Abstract

In recent years, growing attention has been given to traditional medicine. In traditional medicine a large number of plants have been used to cure neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other memory related disorders. Crocus sativus (C. sativus), Nigella sativa (N. sativa), Coriandrum sativum (C. sativum), Ferula assafoetida (F. assafoetida), Thymus vulgaris (T. vulgaris), Zataria multiflora (Z. multiflora) and Curcuma longa (C. longa) were used traditionally for dietary, food additive, spice and various medicinal purposes. The Major components of these herbs are carotenoids, monoterpenes and poly phenol compounds which enhanced the neural functions.

These medicinal plants increased anti-oxidant, decreased oxidant levels and inhibited acetylcholinesterase activity in the neural system. Furthermore, neuroprotective of plants occur via reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and total nitrite generation.

Therefore, the effects of the above mentioned medicinal and their active constituents improved neurodegenerative diseases which indicate their therapeutic potential in disorders associated with neuro-inflammation and neurotransmitter deficiency such as AD and depression.

Keywords: Traditional medicine, Medicinal plant, Spice, Memory, Nervous system

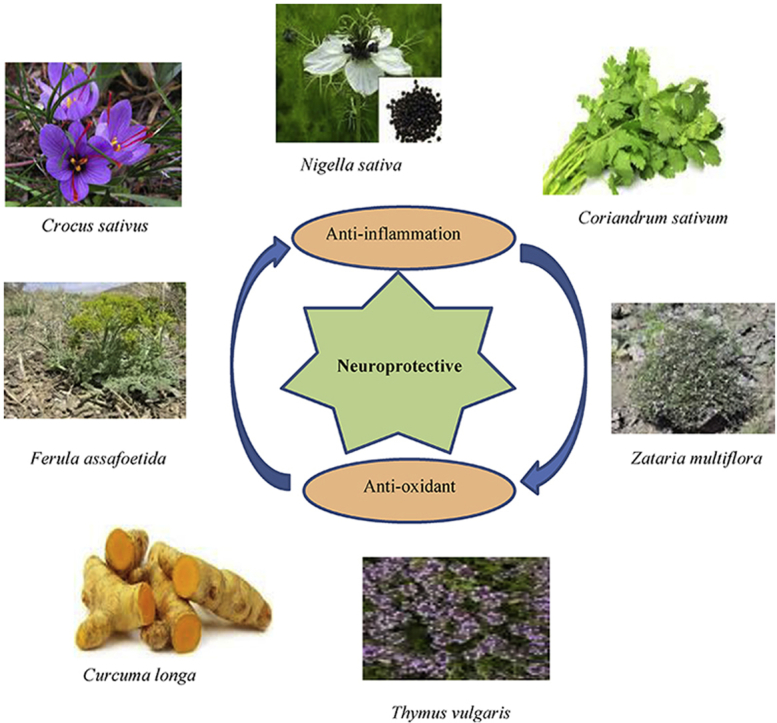

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's Disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, Multiple Sclerosis (MS) results in slow neuronal death that accompanied with losing cognitive functions and sensory dysfunction.1 Recently, these diseases associated with different multifactorial etiologies, social, and financial problems.2 Anti-inflammatory agents have also been suggested to postpone the progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. Different studies have shown that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce the risk of developing AD.4,5 Pathological processes including inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and genetic factors lead to neuronal degeneration in Parkinson's disease (PD).6 It has been reported that excessive lipid peroxidation may destroy cholinergic neurons in AD7 and dopaminergic neurons in PD.8 Different enzymatic antioxidant such as superoxide dismutase (SOD)9 and non-enzymatic antioxidant such as total thiol groups10 exist in the brain. Central nervous system (CNS) also contains high level of polyunsaturated fatty acids is more sensitive to peroxidation reactions (9). Low antioxidant activity of the brain with respect to other tissues has been made the brain tissue susceptible to oxidative damage.11

In traditional medicine, the organs of plant such as: leaves, stems, roots, flowers, fruits and seeds were used as alternative and complementary therapy. Some derived components from herbs such as resveratrol, curcumin, ginsenoside, polyphenols, triptolide, etc. have neuroprotective effects.12 Herbal products contain of complex active components or phytochemicals like flavonoids, alkaloids and isoprenoids. Therefore, it is frequently difficult to determine which component(s) of the herb(s) has more biological activity.13,14

In the present review study, it was aimed to highlight the useful effects of different medicinal plant which used traditionally for dietary, food additive, spice and various medicinal purposes on induced neurotoxicity.

2. Methods

The information's of this review were obtained from databases such as, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Scopus, and IranMedex until the end of August 2016. The search terms were included “neuroprotective” or “neurotoxicity” and “Crocus sativus”, “Nigella sativa”, “Coriandrum sativum”, “Ferula assafoetida”, “Thymus vulgaris”, “Zataria multiflora”, and “Curcuma longa”. All studies such as, in vitro studies, animal studies, review articles and clinical studies with the outcome of changes in the neurotransmitter releasing, behavioural changes, oxidant/anti-oxidant parameters and pro-inflammatory cytokines were included. Letter to the Editor and Unpublished data were the exclusion criteria.

3. Neuroprotective effects of medicinal plants

3.1. Crocus sativus

Crocus sativus L (C. sativus), commonly known as saffron belongs to the Iridaceas family, Crocoideae superfamily which is cultivated in many countries including Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey and Spain.15 Saffron consists dried and dark-red stigma with a small portion of the yellowish style attached of C. sativus. It used mainly as herbal medicine in various regions in the world.16

Saffron possesses 150 different compounds including carbohydrates, polypeptides, lipids, H2O, minerals and vitamins. Crocins are the main biologically active ingredients of saffron, a family of red-colored and water-soluble carotenoids, which are all glycosides of crocetin. Also, saffron has four main bioactive components such as, crocin, crocetin, picrocrocin and safranal. Another constituent of saffron was Picrocrocin which has a bitter taste.17

