Abstract

Neuron-derived exosomes (NDEs) were enriched by anti-L1CAM antibody immunoabsorption from plasmas of subjects ages 18–26 yr within 1 wk after a sports-related mild traumatic brain injury (acute mTBI) (n = 18), 3 mo or longer after the last of 2–4 mTBIs (chronic mTBI) (n = 14) and with no recent history of TBI (controls) (n = 21). Plasma concentrations of NDEs, assessed by counts and levels of extracted exosome marker CD81, were significantly depressed by a mean of 45% in acute mTBI (P < 0.0001), but not chronic mTBI, compared with controls. Mean CD81-normalized NDE levels of a range of functional brain proteins were significantly abnormal relative to those of controls in acute but not chronic mTBI, including ras-related small GTPase 10, 73% decrease; annexin VII, 8.8-fold increase; ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1, 2.5-fold increase; AII spectrin fragments, 1.9-fold increase; claudin-5, 2.7-fold increase; sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter-1, 2.8-fold increase; aquaporin 4, 8.9-fold increase (3.6-fold increase in chronic mTBI); and synaptogyrin-3, 3.1-fold increase (1.3-fold increase in chronic mTBI) (all acute mTBI proteins P < 0.0001). In chronic mTBI, there were elevated CD81-normalized NDE levels of usually pathologic β-amyloid peptide 1-42 (1.6-fold, P < 0.0001), P-T181-tau (2.2-fold, P < 0.0001), P-S396-tau (1.6-fold, P < 0.01), IL-6 (16-fold, P < 0.0001), and prion cellular protein (PRPc) (5.1-fold, P < 0.0001) with lesser or greater (IL-6, PRPc) increases in acute mTBI. Increases in NDE levels of most neurofunctional proteins in acute, but not chronic, mTBI, and elevations of most NDE neuropathological proteins in chronic and acute mTBI delineated phase-specificity. Longitudinal studies of more mTBI subjects may identify biomarkers predictive of and etiologically involved in mTBI-induced neurodegeneration.—Goetzl, E. J., Elahi, F. M., Mustapic, M., Kapogiannis, D., Pryhoda, M., Gilmore, A., Gorgens, K. A., Davidson, B., Granholm, A.-C., Ledreux, A. Altered levels of plasma neuron-derived exosomes and their cargo proteins characterize acute and chronic mild traumatic brain injury.

Keywords: biomarkers, exosome immunoabsorption, proteinopathic neurodegeneration

Mechanical injury to the parenchymal tissues and meninges of the brain and the subsequent series of further damaging proteolytic, oxidative, inflammatory, and proteinopathic responses are collectively termed traumatic brain injury (TBI) (1–3). Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) from participation in high-impact sports is a leading cause of disability in young adults (4, 5). Our understanding of the injurious components and restorative mechanisms of both acute mTBI resulting from a single concussive blow and the mechanisms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) following repeated episodes of acute mTBI is incomplete and based largely on results of studies of isolated cellular and rodent models.

Disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is one of the earliest consequences of acute mTBI that is manifested maximally within a few hours by morphologic changes in endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes, increases in the number of perivascular monocytes, and elevated blood levels of tight-junction proteins and astrocyte-specific proteins (6–9). Resultant edema of neural cells and interstitial tissues follows with a peak at 24–48 h in association with increased brain tissue levels of protein components of diverse neuronal channels and vesicle transport systems (9, 10). Axonal injury then is observed, which is characterized by signs of mitochondrial damage, release of cytochrome C, and activation of caspases and other proteases (11).

Inflammation develops in the same time period of initial responses to acute mTBI, as shown by increased neural tissue levels of cytokines, such as IL-6, IFN-α, IL-1β, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, oxygen radicals, and matrix metalloproteinases (12–18). This period also is characterized by increased expression of stress response and proapoptotic factor genes (19). Acute mTBI thus evokes a complex response of neural abnormalities that includes changes in neural fluid and vesicle movements, multifactorial inflammation, and initiation of regional apoptosis.

Insidious onset of the persistent features of CTE may appear after a single episode of severe acute TBI or be imposed on a repetitive series of episodes of acute mTBI. These include some of the elements of proteinopathic neurodegeneration typical of Alzheimer disease (AD) and other senile dementias, although an increased incidence of late-onset AD has been established only following single-incident severe TBI (20). Although the bridges linking acute mTBI to CTE are poorly understood, a few mechanisms have been recognized. Within 24 h of acute TBI in rats, hippocampal and cortical brain tissues showed increases in β-secretase-1 or β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 mRNA and protein, but these returned to normal levels within 7 d (21). In humans suffering single-incident severe TBI, increases in brain tissue levels of amyloid precursor protein and Aβ-peptides as well as diffuse Aβ-collections are found within hours (20). In contrast, the predominant early neuropathology in repetitive mTBI is patchy distribution of neurofibrillary tangles of tau and neuropil threads of tau throughout the neocortex (20). Plasma levels of tau-positive exosomes were abnormally elevated in former professional football players, and these increases correlated with decreases in memory and psychomotor speed (22). Although many abnormalities of cognition and affect or mood are similar in subjects suffering from CTE after acute severe TBI or repetitive mild TBI, relationships between these neurocognitive abnormalities and differing proteinopathic etiologic mechanisms have not been delineated (23–25).

