Abstract

Objectives.

We investigate the association between perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress among urban African-American women with young children (under 6 years) living in low-income neighborhoods. Specifically, we examine whether instrumental and emotional social support moderates the association between perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress.

Design.

The data come from the Detroit Dental Health Project, a two-stage area probability sample representative of low-income African-American children in the city of Detroit. The analysis focuses on 969 female caregivers of young children. A series of hierarchical regression analyses were performed to examine the role of social support in the link between perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress, with appropriate adjustments for the complex sample design.

Results.

Both moderate and high frequency levels of discrimination were associated with higher levels of psychological distress after controlling for age, education, income, and self-rated health. There was a main effect of emotional support so that availability of emotional support was associated with less psychological distress. Instrumental support exerted a buffering effect to mitigate the negative influence of moderate levels of perceived discrimination on psychological distress.

Conclusion.

Findings suggest that instrumental social support provides some protection from everyday stress. Social support, however, does not offset the impact of acute stress caused by frequent perceptions of everyday discrimination.

Keywords: discrimination, African-American women, depressive symptoms

Stress in the form of perceived discrimination has emerged as a critical element to understanding health disparities (Williams et al. 1997, Kessler et al. 1999, Schulz et al. 2000, Taylor and Turner 2002, Jackson et al. 2003, Pavalko et al. 2003, Williams and Mohammed 2009). At the same time, the value of examining within group patterns is now increasingly recognized as necessary if we are to better understand the multiple and complex processes by which stressors impact health (Essed 1991, Sigelman and Welch 1991, Keith et al. 2002, Lincoln et al. 2003, Schulz and Lempert 2004). The effect that everyday discrimination exerts on psychological distress may be attributable to whether and what type of resources is available to ameliorate its impact (Pearlin 1989).

Social support has been identified as one of the many psychosocial mechanisms that moderates stress-related health disparities (Turner and Marino 1994, Antonucci et al. 2003, Jackson et al. 2003), however, little research specifically examines the link that social support may have to the association between perceived discrimination and psychological distress (Brondolo et al. 2009). In this paper, we examine the associations between perceived everyday discrimination, social support, and psychological distress among African-American women caring for young children and living in low-income urban neighborhoods. The current study focuses on the ‘moderating hypothesis’ to posit that perceiving support to be available attenuates or ‘buffers’ the impact of frequently perceived everyday discrimination on psychological distress. In other words, for individuals higher in perceived social support, the association between perceived discrimination and psychological distress is hypothesized to be smaller as compared to that same association for individuals with lower perceived social support.

Women with multiple minority status characteristics and caring for a young child are at high risk of depressive symptoms, yet some still retain positive psychological well-being and the ability to function well. This paper seeks to contribute to our understanding of social support in the context of perceived frequent everyday discrimination. Although the health significance of perceived discrimination has been assessed in a number of studies (see Paradies 2006, Brondolo et al. 2009, Williams and Mohammed 2009 for reviews), evidence is accumulating to suggest that variations in exposure to more general stress forms including lifetime adversity should be examined simultaneously to better disentangle the true effects of discrimination (Wheaton 1994, Taylor and Turner 2002). African-American women living in urban, poverty-stricken neighborhoods represent one group potentially vulnerable to long durations of harsh conditions (Schulz et al. 2000). Neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES), racial, and gender heterogeneity are minimized in this study, and serve as proxies for other stress experiences. We aim to better recognize ways to increase or enhance resistance to the deleterious effects of discrimination among a group who may experience stress on multiple levels.

Perceived everyday discrimination as stress

African-Americans in all socioeconomic positions report experiencing discrimination (Feagin 1991, Smith and Kington 1997). Perceived discrimination differs from actual/external indicators of discrimination in that it is self-rated, and not objectively designated (Fischer and Shaw 1999, Williams and Mohammed 2009). As a result, it becomes an indirect measure shaped by a variety of affective and cognitive factors. Yet, subjective accounts of discrimination are highly important, allowing for one meaningful approach to define what constitutes discrimination (what one person deems unfair treatment another may not) and avoids the ethical dilemmas associated with exposing individuals to negative and unfair treatment in experimental manipulations (Fischer and Shaw 1999). Whether or not a person defines an encounter as unfair or discriminatory has enormous consequences for the reaction to that encounter. Following the Thomas dictum that a situation defined as real is real in its consequences, perceived discrimination constitutes a potentially powerful indicator of stress, and has enormous consequences for psychological well-being.

One aspect of perceived discrimination that renders discrimination stressful involves the frequency with which it is experienced. Williams and Mohammad (2009) suggest that perceiving discrimination frequently is likely to make persistent demands or to lead to endless threats that subsequently exasperate an individual. Everyday discrimination constitutes one perceived measure of discrimination that includes the element of frequency. Perceiving frequent discrimination is increasingly recognized as a significant and critical source of stress (Williams et al. 1997, Kessler et al. 1999, Taylor and Turner 2002, Pavalko et al. 2003, Gee et al. 2006, Prelow et al. 2006, Sanders Thompson 2006).

