Abstract

The identification of the FtsZ ring by Bi and Lutkenhaus in 1991 was a defining moment for the field of bacterial cell division. Not only did the presence of the FtsZ ring provide fodder for the next 25 years of research, the application of a then cutting-edge approach--immunogold labeling of bacterial cells—inspired other investigators to apply similarly state-of-the-art technologies in their own work. These efforts have led to important advances in our understanding of the factors underlying assembly and maintenance of the division machinery. At the same time, significant questions about the mechanisms coordinating division with cell growth, DNA replication, and chromosome segregation remain. This review addresses the most prominent of these questions, setting the stage for the next 25 years.

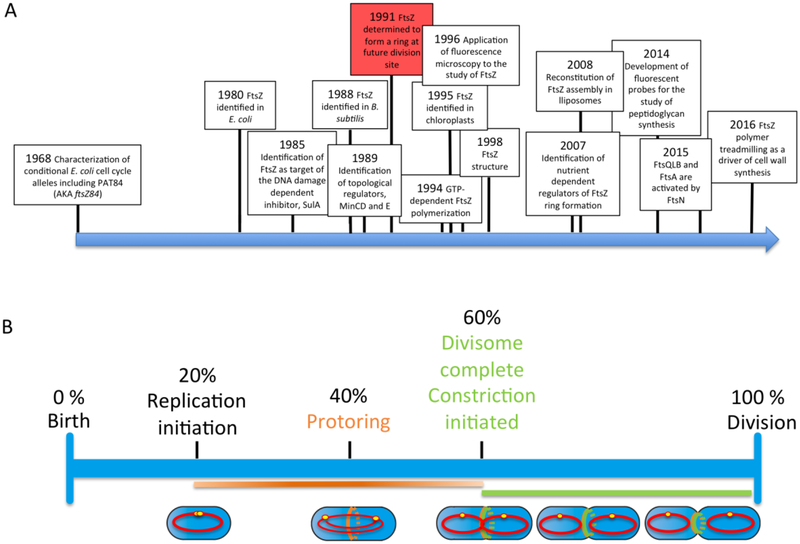

As a field, bacterial cell division has been defined by a series of breakthrough discoveries that resulted in new hypotheses followed by the steady addition of data providing molecular support for or against these hypotheses (Figure 1). Among these discoveries are the identification of conditional alleles in E. coli cell division genes [1], the identification of ftsZ, the tubulin-like cell division gene that serves as the basis for assembly of the cytokinetic machinery in bacteria and archaea [2], and the identification of the first set of proteins involved in the spatial regulation of cytokinesis [3].

Figure 1.

A. Bacterial cell division time-line of discovery. B. Division cycle progression time-line. Note that timing of division-related events are based on work in MC4100 cells cultured in minimal glucose medium [37,102]. Initiation time was calculated based on an 80 minute mass doubling period using the CCSim program available at https://sils.fnwi.uva.nl/bcb/cellcycle/ [103]

The most outstanding of all such breathroughs, however, is undoubtedly the 1991 report that FtsZ forms a ring at the nascent division site [4]. Utilizing cryo-EM in conjunction with immunogold staining, Bi and Lutkenhaus determined that FtsZ forms a ring-like structure at the future site of cell division in Escherichia coli. The identification of the FtsZ ring had an immediate and profound impact on the field. Most importantly, the presence of the FtsZ ring suggested bacteria are not so different from eukaryotes with regard to the use of cytoskeletal proteins for morphogenesis—a somewhat radical idea at the time.

In the intervening 25 years, a flurry of work focused on cloning additional cell division genes and characterizing their relationship with FtsZ. These efforts led to the conclusion that the FtsZ ring serves as a scaffold for assembly of the division machinery, a complex macromolecular structure composed of over 20 known proteins in E. coli and a similar number in the Gram-positive model organism Bacillus subtilis (although not all conserved). Together these proteins—collectively termed the divisome--coordinate cell envelope invagination during cytokinesis. Other research focused on illuminating factors contributing to the temporal and spatial regulation of FtsZ assembly and ensuring that division is coordinated with chromosome segregation [5–9].

Biochemical studies revealed the GTP-dependent formation of FtsZ polymers and determined that FtsZ assembly into single stranded polymers is a cooperative process [10,11]. FtsZ’s status as the first bacterial cytoskeletal protein was capped by solution of its structure in 1998, which revealed remarkable similarity with tubulin (solved in the same year) despite extremely limited sequence conservation [12,13]. Like tubulin, FtsZ monomers can bind GTP on their own, but dimerization is required for formation of a shared, GTPase active site [3,12].

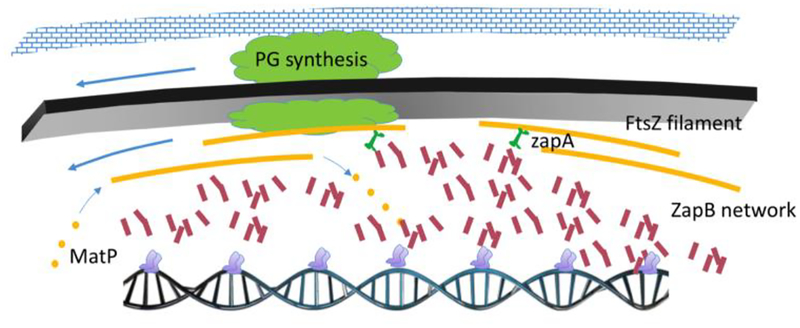

Most recently, advances in microscopy including single molecule tracking and structured illumination revealed the “FtsZ ring” to be a discontinuous structure composed of short single stranded polymers held together via lateral interactions [14]. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments illuminated the dynamic nature of the ring, demonstrating that monomer turnover within the ring occurs on average once every 9 seconds [15]. Finally, two papers published just this year indicate that FtsZ polymers serve as treadmilling platforms for the septal peptidoglycan synthesis machinery, countering the long held view that constriction of the FtsZ serves as a force generating mechanism to drive cytokinesis [16,17] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

FtsZ polymers serve as GTP-dependent treadmills for the cell wall synthesis machinery in E. coli and B. subtilis. The peptidoglycan synthesis machinery (green) is tethered to short FtsZ filaments (yellow). FtsZ-dependent GTP hydrolysis stimulates treadmilling in which GTP bound monomers are added to the putative (+) end of the filament and GDP bound monomers are released from the (−) end. Treadmilling leads to the processive insertion of cell wall material at the septum. In E. coli, the positive regulators of division, ZapA (green) and ZapB (red) help organize FtsZ polymers within the divisome. ZapB helps coordinate division with DNA replication via interactions with the terminus binding protein MatP (gray).

