Summary

Objective

To explore the role of miR‐181b in alterations of apoptosis and autophagy in the kainic acid (KA)‐induced epileptic juvenile rats via modulating TLR4 and P38/JNK signaling pathway.

Methods

Dual‐luciferase reporter assay was performed to testify the targeting relationship between miR‐181b and TLR4. After intracerebroventricular injection (i.c.v.) of KA, rats were injected with miR‐181b agomir and TLR4 inhibitor (TAK‐242). The TLR‐4 activator lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was also administered into rats immediately after injection with miR‐181b agomir. Quantitative real‐time‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) was used for detections of miR‐181b and TLR4 expressions, hematoxylin‐eosin (HE) and Nissl staining for observation of the hippocampus morphological changes, and TUNEL staining for apoptosis analysis. Moreover, western blot was determined to detect TLR4 and P38/JNK pathway proteins, as well as autophagy‐ and apoptosis‐related proteins.

Results

TLR4 was identified as a direct target of miR‐181b using Dual‐luciferase reporter assay. KA rats injected with miR‐181b agomir or TAK‐242 had improved learning and memory abilities, reduced seizure severity of Racine’s scale, and lessened neuron injury. Additionally, miR‐181b agomir or TAK‐242 could significantly inhibit P38/JNK signaling, decrease LC3II/I, Beclin‐1, ATG5, ATG7, ATG12, Bax, and cleaved caspases‐3, but increase p62 and Bcl‐2 expression. No significances were found between KA group and KA + miR‐181b + LPS group.

Conclusion

MiR‐181b could inhibit P38/JNK signaling pathway via targeting TLR4, thereby exerting protective roles in attenuating autophagy and apoptosis of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, epilepsy, miR‐181b, P38/JNK, TLR4

1. INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy, referred to a heterogeneous group of chronic neurological disorders, with the characteristics of various epileptic seizure types, brings about much social discrimination, owing to the abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.1, 2 As issued by World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001, the neurological disorders approximately account for 30.8% of all years of life lived with disability, while epilepsy, accounts for about 0.5% of the total burden of diseases,3 with the global prevalence ranged from 1.5 to 14 every 1000 people.4 Epilepsy occurs in all age groups, but is most common in children, and approximately one‐fourth patients are children, especially in children aged 5‐9 years.5 In recent decades, children with status epilepticus (SE) increased dramatically, posing a serious threat to children’s health and difficulties in clinical treatment, thus, the ideal reasonable treatment is of significance to reduce brain damage caused by SE.6

At present, a large number of studies found that the abnormal expressions of miRNAs were close correlated with nervous system damage and degenerative disease, including epilepsy.7, 8 As Surges et al9 reported, there were over 200 miRNAs presented different expression in the serum of patients after a seizure within 30 minutes. For instance, miR‐219 could inhibit seizure formation via modulating the CaMKII/NMDA receptor pathway.10 As a member of miR‐181 family, miR‐181b, was thought to be related with many nervous system diseases, for example, the increase in miR‐181b levels in the penumbras was strengthened via electroacupuncture, and neurobehavioral function rehabilitation was improved via miR‐181b by targeting PirB, as indicated by Deng et al.11 Moreover, Alacam et al12 speculated that miR‐181b‐5p acts as a potential index indicating resistance against schizophrenia treatment. However, rare studies pay attentions to the role of miR‐181b in the formation and development of epilepsy.

In addition, inflammatory mediators, like interleukin (IL) ‐1b, Toll‐like receptors (TLRs), or some other factors, have been identified to be linked to epilepsy progression, not only in experimental animal models, but also in patients.13, 14 TLR4, as an important member of TLRs, was reported to exert important functions in epileptogenesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in astrocytes,15 and administration of lipopolysaccharide, a component of the bacterial cell wall and a powerful TLR4 ligand, leading to acute and long‐term decreases in seizure threshold.16 Of note, in Kupffer cells and liver injury in mice, miR‐181b can mediate TLR4 signaling in response to ethanol,17 and miR‐181b can target TLR4 to regulate the proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes in human pasoriasis.18 Moreover, TLR4 was responsible for the activation of p38 and JNK,19 and there was evidence that selective targeting of JNK over p38 has become a potential therapeutic approach to neurological disorders, as well as epilepsy. However, whether miR‐181b could mediate P38/JNK signaling pathway via regulating TLR4 to affect further the occurrence and development of epilepsy is still unknown.

Therefore, we performed intracerebroventricular injection (i.c.v.) of kainic acid (KA) to construct epileptic juvenile rat models, and another i.c.v. injection of miR‐181b agomir or TAK‐242,a small‐molecule‐specific inhibitor of TLR4 signaling by selectively binding to specific amino acid Cys747 in the intracellular domain of TLR4,20 was injected into the hippocampus of KA rats to explore the function and relationship between miR‐181b, TLR4, and P38/JNK signaling pathway in rats.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

In order to testify the targeting relationship between miR‐181b and TLR4, we constructed luciferase reporter vector pMir‐Glo‐Wt‐TLR4 (TLR4‐WT) containing wild‐type TLR4 3′terminal sequence, as well as miR‐181b combined with mutant pMir‐Glo‐Mut‐TLR4 (TLR4‐Mut) plasmid, which were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co.,Ltd. Twenty‐four hours before transfection, PC12 cells (purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were seeded in 96‐well plate at a density of 4 × 104/well. One hour before transfection, Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM, SH30022.01B, HyClone) was added into each well. Following instructions of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Inc., California, USA), miR‐181b mimics and negative controls (NC) (Shanghai GenePharma Co.,Ltd) were co‐transfected with luciferase reporter vector into cells, respectively. After culture medium in plate was cleaned up, the configured transfection mixture was added into plate, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. The dual‐luciferase reporter assay system (E1910, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to detect luciferase activity. Every experiment was repeated in triple for the average value.

