Abstract

Introduction and Objective:

Palliative care can be of great help to people with dementia during their old ages. The aim of this study was to assess the use of palliative care in patients with dementia.

Methods:

Search was conducted in PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases. A step-by-step approach was used to identify relevant studies, and related studies of were demarcated and other studies were excluded. This study has used empirical studies, review studies, and guidelines for health organizations in different countries.

Results:

A total of 65 sources were used, of which 24 were completely related to the subject of the study. In related studies, the use of various ways and means of palliative care to improve quality of life, reduce pain, and prevent falling in people with dementia is discussed.

Discussion and Conclusion:

Palliative care can help people with dementia to improve their quality of life; however, more research is needed on the application and proper management of palliative care in patients with dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, disease management, pain relief, palliative care

Introduction

With the increase in the number of elderly, neurological assessments of this group have become more and more important, as a seemingly healthy person is likely to experience loss of performance at work or home due to a degenerative brain disease, brain tumor, and so on. Today, modern diagnostic methods, backed up with early diagnosis, provide a chance to prevent disease progression and improve symptoms.[1] One of the main diseases happening most commonly in the elderly is dementia (dementia). The definition of dementia has changed a lot since the introduction of the word about 300 years ago. Main standards in the definitions of dementia have changed and include the following:

-

Progression of multiple cognitive impairments including memory impairment and at least one of the following:[2]

-

(a)Aphasia, (b) apraxia (inability to perform prelearned tasks), (c) agnosia (disturbance in cognition), (d) impairment in executive performance

-

(a)

-

Cognitive defects should include the following features:

-

(A)Extremely severe, impairing occupational or social performance

-

(B)Indicating a decrease in the level of performance

-

(A)

Diagnosis should not be given when cognitive impairment occurs mainly in the period of delirium (disturbance in consciousness)

Etiology of dementia can be related to a general medical condition, permanent effects, and substance abuse, or a combination of these factors.[3,4]

The disease generally begins during elderly, and its onset is often the seventh and subsequent decades in the life of an individual; however, in rare cases, it might also occur when the individual is in his or her 50s or 60s, which is known as early dementia.[2]

Risk factors for multiple dementias include sex, hypertension, and so on; however, age is the most powerful risk factor for dementia.[4]

Alzheimer's disease is currently the sixth cause of death in the United States. The need for nursing and palliative care is essential in increasing the aged population and increasing the care burden of patients with dementia.[5] End-of-life care as a palliative care in people with dementia can be very important because it can reduce the social and psychological pressures of the family members.[6]

Generally, palliative care was founded for elderly people with cancer, and dementia was noted less frequently. In recent years, patients with dementia have become more and more prevalent. The reason for this is that in 1995, less than 1% of patients being taken care of had dementia, but in 2015 this figure has reached 15%.[7,8] Managing this disease can be very complicated because it has complex psychological symptoms and long-term illness can cause huge costs for families.[9]

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to review the use of palliative care in the field of dementia.