The stress of everyday discrimination includes perceptions of unfair treatment in subtle, yet highly influential ways. Everyday discrimination may be thought of as a chronic stressor, tapping into a more insidious experience of discrimination than reports of general perceived discrimination. Using racism as an example of one discrimination incident, Essed (1991) argues that experiences of racism on an everyday basis may be distinct from general racism in that it involves systematic and recurrent practices, crossing between individual perceptions and institutional practices. For example, a young woman who reports feeling that she was not hired for a job because she is African-American constitutes an episode that is experienced at one point in time, and no doubt has implications for well-being. Yet, more subtle regular forms of discrimination such as feeling treated with less courtesy and with less respect than other people when making a weekly shopping trip for groceries because she is African-American signifies an altogether more omnipresent form of unfair treatment that accumulates through daily interactions. We suggest that such recurrent experiences are important to study in order to further specify how such encounters impinge upon psychological distress among those potentially experiencing stress because of social position characteristics including race, gender, and SES (Essed 1991, Schulz et al. 2000, 2006, Schulz and Lempert 2004). The extent to which everyday discrimination is perceived within this particular subgroup and its effect on psychological distress represents an important area in need of further examination.

Social support and perceived discrimination

Social support is often considered a critical resource that influences mental health outcomes (Cohen and Syme 1985, Antonucci and Jackson 1987, Russell and Cutrona 1991, Seeman 1996). The association between social support and health is complex, however. First, ‘social support’ may be instrumental or emotional. Emotional support refers to having someone to confide in or to simply listen to issues related to either positive or negative events. Instrumental support involves help with tangible needs including financial, childcare, errands, and transportation needs. Each of these may influence health in unique ways (Antonucci 1994, Lynch 1998). Second, the potential for social relationships to offset the negative effects of stress on health has been widely discussed and demonstrated over the past several decades (see Pearlin 1999, for a review). According to Cohen and Wills (1985), emotional support provides a buffer to a wide ranging category of stress while instrumental support is effective when the support provided coincides with the stress experienced, i.e., financial help in the face of poverty. In the current study, by focusing on two types of support (instrumental and emotional) we seek to contribute to the literature by avoiding generalizations that aggregate across important differences in social support type.

The limited research on how social support intervenes to influence the effect of perceived discrimination on health suggests that social support represents a coping strategy (Brondolo et al. 2009). The effectiveness of support may vary by which types are available in the face of perceived discrimination (Atri et al. 2007). Negative health outcomes are associated with the stress of perceived discrimination and the related experience of social inequality, yet these effects can be successfully buffered by emotional dimensions of social support (Jackson et al. 2003). On the other hand, others find social support exerts a direct effect on well-being, but does not buffer the effects of perceived discrimination on well-being (Fischer and Shaw 1999, Noh and Kaspar 2003, Sanders Thompson 2006). We explore whether instrumental and emotional types of support produce varied consequences on the association between perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress.

It should be noted that previous studies on discrimination and well-being have measured social support in divergent ways. Some examples include: co-ethnic network composition and co-ethnic support availability (Fischer and Shaw 1999, Noh and Kaspar 2003), family support availability (Weems et al. 2007), frequency of support seeking (Sanders Thompson 2006), and the extent to which study participants agree on availability of support (Atri et al. 2007). In the present study, social support is a perceived measure of availability on multiple instrumental aspects and one indicator of emotional support.

Recent research in this area that focuses exclusively on African-American samples suggests that the existence of social support is not guaranteed in vulnerable populations. For instance, instrumental support tends to be lower when financial strain is high (Schulz et al. 2006). There is some suggestion that social support may be helpful at low levels of stress exposure, but exacerbates difficulties at high levels of exposure (Brondolo et al. 2009). Additionally, social support does not yield a positive outcome on psychological distress in the face of some types of stressors such as traumatic events or neighborhood disorganization (Latkin and Curry 2003, Lincoln et al. 2005). Yet Schulz and Lempert (2004) document how women living in economically divested and racially segregated areas are especially likely to rely on social support as a resource. By focusing on a unique sample, we are positioned to examine whether various dimensions of social support moderate the effects of perceived everyday discrimination on psychological distress among African-American women living in high-poverty areas.

The availability of social support and its link to psychological distress may be particularly critical among women caring for small children. Previous research has uncovered high prevalence rates of elevated depressive symptoms among mothers of young children, which on occasion persist over time (McLennan et al. 2001). As primary caregivers, the health and well-being of these women may have ramifications that shape and influence their child’s development (Chung et al. 2004). The nature and type of social support available to women with small children, particularly those living in challenging environments, represent a potential naturally occurring resource (i.e., social support may emerge spontaneously through relationships enacted with others) about which more information is needed.

Study goals

The present study seeks to investigate the impact of social support on the perceived discrimination−psychological distress health link among African-American women living in a poverty-stricken urban area. Among African-American women, perceived discrimination links consistently with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Brown et al. 2000, Keith et al. 2002). We first examine the prevalence of psychological distress, social support, and perceived everyday discrimination, and then secondly, test whether aspects of social support moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological distress. Given the paucity of information on the ways in which instrumental and emotional support may influence how perceived discrimination influences psychological distress, we refrain from proposing specific hypotheses about support type.

The presence of social support may constitute a resource among individuals with high levels of stress to mitigate the negative effects on health (Pearlin et al. 1981, Thoits 1982, Cohen and Wills 1985, Wheaton 1985); and social support may act as a buffer against everyday discrimination by decreasing the perceived importance of the problem, the stress reaction, or by providing a problem solution (Williams 1990). The homogeneity of the sample in terms of three key social position indicators: race, neighborhood SES, and gender allows us to test the moderating hypothesis within an exceptionally stressed population. An examination of variability within this subgroup of US society may reveal a more refined portrait of the social psychological underpinnings of the stress process.

