Abstract

Background.

Momentary affect and stress in mothers and their children may be an important predictor of food intake in the natural environment. This study hypothesized that there would be parallel actor and partner effects such that mothers’ and children’s negative affect (NA), positive affect (PA), and ability to cope with stress would be associated with their own and the other dyad member’s unhealthy and healthy food intake in a similar pattern.

Methods.

Participants included 202 mother-child dyads (child age range=8–12) who responded to randomly prompted ecological momentary assessment surveys via smartphone up to 7 times per day over 8 days, excluding time at school. At each prompt, mothers and children reported on their current NA, PA, and ability to cope with stress and foods consumed in the past 2 hours.

Results.

Mothers’ momentary ability to cope with stress predicted their own and their child’s pastries/sweets intake and their own fries/chips intake, and children’s momentary ability to cope with stress predicted their own pastries/sweets intake. Mothers and children who reported higher NA on average consumed more pastries/sweets, and children with higher NA on average consumed more fast food. Finally, mothers’ momentary PA predicted their own fruit/vegetable consumption.

Conclusions.

Findings provided evidence that the affect and ability to cope with stress of children and mothers predicted subsequent food intake. Given both actor and partner effects, the results show that targeting momentary mothers’ and children’s ability to cope with stress may have the greatest effect on reducing unhealthy food intake.

Keywords: diet, ecological momentary assessment, affect, stress coping

Obesity is a serious public health problem in children and adults with a prevalence of approximately 17% in children and 38% in adults (Flegal, Kruszon-Moran, Carroll, Fryar, & Ogden, 2016; Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010), and obesity is associated with numerous physical (e.g., hypertension, insulin resistance, sleep apnea) and mental health problems (e.g., reduced psychosocial functioning and psychiatric morbidity; Kelly, Daniel, Dal Grande, & Taylor, 2011). The range of co-occurring conditions associated with obesity underscores the severity of this health problem and the need for increased research on the etiology of obesity (Wilson & Sato, 2014). Dietary intake is a modifiable behavior with a clear impact on weight status and obesity risk (Te Morenga, Mallard, & Mann, 2013). However, the majority of adults and children do not meet the recommended minimum daily servings of fruits and vegetables, and many adults and children obtain much of their daily caloric intake from foods high in added sugars and solid fats (Mahabir et al., 2018; Reedy & Krebs-Smith, 2010).

Ecological systems theory outlines the multifaceted contexts that contribute to childhood obesity including individual, family, school, community, and society level factors (Davison & Birch, 2001). These factors each play an interactional role in individuals’ dietary intake, eating-related decisions, and home food environment (Rosenkranz & Dzewaltowski, 2008). However, research should consider both who is more likely to consume healthy and unhealthy foods, and also what factors explain eating-related decisions in the moment.

Research consistently demonstrates that food-related decisions can be affected by various non-physiological influencers (Macht, 2008). Of particular interest is the effect of psychological factors on food-related decisions. Affect and stress have been implicated in relation to food intake (e.g., Adam & Epel, 2007; Macht, 2008). Specifically, positive affect has been associated with choosing healthy foods (e.g., fruits/vegetables; Fedorikhin & Patrick, 2010; Jeffers et al., 2018), and negative affect has been associated with increased consumption of unhealthy foods (e.g., high sugar foods; Goldschmidt et al., 2014; Jansen et al., 2008; Jeffers et al., 2018). In addition, perceived stress has been shown to be associated with unhealthy food intake (Ng & Jeffery, 2003; Zellner et al., 2006).

