Abstract

Background:

Current modulator therapies for some cystic fibrosis-causing CFTR mutants, including N1303K, have limited efficacy. We provide evidence here to support combination potentiator (co-potentiator) therapy for mutant CFTRs that are poorly responsive to single potentiators.

Methods:

Functional synergy screens done on N1303K and W1282X CFTR, in which small molecules were tested with VX-770, identified arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine, phenoxy-benzimidazole and flavone co-potentiators.

Results:

A previously identified arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine co-potentiator (ASP-11) added with VX-770 increased N1303K-CFTR current 7-fold more than VX-770 alone. ASP-11 increased by ~65 % current of G551D-CFTR compared to VX-770, was additive with VX-770 on F508del-CFTR, and activated wildtype CFTR in the absence of a cAMP agonist. ASP-11 efficacy with VX-770 was demonstrated in primary CF human airway cell cultures having N1303K, W1282X and G551D CFTR mutations. Structure-activity studies on 11 synthesized ASP-11 analogs produced compounds with EC50 down to 0.5 μM.

Conclusions:

These studies support combination potentiator therapy for CF caused by some CFTR mutations that are not effectively treated by single potentiators.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, CFTR, high-throughput screen, potentiator, N1303K

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis is caused by loss of function mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. CFTR is a cAMP-regulated, ATP-gated chloride channel that is normally expressed at the apical plasma membrane of epithelial cells in the airways, intestine, pancreatic duct and other tissues (1). There has been remarkable progress in the drug development to treat the underlying cellular processing and gating defects produced by mutations in CFTR. The potentiator ivacaftor (VX-770) has been approved to treat cystic fibrosis caused by the G551D mutation and at least 38 other mutant CFTRs with defective channel gating (1). The corrector lumacaftor (VX-809) in combination with ivacaftor has been approved to treat cystic fibrosis caused by the F508del mutation (1). However, the limited efficacy of lumacaftor/ivacaftor therapy in cell models and human clinical trials has motivated the development of corrector combination therapies in which a potentiator is combined with two correctors, each in principle targeting a distinct structural or dynamic defect in F508del-CFTR (2). We previously reported the first ‘corrector synergy’ screen to identify compounds, which when added together with lumacaftor, produced greater efficacy than maximal lumacaftor alone (3).

While approved and investigational potentiators and correctors, when sufficiently advanced, may be beneficial to most patients with cystic fibrosis, there remains ~10% of patients that are not amenable to these therapies (1). The most common CFTR mutations in these subjects include premature stop codon (PTC) mutations such as G542X and W1282X, and point mutations such as N1303K, which appear to be refractory to available potentiators and correctors. N1303K-CFTR is a missense Class II mutation, with defective CFTR processing, cell-surface trafficking, and channel gating (1, 4–6). Globally, of the ~88,000 CF subjects that have provided information about their CFTR mutations in the CFTR2 database, 99 (~0.1%) and 1,238 (~1.4%) have N1303K/N1303K and N1303K/F508del CFTR mutations, respectively. CFTR modulator triple combinations may be applicable to some homozygous CF subjects with F508del and a ‘minimal function mutation’, including N1303K/F508del and W1282X/ F508del. Clinical development of these therapies is presently at phase II and soon to enter phase III trials.

Here, we advance the concept of combination potentiator (‘co-potentiator’) therapy for cystic fibrosis caused by difficult-to-treat CFTR mutations that appear to be refractory to treatment by single potentiators alone or in combination with correctors. Co-potentiators identified here from ‘potentiator synergy’ screens were found to act in synergy or additively when used in combination with ivacaftor, for the refractory CFTR mutants N1303K and W1282X, as well as for F508del and G551D. This work was motivated by our prior studies on the truncated protein product produced by the W1282X mutation (7), in which a potentiator in combination with VX-770 increased W1282X-CFTR function about 8-fold over that of VX-770 alone, normalizing W1282X-CFTR channel activity to that of wild-type CFTR.

RESULTS

N1303K-CFTR cell line generation and potentiator screen

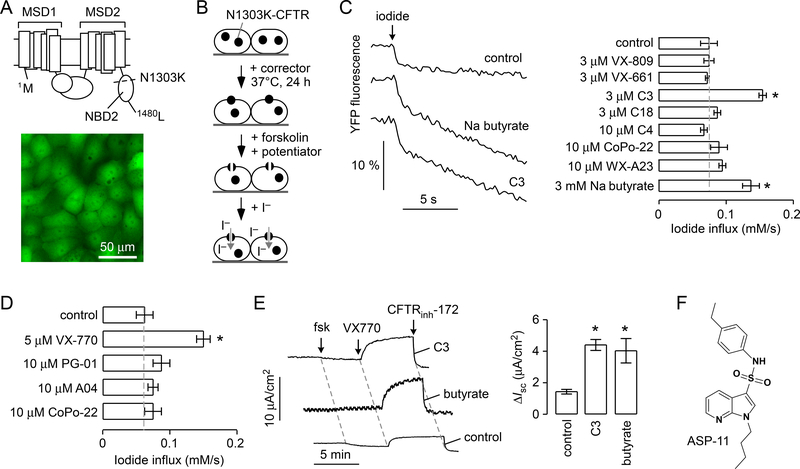

FRT cells stably expressing N1303K-CFTR and the halide sensor YFP-H148Q/I152L/F46L (FRT-N1303K-YFP) were generated for screening, in a similar manner as previously described for wild-type CFTR and CFTR mutants F508del, G551D and W1282X (7, 8). As indicated in Figure 1A (top), the N1303 residue is located in the nucleotide binding domain 2 (NBD2) of the CFTR protein. Figure 1A (bottom) shows a fluorescence image of transfected cells expressing N1303K-CFTR and the YFP sensor. The basis of our screening strategy is shown in Figure 1B. For a potentiator screen, following 24-hour incubation with a corrector to partially rescue N1303K-CFTR cellular misprocessing, a test compound, together with a high concentration of forskolin, was added 10 min prior to assay. The functional assay involved measurement of YFP fluorescence quenching following addition of iodide to the extracellular solution.

Figure 1. Cell line development and corrector rescue of N1303K-CFTR.

A. (top) CFTR structure showing the location of N1303K in the CFTR protein. (bottom) N1303K-CFTR-transfected FRT cells show cytoplasmic fluorescence of the YFP-H148Q/I152L/F46L sensor. B. Schematic of the assay used to identify N1303K-CFTR potentiators. C. (left) YFP fluorescence quenching data for N1303K-CFTR-expressing FRT cells incubated for 24 hours with indicated compounds and for 10 min with 20 μM forskolin and 5 μM VX-770 prior to assay. (right) Summary for iodide influx rates for indicated correctors (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–6, * P < 0.01). D. Summary for iodide influx rates for indicated potentiators (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–6, * P < 0.01). FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR were corrected by 3 μM C3 for 24 h at 37 °C, and incubated with 20 μM forskolin and potentiators for 10 min prior to addition of iodide. E. (left) Short-circuit current measured in N1303K-CFTR FRT cells showing responses to 20 μM forkolin (fsk), 5 μM VX-770 and 10 μM CFTRinh-172. Correctors (3 μM C3, 3 mM sodium butyrate) were used for 24 h at 37 °C. (right) Summary of short-circuit current data (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3, * P < 0.01). F. Chemical structure of potentiator ASP-11. Statistical analysis was done by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test: for correctors data were compared with cells treated with forskolin/VX-770 (control), and for potentiators data were compared with cells treated with forskolin/C3 (control).