2.2. Animals

Four weeks old healthy Wistar rats of clean grade weighing 80 ± 10 g (half male and half female) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All rats were fed with free food and water, in normal circadian rhythm, at room temperature (22‐25°C) in a clean grade animal room. The animal experimental design has got permission from the Ethics Committee of Laboratory Animal, and all experimental behaviors to animals were strictly in accordance with animal protection and application regulations issued by International Association for the Study of Pain.21

2.3. Construction of the epilepsy model and grouping

A total of 60 rats were recruited in this study, of which 50 rats were subjected to i.c.v. injection of KA to the right lateral cerebral ventricle to construct rat epilepsy models. SE was induced through repetitive injections of KA with the initial dose of 24 mg/kg to 6 mg/kg every 30 minutes till SE presented. When the rats reached stages 4 on Racine’s scale22 and seizure lasted 30 minutes or longer, it was regarded as successful construction of epilepsy. In these 50 rats, a total of 47 rats were survived after KA injection, and 45 out of 47 epileptic models were successfully built, which were randomly divided into KA group, KA + miR‐181b group, KA + miR‐Scr group, KA + TAK‐242 group and KA + miR‐181b + LPS group with 9 rats in each group. One week later, another i.c.v. injection of miR‐181b agomir, negative control (NC) miRNA with a scrambled sequence (miR‐Scr), or TLR4 inhibitor (TAK‐242) at 10 nmol/kg was injected into the hippocampus of KA rats. In KA + miR‐181b + LPS group, i.c.v. of TLR‐4 activator LPS (0.5 mg/kg) was carried out immediately after injection of miR‐181b agomir. In addition, the rest 10 rats were injected with equal dose of normal saline (0.9% NaCl) as the Control group.

2.4. Morris water maze test

Six weeks later, Morris water maze test23 was carried out for 5 days (9: 00 to 11: 00 am) to detect the learning and memory abilities of rats. Before testing, let the rats adjust to the new environment for at least 30 minutes. In the beginning of each subsequent trial, rats were gently placed into the water from different platform location, facing the edge of the pool, to collect the escape latency for each rat. If rats failed to find the platform in 120 seconds, they were guided onto the platform by the experimenter. Finding the platform was defined as staying on it for at least 2 seconds. Training to find the platform was performed for 4 consecutive days, and after the last training, the number of times that rats crossed the removed hidden platform was recorded in 120 seconds after 24 hours.

2.5. Electroencephalo‐graph (EEG) recordings

After Morris water maze test, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction and 2% maintenance). Then, 2 small stainless steel screw electrodes (1.2‐mm diameter) were implanted over the temporal cortex of rats from bilateral sides (AP, −2.2 mm; L, −4.8 mm relative to bregma). Also, we implanted the 3rd stainless steel electrode over the right frontal cortex, which was regarded as a reference electrode. Then, Nicolet 1.0 software was used to analyze and quantify EEG data. Poly spike discharges lasting > 5s in high amplitude (> 29 baseline) and high‐frequency (>5 Hz) were considered as seizures.

2.6. Specimen collection

After EEG recording, 5 rats randomly selected from each group were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (3.5 mL/kg). The rat’s chest was open and inserted a round needle from the apex cordis. After the heart was cut from the right atrial appendage for bleeding, the normal saline (20 mL) plus 4% paraformaldehyde (40 mL) was poured through heart. Next, the brain was taken to immerse in 4% paraformaldehyde, and paraffin sections of coronal plane were used for HE staining, Nissl staining, TUNEL staining, and electron microscopy analysis. Rest of the rats in each group were immediately sacrificed postanesthesia to remove bilateral hippocampus rapidly and store at −80°C for qRT‐PCR and western blot.

2.7. HE staining

The brain sections (5 μm) were mounted on glass slides treated with poly‐L‐Lysine and stored at 4°C, which were stained with hematoxylin for 5 minutes after routine de‐waxing and washing, and the color was separated with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 20 seconds. Then, the sections were back to blue with 1% ammonia for 30 seconds, dyed with eosin for 5 minutes, dehydrated in increasing concentrations of alcohol, hyalinized with dimethylbenzene, followed by sealing with neutral gum for observation under microscope.

2.8. Nissl staining

Paraffin sections were baked at 65° C for 60 minutes, dewaxed, and washed by water. Then, the sections were stained by Nissl staining solution for 10 minutes, washed by distilled water twice for 30 seconds per time, and dehydrated by gradient alcohol in 70%, 85%, 95%, and 100%, respectively. After dehydration, sections were transparentized by xylene for 3 minutes, added with a drop of neutral resin and sealed with cover glass. Under microscope, sections were observed and taken photos.

