Abstract

Background:

To assess effect of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 supplementation on pain relief in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Materials and Methods:

An open-labeled randomized trial was conducted comparing 60,000 IU 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 + calcium (1000 mg/day) combination [Group A] versus calcium (1000 mg/day) only [Group B], as supplement to existing treatment regimen in early RA. Primary outcome included (i) minimum time required for onset of pain relief (Tm) assessed through patients’ visual analog scale (VAS); (ii) % change in VAS score from onset of pain relief to end of 8 weeks. Secondary outcome included change in disease activity score (DAS-28).

Results:

At the end of 8-weeks, Group A reported 50% higher median pain relief scores (80% vs. 30%; P < 0.001) and DAS-28 scores (2.9 ± 0.6 vs. 3.1 ± 0.4; P = 0.012) compared to Group B; however, Tm remained comparable (19 ± 2 vs. 20 ± 2 days; P = 0.419). Occurrence of hypovitaminosis-D was lower (23.3%) compared to Indian prevalence rates and was a risk factor for developing active disease (Odds Ratio (OR) = 7.52 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 2.67–21.16], P < 0.0001). Vitamin D deficiency was significantly (P < 0.001) more common in female gender, active disease, and shorter mean disease duration. Vitamin D levels were inversely correlated to disease activity as assessed by DAS-28 (r = –0.604; P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Vitamin-D deficiency is a risk factor for developing active disease in RA. Weekly supplementation of 60,000 IU of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 in early RA results in greater pain relief. The number needed to treat for this additional pain relief was 2.

Identifier:

CTRI/2018/01/011532 (www.ctri.nic.in).

Keywords: 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3; early rheumatoid arthritis; pain relief; visual analogue scale

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune, inflammatory disease of unknown etiology.[1] It involves flares and remissions, flares being characterized by pain.[2] Both T-cell and B-cell lymphocytes have been implicated in such disease pathogenesis;[3,4] however, preliminary data suggest that RA associated diffuse musculoskeletal pain could be linked to vitamin D deficiency.[5]

Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin by the action of ultraviolet irradiation.[6] It has extraskeletal effects and immunomodulatory actions.[7,8,9] It decreases the production of inflammatory mediators like Interferon-Y (IFN-Y), Interleukin-2 (IL-2) and Interleukin-5 (IL-5) in Helper-T cells (Th-1) cells and increases the production of Interleukin-4 (IL-4) by Th-2 cells resulting in immunosuppressive action. Several studies have indicated the status of vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor in RA.[10,11,12,13,14] Vitamin D deficiency is also implicated in autoimmune conditions, such as diabetes mellitus type-1, multiple sclerosis, etc.[11]

The current standard therapy for RA is disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy along with anti-inflammatory therapy using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[15] Since symptomatic pain relief is a strong determinant of treatment compliance, several new biological agents that provide rapid relief of symptoms of pain and disability in RA have been approved. However, such therapies have prohibitive costs that curtails widespread usage, and hence treatment outcomes.[16]

Of late, many clinicians recommend 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 supplementation along with calcium supplementation in RA, mainly due to its positive role in RA-associated osteoporosis and suppression of autoimmunity. In fact murine models have shown that experimental arthritis can be prevented by administration of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3.[17] However, preliminary clinical data on role of supplementation of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 in early RA is inconclusive.[12,18] To this effect, the current study was designed to assess the effect of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 supplementation on pain relief in the setting of early RA.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki II declaration and protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (IEC) at KPC Medical College and Hospital, Jadavpur, Kolkata, India (KPCMCH/IEC/829). It was registered under www.ctri.nic.in (REF/2018/01/017016). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample population

Treatment-naïve early RA (duration <2 years) subjects attending rheumatology clinic at KPC Medical College and Hospital from June 2016 to June 2017 were enrolled. Participation was voluntary.

