Abstract

Importance:

Mortality is significantly increased after hip fracture, with 20–30% of hip fracture patients dying within one year. Causes of the excess mortality observed in hip fracture patients are not well understood. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) sustained during hip fracture may be a cause of excess mortality in this population.

Objective:

To estimate the prevalence of diagnosed TBI among hospitalized hip fracture patients and examine its association with all-cause mortality.

Design:

Nested cohort study

Setting:

National sample of Medicare beneficiaries 2006–2010

Participants:

Beneficiaries aged ≥65 years and hospitalized with hip fracture

Exposure:

TBI at the time of hip fracture was defined using ICD-9-CM codes

Main Outcome:

All-cause mortality during follow-up

Results:

Prevalence of TBI among hip fracture patients was 2.7% The absolute risk of mortality attributable to TBI among hip fracture patients was 15/100 person-years. TBI was significantly associated with increased risk of death in multivariable analysis (HR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.14–1.35).

Conclusions and Relevance:

TBI was associated with increased risk of mortality among hip fracture patients. Practitioners should consider evaluating for presence of TBI in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Hip fracture, Traumatic brain injury, mortality, Medicare

Introduction

Hip fracture is one of the most serious fall-related injuries in the United States (US), resulting in more than 265,000 hospitalizations each year among adults 65 years and older.1 Mortality is significantly increased after hip fracture, with 20–30% of hip fracture patients dying within one year.2,3 Risk ratios for mortality range from 10.4–11.6 for those aged 60 to 3.1–3.4 for patients aged 80 in the first year following hip fracture, and risk remains elevated even at five years post-fracture.4 Causes of the excess mortality observed in hip fracture patients are not well understood, although higher burden of comorbid conditions is thought to play a role.2,4,5

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is also caused primarily by falls among older adults and is associated with cognitive impairment, disability and mortality.6–13 TBI resulted in over 600,000 emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths among older adults in the US in 2013.11 The majority (>70%) of TBIs are mild and can even occur without direct head impact due to acceleration/deceleration motion.11 Older adults may be less likely to receive treatment for TBI and are less likely to receive an accurate diagnosis.14–16 This is particularly important among older adults with hip fracture, where the acute pain from the fracture may mask symptoms of TBI. Thus, TBI sustained during the fall that resulted in hip fracture could contribute to poorer outcomes, including cognitive impairment and mortality.13 While this seems intuitive, no studies have specifically assessed TBI in hip fracture patients.

Using Medicare administrative claims data, our objective was to estimate the prevalence of diagnosed TBI among hospitalized hip fracture patients and examine its association with all-cause mortality. We hypothesized that TBI would be associated with increased risk of mortality.

Methods

Data Source and Study Design

We conducted a nested cohort study of hip fracture patients using administrative claims data obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Condition Data Warehouse (CCW).17 Data for this study were originally obtained to conduct a study of hospitalized TBI patients and have been previously described.18 Briefly, all Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years with continuous Parts A, B, and D with no Part C coverage hospitalized with TBI (identified using ICD-9-CM codes 800.xx, 801.xx, 803.xx, 804.xx, 850.xx- 854.1x, 950.1–950.3, 959.01) in any position on the claim between 2006–2010 were identified. Following this step, a random sample of hospitalized beneficiaries with any other ICD-9-CM codes for injuries (802.0x-802.9x, 805.0x-819.xx, 821.xx-848.xx, 860.xx-878.xx, 879.0x-879.7x, 880.xx-900.xx, 901.xx, 902.0x, 902.0x-902.5x, 902.8x, 902.9, 903.xx- 909.2, 909.4, 909.9, 910.0–925.xx, 926xx, 927.xx-950.0, 950.9, 951.xx-958xx, 959.09–959.9, 980.xx-989.xx, 995.5–995.59, 995.80–995.85) and meeting the same continuous enrollment criteria was selected until the number of individuals in the cohort was equal to 250,000. Thus, the final dataset contained all beneficiaries hospitalized with TBI in any position on an inpatient claim and a random sample of individuals with other injuries.