Despite these great strides, our picture of the molecular forces underlying the assembly and activity of the cell division machinery is far from complete. In particular, significant questions remain about the mechanisms controlling localization of the cell division machinery and coordinating its assembly and activation with cell growth, DNA replication, and chromosome segregation. Below we outline the most prominent of these, sketching a road map of sorts for the future of this field.

FtsZ recruitment to the nascent division site

Despite species-specific variations in its physical location, the selection of the nascent division site is a highly precise affair. In both E. coli and B. subtilis assembly of the division machinery takes place within ~2% of the cell’s geographical middle generating two identical daughter cells [18–20]. This level of precision suggests a multilayered process involving both positive regulation—in the form of factors that promote FtsZ assembly at the nascent septal site—and negative regulation—in the form of factors that prevent FtsZ assembly at aberrant subcellular positions such as close to cell poles or over unsegregated chromosomal material (AKA the nucleoid). The mechanisms by which different bacteria solve this problem appear to differ substantially.

Division site selection in B. subtilis: ready-set-go

Data from the Wake and Harry laboratories strongly implicate the initiation of DNA replication in the positional regulation of FtsZ in B. subtilis [18,21]. Bacterial DNA replication precedes assembly of FtsZ and is initiated by the binding of the AAA+ ATPase DnaA to the origin of replication (oriC) at midcell. DnaA binding results in open complex formation, permitting the replication machinery to load and replication fork elongation to proceed. In B. subtilis, blocking replication at initiation results in elongated cells with single, medially positioned chromosomes [18]. The FtsZ ring is off-center in these cells, immediately adjacent to the unsegregated nucleoid. Strikingly, when DNA replication initiation and open complex formation is allowed to proceed, but replication fork elongation is blocked, FtsZ assembly shifts to midcell.

Based on these observations, Harry and Moriya proposed a “ready-set-go” model in which assembly of the DNA replication initiation machinery at the origin, readies (or “potentiates”) midcell for FtsZ assembly [21]. Although the molecular mechanism underlying the ready-set-go model remains elusive, the idea that medial division site selection requires a handoff between the DNA replication machinery and FtsZ is appealing. Not only does it provide a satisfying link between the two pillars of the cell cycle, DNA replication and cytokinesis, but it also explains why increases in intracellular levels of FtsZ has a very modest impact on the timing and frequency of medial FtsZ ring in E. coli and B. subtilis formation [22,23] (For an excellent review of the factors coordinating division with DNA replication and chromosome segregation see [24].)

Division site selection: positive regulation by “marker” proteins

While similar localization determinants have yet to be identified in E. coli and B. subtilis, in a wide range of organisms, FtsZ assembly at the nascent septum depends on the activity of a regulatory protein that marks in the location of the future division site. In Myxococcus xanthus, PomZ, is recruited to midcell prior to FtsZ and promotes FtsZ assembly at this position [25]. PomZ is a homolog of ParA, an ATPase implicated in plasmid and chromosome partitioning, supporting a connection between DNA replication and cell division. MapZ (also known as LocZ), forms a ring at midcell in the Gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae, prior to FtsZ recruitment, where it serves to drive assembly of the division machinery [26]. After division, the MapZ ring splits in two and moves to the future division site in the newborn daughter cells. Although FtsZ is dispensable for hyphal growth in Streptomyces coelicolor [27], it is absolutely required for sporulation, which requires the transformation of long syncytial filaments into individual exospores. During this transformation, SsgA localizes to internucleoid spaces, recruiting first SsgB and then FtsZ to this position to initiate assembly of the cytokinetic machinery [28]. In all these cases, how these “marker” proteins recognize the nascent septal site remains an open question.

Corralling FtsZ

FtsZ assembly is subjected to multiple layers of regulation before, during, and after establishment of the nascent division site to promote efficient assembly of the cell division machinery ensure orderly progression through the cell cycle. Regulatory proteins include EzrA, which inhibits aberrant FtsZ assembly along the longitudinal axis of the cell in B. subtilis, and MatP and ZapB, which coordinate interactions between the division machinery and the terminus of DNA replication during chromosome segregation in E. coli [29a and b,30], Most prominent among such regulatory factors are the Min proteins, which inhibit FtsZ assembly at aberrant positions, particularly cell poles, and DNA-associated nucleoid occlusion proteins (NO), SlmA in E. coli and Noc in B. subtilis, which help prevent FtsZ assembly over the unsegregated chromosomes [8,9]. Importantly, cells defective in both Min and NO are still capable of establishing a medial division site with remarkable precision, counter to the oft suggested, yet erroneous idea that they play a primary role in medial division site selection [31–33]. Division is overwhelmingly medial in B. subtilis min mutants, and septation is more or less equally distributed between medial and polar positions in E. coli cells defective in min gene function [33–35]. NO in particular, appears to be primarily an insurance policy as NO mutants are essentially indistinguishable from wild type cells except under conditions in which DNA segregations is severely perturbed or in the absence of min. At the same time, while not essential for establishment of a medial division site in E. coli or B. subtilis, NO in Vibrio cholera is strongly involved in timing and position of its Z-ring reinforcing the value of studying essential processes in multiple organisms.[36].

Recruitment of the “late” division proteins

Assembly of the division machinery is a multi-step process involving two sets of factors: the so-called “early and late” division proteins. The early proteins include FtsZ and its membrane anchor FtsA, both of which are highly conserved among the bacteria, as well as other less well conserved factors including ZipA, EzrA, and the Zaps. The first to assemble at the division site, the early division proteins form what is collectively termed the “proto-ring” (also known as the Z-ring). Proto-ring formation is followed by a time delay that can occupy up to 20% of the cell cycle, after which the “late division proteins” assemble [22,37]. The late genes include the transpeptidase FtsI, and FtsW [3,38], both of which are required for synthesis of the septal wall [39,40]. The precise function of FtsW is somewhat unclear. Significant data support a role for the enzyme as a transporter of Lipid II linked cell wall precursors from the cytoplasm to the periplasm [41]. At the same time, FtsW shares a limited amount of homology with the putative elongation-specific transglycosylase RodA, raising the possibility it might serve a similar function during synthesis of septal peptidogylcan [38].