Methods

Study design and sample

This study was part of the Detroit Center for Research on Oral Health Disparities, known as the Detroit Dental Health Project (DDHP), funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR; see Ismail et al. 2008, for a detailed description of DDHP). A two-stage area probability sample was used to select a representative sample of low-income African-American children in the city of Detroit. Participants came to a central location in Detroit in the African-American community where they completed interviewer-administered questionnaires and had an oral health examination. Data were collected on a rich array of social and environmental factors potentially associated with health outcomes during the first phase of the DDPH longitudinal survey of African-American caregivers of young children. The resulting data-set provides a unique opportunity to examine how these factors relate to caregiver well-being in this population. Participants were at the Detroit Center for approximately 4 hours to complete all portions of the study. Of the 1386 families with eligible children, 1021 completed the baseline study. The combined screening and interviewing response rate was 74%. Given the small number of male caregivers (n = 52), the present study analyzed data only from female caregivers of children aged five and under (n = 969). Of those caregivers 92% reported being the biological mother (n = 879), 5% the grandmother (n = 60), and 3% as someone else (n = 30).

Measures

Outcome variable.

We seek to explain variance is psychological distress. Psychological distress was measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report scale that measures frequency of mood and behavioral symptoms that occurred during the previous week. Items are rated on a four-point scale ranging from ‘rarely/none of the time’ to ‘most or all of the time.’ Scores ranged from 0 to 60 with high scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Positively worded items were reverse coded. The CES-D showed excellent reliability in this sample (α = 0.90). A mean score of 9 is typical of community samples. A score of 16 and above is indicative of psychological distress associated with clinical depression (Radloff and Locke 1986, Jackson et al. 2000).

Predictor variables.

Perceived discrimination and social support are the main predictor variables in our study. Perceived discrimination was measured using the ‘Everyday Discrimination’ scale to ascertain the frequency of chronic, routine experiences of unfair treatment (Jackson et al. 1996, Schulz et al. 2000). Table 1 presents the scale items with the response options: (1) almost every day; (2) at least once a week; (3) a few times a month; (4) a few times a year; (5) less than once a year; and (6) never. Following the procedure outlined by Hunt et al. (2007), a summary count was created to indicate the number of discriminatory reports experienced a few times a month or more frequently. Table 1 presents the frequency distribution of responses to each item and the distribution of the summary count variable. Because of the skewed distribution on this count variable and due to the fact that approximately one-third of the sample reported never experiencing these episodes of discrimination, we created three categories to allow for a graded distinction of discrimination reports. Categories include: 0 = never (no experience of discrimination that occurs a few times a month or more; 33.6%); 1 = less than five areas of reported discrimination experienced a few times per month or more (45.5%); and 2 = five or more areas of discrimination experienced at least a few times a month (20.9%). This categorization was developed based on the frequency distribution of participant reports of everyday discrimination. Given that there were 10 possible areas of perceived everyday discrimination, we chose the half-way mark (five areas), to designate the separation between moderate and high levels of discrimination (see Table 1). Those who reported five or more were subsequently labeled as experiencing high levels of everyday discrimination.

Table 1.

Everyday discrimination scale items, frequency of responses, and number of discrimination areas experienced a few times per month or more.

| Areas of discrimination | Weighted row (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| More frequent than a few times a month | Less frequent than a few times a month | |

| I was treated with less courtesy than others | 36.4 | 63.6 |

| I was treated with less respect than others | 30.0 | 70.0 |

| I received poorer service than others | 31.3 | 68.7 |

| People acted as if they thought I am not smart | 28.5 | 71.5 |

| People acted as if they were afraid of me | 14.5 | 85.5 |

| People acted as if they thought I am dishonest | 15.1 | 84.9 |

| People acted as if they thought they are better than me | 41.9 | 58.1 |

| I was called names or insulted | 25.3 | 74.7 |

| I was threatened or harassed | 11.8 | 88.2 |

| I was unfairly stopped, searched, questioned, or threatened by the police | 2.5 | 97.5 |

| I was unfairly discouraged by a teacher or adviser from continuing my education | 4.9 | 95.1 |

| Number of discrimination areas experienced a few times per month or more | n | Weighted (%) |

| 0 | 323 | 33.6 |

| 1 | 138 | 14.4 |

| 2 | 100 | 11.0 |

| 3 | 106 | 10.8 |

| 4 | 95 | 9.3 |

| 5 | 60 | 5.9 |

| 6 | 62 | 6.4 |

| 7 | 43 | 4.3 |

| 8 | 19 | 1.8 |

| 9 | 18 | 1.9 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 11 | 4 | 0.4 |

| Total | 969 | |

Instrumental and emotional dimensions of social support were assessed. First, we created a summed index of instrumental support, indicated by asking the participant to respond either yes or no as to whether there is someone the participant could count on to: ‘ … run errands for you if needed them to; lend you some money if you really needed it in a time of financial crisis; lend you a car or give you a ride if you needed them to, watch your (child/children) for you if you needed them to.’ Values ranged from 0 (no support on any of the instrumental dimensions) to 4 (support reported available on all four dimensions), and Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70. We also examined emotional support, indicated by asking the participant to respond either yes or no as to whether there is someone: ‘… you could count on to give you encouragement and reassurance if you really needed it.’ This measure was dummy coded where 1 = yes and 0 = no. Instrumental and emotional support types were tested in separate regression models.

The five social support questions used in this study are from the first wave of the Women’s Employment Study, a longitudinal survey of barriers to employment among 753 African-American and White mothers residing in an urban Michigan county and receiving welfare in 1997 (Danziger et al. 2000, Siefert et al. 2000, Henly et al. 2005, Nam et al. 2006). The questions are theory-based (House 1986, McLoyd et al. 1994) and similar questions have been used in other studies of social support and parenting among low-income African-American mothers (see for example, McLoyd et al. 1994, Jackson et al. 2000). While the use of a more detailed and comprehensive measure would have been ideal, and this limitation should be addressed in future research, respondent burden necessitated brevity as well as use of questions demonstrated to be acceptable to this unique study population.

Covariates.

The following measures, identified in previous studies as influential (e.g., Taylor and Turner 2002), were included to control for potential confounding effects on psychological distress. Age was computed using the date of birth and date of the interview. Self-rated health was measured by asking the participant to rate their health on a six-point scale ranging from very poor, poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent over the last week. Response categories were recoded into a four-point scale where ‘very poor,’ ‘poor,’ and ‘fair’ were collapsed due to low frequencies. The final self-rated health indicator contained four categories ranging from: very poor − fair, good, very good, and excellent. Previous research suggests an association between discrimination and poor self-rated health status. Following MacKinnon and Luecken (2008) we tested whether self-rated health was correlated with perceived discrimination to determine a possible mediation effect (as opposed to the proposed potential confounding effect). Results revealed that there was no statistically significant correlation between perceived discrimination and self-rated health in our sample (results available upon request). Income was assessed by asking respondents to indicate total combined family income in the last 12 months including resources from wages, salaries, social security, retirement, help from relatives, etc. In this analysis, income was coded such that 0 = less than $10,000, 1 = $10,000−$19,999, and 2 = $20,000 and higher. Education was assessed by total years of school completed. Participants responded to the question ‘What is the highest grade of school you have completed or highest degree you have received?’ Education was coded such that 0 = less than high-school education, 1 = high-school diploma, and 2 = some college or more. Those who reported obtaining an equivalency diploma, known as the General Educational Development, or GED (n = 64) were coded into the high-school diploma category.

Method of analysis

The composition of the sample in terms of study characteristics was analyzed first. To address the research question of whether social support moderated the association between everyday discrimination and psychological distress, a series of multiple regression analyses were performed. Eligibility and analytic criteria to establish variables as moderators may vary depending on the approach used and available data. New analytic developments such as the MacArthur procedure (Kraemer et al. 2008) introduce innovative approaches, but require longitudinal data to demonstrate that the moderator existed before the occurrence of the stressor. We followed the procedure recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) because it can be applied using cross-sectional and retrospective data. A series of hierarchical regression analyses were performed. First, psychological distress was regressed on the independent variables of age, self-rated health, education, perceived everyday discrimination, and the social support type of interest. Regression analysis was repeated with the interaction of everyday discrimination and social support (centered). Because of the complex sample data and weight effects, we report the R square in all regression models. If a significant amount of additional variance was accounted for by the interaction term in this last step (using a Wald test to adjust for the complex sample design), a moderating or ‘buffering’ effect of the social support variable on the association between discrimination and psychological distress could be inferred.

The SAS (2002) software was used to account for clustering effects from the complex survey design. All analyses were weighted to account for unequal selection probabilities and differential non-response. A small number of missing values (less than 5% for any individual item) were imputed using the IVEware software (Raghunathan et al. 2002).

Results

Table 2 presents the sample distribution displaying weighted percentages of all analytic variables as well as the mean and standard deviation of depressive symptoms. This sample was relatively young, with over 75% reporting an age under 35 years old. Approximately 45% of the sample reported less than $10,000 annual income and did not complete high school. Two-thirds of the sample (66.7%) stated they had available to them all areas of instrumental support (running errands, money in times of need, transportation, and childcare). Approximately 90% of the sample affirmed support in the form of encouragement. As previously reported, 33% reported never experiencing frequent discrimination, approximately 46% asserted frequent discrimination in less than five domains, and 21% described frequent discrimination in five domains or more. Approximately 80% rated their health as good or better, and the mean depressive symptom score (CES-D) was 14.0 (SE = 0.04).

Table 2.

Mean psychological distress by study sample characteristics (n = 969).

| Key variable | n (weighted %) | Weighted mean of psychological distress indicated by CESDa (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 14−24 | 328 (33.8) | 14.2 (0.7) |

| 25−34 | 443 (48.1) | 14.3 (0.7) |

| 35+ | 198 (18.1) | 12.9 (0.6) |

| Income | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 434 (45.3) | 15.0 (0.7) |

| $10,000 ~$19,999 | 262 (26.8) | 12.8 (0.6) |

| More than $20,000 | 273 (27.9) | 13.5 (0.7) |

| Education* | ||

| Less than high school | 456 (47.0) | 14.9 (0.5) |

| High-school diploma | 304 (31.2) | 13.9 (0.8) |

| Some college or more | 209 (21.8) | 12.4 (0.8) |

| Social support Instrumental support index*** | ||

| 0 | 26 (3.5) | 28.6 (3.6) |

| 1 | 64 (6.0) | 19.1 (1.8) |

| 2 | 90 (8.5) | 18.5 (1.0) |

| 3 | 151 (15.3) | 14.4 (1.0) |

| 4 | 638 (66.7) | 12.1 (0.4) |

| Emotional support*** | ||

| Yes | 890 (91.9) | 13.2 (0.5) |

| No | 79 (8.1) | 23.2 (1.9) |

| Frequent discrimination*** | ||

| Never | 323 (33.6) | 9.3 (0.4) |

| <5 areas | 439 (45.5) | 13.8 (0.6) |

| ≥ 5 areas | 207 (20.9) | 21.9 (1.0) |

| Self-rated health*** | ||

| Very poor − poor − fair | 199 (21.0) | 20.1 (1.2) |

| Good | 303 (30.1) | 13.5 (0.7) |

| Very good | 263 (27.0) | 11.8 (0.7) |

| Excellent | 204 (21.9) | 11.4 (0.6) |

| Total | 969 | 14.0 (0.4) |

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

p <.05

p <.001.

Individuals who reported low education levels, no support of any type, perceiving frequent discrimination (≥5 areas), and low self-rated health all reported significantly higher CES-D scores (more psychological distress) than those with higher education, those who reported available support of any type, those who perceived no discrimination, and those who reported excellent self-rated health.

Social support as a moderator

Multivariate hierarchical linear regressions assessing the main and interaction effects of social support on the relationship between everyday discrimination and psychological distress were conducted next (see Table 3). Controlling for age, education, income, and self-rated health, results demonstrated that both moderate and high frequency levels of discrimination were associated with higher levels of psychological distress (Table 3, Model 1: Main effect model). The inclusion of emotional and instrumental support in the next model illustrated that high levels of both support types were associated with lower levels of psychological distress. Furthermore, findings showed that though the beta coefficients decreased slightly, both moderate and high frequency levels of discrimination continued to be significantly associated with higher levels of psychological distress (Table 3, Model 2: Main effect model).

Table 3.

Estimated regression coefficients (95% confidence intervals (CI)) for the association between perceived frequent discrimination, social support, and psychological distress among urban African-American women (n = 969).a

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional support | Instrumental support | Emotional support | Instrumental support | |||

| Predictors | Regression coefficients (95% CI) | |||||

| Frequent discrimination | Never | – | – | – | – | – |

| <5 areas | 4.0*** (2.7–5.3) |

3.8*** (2.6–5.0) |

3.7*** (2.5–5.0) |

6.6* (0.3–12.9) |

4.1*** (2.7–5.5) |

|

| ≥5 areas | 11.7*** (9.4–13.9) |

11.0*** (8.8–13.1) |

10.4*** (8.1–12.6) |

11.9** (4.4–19.4) |

10.6*** (8.3 12.9) |

|

| Social support | –6.9*** (–10.6 to –3.1) |

–2.0*** (–2.8 to –1.2) |

–5.2 (–11.8 to 1.3) |

–0.7 (–2.5 to 1.1) |

||

| Interaction | <5 areas×social support |

–3.0 (–9.3 to 3.4) |

–2.0* (–3.9 to –0.2) |

|||

| ≥5 areas×social support |

–0.9 (–9.4 to 7.6) |

–1.3 (–3.7 to 1.0) |

||||

| Intercept | 16.1*** (13.5–18.6) |

22.2*** (18.1–26.2) |

15.9*** (13.7–18.2) |

20.7*** (14.2–27.1) |

15.6*** (13.3–17.8) |

|

| R square | 24.7% | 27.6% | 28.4% | 27.7% | 29.2% | |

| F statistics | 25.7*** | 33.4*** | 30.9*** | 25.8*** | 28.2*** | |

| Wald test F | 14.2*** | 25.0*** | 0.6 | 4.1* | ||

Model 1 excludes social support, Model 2 includes social support, and Model 3 includes discrimination−social support interactions.

p <.05

p <.01

p <.001.

Note: All models controlled for age, education, income, and self-rated health.

Similar to the bivariate results, age and self-rated health were significantly associated with psychological distress so that younger age and worse self-rated health were associated with higher levels of psychological distress. Income levels were associated with psychological distress, though education level was not. Having an annual income level less than $10,000/year was associated with higher levels of psychological distress (results not shown).

Model 3 in Table 3 presents results at the final stage of analysis. Significant interactions between social support and everyday discrimination emerged for instrumental support (p <0.05). The amount of additional variance explained by adding the interaction between social support and discrimination to the variables already in the model was significant (F = 4.1; p <0.05). Emotional support exerted no significant interaction effect on the association between frequent everyday discrimination and psychological distress.

