Abstract

It is well established that inflammation leads to the creation of potent DNA damaging chemicals, including reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Nitric oxide can react with glutathione to create S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), which can in turn lead to S-nitrosated proteins. Of particular interest is the impact of GSNO on the function of DNA repair enzymes. The base excision repair (BER) pathway can be initiated by the alkyl-adenine DNA glycosylase (AAG), a monofunctional glycosylase that removes methylated bases. After base removal, an abasic site is formed, which then gets cleaved by AP endonuclease and processed by downstream BER enzymes. Interestingly, using the Fluorescence-based Multiplexed Host Cell Reactivation Assay (FM-HCR), we show that GSNO actually enhances AAG activity, which is consistent with the literature. This raised the possibility that there might be imbalanced BER when cells are challenged with a methylating agent. To further explore this possibility, we confirmed that GSNO can cause AP endonuclease to translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, which might further exacerbate imbalanced BER by increasing the levels of AP sites. Analysis of abasic sites indeed shows GSNO induces an increase in the level of AP sites. Furthermore, analysis of DNA damage using the CometChip (a higher throughput version of the comet assay) shows an increase in the levels of BER intermediates. Finally, we found that GSNO exposure is associated with an increase in methylation-induced cytotoxicity. Taken together, these studies support a model wherein GSNO increases BER initiation while processing of AP sites is decreased, leading to a toxic increase in BER intermediates. This model is also supported by additional studies performed in our laboratory showing that inflammation in vivo leads to increased large-scale sequence rearrangements. Taken together, this work provides new evidence that inflammatory chemicals can drive cytotoxicity and mutagenesis via BER imbalance.

Keywords: S-Nitrosation, Base excision repair, DNA alkylation, AAG, GSNO

1. Introduction

DNA is under constant attack from exogenous agents (e.g., UV irradiation and smoking) and endogenous agents (e.g., reactive oxygen species) that induce strand breaks, base lesions, and crosslinks. Unrepaired damage is associated with aging and can lead to mutations and cancer [1]. Alkylating agents are an important source of DNA damage and are found both endogenously, from methyl donors like S-adenosylmethionine, and exogenously, from chemicals including chemotherapeutics [2]. There are multiple pathways to repair alkylation-induced base lesions and strand breaks, and the primary pathway is the base excision repair (BER) pathway (Fig. 1A) [2,3]. Briefly, for alkylation damage, AAG excises damaged bases from the backbone, leaving behind an abasic site [2]. Subsequently, AP-endonuclease-1 (APE-1) cuts the backbone 5′ to the lesion, leaving a 5′-deoxyribophosphate (5′-dRP) and a 3′ hydroxyl group. Poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) binds to the stand break and is stimulated to add ADP-ribose chains to itself and other nuclear proteins. The polymerization subsequently helps to recruit downstream BER enzymes, including Polymerase β (POLβ), the scaffold protein XRCC1, and Ligase III. The lyase activity of POLβ next excises the 5′-dRP and adds a new base onto the 3′OH. Finally, Ligase I or the XRCC1-Ligase III complex seals the backbone [4,5]. Left unrepaired, each of these repair intermediates (Fig. 1A shown in the gray box) can be toxic to the cell [6–8]. Imbalances and deficiencies in the BER pathway have been implicated in many pathologies, including increased sensitivity to alkylating agents and vulnerability to inflammation [9–13].

Fig. 1.

BER and MGMT repair processes. (A) Simplified schematic of the Base Excision Repair pathway. The BER pathway is initiated by alkyladenine glycosylase (AAG), which excises the damaged base (black) leaving an abasic site. AP endonuclease-1 cleaves the phosphate-sugar backbone producing a 3′OH and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (5′-dRP). Polymerase β (POLβ) uses its dRPase activity to remove the dRP and inserts the correct base. Ligase 3 (LIG3) seals the backbone with XRCC1 acting as a scaffold. All repair intermediates shown in the gray box are detected through CometChip analysis. (B) Nitric oxide (red) can react with glutathione (GSH) to produce S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). (C) O6MeG methyltransferase (MGMT) repairs O6MeG by transferring the methyl lesion (blue) to its cysteine. (D) GSNO can transfer the nitric oxide moiety (red) to the active site cysteine of MGMT to form the inactive SNO-MGMT.

During inflammation, immune cells produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), which can damage the DNA [14,15]. In addition to damaging DNA, RONS can also affect proteins. Nitric oxide (NO) is generated by macrophages and epithelial cells under inflammatory conditions through the nitric oxide synthase [16], and can react with the cysteine residues of proteins through a process known as S-nitrosation [17]. One way in which proteins can become S-nitrosated is through the transfer of NO from S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), a nitrosated form of glutathione (Fig. 1B), to a cysteine residue on a protein [18]. S-nitrosated proteins have been found to have altered activities and modified cellular localizations when compared to their normal non-nitrosated forms [19].

One protein that is affected by S-nitrosation is the direct reversal DNA repair protein O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT), the primary repair mechanism for the toxic and mutagenic alkylated base lesion, O6-methylguanine (O6MeG). MGMT is a suicide protein such that transfer of a methyl group from the damaged base onto its active site cysteine renders it inactive (Fig. 1C) [20]. Importantly, GSNO can transfer its nitric oxide moiety onto the same cysteine of MGMT, inactivating it (Fig. 1D). The GSNO-induced inactivation of MGMT can lead to increased levels of mutation and cell death [21]. In addition, animals with an inability to reduce GSNO have lower levels of MGMT activity and increased tumor levels [22].

While the role of GSNO in the context of a direct reversal DNA repair protein is well studied, the effect of GSNO on the proteins in the BER pathway is less well understood. Previous reports have shown biochemically that nitrosation of AAG on cysteine 167, a residue in the active site of AAG, leads to increased excision of one of its substrates, 1, N6-ethenoadenine (ɛA) [23]. Mutation of cysteine 167 abrogates the increased AAG activity. While the exact mechanism by which nitrosated Cl67 induces increased AAG excision activity is unknown, previous researchers have speculated that it may reduce substrate specificity. Further along the BER pathway, studies show that S-nitrosation of APE-1 by GSNO on cysteines 93 and 310 leads to the export of APE-1 into the cytoplasm; accordingly, mutations of both cysteines eliminated APE-1′s export [24]. The report suggests that the nitrosation of the cysteines may induce a conformational change exposing a nuclear export sequence, however additional studies are necessary to substantiate this model. While these studies are mechanistically informative, analysis of the effect of S-nitrosation on the intact BER pathway in the context of the cell, and not just the individual proteins, had not been performed.

