Abstract

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is a principal environmental risk factor contributing to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which compromises fetal brain development at critical periods of pregnancy and might be causally linked to ASD symptoms. We report that endogenous activation of the purinergic ion channel P2X7 (P2rx7) is necessary and sufficient to transduce MIA to autistic phenotype in male offspring. MIA induced by poly(I:C) injections to P2rx7 WT mouse dams elicited an autism-like phenotype in their offspring, and these alterations were not observed in P2rx7-deficient mice, or following maternal treatment with a specific P2rx7 antagonist, JNJ47965567. Genetic deletion and pharmacological inhibition of maternal P2rx7s also counteracted the induction of IL-6 in the maternal plasma and fetal brain, and disrupted brain development, whereas postnatal P2rx7 inhibition alleviated behavioral and morphological alterations in the offspring. Administration of ATP to P2rx7 WT dams also evoked autistic phenotype, but not in KO dams, implying that P2rx7 activation by ATP is sufficient to induce autism-like features in offspring. Our results point to maternal and offspring P2rx7s as potential therapeutic targets for the early prevention and treatment of ASD.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder caused by genetic and environmental factors. Recent studies highlighted the importance of perinatal risks, in particular, maternal immune activation (MIA), showing strong association with the later emergence of ASD in the affected children. MIA could be mimicked in animal models via injection of a nonpathogenic agent poly(I:C) during pregnancy. This is the first report showing the key role of a ligand gated ion channel, the purinergic P2X7 receptor in MIA-induced autism-like behavioral and biochemical features. We show that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of both maternal and offspring P2X7 receptors could reverse the compromised brain development and autistic phenotype pointing to new possibilities for prevention and treatment of ASD.

Keywords: ASD, ATP, JNJ47965567, MIA, P2X7, poly(I:C)

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorder attracting attention because of its rapidly increasing prevalence worldwide (Knuesel et al., 2014; Estes and McAllister, 2015). ASD is thought to be the result of interplay between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors (Ghosh et al., 2013), and recent meta-analyses indicated the role of maternal infection as a risk factor strongly associated with the later emergence of ASD in offspring (Jiang et al., 2016). Furthermore, it was suggested that immune activation of the maternal host, rather than an exogenous pathogenic microorganism, is responsible for this elevated risk because autism-like behavioral and biochemical alterations were induced in offspring by maternal treatment with nonpathogenic double-stranded RNA polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) in rodents and nonhuman primates (Meyer, 2014; Careaga et al., 2017). In mice, maternal immune activation (MIA) by poly(I:C) at embryonic age (E12-E18) induces proinflammatory cytokine production, especially IL-6, in maternal plasma and to a lesser extent in the fetal brain, which is probably mediated through activated TLR3 expressed by circulating immune cells. In turn, IL-6, directly or indirectly, influences critical steps of brain development via downstream induction of IL-17a (Choi et al., 2016; Shin Yim et al., 2017), leading to autism-like behavioral symptoms in offspring (Estes and McAllister, 2016). While these cytokines are normally downregulated during mid-pregnancy, increased levels of gestational IL-6 were associated with later emergence of ASD and correlated with intellectual disability in humans (Jones et al., 2017). Maternal cytokines profoundly affect neurogenesis, gliogenesis, neuronal migration, synapse formation, and elimination leading to aberrant cortical and cerebellar development (Meyer et al., 2006; Deverman and Patterson, 2009; Shin Yim et al., 2017). Recently, it has been found that region-specific disorganization of cortical cytoarchitecture manifested in a loss of transcription factors special AT-rich-sequence-protein 2 (SATB2), and T-brain-1 (TBR1) is the main target of maternal IL-17a produced by Th17 cells upon maternal inflammation in the developing brain (Kim et al., 2017), and these changes are causally linked to behavioral alterations in offspring (Shin Yim et al., 2017). However, the molecular signaling machinery responsible for poly(I:C) induced MIA and its conversion to abnormal brain development and an autistic phenotype in offspring is unclear.

Interestingly, in addition to compromised brain development due to MIA, human autistic subjects display a permanently altered immune status in the brain characterized by microglia activation (Suzuki et al., 2013) and elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Masi et al., 2015). In addition to MIA, further postnatal factors might contribute to altered immune homeostasis and maintain dysfunctional behavior. These observations raise the possibility that interaction with molecular signaling pathways instrumental for permanently altered immune status might also be able to reverse behavioral symptoms.

The purinergic P2X7 receptor (P2rx7) is a ligand-gated ion channel sensitive to high extracellular ATP levels, expressed by immune cells and intrinsic cells of the CNS (Sperlágh and Illes, 2014). P2rx7s are activated by the elevation of extracellular ATP during cellular damage or inflammatory conditions, and its activation serves as a maturation signal for post-translational processing of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, or IL-18. This process requires two signals: a primary signal, termed pathogenic or danger associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs), acting at TLR receptors, which leads to the transcription of a cytokine precursor; and a secondary stimulus triggering nucleotide-binding domain-like receptors (NLRP3) oligomerization into intracellular multiprotein complexes, forming inflammasomes. These inflammasomes then cleave proteolytically the precursor protein into mature, leaderless cytokines, which are released to the extracellular space and boost further inflammation (Bartlett et al., 2014; de Torre-Minguela et al., 2017; Adinolfi et al., 2018). P2rx7 activation is one of such secondary stimuli, which could be responsible for converting innate immune response to inflammation following MIA. Although P2rx7 activation has been recognized as a trigger or mediator of many CNS pathologies (Sperlágh and Illes, 2014; Bhattacharya, 2018; Wei et al., 2018), no such role has been demonstrated in animal models of ASD.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Animals were kept under standard laboratory conditions in 12 h light-dark cycles with food and water provided ad libitum. All efforts were taken to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. All experiments followed the ARRIVE guidelines and were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, US Public Health Service. The local Animal Care Committee of the Institute of Experimental Medicine approved all experimental procedures (Permission PEI/001/778-6/2015). Experiments were performed between 9:00 and 14:00 in the animal housing room. Experiments were performed on male and female P2rx7+/+ (C57BL/6) and P2rx7-deficient mice (weighing 25–30 g) for breeding, and their male offspring for behavior and further experiments. P2rx7−/− mice were obtained, bred, and genotyped as described previously (Koványi et al., 2016). Briefly, homozygous P2rx7+/+ mice were bred on a C57BL/6J background. The original breeding pairs of P2rx7−/− mice were kindly supplied by Christopher Gabel from Pfizer. The animals contained the DNA construct P2X7-F1 (5′-CGGCGTGCGTTTTGACATCCT-3′) and P2X7-R2 (5′-AGGGCCCTGCGGTTCTC-3′), previously shown to delete the P2rx7 (Solle et al., 2001). Genomic DNA was isolated from the tails of P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− animals, and the genotypes were confirmed by PCR analysis. An overall eight backcrosses on C57BL/6 were performed for the P2rx7 KO mouse colony used in our experiments.

Experimental design

The MIA model protocol was designed and performed based on the protocol of R.K. Naviaux et al. (2013).

Primiparous dams were mated at 12–14 weeks of age. Mating trios of P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− mice consisted of 2 females and 1 male in each box. In Experiments 1–8, breeding partners were from the same genotype; in Experiments 9 and 10, females and males were from different genotypes. Experienced sires were 3 months old. Sires were randomly assigned as mating pairs for dams regardless of further treatment (poly(I:C) or saline). To induce MIA, a 3 mg/kg dose of poly(I:C) on E12.5 d (Experiments 1–4 and 6–10) and 1.5 mg/kg of poly(I:C) on E17.5 (Experiments 1, 3, 4, 6–9) were injected intraperitoneally to pregnant dams randomly assigned to different treatment groups. In Experiment 5, 400 μm ATP was injected intraperitoneally to pregnant dams on E12.5 d. Control mice received saline injection (100 μl) at the same time as immune-activated animals. Offspring were weaned at 4 weeks of age into cages of 3–5 animals. Behavioral experiments were performed on test-naive male mice at 8 weeks of age in the same order (social preference, self-grooming test, marble-burying test, rotarod) by an experimenter blinded to the treatments. After the behavior tests, animals were killed under light CO2 anesthesia at an age of 80–90 d, and samples were collected for synaptosome preparation and electron microscopy (EM). In other cases (Experiment 2), experiments were terminated 2 or 48 h after the first dose of poly(I:C) injection, and maternal plasma and fetal brain samples were collected for cytometric bead array analyses, HPLC, and immunohistochemistry, respectively.

Sample size was calculated as described previously (Charan and Kantharia, 2013). A pilot study was performed to measure the basic sociability scores of MIA and saline-treated mice. We estimated sample size using G*Power 3.1.9.2 software (power: 0.8; α error probability: 0.05; direction of effect: two tails, effect size: 0.6698398; coefficient of determination ρ2: 0.44868533; expected attrition or death of animals: 10%, sample size: ∼13 animals/group) that indicated ∼156 male offspring were required. Because fecundity was ∼40% after poly(I:C) treatment and 80% after saline treatment, we calculated a theoretical sample size of 270 male offspring. Based on our previous experience, one pregnant dam gives birth to an average of 5 males; therefore, 54 breeding pairs were established for the experiments. Samples for ex vivo experiments were taken from animals used in behavioral tests.

Every experiment was performed on at least 2 or 3 independent litters; and when P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− animals were compared, littermate controls were used.

Drugs and treatments

The following drugs were used in our experiments: poly(I:C) potassium salt (Sigma-Aldrich, P9582, batch 086M4045V), JNJ47965567 (30 mg/kg, Tocris Bioscience), and ATP disodium salt hydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, A2383). Drugs were dissolved in sterile saline, except for JNJ47965567, which was dissolved in 30% Captisol solution (sulfobutyl ether-7 β-cyclodextrin). Controls for the experiments were saline or Captisol solutions in the same volume as the compounds. Prenatal administration of JNJ47965567/vehicle (30 mg/kg i.p.) was performed 2 h before MIA. Postnatal administration of JNJ47965567/vehicle (30 mg/kg i.p.) was a single treatment on the day of the first behavior test on mice randomly assigned to treatment groups.

Behavior tests

Social preference test.

Social preference was performed according to the method described by R.K. Naviaux et al. (2013) with minor modifications. Social preference was measured by using a 3-chamber Plexiglas arena (40 × 60 cm) divided into 3 equal chambers (20 × 40 cm each) with a 4 × 4 cm square opening cut into them to allow test mice to move between chambers. Plexiglas cages were put into both of the side chambers. Sniffing zones were assigned around the cages. The experiments consisted of two phases. In Phase 1, the test mouse could explore the whole arena (habituation). In Phase 2, the test mouse was put into the center chamber briefly, the doors were closed, and one unfamiliar stranger mouse of the same age and sex was placed into one of the cages. The other cage remained empty. Then the doors were opened, and the test mouse could explore the arena for 10 min. Ethovision XT 10 system (Noldus) connected with an overhead camera was used to video track and record the time the test mouse spent in each of the sniffing zones. The location of the stranger mouse was alternated across trials. Social preference as a percentage was calculated as 100 multiplied by the time the test mouse spent interacting with the stranger mouse (tM) divided by the total time a test mouse spent with the stranger and the empty cage (tE) as follows:

|

Rotarod test.

Rotarod test was performed according to the method described by R.K. Naviaux et al. (2013) using an IITC Rotarod apparatus (4-cm-diameter rod). The instrument enables the simultaneous examination of 5 mice in separate compartments. Mice were trained at constant 4 rpm speed for three consecutive trials to achieve the ability to maintain balance on the rod for at least 30 s. Acceleration phase testing was performed on two subsequent days at four trials/d. Mice were individually placed onto the rod. The initial speed was 4 rpm, which accelerated to 40 rpm in 5 min. The intertrial interval was at least 30 min. Latency of falling down was measured in seconds.

Self-grooming test.

Self-grooming test was performed by the method described by Kyzar et al. (2011) with minor modifications. Before the experiments, the mice were transported to the experimental room to acclimatize for at least 1 h. Test mice were put into clear glass observation cylinders (12 cm diameter, 20 cm height) individually for 10 min, and their spontaneous novelty-evoked grooming behavior was video recorded. The observation cylinder was cleaned using water between the tests. Behavior was manually scored using Observer XT software (Noldus), and the cumulative duration of self-grooming in seconds was counted by the software.

Marble burying test.

Marble burying test was designed based on the method described by Malkova et al. (2012). Clean cages (36.7 × 14.0 × 20.7 cm) were filled with 5 cm corn cob bedding. Then, 20 blue glass marbles were gently placed onto the surface of the bedding in a 4 × 5 arrangement at the same distance from each another. At least one-fifth of the surface remained free from marbles. Testing animals were placed onto the marble free area, and the number of marbles buried was measured within a 10 min testing period. Marbles were counted as buried if they were covered by ≥60% bedding.

Open field test.

Open field test was performed following the protocol of R.K. Naviaux et al. (2013). Mice were placed in the middle of a white square box (40 × 40 cm), and locomotor activity was recorded by the Ethovision XT 10 system (Noldus) for 10 min. The total distance covered during the analysis was measured in centimeters.

Brain neuropathology and confocal microscopy

After perfusion with 4% PFA and overnight postfixation of brains in 4% PFA at 4°C, 50 μm parasagittal sections of the cerebellar vermis were used for immunoreaction. Slices were permeabilized with blocking solution containing 5% normal horse serum, 1% BSA, and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1 m PB for 2 h at room temperature (RT), and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-calbindin antibody (Swant, CB-38a, 1:12,000). Sections were carefully rinsed and washed with PB and stained with fluorescent secondary antibody (Alexa-488 against rabbit, 1:3000, Invitrogen) for 2 h at RT. Purkinje cells in lobe VII of the cerebellum were imaged with a confocal Nikon C2 microscope, and counting was performed manually while the length of the lobe was measured by ImageJ.

Synaptosome preparation and EM

Synaptosome fractions were prepared following the protocol of Köfalvi et al. (2003). After decapitation, half brains were homogenized in sucrose-HEPES solution (0.32 m sucrose, 0.01 m HEPES free acid, 0.63 mm Na2EDTA, pH 7.4) at 4°C and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min. Supernatant was recentrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. P2 pellets were resuspended in 45% (v/v) Percoll-Krebs solution (Krebs: 113 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 25 mm NaHCO3, 5.5 mm glucose, 1.5 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4°C for 2 min to eliminate mitochondria. The top layer was washed twice at 4°C and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 2 min in Krebs solution. Synaptosome pellets were fixed with 4% PFA in 0.1 m PBS for 60 min at RT followed by washing with PBS, and samples were postfixed in 1% OsO4 (Taab Laboratories) for 30 min. After rinsing the intact fixed pellets within the Eppendorf tubes with distilled water, the pellets were dehydrated in graded ethanol, including block staining with 1% uranyl-acetate in 50% ethanol for 30 min, and were embedded in Taab 812 (Taab Laboratories). Overnight polymerization of samples at 60°C was followed by ultrathin sectioning and imaging by a 7100 electron microscope (Hitachi) equipped with a Megaview II digital camera (lower resolution, Soft Imaging System). Electron micrographs were taken at 20,000 or 30,000 magnifications in all investigated groups, with 4–6 animals per group. Intact and malformed synaptosomes, 45–55 for each investigated animal, were counted manually twice by an investigator blinded to the treatments.

Fetal brain immunohistochemistry

Fetal heads were collected 48 h after the intraperitoneal injection of dams with poly(I:C) (3 mg/kg) or saline, and samples were immersion fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h at 4°C. After cryoprotection in 15% sucrose (20 min) and 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C, 20 μm cryosections were cut using a cryostat (Microm HM550, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Finetek). Sections were washed in PB, permeabilized with 100 mm Na-citrate for 30 min at 65°C and 0.4% Triton X-100 for 20 min at RT, and blocked in 2% normal goat serum and 1% BSA for 1 h at RT. Primary SATB2 and TBR1 antibodies (SATB2 1:100 ab51502, TBR1 1:500 ab31940, Abcam) were applied overnight at 4°C; then slices were rinsed and washed three times in PB, incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:400 AlexaFluor-594 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse 715–585-150, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, 1:1000 Alexa-488 Anti-Rabbit, Invitrogen) containing 1:10,000 Hoechst 33342 (Tocris Bioscience) for 1 h at RT, and rinsed and washed in PB again. Slides were covered with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector), and the fetal cortex was imaged with a confocal Nikon C2 microscope at 20× magnification. TBR1 intensity was measured in the cortical plate with ImageJ software.

Maternal plasma and fetal brain cytokine analyses

Fetal brain samples and maternal plasma were collected 2 h after the intraperitoneal injection of poly(I:C) (3 mg/kg i.p.) or saline. After tissue homogenization and centrifugation, as described previously (Chapman et al., 2009; Dénes et al., 2010), supernatants were collected to measure the levels of the following inflammatory mediators: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and CXCL1 (KC) using BD Cytometric Bead Array Flex Sets (BD Biosciences). Measurements were performed on a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using the FCAP Array version 5 software (Soft Flow). Cytokine concentrations of brain tissue were normalized to total protein levels measured by photometry using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pierce). Absorbance was measured at 560 nm with a Victor 3V 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer). The cytokine levels of plasma are expressed as picograms per milliliter.

HPLC determination of monoamines, adenine nucleotides and nucleoside content

Adenine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, AMP), adenosine (Ado) in extracts from embryonic mouse brain tissue and maternal plasma were determined by using HPLC. Potassium citrate-treated maternal blood was cooled in an ice water bath for 15 min and, after that time, gently centrifuged for 10 min at 2000 rpm and 0°C. The plasma samples were centrifuged again to remove platelets and remaining cells (5000 rpm, 5 min, 0°C). The resulting plasma samples (200 μl) were treated with 20 μl of ice-cold 4 m perchloric acid solution that contained theophylline (as an internal standard) at 100 μm concentration and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min at 0°C to remove precipitated proteins. To neutralize the pH of the resulting solution, supernatant (100 μl) was treated with 4 m K2HPO4 (10 μl) and diluted with water (490 μl), and the centrifugation step was repeated. For analysis (500 μl) the resulting sample was injected onto the column. After the preparation of the whole embryonic mouse brain, the native tissue was frozen by liquid nitrogen. The weighed frozen tissue was homogenized in an appropriate volume of ice-cold 0.1 m perchloric acid that contained theophylline (as an internal standard) at 10 μm concentration and 0.5 mm sodium metabisulphite (antioxidant for biogenic amines). The suspension was centrifuged at 3510 × g for 10 min at 0°C-4°C. The perchloric anion was precipitated by addition of 3 μl of 1 m potassium hydroxide to 70 μl of the supernatant. The precipitate was then removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was kept at −20°C until analysis. The pellet was saved for protein measurement (Lowry et al., 1951). The levels of adenine nucleotides and adenosine were determined by online column switching HPLC using Discovery HS C18 50 × 2 mm and 150 × 2 mm columns (5 and 3 μm packing, respectively) with LC-20 AD (Shimadzu, Analytical & Measuring Instruments Division) and were detected (set at 253 nm) by its UV absorption (Agilent Technologies, 1100 series). The flow rate of the mobile phases (A: 10 mm potassium phosphate, 0.25 mm EDTA, 0.45 mm octane sulfonyl acid sodium salt; and B: with 6% acetonitrile (v/v), 2% methanol (v/v), pH 5.2) was 350 or 450 μl/min, respectively, in a step gradient application. The enrichment and stripping flow rate of buffer A was during 4 min, and the total run time was 55 min. Concentrations were calculated by a 2 point calibration curve using internal standard method. The data are expressed as picomol per milligrams of protein or nanomol per liter.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of n observations, where n indicates biological replicates, from several independent litters. We did not exclude any sample or animal from the analyses. Data normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Shapiro–Wilk test. We used two-way ANOVA followed by Fischer LSD test for investigating treatment effects in two genotypes or investigating complex treatment effects. When data did not follow a normal distribution even after logarithmic transformation, a nonparametric test (i.e., Mann–Whitney test) was used. GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software) and Statistica 13 (Dell) software were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Genetic deficiency of P2rx7 prevents MIA-induced behavioral and histological changes in mice

