Abstract

Background:

Patients absconding from psychiatric hospitals pose a serious concern for the safety of patients and public alike. Absconding is associated with an increased risk of suicide, self-harm, homicide, and becoming “missing” from society. There are only scarce data on profile and outcome of the absconding patients in India.

Aims:

To study the prevalence and describe the clinical and coercion characteristics of patients who abscond during inpatient care from an open ward.

Methodology:

“Absconding” was defined as patients being absent from the hospital for a period of more than 24 h. This is an analysis of absconding patients out of the 200 admitted patients at a tertiary psychiatric hospital. Descriptive statistic was used to analyze the demographic, clinical, and perceived coercion profile and outcome.

Results:

The absconding rate was 4.5 incidents per 100 admissions. Most of these patients were males, from a nuclear family, admitted involuntarily, belonging to lower socio-economic status, diagnosed with schizophrenia or mood disorder with comorbid substance use disorder and had absent insight. The MacArthur Perceived Coercion Scale score was 4.58 (±1.44), and 80% of the absconded patients felt subjective coercive experiences in most domains at admission. Out of the 9 absconded patients, 2 patients had completed suicides and one continued to remain untraceable.

Conclusion:

The absconded patients were males; admitted involuntarily; diagnosed with schizophrenia, mood disorder, and comorbid substance use disorder; and had absent insight and high perceived coercion. Absconding patients had the tendency to harm themselves and wander away from home.

Keywords: Absconding, guidelines, India, inpatients, psychiatry

Key message: a) Patients absconding from psychiatric hospitals pose a serious mental health concern. b) Absconding patients with mental illness had the tendency to harm themselves and wander away from home. c) There is a need to adopt a uniform guideline and legal provision across the country to deal with the absconding persons with mental illness.

INTRODUCTION

Absconding from psychiatric hospitals poses a serious concern for the safety of patients and public alike. Absconding of a person with mental illness from the hospital is associated with an increased risk for suicide, self-harm, homicide, and becoming “missing” from society. Absconding rates in psychiatric care are 5.58 patients/100 admissions in India, 4.28 patients/100 admissions in Ireland, 8.92 patients/100 admissions in the United States of America (USA), and 6.28 patients/100 admissions in the United Kingdom (UK).[1] It is interesting to note that the rates reduce when forensic cases are excluded in case of USA but not so in case of UK.[1] As expected, a systematic review found the absconding rates to be substantially lower for locked wards (1.34/100 admissions) compared to open wards (7.96/100 admissions). The trend remained similar even when event-based rates, i.e., events of absconding per 100 beds or 100 admissions, were calculated.[1] The rates of absconding have been found to be different across various parts of the world. It may because of reasons such as lack of operational definition of “absconding,” type of security measures, type of hospital care, presence of forensic patients, legal measures, and multiple other factors. Repeated absconders contributed to a large number of incidents, with a few studies reporting absconding rates around 50%.[2,3,4] Repeated absconders were more likely to be detained under the mental health act of the country, to be from a younger age group, to have a shorter duration of stay, to be of male sex, and to have a primary diagnosis of psychosis.[2,3,5,6,7,8]

A few studies have evaluated the antecedents leading to escape, according to hospital records and interview with nursing staff. Moore's study classified absconders as “opportunity takers” and “opportunity makers.” The former made an attempt to escape when an opportunity arose and had reported thoughts regarding absconding in the preceding few weeks, whereas the latter had planned their escape out.[9] Most common reasons identified in 210 absconding incidents were treatment failure, family issues, alcohol, finances, and influence of other patients.[2] Medication non-compliance in the preceding 2 days was a predictor for escape in a case comparison study.[10] Overall, the impression is that opportunistic absconders signal their intentions much before the actual escape.[1]

