Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. Diagnosis and treatment may drastically affect quality of life, causing symptoms such as sleep disorders, depression and anxiety. Mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) is a programme that aims to reduce stress by developing mindfulness, meaning a non‐judgmental, accepting moment‐by‐moment awareness. MBSR seems to benefit patients with mood disorders and chronic pain, and it may also benefit women with breast cancer.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) in women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Search methods

In April 2018, we conducted a comprehensive electronic search for studies of MBSR in women with breast cancer, in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, and two trial registries (World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov). We also handsearched relevant conference proceedings.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) comparing MBSR versus no intervention in women with breast cancer.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Using a standardised data form, the review authors extracted data in duplicate on methodological quality, participants, interventions and outcomes of interest (quality of life, fatigue, depression, anxiety, quality of sleep, overall survival and adverse events). For outcomes assessed with the same instrument, we used the mean difference (MD) as a summary statistic for meta‐analysis; for those assessed with different instruments, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD). The effect of MBSR was assessed in the short term (end of intervention), medium term (up to 6 months after intervention) and long term (up to 24 months after intervention).

Main results

Fourteen RCTs fulfilled our inclusion criteria, with most studies reporting that they included women with early breast cancer. Ten RCTs involving 1571 participants were eligible for meta‐analysis, while four studies involving 185 participants did not report usable results. Queries to the authors of these four studies were unsuccessful. All studies were at high risk of performance and detection bias since participants could not be blinded, and only 3 of 14 studies were at low risk of selection bias. Eight of 10 studies included in the meta‐analysis recruited participants with early breast cancer (the remaining 2 trials did not restrict inclusion to a certain cancer type). Most trials considered only women who had completed cancer treatment.

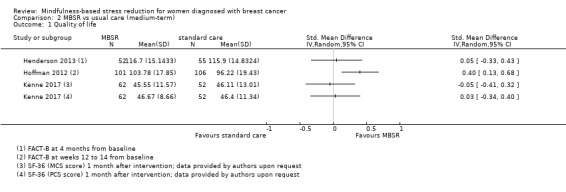

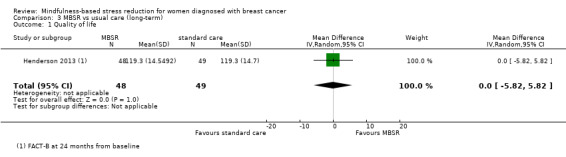

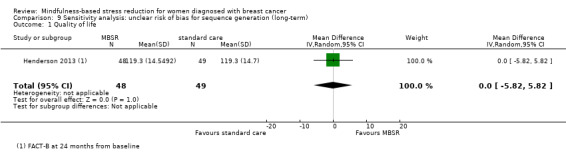

MBSR may improve quality of life slightly at the end of the intervention (based on low‐certainty evidence from three studies with a total of 339 participants) but may result in little to no difference up to 6 months (based on low‐certainty evidence from three studies involving 428 participants). Long‐term data on quality of life (up to two years after completing MBSR) were available for one study in 97 participants (MD 0.00 on questionnaire FACT‐B, 95% CI −5.82 to 5.82; low‐certainty evidence).

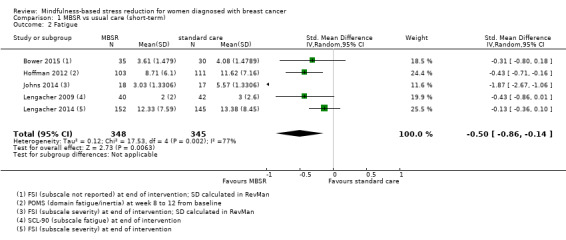

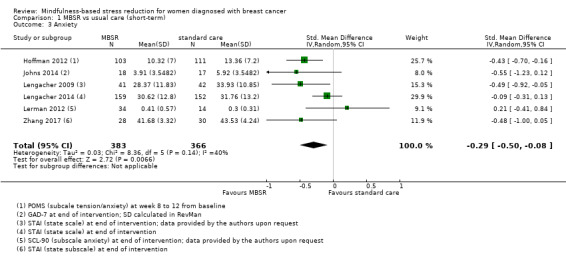

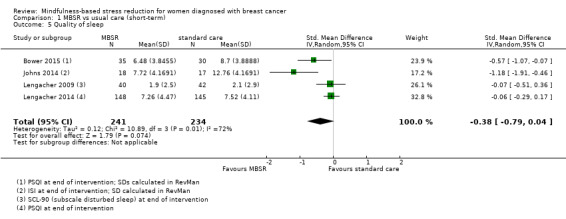

In the short term, MBSR probably reduces fatigue (SMD −0.50, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.14; moderate‐certainty evidence; 5 studies; 693 participants). It also probably slightly reduces anxiety (SMD −0.29, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.08; moderate‐certainty evidence; 6 studies; 749 participants), and it reduces depression (SMD −0.54, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.22; high‐certainty evidence; 6 studies; 745 participants). It probably slightly improves quality of sleep (SMD −0.38, 95% CI −0.79 to 0.04; moderate‐certainty evidence; 4 studies; 475 participants). However, these confidence intervals (except for short‐term depression) are compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference.

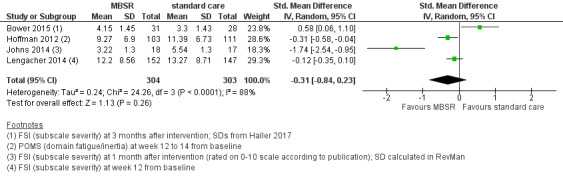

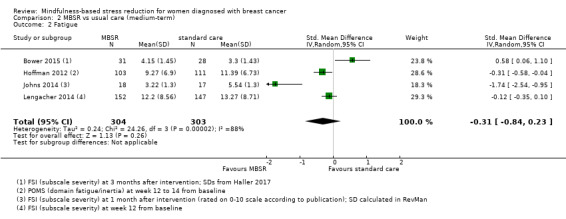

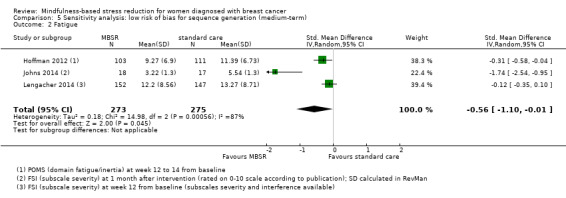

In the medium term, MBSR probably results in little to no difference in medium‐term fatigue (SMD −0.31, 95% CI −0.84 to 0.23; moderate‐certainty evidence; 4 studies; 607 participants). The intervention probably slightly reduces anxiety (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.07; moderate‐certainty evidence; 7 studies; 1094 participants), depression (SMD −0.32, 95% CI −0.58 to −0.06; moderate‐certainty evidence; 7 studies; 1097 participants) and slightly improves quality of sleep (SMD −0.27, 95% CI −0.63 to 0.08; moderate‐certainty evidence; 4 studies; 654 participants). However, these confidence intervals are compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference.

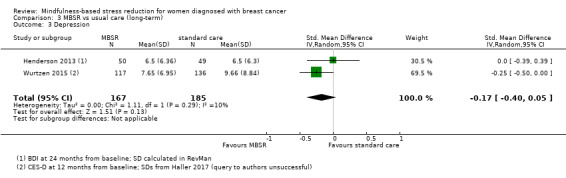

In the long term, moderate‐certainty evidence shows that MBSR probably results in little to no difference in anxiety (SMD −0.09, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.16; 2 studies; 360 participants) or depression (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.05; 2 studies; 352 participants). No long‐term data were available for fatigue or quality of sleep.

No study reported data on survival or adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

MBSR may improve quality of life slightly at the end of the intervention but may result in little to no difference later on. MBSR probably slightly reduces anxiety, depression and slightly improves quality of sleep at both the end of the intervention and up to six months later. A beneficial effect on fatigue was apparent at the end of the intervention but not up to six months later. Up to two years after the intervention, MBSR probably results in little to no difference in anxiety and depression; there were no data available for fatigue or quality of sleep.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Mindfulness; Anxiety; Anxiety/psychology; Breast Neoplasms; Breast Neoplasms/psychology; Depression; Depression/psychology; Fatigue; Fatigue/psychology; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sleep Wake Disorders; Sleep Wake Disorders/psychology; Stress, Psychological; Stress, Psychological/therapy; Time Factors

Plain language summary

Mindfulness‐based stress reduction for women with breast cancer

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to determine whether mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) benefits women with breast cancer. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found 14 studies, most of which included women with early breast cancer.

Key messages

The women's health was monitored at different time points: straight after completing MBSR, up to six months after completing MBSR and up to two years after MBSR.

MBSR may slightly improve quality of life at the end of the intervention but result in little to no difference in women's overall well‐being (quality of life) later on. MBSR probably reduces anxiety and depression, and probably improves quality of sleep at both the end of MBSR and up to six months later. Women reported being less tired just after completing MBSR but not up to 6 months later. There was no information available on survival or adverse events.

What was studied in the review?

Women with breast cancer mostly experience diagnosis and treatment as a severe and life‐threatening situation that may drastically affect their quality of life, causing symptoms such as sleep disorders, depression, anxiety and fatigue. Previous research shows that MBSR seems to benefit patients with lung cancer, mood disorders or chronic pain, so it may also benefit women with breast cancer.

MBSR is an eight‐week programme that aims to reduce stress by developing mindfulness, meaning that one practises moment‐by‐moment awareness in a non‐judgmental and accepting way. We wanted to study whether MBSR benefits women with breast cancer with regard to quality of life, anxiety, depression, fatigue and quality of sleep. We also looked at its influence on survival and adverse events related to cancer therapy.

We searched for studies that compared MBSR versus no treatment, and we studied the results at the end of the intervention, up to six months after the intervention and up to 2 years after the intervention.

What are the main results of this review?

The review authors found 14 relevant studies including mostly women with early breast cancer. Most studies considered women who had completed cancer treatment. We could analyse only the results of 10 studies including 1571 participants; the other four studies did not report (usable) results; queries to the authors were unsuccessful. Of the 10 studies analysed, 6 were from the USA, 3 from Europe, and 1 from China.