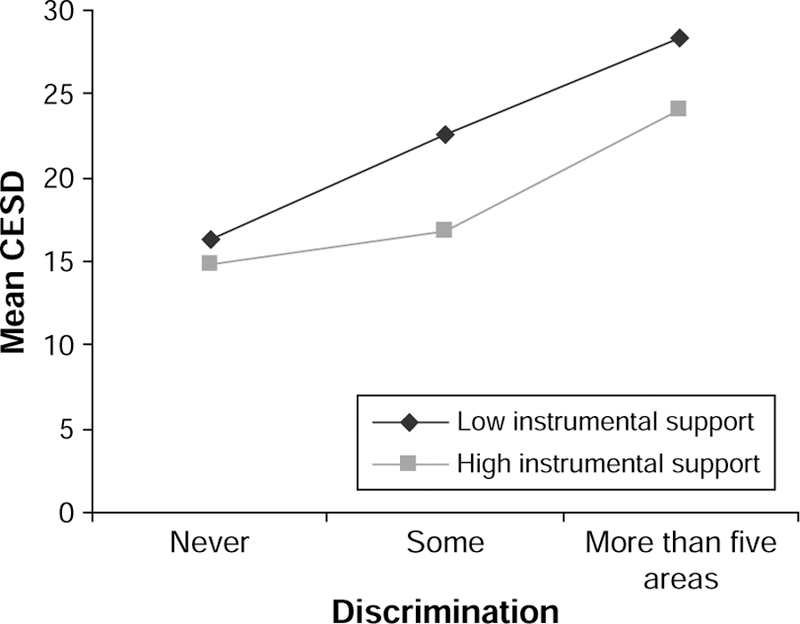

The interaction effect of instrumental social support and everyday discrimination on psychological distress is illustrated in Figure 1. Low instrumental support was defined as one standard deviation below the mean, and high instrumental support as one standard deviation above the mean. Instrumental social support did not significantly influence psychological distress among those who reported never having experienced discrimination as the mean CES-D scores occurred at similar levels regardless of whether these women perceived support available. Yet, African-American women who reported one to five episodes of discrimination exhibited lower CES-D scores when they had support with instrumental needs. In other words, the average psychological distress level increased as discrimination levels rose, but this increase in psychological distress was steeper for those with low instrumental support. For those who perceived moderate levels (less than five incidents), instrumental support also yielded positive effects to moderately buffer the established association between everyday discrimination and psychological distress.

Figure 1.

Interaction effect of instrumental support and perceived everyday discrimination on psychological distress as indicated by CES-D.a

aCenter for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Discussion

The interplay between everyday discrimination and social support reveals important patterns for understanding processes influencing psychological distress among urban, low-income African-American women. Overall, the women in this study report high depressive symptom scores and high levels of social support. Yet, diversity exists in that everyday discrimination was not uniformly experienced. Additionally, findings indicate that instrumental social support to some extent mitigates the associations between psychological distress and perceptions of everyday discrimination. Implications are discussed below.

Prevalence and influence of perceived discrimination

This study provides an opportunity to assess the incidence and impact of perceived discrimination within a specific racial, gender, and SES context. Results demonstrate that perceived discrimination is a critical issue for some African-American women living in high-poverty areas. Comparative studies suggest that Black men experience more discrimination than Black women (Borrell et al. 2006), and those with higher educational levels report more discrimination than those with less education (Borrell et al. 2006, Vines et al. 2006). Studies are mixed concerning segregated neighborhoods. Some report those living in less segregated neighborhoods experience more discrimination (Hunt et al. 2007), and others finding the opposite to be true (Schulz et al. 2000). Our findings highlight that among African-American women living in high-poverty areas, frequent discrimination is perceived among a sizeable number, and has potentially dire psychological consequences.

Social support as a buffer

Our findings illustrate the potential role social support plays under highly stressed conditions. First, even within highly stressed populations individuals perceive the availability of social support. Second, results demonstrated a main effect where availability of emotional and instrumental support was negatively associated with psychological distress. As established in previous research, social support availability is associated with positive psychological well-being (Cohen and Syme 1985, Antonucci and Jackson 1987, Russell and Cutrona 1991, Seeman 1996).

Though uncovering main effects of social support on psychological distress have important implications, the interplay between social support, everyday discrimination, and psychological distress within this subgroup provides key preliminary insights into the social psychological processes affecting well-being. Instrumental support was a significant buffer among those who perceived moderate levels of everyday discrimination, but its effect weakened for those perceiving excessive everyday discrimination. These findings contribute two important notions regarding the role of social support among African-American women living in poverty-stricken urban areas.

First, social support type matters. Emotional support did not buffer the effects of frequent discrimination on psychological distress. Though others suggest emotional support often provides an effective buffer regardless of the stress source (see Cohen and Wills 1985), in this case emotional support may not be influential because there was so little variation; further, our analyses show that women who perceived frequent discrimination reported higher levels of emotional support than they did any one of the instrumental support dimensions (results available upon request). Yet, higher levels of instrumental support mattered. What emerges as critical for the population under study here is the amount of instrumental support available.

Second, results intimate the notion that social support among vulnerable populations may serve primarily a coping function, rather than a leverage function (Henly et al. 2005). In other words, instrumental social support provides some protection in the face of stress, but lacks the influence to totally offset effects of acute stress levels indicated by extremely frequent perceptions of everyday discrimination. Mothers or caregivers of young children living in low-income segregated neighborhoods face constraints and complications concerning the availability and uses of social support (Henly et al. 2005). Mobilizing support to cope involves access to networks that do not drain the women’s own limited resources (Dominguez and Watkins 2003). Moreover, it may be that lifelong experience with discrimination influence perceptions of who is trustworthy, and therefore affect social support dynamics. Thus, instrumental support may be mobilized under duress to cope, but it does not provide a resource that fully alters the association between perceived discrimination and psychological distress. This point draws attention to the need for resources above and beyond those available from informal relations with other people. In other words, social support is necessary, but not sufficient to the well-being of those facing chronic stresses.