There have been four studies in the past from India looking into the above issue, but two out of the four studies were conducted in the same settings as the current study, about three decades ago. The first study, which was done in 1977 at a general hospital psychiatry unit (GHPU), found the absconding rate to be 11.6 per 100 admissions. The study did not find a significant difference between mentally ill and medically ill absconders.[11] The first study from our study settings, done in 1980, found that the annual incidence of absconding was 3.3% (n = 128).[12] The predictors of escape were being in the age group of 30 years or less, men, voluntary patients, and suffering from schizophrenia or mania. However, all absconders were traced out later.[13] The second study was done about a decade later and found overall rates of absconding at 1.85 per 100 admissions.[14] However, more cases of absconding were being reported from open wards compared to closed wards as detected in the earlier study.[11,12,13,14] The predictors of escape were also similar, with male gender and age less than 40 years predicting absconding from the ward.[13] The latest study, in 2008, from a GHPU, also found high rates of absconding as the previous study from a GHPU. Of the 231 admitted patients, 14.28% patients had absconded. The study also found the highest risk of absconding in the initial days of admission, and the absconders were more likely to have bipolar mania.[15]

In the above background, we aimed to study the socio-demographic, clinical profile, coercion profiles, and outcome of patients who absconded from a tertiary psychiatric hospital in south India.

METHODOLOGY

Study population

The study was carried out at the Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru. For the purpose of this paper, data were derived from a larger study that looked into the patient, family, and clinician perspectives on admission, treatment, and coercive experiences during psychiatric inpatient care. This is a review of the current status of absconding patients out of 200 admitted patients. These patients were recruited between June 2013 and September 2014.

Each day, maximum of 2 inpatients out of all psychiatric admission using computer generated random number sampling and who are aged 18 years and above were approached to participate in the study. Patients affected by mental retardation, organic brain syndromes, delirium, dementia, developmental disorders, or antisocial personality disorder were excluded. Patients’ written consent was obtained, in accordance with the ethical approval obtained for the study, after a comprehensive description of the study at the time of admission. The insight was graded as full, partial, or no insight, on the basis of awareness, attribution and acceptance about illness, and willingness to take treatment. The clinical and coercion (using McArthur Admission Experiences Survey)[16] assessments were done for all admitted patients at the time of admission, details of the assessments are published elsewhere.[17,18] Through a telephonic survey, we took separate oral informed consent and looked into the outcome of 9 absconded patients.

In this paper, we aimed to determine the socio-demographic, clinical, and coercion-related characteristics of the absconded patients who were admitted to the inpatient psychiatric facility. We included all the wards except two closed wards, which also has forensic wards, where patients referred from the legal system are admitted. Patients admitted to these open wards are either voluntary boarders or admission under special circumstances with a family member who also takes part in treatment decisions and therapeutic process. These wards are open wards with security guards posted at the main gates. Patients are allowed to go outside accompanied by an attendant. As per standardized operating procedure (SOP) of the institute, “Absconding” is defined as “patients being absent from the hospital ward without official permission for a period of more than 24 hours.” In addition, those who have not informed either caretaker or the in charge hospital staff and are not available for any mode of telecommunication were also considered as “absconding.” When patient absconded from the ward, we counseled the family members, issued a missing letter from the institute, and assisted the family in lodging the missing complaint in the nearest police station as the SOP of the institute. The families were informed about the need for continuation of inpatient care if the patient is found and continued to be a risk to self or others, to be a threat to the public or private party, or if they are found to have an inability to take care of self.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, NIMHANS, Bengaluru.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the level of statistical significance of P < 0.05. Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample were analyzed by descriptive statistics. The Chi-square test was used to assess discrete variables.

RESULTS

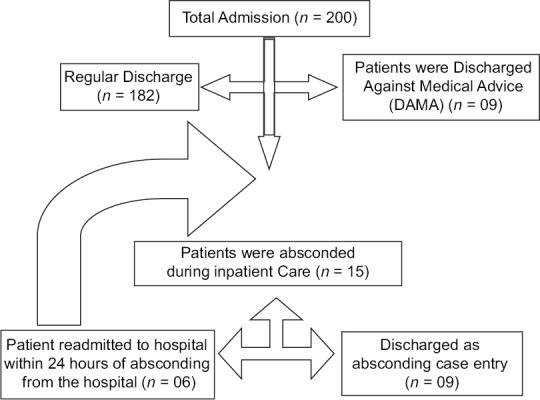

A total of 200 admitted patients were selected between June 2013 and September 2014. Out of these, 15 (7.5%) absconded from the hospital. Family members traced 6 patients within the next 24 h of absconding, and the inpatient care was continued. To the families of the remaining 9 (4.5%) patients, we issued a missing letter from the institute and assisted them in lodging the missing complaint. The patients were discharged as absconding case entry, which is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Discharge process in the hospital

