect and improve, and (f) ability to find and apply resources. To our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically investigates the perceived self-efficacy of genetic counselors in their role as teachers.

Methods

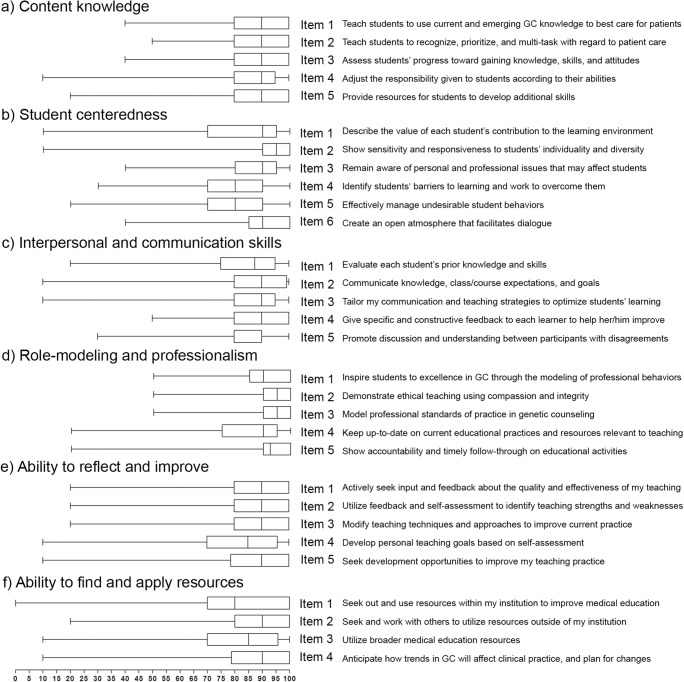

We constructed an on-line survey using REDCap. A collaborative consultation in survey design was provided by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center (SDBC). A pilot survey was sent to a small number of local genetic counselors for feedback, which led to minor revisions. Following approval by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah, a consent cover-letter with a link to the survey was sent to members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC; N = 3531) and the Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (CAGC; N = 319) by blast emails. A reminder email was sent 1 week following the initial invitation. The survey was closed after approximately 3 weeks from the first email. The targeted population was genetic counselors who “teach or co-teach the majority of one or more class sessions/lectures per academic year, not including clinical supervision,” as defined in the survey. The survey included four sections: (1) teaching self-efficacy measures for six competency content areas (30 items; Fig. 1); (2) impact of barriers to teaching (five items); (3) effectiveness of training and resources used by genetic counselors (19 items); and (4) demographic information, including teaching experience (17 items). A place for open-ended responses was provided at the end of each section. Self-efficacy scales were worded as “can do” statements, and varied from 0 (cannot do) to 100 (highly certain can do) in increments of 10 points (Bandura 2006). Can do statements are suggested instead of other wording like “will do” because can do is an indicator of capability rather than intention. To introduce the scale, participants were given a practice question where they were asked to rate their degree of confidence to lift weights ranging from 10 to 300 pounds.

Fig. 1.

Perceived self-efficacy in teaching tasks measured on a 0 to 100 scale. The survey items are shown next each boxplot. Boxplot indicates first to third quartile. Median is indicated with a line. Whiskers with end caps indicate minimum and maximum values

We also asked participants to report their perception of the impact of four major barriers to effective teaching: curricular barriers, reflecting issues with curricular objectives; cultural barriers, due to attitudes and traditions of students and faculty; environmental barriers, relating to physical setting and time available; and financial barriers, reflecting available resources (DaRosa et al. 2011). The impact was rated from 0 (no impact) to 4 (highly impactful). Additionally, we identified formal and informal training resources utilized to support teaching from a systematic review of the literature (Steinert et al. 2006; Atzinger et al. 2014; Finley et al. 2016) and authors’ feedback, and assessed respondents’ perception of their utilization and efficacy. Training and resources used to improve teaching were rated on effectiveness from 1 (not effective) to 4 (highly effective) or as “not done.” Demographic items explored genetic counseling and teaching experience (specified in number of years), and job setting, including teaching activities (pre-set categories were provided). The pre-set categories are listed in Tables 1 and 2 with the survey response received.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the respondents (n = 130)