Exclusion criteria included (i) patients who had been on steroids during the past year; (ii) known to have disorders of calcium metabolism, such as malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, chronic renal failure, renal tubular acidosis or pancreatitis; (iii) known allergy to DMARDs, 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 or calcium supplements; (iv) patients unlikely for follow-up during study period; (v) patients unable to afford triple DMARD therapy; (vi) patients suspected to have vasculitis; (vii) patients unable to mark the pain scale; (viii) calcium intake >2 g/day; (viii) Paget's disease; (ix) hyperthyroidism; (x) pregnancy; (xi) women 45–55 years old or within 5 years of menopause. Subjects currently on osteoporosis medication, estrogen, or a spine or hip T-score ≤ −3.0 were also excluded.

Sample size

A pilot questionnaire survey was conducted to estimate minimum time required for onset of pain relief (Tm). A total of 25 patients with RA who were initiated on 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 therapy within the past 6 months were surveyed in the clinic. The survey data indicated that most patients had varying amounts of pain relief scores ranging from 20% to 70%. Median [interquartile range (IQR)] Tm was 44 days (15–180 days).

Calculation of sample size was based on the data obtained from initial study. A difference of ± 14 days was anticipated for early pain relief in patients receiving vitamin D3 and calcium. Alpha error was kept at 5% and the power of the study was placed at 80%. The calculated sample size was 68 in each arm. A 10% drop-out rate was estimated; hence, 75 patients were included in each study arm. Subjects enrolled in the initial survey were excluded.

Study design

The study was designed as 8-week, parallel, open-label, randomized trial. After initial protocol review by IEC, clinical screening was done for subject recruitment. Tender joint count (TJC), swollen joint count (SJC), biochemical, and relevant radiological investigations were undertaken. Disease activity markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) were assessed and disease activity score (DAS-28) score was calculated.

Eligible patients (n = 150) were then randomized using on-site computer-generated block randomization schedule in blocks of 4. Subjects were subsequently allocated in either of the following two groups (i) Group A (n = 75) receiving 1, 25 Vitamin D3 60,000 IU once weekly along with calcium carbonate (1000 mg/day); (ii) Group B receiving only calcium carbonate (1000 mg/day). Both groups were well-matched for baseline and demographic characteristics. Subjects were also asked to apply sunscreen (with Sun Protection Factor 65) for entire study period to adjust for confounding factors.

Outcome assessment

Primary outcome included (i) the minimum time (days) required for onset of pain relief (Tm); (ii) % change in visual analog scale (VAS)[19] score from onset of pain relief to end of 8-weeks. Secondary outcome included change in DAS-28.

Subjects had to mark pain as the percentage of pain on the VAS on recruitment and thereafter, every week for 8-week duration. Provision of sending VAS scores electronically to investigators was made to minimize loss to follow-up. The pain scale was standardized to 100% pain at study initiation. Secondary outcomes included changes in DAS-28 score.

Data Management and Analysis

Statistical analysis

An intention-to-treat protocol was followed. Subgroup comparisons were done with Student's independent sample t test for numerical data. Repeated measure Analysis of Variance (rANOVA) with post hoc Dunnet test was done for intragroup analysis. Chi-square test with Yates correction was used for categorical variables. Pearson's correlation was used to assess any relation between DAS-28 scores and vitamin D levels. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all measurements. All analyses were done using GraphPad package (2015 GraphPad Software, Inc, CA).