3.1.1. Medicinal properties of C. sativus

In Iranian traditional medicine, Crocus sativus is used to treat cognitive disorders. Recently C. sativus constituents were used to treat some neural disorders and to relax smooth muscle.18, 19, 20 The anticonvulsant and anti-Alzheimer properties of saffron extract in humans and animal models have been reported.18 The efficacy of C. sativus in the treatment of mild to moderate depression in clinical trial studies, and effect on brain neurotransmitter concentrations as well as its interaction with the opioid system were reviewed.18 C. sativus and its main component, crocin, possess potent antioxidant effects via reducing of MDA level.21,22 The administration of C. sativus extract (100 mg/kg, p.o.) before induction of cerebral ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) significantly reduced glutamate and aspartate concentrations, SOD, catalase and K-ATPase activities induced by ischemia in rats.23 In addition, administration of C. sativus extract (200 mg/kg) and honey syrup for 45 days reduced the aluminum chloride-induced neurotoxicity in mice.24

Administration of C. sativus (30 mg/day) for treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in the patients of 55 years and older was found to be as effective as donepezil and the frequency of saffron extract side effects was similar to those of donepezil except for vomiting.25 Similarly, the uses of saffron in 46 patients with mild-to-moderate AD for 16 weeks improved the cognitive functions.26 Saffron extract (30 mg/day) for six-week was effective in the treatment of mild to moderate depression similar to the effects of fluoxetine and imipramine (100 mg/day).27 In a double-blind clinical trial the efficacy of co-administration of hydro-alcoholic extract of C. sativus (40 and 80 mg) and fluoxetine (30 mg/day) for six weeks was investigated. The results showed that a dose of C. sativus 80 mg and fluoxetine (30 mg/day) was effective than that of C. sativus 40 mg to treat mild to moderate depressive disorders.28

3.2. Nigella sativa

Nigella sativa L. (N. sativa) is an annual herbaceous and belonging to Ranunculaceae family, which widely grown in the Mediterranean countries, Western Asia, Middle East and Eastern Europe. The N. sativa seeds have been added as a spice to range of Persian foods such as, bread, pickle, sauces and salads.29

Chemical components of N. sativa seeds include oil, protein, carbohydrate, and fiber. The fixed oil chemical compositions of N. sativa are linoleic acid, oleic acid, Palmitic acid, Arachidic acid, Eicosadienoic acid, Stearic acid, Linoleic acid and Myristic acid.30 The major phenolic compounds of N. sativa seeds are p-cymene (37.3%), Thymoquinone (TQ) (13.7%), carvacrol (11.77%), and thymol (0.33%).29,31,32

3.2.1. Medicinal properties of N. sativa

N. sativa as a medicinal plant is well-known for its potent anti-oxidative effects.33 It has been reported that N. sativa have protective effects on the renal damage.34 N. sativa seeds could significantly ameliorate the spatial cognitive deficits caused by chronic cerebral hypo perfusion in rats.35 Furthermore, N. sativa improved scopolamine – induced learning and memory impairment as well as reduced the AChE activity and oxidative stress of the rats brain.36 Antioxidant effects of N. sativa oil on the patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) showed N. Sativa reduced the serum level of IL-10, MDA and NO. N. sativa also improved inflammatory responses and reduced oxidative stress in patients with RA.37 In the other clinical trial, 40 healthy volunteers were divided into the treatment with capsules of N. sativa (500 mg) and placebo (500 mg) twice daily for 9 weeks. N. sativa enhanced memory, attention and cognition compared to the placebo group.38 N. sativa (500 mg) also decrease anxiety, to stabilize mood and to modulate cognition in the human model after 4 weeks.39 Neuroprotective effects of N. sativa and thymoquinone (TQ) (its major components) on various nervous system disorders such as Alzheimer disease, epilepsy and neurotoxicity have been reviewed.40

3.3. Coriandrum sativum

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.), is an annual herb of the parsley family (Apiaceae). This plant is generally called Geshniz in Persian. Coriandrum sativum is native to the Mediterranean region and is extensively grown in all over the world.42,43

The aliphatic aldehydes (mainly C10-C16 aldehydes) with fetid-like aroma are predominant in the fresh herb oil44 whereas major components in the oil isolated from coriander fruit include linalool and some other oxygenated monoterpenes and monoterpene hydrocarbons.45 Coriander is also a potential source of lipids such as petroselinic acid and a high amount of essential oils (EO) that are very important for growth and brain functions. The main coriander EO is linalool, linoleic and linolenic acids.46 Coriander seed oil was contains linalool (60–70%) and 20% hydrocarbons but the composition of the herb oil was completely differs from the seed oil.47

3.3.1. Medicinal properties of C. sativum

In folk medicine, coriandrum sativum (C. sativum) was widely used as digestive agent. The seed extract of C. sativum was used in lotions and shampoos and exerts antimicrobial and anti-rheumatoid effects.48 In Iranian traditional medicine, C. sativum has been suggested to relive insomnia.49,50 A combination of the fresh leaves extract and tea, or crushed of plant seeds as a single dose before sleeping have been suggested to relieve anxiety and insomnia.49 Similar uses of C. sativum seed have been shown in other folk medicines.51 The leaves extract of C. sativum (200 mg/kg) showed an anxiolytic effect which was presented by increasing the time spent in open arms and the percentage of open arm entries.52 C. sativum fruit extract (100 and 200 mg/kg, i.p.) increased the time spent in the open arms and entries into the open arms. Locomotion activity and frequency of rearing also decreased in the groups treated by 200 mg/kg (i.p.) of the extract. Furthermore, C. sativum extract at 100 and 200 mg/kg increased the time spent in social interaction.53 Anticonvulsant activity of aqueous (0.5 g/kg, i.p.) and ethenolic extracts (3.5 and 5 g/kg, i.p.) of coriander seeds were studied using pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) and the maximal electroshock seizure models. These extracts decreased the duration of tonic seizures and showed a significant anticonvulsant activity in the maximal electroshock test. In addition both extracts especially ethenolic extract (5 g/kg, i.p.) similar to phenobarbital (20 mg/kg) prolonged onset latencies of clonic convulsions.54

3.4. Ferula assafoetida

Asafoetida (F. assafoetida L.) belongs to the Apiaceae family which obtained from the exudates of the living underground rhizome or tap roots of the plant. F. assafoetida or gum-resin is known as “Anghouzeh”, “Khorakoma” and “Anguzakoma” in Iran.55 It has been used in traditional medicine and as a spice in different foods in India and Nepal.55

E-1-propyl sec-butyl disulfide is a major component56 and 25 compounds were identified in the hydrodistilled oil. E-1-propenyl sec-butyl disulfide (40.0%) and germacrene B (7.8%) are the major components of Ferula assa-foetida.56