As with FtsZ, the mechanisms controlling late protein recruitment to the proto-ring are poorly understood. Overproduction of FtsZ in B. subtilis accelerates proto-ring formation somewhat, yet does not alter the timing of late cell division protein recruitment [22]. In E. coli, overproduction of FtsN—which interacts with both the proto-ring and the late division proteins—stabilizes the divisome but does not reduce the time between early and late cell division protein localization to midcell [37,42]. Like FtsZ, the concentration of late proteins is more or less constant over the course of the cell cycle in, suggesting recruitment is governed at the level of assembly [43].

It is possible that initial invagination of the cell membrane driven by the proto-ring serves as a temporal and topological marker for assembly of the late proteins. However, there is conflicting data about the potential for the proto-ring to initiate constriction in the absence of the late proteins[44]. On the one hand, purified FtsZ and FtsA or purified FtsZ fused to the membrane binding amphipathic helix of FtsA are sufficient for GTP dependent constriction of liposomal membranes [45,46]. On the other hand, insertion of amphipathic helices in between lipids is known to strongly deform liposomes [47] and the amphiphathic helix of FtsA is no exception (H. Strahl & LH, unpublished). It is thus debatable how well these in vitro studies reflect the situation in vivo, all the more so as these studies do not take into account the contribution of membrane potential, which is essential for FtsA function [48]. Significantly, cryo-EM work has failed to find evidence for membrane invagination by the proto-ring [49], arguing against a role for local membrane curvature in triggering recruitment of late cell division proteins.

Instead, recent work suggests that cooperative assembly of late proteins is stimulated in response to interactions between FtsA and the late protein FtsN that alter FtsA’s conformation and stabilize assembly of three conserved bitopic transmembrane proteins; FtsQ, FtsL and FtsB (DivIB, FtsL, and DivIC in B. subtilis) [50–52]. Lacking any apparent enzymatic function, FtsQLB localize as a group and stability of all three proteins depends on direct interactions between themselves and other late cell division proteins, particularly FtsW, FtsI and FtsN, all of which are recruited to the division site subsequent to FtsQLB [53–56]. Recent genetic data suggest that in E. coli the ABC-transporter-like complex, FtsEX, plays an important role in the timing of late protein recruitment, mediating the interaction between FtsA and FtsN, driving FtsA into the ‘on’ conformation and stimulating interaction with other components of the division machinery including FtsQLB[50].

Triggering cytokinesis

Formation of the septal wall requires the transpeptidase FtsI and its putative cognate transglycosylase FtsW, as well as a bifunctional transpeptidase-transglycosylase, PBP1b. While FtsI and FtsW are essential, PBP1b is dispensable in the presence of the normally elongation specific penicillin binding protein, PBP1a, suggesting the two PBPs are functionally interchangeable[57]. Allelic variants of ftsI and ftsW support a rate-limiting role for both in septal wall formation. In E. coli, a heat-sensitive FtsI variant, FtsI23, dramatically reduces the rate of septal wall synthesis while gain-of-function mutations in C. crescentus FtsW(A246T and F145L), and FtsI(I45V) significantly reduce cell size, consistent with accelerated division [44,58].

Despite their critical role in cytokinesis, recruitment of FtsI and FtsW to the nascent division site is insufficient to drive cytokinesis. Instead, a growing body of evidence supports a role for FtsN as a trigger for cytokinesis in part via direct interactions with FtsI and FtsW, but also through its role as an activator of FtsA mediated recruitment of FtsQLB [42,59–63] (Figure 3). In support of this idea, gain-of-function mutation in E. coli FtsA, FtsA* (R268W) and FtsL, FtsL* (E88K), appear to accelerate maturation of the divisome and bypass the essential functions of FtsN, as well as another essential cell division protein FtsK, suggesting that FtsN’s stimulatry role can be mediated solely through FtsA and FtsQLB under certain conditions [64–66].

Figure 3.

The E. coli divisome consists of two sets of factors: the early proteins (FtsZ, FtsA, ZipA, and ZapB in this figure), which constitute the proctoring, and the late proteins, whose recruitment is subsequent to and dependent upon the early proteins. FtsN bridges the early and late proteins, interacting with FtsA to stabilize the FtsQLB complex in the periplasm, and with FtsI/PBP3 and FtsW to stimulate cell wall synthesis (the latter interaction is not shown). Green starbursts indicate pre-activation state of FtsA, FtsN, FtsW and FtsI/PBP3 while green and red starburst indicates activated state. Additionally, FtsEX mediated ATP hydrolysis stimulates amidase activity (AmiA in this figure), thereby coordinating cell wall synthesis with hydrolysis to facilitate daughter cell separation. The model is not meant to reflect actual interaction stoichiometries, because they have yet to be determined. In addition, it is not yet clear if the amidases remain in complex with EnvC as drawn or if this interaction is also regulated. See text for details.

Significantly, although FtsA, FtsQLB, FtsI and FtsW are widely conserved, FtsN is limited to Gram-negative organisms, suggesting that other bacteria utilize different mechanisms to activate division. Consistent with this idea, cell division proteins are phosphorylated in several bacterial species, including B. subtilis, S. pneumoniae and Mycobacteria—but not E. coli, suggesting a potential additional route for activation (for a review see[67]).

Divisome ultrastructure and the role of the “bundlers”

Super resolution imaging indicates that the FtsZ ring is a discontinuous structure, appearing as larger nodes of high concentration separated by thinner regions of low concentration in both E. coli and B. subtilis [14,68,69]. The ring is similarly discontinuous in Caulobacter crescentus [70] and FtsZ forms patchy foci in Streptococcus pneumoniae [71]. Wide field and confocal microscopy of longitudinally dividing symbiotic bacteria that grow while attached with one pole on the skin of marine nematodes can initiate constriction using a discontinuous Z-elipse[72]. In these organisms constriction can also initiate from a single pole, utilizing an arc-like FtsZ structure instead of a ring [73]. Coupled with FtsZ’s strong tendency to form lateral interaction alone in vitro [74], and the large number of proteins identified as “FtsZ bundlers,” (for a review of this class of proteins see [75]) these observations supported a model in which the ring is composed of short FtsZ polymers held together in part via lateral interactions between single stranded protofilaments.