Results

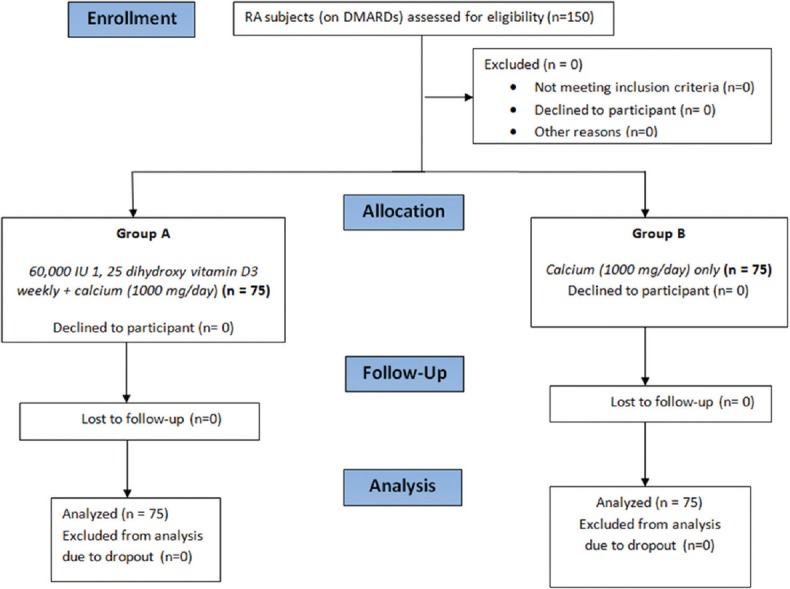

Figure 1 depicts the study progress. There were no drop-outs and complete data from all subjects was available for analysis. No major adverse events were recorded. In most cases, events like gastrointestinal upset, dermal rashes (e.g., with methotrexate therapy) were therapeutically managed with satisfactory outcomes.

Figure 1.

Adapted CONSORT flow-diagram showing study outline

Baseline demographic characteristics of study population have been described in Table 1. Both groups had well-matched baseline and demographic characteristics. Female representation was higher in both groups. Group A (vitamin D3 + calcium) reported significantly better scores in TJC; VAS, and DAS-28, Table 1. Improvement in disease activity for group B remained nonsignificant.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 150 study subjects with rheumatoid arthritis

| Variables | Group A (n=75) [Vitamin D3 + Calcium] | Group B (n=75)[Calcium] | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Range | 18-64 | 18-67 | 0.456 |

| Mean age±SD | 36.7±10.9 | 38.8±13.5 | |

| Median (IQR) | 36 (29-44) | 39 (29-53) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 10 (13.3) | 15 (20) | 0.27 |

| Female | 65 (86.6) | 60 (80) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 25.2±4.8 | 26.7±5.6 | 0.08 |

| Current or past smoker | 11 (14.6) | 9 (12) | 0.63 |

| Disease duration (months), mean±SD | 7.2±4.2 | 7.6±3.8 | 0.54 |

| Disease activity, n (%) | |||

| High | 3 (4) | 2 (2.6) | > 0.99 |

| Moderate | 66 (88) | 68 (90.6) | |

| Low | 6 (8) | 5 (6.6) | |

| Remission | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Disease status | |||

| TJC (Range) | 0-1 | 0-2 | 0.10 |

| SJC (Range) | 0-3 | 0-3 | 0.13 |

| ESR (mm/1st hr); mean±SD | 26±6.3 | 27.9±8 | 0.85 |

| CRP (mg/dL); mean±SD | 5.7±2.2 | 5.2±1.8 | 0.22 |

| VAS score; mean±SD | 74.2±9.6 | 73.9±9.9 | 0.85 |

| DAS-28 score; mean±SD | 3.5±0.4 | 3.9±2.8 | 0.44 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 30 (40) | 25 (33) | 0.95 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 15 (20) | 20 (27) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | |

| Lung disease | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | |

| Renal disease | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | |

| Anemia and hematological abnormality | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Ulcer and stomach disease | 19 (25) | 16 (21) | |

| Infectious disease | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | |

Group A: 60,000 IU 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 weekly + calcium (1000 mg/day); Group B: calcium (1000 mg/day), as supplement to existing DMARD regimen. SD: Standard deviation; IQR: Inter-quartile range; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAS-28: Disease activity score using 28-joints; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; VAS: Visual analogue scale. Disease activity was assessed according to the value of DAS28 score as follows: Remission: DAS28 ≤2.6, Low disease activity: 2.6 <DAS28 ≤3.2, Moderate disease Activity: 3.2 <DAS-28 ≤5.1, High disease Activity: DAS28 >5.1

Occurrence of hypovitaminosis-D was lower (23.3%) compared to Indian prevalence rates and was found to be a risk factor for developing active disease (OR = 7.52 [95% CI 2.67–21.16], P < 0.0001). Normal reference level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D was taken as 20 ng/mL, which marks the threshold below which parathyroid hormone (PTH) rises to compensate for the deficiency.