To study the effect of S-nitrosation on the BER pathway in cells, we utilize two recently developed techniques: the CometChip Assay [25] and the fluorescence-based multiplex host cell reactivation (FM-HCR) assay [26,27]. The CometChip assay is a high-throughput version of the comet assay, which is based on the principle that breaks in the DNA lead to a reduction in supercoiling and enables the DNA to migrate more readily through a matrix when electrophoresed [28–30]. By incubating damaged cells in culture media and lysing at various time points, one is able to analyze the kinetics of repair in the cells and determine if the cells have repaired the damage [25,31]. The CometChip is an improvement over former comet technologies due to its robustness and its optimized analysis platform [32]. The assay begins by loading cells onto an array of 40 µm diameter wells in agarose. The cells are subsequently lysed under alkaline conditions and electrophoresed. Thereafter, the DNA can be imaged and analyzed through the use of an epifluorescent microscope to determine the percentage of the nuclear DNA that is able to migrate away from the nucleus [32]. Migration is proportional to the levels of single strand breaks, abasic sites, and alkali labile sites. Relevant to these studies, toxic BER intermediates (gray box of Fig. 1A) are detectable using the comet assay.

While the CometChip allows the analysis of the BER pathway in aggregate, FM-HCR enables studies of the activities of specific DNA repair proteins [26,27]. The FM-HCR assay is based on the traditional host cell reactivation assay, which uses transcription inhibition to produce a phenotypic readout. The traditional host cell reactivation assay is rendered more powerful and specific through the use of site-specific DNA lesions in plasmids that impact expression of fluorescent marker genes. In some applications, such lesions inhibit expression of a reporter such as GFP, so that repair leads to increased fluorescence, which can be measured using flow cytometry. The system can be designed so that repair by a DNA glycosylase leads to suppression of fluorescence. For example, to query AAG activity, a plasmid is designed to harbor hypoxanthine (Hx), an important substrate of AAG [27]. While the damaged base is permissive to expression, the repaired sequence is mutated. Thus, by monitoring suppression of fluorescence, it is possible to learn the relative levels of repair. In addition, it is possible to analyze endonuclease activities based on transcription blocking [27]. Cells are transfected with tetrahydrofuran (THF), an abasic site analog, in a fluorescent reporter gene. THF blocks transcription of the gene, which inhibits fluorescent expression. However, upon repair initiated by an AP endonuclease, the gene can be transcribed and leads to expression of a fluorescent protein. In both assays, the level of fluorescent reporter expression can be analyzed through flow cytometry. In addition, FM-HCR allows the simultaneous analysis of multiple enzymes and pathways by using various pathway-specific lesions in fluorescent reporters of different colors. Together, the FM-HCR and CometChip assays allow the detection of BER kinetics and individual BER protein activities.

Here we investigate the effect of GSNO exposure on the repair of alkylation damage utilizing the CometChip and FM-HCR assays. We show that GSNO exposure induces an imbalance in the BER pathway by increasing AAG activity, while suppressing downstream protein activities. The increased level of BER intermediates is associated with decreased viability of cells following exposure to an alkylating agent. This study suggests a novel mechanism for nitric oxide induced toxicity in inflammatory environments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and cell culture

Wild type, Aag−/−, and AagTg mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFS) were prepared from respective mice [10,11] and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals). The wild type and Aag−/−MEFs were previously described [33]. They were previously immortalized by viral infection with a large T-antigen-expressing vector. The AagTg MEFs were prepared from previously described Aag-transgenic mouse embryos [34]. Briefly, the transgenic mice were created through pronuclear injection of a transgene containing Aag cDNA. The transgene was under the control of the enhancer from the CMV early promoter and the promoter from the chicken β-actin gene. To eliminate wildtype AAG activity, the transgenic mouse was bred to an Aag−/− background. The MEFs were immortalized by transfecting with a pSV3-neo plasmid expressing large T-antigen.

2.2. GSNO preparation

S-nitrosoglutathione was prepared as described previously [24,35]. Briefly, 0.1 M glutathione in 0.1 M HCl was incubated with 0.1 M sodium nitrite at 4 °C for 45 min. The resulting solution was neutralized to pH 7.4 with sodium hydroxide. The concentration of GSNO was measured spectrophotometrically (ɛ335 = 902 cm−1M−1). GSNO was prepared fresh for each experiment.

2.3. CometChip assay

The CometChip experimental setup has been described previously [25,31,32]. Briefly, MEFs were trypsinized and cultured overnight in 24 well plates with 100,000 cells/well in complete growth media at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Triplicate wells were seeded for each condition. The next day, cells were incubated with various concentrations of freshly prepared GSNO in growth media for four hours at 37 °C. Cells were subsequently incubated with 0, 0.5, or 1 mM MMS for 30 min at 37 °C in media containing the appropriate concentration of GSNO. Following MMS exposure, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in media containing the indicated concentration of GSNO for 0, 30, or 60 min. At the aforementioned times, cells were trypsinized and added to the CometChip [25] and allowed to settle by gravity in growth media at 37 °C. Cells not treated with MMS were trypsinized and loaded onto the CometChip at the 0 min time point. The cells embedded in the CometChip were then lysed overnight at 4 °C in standard alkaline lysis solution. The CometChip was subsequently processed and analyzed under alkaline conditions as described previously [36]. All data represents at least three independent biological replicates derived from independent cultures. In total, ~ 900 comets were analyzed per condition.

