Abstract

Background

The efficacy of dexamethasone in extending the duration of local anaesthetic block is uncertain. In a randomised controlled triple blind crossover study in volunteers, we tested the hypothesis that neither i.v. nor perineurally administered dexamethasone prolongs the sensory block achieved with ropivacaine.

Methods

Ultrasound-guided ulnar nerve blocks (ropivacaine 0.75% wt/vol, 3 ml, with saline 1 ml with or without dexamethasone 4 mg) were performed on three occasions in 24 male volunteers along with an i.v. injection of saline 1 ml with or without dexamethasone 4 mg. The combinations of saline and dexamethasone were as follows: control group, perineural and i.v. saline; perineural group, perineural dexamethasone and i.v. saline; i.v. group, perineural saline and i.v. dexamethasone. Sensory block was measured using a VAS in response to pinprick testing. The duration of sensory block was the primary outcome and time to onset of sensory block the secondary outcome.

Results

All 24 subjects completed the trial. The median [inter-quartile range (IQR)] duration of sensory block was 6.87 (5.85–7.62) h in the control group, 7.37 (5.78–7.93) h in the perineural group and 7.37 (6.10–7.97) h in the i.v. group (P=0.61). There was also no significant difference in block onset time between the three groups.

Conclusion

Dexamethasone 4 mg has no clinically relevant effect on the duration of sensory block provided by ropivacaine applied to the ulnar nerve.

Clinical trial registration

DRKS, 00014604; EudraCT, 2018-001221-98.

Keywords: dexamethasone, local anaesthetics, regional anaesthesia, ropivacaine, ulnar nerve block, ultrasound-guided

Editor's key points.

-

•

The efficacy of perineural or systemic dexamethasone in combination with local anaesthetic in peripheral nerve block is unclear despite seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses due to the low quality and heterogeneity of included studies.

-

•

A randomised, triple-blinded crossover-study in volunteers was conducted to evaluate the pharmacodynamic effects of dexamethasone as an additive to ropivacaine in a standardised ulnar nerve block.

-

•

Dexamethasone 4 mg had no clinically relevant effect on the onset or duration of sensory block by ropivacaine at the ulnar nerve.

The ideal agent for peripheral regional anaesthesia would provide sensory and motor block during the surgical procedure followed by prolonged sensory block, with return of motor function in the postoperative period. The absence of local anaesthetics with these optimal pharmacodynamic properties has prompted investigation of drugs that can be administered with local anaesthetics to prolong the duration of peripheral nerve blockade. Dexamethasone, a synthetic corticosteroid, is currently one of the most interesting and investigated of such adjuvant drugs.

The efficacy of dexamethasone administered perineurally or systemically in combination with local anaesthetic peripheral nerve block was recently evaluated in seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses with varying results.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 It was suggested that dexamethasone may have a small effect to increase the duration of peripheral regional blocks, but this may apply only when the local anaesthetic solution contains epinephrine.7 We suggested that the low quality of the trials included in the meta-analyses and the heterogeneity between them (different local anaesthetics, with or without epinephrine, different doses of dexamethasone, different blocks, etc.) meant that no reliable conclusions could be drawn regarding the efficacy of perineural dexamethasone in combination with local anaesthetics.8

Volunteer studies are well established for investigating the pharmacodynamic characteristics of drugs that can be used for regional anaesthetic purposes.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 The paradigm has the advantage of motivated study subjects which aids in the precision of determining the effects of the regional block. We therefore designed a randomised, triple-blinded crossover study in volunteers to evaluate the pharmacodynamic effects of dexamethasone as an additive to ropivacaine in a standardised peripheral nerve block.

Methods

Trial authorisation

We obtained approval of the study protocol from the institutional review board (ethics commission) at the Medical University of Vienna (ref. 1381/2018) and registered the study in the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT, ref. 2018-001221-98) and the German Clinical Trial Register (DRKS, ref. 00014604).

