Abstract

Objectives:

“Assurance behaviors” in medical practice involve providing additional services of marginal or no medical value to avoid adverse outcomes, deter patients from filing malpractice claims, or ensure that legal standards of care were met. The extent to which concerns about medical malpractice influence assurance behaviors of pathologists interpreting breast specimens is unknown.

Methods:

Breast pathologists (n = 252) enrolled in a nationwide study completed an online survey of attitudes regarding malpractice and perceived alterations in interpretive behavior due to concerns of malpractice. Associations between pathologist characteristics and the impact of malpractice concerns on personal and colleagues’ assurance behaviors were determined by χ2 and logistic regression analysis.

Results:

Most participants reported using one or more assurance behaviors due to concerns about medical malpractice for both their personal (88%) and colleagues’ (88%) practices, including ordering additional stains, recommending additional surgical sampling, obtaining second reviews, or choosing the more severe diagnosis for borderline cases. Nervousness over breast pathology was positively associated with assurance behavior and remained statistically significant in a multivariable logistic regression model (odds ratio, 2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.0–6.1; P = .043).

Conclusions:

Practicing US breast pathologists report exercising defensive medicine by using assurance behaviors due to malpractice concerns.

Keywords: Medical malpractice, Defensive medicine, Assurance behaviors, Breast pathology, Breast

Delayed diagnosis of breast cancer is a leading cause of malpractice suits filed in the United States,1,2 and malpractice litigation is least likely to be dismissed and most likely to go to trial when a pathologist is involved compared with malpractice litigation involving other medical specialties.3 A recent analysis of malpractice claims from a large professional liability insurer indicated that the average indemnity payment for pathologists was higher than high-risk specialties such as neurosurgery.4 Although pathology claim frequency is low, pathology claim severity is high, particularly with claims involving failure to diagnose cancer, resulting in delayed diagnosis or inappropriate treatment.5

Defensive medicine is defined as a deviation from standard medical practice induced primarily by a threat of liability.6 More specifically, physicians order additional services with marginal or no medical value to avoid adverse patient outcomes, deter patients from filing malpractice claims, or ensure that legal standards of care are met.7,8 Such behaviors are known as assurance behaviors. A 2009 nationwide survey of physicians on health care reform found that an overwhelming majority (91%) believed physicians order more tests and procedures than patients need to protect themselves from malpractice suits.9 A 2010 survey of medical students and residents also discovered that most medical students (92%) and residents (96%) sometimes or often encountered at least one assurance practice, with 53% reporting that their attending physicians taught them to take liability into account when making clinical decisions.10 A recent 2014 survey of third-year medical students revealed that 32% of faculty members are teaching defensive medicine and that career satisfaction was negatively influenced by malpractice concerns and lawsuits.11

Fear of medical malpractice lawsuits is common among physicians,3 and practicing defensive medicine to avoid litigation is widespread, particularly in high-claim frequency specialties such as emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and obstetrics/gynecology.8 The experience and attitudes of breast pathologists, practicing in a field with high claim severity, have not been addressed. We hypothesized that pathologists interpreting breast specimens, as practitioners in a high-risk field for medical malpractice claim severity, would perceive that an array of assurance behaviors are taken to protect from medical malpractice. Our aim was to examine associations between defensive medicine and participant characteristics, including demographics, training and experience, and perceptions about interpreting breast specimens in a nationwide survey of practicing pathologists.

Materials and Methods

We recruited breast pathologists (n = 252) from eight US states to participate in a study that included completing an online survey. The Breast Pathology Study (B-Path) and its methods are described in detail elsewhere.12–14 Briefly, between November 2011 and February 2013, study participants were recruited via email, postal mail, and telephone follow-up. Each study participant completed the online survey, which was designed to assess experience and expertise with breast pathology, in addition to attitudes regarding second opinions, digital pathology, medical malpractice experience, and perceptions of how medical malpractice influences their interpretive behavior. All study activities are Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and were approved by the institutional review boards at Dartmouth College, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Providence Health & Services of Oregon, the University of Vermont, and the University of Washington School of Medicine.