2.4. Fluorescence multiplexed host cell reactivation assay

The host cell reactivation assay has been described in detail previously [26,27]. Briefly, cells seeded at a concentration of 100,000 cells/well in 12 well plates were incubated overnight and subsequently exposed to the indicated concentrations of GSNO for 3 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, Lipofectamine LTX (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to transfect the cells with 2.5 µg of total plasmid DNA. DNA cocktails included undamaged reporter plasmids containing a gene encoding a blue fluorescent protein and plasmids containing site-specific DNA damage encoding green fluorescent protein, which were generated as previously described [26,27]. Transfected cells were incubated in the indicated concentrations of GSNO for 5 additional hours at 37 °C 5% CO2. Subsequently, the GSNO solutions were replaced with fresh growth media for 13 h. Cells were then trypsinized and resuspended in growth media containing the dead cell stain TO-PRO-3 and transferred to 75 mm Falcon tubes with cell strainer caps (ThermoFisher Scientific). Flow cytometry analysis and the calculation of percent fluorescent reporter expression was performed as previously described [26,27]. Four independent biological replicates from independent cultures were performed for each condition.

2.5. Immunofluorescent staining

Cells seeded the previous day in 24 well plates at a concentration of 100,000 cells/well were incubated with the indicated concentrations of GSNO for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with 1:100 primary rabbit anit-APE-1 (Novus Biologicals) overnight at 4 °C. Stained cells were incubated with a secondary Goat anti-Rabbit AlexaFluor 488 antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific) and mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade containing DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific). At least five images were taken per concentration in a blinded fashion using ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics). To quantify cells with APE-1 in the cytoplasm, images were blinded and counted manually for DAPI-positive nuclei. At least 100 cells were counted for each condition. Cells showing green fluorescence outside the nucleus were considered positive for cytoplasmic APE-1. Four independent biological replicates from independent cultures were performed for each condition.

2.6. Abasic site quantification

Cells seeded the previous day in 6 well plates at a concentration of 1 million cells/well were incubated with the indicated concentrations of GSNO for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cells were subsequently incubated with 0 or 1 mM MMS for 30 min at 37 °C in media containing the appropriate concentration of GSNO. Following MMS exposure, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in media containing the indicated concentration of GSNO for 0 or 60 min. Cells were then trypsinized and the DNA was extracted using the Purelink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Abasic sites were quantified through the DNA Damage Quantification Kit – AP Site Counting (Dojindo Molecular Technologies).

2.7. Colony forming assay

Fifteen hours after cells were seeded in duplicate 60 mm plates (in serial 10-fold dilutions), cells were incubated 0, 0.25, or 0.5 mM of freshly prepared GSNO in growth media for four hours at 37 °C. Cells were subsequently incubated with 0 or 1 mM MMS for one hour at 37 °C in media containing the appropriate concentration of GSNO. Following MMS exposure, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in media containing the indicated concentration of GSNO for four additional hours. GSNO-containing media was exchanged for standard growth media and cells were allowed to grow for 13 days to form colonies. After washing plates with PBS and allowing the plates to dry overnight, cells were stained with 1% crystal violet solution. Colonies were counted by eye in a blinded fashion. To analyze, the average number of colonies formed under each condition was divided by the initial seeding number. The data represent the surviving fractions of the MMS-challenged cells at each GSNO concentration relative to their GSNO-exposed controls. The data represents three independent experiments from independent cultures.

2.8. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism was used for all unpaired and paired Student’s t-tests.

3. Results

3.1. GSNO leads to increased BER intermediates following MMS exposure

To analyze whether GSNO exposure alters the activity of the BER pathway, we utilized the CometChip [25]. The CometChip is a high-throughput version of the comet assay that (under alkaline conditions) allows the detection of abasic sites, single strand breaks, and alkali sensitive sites. Since the comet assay detects single strand breaks and AP sites, using this approach, it is possible to monitor the levels of toxic BER intermediates formed and cleared during the repair of alkylation damage (Fig. 1A). If GSNO exposure increases or decreases BER protein activities, then one would expect a change in the formation and clearance of BER intermediates. To study these repair intermediates, we incubated wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (WT MEFs) with GSNO for four hours (based on previous studies [24]) before exposing the cells to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), an alkylating agent known to produce lesions such as 3-methyladenine and 7-methylguanine, that can be repaired by AAG-initiated BER [2]. Following MMS challenge, GSNO-exposed cells were allowed to repair methylated bases over time.

Control WT mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) exposed to 0 mM GSNO (Fig. 2A, white bars) have low percent tail values indicating low levels of strand breaks. After MMS challenge, the levels of strand breaks in the 0 mM GSNO cells appears to increase slightly relative to untreated controls at time 0. After incubating cells in media following MMS challenge, the levels of strand breaks, i.e., BER intermediates (white bars), trend lower over the course of 60 min, suggesting that DNA damage is being resolved, although the trend is not statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

GSNO exposure induces an increase in repair intermediates in MMS challenged cells. (A and B) CometChip analysis of WT MEFs exposed to GSNO and 0.5 mM MMS (A) and 0 mM MMS (B). Not treated MEF data (NT) in (A) is the same as the zero minute repair in (B). Each data point represents mean ± SEM for three independent experiments; *p < 0.05 for paired Student’s t-test.

The MEFs exposed to 0.25 and 0.5 mM GSNO (Fig. 2A, grey and black bars, respectively) display higher BER intermediate levels when compared to 0 mM GSNO MEFs. There appears to be a trend such that increased GSNO leads to increased repair intermediates. At 30 and 60 min after MMS challenge, both concentrations of GSNO displayed a statistically significant increase in the amount of BER intermediates when compared to the 0 mM GSNO MEFs (Fig. 2A). The GSNO-exposed MEFs did not show significant repair of the BER intermediates over the 60-min time window, which is consistent with a persistent BER imbalance caused by increased AAG activity and decreased APE-1 activity (described below). In addition, MEFs unchallenged by MMS and only exposed to various concentrations of GSNO (Fig. 2B) show similar percent tail values, indicating that GSNO on its own does not cause an increase in BER intermediates. Given that CometChip detects BER intermediates, and that GSNO exposure does not alter the basal level of BER intermediates, together these data suggest that GSNO renders cells susceptible to an increase in MMS-induced BER intermediates.