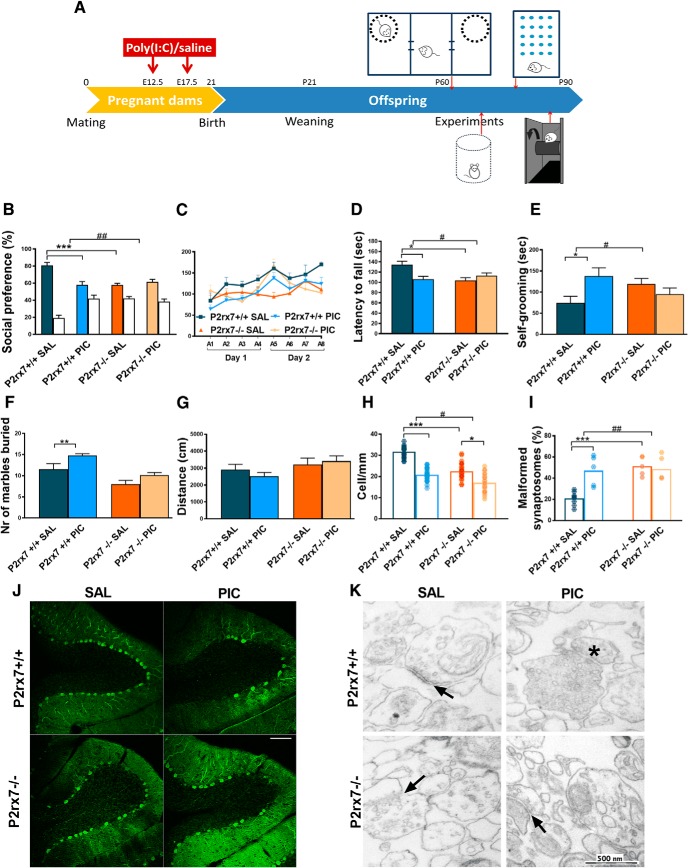

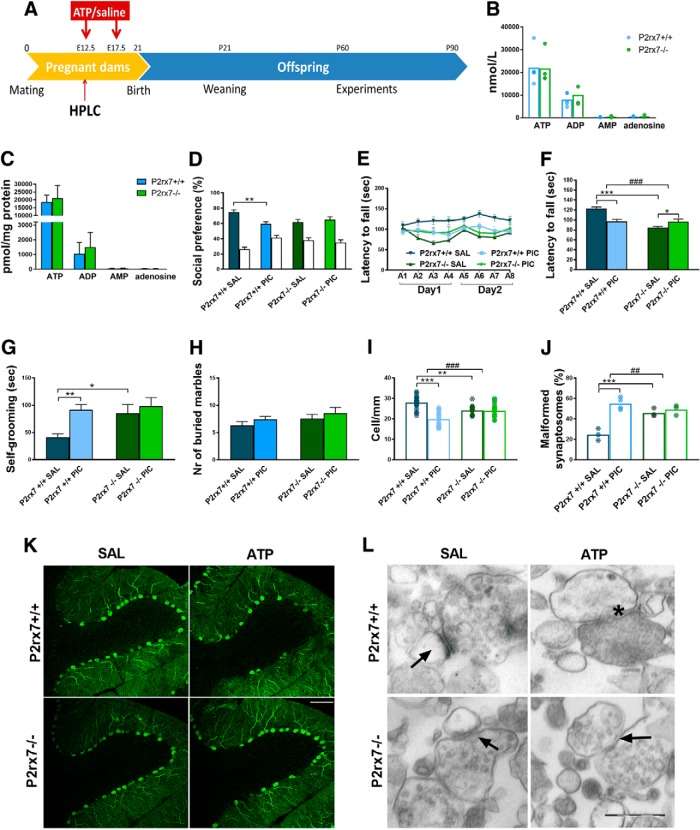

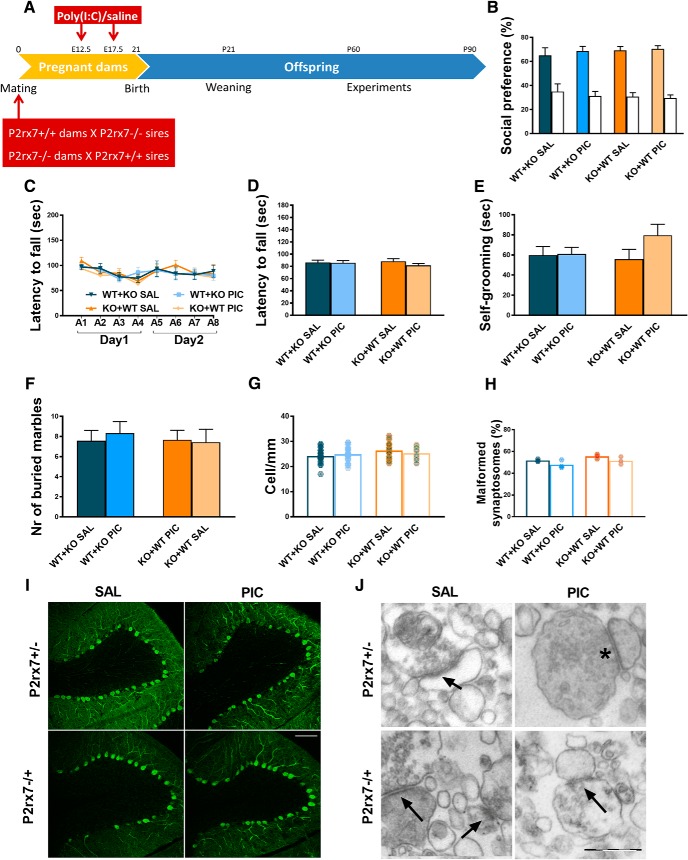

At first, we examined how MIA affects an autistic-like phenotype in the absence and presence of P2rx7s in a previously established mouse poly(I:C) model (R.K. Naviaux et al., 2013). Drug and test-naive P2rx7 WT (P2rx7+/+) and deficient (P2rx7−/−) pregnant C57BL/6J mouse dams were injected with poly(I:C) at E12.5 (3 mg/kg i.p.) and E17.5 (1.5 mg/kg i.p.), and behavioral phenotype was examined between P60 and P90 (Experiment 1; Fig. 1A). Offspring of poly(I:C)-treated P2rx7+/+ dams displayed decreased social preference in the three-chamber social interaction test (Fig. 1B; for exact n, F, and p values for all experiments, see Table 1); impairment of motor coordination in the accelerating rotarod test (Fig. 1C,D), and increased repetitive behaviors reflected in self-grooming (Fig. 1E) and marble burying (Fig. 1F), compared with offspring of saline-treated P2rx7+/+ dams. Collectively, these observations suggested that offspring of poly(I:C)-treated P2rx7+/+ dams have an ASD-like phenotype. These treatment-related behavioral alterations were not observed in offspring from poly(I:C)-treated P2rx7−/− mice (Fig. 1B–F). In addition, genotype-related, treatment-independent changes were also observed: lower sociability (Fig. 1B), decreased performance on the rotarod (Fig. 1C,D), and fewer marbles buried (Fig. 1F). Basal locomotor activity measured in the open field arena was not changed by either maternal poly(I:C) treatment or genotype (Fig. 1G). After behavior tests, offspring brains were examined for further ASD-specific morphological alterations. Lower number of Purkinje neurons was detected in cerebellar lobe VII, and the proportion of malformed synaptosomes increased after treatment (Fig. 1H–K). Fewer Purkinje cells were found in P2rx7−/− (Fig. 1H,J), whereas poly(I:C) elicited a further, but alleviated decrease. Higher proportion of malformed synaptosomes was observed after poly(I:C) treatment. P2rx7 deficiency by itself elicited a similar increase in the vulnerability of synaptosomes, yet MIA lost its effect (Fig. 1I,K). In summary, features of MIA-induced autistic-like phenotype were not observed in P2rx7−/− offspring. Although genetic deficiency of P2rx7s mimicked certain aspects of autistic phenotype, these changes were not replicated by either maternal or offspring P2rx7 blockade (see Figs. 3, 4). Therefore, these changes are probably due to intrinsic or developmental effect of genetic knockdown rather than acute functional P2rx7 deficiency.

Figure 1.

P2X7 receptor (P2rx7) gene deficiency disrupts MIA by poly(I:C) (PIC) on the offspring autistic phenotype. A, Overview of experimental protocol (Experiment 1). B, MIA elicited social deficit in P2rx7+/+ mice, whereas no effect of PIC was observed in P2rx7−/− animals, although P2rx7−/− mice displayed decreased social preference compared with P2rx7+/+ counterparts. White columns represent the percentage of interaction with the inanimate cages. PIC-treated P2rx7+/+ animals showed (C, D) impaired motor coordination that was absent in P2rx7−/− mice and (E, F) increased repetitive behaviors (i.e., self-grooming and marble burying that were absent in P2rx7−/− mice). G, Basal locomotor activity was not affected by poly(I:C) administration in either WT (P2rx7+/+) or KO (P2rx7−/−) animals. H, Cerebellar Purkinje cell number decreased in lobule VII by MIA in P2rx7+/+ offspring is ameliorated in P2rx7−/− mice; however, a genotype-related difference was also detected. Data show 20–30 technical replicates in n = 3 or 4 animals. I, MIA increased the number of malformed synapses in P2rx7+/+ but not in P2rx7−/− mice. A higher proportion of malformed synaptosomes was present in P2rx7−/− mice compared with saline (SAL)-treated P2rx7+/+ mice. Exact n, F, and p values are provided in Table 1. J, Representative image of calbindin-labeled Purkinje cells in lobule VII of the cerebellum. Scale bar, 100 μm. K, Representative EM image of synaptosome preparations. Malformed synapses (asterisk) showed highly different structure (uneven membranes, irregular postsynaptic densities) from normally developed synapses (arrows). *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA #p < 0.05. ##p < 0.01.

Table 1.

Exact p values for all statistical calculations and n = biological replicates in each experiment

| Figure | Statistical analysis | F value | p value/U value | Post hoc | p value | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,39) = 12.044 | 0.00128 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000054 | 9,16 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.524 | 8,10 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.000358 | 9,8 | ||||

| 1C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,28) = 5.433 | 0.0272 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.0201 | 5,8 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.412 | 10,10 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.0119 | 5,10 | ||||

| 1E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,38) = 5.1135 | 0.0296 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.0199 | 8,16 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.404 | 8,10 | ||||

| 1F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,39) = 0.37383 | 0.544 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.0049 | 9,16 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.079 | 8,10 | ||||

| 1G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,20) = 0.08529 | 0.36674 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.394482 | 6,6 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.667652 | 6,6 | ||||

| 1H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,10) = 5.162 | 0.0464 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.0000566 | 4,4 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.0201 | 3,3 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.000335 | 4,3 | ||||

| 1I | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,18) = 8.9839 | 0.00773 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.00023 | 8,5 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.959 | 4,5 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.000246 | 8,4 | ||||

| 2B | Mann–Whitney | 0.004329 | ATP | 5,6 | ||

| 0.004329 | ADP | 5,6 | ||||

| 0.082251 | AMP | 5,6 | ||||

| 0.125541 | Adenosine | 5,6 | ||||

| 2C | Mann–Whitney | 0.000000 | ATP | 31,21 | ||

| 0.459082 | ADP | 31,21 | ||||

| 0.000000 | AMP | 31,21 | ||||

| 0.234949 | Adenosine | 31,21 | ||||

| 2D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,8) = 20.965 | 0.0018 | IL-1α | ||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000556 | 3,3 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,8) = 92.090 | 0.00001 | IL-6 | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000519 | 3,3 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.000044 | 3,3 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,8) = 104.90 | 0.00001 | KC | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.007849 | 3,3 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.000004 | 3,3 | ||||

| 2E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,21) = 11.415 | 0.00284 | IL-6 | ||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000719 | 6,6 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,21) = 3.6735 | 0.06899 | KC | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000236 | 6,6 | ||||

| 2F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,10) = 0.24706 | 0.61524 | IL-6 | ||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.006896 | 4,3 | ||||

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.024084 | 4,3 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,10) = 0.43155 | 0.52606 | IL-10 | |||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.046575 | 4,3 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,10) = 0.44738 | 0.51873 | KC | |||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.003971 | 4,3 | ||||

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.019628 | 4,3 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,10) = 0.06374 | 0.80580 | TNF-α | |||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.046575 | 4,3 | ||||

| 2G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,14) = 37.980 | 0.00002 | IL-6 | ||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.0000001 | 5,5 | ||||