From this sample we identified all beneficiaries with a primary diagnosis of hip fracture (ICD-9-CM 820.xx). We required continuous enrollment for at least 6 months pre-injury to capture baseline comorbidities. We identified individuals with TBI in a secondary diagnosis position and excluded individuals with any other injuries. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland.

Outcome and covariates

The outcome of this study was all-cause mortality. We obtained date of death from the beneficiary annual summary file and used it to calculate time to death from injury admission. From the annual file we also obtained age, sex, race, and original reason for Medicare entitlement (OREC): age, disability, or end stage renal disease. CMS’s CCW contains dates of first diagnosis and annual flags for 21 chronic conditions that are based on ICD-9-CM codes using published algorithms.17 A patient was considered to have a chronic condition if the first date of diagnosis occurred prior to hospital admission for hip fracture.

Statistical analysis

We compared characteristics of hip fracture patients with and without TBI using Chi-square Goodness of Fit and Student’s t-tests. We calculated annual and cumulative mortality rates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) following hip fracture by TBI status. To estimate the association between TBI and mortality, we conducted a time-to-event analysis with death as the event of interest. Beneficiaries were censored at the end of follow-up if no event was observed. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI of death as a function of TBI. Potential confounders identified in bivariate analysis (p<0.05) were added to the final regression model. Based on prior work suggesting sex differences in outcomes following TBI, we examined sex as a possible effect modifier on the multiplicative scale using stratified analysis.19–21

Results

We identified 38,230 Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with hip fracture and meeting inclusion criteria, of whom 1,043 (2.7%) had TBI (Table 1). Women formed the majority (77.9%) and this proportion did not differ significantly by TBI status. The population was primarily white (91.5%). Compared to those without TBI, individuals with TBI had significantly higher proportion of anemia (76.2% vs 73.5%, p= 0.04), depression (50.9% vs 46.0%, p= 0.002), Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (50.1% vs 43.1%, p<0.001), and history of stroke (35.6% vs 31.0%, p=0.002). Among hip fracture patients, those with TBI were more likely to die during follow-up (53.4% vs 45.8%, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Hospitalized with Hip Fracture 2006-2010 by Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Status, n = 38,230

| No TBI, n = 37,187 |

TBI, n=1,043 |

p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 83.7 (7.6) | 84.4 (7.4) | 0.01 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 28,991 (78.0) | 810 (77.7) | 0.82 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 34,050 (91.7) | 945 (90.7) | 0.25 |

| Calendar year, n (%) | |||

| 2007 | 2,493 (6.7) | 78 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| 2008 | 4,299 (11.6) | 153 (14.7) | |

| 2009 | 5,591 (15.0) | 196 (18.8) | |

| 2010 | 24,804 (66.7) | 616 (59.1) | |

| Comorbid Illness, n (%) | |||

| ADRD2 | 16,019 (43.1) | 523 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 27,319 (73.5) | 795 (76.2) | 0.04 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9,510 (25.6) | 327 (31.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 10,395 (28.0) | 319 (30.6) | 0.06 |

| COPD3 | 15,041 (40.5) | 429 (41.1) | 0.66 |

| Coagulation disorder | 2,624 (7.1) | 99 (9.5) | 0.002 |

| Depression | 17,117 (46.0) | 531 (50.9) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes | 13,910 (37.4) | 416 (39.9) | 0.10 |

| Heart Failure | 18,724 (50.4) | 528 (50.6) | 0.87 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 25,511 (68.6) | 721 (69.1) | 0.72 |

| Hypertension | 33,399 (89.8) | 966 (92.6) | 0.003 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 24,246 (65.2) | 720 (69.0) | 0.01 |

| Stroke | 11,509 (31.0) | 371 (35.6) | 0.002 |

| Death, n (%) | 17,048 (45.8) | 557 (53.4) | <0.001 |

| Time to death, mean (SD) | 388.2 (385.7) | 300.3 (323.0) | <0.001 |

Student’s T-test and Chi-Square Goodness of Fit test;

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias;