3.2. GSNO exposure increases AAG activity

Given the increase in levels of BER intermediates in GSNO-exposed cells, we set out to investigate the effect of GSNO exposure on individual proteins in the BER pathway. Previous studies performed biochemically have shown that nitrosation of the cysteine residues in AAG increases its excision activity in vitro [23]. Here, we set out to extend upon this work to test whether a similar effect could be observed in vivo in cells exposed to GSNO.

To analyze AAG activity, we used the FM-HCR assay [26,27,37]. Cells were exposed to three concentrations of GSNO and subsequently transfected with a plasmid containing hypoxanthine in the transcribed strand of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and an undamaged plasmid that expresses the blue fluorescent protein (BFP) to control for transfection efficiency. Hypoxanthine is a DNA lesion that is primarily excised by AAG [11,38]. The assay is based on the principle that if hypoxanthine is not excised by AAG, then during transcription, RNA polymerase can misread the Hx and incorrectly place cytosine across from the hypoxanthine (Fig. 3A – top panel) [39]. In this assay, the transcript of the EGFP gene can only lead to the production of EGFP if cytosine is incorporated opposite hypoxanthine during transcription. However, if hypoxanthine is excised by AAG, an abasic site will remain across from T. During BER repair synthesis, an A will be inserted in the transcribed strand across from T, in place of the Hx. Once A is in the transcribed strand, transcripts encode a non-fluorescent mutant of EGFP, and fluorescence is inactivated. Thus, the green fluorescent signal is inversely correlated with AAG activity. In these experiments, all GFP values were normalized to the undamaged control BFP fluorescent plasmid co-transfected in the cells. Repair of Hx was calculated by dividing the normalized GFP value measured in cells transfected with the Hx-containing reporter by the normalized GFP value measured in cells transfected with the undamaged GFP reporter.

Fig. 3.

GSNO exposure induces increased AAG activity. (A) Simplified schematic of the hypoxanthine reporter (Hx) of the FM-HCR assay. Cells transfected with the Hx reporter will display high fluorescence if RNA polymerase incorrectly inserts a cytosine in the transcript (top). If the Hx is repaired/cleaved, cells will not fluoresce (bottom). (B) Hx reporter assay tested in WT MEFs, Aag−/− MEFs, and constitutively active Aag, AagTg MEFs. (C and D) Hx Reporter assay tested in WT (C) and AagTg (D) MEFs exposed to GSNO. Each data point represents mean ± SEM for three independent experiments; *p < 0.05 for paired Student’s t-test.

The basal levels of AAG activity in MEFs isolated from mice with normal AAG activity (WT MEFs), AAG deficiency (Aag−/− MEFs) [11], and increased AAG activity (AagTg MEFs) were analyzed through the FM-HCR assay (Fig. 3B). The AagTg MEFs were generated from transgenic mice, which express Aag cDNA from an ubiquitous promoter [10]. The AagTg mice have previously been found to have between a 2 and 9 fold increase in AAG activity across all tissues analyzed [34]. As expected, MEFs deficient in Aag display increased levels of green fluorescence compared to WT, consistent with Aag−/− MEFs having reduced AAG activity and reduced ability to excise hypoxanthine lesions compared to WT [11,27]. Conversely, AagTg MEFs have a small, but statistically significant, decrease in fluorescence compared to WT MEFs, indicating higher AAG activity. Therefore, the fluorescent signal varies with AAG activity in FM-HCR, wherein lower levels of fluorescence indicate higher AAG activity.

The effects of GSNO exposure on AAG activity in WT MEFs were also analyzed through FM-HCR (Fig. 3C). Cells exposed to 0.25 and 0.5 mM GSNO displayed significantly lower green fluorescence compared to cells not exposed to GSNO. Cells exposed to 0.5 mM GSNO have ~ 50% of the fluorescence of the 0 mM GSNO MEFs. Given that FM-HCR fluorescence and AAG activity are inversely correlated, this result indicates that reduced fluorescence in the GSNO-exposed cells is due to increased AAG activity. Taken together, GSNO exposure increases AAG activity in cells, which is consistent with prior biochemical studies [23].

In addition to studies of cells with WT levels of AAG, we also analyzed the effects of GSNO on AAG activity in AagTg MEFs (Fig. 3D). AagTg MEFs showed no significant change in fluorescence and thus no change in AAG activity at any concentration of GSNO, suggesting that in cells with higher levels of AAG expression, GSNO exposure has no effect on AAG activity. These results suggest that GSNO exposure increases the activity of AAG, however GSNO’s effect is masked in the context of cells with high levels of AAG expression.

3.3. CometChip analysis shows that GSNO exposure does not alter BER kinetics in Aag−/− cells

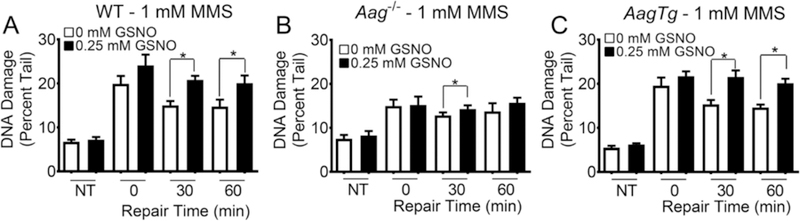

To study the effects of GSNO in cells with altered BER capacity, we also performed the CometChip analysis on WT, Aag−/−, and AagTg MEFs exposed to GSNO and MMS (Fig. 4). Through CometChip analysis, we can ascertain the role of AAG in the production of BER intermediates under nitrosating conditions. WT MEFs solely challenged with 1 mM MMS, have a significantly higher amount of BER intermediates compared to untreated controls at 0min after challenge (Fig. 4A, white bars). There appears to be a trend toward decreased BER intermediate levels consistent with repair over time (p = .058). MEFs exposed to 0.25 mM GSNO (Fig. 4A, black bars) display a significant increase in BER intermediates at time 0 compared to cells that were not exposed to MMS. At 30 and 60 min after challenge with 1 mM MMS there remains a significant increase in BER intermediates when compared to the control MEFs exposed to OmM GSNO. The increase in BER intermediates in the GSNO exposed and MMS challenged cells is consistent with results from Fig. 3C, showing increased AAG activity following GSNO exposure. For the Aag−/− cells, we observed an increase in repair intermediates following MMS challenge. This observation indicates that some of the MMS-induced repair intermediates are AAG-independent, possibly resulting from depurination of the dominant MMS-induced lesion, 7-methylguanine. Importantly, there was little difference between Aag−/− cells that were exposed to GSNO and those that were not exposed (Fig. 4B), which is consistent with GSNO’s effect being dependent on AAG.