Subjects

We recruited male volunteers aged 18–55 yr with BMI 18–35 kg m−2 to receive ultrasound-guided ulnar nerve blockade on three different days. The volunteers were recruited via the Department of Clinical Pharmacology of the Medical University of Vienna and paid according to the legal standards for payment of volunteers for clinical studies. Exclusion criteria were hypersensitivity or allergy to the study drugs or poor visibility of the ulnar nerve upon ultrasound at the projected puncture site.

Ulnar nerve blockade

All ulnar nerve blocks were performed on the non-dominant side. The ulnar nerve was seen using ultrasound (SonoSite X-Port™, Fujufilm SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) below the level of the sulcus of the ulnar nerve and proximal to where the ulnar artery joins the nerve, between the flexor carpi ulnaris, humeroulnar head of the superficial flexor digitorum and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. At this site, the ulnar nerve appears typically as a triangular structure (Fig. 1). After insertion of a cannula (Venflon®) with a switch-valve into an antecubital vein (contralateral to the nerve block), the skin at and around the puncture site was prepared in a surgical sterile manner and a 15–7 MHz linear ultrasound probe was covered with a sterile ultrasound probe cover (SaferSonic Inc., Ybbs, Austria). Sterile ultrasound gel was used as the contact medium between the ultrasound probe and the skin (SaferGel, SaferSonic Inc.). For the nerve block we used 22G 50 mm facette tip needles with an injection line (Polymedic™, te me na, Carrières sur Seine, France). An in-plane ultrasound needle technique was used to position the needle tip adjacent but extra-epineurally to the nerve before administration of study drugs (Fig. 2). All nerve blocks were performed by one investigator (P.M.).

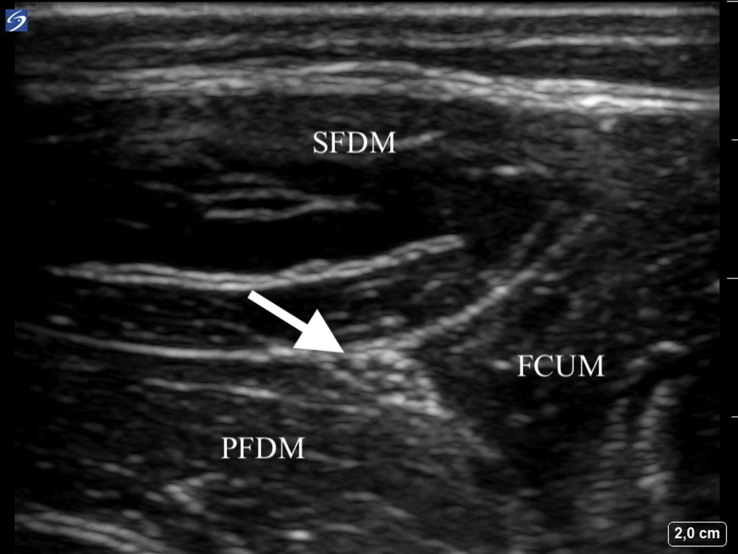

Fig 1.

High-resolution ultrasound image of the anatomical position of the ulnar nerve at the forearm between the superior flexor digitorum muscle (SFDM), profoundus flexor digitorum muscle (PFDM), and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (FCUM). The ulnar nerve (indicated by the arrow) appears at this anatomical position as a triangular structure and was the standardised site of nerve blockade.

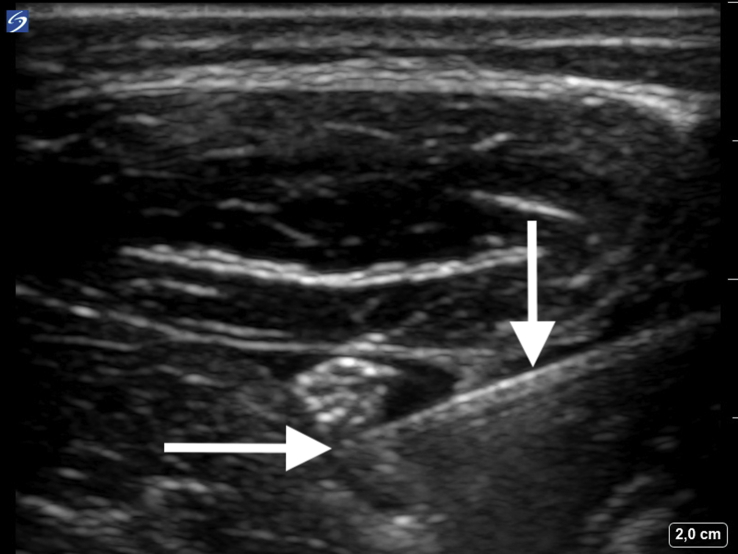

Fig 2.

High-resolution ultrasound image of the ulnar nerve blockade via an in-plane needle guidance technique. The vertical arrow indicates the shaft of the needle and the horizontal arrow indicates the tip of the needle. The administered local anaesthetic (with or without dexamethasone or saline) appears as a hypoechoic area around the hyperechoic nerve.

Study groups and dosing rationale

The control group received perineural ropivacaine 0.75% wt/vol, 3 ml, plus saline 1 ml (=ropivacaine 0.56%) and i.v. saline 1 ml; the perineural group received perineural ropivacaine 0.75%, 3 ml (Naropin™, AstraZeneca Ltd, Wedel, Germany) plus dexamethasone 4 mg (dexamethasone 8 mg per 2 ml, Organon Laboratories Ltd, Cambridge, UK) (=ropivacaine 0.56% wt/vol) and i.v. saline 1 ml; the i.v. group received perineural ropivacaine 0.75%, 3 ml, plus saline 1 ml (=ropivacaine 0.56%) and i.v. dexamethasone 4 mg (=1 ml). The three nerve blocks were performed on three separate days with a minimum interval of 7 days between blocks, corresponding to approximately five times the half-life of dexamethasone and 30 times the half-life of ropivacaine.

Assessment of sensory block

Sensory blockade was assessed using a VAS (0–100 mm) in response to pinprick testing of the hypothenar area in comparison with the contralateral side, with 0 mm indicating no sharp sensation and 100 mm indicating the same sharp sensation as the unblocked limb. Five areas of sensory supply were defined: dorsal, ulnar, and palmar aspects of the side of the hypothenar area, the little finger, and the ulnar side of the ring finger. Testing was performed before the block and then 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 60 min after the block, and thereafter every 60 min. The onset of sensory block was defined as the time when the VAS score to pinprick testing was reduced to ≤10 mm in four of the five areas (see above). The duration of sensory block was defined as the time when the VAS to pinprick testing became ≥20 mm in one of the five areas.

Short bevel needles were used for pinprick testing. The tip of the needle was applied with a force sufficient to indent the skin without puncturing it: this produces a consistent unpleasant sharp sensation when applied to non-blocked areas.15, 16 All sensory tests were performed by two investigators (D.M. and M.R.B.).

Randomisation

Randomisation to study period sequence was done with a block size of 6 using an open access online randomisation generator (www.randomization.com). Two sets (one main set, one backup set) of sealed envelopes with the randomisation number containing information about the sequence of treatment allocation were prepared for each subject and kept throughout the study.

Blinding

The study drugs were prepared in an unlabelled syringe by a study nurse. Immediately after the end of administration of study drugs, the subject was taken to a different room where a physician, unaware of the injected study drugs, performed and recorded the sensory tests to assess block success and duration. Subjects were unaware of the injected study drugs.

Study hypothesis

The null hypothesis was that there were no differences in the duration of sensory block between administration of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone in combination with perineural ropivacaine. The alternative hypothesis was that perineural or i.v. dexamethasone affected the duration of sensory block produced by perineural ropivacaine.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was the duration of sensory block and the secondary outcome was the time to onset of sensory block.

Post-study investigation

Within 1 week of the last study day, volunteers were examined for clinical signs of nerve damage (full recovery of the nerve block) and inflammation or infection of the puncture area.

Power and statistical analysis

A previous study with dexmedetomidine as the additive drug to ropivacaine showed that the duration of sensory blockade was increased from 8.7 to 21.4 h with the largest standard deviation (sd) of 4 h.11 To find a minimum clinically important difference in duration of sensory block of 4 h with at least 80% power, 24 volunteers are required (Bonferroni corrected P=0.017 type 1 error rate for three comparisons) to keep the overall type 1 error rate at <5%.

Results are presented as mean (sd), median [inter-quartile range (IQR)] and count as appropriate. Normality was assessed using histograms, normal probability plots, and the D'Agostino omnibus test. Data were analysed using mixed models with maximum likelihood estimation for repeated measures in a crossover design. This included tests for crossover sequence, treatment, period and treatment by period interactions.

Non-parametric analyses including Friedman analysis were used as appropriate. Bonferroni correction (P<0.017) was applied for three comparisons to keep the overall type 1 error rate at <5%. Significance was defined at P<0.05 (two-sided). Analyses were conducted using PASS 8.0 (NCSS Statistical Software Inc., Kaysville, Utah 84037, United States), Number Cruncher Statistical Systems 12 (NCSS Statistical Software Inc., Kaysville, Utah 84037, United States) and StatXact 9 (Cytel Inc., Cambridge, MA 02139, United States).

Results

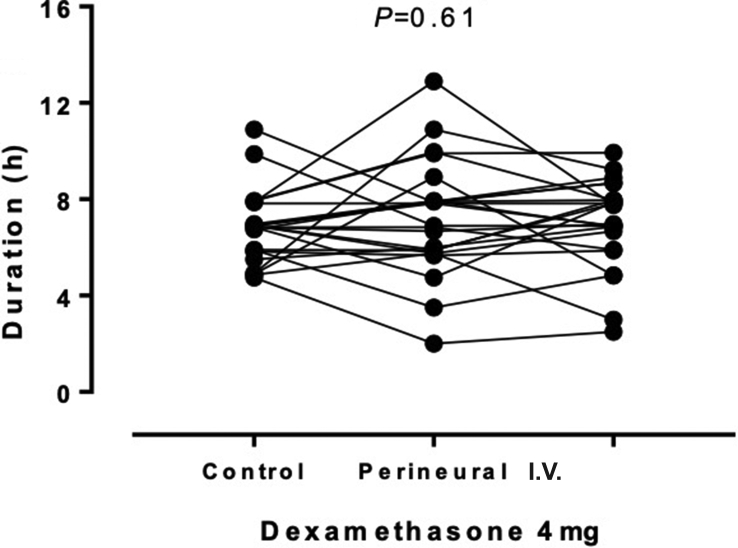

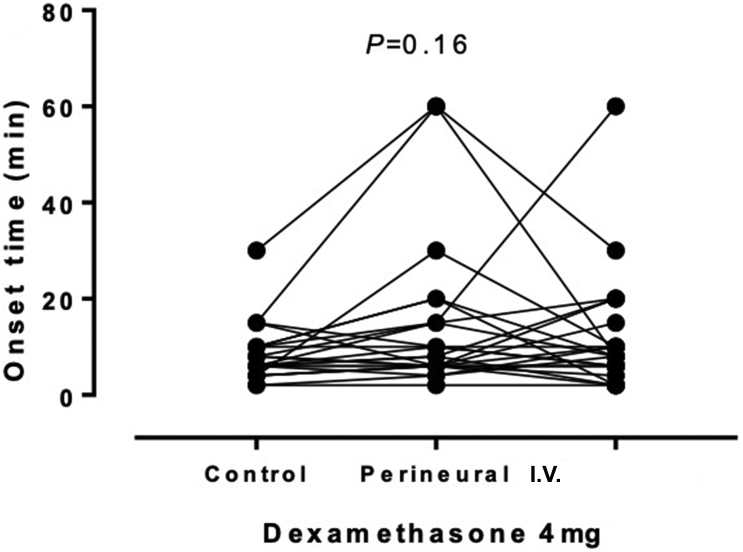

Twenty-four volunteers were enrolled and 72 blocks were performed: the blocks were performed on the left arm in 19 volunteers and the right arm in five volunteers. The volunteers had a median (range) age of 30 (22–55) yr and mean (sd) BMI of 23.7 (2.6) kg m−2. The duration of sensory block, as the primary outcome, was similar for the three interventions with no significant effect (P=0.61) of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone 4 mg, as shown in Figure 3 and summarised in Table 1. Likewise, for the secondary outcome, time to onset of sensory block, there was no significant effect (P=0.16) of dexamethasone 4 mg (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Fig 3.

Sensory block durations for each volunteer showing the effects of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone. Although the repeated measures are linked for the purposes of presentation, the order was randomised.

Table 1.

Effects of dexamethasone 4 mg on sensory block duration and onset time. Times are presented as median (inter-quartile range) with P-values from mixed models analysis

| Variable (N=24) | Control | Perineural | i.v. | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration (h) | 6.87 (5.85–7.62) | 7.37 (5.78–7.93) | 7.37 (6.10–7.97) | 0.61 |

| Onset time (min) | 6.0 (4.5–10.0) | 8.0 (6.0–15.0) | 8.0 (6.0–13.8) | 0.16 |

Fig 4.

Sensory block onset times for each volunteer showing the effects of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone. Although the repeated measures are linked for the purposes of presentation, the order was randomised.

Formal simultaneous crossover analyses for sequence (P≥0.90), period (P≥0.29), and period by treatment interactions (P≥0.27) using mixed models were not significant, suggesting no evidence of carry-over effects in the study.

At follow-up, all subjects had full recovery of sensation in the ulnar nerve distribution. There were no other sequelae of the study.

Discussion

This randomised crossover study in male volunteers found no clinically important or statistically significant effects of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone on sensory block with ropivacaine using a standardised peripheral nerve block model.

The pharmacodynamic effects of drugs co-administered with local anaesthetics are of particular interest. There have been no new local anaesthetic drugs introduced into clinical practice since ropivacaine and levobupivacaine more than 30 and 20 yr ago, respectively. The recent re-launch of chloroprocaine, an aminoester local anaesthetic, which was developed 70 yr ago, emphasises the lack of improved new agents for regional anaesthesia. Thus, adjuvants offer the only available possibility to improve the pharmacodynamic profile of nerve blocks. Alpha-2-receptor agonists,11, 17, 18, 19 opioids,20 N-methyl-d-aspartate-receptor antagonists,21 vasoconstrictors,22 or corticosteroids1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 have all been investigated for their potential to increase the duration of sensory blockade with local anaesthetics.

Dexamethasone has been extensively investigated as an additive drug to local anaesthetics for peripheral nerve blockade.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Table 2 summarises the main findings of seven meta-analyses of the use of dexamethasone in this context, and all authors highlight the low-quality evidence provided by the source data. Heterogeneous study designs using different types and concentrations of local anaesthetics with or without vasoconstrictors and a large variety of regional anaesthetic techniques and block sites are the main reasons for problems when interpreting previous trials.

Table 2.

