Abstract

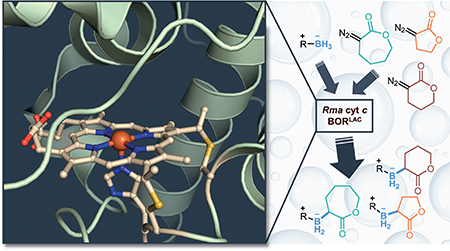

Previous work has demonstrated that variants of a heme protein, Rhodothermus marinus cytochrome c (Rma cyt c), catalyze abiological carbene boron–hydrogen (B–H) bond insertion with high efficiency and selectivity. Here we investigated this carbon–boron bondforming chemistry with cyclic, lactone-based carbenes. Using directed evolution, we obtained a Rma cyt c variant BORLAC that shows high selectivity and efficiency for B–H insertion of 5- and 6-membered lactone carbenes (up to 24,500 total turnovers and 97.1:2.9 enantiomeric ratio). The enzyme shows low activity with a 7-membered lactone carbene. Computational studies revealed a highly twisted geometry of the 7membered lactone carbene intermediate relative to 5- and 6-membered ones. Directed evolution of cytochrome c together with computational characterization of key iron-carbene intermediates has allowed us to expand the scope of enzymatic carbene B–H insertion to produce new lactone-based organoborons.

Keywords: cytochrome c, carbene, organoboron, lactones, biocatalyst, directed evolution

Graphical Abstract

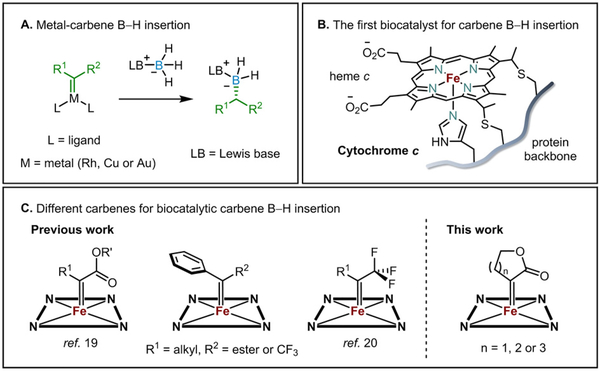

The significant role of organoboron chemistries1–3 in synthetic methodologies is exemplified by alkene hydroboration4,5 and Suzuki cross-coupling,6,7 whose enormous footprints in synthetic chemistry have been recognized by Nobel Prizes. In addition, organo-boronic acids or -borates8 can act as transition-state-analog inhibitors in biological systems and are useful functionalities in chemotherapeutics9 and other biologically active molecules.10 The broad applications of organoboron compounds have prompted chemists to develop efficient, selective and modular synthetic platforms for installing boron motifs onto carbon backbones. One major class of methods for forming carbon– boron (C–B) bonds relies on transition-metal-catalyzed B–H bond insertion of carbenes (Figure 1A),11–18 as introduced by Curran and co-workers. Recently, the Arnold laboratory developed the first biocatalytic system for this transformation using engineered variants of cytochrome c from the Gram-negative, thermohalophilic bacterium Rhodothermus marinus (Rma cyt c).19 The laboratory-evolved enzymes exhibited very high efficiency (up to 15,300 turnovers and 6,100 h−1 turnover frequency) and enantioselectivity (up to 99:1 enantiomeric ratio) with different carbenes and boranes (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A. Catalytic carbene B–H insertion. B. A hemeprotein biocatalyst for carbene B–H insertion based on Rma cytochrome c. C. Carbenes used for biocatalytic carbene B–H insertion

To expand the catalytic range of this enzymatic C–B bond-forming platform, we have engineered Rma cyt c to accept structurally different carbenes. In previous work, we typically used α-ester-substituted diazo compounds as carbene precursors,19 but we recently demonstrated that Rma cyt c mutants can be tuned to use a spectrum of α-trifluoromethyl-α-alkyl diazo compounds to furnish a wide array of chiral α-trifluoromethylated organoborons (Figure 1C).20 We were curious whether cyclic carbene moieties21 can also be used by Rma cyt c, despite significant structural differences compared to the acyclic carbenes used in previous work.19–26