Fig. 4.

GSNO exposed Aag−/− MEFs display minimal increase MMS-induced BER intermediates. CometChip analysis of WT (A), Aag−/− (B), and AagTg (C) MEFs exposed to 0 or 0.25 mM GSNO and challenged with 1 mM MMS. NT refers to cells not challenged with MMS, lysed at 0min. Each data point represents mean ± SEM for seven independent experiments; *p < 0.05 for paired Student’s t-test.

In addition, we analyzed the effect of GSNO and MMS exposure on AagTg MEFs (Fig. 4C) and observed a significant increase in repair intermediates 30 and 60 min after MMS challenge, similar to WT MEFs. As with the WT MEFs, we also observed a downward trend in intermediate levels suggestive of DNA repair in the MMS-challenged cells that were not exposed to GSNO, while there was virtually no decrease in BER intermediate levels when MMS-challenged cells were exposed to GSNO. The similarity between WT MEFs and AagTg MEFs may reflect a limit in sensitivity of the assay. Importantly, the observation that there are statistically significantly higher levels of BER intermediates in GSNO exposed WT and AagTg cells challenged with MMS is consistent with increased BER initiation (e.g., increased AAG activity; Fig. 3B), with a concomitant decrease in downstream BER activity (e.g., reduced APE-1 activity, as described below). Given that the hypoxanthine reporter assay in Fig. 3D indicated that GSNO exposure does not affect the activity of AAG in AagTg MEFs (which already have high levels of AAG), the similarity of the impact of GSNO between WT and AagTg results (compare Fig. 4A and C) is consistent with high levels of AAG masking the effect of GSNO.

3.4. GSNO exposure induces APE-1 translocation and increases abasic sites

Given the increased activity of AAG following GSNO exposure in WT MEFs, we investigated whether GSNO can affect the activity of downstream BER proteins. To that end, we utilized the FM-HCR assay with a plasmid containing tetrahydrofuran (THF) in the EGFP gene cassette (Fig. 5A) [27]. THF is an analog of AP sites (AP sites are created by AAG’s excision of base lesions), and APE-1 cleaves the abasic sites produced by AAG [40]. Subsequently, downstream BER proteins insert the correct base in the DNA and complete the repair process. In this assay, if the abasic site, which blocks transcription, is not repaired by APE-1 and downstream BER proteins, then EGFP protein will not be generated (Fig. 5A, top panel). However, if APE-1 and the downstream proteins repair the THF plasmid, then the EGFP gene can be fully transcribed and the cell will exhibit green fluorescence (Fig. 5A, bottom panel). Here, we found that WT MEFs exposed to GSNO showed a small but significant decrease in fluorescence, indicating a decrease in activity of BER proteins downstream of AAG (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

GSNO affects activity and localization of BER proteins and reduces cell viability after MMS challenge. (A) Simplified schematic of the tetrahydrofuran (THF) reporter of the FM-HCR assay. If unrepaired, THF will block transcription and inhibit fluorescence (top). If THF is fully repaired, cells will display higher fluorescence (bottom). (B) THF reporter assay in WT MEFs exposed to GSNO. (C) Representative immunofluorescent stains for APE-1 (yellow) and nuclei (Blue) of WT MEFs exposed to 0 mM (top) and 0.25 mM (bottom) GSNO. White box indicates inset image. Arrows indicate cells. (D) Blinded visual quantification of cells with APE-1 in the cytoplasm exposed to GSNO. (E) Abasic site analysis of GSNO exposed cells. NT = non-treated cells challenged with MMS and lysed at 0 min. Other bars show treatment with indicated concentrations of GSNO and 1 mM MMS. 60 min samples were allowed to repair abasic sites for 60 min at 37 °C in media with indicated GSNO concentration. Data is relative to NT. (F) Analysis of the colony forming assay of MEFs exposed to GSNO. Each bar represents the ratio of the surviving fraction of the MMS challenged cells to the non-MMS challenged cells at each GSNO concentration. Each data point represents mean ± SEM for three independent experiments; *p < 0.05 for paired Student’s t-test.

To further study additional causes of the observed increase in BER intermediates in GSNO-exposed cells, we analyzed the localization of APE-1. Previous studies have shown that S-nitrosation of APE-1 induces its export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in human kidney cells [24]. In analogous studies, we show a similar increase in cytoplasmic APE-1 after GSNO exposure in WT MEFs (Fig. 5C). Specifically, GSNO exposure induced a greater than 50% increase in the number of cells with cytoplasmic APE-1 (Fig. 5D).

Studies have shown that cells with reduced APE-1 activity display an accumulation of abasic sites [6]. To further test whether GSNO exposure diminishes APE-1 activity and increases the levels of abasic sites in the DNA, we quantified abasic sites in GSNO-exposed WT MEFs. The abasic sites were detected by incubating the DNA of the GSNO and MMS exposed cells with an aldehyde-reactive probe. This probe can be colorimetrically detected and quantified [41]. Cells exposed to MMS treatment alone did not show a significant increase in abasic sites, presumably because they are being rapidly processed by APE-1. However, we did observe a significant increase in absorbance, indicating an increase in abasic sites, in GSNO-exposed cells immediately after MMS challenge (Fig. 5E). However, after an hour: of repair in media containing GSNO, there was an insignificant difference in the levels of abasic sites between the unexposed and GSNO-exposed cells. These results show that GSNO exposure reduces APE-1 activity, however the generated abasic sites are still ultimately being repaired.