The review shows MBSR may improve quality of life slightly at the end of the intervention but may result in little to no difference up to six months or up to two years after completing MBSR. At the end of the intervention, MBSR reduces depression, probably slightly reduces fatigue and anxiety, and probably improves quality of sleep. Up to six months later, MBSR probably slightly reduces anxiety and slightly improves quality of sleep, and it slightly reduces depression. There was a benefit on fatigue at the end of the intervention but not up to six months later. However, for all beneficial effects except for short‐term depression, the results we found could be due to chance. Up to two years after the intervention, MBSR probably results in little to no difference in anxiety, depression and quality of life. No long‐term data were available for fatigue or quality of sleep. No study reported data on survival or adverse events.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The authors searched for studies published up to April 2018.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. MBSR versus usual care for women diagnosed with breast cancer.

| MBSR versus usual care for women diagnosed with breast cancer | |||||

| Patient or population: women diagnosed with breast cancer Setting: medium term Intervention: MBSR Comparison: usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with MBSR | ||||

| Quality of life | — | — | 428 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b,c | Quality of life was assessed in 6 additional studies (including 542 participants). Due to these concerns about missing data, we did not perform a meta‐analysis but applied vote counting (see McKenzie 2018): 1 study suggests a beneficial effect of MBSR, while the 2 other studies suggest neither benefit nor harm. |

| Overall survival | Not reported | ||||

| Fatigue assessed with 2 different questionnaires Higher scores represent more fatigue Follow‐up: range 3‐5 months | The fatigue score in the intervention group was on average 0.31 SDs lower (0.84 lower to 0.23 higher) than in the usual care groups | 607 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,d | As a rule of thumb, an SMD of 0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Anxiety assessed with 6 different questionnaires Higher scores represent more anxiety Follow‐up: range 3‐6 months | The anxiety score in the intervention group was on average 0.28 SDs lower (0.49 lower to 0.07 lower) than in the usual care groups | 1094 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,e | As a rule of thumb, an SMD of 0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Depression assessed with 5 different questionnaires Higher scores represent more depression Follow‐up: range 3‐6 months | The depression score in the intervention group was on average 0.32 SDs lower (0.58 lower to 0.06 lower) than in the usual care groups | 1097 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,e | As a rule of thumb, an SMD of 0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Quality of sleep assessed with 3 different questionnaires Higher scores represent worse quality of sleep Follow‐up: range 3‐6 months | The quality of sleep score in the intervention group was on average 0.27 SDs lower (0.63 lower to 0.08 higher) than in the usual care groups | 654 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec,e | As a rule of thumb, an SMD of 0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Adverse events | Not reported | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparator group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MBSR: mindfulness‐based stress reduction; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aData on quality of life measured in six additional studies but no results available for meta‐analysis. b Studies were unblinded. cSample size < 400 (less then the minimum optimal information size (OIS) recommended for continuous outcomes). d95% CI includes both an appreciable benefit and an appreciable harm. e95% CI includes both an effect not relevant to participants and an appreciable benefit.

Background

Description of the condition

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. There are 1.6 million new cases per year worldwide (Ferlay 2013). Incidence rates vary, with the lowest rates in less developed regions and nearly four‐fold higher rates in more developed regions, from 27 per 100,000 in Middle Africa and Eastern Asia to 96 per 100,000 in Western Europe (Ferlay 2013). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), worldwide more than 508,000 women died from breast cancer in 2011 (WHO 2014). In the USA, the American Cancer Society 2014 estimated there would be 232,670 new diagnoses and about 40,000 breast cancer deaths in 2014. The five‐year relative survival for women diagnosed with breast cancer in the USA in 2009 was 89.5% (Howlader 2013).

Breast cancer treatment depends on the tumour type and staging, and it consists of local therapy such as surgery and radiation, or of systemic therapy such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, or a combination of these treatments. Breast cancer staging (0 to IV) is classified into the following TNM categories: primary tumour, Tx to T4; with or without lymph nodes, Nx to N3b; with or without metastasis, Mx to M1. Stage I is the least advanced, and stage IV the most advanced, whereas 0 stands for non‐invasive cancer (National Cancer Institute 2014).

Most women experience breast cancer diagnosis and treatment as a severe and life‐threatening situation, and it can drastically affect their quality of life (QoL), causing psychological distress and symptoms such as sleep disorders, depression and anxiety (Faller 2013). German practice guidelines for breast cancer highly recommend providing psychosocial and psycho‐oncological supportive care, such as relaxation training and psycho‐educational interventions in addition to standard therapy and after treatment (GGPO 2014). There is evidence from several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showing an improvement in QoL and quality of sleep following the use of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) practices (Andersen 2013; Hoffman 2012). The most common coexisting symptom of all cancers, including breast cancer, is fatigue due to anaemia, cancer treatments or depression (Matthews 2014; Mitchell 2011; National Cancer Comprehensive Network 2014; Tan 2014).

Description of the intervention

MBSR was developed in the USA in the 1970s by Prof Jon Kabat‐Zinn (Kabat‐Zinn 1990). MBSR is a programme that reduces stress by developing mindfulness, meaning a non‐judgmental, accepting moment‐by‐moment awareness. The intervention is free of any cultural, religious and ideological factors, but it is associated with the Buddhist origins of mindfulness. The MBSR programme is usually performed in groups of up to 20 participants and consists of eight weekly sessions (two‐hour classes) and a one‐day retreat (six hours' mindful exercises) between sessions six and seven. Additionally, daily home assignments for about 45 minutes using a mindfulness practice CD are completed throughout the programme. There are three main formal practical exercises: body scan (mindful body perception), gentle yoga exercises and traditional sitting meditation. Furthermore, there is a focus on informal exercises (i.e. mindfulness in the daily routine, in dealing with stress, pain, depression, anxiety or disease). People learn to adapt an alternative lifestyle by repeatedly performing the formal and informal exercises. After completion of the programme, participants are asked to continue with the daily exercise by integrating it into their everyday routine.

Since Kabat‐Zinn founded the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine in 1995 and the Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction Clinic in 1979 at the University of Massachusetts (USA), MBSR has been successfully used in many hospitals and widely practised in complementary medicine, mainly in the field of cancer diseases (Ludwig 2008).

How the intervention might work

Kabat‐Zinn's research goals are to integrate mindfulness into medicine (Kabat‐Zinn 1990). He mainly focuses on mind‐body interactions for healing, clinical applications of mindfulness meditation training for people with chronic pain or stress‐related disorders, or both. He acknowledged the importance of the effects of MBSR on the brain and the immune system, and observed how the brain processes emotions, particularly under stress. The effect of this programme is scientifically based on findings in the field of psychology and stress research and has been successfully applied in the healthcare sector and in educational and social facilities worldwide (Hölzel 2011; Meibert 2011). According to Hölzel 2011, there is a relationship between MBSR and changes in grey matter concentration in brain regions that regulate emotion, self‐referential processing, learning and memory processes. Several studies indicate the beneficial relationship between stress reduction and QoL associated with simultaneous improvement in the immune system following MBSR practice (Carlson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Lengacher 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

There is an increasing recognition of MBSR interventions as a way to decrease distress and increase psychological health, but more systematic reviews of RCTs are needed to verify these results. This systematic review summarises and meta‐analyses the evidence on MBSR in women with breast cancer. We assessed the quality of the evidence in terms of QoL, overall survival (OS), fatigue, depression and quality of sleep. Improvements in early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer have prolonged survival, but this might also lead to specific psychological issues and problems for long‐term breast cancer survivors (Faller 2013; Ploos 2013). Consequently, there has to be more emphasis on the short‐ and long‐term impact on patients' QoL.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) in women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered RCTs only.

Types of participants

We included all women (aged 18 years or over) with a confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer. We considered all types of tumours and all stages according to the current TNM categories (primary tumour, Tx to T4; with or without lymph nodes, Nx to N3b; with or without metastasis, Mx to M1), including women with a diagnosis of early breast cancer and women with a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer.

Types of interventions

The experimental intervention included MBSR plus anticancer therapy (MBSR was considered relevant both during and after active therapy). Some deviations to the Kabat‐Zinn MBSR programme were allowed: not all components described in the Background section needed to be implemented. Studies were eligible when: their intervention did not include a one‐day retreat, the participants were offered at least six of the eight foreseen weekly group sessions, and there were fewer requirements for home assignment than in the original programme designed by Kabat‐Zinn.

We excluded further types of mindfulness‐based therapies such as mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, dialectical behaviour therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindful exercise and mindfulness‐based art therapy.

The control intervention was usual care (anticancer therapy alone).

Participants in both groups must have been scheduled to receive identical anticancer and supportive therapy.

If we identified three‐arm studies, we included the MBSR and the usual supportive care‐arm only, according to the inclusion criteria.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Quality of life (QoL) measured with reliable and validated instruments such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General (FACT‐G; King 2014), the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36; Ware 1992), or disease‐specific questionnaires such as the English European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire‐Core 30 (QLQ‐C30; Lundy 2014).

Secondary outcomes

Overall survival (OS) defined as the time interval from randomisation until death from any cause or last follow‐up; the hazard ratio (HR) was considered to be the most appropriate measure of treatment effect

Fatigue, if measured with reliable and validated instruments such as the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI; Mendoza 1999)

Anxiety, if measured with reliable and validated instruments such as the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Julian 2011)

Depression, if measured with reliable and validated instruments such as the Centers for Epidemiological Studies ‐ Depression (CES‐D; Hann 1999)

Quality of sleep, if measured with reliable and validated instruments such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse 1989)

Adverse events, classified as Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade 3 or higher (CTEP 2014)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We adapted the search strategies as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011). We searched the following databases.

The Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's (CBCG's) Specialised Register (18 February 2015). Details of the search strategies used by the Group for identifying studies and the procedure used to code references are outlined in the Group's module (www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/BREASTCA/frame.html). We extracted trials with the key words 'breast neoplasms', 'breast near cancer', 'breast near neoplasm', 'breast near carcinoma', 'breast near tumour', 'mind‐body therapies', 'body‐mind', 'mind‐body near', 'mindfulness based stress reduction', 'mindfulness based', 'mbsr', 'meditation', 'relaxation therapy' and 'relaxation* near', and we considered them for inclusion in the review.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library (searched 10 April 2018). See Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

MEDLINE via OvidSP (2008 to 10 April 2018). For RCTs, we limited the search to results from 2008 onwards to coincide with the years where references had not been uploaded into the CBCG's Specialised Register. See Appendix 3 and Appendix 4.

Embase (via embase.com; 2008 to 18 February 2015). For RCTs, we limited the search to results from 2008 onwards to coincide with the years where references had not been uploaded into the CBCG's Specialised Register. See Appendix 5.

The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials in 10 April 2018 (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx). See Appendix 6.

Clinicaltrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/) in 10 April 2018. See Appendix 7.

Searching other resources

We handsearched references of all identified trials, relevant review articles and current treatment guidelines for further literature. We did not contact experts in the field to identify unpublished trials.

We searched the proceedings of relevant conferences of the following societies for the years not included in CENTRAL (from January 2005 to 2017).

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO).

San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS).

European Congress for Integrative Medicine (ECIM).