2.9. TUNEL staining

Hippocampal tissue was prepared into frozen sections and immersed in 3% H2O2 phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate endogenous peroxidase reactions. After 0.01‐mL PBS (pH 7.4) washing 5 minutes × 3 times, 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 3% FBS protein were added for 15 minutes. With addition of 50 μL TUNEL reaction solution connected with luciferin, sections were placed at humidified box at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by PBS washing for 5 minutes ×3 times. Next, sections were reacted with stop solution for 10 minutes at room temperature and antidigoxin peroxidase antibody for 30 minutes at 37°C. Before medium change, sections were washed with PBS for 5 minutes ×3 times. Finally, sections were developed by DAB (3,3′ ‐diaminobenzidine), counterstained by HE, transparentized in xylene and sealed with neutral resin. Next, sections were placed under fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51 Upright fluorescence microscope, USA) and taken photos to observe positive TUNEL staining. The experiment was repeated in triple.

2.10. qRT‐PCR

The total RNA of hippocampal tissue was extracted from TRIzol (15 596 026, Invitrogen Inc., California, USA), and its concentration and purity were detected using NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Fisher Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Then the total RNA was stored at −80°C. According to gene sequences issued by Genbank database, PCR primers were designed by Primer 5.0 software and synthesized by Shanghai Gene Pharma Co., Ltd. PCR reaction was performed using ABI PRISM 7500 real‐time PCR System (ABI, USA) and SYBR Green I fluorescent kit (DRR041A, Takara Biotechnology Ltd., Dalian, China), with U6/GAPDH as internal reference. On the basis of 2−△△Ct, we calculated the relative expression quantity of target gene.24 The experiment was repeated for 3 times to obtain the mean value.

2.11. Western blot

Hippocampal tissue protein was extracted to detect the protein concentration using BCA (Bicinchoninic acid) Protein Assay Kit (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China). The extracted protein was added with loading buffer, boiled at 95°C for 10 minutes and loaded into each well at 50ug/well for conducting 10% polyacrylamide gel (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) electrophoresis in order to extract protein at 80 v to 120 v. We conducted wet transference at 100 mv for 70 minutes to polyvinylidenefluoride (PVDF) membrane. Then, PVDF membrane was sealed in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at room temperature for 1 hour and added with primary antibody TLR4(ab13556, 1/500), p38 (phospho T180 + Y182)(ab4822, 1/1000),JNK1 + JNK2 (phospho T183 + Y185)(ab4821, 1/1000), LC3 (ab51520,1/3000), Beclin‐1(ab62557, 1 μg/mL), p62(ab56416, 1/2000), ATG5 (ab108327, 1/10 000), ATG7(ab52472, 1/100 000), ATG12 (ab15589, 1/1000), Bcl‐2 (ab32124, 1/1000), Bax (ab32503, 1:2000), antiactive Caspase‐3 (ab49822, 1/1000), β‐actin (ab8226, 1 μg/mL) for overnight incubation at 4°C. All primary antibodies were purchased from Abcam Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA). With Tris‐buffered saline tween (TBST) washing for 5 minutes ×3 times, PVDF membrane was incubated in secondary antibody (1: 1000, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, UK) at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing for 5 minutes ×3 times, the immunoreactive proteins were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo) and analyzed by Bio‐rad Gel Dol EZ imager (GEL DOC EZ IMAGER, Bio‐rad, California, USA).Taking β‐actin as loading control, Image J software was applied to analyze gray value of target band. We conducted every experiment 3 times for mean value.

2.12. Electron microscopy analysis

The hippocampus of rats in each group were kept in 4% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 24 hours and fixed in 1% osmium acid, followed by dehydration in acetone, embedding in Epon resin (EMS, Fort Washington, PA, USA), and staining with lead citrate. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to explore the ultrastructural morphology in the brain section.

2.13. Statistical analysis

The SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was applied to analyze data. Expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), the comparison of measurement data among groups was analyzed using one‐way ANOVA, and comparison between 2 groups was analyzed by t‐test. P value of <0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

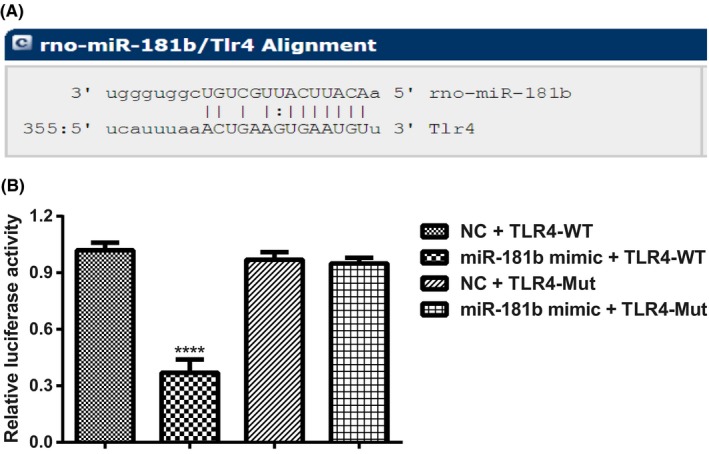

3.1. MiR‐181b directly targets TLR4

Bioinformatics analysis using microRNA.org (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) identified that TLR4 is the downstream target gene of miR‐181b (Figure 1A). The Dual‐luciferase reporter assay showed that in TLR4‐Mut group, the luciferase activity in both NC group and miR‐181b group was out of significance (P > 0.05). However, in TLR4‐WT group, the luciferase activity of miR‐181b was significantly decreased when compared with NC group (P < 0.05, Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

TLR4 was identified as a direct target of miR‐181b. Notes: A, Site for miR‐181b binding to TLR4 predicted by microRNA.org (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do); B, miR‐181b regulates TLR4 expression shown in Dual‐luciferase reporter assay in PC12 cells. ****P < 0.001, compared with other groups