High levels of unrepaired BER intermediates and strand breaks have been observed to be toxic to cells [7,13]. Here, we tested whether GSNO-exposed cells display reduced cell viability compared to non-GSNO exposed cells following MMS challenge. WT MEFs were incubated with media containing various concentrations of GSNO and subsequently challenged with either 0 or 1 mM MMS. After incubating in media containing the indicated concentrations of GSNO for four hours, the cells were allowed to grow for 13 days. The surviving fraction for each GSNO concentration was calculated by dividing the surviving fraction of cells challenged with 1 mM MMS by the surviving fraction of cells not challenged with MMS at that GSNO concentration. MMS challenge induced a significantly lower level of cell viability in GSNO-exposed WT MEFs compared to non-GSNO exposed MEFs (Fig. 5F). This effect was observed at both 0.25 and 0.5 mM concentrations of GSNO. Therefore, GSNO exposure can reduce the viability of WT cells following MMS challenge.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1. Discussion

Inflammation is a key risk factor for cancer, contributing to upwards of 25% of cancer cases. During inflammation, tissue becomes infiltrated by immune cells that secrete cytokines and RONS [42,43]. RONS can damage DNA, leading to mutations that promote cancer [14,44,45]. Understanding the underlying molecular processes that drive carcinogenesis is key to cancer prevention. Here, we have explored the impact that NO has on DNA damage and repair following reaction with glutathione. While the effect of S-nitrosation, the process by which nitric oxide reacts with cysteine residues on proteins, has been studied in the context of some DNA repair proteins, the impact of S-nitrosation on the repair of alkylation lesions was not fully understood. Here, we analyzed in MEFs the capacity of the BER pathway to repair alkylation damage under nitrosating conditions. Exposure to GSNO, a metabolite that can induce S-nitrosation, was observed to modulate the activities of AAG and downstream BER proteins and induce an increase in BER intermediates in cells following alkylation damage. Furthermore, GSNO-exposed cells have reduced viability compared to unexposed cells following challenge with an alkylating agent. Taken together, results reveal that GSNO induces an imbalance in the BER pathway and suggest that this imbalance leads to increased alkylation-induced toxicity.

Previous, studies have shown that S-nitrosation can alter the activity of AAG [23] and the localization of APE-1 [24]. Analysis of the kinetics of BER through detection of BER intermediates (abasic sites and single strand breaks) demonstrates that S-nitrosation not only affects individual steps of the BER pathway, but it can alter the ability of the BER pathway as a whole to repair alkylation damage. Both GSNO exposed and unexposed cells have similarly high levels of BER intermediates immediately after MMS challenge. However, 30 and 60 min after MMS challenge, GSNO exposed cells display significantly higher amounts of BER intermediates compared to unexposed cells, consistent with increased formation of BER intermediates, or decreased clearance, or both. Thus, GSNO modifies the ability of cells to repair alkylation damage.

We hypothesized that the accumulation of BER repair intermediates in the WT MEFs exposed to GSNO could be caused by alteration in the activities of AAG and a key downstream enzyme, APE-1. Through the use of the FM-HCR assay, we observed that GSNO exposure increases the activity of AAG to excise hypoxanthine. Although hypoxanthine is not generated during MMS challenge, AAG is the main glycosylase for hypoxanthine, making this substrate for FM-HCR an excellent way to gauge overall AAG activity. Our observation of increased AAG activity following GSNO exposure is therefore relevant to MMS conditions due to the fact that AAG also has a high catalytic activity for key MMS-induced methyl lesions, including 3-methyladenine and 7-methylguanine [11,46]. Furthermore, our data concur with previous reports by the Wyatt Laboratory showing that S-nitrosated AAG has an increased ability to excise another AAG substrate, 1, N6-ethenoadenine [23]. Thus, the results from two independent assays analyzing the AAG excision activity on two different base lesions have both demonstrated that AAG has an increased ability to repair base lesions after GSNO exposure.

To further test the hypothesis that the increase in BER intermediates in GSNO-exposed cells is influenced by increased AAG activity, we used the CometChip to analyze BER intermediates in cells with altered AAG activity. We found that MMS-induced BER intermediates are increased in GSNO-exposed cells, which is consistent with an increase in AAG activity. GSNO exposure had a minimal effect on the ability of Aag−/− cells to repair alkylation damage, suggesting that GSNO requires AAG to affect BER capacity. Furthermore, GSNO-exposed AagTg cells showed similar MMS repair kinetics as the GSNO-exposed WT cells, possibly because cells were already saturated with AAG activity, making the ability of GSNO to increase AAG activity irrelevant. While these results support AAG as the driver for increased BER intermediates, it remains possible that downstream BER proteins also contribute.

An alternative approach to analyze the effects of GSNO exposure on proteins downstream of AAG is FM-HCR. To perform this assay, we transfected GSNO-exposed cells with plasmids containing an abasic site analog (tetrahydrofuran) in the EGFP cassette. The THF plasmid requires APE-1 to cleave the abasic site and for downstream intermediates to be completely resolved in order for the EGFP protein to be expressed. In our system, we observed a significant decrease in the reporter expression in GSNO-exposed cells, indicating a decrease in the activity of APE-1 and/or downstream enzymes remaining in the BER pathway. The observed decrease in activity is perhaps due to the effects of S-nitrosation on multiple proteins. For example, previous studies have shown that ligases can be inactivated by nitric oxide, suggesting that Ligase I or III may have reduced activity in a GSNO environment [47]. In addition, studies on PARP-1 have shown that S-nitrosation reduces its activity [48]. While, to our knowledge, there have not been studies on the effects of S-nitrosation on other BER proteins such as XRCC1 and POLβ, there is a possibility that these proteins might be degraded, translocated, or inactivated by S-nitrosation. The results of THF reporter assay suggest that in aggregate, the BER proteins downstream of AAG have reduced activity following GSNO exposure.

Here, we extended previous studies of hepatocytes and kidney cells [24] to analyze the localization and activity of APE-1 following GSNO exposure in MEFs. We observed an increase in the percentage of cells with APE-1 protein in the cytoplasm following GSNO exposure. Previous studies analyzing the effects of GSNO on APE-1 have shown that GSNO exposure can induce site-specific S-nitrosation of APE-1 and causes the protein to be exported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm [24]. The concentration of GSNO used and the methodology of GSNO exposure in the published studies are similar to those methodologies presented here. Together, these results provide strong support for a model wherein APE-1 is S-nitrosated and S-nitrosation induces a significant percentage of APE-1 protein to translocate into the cytoplasm. While the exact mechanism by which S-nitrosation causes APE-1 export is unknown, current models suggest that the nitrosation causes a conformational change that exposes a nuclear export sequence [24].