Research Methodology

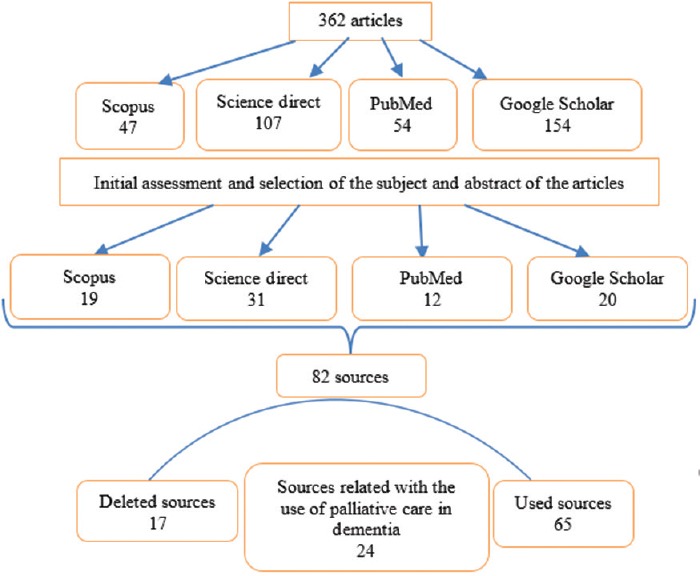

Researches related to the use of palliative care in patients with dementia have been reviewed in this article. Papers published between 1988 and 2017 were analyzed in this study; search in various databases such as ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus was conducted using the following keywords: care, nursing, palliative care, care needs, quality of life, end-of-life care, dementia, Alzheimer's, pain, and aging. Of the 362 articles found, 65 sources were used in this review article, of which 24 were completely relevant to the subject. Figure 1 presents a schema of the process of assessing and selecting related articles.

Figure 1.

A flowchart showing the process of selecting related articles

Diagnosis, Management, and Control of Dementia

One of the most important problems in the provision of palliative care services for people with dementia is the inability to diagnose this disease at an early age.[10,11] The lack of specific criteria for the survival of the disease for families, patients, and even clinical care providers can provide them with difficult conditions.[12] Although there is a high degree of heterogeneity in the early diagnosis of dementia, dementia leads to a stereotypical end point from diagnosis to an average of up to 5 years later, including reduced function, disability, weakness, and various medical complications.[12] Therefore, the final stages of dementia seem to be significantly similar to advanced cancer, congestive heart failure, or failure in other organs.[13]

Prognostic criteria for survival in patients with dementia have been documented by the National Institutes of Care and Palliative Care.[14] According to these criteria, if the patient undergoes functional evaluation in stage 7, he or she probably dies in 6 months. Functional assessment of stage 7 relies on all activities of daily living, intestinal and bladder incontinence, and speech restriction to more than 6 words. Medical conditions can include pneumonia, urinary tract infection, blood infections, or ulcers; nutritional drops include more than 10% weight loss in the last 6 months or serum albumin.[15]

It seems that informing families and care givers about dementia can help the community; however, more studies are still needed to identify related issues. For example, in a study by Mitchell et al. in 2009, only 18% of the family members with patients suffering from dementia discussed with doctors about dementia and its conditions.[16] They also suggested that awareness-raising and training for caregivers for palliative care in people with dementia help lessen rough interventions such as feeding tubes. Palliative care is the first step in knowing about the disease and managing it. Disease management includes measures and recommendations for screening, evaluating, detecting, and monitoring the initial stage of the disease and its adverse effects.[17]

Assessing and caring for physical issues focuses on symptom management, maintaining body health and cognitive function in the disease.[17] In relieving care in these patients, drug therapy is usually the top priority. If people are at risk due to aggressive and euphoric behaviors, treatment for aggression and stimulation with antipsychotics is recommended.[18] One of the things that is appropriate for palliative care and treatment is the proximity to Alzheimer's treatment centers, which can be easily accessed by caregivers in case of necessity.[19,20,21,22] To control pain in these patients, there are proper nonverbal strategies which can be provided to people with relief. The World Health Organization's pain reliever is an example;[23,24] feeding tubes is also prescribed for people with dementia.[19,20,21]

Psychological issues affected by the disease include mood, sleep, self-esteem, independence, and sexual acts.[17] Palliative cares provided to evaluate and treat depression and psychological interventions for challenging behaviors include music therapy, physical activity, massage therapy, aromatherapy, and light therapy.[25,26,27,28,29] Few articles have discussed problems arising from dementia in the domain of sexual behaviors.[30] Individual social domains include cultural values, financial resources, family ties, and sponsorship.[30] The most pessimistic content of community-based palliative care includes recommendations for assessing how family encounters and social support work.[18,20,21,22] One example of the content of palliative care in the social domain is to allow people with dementia to decide how to be cared for and treated.[31,32] Practical issues that affect the disease include daily activities, the transfer of people from home to the hospital, and support programs for long-term care.[33] The palliative care content includes functional evaluation tools as well as tips for helping families and people with dementia. Using note-taking of daily activities can also be part of the operational content.[34] To prevent the isolation of people with dementia in the community, it is better to engage them in social activities such as shopping and walking, as these can also be a way for families and caregivers to help patients.[35,36] Palliative care can be very useful in the long term because in some cases, such as chronic pain, falls, and hospitalization, individuals require a stimulus, and there might even be various problems, such as dehydration.[20,21,22] Religious services also seem to help people with dementia and their families.[37,38]