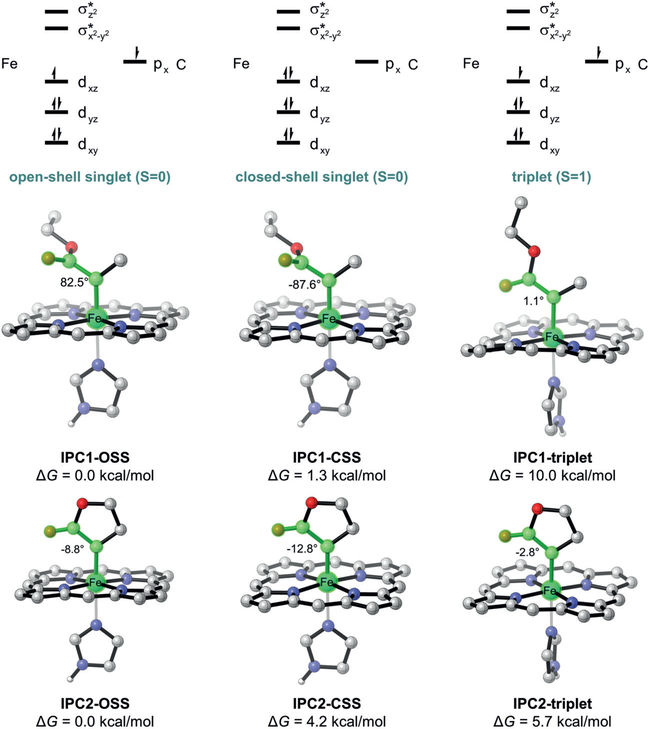

We started this investigation of cyclic carbenes using five-membered lactone diazo compound 1 (see Figure 3) as the carbene precursor. With such a rigid structure, the putative iron-porphyrin carbene (IPC) intermediate is expected to have different conformational properties and potentially distinct electronic features compared to acyclic carbenes, such as the one derived from α-methyl ethyl diazoacetate (Me-EDA). Recent work by our group revealed the crystal structure of the Me-EDA-derived IPC intermediate27 in a triple mutant of Rma cyt c (V75T M100D M103E (TDE)) evolved in the laboratory for Si–H bond insertion.26 Experiments indicated a singlet electronic state of this iron carbene species IPC1, which is in line with the computational result that open/closed-shell singlets are the dominant electronic states (Figure 2).

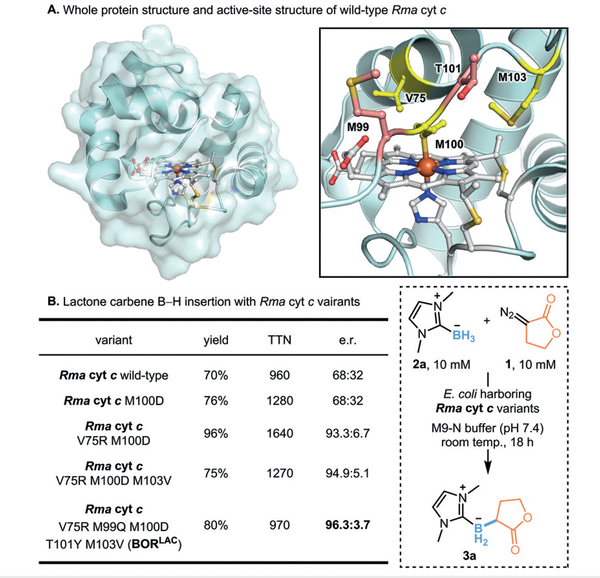

Figure 3.

A. Whole protein structure and active-site structure of wildtype Rma cyt c (PDB: 3CP5, ref. 31). B. Yields and e.r. values of selected Rma cyt c variants for B–H insertion. Reactions were conducted in quadruplicate: suspensions of E. coli expressing Rma cyt c variants (OD600 = 20), 10 mM borane 2a, 10 mM lactone diazo 1, and 5 vol% acetonitrile in M9-N buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature under anaerobic conditions for 18 hours. TTN refers to the molar ratio of total desired product, as quantified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) using trimethoxybenzene as internal standard, to total heme protein. Enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) was determined by chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