If the GSNO-induced export of APE-1 had affected its ability to cleave abasic sites, one would predict the level of abasic sites would increase. Here, we indeed detected an increase in abasic sites in GSNO-exposed cells immediately after MMS challenge suggesting an initial imbalance in AAG and APE-1 activities. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that Aag deficiency in animals causes susceptibility to colon cancer [9,49]. Since AAG substrates can be cytotoxic and mutagenic (e.g., εA), it may be that either too much or too little AAG puts the genome at risk, and that outcome can be dependent on combined effects, such as co-exposure to inflammation and alkylation damage.

Taken together, the aforementioned results suggest that GSNO exposure induces inverse effects on BER proteins. While increasing the excision activity of AAG, S-nitrosation also reduces the activity of downstream BER proteins, resulting in a BER imbalance and an accumulation of repair intermediates. Previous studies have shown that BER imbalances are toxic to cells and tissues [6,9,10,13,50]. Here, we have revealed that GSNO exposure causes increased toxicity in cells challenged with MMS compared to unexposed cells, suggesting that the BER imbalance and the accompanying increase in BER intermediates contributes to the toxicity in the cell.

4.2. Conclusions

The observations that GSNO exposure alters the activities of BER proteins leading to an increase in repair intermediates and reduced cell viability following MMS challenge, suggest that S-nitrosation reduces the cell’s ability to repair and survive alkylation-induced damage. Previous studies have shown that S-nitrosation can affect the activity of other glycosylases, such as Ogg1 [51], a bifunctional glycosylase that repairs oxidative lesions. Our work here suggests that additional proteins in the BER pathway are affected by S-nitrosation, leading to higher levels of intermediates. A key inflammatory chemical can alter BER activity, which in turn can cause increased susceptibility to alkylation damage. For people who have chronic inflammation, such as inflammatory bowel disease, co-exposure to alkylating agents is unavoidable, since alkylating agents are ubiquitous in the intracellular environment, in environmental pollutants, and in food. These insights into combined exposures contribute to our understanding of the key molecular processes that affect cancer risk.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the MIT Nitric Oxide Program Project Grant (National Cancer Institute Grant #P01-CA026731), the MIT Center for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS Grant P30-ES002109), and the Siebel Scholar Program. The CometChip technology is filed under Patent #9,194,841, and B.P.E. is a co-inventor.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Hoeijmakers JH, DNA damage, aging, and cancer, N. Engl. J. Med 361 (15) (2009) 1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD, Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents, Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (2) (2012) 104–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lindahl T, Wood RD, Quality control by DNA repair, Science 286 (5446) (1999) 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Prasad R, Shock DD, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Substrate channeling in mammalian base excision repair pathways: passing the baton, J. Biol. Chem 285 (52) (2010) 40479–40488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Calvo JA, Allocca M, Fake KR, Muthupalani S, Corrigan JJ, Bronson RT, et al. , Parpl protects against Aag-dependent alkylation-induced nephrotoxicity in a sex-dependent manner, Oncotarget 7 (29) (2016) 44950–44965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Glassner BJ, Rasmussen LJ, Najarian MT, Posnick LM, Samson LD, Generation of a strong mutator phenotype in yeast by imbalanced base excision repair, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95 (17) (1998) 9997–10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Luo M, Kelley MR, Inhibition of the human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1) repair activity and sensitization of breast cancer cells to DNA alkylating agents with lucanthone, Anticancer Res 24 (4) (2004) 2127–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sobol RW, Horton JK, Kuhn R, Gu H, Singhal RK, Prasad R, et al. , Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-beta in base-excision repair, Nature 379 (6561) (1996) 183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meira LB, Bugni JM, Green SL, Lee CW, Pang B, Borenshtein D, et al. , DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice, J. Clin. Invest 118 (7) (2008) 2516–2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Meira LB, Moroski-Erkul CA, Green SL, Calvo JA, Bronson RT, Shah D, et al. , Aag-initiated base excision repair drives alkylation-induced retinal degeneration in mice, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106 (3) (2009) 888–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Engelward BP, Weeda G, Wyatt MD, Broekhof JL, de Wit J, Donker I, et al. , Base excision repair deficient mice lacking the Aag alkyladenine DNA glycosylase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94 (24) (1997) 13087–13092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xiao W, Samson L, In vivo evidence for endogenous DNA alkylation damage as a source of spontaneous mutation in eukaryotic cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 90 (6)(1993) 2117–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Posnick LM, Samson LD, Imbalanced base excision repair increases spontaneous mutation and alkylation sensitivity in Escherichia coli, J. Bacteriol 181 (21) (1999) 6763–6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dedon PC, Tannenbaum SR, Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 423 (1) (2004) 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tamir S, Burney S, Tannenbaum SR, DNA damage by nitric oxide, Chem. Res. Toxicol 9 (5) (1996) 821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S, Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases, J. Biol. Chem 279 (35) (2004) 36167–36170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Keszler A, Zhang Y, Hogg N, Reaction between nitric oxide, glutathione, and oxygen in the presence and absence of protein: how are S-nitrosothiols formed? Free Radic. Biol. Med 48 (1) (2010) 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Que L, Heitman J, Stamler JS, A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans, Nature 410 (6827) (2001) 490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS, Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective, Trends Mol. Med 15 (9) (2009) 391–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pegg AE, Multifaceted roles of alkyltransferase and related proteins in DNA repair, DNA damage, resistance to chemotherapy, and research tools, Chem. Res. Toxicol 24 (5) (2011) 618–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu L, Xu-Welliver M, Kanugula S, Pegg AE, Inactivation and degradation of O (6)-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase after reaction