Investigations of a wide range of neurally derived proteins in CSF and plasma have not yielded biomarkers that reliably assess the severity of TBI, predict progression of TBI to CTE, or offer useful targets for therapy (20, 26–28). It thus seems appropriate now to investigate alterations in levels of diverse proteins of the BBB, neuronal plasma membrane structure and functions, neuronal vesicle formation and traffic, and synaptic activity that are accessible in plasma neuron-derived exosomes (NDEs) of subjects with acute or chronic mTBI. The present results demonstrate striking patterns of abnormalities in these NDE proteins that distinguish acute mTBI from chronic mTBI and suggest possible mechanisms by which abnormalities of acute mTBI may contribute to the initiation and progression of CTE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient recruitment and evaluation

Participants were college students from the University of Denver (DU) and 10 additional controls from University of California, San Francisco, of similar ages as the DU students (Table 1). Head injuries were sustained in the course of playing National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I high-impact sports, predominantly ice hockey or lacrosse. Acute mTBI was defined by the standard NCAA clinical criteria for diagnosis and included 18 participants who donated plasma for this study within 7 d of an episode of mTBI (29). Subjects with acute mTBI had suffered 0 (8/18) or 1 (6/18) or 2 (3/18) or 3 (1/18) mTBIs before the episode of this study, but all occurred at least 8 mo before the study occasion (8–72 mo). Chronic mTBI was defined as having had at least 2 past mTBIs (2 for 11/14 and 3 or more for 3/14), but none for at least 3 mo (range 3–12 mo) before donation of plasma for this study (Table 1). Only 2 of 21 controls reported one previous mTBI at least 5 yr before participation in this study. On entry into the study, all participants underwent rigorous NCAA standard testing, including a cognitive battery (30), motion capture analysis of static and dynamic balance (Human Dynamics Laboratory, DU, Denver, CO, USA), and the King-Devick eye movement test (31). The Concussion Research Consortium at DU (M.P., A.G., K.A.G., B.D., A.-C.G., and A.L.) supervised recruitment, consenting and clinical testing of participants, handling of all data, and blood collection. One investigator (E.J.G.) isolated NDEs from all plasmas together by the same procedures and completed ELISAs.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Group | n | Age (mean ± sem) | Gender (female/male) | Prior no. of acute TBIs (mean ± sem, range) | Months since last mTBI (mean ± sem) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 21 | 20.62 ± 0.39 | 14/7 | 0 | NA |

| mTBI | |||||

| Acute | 18 | 20.67 ± 0.33 | 12/6 | 0.83 ± 0.22, 0–2 | 23.50 ± 7.75 |

| Chronic | 14 | 19.64 ± 0.49 | 3/11 | 2.29 ± 0.16,** 2–4 | 7.64 ± 0.79+ |

Statistical significance of difference from acute mTBI group. +P = 0.014, **P < 0.0001.

The protocol and procedures of this study received prior approval by the Institutional Review Boards of the DU and University of California, San Francisco. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Enrichment of plasma NDEs for extraction and ELISA quantification of proteins

Aliquots of 0.25 ml plasma were incubated with 0.1 ml thromboplastin D (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by addition of 0.15 ml of calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s balanced salt solution with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as previously described (32). After centrifugation at 3000 g for 30 min at 4°C, NDEs were harvested from resultant supernatants by sequential ExoQuick (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) precipitation and immunoabsorption enrichment with mouse anti-human CD171 (L1CAM neural adhesion protein) biotinylated antibody (clone 5G3; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described (32). Exosomes were counted and their size ranges determined, as previously described (33), and lysed in mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER; Thermo Fisher Scientific) that contained protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails before storage at −80°C.

NDE proteins were quantified by ELISA kits for human aquaporin-4, occludin, claudin-5, AII spectrin breakdown products (also termed SPDP145) and tetraspanning exosome marker CD81 (Cusabio; American Research Products, Waltham, MA, USA), sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC-1) and prion cellular protein (PRPc) (Cloud-Clone, American Research Products), synaptogyrin-3 (Abbkine; China-American Research Products, Wuhan, China), IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), ras-related small GTPase 10 (RAB10) and annexin VII (Biomatik, Wilmington, DE, USA), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1; RayBiotech, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA), β-amyloid peptide 1-42 (Aβ42) (ultrasensitive ELISA), P-S396-tau, and total tau (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and P-T181-tau (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Malvern, PA, USA).