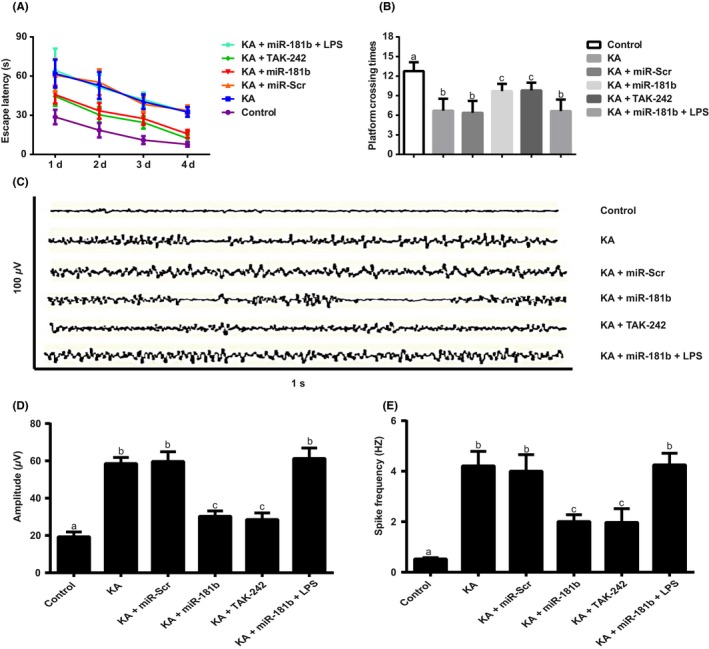

3.2. Behavior, spatial memory, and EEG recording observation

KA‐induced rats presented epileptic seizure, and the severity was enhanced with the increase in the number of injections, and the rats were gradually observed facial clonus, head nodding, forelimbs twitching and cramp, generalized muscle clonus, generalized tonic‐clonic seizure, tumbling, and falling. During 4 days of training, the escape latency for rats was longer in each KA group than Control group, while rats in KA + miR‐181b group and KA + TAK‐242 group were shorter than KA group (both P < 0.05, Figure 2A). In addition, the platform crossing times in KA group was far more than control group, but with injection of miR‐181b and TAK‐242, it was much less than KA group (both P < 0.05, Figure 2B). EGG analysis (Figure 2C‐E) showed that rats in Control group had normal behaviors with no epileptic seizure (normal basis wave and Racine stage 0). Among KA rats, KA + miR‐Scr group, and KA + miR‐181b + LPS group, the epileptic seizure in rats was classified as stage IV‐V, and EEG appeared a single pike wave, sharp wave, and spike and spike‐and‐slow‐wave complexes, which gradually evolved into a pattern of high‐frequency amplitude. However, the epileptic seizure of rats was obviously reduced to stage I‐II, and EEG showed less epileptic wave frequency, decreased amplitude, and a small amount of low‐amplitude sharp wave and spike wave after being injected with miR‐181b and TAK‐242.

Figure 2.

Behavior, spatial memory, and EEG recording observation of rats in each group. Notes: A, The escape latency for rats in each group; B, the platform crossing times for rats in each group; C‐E rats were analyzed by EEG recording and representative images are shown. Quantitative comparison for amplitude (D) and spike frequency (E) of seizure EEG studies

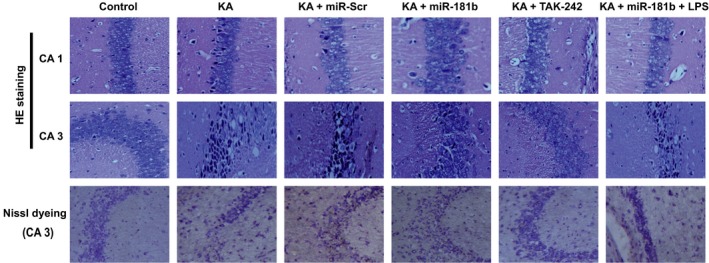

3.3. Observation of HE staining and Nissl staining

HE staining (Figure 3) demonstrated that juvenile rats in Control group had normal hippocampal tissues, and pyramidal cells were regularly arranged with uniformly stained. While, in KA group, KA + miR‐Scr group, and KA + miR‐181b + LPS group, cells were arranged in disorder in areas CA1 and CA3 of the rat hippocampus with deeply stained violet, and some other abnormalities also presented, including cytoplasm vacuoles, neuronal swelling, shrinkage, cell volume reduction, especially in CA3 region. In KA + miR‐181b group and KA + TAK‐242 group, rats showed alleviated cell damage, mild degeneration and cellular swelling, loosened cellular arrangement, and mild proliferation of glial cells. Nissl staining (Figure 3) results of CA3 region in hippocampal tissue demonstrated that in Control group, the granule cells of hippocampus in rats were arranged tidily. The cells of KA group were large and sparsely arranged. Compared with KA group, the granule cells in KA + miR‐181 band KA + TAK‐242 groups were significantly reduced with spotty necrosis.

Figure 3.