Finally, there are limitations to this research involving the cross-sectional nature of the sample and the available social support measures. The cross-sectional nature of our data precludes any attempt to assert a causal relationship between the indicators. This restricts our ability to fully test moderating effects. For instance, the source of discrimination is not evaluated. Furthermore, we are unable to establish temporal sequence between perceived discrimination and social support (Kraemer et al. 2008). Consequently, our results indicating a potential buffering effect of social support are suggestive, not conclusive.

These survey data also offer a limited view of the nuances of social relationships, and why they are important to mental health. The dichotomized measures provide some indication of support availability, but do not allow us to distinguish whether or not such support is activated. Such distinctions are important for better examining potential moderating effects of social support (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al. 2006). Future studies should consider including more detailed indicators of social support such as integration, satisfaction with support, as well as identifying negative aspects of support. Additionally, the inclusion of organizational aspects of social support such as religious attendance, and more direct measures of stress that reflect social position factors, including trauma and life events, may better illuminate the ways in which social support operates to influence well-being within this distinct population. Finally, bringing in indicators of personality would allow for the possibility that social support measures indicate individual differences rather than differences in environmental social support resources (see Sarason et al. 1990).

Though data limitations exist, the results of this study nevertheless provide useful preliminary data on the role of social support in the perceived discrimination−psychological distress link. The inclusion of two support dimensions examined separately helps to specify forms of support most germane to this population. Replication of these findings in other samples of African-American women living in poverty-stricken areas is essential to corroborate the results described here and to refine our understanding of the role social support plays in alleviating the influence of perceived discrimination on mental health among socioeconomically vulnerable groups. This sample represents a unique group of low-income women, living in a homogeneously impoverished neighborhood. There may be unique aspects of everyday discrimination they experience that should be examined in greater detail. Future directions should examine these associations over time and explore the nature of support in more depth.

Policy implications

Analysis of perceived frequent discrimination draws attention to an increasingly recognized source of stress, particularly among those occupying the lowest social position strata within US society. The fact that perceptions of very frequent experiences of discrimination do occur within this population and that they link to high depressive symptom scores highlights an understudied issue. Providing targeted assistance to those perceiving discrimination is warranted (Williams and Mohammed 2009). More systematic studies of perceived discrimination among vulnerable populations will provide a better understanding of the sources of this discrimination, and how individual and organizational interventions may be developed to reduce negative health consequences from this form of stress.

The preliminary findings regarding the utility of informal social support among this vulnerable population suggest caution in relying only on informal support for help in coping with the effect of perceived discrimination. During the last two decades research has been accumulating to suggest that social support should not be considered a taken-for-granted resource, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities. The developing consensus is that exchanges of social support involve a complex set of circumstances heavily influenced by personal and situational characteristics, as well as the socio-historical time period in which one lives. For instance, Roschelle (1997) details how the economic restructuring of the USA during the 1980s especially affected racial and ethnic minorities, contributing to their declining ability to provide resources to friends and relatives in need. More recent findings highlight how norms of reciprocity make social support exchanges among those living in poverty much more challenging, particularly concerning survival needs (Dominguez and Watkins 2003).

The creation of formal support sources that address disparities among African-American women living in high-poverty urban areas poses one area in need of further development. Careful planning should take place to ensure that such options link to instrumental support options that present opportunities above and beyond what the women may already access. For instance, pathways to find sources of income through paid employment as well as reliable and high-quality childcare options may aid in alleviating psychological distress. Finally, the significantly high psychological distress patterns detected within this population draw attention to the potential need for health clinics to be available in high-poverty areas equipped to treat depression and depressive symptoms.

Our study provides preliminary insights into how social support operates in the face of frequent chronic stress among a group incurring minority status on multiple levels. Social support, particularly of an informal nature, may play an important role in mitigating the effects of perceived everyday discrimination on psychological distress; yet, social support alone may not be enough to help the most vulnerable under highly stressful conditions.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported with funding from the National Institute on Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) grant no. U-54 DE 14261–01, the Delta Dental Fund of Michigan, and the University of Michigan’s Office of Vice President for Research. The authors thank the staff of the project for their diligence and commitment.

References

- Antonucci TC, 1994. A life-span view of women’s social relations. In: Turner BF and Troll LE, eds. Women growing older Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 239–269. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, and Janevic MR, 2003. The significance of social relations with children to the SES-health link in men and women aged 40 and over. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 949–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC and Jackson JS, 1987. Social support, interpersonal efficacy, and health. In: Carstensen LL and Edelstein BA, eds. Handbook of clinical gerontology New York: Pergamon Press, 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Atri A, Sharma M, and Cottrell R, 2007. Role of social support, hardiness, and acculturation as predictors of mental health among international students of Asian Indian origin. The International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 27 (1), 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM and Kenny DA, 1986. The moderator−mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, et al. , 2006. Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 1415–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, et al. , 2009. Coping with racism: a selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 64–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, et al. , 2000. Being black and feeling blue: the mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society, 2, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, et al. , 2004. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics, 113, 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S and Syme LS, 1985. Social support and health New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S and Wills TA, 1985. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danziger S, et al. , 2000. Barriers to the employment of welfare recipients. In: Cherry R and Rodgers W, eds. Prosperity for all? The economic boom and African Americans New York: The Russell Sage Foundation, 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez S and Watkins C, 2003. Creating networks for survival and mobility: social capital among African-American and Latin-American low-income mothers. Social Problems, 50 (1), 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Essed P, 1991. Understanding everyday racism: an interdisciplinary theory Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, 1991. The continuing significance of race: anti black discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review, 56, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR and Shaw CM, 1999. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: the moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46 (3), 395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, et al. , 2006. Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. American Journal of Public Health, 96 (4), 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henly JR, Danziger SK, and Offer S, 2005. The contribution of social support to the material well-being of low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67 (1), 122–140. [Google Scholar]