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.011356 | 4,4 | ||||

| Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,14) = 17.126 | 0.00100 | KC | ||||

| vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.000329 | 5,5 | ||||

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.204446 | 4,4 | ||||

| 2I | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,56) = 16.578 | 0.00015 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000001 | 3,3 |

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.009244 | 3,3 | ||||

| 2J | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,56) = 17.348 | 0.00011 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.000001 | 3,3 |

| 3B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 15.4 | 0.00051 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.00076 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.0868 | 8,8 | ||||

| 3C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 10.245 | 0.00340 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.0285 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.0349 | 8,8 | ||||

| 3E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 2.1410 | 0.155 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.0122 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.547 | 8,8 | ||||

| 3F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 27.917 | 0.00001 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.00000992 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.0452 | 8,8 | ||||

| 3G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,45) = 10.538 | 0.00221 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.00011 | 3,3 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.941 | 3,3 | ||||

| 3H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction pretreatment × treatment(1,16) = 61.075 | 0.000000750 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.00000000055 | 3,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.0478 | 4,5 | ||||

| 4B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.13636 | 0.71470 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.773 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.818855126 | 8,8 | ||||

| 4C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.36544 | 0.55037 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.622871459 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.187131649 | 8,8 | ||||

| 4E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.05454 | 0.81704 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.519973276 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.750358047 | 8,8 | ||||

| 4F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.59189 | 0.44813 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.331080732 | 8,8 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.921913745 | 8,8 | ||||

| 4G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,69) = 2.4837 | 0.11961 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.000285 | 3,3 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.161824 | 3,3 | ||||

| 4H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,8) = 0.2244 | 0.64836 | vehicle-saline–vehicle-poly(I:C) | 0.676745 | 3,3 |

| JNJ-saline–JNJ-poly(I:C) | 0.3023 | 3,3 | ||||

| 5D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,41) = 2.5759 | 0.01383 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.002692 | 12,15 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.485435 | 9,9 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.002334 | 12,9 | ||||

| 5E, F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,28) = 35.872 | 0.0000 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.000003 | 12,15 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.000000 | 9,9 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.011589 | 12,9 | ||||

| 5G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,41) = 2.5759 | 0.11618 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.001591 | 12,15 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.486812 | 9,9 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.012792 | 12,9 | ||||

| 5H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,41) = 0.00184 | 0.96603 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.286530 | 12,9 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.410385 | 9,9 | ||||

| 5I | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,74) = 27.482 | 0.96603 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.000000 | 3,3 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.001010 | 3,3 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.830904 | 3,3 | ||||

| 5J | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,9) = 20.168 | 0.00151 | P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-ATP | 0.000042 | 3,4 |

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-ATP | 0.475737 | 3,3 | ||||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-saline | 0.000934 | 3,3 | ||||

| 6B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.13636 | 0.71470 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.773 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.818855126 | 8,8 | ||||

| 6C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.36544 | 0.55037 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.622871459 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.187131649 | 8,8 | ||||

| 6E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.05454 | 0.81704 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.519973276 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.750358047 | 8,8 | ||||

| 6F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,28) = 0.59189 | 0.44813 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.331080732 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.921913745 | 8,8 | ||||

| 6G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,69) = 2.4837 | 0.11961 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.000285 | 3,3 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.161824 | 3,3 | ||||

| 6H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteractionpretreatment × treatment(1,8) = 0.2244 | 0.64836 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.676745 | 3,3 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.3023 | 3,3 | ||||

| 7 | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,48) = 12.419 | 0.00094 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.000007 | 3,3 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.617169 | 3,3 | ||||

| 8B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,28) = 0.00840 | 0.92761 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.493 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.4171 | 8,8 | ||||

| 8C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,28) = 0.93197 | 0.34262 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.208 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.937 | 8,8 | ||||

| 8E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,28) = 0.54089 | 0.46818 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.681 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.536 | 8,8 | ||||

| 8F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,28) = 0.02312 | 0.88024 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.776 | 8,8 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.943 | 8,8 | ||||

| 8G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,50) = 1.4293 | 0.23753 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.0428 | 3,3 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.742 | 3,3 | ||||

| 8H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction maternal tr × postnatal tr(1,8) = 0.26085 | 0.62333 | saline-vehicle–poly(I:C)-vehicle | 0.509306 | 3,3 |

| saline-JNJ–poly(I:C)-JNJ | 0.195369 | 3,3 | ||||

| 9B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,25) = 0.08495 | 0.77310 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.555425 | 7,6 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.823292 | 7,9 | ||||

| 9C, D | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,28) = 0.87193 | 0.35841 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.929087 | 7,6 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.169450 | 7,9 | ||||

| 9E | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,25) = 1.3108 | 0.26309 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.929275 | 7,6 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.083232 | 7,9 | ||||

| 9F | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,25) = 0.05514 | 0.81626 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.648889 | 7,6 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.874954 | 7,9 | ||||

| 9G | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,74) = 27.482 | 0.96603 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.392272 | 3,3 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.816451 | 3,3 | ||||

| 9H | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,8) = 0.05420 | 0.82176 | P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.170924 | 3,3 |

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.104077 | 3,3 | ||||

| 10B | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,12) = 12.497 | 0.00411 | IL-6 | ||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000000 | 4,4 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.000000 | 4,4 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,12) = 3.9123 | 0.07136 | IL-10 | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000682 | 4,4 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.107532 | 4,4 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,12) = 0.23116 | 0.63931 | KC | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.008245 | 4,4 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.029039 | 4,4 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,12) = 5.0053 | 0.04502 | TNF-α | |||

| P2rx7+/+-saline–P2rx7+/+-poly(I:C) | 0.000003 | 4,4 | ||||

| P2rx7−/−-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.000341 | 4,4 | ||||

| 10C | Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,24) = 0.20677 | 0.65340 | IL-6 | ||

| P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.000748 | 7,7 | ||||

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/−-poly(I:C) | 0.003678 | 7,7 | ||||

| Two-way ANOVA | Finteraction genotype × treatment(1,24) = 0.35471 | 0.55703 | KC | |||

| P2rx7+/−-saline–P2rx7+/−-poly(I:C) | 0.524458 | 7,7 | ||||

| P2rx7−/+-saline–P2rx7−/+-poly(I:C) | 0.845986 | 7,7 |

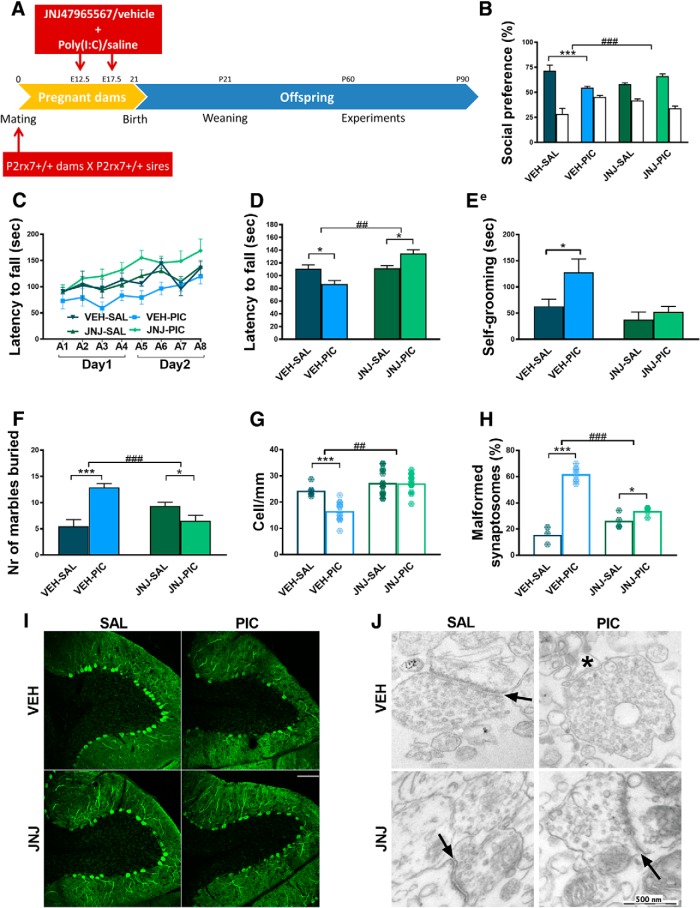

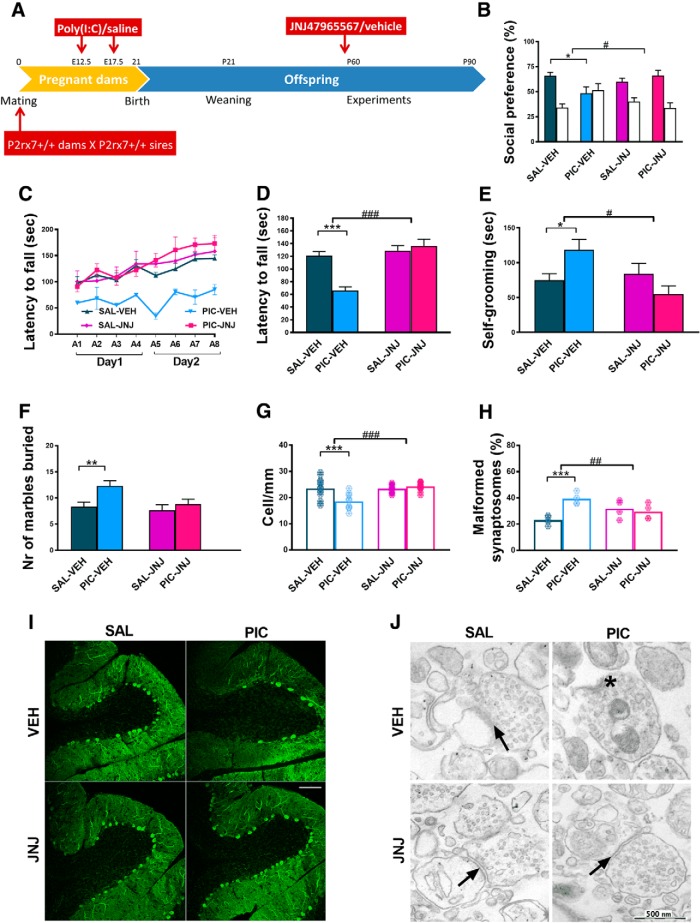

Figure 3.

Maternal JNJ47965567 antagonist treatment prevented MIA-induced effects in P2rx7+/+ offspring. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 3). Pretreatment prevented social deficit (B), reversed motor coordination deficiency (C,D), and normalized repetitive behavior (E, F). G, I, After pharmacological P2rx7 blockade, MIA had no influence on Purkinje cells (G, I) or on synapses (H, J). Scale bar, 100 μm. Asterisk indicates a malformed synaptosome. Arrows indicate intact synapses. Exact n, F, and p values are provided in Table 1. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA #p < 0.05. ##p < 0.01. ###p < 0.001.