A panel of known correctors was first tested in the FRT-N1303K-YFP cells to identify compounds suitable for use in screening to identify potentiators. Correctors tested included: VX-809, VX-661, C3 and C18, which target the NBD1-MSDs interface; C4, which targets NBD2-MSDs; CoPo-22, a CFTR modulator with dual corrector and potentiator function; W1282Xcorr-A23, which corrects the protein product generated by the W1282X-CFTR nonsense mutation; and sodium butyrate, a known transcriptional activator for the CMV promoter (3, 7, 9). Figure 1C shows representative YFP fluorescence quenching data (left panel) and a data summary for tested correctors (right panel). Little or no corrector activity was seen for most of the compounds, with only sodium butyrate and C3 providing significant correction. Sodium butyrate, which was used for screening here because of limited C3 availability, is likely acting as a transcriptional activator in this transfected cell system, resulting in increased cell surface expression. In addition, a panel of known potentiators was tested in the FRT-N1303K-YFP cells (Fig. 1D). Of the known potentiators, VX-770 increased channel gating activity whereas PG-01 (P2), A04 and CoPo-22 were inactive. Taken together, the data show that N1303K-CFTR does not respond well to available correctors and potentiators.

Short-circuit current was measured in the N1303K-CFTR-expressing FRT cells to validate the data obtained by the fluorescence plate reader assay, and as a quantitative measure of CFTR chloride current. Measurements were done following permeabilization of the basolateral cell membrane with amphotericin B and in the presence of a transepithelial chloride concentration gradient so that current provides a linear measure of CFTR chloride current. Without corrector, the FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR showed a small chloride current following addition of maximal forskolin and 5 μM VX-770, which was inhibited by CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 1E); correction by 3 μM C3 or 3 mM sodium butyrate increased short-circuit current by 2–3-fold, in accord with the plate reader data.

In an initial plate reader-based potentiator screen, testing of 9,600 synthetic small molecules identified six weakly active compounds; however, none of these compounds showed potentiator activity, even at high concentration (25 μM), when confirmatory short-circuit current analysis was performed. Motivated by prior experience with the W1282X nonsense CFTR mutation in which we discovered that the arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine ASP-11 (previously named W1282Xpot-A15; Fig. 1F) acted in synergy with VX-770 to restore W1282X mutant channel gating to near wild-type CFTR activity (7), we performed a potentiator synergy (‘co-potentiator’) screen.

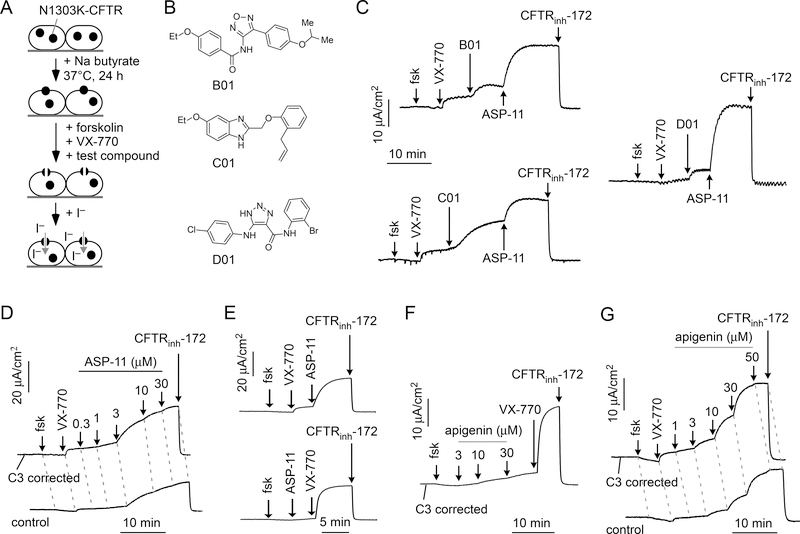

Co-potentiator screen

In order to identify potentiators that might act in synergy with VX-770, a co-potentiator screen was done in which cells were treated for 24 hours with sodium butyrate followed by acute (10 min) addition of test compounds together with 5 μM VX-770 (Fig. 2A). Screening of 16,000 compounds identified 5 active compounds in which the iodide influx was >50 % of that produced by 5 μM VX-770 plus 20 μM ASP-11. Short-circuit current measurement was done to confirm N1303K-CFTR co-potentiator activity (in the presence of VX-770) of compounds discovered by screening. These studies identified oxadiazole-benzamide B-01, phenoxy-benzimidazole C-01 and triazolo-carboxamide D-01 as active co-potentiators (Fig. 2B and 2C). In conjunction with VX-770, concentration-dependence studies revealed relatively low potency of these compounds, however, with 20 μM B-01, C-01 and D-01, producing ~20, 56, and 14 %, respectively, of the chloride current produced by 20 μM ASP-11/VX-770 (Fig. 2C). Further work focused on ASP-11 because of its substantially greater potency and efficacy compared to alternative compounds that emerged from screening.

Figure 2. Identification and characterization of N1303K-CFTR co-potentiators.

A. Assay to identify N1303K-CFTR co-potentiators in which test compound is added to butyrate-treated cells together with VX-770 and forskolin. B. Chemical structures of three novel chemical classes of co-potentiators identified from screening. C. Co-potentiator activity measured by short-circuit current in FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR showing responses to forskolin (fsk) and test compounds (25 μM). Cells were incubated with corrector C3 (3 μM) at 37°C for 24 hours before measurement. VX-770, ASP-11 (20 μM) and CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) were added as indicated. D. ASP-11 concentration-dependence measurements done in FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR, with (top) or without (bottom) C3 (3 μM) correction. E. Order-of-addition study of ASP-11 (20 μM) and VX-770 (5 μM). F. Addition of apigenin before VX-770 in FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR corrected with C3 (3 μM) for 24 hours. G. Apigenin concentration-dependence measurements, with (top) or without (bottom) C3 (3 μM) correction. Forskolin (20 μM), VX-770 (5 μM) and CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) were added as indicated, unless otherwise specified. C-G are representative of 3 or more sets of experiments.

Figure 2D shows the concentration-dependence of ASP-11 co-potentiator activity in which increasing concentration of ASP-11 were added after initial cell treatment with forskolin and 5 μM VX-770, with measurements done both with and without C3 correction. The calculated EC50 for activation of N1303K-CFTR- chloride current by ASP-11 in the presence of VX-770 was 1.9 μM. Limited N1303K-CFTR current was seen following addition of ASP-11 or VX-770 alone, but substantial current was produced following their addition of the potentiators in combination, regardless of order of addition (Fig. 2E).

We previously performed a potentiator synergy screen in FRT cells expressing the truncated W1282X-CFTR protein, testing known drugs and bioactive molecules (7). The screen identified apigenin, which showed limited activity when used alone but strong activity in the presence of VX-770. In a similar manner, testing of apigenin in FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR revealed little activity on its own, but robust co-potentiator activity in the presence of VX-770 (Fig. 2F). The EC50 for apigenin was 10.8 μM (Fig. 2G).