The Application of Palliative Care in Controlling Acute and Chronic Fall and Pain

Falling on the groups during old ages is a significant safety issue for patients with dementia and it has generally been considered as an important quality issue in long-term relief care. Usually, 60% of people with dementia fall over the course of the year,[39] and even some of them more than once suffer from painful falls. The use of psychological treatment drugs is effective in controlling falling which has created a crisis for caregivers and therapists.[40,41] Usually, falls can cause hospitalization, and sometimes even severe damage and death.[42,43] Despite the proper guidelines for use in palliative care, the amount of this has not been significantly reduced.[44,45] Usually, falling occurs during advanced dementia and late life. Risk factors are internal and external falling. Its internal state of affairs includes reduced coordination in step-by-step posture, instability, aggravated disease, and damage to the motor program.[46] When an individual experiences restlessness or incitement to pain or anxiety, falls may occur if provided care is inappropriate.[47]

There is controversy about the effects of medication on the aging population. Most studies have found no meaningful relationship between the use of analgesics and falls.[48,49,50] In addition to medications, external risk factors include inappropriate shoes, inappropriate motor aid, and environmental hazards.[51] Falling is responsible for almost 90% of deaths due to external factors in nursing and care centers.[52] One of the risk factors for hip fracture is mortality after pelvic fracture in 36 months in nursing and caring centers,[53] and dementia has a rate of more than 50%.[54] Most predictive tools deal with dementia deaths and have not discussed the incidence of dementia and deaths.[55] Unfortunately, fall has been used again as a warning for palliative care in people with dementia.[56] Of course, appropriate factors such as palliative performance scales[57] and golden standards[58] can be appropriate palliative approaches to avoid falling.

Pain is also considered as a risk factor for falls.[47] Acute or chronic pain is one of the causes of suffering, restlessness, and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia. Due to the inability of these patients to meet their needs, it is likely that their pain will be ignored in different parts of their body.[54,59] Even when diagnosed, pain in patients with dementia is not treated and this leads to a greater degree of dementia.[60] Morrison and Siu reported that in a group of patients with pelvic fractures, people with dementia received a third of palliative substances compared with normal people.[54] This problem is so large that researchers can seek further research.[61,62] Detection of pain in patients with dementia seems necessary for caregivers and their families, especially since these people may not be able to speak and that they do not have the ability to diagnose pain.[63] There are several scoring scales for pain in patients with dementia who are unable to speak,[59] including the scale of pain assessment in advanced dementia.[64] These tools are valuable ways to help assess pain and follow-up in care settings. Pain should always be taken into consideration in this population of patients who typically require medical intervention. As a general rule, it is advisable to have regular medication on their drug schedule, since these patients are not able to apply for the required medications.[63] Conventional acetaminophen at doses up to 3,000 mg per day may be effective for some patients, as they can tolerate side effects. Opiates may initially be relaxing in patients, but they should be used with careful monitoring and tuning for proper pain management. A study found that 75% of patients with dementia who received palliative care were clinically high and 93% needed treatment with morphine, most of which resulted in pain control.[65]