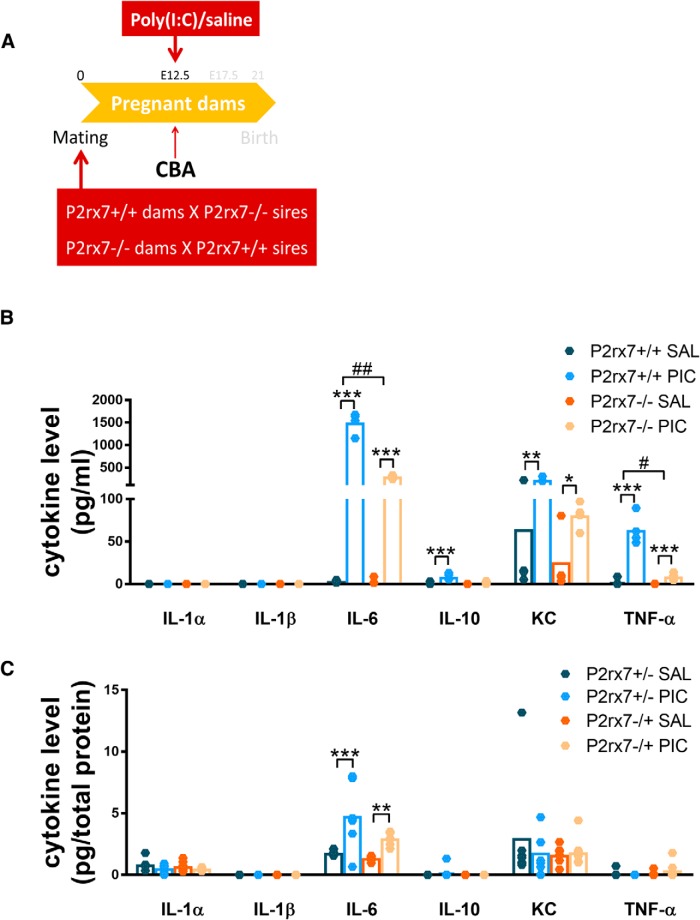

Figure 4.

Maternal treatment of P2rx7-deficient dams with the P2rx7 antagonist JNJ47965567 (JNJ, 30 mg/kg i.p., 2 h before PIC injection) did not affect the phenotype of P2rx7−/− offspring. A, Overview of the experimental protocol (Experiment 4). JNJ pretreatment did not alter the social behavior (B), motor coordination deficits (C, D), and repetitive behaviors (E, F). G, The pharmacological inhibition of maternal P2rx7s in MIA did not influence the density of Purkinje cells (H) or the structure of synapses in the offspring. Exact n, F, and p values are provided in Table 1. I, Representative image of calbindin-labeled Purkinje cells in lobule VII of the cerebellum. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 17–20 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. J, Representative EM image of synaptosomes. Asterisks indicate disturbed synaptosomes. Arrows indicate normal synapses. Scale bar, 500 nm. *p < 0.05. ***p < 0.001.

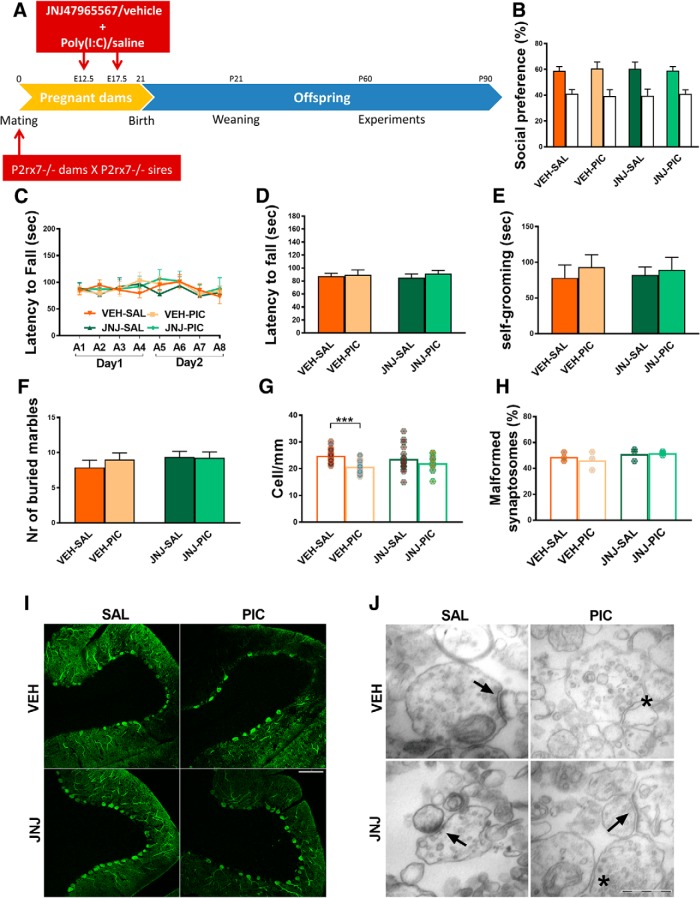

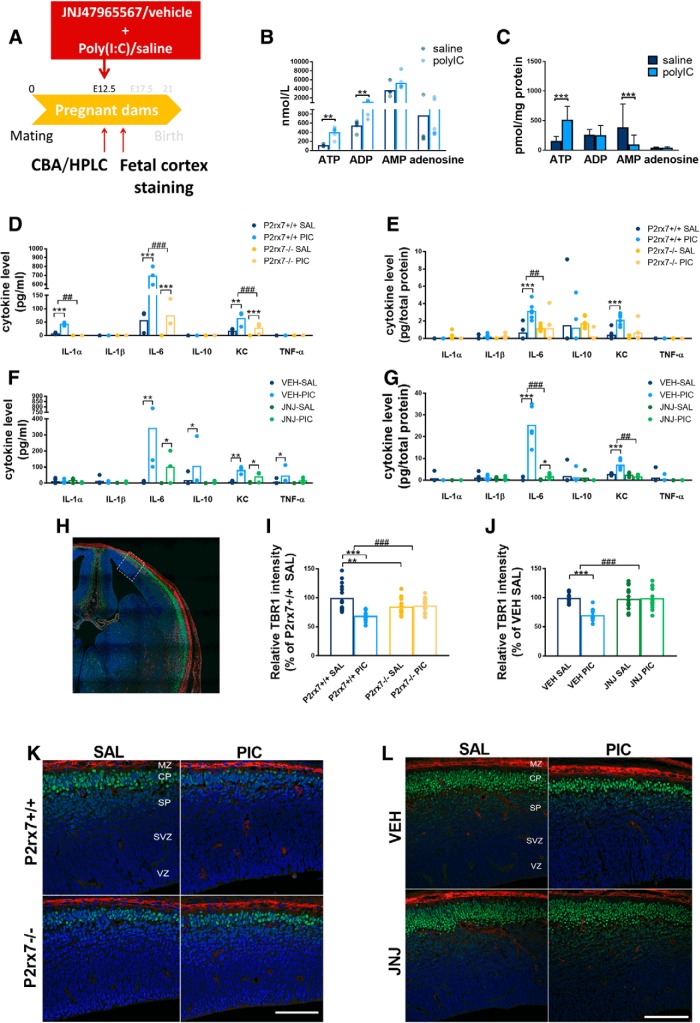

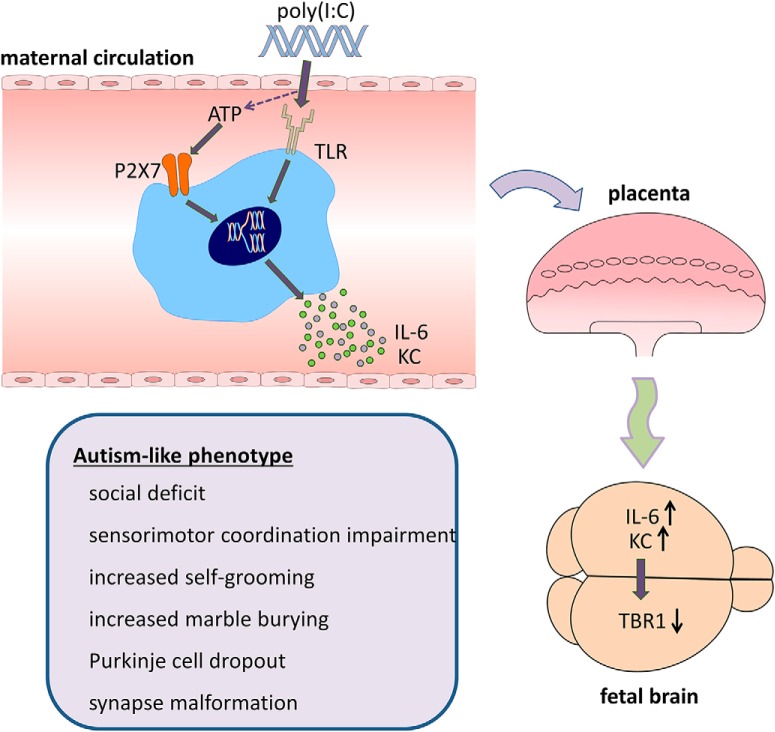

Effect of MIA on maternal and fetal cytokine response, nucleotide levels and on fetal brain development

Next, we examined how MIA altered nucleotide and cytokine levels in maternal plasma and fetal brain using HPLC and multiplex fluorescent bead array analyses, respectively (Experiment 2). Fetal brain samples and maternal plasma were collected 2 h after a single intraperitoneal injection of poly(I:C) (3 mg/kg). At this time point, increased ATP and ADP levels were detected in P2rx7+/+ maternal plasma (Fig. 2B), and elevated ATP levels could also be measured in fetal brains, whereas AMP decreased (Fig. 2C). In response to MIA, strong IL-6 induction was detected in P2rx7+/+ mice, which was attenuated in P2rx7−/− mice (Fig. 2D). A similar, although lower, magnitude of statistically significant increase in IL-6 levels was also observed in fetal brain of P2rx7+/+ mice, which was not detected in poly(I:C)-treated P2rx7−/− samples (Fig. 2E). There was a significant increase of IL-1α and KC in P2rx7+/+ maternal plasma after poly(I:C) treatment, which was also attenuated in P2rx7-deficient mice (Fig. 2D). KC was also induced by MIA in fetal brain of P2rx7+/+, but not P2rx7−/− mice (Fig. 2E). IL-1β, TNFα, IL-10, and IL-1α remained below detection limit in maternal plasma in both genotypes (Fig. 2D). Likewise, only insignificant and genotype-independent changes were observed in IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-10 levels in fetal brain and TNFα remained undetectable (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Poly(I:C)-induced nucleotide and cytokine levels in maternal plasma and fetal brain and effect on fetal brain development. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 2). B, C, MIA increased ATP and ADP levels in P2rx7+/+ maternal plasma, whereas in fetal brain, higher ATP, but decreased AMP levels were detected. D, E, IL-6 was induced in maternal blood after PIC treatment in P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− mice; however, the induction was substantially ameliorated in P2rx7−/− mice. y axis is interrupted to increase visibility of results. IL-1α and KC levels also showed significant elevation subsequent to MIA. In fetal brain, IL-6 and KC were also induced significantly, although moderately. F, G, PIC induced upregulation of IL-6, and KC is attenuated in maternal plasma and fetal brain of P2rx7+/+ mice by pretreatment with the selective P2rx7 antagonist JNJ47965567. Cytokine values measured in the plasma are expressed in picograms per milliliter, and in the fetal brains as picograms per total protein, and they were logarithmically transformed before statistical analyses. Figures show original dataset. Exact n, F, and p values are provided in Table 1. H, Representative stitched image of the fetal brain. White rectangle represents the location of images presented in I and K. K, L, MIA decreased the intensity of TBR1 immunoreactivity in the developing (E14.5) cortical plate of WT mouse fetuses, but this effect was absent in KO mice. J, L, Maternal JNJ47965567 pretreatment prevented poly(I:C)-triggered damage of TBR1-labeled cells. MZ, Marginal zone; CP, cortical plate; SP, subplate; SVZ, subventricular zone; VZ, ventricular zone. Blue represents Hoechst 33342. Red represents SATB2. Green represents TBR1. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 15 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA ##p < 0.01. ###p < 0.001.