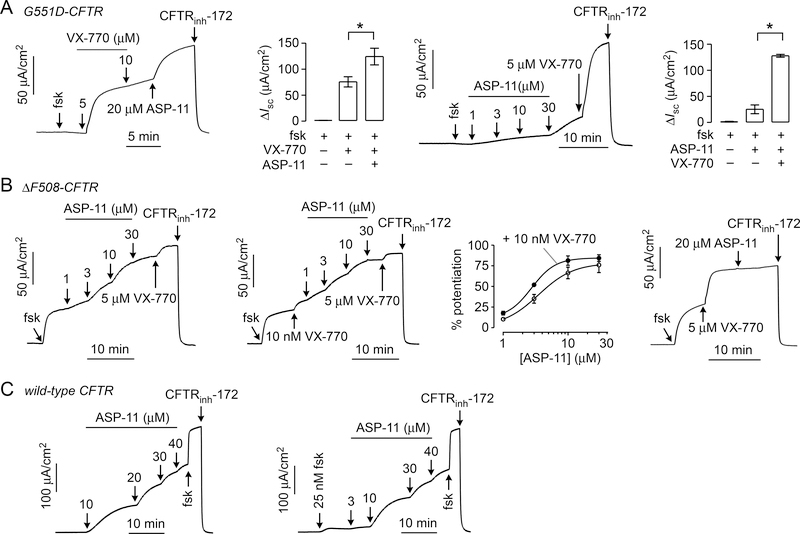

Co-potentiator testing in G551D, F508del and wild-type CFTR transfected FRT cells

ASP-11 was tested for potentiator and co-potentiator activity (absence and presence of VX-770, respectively) on CFTR mutants G551D and F508del, and on wild type CFTR. In FRT cells expressing G551D-CFTR (Fig. 3A, panel i), ASP-11 increased short-circuit current from 74 ± 11 μA/cm2 to 123 ± 19 μA/cm2 (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3, P < 0.05) after maximal VX-770 addition (Fig. 3A, ii). In the absence of VX-770 (Fig. 3A, iii), ASP-11 was a weak potentiator of G551D-CFTR (Fig. 3A, iv). Thus, ASP-11 increased G551D-CFTR activity by ~65 % more than that achieved by maximal VX-770.

Figure 3. ASP-11 potentiator activity in FRT cells expressing G551D, F508del and wild- type CFTR.

Representative short-circuit current measured in FRT cells expressing (A) G551D-CFTR, (B) F508del-CFTR and (C) wild-type CFTR, in response to forskolin (fsk), VX-770, ASP-11 and CFTRinh-172. FRT cells expressing F508del-CFTR were incubated at 27 °C for 24 hours before measurement. Forskolin (20 μM), VX-770 (5 μM) and CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) were added as indicated, unless otherwise specified. ASP-11 concentration were as indicated. For bar graphs in A, data shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n=3, * P < 0.05). For the dose-response curve in B potentiator activity is normalized to maximal VX-770 and pre-ASP-11 treatment. Short-circuit current traces in B and C representative of 3 experiments.

In VX-809 corrected FRT cells expressing F508del-CFTR, ASP-11 showed potentiator activity with EC50 of 2.9 ± 0.3 μM (Fig. 3B, i). In the presence of a sub-maximal concentration of VX-770 (Fig. 3B, ii), ASP-11 increased F508del-CFTR activity with a similar EC50 of 3.5 ± 0.5 μM (Fig. 3B, iii). The similar potencies suggest absence of potentiator synergy for F508del CFTR. With maximal VX-770, ASP-11 did not further increase chloride current (Fig. 3B, iv). ASP-11 is thus a weak potentiator of F508del-CFTR and did not potentiate in an additive manner with a maximal concentration of VX-770.

Interestingly, ASP-11 activated wild-type CFTR, albeit weakly (EC50 ~20 μM), in the absence of forskolin (Fig. 3C, i). With a submaximal forskolin concentration of 25 nM (Fig. 3C, ii), ASP-11 activated wild-type CFTR with EC50 ~10 μM, producing ~60% of maximal CFTR chloride current generated by maximal forskolin (20 μM). The activation of wild-type CFTR is an interesting observation, as known CFTR activators generally require some basal level of CFTR phosphorylation.

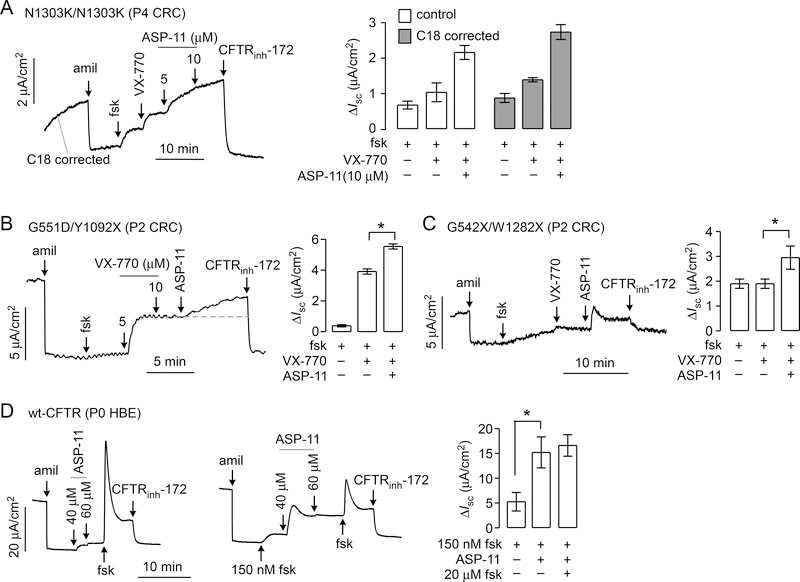

Co-potentiator activity in primary airway epithelial cell cultures

To further investigate its properties, ASP-11 was tested in airway epithelial cells from CF and non-CF subjects. These studies used conditionally reprogrammed cells (CRCs), a model that allows expansion of cell cultures derived from rare patient specimens with retention of ion transport properties (7). For these studies, epithelial cells were obtained by nasal brushings from a N1303K/N1303K homozygous CF subject, and G551D/Y1092X and G542X/W1282X heterozygous CF subjects.

In C18-treated N1303K/N1303K cultures, forskolin and VX-770 together produced a small current (1.4 ± 0.1 μA/cm2) that was increased by ~2-fold by ASP-11 (2.7 ± 0.4 μA/cm2) (Fig. 4A). Similar activity was seen in N1303K/N1303K cultures in the absence of corrector. The results indicated that ASP-11 co-potentiation effect is corrector-independent, which was also seen in the FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR (Fig 2D). Interestingly, C3-corrected N1303K/N1303K cultures showed reduced current as compared to cultures in the absence of corrector (data not shown). The results on nasal cells are consistent with those found in FRT cells expressing N1303K-CFTR with regard to VX-770 and ASP-11 effects, and differences observed for corrector activity likely represents cell-type specific influences, as observed for F508del-targeted correctors (10).

Figure 4. Functional assays in primary human airway epithelial cell cultures.