| Variable | Our survey | PSS surveya | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 5 | 4 | 36 | 2 |

| 25–34 | 58 | 45 | 1092 | 49 |

| 35–44 | 36 | 28 | 690 | 31 |

| 45–54 | 15 | 12 | 250 | 12 |

| 55 - and above | 12 | 9 | 136 | 6 |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 | 3 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 123 | 95 | 2014 | 96 |

| Male | 4 | 3 | 89 | 4 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 3 | 2 | ||

| Country | ||||

| USA | 108 | 83 | 2078 | 94 |

| Canada | 22 | 17 | 113 | 5 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 14 | <1 |

| NSGC region | ||||

| Region I | 11 | 8 | 174 | 8 |

| Region II | 27 | 21 | 465 | 21 |

| Region III | 15 | 12 | 268 | 12 |

| Region IV | 35 | 27 | 601 | 27 |

| Region V | 21 | 16 | 289 | 13 |

| Region VI | 18 | 14 | 394 | 18 |

| Prefer not to specify | 3 | 2 | 14 | 1 |

| Primary place of practice | ||||

| Academic Institutionb | 88 | 68 | ||

| Public Medical Institution | 15 | 12 | ||

| Private Medical Institution | 8 | 6 | ||

| Private Practice | 2 | 2 | ||

| Diagnostic Laboratory | 10 | 8 | ||

| Other | 7 | 5 | ||

| Primary clinical specialty | ||||

| Prenatal | 26 | 20 | ||

| Cancer | 35 | 27 | ||

| Pediatrics | 31 | 24 | ||

| General genetics | 10 | 8 | ||

| Metabolic | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cardiology | 4 | 3 | ||

| Adult genetics | 4 | 3 | ||

| Other | 19 | 15 | ||

| Board certificationc | 130 | 98 | ||

a2016 professional status survey (PSS; National Society of Genetic Counselors. 2016 Professional Status Survey. Retrieved from http://nsgc.org)

bUniversity or Medical Institution

cCertified Genetic Counselors (CGC) or Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (CAGC) board certification

Table 2.

Educational experience characteristics of respondents that specifically serve as teachers/instructors for genetic counseling graduate students (n = 106)

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studentsa | Training program affiliationc | 82 | 77 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 5 | |||

| 1–9 | 43 | 41 | Educational setting | ||

| 10–19 | 27 | 26 | University: GCGPd | 87 | 67 |

| 20–29 | 11 | 10 | University: othere | 47 | 37 |

| 30–39 | 6 | 6 | Clinical setting | 48 | 38 |

| 40–49 | 2 | 2 | Laboratory | 5 | 4 |

| 50+ | 12 | 11 | On-line course | 10 | 8 |

| Other | 5 | 4 | |||

| Number of classesa | |||||

| 0 | 14 | 13 | Professional activities | ||

| 1–5 | 55 | 52 | Clinical supervision | 86 | 75 |

| 6–10 | 12 | 11 | Committee (education) | 30 | 26 |

| 11–20 | 7 | 7 | Student mentor/advisor | 60 | 52 |

| 20+ | 18 | 17 | Journal club | 67 | 58 |

| Student research | 51 | 44 | |||

| Number of courses directedb | Other | 12 | 10 | ||

| 0 | 38 | 36 | |||

| 1 | 35 | 33 | Percent (%) time spent teaching | ||

| 2 | 13 | 12 | < 5% | 28 | 26 |

| 3 | 9 | 9 | 6–10% | 22 | 21 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 11–20% | 23 | 22 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 21–50% | 15 | 14 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 51–80% | 14 | 13 |