with nitric oxide, Cancer Res 62 (11)(2002) 3037–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wei W, Li B, Hanes MA, Kakar S, Chen X, Liu L, S-nitrosylation from GSNOR [37] deficiency impairs DNA repair and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis, Sci. Transl. Med 2 (19) (2010) 19ra3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jones LE Jr., Ying L, Hofseth AB, Jelezcova E, Sobol RW, Ambs S, et al. , Differential effects of reactive nitrogen species on DNA base excision repair initiated by the alkyladenine DNA glycosylase, Carcinogenesis 30 (12) (2009) 2123–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qu J, Liu GH, Huang B, Chen C, Nitric oxide controls nuclear export of APE1/Ref-1 through S-nitrosation of cysteines 93 and 310, Nucleic Acids Res 35 (8) (2007) 2522–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wood DK, Weingeist DM, Bhatia SN, Engelward BP, Single cell trapping and DNA damage analysis using microwell arrays, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107 (22)(2010) 10008–10013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nagel ZD, Margulies CM, Chaim IA, McRee SK, Mazzucato P, Ahmad A, et al. , Multiplexed DNA repair assays for multiple lesions and multiple doses via transcription inhibition and transcriptional mutagenesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111 (18) (2014) El823–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chaim IA, Nagel ZD, Jordan JJ, Mazzucato P, Ngo LP, Samson LD, In vivo measurements of interindividual differences in DNA glycosylases and APE1 activities, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114 (48) (2017) E10379–E10388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Collins AR, The comet assay for DNA damage and repair: principles, applications, and limitations, Mol. Biotechnol 26 (3) (2004) 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Olive PL, Banath JP, Durand RE, Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the comet assay, Radiat. Res 122 (1) (1990) 86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ostling O, Johanson KJ, Microelectrophoretic study of radiation-induced DNA damages in individual mammalian cells, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 123 (1) (1984) 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Weingeist DM, Ge J, Wood DK, Mutamba JT, Huang Q, Rowland EA, et al. , Single-cell microarray enables high-throughput evaluation of DNA double-strand breaks and DNA repair inhibitors, ABBV Cell Cycle 12 (6) (2013) 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ge J, Chow DN, Fessler JL, Weingeist DM, Wood DK, Engelward BP, Micropattemed comet assay enables high throughput and sensitive DNA damage quantification, Mutagenesis 30 (1) (2015) 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chaim IA, Gardner A, Wu J, Iyama T, Wilson DM 3rd, Samson LD A novel role for transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair for the in vivo repair of 3,N4-ethenocytosine, Nucleic Acids Res 45 (6) (2017) 3242–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Calvo JA, Moroski-Erkul CA, Lake A, Eichinger LW, Shah D, Jhun I, et al. , Aag DNA glycosylase promotes alkylation-induced tissue damage mediated by Parpl, PLoS Genet 9 (4) (2013) el003413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].He J, Kang H, Yan F, Chen C, The endoplasmic reticulum-related events in S-nitrosoglutathione-induced neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule cells, Brain Res 1015 (1–2) (2004) 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ge J, Prasongtanakij S, Wood DK, Weingeist DM, Fessler J, Navasummrit P, et al. , CometChip: a high-throughput 96-well platform for measuring DNA damage in microarrayed human cells, J. Vis. Exp 92 (2014) e50607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nagel ZD, Chaim IA, Samson LD, Inter-individual variation in DNA repair capacity: a need for multi-pathway functional assays to promote translational DNA repair research, DNA Repair (Amst.) 19 (2014) 199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Saparbaev M, Laval J, Excision of hypoxanthine from DNA containing dIMP residues by the Escherichia coli, yeast, rat, and human alkylpurine DNA glycosylases, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91 (13) (1994) 5873–5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Morreall J, Kim A, Liu Y, Degtyareva N, Weiss B, Doetsch PW, Evidence for retromutagenesis as a mechanism for adaptive mutation in escherichia coli, PLoS Genet 11 (8) (2015) el005477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wilson DM 3rd, Barsky D, The major human abasic endonuclease: formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA, Mutat. Res 485 (4) (2001) 283–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nakamura J, Walker VE, Upton PB, Chiang SY, Kow YW, Swenberg JA, Highly sensitive apurinic/apyrimidinic site assay can detect spontaneous and chemically induced depurination under physiological conditions, Cancer Res 58 (2) (1998)222–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability, Carcinogenesis 30 (7) (2009) 1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC, Radical causes of cancer, Nat. Rev. Cancer 3 (4) (2003) 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mangerich A, Dedon PC, Fox JG, Tannenbaum SR, Wogan GN, Chemistry meets biology in colitis-associated carcinogenesis, Free Radic. Res 47 (11) (2013) 958–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hofseth LJ, Khan MA, Ambrose M, Nikolayeva O, Xu-Welliver M, Kartalou M, et al. , The adaptive imbalance in base excision-repair enzymes generates microsatellite instability in chronic inflammation, J. Clin. Invest 112 (12) (2003) 1887–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].O’Brien PJ, Ellenberger T, Dissecting the broad substrate specificity of human 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase, J. Biol. Chem 279 (11) (2004) 9750–9757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Graziewicz M, Wink DA, Laval F, Nitric oxide inhibits DNA ligase activity: potential mechanisms for NO-mediated DNA damage, Carcinogenesis 17 (11) (1996) 2501–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sidorkina O, Espey MG, Miranda KM, Wink DA, Laval J, Inhibition of poly (ADP-RIBOSE) polymerase (PARP) by nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen oxide species, Free Radic. Biol. Med 35 (11) (2003) 1431–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kiraly O, Gong G, Roytman MD, Yamada Y, Samson LD, Engelward BP, DNA glycosylase activity and cell proliferation are key factors in modulating homologous recombination in vivo, Carcinogenesis 35 (11) (2014) 2495–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Calvo JA, Meira LB, Lee CY, Moroski-Erkul CA, Abolhassani N, Taghizadeh K, et al. , DNA repair is indispensable for survival after acute inflammation, J. Clin. Invest 122 (7) (2012) 2680–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Nishioka N, Nakabeppu Y, Gores GJ, Human Oggl, a protein involved in the repair of 8-oxoguanine, is inhibited by nitric oxide, Cancer Res 61 (17) (2001) 6388–6393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]