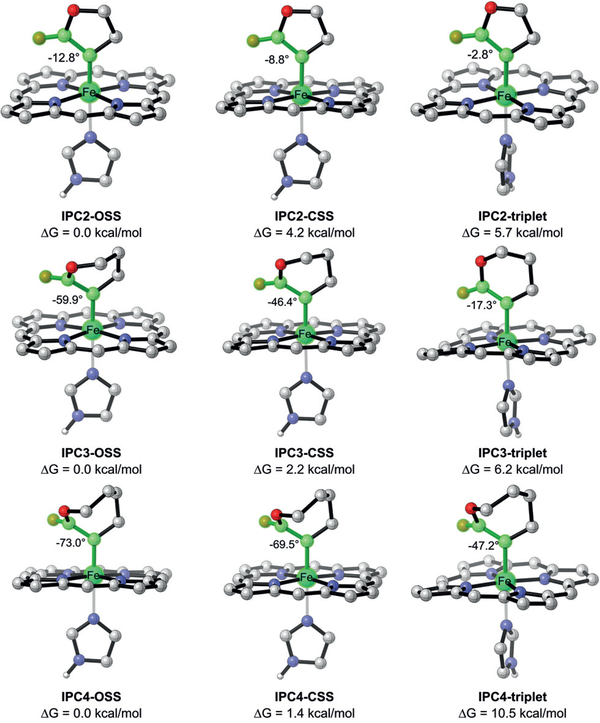

Figure 2.

Electronic states of acyclic IPC1 and cyclic IPC2 intermediates. The Gibbs free energies were obtained at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZ-VPP//B3LYP/def2-SVP level. OSS = open-shell singlet, CSS = closed-shell singlet

We used density functional theory (DFT) calculations to assess the electronic states of the lactone-based IPC2 (also using the simplified model of the protein IPC).21,27–30 As we expected, IPC2 features a near-planar geometry with a very small dihedral angle d(Fe-C-C-O) (<13°) in all electronic states, which is very different from the acyclic IPC1 with d(Fe-C-C-O) of nearly 90° in singlets. The small dihedral angle renders the singlet states less stable due to strong repulsion between fully occupied orbitals and thus significantly changes the energy levels of the electronic states of the IPC.

We wanted to know how the different structural and electronic properties of this intermediate affect carbene B–H insertion. We thus tested the borylation reaction using the five-membered lactone diazo compound 1 and an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-stabilized borane as substrates in the presence of whole E. coli bacteria expressing engineered variants of Rma cyt c, starting with those obtained during directed evolution for borylation with acyclic carbene precursors (e.g., Me-EDA) (Figure 3). We were pleasantly surprised to see that wild-type Rma cyt c exhibited high efficiency for lactone carbene B–H insertion, with 960 total turnovers (TTN) and 70% gas chromatography (GC) yield. The enantioselectivity, however, was poor, with only a 68:32 enantiomeric ratio (e.r.). A distal axial-ligand M100D mutation, previously discovered to facilitate both carbene Si–H and B–H insertion,19,26 improved the yield, but did not improve the enantiocontrol of this reaction. Residue V75 in an α-helix region was previously shown to affect carbene orientation.19,20 Screening of M100D variants containing mutations at V75 identified M100D V75R as the most selective, with 93.3:6.7 e.r., whereas V75T/C/K/P/G mutations resulted in poor to moderate enantioselectivities. An additional M103V mutation led to even more precise stereochemical control, giving an e.r. of 94.9:5.1 (Figure 3).

To increase the enantioselectivity of lactone-carbene B– H insertion, we subjected the Rma cyt c V75R M100D M103V (RDV) variant to site-saturation mutagenesis, targeting active-site amino acid residues which are close to the iron center in wild-type Rma cyt c (within 10 Å). It is known that the residues residing on the flexible front loop are important for controlling the structure of the heme pocket, which is presumably the active site for this novel function (Figure 3A).27 Consequently, introducing suitable mutations on this loop may help to orient the iron-carbene intermediate or tune the approach of the borane substrate and lead to desired enantioselectivity. A double-site-saturation mutagenesis library at residues M99 and T101 was cloned using the 22-codon-trick protocol32 and screened as whole-cell catalysts in four 96-well plates for improved borylation enantioselectivity. Double mutant M99Q T101Y (BORLAC) was identified to exhibit higher selectivity (96.3:3.7 e.r.) and good catalytic efficiency (970 TTN, 80% GC yield).