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

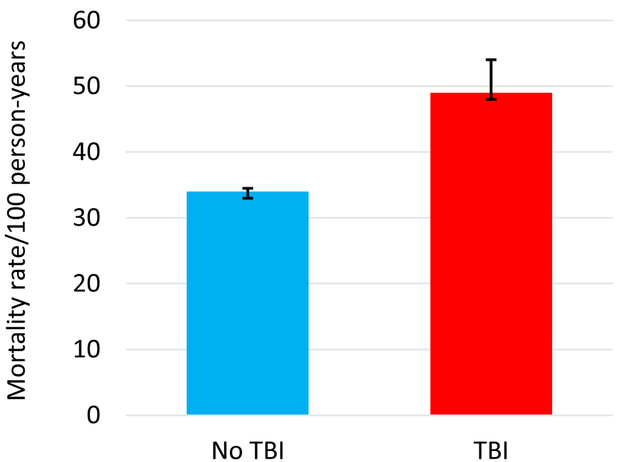

The mortality rate in the year following hip fracture was 49/100 person-years (95% CI 44, 54) for beneficiaries with TBI compared to 34/100 person-years (95% CI 33, 34) in beneficiaries without TBI (Figure). The overall proportion of deaths in the first year after hip fracture was 33%. The cumulative mortality rate over up to 5 years follow-up was 36/100 person-years (95% CI 33, 39) for beneficiaries with TBI compared to 26/100 person-years (95% CI 25, 26) in those without TBI. The risk of mortality attributable to TBI among hip fracture patients was 15/100 person-years.

Figure.

Mortality Rate/100 Person-Years among Hip Fracture Patients with and without Traumatic Brain Injury

Among hip fracture patients, TBI was associated with significantly increased risk of death in unadjusted analysis (HR 1.36; 95% CI: 1.25–1.48)(Table 2). After adjusting for age, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, coagulation disorder, depression, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke, TBI remained associated with increased risk of death (HR 1.24; 95% CI: 1.14–1.35). Sex did not modify the association between TBI and mortality after hip fracture.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% confidence interval) of Mortality Associated with Traumatic Brain Injury among Hip Fracture Patients (n = 38,230)

| HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| TBI, unadjusted | 1.36 (1.25, 1.48) |

| TBI | 1.24 (1.14, 1.35) |

| Age, years | 1.04 (1.04, 1.04) |

| Comorbid illness | |

| Alzheimer's dementia | 1.61 (1.56, 1.66) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.28 (1.24, 1.33) |

| Coagulation disorder | 1.57 (1.49, 1.66) |

| Depression | 1.08 (1.05, 1.12) |

| Hypertension | 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1.19 (1.15, 1.23) |

| Stroke | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) |

Discussion

In this national study of fee for service Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with hip fracture, prevalence of diagnosed TBI was low (2.7%) but associated with a 24% increase in the risk of death after adjustment for covariates. TBI resulted in an additional 15 deaths/100 person-years in the first year following hip fracture.

One-year mortality in this study is consistent with that reported by Roche and colleagues (2005) in a study of hip fracture patients (with and without diagnosed TBI) performed in England 1999–2003, but slightly lower than that reported by Johnell (2004) and Panula (2011).4,22,23 The older age of our sample (83.8 years) compared to that in the Johnell (80.1) and Panula (81.8) studies, as well as baseline differences in the studied populations may have contributed in higher 1-year mortality in our study.4,23

Prevalence of TBI in this study was low (2.7%). Given the same mechanism of injury (falls) as hip fracture and known barriers to diagnosis among older adults, this suggests that TBI is likely underdiagnosed among hip fracture patients.11,14,15 While there are no existing data on the true prevalence of TBI among hip fracture patients, it is important to undertake studies to ascertain this. Even with this conservative estimate of TBI prevalence, it significantly increased risk of mortality and may be associated with other poor outcomes.

Among Medicare beneficiaries with hip fracture, those with TBI were older and had higher prevalence of certain comorbidities, particularly Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. While we lacked information on nursing home residence in this study, high prevalence of dementia points to the possibility that many of these individuals may be living in long-term care facilities. If so, caregivers in these facilities should be aware of the potential for head injury in those who have hip fractures.