Next, we asked how the P2rx7 gene deletion interacted with disrupted fetal brain development and TBR1 and SATB2 expressions were examined following MIA in both genotypes. Eighteen fetal brain samples were immunostained for TBR1 and SATB2, 48 h (E14.5) after poly(I:C) treatment (3 mg/kg on E12.5). Whereas no visible change was observed in SATB2 staining, a weaker intensity of TBR1 immunofluorescence was detected in the developing cortical plate of P2rx7+/+ mice subjected to MIA, indicating the disruption of cortical development (Fig. 2I,K). In contrast, this change was not observed in P2rx7−/− mice (Fig. 2I,K).

Maternal P2rx7 inhibition reproduces the effect of gene deficiency on MIA-induced phenotype in WT mice

In Experiment 3, we determined whether maternal P2rx7 receptors are instrumental for converting MIA to autistic phenotypic alterations in offspring. A single injection of the potent and selective P2rx7 antagonist (JNJ47965567, 30 mg/kg i.p.) or its vehicle was administered to pregnant WT dams 2 h before the respective saline/poly(I:C) administration on E12.5 and E17.5 and the experiment was continued as described for Experiment 1 (Fig. 3A). The effect of maternal poly(I:C) treatment was similar in vehicle-treated offspring compared with saline-treated offspring in Experiment 1, and all features of the autistic phenotype were observed: that is, social deficit (Fig. 3B), impairment of sensorimotor coordination (Fig. 3C,D), increase in repetitive behaviors in self-grooming (Fig. 3E) and marble burying tests (Fig. 3F), dropout of cerebellar Purkinje neurons (Fig. 3G,I), and synaptosome destruction (Fig. 3H,J). Notably, maternal JNJ47965567 treatment, by itself, did not have any significant effect on behavior. In contrast, P2rx7 antagonist treatment alleviated the poly(I:C) effect in social preference (Fig. 3B), rotarod (Fig. 3C,D), self-grooming (Fig. 3E), and marble burying tests (Fig. 3F) compared with an identical treatment with vehicle. Interestingly, poly(I:C)-induced loss of Purkinje cells (Fig. 3G, I) and increased synaptosome malformation (Fig. 3H,J) did not occur after JNJ47965567 treatment either.

To cross-validate the effect of genetic deficiency and maternal blockade of P2rx7s, identical P2rx7 antagonist/vehicle treatment was administered to pregnant P2rx7−/− dams (Experiment 4; Fig. 4A). We could not observe any aspects of poly(I:C)-induced autistic phenotype under these conditions (Fig. 4B–J).

These results indicated that maternal P2rx7s are essential for autistic phenotype alterations in offspring. To identify the underlying molecular signaling machinery, we investigated whether maternal P2rx7 antagonist treatment reproduced the effect of genetic deletion on maternal plasma and fetal brain cytokine profiles (Fig. 2F,G). The significant induction of IL-6 in maternal plasma (Fig. 2F) and fetal brain (Fig. 2G) by maternal poly(I:C) treatment was attenuated by pretreatment with P2rx7 antagonist JNJ47965567 (30 mg/kg i.p. 2 h before poly(I:C)), compared with vehicle (Fig. 2F,G). Furthermore, maternal JNJ4796556 prevented the poly(I:C)-induced loss of TBR1 intensity in the developing cortical plate (Fig. 2J,L).

Endogenous activation of P2rx7 is sufficient to elicit autistic changes in WT offspring

Single administration of P2rx7 agonist ATP (400 μm) elevated the nucleotide levels in the maternal plasma (Fig. 5B) and fetal brain (Fig. 5C) after ATP administration. ATP treatment resulted in similar behavioral and morphological alterations observed in poly(I:C)-induced MIA model (Experiment 5). In the offspring of WT dams, social impairment (Fig. 5D), excessive self-grooming (Fig. 5F), and motor coordination deficit (Fig. 5E,F) appeared, accompanied by Purkinje cell loss in the cerebellum (Fig. 5I,K) and higher ratio of malformed synaptosomes in the whole brain (Fig. 5J,L). In P2rx7-deficient mice, ATP did not trigger any of these features, confirming the instrumental role of P2rx7 in the mechanism leading to an autism-like condition.

Figure 5.

Endogenous activation of P2rx7 via ATP is sufficient to elicit autistic changes in WT offspring. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 8). B, Elevated nucleotide levels in maternal plasma and fetal brains (C) after intraperitoneal injection of 400 μm ATP to mouse dams can activate P2rx7. D, Single ATP injection induced behavioral alterations in WT offspring, but not in P2rx7−/− offspring, in social preference test, in rotarod test (E, F), and in the self-grooming test (G). H, In the marble burying test, we did not find significant difference between the groups. ATP administration triggered a decrease in Purkinje cells (I), also visible in the representative cerebellar images (K). Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 14–23 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. J, Abnormal synaptosome structure was more typical in ATP-treated WTs. L, Representative EM image of synaptosomes. Asterisk indicates malformed. Arrows indicate normal synapses. Scale bar, 500 nm. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA ##p < 0.01. ###p < 0.001.

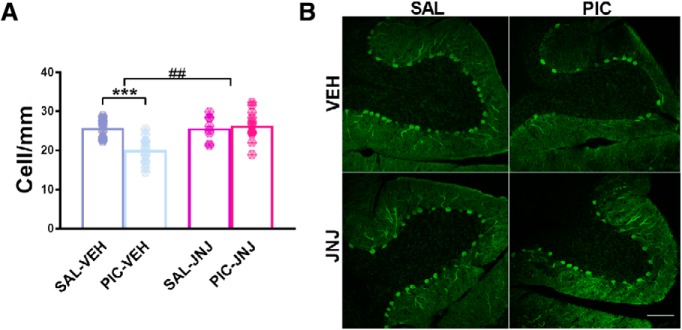

Postnatal P2rx7 inhibition reverses MIA-induced behavioral and histological alterations in WT, but not P2rx7-deficient offspring

The effect of postnatal P2rx7 antagonist treatment on maternal poly(I:C)-induced autistic phenotype in P2rx7+/+ offspring was examined to determine whether persistent behavior changes are reversible by P2rx7s inhibition (Experiment 6). JNJ47965567 (30 mg/kg i.p.) or its vehicle was administered as a single treatment before the first behavior test (Fig. 6A). Postnatal vehicle treatment had no effect on social deficit (Fig. 6B), sensorimotor coordination (Fig. 6C, D), increase in self-grooming (Fig. 6E) and marble burying behaviors (Fig. 6F), atrophy of cerebellar Purkinje cells (Fig. 6G,I), and destruction of synapses (Fig. 6H,J) elicited by maternal poly(I:C) administration. Furthermore, postnatal P2rx7 antagonist treatment did not affect the phenotype in the lack of maternal poly(I:C) treatment (Fig. 6B–J). In contrast, all poly(I:C)-induced alterations were reversed by postnatal treatment with JNJ47965567 (Fig. 6B–J).

Figure 6.

Postnatal inhibition of P2rx7s in the MIA model. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 5). B, Postnatal antagonist treatment reversed poly(I:C) effects on social interaction, (C,D) motor coordination, and (E,F) repetitive behaviors. G, I, Cerebellar Purkinje cell dropout was absent in lobule VII after JNJ47965567 treatment. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 9–19 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. H, J, Synaptic defects were alleviated by the antagonist, malformed (asterisk) and intact (arrows) synapses indicated. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA #p < 0.05. ##p < 0.01. ###p < 0.001.

The loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells and its reversal by the antagonist was not due to the alterations in subsequent behavior experiments as Purkinje cell loss was observed on young adult offspring of poly(I:C)-treated P2rx7+/+ dams without preceding behavior tests and JNJ47965567 (30 mg/kg i.p.) treatment reversed this change as well (Experiment 7; Fig. 7). Once again, we cross-validated the effect of gene deficiency with the effect of postnatal P2rx7 antagonist treatment, but no maternal poly(I:C)-induced autistic phenotype was observed in offspring of P2rx7−/− mice either after vehicle or P2rx7 antagonist treatment (Experiment 8; Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Postnatal treatment of P2rx7+/+ offspring with JNJ47965567 without behavior tests affecting cerebellar Purkinje cell dropout. Eight-week-old P2rx7+/+ animals received a single intraperitoneal JNJ47965567 (30 mg/kg) injection and, after 3 weeks, were killed. A, Calbindin immunolabeling of Purkinje cells revealed similar cell number as in the vehicle controls; therefore, the loss of cells could not be due to subsequent behavior tests, thus supporting the findings of Figure 4G. B, Representative images of calbindin-labeled Purkinje cells in lobule VII of the cerebellum. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 7–18 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA ##p < 0.01.

Figure 8.

The P2rx7−/− phenotype was not affected in the MIA model by postnatal administration of selective P2X7 antagonist JNJ47965567 (JNJ, 30 mg/kg i.p., 2 h before the first behavior test) in the offspring. A, Overview of the experimental protocol (Experiment 7). JNJ pretreatment had no influence on the social behavior (B), motor coordination deficits (C, D), and repetitive behaviors (E, F). G, The number of Purkinje cells was not altered in offspring after the pharmacological blockade of P2rx7s in MIA. H, Synaptosome malformation was not affected by the antagonist treatment in the offspring. Exact n and p values are provided in Table 1. I, Representative images of calbindin-labeled Purkinje cells in lobule VII of the cerebellum. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 11–15 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. J, Representative EM image of synaptosomes. Asterisk indicates malformed synaptosome. Arrows indicate unharmed synapses. Scale bar, 500 nm. *p < 0.05.