How lateral interactions relate to recent work indicating that FtsZ polymers “treadmill” in vivo-depolymerizing from one end (−) and polymerizing from the other end (+) is unclear. Treadmilling results in rapid rearrangement of single stranded polymers, effectively moving them in one direction at a speed of about 20–40 nm/sec depending on the bacterial species[16,17]. Treadmilling had previously been observed in vitro but its physiological significance was unclear prior to these studies [76]. Lateral interactions between protofilaments inhibit subunit turnover and reduce FtsZ’s innate GTPase activity. Bundling of FtsZ should thus reduce the treadmilling speed of the protofilaments. However, in E. coli treadmilling speed seems to be independent from the Zaps (ZapA, -B, -C, -D), all of which promote ring-formation in vivo and lateral interactions in vitro, as well as the spatial regulators, SlmA and MatP[16,75].

A lack of impact on treadmilling dynamics argues against the Zaps and other proteins that promote lateral interactions in vitro, doing the same in vivo. Based on an average speed of 30 nm/sec of treadmilling, the GTPase activity of E. coli and B. subtilis FtsZ should be approximately 0.3–0.6 mol GTP/mol FtsZ/sec at 21°C [17], which is much slower than the in vitro GTPase activity of 4.8 mol Pi/mol E. coli FtsZ/sec at 30°C[77,78], but similar to the 0.8 mol Pi/mol B. subtilis FtsZ/sec at 37°C under non-bundling conditions. Therefore, the in vivo speed of treadmilling does not exclude bundling. One possibility is that “bundling: proteins play a different role in vivo, ensuring that FtsZ filaments are maintained within the plane of the nascent septal site. For example, this large class of proteins might be important for filling in gaps between FtsZ protofilament clusters to maintain FtsZ’s circumferential orbit. Consistent with this model, ZapA and ZapB molecules are visible by super resolution microscopy between FtsZ clusters [79].

The role of FtsZ’s C-terminal linker domain and conserved C-terminal peptide in establishing and maintaining the ultrastructure of the FtsZ ring is another outstanding question. The flexible C-terminal linker is critical for FtsZ assembly dynamics both in vitro and in vivo [80,81]. This intrinsically disordered region averages ~50–60 residues in length in all but the alpha-proteobacteria where it can be over 200 residues. For example, in C. crescentus the C-terminal linker is ~150 residues in length and appears to mediate interactions between FtsZ and the cell wall synthesis machinery in addition to playing a role in FtsZ assembly [82]. The C-terminal peptide—a highly conserved set of approximately a dozen residues at the very end of the FtsZ polypeptide—has been implicated in interactions between FtsZ and a wide range of modulatory proteins (e.g. [83–85]). At the seame time, its high degree of evolutionary conservation contrasts strongly with the lack of conservation among modulatory proteins, raising the possibility that the C-terminal peptide may help mediate longitudinal interactions between FtsZ subunits, and along with the C-terminal linker, contribute to the cooperative nature of FtsZ assembly [86].

Membrane fusion and daughter cell separation

Despite occupying a respectable portion of the division cycle, we have yet to identify the factors required for the last step in division: the membrane fusion event that generates two independent daughter cells. Like the assembly of the divisome, its disassembly is a time consuming event that occupies approximately 15% of the cell division cycle [87,88]. In E. coli FtsZ and its membrane tethers FtsA and ZipA have left the closing septum well before the daughter cells are separated in two different compartments. The cytoplasm is compartmentalized before the periplasm [89] and a subpopulation of FtsN molecules together with FtsK, ZapB, and MatP all remain at mid cell after FtsI and the FtsQLB complex have left [87]. FtsK and MatP remain at midcell even after the other five proteins have moved away (TdB unpublished). By virtue of its role as a large integral membrane complex involved in translocating DNA trapped by the invaginating septum, and its persistence at the division site, FtsK is a good candidate for driving closure of the cytoplasmic membrane similar to the activity of SpoIIIE during sporulation in B. subtilis[90]. Since the essential membrane binding domain of FtsK can be bypassed by the FtsL* and FtsA* mutants [91], it seems unlikely to be the only protein involved in membrane closure. Also, the periplasmic part of FtsK is very small and unlikely to play a significant role in the closure of the peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane. An alternative for this is the Tol-Pal system, which bridges the entire cell envelope (inner membrane, cell wall, and outer membrane). Tol-Pal is involved in the coordination of concerted outer membrane and cell wall invagination [92] and possibly in lipid retrogade transport [93]. TolB follows the dynamics of FtsN (TdB unpublished) consistent with a role in the later stages of division. Cell wall cleavage between newly formed daughter cells is governed by the peptidoglycan hydrolases that are activated by FtsEX [94–97]. In agreement, the amidase AmiC localizes at midcell until daughter cell separation is complete [98,99](TdB unpublished). In Streptococcus pneumoniae the peptidoglycan hydrolase PcsB appears to serve the same role as E. coli amidases. PcsB activity is stimulated by the divisome proteins FtsEX, which transverses the plasma membrane to activate PcsB on the outer surface of the cell envelope. Once activated, PcsB monomers interact with their counterparts in the opposing cell to “unzip” the intervening peptidoglycan linking the two daughter cells [100,101].

Conclusion

The study of bacterial cell division and cell cycle regulation has come a long way since Yukinori Hirota and Antoinette Ryter attempted to make sense of a collection of conditional E. coli mutants in the laboratory of François Jacob [1]. (It is fitting that the field of bacterial cell division has its origins in this lab, as it was Jacob who stated that the “Le rêve d’une bactérie doit devenir deux bactéries.” The dream of a bacterium is to become two bacteria) Important as it was, Bi and Lutkenhaus’ discovery that FtsZ forms a ring was only a beginning [4], raising a host of questions that have kept many laboratories including our own busy for a quarter century. While a good number of such mysteries have been solved, many exciting questions—including those highlighted above--remain unanswered. Recent advances in imaging and image analysis have made some of the questions tractable for the first time. Others, particularly those that involve analysis of essential and nearly essential factors, will require significant creativity and industry to solve. Despite these challenges, the compelling nature of the subject matter coupled with the well-known power of microbial genetics gives us confidence that the field will continue to thrive and grow for many years to come.

The Divisome at 25: Highlights.

