Abstract

Cupping Therapy (CT) is an ancient method and currently used in the treatment of a broad range of medical conditions. Nonetheless the mechanism of action of (CT) is not fully understood. This review aimed to identify possible mechanisms of action of (CT) from modern medicine perspective and offer possible explanations of its effects. English literature in PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar was searched using key words. Only 223 articles identified, 149 records screened, and 74 articles excluded for irrelevancy. Only 75 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, included studies in this review were 64. Six theories have been suggested to explain the effects produced by cupping therapy. Pain reduction and changes in biomechanical properties of the skin could be explained by “Pain-Gate Theory”, “Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls” and “Reflex zone theory”. Muscle relaxation, changes in local tissue structures and increase in blood circulation might be explained by “Nitric Oxide theory”. Immunological effects and hormonal adjustments might be attributed to “Activation of immune system theory”. Releasing of toxins and removal of wastes and heavy metals might be explained by “Blood Detoxification Theory”. These theories may overlap or work interchangeably to produce various therapeutic effects in specific ailments and diseases. Apparently, no single theory exists to explain the whole effects of cupping. Further researches are needed to support or refute the aforesaid theories, and also develop innovative conceptualizations of (CT) in future.

Keywords: Cupping, Hijama, Mechanisms of action, Effects

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cupping therapy is an ancient method of treatment that has been used in the treatment of a broad range of conditions.1 There are many types of cupping therapy; however, dry and wet cupping are the two main types.2 Dry cupping pulls the skin into the cup without scarifications, while in wet cupping the skin is lacerated so that blood is drawn into the cup.3 Although cupping has been a treatment for centuries, and had been used by various culture and societies, its mechanism of action is not well understood.4 Recently, interest in cupping has re-emerged and subsequently, several studies have begun to investigate the mechanisms underpinning cupping therapy.5 For the mainstream doctors trained in western medical sciences, the focus is largely on the biomedical causes of disease, while traditional medicine practitioners take a holistic approach.6 Notably, cupping therapy possibly produces numerous effects through a plethora of mechanisms.7 Research scientists tend to explain a particular phenomenon or effect of a drug or device or cupping therapy by describing its underlying mechanism (s). In practice, description of a mechanism is never complete because details of related processes are not fully identified.8 Hypothesis-focused research, however, allows investigators to identify cause-effect relationships, and is a powerful method for modifying theories about intervention-outcome paradigm.9 Fønnebø et al. (2007) stated that a common strategy in traditional medicine is to use a reverse research strategy, because traditional therapies -including cupping therapy-have been in clinical use for thousands of years. Accordingly, researchers need to understand what the treatment procedure is, how many variations it has, and what theoretical foundations underline it, the ideas about health and disease, its contextual framework and key treatment components.10 One of the controversial views concerning cupping therapy is that it has only a placebo effect.11 This placebo theory about cupping therapy will remain alive until a reliable and valid mechanism is found out.12 The controversial arguments related to cupping therapy motivated the authors of this present study to participate in resolving this scientific dilemma through reviewing available relevant literature. Detailed studies regarding its mechanisms, supported by well-designed scientific researches, would help in the safe and effective application of the cupping therapies.13 This research endeavor will establish scientific explanations along with evidence-based mechanisms underpinning cupping therapy.

The aim of this review was to identify and discuss the possible cupping therapy mechanisms of action from a modern medicine perspective and provide the possible explanations of the multiple effects of cupping therapy.

1.1. A brief description of cupping therapy technique

Cupping is a simple application of quick, vigorous, rhythmical strokes to stimulate muscles and is particularly helpful in the treatment of aches and pains associated with various diseases. Thus, cupping carries the potential to enhance the quality of life.14 Each cupping session takes about 20 min and could be conducted in five steps. The first step includes primary suction. In this phase, the therapist allocates specific points or areas for cupping and disinfects the area. A cup with a suitable size is placed on the selected site and the therapist suck the air inside the cup by flame, electrical or manual suction. Then the cup is applied to the skin and left for a period of three to 5 min. The second step is about scarification or puncturing. Superficial incisions are made on the skin using Surgical Scalpel Blade No. 15 to 21, or puncturing with a needle, auto-lancing device or a plum-blossom needle.15 The third step is about suction and bloodletting. The cup is placed back on the skin using the similar procedure described above for three to 5 min. The fourth step includes the removal of the cup, followed by the fifth step which includes dressing the area after cleaning and disinfecting with FDA approved skin disinfectant. Furthermore, suitable sizes of adhesive strips are then applied to the scarified area, which remain there for 48 h.16 It is wise to know that the suction and scarification are the two main techniques of wet cupping therapy. Each technique of cupping might be responsible for certain changes at the level of body cells, tissues or organs. Specific interventions could enhance or suppress body hormones, or it might stimulate or modulate immunity, or it may get rid of harmful substances from the body, and eventually it might ease the pain.

2. Materials & methods

This review focused on theories and hypotheses that explain mechanisms of cupping therapy from a modern medicine perspective. Theories related to traditional systems of medicine such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, Unani Medicine or other traditional healing practices were excluded from this review.

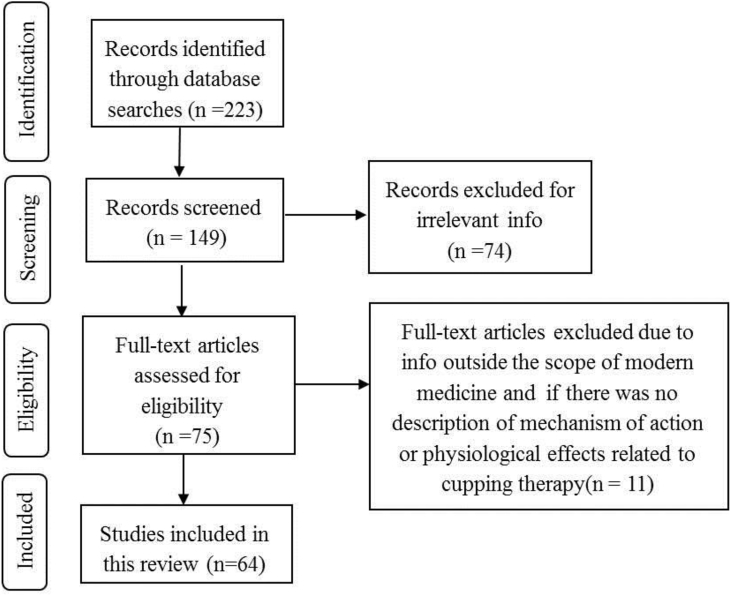

The relevant literature published in English was searched in PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar databases. The Boolean operators and keywords used in multiple electronic searches were cupping [All Fields] AND [mechanism of action] [All Fields] OR effect [All Fields]. The search strategy and the keywords were modified as appropriate according to the database search. In addition, the studies' listed references in included articles were hand searched. Articles retrieved were 223 which were reviewed by two independent assessors and finally both agreed to include 64 studies in this narrative review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