Observation of HE staining and Nissl staining for the hippocampus morphological changes in each group (×400)

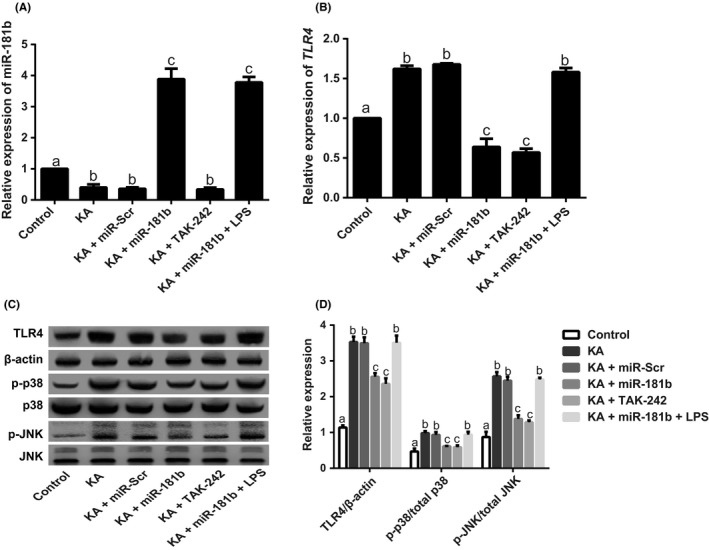

3.4. Expressions of miR‐181b and TLR4/P38/JNK pathway proteins in the hippocampus of rats

As shown in Figure 4, in contrast to Control group, both KA group and KA + miR‐Scr group revealed a significant decrease in miR‐181b expression and obvious elevations of TLR4 and P38/JNK pathway‐related proteins (including p‐P38 and p‐JNK) (all P < 0.05). Moreover, miR‐181b expression was significantly upregulated in rats in the KA + miR‐181b and KA + miR‐181b + LPS groups as compared with KA group. Additionally, both miR‐181b and TAK‐242 can not only significantly down‐regulate TLR4 expression in hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic rats, but also inhibit P38/JNK signaling pathway (all P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in expressions of TLR4, p‐P38, and p‐JNK among KA, KA + miR‐Scr, and KA + miR‐181b + LPS groups (all P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Expressions of miR‐181b and TLR4/P38/JNK signaling pathway‐related proteins in the hippocampus of KA‐induced juvenile epileptic rats. Notes: A‐B, Expressions of miR‐181b (A) and TLR4 mRNA (B) in the hippocampus of KA‐induced juvenile epileptic rats detected by qRT‐PCR; C‐D, Expressions of TLR4 and P38/JNK signaling pathway‐related proteins detected by western blot

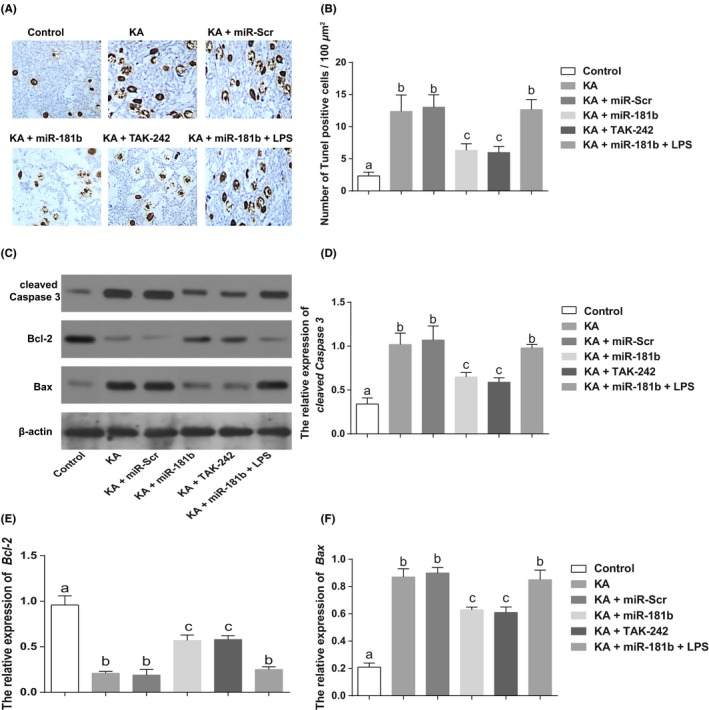

3.5. MiR‐181b mediates P38/JNK signaling pathway to inhibit the apoptosis of hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats via targeting TLR4

The criterion for positive staining of TUNEL was that the nuclei were stained pale brown. In Control group, only very few positive cells were observed in CA3 region of hippocampus. Compared with Control group, TUNEL‐positive cells in hippocampus significantly increased, as well as the number of apoptotic cells in KA group and KA + miR‐Scr group, and meanwhile, the proapoptotic protein (Bax and cleaved caspases‐3) greatly increased, but antiapoptotic‐protein Bcl‐2 was evidently decreased (all P < 0.05). Moreover, miR‐181b and TAK‐242 can significantly lower the number of apoptotic cells in KA‐induced hippocampus, down‐regulate Bax and cleaved caspases‐3 expressions, but upregulate Bcl‐2 expression (all P < 0.05, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

MiR‐181b mediates P38/JNK signaling pathway to inhibit the apoptosis of hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats via targeting TLR4. Notes: A‐B, Cell apoptosis in the hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats detected by TUNEL staining; C‐F, Apoptosis‐related protein expressions [including Caspase‐3 (D), Bcl‐2 (E) and Bax (F)] detected by western blot