An online survey was developed by our research team after consulting with breast pathologists on important topics in the field. The survey was field tested with highly experienced and nationally recognized breast pathologists who were not in the pool of invitees for the study cohort, and it was developed and pilot tested using cognitive interviewing techniques.15 The survey was designed to take approximately 15 minutes to complete and included questions on general professional information (demographics and clinical practice), second opinion (attitudes and perceived practice), digitized whole-slide imaging (attitudes and perceived practice), and medical malpractice (previous lawsuits and perceived impact on interpretive behaviors). More specifically, participants were asked, “Have you ever been named in a medical malpractice suit (including any suit filed and either dropped, settled out of court or gone to trial)?” to which responders endorsed “yes, suit(s) related to breast pathology cases,” “yes, suit(s) related to other pathology or other medical cases,” or “no.” In addition, several survey questions were designed to capture pathologists’ attitudes related to medical malpractice and their perceptions of the impact of medical malpractice on the field, specifically with respect to assurance behaviors.16

The pathologists’ survey included four assurance behavior questions, each following the stem “Have medical malpractice concerns affected your own practice with breast cases in the following ways?”: “I order additional immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests,” “I recommend additional surgical sampling,” “I request additional reviews (second opinion),” and “When a case is borderline between DCIS [ductal carcinoma in situ] and ADH [atypical ductal hyperplasia], I generally choose the more severe diagnosis of DCIS.” A dichotomous variable was created to aggregate all types of assurance behaviors so that agreement to one or more assurance behaviors captured a respondent’s perceived use of an assurance behavior in practice. If a participant answered in the affirmative for any of the questions, it was considered a use of one or more assurance behaviors in practice.

In addition, the survey included four similar assurance behavior questions regarding their perception of their peers’ use of an assurance behavior in practice, each following the stem “Have medical malpractice concerns affected your peers’ practice with breast cases in the following ways?”: “My peers order additional immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests,” “My peers recommend additional surgical sampling,” “My peers request additional reviews (second opinion),” and “When a case is borderline between DCIS and ADH, my peers generally choose the more severe diagnosis of DCIS.” A dichotomous variable was created to aggregate all types of assurance behaviors so that agreement to one or more assurance behavior captured a respondent’s perception of their peers’ use of an assurance behavior in practice.

Survey responses were compared across the dichotomized groups and summarized as frequencies and percentages. We performed χ2 tests to assess differences in demographics, training and experience, and perceptions about breast interpretation between pathologists perceiving use of any assurance behavior and those who do not engage in assurance behaviors. Multivariable modeling using logistic regression analysis examined covariate associations where one or more assurance behaviors (yes/no) were included as the dependent variables. Independent variables were selected based on background knowledge of the investigators and using associations in the descriptive summaries as a guide. Covariates included in the fully adjusted model were age group, previously sued, sex, number of breast cases per week, whether or not interpreting breast pathology made participants more nervous than other types of pathology, and whether participants thought second opinion protected against medical malpractice. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