3. Results

Two hundred twenty three articles were identified and finally 64 studies included in this review. The revealed results signified that certain effects and outcomes related to cupping therapy might be linked to its possible theoretical and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Neural, hematological, and immunological effects may be considered as mechanism of action of cupping.17

Metabolic hypothesis assume that cupping decreases increased muscle activity which results in pain reduction.18 Redness, bullae formation and histological changes in the skin are possibly due to vasodilatation and edema without actual cellular infiltrate,19 and these effects do not fit into immune system paradigm. Elimination of toxins trapped in the tissues by cupping also makes the person feels better.20 Many studies provided some evidence about the effectiveness of cupping in certain medical and health conditions.12

3.1. Cupping therapy effects

There is converging evidence that cupping can induce comfort and relaxation on a systemic level and the resulting increase in endogenous opioid production in the brain leads to improved pain control.5 Other researchers proposed that the main action of cupping therapy is to enhance the circulation of blood and to remove toxins and waste from the body.21 That could be achieved through improving microcirculation, promoting capillary endothelial cell repair, accelerating granulation and angiogenesis in the regional tissues, thus helping normalize the patient's functional state and progressive muscle relaxation.22,23 Cupping also removes noxious materials from skin microcirculation and interstitial compartment24 which benefit the patient. Cupping may be an effective method of reducing low density lipoprotein (LDL) in men and consequently may have a preventive effect against atherosclerosis25 and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Cupping is known to significantly decrease in total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein LDL/high density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio.26 Cupping therapy can significantly lower the number of lymphocytes in the local blood related to the affected area with an increase in the number of neutrophils, which is one of the antiviral mechanisms that reduces the pain scores.27 Loss of blood along with vasodilation tends to increase the parasympathetic activity and relaxes the body muscles which benefit the patient and could also be associated with the after effects of cupping. Furthermore, the loss of blood is thought to increase the quality of the remaining blood that improves pain symptoms.28 It has also been found that cupping increases red blood cells RBCs.29 It has been claimed that cupping therapy tends to drain excess fluids and toxins, loosen adhesions and revitalize connective tissue, increase blood flow to skin and muscles, stimulate the peripheral nervous system, reduce pain, controls high blood pressure and modulates the immune system.21,30 Some researchers believe that the build-up of toxins is the main reason for illness development. In the cupped region, blood vessels are dilated by the action of certain vasodilators such as adenosine, noradrenaline and histamine. Consequently, there is an increase in the circulation of blood to the ill area. This allows the immediate elimination of trapped toxins in the tissues, and, hence, the patient feels better.20 Cupping has been found to improve subcutaneous blood flow and to stimulate the autonomic nervous system.21,31 Like injuries to the skin due to the incisions, stimulation of the skin causes several autonomic, hormonal, and immune reactions attributed to the sympathetic and parasympathetic efferent nerves to the somato-visceral reflexes related to the organs.32 Cupping is reported to restore sympathovagal balance and might be cardio-protective by stimulating the peripheral sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.33 Cupping seems to play a role in the activation of complement system as well as modulation of cellular part of immune system.34 There is also a significant reduction in blood sugar in diabetic patients after cupping.35 Chen and colleagues concluded that there are some improvements in the research concerning the mechanisms of cupping therapy.36 Overall, cupping is reported to effect changes in the biomechanical properties of the skin,37 increase immediate pain thresholds in patients with neck pain and in a healthy subject as well,38 reduce significantly peripheral and local P substance39 and reduce the inflammation.40

3.2. Cupping therapy outcomes in certain medical conditions

Cupping therapy is reported to treat a variety of diseases due to the effects of multiple types of stimulation.38 Cao and associates (2010) suggested that cupping therapy appears to be effective for various medical conditions, in particular herpes zoster and associated pain and acne, facial paralysis, and cervical spondylosis.41 Cupping therapy is often used for lowering blood pressure and prevents the development of cardio vascular diseases CVDs in healthy people.42 Wet cupping in conjunction with conventional treatment is reported to effectively treat oral and genital ulceration in patient with Behçet's disease.43 There is growing evidence that wet cupping is effective in musculoskeletal pain,44 nonspecific low back pain,45 neck pain,46 fibromyalgia47,48 and other painful conditions.14 Michalsen et al. (2009) concluded that cupping therapy may be effective in alleviating the pain and other symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.49 Cupping therapy is also found to be effective in headache and migraine.11 Cupping therapy is effective for reducing systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients for up to 4 weeks without any serious side effects.50 Evidently, cupping therapy is effective in the treatment of cellulitis.51 Cupping therapy has been used with various level of evidence (I to V) in many conditions such as cough, asthma, acne, common cold, urticaria, facial paralysis, cervical spondylosis, soft tissue injury, arthritis and neuro-dermatitis.41,52