| 7+ | 6 | 6 | > 80% | 4 | 4 |

aPer academic year

bCourses directed or co-directed per academic year

cAffiliation to genetic counseling training program

dGenetic counseling graduate program courses

eOther university-affiliated courses

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, ranges) were calculated for demographics and competency assessment. The internal consistency reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. Statistical differences among groups were evaluated by Mann-Whitney test (nonparametric t test) after normality test failed (D’Agostino and Pearson test). Nonparametric correlation analysis (Spearman) was used to determine statistically significant relationships. A significance level of 0.05 was used. Analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism® software [Version 5.04 (2010)] and Microsoft Excel (2010). Open-ended responses were evaluated qualitatively for common themes or concerns.

Results

Out of the 3850 NSGC/CAGC members contacted, 259 responses were received, but 93 surveys were excluded due to partial completion. One hundred sixty-six genetic counselors completed the survey (4% response rate). Most respondents met inclusion (130/166; 78%), having taught genetic counseling or other graduate/undergraduate students, while 64% of respondents specifically taught genetic counseling graduate students. Twenty-two percent (36/166) of respondents had never taught. According to the NSGC professional status survey (PSS; n = 2205; NSGC 2016), 72% of genetic counselors are involved in educational activities (approximately, n = 1588). Based on this data, we reached 2% of genetic counselors involved in teaching (130/1588). Table 1 summarizes respondents’ demographics (n = 130), which were representative of the NSGC/CAGC membership (NSGC 2016). On average, the respondents had 10.9 years of genetic counseling experience. Teaching was among the job responsibilities for the majority of responders (84/130). The respondents mostly teach a small number of students (< 20) and classes (< 5) per academic year, which is consistent with size of graduate programs. For 17% of respondents (18/106), teaching represents their primary activity, taking more than 50% of their time. Clinical supervision represents the most common professional activity in addition to teaching (75%; Table 2).

Self-efficacy scales were worded as can do statements: “I can….” followed by a perceived self-efficacy inventory question, such as “Teach genetic counseling students to use current and emerging genetic counseling knowledge to best care for patients” (item 1 in “content knowledge” section; inventory questions listed in Fig. 1). Survey participants were asked to score the can do statements on a scale from 0 (Can not do at all) to 100 (Highly certain can do). Self-efficacy in a variety of teaching tasks organized in the six core competencies was overall fairly high with all average scores higher than 75 (maximum score = 100; Table 1 in supplemental material, Fig. 1). Confidence for all competencies but one (f. ability to find and apply resources) on average scored higher than 80 (range 84–90), with only few individual responses in the 0–20 range and only 2% of individual responses scoring less than 50. The internal consistency reliability was very high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95). Survey participants that have taught but not specifically genetic counseling students (n = 24) overall report similar self-efficacy ratings.

Most self-efficacy ratings did not improve significantly with years of teaching. There was no statistically significant correlation for several ratings or a very modest correlation (p values ranging from not significant to < 0.001; Table 1 in supplemental material). A correlation was noted with percent of time spent teaching. Comparing the two groups—< 10% (68/130) or > 10% of time on teaching (62/130)—all ratings were higher in the latter group and statistically significant for all but three questions (p values ranging from < 0.0001 to 0.0393). However, when comparing the average of all ratings, the difference is modest (81.6 ± 17.9 versus 88.8 ± 13.4; p < 0.0001).

Most genetic counselors reported that curriculum, culture, environment, and financial factors had an impact on effective teaching. The rating level of 2 “some impact” was the most frequent answer for each of these four barriers (respectively 37.7%, 43.1%, 36.9%, and 40.8%). Cultural barriers were least often acknowledged (79.2%), and financial barriers were most often acknowledged (83.1%), but the difference was modest. Several respondents that specified “other barriers” reported time “to adequately plan, update and evaluate the curriculum” as the most significant barrier. Moreover, a couple of respondents commented on the difficulty to “teach genetic counseling students to use current and emerging genetic counseling knowledge to best care for patients’ when not practicing clinically anymore or not being involved in a training program.” Several genetic counselors reported a lack of feedback from students, colleagues, or program directors on their teaching effectiveness.