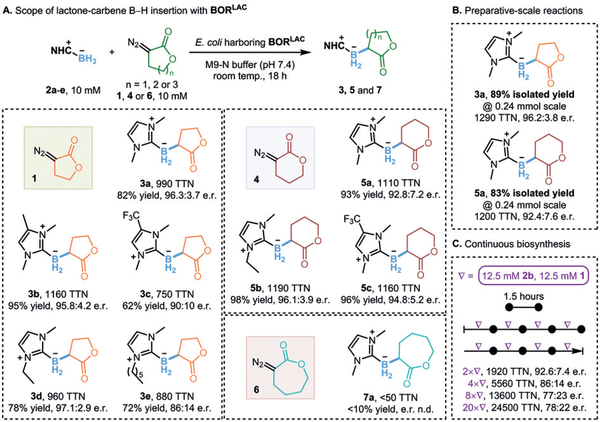

With an efficient and selective borylating variant BORLAC in hand, we then assessed the scope of boranes that this platform can use (Figure 4A). Boranes without stabilizing groups are highly reactive and unstable in aqueous conditions. Lewis bases, such as ethers, amines, phosphines and NHCs, are generally used as good stabilizing groups for free boranes.33 Considering the biocompatibility and cell permeability of the borane reagents, NHC-stabilized boranes turned out to be suitable candidates for this borylation platform.34 Indeed, borane complexes stabilized by NHCs featuring different electronic properties, steric hindrance and/or lipophilicity all served as good substrates for the target borylation reaction, furnishing the desired products with up to 1160 TTN and enantioselectivities up to 97.1:2.9 e.r. For instance, fluorine-containing alkyl groups (e.g., 2c), which are electron-withdrawing and usually exhibit very different lipophilicity and hydrophilicity relative to general aliphatic alkyl groups, were found to be compatible with the whole-cell reaction conditions.

Figure 4.

A. Scope of lactone-carbene B–H insertion with BORLAC. Reactions were conducted in quadruplicate: suspension of E. coli expressing Rma cyt c variant BORLAC (OD600 = 20), 10 mM borane 2, 10 mM lactone diazo 1, 4 or 6, and 5 vol% acetonitrile in M9-N buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature under anaerobic conditions for 18 hours. TTN refers to the total desired product, as quantified by GC-MS using trimethoxybenzene as internal standard, divided by total heme protein. Enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) was determined by chiral HPLC. B. Preparative-scale synthesis of organoborons. Reaction conditions: suspension of E. coli expressing Rma cyt c variant BORLAC (OD600 = 15), 12 mM borane 2a, 12 mM lactone diazo 1 or 4, 50 mM D-glucose and 6 vol% acetonitrile in M9-N buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature under anaerobic conditions for 18 hours. Reactions were set up in quadruplicate and organoboron products were isolated from the combined reaction replicates. C. Enzymatic synthesis of organoborons with portionwise addition of substrates. Reactions were conducted in duplicate using the same reaction conditions as in A. above, except for using 2.5 M solution stocks of borane 2b and lactone diazo 1 (one portion = 2 μL of each substrate stock)

To explore the longevity of the biocatalyst, we tried portionwise addition of the two substrates. Every 1.5 hours, we added an additional aliquot corresponding to 12.5 mM of each substrate to the reaction. Over 20 additions, we observed continuous and steadily increasing product formation, which indicates that the catalyst maintained function over 30 hours (Figure 4C). However, we did notice that enantioselectivities decreased. Covalent modification of the protein backbone by carbene species and non-covalent binding of borane substrate or product to the protein may cause structural changes that compromise stereocontrol.35 Further reaction engineering and optimization, such as using a flow system to maintain consistent concentrations of reagents, may be able to address this selectivity drop.

Given that the 5-membered cyclic lactone-carbene worked so well for this biocatalytic B–H insertion, we wondered whether other cyclic carbenes, particularly lactone-carbenes with different ring sizes, would also be accepted. The 6- and 7-membered lactone diazos 4 and 6 were readily prepared from the corresponding lactones and used as cyclic carbene precursors for testing B–H insertion using variant BORLAC (Figure 4A). The 6-membered lactone-carbene showed high reactivities (up to 1190 TTN and 96.1:3.9 e.r.) for the desired borylation with three different borane substrates. Additionally, enzymatic borylation with both 5- and 6-membered lactone carbenes was readily scalable to millimole level, affording the desired products in high isolated yields (Figure 4B). However, with one additional carbon in the ring, the 7-membered lactone-carbene behaved in a completely different manner: BORLAC exhibited only low activity with this carbene precursor (<50 TTN).