Table 2 depicts comparative outcome assessment between two treatment groups. At the end of 8-weeks, Group A reported 50% higher median pain relief scores (80% vs. 30%; P < 0.001) and DAS-28 scores (2.9 ± 0.6 vs. 3.1 ± 0.4; P = 0.012) compared to Group B; however, Tm remained comparable (19 ± 2 vs. 20 ± 2 days; P = 0.419). Number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve the additional 50% pain relief at the end of 8 weeks was 2 (NNT = 100/50% = 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between study arms in relation to primary outcome measures

| Variable | Group A [Vitamin D3 + Calcium] | Group B [Calcium] | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time required for onset of pain relief (days), mean±SD | 19±2 | 20±2 | 0.419 |

| % Reduction in VAS score at the end of 8 weeks (range) | 80 (0-100) | 30 (0-100) | <0.001** |

| DAS-28 score at the end of 8 weeks | 2.9±0.6 | 3.1±0.4 | 0.012* |

Group A: 60,000 IU 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 weekly+calcium (1000 mg/day); Group B: calcium (1000 mg/day), as supplement to existing DMARD regimen. VAS: Visual Analogue Scale. *P<0.05, **P<0.001, statistically significant

Table 3 depicts association analysis between subject characteristics and vitamin D status (normal versus low). Subjects with low vitamin D levels (23.3%) had significantly lower values (14.17 ± 3.27 ng/mL). Majority (94.3%) cases with low vitamin D levels were females with a mean age of 40.7 ± 12.8 years. Mean Body mass-index (BMI) was comparable in both groups. History of smoking was positive in nearly 13% cases in both groups.

Table 3.

Association analysis between subject characteristics and vitamin D status

| Variables | Vitamin D normala (n=115) | Vitamin D deficiencyb (n=35) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 36.8±9.43 | 40.7±12.8 | 0.160 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 65 (56.7) | 33 (94.3) | <0.001** |

| Smoking current/past, n (%) | 15 (13) | 5 (14.2) | 0.849 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 26.9±5.2 | 26.4±5.7 | 0.854 |

| Vitamin D level (ng/mL), mean±SD | 32.73±4.88 | 14.17±3.27 | <0.001** |

| Disease duration (months), mean±SD | 8.2±1.7 | 4.7±0.9 | < 0.001** |

| Active disease, n (%) | 24 (29.62) | 26 (74.28) | <0.001** |

| DAS-28 score, mean±SD [range] | 3.3±0.06 [0-8.2] | 3.6±0.01 [1.1-7.3] | <0.001** |

aVitamin D ≥20 ng/mL; bVitamin D <20 ng/mL; SD: Standard deviation; IQR: Interquartile range; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAS-28: Disease activity score using 28-joints; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; VAS: Visual analog scale. **P<0.001, statistically significant

With regard to disease status, mean DAS score at baseline in subjects with low vitamin D levels was significantly higher at 3.6 ± 0.01. Assuming DAS-28 >3.2 in case of active disease, 74.28% (n = 26) cases were diagnosed having active disease compared to 29.62% (n = 24) cases with normal vitamin D levels. Mean disease duration in vitamin D deficient population was significantly lower (4.7 ± 0.9 months).

Put together, vitamin D levels were lower in the setting of female gender (P < 0.001), higher disease activity (P < 0.001) and shorter mean disease duration (P < 0.001). The vitamin D levels were inversely correlated with disease activity assessed by DAS-28 (r = −0.604; P < 0.001).

Discussion

Preliminary data indicate that vitamin D deficiency is associated with clinical activity in RA. Hence, quantification of serum 25 (OH) vitamin D, consequently, vitamin D supplementation could possibly alleviate some symptoms in RA. Such findings should be an area of concern for primary care physicians. Being first point of contact in healthcare, they must include testing for patient vitamin D status in the yearly physicals. Moreover, since vitamin D deficiency may be seen as part of unhealthy habits such as poor nutrition, alcohol abuse, smoking, lack of physical exercise, etc., there must be due regard to health education of patients. Social economic factors may be part of the deficiency as well, and the sum total of all these factors leads to a poorer disease outcome in RA, of which vitamin D deficiency is probably both a causation and a sign.