A. (left) Short-circuit current in airway epithelial cells (passage P4 CRCs) from a homozygous N1303K-CFTR cystic fibrosis subject in response to 10 μM amiloride, 20 μM forskolin (fsk), 5 μM VX-770, 5 and 10 μM ASP-11, and 10 μM CFTRinh-172. Cells were corrected with 5 μM C18 for 24 hr prior to measurement. (right) Short-circuit current summary (mean ± S.E.M., n=3, *P < 0.05). B. (left) Short-circuit current in airway epithelial cells (passage P2 CRCs) from a heterozygous G551D/Y1092X cystic fibrosis subject in response to 10 μM amiloride, 20 μM forskolin (fsk), indicated concentration of VX-770, 30 μM ASP-11 and 10 μM CFTRinh-172. (right) Short-circuit current summary (mean ± S.E.M., n=5, *P < 0.05). C. (left) Short-circuit current from a heterozygous W1282X/G542X-CFTR cystic fibrosis subject (P2 CRCs from nasal brushing) in response to 10 μM amiloride, 20 μM forskolin, 5 μM VX-770, 30 μM ASP-11 and 10 μM CFTRinh-172. (right) Short-circuit current summary (mean ± S.E.M., n=4, *P < 0.05). Cells were incubated for 24 h with 3 μM VX-809 prior to experiments. D. (left) Short-circuit current in primary culture of non-CF human bronchial epithelial cells in response to 10 μM amiloride, indicated concentration of forskolin and ASP-11, and 10 μM CFTRinh-172. Right: Short-circuit current summary (mean ± S.E.M., n=3, *P < 0.05).

In G551D/Y1092X cultures, forskolin alone produced limited current (0.4 ± 0.1 μA/cm2), which was greatly increased following addition of VX-770 (3.9 ± 0.3 μA/cm2), as expected for G551D-CFTR (Fig. 4B). ASP-11 addition further increased G551D-CFTR current to 5.6 ± 0.3 μA/cm2, in agreement with data in the G551D-CFTR-expressing FRT cells showing that ASP-11 increased current beyond that produced by maximal VX-770. Y1092X-CFTR is unlikely to contribute to the signal because of the location of Y1092 in membrane spanning domain 2 of CFTR, a location that is critical to appropriate folding and maturation (11).

In G542X/W1282X cultures, we expect no channel activity from the G542X mutation (11). The W1282X mutation is predicted to generate a truncated protein constituting most (~85 %) of the full-length wildtype CFTR (7). W1282X-CFTR transcript was observed in nasal epithelial cells of homozygous W1282X CF subjects with 30–80% abundance compared with that of wildtype CFTR in non-CF subjects (7) and references therein). Following correction with 3 μM VX-809 for 24 hour at 37 °C, forskolin and VX-770 produced a small current in the G542X/W1282X cultures (1.9 ± 0.4 μA/cm2) (Fig. 4C). ASP-11 showed modest, albeit significant co-potentiator activity that was inhibited by CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, a rapid current increase was seen in G542X/W1282X cells following ASP-11 addition as compared to a slower current increase in the G551D/Y1052X cells; this difference may be due to the kinetics of ASP-11 binding or induced CFTR conformational changes in the distinct mutants.

Last, ASP-11 was tested in a non-CF primary bronchial epithelial cell culture. As shown (Fig. 4D, left) ASP-11 weakly activated wild-type CFTR in the absence of forskolin, as seen in FRT cells expressing wild-type CFTR. In the presence of a submaximal concentration of forskolin (100 nM) (Fig. 4D, middle), a high concentration of ASP-11 produced about 50% of the current of fully activated wild-type CFTR (Fig. 4D, right).

Structure-activity analysis of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridines

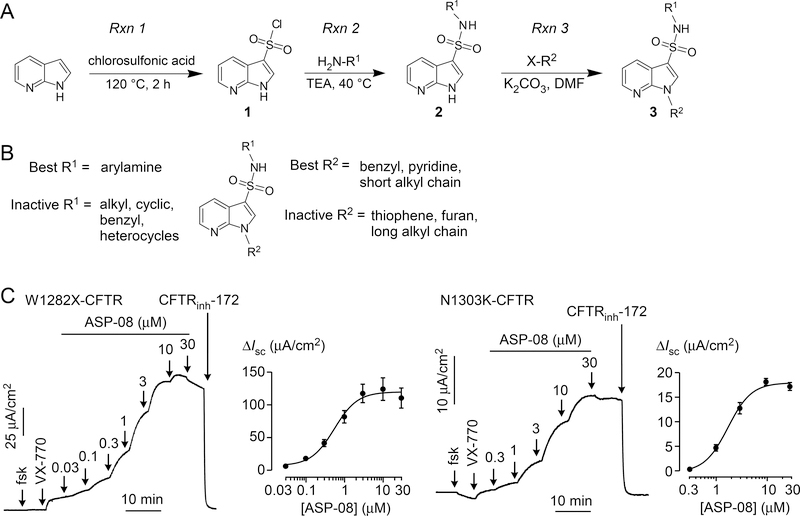

To enable investigation of potentiator structure-activity determinants, a synthetic scheme was devised for the efficient synthesis and diversification of the arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine scaffold (Fig. 5A). Briefly, commercial 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine was converted to 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine-3-sulfonyl chloride (1; Rxn 1) by treatment with excess chlorosulfonic acid (neat; 120 °C) (12). The crude product of this reaction, obtained by careful quenching with water and collection of product by filtration, was used directly in the next step (Rxn 2). Sulfonyl chloride 1, dissolved in dichrolomethane, was treated with the amine (H2NR; one equivalent) and trimethylamine (slight excess), initially at room temperature followed by warming to 60 °C. Solvent removal delivered sulfonamide 2 (used directly in the next step without further purification), which was dissolved in dimethylformamide and treated consecutively with potassium carbonate and the N-alkylating reagent (X-R1). Room temperature stirring overnight followed by addition of water and extraction with ethyl acetate delivered the targeted arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine, which was purified by flash column chromatography to yield 3.

Figure 5. Synthesis and structure-activity analysis of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine co-potentiators.

A. General synthetic scheme. Rxn 1: conversion of 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine to 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine-3-sulfonyl chloride (1). Rxn 2: Condensation of chlorosulfonic acid 1 with primary amine (H2NR1) to generate sulfonamide 2. Rxn 3: N-alkylation of 2 to generate final arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine. B. Structural determinants of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine potentiator activity. C. Short-circuit current in FRT cells expressing W1282X-CFTR (left) and N1303K-CFTR (right) showing responses to 20 μM forskolin (fsk), 5 μM VX-770, indicated concentrations of ASP-08, and 10 μM CFTRinh-172 (representative of 3 sets of experiments).

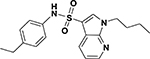

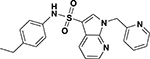

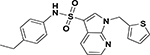

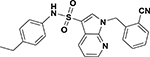

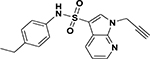

Figure 5B summarizes the structure determinants for the synthesized compounds reported in Table 1 (compounds with ASP-xx designations). In general, the substituents on the pyrrolopyridine (7-aza-indole) ring strongly influenced co-potentiator activity. The nitrogen in the pyrrolopyridine (7-aza) is crucial as the 4-aza analog (ASP-20) and the benzene analog (ASP-24) were inactive. Benzyl, pyridine rings and short alkyl chain on the indole nitrogen (R2) were best for activity (ASP-27, ASP-08, ASP-11). Longer alkyl chain (>6 carbons) reduced activity (ASP-12). Aryl-amines including aniline (R1) appears to be best for activity (ASP-08), whereas aliphatic-amines (ASP-38) were inactive. In general, potency and activity for W1282X and N1303K co-potentiator activity of the mutants were similar (data not shown), suggesting a common binding site on the mutant CFTR protein prior to tryptophan at position 1282.