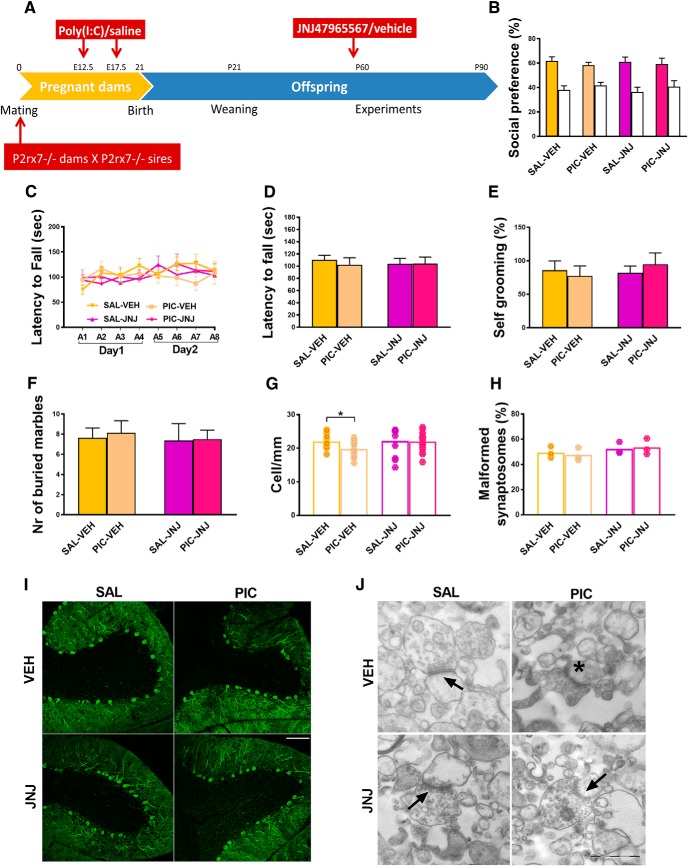

P2rx7+/− heterozygous offspring are not affected by poly(I:C) administration

In Experiment 9, we showed that both maternal and paternal P2rx7+/+ alleles are necessary to induce MIA in offspring. After cross-breeding P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− mice, the heterozygous offspring resembled the P2rx7−/− phenotype regardless of maternal or paternal origin of the allele deficiency. Social preference was not observed in any of the groups (Fig. 9B), neither exaggerated repetitive behaviors (Fig. 9E,F) nor impaired sensorimotor skills (Fig. 9C, D). In addition to behavioral analyses, also the morphological alterations were investigated; however, cerebellar Purkinje cell numbers (Fig. 9G, I) and condition of synaptosomes (Fig. 9H, J) were not affected by poly(I:C) administration or parental genotype.

Figure 9.

Heterozygous offspring are not affected by poly(I:C) administration. Cross-breeding the P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− genotypes resulted in an anti-autistic phenotype of heterozygotes, similar to the P2rx7−/− phenotype. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 9). Poly(I:C) could not induce MIA and social preference (B), aberrant motor coordination (C, D), or increased repetitive behaviors (E, F) in the offspring regardless of parental origin of P2rx7. G, Purkinje cells were unharmed in heterozygotes. I, Representative images of calbindin-labeled cells in the cerebellum. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data show 22–24 technical replicates in n = 3 animals. H, Synaptosome preparations did not reveal any difference in heterozygotes. J, Representative EM synaptosome images. Arrows indicate intact synaptosomes. Asterisks label malformed synaptosome. Scale bar, 500 nm. *p < 0.05.

We also examined cytokine levels in this experimental condition (Experiment 10; Fig. 10A), showing that in maternal plasma MIA is able to induce IL-6 and KC production (Fig. 10B) similarly to Experiment 2, both in P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− dams, but less intensely in the latter group. Also, in the plasma samples, we could measure moderately elevated IL-10 level and TNF-α induction in both genotypes as well. However, in the heterozygous fetal brain samples, we could detect only a much smaller increase of IL-6, whereas other cytokine concentrations remained around the detection limit (Fig. 10C), again displaying the phenotype obtained in P2rx7−/− offspring.

Figure 10.

Cytokines are barely induced by poly(I:C) in fetal brains of homozygous offspring; only IL-6 shows a small increase, whereas maternal plasma levels are triggered as in original WT and KO comparison. A, Experimental protocol (Experiment 10). B, MIA triggered IL-6, KC, and TNF-α in the plasma of both P2rx7+/+ and P2rx7−/− dams, with a more robust elevation in the WTs. IL-10 levels are significantly higher in P2rx7+/+ dams. y axis is interrupted to increase visibility of results. However, (C) this remarkable induction by poly(I:C) is not transferred to the fetal brains of heterozygous offspring; all values stay close to the detection limit, although in the case of IL-6 concentrations, we could find significant difference in both treated groups. Cytokine values measured in the plasma are expressed in picograms per milliliter, and in the fetal brains as picograms per total protein, and they were logarithmically transformed before statistical analyses. Figures show original dataset. Exact n, F, and p values are provided in Table 1. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ANOVA #p < 0.05. ##p < 0.01.

Discussion

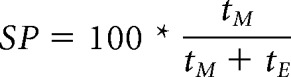

Here we show the pivotal role of P2rx7s in the poly(I:C)-induced MIA model of ASD (Fig. 11). P2rx7s and downstream signaling pathways coupled to them are common signaling highways in the pathological nervous system; their involvement has been shown previously in animal models of psychiatric disorders (Cheffer et al., 2018), such as major depression, bipolar disorder (Basso et al., 2009; Csölle et al., 2013a, b), schizophrenia (Koványi et al., 2016), but not in ASD models. The experimental proof for endogenous P2rx7s participation in MIA-induced behavioral and morphological changes in the offspring are as follows: (1) In P2rx7−/− mice, maternal poly(I:C) did not induce social deficit, sensorimotor impairment, repetitive behaviors; in addition, cerebellar Purkinje cell atrophy and synaptosome destruction were also absent or alleviated. Genetic disruption by itself elicited baseline changes in some offspring phenotypes (e.g., decreased social preference, moderate, but significant Purkinje cell loss), and increased proportion of malformed synaptosomes. However, these are probably related to permanent deficiency of P2rx7s and consequent developmental changes as we could not reproduce them acutely with either maternal or offspring P2rx7 antagonist treatment. Similar socio-communicative and sensorimotor impairment and autistic-like phenotype were observed in another genetic mouse model affecting purinergic signaling (i.e., in mice genetically deficient in P2X4 receptors) (Wyatt et al., 2013). Baseline phenotype of P2rx7−/− mice has been extensively analyzed in previous studies: altered stress reactivity, but no change in basal locomotor activity, was observed in different studies (Basso et al., 2009; Csölle et al., 2013b; Bartlett et al., 2014; Otrokocsi et al., 2017) in agreement with the present study (Fig. 1G). These findings indicate that the lack of responsiveness of P2rx7−/− offspring to MIA is probably not due to a “ceiling effect” of genetic disruption. (2) The effect of permanent knockdown of P2rx7 on poly(I:C)-induced changes could be mimicked by acute blockade of P2rx7s with specific P2rx7s antagonist on WT mice. It has been shown that JNJ47965567 has a selective action on P2rx7 in vitro and reaches high target engagement in vivo both in the systemic circulation and in the brain (Bhattacharya et al., 2013). (3) The above protective effects of JNJ47965567 could be observed in P2rx7+/+, but not in P2rx7−/− littermates, showing that the effect of P2rx7 antagonist is specifically related to P2rx7 inhibition. (4) We demonstrated the instrumental role of P2rx7 in the process leading to autism-like condition via triggering behavioral and morphological alterations by the endogenous activation of P2rx7 during pregnancy. A single ATP injection resulted in similar autistic features observed in poly(I:C)-induced MIA model; therefore, the activation of P2rx7 is not only necessary, but sufficient, to induce autistic phenotype in WT mice. P2rx7-deficient mice were not affected by ATP administration, further strengthening our hypothesis. (5) Heterozygous offspring resemble P2rx7−/− phenotype; therefore, P2rx7 needs to be present in both parents to elicit MIA-induced autistic features in offpsring.

Figure 11.

Autism-like phenotype develops via P2rx7-mediated MIA. Poly(I:C) injections induce maternal immune mediators, such as IL-6 and KC through increasing extracellular ATP concentrations activating P2rx7s. This triggers elevation of IL-6 and KC in the fetal brain and compromises the development of cortex reflected in the reduced level of the transcription factor TBR1 protein. Autistic features, such as social deficit, disturbed sensorimotor coordination, excessive repetitive behaviors, loss of cerebellar Purkinje neurons, and abnormal synaptosome structure, could be detected in the adult WT offspring, whereas P2rx7−/− mice or WT offspring receiving maternal P2xr7 antagonist treatment did not display similar phenotype. Our hypothesis is confirmed by results of Experiment 8, where ATP administration alone could elicit autistic phenotype in offspring via P2rx7 activation.

We have examined the potential underlying mechanism of the anti-autistic effect of genetic/pharmacologic disruption of P2rx7s. At first, we demonstrated the elevation of ATP level in maternal blood and fetal brain, a prerequisite of endogenous P2rx7 activation 2 h after the first poly(I:C) treatment. Because P2rx7s are involved in regulating circulating cytokine production, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 following primary inflammatory stimuli (Solle et al., 2001; Bartlett et al., 2014), it was also worthwhile to examine an array of cytokines at the same time point. As expected, a strong induction of IL-6 was observed in maternal circulation of P2rx7+/+ mice, which was attenuated by both genetic deletion and maternal inhibition of P2rx7s. Because maternal IL-6 is sufficient to induce autistic phenotype in offspring (Samuelsson et al., 2006; Hsiao and Patterson, 2011), maternal IL-6 is a likely mediator of the effect of endogenous P2rx7 activation upon maternal poly(I:C)-induced challenge. The action could be either direct, through the placenta (Wu et al., 2017), or indirect, through downstream Th17 cytokines, such as IL-17a, as described in other studies (Choi et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017; Shin Yim et al., 2017). Interestingly, we could not detect significant change in IL-1β levels in response to MIA in either P2rx7+/+ or P2rx7−/− animals, which argues against the activation of the canonical P2rx7-IL-1β-NLRP3 signaling pathway, at least at this early time point. Consistently, maternal P2rx7 inhibition, but not IL-1β blockade, was effective to prevent preterm birth and neonatal brain injury in a mouse model of perinatal intrauterine inflammation (Tsimis et al., 2017). Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that at later time points other cytokines and soluble mediators also participated in maternal and fetal response to poly(I:C)-induced endogenous P2rx7 activation.