Our study depicts that additional pain relief as clinical benefit in early RA could be achieved by supplementing existing DMARD therapy with 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 at 60,000 IU/week (8,571 IU/day). Similar findings have been reported in two previous unblinded studies.[18,20] However, many studies have indicated the contrary, for instance, a previous open-label study[21] had demonstrated no additional clinical benefit in RA, while a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (n = 117)[22] detected no change in RA-related pain scores following 12-weeks of vitamin D supplementation.

Clinically and statistically significant NNT measure of 2 denotes that one needs to treat only two RA patients with 60,000 IU/week of vitamin D for 8 weeks, to give additional 50% pain relief over and above the benefit achieved by standard DMARD regimen. In many ways, economical evaluation of long-term therapy costs of DMARD or biological agents may justify such supplementations.

Interestingly, time to onset of pain relief was comparable in both groups and not affected by vitamin D therapy. The delayed appearance of effect of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 could be a potential reason of the initial time lag to initial pain relief. The difference in VAS scores substantiates such finding, since the difference in VAS scores was comparable at baseline unlike by the end of 8 weeks, where group A reported higher pain relief scores.

The normal requirement of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 in normal adults is 200 IU/day,[23] but some studies have used doses as high as 50,000 IU/day in vitamin D-deficient patients without causing any dose-related toxicity.[24] In the current study, a higher dose of 60,000 IU/day was associated with higher pain relief. No serious adverse event was recorded either. However, whether using higher doses of vitamin D3 in short-term setting can result in better outcomes is an area of intense exploration.

Prevalence of vitamin deficiency at 23.33% in the current study is lower in comparison to data from Indian population.[25] The study data also found a strong inverse correlation between 25 hydroxy vitamin D levels and RA disease activity, despite conflicting preliminary data.[26,27,28,29] However, recent studies among RA patients from India corroborate our findings, for instance in studies conducted by Sharma et al.[30] (n = 80), Meena et al.[31] (n = 50), and Borukar et al.[32] (n = 42), it was found that serum vitamin D levels were inversely correlated with DAS-28 scores.

With regard to vitamin D status and disease activity, our study data indicated that vitamin D levels were lower in subpopulation with shorter mean disease duration. This trend is consistent with previous data depicting lower serum value of 25(OH) vitamin D in early RA in comparison with the patients experiencing established disease.[33] Moreover, this indicates that in the setting of a strong inverse correlation between serum vitamin D level and DAS-28 score, vitamin D deficiency can trigger and initiate disease sequelae in autoimmune conditions like RA.

Limitations

Despite having significant study findings, the key limitations which precluded the study included limited sample size, lack of placebo-control, and double-blinding. A single-dose arm rather than multiple-dose arm of 1,25 (OH) vitamin D3 was used as the study was designed to be a pilot study.

Hypovitaminosis-D was categorized according to Institute of Medicine[34] criteria of vitamin D repletion as 25(OH) vitamin D levels ≥20 ng/mL. Since most subjects (approximately 82%) had 25(OH) vitamin D levels >20 ng/mL at randomization, null findings in Group B (calcium only) might reflect vitamin D adequacy among many. Moreover, the fact that we studied vitamin D3 rather than vitamin D2 may implicate potential bias since vitamin D3 has a longer half-life, which might have prevented nadir levels during initial weeks, since insignificant changes in pain scores.