Conclusion

Studies on the use of palliative care in people with dementia are somewhat new. The use of various methods of palliative care requires more studies and no single method can be determined as the “best” one for palliative care for people with dementia. Also, awareness of dementia has opened up new ways for researchers. The use of various drugs to relieve the pain of patients with dementia has been somewhat studied by the researchers, but it seems that the use of drugs to reduce pain in these patients requires specific standards so that caregivers can use these standards. One of the causes of pain in patients with dementia can be fall and pelvic fracture. Falling are signs of progression of dementia, and their increasing frequency and severity indicates the need for palliative approach to get away from this unpleasant state.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brown R, Ropper A. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology; Illustrated edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. Dementia and the amnesic (Korsakoff) syndrome with comments on the neurology of intelligence and memory; pp. 367–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small SA MR. Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias. In: Rowland LP, editor. Merritt's Neurology. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 771–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadock B, Virginia A, Sadock V, Kaplan H. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. Delirium, dementia and amnestic and other cognitive disorders and mental disorders due to a general medical condition in Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jancovic J. Neurology in Clinical Practice. 2004:4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alzheimer's Association. 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aminoff BZ, Adunsky A. Their last 6 months: Suffering and survival of end-stage dementia patients. Age Ageing. 2006;35:597–601. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ. Feasible criteria for enrolling end-stage dementia patients in home hospice care. Hosp J. 1995;10:47–54. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1995.11882798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldridge MD, Epstein AJ, Brody AA, Lee EJ, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. The impact of reported hospice preferred practices on hospital utilization at the end of life. Med Care. 2016;54:657. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Steen JT, Helton MR, Ribbe MW. Prognosis is important in decisionmaking in Dutch nursing home patients with dementia and pneumonia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:933–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1057–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA. 2010;304:1929–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf-Klein G, Pekmezaris R, Chin L, Weiner J. Conceptualizing Alzheimer's disease as a terminal medical illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2007;24:77–82. doi: 10.1177/1049909106295297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekerak RJ, Stewart J. Caring for the patient with end-stage dementia. Ann LongTerm Care. 2014;22:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hospice Eligibility Requirements. [Last accessed 2017 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.nhpco.org/hospiceeligibility-requirements .