We also show here that, 48 h after poly(I:C) injection, TBR1 immunolabeling is decreased in the developing cortical plate of WTs, demonstrating compromised brain development following MIA under our experimental conditions. Importantly, in P2rx7−/− mice, or after maternal P2rx7 antagonist treatment, no significant decrease is observed in response to poly(I:C), illustrating the impact of P2rx7 inhibition on MIA-induced alterations in brain development. TBR1 is a transcription factor protein expressed by developing glutamatergic projection neurons with a critical role in neuronal migration and axonal pathfinding in the cortex, and is a high-confidence risk gene for ASD (Deriziotis et al., 2014; Huang and Hsueh, 2015). There are several mechanisms whereby TBR1 loss might influence developing neuronal circuits, and it also acts as a master gene controlling the expression of many other ASD-associated genes (Huang and Hsueh, 2015). TBR1+/− mice exhibit autism-like behaviors (Huang et al., 2014); therefore, it is a plausible explanation that MIA leads to similar behaviors through TBR1 depletion. In contrast, we could not observe change in SATB2 immunofluorescence, another transcription factor instrumental for normal brain development, which is the marker of postmitotic neurons in superficial cortical layers (Alcamo et al., 2008).

Finally, we demonstrated the reversal of MIA-induced behavioral and morphological phenotype by JNJ47965567 treatment in offspring. This finding implies that offspring phenotypic alterations developed as a result of the long-term impact of MIA are reversible by P2rx7 inhibition. Interestingly, there were minor differences in the effects of JNJ depending on the application protocols. This holds true for the sensorimotor coordination impairments (Figs. 3C, D, 6C, D), marble burying test (Figs. 3F, 6F), and synaptosome malformation analyses (Figs. 3H, H), where there are small, but significant, differences in case of the maternal JNJ administration, which is not detected when JNJ was administered postnatally, although P2rx7 antagonist injection to either pregnant dams or adult offspring counteracted the poly(I:C)-induced changes. Overall, the pharmacological blockade of P2rx7 with JNJ seems efficient in alleviating all of the features of poly(I:C)-induced autism in mice; however, the mechanisms following receptor inhibition could possibly be diverse, whether acting in the maternal organism or in the adult offspring, which might be responsible for differences mentioned above.

As for the potential mechanism of effect of postnatal P2rx7 blockade, it is known that the cerebellum remains plastic even after weeks/month after birth (Wang and Zoghbi, 2001). Probably prenatal poly(I:C) treatment induced such mechanisms that would have resulted in Purkinje cell loss only at the young adult age, when JNJ was administered; therefore, the antagonist could alleviate this effect. Furthermore, our observation on the reversal of Purkinje cell loss after postnatal antipurinergic treatment is not unique. J.C. Naviaux et al. (2014) demonstrated that a single-dose administration of the nonselective P2 receptor antagonist suramin corrected abnormal behaviors and Purkinje cell loss in adult mice in a similar MIA model of autism. Moreover, the alleviation of autistic symptoms by postnatal suramin administration has also been observed in a small human study (R.K. Naviaux et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, identifying the exact cell types and mechanisms responsible for the beneficial action of postnatal P2rx7 blockade awaits further investigation.

In conclusion, we discovered that activation of P2rx7s is necessary to transduce MIA to an autistic phenotype in offspring and that both behavioral and morphological alterations could be reversed by pharmacological inhibition of either maternal or offspring P2rx7s. In addition, direct P2rx7 activation alone is sufficient to elicit autistic phenotype in WT mice. Endogenous P2rx7 activation might disrupt cortical development and elicit phenotypic changes via proinflammatory cytokines in the ASD model. Consequently, maternal and offspring P2rx7s function as triggers to turn on and off immune activation and subsequent perinatal brain reprogramming elicited by poly(I:C), which could be used as diagnostic and/or therapeutic intervention target for the precision treatment of ASD.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Hungarian Research and Development Fund Grant K116654 to B.S., Hungarian Brain Research Program 2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002 to B.S., and Gedeon Richter plc. RG-IPI-2016-TP10-0012 and the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement 766124. We thank Attila Köfalvi for guidance in synaptosome preparation, Flóra Gölöncsér and Bernadett Varga for technical assistance, the Nikon Microscopy Center, and Cell Biology Center (Flow Cytometry Core Facility), Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Budapest, Hungary) for assistance in cytometric bead array analyses.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adinolfi E, Giuliani AL, De Marchi E, Pegoraro A, Orioli E, Di Virgilio F (2018) The P2X7 receptor: a main player in inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol 151:234–244. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo EA, Chirivella L, Dautzenberg M, Dobreva G, Fariñas I, Grosschedl R, McConnell SK (2008) Satb2 regulates callosal projection neuron identity in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuron 57:364–377. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R, Stokes L, Sluyter R (2014) The P2X7 receptor channel: recent developments and the use of P2X7 antagonists in models of disease. Pharmacol Rev 66:638–675. 10.1124/pr.113.008003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso AM, Bratcher NA, Harris RR, Jarvis MF, Decker MW, Rueter LE (2009) Behavioral profile of P2X7 receptor knockout mice in animal models of depression and anxiety: relevance for neuropsychiatric disorders. Behav Brain Res 198:83–90. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A. (2018) Recent advances in CNS P2X7 physiology and pharmacology: focus on neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Pharmacol 9:30. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Wang Q, Ao H, Shoblock JR, Lord B, Aluisio L, Fraser I, Nepomuceno D, Neff RA, Welty N, Lovenberg TW, Bonaventure P, Wickenden AD, Letavic MA (2013) Pharmacological characterization of a novel centrally permeable P2X7 receptor antagonist: JNJ-47965567. Br J Pharmacol 170:624–640. 10.1111/bph.12314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Careaga M, Murai T, Bauman MD (2017) Maternal immune activation and autism spectrum disorder: from rodents to nonhuman and human primates. Biol Psychiatry 81:391–401. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KZ, Dale VQ, Dénes A, Bennett G, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM, McColl BW (2009) A rapid and transient peripheral inflammatory response precedes brain inflammation after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29:1764–1768. 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charan J, Kantharia ND (2013) How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J Pharmacol Pharmacother 4:303–306. 10.4103/0976-500X.119726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheffer A, Castillo AR, Corrêa-Velloso J, Goncalves MC, Naaldijk Y, Nascimento IC, Burnstock G, Ulrich H (2018) Purinergic system in psychiatric diseases. Mol Psychiatry 23:94–106. 10.1038/mp.2017.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H, Kim S, Kim H, Kim SV, Hoeffer CA, Littman DR, Huh JR (2016) The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 351:933–939. 10.1126/science.aad0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csölle C, Baranyi M, Zsilla G, Kittel A, Gölöncsér F, Illes P, Papp E, Vizi ES, Sperlágh B (2013a) Neurochemical changes in the mouse hippocampus underlying the antidepressant effect of genetic deletion of P2X7 receptors. PLoS One 8:e66547. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csölle C, Andó RD, Kittel Á, Gölöncsér F, Baranyi M, Soproni K, Zelena D, Haller J, Németh T, Mócsai A, Sperlágh B (2013b) The absence of P2X7 receptors (P2rx7) on non-haematopoietic cells leads to selective alteration in mood-related behaviour with dysregulated gene expression and stress reactivity in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16:213–233. 10.1017/S1461145711001933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dénes A, Humphreys N, Lane TE, Grencis R, Rothwell N (2010) Chronic systemic infection exacerbates ischemic brain damage via a CCL5 (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted)-mediated proinflammatory response in mice. J Neurosci 30:10086–10095. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1227-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deriziotis P, O'Roak BJ, Graham SA, Estruch SB, Dimitropoulou D, Bernier RA, Gerdts J, Shendure J, Eichler EE, Fisher SE (2014) De novo TBR1 mutations in sporadic autism disrupt protein functions. Nat Commun 5:4954. 10.1038/ncomms5954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Torre-Minguela C, Mesa Del Castillo P, Pelegrín P (2017) The NLRP3 and pyrin inflammasomes: implications in the pathophysiology of autoinflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 8:43. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverman BE, Patterson PH (2009) Cytokines and CNS development. Neuron 64:61–78. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes ML, McAllister AK (2015) Immune mediators in the brain and peripheral tissues in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci 16:469–486. 10.1038/nrn3978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes ML, McAllister AK (2016) Maternal immune activation: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 353:772–777. 10.1126/science.aag3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Michalon A, Lindemann L, Fontoura P, Santarelli L (2013) Drug discovery for autism spectrum disorder: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:777–790. 10.1038/nrd4102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao EY, Patterson PH (2011) Activation of the maternal immune system induces endocrine changes in the placenta via IL-6. Brain Behav Immun 25:604–615. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TN, Hsueh YP (2015) Brain-specific transcriptional regulator T-brain-1 controls brain wiring and neuronal activity in autism spectrum disorders. Front Neurosci 9:406. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TN, Chuang HC, Chou WH, Chen CY, Wang HF, Chou SJ, Hsueh YP (2014) Tbr1 haploinsufficiency impairs amygdalar axonal projections and results in cognitive abnormality. Nat Neurosci 17:240–247. 10.1038/nn.3626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HY, Xu LL, Shao L, Xia RM, Yu ZH, Ling ZX, Yang F, Deng M, Ruan B (2016) Maternal infection during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 58:165–172. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Croen LA, Yoshida CK, Heuer L, Hansen R, Zerbo O, DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Yolken R, Ashwood P, Van de Water J (2017) Autism with intellectual disability is associated with increased levels of maternal cytokines and chemokines during gestation. Mol Psychiatry 22:273–279. 10.1038/mp.2016.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim H, Yim YS, Ha S, Atarashi K, Tan TG, Longman RS, Honda K, Littman DR, Choi GB, Huh JR (2017) Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature 549:528–532. 10.1038/nature23910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuesel I, Chicha L, Britschgi M, Schobel SA, Bodmer M, Hellings JA, Toovey S, Prinssen EP (2014) Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 10:643–660. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köfalvi A, Vizi ES, Ledent C, Sperlágh B (2003) Cannabinoids inhibit the release of [3H]glutamate from rodent hippocampal synaptosomes via a novel CB1 receptor-independent action. Eur J Neurosci 18:1973–1978. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koványi B, Csölle C, Calovi S, Hanuska A, Kató E, Köles L, Bhattacharya A, Haller J, Sperlágh B (2016) The role of P2X7 receptors in a rodent PCP-induced schizophrenia model. Sci Rep 6:36680. 10.1038/srep36680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyzar E, Gaikwad S, Roth A, Green J, Pham M, Stewart A, Liang Y, Kobla V, Kalueff AV (2011) Towards high-throughput phenotyping of complex patterned behaviors in rodents: focus on mouse self-grooming and its sequencing. Behav Brain Res 225:426–431. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkova NV, Yu CZ, Hsiao EY, Moore MJ, Patterson PH (2012) Maternal immune activation yields offspring displaying mouse versions of the three core symptoms of autism. Brain Behav Immun 26:607–616. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi A, Quintana DS, Glozier N, Lloyd AR, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ (2015) Cytokine aberrations in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 20:440–446. 10.1038/mp.2014.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U. (2014) Prenatal poly(i:C) exposure and other developmental immune activation models in rodent systems. Biol Psychiatry 75:307–315. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]