Conclusion

Vitamin-D deficiency is a risk factor for developing active disease in RA. Weekly supplementation of 60,000 IU of 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 in early RA results in greater pain relief. The number needed to treat for this additional pain relief was 2.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2205–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khurana R, Berney SM. Clinical aspects of rheumatoid arthritis. Pathophysiology. 2005;12:153–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keystone EC, Smolen J, van Riel P. Developing an effective treatment algorithm for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:v48–54. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P, Pathak K. Are biological targets the final goal for rheumatoid arthritis therapy? Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:1611–22. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.721769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirani V. Vitamin D status and pain: Analysis from the Health Survey for England among English adults aged 65 years and over. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1080–4. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason RS, Sequeira VB, Gordon-Thomson C. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:986–93. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandes de Abreu DA, Eyles D, Féron F. Vitamin D, a neuro-immunomodulator: implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S265–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewison M. Vitamin D and immune function: Autocrine, paracrine or endocrine? Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:92–102. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.682862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartley J. Vitamin D: Emerging roles in infection and immunity. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:1359–69. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahon BD, Wittke A, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. The targets of vitamin D depend on the differentiation and activation status of CD4-positive T cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:922–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jankosky C, Deussing E, Gibson RL, Haverkos HW. Viruses and vitamin D in the etiology of type 1 diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis. Virus Res. 2012;163:424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlino LA, Curtis J, Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Criswell LA, Saag KG. Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:72–7. doi: 10.1002/art.11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song GG, Bae SC, Lee YH. Association between vitamin D intake and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1733–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TH, Choi SJ, Lee YH, Song GG, Ji JD. Combined therapeutic application of mTOR inhibitor and vitamin D(3) for inflammatory bone destruction of rheumatoid arthritis. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:757–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JMW. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;46:406–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockley T, Costa-Font J, McGuire A. A Common Disease with Uncommon Treatment. European Guideline Variations and Access to Innovative Therapies for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Policy analysis centre. London School of Economics and Political Science. 2012. [Last accessed on 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/business-and-consultancy/consulting/assets/documents/a-common-disease-with-uncommon-treatment.pdf .

- 17.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1, 25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol inhibits the progression of arthritis in murine models of human arthritis. J Nutr. 1998;128:68–72. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andjelkovic Z, Vojinovic J, Pejnovic N, Popovic M. Disease modifying and immunomodulatory effects of high dose 1 alpha hydroxyl vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:453–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojkovich B, Gibson T. Day and night pain measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:434–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.7.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gopinath K, Danda D. Supplementation of 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 in patients with treatment naive early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:332–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:842–56. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hein G, Oelzner P. Vitamin D metabolites in rheumatoid arthritis: Findings--hypotheses--consequences. Z Rheumatol. 2000;59:28–32. doi: 10.1007/s003930070035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salesi M, Farajzadegan Z. Efficacy of Vitamin D in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate therapy. Rheumatol Int. 2011;32:2129–33. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1944-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau JC, Holick MF, Grant WB, Madronich S, et al. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:1129–40. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harinarayan CV, Ramalakshmi T, Prasad UV, Sudhakar D, Srinivasarao PV, Sarma KV. High prevalence of low dietary calcium, high phytate consumption, and vitamin D deficiency in healthy south Indians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1062–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun-Moscovici Y, Toledano K, Markovits D, Rozin A, Nahir AM, Balbir-Gurman A. Vitamin D level: Is it related to disease activity in inflammatory joint disease? Rheumatol Int. 2011;38:53–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr GS, Sabahi I, Richards JS, Caplan L, Cannon GW, Reimold A, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in rheumatoid arthritis and associations with disease severity and activity. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:53–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haque UJ, Bartlett SJ. Relationships among vitamin D, disease activity, pain and disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:745–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turhanoǧlu AD, Güler H, Yönden Z, Aslan F, Mansuroglu A, Ozer C. The relationship between vitamin D and disease activity and functional health status in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:911–4. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma R, Saigal R, Goyal L, Mital P, Yadav RN, Meena PD, et al. Estimation of vitamin D levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients and its correlation with the disease activity. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:678–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meena N, Singh Chawla SP, Garg R, Batta A, Kaur S. Assessment of Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis and its correlation with disease activity. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2018;9:54–8. doi: 10.4103/jnsbm.JNSBM_128_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borukar SC, Chogle AR, Deo SS. Relationship between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels, disease activity and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody levels in Indian rheumatoid arthritis patients? J Rheum Dis Treat. 2017 doi: 10.23937/2469-5726/1510056. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahebari M, Mirfeizi Z, Rezaieyazdi Z, Rafatpanah H. 25(OH) vitamin D serum values and rheumatoid arthritis disease activity (DS28 ESR) Caspian J Intern Med. 2014;5:148–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. In: Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al., editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56070/ doi: 10.17226/13050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]