Of 9 (4.5%) patients who were discharged as absconding case entry, 7 patients were male, single, and from a nuclear family and belonged to the below poverty line category. The mean age was 29.0 years, mean years of education was 9.5, the mean duration of inpatient care was 11.22 days, and mean Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI –S) score at admission was 5.75. Eight of them were admitted as “involuntary admission” (admission under special circumstance) with a request letter from caregivers. Mean duration of inpatient care among the absconded was 11.2 days, compared to 21.2 days in the overall sample.

After admission, 8 patients had expressed their unwillingness to stay as inpatients. Five patients had a psychotic spectrum disorder, 3 patients had a bipolar manic episode, and one patient had cannabis dependence syndrome. Three patients had comorbid alcohol dependence syndrome, 4 patients had comorbid nicotine dependence syndrome, and 1 patient had comorbid cannabis dependence syndrome.

None of the patients had insight into the illness at the time of admission, and 8 of the patients felt subjective coercive experiences at admission in most domains, such as 8 patients felt admitted against their will, 8 patients felt treated against their will, 6 patients felt they were sedated, 6 patients felt they were isolated, 6 patients felt they were restricted in interpersonal contact, 6 patients felt that their autonomy was taken away, 6 patients felt they were heavily medicated, and 6 patients felt there was a loss of dignity. Mean (± SD) score at admission on MPCS was 4.58 (±1.44) and on MacArthur Negative Pressure Scale was 2.7 (±1.6).

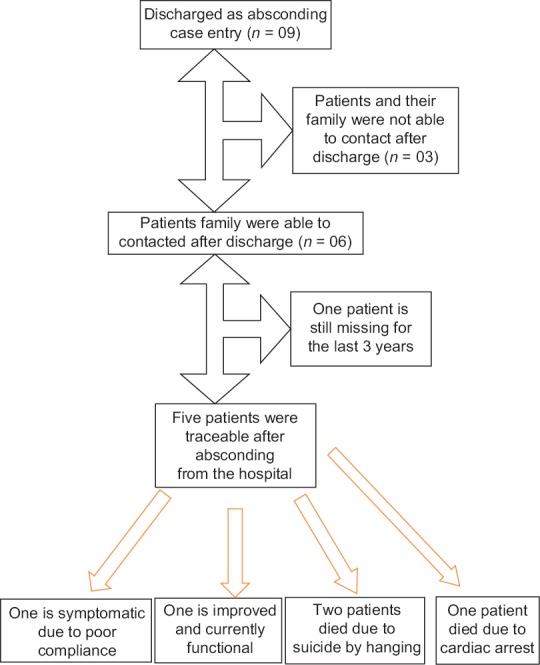

We reviewed the file and contacted the families of the 9 absconded patients. Figure 2 describes the outcome of the absconded patients. Mean duration to contact the patient after absconding was 3.8 (±5.7) days. Among 6 patients, whose families we were able to contact after the discharge, 5 patients had reached home: 4 patients by themselves and 1 patient through a relative. One patient is missing till date. Two patients were readmitted after reaching home, and rest 3 patients did not take further treatment. Three patients died over 4 years: 2 patients by hanging themselves (one by acting out on hallucination and another because of the felt stigma related to the psychiatric illness).

Figure 2.

Outcome of nine patients who absconded from the open ward

DISCUSSION

The absconding rate was 4.5 incidents per 100 admissions. This rate is high compared to previous studies from the same setting, where the rate was 3.3% in 1980[12] and 1.85% in 1977–87,[14] and low compared to the overall rate of 5.58% in India.[1] Worldwide, the rate of absconding ranges from 4.28% to 8.92%, with a mean of 7.96% in open psychiatric settings. We do not have data on absconding rates in locked wards to compare with the worldwide prevalence rate of 1.34%.[1,11,12,13,14]