Table 1.

Chemical structures and co-potentiator activity of selected arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridines. EC50 from plate reader concentration-dependence measurements.

| Compound | Chemical structure | W1282X-CFTR EC50 (μM) | N1303K-CFTR EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

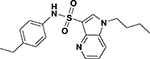

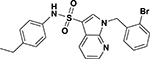

| ASP-08 |  |

0.6 | 1.7 |

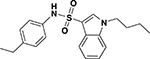

| ASP-11 |  |

1.0 | 1.9 |

| ASP-12 |  |

12 | 15 |

| ASP-20 |  |

inactive | inactive |

| ASP-24 |  |

inactive | inactive |

| ASP-26 |  |

1.3 | 3.5 |

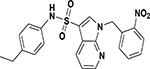

| ASP-27 |  |

0.7 | 2.5 |

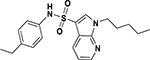

| ASP-28 |  |

1.0 | 3.5 |

| ASP-33 |  |

3.0 | 7.2 |

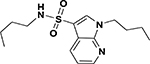

| ASP-38 |  |

inactive | inactive |

| ASP-41 |  |

inactive | inactive |

Short-circuit current measurements were done of the most potent analog, ASP-08. Figure 5C shows data in W1282X-CFTR and N1303K-CFTR expressing FRT cells. Following forskolin and VX-770, concentration-dependent increases in current were seen following ASP-08 additions, with total current inhibited by CFTRinh-172. Calculated EC50 values were 0.55 μM and 1.7 μM for W1282X-CFTR and N1303K-CFTR, respectively.

DISCUSSION

There remains an unmet need for drugs to treat CFTR mutations that do not respond well to available correctors and potentiators, including the missense mutation N1303K and the nonsense mutation W1282X (1). In FRT cell models generated using the Flp recombinase, VX-770 was previously shown to be ineffective in activating N1303K-CFTR in the absence of correction (4). Similarly, in primary HBE cultures and in rectal organoids derived from CF subjects with the N1303K-CFTR mutation, no CFTR-dependent function was observed in response to correctors (including VX-809, and C1-C18) and potentiators (including the pan-specific potentiator genistein and VX-770) (6, 13, 14). In HEK293 cells, a variety of correctors (including C3, C4, C18, CFFT 002 and 003) were found to enhance N1303K-CFTR folding, though functional responses were not assessed (5). Here, we found that VX-770 can enhance N1303K-CFTR-dependent current in a transfected FRT cell model in the absence of correction, and that this response is further increased by the corrector C3 or butyrate treatment, and a co-potentiator. The most likely explanation for the difference between our study and those of Van Goor and colleagues, both of which utilized FRT cells, is differences in N1303K-CFTR expression level, as observed for other CFTR mutants including W1282X-CFTR (9). Butyrate is known to increase gene expression from cytomegalovirus promoters in addition to enhancing mutant CFTR folding. Together, these studies suggest that N1303K-CFTR is refractory to currently available CFTR modulators, but that appropriate corrector and potentiator combinations could restore N1303K-CFTR function.

For CFTR nonsense mutations, drug development has focused on promoting read-through of premature stop codons to generate full-length CFTR, though the most promising candidate, Ataluren (PTC Therapeutics), failed phase III clinical trials (1). More recently, our group identified ASP-11 (previously referred to as W1282Xpot-A15) as a potentiator of the W1282X-CFTR protein product (CFTR1281) (7). Importantly, combination of ASP-11 and VX-770 resulted in marked activation of CFTR1281 to restore channel function in transfected FRT cells. Unfortunately, despite significant efforts, a variety of pharmacological approaches, including VX-809-mediated correction and VX-770/ASP-11-mediated potentiation, were ineffective at activating CFTR channel activity in primary nasal epithelial cells derived from a single homozygous W1282X-CFTR subject. In contrast, in the present study cells from a CF subject with G542X/W1282X mutations produced significant channel activity after addition of VX-770 and ASP-11 that was by inhibited by CFTRinh-172. In conjunction with studies in FRT cells, this finding supports the use of correctors and potentiators for cystic fibrosis caused by premature termination codons that truncate the carboxy-terminus of CFTR.

The currently available therapy for cystic fibrosis caused by the G551D-CFTR mutation, VX-770/Ivacaftor, has been a transformative medicine; however, it does not completely restore CFTR-dependent chloride channel activity in the lung (15). The open probability of G551D-CFTR after VX-770 has been reported to be ~0.12–0.15, suggesting that further increase is possible as the open probability of wild-type CFTR is ~0.4 (16, 17). A recent study reported that the novel potentiator GLPG1837, which is structurally similar to the potentiator P5 discovered by our group, increases G551D-CFTR current by ~3-fold compared to VX-770 (18, 19). ASP-11 increased G551D-CFTR current by ~45–65% above that produced by maximal VX-770 as measured in G551D-CFTR transfected FRT cells and G551D/Y1092X CFTR primary human airway cell cultures. The Y1092X mutation is rare and associated with CF lung disease and pancreatic insufficiency (20). Previous studies (11, 21) suggested that synthesis of a complete membrane spanning domain 2 is required for CFTR cell surface presentation and channel activity. For example, CFTR-1097X showed marked degradation and no cell surface expression, whereas cell surface expression of CFTR-1174X was similar to wild-type CFTR (11, 21). Therefore, Y1092X CFTR is likely non-functioning so that the current observed from G551D/Y1092X is most likely entirely from G551D-CFTR.

To date, relatively little is known about mechanism of action of CFTR potentiators, although three distinct classes have been identified: ATP analogues such as 2’-deoxy-N6-(2-phenylethyl)-adenosine-5’-O-triphosphate (dPATP) and N6-(2-phenylethyl)-ATP (PATP) that associate with the CFTR ATP-binding site; compounds such as VX-770 that are proposed to target CFTR transmembrane domains to stabilize the open channel state; and compounds that promote CFTR channel opening by unspecified mechanisms (19, 22, 23). In patch-clamp studies Yeh et al., (2017) demonstrated that VX-770 and GLPG1837 likely activate G551D-CFTR by binding to the same site. Given that enhanced activation of G551D-CFTR and in other mutant CFTRs is seen with combination of VX-770 and ASP-11, in both transfected FRT cell models and primary airway epithelial cell cultures, these compounds likely target distinct sites. The very rapid increase in chloride current seen upon addition of ASP-11 suggests action as a potentiator of channel gating rather that action by increasing mutant CFTR trafficking to cell surface or by stabilizing mutant CFTRs in the plasma membrane. Given the limitations of VX-770, co-potentiators may represent a useful therapeutic approach for CF caused by the G551D-CFTR mutation as well as other more rare mutations.