The discovery of the FtsZ ring by Bi and Lutkenhaus in 1991 was a defining moment in the field of bacterial cell division

The past 25 years of research have led to important discoveries that significantly advance our understanding of the factors responsible for the spatial and temporal regulation of bacterial cell division

- At the same time several important outstanding questions remain, including:

- The molecular mechanism(s) stimulating FtsZ assembly at midcell in Escherichia coli and B. subtilis

- The factors driving recruitment of the late cell division proteins to the divisome and initiating cytokinesis

- The ultrastructure of the bacterial cytokinetic ring

- The mechanism(s) underlying membrane fusion and daughter cell separation at the end of cytokinesis

Acknowledgments

Work in the den Blaauwen laboratory is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO-ALW (822.02.019) and ZonMW European program JPIAMR (20540.0001). Work in the Hamoen laboratory is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO-STW (Vici 12128). Work in the Levin laboratory is funded by National Institutes of Health grant GM64671. PAL was also supported by a grant from the Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program. We would like to thank the KEIO-collection from the National BioResource Project (NBRP), Shizuoka, Japan for generously provided strains for the last 10 years to all of those who have asked for them. This service has facilitated more experiments than we can count and has been an invaluable asset to the field.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

* and ** indicate papers of special (*) and outstanding (**) significance

- 1.Hirota Y, Ryter A, Jacob F: Thermosensitive Mutants of E. coli Affected in the Processes of DNA Synthesis and Cellular Division. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 1968, 33:677–693.**The first paper to categorize conditional alleles of cell cycle genes by function.

- 2.Lutkenhaus JF, Wolf-Watz H, Donachie WD: Organization of genes in the ftsA-envA region of the Escherichia coli genetic map and identification of a new fts locus (ftsZ). J. Bacteriol 1980, 142:615–620.**Identification of the gene encoding FtsZ.

- 3.de Boer PA, Crossley RE, Rothfield LI: A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E. coli. Cell 1989, 56:641–649.**Elegant genetic paper describing the cloning and function of the min genes in E. coli.

- 4.Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J: FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature 1991, 354:161–164.** The first observation that FtsZ forms a ring at midcell, this paper stimulated a frenzy of research that has been going strong for over 25 years.

- 5.Thanbichler M, Shapiro L: MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell 2006, 126:147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin PA, Kurtser IG, Grossman AD: Identification and characterization of a negative regulator of FtsZ ring formation in Bacillus subtilis. P Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:9642–9647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raskin DM, de Boer PA: Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. P Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:4971–4976.**The discovery of ATP-dependent oscillation of the positional regulator of FtsZ, MinD in E. coli. Understanding the rationale and mechanisms underlying MinD’s distinctive, ATP-dependent oscillating behavior, has kept many bacteriologist and biophysicists off the streets. The mystery is made all the more interesting by the absence of MinD oscillation in the Gram-positve model organism, B. subtilis.

- 8.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PAJ: SlmA, a nucleoid-associated, FtsZ binding protein required for blocking septal ring assembly over Chromosomes in E. coli. Mol. Cell 2005, 18:555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu LJ, Errington J: Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 2004, 117:915–925.* The first paper to provide a partial explanations for the long standing observation that Z-rings are not formed over the nucleoids.

- 10.Romberg L, Simon M, Erickson HP: Polymerization of FtsZ, a bacterial homolog of tubulin. Is assembly cooperative? J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276:11743–11753.*In the first paper to rigorously examine the biochemistry of FtsZ assembly, Romberg, Simon and Erickson, investigate the nature of FtsZ polymerization in vitro, testing models for both cooperative (tubulin-like) and non-cooperative (isodesmic) assembly.

- 11.Miraldi ER, Thomas PJ, Romberg L: Allosteric Models for Cooperative Polymerization of Linear Polymers. Biophys. J 2008, 95:2470–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe J, Amos LA: Crystal structure of the bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ. Nature 1998, 391:203–206.**Structural evidence strongly supporting an evolutionary link between FtsZ and tubulin.

- 13.Nogales E, Whittaker M, Milligan RA, Downing KH: High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell 1999, 96:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu G, Huang T, Buss J, Coltharp C, Hensel Z, Xiao J: In vivo structure of the E. coli FtsZ-ring revealed by photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM). PLoS ONE 2010, 5:e12680–16.**This paper provides the first high-resolution image of the Z-ring.

- 15.Anderson DE, Gueiros-Filho FJ, Erickson HP: Assembly dynamics of FtsZ rings in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli and effects of FtsZ-regulating proteins. J. Bacteriol 2004, 186:5775–5781.** Presents the first evidence supporting dynamic turnover of FtsZ in the Z-ring. A early prelude to the treadmilling papers of Yang et al and Filho et al, this study had a strong impact on how investigators interpreted the role of modulatory proteins in FtsZ ring formation and divisome activity.

- 16.Yang X, Lyu Z, Miguel A, McQuillen R, Huang KKC, Xiao J: GTPase activity-coupled treadmilling of the bacterial tubulin FtsZ organizes septal cell-wall synthesis. 2016. bioRxiv 10.1101/077610** Pioneering study redefining our understanding of the role of FtsZ as a coordinator of the cell division machinery during septal cell wall synthesis (see also Filho et al).

- 17.Filho AB, Hsu YP, Squyres G, Kuru E, Wu F: Treadmilling by FtsZ filaments drives peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial cell division. bioRxiv 2016, 10.1101/077560**Pioneering study redefining our understanding of the role of FtsZ as a coordinator of the cell division machinery during septal cell wall synthesis (see also Yang et al).

- 18.Harry EJ, Rodwell J, Wake RG: Co-ordinating DNA replication with cell division in bacteria: a link between the early stages of a round of replication and mid-cell Z ring assembly. Mol. Microbiol 1999, 33:33–40.* Provides the first evidence for a link between DNA replication and establishment of a medial division site in B. subtili.s

- 19.Migocki MD, Freeman MK, Wake RG, Harry EJ: The Min system is not required for precise placement of the midcell Z ring in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO Rep 2002, 3:1163–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu XC, Margolin W: FtsZ ring clusters in min and partition mutants: role of both the Min system and the nucleoid in regulating FtsZ ring localization. Mol. Microbiol 1999, 32:315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriya S, Rashid RA, Rodrigues CDA, Harry EJ: Influence of the nucleoid and the early stages of DNA replication on positioning the division site in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol 2010, 76:634–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gamba P, Veening JW, Saunders NJ, Hamoen LW, Daniel RA: Two-step assembly dynamics of the Bacillus subtilis divisome. J. Bacteriol 2009, 191:4186–4194.* Defines divisome assembly as a two-step process in B. subtilis (see also Aarsman et al).