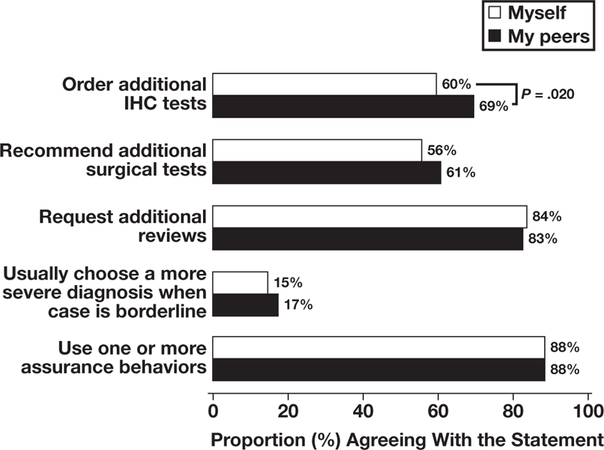

Of the 389 breast pathologists who received an invitation to the study and were eligible for participation, 252 (65%) enrolled and completed the online survey. Eighty-eight percent of participants reported engaging in at least one assurance behavior because of their litigation concerns ❚Figure 1❚. Overall, participants ordered additional immunohistochemistry tests (60%), recommended additional surgical sampling (56%), requested additional reviews (84%), and chose more severe diagnoses in borderline cases (15%). Eighty-eight percent also believed their peers engaged in at least one assurance behavior, including ordering additional immunohistochemistry tests (69%), recommending additional surgical sampling (61%), requesting additional reviews (83%), and choosing more severe diagnoses in a borderline case (17%). Differences between participants and their peers were statistically significant only for ordering more immunohistochemistry tests (60% of participants vs 69% of peers, P = .020). Assurance behaviors did not differ based on whether participants had prior medical malpractice experiences.

❚Figure 1❚.

Breast pathologists’ perceptions of the impact of medical malpractice on self and peer assurance behaviors. IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Most pathologists’ characteristics relating to demographics, training and experience, and perceptions about breast interpretation did not differ by whether they used assurance behaviors ❚Table 1❚. Female pathologists were more likely to use assurance behaviors than males (93.5% vs 85.5%, P = .054), although this P value only approached significance. In addition, pathologists using at least one assurance behavior were more likely to believe that second opinion protects pathologists from medical malpractice (90.3% vs 78.0%, P = .025) and that breast pathology makes them more nervous than other types of pathology (92.7% vs 85.3%, P = .070, approaching significance) compared with pathologists not reporting these beliefs.

❚Table 1❚.

Pathologists’ Characteristics and Perceptions About Breast Interpretation

| Characteristic | Total, No. (%) | Does Not Use Assurance Behaviors in Practice (n = 29), No. (%) |

Uses One or More Assurance Behaviors in Practice (n = 223), No. (%) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 252 (100) | 29 (11.5) | 223 (88.5) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at survey, y | .14 | |||