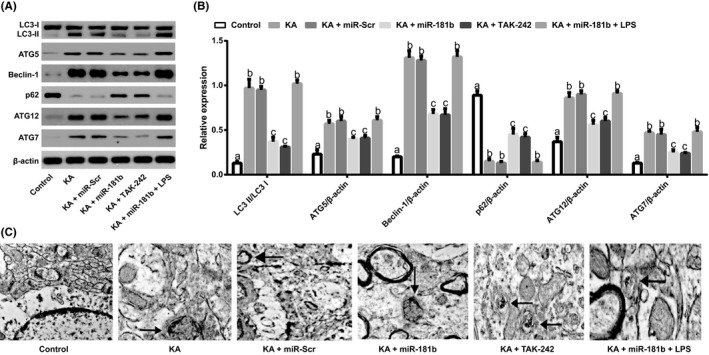

3.6. MiR‐181b mediates P38/JNK signaling pathway to inhibit the autophagy of hippocampus in KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats via targeting TLR4

Western blot was conducted to detect expressions of autophagy‐related proteins (including LC3II/I, Beclin‐1, p62, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12), and the results showed that KA could significantly increase expressions of LC3II/I, Beclin‐1, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12, but decreased p62 expression (all P < 0.05). When compared with KA group, expressions of LC3II/I, Beclin‐1, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12 were substantially decreased in KA + miR‐181b group and KA + TAK‐242 group, but p62 expression were increased (all P < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found in expressions of autophagy‐related proteins among KA group, KA + miR‐Scr group, and KA + miR‐181b + LPS group (Figure 6A‐B). Moreover, integral nuclear membranes, uniform distribution of chromatin, a variety of normal organelles, and no autophagy was observed in the Control group by using electron microscopy. The rats in KA and KA + miR‐Scr groups showed autophagic lysosome with nuclear chromatin pyknosis. The rats from KA + miR‐181b group and KA + TAK‐242 group showed double‐membrane structures with a few spherical lysosomes (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

MiR‐181b mediates P38/JNK signaling pathway to inhibit the autophagy of hippocampus in KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats via targeting TLR4. Note:A‐B, Expressions of autophagy‐related proteins (including LC3 II/I, ATG5, Beclin‐1, p62, ATG7, and ATG12) in the hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats detected by western blot; C, Electron microscopy analysis using transmission electron microscopy (TEM); the arrow refers to the autophagosomes and double‐membrane structures

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, one of the most important results showed that the expression of miR‐181b was down‐regulated but TLR4 was upregulated in hippocampus of KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats. For the past few years, several studies revealed a close relationship between the abnormal expression of miR‐181 family and epilepsy. For example, miR‐181a, another miR‐181 family members, was observed to be overexpressed in epileptic rats and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, which might damage cognitive function via the reduction ofBcl‐2 expression and the promotion of apoptosis in the hippocampus.25, 26 On the contrary, the significantly lowered expression of miR‐181c‐5p was found in epileptic patients in contrast to normal control group,27 and this miRNA could exert neuronal protection via inhibiting tumor necrosis factor,28 suggesting that the members of miR‐181 family may play a pathogenic or inhibitory role in epilepsy through affecting the downstream genes. In the study by Zhang et al,29 miR‐181b, as an antiapoptotic gene, had the similar expression pattern as our findings in the hippocampus of postSE rats through regulating Nrarp and Notch signaling pathway. On the other hand, the enhanced proinflammatory cytokines levels in patients with chronic epilepsy provided evidence for the neuro inflammation involvement in epileptogenesis,30, 31 which were generated via the activation of TLRs by exogenous and endogenous ligands.3 As the first found member of TLRs, TLR4 was expressed in a variety of normal brain cells, which was closely related to the occurrence and development of epilepsy.32, 33 For instance, TLR4 signaling pathway was evidently activated in the hippocampus of KA‐induced immature rats, as reported by Chen Yet al,34 and meanwhile, Maroso et al35 pointed out that the antagonists of TLR4 could not only block epilepsy seizure, but also reduce acute and chronic seizure recurrence. Notably, Dual‐luciferase reporter assay in this study further highlighted the targeting relationship between miR‐181b and TLR4, which was in accordance with study by Feng et al,18 implying that miR‐181b may play an important role in the process of epilepsy by modulating TLR4.

To further explore the interaction between miR‐181b and TLR4, as well as its underlying mechanism in epilepsy, we gave an injection of miR‐181b agomir or TAK‐242 (TLR4 inhibitor) to KA‐induced epileptic juvenile rats, and our findings demonstrated that the spatial memory abilities of rats, as a kind of advanced neural activity of brain, which was an important element of both cognition and intelligence structure, whereas many epileptic patients have severe cognitive impairment, were significantly improved.36, 37 Besides, miR‐181b and TAK‐242 in this work could significantly inhibit the cell apoptosis in hippocampus tissue of KA‐induced epileptic rats, with down‐regulation of Bax and cleaved caspases‐3 expressions but upregulation of Bcl‐2. As we know, SE seizure may result in morphological changes of hippocampal neurons, such as cellular swelling, rupture, karyopyknosis or karyolysis, apoptosis, and autophagic corpuscle formation.38 While apoptosis, as a critical programmed cell death, exerts vital effects on hippocampal neuron injury postseizure,39 and inhibition of apoptosis has important neuro‐protective effects on hippocampal neuronal injury postseizure.40, 41 Currently, growing evidence supported that neuronal apoptosis can lead to upregulation of proapoptotic protein Bax and downregulation of antiapoptotic proteinBcl‐2 after SE seizure. In addition, Bax also moves from cytoplasm to mitochondria, and induces cytochrome c released from mitochondria induced proteolytic cleavage of procaspase‐3, thereby completing the process of apoptosis.42, 43 Thus, we reasonably hypothesized that miR‐181b can inhibit cell apoptosis via targeting TLR4 in epileptic seizure. Moreover, we also discovered that miR‐181b and TAK‐242 can dramatically suppress autophagic‐related proteins (LC3II/I, Beclin‐1, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12) in hippocampus, and also induce autophagy of hippocampal neurons after seizure.38 To our knowledge, autophagy was strictly regulated and controlled by autophagy‐related molecules(collectively termed Atgs),38 and the amount of LC3‐II or the ratio of LC3‐II/LC3‐I can reflect the autophagic activity.44 As such, miR‐181b may inhibit the autophagy of hippocampus in rats via negative regulation of TLR4.