International Research Congress on Integrative Medicine and Health (IRCIMH).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LS, NS) independently screened the abstracts yielded from the search strategies to assess eligibility for this review. In the case of a disagreement, we obtained the full‐text publication. As we always reached a consensus, we did not need to ask a third review author (MR) to arbitrate (Higgins 2011a).

We documented the study selection process in a flow chart as recommended in the PRISMA statement, showing the total numbers of retrieved references and the number of included and excluded studies (Moher 2009).

We included both full‐text and abstract publications if sufficient information was available on study design, characteristics of participants, interventions and outcomes.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LS, NS) extracted data as specified in Cochrane guidelines. We contacted authors of particular studies for auxiliary information (Higgins 2011b). We used a standardised data extraction form containing the following items.

General information: author, title, source, publication date, country, language, duplicate publications.

Risk of bias: allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel, outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias.

Study characteristics: trial design, aims, setting and dates, source of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, comparability of groups, subgroup analysis, statistical methods, power calculations, treatment cross‐overs, compliance with assigned treatment, length of follow‐up, time point of randomisation.

Participant characteristics: underlying disease, stage of disease, histological subtype, additional diagnoses, age, sex, ethnicity, number of participants recruited/allocated/evaluated, participants lost to follow‐up; type of treatment (multi‐agent chemotherapy (intensity of regimen, number of cycles)), additional radiotherapy.

Interventions: type, duration and intensity of meditation intervention, usual care, duration of follow‐up.

Outcomes: QoL, OS, fatigue, anxiety, depression, quality of sleep, adverse events.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LS, NS) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c).

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other sources of bias.

We made a judgment for every criterion, using one of three categories.

'Low risk': if the study adequately fulfils the criterion (i.e. the study is at a low risk of bias for the given criterion).

'High risk': if the study does not fulfil the criterion (i.e. the study is at high risk of bias for the given criterion).

'Unclear': if the study report does not provide sufficient information to allow for a judgment of 'Yes' or 'No' or if the risk of bias is unknown for one of the criteria listed above.

Measures of treatment effect

For time‐to‐event outcomes (e.g. OS) we planned to consider HRs if they were available from published data, otherwise we planned to extract HRs according to Parmar 1998 and Tierney 2007. We planned to extract log HRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), and, if unavailable, we planned to extract P values and the number of events and calculate the log HR. If neither were reported, we planned to analyse survival curves and extract the number of events and censored participants from these curves. However, no data on overall survival were reported.

For binary outcomes (such as adverse events), we planned to calculate risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs for each trial. However, no data on adverse events were reported.

If possible, we analysed data from ordinal scales as continuous data (e.g. QoL, fatigue, depression, quality of sleep, anxiety) using mean differences (MD) according to Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). If different scales were used to report questionnaire data, we used standardised mean differences (SMDs) to determine effect sizes. We considered an SMD of 0.2 as a small effect, 0.5 as a moderate effect, and 0.8 as a large effect.

We planned to evaluate baseline and end‐of‐treatment data, if available, at one month, two months, three months, six months and one year after the end of treatment. Since most studies presented end‐of‐treatment instead of change data, we analysed the end‐of‐treatment data (based on the assumption that baseline data are comparable for randomised treatment groups). Change data were presented in an additional sensitivity analysis, if available. We decided post hoc to restrict the analyses to three separate time points.

Short‐term analysis (end of intervention).

Medium‐term analysis (up to 6 months after baseline).

Long‐term analysis (more than 12 months after baseline).

Studies were eligible for pooling in each separate analysis, i.e. up to three time points per study were considered. For each study, the latest measure available for the respective analysis was chosen.

We did not pre‐specify whether we preferred to use adjusted or unadjusted outcome data in our data extraction and analyses. If both unadjusted and adjusted data were available, we considered the unadjusted data to avoid including effects based on different adjustment approaches, thus ensuring a uniform approach across studies. This (post hoc) decision was based on the assumption that randomisation makes for balanced groups.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not encounter any unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original investigators to request missing data. If our queries were unsuccessful and standard deviations (SDs) were missing, we calculated them from standard errors, confidence intervals and t values. In some cases, we were able to extract the respective SD from another systematic review (Haller 2017). We addressed the potential impact of missing data on the findings of the review in both the Results and Discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated heterogeneity of treatment effects using a Chi2 test with a significance level of P < 0.1. We used the I2 statistic as an approximate guide to interpret the magnitude of heterogeneity (I2 greater than 30%: moderate heterogeneity, I2 greater than 75%: considerable heterogeneity; Deeks 2011). Due to a lack of data, we were unable to explore potential causes of heterogeneity by subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In meta‐analyses with at least 10 trials, we planned to explore potential publication bias by generating a funnel plot and to statistically test it via linear regression (Sterne 2011). We would have considered a P value of less than 0.1 as being significant for this test. However, we were unable to explore potential publication bias since we did not include at least 10 trials in any meta‐analysis. For future updates, we will be aware that funnel plot asymmetry has limitations according to Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Sterne 2011). We considered that study reports may selectively present results; moreover, duplicate publication of results can be difficult to identify, and the availability of study information may be subject to time‐lag bias.

Data synthesis

We performed analyses according to Cochrane recommendations and used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) for analysis (Deeks 2011; RevMan 2014). Since the studies included were clinically heterogeneous, and the intervention was implemented differently in each study, we decided post hoc to use the random‐effects model for meta‐analysis. We used the fixed‐effect model envisaged in the protocol in a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome (quality of life) only. We created a 'Summary of findings' table on absolute risks in each group with the help of GRADE (Schuenemann 2011), summarising the evidence for QoL, OS (no data available), fatigue, anxiety, depression, quality of sleep and adverse events (no data available). We decided to present the medium‐term data in this 'Summary of findings' table.

During the review, we also decided to apply vote counting to describe the available results in case we were unable to undertake a meta‐analysis due to concerns about missing data (McKenzie 2018). For vote counting, we judged an effect as showing benefit if the standardised effect size suggested a beneficial effect and the confidence interval was not compatible with a harmful effect. We judged an effect as showing harm if the standardised effect size suggested a harmful effect and the confidence interval was not compatible with a beneficial effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses using the following characteristics.

Age (under 40 years; 40 years and over; under 60 years; 60 years and over).

Stages (early breast cancer versus metastatic breast cancer).

Type of breast cancer.

MBSR during or after active therapy.

Concomitant therapies (chemotherapy, radiotherapy).

However, due to the paucity of data and an unclear subgroup allocation (see Table 2), we were unable to conduct any of the planned subgroup analyses.

1. Subgroup allocation of studies.

| Subgroup | Bower 2015 | Henderson 2013 | Hoffman 2012 | Johns 2014 | Kenne 2017 | Lengacher 2009 | Lengacher 2014 | Lerman 2012 | Wurtzen 2015 | Zhang 2017 |

| Mean age | ||||||||||

| < 40 years | ||||||||||

| > 40 years | x | x | x | x | x | xa | x | x | x | x |

| < 60 years | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| > 60 years | ||||||||||

| Stage | ||||||||||

| Early BC | x | x | x | xb | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Metastatic BC | ||||||||||

| Unclear | x | |||||||||

| Type of BC | ||||||||||

| ER‐positive | x | |||||||||

| ER‐negative | ||||||||||

| Unclear/less than 80% in either category | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| MBSR during or after activec therapy | ||||||||||

| During active therapy | ||||||||||

| After active therapy | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Unclear/less than 80% in either category | x | xd | x | x | ||||||

| Concomitant therapies | ||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||||

| Neither | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Less than 80% in each category | x | xd | x | x | ||||||

| BC: breast cancer; ER: oestrogen receptor;MBSR: mindfulness‐based stress reduction; UC: usual care. | ||||||||||

aNo data on mean age; allocation to subgroup derived from percentages for age categories. bThe stages for breast cancer only are not reported; however, even the maximum participants (n = 2) with stage IV still results in less than 20%. cActive therapy was defined as active anticancer therapy like radiotherapy and chemotherapy (not endocrine therapy). d"Potential participants were excluded if they had not completed their cancer treatments ... Those who were on maintenance chemotherapy, were accepted if their treatment or disease was not expected to limit participation."

Sensitivity analysis

We considered performing sensitivity analyses using the following characteristics.

Sequence generation (low versus high risk of bias).

Fixed‐effect modelling.

Estimations from imputation of missing data.

However, we were unable to conduct the first two sensitivity analyses as planned: we rated no studies as being at high risk of bias with regard to sequence generation and therefore compared studies at low risk with those at unclear risk.

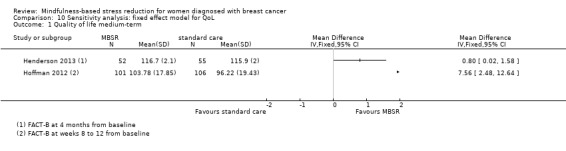

The sensitivity analysis for fixed‐effect model was conducted for the primary outcome (quality of life) only, since we decided during the review to use the random‐effects model for meta‐analysis (see Differences between protocol and review).

In an additional post hoc sensitivity analysis, we checked whether the trials included only data with less than 30% attrition and less than 15 percentage points' difference in missing participants between groups.

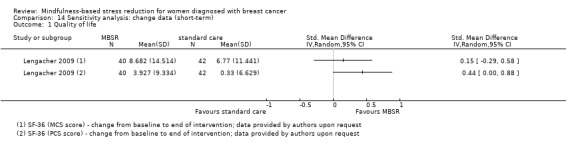

If studies presented change data in addition to or instead of end‐of‐treatment data, we presented the change values in a further post hoc sensitivity analysis. As suggested in Higgins 2018, we calculated change SDs from P values but did not impute them.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

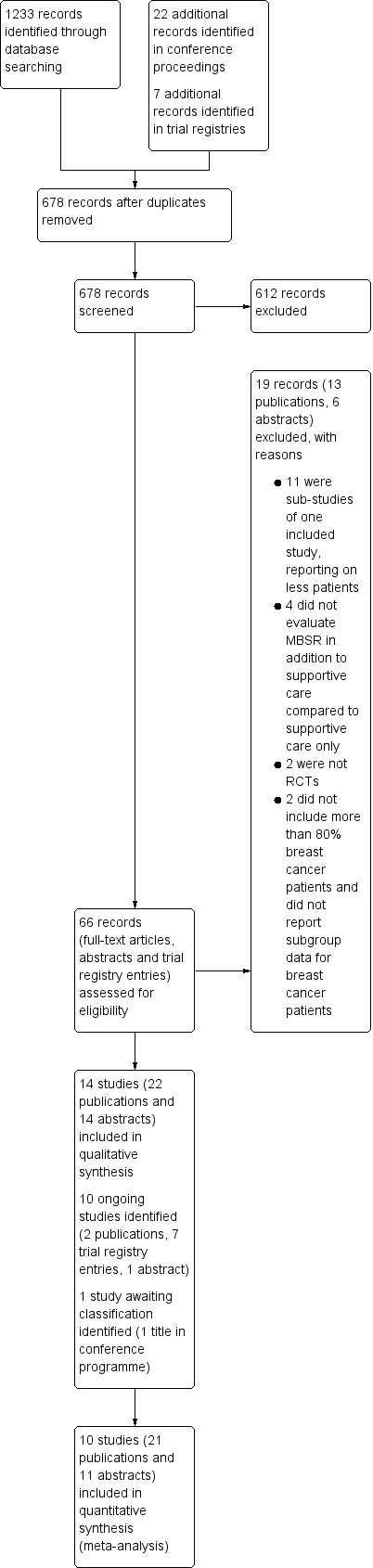

Our searches yielded a total of 1233 potentially relevant citations from the electronic searches, and 22 conference proceedings and 7 registered trials. After deduplication, we screened titles and abstracts of 678 records and the full text (or abstract or trial registry entry) of 66 records. Of these, 36 references for 14 trials (presented as 22 full‐text publications and 14 abstracts) were eligible for inclusion in this review. We excluded 19 records. We classified one record as a study awaiting classification, since neither a publication nor an abstract was available (Choi 2012). The other 10 records reported ongoing trials (1810 participants). All but two foresee trial completion within two years of the time of writing; the two exceptions did not report a completion date.