| 30–49 | 119 (47) | 10 (8.4) | 109 (91.6) | |

| 50+ | 133 (53) | 19 (14.3) | 114 (85.7) | |

| Sex | .054 | |||

| Male | 159 (63) | 23 (14.5) | 136 (85.5) | |

| Female | 93 (37) | 6 (6.5) | 87 (93.5) | |

| Region of clinical practiceb | .21 | |||

| West | 155 (62) | 18 (11.6) | 137 (88.4) | |

| Midwest | 42 (17) | 2 (4.8) | 40 (95.2) | |

| Northeast | 55 (22) | 9 (16.4) | 46 (83.6) | |

| Training and experience | ||||

| Facility size | .12 | |||

| <10 Pathologists | 158 (63) | 22 (13.9) | 136 (86.1) | |

| ≥10 Pathologists | 94 (37) | 7 (7.4) | 87 (92.6) | |

| Fellowship training in surgical or breast pathology | .26 | |||

| No | 129 (51) | 12 (9.3) | 117 (90.7) | |

| Yesc | 123 (49) | 17 (13.8) | 106 (86.2) | |

| Affiliation with academic medical center | .36 | |||

| No | 183 (73) | 19 (10.4) | 164 (89.6) | |

| Yes | 69 (27) | 10 (14.5) | 59 (85.5) | |

| Do your colleagues consider you an expert in breast pathology? | .62 | |||

| No | 200 (79) | 22 (11.0) | 178 (89.0) | |

| Yes | 52 (21) | 7 (13.5) | 45 (86.5) | |

| Clinical practice and experience | ||||

| Previous lawsuit | .79 | |||

| No | 186 (74) | 22 (11.8) | 164 (88.2) | |

| Yes | 66 (26) | 7 (10.6) | 59 (89.4) | |

| Breast pathology experience, y | .47 | |||

| <10 | 90 (36) | 8 (8.9) | 82 (91.1) | |

| 10–19 | 89 (35) | 10 (11.2) | 79 (88.8) | |

| ≥20 | 73 (29) | 11 (15.1) | 62 (84.9) | |

| Breast specimen caseload, % | .83 | |||

| <10 | 126 (50) | 13 (10.3) | 113 (89.7) | |

| 10–24 | 104 (41) | 13 (12.5) | 91 (87.5) | |

| 25–75+ | 22 (9) | 3 (13.6) | 19 (86.4) | |

| No. of breast cases (per week) | .10 | |||

| <10 | 166 (66) | 23 (13.9) | 143 (86.1) | |

| 10+ | 86 (34) | 6 (7.0) | 80 (93.0) | |

| Perceptions about breast interpretation | ||||

| How challenging do you find breast cases to interpret? | .73 | |||

| Very easy to easy (1, 2, 3) | 114 (45) | 14 (12.3) | 100 (87.7) | |

| Challenging to very challenging (4, 5, 6) | 138 (55) | 15 (10.9) | 123 (89.1) | |

| How confident are you in your assessments of breast cases? | 1.00 | |||

| Very confident to confident (1, 2, 3) | 233 (92) | 27 (11.6) | 206 (88.4) | |

| Low confidence to not at all confident (4, 5, 6) | 19 (8) | 2 (10.5) | 17 (89.5) | |

| Interpreting breast pathology is enjoyable | .28 | |||

| No | 44 (17) | 3 (6.8) | 41 (93.2) | |

| Yes | 208 (83) | 26 (12.5) | 182 (87.5) | |

| Interpreting breast pathology makes me more nervous than other types of pathology | .070 | |||

| No | 143 (57) | 21 (14.7) | 122 (85.3) | |

| Yes | 109 (43) | 8 (7.3) | 101 (92.7) | |

| Digital slides increase pathologists’ exposure to medical malpractice | .38 | |||

| No | 146 (58) | 19 (13.0) | 127 (87.0) | |

| Yes | 106 (42) | 10 (9.4) | 96 (90.6) | |

| Second opinion protects me from medical malpracticed | .025 | |||

| No | 41 (16) | 9 (22.0) | 32 (78.0) | |

| Yes | 207 (82) | 20 (9.7) | 187 (90.3) |

P value comparing use or no use of one or more assurance behaviors by characteristic, χ2 test.

US census region; some states were not included in the sample.

Of those reporting fellowship training, six responders were trained in breast pathology fellowships.

Those who replied not applicable (N/A) in the original scale were set to missing. Excludes four participants who did not respond to the survey question.

We examined use of assurance behaviors in association with six covariates in a multivariable logistic regression model: personal history of a previous lawsuit, age, sex, number of cases interpreted per week, nervousness about breast pathology, and the belief that second opinion protects pathologists from medical malpractice ❚Table 2❚. Participants who expressed nervousness about breast pathology were 2.5 times more likely to use any assurance behavior compared with participants who did not (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0–6.1; P = .043). None of the other covariate associations was statistically significant.

❚Table 2❚.

Likelihood of Use of Assurance Behaviors Based on Pathologists’ Characteristics in a Multivariable Logistic Regression Model

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Not previously sued | 0.9 (0.3–2.3) | .79 |

| Age 30–49 y | 1.6 (0.7–3.7) | .31 |

| Female sex | 2.1 (0.8–5.6) | .13 |

| ≥10 breast cases interpreted on average per week | 2.3 (0.9–6.3) | .087 |

| Breast pathology makes me more nervous than other types of pathology | 2.5 (1.0–6.1) | .043 |

| Practice requiring me to obtain a second opinion protects from malpractice suits | 2.3 (0.9–5.8) | .066 |

Discussion

Eighty-eight percent of breast pathologists responding to our survey reported that they and their colleagues engage in assurance behaviors due to concerns about medical malpractice resulting in additional tests and procedures. These results are similar to nationwide surveys reporting that 91% to 92% of physicians use assurance behaviors in their medical practices.8,9 In our study, rates were similar regardless of whether pathologists have been personally sued, although pathologists who expressed nervousness over breast pathology were 2.5 times more likely to engage in at least one assurance behavior compared with those who did not express nervousness. Nearly half the respondents (46%; 115/252) in this study also participated in a related study that demonstrated high diagnostic concordance for invasive breast carcinoma and benign biopsy specimens without atypia but lower agreement for biopsy specimens with atypia (eg, ADH) and DCIS. However, we did not determine whether the assurance behaviors associated with nervousness were related to specific diagnoses.14