3.4.1. Medicinal properties of F. assafoetida

F. asafoetida (Apiaceae) is considered by researchers due to its medicinal and nutritional properties. Roots, young shoots and leaves of plant are eaten as vegetable. Leaves of Ferula asafoetida possess anthelmintic, carminative and diaphoretic properties and the root of plant is used as antipyretic.57 In addition, F. asafoetida is used for treatment of various diseases including asthma, epilepsy, stomachache, flatulence, intestinal parasites, weak digestion and influenza in traditional medicine.58 It has been also reported that oleo-gum resin of F. asafoetida possesses sedative, expectorant, analgesic, carminative, stimulant, antiperiodic, ant-diabetic, anti-spasmodic, emmenagogue, vermifuge, laxative, anti-inflammatory, contraceptive and anti-epileptic effects.59 Effects of F. asafoetida on muscarinic receptors and possible mechanisms for functional antagonistic of guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle have been studied.60,61 The relaxant effect of F. assafoetida on smooth muscles and its possible mechanisms have been reviewed.62 In pharmacological and biological studies, the ole-gum- resin of Ferula asafoetida have been revealed to have antioxidant, antiviral, antifungal, anti-diabetic, molluscicidal, antispasmodic and antihypertensive effects.55 In a study, acute and sub-chronic toxicity of F. asafoetida was evaluated and the results indicated that single oral administration (500 mg/kg) and repeated doses (250 mg/kg) for 28 days of this plant did not induce mortality and obvious toxicological signs in rats.63 It has also been documented that oleo gum resin of F. asafoetida can enhance regeneration and re-myelination and decreases the rat of lymphocyte infiltration in the neuropathic tissue in mice; therefore it acts as a neuroprotective and nerve simulative agent in peripheral neuropathy.64 Scientific evidences have also shown that F. asafoetida resin can potentially inhibit monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) and it can be used in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases.65 Meanwhile, Ferula asafoetida has been reported to have acetylcholinestrase (AChE) inhibiting property in vitro assay and in vivo on snail nervous system. Researchers have proposed that memory increasing effect of Ferula asafoetida could be attributed to inhibitory effect of this plant on AChE in the rat brain.66 In behavioural models, such as elevated plus maz, the extract of plant dose-dependently improved memory in rats. In another behavioural model, passive avoidance test, the lower dose of extract (200 mg) could not improve memory whereas in high dose (400 mg) it ameliorated memory.67 Additionally, it has been documented that the extract of F. asafoetida applies a considerable anticonvulsant effect in Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) and amygdala-kindled rats. Researchers investigated the effect of two doses of ferula asafoetida (50 and 100 mg/kg) on parameters of seizure and the results revealed that dose 100 mg/kg exerts the better anticonvulsant effect than 50 mg.59

3.5. Thymus vulgaris

Thymus vulgaris (T. vulgaris) is a plant that is a member of Lamiaceae family which are strongly aromatic. This plant is consist of approximately 38 species and is distributed in subtropical countries.68

The phenols, thymol (40%) and carvacrol (15%) are main components of TV. It was contains less amounts of phenol during the winter. Also, thymol methyl ether (2%), cineol, cymen, pinene, borneol and esters are components in the essential oil.68

3.5.1. Medicinal properties of T. vulgaris

Thymus vulgaris (Thyme) is a subshrub native to the western Mediterranean region which is widely used as spice to add a distinctive flavour to food. In the traditional medicine, thyme is part of herbal teas and infusions.69 It has been documented that bioactive compounds of thyme such as thyme essential oil (TEO) constituents, flavonoids and phenolic acids, natural terpenoid thymol and phenol isomer carvacrol, possess antioxidant, antimicrobial, antitussive, antispasmodic, and expectorant effects.70,71 Researchers have reported that tocols and phenolic in thymus vulgaris oil (TO) can directly react with free radicals and inhibit lipid peroxidation.72 It has been also reported that treatment with thymol results in improvement of antioxidant status in rat brain.73 In addition, the results of behavioural studies have demonstrated that the extract of thyme can induce anxiolytic effects in rat when it was orally administered for 1-week. In confirmation of this report extract of thyme enhances the percentage of both the entries and the time spent in the open arms of the maze.74 The results of animal studies also revealed that kaemfrol in thyme extract applies anxiolytic effects in the elevated plus maze (EPM) in mice.75 Carvacrol derived from this plant has also been indicated to have anxiolytic effects in the plus maze test.76 Bioactive monoterpenes in thyme extract such as linalool have been reported to be able to decrease the level of anxiety in animals.77 The essential oil of thyme has also been suggested to have a dose dependent protective effect against toxicity of alfatoxins.78 In addition, it has been documented that thymol acts centrally via mimicking or facilitating GABA action and modulates GABAA receptor.79 Therefore, it can apply the significant anticonvulsant and antiepileptogenic effects. Recently, neuroprotective and improvement effects of thymol, a bioactive monoterpene isolated from thymus vulgaris, on amyloid β or scopolamine-caused cognitive impairment in rats was documented.80 Researchers have suggested that neuroprotective effects of thymol can attribute to its potential effect on GABA-mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission.81 Meanwhile, researchers reported that TO could modulate cholinergic function via enhancing synaptic acetylcholine (Ach) and nicotinic Ach receptor activity.82 Additionally, antidepressant effects of thymol were documented. Deng et al. reported that thymol administration significantly shortened the immobility time in tail suspension tests (TST) and forced swimming test (FST) and restored the reduction of the hippocampal levels of serotonin (5- HT) and norepinephrine (NE) in chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)- induced depressive mice.80

3.6. Zataria multiflora

Zataria multiflora (Z. multiflora) is belonging to the Lamiaceae family.83

It have consist of p-cymene derivatives: multi-flotriol (1), multi-flrol (2), a new aromatic ester of p-hydroxy benzoic acid (3) and three known constituents: dihydroxyaromadendrane,84 luteolin85 and a-tocopherolquinone.86 The main components of the plant oil were thymol (37.59%), carvacrol (33.65%); PARA-cymene (7.72%), γ -terpinene (3.88%) and β-caryophyllene (2.06%).87