The PRISMA flow diagram displays the screening process (Figure 1; Moher 2009).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Fourteen trials published in 36 publications fulfilled our inclusion criteria. The meta‐analysis included 10 studies in 1571 participants (Bower 2015; Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Lerman 2012;Wurtzen 2015; Zhang 2017), while the results of four studies were not amenable to quantitative analysis (Johnson 2015; Koumarianou 2014; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015). Attempts to contact their authors were unsuccessful, so the meta‐analyses do not include data from 185 participants. These four studies collected data on quality of life, and one study each additionally measured depression, anxiety and sleep (see Characteristics of included studies).

Of the studies included in the meta‐analysis, six took place in the USA and one each in China, Denmark, Sweden and the UK. All studies took place between 2008 and 2014, except for three that did not report the study period. The number of included participants ranged from 35 in Johns 2014 to 336 in Wurtzen 2015. Each study stated the funding source (mostly foundations and independent funders, like the National Institute of Health; see Characteristics of included studies). Further information on these studies appears in the Characteristics of included studies section, and detailed information on the study populations can be found in Table 3.

2. Characteristics of included participants.

| Study | N randomised | Stage | Age in years (mean ± SD) | Time since diagnosis (mean ± SD) | % receiving concomitant therapy | % with at least some college education | Other information | |

| Bower 2015 | MBSR | 39 | Stage I to III | 46 (28 to 60)a | 4.0 ± 2.4 years | Nob | 87%c | Currently on ET (% of pts): MBSR: 62% UC: 66% |

| UC | 32 | 48 (31 to 60)a | 4.1 ± 2.3 years | 78%c | ||||

| Henderson 2013 | MBSR | 53d | I (55%c) II (45%c) | 49.8 ± 8.4e | 0‐6 months: 14 pts 7‐12 months: 16 pts > 12 months: 21 pts |

CT (% of ptsc) before study: 34% during study: 13% | 83%c | — |

| UC | 58d | I (52%c) II (48%c) | 0‐6 months: 20 pts 7‐12 months: 13 pts > 12 months: 24 pts |

CT (% of ptsc) Before study: 36% During study: 12% | 74%c | |||

| Hoffman 2012 | MBSR | 114 | 0 (10%c) I (30%c) II (41%c) III (19%c) | 49.0f | 17.44 ± 13 months | Nob | 74%g | — |

| UC | 115 | 0 (5%c) I (39%c) II (41%c) III (15%c) | 50.1f | 18.98 ± 15 months | 78%g | |||

| Johns 2014 | MBSR | 18 | Cancer (83% BC) I (28%c) II (28%c) III (22%c) IV (11%c) | 59 ± 9 | — | Nob | 67% | Recent mental health treatment: 5% |

| UC | 17 | Cancer (83% BC) I (41%c) II (41%c) III (12%c) IV (6%c) | 56 ± 9 | 77% | Recent mental health treatment: 41% | |||

| Johnson 2015 | No information available | |||||||

| Kenne 2017 | MBSR | 66 | Early stage BC | 57.2f | — | Nob | 69%c,h | — |

| UC | 51 | 77%c,h | ||||||

| Koumarianou 2014 | No information available | |||||||

| Lengacher 2009 | MBSR | 41 | 0 (12%) I (63%) II (17%) III (7%) | < 55: 44% 55‐64: 22% > 65: 34% | — | Nob | 88%c | Antidepressants: 22% Anxiolytics: 17% |

| UC | 34 | 0 (21%) I (44%) II (28%) III (7%) | < 55: 35% 55‐64: 44% > 65: 21% | 79%c | Antidepressants: 28% Anxiolytics: 12% | |||

| Lengacher 2014 | MBSR | 167 | 0 (13%) I (32%) II (37%) III (19%) | 56.6c | — | Nob | 82%c | Antidepressants: 14% Anxiolytics: 18% |

| UC | 155 | 0 (12%) I (36%) II (35%) III (17%) | 83%c | antidepressants: 9% anxiolytics: 10% | ||||

| Lerman 2012 | MBSR | 53 | Canceri | 58 ± 11 | 3.9 ± 5.1 years | Unclear | 83%c | — |

| UC | 24 | 57 ± 10 | 3.7 ± 3.5 years | 75%c | ||||

| Shapiro 2003 | MBSR | 31 | No information available | |||||

| UC | 32 | |||||||

| Wurtzen 2015 | MBSR | 168 | I (30%) II (65%) III (5%) | 54 ± 10 | 7.5 ± 5.0 months | RT (74%) CT (46%) | 77%e | ET: 54% of pts Use of subsidised psychologist sessions: 18% |

| UC | 168 | I (38%) II (60%) III (2%) |

54 ± 11 | 7.9 ± 5.1 months | RT (86%) CT (49%) | ET: 52% of pts Use of subsidised psychologist sessions: 24% | ||

| Zaidi 2015 | No information available | |||||||

| Zhang 2017 | MBSR | 30 | I (10%c) II (91%c) III (17%c) | 48.7 ± 8.5 | — | RT or CT (60%c) RT and CT (40%c) | 30%c | — |

| UC | 30 | I (17%c) II (70%c) III (13%c) | 46 ± 5.1 | RT or CT (73%c) RT and CT (27%c) | 20%c | |||

| BC: breast cancer; CT: chemotherapy; ET: endocrine therapy; MBSR: mindfulness‐based stress reduction; pts: participants; RT: radiation; SD: standard deviation; UC: usual care. | ||||||||

aMean, range. bSee Characteristics of included studies for exclusion criteria. cCalculated by review author (LS). dPatients analysed. eNot reported per arm respectively. fSD not reported. gSocial grade: AB ("higher and intermediate managerial/ administrative/professional"), ranging from AB to E (no data on college attendance). hAt least some additional education after secondary school. iData available for breast cancer patients only (34/48 of analysed patients in MBSR group, 14/20 of analysed participants in control group) .

Participants

Eight of the ten trials included in the meta‐analysis recruited participants with non‐metastatic breast cancer only (stages ranging from 0 to III). Two trials did not restrict participation to a certain cancer type; however, Lerman 2012 provided separate data for the breast cancer patients, and the proportion of breast cancer patients in Johns 2014 exceeded 80%.

The mean age ranged from 46 years to 59 years (Lengacher 2009 gave percentages only for three age categories).

Participants in six trials were eligible only after completion of cancer treatment, while three trials allowed concurrent treatment – although less than 80% actually received it (Henderson 2013; Wurtzen 2015; Zhang 2017). For Lerman 2012, it was unclear whether participants with concurrent treatment were eligible or not.

Four studies reported mean time since diagnosis, which ranged from seven months to 4.1 years (Bower 2015; Hoffman 2012; Lerman 2012; Wurtzen 2015). Participants included in Henderson 2013 had been diagnosed within the previous two years.

In seven trials, more than two‐thirds of participants had received at least some college education. Hoffman 2012 did not report baseline education status; however, almost three‐quarters of included participants were graded as the highest social grade 'AB' (higher and intermediate occupational position). More than two‐thirds of included participants in Kenne 2017 had received at least some additional education after secondary school. This was in stark contrast to participant education status in Zhang 2017, where a maximum 30% of participants had attended college. It is unclear why most participants included in the studies were highly educated, since no study listed this as an inclusion criterion. Less educated participants may have chosen not to engage in this activity or may have attended other clinics.

Interventions

Four trials implemented the standard MBSR intervention as described in the Description of the intervention (Hoffman 2012; Lerman 2012; Wurtzen 2015; Zhang 2017). The remaining six studies deviated to some degree: Henderson 2013 did not state the target time for home practice, and three additional monthly two‐hour sessions were part of the intervention. Bower 2015, Johns 2014, Lengacher 2009 and Lengacher 2014 held fewer than eight classes, did not offer a one‐day retreat and required shorter home practice. Kenne 2017 also did not include a one‐day retreat and envisaged shorter home practice.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

Quality of life

Nine studies assessed short‐term quality of life (Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Johnson 2015; Koumarianou 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Lerman 2012; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015). The questionnaires used were SF‐36, FACT‐B and EORTC (QLQ‐C30 and BR23). However, only data from three studies with 339 participants were available for meta‐analysis (Hoffman 2012; Lengacher 2009; Lerman 2012; see Effects of interventions).

Eight studies assessed medium‐term quality of life (Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Johnson 2015; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2014; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015). The questionnaires used were SF‐36 and FACT‐B. However, only data from three studies with 428 participants were available for meta‐analysis (Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Kenne 2017; see Effects of interventions).

Henderson 2013 provided long‐term data (FACT‐B) at 24 months from baseline.

Secondary outcome measures

Overall survival

None of the trials reported overall survival.

Fatigue

For the short‐term analysis, data from five studies were available for meta‐analysis (Bower 2015; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014). The questionnaires used were FSI (subscale severity or not reported), POMS (domain fatigue/inertia) and the revised Symptom Checklist (SCL)‐90‐R (subscale fatigue). Trialists reported the results either at the end of the intervention or at 8 to 12 weeks from baseline (Table 4).