- 23.Weart RB, Levin PA: Growth rate-dependent regulation of medial FtsZ ring formation. J. Bacteriol 2003, 185:2826–2834.*Presents the first data indicating that FtsZ ring formation is governed primarily at the level of FtsZ assembly rather than cell cycle dependent changes in concentration.

- 24.Hajduk IV, Rodrigues CDA, Harry EJ: Connecting the dots of the bacterial cell cycle: Coordinating chromosome replication and segregation with cell division. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2016, 53:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treuner-Lange A, Aguiluz K, van der Does C, Gómez-Santos N, Harms A, Schumacher D, Lenz P, Hoppert M, Kahnt J, Muñoz-Dorado J, et al. : PomZ, a ParA-like protein, regulates Z-ring formation and cell division in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol. Microbiol 2013, 87:235–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleurie A, Lesterlin C, Manuse S, Zhao C, Cluzel C, Lavergne J-P, Franz-Wachtel M, Macek B, Combet C, Kuru E, et al. : MapZ marks the division sites and positions FtsZ rings in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature 2014, 516:259–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick JR, Su EP, Driks A, Losick R: Growth and viability of Streptomyces coelicolor mutant for the cell division gene ftsZ. Mol. Microbiol 1994, 14:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willemse J, Borst JW, de Waal E, Bisseling T, van Wezel GP: Positive control of cell division: FtsZ is recruited by SsgB during sporulation of Streptomyces. Genes Dev 2011, 25:89–99.*Along with Fleurie et al and Treuner-Lange et al, provides the first evidence for the positive regulation of division site selection.

- 29a.Espéli O, Borne R, Dupaigne P, Thiel A, Gigant E, Mercier R, Boccard F: A MatP-divisome interaction coordinates chromosome segregation with cell division in E. coli. EMBO J 2012, 31:3198–3211.*Identification of a protein linking the proto-ring to the chromosome to coordinating division and cell cycle progression.Männik J, Castillo DE, Yang DE, Siopsis G, and Männik J: The role of MatP, ZapA and ZapB in chromosomal organization and dynamics in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44:1216–26.

- 30.Haeusser DP, Garza AC, Buscher AZ, Levin PA: The division inhibitor EzrA contains a seven-residue patch required for maintaining the dynamic nature of the medial FtsZ ring. J. Bacteriol 2007, 189:9001–9010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigues CDA, Harry EJ: The Min system and nucleoid occlusion are not required for identifying the division site in Bacillus subtilis but ensure its efficient utilization. PLoS Genet 2012, 8:e1002561.**Puts the proverbial nail in the coffin for the model that the min and NO proteins play a role in establishing the nascent division site at midcell in E. coli.

- 32.Bailey MW, Bisicchia P, Warren BT, Sherratt DJ, Männik J: Evidence for Divisome Localization Mechanisms Independent of the Min System and SlmA in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 2014, 10:e1004504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin PA, Shim JJ, Grossman AD: Effect of minCD on FtsZ ring position and polar septation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol 1998, 180:6048–6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaffé A, D’Ari R, Hiraga S: Minicell-forming mutants ofEscherichia coli: Production of minicells and anucleate rods. J. Bacteriol 1988, 170:3094–3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffé A, Boye E, D’Ari R: Rule governing the division pattern in Escherichia coli minB and wild type filaments. J. Bacteriol 1990, 172:3500–3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galli E, Poidevin M, Le Bars R, Desfontaines J-M, Muresan L, Paly E, Yamaichi Y, Barre F-X: Cell division licensing in the multi-chromosomal Vibrio cholerae bacterium. Nat. Microbiol 2016, 1:16094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aarsman ME, Piette A, Fraipont C, Vinkenvleugel TM, Nguyen-Disteche M, Blaauwen den T: Maturation of the Escherichia coli divisome occurs in two steps. Mol. Microbiol 2005, 55:1631–1645.* First paper to define divisome assembly as a two-step process mediated by two groups of proteins (early and late division proteins), with different functionality (see also Gamba et al).

- 38.Meeske AJ, Riley EP, Robins WP, Uehara T, Mekalanos JJ, Kahne D, Walker S, Kruse AC, Bernhardt TG, Rudner DZ: SEDS proteins are a widespread family of bacterial cell wall polymerases. Nature 2016, 537:634–638.*Challenges the decades old assumption that RodA and potentially FtsW are lipid-II translocases.

- 39.Wang L, Khattar MK, Donachie WD, Lutkenhaus J: FtsI and FtsW are localized to the septum in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 1998, 180:2810–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pogliano J, Pogliano K, Weiss DS, Losick R, Beckwith J: Inactivation of FtsI inhibits constriction of the FtsZ cytokinetic ring and delays the assembly of FtsZ rings at potential division sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1997, 94:559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammadi T, van Dam V, Sijbrandi R, Vernet T, Zapun A, Bouhss A, Diepeveen-de Bruin M, Nguyen-Distèche M, de Kruijff B, Breukink E: Identification of FtsW as a transporter of lipid-linked cell wall precursors across the membrane. EMBO J 2011, 30:1425–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai K, Xu Y, Lutkenhaus J: Cloning and characterization of ftsN, an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli isolated as a multicopy suppressor of ftsA12(Ts). J. Bacteriol 1993, 175:3790–3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vischer NOE, Verheul J, Postma M, van den Berg van Saparoea B, Galli E, Natale P, Gerdes K, Luirink J, Vollmer W, Vicente M, et al. : Cell age dependent concentration of Escherichia coli divisome proteins analyzed with ImageJ and ObjectJ. Front. Microbiol 2015, 6:586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coltharp C, Buss J, Plumer TM, Xiao J: Defining the rate-limiting processes of bacterial cytokinesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514296113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osawa M, Anderson DE, Erickson HP: Reconstitution of contractile FtsZ rings in liposomes. Science 2008, 320:792–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osawa M, Erickson HP: Liposome division by a simple bacterial division machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2013, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222254110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu ZL, Gogol EP, Lutkenhaus J: Dynamic assembly of MinD on phospholipid vesicles regulated by ATP and MinE. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99:6761–6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strahl H, Hamoen LW: Membrane potential is important for bacterial cell division. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107:12281–12286.* Highlights a role for proton motive force as a regulator of divisome assembly.

- 49.Daley DO, Skoglund U, Söderström B: FtsZ does not initiate membrane constriction at the onset of division. Sci. Rep 2016, 6:33138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du S, Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J: FtsEX acts on FtsA to regulate divisome assembly and activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, 113:E5052–61.*Very elaborate and elegant genetic analysis of the function of FtsEX.

- 51.Busiek KK, Eraso JM, Wang Y, Margolin W: The early divisome protein FtsA interacts directly through its 1c subdomain with the cytoplasmic domain of the late divisome protein FtsN. J. Bacteriol 2012, 194:1989–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Busiek KK, Margolin W: A role for FtsA in SPOR-independent localization of the essential Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsN. Mol. Microbiol 2014, 92:1212–1226.*Together with other first class work from the Margolin laboratory, identifies a key role for FtsA and FtsN in stimulating recruitment and activation of the late cell division proteins.

- 53.Daniel RA, Noirot-Gros MF, Noirot P, Errington J: Multiple interactions between the transmembrane division proteins of Bacillus subtilis and the role of FtsL instability in divisome assembly. J. Bacteriol 2006, 188:7396–7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buddelmeijer N, Beckwith J: A complex of the Escherichia coli cell division proteins FtsL, FtsB and FtsQ forms independently of its localization to the septal region. Mol. Microbiol 2004, 52:1315–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen JC, Beckwith J: FtsQ, FtsL and FtsI require FtsK, but not FtsN, for co-localization with FtsZ during Escherichia coli cell division. Mol. Microbiol 2001, 42:395–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robson SA, Michie KA, Mackay JP, Harry E, King GF: The Bacillus subtilis cell division proteins FtsL and DivIC are intrinsically unstable and do not interact with one another in the absence of other septasomal components. Mol. Microbiol 2002, 44:663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vollmer W, Bertsche U: Murein (peptidoglycan) structure, architecture and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2008, 1778:1714–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Modell JW, Kambara TK, Perchuk BS, Laub MT: A DNA damage-induced, SOS-independent checkpoint regulates cell division in Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS Biol 2014, 12:e1001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karimova G, Robichon C, Ladant D: Characterization of YmgF, a 72-residue inner membrane protein that associates with the Escherichia coli cell division machinery. J. Bacteriol 2009, 191:333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fraipont C, Alexeeva S, Wolf B, van der Ploeg R, Schloesser M, Blaauwen den T, Nguyen-Distèche M: The integral membrane FtsW protein and peptidoglycan synthase PBP3 form a subcomplex in Escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 2011, 157:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerding MA, Liu B, Bendezú FO, Hale CA, Bernhardt TG, de Boer PAJ: Self-enhanced accumulation of FtsN at Division Sites and Roles for Other Proteins with a SPOR domain (DamX, DedD, and RlpA) in Escherichia coli cell constriction. J. Bacteriol 2009, 191:7383–7401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bertsche U, Kast T, Wolf B, Fraipont C, Aarsman MEG, Kannenberg K, Rechenberg Von M, Nguyen-Distèche M, Blaauwen den T, Höltje J-V, et al. : Interaction between two murein (peptidoglycan) synthases, PBP3 and PBP1B, in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 2006, 61:675–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexeeva S, Gadella TWJ, Verheul J, Verhoeven GS, Blaauwen den T: Direct interactions of early and late assembling division proteins in Escherichia coli cells resolved by FRET. Mol. Microbiol 2010, 77:384–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsang M-J, Bernhardt TG: A role for the FtsQLB complex in cytokinetic ring activation revealed by an ftsL allele that accelerates division. Mol. Microbiol 2015, 95:925–944.* Elaborate and elegant genetic analysis confirming a role for the FtsQLB complex in activation of septal wall synthesis (see also Liu et al).

- 65.Pichoff S, Du S, Lutkenhaus J: The bypass of ZipA by overexpression of FtsN requires a previously unknown conserved FtsN motif essential for FtsA-FtsN interaction supporting a model in which FtsA monomers recruit late cell division proteins to the Z ring. Mol. Microbiol 2015, 95:971–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu B, Persons L, Lee L, de Boer PAJ: Roles for both FtsA and the FtsBLQ subcomplex in FtsN-stimulated cell constriction in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 2015, 95:945–970.* Elaborate and elegant genetic analysis confirming a role for the FtsQLB complex in activation of septal wall synthesis (see also Tsang and Bernhardt).

- 67.Manuse S, Fleurie A, Zucchini L, Lesterlin C, Grangeasse C: Role of eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinases in bacterial cell division and morphogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2016, 40:41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strauss MP, Liew ATF, Turnbull L, Whitchurch CB, Monahan LG, Harry EJ: 3D-SIM Super Resolution Microscopy Reveals a Bead-Like Arrangement for FtsZ and the Division Machinery: Implications for Triggering Cytokinesis. PLoS Biol 2012, 10:e1001389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rowlett VW, Margolin W: 3D-SIM Super-resolution of FtsZ and Its Membrane Tethers in Escherichia coli Cells 2014, 107:L17–L20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holden SJ, Pengo T, Meibom KL, Fernandez CF, Collier J, Manley S: High throughput 3D super-resolution microscopy reveals Caulobacter crescentus in vivo Z-ring organization P Natl Acad Sci USA 2014, 111:4566–4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacq M, Adam V, Bourgeois D, Moriscot C, Di Guilmi A-M, Vernet T, Morlot C: Bacterial cell division proteins as antibiotic targets. Bioorg. Chem 2014, 55:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leisch N, Verheul J, Heindl NR, Gruber-Vodicka HR, Pende N, Blaauwen den T, Bulgheresi S: Growth in width and FtsZ ring longitudinal positioning in a gammaproteobacterial symbiont. Curr. Biol 2012, 22:R831–2.* Offers a complete different view of Z-ring structure and function in an organism that is generically very similar to E. coli.