Furthermore, this study also exhibited that expressions of p‐P38 and p‐JNK were significantly increased in KA‐induced epileptic rats, but were evidently inhibited with injection of miR‐181b and TAK‐242. It was noteworthy that JNK/P38 signaling pathway was a vital part of mitogen‐activated protein kinase family, mitogen‐activated protein kinase which was important in apoptosis and autophagy by transmitting extracellular stimuli to the nucleus.45, 46 There was evidence that TLR4 can regulate P38/JNK signaling pathway to influence disease progression, in the study by Chen et al,47 reported that the TLR4‐p38 and JNK MAPK signaling pathway helps to stimulate the inflammatory cytokine production secreted by injured normal human epidermal keratinocytes. More importantly, P38/JNK signaling pathway was reported to be correlated with epilepsy, which was activated in rat hippocampus postkainic acid‐induced seizure.48 Besides, in refractory epileptic rats, suppressing p38 signaling weakened multidrug transporter activity and antiepileptic drug resistance.49 Last but not least, there were no significant alterations after rats accepted injection of miR‐181b agomir and LPS (TLR4 activator).

Therefore, our study provided evidence that miR‐181b may mediate P38/JNK signaling to inhibit hippocampal apoptosis and autophagy via negatively regulating TLR4, thereby acting as a neuroprotective role in KA‐induced epileptic rats.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the science and technology plan projects of development and support of Zhengzhou city (No: 20150159). We would like to give our sincere appreciation to the reviewers for their helpful comments on this article.

Wang L, Song L‐F, Chen X‐Y, et al. MiR‐181b inhibits P38/JNK signaling pathway to attenuate autophagy and apoptosis in juvenile rats with kainic acid‐induced epilepsy via targeting TLR4. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:112–122. 10.1111/cns.12991