- House JS 1986. Social support and the quality and quantity of life. In: Andrews FM, ed. Research on the quality of life Ann Arbor, MI: Institute of Social Research Monograph Series, University of Michigan, 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MO, et al. , 2007. Neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination: evidence from the black women’s health study. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70 (3), 272–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail AI, et al. , 2008. Risk indicators for dental caries using the international caries detection and assessment system (ICDAS). Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 36, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AP, et al. , 2000. Single mothers in low-wage jobs: financial strain, parenting, and preschoolers’ outcomes. Child Development, 71, 1409–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, et al. , 1996. Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: a thirteen year national panel study. Ethnicity and Disease, 6, 132–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Williams DR, and Torres M, 2003. Perceptions of discrimination, health and mental health: the social stress process. In: Rockville A and Maney MD, eds. Social stressors, personal and social resources, and their mental health consequences Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 86–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti I, et al. , 2006. Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37 (3), 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Keith VM, et al. , 2002. Glass ceilings and closed doors: racial discrimination and mental health among African American women. Paper presented at International Sociological Association, XV World Congress of Sociology, 2 July 2002 Brisbane, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, and Williams DR, 1999. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, et al. , 2008. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology, 27 (2, Suppl.), S101–S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA and Curry AD, 2003. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: a prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, and Taylor RJ, 2003. Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44 (3), 390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, and Taylor RJ, 2005. Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 754–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SA, 1998. Who supports whom? How age and gender affect the perceived quality of support from family and friends. The Gerontologist, 38, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP and Luecken L, 2008. How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology, 27 (2, Suppl.), S99–S100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan JD, Kotelchuck M, and Cho H, 2001. Prevalence, persistence, and correlates of depressive symptoms in a national sample of mothers and toddlers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40 (11), 1316–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, et al. , 1994. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development, 65, 562–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y, Meezan W, and Danziger SK, 2006. Welfare recipients’ involvement with child protective services after welfare reform. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 1181–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S and Kaspar V, 2003. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health, 93 (2), 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, 2006. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35 (4), 888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko EK, Moss KN, and Hamilton VJ, 2003. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44 (1), 18–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, 1989. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, 1999. Stress and mental health: a conceptual overview. In: Horwitz AV and Scheid TL, eds. A handbook for the study of mental health: social contexts, theories, and systems New York: Cambridge University Press, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, et al. , 1981. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Mosher CE, and Bowman MA, 2006. Perceived racial discrimination, social support, and psychological adjustment among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology, 32, 442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS, 1977. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 32, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS and Locke BZ, 1986. The community mental health assessment survey and the CES-D scale. In: Weissman WW, Myers JD, and Ross CE, eds. Community surveys of psychiatric disorders New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan TE, Solenberger P, and van Hoewyk J, 2002. IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software Available from: http://www.isr.umich.edu/src/smp/ive/ [Accessed 15 February 2007].

- Roschelle AR, 1997. No more kin: exploring race, class, and gender in family networks Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW and Cutrona EC, 1991. Social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among the elderly: test of a process model. Psychology and Aging, 6, 190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson VL, 2006. Coping responses and the experience of discrimination. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36 (5), 1198–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Sarason IG, and Pierce GR, eds., 1990. Social support: an interactional view New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, 2002. SAS (Version 9.1) [Statistical software] Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, et al. , 2000. Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the metropolitan Detroit area. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 314–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, et al. , 2006. Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women in Detroit’s eastside. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 510–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A and Lempert LB, 2004. Being part of the world: Detroit women’s perceptions of health and the social environment. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 33, 437–465. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, 1996. Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Annals of Epidemiology, 6, 420–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert K, et al. , 2000. Social and environmental predictors of maternal depression in current and recent welfare recipients. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70 (4), 510–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman L and Welch S, 1991. Black Americans’ views of racial inequality: the dream deferred Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP and Kington R, 1997. Demographic and economic correlates of health in old age. Demography, 34, 159–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J and Turner RJ, 2002. Perceived discrimination, social stress, and psychological distress in the transition to adulthood: racial/ethnic contrasts. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA, 1982. Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical problems in studying social support as a buffer against stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 23, 145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ and Marino F, 1994. Social support and social structure: a descriptive epidemiology. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 193–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vines AI, et al. , 2006. Social correlates of the chronic stress of perceived racism among Black women. Ethnicity and Disease, 16, 101–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, et al. , 2007. The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45 (10), 2295–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, 1985. Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26, 352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, 1994. Sampling the stress universe. In: Avison W and Gotlib I, eds. Stress and mental health: contemporary issues and prospects for the future New York: Plenum, 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, 1990. Socioeconomic differentials in health: a review and redirection. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53, 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, et al. , 1997. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR and Mohammed SA, 2009. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]