Summary of meta-analyses investigating the effects of dexamethasone as an additive for peripheral nerve blockade on sensory block duration

| Included trials (no. of subjects) | Dexamethasone dose (mg) | Local anaesthetics | Mean difference (95% confidence interval) in sensory block duration (min) | Final conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi and colleagues3 (2014) | 9 (801) | 4–10 | Long-acting | +576 (522–631) | Dexamethasone prolongs sensory blockade duration; effect of systemic administration must be evaluated |

| Albrecht and colleagues1 (2015) | 29 (1695) | 4–10 | Short-, medium-, and long-acting | +233 (172–295) with short- and medium-acting LA + 488 (419–557) with long-acting LA | Interpret results with caution because of extreme heterogeneity of studies |

| Huynh and colleagues5 (2015) | 12 (1054) | 4–10 | Medium- and long-acting | +351 (288–413) | Significant prolongation of duration of peripheral nerve blockade |

| Zhao and colleagues7 (2017) | 10 (749) | 4–10 | With or without epinephrine | +2 (−4 to 14) without epinephrine +238 (160–316) with epinephrine |

Increases duration of sensory blockade only when epinephrine is also added |

| Baeriswyl and colleagues2 (2017) | 11 (914) | 4–10 | Short- and long-acting | +180 (84–270) | Sensory blockade increased by 21% with bupivacaine and 12% with ropivacaine, moderate quality of evidence |

| Pehora and colleagues6 (2017) | 35 (2702) | No information | Short-, medium-, and long-acting | +402 (332–471) | Low to moderate quality of evidence, i.v. dexamethasone increases block duration vs placebo, onging trials may change these results |

| Heesen and colleagues4 (2018) | 10 (783) | 5–10 | Short- and long-acting | +241 (87–394) | Low quality evidence |

The disadvantage of most clinical studies in the field of regional anaesthesia, which are performed during the course of routine clinical practice, is the fundamental difficulty of accurately evaluating the pharmacodynamic characteristics of the block. First, there are logistical problems. Studies may rely on routine postoperative observations for the outcome data, but the timing of these may not be sufficiently reliable because of the nature of busy clinical environments. Even if there are dedicated study personnel, the crucial endpoints may occur outside their working hours or the patient may have been discharged from the hospital. For these reasons, patient reported outcomes are sometimes used, but these may be unreliable if, for example, sensation returns during the night, or the patient is otherwise distracted and is unable to record precise timings. The second cause of difficulty in evaluating the duration of blocks arises from the associated surgery: both sensory and motor function testing can be impeded by the surgical dressings, which very often prevent access to the most invariable area of sensory innervation of the nerve in question. A third problem is the use of the time of onset of pain as a measure of sensory block duration. The inter-patient variability in pain perception is well known,23, 24 but surgical pain can be an inappropriate outcome if the surgical site is not completely covered by the nerve block under investigation: this can be inconsistent between patients, even those having the same operation, because of variability of sensory innervation.25

In contrast, clinical studies in volunteers provide a highly standardised study environment with highly motivated study subjects, dedicated and trained study personnel, and reproducible regional nerve block techniques. In particular, the ulnar nerve serves as a well-established model for such studies and shows a constant sensory distribution pattern with the lowest intra- and inter-individual variability compared with other sensory and motor nerves supplying the hand.11, 18, 25 The other major advantage of our study was the opportunity to use a crossover design that eliminated inter-individual variability in response to pinprick testing.

We administered ropivacaine 0.56% wt/vol, 3 ml, a dose and concentration that is described as sufficient to provide a full sensory block at peripheral nerves.26 The effect on sensory block duration of perineural dexamethasone has been described as dose-independent between 4 and 10 mg,1 so we used dexamethasone 4 mg for both the perineural and i.v. groups. Dexamethasone 4 mg as additive to local anaesthetics is described as the lowest sufficient dose for peripheral nerve blockade in the literature (Table 2).

We were unable to make a skin incision in our volunteers, so we could not define the onset time of our blocks in relation to the time to achieve surgical anaesthesia. While complete loss of pinprick sensation is a better predictor of surgical anaesthesia,15, 16 we defined onset time as the time to achieve VAS<10 mm in response to pinprick because, in our experience, this is a more reproducible endpoint. Furthermore, we required this endpoint to be reached in only four out of five discrete sites of sensory innervation of the ulnar nerve because of inter-patient variability in the sensory innervation of the hand.25 We defined sensory block duration as the time until the VAS in any one of the previously blocked areas reached >20 mm on the VAS (and not back to 100 mm) firstly to avoid an extremely long study duration. However, this is perhaps more comparable with the clinically relevant post-surgical endpoint of the onset of postoperative pain.