The mean value for all determinations of CD81 in each assay group was set at 1.00, and relative values of CD81 for each sample were used to normalize their recovery. One investigator (E.J.G.) conducted all ELISAs without knowledge of the clinical data for any subject.

Statistical analyses

The Shapiro-Wilks test showed that data in all sets were distributed normally. Statistical significance of differences between the mean value for each control group and mean values for the corresponding acute and chronic mTBI groups was determined with an unpaired Student’s t test, including a Bonferroni correction (Prism 6; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

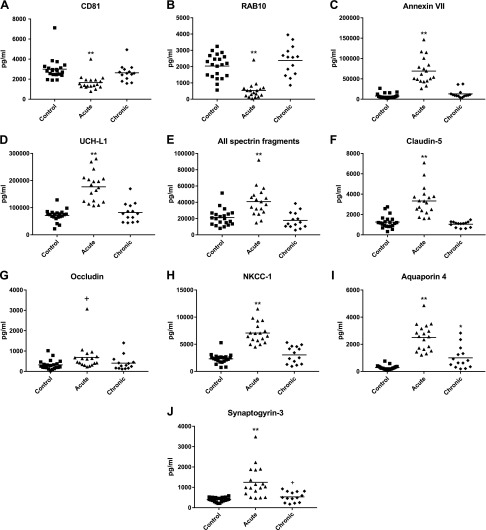

The concentration of NDEs was significantly lower in plasmas of subjects with acute mTBI, who donated blood within 7 d of suffering an episode of mTBI, than in plasmas of control subjects with no history of TBI or of those with chronic and more repetitive mTBIs, but none for 3 or more mo before blood collection (Fig. 1A). The differences in NDE levels shown by the exosome biomarker protein CD81 were confirmed by counts that were 213 ± 15.7 × 109/ml (mean ± sem) for controls, 141 ± 12.8 × 109/ml for acute mTBI subjects (P < 0.0001 compared with controls), and 212 ± 14.2 × 109/ml for chronic mTBI subjects. The ras-related small GTPase RAB10 is required for formation, intracellular movements, and secretion of NDEs and some other extracellular vesicles (34). Thus it appears likely that diminished CD81-normalized levels of RAB10 observed in NDEs of acute mTBI subjects relative to those in NDEs of chronic mTBI subjects and controls (Fig. 1B) are at least in part responsible for concomitant decreases in plasma concentrations of NDEs in acute mTBI subjects. The phospholipid-binding protein annexin-VII also may be involved in intracellular traffic of vesicles (35), but it has other predominant functions including maintenance of neuronal viability and membrane transport functions. The higher levels of annexin-VII in NDEs and presumably neurons of acute mTBI subjects relative to those of chronic mTBI subjects and controls (Fig. 1C) may reflect the greater precedence of these other critical activities. To focus on NDE cargo protein processing after TBI, we quantified NDE levels of UCH-L1 that is an abundant neuron-specific facilitator of elimination of damaged proteins through ubiquitinylation targeting for destructive removal by the ATP-dependent proteosomal pathway (36). Levels of UCH-L1 in CSF and serum have been shown to be elevated for several days after acute mTBI (37). Here it is demonstrated that CD81-normalized NDE levels of UCH-L1 are higher in NDEs and presumably neurons of acute mTBI subjects than in those of chronic mTBI subjects and controls (Fig. 1D). This finding supports up-regulation in acute mTBI of one ubiquitin-dependent pathway of elimination of damaged neuronal proteins.

Figure 1.

Levels of NDE neurofunctional cargo proteins in cross-sectional control, acute mTBI, and chronic mTBI groups. Each point represents the value for a control or mTBI participant, and the horizontal line in point clusters is the mean level for that group. Mean ± sem control, acute mTBI, and chronic mTBI participant values, respectively, are 2994 ± 237, 1654 ± 166, and 2634 ± 225 pg/ml for CD81 (A); 2012 ± 159, 539 ± 126, and 2380 ± 244 pg/ml for RAB10 (B); 7824 ± 1374, 69,133 ± 7691, and 13,167 ± 2828 pg/ml for annexin VII (C); 71,740 ± 4755, 176,892 ± 12,764, and 79,628 ± 9894 pg/ml for UCH-L1 (D); 21,194 ± 2214, 40,794 ± 4281, and 17,783 ± 2641 pg/ml for AII spectrin breakdown products (E); 1255 ± 135, 3328 ± 341, and 1087 ± 102 pg/ml for claudin-5 (F); 322 ± 51.3, 689 ± 151, and 405 ± 95.4 pg/ml for occludin (G); 2319 ± 204, 6428 ± 529, and 3040 ± 422 pg/ml for NKCC-1 (H); 281 ± 35.3, 2507 ± 230, and 1000 ± 217 pg/ml for aquaporin 4 (I); and 399 ± 23.2, 1250 ± 183, and 530 ± 67.5 pg/ml for synaptogyrin-3 (J). The significance of differences shown between values for controls and acute mTBI subjects and between controls and chronic mTBI subjects were calculated by an unpaired Student’s t test. +P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001.

We next quantified effects of the different patterns of timing of mTBI on NDE levels of representative proteins required for normal functions of the neuronal cytoskeleton, neuronal water channels and ion carriers, and the BBB. The membrane-associated periodic skeleton in axons of all eukaryotic neurons consists of actin rings separated by spectrin tetramer “spacers,” is necessary for functional organization of membranes, and is cleaved by diverse proteases after brain injury (38, 39). NDE levels of cleavage fragments of AII spectrin were significantly elevated after acute mTBI relative to those detected in controls and as a result of chronic mTBIs, suggesting rapid and transient breakdown of the human neuronal periodic skeleton by mTBI (Fig. 1E). Occludin and claudin-5 are the main protein components of the tight junction of the BBB, which increase in concentration in brain tissues and blood after blast injury of rodent brains (9). NDE levels of claudin-5 were significantly higher and of occludin were only marginally higher after acute mTBI than for either controls or subjects sustaining chronic mTBIs (Fig. 1F, G). In neurons, NKCC-1 is a principal cotransporter of ions and aquaporin 4 is the major water channel (40, 41). CD81-normalized NDE levels of NKCC-1 and aquaporin 4 both were significantly elevated after acute mTBI relative to levels in controls and subjects with chronic mTBIs (Fig. 1H, I), implying a possible role in the acute development of brain edema following mTBI. NDE levels of aquaporin 4, but not NKCC-1, also were significantly elevated as a result of chronic mTBIs relative to levels in controls (Fig. 1I). Synaptogyrin-3 is a protein of presynaptic vesicles that has the highest affinity for tau/P-tau of all synaptic proteins examined and whose binding of tau restricts synaptic vesicle mobility with consequent neural dysfunction (42). NDE levels of synaptogyrin-3 were significantly higher after acute mTBI and marginally higher in chronic mTBI than for controls (Fig. 1J).

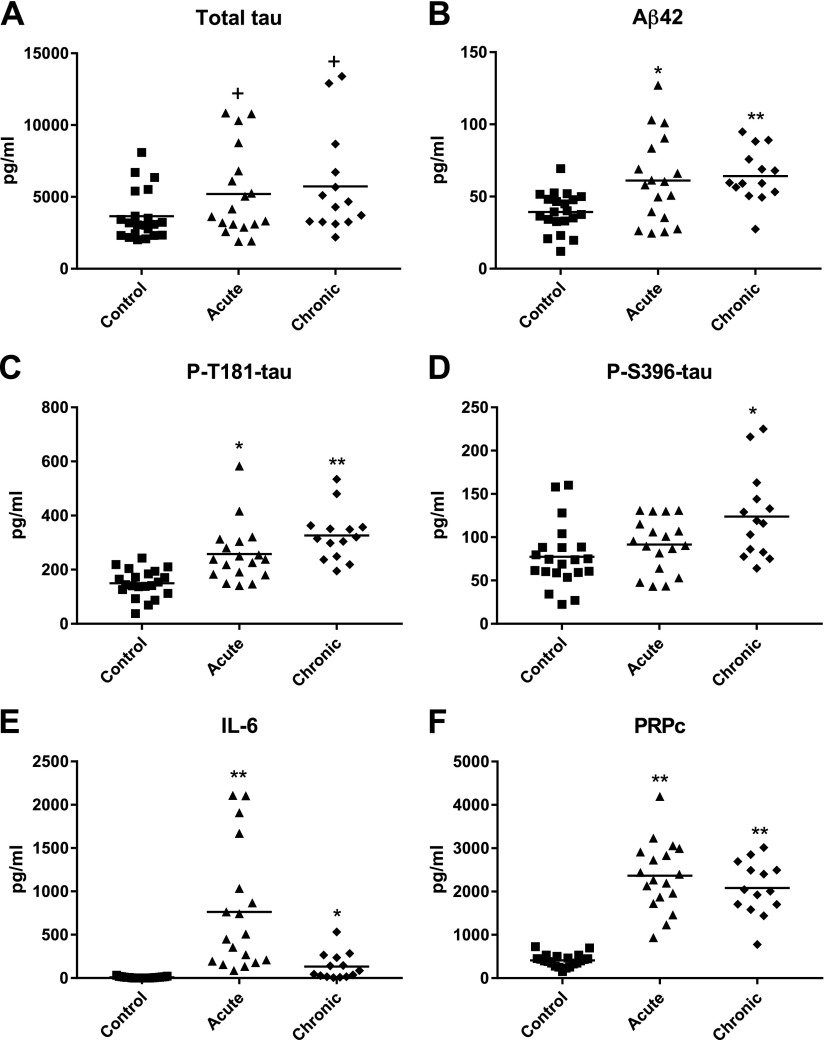

Mean NDE levels of the putatively neuropathological proteins Aβ42 and P-T181-tau were similarly higher than controls in acute and chronic mTBI (Fig. 2A–C). The mean NDE level of P-S396-tau was significantly elevated above that of controls in chronic mTBI, but not acute mTBI, and the mean level in chronic mTBI also was significantly higher than in acute mTBI (P = 0.0317) (Fig. 2D). Mean levels of total tau in NDEs of acute and chronic mTBI participants were only marginally higher than in controls (Fig. 2A). Of the 14 mTBI participants with the highest NDE levels of Aβ42 and the 16 mTBI participants with the highest NDE levels of P-T181-tau, 9 were in both groups. A significant positive correlation was found between NDE levels of Aβ42 and P-T181-tau (Spearman r = 0.630, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Levels of NDE proteinopathic cargo proteins in cross-sectional control, acute mTBI, and chronic mTBI groups. Each point represents the value for a control or mTBI participant, and the horizontal line in point clusters is the mean level for that group. Mean ± sem control, acute mTBI, and chronic mTBI participant values, respectively, are 3561 ± 378, 5260 ± 708, and 5735 ± 952 pg/ml for total tau (A); 39.4 ± 2.93, 61.1 ± 7.10, and 64.2 ± 4.87 pg/ml for Aβ42 (B); 150 ± 11.3, 257 ± 25.4, and 327 ± 25.1 pg/ml for P-T181-tau (C); 77.4 ± 7.95, 91.5 ± 7.25, and 124 ± 13.4 pg/ml for P-S396-tau (D); 8.43 ± 1.93, 763 ± 168, and 132 ± 40.6 pg/ml for IL-6 (E); and 409 ± 31.2, 2364 ± 187, and 2081 ± 165 pg/ml for PRPc (F). The significance of differences shown between values for controls and acute mTBI subjects and between controls and chronic mTBI subjects were calculated by an unpaired Student’s t test. +P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001.

IL-6 is the inflammatory cytokine most often found to be elevated in traumatic and senile degenerative diseases of the CNS. In the present series of mTBI subjects, the mean NDE levels of IL-6 were significantly increased above those of controls in both acute and chronic mTBI (Fig. 2E). PRPc binds oligomeric Aβ peptides with high affinity in a neurotoxic trimolecular complex with Fyn kinase (43, 44). The mean NDE levels of PRPc were increased significantly above those of controls with similar fold-increases in acute and chronic repetitive mTBI (Fig. 2F).

DISCUSSION

The plasma levels of NDEs were decreased significantly relative to those of controls in acute mTBI but not chronic mTBI, as assessed by counts and content of the exosome marker protein CD81 (Fig. 1A). This very unusual finding is not characteristic of neurodegenerative or neuroinflammatory diseases (45). Most changes in the levels of normally functional brain proteins quantified in NDE cargo also correlated with the phase of mTBI as mean CD81-normalized concentrations relative to those of controls were significantly abnormal for acute mTBI, but not for chronic mTBI (Fig. 1). These proteins included RAB 10 that regulates formation and activities of synaptic and other neuronal vesicles (34), UCH-L1 that facilitates removal of damaged cellular proteins (46), annexin VII and NKCC-1 that constitute and control neuronal membrane ion transporters, as well as neuronal viability (47), and fragmented AII spectrin and claudin-5 that maintain neuronal structure and tight-junctions of the BBB (39, 48) (Fig. 1B–H). The minor increase in mean NDE level of occludin in acute mTBI relative to that of controls was only marginally significant (Fig. 1G). The possibility that the decreased number of exosomes in acute mTBI might account for increases in cargo per exosome, to permit the same level of elimination of damaged proteins, could not explain changes >2-fold, such as those seen for aquaporin 4, annexin VII, or synaptogyrin-3.

Aquaporin 4 and to a lesser extent synaptogyrin-3 were the only NDE normal neurofunctional cargo proteins examined that were at significantly higher mean levels in chronic and acute mTBI subjects than in controls, but the acute mTBI levels were significantly higher than the chronic mTBI levels (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1I, J). The abnormal levels of these many native physiologically functional neuronal proteins may account in part for the decreased concentration of plasma NDEs, reduced removal of damaged proteins, altered BBB functions, and brain tissue edema characteristically observed in acute mTBI. Further, the elevations of synaptogyrin-3, which binds and concentrates tau and P-tau, in acute mTBI and to a lesser extent in chronic mTBI suggest that it may be one progression factor, which enhances early and sustained deposition of neurotoxic forms of tau in neurons and synapses. It is not yet clear if the increases in NDE levels of P-T181-tau, Aβ42, IL-6, and PRPc after acute mTBI decrease to those of controls after the acute episode, or persist or even increase after multiple acute episodes (Fig. 2).

In sharp contrast with the NDE cargo of diverse normally neurofunctional proteins increased apparently mostly for short periods by acute mTBI, NDE levels of five neuropathological proteins have been demonstrated to increase significantly after acute mTBI and remain increased in chronic mTBI (Fig. 2). Mean NDE levels of total tau were only marginally significantly higher in acute and chronic mTBI subjects relative to that of controls, although significant elevations have been reported by others in different forms of TBI (22, 49). For P-S396-tau, there was no increase in NDE levels relative to controls after acute mTBI. Mean NDE levels of Aβ42, total tau, P-T181-tau, and P-S396-tau were the same or higher in chronic mTBI than in acute mTBI. In contrast, mean NDE levels of IL-6 and PRPc were higher in acute than chronic mTBI (Fig. 2). Thus the elevated NDE levels of IL-6, which may enhance neuronal deposition of Aβ42, and of PRPc, which binds and thereby may increase local concentrations of Aβ42, may contribute both acutely and chronically to sustained formation of neurotoxic aggregates of Aβ42 peptide oligomers. As for the facilitation of tau/P-tau neurotoxicity by synaptogyrin-3, PRPc and IL-6 may represent progression factors for the neurotoxicity of Aβ42.

There are several findings here and of others that invite speculation about the possible involvement of mechanisms of acute mTBI in the initiation of changes typical of CTE. In brain tissues of humans and rodents suffering a single episode of mTBI, there are elevated levels of amyloid precursor protein, β-secretase-1 or β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1, and Aβ peptides, suggesting a role for trauma in the generation of initially diffuse deposits of amyloid that may progress in some to pathogenic plaques (20, 21). The increased levels of aquaporin 4 detected in NDEs of subjects with chronic mTBI many months following any single episode of acute mTBI suggest a role for aquaporin 4 in chronically sustained brain edema (Fig. 1I). Similarly, our finding of a higher than normal mean NDE level of synaptogyrin-3 many months after the last episode of acute mTBI suggest its possible role in the progression to chronic mTBI. The synaptogyrin-3 in presynaptic vesicles binds tau in brain tissues of neurodegenerative diseases so that tau may more effectively mediate vesicle clustering, diminish vesicle mobility, and impair neurotransmission (42). Our tentative integration of evolving data suggest that elevated NDE levels of Aβ42, P-T181-tau, and P-S396-tau in chronic mTBI reflect their direct contributions to the proteinopathic neurodegeneration of CTE. In contrast, PRPc, IL-6, and possibly aquaporin 4 and synaptogyrin-3 are progression factors that remain elevated between episodes of acute mTBI and by different mechanisms facilitate deposition of Aβ42 and P-tau species to promote development of CTE.

Many critical questions remain regarding the implications of altered levels of plasma NDE proteins in the pathobiology and management of acute mTBI and the prevention of CTE and other dementias resulting from repetitive episodes of acute mTBIs. The most prominent current issues are the predictive value of the magnitude and duration of acute changes in biomarkers for development of CTE, the value of any of these changes in identifying possible new drug targets and the applicability of such measurements in assessing efficacy of experimental treatments. Studies with much larger numbers of patients over much longer times will be required to attain clinically meaningful answers that can inform treatments. The distinctly different profiles of NDE proteins in acute mTBI and chronic mTBI presented here suggest that results of such investigations may unravel the progressive changes induced by brain injuries caused by potentially high-impact sports and occupations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Judith H. Goetzl (Geriatric Research Center, San Francisco, CA, USA) for preparation of the graphic illustrations. This research described was supported by a pilot grant from the Knoebel Institute for Healthy Aging (to A.-C.G.), and by the Intramural Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (to M.M. and D.K.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Aβ42

β-amyloid peptide 1-42

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CTE

chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- mTBI

mild traumatic brain injury

- NCAA

National Collegiate Athletic Association

- NDE

neuron-derived exosome

- NKCC-1

sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporter-1

- PRPc

prion cellular protein

- RAB10

ras-related small GTPase 10

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- UCH-L1

ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1

- DU

University of Denver

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E. J. Goetzl assisted in experimental design, generated and analyzed the laboratory data, and wrote major sections of the manuscript; F. M. Elahi assisted with laboratory studies, analyzed laboratory data, and edited the manuscript; M. Mustapic analyzed laboratory data and edited the manuscript; D. Kapogiannis assisted in experimental design and edited the manuscript; M. Pryhoda, A. Gilmore, K. A. Gorgens, and B. Davidson recruited and evaluated participants; A.-C. Granholm designed the study and edited the manuscript; and A. Ledreux evaluated patients, collected plasma, analyzed laboratory data, and edited the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Langlois J. A., Rutland-Brown W., Wald M. M. (2006) The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roozenbeek B., Maas A. I., Menon D. K. (2013) Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quillinan N., Herson P. S., Traystman R. J. (2016) Neuropathophysiology of brain injury. Anesthesiol. Clin. 34, 453–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broglio S. P., Sosnoff J. J., Shin S., He X., Alcaraz C., Zimmerman J. (2009) Head impacts during high school football: a biomechanical assessment. J. Athl. Train. 44, 342–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papa L., Ramia M. M., Edwards D., Johnson B. D., Slobounov S. M. (2015) Systematic review of clinical studies examining biomarkers of brain injury in athletes after sports-related concussion. J. Neurotrauma 32, 661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blyth B. J., Farhavar A., Gee C., Hawthorn B., He H., Nayak A., Stöcklein V., Bazarian J. J. (2009) Validation of serum markers for blood-brain barrier disruption in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 26, 1497–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higashida T., Kreipke C. W., Rafols J. A., Peng C., Schafer S., Schafer P., Ding J. Y., Dornbos D., III, Li X., Guthikonda M., Rossi N. F., Ding Y. (2011) The role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, aquaporin-4, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in blood-brain barrier disruption and brain edema after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 114, 92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obermeier B., Daneman R., Ransohoff R. M. (2013) Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Med. 19, 1584–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuriakose M., Rama Rao K. V., Younger D., Chandra N. (2018) Temporal and spatial effects of blast overpressure on blood-brain barrier permeability in traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 8, 8681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hue C. D., Cho F. S., Cao S., Nicholls R. E., Vogel Iii E. W., Sibindi C., Arancio O., Dale Bass C. R., Meaney D. F., Morrison Iii B. (2016) Time course and size of blood-brain barrier opening in a mouse model of blast-induced traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 33, 1202–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Büki A., Okonkwo D. O., Wang K. K., Povlishock J. T. (2000) Cytochrome c release and caspase activation in traumatic axonal injury. J. Neurosci. 20, 2825–2834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmy A., De Simoni M. G., Guilfoyle M. R., Carpenter K. L., Hutchinson P. J. (2011) Cytokines and innate inflammation in the pathogenesis of human traumatic brain injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 352–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodcock T., Morganti-Kossmann M. C. (2013) The role of markers of inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 4, 18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan E. B., Satgunaseelan L., Paul E., Bye N., Nguyen P., Agyapomaa D., Kossmann T., Rosenfeld J. V., Morganti-Kossmann M. C. (2014) Post-traumatic hypoxia is associated with prolonged cerebral cytokine production, higher serum biomarker levels, and poor outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 618–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gyoneva S., Ransohoff R. M. (2015) Inflammatory reaction after traumatic brain injury: therapeutic potential of targeting cell-cell communication by chemokines. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36, 471–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozano D., Gonzales-Portillo G. S., Acosta S., de la Pena I., Tajiri N., Kaneko Y., Borlongan C. V. (2015) Neuroinflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury: etiology, clinical consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon D. W., McGeachy M. J., Bayır H., Clark R. S. B., Loane D. J., Kochanek P. M. (2017) The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13, 572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roselli F., Chandrasekar A., Morganti-Kossmann M. C. (2018) Interferons in traumatic brain and spinal cord injury: current evidence for translational application. Front. Neurol. 9, 458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mettang M., Reichel S. N., Lattke M., Palmer A., Abaei A., Rasche V., Huber-Lang M., Baumann B., Wirth T. (2018) IKK2/NF-κB signaling protects neurons after traumatic brain injury. FASEB J. 32, 1916–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeKosky S. T., Blennow K., Ikonomovic M. D., Gandy S. (2013) Acute and chronic traumatic encephalopathies: pathogenesis and biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 192–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blasko I., Beer R., Bigl M., Apelt J., Franz G., Rudzki D., Ransmayr G., Kampfl A., Schliebs R. (2004) Experimental traumatic brain injury in rats stimulates the expression, production and activity of Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase (BACE-1). J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 111, 523–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stern R. A., Tripodis Y., Baugh C. M., Fritts N. G., Martin B. M., Chaisson C., Cantu R. C., Joyce J. A., Shah S., Ikezu T., Zhang J., Gercel-Taylor C., Taylor D. D. (2016) Preliminary study of plasma exosomal Tau as a potential biomarker for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 51, 1099–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prince C., Bruhns M. E. (2017) Evaluation and treatment of mild traumatic brain injury: the role of neuropsychology. Brain Sci. 7: e105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy D., Vaishnavi S., Han D., Rao V. (2017) Correlates and prevalence of aggression at six months and one year after first-time traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 29, 334–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dailey N. S., Smith R., Bajaj S., Alkozei A., Gottschlich M. K., Raikes A. C., Satterfield B. C., Killgore W. D. S. (2018) Elevated aggression and reduced white matter integrity in mild traumatic brain injury: a DTI Study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agoston D. V., Shutes-David A., Peskind E. R. (2017) Biofluid biomarkers of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 31, 1195–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werhane M. L., Evangelista N. D., Clark A. L., Sorg S. F., Bangen K. J., Tran M., Schiehser D. M., Delano-Wood L. (2017) Pathological vascular and inflammatory biomarkers of acute- and chronic-phase traumatic brain injury. Concussion 2, CNC30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H. J., Tsao J. W., Stanfill A. G. (2018) The current state of biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury. JCI Insight 3: 97105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruff R. M., Iverson G. L., Barth J. T., Bush S. S., Broshek D. K.; NAN Policy and Planning Committee (2009) Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 24, 3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maroon J. C., Lovell M. R., Norwig J., Podell K., Powell J. W., Hartl R. (2000) Cerebral concussion in athletes: evaluation and neuropsychological testing. Neurosurgery 47, 659–669; discussion 669–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galetta K. M., Liu M., Leong D. F., Ventura R. E., Galetta S. L., Balcer L. J. (2015) The King-Devick test of rapid number naming for concussion detection: meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Concussion 1, CNC8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapogiannis D., Boxer A., Schwartz J. B., Abner E. L., Biragyn A., Masharani U., Frassetto L., Petersen R. C., Miller B. L., Goetzl E. J. (2015) Dysfunctionally phosphorylated type 1 insulin receptor substrate in neural-derived blood exosomes of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 29, 589–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mustapic M., Eitan E., Werner J. K., Jr., Berkowitz S. T., Lazaropoulos M. P., Tran J., Goetzl E. J., Kapogiannis D. (2017) Plasma extracellular vesicles enriched for neuronal origin: a potential window into brain pathologic processes. Front. Neurosci. 11, 278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucci C., Alifano P., Cogli L. (2014) The role of rab proteins in neuronal cells and in the trafficking of neurotrophin receptors. Membranes (Basel) 4, 642–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creutz C. E. (1992) The annexins and exocytosis. Science 258, 924–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson P., Thompson R. J. (1981) The demonstration of new human brain-specific proteins by high-resolution two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Neurol. Sci. 49, 429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papa L., Lewis L. M., Silvestri S., Falk J. L., Giordano P., Brophy G. M., Demery J. A., Liu M. C., Mo J., Akinyi L., Mondello S., Schmid K., Robertson C. S., Tortella F. C., Hayes R. L., Wang K. K. (2012) Serum levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase distinguish mild traumatic brain injury from trauma controls and are elevated in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury patients with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 72, 1335–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huh G. Y., Glantz S. B., Je S., Morrow J. S., Kim J. H. (2001) Calpain proteolysis of alpha II-spectrin in the normal adult human brain. Neurosci. Lett. 316, 41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unsain N., Stefani F. D., Cáceres A. (2018) The actin/spectrin membrane-associated periodic skeleton in neurons. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 10, 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagelhus E. A., Ottersen O. P. (2013) Physiological roles of aquaporin-4 in brain. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1543–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hladky S. B., Barrand M. A. (2014) Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS 11, 26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McInnes J., Wierda K., Snellinx A., Bounti L., Wang Y. C., Stancu I. C., Apostolo N., Gevaert K., Dewachter I., Spires-Jones T. L., De Strooper B., De Wit J., Zhou L., Verstreken P. (2018) Synaptogyrin-3 mediates presynaptic dysfunction induced by Tau. Neuron 97, 823–835.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larson M., Sherman M. A., Amar F., Nuvolone M., Schneider J. A., Bennett D. A., Aguzzi A., Lesné S. E. (2012) The complex PrP(c)-Fyn couples human oligomeric Aβ with pathological tau changes in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 16857–16871a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Rubenstein R., Chang B., Grinkina N., Drummond E., Davies P., Ruditzky M., Sharma D., Wang K., Wisniewski T. (2017) Tau phosphorylation induced by severe closed head traumatic brain injury is linked to the cellular prion protein. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 5, 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah R., Patel T., Freedman J. E. (2018) Circulating extracellular vesicles in human disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 958–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tongaonkar P., Chen L., Lambertson D., Ko B., Madura K. (2000) Evidence for an interaction between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and the 26S proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4691–4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoque M., Rentero C., Cairns R., Tebar F., Enrich C., Grewal T. (2014) Annexins - scaffolds modulating PKC localization and signaling. Cell. Signal. 26, 1213–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morita K., Furuse M., Fujimoto K., Tsukita S. (1999) Claudin multigene family encoding four-transmembrane domain protein components of tight junction strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 511–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stern R. A. (2016) Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in postconcussion syndrome: measuring neuronal injury and distinguishing individuals at risk for persistent postconcussion syndrome or chronic traumatic encephalopathy. JAMA Neurol. 73, 1280–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]