3.3. The most likely mechanisms of cupping and effects: bridging the gap

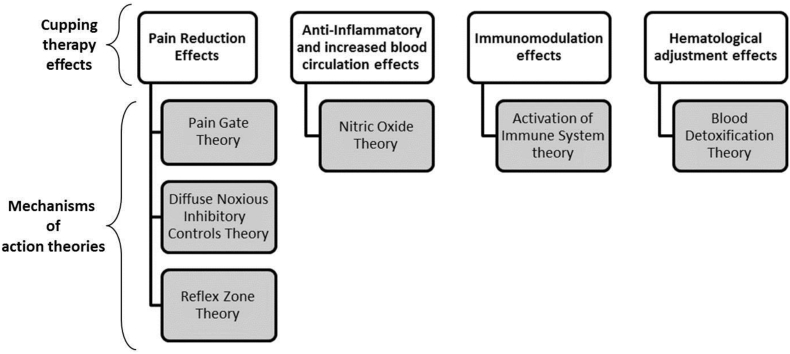

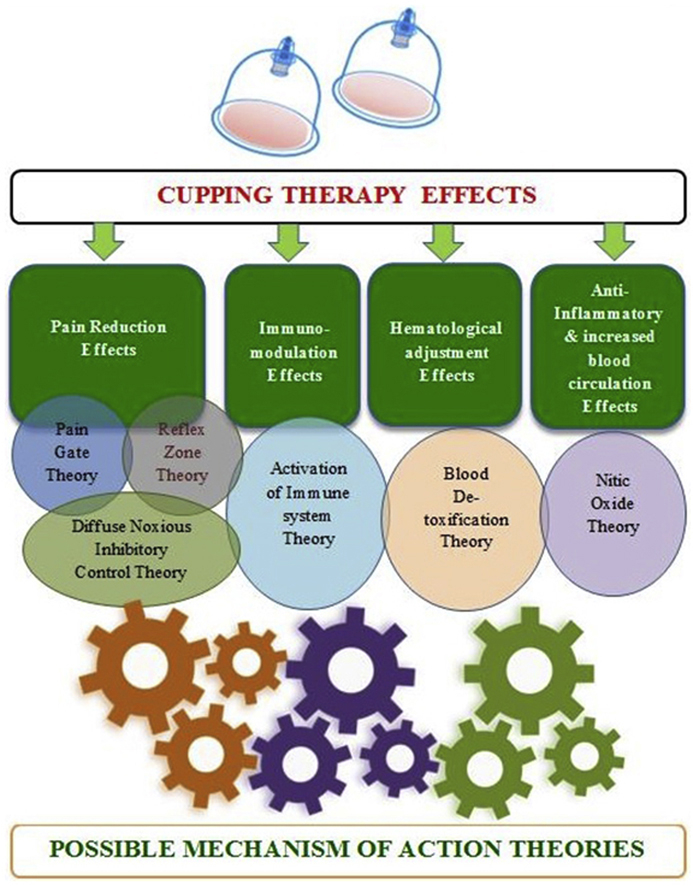

Many theories have been suggested to explain numerous effects of cupping therapy and its mechanisms of action.53 Several researchers proposed biological and mechanical processes associated with the cupping session. For instance, reduction of pain may result from changes in biomechanical properties of the skin as explained by the “Pain-Gate Theory” (PGT),54 “Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls” (DNICs),55 and “Reflex Zone Theory” (ZRT).56 Muscle relaxation, specific changes in local tissue structures and increase in blood circulation could be explained by the “Nitric Oxide Theory”.57 The immunomodulatory effects of cupping therapy could be attributed to the “Activation of Immune System Theory” (AIST).34 Releasing of toxins and removal of wastes and heavy metals might be attributed to the “Blood Detoxification Theory” (BDT).58,59

These theories may have been interacting harmoniously to produce the beneficial effects of cupping in treating patients with various diseases and promoting wellbeing in healthy people.

3.4. Linking cupping therapy effects with mechanism of action

Reviewing the literature on cupping and its mechanism of action has revealed insufficient information about the physiological, biological and mechanical changes of the body during cupping therapy. A better understanding of the whole cupping procedure could be achieved by linking cupping therapy effects with its mechanisms based on aforesaid theories (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Links between cupping therapy effects and mechanisms of action theories.

3.5. Effects and four main mechanisms of action

Although the exact mode of action of cupping to reduce pain is not well understood,42 three main possible hypotheses and theories might explain mechanisms of pain reduction. These include “Pain-Gate Theory” (PGT), “Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls (DNICs)”and “Reflex Zone Theory” (RZT).60 A brief description of each theory will follow in the subsequent subsections.

3.5.1. Pain-Gate Theory (PGT)

This theory comprehensively explains how the pain is transmitted from the point of its inception to the brain, and how it is processed in the brain which sends back the efferent, protective signal to the stimulated or injured area. It is reported that local damage of the skin and capillary vessels acts as a nociceptive stimulus.21 This is explanation based on a neuronal hypothesis whereby cupping influences chronic pain by altering the signal processing at the level of the nociceptors both of the spinal cord and brain.61 In support of this clinical effect of cupping, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported that cupping could be a promising therapy for pain treatment.62 The “Pain Gate Theory” is one of the most influential theories of pain reduction.63 Melzack and Wall (1965)proposed that both thin and large (touch, pressure, vibration) nerve fibers carry the pain signal from the site of injury to two destinations in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord however, transmission cells carry the pain signal to the brain while the inhibitory interneurons impede transmission cell activity. The activity in both thin and large diameter fibers excites transmission cells. Thin fiber activity impedes the inhibitory cells (tending to allow the transmission cell) and large diameter fiber activity excites the inhibitory cells (tending to inhibit transmission cell activity). So, the more large fiber (touch, pressure, vibration) activity, the less pain is felt.64 It is expected that the activation of nociceptors by cupping and other reflex therapies can stimulate “A” and “C” fibers with involvement of the spino-thalamo-cortical pain pathway. It is noted that the peripheral nociceptor is sensitized by metabolic factors like lactate, adenosine triphosphate, and cytokines.65 When a stimulus is applied to the skin, it produces an increase in the number of active receptor-fiber units as information about the stimulus is transmitted to the brain. Since many larger fibers are inactive in the absence of stimulus change, stimulation tends to produce a disproportionate relative increase in large fiber over small fiber activity. Thus, if a gentle pressure stimulus is applied suddenly to the skin, the afferent volley contains large-fiber impulses which not only fire the “T” cells but also partially close the presynaptic gate. And if the stimulus intensity is increased, more receptor-fiber units are recruited and the firing frequency of active units is increased.66,67 The resultant positive and negative effects of the large fiber and small-fiber inputs tend to counteract each other, and therefore the output of the “T” cells rises slowly. If stimulation is prolonged, the large fibers begin to adapt, producing a relative increase in small-fiber activity. As a result, the gate is opened further, and the output of the “T” cells rises more steeply. If the large-fiber steady background activity is artificially raised at this time by vibration or scratching (a maneuver that overcomes the tendency of the large fibers to adapt), the output of the cells decreases.68 Cupping therapy may alleviate pain by means of anti-nociceptive effects and by counter irritation. However, at present, it is unclear to what extent cupping induces such mechanisms.69 But it is believed that cupping stimulate pain receptors which lead to increase the frequency of impulses, therefore ultimately leading to closure of the pain gates and hence pain reduction.11 So, validation of such theory by a scientific clinical studies is highly needed

3.5.2. Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls (DNICs)

Another theory related to pain reduction as a mechanism of action of cupping therapy is Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls. DNIC signifies inhibition of activity in convergent or wide dynamic range-type nociceptive spinal neurons triggered by a second, spatially remote, noxious stimulus. This phenomenon is thought to underlie the principle of counter-irritation to reduce pain. Herein “one pain masks another”, or pain inhibits pain. This pain-inhibitory system can be easily triggered in an experimental setting.70 Notably the term conditioned pain modulation (CPM) replaced the “noxious inhibitory controls” or 'DNIC-like' effects. However, experts recommended using ‘diffuse noxious inhibitory controls’ to describe the lower brainstem-mediated inhibitory mechanism directly observed in animal studies, and ‘CPM’ to portray the human behavioral correlate. Most of the work concerning this theory was done on the idiopathic pain syndromes such as irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorders, fibromyalgia, and tension type headache, which have shown good response to cupping therapy.71 Local damage of the skin and capillary vessels induced by cupping may cause a nociceptive stimulus that activates DNICs.66 This mechanism requires a strong conditioning stimulus for pain attenuation, which may be at least partly dependent on a distraction effect,72 and may possibly act by triggering a DNIC60 or by removing oxidants and decreasing oxidative stress.7 Cupping therapy may produce an analgesic effect via nerves that are sensitive to mechanical stimulation. This mechanism is similar to acupuncture in that it activates A∂ and C nerve fibers which are linked to the DNICs system, a pain modulation pathway which has been described as ‘pain inhibits pain’ phenomenon.73,74

3.5.3. Reflex Zone Theory

Cupping therapy of defined zones or areas of the shoulder triangle segmentally related to the median nerve to treat carpal tunnel syndrome has been practiced in European folk medicine and is supported by various studies.49 Only a suction stimulation is done on the disturbed point and thereafter the red blood cells from the vascular system are brought out to the surrounding tissue areas without injuring capillary vessels. This is known as dry diapedesis. These extravasations are digested or removed by the connective tissue. This happens when the disturbed area is better supplied with blood causing an activation of biological processes on the treated area, i.e., disturbed reflex zone.18 In conventional medicine, external manifestations of an internal disease process can often be detected at a site distal to the affected organ. It is suggested that the principle of a link between one part of the body and another can be understood in terms of interactions of nerve, muscle and chemical pathways.74 RZT depends on the premise that signs and symptoms of illness related to one dermatome may be reflected in changes in neighboring dermatomes.75 The reflex signs of disease can be recognized in the skin, which becomes pale, cold and clammy due to vasoconstriction and flushing due to vasodilatation. The subcutaneous tissue becomes shiny, edematous and dense. The muscles become less contractile. The joints show degenerative changes appearing in ligaments, capsule and cartilage, and reduction of synovial fluid leading to painful and restricted movement. The functioning of organs becomes impaired as a result of reduced circulating blood and tissue fluids. Such changes in the color and texture of the skin or sweating are present from the earliest stages of disease.56 Sato and associates (1997) described the response of visceral organs to somatic stimulation and showed robust evidence that the stimulation of somatic structures including the skin and peripheral joints can have substantial effects on cardiovascular, bladder, and gastrointestinal function in experimental animals. These reflexes are more complex and can be excitatory and inhibitory of visceral function acting through spinal pathways and supra-spinal and cortical centers.76 In cupping therapy, when the diseased organ sends a signal to the skin through the autonomic nerves, the skin responds by becoming tender and painful with swelling. Skin receptors are activated when cups are applied to the skin. The entire process will result in the increment of the blood circulation and blood supply to the skin and the internal organs through the neural connections.77 It worth mentioning that, further clarification of the mechanisms of action of reflex therapies will support their clinical evidence and add to our understanding of the neurobiology of complementary medicine including cupping therapy as a model.61

3.5.4. Release of Nitric Oxide theory

Nitric Oxide (NO) is a signaling gas molecule that mediates vasodilatation and regulates blood flow and volume.78 NO regulates blood pressure, contributes to the immune responses, controls neurotransmission and participates in cell differentiation and in many more physiological functions.79 Cupping therapy could cause release of NO from endothelial cells and, hence, induce certain beneficial biological changes. This mechanism is explained by “Release of Nitric Oxide and increased blood circulation theory”. An experimental trial reported increased expression of NO synthase (s), enzymes producing NO from l-arginine was higher around skin acupuncture points of rats.80 Notably, the active substance Endothelium-Derived Relaxing Factor (EDRF) recovered from perfusates during application of the stimulus has been identified pharmacologically and chemically as NO. EDRF is an unstable humoral substance released from artery and vein that mediates the action of endothelium-dependent vasodilators. Furthermore the actions of NO on vascular smooth muscle closely resemble those of EDRF.81 Studies suggested that nitric synthesis is critical to wound collagen accumulation and acquisition of mechanical strength.82 Cupping dilates topical capillaries and increases dermal blood flow, which has been proved by numerous studies.83,84 Blood vessels in the treated areas by cupping are dilated by release of vasodilators such as adenosine, noradrenaline, and histamine, which lead to increased blood circulation.85 Tagil et al. (2014) found higher activity of myeloperoxidase, lower activity of superoxide dismutase, higher levels of malondialdehyde and nitric oxide in cupping blood compared to the venous blood.7 It seems that nitric oxide derived from endothelial cells due to cupping therapy causes vasodilatation, a decrease in vascular resistance, lower blood pressure, inhibition of platelet aggregation and adhesion, inhibition of leukocyte adhesion and migration, and reduction of smooth muscle proliferation, and all these effects prevent development of atherosclerosis.57