REFERENCES

- 1. Espinola‐Nadurille M, Crail‐Melendez D, Sanchez‐Guzman MA. Stigma experience of people with epilepsy in Mexico and views of health care providers. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;32:162‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Remember..there is more to epilepsy than seizures!. Neurology. 2015;85:1094‐1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matin N, Tabatabaie O, Falsaperla R, et al. Epilepsy and innate immune system: a possible immunogenic predisposition and related therapeutic implications. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2021‐2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mac TL, Tran DS, Quet F, Odermatt P, Preux PM, Tan CT. Epidemiology, aetiology, and clinical management of epilepsy in Asia: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:533‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paticheep S, Chotipanich C, Khusiwilai K, Wichaporn A, Khongsaengdao S. Antiepileptic drugs and bone health in thai children with epilepsy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98:535‐541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu PM, Ding D, Zhu GX, Hong Z. International Bureau for Epilepsy survey of children, teenagers, and young people with epilepsy: data in China. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;16:99‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vinciguerra A, Formisano L, Cerullo P, et al. MicroRNA‐103‐1 selectively downregulates brain NCX1 and its inhibition by anti‐miRNA ameliorates stroke damage and neurological deficits. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1829‐1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srivastava A, Dixit AB, Banerjee J, Tripathi M, Sarat Chandra P. Role of inflammation and its miRNA based regulation in epilepsy: implications for therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;452:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Surges R, Kretschmann A, Abnaof K, et al. Changes in serum miRNAs following generalized convulsive seizures in human mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;481:13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng H, Tang R, Yao Y, et al. MiR‐219 Protects Against Seizure in the Kainic Acid Model of Epilepsy. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng B, Bai F, Zhou H, et al. Electroacupuncture enhances rehabilitation through miR‐181b targeting PirB after ischemic stroke. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alacam H, Akgun S, Akca H, Ozturk O, Kabukcu BB, Herken H. miR‐181b‐5p, miR‐195‐5p and miR‐301a‐3p are related with treatment resistance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:200‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cui L, Tao H, Wang Y, et al. A functional polymorphism of the microRNA‐146a gene is associated with susceptibility to drug‐resistant epilepsy and seizures frequency. Seizure. 2015;27:60‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lorigados Pedre L, Morales Chacon LM, Orozco Suarez S, et al. Inflammatory mediators in epilepsy. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:6766‐6772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gan N, Yang L, Omran A, et al. Myoloid‐related protein 8, an endogenous ligand of Toll‐like receptor 4, is involved in epileptogenesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy via activation of the nuclear factor‐kappaB pathway in astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:337‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riazi K, Galic MA, Pittman QJ. Contributions of peripheral inflammation to seizure susceptibility: cytokines and brain excitability. Epilepsy Res. 2010;89:34‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saikia P, Bellos D, McMullen MR, Pollard KA, de la Motte C, Nagy LE. MicroRNA 181b‐3p and its target importin alpha5 regulate toll‐like receptor 4 signaling in Kupffer cells and liver injury in mice in response to ethanol. Hepatology. 2017;66:602‐615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feng C, Bai M, Yu NZ, Wang XJ, Liu Z. MicroRNA‐181b negatively regulates the proliferation of human epidermal keratinocytes in psoriasis through targeting TLR4. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:278‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19. Chen Y, Liu T, Langford P, et al. Haemophilus parasuis induces activation of NF‐kappaB and MAP kinase signaling pathways mediated by toll‐like receptors. Mol Immunol. 2015;65:360‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Woller SA, Ravula SB, Tucci FC, et al. Systemic TAK‐242 prevents intrathecal LPS evoked hyperalgesia in male, but not female mice and prevents delayed allodynia following intraplantar formalin in both male and female mice: the role of TLR4 in the evolution of a persistent pain state. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:271‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orlans FB. Ethical decision making about animal experiments. Ethics Behav. 1997;7:163‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Racine R, Okujava V, Chipashvili S. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. 3. Mechanisms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:295‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bromley‐Brits K, Deng Y, Song W. Morris water maze test for learning and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. J Vis Exp. 2011;53:2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tuo YL, Li XM, Luo J. Long noncoding RNA UCA1 modulates breast cancer cell growth and apoptosis through decreasing tumor suppressive miR‐143. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3403‐3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y, Liu X, Liao Y, et al. MiR‐181a influences the cognitive function of epileptic rats induced by pentylenetetrazol. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:12861‐12868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ren L, Zhu R, Li X. Silencing miR‐181a produces neuroprotection against hippocampus neuron cell apoptosis post‐status epilepticus in a rat model and in children with temporal lobe epilepsy. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang J, Yu JT, Tan L, et al. Genome‐wide circulating microRNA expression profiling indicates biomarkers for epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang L, Dong LY, Li YJ, Hong Z, Wei WS. The microRNA miR‐181c controls microglia‐mediated neuronal apoptosis by suppressing tumor necrosis factor. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang C, Hou D, Feng X. Mir‐181b functions as anti‐apoptotic gene in post‐status epilepticus via modulation of nrarp and notch signaling pathway. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2015;45:550‐555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Babcock AA, Wirenfeldt M, Holm T, et al. Toll‐like receptor 2 signaling in response to brain injury: an innate bridge to neuroinflammation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12826‐12837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double‐stranded RNA and activation of NF‐kappaB by Toll‐like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sedaghat R, Taab Y, Kiasalari Z, Afshin‐Majd S, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M. Berberine ameliorates intrahippocampal kainate‐induced status epilepticus and consequent epileptogenic process in the rat: underlying mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;87:200‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rupasree Y, Naushad SM, Rajasekhar L, Uma A, Kutala VK. Association of TLR4 (D299G, T399I), TLR9 ‐1486T>C, TIRAP S180L and TNF‐alpha promoter (‐1031, ‐863, ‐857) polymorphisms with risk for systemic lupus erythematosus among South Indians. Lupus. 2015;24:50‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y, Huang XJ, Yu N, et al. HMGB1 Contributes to the Expression of P‐Glycoprotein in Mouse Epileptic Brain through Toll‐Like Receptor 4 and Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0140918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maroso M, Balosso S, Ravizza T, et al. Toll‐like receptor 4 and high‐mobility group box‐1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat Med. 2010;16:413‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang H, Xie Y, Weng L, et al. Rapamycin improves learning and memory ability in ICR mice with pilocarpine‐induced temporal lobe epilepsy. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2013;42:602‐608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Talero‐Gutierrez C, Sanchez‐Torres JM, Velez‐van‐Meerbeke A. Learning skills and academic performance in children and adolescents with absence epilepsy. Neurologia. 2015;30:71‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang J, Liu Y, Li XH, et al. Curcumin protects neuronal cells against status‐epilepticus‐induced hippocampal damage through induction of autophagy and inhibition of necroptosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;95:501‐509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang Q, Liu X, Wu Y, et al. P38 MAPK pathway mediates cognitive damage in pentylenetetrazole‐induced epilepsy via apoptosis cascade. Epilepsy Res. 2017;133:89‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhao Y, Han Y, Bu DF, et al. Reduced AKT phosphorylation contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress‐mediated hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in rat recurrent febrile seizure. Life Sci. 2016;153:153‐162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luo Z, Fang Y, Zhang L. The effects of antiepileptic drug valproic acid on apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in epileptic rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28(1 Suppl):319‐324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mikati MA, Zeinieh M, Habib RA, et al. Changes in sphingomyelinases, ceramide, Bax, Bcl(2), and caspase‐3 during and after experimental status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2008;81:161‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Henshall DC, Clark RS, Adelson PD, Chen M, Watkins SC, Simon RP. Alterations in bcl‐2 and caspase gene family protein expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2000;55:250‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:77‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li C, Wang T, Zhang C, Xuan J, Su C, Wang Y. Quercetin attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via inhibition of JNK and p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Gene. 2016;577:275‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sui X, Kong N, Ye L, et al. p38 and JNK MAPK pathways control the balance of apoptosis and autophagy in response to chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Lett. 2014;344:174‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen L, Guo S, Ranzer MJ, DiPietro LA. Toll‐like receptor 4 has an essential role in early skin wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:258‐267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jeon SH, Kim YS, Bae CD, Park JB. Activation of JNK and p38 in rat hippocampus after kainic acid induced seizure. Exp Mol Med. 2000;32:227‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shao Y, Wang C, Hong Z, Chen Y. Inhibition of p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling reduces multidrug transporter activity and anti‐epileptic drug resistance in refractory epileptic rats. J Neurochem. 2016;136:1096‐1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]