This study had >99% power to find a difference of 4 h in duration of sensory block that we decided to be the minimum important clinical difference when conducting our sample size calculations. The difference from the a priori power was because of the low root mean square error observed (1.4 h) compared with the conservative SD of 4 h that was used in the original sample size calculations. We based our power calculation on data from the study by Keplinger and colleagues,11 which used (the longer) duration until complete recovery from sensory block; it might be argued that a difference of <4 h using our endpoint might be clinically relevant. However, the present study still had 98% power to find a smaller difference of 2 h as significant.

Our study provides robust evidence that neither perineural nor i.v. dexamethasone prolongs sensory block duration of ropivacaine applied perineurally to the ulnar nerve. It is important to highlight that this study involved blockade of healthy nerves. It remains possible that dexamethasone as an additive to local anaesthetics may be useful in chronic pain therapy (e.g. neuropathic pain) through modulation of inflammatory changes or (similar to opioids) gene expression in affected nerves.27 Nevertheless, perineural administration of dexamethasone should be considered as a possible influence on neural blood flow.28 Further studies should investigate the use of dexamethasone as a perineural or additive drug in chronic pain therapy and the clinical impact on neural blood flow.

In conclusion, we found no evidence of a beneficial effect of perineural or i.v. dexamethasone 4 mg in prolonging sensory block with ropivacaine after ulnar nerve block in volunteers.

Authors' contributions

Contributed equally to analysing and interpreting the data, and to drafting the manuscript: PM, MC, PMH, MZ.

In charge of administrative aspects (ethics committee, communication with the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety, trial registration): DM.

Involved in study design and analysis: MC.

Contributed equally to the clinical management of the procedures for the volunteers: PM, DM, MG, MRLB, MZ.

Declarations of interest

PM and PMH are board members of the British Journal of Anaesthesia, MC is an editorial board member of the European Journal of Anaesthesiology and research methods and statistical editor at the British Journal of Anaesthesia. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

All financial support came from departmental sources.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Weber (study nurse at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna) and Valentin al Jalali (Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna) for their invaluable contributions throughout the study.

Handling editor: H.C. Hemmings Jr

Editorial decision: 02 January 2019

Footnotes

This article is accompanied by an editorial: Dexamethasone and peripheral nerve blocks: back to basic (science) by Hewson et al., Br J Anaesth 2019:122:411–412, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.02.004.