Activation of wild-type CFTR by ASP-11 is remarkable as most potentiators require some basal level of phosphorylation for activity. Whereas adequate basal cAMP levels and CFTR phosphorylation appear to be present in native cells such as airway epithelial cell cultures, cAMP and basal CFTR phosphorylation are very low in FRT cells. We previously identified an aminocarbonitrile-pyrazole CFTR activator, Cact-A1, that did not require basal CFTR phosphorylation (24). As with the arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine ASP-11, Cact-A1 was active in FRT cells expressing wild-type CFTR as well as in non-CF airway epithelial cells. Cact-A1 also showed potentiator activity with G551D-CFTR and F508del-CFTR. CFTR activators that do not require cAMP elevation may have an unconventional activation mechanism, which remains to be elucidated, and may be advantageous for some difficult-to-treat mutant CFTRs.

The measurements in primary cultures of human airway epithelial cells supported the utility of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine in CF-relevant cells. Though correctors identified from screens in heterologous cell systems are often inactive in primary human airway cells (7, 10), potentiator activity should generally be cell context-independent provided that therapeutic concentrations can accumulate in cell cytoplasm. ASP-11 showed function in CF airway epithelial cells with the N1303K, G551D and W1282X mutations, as well as in non-CF airway epithelial cells. Co-potentiator activity seen for N1303K is a remarkable finding because this CFTR mutation is generally believed to be refractory to modulator therapy. Co-potentiator activity for G542X/W1282X is interesting because of our prior data, as described above, showing no activity in airway epithelial cells from a homozygous W1282X CF subject following treatment with multiple different corrector and potentiator combinations (7). As nonsense-mediated decay in the previously studied W1282X homozygous subject was unlikely to explain the absence of corrector/potentiator effects (CFTR transcript ~70 % wild-type transcript), alternative, yet to be elucidated patient-specific factors may be responsible.

The increase in short-circuit current following corrector and co-potentiator treatment seen in the N1303K homozygous conditionally reprogrammed HNE cells in Fig. 4A is suggestive of potential clinical benefit, but with many caveats. A useful parameter that has been used to predict potential clinical benefit is the percentage of short-circuit current measured in CF vs. non-CF airway epithelial cell cultures; for example, VX-809 increased current in cultured F508del-HBE cells to approximately 14% of that measured in non-CF HBE cells (26), which is generally considered in a range of potential clinical benefit. In a prior study (27), data from conditionally reprogrammed HNE cells from 5 non-CF subjects showed ~60 % of the maximal forskolin-stimulated increase in short-circuit current compared to conditionally reprogrammed HBE cells, with stable functional phenotype up to 10 passages. Our lab (Fig. 4D here, and (7, 25)) has reported in HBE cells a forskolin-stimulated increase in short-circuit current of ~20–25 μA/cm2. Therefore, HNE cells are estimated to have a maximal forskolin-stimulated increase in short-circuit current of ~12–15 μA/cm2 (i.e. 60 % of 20–25 μA/cm2). The forskolin/VX-770/ASP-11 increase in short-circuit current in conditionally reprogrammed HNE cells with N1303K/N1303K, G551D/Y1092X and W1282X/G542X mutations were 2.7, 5.6, 2.9 μA/cm2, respectively, which correspond to ~18%, 31% and 19%, respectively, of estimated values in HNE cells. However, we note many caveats in this determination. In addition to extrapolations made comparing nasal versus bronchial, and non-passaged versus conditionally reprogrammed passaged cells, it is assumed that the well-differentiated cell cultures grown for many weeks recapitulate the airway cell function and responses in their native environment in which there are many cells and an inflammatory environment, and there can be significant variation in data from different CF subjects with the same genotype and in different non-CF controls. In addition, the high concentrations of drug and forskolin used in the cell culture studies are probably not representative of drug and cAMP concentrations in airway cells in vivo. Short-circuit current measurements on additional N1303K homozygous CF subjects should be informative, when directly comparing to similarly obtained and cultured cells from multiple non-CF subjects.

Synthetic chemistry done for the arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridine analogs provided information on the structural determinants of co-potentiator activity and compounds with improved potency. Analogs with N-pyridine and phenyl-sulfonamide gave best potency, though further synthetic efforts exploring substituents on the pyridine and phenyl-sulfonamide might further improve potency. There is very little prior literature on biological activity of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridines. Some analogs, though with very different substituents than compounds studied here, were reported as cannabinoid agonists for therapy for pain and nausea (28). The most potent analog synthesized here, ASP-08, has favorable drug-like properties including the presence of multiple hydrogen bond acceptors, molecular mass of 392 Da, aLogP of 3.7, and topological polar surface area of 74 Å2. These properties, and the increased potency of arylsulfonamide-pyrrolopyridines, contrast with other compounds, such as curcumin and genistein that also act in synergy with VX-770 to potentiate mutant CFTR (29, 30).

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence for the utility of a co-potentiator approach for therapy of CF caused by the N1303K mutation, including significant enhancement of chloride current in nasal epithelial cells from a N1303K homozygous CF subject. This study also shows that the co-potentiator approach can increase chloride current in a CF subject with a W1282X allele. The co-potentiator strategy might thus be broadly useful for CF in general, since chloride current was significantly increased in nasal epithelial cells from CF subjects with relatively common (G551D) and rare (N1303K, W1282X) mutations. Using potentiator combinations to treat CF is a logical extension of the two-corrector plus one-potentiator treatment currently in clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

VX-809, VX-661, VX-770 and CFTRinh-172 were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Boston, MA). Correctors C3 and C18 were obtained from the CFTR Compound Program, The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Inc., which is administered at the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; PG01, A4, CoPo-22, C4 and W1282Xcorr-A23 were obtained from an in-house repository of CFTR modulators. For screening, approximately 20,000 diverse drug-like synthetic compounds (>90% with molecular size 250–500 Da; ChemDiv Inc., San Diego, CA) were tested. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated.

Complementary DNA construct

The N1303K-CFTR complementary DNA (cDNA) was initially cloned in pcDNA3.1/Zeo(+) (Invitrogen), essentially as described in ref. (7), using a gBLOCK gene fragment (Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville, IA) introduced at a unique BstXI site to generate the 3’-region of CFTR with inclusion of the N1303K mutation. For generation of stable cell lines, the N1303K-CFTR cDNA was subcloned into pIRESpuro3 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) using NheI and NotI restriction sites.

Cell culture models

Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) cells were cultured in Kaign’s modified Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 18 μg/ml myoinositol, and 45 μg/ml ascorbic acid. For N1303K-CFTR studies, FRT cells expressing EYFP-H148Q/I152L/F46L (using the FELIX third generation feline immunodeficiency lentiviral system deposited at Addgene by Garry Nolan, plasmid 1728) were transfected with pIRESpuro3-N1303K-CFTR and clonal cell lines were isolated after inclusion of 0.15 μg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen) in cell culture medium. FRT cell lines expressing wildtype CFTR, F508del-CFTR, G551D-CFTR and W1282X-CFTR were described and cultured as previously reported (7, 8).