Counselors were also asked to indicate training and resources used to develop and improve teaching, and rate their effectiveness. Among formal training, planned feedback/feedback session was the most commonly reported (72.3%) and stated as “highly effective” by 25.4% of respondents. Several forms of informal training were commonly done: self-reflection (96.9%), trial and error (96.2%), consultation with other genetic counselors (95.1%), and are considered highly effective by, respectively, 29.2%, 27.7%, and 34.6% of respondents. Uncommon forms of training were having a teaching certificate or degree in education (10.8%), participating in the NSGC education SIG (20.8%), online class/short course (26.2%), and in person class/short course (34.6%) (Fig. 1 in supplemental material). The majority (82.3%) indicated that they would be interested in teaching development.

Discussion

Practice-based competencies (PBC) address different educational roles (ACGC 2013; Doyle et al. 2016), emphasizing the distinction between patient education, clinical supervision and teaching. Professional status surveys offer only a glimpse in the genetic counselors’ involvement in these very distinct activities, without providing detailed information or specific settings (NSGC 2016). There has been some research published on the role of genetic counselors as supervisors, exploring methodologies employed, barriers encountered, and best practices (Eubanks Higgins et al. 2013; Atzinger et al. 2014; Finley et al. 2016; Atzinger et al. 2016). However, as commented by a respondent, “there is extremely limited literature on education of genetic counseling (not much in the way of theory or specific activities). Therefore, it often feels like inventing/re-inventing approaches from scratch and/or in a vacuum.” After all, being professionally skilled does not automatically translate into being an effective teacher (McLeod et al. 2003; Atzinger et al. 2014).

Most genetic counselors supervise students in clinical settings (Eubanks Higgins et al. 2013; Finley et al. 2016; this study), and recently, Finley et al. (2016) reported high self-efficacy ratings for all the clinical supervision competencies explored, with mean values ranging from 84.0 to 94.9. Aiming to evaluate self-perceived efficacy in teaching competencies, our recruitment email and inclusion questions specifically stipulate teaching experience. Our self-efficacy mean values are comparable to what was reported by Finley et al. (2016), albeit slightly lower. The difference could be due to sampling, although both studies have a similar number of respondents. Similar to what was reported for clinical supervision (Finley et al. 2016), we found only a weak correlation between self-efficacy ratings and years of teaching experience. However, spending a significant percent of time teaching (> 10%) seemed associated with higher self-confidence scores. Interestingly, not having enough time to devote to teaching and educational activities was often quoted as reason for lower self-efficacy. Several comments showed that barriers, especially financial and environmental, are an important consideration for the majority of counselors. Addressing barriers to effective teaching, and particularly lack of time and training resources, offers a target for how to help genetic counselors.

The strengths of this study are its use of established medical educator core teaching competencies (Srinivasan et al. 2011) and the self-perceived efficacy framework (Bandura 1995, 1997, 2006), which has been successfully used to evaluate genetic counselors’ confidence in clinical supervision competencies (Finley et al. 2016). Despite low response rate, our participants’ characteristics were similar to the NSGC professional status survey (2016) respondents in age, gender, and geographic distribution, indicating that our respondents were representative of the genetic counseling profession (Table 1). However, the response rate was low; moreover, since the participation to this study was voluntary, it is possible that response was biased toward individuals particularly interested in the topic, and, perhaps, more comfortable evaluating their teaching. The anonymous survey, the rating system, and the instructions were designed to reduce potential effects on self-report such as socially acceptable responses or misunderstandings of a rating scale. However, we cannot exclude interference from these factors or a variable interpretation of the terms used in the survey, which may be unfamiliar to the survey respondents or inadequately described.