In our study, the majority of absconded patients were male, single, from a nuclear family, and belonging to below poverty line. These findings are in line with past studies of absconding patients in a psychiatric setup.[1] With regard to diagnosis, in our sample, absconders had severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and comorbid substance use. At the time of admission, they were severely ill as per CGI –S scale and were admitted involuntarily. This finding is also supported by previous descriptive and case-control studies, which found psychotic illness to be a common factor predicting absconding.[2,10,19,20] A few studies have also found increased rates of affective illness, substance use, and personality disorders.[6,21,22] Most studies have been able to demonstrate an increased prevalence of involuntary patients among absconders,[3,7,20,23] which supports our findings. However, a case-control study could not demonstrate the above finding and instead suggested that the absconding incidents might be more officially reported among involuntary patients than the voluntary ones.[10]

Mean duration of inpatient care among the absconded was 11.2 days, compared to 21.2 days in the overall sample.[24] This finding is also in line with previous studies that absconder's escape relatively early during the inpatient stay has been a consistent finding.[3,25,26] Other studies evaluating the above question using patient interviews found domestic factors more implicated in the reasons for absconding. Most frequent reason reported by the absconded patient was the need to take care of family and children, to return to work, and other domestic issues.[27,28] This is further supported by the fact that most of them went home after absconding.[20,23] It is unclear to us whether similar issues would have been the reasons behind the absconding of our patients.

One of the most important aspects of studying these questions is the safety of the absconded patients and the public as a whole. As per the available information of 6 absconded patients, 2 patients completed suicide by hanging themselves, and one patient is still missing for the last 3 years. Hence, patients who had absconded were potentially dangerous to self, than to others, in our sample. Such a risk was observed in 50% of the absconded patients in comparison with 20% risk in other studies, where the risks were described as substance abuse, attempted suicide, aggression toward family, and wandering behavior.[19,28,29]

Absconding of psychiatric patients from the hospital can be prevented by identifying the high-risk population who are prone for absconding, such as patients admitted involuntarily, not willing to stay, having absent insight, with comorbid substance use disorder, early part of admission, and providing a one to one observation and care to patients in the ward. Other measures include establishing strong cohesive therapeutic relationships with patients, patient-centered care, use of least coercive settings, and minimization of restrictive environments. Hospital staff should make patients relatives aware and educate about the problem, keep the patients in close observation, patient centered care and monitoring of patients who are at a high risk of absconding, and also facilitate in bringing patients back to the hospital if a patient absconds.[15]

Educating the relatives (and the patients) about the consequences of absconding could be crucial in reducing the absconding rates. Patients’ relatives should be made aware of their crucial role in bringing patients back. The nursing staff and social workers has a key role in this psychoeducation. This can be facilitated by appointing a “psychiatric nurse” or “Social Worker” to work closely with the family toward the patient care.

Appointing a “psychiatric nurse” or “Social Worker” does not involve significant resources but rather a change in thinking. Such this approach will not only help to reduce absconding but improve the overall quality of patient care and reduce the medico–legal issues.

Absconding during inpatient care, legal relevance, and mental health law

As we have seen, the open wards with least restrictive alternative treatment and settings are associated with higher rates of absconding than locked ward or seclusive facility. However, new Mental Health Care Act – 2017 (MHCA) advocates care in the least restrictive settings and banned the seclusive care.[30] This may inturn increase absconding rates in the hospital settings. The MHCA-2017, sec-100, made it mandatory for officer-in-charge of the local police station to make aFirst Information Report (FIR) of missing person/wandering patients and to take him to nearest public health establishment.