3.6.1. Medicinal properties of Z. multiflora

Z. multiflora contains various compounds including terpens, luteolin, 6- hydroxyluteolin glycosides, di-, tri, and tetra-ethoxylated which could be responsible for the therapeutic effects of it88 Z. multiflora Boiss essential oil (ZEO) possesses preservative effects whereas vigorous taste and aroma have limited its usage as food preservative in high amounts.89 In Iranian traditional medicine, the plant is used for its analgesic, antiseptic and carminative effects.88 It has also been documented that the essential oil of Z. multiflora has antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal properties in in vitro.89,90 The results of studies have indicated that the ZEO exhibited more potent antioxidative effect than pomegranate juice.89 Antibacterial,90 immunoregulatory91,117 and anti-inflammatory92,118 effects of this plant have also been reported. In addition, it has been reported that the Aβ-caused learning and memory impairments could be restored by i.p. administration of Z. multiflora essential oil in rats. Therefore zataria multiflora essential oil was considered to be as a worth source of natural therapeutic agent for attenuating cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease (AD) by researchers.93

3.7. Curcuma longa

Curcuma longa (C. longa) is a member of the Zingiberaceae family and is cultivated in the countries of Southeast Asia.94

The active constituents of turmeric are the flavonoid curcumin (diferuloylmethane) and various volatile oils, including tumerone, atlantone, and zingiberone. Other constituents include sugars, proteins, and resins. The best-researched active constituent is curcumin, which comprises 0.3–5.4% of raw turmeric.95

3.7.1. Medicinal properties of C. longa

Some plants such as Curcuma longa contain a natural polyphenol and non-flavonoid compound called curcumin. Curcumin is known for its several biological and medicinal effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and so on. Curcumin therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases has garnered great interest in recent years.6 Kulkarni reported that curcumin water soluble extract is able to raise dopamine, norepinephrine and 5-HT levels in CNS.96 Curcumin extracted from Curcuma longa have been reported to have inhibition effects on PD, ROS production, apoptosis, platelet aggregation, cytokines production, cyclooxygenase enzyme activity, brain oxidative damage, cognitive deficits in cell culture and animal models.97,98 The protective effects of C. longa extract (1000 mg/kg, body weight, per oral) on oxidative99 and renal damage have been reported.100

It has been reported that administration of curcumin (50, 100, 200 mg/kg) ameliorated cognitive deficits and mitochondrial dysfunctions symptoms in mice.101 Curcumin has also been indicated to exert neuroprotective effects in neuronal degenerative disorders and cerebral ischemia.102,103 Scientific evidences demonstrate that curcumin protects the rat brain against focal ischemia through upregulation transcription factor Nrf2 and HO-1expretion.104 Additionally, researchers suggested that curcumin debilitates glutamate neurotoxicity in the hippocampal of rat via suppressing ER stress-related TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammation activation.105 Linlin et al. also proposed that curcumin protects rats brain against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through increasing neuron survival rate, inflammatory cytokine activity and activating JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway.106 It has been suggested that curcumin protects the brain against oxyhemoglobin-induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress in vitro model of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Xia LI).107

The neuroprotective effects of curcumin in PD also are related to its antioxidant properties. Wang reported that curcumin restor ROS intracellular accumulation108 in human cell line SH-SY5Y exposed to 6-OHDA.109 Administration of curcumin (60 mg/kg, body weight, per oral) for three weeks has amended striatum neuronal degeneration in 6-OHDA lesioned rats.110 Curcumin protected the neurons against ROS via restoring the GSH decreased levels.111 Curcumin increased SOD levels in the lesioned striatum of 6-OHDA mice112 and MES23.5 cells induced the neurotoxin 6-OHDA.108 Curcumin has been reported to protect the axons against LPS degeneration.113 Curcumin neuroprotective effects might be mediated by overexpression of BCl-2 which is inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) antagonist. Therefore, curcumin is effective in improvement of NO-mediated degeneration.114 Oral administration of 150 mg/kg/day curcumin for 1 week reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and total nitrite generation in the striatum of MPTP-induced mice.115 Furthermore, curcumin decreased activation of NF-κB in LPS116 and 6-OHDA-induced inflammatory.108

4. Medicinal properties of medicinal herbs and their clinical application

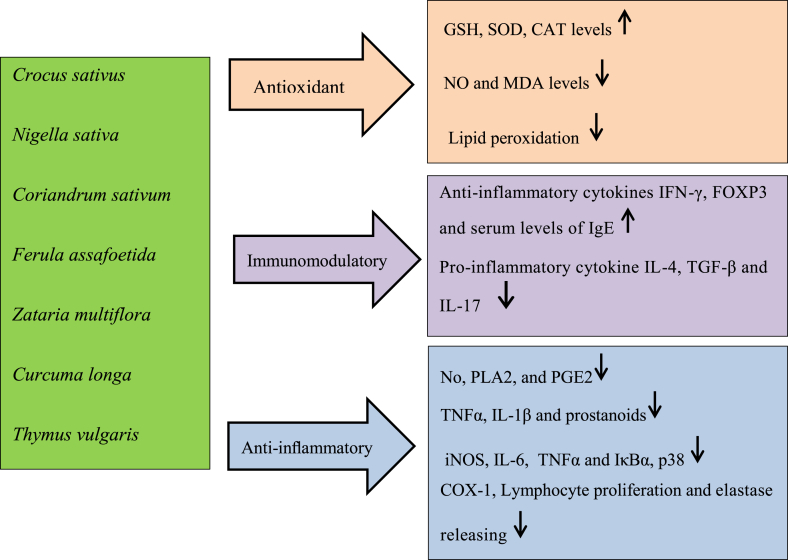

Different medicinal plants showed the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects which may have potential therapeutic effects in various nervous system disorders. The results of studies also imply that beneficial effects of the plants on neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer and Parkinson disease are mainly due to the interactions with the cholinergic, dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems. Regarding the anticonvulsant, analgesic effects of the plants interaction with the GABA and opioid system might be suggested. Different mechanism of medical properties of medicinal herbs was summarized in Fig. 1. The effectiveness of medicinal plants on different disorder as clinical studied were showed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Different mechanism of medical properties of medicinal herbs. GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; NO, Nitric oxide; MDA, malondialdehyde; PLA2: Phospholipase A2; PGE2: Prostaglandin-E2; IL-1β, Interleukin-1β; COX-1, Cyclooxygenase-1; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Table 1.

The effects of medicinal plants for treatment of various disorders, a clinical evidence.

| Medicinal plants | Model of study | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. Sativus | Depressant patients | The effect of C. Sativus similar to imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression | 119 |

| C. Sativus could produce a significantly better the outcome on the Hamilton depression rating scale than the placebo | 120 | ||

| The effect of C. Sativus similar to fluoxetine in the treatment depression | 121 | ||

| Was effective to treatment of mild to moderate depressive disorders |

122 | ||

| N. sativa | Asthmatic patients |

Improvement of all asthmatic symptoms, chest wheeze and pulmonary function test (PFT) values | 123 |

| Lesser effectiveness on pulmonary function test and sGaw than theophylline | 124 | ||

| Sulfur mustard espoused patients | Decreasing the use of inhaler and oral β-agonists and oral corticosteroid in the study group | 125 | |

| Allergic patients | Decreasing the IgE and eosinophil count and plasma triglycerides. Increasing the HDL cholesterol | 126 | |

| C. sativum | Diabetic patients | Significant hypoglycemic activity in type-2 diabetic patients |

127 |

| C. longa | Peptic ulcer patients | The abdominal pain and discomfort satisfactorily subsided in the first and second week. | 128 |

5. Conclusion

In this review we propose to focus on neurotoxicity in various studies (in vitro and in vivo) and investigated the effects of medicinal plants on neural system. The mentioned medicinal plants play their protective roles via increased SOD and catalase levels, restoration of GSH, decreased MDA levels and also protects of neurons against ROS as antioxidant activities. Some protective effects of these natural compounds may be due to reduction of Ca2+, Na+ and enhancement of K+ level or ‘anti-glutamatergic’ effect. The neuroprotective effects of the mentioned plants occur via reduction of inflammatory cytokines as well as enhancement of anti-inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of the acetylcholinesterase activity and decreased MDA levels in the neural system via modulating GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons, and also increasing amount of amino acids and serotonin (5-HT) in the neurotransmitters systems. Furthermore, the data of the basic and clinical evidence indicated that anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunoregulatory effects of some herbs on various disorders. This findings help to recommend the use of these herbs and main compound from natural resources for drug development and more investigation in the clinical studies for future were suggested.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to the Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for the partial support of this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

References

- 1.Mattson M.P. Metal-catalyzed disruption of membrane protein and lipid signaling in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:37–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena S., Caroni P. Selective neuronal vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases: from stressor thresholds to degeneration. Neuron. 2011;71:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitner John CS. The role of anti-inflammatory drugs in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Ann Rev Med. 1996;47:401–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGeer P.L., Schulzer M., McGeer E.G. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer's disease A review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology. 1996;47:425–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu W., Zhuang W., Zhou S., Wang X. Plant-derived neuroprotective agents in Parkinson's disease. Am J Trans Res. 2015;7:1189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olcese J.M., Cao C., Mori T. Protection against cognitive deficits and markers of neurodegeneration by long-term oral administration of melatonin in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:82–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khaldy H., Escames G., Leon J., Vives F., Luna J., Acuña-Castroviejo D. Comparative effects of melatonin, l-deprenyl, Trolox and ascorbate in the suppression of hydroxyl radical formation during dopamine autoxidation in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2000;29:100–107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2000.290206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camello-Almaraz C., Gomez-Pinilla P.J., Pozo M.J., Camello P.J. Age-related alterations in Ca2+ signals and mitochondrial membrane potential in exocrine cells are prevented by melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2008;45:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tewari A., Mahendru V., Sinha A., Bilotta F. Antioxidants: the new frontier for translational research in cerebroprotection. J Anaesthes Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:160. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.130001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floyd R.A., Carney J.M. Free radical damage to protein and DNA: mechanisms involved and relevant observations on brain undergoing oxidative stress. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:S22–S27. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virmani A., Pinto L., Binienda Z., Ali S. Food, nutrigenomics, and neurodegeneration—neuroprotection by what you eat! Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suk K. Regulation of neuroinflammation by herbal medicine and its implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosignals. 2005;14:23–33. doi: 10.1159/000085383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams M., Gmünder F., Hamburger M. Plants traditionally used in age related brain disorders—a survey of ethnobotanical literature. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:363–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdullaev F.I. Biological effects of saffron. BioFactors (Oxf, Engl) 1993;4:83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalali-Heravi M., Parastar H., Ebrahimi-Najafabadi H. Characterization of volatile components of Iranian saffron using factorial-based response surface modeling of ultrasonic extraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2009 Aug 14;1216:6088–6097. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bathaie S.Z., Mousavi S.Z. New applications and mechanisms of action of saffron and its important ingredients. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010 Sep;50:761–786. doi: 10.1080/10408390902773003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khazdair M.R., Boskabady M.H., Hosseini M., Rezaee R., Tsatsakis A.M. The effects of Crocus sativus (saffron) and its constituents on nervous system: a review. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2015;5:376–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseinzadeh H., Motamedshariaty V., Hadizadeh F. Antidepressant effect of kaempferol, a constituent of saffron (Crocus sativus) petal, in mice and rats. Pharmacologyonline. 2007;2:367–370. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokhtari-Zaer A., Khazdair M.R., Boskabady M.H. Smooth muscle relaxant activity of Crocus sativus (saffron) and its constituents: possible mechanisms. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2015;5:365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimi E., Oskoueian E., Hendra R., Jaafar H.Z. Evaluation of Crocus sativus L. stigma phenolic and flavonoid compounds and its antioxidant activity. Molecules. 2010;15:6244–6256. doi: 10.3390/molecules15096244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamaddonfard E., Farshid A.A., Ahmadian E., Hamidhoseyni A. Crocin enhanced functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush injury in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16:83–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saleem S., Ahmad M., Ahmad A.S. Effect of Saffron (Crocus sativus) on neurobehavioral and neurochemical changes in cerebral ischemia in rats. J Med Food. 2006;9:246–253. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shati A., Elsaid F., Hafez E. Biochemical and molecular aspects of aluminium chloride-induced neurotoxicity in mice and the protective role of Crocus sativus L. extraction and honey syrup. Neuroscience. 2011;175:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akhondzadeh S., Sabet M.S., Harirchian M. Saffron in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a 16-week, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Therapeut. 2010;35:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akhondzadeh S., Sabet M.S., Harirchian M.H. A 22-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of Crocus sativus in the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Psychopharmacology. 2010;207:637–643. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1706-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noorbala A., Akhondzadeh S., Tahmacebi-Pour N., Jamshidi A. Hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus L. versus fluoxetine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized pilot trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moosavi S.M., Ahmadi M., Amini M., Vazirzadeh B., Sari I. The effects of 40 and 80 mg hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci (JMUMS) 2014;24 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajhashemi V., Ghannadi A., Jafarabadi H. Black cumin seed essential oil, as a potent analgesic and antiinflammatory drug. Phytother Res. 2004;18:195–199. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Tahir K.E.-D.H., Bakeet D.M. The black seed Nigella sativa Linnaeus-A mine for multi cures: a plea for urgent clinical evaluation of its volatile oil. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2006;1:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatachallam S.K.T., Pattekhan H., Divakar S., Kadimi U.S. Chemical composition of Nigella sativa L. seed extracts obtained by supercritical carbon dioxide. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kacem R., Meraihi Z. Effects of essential oil extracted from Nigella sativa (L.) seeds and its main components on human neutrophil elastase activity. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006;126:301–305. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burits M., Bucar F. Antioxidant activity of Nigella sativa essential oil. Phytother Res. 2000;14:323–328. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200008)14:5<323::aid-ptr621>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohebbati R., Abbsnezhad A., Khajavi Rad A., Mousavi S., Haghshenas M. Effect of hydroalcholic extract of Nigella sativa on doxorubicin-induced functional damage of kidney in rats. Horizon Med Sci. 2016;22:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azzubaidi M.S., Saxena A.K., Talib N.A., Ahmed Q.U., Dogarai B.B.S. Protective effect of treatment with black cumin oil on spatial cognitive functions of rats that suffered global cerebrovascular hypoperfusion. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 2012;72:154–165. doi: 10.55782/ane-2012-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosseini M., Mohammadpour T., Karami R., Rajaei Z., Sadeghnia H.R., Soukhtanloo M. Effects of the hydro-alcoholic extract of Nigella sativa on scopolamine-induced spatial memory impairment in rats and its possible mechanism. Chin J Integr Med. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadi V., Kheirouri S., Alizadeh M., Khabbazi A., Hosseini H. Effects of Nigella sativa oil extract on inflammatory cytokine response and oxidative stress status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2015:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sayeed M.S.B., Asaduzzaman M., Morshed H., Hossain M.M., Kadir M.F., Rahman M.R. The effect of Nigella sativa Linn. seed on memory, attention and cognition in healthy human volunteers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148:780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayeed M.S.B., Shams T., Hossain S.F. Nigella sativa L. seeds modulate mood, anxiety and cognition in healthy adolescent males. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;152:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khazdair M.R. The protective effects of Nigella sativa and its constituents on induced neurotoxicity. J Toxicol. 2015;2015:7. doi: 10.1155/2015/841823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Small E. NRC Research Press; Ottawa: 1997. Culinary Herbs. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence B.M. A planning scheme to evaluate new aromatic plants for the flavor and fragrance industries. In: Janick J., Simon J.E., editors. New Crops. Wiley; New York: 1993. pp. 620–627. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potter T.L. Essential oil composition of cilantro. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:1824–1826. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandoni A.L., Mizrahi I., Juárez M.A. Composition and quality of the essential oil of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) from Argentina. J Essent Oil Res. 1998;10:581–584. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahib N.G., Anwar F., Gilani A.H., Hamid A.A., Saari N., Alkharfy K.M. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.): a potential source of high-value components for functional foods and nutraceuticals-a review. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1439–1456. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guenther E. REK Publishing Company; Florida, USA: 1950. The Essential Oil. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yusuf M., Chowdhuty J.U., Wahab M.A., Begum J. Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; Bangladesh: 1994. Medicinal Plants of Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mir H. vol. 1. Persian; 1992. Coriandrum sativum. (Application of Plants in Prevention and Treatment of Illnesses). 257–252. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zargari A. fifth ed. vol. 2. Tehran University Publications; 1991. pp. 1–942. (Medicinal Plants). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duke J.A. CRC press; 2002. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pathan A., Kothawade K., Logade M.N. Anxiolytic and analgesic effect of seeds of Coriandrum sativum Linn. Int J Res Pharm Chem. 2011;1:1087–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahendra P., Bisht S. Anti-anxiety activity of Coriandrum sativum assessed using different experimental anxiety models. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:574. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosseinzadeh H., Madanifard M. 2000. Anticonvulsant Effects of Coriandrum sativum L. Seed Extracts in Mice. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iranshahy M., Iranshahi M. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of asafoetida (Ferula assa-foetida oleo-gum-resin)—a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khajeh M., Yamini Y., Bahramifar N., Sefidkon F., Pirmoradei M.R. Comparison of essential oils compositions of Ferula assa-foetida obtained by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and hydrodistillation methods. Food Chem. 2005;91:639–644. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zia-Ul-Haq M., Shahid S.A., Ahmad S., Qayum M., Khan I. Antioxidant potential of various parts of Ferula assafoetida L. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6:3254–3258. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee C.-L., Chiang L.-C., Cheng L.-H. Influenza A (H1N1) antiviral and cytotoxic agents from Ferula assa-foetida. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1568–1572. doi: 10.1021/np900158f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bagheri S.M., Rezvani M.E., Vahidi A.R., Esmaili M. Anticonvulsant effect of Ferula assa-foetida oleo gum resin on chemical and amygdala-kindled rats. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:408. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.139296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khazdair M.R., Boskabady M.H., Kiyanmehr M., Hashemzehi M., Iranshahi M. The inhibitory effects of Ferula assafoetida on muscarinic receptors of Guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiyanmehr M., Boskabady M.H., Khazdair M.R., Hashemzehi M. Possible mechanisms for functional antagonistic effect of Ferula assafoetida on muscarinic receptors in tracheal smooth muscle. Malays J Med Sci. 2016;23:35–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khazdair M.R., Boskabady M.H. The relaxant effect of Ferula assafoetida on smooth muscles and the possible mechanisms. J Herb Pharmacother. 2015;4 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goudah A., Abdo-El-Sooud K., Yousef M.A. Acute and subchronic toxicity assessment model of Ferula assa-foetida gum in rodents. Vet World. 2015;8:584. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.584-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moghadam F.H., Dehghan M., Zarepur E. Oleo gum resin of Ferula assa-foetida L. ameliorates peripheral neuropathy in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zarmouh N.O., Messeha S.S., Elshami F.M., Soliman K.F. Natural products screening for the identification of selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors. Eur J Med Plants. 2016 May;15 doi: 10.9734/EJMP/2016/26453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar P., Singh V.K., Singh D.K. Kinetics of enzyme inhibition by active molluscicidal agents ferulic acid, umbelliferone, eugenol and limonene in the nervous tissue of snail Lymnaea acuminata. Phytother Res. 2009 Feb;23:172–177. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adiga S., Bhat P., Chaturvedi A., Bairy K., Kamath S. Evaluation of the effect of Ferula asafoetida Linn. gum extract on learning and memory in Wistar rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:82. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.91873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azaz A.D., Irtem H.A., Kurkcuoǧlu M., Can Baser K.H. Composition and the in vitro antimicrobial activities of the essential oils of some Thymus species. Z Naturforsch C. 2004;59:75–80. doi: 10.1515/znc-2004-1-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee S.-J., Umano K., Shibamoto T., Lee K.-G. Identification of volatile components in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and thyme leaves (Thymus vulgaris L.) and their antioxidant properties. Food Chem. 2005;91:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dogu-Baykut E., Gunes G., Decker E.A. Impact of shortwave ultraviolet (UV-C) radiation on the antioxidant activity of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) Food Chem. 2014;157:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farina M., Franco J.L., Ribas C.M. Protective effects of Polygala paniculata extract against methylmercury-induced neurotoxicity in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:1503–1508. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.11.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Assiri A.M., Elbanna K., Abulreesh H.H., Ramadan M.F. Bioactive compounds of cold-pressed thyme (Thymus vulgaris) oil with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. J Oleo Sci. 2016;65:629–640. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess16042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Youdim K.A., Deans S.G. Effect of thyme oil and thymol dietary supplementation on the antioxidant status and fatty acid composition of the ageing rat brain. Br J Nutr. 2000 Jan;83:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Komaki A., Hoseini F., Shahidi S., Baharlouei N. Study of the effect of extract of Thymus vulgaris on anxiety in male rats. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016 Jul;6:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grundmann O., Nakajima J.-I., Kamata K., Seo S., Butterweck V. Kaempferol from the leaves of Apocynum venetum possesses anxiolytic activities in the elevated plus maze test in mice. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Melo F.H.C., Venâncio E.T., De Sousa D.P. Anxiolytic-like effect of Carvacrol (5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol) in mice: involvement with GABAergic transmission. Fund Clin Pharmacol. 2010;24:437–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Souto-Maior F.N., de Carvalho F.L., de Morais L.C.S.L., Netto S.M., de Sousa D.P., de Almeida R.N. Anxiolytic-like effects of inhaled linalool oxide in experimental mouse anxiety models. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Nekeety A.A., Mohamed S.R., Hathout A.S., Hassan N.S., Aly S.E., Abdel-Wahhab M.A. Antioxidant properties of Thymus vulgaris oil against aflatoxin-induce oxidative stress in male rats. Toxicon. 2011;57:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Waliwitiya R., Belton P., Nicholson R.A., Lowenberger C.A. Effects of the essential oil constituent thymol and other neuroactive chemicals on flight motor activity and wing beat frequency in the blowfly Phaenicia sericata. Pest Manag Sci. 2010;66:277–289. doi: 10.1002/ps.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deng X.Y., Li H.Y., Chen J.J. Thymol produces an antidepressant-like effect in a chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2015 Sep 15;291:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marin L.D., Sanchez-Borzone M., Garcia D.A. Comparative antioxidant properties of some GABAergic phenols and related compounds, determined for homogeneous and membrane systems. Med Chem. 2011 Jul;7:317–324. doi: 10.2174/157340611796150969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sammi S.R., Trivedi S., Rath S.K. 1-Methyl-4-propan-2-ylbenzene from Thymus vulgaris attenuates cholinergic dysfunction. Mol Neurobiol. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shaiq Ali M., Saleem M., Ali Z., Ahmad V.U. Chemistry of Zataria multiflora (Lamiaceae) Phytochemistry. 2000;12(55):933–936. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bohlmann F., Grenz M., Jakupovic J., King R.M., Robinson H. Four heliangolides and other sesquiterpenes from Brasilia sickii. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sashida Y., Nakata H., Shimomura H., Kagaya M. Sesquiterpene lactones from pyrethrum flowers. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:1219–1222. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rasool N., Khan A.Q., Ahmad V.U., Malik A. A benzoquinone and a coumestan from Psoralea plicata. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:2800–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sharififar F., Moshafi M., Mansouri S., Khodashenas M., Khoshnoodi M. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanol extract of endemic Zataria multiflora Boiss. Food Contr. 2007;18:800–805. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boskabady M.H., Gholami Mhtaj L. Effect of the Zataria multiflora on systemic inflammation of experimental animals model of COPD. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/802189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bazargani-Gilani B., Tajik H., Aliakbarlu J., editors. Physicochemical and Antioxidative Characteristics of Iranian Pomegranate (Punica granatum L. cv. Rabbab-e-Neyriz) Juice and Comparison of its Antioxidative Activity with Zataria multiflora Boiss Essential Oil. Veterinary Research Forum; 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dadashi M., Hashemi A., Eslami G. Evaluation of antibacterial effects of Zataria multiflora Boiss extracts against ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6:336–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shokri H., Asadi F., Bahonar A.R., Khosravi A.R. The role of Zataria multiflora essence (Iranian herb) on innate immunity of animal model. Iran J Immunol. 2006;3:164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hosseinzadeh H., Ramezani M. Salmani G-a. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and acute toxicity effects of Zataria multiflora Boiss extracts in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:379–385. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Majlessi N., Choopani S., Kamalinejad M., Azizi Z. Amelioration of amyloid β-induced cognitive deficits by Zataria multiflora Boiss. Essential oil in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:295–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Araujo C.A.C., Leon L.L. Biological activities of Curcuma longa L. Memorias do Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:723–728. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Akram M., Uddin S., Ahmed A. Curcuma longa and curcumin: a review article. Rom J Biol Plant Biol. 2010;55:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kulkarni S., Akula K.K., Deshpande J. Evaluation of antidepressant-like activity of novel water-soluble curcumin formulations and St. John's wort in behavioral paradigms of despair. Pharmacology. 2012;89:83–90. doi: 10.1159/000335660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang F., Lim G.P., Begum A.N. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid β oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5892–5901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang J., Song S., Li J., Liang T. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin on hippocampal injury in 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson's disease rat. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khazdair M.R., Mohebbati R., Karimi S., Abbasnezhad A., Haghshenas M. The protective effects of Curcuma longa extract on oxidative stress markers in the liver induced by Adriamycin in rat. Physiol Psychol. 2016;20:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mohebbati R., Shafei M.N., Soukhtanloo M. Adriamycin-induced oxidative stress is prevented by mixed hydro-alcoholic extract of Nigella sativa and Curcuma longa in rat kidney. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2016;6:86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khatri D.K., Juvekar A.R. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin as evinced by abrogation of rotenone-induced motor deficits, oxidative and mitochondrial dysfunctions in mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2016;150:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu L., Zhang W., Wang L. Curcumin prevents cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury via increase of mitochondrial biogenesis. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:1322–1331. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tu X-k, Yang W-z, Chen J-p. Curcumin inhibits TLR2/4-NF-κB signaling pathway and attenuates brain damage in permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Inflammation. 2014;37:1544–1551. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang C., Zhang X., Fan H., Liu Y. Curcumin upregulates transcription factor Nrf2, HO-1 expression and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 2009;1282:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Y., Li J., Li S. Curcumin attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in the hippocampus by suppression of ER stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a manner dependent on AMPK. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li L., Li H., Li M. Curcumin protects against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:14985–14991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li X., Zhao L., Yue L. Evidence for the protective effects of curcumin against oxyhemoglobin-induced injury in rat cortical neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2016;120:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang J., Du X.-X., Jiang H., Xie J.-X. Curcumin attenuates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cytotoxicity by anti-oxidation and nuclear factor-kappaB modulation in MES23. 5 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jaisin Y., Thampithak A., Meesarapee B. Curcumin I protects the dopaminergic cell line SH-SY5Y from 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neurotoxicity through attenuation of p53-mediated apoptosis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;489:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Agrawal S.S., Gullaiya S., Dubey V. Neurodegenerative shielding by curcumin and its derivatives on brain lesions induced by 6-OHDA model of Parkinson's disease in albino wistar rats. Cardiovasc Psychiatr Neurol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/942981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Harish G., Venkateshappa C., Mythri R.B. Bioconjugates of curcumin display improved protection against glutathione depletion mediated oxidative stress in a dopaminergic neuronal cell line: implications for Parkinson's disease. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:2631–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tripanichkul W., Jaroensuppaperch E. Ameliorating effects of curcumin on 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic denervation, glial response, and SOD1 reduction in the striatum of hemiparkinsonian mice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:1360–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tegenge M.A., Rajbhandari L., Shrestha S., Mithal A., Hosmane S., Venkatesan A. Curcumin protects axons from degeneration in the setting of local neuroinflammation. Exp Neurol. 2014;253:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen J., Tang X., Zhi J. Curcumin protects PC12 cells against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced apoptosis by bcl-2-mitochondria-ROS-iNOS pathway. Apoptosis. 2006;11:943–953. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6715-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ojha R.P., Rastogi M., Devi B.P., Agrawal A., Dubey G. Neuroprotective effect of curcuminoids against inflammation-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yang S., Zhang D., Yang Z. Curcumin protects dopaminergic neuron against LPS induced neurotoxicity in primary rat neuron/glia culture. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:2044–2053. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9675-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kianmehr M., Rezaei A., Hosseini M. Immunomodulatory effect of characterized extract of Zataria multiflora on Th1, Th2 and Th17 in normal and Th2 polarization state. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;99:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Khazdair M.R., Ghorani V., Alavinezhad A., Boskabady M.H. Pharmacological effects of Zataria multiflora Boiss L. and its constituents, focus on their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects. Fund Clin Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/fcp.12331. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fcp.12331/full Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Akhondzadeh S., Fallah-Pour H., Afkham K., Jamshidi A.-H., Khalighi-Cigaroudi F. Comparison of Crocus sativus L. and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a pilot double-blind randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Akhondzadeh S., Tahmacebi - Pour N., Noorbala A.A. Crocus sativus L. in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double - blind, randomized and placebo - controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2005;19:148–151. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Moshiri E., Akhondzadeh Basti A., Noorbala A.A., Jamshidi A.H., Abbasi S.H., Akhondzadeh S. Crocus sativus L. (petal) in the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:607–611. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Moosavi S.M., Ahmadi M., Amini M., Vazirzadeh B., Sari I. The effects of 40 and 80 mg hydro-alcoholic extract of Crocus sativus in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci (JMUMS) 2014;24 [Google Scholar]

- 123.Boskabady M.H., Javan H., Sajady M., Rakhshandeh H. The possible prophylactic effect of Nigella sativa seed extract in asthmatic patients. Fund Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21:559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Boskabady M.H., Farhadi J. The possible prophylactic effect of Nigella sativa seed aqueous extract on respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function tests on chemical war victims: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Alternative Compl Med. 2008;14:1137–1144. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Boskabady M.H., Mohsenpoor N., Takaloo L. Antiasthmatic effect of Nigella sativa in airways of asthmatic patients. Phytomed Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2010;17:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kalus U., Pruss A., Bystron J. Effect of Nigella sativa (black seed) on subjective feeling in patients with allergic diseases. Phytother Res. 2003;17:1209–1214. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Akbar W., Miana Ga, Ahmad Si, Munir Ka. Clinical investigation of hypoglycemic effect of Coriandrum sativum in Type-2 (Niddm) diabetic patients. Pakistan J Psychol. 2006;23:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Prucksunand C., Indrasukhsri B., Leethochawalit M., Hungspreugs K. Phase II clinical trial on effect of the long turmeric (Curcuma longa Linn) on healing of peptic ulcer. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Publ Health. 2001;32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]