References

- 1.Albrecht E., Kern C., Kirkham K.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perineural dexamethasone for peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:71–83. doi: 10.1111/anae.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeriswyl M., Kirkham K.R., Jacot-Guillarmod A., Albrecht E. Efficacy of perineural vs systemic dexamethasone to prolong analgesia after peripheral nerve block: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:183–191. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S., Rodseth R., McCartney C.J. Effects of dexamethasone as a local anaesthetic adjuvant for brachial plexus block: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:427–439. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heesen M., Klimek M., Imberger G., Hoeks S.E., Rossaint R., Straube S. Co-administration of dexamethasone with peripheral nerve block: intravenous vs perineural application: systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-regression and trial-sequential analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:212–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huynh T.M., Marret E., Bonnet F. Combination of dexamethasone and local anaesthetic solution in peripheral nerve blocks: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:751–758. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pehora C., Pearson A.M., Kaushal A., Crawford M.W., Johnston B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011770.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao W.L., Ou X.F., Liu J., Zhang W.S. Perineural versus intravenous dexamethasone as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1529–1543. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S138212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marhofer P., Columb M., Hopkins P.M. Perineural dexamethasone: the dilemma of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichenberger U., Stöckli S., Marhofer P. Minimal local anesthetic volume for peripheral nerve block: a new ultrasound-guided, nerve dimension-based method. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:242–246. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819a7225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jæger P., Grevstad U., Koscielniak-Nielsen Z.J., Sauter A.R., Sørensen J.K., Dahl J.B. Does dexamethasone have a perineural mechanism of action? A paired, blinded, randomized, controlled study in healthy volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:635–641. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keplinger M., Marhofer P., Kettner S.C., Marhofer D., Kimberger O., Zeitlinger M. A pharmacodynamic evaluation of dexmedetomidine as an additive drug to ropivacaine for peripheral nerve blockade: a randomised, triple-blind, controlled study in volunteers. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:790–796. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madsen M.H., Christiansen C.B., Rothe C., Andreasen A.M., Lundstrøm L.H., Lange K.H.W. Local anesthetic injection speed and common peroneal nerve block duration: a randomized controlled trial in healthy volunteers. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:467–473. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marhofer D., Karmakar M.K., Marhofer P., Kettner S.C., Weber M., Zeitlinger M. Does circumferential spread of local anaesthetic improve the success of peripheral nerve block. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:177–185. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marhofer P., Eichenberger U., Stöckli S. Ultrasonographic guided axillary plexus blocks with low volumes of local anaesthetics: a crossover volunteer study. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:266–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marhofer D., Marhofer P., Kettner S.C. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of the spread of local anesthetic solution after ultrasound-guided lateral thoracic paravertebral blockade: a volunteer study. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1106–1112. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318289465f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curatolo M., Petersen-Felix S., Arendt-Nielsen L. Sensory assessment of regional analgesia in humans: a review of methods and applications. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1517–1530. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200012000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelika P., Arun J.M. Evaluation of clonidine as an adjuvant to brachial plexus block and its comparison with tramadol. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2017;33:197–202. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_58_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marhofer D., Kettner S.C., Marhofer P., Pils S., Weber M., Zeitlinger M. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine prolongs peripheral nerve block: a volunteer study. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:438–442. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patil K.N., Singh N.D. Clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine-induced supraclavicular brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2015;31:365–369. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.161674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heo B.H., Lee H.J., Lee H.G. Femoral nerve block for patient undergoing total knee arthroplasty: prospective, randomized, double-blinded study evaluating analgesic effect of perineural fentanyl additive to local anesthetics. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004771. e4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee I.O., Kim W.K., Kong M.H. No enhancement of sensory and motor blockade by ketamine added to ropivacaine interscalene brachial plexus blockade. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:821–826. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saied N.N., Gupta R.K., Saffour L., Helwani M.A. Dexamethasone and clonidine, but not epinephrine, prolong duration of ropivacaine brachial plexus blocks, cross-sectional analysis in outpatient surgery setting. Pain Med. 2017;18:2013–2026. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen C.S., Stubhaug A., Price D.D., Vassend O., Czajkowski N., Harris J.R. Individual differences in pain sensitivity: genetic and environmental contributions. Pain. 2008;136:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen C.S., Staud R., Price D.D. Individual differences in pain sensitivity: measurement, causation, and consequences. J Pain. 2009;10:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keplinger M., Marhofer P., Moriggl B., Zeitlinger M., Muehleder-Matterey S., Marhofer D. Cutaneous innervation of the hand: clinical testing in volunteers shows high intra- and inter-individual variability. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein S.M., Greengrass R.A., Steele S.M. A comparison of 0.5% bupivacaine, 0.5% ropivacaine, and 0.75% ropivacaine for interscalene brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1316–1319. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199812000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueda H. Molecular mechanisms of neuropathic pain-phenotypic switch and initiation mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:57–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shishido H., Kikuchi S., Heckman H., Myers R.R. Dexamethasone decreases blood flow in normal nerves and dorsal root ganglia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:581–586. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200203150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]