Our findings suggest that concerns of medical malpractice in pathology, a high-claim severity field, are consistent with those identified in high-claim frequency specialties. A recent survey of anesthesiologists indicated that they were concerned about how medical malpractice claims would damage their reputation among colleagues (43%) and patients (57%) and would be revealed in online physician-grading sites (85%) and in the National Practitioner Data Bank (83%).17 In a recent survey of neuroradiologists, 74% reported concern over medical malpractice, and 81% believed the medicolegal system was weighted toward the plaintiff.18

Once a medical malpractice claim is made, the average length of time for resolution is 5 years.19 The average pathologist experiences a claim every 12 years.5 A large professional liability insurer recently reported that the average indemnity payment for pathologists was $383,509, higher than the mean across all medical specialties ($274,887) and high-risk specialties such as neurosurgery ($344,811).4 Time and money are not, however, the only variables affecting pathologists’ heightened concerns over malpractice liability. Direct communication with patients has been identified in previous studies as an effective way to reduce lawsuits.20 However, pathologists have little to no contact with patients on a routine basis,21 preventing pathologists from benefiting from positive patient-physician relationships as a protective measure. Risk managers are aware of the potential for serious emotional harm to pathologists caused by lawsuits,22 and the possibility of a malpractice lawsuit has been described as a personal crisis for pathologists.23

Defensive medicine has potentially serious implications for cost and quality of care to patients. Although tort reforms have shown modest reductions in costs from malpractice claims,24 even greater reductions may come from new approaches aimed at reducing assurance behaviors. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation (Advancing Medical Professionalism to Improve Health Care) launched the “Choosing Wisely Initiative” to promote patient care that is truly necessary and supported by evidence.25 In response to this challenge, the American Society for Clinical Pathology has joined more than 70 national organizations to produce a list of common tests and procedures that may be unnecessary in an effort to mitigate the overuse or misuse of medical procedures that provide little or no benefit to patients. In 2013, the Center for American Progress recommended a “safe harbor” for physicians who document adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines.26 These measures are aimed at improving the quality of care and patient safety, while reducing costs associated with defensive medicine.

This study has several limitations. We assessed perceptions of assurance behaviors, not actual clinical practices; thus, these behaviors may have been either over- or underreported. It may also be the case that the assurance behaviors endorsed by responders were used due to reasons beyond concerns about medical malpractice, such as to improve diagnostic accuracy or patient safety. We did not ask responders about assurance behaviors for different sizes of lesions or types of biopsies; assurance behaviors related to core biopsy specimens may be quite different from those in response to excisional biopsy specimens. We did not survey pathologists about other defensive medicine practices, known as avoidance behaviors, which involve physicians’ efforts to distance themselves from sources of legal risk, such as avoiding potentially contentious patients or risky procedures and treatments.7,8 Pathologists have less opportunity to use avoidance behaviors; thus, the focus of this study was on assurance behaviors. In addition, survey questions were worded specifically about breast cases. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to other subspecialties of surgical pathology. Finally, personal histories of malpractice and other covariates were self-reported in this study and not verified. Given the sensitivity of the topic, experiences with medical malpractice may have been underreported. Only 14 of the 66 pathologists who reported being sued for medical malpractice were sued for cases that involved breast pathology.