3. Selected time points for outcomes.

| Assessment time pointsa | Bower 2015 | Henderson 2013 | Hoffman 2012 | Johns 2014 | Kenne 2017 | Lengacher 2009 | Lengacher 2014 | Lerman 2012 | Wurtzen 2015 | Zhang 2017 |

| Short‐term analysis | ||||||||||

| End of intervention | FT, DE, SL | — | — | FT, AX, DE, SL | — | QoL, FT, AX, DE, SL | FT, AX, DE, SL | QoL, AX, DE | — | AX |

| 8 to 12 weeks from baseline | — | — | QoL, FT, AX, DE | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Medium‐term analysis | ||||||||||

| 12 to 14 weeks from baseline | — | — | QoL, FT, AX, DE | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12 weeks from baseline | — | — | — | — | — | — | FT, AX, DE, SL | — | — | — |

| 1 month after intervention | — | — | — | FT, AX, DE, SL |

QoL,AX, DE |

— | — | — | — | — |

| 2 months from baseline | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | AX, DE, SL | — |

| 3 months after intervention | FT, DE, SL | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | AX |

| 4 months from baselineb | — | QoL, AX, DE | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 6 months from baseline | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | AX, DE, SL | — |

| Long‐term analysis | ||||||||||

| 12 months from baseline | — | QoL, AX, DE | — | — | — | — | — | — | AX, DEc,—d | — |

| 24 months from baseline | — | QoL, AX, DE | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| AX: anxiety; DE: depression; FT: fatigue; QoL: quality of life; SL: quality of sleep | ||||||||||

aSelected time points for an outcome are marked in bold. bEnd of intervention for Henderson 2013. cAt 12 months, fewer than 70% of randomised participants were evaluated for depression in the study Wurtzen 2015. dNo SD for quality of sleep reported (neither obtainable from Haller 2017)

Four studies using two different questionnaires (FSI (subscale severity) and POMS (domain fatigue/inertia)) were included in the medium‐term analysis (Bower 2015; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2014). The results were reported at one to three months after the intervention (Table 4).

No long‐term data were available for fatigue.

Anxiety

For the short‐term analysis, data from six studies were available for meta‐analysis (Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Lerman 2012; Zhang 2017). The trials used four different questionnaires: General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD‐7), POMS (subcale tension/anxiety), SCL‐90‐R (subscale anxiety) and STAI (state scale), reporting results either at the end of the intervention or at 8 to 12 weeks from baseline (Table 4).

The medium‐term analysis included seven studies (Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2014; Wurtzen 2015; Zhang 2017). They used six different questionnaires: the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), GAD‐7, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; dimension anxiety), POMS (subcale tension/anxiety), STAI (state scale) and SCL‐90‐R (subscale anxiety), reporting results at three to six months from baseline (Table 4).

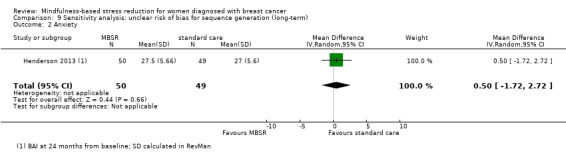

Henderson 2013 (BAI at 24 months from baseline) and Wurtzen 2015 (SCL‐90‐R (subscale anxiety) at 12 months from baseline) provided long‐term data.

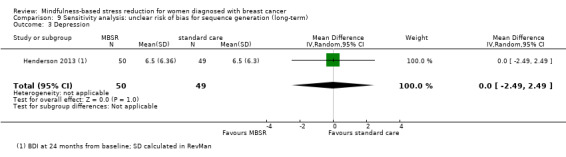

Depression

For the short‐term analysis, data from six studies were available for meta‐analysis (Bower 2015; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Lerman 2012). They used four different questionnaires: CES‐D, the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ‐8), POMS (subscale depression/dejection) and SCL‐90‐R (subscale depression). The results were reported either at the end of the intervention or at 8 to 12 weeks from baseline (Table 4).

Seven studies were included in the medium‐term analysis (Bower 2015; Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2014; Wurtzen 2015), using six different questionnaires: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), CES‐D, HADS (dimension depression), POMS (subcale depression/dejection), PHQ‐8 and SCL‐90‐R (subscale depression). The results were reported between three and six months from baseline (Table 4).

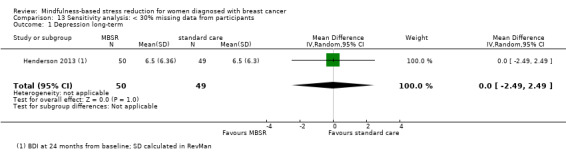

Henderson 2013 (BDI at 24 months from baseline) and Wurtzen 2015 (CES‐D at 12 months from baseline) provided long‐term data.

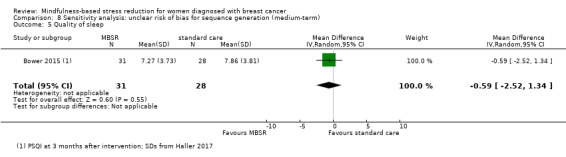

Quality of sleep

For the short‐term analysis, data from four studies were available for meta‐analysis (Bower 2015; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014). The questionnaires used were the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), PSQI and SCL‐90‐R (subscale disturbed sleep). The results were reported at the end of the intervention (Table 4).

Four studies were included in the medium‐term analysis (Bower 2015; Johns 2014; Lengacher 2014; Wurtzen 2015). Three different questionnaires were used (ISI, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOSS; sleep problem index II) and PSQI), and the results were reported at three to six months from baseline.

No long‐term data were available for quality of sleep.

Adverse events

None of the trials reported adverse events.

Conflicts of interest

For all studies included, the authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight studies. Lengacher 2012 reported sub‐studies of an included trial, Lengacher 2014, describing considerably fewer participants than in the parent study. The studies by Carlson 2013 and Carlson 2015 were excluded since the control intervention consisted of a one‐day stress management course and therefore does not correspond to our control intervention. Less than 80% of participants in Branstrom 2012 had breast cancer. The study author of Carmody 2011 clarified that a history of breast cancer was an exclusion criterion for that trial. Two studies by Rhamani were excluded since they were both described as quasi‐experimental and as randomised and we therefore judged them as non‐randomised (Rahmani 2014; Rahmani 2015). Finally, we excluded Johannsen 2016 because the study investigated the effects of a mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, which does not correspond to our intervention.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

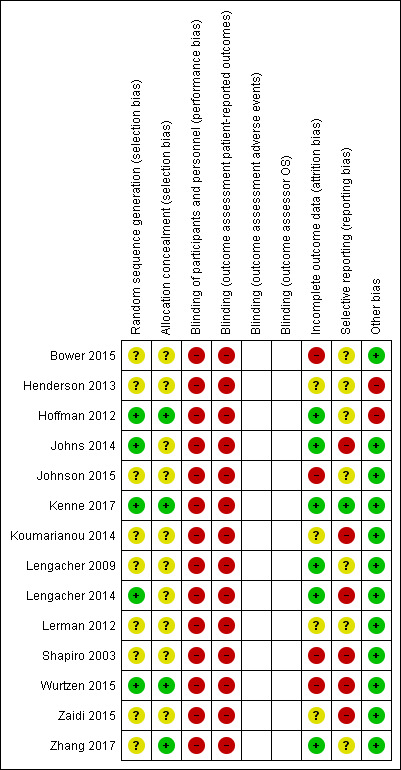

Three studies were at low risk of selection bias (Hoffman 2012; Kenne 2017; Wurtzen 2015). Two studies reported adequate methods of sequence generation but did not report allocation concealment in sufficient detail (Johns 2014; Lengacher 2014). For Zhang 2017, the information on sequence generation was deemed insufficient, but allocation concealment was judged to be adequate. Eight studies did not report methods of sequence generation or allocation concealment in sufficient detail (Bower 2015; Henderson 2013; Johnson 2015; Koumarianou 2014; Lengacher 2009; Lerman 2012; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015). For a summarised presentation see Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Blinding

In the context of the studies included, participants could not be blinded. Since the only data available were patient‐reported outcomes, we considered all studies to be at high risk of performance and detection bias. For a summarised presentation see Figure 2.

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in six studies (Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Zhang 2017), and it was high in four (Bower 2015; Johnson 2015; Shapiro 2003; Wurtzen 2015). The remaining five studies did not adequately describe loss to follow‐up and were at unclear risk of bias (Henderson 2013; Koumarianou 2014; Lerman 2012; Zaidi 2015). For a summarised presentation see Figure 2.

Selective reporting

When studies did not have publications on study design or study protocols available, we rated them as being at unclear risk of bias unless we observed outcome discrepancies between the Methods and Results sections. The risk of reporting bias was low in Kenne 2017 because reported outcomes were consistent with a publication on study design. It was high in six studies, since results were not usable for meta‐analysis (Johns 2014; Koumarianou 2014; Lengacher 2014; Shapiro 2003; Wurtzen 2015; Zaidi 2015). For a summarised presentation see Figure 2.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies were at risk of other potential biases: In addition to the standard MBSR intervention, participants in Henderson 2013 received three monthly two‐hour sessions following completion of the MBSR. Participants in Hoffman 2012 received an average of 30 hours of 'The London Haven' support before study entry. For a summarised presentation see Figure 2.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Unless specified otherwise, results from all sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis) yielded the same results as the standard data analysis.

Ten studies in 1571 participants were included in the meta‐analysis (Bower 2015; Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Johns 2014; Kenne 2017; Lengacher 2009; Lengacher 2014; Lerman 2012; Wurtzen 2015; Zhang 2017), while four studies collected data on quality of life but either presented no results or did not report results usable for quantitative analysis (Johnson 2015; Koumarianou 2014; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015). These four studies included 185 participants (see Characteristics of included studies).

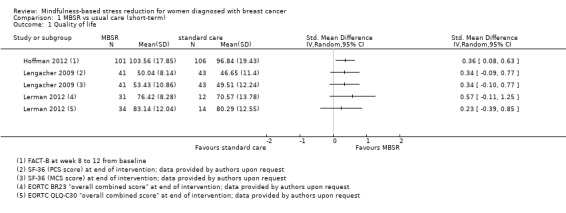

Quality of life

Short‐term results (end of intervention)

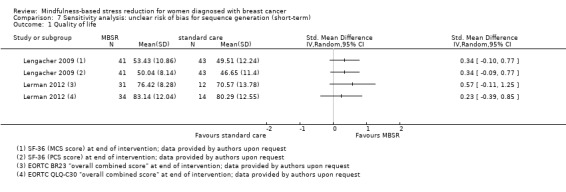

Three studies reporting data from 339 participants provided results for short‐term quality of life (Hoffman 2012; Lengacher 2009; Lerman 2012). Johns 2014 and Lengacher 2014 (357 total participants) also assessed this outcome but only partially reported results, while Johnson 2015,Koumarianou 2014,Shapiro 2003 and Zaidi 2015 assessed the outcome but either did not report results or presented results in a way not usable for quantitative analysis (see Characteristics of included studies). These four studies would have contributed another 185 additional participants to the meta‐analysis. The potential impact of these missing results is unclear. Due to these concerns about missing data, we did not perform a meta‐analysis but chose to apply vote counting: all three studies suggest a beneficial effect of MBSR. The corresponding results are reported in the Data and analyses section (Analysis 1.1; higher values correspond to higher quality of life (improvement)). Due to the missing data (suggesting potential publication bias) and imprecision, we judged the certainty of the evidence to be low. The result is confirmed by the analysis of change data (Analysis 14.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MBSR vs usual care (short‐term), Outcome 1 Quality of life.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis: change data (short‐term), Outcome 1 Quality of life.