Primary human bronchial and nasal epithelial cell cultures

Non-CF human bronchial surface epithelial (HBE) cells were isolated from lung explants and then cultured on Snapwell inserts (Corning, New York) for 21–28 days at an air-liquid interface as described (7). Nasal epithelial cells were obtained by mucosal brushing from three CF subjects (genotypes N1303K/N1303K, G542X/W1282X and G551D/Y1092X) and conditional reprogramming to increase cell numbers was performed as described (7). For experiments, second-passage, reprogrammed nasal epithelial cells were cultured for 28 days under the same conditions as the human bronchial epithelial cells. All protocols involving the collection and use of human tissues and cells were reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

High-throughput screening

High-throughput screening used a semi-automated screening platform (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) essentially as described (7). For the potentiator screen, FRT cells expressing N1303K and YFP were plated in 96-well black-walled, clear-bottom tissue culture plates (Corning) at a density of 20,000 cells/well and grown for 24 h at 37 °C to ~90% confluency. Cells were treated with 3 mM sodium butyrate for 24 hours. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, and incubated for 10 min in 100 μl of PBS containing forskolin (10 μM) and test compounds (25 μM) prior to assay of CFTR activity. All plates in the potentiator screen contained wells with positive (5 μM VX-770) and negative (DMSO) controls. A co-potentiator screen was done similarly except that cells were incubated with forskolin (10 μM) and VX-770 (5 μM) prior to addition of test compound. Assays were done using a BMG Labtech FLUOstar OMEGA plate reader (Cary, NC) over 12 s with initial fluorescence intensity recorded for 1 s prior to addition of 100 μl of NaI-substituted PBS (137 mM NaCl replaced with NaI). Initial iodide influx was computed from fluorescence intensity by single exponential regression.

Short-circuit current measurements

Short-circuit current was measured on cells cultured on permeable supports (Corning) as described (7). For FRT cells, the basolateral membrane was permeabilized with 250 μg/ml amphotericin B, and experiments were done using a HCO3−-buffered system (in mM: 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 Hepes, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, pH 7.4) with a basolateral to apical chloride gradient (generated by replacing 60 mM NaCl with sodium gluconate in the apical solution). For primary cultures of human airway epithelial cells, short-circuit current was measured using symmetrical HCO3−-buffered solutions (containing 120 mM NaCl). Cells were equilibrated with 95% O2, 5% CO2 and maintained at 37 °C. Hemichambers were connected to a DVC-1000 voltage clamp (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL) via Ag/AgCl electrodes and 3 M KCl agar bridges for recording of the short-circuit current.

Data analysis

GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. EC50 values were determined by non-linear regression to a single site inhibition model. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired Student’s t test, and values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

General synthesis chemistry procedures

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated and used without further purification. Analytical thin layer chromatography was carried out on precoated plates (silica gel 60 F254, 250 μm thickness) and visualized with UV light. Flash chromatography was performed using 60 Å, 32–63 μm silica gel (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Mass). Concentration in vacuo refers to rotary evaporation under reduced pressure. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 400, 600, or 800 MHz at ambient temperature with acetone-d6, DMSO-d6, or CDCl3 as solvents. 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 100, 150, or 200 MHz at ambient temperature. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the residual solvent peak. High-resolution mass spectra were acquired on an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA), operating in the positive ion mode. Samples were introduced into the source via loop injection at a flow rate of 200 μL/min in a solvent system of 1:1 acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid. Mass spectra were acquired using Xcalibur, version 2.0.7 SP1 (ThermoFinnigan). The spectra were externally calibrated using the standard calibration mixture and then calibrated internally to <2 ppm with the lock mass tool. Analytical data are reported in Supplemental Data.

1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine-3-sulfonyl chloride (1) – Rxn 1:

1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine (3 g, 30 mmol) was carefully added in small portions to a round bottom flask containing chlorosulfonic acid (5 mL, 75 mmol) with stirring at room temperature (note - the mixing is initially exothermic and generates a large amount of white fumes). Additional chlorosulfonic acid (5 mL, 75 mmol) was then added to the mixture in one portion. The open flask was next placed in an oil bath at 120 °C and stirred for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was poured into water (200 mL) and the resulting precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration and then washed with copious amounts of water. The resulting tan product (sulfonyl chloride 1) was used directly in the next step without further purification.

General synthesis of 3-sulfonamidyl-7-azaindole (2) – Rxn 2:

Sulfonyl chloride 1 (216 mg, 1 mmol) was dissolved in dichrolomethane (100 mL) in a round bottom flask. Amine (1 mmol) and triethylamine (150 μL, 1.07 mmol) were added to the reaction vessel with stirring at room temperature and the resulting reaction mixture was heated at 60 °C with stirring for 1 h. Upon cooling, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting sulfonamide (2) was used directly in the next step without further purification.

General synthesis of N-substituted 3-sulfonamidyl-7-azaindole (3) – Rxn 3:

Dimethylformamide (50 mL) and potassium carbonate (125 mg, 0.9 mmol) were added in one portion to a flask containing 3-sulfonamidyl-7-azaindole (2). N-Alkylating reagent (X-R1; 1 mmol) was added, the flask opening was covered with paraffin film, and the mixture stirred at room temperature overnight. Water (200 mL) was added to the reaction mixture and the resulting solution was extracted three times with ethyl acetate (100 mL). The combined extracts were washed with water (100 mL; three times) and brine. After drying over MgSO4, the solution was filtered and the solvent removed in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by flash column chromatography using a gradient elution of ethyl acetate and hexane to yield sulfonamidylazaindole 3.

Analytical data – ASP-08.

1H NMR (600 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.57 – 8.51 (m, 1H), 8.34 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.61 – 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.24 – 7.18 (m, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.02 – 6.93 (m, 5H), 5.61 (s, 2H), 2.52 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.13 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, cdcl3) δ 155.30, 148.96, 147.08, 144.84, 141.59, 137.73, 134.21, 133.01, 128.66, 128.46, 123.10, 122.60, 122.11, 118.27, 116.82, 112.43, 49.48, 28.18, 15.50. HRMS calcd 393.1385 found 393.1372. ASP-11. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 8.39 (dd, J = 4.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.15 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.06 – 6.94 (m, 4H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.55 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.84 – 1.72 (m, 2H), 1.30 – 1.21 (m, 2H), 1.25 – 1.12 (t, 3H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.88, 144.40, 141.74, 134.21, 132.79, 128.63, 128.52, 122.56, 118.04, 116.93, 110.91, 45.07, 31.88, 28.21, 19.74, 15.56, 13.55. HRMS calcd 358.1589 found 358.1590.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK72517, DK75302, DK101373, EB00415 and EY13574, and grants from the Emily’s Entourage Catalyst for a Cure Program, Cystic Fibrosis Research Inc. and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. The authors thank Robert Bridges, Ph.D., Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, for providing compounds through the CFTR Compound Program, CFFT. This compound repository is supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics). The authors also thank Drs. Vincenzina Lucidi and Fabiana Ciciriello (Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù) for providing N1303K/N1303K nasal epithelial cells, and Amber A. Rivera for performing cell culture to support this study.