- 73.Leisch N, Pende N, Weber PM, Gruber-Vodicka HR, Verheul J, Vischer NOE, Abby SS, Geier B, Blaauwen den T, Bulgheresi S: Asynchronous division by non-ring FtsZ in the gammaproteobacterial symbiont of Robbea hypermnestra Nat. Microbiol 2016, 2:16182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buske PJ, Levin PA: The extreme C-terminus of the bacterial cytoskeletal protein FtsZ plays a fundamental role in assembly independent of modulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287:10945–10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang K-H, Durand-Heredia J, Janakiraman A: FtsZ ring stability: of bundles, tubules, crosslinks, and curves. J. Bacteriol 2013, 195:1859–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Loose M, Mitchison TJ: The bacterial cell division proteins FtsA and FtsZ self-organize into dynamic cytoskeletal patterns. Nat. Cell Biol 2014, 16:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Läppchen T, Hartog AF, Pinas VA, Koomen G-J, Blaauwen den T: GTP Analogue Inhibits Polymerization and GTPase Activity of the Bacterial Protein FtsZ without Affecting Its Eukaryotic Homologue Tubulin † Biochemistry 2005, 44:7879–7884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ray S, Jindal B, Kunal K, Surolia A, Panda D: BT-benzo-29 inhibits bacterial cell proliferation by perturbing FtsZ assembly. FEBS J 2015, 282:4015–4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buss J, Coltharp C, Shtengel G, Yang X, Hess H, Xiao J: A Multi-layered Protein Network Stabilizes the Escherichia coli FtsZ-ring and Modulates Constriction Dynamics. PLoS Genet 2015, 11:e1005128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buske P, Levin PA: A flexible C-terminal linker is required for proper FtsZ assembly in vitro and cytokinetic ring formation in vivo. Mol. Microbiol 2013, doi: 10.1111/mmi.12272.*Identification of FtsZ’s oft ignored C-terminal linker as an intinsically disorded peptide playing an important role in mediating FtsZ assembly and function (See also Gardner et al.)

- 81.Gardner KAJA Moore DA, Erickson HP: The C-terminal Linker of Escherichia coli FtsZ Functions as an Intrinsically Disordered Peptide. Mol. Microbiol 2013, doi: 10.1111/mmi.12279.*Identification of FtsZ’s oft ignored C-terminal linker as an intinsically disorded peptide playing an important role in mediating FtsZ assembly and function (See also Gardner et al.)

- 82.Sundararajan K, Miguel A, Desmarais SM, Meier EL, Casey Huang K, Goley ED: The bacterial tubulin FtsZ requires its intrinsically disordered linker to direct robust cell wall construction. Nat Commun 2015, 6:7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ma X, Margolin W: Genetic and functional analyses of the conserved C-terminal core domain of Escherichia coli FtsZ. J. Bacteriol 1999, 181:7531–7544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mosyak L, Zhang Y, Glasfeld E, Haney S, Stahl M, Seehra J, Somers WS: The bacterial cell-division protein ZipA and its interaction with an FtsZ fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography. EMBO J 2000, 19:3179–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Din N, Quardokus EM, Sackett MJ, Brun YV: Dominant C-terminal deletions of FtsZ that affect its ability to localize in Caulobacter and its interaction with FtsA. Mol. Microbiol 1998, 27:1051–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buske PJ, Mittal A, Pappu RV, Levin PA: An intrinsically disordered linker plays a critical role in bacterial cell division. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Söderström B, Mirzadeh K, Toddo S, Heijne von G, Skoglund U, Daley DO: Coordinated disassembly of the divisome complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 2016, 101:425–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Söderström B, Skoog K, Blom H, Weiss DS, Heijne von G, Daley DO: Disassembly of the divisome in Escherichia coli: evidence that FtsZ dissociates before compartmentalization. Mol. Microbiol 2014, 92:1–9.* First paper to characterize the disassembly of the divisome.

- 89.Skoog K, Soderstrom B, Widengren J, Heijne von G, Daley DO: Sequential Closure of the Cytoplasm and Then the Periplasm during Cell Division in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 2012, 194:584–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fleming TC, Shin JY, Lee S-H, Becker E, Huang KC, Bustamante C, Pogliano K: Dynamic SpoIIIE assembly mediates septal membrane fission during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Genes Dev 2010, 24:1160–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Draper GC, McLennan N, Begg K, Masters M, Donachie WD: Only the N-terminal domain of FtsK functions in cell division. J. Bacteriol 1998, 180:4621–4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gerding MA, Ogata Y, Pecora ND, Niki H, de Boer PAJ: The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol 2007, 63:1008–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thong S, Ercan B, Torta F, Fong ZY, Wong HYA, Wenk MR, Chng S-S, Storz G: Defining key roles for auxiliary proteins in an ABC transporter that maintains bacterial outer membrane lipid asymmetry. Elife 2016, 5:e19042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meisner J, Montero Llopis P, Sham L-T, Garner E, Bernhardt TG, Rudner DZ: FtsEX is required for CwlO peptidoglycan hydrolase activity during cell wall elongation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol 2013, 89:1069–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang DC, Tan K, Joachimiak A, Bernhardt TG: A conformational switch controls cell wall-remodelling enzymes required for bacterial cell division. Mol. Microbiol 2012, 85:768–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sham LT, Carlson EE, Winkler ME: Requirement of essential Pbp2× and GpsB for septal ring closure in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Molecular … 2012, [no volume]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Uehara T, Parzych KR, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG: Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J 2010, 29:1412–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Peters NT, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG: A fail-safe mechanism in the septal ring assembly pathway generated by the sequential recruitment of cell separation amidases and their activators. J. Bacteriol 2011, 193:4973–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rocaboy M, Herman R, Sauvage E, Remaut H, Moonens K, Terrak M, Charlier P, Kerff F: The crystal structure of the cell division amidase AmiC reveals the fold of the AMIN domain, a new peptidoglycan binding domain. Mol. Microbiol 2013, 90:267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bartual SG, Straume D, Stamsås GA, Muñoz IG, Alfonso C, Martínez-Ripoll M, Håvarstein LS, Hermoso JA: Structural basis of PcsB-mediated cell separation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Commun 2014, 5:3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sham LT, Jensen KR, Bruce KE, Winkler ME: Involvement of FtsE ATPase and FtsX Extracellular Loops 1 and 2 in FtsEX-PcsB Complex Function in Cell Division of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. MBio 2013, 4:e00431–13–e00431–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van der Ploeg R, Verheul J, Vischer NOE, Alexeeva S, Hoogendoorn E, Postma M, Banzhaf M, Vollmer W, Blaauwen den T: Colocalization and interaction between elongasome and divisome during a preparative cell division phase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 2013, 87:1074–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zaritsky A, Wang P, Vischer NO: Instructive simulation of the bacterial cell division cycle. Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 2011, 157:1876–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]