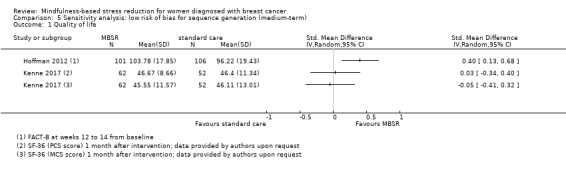

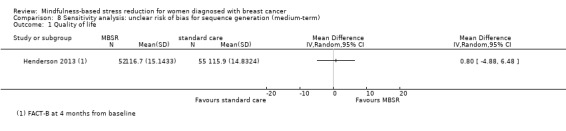

Medium‐term results (up to six months after baseline)

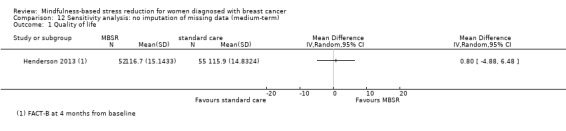

Three studies reporting data from 428 participants provided results for medium‐term quality of life (Henderson 2013; Hoffman 2012; Kenne 2017). Johns 2014 and Lengacher 2014 (total 357 participants) also assessed medium‐term quality of life but only partially reported it. Johnson 2015,Shapiro 2003 and Zaidi 2015 assessed the outcome but either did not report results or presented results in a way that was not usable for quantitative analysis (see Characteristics of included studies). These three studies would have contributed another 120 additional participants to the meta‐analysis. The potential impact of these missing results is unclear. Due to these concerns about missing data, we did not perform a meta‐analysis but chose to apply vote counting (see McKenzie 2018): one study suggests a beneficial effect of MBSR, while the two other studies suggest neither benefit nor harm. The corresponding results are reported in the Data and analyses section (Analysis 2.1; higher values correspond to higher quality of life (improvement)). Due to the missing data (suggesting potential publication bias) and imprecision, we judged the certainty of the evidence to be low.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MBSR vs usual care (medium‐term), Outcome 1 Quality of life.

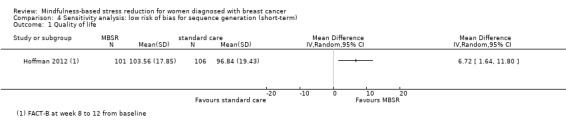

Long‐term results (more than 12 months after baseline)

Neither Johns 2014, Lengacher 2014 nor the four studies not reporting usable data on quality of life followed participants in the long term (Johnson 2015; Koumarianou 2014; Shapiro 2003; Zaidi 2015; see Characteristics of included studies). Thus, no long‐term data on quality of life are available. The evidence suggests that MBSR does not improve long‐term quality of life (MD 0.00 on questionnaire FACT‐B, 95% CI −5.82 to 5.82; 1 study; 97 participants; Analysis 3.1; higher values correspond to higher quality of life (improvement)); we rated the certainty of the evidence as low due to imprecision.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 MBSR vs usual care (long‐term), Outcome 1 Quality of life.

Overall survival

None of the trials reported overall survival.

Fatigue

Short‐term results (end of intervention)

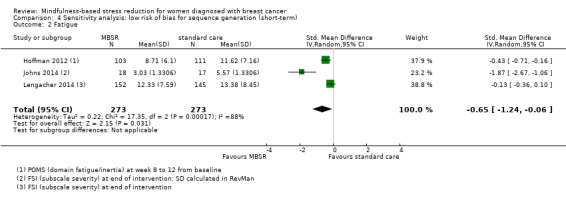

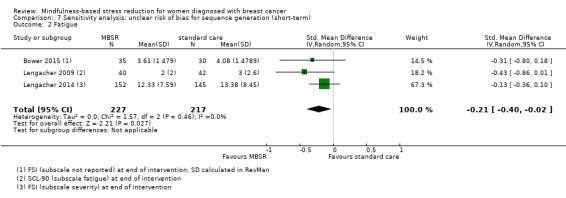

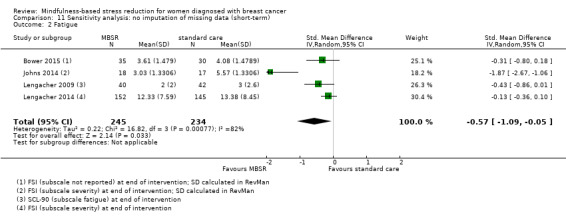

MBSR probably reduces short‐term fatigue (SMD −0.50, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.14; Analysis 1.2; higher values correspond to more fatigue (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference. This was based on five studies including 693 participants (moderate‐certainty data due to imprecision).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MBSR vs usual care (short‐term), Outcome 2 Fatigue.

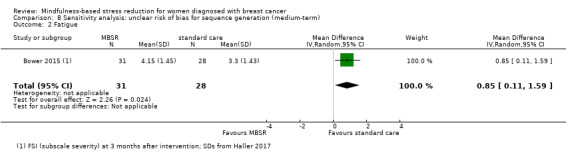

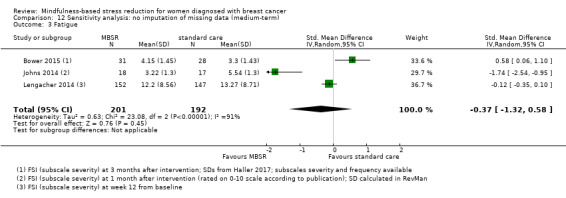

Medium‐term results (up to 6 months after baseline)

When looking at the medium‐term data on fatigue, MBSR probably results in little to no difference (SMD −0.31, 95% CI −0.84 to 0.23; Figure 3; Analysis 2.2; higher values correspond to more fatigue (deterioration)). The confidence interval is compatible with both an improvement and a deterioration in fatigue. This was based on moderate‐certainty data from four studies including 607 participants (see Table 1). A sensitivity analysis including only studies at low risk of bias with regard to sequence generation suggested a moderate beneficial effect but did not rule out that MBSR results in little to no difference (SMD −0.56, 95% CI −1.10 to −0.01; Analysis 5.2).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 MBSR vs standard care (medium‐term), outcome: 2.2 fatigue.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MBSR vs usual care (medium‐term), Outcome 2 Fatigue.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias for sequence generation (medium‐term), Outcome 2 Fatigue.

Long‐term results (more than 12 months after baseline)

No long‐term data were available for fatigue.

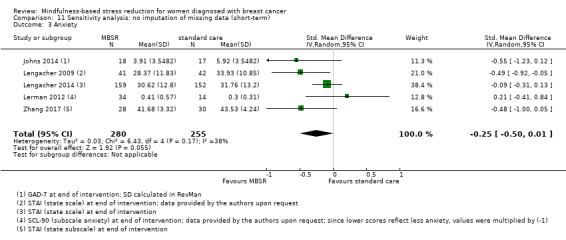

Anxiety

Short‐term results (end of intervention)

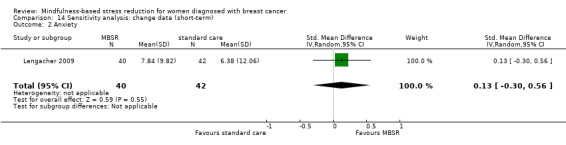

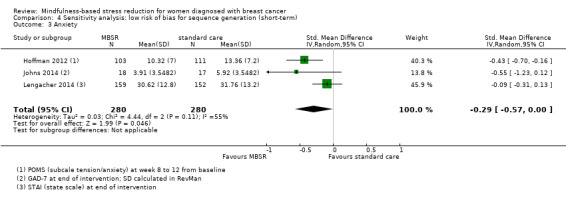

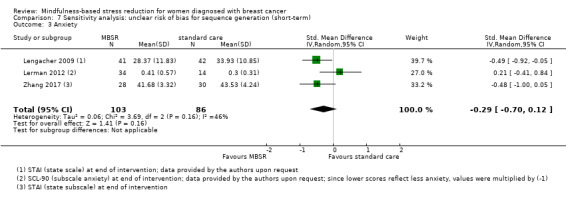

In the short‐term, MBSR probably reduces anxiety slightly (SMD −0.29, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.08, see Analysis 1.3; higher values correspond to more anxiety (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both a slight improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate‐certainty data due to imprecision (six studies with 749 participants). In contrast, the analysis of change data (based on a single study) suggests MBSR results in little to no difference (Analysis 14.2).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MBSR vs usual care (short‐term), Outcome 3 Anxiety.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis: change data (short‐term), Outcome 2 Anxiety.

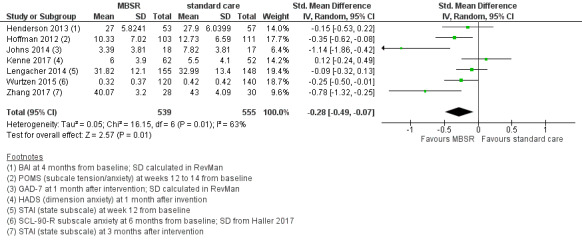

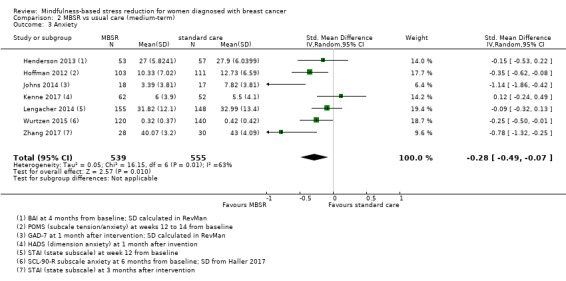

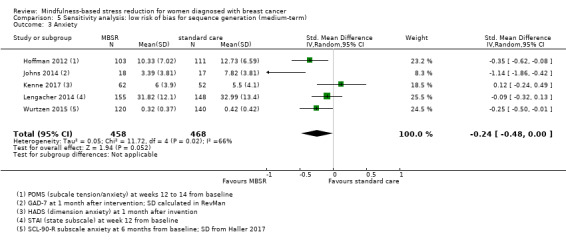

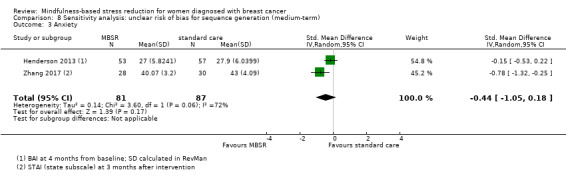

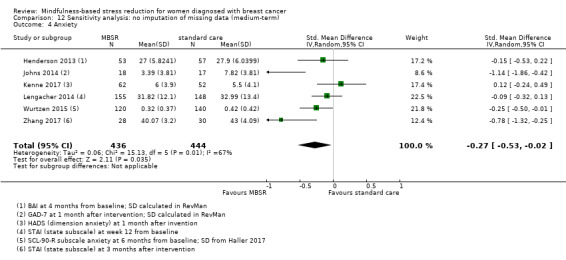

Medium‐term results (up to 6 months after baseline)

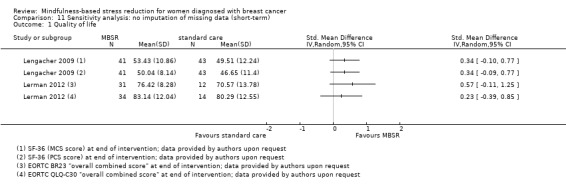

When looking at the medium‐term data, MBSR probably reduces anxiety slightly (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.07; Figure 4; Analysis 2.3; higher values correspond to more anxiety (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both a slight improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate‐certainty data from seven studies in 1094 participants (see Table 1).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 MBSR vs standard care (medium‐term), outcome: 2.3 anxiety.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MBSR vs usual care (medium‐term), Outcome 3 Anxiety.