3.5.5. Activation of Immune System Theory

From the perspective of body immunity and defense, practitioners begin to understand the action of cupping therapy through regulating immunoglobulins and hemoglobin,86 and its various immunological effects. Cupping decreases serum IgE and IL-2 levels and increases serum C3 levels which are found to be abnormal in the immune system.87 Cupping is likely to affect the immune system via three pathways. First, cupping irritates the immune system by making an artificial local inflammation. Second, cupping activates the complementary system. Third, cupping increases the level of immune products such as interferon and tumor necrotizing factor. Cupping effect on the thymus increases the flow of lymph in the lymphatic system.16 Overall, activation of immune system by cupping might explain its various effects including therapeutic outcomes in patients with autoimmune diseases. This theory explains the effect of cupping for strengthening immunity which has been the subject of recent research around the world. For instance, Khalil and colleagues (2013) claimed that cupping seems to play a role in the activation of complement system as well as modulation of cellular part of immune system and it may have a protective role by increasing immunity, and thereby, protect the body from diseases.34 A clinical study by XIAO Wei et al. (2010) concluded that cupping significantly improves immunologic functions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during stable stage.88 Sahbaa et al. (2005) claimed that cupping therapy significantly reduces the laboratory markers of rheumatoid arthritis activity and modulates the immune cellular conditions particularly of innate immune response Natural killer cells and adaptive cellular immune response the Soluble Interleukin 2 Receptor SIL-2R.89 Mohammad Reza et al. (2012) evaluated Interferon Gamma (IFNγ) and Interleukin 4 (IL-4) concentrations in supernatant of vein and cupping blood cultures with or without the presence of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) mitogen. The results showed IFN-γ and IL-4 concentrations in cupping blood samples were higher compared to venous blood samples without presentation of any mitogen. He concluded that the high level of lymphocytes in cupping blood samples plays an important role in discharge of IFN-γ and IL-4. Furthermore, in the presence of PHA mitogen the levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in cupping blood samples were equally low as in venous blood samples. The study claimed that lymphocytes in cupping blood samples may not have their natural function, so they cannot properly respond to stimulation of mitogen. Moreover, two weeks after cupping the researcher did not see any difference in IFN-γ and IL-4 concentrations in venous blood. It seems that the reduplication of cupping immune response will be affected and IFN-γ and IL-4 concentrations will increase.90 A study by Ye LH, (1998) revealed that cupping produces a bidirectional effects on human immunoglobulins, corrects the irregular immunoglobulin level, yields insignificant effect on normal immunoglobulin, and the regulation result is related to the original function state.91 Zhang et al. (2001) reported that cupping can upregulate the oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin. As the carrier of hemoglobin, the red blood cell is an important defensive system, working to recognize antigens, and eliminate immune complex, tumor cells, and effector cells, as well as bind germs and viruses, and regulate immune function.92 Moreover, Zhong, et al. (1999) discovered the absolute value of C3b receptor rosette and immune complex of red blood cell significantly increased after moving cupping, which indicated that moving cupping can improve the immune function of red blood cell.93 Chen and Li (2004) claimed that cupping suggillation is the manifestation of auto-hemolysis, which can produce histamine-like substances, and consequently strengthen the activity of tissues and organs as well as the immunity.94 The recent study by Yang Guo et al. (2017) proposed that the microenvironment is changed when stimulating the surface of the skin, and physical signals transform into biological signals, which also interact with each other in the body. These signaling cascades activate the neuroendocrine-immune system, which produces the therapeutic effect.95 More immunological studies are needed to measure and validate the early assumption.

3.5.6. Blood detoxification theory

This theory addresses the removal of toxic substances from the affected area where the cups are applied. According to the blood detoxification theory, there is a decrease in the level of uric acid, HDL, LDL and the molecular structure and function of hemoglobin (Hb) and other hematological adjustments. This theory explains how the body is relieved of toxins and harmful materials through the underlying mechanism of cupping therapy. From the view of physics, for clearing the toxins, the negative pressure suction produced by cupping benefits the extraction of the toxins generated by the purulent fluid, exudation, and germs, as well as the histolytic enzyme. Cupping also promotes the growth of granulation and the recovery of wounds.34 Several studies reported significant differences in many of the biochemical, hematological and immunological parameters between the venous blood and the cupping blood.96 In cupping, the flow of blood tends to breakup obstructions and creates an avenue for toxins to be drawn out of the body. Several cups may be placed on a patient's body at the same time.97 Cupping may play a role in excretion of old red blood cells.98 The levels of uric acid, urea, triglycerides and cholesterol were significantly high in the wet cupping blood.99 In cases of acute gouty arthritis, cupping on the affected area is reported to stop pain, dissolves the toxic damp and removes blood stasis and promote the blood circulation.100 Daniali et al. (2008) reported that the concentrations of uric acid, HDL, LDL, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and iron were high in the wet cupping blood. Furthermore, the levels of red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, viscosity, mean corpuscular hemoglobin in the wet cupping blood were significantly higher compared to venous blood.58 Moreover, cupping can affect molecular structure and function of human hemoglobin and reduces the side effects of diabetes on Hb molecule.101 A study by Mahdavi et al. (2012) revealed highly significant increase in serum uric acid level as compared to venous blood sample.90 The increase of blood flow may promote the release of toxins and wastes, improves the local nutrition state, and finally boosts the metabolism and supporting the healthy aspect and eliminating the pathogenic factors.34 According to SumeyyeGok et al. (2016) removing heavy metals such as aluminum, mercury, silver and lead which were significantly higher in cupping blood compared to venous blood of the same patients would support the detoxification mechanisms of action59 and therefor, cupping may treat diseases associated with heavy metal deposition in different parts of the body.

4. Discussion

This review intensively explored the theories concerning the mechanisms underlying cupping therapy. No single theory could explain the mechanisms of action underpinning cupping therapy along with its multiple effects. Cupping is performed by several individual techniques according to cupping type.7 Each technique might be responsible for certain changes in the cells, tissues and organs30 One or more of the therapeutic effects of cupping may be partially explained by a single theory or more paradigms. Pain reduction, changes in biomechanical properties of the skin and precipitate blood circulation could be explained by Pain-Gate Theory, Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls (DNICs) and Reflex Zone Theory. Muscle relaxation, specific changes in local tissue structures and increase blood circulation could be explained by a release of Nitric Oxide Theory. In addition, immunological modulation and hormonal adjustment related more to anti-inflammatory action of cupping therapy could be explained by Activation of Immune System Theory. Removal of toxins, uric acid, lipoprotein, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, iron and heavy metals could be explained by Blood Detoxification Theory.