To understand the origins of this dramatic impact of ring size on Rma cyt c-catalyzed lactone-carbene B–H insertion chemistry, we employed DFT calculations to compare the structures and the electronic properties of three lactonetype IPCs. Unlike 5-membered lactone-based IPC2, which takes on a rigid planar structure, 6-membered lactone-carbene IPC3 showed a slightly flexible structure with a dihedral angle d(Fe-C-C-O) of 60° in the ground OSS state, while its triplet state still possesses a near-planar geometry (Figure 5). However, 7-membered lactone IPC4 takes on highly twisted conformations with d(Fe-C-C-O) from 47° to 73° in all electronic states.36 It is apparent that none of the electronic states in IPC4 shares a similar structure with IPC2. This may explain why BORLAC, which was evolved for the 5membered lactone carbene, did not exhibit high reactivity towards borylation with the 7-membered lactone carbene. But this does not necessarily mean that Rma cyt c cannot be engineered to accommodate the 7-membered lactone carbene for B–H insertion; further engineering using BORLAC as a starting template could well lead to variants with improved reactivity on this 7-membered lactone carbene.

Figure 5.

Comparison of 5-, 6- and 7-membered lactone-based IPCs. The Gibbs free energies were obtained at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZ-VPP//B3LYP/def2-SVP level

In conclusion, we have expanded the scope of carbenes for biocatalytic B–H insertion chemistry to include cyclic lactone carbenes.37 With further development of Rma cyt c based biocatalytic platforms, we accessed a range of organoborons at preparative scales and with unprecedented catalytic efficiencies (up to 24,500 TTN) and high enantioselectivities (up to 97.1:2.9 e.r.). Computational studies provided insights into the conformations and electronic states of cyclic carbene intermediates with different ring sizes. This mechanistic understanding together with the new biocatalyst variants identified should promote further expansion of carbene scope for borylation and other carbine-transfer reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

A.Z.Z. thanks the Caltech SURF program. Calculations were performed on the high-performance computing system at the Department of Chemistry, Zhejiang University. We thank R. D. Lewis and R. K. Zhang for helpful discussions and comments. We also thank the Caltech Mass Spectrometry Laboratory.

Funding Information

Financial support from the NSF Division of Molecular and Cellular Biosciences grant MCB-1513007, National Natural Science Foundation of China (21702182), Zhejiang University, the Chinese “Thousand Youth Talents Plan”, and the “Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” is gratefully acknowledged. K.C. thanks the Resnick Sustainability Institute at Caltech for fellowship support. X.H. is supported by an NIH pathway to independence award (grant K99GM129419).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1611662.