Footnotes

Competing interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elborn JS (2016) Cystic Fibrosis. Lancet 388:2519–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabeh WM, Bossard F, Xu H, Okiyoneda T, Bagdany M, Mulvihill CM, Du K, di Bernardo S, Liu Y, Konermann L, Roldan A and Lukacs GL (2012) Correction of both NBD1 energetics and domain interface is required to restore ΔF508 CFTR folding and function. Cell 148:150–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phuan PW, Veit G, Roldan A, Finkbeiner WE, Lukacs GL and Verkman AS (2014) Synergy-based small-molecule screen using a human lung epithelial cell line yields ΔF508-CFTR correctors that augment VX-809 maximal efficacy. Mol. Pharmacol 86:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Goor F, Yu H, Burton B and Hoffman BJ (2014) Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J. Cystic Fibrosis 13:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapino D, Sabirzhanova I, Lopes-Pacheco M, Grover R, Guggino WB and Cebotaru L (2015) Rescue of NBD2 mutants N1303K and S1235R of CFTR by small-molecule correctors and transcomplementation. PlOS One 10(3)::e0119796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekkers JF, Gogorza Gondra RA, Kruisselbrink E, Vonk AM, Janssens HM, de Winter-de Groot KM, van der Ent CK and Beekman JM (2016) Optimal correction of distinct CFTR folding mutants in rectal cystic fibrosis organoids. Eur. Respir. J 48:451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haggie PM, Phuan P-W, Tan JA, Xu H, Avramescu RG, Perdomo D, Zlock L, Nielson DW, Finkbeiner WE, Lukacs GL and Verkman AS (2017) Correctors and potentiators rescue function of the truncated W1282X-cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) translation product. J. Biol. Chem 292:771–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedemonte N, Sonawane SD, Taddei A, Hu J, Zegarra-Moran O, Suen YF, Robins LI, Dicus CW, Willenbring D, Nantz MH, Kurth MJ, Galietta LJ and Verkman AS (2005) Phenylglycine and sulfonamide correctors of defective delta F508 and G551D cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride-channel gating. Mol. Pharmacol 67:1979–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe SM, Varga K, Rab A, Bebok Z, Byram K, Li Y, Sorscher EJ and Clancy JP (2007) Restoration of W1282X CFTR activity by enhanced expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 37:347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedemonte N, Tomati V, Sondo E and Galietta LJ (2010) Influence of cell background on pharmacological resuce of mutant CFTR. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 298:C866–C874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du K and Lukacs GL (2009) Cooperative assembly and misfolding of CFTR domains in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:1903–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu R-J, Tucker JA, Zinevitch T, Kirichenko O, Konoplev V, Kuznetsova S, Sviridov S, Pickens J, Tandel S, Brahmachary E, Yang Y, Wang K, Freel S, Fisher S, Sullivan A, Zhou J, Stanfield-Oakley S, Greenberg M, Bolognesi D, Bray B, Koszalka B, Jeffs P, Khasanov A, Ma Y-A, Jeffries C, Liu C, Proskurina T, Zhu T, Chucholowski A, Li R and Sexton C (2007) Design and synthesis of human immunodeficiency virus entry inhibitors: sulfonamide as an isostere for the a-ketoamide group. J. Med. Chem 50:6535–6544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atawade NT, Uliyakina I, Farinha CM, Clarke LA, Mendes K, Sole A, Pastor J, Ramos MM and Amaral MD (2015) Measurements of functional responses in human primary lung cells as a basis for personalized therapy for cystic fibrosis. EBioMedicine 2:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekkers JF, Berkers G, Kruisselbrink E, Vonk A, de Jonge HR, Janssens HM, Bronsveld I, van de Graaf EA, Nieuwenhuis EE, Houwen RH, Vleggaar FP, Escher JC, de Rijke YB, Majoor CJ, Heijerman HG, de Winter-de Groot KM, Clevers H, van der Ent CK and Beekman JM (2016) Characterizing responses to CFTR-modulating drugs using rectal organoids derived from subjects with cystic fibrosis. Sci. Trans. Med 8(344):344ra84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, Tullis E, Bell SC, Drevinek P, Griese M, McKone EF, Wainwright CE, Konstan MW, Moss R, Ratjen F, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Rowe SM, Dong Q, Rodriguez S, Yen K, Ordonez C, Elborn JS; VX08–770-102 Study Group (2011) A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N. Engl. J. Med 365:1663–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PDJ, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, HJoubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, MccCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JC, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M and Negulescu P (2009) Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:18825–18830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H, Burton B, Huang C-J, Worley J, Cao D, Johnson JP Jr., Urrita A, Joubran J, Seepesaud S, Sussky K, Hoffman BJ and Van Goor F (2012) Ivacaftor potentiation of multiple CFTR channels with gating mutations. J. Cyst. Fibros 11:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Plas SE, Kelgtermans H, De Munck T, Martina SLX, Dropsit S, Quinton E, De Blieck A, Joannesse C, Tomaskovic L, Jans M, Christophe T, Van der Aar E, Borgonovi M, Nelles L, Gees M, Stouten PFW, Van Der Schueren J, Mammoliti O, Conrath K and Andres MJ (2018) Discovery of N-(3-carbamoyl-5,5,7,7-tetramethyl-5,7-dihydro-4H-thieno[2,3-c]pyran-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxamide (GLPG1837), a novel potentiator which can open class III mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channels to a high extent. J. Med. Chem 61:1425–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh H-I, Sohma Y, Conrath K and Hwang T-C (2017) A common mechanism for CFTR potentiators. J. Gen. Physiol 149:1105–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozon D, Zielenski J, Rininsland F and Tsui LC (1994) Identification of four new mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene: I148T, L1077P, Y1092X, 2183AA->G. Hum. Mutat 3:330–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui L, Aleksandrov LA, Chang X-B, Hou Y-X, He L, Hegedus T, Gentzsch M, Aleksandrov AA, Balch W and Riordan JR (2007) Domain interdependence in the biosynthetic assembly of CFTR. J. Mol. Biol 365:981–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang T-C and Sheppard DN (1999) Molecular pharmacology of the CFTR Cl− channel. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 20:448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z, Wang X, Li M, Sohma Y, Zou X and Hwang T-C (2005) High affinity ATP/ADP analogues as new tools for studying CFTR gating. J. Gen. Physiol 569:447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Namkung W, Park J, Seo Y and Verkman AS (2013) Novel amino-cabonitrile-pyrazole identified in a small molecule screen activates wild-type and ΔF508 cystic fibrosis conductance regulator in the absence of a cAMP agonist. Mol. Pharmacol 84:384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veit G, Avramescu R, Perdomo D, Phuan P-W, Bagdany M, Apaja PM, Borot F, Szollosi D, Wu YS, Finkbeiner WE, Hegedus T, Verkman AS and Lukacs GL (2014) Some gating potentiators, including VX-770, diminishes ΔF508-CFTR functional expression. Sci. Trans. Med 6(246):246ra97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhusi PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olsen ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M and Negulescu PA (2011) Correction of F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by investigational drug VX-809. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 15:18843–18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avramescu RG, Kai Y, Xu H, Bidaud-Meynard A, Schnur A, Frenkiel S, Matouk E, Viet G and Lukacs GL (2017) Mutation-specific downregulation of CFTR2 variants by gating potentiators. Hum. Mol. Genet 26:4873–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowden MJ and Williamson JPB, WO Patent 2014167530 A1 20141016. 2014.

- 29.Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA and Aggarwal BB (2007) Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol. Pharmaceutics 4:807–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dekkers JF, Van Mourik P, Vonk AM, Kruisselbrink E, Berkers G, de Winter-de Groot KM, Janssens HM, Bronsveld I, van der Ent CK, de Jonge HR and Beekman JM (2016) Potentiator synergy in rectal organoinds carrying S125N, G551D, or F508del CFTR mutations. J. Cyst. Fibros 15:568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]