Strengths of our study included a survey response rate of 65% of eligible invitees, which is higher than national standards for physician surveys.27 Our data were gathered from eight geographic regions and included responses from both academic and community pathologists. The sample reflects states with a variety of medical malpractice rates, laws (ie, punitive damages, different damage caps), and malpractice reform measures, improving generalizability. Finally, the survey questions were developed for breast pathology and specifically refined with input from breast pathologists. This allowed us to probe more deeply into assurance behaviors beyond our earlier findings that breast pathologists favor obtaining second opinions.28

Conclusions

In conclusion, most breast pathologists in our study report using assurance behaviors to protect themselves from medical malpractice, resulting in additional tests and procedures. Regardless of whether breast pathologists have been personally sued, they demonstrate heightened concerns regarding medical malpractice and adjust their practices accordingly. These defensive medicine behaviors have potentially important implications for cost and patient care quality and safety. Measures to reduce assurance behaviors in breast pathology are needed.

Upon completion of this activity you will be able to:

define assurance behaviors.

list assurance behaviors commonly encountered in pathologists who practice breast pathology.

describe measures taken in the field of pathology to reduce costs of medical malpractice claims.

The ASCP is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The ASCP designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™ per article. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. This activity qualifies as an American Board of Pathology Maintenance of Certification Part II Self-Assessment Module.

Exam is located at www.ascp.org/ajcpcme.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01 CA140560 and R01 CA172343. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Physician Insurers Association of America. Breast Cancer Study 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Physician Insurers Association of America; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kern KA. The delayed diagnosis of breast cancer: medicolegal implications and risk prevention for surgeons. Breast Dis 2001;12:145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, et al. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:892–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med 2011;365:629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troxel DB. An insurer’s perspective on error and loss in pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:1234–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physicians’ views on defensive medicine: a national survey. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1081–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summerton N. Positive and negative factors in defensive medicine: a questionnaire study of general practitioners. BMJ 1995;310:27–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA 2005;293:2609–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keyhani S, Federman A. Doctors on coverage—physicians’ views on a new public insurance option and Medicare expansion. N Engl J Med 2009;361:e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Leary KJ, Choi J, Watson K, et al. Medical students’ and residents’ clinical and educational experiences with defensive medicine. Acad Med 2012;87:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston WF, Rodriguez RM, Suarez D, et al. Study of medical students’ malpractice fear and defensive medicine: a “hidden curriculum?” West J Emerg Med 2014;15:293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oster NV, Carney PA, Allison KH, et al. Development of a diagnostic test set to assess agreement in breast pathology: practical application of the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS). BMC Womens Health 2013;13:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison KH, Reisch LM, Carney PA, et al. Understanding diagnostic variability in breast pathology: lessons learned from an expert consensus review panel. Histopathology 2014;65:240–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmore JG, Longton G, Carney PA, et al. Diagnostic concordance among pathologists interpreting breast biopsy specimens. JAMA 2015;313:1122–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Survey of Pathologists. http://depts.washington.edu/epidem/research/BPathBaselineSurvey.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2015.

- 17.Burkle CM, Martin DP, Keegan MT. Which is feared more: harm to the ego or financial peril? a survey of anesthesiologists’ attitudes about medical malpractice. Minnesota Med 2012;95:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira NP, Lewin JS, Yousem KP, et al. Attitudes about medical malpractice: an American Society of Neuroradiology survey. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2024–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastaugh SR. Reducing litigation costs through better patient communication. Physician Executive 2004;30:36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen TC. Medicolegal issues in pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page L On the defensive: a physician’s confidence can shatter in the wake of a lawsuit. Modern Healthcare 2004;34:51, 54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis GG. Malpractice in pathology: what to do when you are sued. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:975–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bixenstine PJ, Shore AD, Mehtsun WT, et al. Catastrophic medical malpractice payouts in the United States. J Healthcare Qual 2014;36:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choosing Wisely. Partners ABIM Foundation; http://www.choosingwisely.org/partners/. Accessed September 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for American Progress. Release: CAP proposes medical-malpractice reforms to reduce cost of defensive medicine, improve patient care http://www.americanprogress.org/press/release/2013/06/11/65885/release-cap-proposes-medical-malpractice-reforms-to-reduce-cost-of-defensive-medicine-improve-patient-care/. Accessed September 10, 2014.

- 27.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geller BM, Nelson HD, Carney PA, et al. Second opinion in breast pathology: policy, practice and perception. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:955–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]