References

- (1).Fyfe JWB; Watson AJB Chem 2017, 3, 31. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Leonori D; Aggarwal VK Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lennox AJJ; Lloyd-Jones GC Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Brown HC; Ramachandran PV Pure Appl. Chem 1991, 63, 307. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Brown HC; Jadhav PK; Mandal AK Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 3547. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Miyaura N; Suzuki A Chem. Rev 1995, 95, 2457. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Martin R; Buchwald SL Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis and Medicine; Hall DG, Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Das BC; Thapa P; Karki R; Schinke C; Das S; Kambhampati S; Banerjee SK; Veldhuizen PV; Verma A; Weiss LM; Evans T Future Med. Chem 2013, 5, 653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Dembitsky VM; Al Quntar AA; Srebnik M Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li X; Curran DP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cheng Q-Q; Zhu S-F; Zhang Y-Z; Xie X-L; Zhou Q-LJ Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 14094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chen D; Zhang X; Qi W-Y; Xu B; Xu M-H J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hyde S; Veliks J; Liégault B; Grassi D; Taillefer M; Gouverneur V Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yang J-M; Li Z-Q; Li M-L; He Q; Zhu S-F; Zhou Q-LJ Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Pang Y; He Q; Li Z-Q; Yang J-M; Yu J-H; Zhu S-F; Zhou Q-LJ Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Allen TH; Kawamoto T; Gardner S; Geib SJ; Curran DP Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yang J-M; Zhao Y-T; Li Z-Q; Gu X-S; Zhu S-F; Zhou Q-L ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7351. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kan SBJ; Huang X; Gumulya Y; Chen K; Arnold FH Nature 2017, 552, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Huang X; Garcia-Borràs M; Miao K; Kan SBJ; Zutshi A; Houk KN; Arnold FH ChemRxiv 2018, DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv.7130852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chen K; Zhang S-Q; Brandenberg OF; Hong X; Arnold FH J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Coelho PS; Brustad EM; Kannan A; Arnold FH Science 2013, 339, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Coelho PS; Wang ZJ; Ener ME; Baril SA; Kannan A; Arnold FH; Brustad EM Nat. Chem. Biol 2013, 9, 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Brandenberg OF; Fasan R; Arnold FH Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2017, 47, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chen K; Huang X; Kan SBJ; Zhang RK; Arnold FH Science 2018, 360, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kan SBJ; Lewis RD; Chen K; Arnold FH Science 2016, 354, 1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lewis RD; Garcia-Borras M; Chalkley MJ; Buller AR; Houk KN; Kan SBJ; Arnold FH Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2018, 115, 7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Khade RL; Fan W; Ling Y; Yang L; Oldfield E; Zhang Y Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 7574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sharon DA; Mallick D; Wang B; Shaik SJ Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 9597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wei Y; Tinoco A; Steck V; Fasan R; Zhang YJ Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Stelter M; Melo AMP; Pereira MM; Gomes CM; Hreggvidsson GO; Hjorleifsdottir S; Saraiva LM; Teixeira M; Archer M Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kille S; Acevedo-Rocha CG; Parra LP; Zhang Z-G; Opperman DJ; Reetz MT; Acevedo JP ACS Synth. Biol 2013, 2, 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yang J-M; Li Z-Q; Zhu S-F Chin. J. Org. Chem 2017, 37, 2481. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Tehfe M-A; Monot J; Malacria M; Fensterbank L; Fouassier JP; Curran DP; Lacôte E; Lalevée J ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Renata H; Lewis RD; Sweredoski MJ; Moradian A; Hess S; Wang ZJ; Arnold FH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).DeAngelis A; Dmitrenko O; Fox JM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).General ProcedureTo a 20 mL vial were added a suspension of E. coli expressing Rma cytochrome c variant BORLAC (5 mL, OD600 = 15), borane (150 μL of a 400 mM stock solution in MeCN, 0.06 mmol), lactone diazo compound (150 μL of a 400 mM stock solution in MeCN, 0.06 mmol), and D-glucose (50 mM) in M9-N buffer (pH 7.4) under anaerobic conditions. The vial was capped and shaken (480 rpm) at room temperature for 18 h. Reactions were set up in quadruplicate. Upon completion, reactions in replicate were combined and transferred to 50 mL centrifuge tubes. The reaction vials were washed with water (2 × 2 mL) followed by a mixed organic solvent (hexane/ethyl acetate = 1:1, 3 × 2 mL). The washing solution was combined with the reaction mixture in the centrifuge tubes. An additional 15 mL of hexane/ethyl acetate solvent was added to every tube. The tube was then vortexed (3 × 1 min) and shaken vigorously, and centrifuged (5,000 × g, 5 min). The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was subjected to three more rounds of extraction. The organic layers were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography with hexane/(ethyl acetate/acetone 3:7) as eluent afforded the desired lactone-based organoboranes. Enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) was measured by chiral HPLC. TTN was calculated based on measured protein concentration and isolated product yield. Product 3a was obtained as a white solid (41.4 mg, 89%, 1290 TTN). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 6.83 (s, 2 H), 4.45 (dddd, J = 10.7, 8.1, 6.8, 1.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.27 (tq, J = 9.0, 1.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.83–3.69 (m, 6 H), 2.53–2.25 (m, 1 H), 2.01–1.93 (m, 1 H), 1.88–1.80 (m, 1 H), 1.79–1.16 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 187.91, 120.62, 67.86, 36.15, 30.86; 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3): δ = −27.08 (t, J = 89.6 Hz); HRMS (FAB+): m/z [(M + H+) – H2] calcd for C9H14O2N2B: 193.1148; found: 193.1144; Chiral HPLC (Chiralpak IC, 40% i-PrOH in hexane, flow rate: 1.5 mL/min, temperature: 32 °C, λ = 235 nm): tR (major) = 12.857 min, tR (minor) = 10.991 min; 96.2:3.8 e.r.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.