Some limitations are noted to this study. Measuring diverse and multiple effects with single procedure are to be considered a limitation to this study. Moreover, it is difficult to determine whether the outcome of cupping therapy is due to any specific type or step in cupping procedure. The details of every part and process of a mechanism are not fully understood, making it difficult to having a complete scientific description on how that mechanism works in cupping. This review has a couple of strengths. We use descriptive analyses for generating hypotheses and theories that explained how cupping therapy works in producing a plethora of effects including therapeutic benefits. However, these paradigms need to be verified by advanced scientific basic research. Documented data on cupping effectiveness and multiple outcomes found in various diseases based on the reversed research strategy could be a reasonable approach to link its certain mechanisms of action with the reported effects. Overall, it appears that aforesaid mechanisms of cupping therapy could not explain all its effects and further research is warranted to develop more theories concerning this traditional treatment technique.

5. Conclusion

This review identified some possible mechanisms of cupping therapy based on certain theories that explain its diverse effects. No single theory could explain its full spectrum of effects. The beneficial effects of cupping therapy need to be substantiated by large randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses in future. Basic scientific innovative research is also needed to verify the discussed theories about cupping along with inventing new theories. Prevailing theories on cupping therapy mechanism of action that are related to Traditional Chinese Medicine, Unani Medicine or other traditional healing practices need to be addressed in a new innovative study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in this work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

Contributor Information

Abdullah M.N. Al-Bedah, Email: a.albedah@nccam.gov.sa.

Ibrahim S. Elsubai, Email: i.elsubai@nccam.gov.sa.

Naseem Akhtar Qureshi, Email: n.qureshi@nccam.gov.sa.

Tamer Shaban Aboushanab, Email: t.shaban@nccam.gov.sa.

Gazzaffi I.M. Ali, Email: g.mahjoub@nccam.gov.sa.

Ahmed Tawfik El-Olemy, Email: a.alolemy@nccam.gov.sa.

Asim A.H. Khalil, Email: a.abdulmoneim@nccam.gov.sa.

Mohamed K.M. Khalil, Email: m.khalil@nccam.gov.sa.

Meshari Saleh Alqaed, Email: m.alqaed@nccam.gov.sa.

References

- 1.Ullah K., Younis A., Wali M. An investigation into the effect of cupping therapy as a treatment for anterior knee pain and its potential role in health promotion. Internet J Alternative Med. 2006;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Bedah A.M., Aboushanab T.S., Alqaed M.S. Classification of Cupping Therapy: a tool for modernization and standardization. J. Compl. Alternative Med. Res. 2016;1 1:1-0. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Jong-In, Lee Myeong Soo, Lee Dong-Hyo, Boddy Kate, Ernst Edzard. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011. Cupping for treating pain: a systematic review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghods R., Sayfouri N., Ayati M.H. Anatomical features of the interscapular area where wet cupping therapy is done and its possible relation to acupuncture meridians. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2016;9:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2016.06.004. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozenfeld Evgeni, Kalichman Leonid. New is the well-forgotten old: the use of dry cupping in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20(1):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madamombe Itai. Traditional healers boost primary health care Reaching patients missed by modern medicine. Afr. Renew. 2006;19 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tagil S.M., Celik Huseyin Tugrul, Ciftci Sefa. Wet-cupping removes oxidants and decreases oxidative stress. Com-plement Ther Med. 2014;22:1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanism_(biology) accesses on 27 Feb, 2017.