Limitations and future directions

The major limitation of this study is that teaching ability is based on respondent’s self-reported perception. Therefore, a correlation between self-perceived efficacy and actual performance could not be established. This is a common concern for this type of study and explains why this relationship is still debated (Heggestad and Kanfer 2005). Further studies directly evaluating the outcomes of genetic counselors teaching are needed. Our survey (available upon request) could help establish a baseline in perceived self-efficacy among the genetic counselors teaching for a specific training program or a group of programs. Measurements could be repeated over time and correlated to student perceptions or student performance. Barrier data also encourages greater examination of solutions like protected teaching time and help with improving curriculum. Moreover, data from this study can be used to implement and improve the highly effective training resources, which includes planned feedback, consulting with other counselors and program faculty, and observing effective teachers.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 21 kb)

(TIF 2206 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted by Justin Gasparini to fulfill a degree requirement for his Master in Genetic Counseling (Research Project). A preliminary version of these findings was presented at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (Poster Presentation).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals for being included in the study.

Animal studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

References

- Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (2013) Standards for accreditation. Retrieved from: http://www.gceducation.org/Pages/Standards.aspx

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (2016). Retrieved from: http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Overview

- Atzinger CL, He H, Wusik K. Measuring the effectiveness of a genetic counseling supervision training conference. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:698–707. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzinger CL, Lewis K, Martin LJ, Yager G, Ramstetter C, Wusik K. The impact of supervision training on genetic counselor supervisory identity development. J Genet Couns. 2014;23:1056–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2006) Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T (eds) Self-Efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Information Age Publishing, Greenwich

- Brink D, Simpson D, Crouse B, Morzinski J, Bower D, Westra R. Teaching competencies for community preceptors. Fam Med. 2018;50(5):359–363. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.578747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon JM, Meece JL, Granger NA. Self-efficacy’s influence on student academic achievement in the medical anatomy curriculum. Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:249–255. doi: 10.1002/ase.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaRosa DA, Skeff K, Friedland JA, et al. Barriers to effective teaching. Acad Med. 2011;86:453–459. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820defbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saintonge DM, Dunn DM. Gender and achievement in clinical medical students: a path analysis. Med Educ. 2001;35:1024–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DL, Awwad RI, Austin JC et al (2016) 2013 review and update of the genetic counseling practice based competencies by a task force of the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling. J Genet Couns 25(5):868–879 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dybowski C, Kriston L, Harendza S. Psychometric properties of the newly developed physician teaching self-efficacy questionnaire (PTSQ) BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):247. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0764-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks Higgins S, Veach P, MacFarlane IM, et al. Genetic counseling supervisor competencies: results of a Delphi study. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:39–57. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9512-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley SL, Veach P, MacFarlane IM, et al. Genetic counseling Supervisors’ self-efficacy for select clinical supervision competencies. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:344–358. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore PA. Academic self-efficacy as a predictor of college outcomes: two incremental validity studies. J Career Assess. 2006;14:92–115. doi: 10.1177/1069072705281367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heggestad ED, Kanfer R. The predictive validity of self-efficacy in training performance: little more than past performance. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2005;11:84–97. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.11.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner BD. An historical review of graduate medical education and a protocol of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education compliance. J Urol. 2004;172:34–39. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000121804.51403.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen RM, Tze VMC. Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. 2014;12:59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod PJ, Steinert Y, Meagher T and McLeod A (2003) The ABCs of pedagogy for clinical teachers. Med Educ, pp. 638–44, England [DOI] [PubMed]

- NSGC (2016) National Society of Genetic Counselors Professional Status Survey. from http://nsgc.org

- Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86:1211–1220. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, Prideaux D. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME guide no. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28:497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29:648–654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC, Dubois DL, Cooper H. The relation between self-beliefs and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review. Educ Psychol. 2004;39:111–133. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3902_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)

(TIF 2206 kb)