- 15.Gozalo P, Plotzke M, Mor V, Miller SC, Teno JM. Changes in Medicare costs with the growth of hospice care in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1823–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1408705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Jones RN, Prigerson HG, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. Ottawa: Canada Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; 2013. Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care: Based on National Principles and Norms of Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palk E, Carlson L, Parker D, Abbey JA. Brisbane, Australia: Queensland University of Technology; 2008. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Care Pathways for People with Dementia Living in the Community. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabins PV, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS, Tariot PN. Guideline watch (October 2014): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Focus. 2017;15:110–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.15106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, Gordon M, Herrmann N, Rockwood K, et al. Recommendations of the 4th Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD4) Can Geriatr J. 2012;15:120. doi: 10.5770/cgj.15.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman HH, Jacova C, Robillard A, Garcia A, Chow T, Borrie M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 2.Diagnosis. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:825–36. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogan DB, Bailey P, Black S, Carswell A, Chertkow H, Clarke B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 4. Approach to management of mild to moderate dementia. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;179:787–93. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, Williams B, Hewett L, Chodosh J. Alzheimer's disease management guideline: Update 2008. Alzheimers Dementia. 2011;7:e51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorbi S, Hort J, Erkinjuntti T, Fladby T, Gainotti G, Gurvit H, et al. EFNS-ENS Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of disorders associated with dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1159–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raglio A, Sospiro F. Music therapy in dementia. Non Pharmacol Ther Dem. 2010;1:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, Markle-Reid M, Wood J, Culum I. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen NV, Jørgensen T, Ørtenblad L. Massage and touch for dementia. The Cochrane Database. Syst Rev. 2006:CD004989. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004989.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrester LT, Maayan N, Orrell M, Spector AE, Buchan LD, Soares-Weiser K. Aromatherapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003150. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003150.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forbes D, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Peacock S, Hawranik P. Light therapy for improving cognition, activities of daily living, sleep, challenging behaviour, and psychiatric disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003946. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003946.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzeng YL, Lin LC, Shyr YIL, Wen JK. Sexual behaviour of institutionalised residents with dementia – A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samsi K, Manthorpe J. Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:949–61. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS. Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia. 2016;15:1141–57. doi: 10.1177/1471301214555542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macdonald A, Cooper B. Long-term care and dementia services: An impending crisis. Age Ageing. 2006;36:16–22. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avila R, Bottino C, Carvalho I, Santos C, Seral C, Miotto E. Neuropsychological rehabilitation of memory deficits and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer's disease: A pilot study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1721–9. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004001100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karp A, Paillard-Borg S, Wang H-X, Silverstein M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Mental, physical and social components in leisure activities equally contribute to decrease dementia risk. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21:65–73. doi: 10.1159/000089919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis S, Byers S, Nay R, Koch S. Guiding design of dementia friendly environments in residential care settings: Considering the living experiences. Dementia. 2009;8:185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hebert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Religious beliefs and practices are associated with better mental health in family caregivers of patients with dementia: Findings from the REACH study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:292–300. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000247160.11769.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes JC, Robinson L, Volicer L. Specialist palliative care in dementia. Br Med J. 2005;330:57–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7482.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1701–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kröpelin TF, Neyens JC, Halfens RJ, Kempen GI, Hamers JP. Fall determinants in older long-term care residents with dementia: A systematic review. Int Psychogeri. 2013;25:549–63. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sterke CS, Beeck EF, Velde N, Ziere G, Petrovic M, Looman CW, et al. New Insights: Dose-response relationship between psychotropic drugs and falls: A study in nursing home residents with dementia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:947–55. doi: 10.1177/0091270011405665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER, Fong TG, Yang FM, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling [ersons with Alzheimer's disease: Frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1542–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nurmi I, Lüthje P. Incidence and costs of falls and fall injuries among elderly in institutional care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2002;20:118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vlaeyen E, Coussement J, Leysens G, Van der Elst E, Delbaere K, Cambier D, et al. Characteristics and effectiveness of fall prevention programs in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:211–21. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inouye SK, Brown CJ, Tinetti ME. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2390–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kallin K, Gustafson Y, Sandman P-O, Karlsson S. Factors associated with falls among older, cognitively impaired people in geriatric care settings: A population-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:501–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stubbs B, Binnekade T, Eggermont L, Sepehry AA, Patchay S, Schofield P. Pain and the risk for falls in community-dwelling older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:175–87.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woolcott JC, RichardsonKJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1952–60. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rolita L, Spegman A, Tang X, Cronstein BN. Greater number of narcotic analgesic prescriptions for osteoarthritis is associated with falls and fractures in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:335–40. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:30–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinovitch SN, Feldman F, Yang Y, Schonnop R, Leung PM, Sarraf T, et al. Video capture of the circumstances of falls in elderly people residingin long-term care: An observational study. Lancet. 2013;381:47–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61263-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ibrahim JE, Murphy BJ, Bugeja L, Ranson D. Nature and extent of external-cause deaths of nursing home residents in Victoria, Australia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:954–62. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Magaziner JS, Passarella MA, Mehta S, Werner RM. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1273–80. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrison RS, Siu AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA. 2000;284:47–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown MA, Sampson EL, Jones L, Barron AM. Prognostic indicators of 6-month mortality in elderly people with advanced dementia: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27:389–400. doi: 10.1177/0269216312465649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richfield E, Girgis A, Johnson M. Assessing palliative care in Parkinson's disease – Development of the NAT: Parkinson's Disease. In Palliative Medicine: Abstracts of the 8th World Research Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC); 2014 June 5-7; Lledida, Spain. Palliat Med. 2014;28:538–913. doi: 10.1177/0269216314532748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): A new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas K, Wilson JA, Team G. Prognostic indicator guidance (PIG). The Gold Standards Framework Centre in End of Life Care CIC. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk .

- 59.Zwakhalen SM, Hamers JP, Abu-Saad HH, Berger MP. Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: A systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scherder E, Oosterman J, Swaab D, Herr K, Ooms M, Ribbe M, et al. Recent developments in pain in dementia. BMJ. 2005;330:461–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7489.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snow AL, O’Malley KJ, Cody M, Kunik ME, Ashton CM, Beck C, et al. Aconceptual model of pain assessment for noncommunicative persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2004;44:807–17. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volicer L. Management of severe Alzheimer's disease and end-of-life issues. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:377–91. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haasum Y, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L, Kåreholt I, Johnell K. Pain treatment in elderly persons with and without dementia. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:283–93. doi: 10.2165/11587040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000043422.31640.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romem A, Tom SE, Beauchene M, Babington L, Scharf SM, Romem A. Pain management at the end of life: A comparative study of cancer, dementia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Palliat Med. 2015;29:464–9. doi: 10.1177/0269216315570411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]