Results from this study should be considered in light of several limitations. First, the mechanism of injury for the hip fractures in this study was unknown. Most hip fractures are caused by falls, but in this study some could have been caused by traumatic events like car crashes that are more likely to increase risk of TBI. Second, we have no information on the severity, type, or location of the TBI. The low prevalence of TBI in this study suggests that TBIs that were diagnosed were more severe, which would have increased risk of mortality compared to milder TBI. Last, we lacked information on delirium and cognitive impairment, possible consequences of TBI and known risk factors for mortality, including fracture location, among hip fracture patients.24–27

In conclusion, TBI was associated with increased risk of mortality among hip fracture patients. Practitioners should consider evaluating for presence of TBI in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Dr. Albrecht was supported by Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research grant K01HS024560. Dr. Gruber-Baldini was supported by National Institute of Aging grant R21AG054143. Dr. Magaziner was supported by National Institute of Aging grant P30 AG028747.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Albrecht is supported by Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research grant 1K01HS024560. Dr. Magaziner is supported by National Institute of Aging grants R37 AG009901 and P30 AG028747.

Footnotes

Sponsor’s Role

The sponsor played no role in study design, implementation, or interpretation of results.

References

- 1.HCUPnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2005;16 Suppl 2:S3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE, Yeates D. Mortality after admission to hospital with fractured neck of femur: database study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;325(7369):868–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2004;15(1):38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. Jama. 2009;302(14):1573–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner RC, Dams-O’Connor K, Morrissey MR, Manley G. Geriatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology, Outcomes, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Directions. Journal of neurotrauma. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosenthal AC, Lavery RF, Addis M, et al. Isolated traumatic brain injury: age is an independent predictor of mortality and early outcome. The Journal of trauma. 2002;52(5):907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosenthal AC, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, et al. The effect of age on functional outcome in mild traumatic brain injury: 6-month report of a prospective multicenter trial. The Journal of trauma. 2004;56(5):1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papa L, Mendes ME, Braga CF. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury among the Geriatric Population. Current translational geriatrics and experimental gerontology reports. 2012;1(3):135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selassie AW, Zaloshnja E, Langlois JA, Miller T, Jones P, Steiner C. Incidence of long-term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States, 2003. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2008;23(2):123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L. Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths - United States, 2007 and 2013. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC : 2002). 2017;66(9):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Utomo WK, Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Cameron PA. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and 6-month functional outcomes in older adults after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2009;40(9):973–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC CfDCaP. Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control;2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrecht JS, Hirshon JM, McCunn M, et al. Increased Rates of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Among Older Adults in US Emergency Departments, 2009–2010. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2016;31(5):E1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setnik L, Bazarian JJ. The characteristics of patients who do not seek medical treatment for traumatic brain injury. Brain injury. 2007;21(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Yang Y, Xia Y, et al. Aging of cerebral white matter. Ageing research reviews. 2017;34:64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: the role of age and severity. JAMA neurology. 2014;71(12):1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albrecht JS, Liu X, Baumgarten M, et al. Benefits and risks of anticoagulation resumption following traumatic brain injury. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(8):1244–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albrecht JS, Kiptanui Z, Tsang Y, et al. Depression among older adults after traumatic brain injury: a national analysis. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):607–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry C, Ley EJ, Tillou A, Cryer G, Margulies DR, Salim A. The effect of gender on patients with moderate to severe head injuries. The Journal of trauma. 2009;67(5):950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brazinova A, Mauritz W, Leitgeb J, et al. Outcomes of patients with severe traumatic brain injury who have Glasgow Coma Scale scores of 3 or 4 and are over 65 years old. Journal of neurotrauma. 2010;27(9):1549–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2005;331(7529):1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panula J, Pihlajamaki H, Mattila VM, et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2011;12:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruber-Baldini AL, Hosseini M, Orwig D, et al. Cognitive Differences between Men and Women who Fracture their Hip and Impact on Six-Month Survival. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017;65(3):e64–e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Givens JL, Sanft TB, Marcantonio ER. Functional recovery after hip fracture: the combined effects of depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and delirium. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(6):1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggiero C, Bonamassa L, Pelini L, et al. Early post-surgical cognitive dysfunction is a risk factor for mortality among hip fracture hospitalized older persons. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2017;28(2):667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuman MD, Silber JH, Magaziner JS, Passarella MA, Mehta S, Werner RM. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(8):1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]