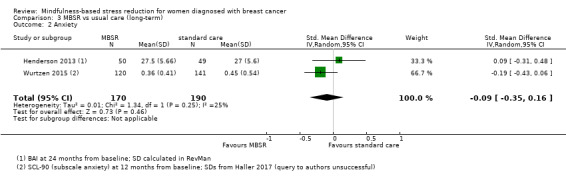

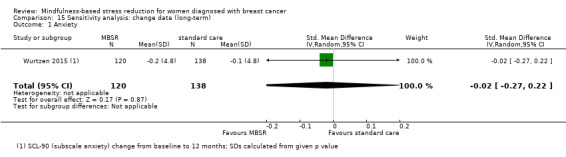

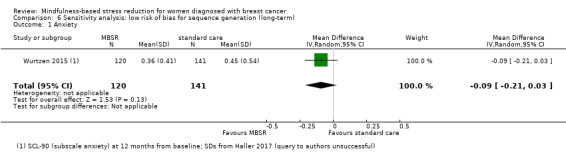

Long‐term results (more than 12 months after baseline)

The long‐term analysis suggests that MBSR probably results in little to no difference in anxiety (SMD −0.09, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.16; see Analysis 3.2; higher values correspond to more anxiety (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both a slight improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate‐certainty data due to imprecision (two studies with 360 participants). In contrast, the analysis of change data based on a single study suggests that MBSR results in little to no difference in long‐term anxiety (Analysis 15.1).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 MBSR vs usual care (long‐term), Outcome 2 Anxiety.

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sensitivity analysis: change data (long‐term), Outcome 1 Anxiety.

Depression

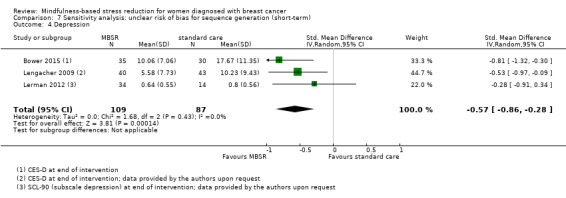

Short‐term results (end of intervention)

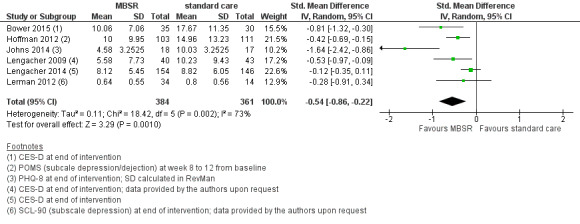

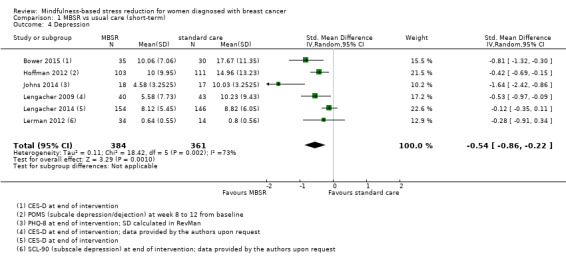

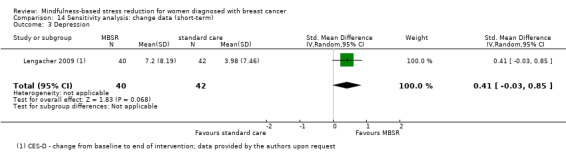

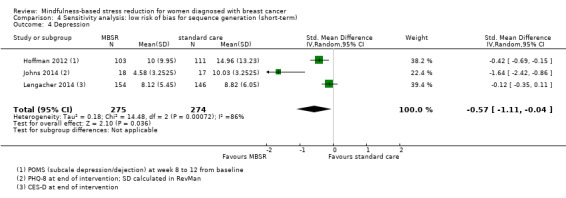

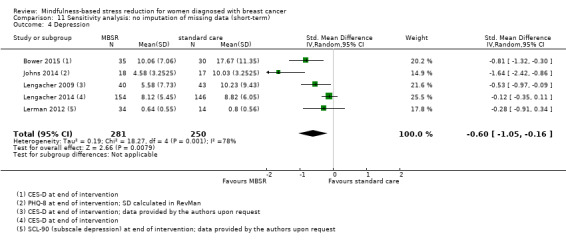

MBSR reduces short‐term depression (SMD −0.54, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.22; Figure 5Analysis 1.4; higher values correspond to more depression (deterioration)). This was based on high‐certainty data from six studies with 745 participants. The result is confirmed by the analysis of change data based on a single study (Analysis 14.3). Sensitivity analyses including only studiesat low risk of bias for sequence generation (SMD −0.57, 95% CI −1.11 to −0.04; see Analysis 4.4) and including only studies that did not use imputation for missing data (SMD −0.60, 95% CI −1.05 to −0.16; Analysis 11.4) did not conclusively rule out that MBSR makes little to no difference to short‐term depression.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 MBSR vs standard care (short‐term), outcome: 1.4 depression.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MBSR vs usual care (short‐term), Outcome 4 Depression.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis: change data (short‐term), Outcome 3 Depression.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias for sequence generation (short‐term), Outcome 4 Depression.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Sensitivity analysis: no imputation of missing data (short‐term), Outcome 4 Depression.

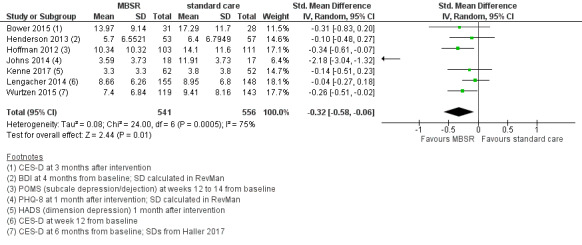

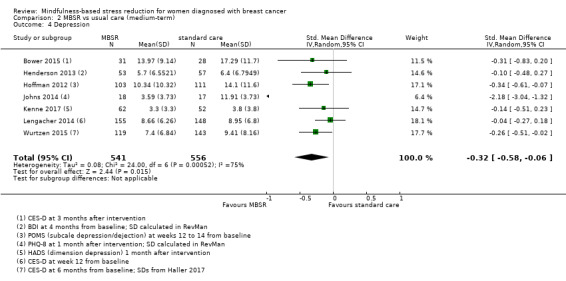

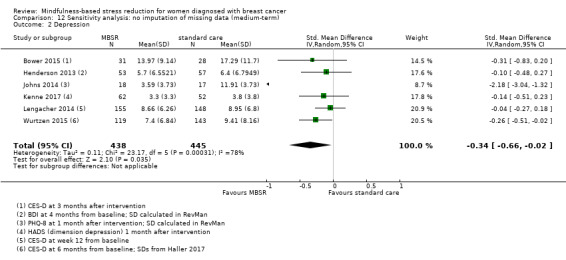

Medium‐term results (up to 6 months after baseline)

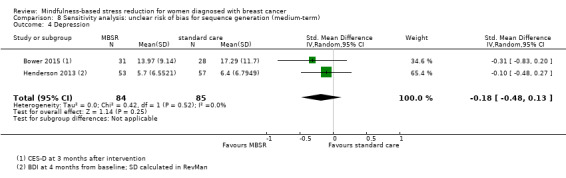

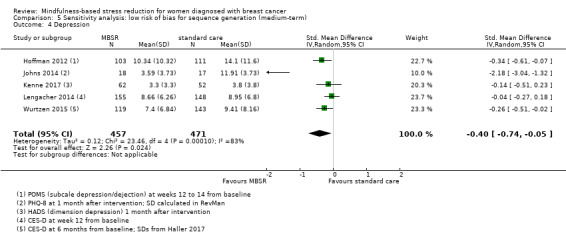

When looking at the medium‐term data, MBSR probably reduces depression slightly (SMD −0.32, 95% CI −0.58 to −0.06; Figure 6Analysis 2.4; higher values correspond to more depression (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate‐certainty data from seven studies with 1097 participants (see Table 1). A sensitivity analysis combining studies with an unclear risk of bias due to sequence generation suggested that MBSR may make little to no difference in depression, but it did not rule out a slight improvement (SMD −0.18, 95% CI −0.48 to 0.13; see Analysis 8.4).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 MBSR vs standard care (medium‐term), outcome: 2.4 depression.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MBSR vs usual care (medium‐term), Outcome 4 Depression.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Sensitivity analysis: unclear risk of bias for sequence generation (medium‐term), Outcome 4 Depression.

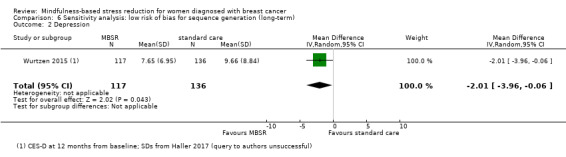

Long‐term results (more than 12 months after baseline)

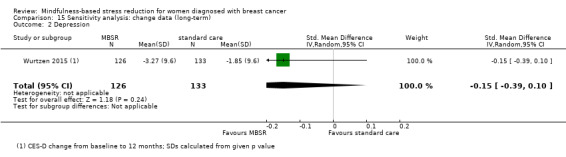

The long‐term analysis suggests that MBSR probably results in little to no difference in depression (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.05; Analysis 3.3; higher values correspond to more depression (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both a slight improvement and little to no difference. We rated the evidence as being of moderate certainty due to imprecision (2 studies with 352 participants). The result is confirmed by the analysis of change data based on a single study (Analysis 15.2).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 MBSR vs usual care (long‐term), Outcome 3 Depression.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sensitivity analysis: change data (long‐term), Outcome 2 Depression.

Quality of sleep

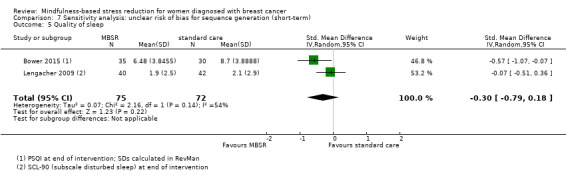

Short‐term results (end of intervention)

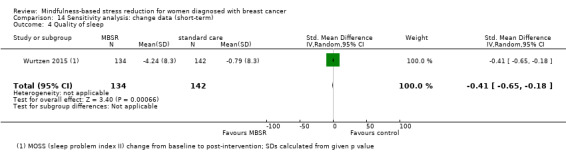

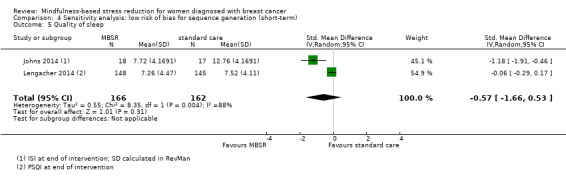

In the short‐term, MBSR probably slightly increases quality of sleep (SMD −0.38, 95% CI −0.79 to 0.04; see Analysis 1.5; higher values correspond to lower quality of sleep (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both a slight improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate certainty data due to imprecision (four studies with 475 participants). The result is confirmed by the analysis of change data based on a single study (Analysis 14.4). A sensitivity analysis including two studies at low risk of bias for sequence generation suggested that MBSR may make little to no difference in quality of sleep (SMD −0.57, 95% CI −1.66 to 0.53; see Analysis 4.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MBSR vs usual care (short‐term), Outcome 5 Quality of sleep.

14.4. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis: change data (short‐term), Outcome 4 Quality of sleep.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Sensitivity analysis: low risk of bias for sequence generation (short‐term), Outcome 5 Quality of sleep.

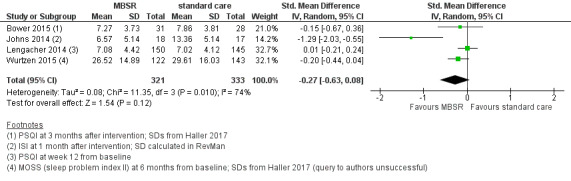

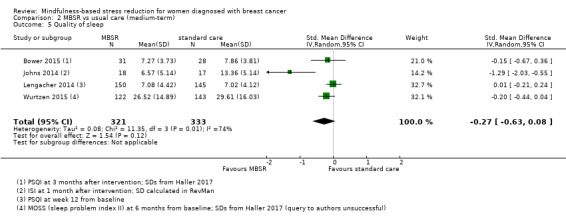

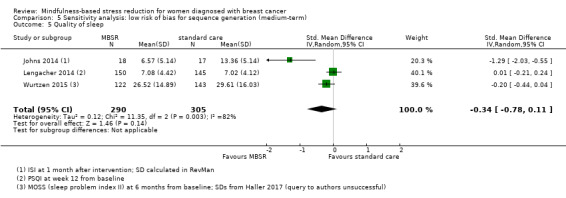

Medium‐term results (up to 6 months after baseline)

When looking at the medium‐term data, MBSR probably slightly increases quality of sleep (SMD −0.27, 95% CI −0.63 to 0.08, see Figure 7 and Analysis 2.5; higher values correspond to lower quality of sleep (deterioration)). However, the confidence interval is compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference. This was based on moderate‐certainty data from four studies with 654 participants (see Table 1).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 MBSR vs standard care (medium‐term), outcome: 2.5 quality of sleep.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 MBSR vs usual care (medium‐term), Outcome 5 Quality of sleep.

Long‐term results (more than 12 months after baseline)

No long‐term data were available for quality of sleep.

Adverse events

None of the trials reported adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

MBSR may improve quality of life slightly in the short term but may result in little to no difference later on (medium‐term and long‐term analysis). We found evidence that MBSR probably reduces both short‐term and medium‐term anxiety, depression and short‐term fatigue, and that it probably improves quality of sleep (moderate‐certainty evidence). However, the confidence intervals are compatible with both an improvement and little to no difference (except for short‐term depression). In the long term, MBSR probably results in little to no difference in anxiety and depression (moderate‐certainty evidence). No study reported data on survival or adverse events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Of a total of 14 included studies, 4 did not report results usable for quantitative analysis (queries to authors were unsuccessful). These four studies would have contributed 185 additional participants to the meta‐analysis (1571 were actually included). All of these studies assessed quality of life, while one study (Koumarianou 2014) additionally assessed sleep and another study additionally assessed depression and anxiety (Shapiro 2003). The potential impact of these missing results on the meta‐analysis ‐ especially for quality of life ‐ is unclear.

The trials included in this review were carried out in the USA, Europe and China. Only four trials implemented the standard MBSR intervention as envisaged by Kabat‐Zinn (see Description of the intervention), while the remaining six studies deviated to some degree, for example by not offering a one‐day retreat. All trials included participants with early breast cancer and most participants received at least some college education. We found no studies investigating participants receiving both MBSR and concurrent treatment.

The results of this review are applicable to different MBSR practices. However, the participants included in the studies were quite homogeneous. Thus, it is uncertain whether the results of this review can be applied to patients with metastatic breast cancer, patients receiving concurrent therapy other than endocrine therapy or patients with lower education status.

We found no data on serious adverse events, making it difficult to balance the benefits and harms for MBSR. In addition, no survival data have yet been published. However, survival data for Kenne 2017 are expected in 2019.

Baseline data on additional psychological therapies or medication were reported only for some studies. Thus, we could not evaluate a potential co‐intervention bias.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were at high risk of performance and detection bias, since participants could not be blinded. We rated only 3 of 14 studies as being at low risk of selection bias. Six studies were at high risk of reporting bias.

Using the GRADE methodology, the certainty of evidence for all outcomes (except for short‐term depression and quality of life) was moderate due to imprecision. For short‐term depression, the data were of high certainty. The certainty of short‐term and medium‐term quality of life was low due to imprecision and risk of bias (publication bias). For long‐term quality of life, we judged the certainty of the evidence as low due to serious imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We did not analyse publication bias using funnel plots because no comparison had the required minimum of 10 studies. Although we carried out extensive searches for studies and contacted authors of identified studies to obtain unpublished information as well as to clarify published data, we cannot rule out the possibility of publication bias.

During the review, we decided to analyse the data in three separate comparisons (short‐, medium‐ and long‐term data). Since all studies differed in the time points reported and due to concerns about multiplicity issues, we believe this approach was appropriate. However, the cutoffs for analysis could have been chosen differently, for instance by defining short‐term data as 'one month after intervention' instead of 'end of intervention'. Different time cutoffs might lead to different results.

If trials used different scales to report questionnaire data, we used standardised mean differences (SMD) to determine effect sizes. However, there is some uncertainty whether cutoffs (low, medium, high effect) correspond directly to clinical effects or whether this relation is less pronounced (Leucht 2012).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Three current systematic reviews have evaluated the effect of MBSR on women with breast cancer.

A 2017 review by Haller 2017 included 10 studies, 2 of which were not considered relevant for this review (Johannsen 2016 applied mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, and Carlson 2013 compared MBSR with a stress‐management day). The present Cochrane Review additionally included Johns 2014 and Kenne 2017. Haller 2017 also analysed short‐, medium‐ and long‐term data but used different time cutoffs for short‐term data (closest to 2 months after the start of the intervention) and long‐term data (closest to 12 months after the start of the intervention). They report significant effects for short‐term quality of life and for long‐term anxiety but not for medium‐term fatigue or quality of sleep. The average effects were all below the threshold of minimal clinically important differences.

Huang 2016a considered non‐randomised studies as well as RCTs and did not conduct separate analyses per follow‐up interval. Analysing eight studies quantitatively, the authors found significant improvements for depression, anxiety and quality of life. The authors did not state whether effects were below or above minimal clinically important differences.

A 2016 review by Zhang 2016 included seven studies and did not conduct separate analyses per follow‐up interval. The authors found positive effects of MBSR for anxiety, depression and fatigue. The authors did not state whether the effects were below or above minimal clinically important differences.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

MBSR may be considered a supportive intervention for improving short‐term and medium‐term depression, anxiety and quality of sleep as well as short‐term fatigue in women with non‐metastatic breast cancer who have completed curative cancer treatment. However, doubts about the actual effects exist, since all confidence intervals – except for short‐term depression – were compatible with both a (slight) improvement and little or no difference. Moreover, we were unable to determine the effect on quality of life due to missing data. Data on harms were not reported, but it is reasonable to expect no major harmful outcome. No data were available for survival either.

Participants with no college education were greatly underrepresented in the trials, suggesting that the choice to use MBSR may depend to a large extent on the personal preference of patients. Availability may be an additional barrier to the implementation of MBSR in practice.

Implications for research.

All evidence in this review (except for short‐term depression) is of moderate or low certainty due to imprecision. Thus, an update of this review incorporating the four studies that did not report usable results (185 participants), as well as the 10 ongoing trials identified in this review (with an additional 1810 participants, see Results of the search), may lead to more precise results and ultimately to a more reliable body of evidence.

Four ongoing studies are investigating MBSR as an online intervention. In an update, these may have to be assessed separately since 'standard' MBSR takes place in a group setting, providing social support. However, an online mindfulness programme may be a valuable option for patients, for example from rural areas, who are not able to participate in weekly group sessions.

Only four trials implemented the standard MBSR intervention as envisaged by Kabat‐Zinn, while the remaining six studies deviated to some degree, for example by not offering a one‐day retreat. It is unclear whether a more intensive (e.g. number of group sessions attended, having participated in the one‐day retreat) mindfulness programme leads to a stronger effect.

Since two ongoing studies include women "currently under at least one adjuvant therapy" (Huang 2016b) or "undergoing radiotherapy" (NCT02900326), their results may provide information on the effectiveness of MBSR for women during active therapy (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). However, there is still a need to conduct trials on MBSR for women with metastatic breast cancer, since six of the ongoing trials exclude women with metastatic breast cancer from participating (for four trials, no information on breast cancer status as an inclusion criterion was available).

Further studies of MBSR should address all important outcomes. Ideally, they should measure patient‐reported outcomes using the same questionnaires at standardised time points. It would also be important to report baseline data on psychological treatment and use of medication to be able to investigate a potential co‐intervention bias.