CONCLUSION

The absconding rate is less in our study compared to the rest of the world. Patients who are admitted involuntarily, males, of low socio-economic status, diagnosed with schizophrenia or mood disorder and comorbid substance use disorder, and having absent insight and higher perceived coercion are associated with absconding from the hospital. Hence, the use of frequent assessment, vigilance, least coercive treatments, and alternatives may improve the outcome. Absconding was also a risk for completed suicide and wandering behavior. There is a need to adopt a uniform guideline across the country to deal with the absconding persons with mental illness so that the safety of the person with mental illness, family members, and society at large is ensured.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart Duncan BL. Absconding from psychiatric hospitals : Aliterature review. Inst Psychiatry, Maudsley. 2010;5:3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller DJ. The “missing” patient. A survey of 210 instances of absconding in a mental hospital. Br Med J. 1962;1:177–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5272.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Short J. Characteristics of absconders from acute admission wards. J Forensic Psychiatry. 1995;6:277–84. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molnar G, Pinchoff DM. Factors in patient elopements from an urban state hospital and strategies for prevention. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:791–2. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.8.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasena R, Miller WC. Discharges AMA and AWOL: A new “revolving door syndrome”. Psychiatr J Univ Ott. 1988;13:154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleis LS, Stout CE. The high-risk patient: A profile of acute care psychiatric patients who leave without discharge. Psychiatr Hosp. 1991;22:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falkowski J, Watts V, Falkowski W, Dean T. Patients leaving hospital without the knowledge or permission of staff–absconding. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:488–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange P. Elopement from the open psychiatric unit: A two-year study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1967;144:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore E. A descriptive analysis of incidents of absconding and escape from the English high-security hospitals, 1989–94. J Forensic Psychiatry. 2000;11:344–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowers L, Jarrett M, Clark N, Kiyimba F, McFarlane L. Determinants of absconding by patients on acute psychiatric wards. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:644–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lal N, Sethi BB, Manchandra R, SinhaPK A study of personality and related factors in absconders in a psychiatric hosptial. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:51–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.John CJ, Gangadhar BN, Channabasavanna SM. Phenomenology of “escape” from a mental hospital in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:247–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangadhar B, John C, Channabasavanna S. Factors influencing early return of escapees from a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1981;27:317–20. doi: 10.1177/002076408102700417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mubarak Ali R, Shekar K, Kazi A, Kavitha MA, Shariff IA. Escape from a Mental Hospital-Comparison of Escaped Patients during 1977 and 1987. Nimhans J. 1989;7:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khisty N, Raval N, Dhadphale M, Kale K, Javadekar A. A prospective study of patients absconding from a general hospital psychiatry unit in a developing country. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:458–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner W, Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Monahan J, Eisenberg MM, Bennett NS, et al. Patients’ revisions of their beliefs about the need for hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1385–91. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowda GS, Noorthoorn EO, Kumar CN, Nanjegowda RB, Math SB. Clinical correlates and predictors of perceived coercion among psychiatric inpatients: A prospective pilot study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;22:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gowda GS, Kondapuram N, Kumar CN, Math SB. Involuntary admission and treatment experiences of persons with schizophrenia: Implication for the Mental Health Care Bill 2016. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolan M, Snowden P. Escapes from a medium secure unit. J Forensic Psychiatry. 1994;5:275–86. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomison AR. Characteristics of psychiatric hospital absconders. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:368–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raynes AE, Patch VD. Distinguishing features of patients who discharge themselves from psychiatric ward. Compr Psychiatry. 1971;12:473–9. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(71)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nussbaum D, Lang M, Chan B, Riviere R. Characterization of elopers during remand: Can they be predicted? The METFORS experience. Am J Forensic Psychol. 1994;12:17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickens GL, Campbell J. Absconding of patients from an independent UK psychiatric hospital: a 3-year retrospective analysis of events and characteristics of absconders. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:543–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gowda GS, Lepping P, Noorthoorn EO, Ali SF, Kumar CN, Raveesh BN, et al. Restraint prevalence and perceived coercion among psychiatric inpatients from South India: A prospective study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;36:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molnar G, Keitner L, Swindall L. Medicolegal Problems of Elopement from Psychiatric Units. J Forensic Sci. 1985;30:10963J. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meehan T, Morrison P, McDougall S. Absconding behaviour: An exploratory investigation in an acute inpatient unit. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:533–7. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kernodle RW. Nonmedical leaves from a mental hospital. Psychiatry. 1966;29:25–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowers L, Jarrett M, Clark N, Kiyimba F, McFarlane L. Absconding: Why patients leave. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 1999;6:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.1999.630199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner G. The absconder. Compr Psychiatry. 1966;7:147–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Mental Health Care Act, 2017 – Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Department, Govt. of India. [Last accessed on 2018 Apr 28]. Retrieved from: http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental%20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .