Abstract

Many enzymes catalyse reactions that proceed through covalent acyl–enzyme (ester or thioester) intermediates1. These enzymes include serine hydrolases2,3 (encoded by one per cent of human genes, and including serine proteases and thioesterases), cysteine proteases (including caspases), and many components of the ubiquitination machinery4,5. Their important acyl–enzyme intermediates are unstable, commonly having half-lives of minutes to hours6. In some cases, acyl–enzyme complexes can be stabilized using substrate analogues or active-site mutations but, although these approaches can provide valuable insight7–10, they often result in complexes that are substantially non-native. Here we develop a strategy for incorporating 2,3-diaminopropionic acid (DAP) into recombinant proteins, via expansion of the genetic code11. We show that replacing catalytic cysteine or serine residues of enzymes with DAP permits their first-step reaction with native substrates, allowing the efficient capture of acyl–enzyme complexes that are linked through a stable amide bond. For one of these enzymes, the thioesterase domain of valinomycin synthetase12, we elucidate the biosynthetic pathway by which it progressively oligomerizes tetradepsipeptidyl substrates to a dodecadepsipeptidyl intermediate, which it then cyclizes to produce valinomycin. By trapping the first and last acyl–thioesterase intermediates in the catalytic cycle as DAP conjugates, we provide structural insight into how conformational changes in thioesterase domains of such nonribosomal peptide synthetases control the oligomerization and cyclization of linear substrates. The encoding of DAP will facilitate the characterization of diverse acyl–enzyme complexes, and may be extended to capturing the native substrates of transiently acylated proteins of unknown function.

We hypothesized that selectively replacing the sulfhydryl or hydroxyl groups in catalytic cysteine or serine residues with an amino group, making 2,3-diaminopropionic acid (DAP, 1), would allow the trapping of acyl–enzyme intermediates that are linked through an amide bond (Fig. 1a, b). Within peptides, the conjugate acid of the β-amino group of DAP has reported pK as between 6.3 and 7.5 (compared with the conjugate acid of the ε-amino group of lysine, which has a pK a of 10.5)13. This suggests that the β-amino group of DAP could act as a nucleophile, and may form amide bonds with enzymes’ substrates. The half-life of amides in aqueous solution is about 500 years14, so the amide analogues of labile thioester and ester intermediates should be substantially stabilized, such that subsequent reactions with nucleophiles or solvent should be severely attenuated or abolished (Fig. 1b).

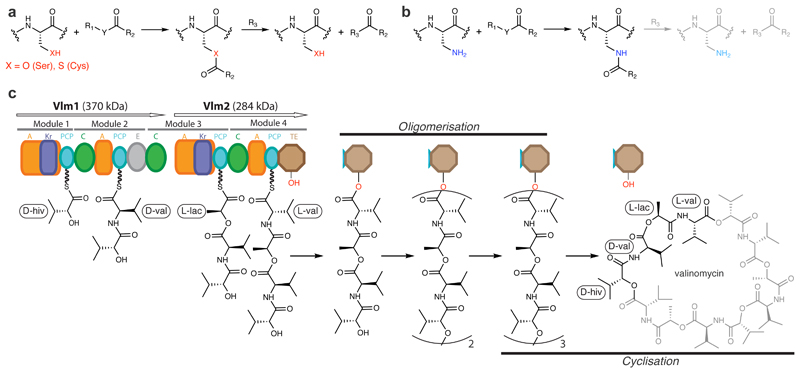

Fig. 1. Capturing transient acyl–enzyme intermediates with DAP, and the proposed biosynthesis of valinomycin.

a, Active-site serine or cysteine residues react with carbonyl groups to form tetrahedral intermediates (not shown) that collapse to acyl–enzyme intermediates by loss of R1–YH. Attack by nucleophilic R3 groups (commonly a hydroxyl, amine or thiol) releases the bound substrate fragment and regenerates the enzyme. R1, R2, and Y each represent the diverse chemical groups that may be found in distinct reactants. b, Replacing cysteine or serine with DAP may result in a first acyl–enzyme intermediate that is resistant to cleavage. c, Valinomycin synthetase (Vlm) condenses d-α-hydroxyisovaleric acid (d-α-hiv), d-valine (d-val), l-lactic acid (l-lac) and l-valine (l-val) to form the tetradepsipeptidyl (d-hiv–d-val–l-lac–l-val) intermediate. d-α-hiv and l-lac arise from the reduction of precursor ketoacyl moieties by ketoreductase (KR) domains. Tetradepsipeptidyl intermediates are oligomerized to a dodecadepsipeptidyl intermediate which is cyclized, by the terminal TE domain, to produce valinomycin. Vlm1 and Vlm2 are the two protein subunits that form valinomycin synthetase. A module is a set of domains which work together to add one monomer to the growing depsipeptide. A, adenylation domain; C, condensation domain; PCP, peptidyl carrier protein domain. See Extended Data Fig. 1 for a synthetic cycle of an NRPS.

The secondary-metabolite-producing nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs) generate complex acyl–enzyme intermediates during their synthetic cycles15. These megaenzymes use thio-templated pathways to assemble small acyl molecules into a broad array of biologically active natural products, including antitumour compounds, antibiotics, antifungals and immunosuppressants (Extended Data Fig. 1). Unravelling their molecular mechanisms has been hampered by the challenge of characterizing their multiple acyl–enzyme intermediates at high resolution.

This challenge is exemplified by the thioesterase (TE) domains16 from NRPS pathways that oligomerize and cyclize linear peptidyl substrates17, including the TE domain from valinomycin synthetase (Fig. 1c)12. This enzyme—a two-protein, four-module NRPS—alternatively links hydroxy acids (from in situ reduction of α-keto acids) and amino acids into a tetradepsipeptide intermediate, which the thioesterase domain (Vlm TE) oligomerizes up to, but not beyond, the dodecadepsipeptide. Vlm TE then cyclizes the dodecadepsipeptide to release valinomycin12,18 (a potassium ionophore with antimicrobial, antitumoural and cytotoxic properties; Fig. 1c). The oligomerizations and cyclization must be rapid enough to prevent substantial spontaneous hydrolysis to linear depsipeptides, which are useless side products.

High-resolution structures of acyl–TE intermediates in valinomycin biosynthesis could provide mechanistic insight into how thioesterases control substrate fate. A handful of high-resolution acyl–TE structures have been obtained, most notably with the polyketide pikromycin-forming TE and non-native substrate analogues (Supplementary Data 1)19. These have helped to identify the putative oxyanion hole and demonstrated the interaction of the ‘lid’ element of the TE domain with the substrate. However, structural studies of TE domains have been hampered by several factors, especially the hydrolysis rates of acyl–TE intermediates20,21, which are high by comparison with the crystallographic timescale.

Here we develop a strategy for the site-specific incorporation of DAP into recombinant proteins, and demonstrate the efficient capture of acyl–enzyme intermediates for a cysteine protease and Vlm TE. We elucidate the biosynthetic pathway for converting tetradepsipeptides to valinomycin, and structurally characterize deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–N-TEDAP and dodecadepsipeptidyl–N-TEDAP conjugates to provide insights into the first and last acyl–TE intermediates in the catalytic cycle of Vlm TE. Our results reveal how the fate of substrates may be determined by conformational changes in the TE domains of NRPSs that oligomerize and cyclize linear precursors.

The structural similarity of DAP (1) to cysteine and serine makes it challenging to discover an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase that is selective for DAP in vivo. We therefore created five protected versions of DAP (2–6; Extended Data Fig. 2a), for which we anticipated that the successful discovery of specific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNACUA pairs would enable site-specific incorporation into proteins. The subsequent post-translational deprotection22,23 would reveal DAP. We found that 2–5 accumulated in Escherichia coli at low concentrations (less than 10 μM; Extended Data Fig. 2b–e) and we were unable to evolve a synthetase for these noncanonical amino acids using several libraries of the orthogonal Methanosarcina barkeri (Mb) pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylRS)/tRNAPyl CUA pair11 (Supplementary Methods). By contrast, 6 accumulated in E. coli at millimolar concentrations and we were able to evolve an Mb PylRS variant (named DAPRS, containing mutations Y271C, N311Q, Y349F and V366C) for the site-specific incorporation of 6 (Extended Data Fig. 2f–h). The DAPRS/tRNAPyl CUA pair enabled the synthesis of green fluorescent protein (GFP) containing 6 at position 150 (GFP150(6); Fig. 2a) in good yield24. Photo-deprotection of GFP150(6) and subsequent incubation converted 6 to 1 in GFP (Fig. 2b, c).

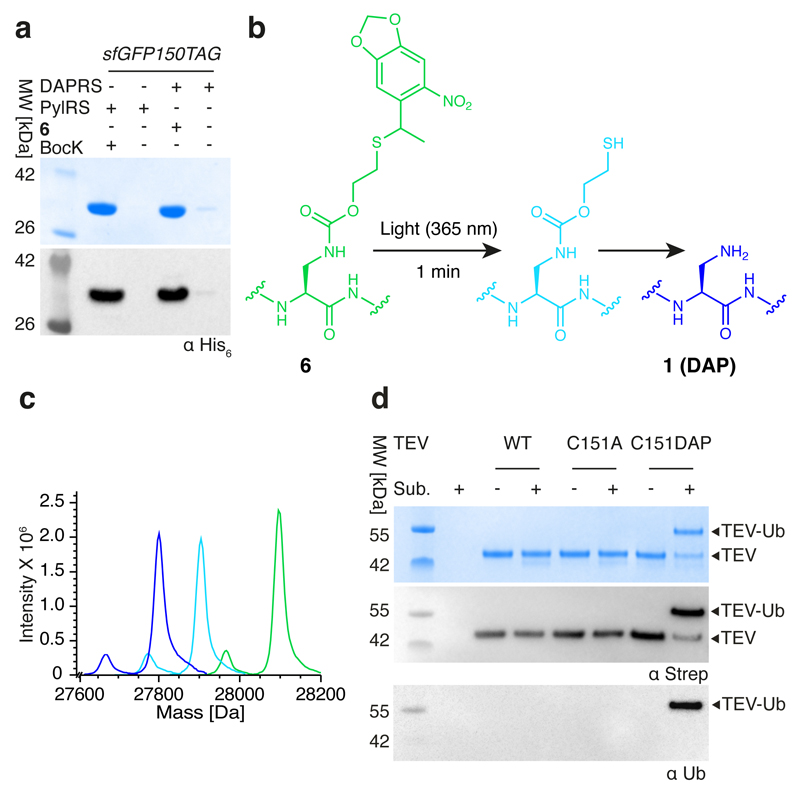

Fig. 2. Genetically directing DAP incorporation in recombinant proteins and stably trapping the acyl–enzyme intermediate of a cysteine protease.

a, SDS–PAGE gels of GFP150 (6) and GFP150 (BocK), with protein detected by Coomassie staining (top gel) or anti-His6 antibody (bottom gel); the experiment was performed in two biological replicates with similar results. We used the indicated enzymes (DAPRS and PylRS) with their cognate tRNACUA and amino acids (6 and BocK (Nε-[(tert-butoxy)carbonyl]-l-lysine) together with an sfGFP150TAG reporter construct. b, Encoded 6 was photo-deprotected, leading to an intermediate, which spontaneously fragments to reveal DAP. c, Deprotection of 6 in sfGFP followed by electrospray ionization–mass spectroscopy (ESI–MS) analysis. Green trace, purified GFP150(6): expected molecular mass 28,096.27 Da; observed 28,097.21 Da. Light blue trace, intermediate: expected 27,902.22 Da; observed 27904.14 Da. Dark blue trace, incubation (10 h, 37 °C) converts the intermediate to DAP (1): expected 27,798.23 Da; observed 27,800.88 Da. Minor peaks resulting from loss of the N-terminal methionine are also observed. The experiment was performed in two biological replicates with similar results. d, TEV protease variants were incubated with Ub–tev–His. TEV(C151DAP)–Ub is the amide-bond-linked complex. Anti-Ub and anti-strep western blots confirm the identity of the complex (TEV constructs contain a streptavidin tag). The experiment was performed in two biological replicates with similar results.

Cysteine proteases, including the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, react with substrates through a catalytic cysteine to generate an intermediate in which the protease is linked to the amino-terminal portion of its substrate through a thioester4. We replaced the active-site cysteine 151 of TEV protease with DAP, by genetically encoding 6 and deprotecting it, creating TEV(C151DAP). Incubating TEV(C151DAP) with Ub–tev–His6, a model substrate in which the cleavage site recognized by TEV protease (tev) is flanked by ubiquitin (Ub) and a hexahistidine tag (His6), led to cleavage of the His6 tag from ubiquitin and formation of a covalently linked TEV(C151DAP)–Ub conjugate (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3a–c). Control experiments demonstrated that the stable conjugate was dependent on DAP incorporation. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) demonstrated amide-bond formation between DAP and ubiquitin (Extended Data Fig. 3d). These results demonstrate that substitution of the catalytic cysteine in TEV with DAP creates a protease that performs the first step of the protease cycle, releasing the carboxy-terminal fragment of the substrate and leaving the amino-terminal fragment covalently attached to the protease through a stable amide bond that is resistant to hydrolysis.

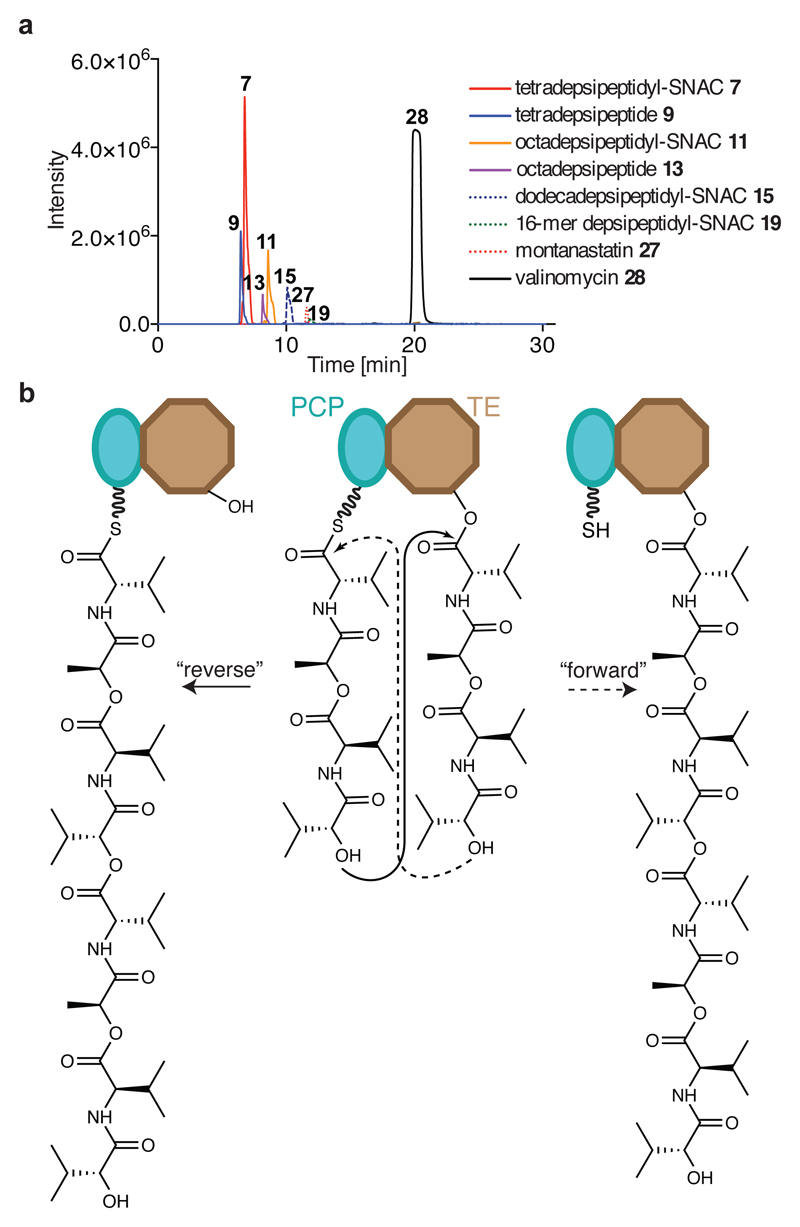

To gain insight into the function of the TE domain and to prepare it for use with the DAP system, we expressed and purified wild-type Vlm TE (TEwt). We found that Vlm TE can use a N-acetylcysteine (SNAC) derivative of the native depsipeptide (tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC, 7; Extended Data Fig. 4) to complete all stages of its catalytic cycle and yield valinomycin (Figs 1c, 3a and Extended Data Fig. 5). Thus, 7 can mimic the natural phosphopantetheine–peptidyl carrier protein (PCP)-linked substrate, consistent with prior observations of other TE domains and substrates17,21,25.

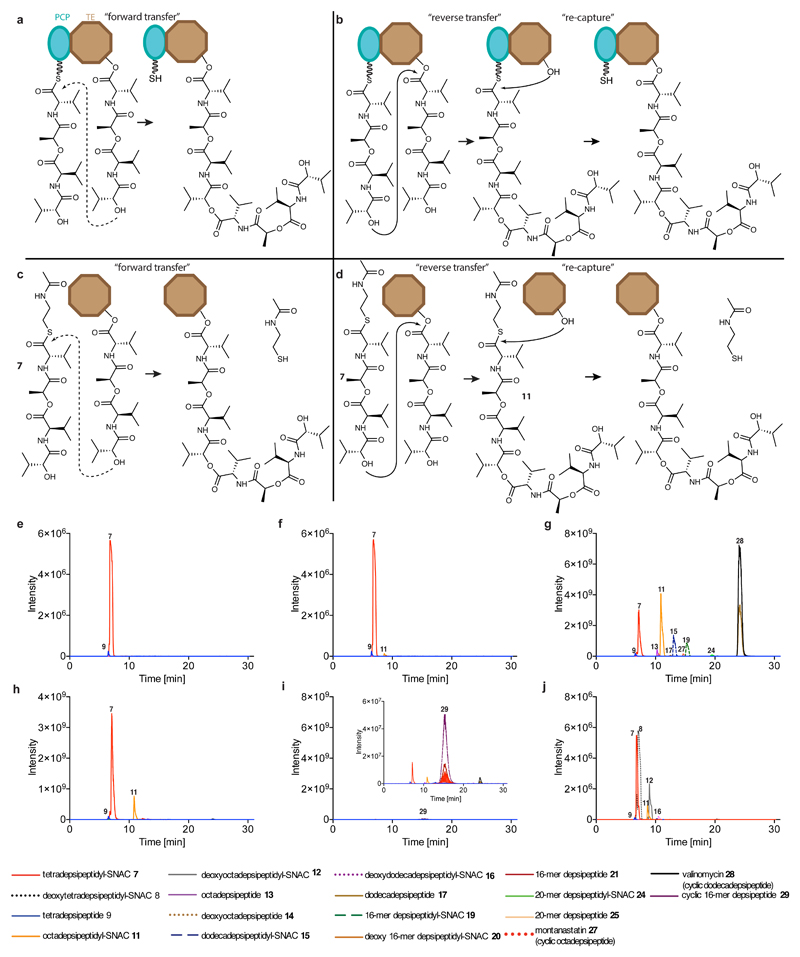

Fig. 3. Vlm TE produces valinomycin and intermediates that delineate the oligomerization pathway from tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC.

a, Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) from high-resolution (HR)–liquid chromatography (LC)–ESI–MS of reactions of tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (7; 1.7 mM) and Vlm TE (6.5 μM); TEwt produces valinomycin as its major product. The experiment was performed two independent times with similar results. See ‘Supplementary Methods for Statistics and Reproducibility’ for mass analysis and deviations from calculated m/z values. b, Two scenarios for oligomerization17,26. In the ‘forward transfer’ scenario, the distal hydroxyl group of tetradepsipeptidyl–O-TE (TE) attacks (dotted line) the thioester group in tetradepsipeptidyl–S-PCP (PCP), directly forming octadepsipeptidyl–O-TE (right). In the ‘reverse’ scenario, the distal hydroxyl group of tetradepsipeptidyl–S-PCP attacks the ester group in tetradepsipeptidyl–O-TE, forming octadepsipeptidyl–S-PCP (left), which would later be transferred onto the TE domain serine. Our data are consistent with the ‘reverse’ oligomerization scenario; see also Extended Data Fig. 5.

There are two possible pathways for the oligomerization of NRPS intermediates by TE domains, and analysis of the synthetic intermediates detected in valinomycin synthesis revealed that Vlm TEwt catalyses oligomerization via a ‘reverse transfer’ pathway (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Discussion 1). This pathway is analogous to that used by the more canonical gramicidin S synthetase17,26 and we suggest that nearly all oligomerizing–cyclizing NRPSs (or PKSs27) will use this synthetic scheme.

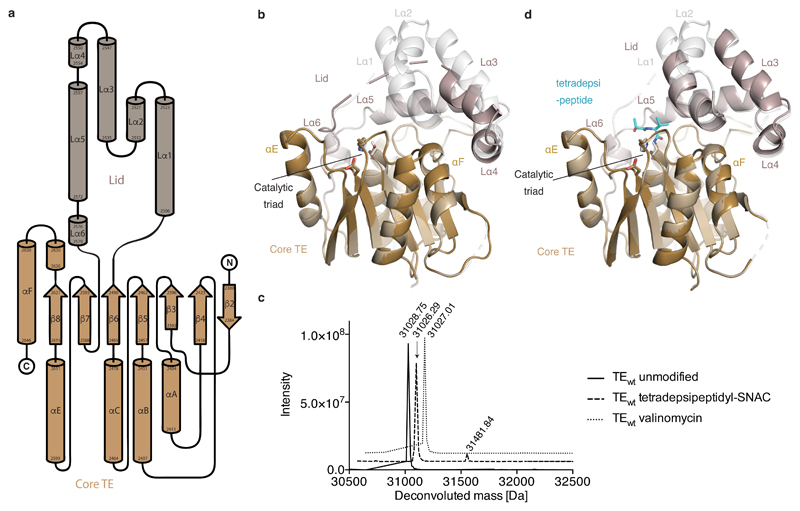

We next obtained the structure of Vlm TEwt (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Extended Data Table 1). It adopts the α/β-hydrolase fold typical of type I TE domains, with a canonical serine–histidine–aspartate catalytic triad16 covered by the TE ‘lid’. The lid is a mobile element with proposed roles that include substrate positioning and solvent exclusion21,28,29. The lid of Vlm TE is large, composed of an extended loop, three helices (Lα1–3, seen here as a bundle), a five-residue helix (Lα4), a long helix (Lα5) and another short helix (Lα6) (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). We obtained another structure of TEwt that differs only in the lid. In the first, the lid is nearly completely ordered, although the B factors are markedly higher for the Lα1–4 region, which makes almost no contact with the rest of the domain (Extended Data Fig. 6b). In the second structure, Lα4–5 have similar positions to those in the first structure, whereas Lα3 is rotated 10° towards the active site and Lα1–2 are too disordered to model.

Incubating Vlm TE with depsipeptidyl–SNACs did not yield stable conjugates (Extended Data Fig. 6c), and attempts to soak TEwt crystals with depsipeptidyl–SNACs failed to reveal interpretable ligand electron density in the active site or conformational changes. Others have reported similar setbacks when attempting to visualize acyl–enzyme complexes from SNAC molecules (Supplementary Data 1)20,21. We conclude that acyl intermediates in valinomycin biosynthesis are not stable, and that it is exceptionally challenging to use wild-type Vlm TE to visualize biosynthetic intermediates.

We therefore produced Vlm TE in which the active-site serine 2,463 was replaced by DAP (TEDAP; Extended Data Fig. 7a–c) in order to capture stable acyl–TE conjugates (Fig. 4). To provide insight into the first acyl–thioesterase intermediate in the catalytic cycle of Vlm TE, we captured tetradepsipeptidyl–N-TEDAP: incubation of TEDAP with tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (7) led to production of a stable depsipeptidyl–TEDAP intermediate at more than 60% yield (Extended Data Fig. 7d), and we did not observe valinomycin synthesis. However, remarkably, we did observe a small amount of octadepsipeptidyl–SNAC (11; Extended Data Fig. 5f, h). 11 is probably formed by enzyme-catalysed attack of the tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC’s hydroxyl group on the amide bond that links the tetradepsipeptide to TEDAP. The attack of a hydroxyl on an amide is analogous to the first reaction used by related serine proteases30, but it is surprising that this TE domain is capable of catalysing a more demanding chemical reaction (amide cleavage) than the reaction (ester hydrolysis) it evolved to perform. In an effort to enhance conjugate yield, we optimized the conditions for conjugating deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC 8 with TEDAP, which produced (about 70%) the deoxy-depsipeptidyl–TEDAP conjugate (Fig. 4a). The marginal solubility of these hydrophobic SNACs may limit the conjugation efficiency.

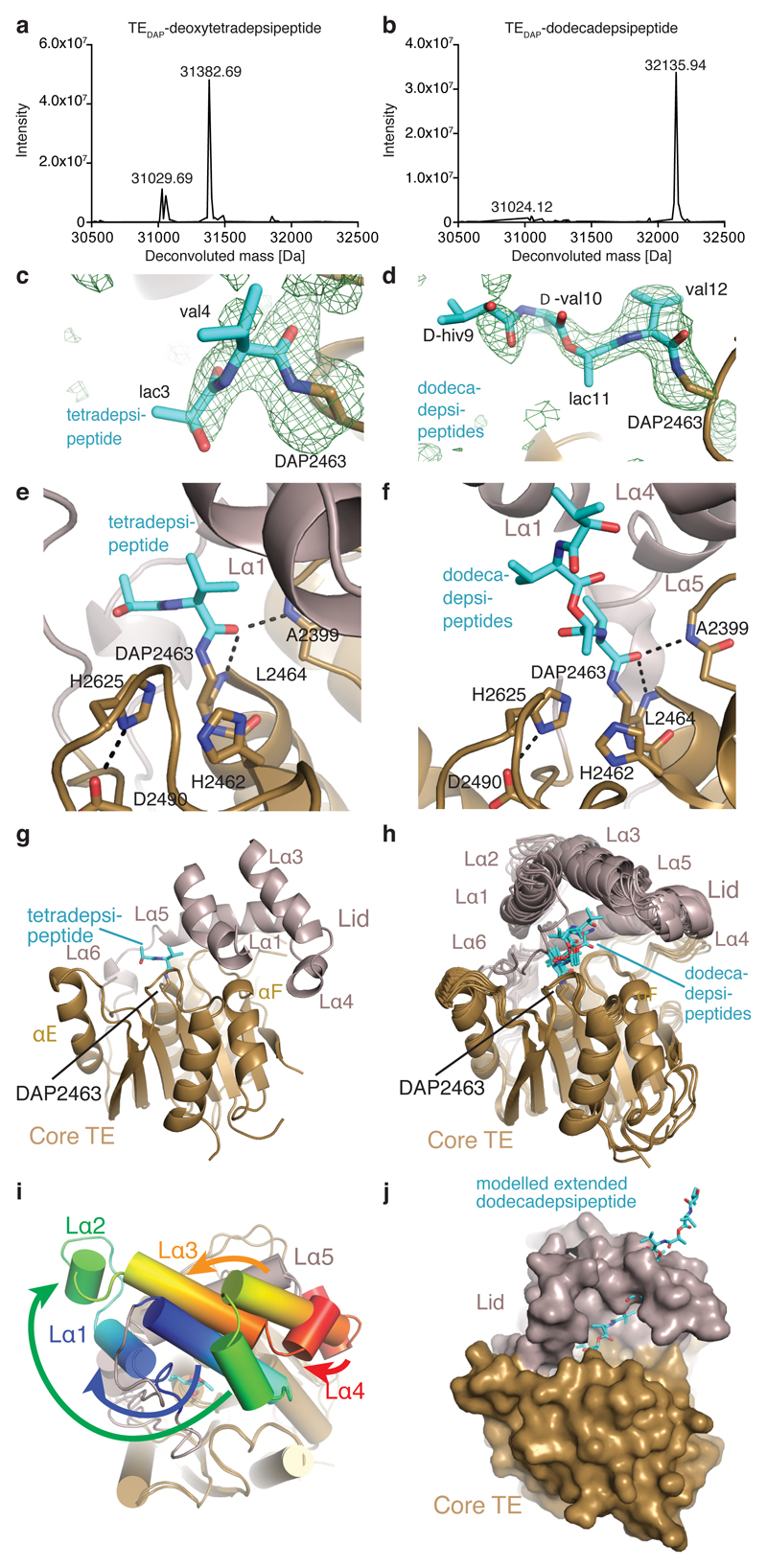

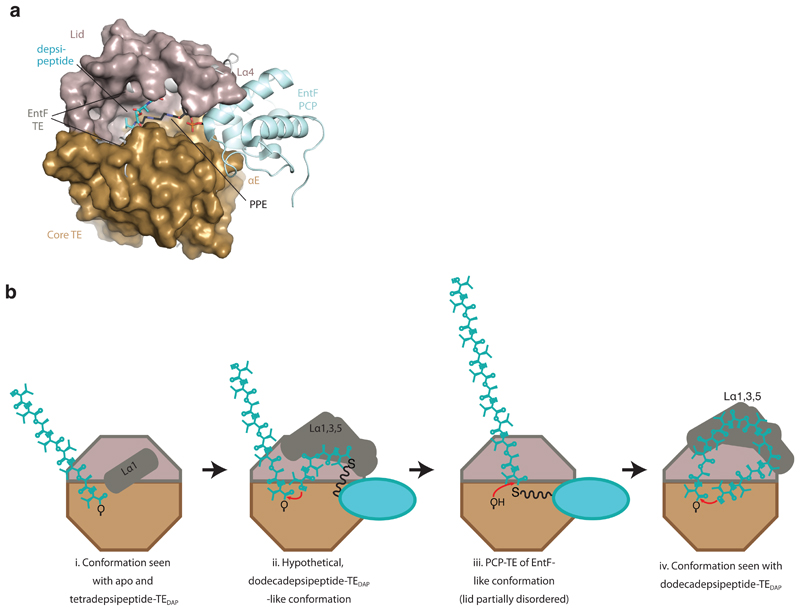

Fig. 4. Crystal structures of complexes of TEDAP.

a, b, Deconvoluted mass spectra. a, TEDAP incubated with deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (8). Expected molecular masses 31,027.24 Da (unmodified) and 31,383.70 Da (modified); observed 31,029.69 Da and 31,382.69 Da. b, TEDAP incubated with valinomycin. Expected molecular masses 31,027.24 Da (unmodified) and 32,139.11 Da (modified); observed 31,024.12 Da and 32135.94 Da. The experiments were repeated independently five times with similar results. c, d, Unbiased electron-density (mFo–DFc) maps (green mesh, 2.5σ) for depsipeptide residues of tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (c, Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession number 6ECD) and dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (d; 6ECE and 6ECF). An amide bond links DAP (brown) and depsipeptide residues (cyan). e, f, The active sites of tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (e) and dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (f). The carbonyl oxygen of the amide formed by DAP and valine 4 (e) or valine 12 (f) is positioned close to the oxyanion hole formed by the main chain of A2,399 and L2,464. Catalytic triad residues H2,625 and D2,490 are shown as sticks. g, The lid of tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (6ECD) is in a similar position to that seen in TEwt (6ECB; not shown). h, All crystallographically independent molecules of the dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (6ECE and 6ECF) are in a set of similar conformations, distinct from that seen in TEwt. i, Substantial conformational changes occur in lid helixes Lα1–Lα4 between the conformations of tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (g) and dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (h). See also Supplementary Videos 1 and 2. j, In the dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP structure, the lid sterically prevents the dodecadepsipeptide from extending out in a linear fashion, instead favouring it curling back through this steric block and forming largely hydrophobic, nonspecific interactions with the lid.

To determine the structure of the deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–N-TEDAP conjugate, we incubated TEDAP crystals with the deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (8). The resulting electron density shows somewhat weak but unambiguous density for an amide bond between DAP 2,463 and l-valine 4 of the deoxy-tetradepsipeptide (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 8a). The carbonyl oxygen of the l-valine 4 is close to backbone amides of residues alanine 2,399 and leucine 2,464—the putative oxyanion hole (Fig. 4e)25. There is also density for the next residue, l-lactic acid 3 (l-lac3), but it is insufficient to reliably model d-valine 2 and d-α-hydroxyisovaleric acid 1 (d-hiv1) as the deoxy-tetradepsipeptide arcs out, indicating substrate flexibility. The deoxy-tetradepsipeptide does not make any interactions with the lid, which is in a conformation nearly identical to that in the first TEwt (apo) structure (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 6d).

Next, we sought insight into the last acyl–TE intermediate in the catalytic cycle. Upon incubation of valinomycin and TEDAP, we captured dodecadepsipeptidyl–N-TEDAP at about 65–100% yield, formed through a ring-opening reaction analogous to the reverse of the natural cyclization (Fig. 4b). This reaction is thermodynamically favoured by virtue of amide-bond formation. Dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP produced crystals in similar conditions to those of TEwt, but with a different morphology and belonging to two different space groups (H3 and P1, with two and six molecules per asymmetric unit, respectively; Extended Data Table 1). All eight crystallographically independent molecules of dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP showed some density for the dodecadepsipeptide. Molecules P1_A–F and H3_A–B show strong density for four, three, two, two, two, two, three and one dodecadepsipeptide residues respectively (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 8b–i). Additional weaker density is present in some molecules, which could accommodate up to the full 12 residues (Extended Data Fig. 8j–l); in others, weaker density suggests multiple conformations for the distal residues, but they were not possible to definitively model. The modelled depsipeptides all follow a similar trajectory away from the active site. There is no consistent interaction between the depsipeptide beyond the l-valine residue attached to DAP and the TE domain (Fig. 4f, h). Rather, each depsipeptide makes different contacts with the lid. The lid forms a semi-sphere-like pocket/steric barrier made up of helices Lα1, 3, 4 and 5, and the strand amino-terminal to Lα1. The lid of each crystallographically independent molecule of dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP is in a similar but nonidentical position, and the loops between lid helices are disordered in most molecules (Fig. 4h). This again highlights the mobility of the lid and explains why the conformation and extent of order of dodecadepsipeptides differ between molecules (Fig. 4h). The semi-sphere-like barrier occurs only because of a major rearrangement of the lid in the dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP structures with respect to the conformation of the lid seen in both the apo and tetradepsipeptidyl-bound structures of Vlm TE.

Comparing the position of the Vlm TE lid in the apo and tetradepsipeptide-bound structures with the position of the lid in the dodecadepsipeptide-bound structures demonstrates and emphasizes its extreme mobility. To transition from one lid conformation to the other, helices Lα5–6 maintain their position, Lα3–4 rotate by about 45° and translocate roughly 13 Å, Lα2 translocates roughly 25 Å, and Lα1 shortens, translocates about 13 Å and rotates more than 90° in the opposite direction to Lα3–4 (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Videos 1, 2). This dramatic rearrangement means that the lid helices pack together in a markedly different manner in the apo/tetradepsipeptidyl-bound structure and in dodecadepsipeptidyl-bound conformations.

The distinct lid conformations directly influence the possible location of the depsipeptide. In the apo/tetradepsipeptide-bound conformation of the lid, the carboxyl terminus of Lα1 comes within 10 Å of serine/DAP2,463, leading the tetradepsipeptide to extend towards the TE core helix αE. In the dodecadepsipeptide-bound conformations of the lid, the loop adjacent to Lα1 blocks the location occupied by the tetradepsipeptide in the tetradepsipeptide-bound structure. Moreover, in the dodecadepsipeptide-bound structure the amino terminus of Lα1 forms part of the semi-sphere-like pocket. This pocket probably helps to curl the dodecadepsipeptide back towards serine/DAP 2,463, entropically controlling cyclization as part of the oligomerization/cyclization pathway (Fig. 4j, Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Discussion 2).

In summary, we have genetically encoded DAP in place of catalytic cysteine or serine residues to capture unstable thioester or ester intermediates as stable amide analogues. We have exemplified the utility of this approach for a cysteine protease and a thioesterase, and provided unique insight into intermediates in the synthesis of valinomycin: a massive lid rearrangement that is associated with the dodecadepsipeptidyl-bound Vlm TE reorients the substrate from its position during oligomerization and places it into a pocket that entropically controls cyclization. Importantly, the DAP system allows the formation of near-native acyl–enzyme complexes with widely used, reaction-competent substrates (for example, native proteins containing protease sites), substrate analogues (here SNACs), and commercially available natural products (here valinomycin, and probably other cyclic products25). We anticipate that the approach will be broadly applicable and may be extended to capturing native substrates of transiently acylated proteins of unknown function.

Extended Data

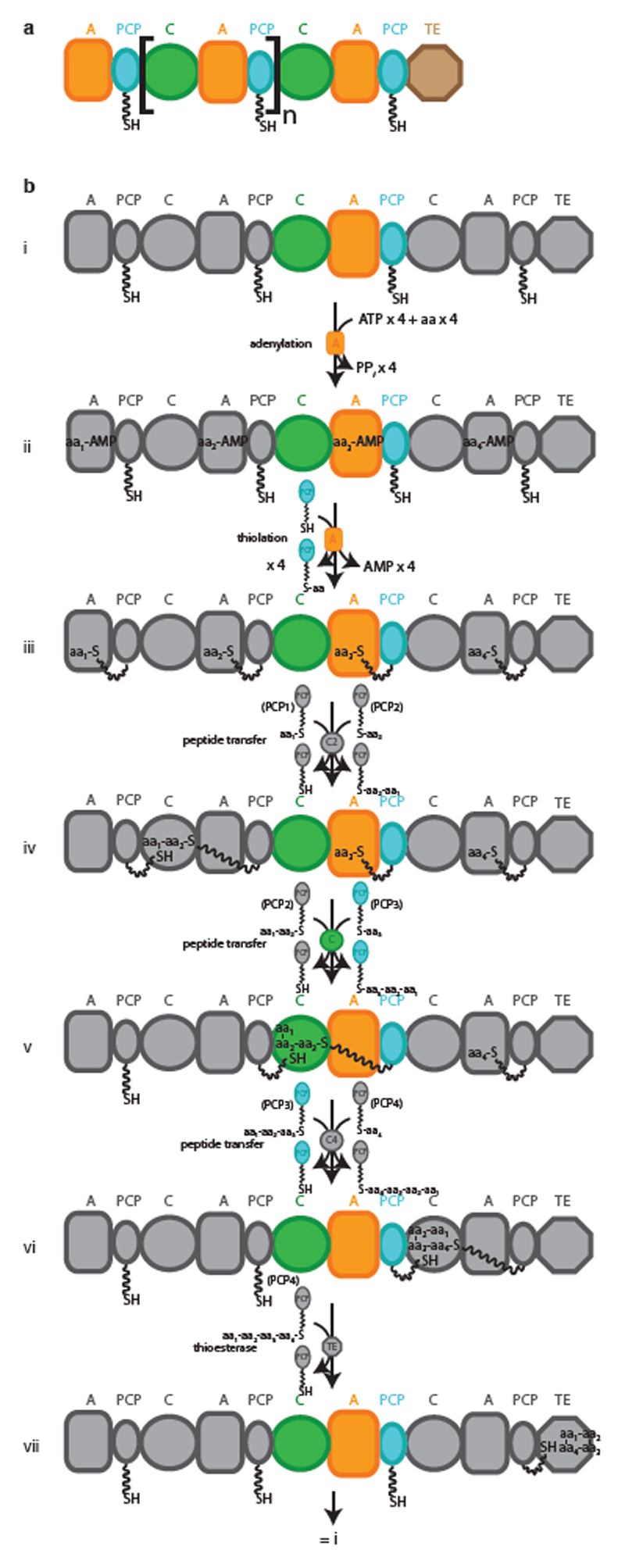

Extended Data Fig. 1. Schematic representation and reaction cycle of a canonical NRPS.

a, Schematic representation of a generic type I NRPS. The square brackets denote a single module. b, i–vii, Synthetic cycle of a canonical elongation module. NRPSs assemble peptides from amino acyl and other small acyl building blocks using a modular and thio-templated logic. A canonical NRPS is composed of one module for every residue in the peptide product. The initiation module contains an adenylation (A) domain, which binds cognate acyl substrate and performs adenylation and transfer of that substrate as a thioester on the phosphopantetheine arm (PPE, shown as a wavy line) of a peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain, for transport between active sites. Each elongation module contains an A and a PCP domain, and also a condensation (C) domain, which condenses aminoacyl and peptidyl substrates bound to PCP domains, thus progressively elongating the nascent chain. Termination modules contain C, A and PCP domains, and a specialized terminating/offloading domain responsible for the release of the peptide in its final form. The most common and most versatile terminating domain in NRPSs is the TE domain. Similar TE domains terminate synthesis in polyketide and fatty acid synthases. PPi, diphosphate; aa, amino acid.

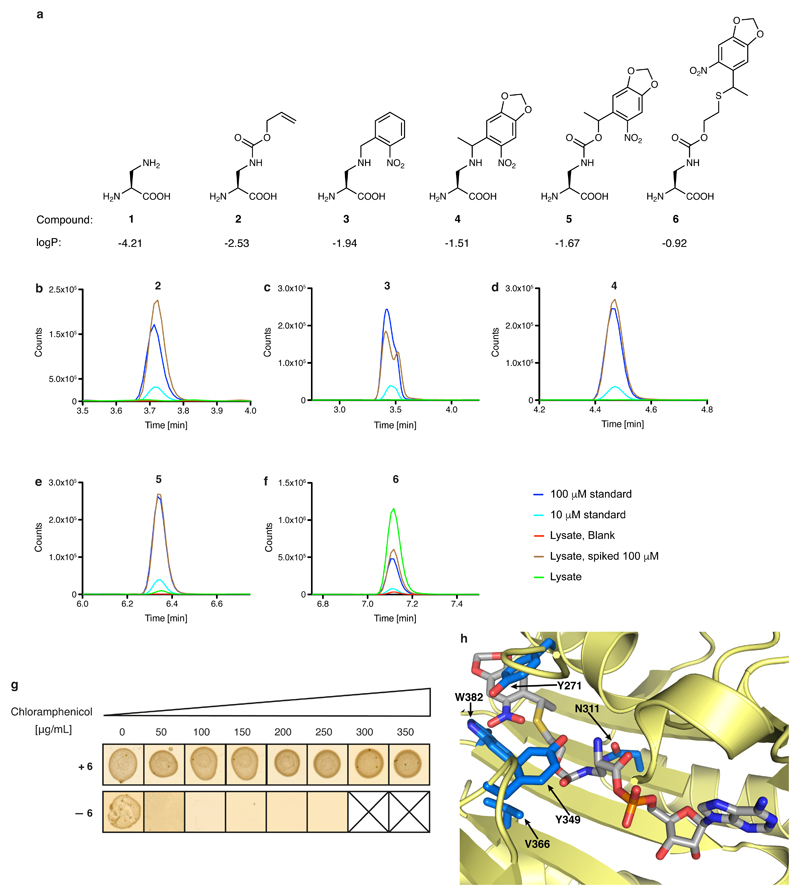

Extended Data Fig. 2. Genetically directing DAP incorporation in recombinant proteins.

a, Structure of DAP and the protected versions investigated herein. 1, 2,3-diaminopropionic acid (DAP); 2, (S)-3-(((allyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-2-aminopropanoic acid; 3, (S)-2-amino-3-((2-nitrobenzyl)amino)propanoic acid; 4, (2S)-2-amino-3-((1-(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)ethyl)amino)propanoic acid; 5, (2S)-2-amino-3-(((1-(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)ethoxy)carbonyl)amino)propanoic acid; 6, (2S)-2-amino-3-(((2-((1-(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)ethyl)thio)ethoxy)carbonyl)amino)propanoic acid. Calculated logP values are indicated (calculated using the Molinspiration molecular property calculation services at www.molinspiration.com/cgi-bin/properties). b–f, Determining the intracellular concentration of compounds 2–6 by an LC–MS assay, performed on extracts. The dark-blue trace represents a 100 µM standard for each compound. The light-blue trace represents a 10 µM standard for each compound. The red trace results from cells grown in the absence of the compound. The brown trace results from cells grown in the absence of the compound, but spiked with the compound to 100 µM. The green trace results from cells grown in the presence of 1 mM compound. The experiments were repeated in two biological replicates with similar results. g, Phenotyping of the DAPRS/tRNACUA pair. Cells containing the DAPRS/tRNACUA pair and cat(112TAG) (encoding a chloramphenicol-resistance gene containing an amber stop codon (TAG) at codon 112) were plated in the presence or absence of 6 on the indicated concentrations of chloramphenicol. The experiment was performed in two biological replicates with similar results. h, The side chain of 6 (grey sticks) was modelled into the active site of PylRS using a co-crystal structure of PylRS and adenylated pyrrolysine (PDB accession number 2ZIM31). PylRS is displayed in pale yellow and amino-acid positions randomized in DAPRSlib are shown in marine blue.

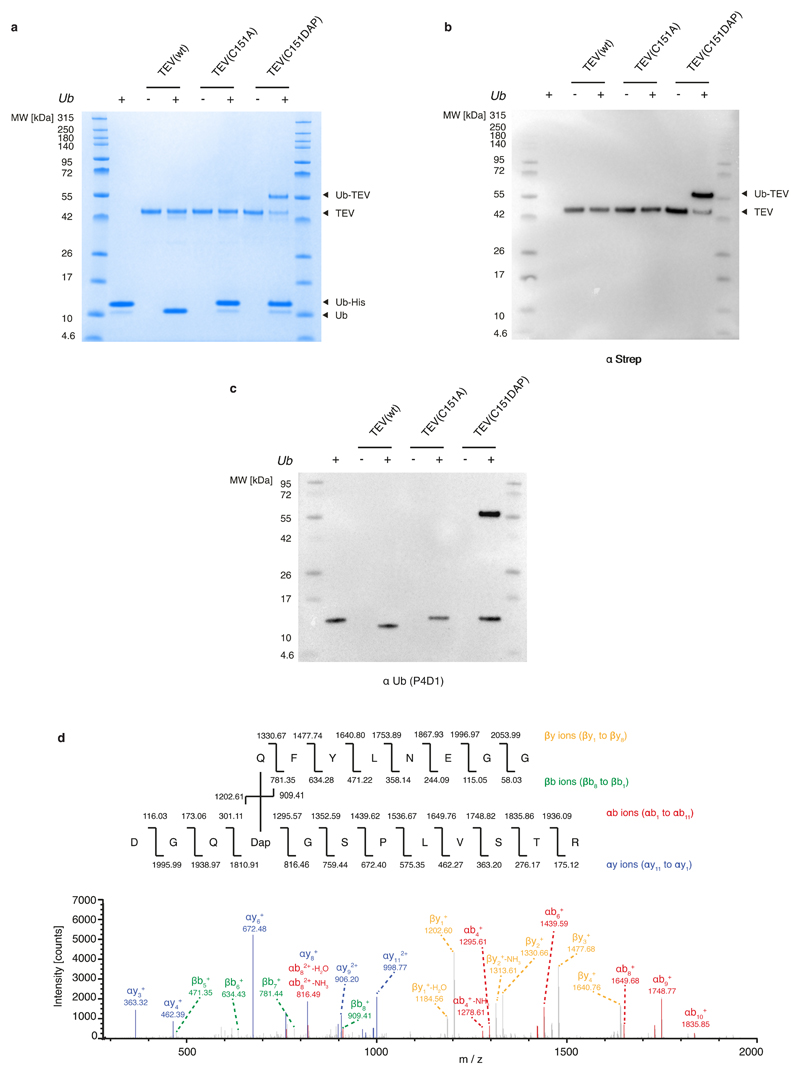

Extended Data Fig. 3. Stably trapping the acyl–enzyme intermediate of a cysteine protease.

a, Different variants of TEV protease (shown at the top) were reacted with Ub–tev–His. The use of TEV(wt) results in cleavage of the TEV cleavage sequence. The use of TEV(C151A) results in minimal cleavage. The presence of DAP in the active site of TEV results in the presence of an extra band in the Coomassie gel, representing the isopeptide-linked TEV(C151DAP)–Ub complex. b, c, Anti-streptavidin (α-strep; b) and anti-Ub (α-Ub antibody P4D1; c) western blots of the reactions confirm the identity of the complex. For panels a–c, the experiment was repeated in two biological replicates with similar results. d, Tandem mass spectrometry following tryptic digest of the TEV(C151DAP)–Ub conjugate confirms amide-bond formation at the expected position. Top, the sequence of the branched peptide subject to fragmentation. Fragmentation of the substrate chain is predicted to lead to a series of y ions (yellow) and a series of b ions (green); the ions from this chain are labelled as ‘β’. Fragmentation of the TEV(C151DAP)-derived chain is predicted to lead to a series of y ions (blue) and a series of b ions (red); the ions from this chain are labelled as ‘α’. Bottom, MS/MS spectra with peak assignments. Ions in the α-chain were assigned by treating DAP and the β-chain as a modification of known mass. Ions in the β-chain were manually assigned. The mass-spectrometry analysis was performed once.

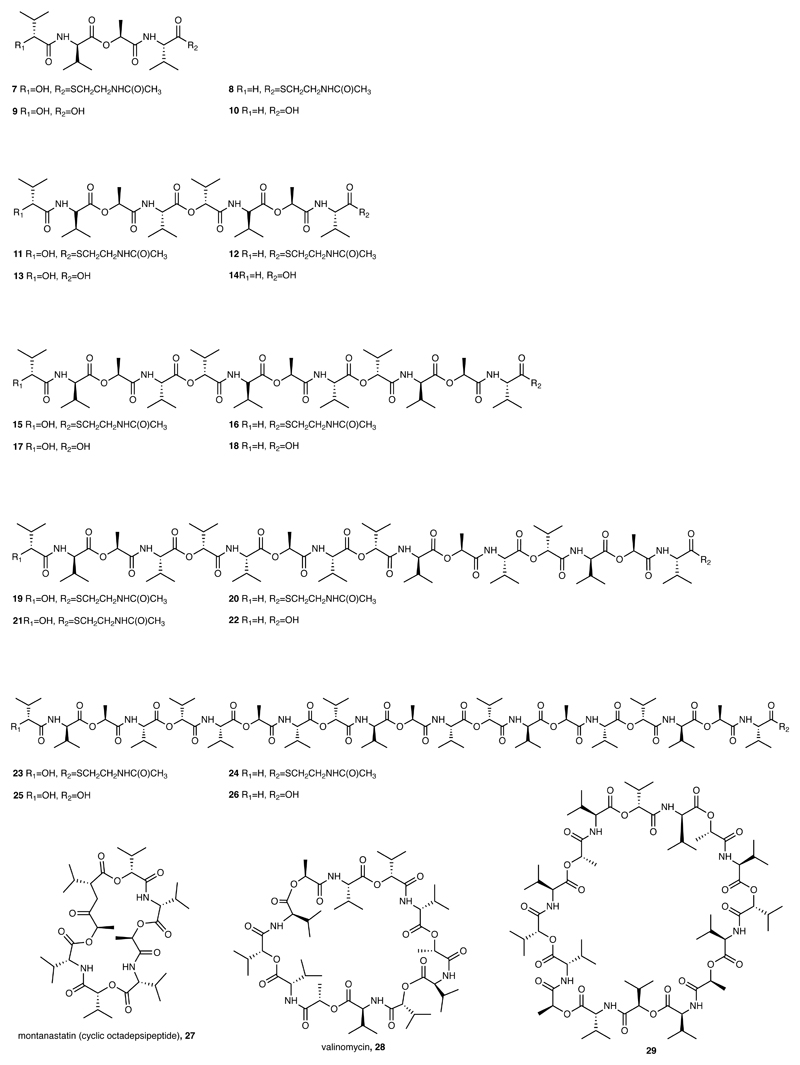

Extended Data Fig. 4. Chemical structures of key Vlm TE substrates described here.

The chemical structures and the numbers used to refer to them are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 5. The mechanism by which by Vlm TE catalyses oligomerization.

Oligomerization could conceivably take place in two ways. a, In the first scenario, ‘forward transfer’, the distal hydroxyl group of the tetradepsipeptidyl–O-TE complex attacks the thioester group in the tetradepsipeptidyl–S-PCP enzyme intermediate, directly forming octadepsipeptidyl–O-TE as a product. b, In the second scenario, ‘reverse transfer’, the distal hydroxyl group of the tetradepsipeptidyl–S-PCP complex attacks the ester group in the tetradepsipeptidyl–O-TE enzyme intermediate, forming octadepsipeptidyl–S-PCP as a product, which would then need to be transferred onto the TE-domain serine (here labelled as ‘re-capture’). c, d, Analogous scenarios involving tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (7) as the substrate instead of tetradepsipeptidyl–S-PCP. e, f, EICs (HR LC–ESI–MS) of a mix of 7 (1.7 mM) and buffer (e), or the products of a reaction between 7 (1.7 mM) and Vlm TEDAP (6.5 μM) (f). g–i, EICs (low-resolution (LR) LC–ESI–MS) of reactions using a higher-volume injection into an ion-trap MS instrument. g, The higher-volume injection of a reaction of 7 (1.7 mM) and Vlm TEwt (6.5 μM) enabled detection of a peak consistent with the 20-mer depsipeptidyl–SNAC (24). h, LC-Ion-trap MS of reaction of 7 (1.7 mM) and Vlm TEDAP (6.5 μM). i, Small amounts of the cyclic 16-mer depsipeptide 29 elute during post-run column clean-up of experiment shown in g. j, EICs (HR LC–ESI–MS) of products of reactions between Vlm TEwt (6.5 μM) and a mix of 7 and deoxy-tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC (8; 1.7 mM of each). TEwt produces the intermediates deoxy-octadepsipeptidyl–SNAC (12), deoxy-dodecadepsipeptidyl–SNAC (16) and deoxy 16-mer depsipeptidyl–SNAC (20), confirming the reaction pathway shown in panel b. See ‘Supplementary Methods for Statistics and Reproducibility’ for accurate mass analysis and deviations from calculated m/z values of each compound. The experiments in panels e–i were repeated independently two times with similar results. Mass-spectrometry analysis of the experiment in panel j was performed once.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Structures of Vlm TEwt and tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP, and top-down LC–ESI–MS of Vlm TEwt.

a, Secondary-structure elements of Vlm TE; the naming is based on the convention for α/β-hydrolase proteins. b, Comparison of two TEwt structures (PDB accession numbers 6ECB and 6ECC). The active-site lid of the first structure (light grey) is nearly completely ordered, while the lid of second structure (dark grey) shows density for Lα3, Lα4 and Lα5 only. In the second structure, Lα3 is rotated 10° towards the active site. c, Deconvoluted mass spectra of TEwt incubated with different substrates. Solid line, buffer control: expected molecular mass 31,028.22 Da; observed 31,028.75 Da. Dashed line, TEwt incubated with tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC: expected 31,028.22 Da (unmodified) and 31,399.44 Da (modified); observed 31026.29 Da. Dotted line, TEwt incubated with valinomycin: expected 31,028.22 Da (unmodified) and 32139.86 Da (modified); observed 31,027.01 Da. Experiments were repeated independently two times with similar results. d, Comparison of near-identical conformations of TEwt (light grey; 6ECB) and tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (tan and dark grey; 6ECD).

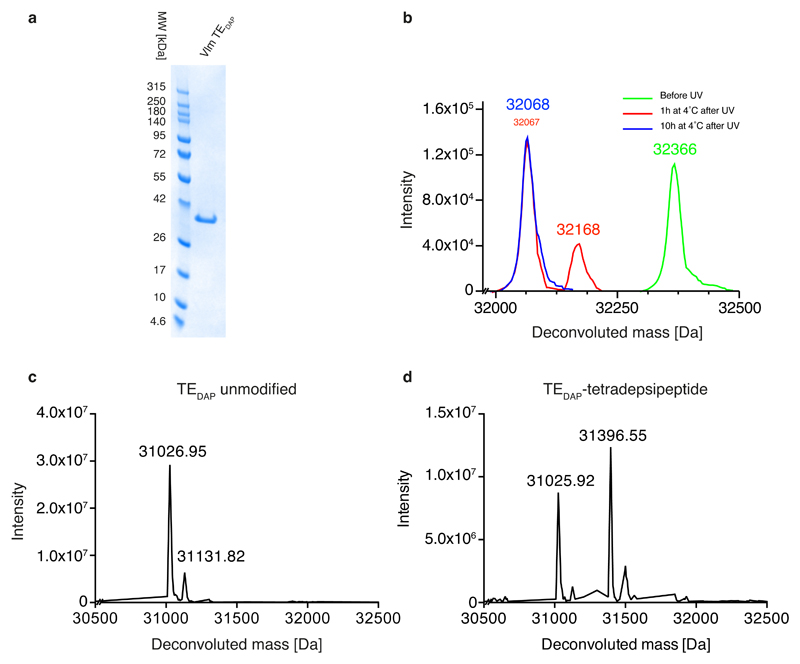

Extended Data Fig. 7. Expression and substrate conjugation to Vlm TE containing DAP at position 2,463.

a, Following expression and purification of Vlm TEDAP, the protein was loaded on an SDS–PAGE gel and Coomassie stained; the experiment was repeated in two biological replicates with similar results. b, The deprotection of 6 in TEDAP–strep was followed by ESI–MS analysis. Green trace, purified TEDAP–strep containing 6 at position 2,463: expected mass 32,364.6 Da, observed 32,365.78 Da. Red trace, TEDAP–strep containing 6 at position 2,463 following illumination to convert 6 to the intermediate: expected 32,171.56 Da, observed 32,168.48 Da; and further incubation (1 h, 4 °C) to convert the intermediate to product: expected 32,067.62 Da, observed 32,068 Da). Blue trace, TEDAP–strep containing 6 at position 2,463 following illumination (to convert 6 to the intermediate) and further incubation (10 h, 4 °C) to convert the intermediate to DAP (1): expected 32,067.62 Da; observed, 32,067.84 Da. The experiment was repeated in two biological replicates with similar results. c, Purified TEDAP after illumination and intermediate fragmentation: expected 31,027.24 Da, observed 31,026.95 Da and 31,131.82 Da. d, TEDAP incubated with tetradepsipeptidyl–SNAC 7: expected 31,027.24 Da (unmodified) and 31,398.69 Da (modified); observed 31,025.92 Da and 31,396.55 Da. The experiments in panels c, d were repeated independently two times with similar results.

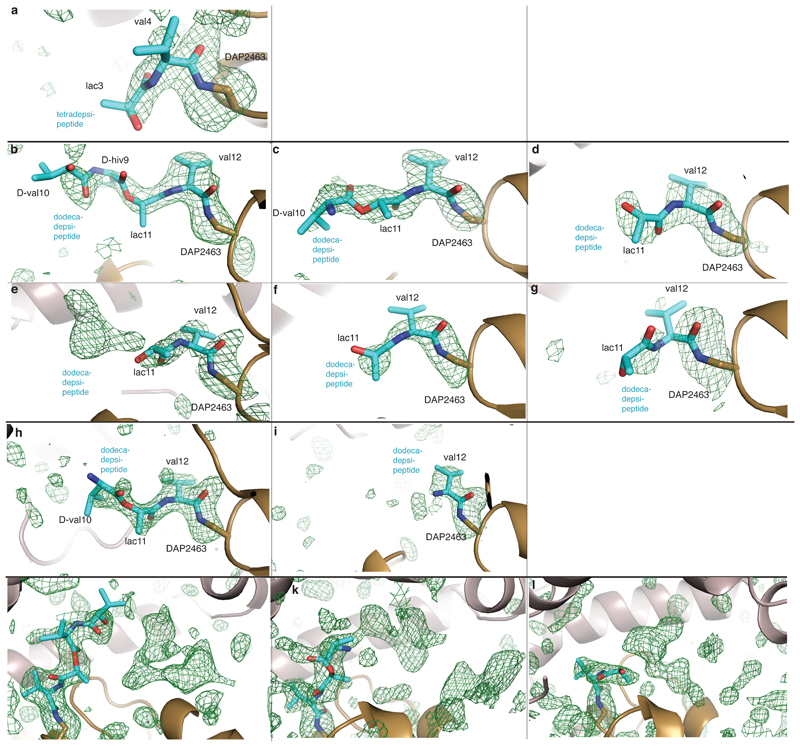

Extended Data Fig. 8. Electron density of the active site of covalent depsipeptidyl–TEDAP complexes.

Unbiased mFo–DFc maps (green mesh, contoured at 2.5σ), calculated before depsipeptide residues were placed in the model. DAP (brown) and depsipeptide residues (cyan) are depicted as sticks. a, Tetradepsipeptidyl–TEDAP (PDB accession number 6ECD). b–g, Dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP P1 space-group structure (6ECF), with crystallographically independent molecules A to F shown in sequential order. h, i: Dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP H3 space group (6ECE), for crystallographically independent molecules A and B. j–l, Electron density of the active site of covalent depsipeptidyl–TEDAP complexes extends beyond modelled depsipeptides. Unbiased mFo–DFc maps (green mesh, contoured at 2.5σ), calculated before depsipeptide residues were placed in the model, for dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP P1 space-group structure, with crystallographically independent molecules A, B and D in sequential order. The observed electron density that extends beyond the modelled depsipeptides (cyan sticks) could accommodate extra depsipeptide residues in different orientations. However, unambiguous modelling into this density could not be achieved.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Modelling of interaction between the PCP domain and TE domain and putative pathway.

a, Superimposition of dodecadepsipeptidyl–TEDAP with the structure of the EntF PCP–TE didomain (PDB accession number 3TEJ) shows the path of the PPE moiety to the active site. b, Hypothetical pathway for oligomerization and cyclization, starting from octadepsipeptidyl–TE. i, The position of Lα1 in the observed apo/tetradepsipeptide conformation promotes an extended peptide conformation. ii, The tetradepsipeptidyl–PCP accepts the octadepsipeptide onto its terminal hydroxyl, perhaps using a dodecadepsipeptide-like lid conformation which could accommodate the roughly 30-Å tetradepsipeptidyl–PPE bound to the PCP domain and guide it towards the active site. iii, The PCP domain presents the thioester for transfer back to serine 2,463. iv, Finally, the lid conformation observed in the dodecadepsipeptide–TEDAP structures could help to curl the dodecadepsipeptide back towards serine 2,463 for cyclization.

Extended Data Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics for the crystal structures presented here.

| TEwt structure 1 (6ECB) |

TEwt structure 2 (6ECC) |

TEDAP bound with a tetradepsipeptide (6ECD) |

TEDAP bound with dodecadepsipeptide, space group H3 (6ECE) |

TEDAP bound with dodecadepsipeptide, space group P1 (6ECF) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | P 4 3 2 | P 4 3 2 | P 4 3 2 | R 3 : H | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 151.4, 151.4, 151.4 | 152.2, 152.2, 152.2 | 152.3, 152.3, 152.3 | 77.6, 77.6, 235.2 | 77.0, 77.1,90.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 91.8, 114.9, 118.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 151.4-1.7 (1.73-1.7) | 152.2-1.8 (1.84-1.8) | 107.7-1.9 (1.94-1.9) | 64.59-2.0 (2.05-2.0) | 78.55-2.5 (2.589-2.5) |

| R sym or R merge | 0.063 (1.059) | 0.08 (1.525) | 0.123 (3.917) | 0.079 (0.845) | 0.071 (0.320) |

| I / sI | 21.83 (1.3) | 19.0 (1.1) | 23.3 (1.0) | 9.8 (1.5) | 4.06 (1.85) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.3 (88.3) | 99.4 (94.2) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 97.58 (97.10) |

| Redundancy | 12.3 (4.5) | 12.7 (6.2) | 37.2 (37.4) | 5.0 (4.9) | 1.7 (1.7) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 75.7-1.7 | 87.87-1.8 | 107.7-1.9 | 44.24-2.0 | 78.55-2.5 |

| No. reflections | 64286 | 55853 | 48056 | 35677 | 53933 |

| R work / R free | 0.1725/0.1874 | 0.1757/0.1898 | 0.1879/0.2143 | 0.2091/0.2426 | 0.1969/0.2489 |

| No. atoms | 2188 | 1917 | 1918 | 3739 | 11761 |

| Protein | 1984 | 1746 | 1807 | 3645 | 11518 |

| Ligand/ion | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 37 |

| Water | 204 | 171 | 106 | 89 | 206 |

| B-factors | 33.45 | 39.71 | 54.47 | 48.06 | 44.16 |

| Protein | 32.52 | 38.92 | 54.39 | 48.09 | 44.13 |

| Ligand/ion | n/a | n/a | 117.62 | 52.13 | 65.2 |

| Water | 42.47 | 47.77 | 52.94 | 46.47 | 41.81 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.31 | 1.69 | 1.65 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

Each data set was collected from a single crystal.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Emsley and G. Murshudov for their help in modelling depsipeptides; A. Wahba, J. Reimer, G. Bridon, K. Heesom and T. Elliott for help with mass spectrometry; M. Tarry and N. Rogerson for editing; C. Alonso for early crystal trials; R. Hay for early discussion on DAP; and S. Zhang help with cloning. We also thank the staff of beamlines CLS 08ID-1 (S. Labiuk, J. Gorin, M. Fodje, K. Janzen, D. Spasyuk and P. Grochulski) and APS 24-ID-C (F. Murphy). This work is supported by grants to J.W.C. from the Medical Research Council, UK (grant numbers MC_U105181009 and MC_UP_A024_1008), to T.M.S. from the Canada Research Chair and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; Discovery Grant 418420) and to C.N.B. from NSERC (Discovery Grant 06167).

Footnotes

Author contributions N.H.-D. and D.P.N. selected the synthetases for 2–6. N.H.-D. characterized the incorporation of 6 and its deprotection to produce DAP, and performed the TEV conjugation. M.M. synthesized 2–6. T.M.S. and D.A.A. designed, and D.A.A. performed, the biochemistry and crystallography with Vlm TEwt. D.A.A. and N.H.-D. performed biochemistry and crystallography with Vlm TEDAP. G.W.H. and M.H.D. synthesized Vlm TE substrates. J.W.C. supervised N.H.-D., D.P.N. and M.M. T.M.S. supervised D.A.A. G.W.H. and M.M. contributed equally. C.N.B. supervised G.W.H. and M.H.D. T.M.S., D.A.A., N.H.-D. and J.W.C. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Data availability

Source data for all figures are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The models and structure factors for the crystal structures are deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 6ECB, 6ECC, 6ECD, 6ECE and 6ECF. Detailed methods, including chemical syntheses, are available in the Supplementary Information.

References

- 1.Holliday GL, Mitchell JBO, Thornton JM. Understanding the functional roles of amino acid residues in enzyme catalysis. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:560–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4501–4524. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long JZ, Cravatt BF. The metabolic serine hydrolases and their functions in mammalian physiology and disease. Chem Rev. 2011;111:6022–6063. doi: 10.1021/cr200075y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto HH, Schirmeister T. Cysteine proteases and their inhibitors. Chem Rev. 1997;97:133–172. doi: 10.1021/cr950025u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swatek KN, Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016;26:399–422. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W, Drueckhammer DG. Understanding the relative acyl-transfer reactivity of oxoesters and thioesters: computational analysis of transition state delocalization effects. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11004–11009. doi: 10.1021/ja010726a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu B, Schofield CJ, Wilmouth RC. Structural analyses on intermediates in serine protease catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24024–24035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scaglione JB, et al. Biochemical and structural characterization of the tautomycetin thioesterase: analysis of a stereoselective polyketide hydrolase. Angew Chem Int Edn. 2010;49:5726–5730. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappadocia L, Lima CD. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation: structures, chemistry, and mechanism. Chem Rev. 2018;118:889–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plechanovová A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature. 2012;489:115–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin JW. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code of cells and animals. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magarvey NA, Ehling-Schulz M, Walsh CT. Characterization of the cereulide NRPS alpha-hydroxy acid specifying modules: activation of alpha-keto acids and chiral reduction on the assembly line. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10698–10699. doi: 10.1021/ja0640187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan Y, et al. Incorporation of 2,3-diaminopropionic acid into linear cationic amphipathic peptides produces pH-sensitive vectors. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1266–1272. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. Rates of uncatalyzed peptide bond hydrolysis in neutral solution and the transition state affinities of proteases. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6105–6109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reimer JM, Haque AS, Tarry MJ, Schmeing TM. Piecing together nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;49:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horsman ME, Hari TPA, Boddy CN. Polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase thioesterase selectivity: logic gate or a victim of fate? Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:183–202. doi: 10.1039/c4np00148f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyer KM, Mahlert C, Marahiel MA. The iterative gramicidin s thioesterase catalyzes peptide ligation and cyclization. Chem Biol. 2007;14:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaitzig J, Li J, Süssmuth RD, Neubauer P. Reconstituted biosynthesis of the nonribosomal macrolactone antibiotic valinomycin in Escherichia coli . ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3:432–438. doi: 10.1021/sb400082j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akey DL, et al. Structural basis for macrolactonization by the pikromycin thioesterase. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:537–542. doi: 10.1038/nchembio824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruner SD, et al. Structural basis for the cyclization of the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin by the thioesterase domain SrfTE. Structure. 2002;10:301–310. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samel SA, Wagner B, Marahiel MA, Essen LO. The thioesterase domain of the fengycin biosynthesis cluster: a structural base for the macrocyclization of a non-ribosomal lipopeptide. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:876–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, et al. Palladium-triggered deprotection chemistry for protein activation in living cells. Nat Chem. 2014;6:352–361. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker AS, Deiters A. Optical control of protein function through unnatural amino acid mutagenesis and other optogenetic approaches. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1398–1407. doi: 10.1021/cb500176x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virdee S, Ye Y, Nguyen DP, Komander D, Chin JW. Engineered diubiquitin synthesis reveals Lys29-isopeptide specificity of an OTU deubiquitinase. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:750–757. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng CC, et al. Characterization of the surfactin synthetase C-terminal thioesterase domain as a cyclic depsipeptide synthase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13350–13359. doi: 10.1021/bi026592a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trauger JW, Kohli RM, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Peptide cyclization catalysed by the thioesterase domain of tyrocidine synthetase. Nature. 2000;407:215–218. doi: 10.1038/35025116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Prediger P, Dias LC, Murphy AC, Leadlay PF. Macrodiolide formation by the thioesterase of a modular polyketide synthase. Angew Chem Int Edn. 2015;54:5232–5235. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frueh DP, et al. Dynamic thiolation-thioesterase structure of a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase. Nature. 2008;454:903–906. doi: 10.1038/nature07162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whicher JR, et al. Structure and function of the RedJ protein, a thioesterase from the prodiginine biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces coelicolor . J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22558–22569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekici OD, Paetzel M, Dalbey RE. Unconventional serine proteases: variations on the catalytic Ser/His/Asp triad configuration. Protein Sci. 2008;17:2023–2037. doi: 10.1110/ps.035436.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavran JM, et al. Structure of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase, an archaeal enzyme for genetic code innovation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11268–11273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704769104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for all figures are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The models and structure factors for the crystal structures are deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 6ECB, 6ECC, 6ECD, 6ECE and 6ECF. Detailed methods, including chemical syntheses, are available in the Supplementary Information.