- 9.Lewith George T., Jonas Wayne B., Walach Harald. Clinical Research in Complementary Therapies: Principles, Problems and Solutions. second ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fønnebø Researching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Med Res Meth. 2007;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadi A., Schwebel D.C., Rezaei M. The Efficacy of wet-cupping in the treatment of tension and migraine headache. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36:37–44. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X08005564. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmedi M., Siddiqui M.R. The value of wet cupping as a therapy in modern medicine – an Islamic Perspective. Webmed Cent. Alternative Med. 2014;5:12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta Piyush, Dhapte Vividha. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Compl. Med. 2015 Jul;5(3):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.11.036. Published online 2015 Feb 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AlBedah A., Klahlil M., Elolemy A., Elsubai I., Khalil A. Hijama (cupping): a review of the evidence. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2011;16:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Rubaye K.Q.A. The clinical and Histological skin changes after the cupping therapy (Al-Hujamah)’. J. Turkish Acad. Dermatol. 2012;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaban T. Professional Guide to Cupping Therapy. first ed. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farhadi K., Schwebel D.C., Saeb M., Choubsaz M., Mohammadi R., Ahmadi A. The effectiveness of wet cupping for nonspecific low back pain in Iran: a randomized controlled trial. Compl Ther Med. 2009;17:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.05.003. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abele J. Definition of the Cupping Process. München: Urban & Fischer; 2003. Das Schroepfen: einebewaehrte alternative Methode, CUPPING A reliable alternative healing method; pp. 48–53. Translation of the German book by by Um Yasin Ahmad Hefny. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Rubaye Kadhim Qasim Ali. The clinical and Histological skin changes after the cupping therapy (Al-Hujamah) J. Turkish Acad. Dermatol. 2012;6:1. 1261a1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauche Romy. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012. The effect of traditional cupping on pain and mechanical thresholds in patients with chronic Nonspecific neck pain: a randomised controlled pilot study’. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo Simon S., Tausk Francisco. Cupping: east meets west. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:664–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02224.x. 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauche R., Materdey S., Cramer H., Haller H., Stange R. vol.8. 2013. Effectiveness of Home-Based Cupping Massage Compared to Progressive Muscle Relaxation in Patients with Chronic Neck Pain—a Randomized Controlled Trial; p. 65378. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui S., Cui J. Progress of researches on the mechanism of cupping therapy. Zhen ci yan jiu. Acupunct. Res. 2012;37:506–510. 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin J. Alternative therapy: cupping for asthma. Chest. 2011;139:475. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niasari Majid, Kosari Farid, Ahmadi Ali. The effect of wet cupping on serum lipid concentrations of clinically healthy young men: a randomized controlled trial. J Alternative Compl Med. 2007;13:79–82. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.4226. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustafa Layla A., Dawood Rukzan M., Al-Sabaawy Osama M. Effect of wet cupping on serum lipids profile levels of hyperlipidemic patients and correlation with some metal ions. Raf. J. Sci. 2012;23:128–136. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao P., Yang Y., Guan L. Effects of bloodletting pricking, cupping and surrounding acupuncture on inflammation-related indices in peripheral and local blood in patients with acute herpes zoster. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2016;36:37–40. 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaskilampi T., Hanninen O. Cupping as an indigenous treatment of pain syndromes in Finnish culture and social context. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:1893–1901. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90450-6. 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aeeni Z., Afsahi A., Rezvan H. An investigation of the effect of wet cupping on hematology parameters in mice. Pejouhesh. 2013;37:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chirali Ilkay Zihni. Traditional Chinese Medicine Cupping Therapy. third ed. Churchill Livingstone. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2014. pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lund I., Lundeberg T. Are minimal, superficial or sham acupuncture procedures acceptable as inert placebo controls? Acupunct Med. 2006;24:13–15. doi: 10.1136/aim.24.1.13. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato A. Neural mechanisms of autonomic responses elicited by somatic sensory stimulation. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 1997;27:610–621. doi: 10.1007/BF02463910. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arslan M., Yeşilçam N., Aydin D., Ramazan Y., Şenol D. Wet cupping therapy restores sympathovagal imbalances in cardiac rhythm. J Alternative Compl Med. 2014;20:318–321. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khalil Ahmad Mohammad, Al-Qaoud Khaled Mahmoud, Shaqqour Hiba Mohammad. Investigation of selected immunocytogenetic effects of wet cupping in healthy men. Spatula DD. 2013;3:51–57. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akbari A., Zadeh S.M.A.S., Ramezani M., Zadeh S.M.S. The effect of hijama (cupping) on oxidative stress indexes & various blood factors in patients suffering from diabetes type II. Switzerland Res Park J. 2013;102:788–793. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Bo, Li Ming-yue, Liu Pei-dong, Guo Yi, Chen Ze-lin. Alternative medicine: an update on cupping therapy. Q J Med. 2015;108:523–525. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norouzali T., Roostayi M.M., Dehghan M.F., Abbasi M., Akbarzadeh B.A., Khaleghi M.R. The effects of cupping therapy on biomechanical properties in wistar rat skin. J Res Rehab Sci. 2014;9:841–851. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emerich M., Braeunig M., Clement H.W., Lüdtked R., Hubera R. Mode of action of cupping—local metabolism and pain thresholds in neck pain patients and healthy subjects. Compl Ther Med. 2014;22:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian H., Tian Y.J., Wang B., Yang L., Wang Y.Y., Yang J.S. Impacts of bleeding and cupping therapy on serum P substance in patients of postherpetic neuralgia. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2013;33:678–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin M.L., Lin C.W., Hsieh Y.H. Bioelectronics and Bioinformatics (ISBB), IEEE International Symposium on. IEEE; 2014. Evaluating the effectiveness of low level laser and cupping on low back pain by checking the plasma cortisol level; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Huijuan, Zhu Chenjun, Liu Jianping. Wet cupping therapy for treatment of herpes zoster: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:48–54. 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Refaat B., El-Shemi A.G., Ebid A.A., Ashshi A., BaSalamah M.A. Islamic wet cupping and risk factors of cardiovascular diseases: effects on blood pressure, metabolic profile and serum electrolytes in healthy young adult men. Altern IntegMed. 2014;3:151. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erras Samar, Benjilali Laila, Essaadouni Lamiaa. Wet-cupping in the treatment of recalcitrant oral and genital ulceration of Behçet disease: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2013;12:615–618. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao H. Cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences. 2014;1:49–61. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 45.AlBedah A. The use of wet cupping for persistent nonspecific low back pain: randomized controlled clinical trial. J Alternative Compl Med. 2015;21:504–508. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0065. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan Q-l, Guo T-m, Liu L., Sun F., Zhang Y-g. Traditional Chinese medicine for neck pain and low back pain: a systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao H., Hu H., Colagiuri B., Liu J. Medicinal cupping therapy in 30 patients with fibromyalgia: a case series observation. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18:122–126. doi: 10.1159/000329329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gur A. Physical therapy modalities in management of fibromyalgia. Curr Pharm. 2006;12:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michalsen A., Bock S., Lüdtke R., Rampp T. Effects of traditional cupping therapy in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2009;10:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aleyeidi N., Aseri K., Kawthar A. The efficacy of wet cupping on blood pressure among hypertension patients in jeddah, Saudi Arabia: a randomized controlled trial pilot study. Altern IntegMed. 2015;4:183. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmed A., Khan R.A., Ali A.A., Ahmed M., Mesaik M.A. Effect of wet cupping therapy on virulent cellulitis secondary to honey bee sting–a case report. J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;7:123–125. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao H. Clinical research evidence of cupping therapy in China: a systematic literature review. BMC Compl Alternative Med. 2010;10:70. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albedah Evaluation of wet cupping therapy: systematic review of randomized clinical trials, the journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2016;22:768–777. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0193. 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moayedi M., Davis K.D. Theories of pain: from specificity to gate control. J Neurophysiol. 2012;109:5–12. doi: 10.1152/jn.00457.2012. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Le Bars D., Villanueva L., Willer J.C. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC) in animals and in man. Acupunct Med. 1991;9:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ann Lett R.M. Reflex Zone Therapy for Health Professionals. first ed. 2000. pp. 2–20. Amazon.com. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moncada S., Palmer R.M., Higgs E.A. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacology. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniali F., VaezeMahdavi M.R., Ghazanfari T., Naseri M. Comparing of venous blood with Hijama blood according to biochemical and hematological factors and immunological responses. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;13:78–87. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gok Sumeyye, Liyagil Kazanci Fatma nur Haciev, Erdamar Husamettin, Gokgoz Nurcan. Is it possible to remove heavy metals from the body by wet cupping therapy (Al-hijamah)? Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2016;15:700–704. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calvino B., Grilo R.M. Central pain control. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Musial F., Michalsen A., Dobos G. Functional chronic pain syndromes and naturopathic treatments: neurobiological foundations. Forsch Komplementmed. 2008;15:97–103. doi: 10.1159/000121321. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J.I., Lee M.S., Lee D.H., Boddy K., Ernst E. Cupping for treating pain: a systematic review. Evid Based Compl. Alternat Med. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moayedi Massieh, Davis Karen D. Theories of pain: from specificity to gate control. Theories of pain: from specificity to gate control. J. Neurophysiol. 2013;109:5–12. doi: 10.1152/jn.00457.2012. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Melzack Ronald, Wall Patrick D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. New Series. 3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Staud R. Peripheral pain mechanisms in chronic widespread pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.010. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Melzack R., Wall P.D. On the nature of cutaneous sensory mechanisms. Brain. 1962;85:331–356. doi: 10.1093/brain/85.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wall Patrick D. Cord cells responding to touch, damage, and temperature of skin. J. Neurophysiol. Publ. 1960;23(2):197–210. doi: 10.1152/jn.1960.23.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tiran Denise, Chummun Harry. The physiological basis of reflexology and its use as a potential diagnostic tool. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2005;11:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ctnm.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Michalsen A., Bock S., Lüdtke R., Rampp T. Effects of traditional cupping therapy in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2009;10:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wijk Gerrit van, Veldhuijzen Dieuwke S. Perspective on diffuse noxious inhibitory controls as a model of endogenous pain modulation in clinical pain syndromes. J Pain. 2010;11:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.009. 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernaba M., Johnson K.A., Kong J.T., Mackey S. Conditioned pain modulation is minimally influenced by cognitive evaluation or imagery of the conditioning stimulus. J Pain Res. 2014;7:689–697. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S65607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bernaba M., Johnson K.A., Kong J.T., Mackey S. Conditioned pain modulation is minimally influenced by cognitive evaluation or imagery of the conditioning stimulus. J Pain Res. 2014;7:689–697. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S65607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherman Lisa. Evidence base. J Chin Med. 2016:12. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schouenborg Jens, Dickenson Anthony. The effects of a distant noxious stimulation on A and C fibre-evoked flexion reflexes and neuronal activity in the dorsal horn of the rat. Brain Res. 1985;328:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91318-6. 1. 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marquardt H. Thieme; Stuttgart: 2000. Reflexotherapy of the Feet. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sato A., Sato Y., Schmidt R.F. The impact of somatosensory input on autonomic functions. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;130:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaban T. Cupping Therapy Encyclopedia. first ed. Createspace Independent Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Faraci F.M. Role of nitric oxide in regulation of basilar artery tone in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:1216–1221. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1216. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greener M. Now You're signaling, with gas. Scientist. 2004;18:17. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma S.X. Enhanced nitric oxide concentrations and expression of nitric oxide synthase in acupuncture points/meridians. J Alternative Compl Med. 2003;9:207–215. doi: 10.1089/10755530360623329. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gnarro Louis J., Buga Georgette M., Wood Keith S., Byrns Russell E., Chaudhuri Gautam. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schäffer Michael R., Tantry Udaya, Gross Steven S., Wasserkrug Hannah L., Barbul Adrian. Nitric oxide regulates wound healing. J Surg Res. 1996;63(1):237–240. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jin L., Liu Y.Y., Meng X.W., Li G.L., Guo Y. A preliminary study of blood flow under the effect of cupping on back. JCAM. 2010;26:11. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tian Y.Y., Qin L.N., Zhang W.B. Effect of cupping with different negative pressures on dermal blood flow. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2007;32:184. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ernst M., Lee M.H.M. Sympathetic effects of manual and electrical acupuncture of the Tsusanli knee point: comparison with the Hoku hand point sympathetic effects. Exp Neurol. 1986;94(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ke Zeng, Jian-wei Wang. Clinical application and research progress of cupping therapy. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2016;14:300–304. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 87.El-Domyati Moetaz, Saleh Fatma, Barakat Manal, Mohamed Nageh. Evaluation of cupping therapy in some dermatoses. Egypt. Dermatol. Online J. 2013;9:2. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wei Xiao, Ying Wang, Hong-bing Kong. Effects of cupping at back-shu acupoints on immunologic functions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during stable stage. J Anhui Tradit Chin Med Coll. 2010;05 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ahmed Sahbaa M. Immunomodulatory effects of blood letting cupping therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Egypt J Immunol. 2005;12:39–51. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mahdavi Vaez, Reza Mohammad. A Compendium of Essays on Alternative Therapy. Publishing Press Manager IvonaLovric; 2012. Evaluation of the effects of traditional cupping on the biochemical, hematological and immunological factors of human venous blood. Review paper; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ye L.H. Effect of cupping on human body immune function. XiandaiKangfu. 1998;23:1109–1121. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang L., Tang L.T., Tong X.L., Jia H., Zhang Y.Z., Jiu G.X. Effect of cupping therapy on local hemoglobin in human body. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2001;21:619–621. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhong L., Li L., Li J., Liao Y.L., Huang S. Effect of moving cupping on the immune function of red blood cells. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 1999;19:367–368. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen L.H., Li X.B. Clinical application of cupping therapy. Jilin Zhongyiyao. 2004;24:60–61. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guo Yang, Chen Bo, Wang Dong-qiang. Cupping regulates local immunomodulation to activate neuralendocrine-immune worknet. Compl Ther Clin Pract. 2017;28:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Daniali F., VaezeMahdavi M.R., Ghazanfari T., Naseri M. Comparing of venous blood with Hijama blood according to biochemical and hematological factors and immunological responses. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;13:78–87. 1. (58) [Google Scholar]

- 97.Akbari Ahmad, Ali Seyed Mohammad, Zadeh Shariat, Ramezani Majid, Seyed, ShariatZadeh Mahdi. The effect of hijama (cupping) on oxidative stress indexes & various blood factors in patients suffering from diabetes type ii. Switz. Res. Park J. 2013;102:9. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sheykhu A.M.A. Razavieh Publishment.es; Tehran: 2008. Davaa'olAjib. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fazel A., HossaniVaez Z., Saghebi A., Esmaeili H. Effect of Wet cupping on serum lipoproteins concentrations of patients with hypercholesterolemia. Mashhad J NurMidwif. 2008;9:13–18. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shi-jun Zhang, Jian-ping Liu, Ke-qiang He. Treatment of acute gouty arthritis by blood-letting cupping plus herbal medicine. J Tradit Chin Med. 2010;18:1. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(10)60005-2. 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Science and Research Branch . International Conference on Biophysical Chemistry (ICBC); 2012. The Effects of Wet Cupping on the Structure and Function of Extracted Hemoglobin from Diabetic Volunteers. [Google Scholar]