Associations between affect, stress, and eating can be understood within the context of several psychological and physiological theoretical models of eating behavior. First, the affect regulation model suggests that individuals consume unhealthy foods, often in large quantities, in order to cope with feelings of negative affect, such as anger or sadness (Polivy & Herman, 1993). Second, the ego depletion model suggests that the ability to exert self-control is of limited availability, and this ability decreases as individuals experience stress and increased cognitive load, which in turn leads to more unhealthy eating (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). Third, Adam and Epel (2007) describe a theoretical model where psychological stress leads to activation of the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, which then causes unhealthy eating through hormone- and reward-related pathways. Finally, potential explanations for the association between positive affect and healthy food intake are that individuals experiencing positive affect may have a better ability to make healthier decisions (Isen, 2001) or may choose healthy foods in order to maintain the positive affective state (Wansink, Cheney, & Chan, 2003).

The majority of research on affect and stress in relation to eating behavior has been conducted in adults or children alone (e.g., Goldschmidt et al., 2014; Grenard et al., 2013; O’Reilly et al., 2015), and thus, less is understood about how mothers’ and their children’s affect and stress influence one another’s food intake. While adults are predominantly responsible for their own eating decisions, children rely on their parents or caretakers, primarily their mothers, to provide meals and snacks (Savage, Fisher, & Birch, 2007). Further, children often must ask their parents or caretakers permission for snacks throughout the day (Musher-Eizenman & Holub, 2007). Compared to toddlers who are almost fully reliant on parents or caretakers for food, children vary widely on their level of reliance on others for food. Thus, examining dyadic associations between mothers and children may be critical to understanding the relations of affect and stress to food intake in school-age children.

There are a number of ways mothers’ and children’s affect and stress may influence one another’s food intake. When mothers are feeling bad or stressed, they may practice less effortful parenting and thus may become more permissive with regard to what they allow their child to eat (Deater-Deckard, 1998). In addition, mothers who are stressed may take a break from watching their children which could allow children to eat pastries/sweets without their mother’s permission (Friedman & Billick, 2015). There also may be symbiotic associations between mothers’ and their child’s affect and stress where one dyad member’s affect or stress causes changes in the other dyad member’s affect or stress, which then is related to food intake (Waters, West, Karnilowicz, & Mendes, 2017).

A recent review found no evidence for an association between maternal stress and children’s diet quality (O’Connor et al., 2017); however, this review noted several critical limitations of past studies. First, previous studies have only examined between-subjects associations among maternal stress and children’s dietary intake behaviors using cross-sectional data. Second, studies have rarely considered dynamics of the dyad to examine the impact of both the mothers’ and children’s stress on each other’s dietary intake. Instead studies have primarily examined only the impact of the mother’s stress on their children’s dietary intake. Third, studies often use retrospective survey measures (e.g., food frequency questionnaires, 24-hour recalls), which are associated with a number of biases, notably retrospective recall bias, and this is especially problematic with regard to the assessment of dietary intake behaviors (Archer, Pavela, & Lavie, 2015). Given these limitations, research investigating momentary, within-subjects associations between mothers’ and their children’s stress and affect and diet intake behaviors using real-time data collection methodology is an important next step.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a real-time data capture methodology that uses repeated measures to collect information from individuals throughout the course of their daily lives (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). EMA methods combat many of the limitations of standard survey-based assessments, by allowing for the examination of momentary processes, decreasing the opportunity for recall bias and loss of variability from summary measures, and by allowing for the assessment of time-related antecedents and consequences of behaviors and states. EMA has been successfully used to examine dietary intake behaviors in adults and children of varying body weights (Goldschmidt et al., 2014; Grenard et al., 2013).

The goal of the present study was to use EMA to examine how children’s and their mothers’ momentary levels of negative affect, positive affect, and ability to cope with stress were associated with their own food intake and the other dyad member’s food intake using an actor-partner interdependence model (APIM; Cook & Kenny, 2005). APIMs suggest that the experiences and behaviors of members in a given dyad are inter-dependent (i.e., have an effect on one another). In this approach, data from both members of a dyad are included in statistical models. Interdependence is examined by including both actor (i.e., associations of affect and stress with one’s own food intake) and partner (i.e., associations of affect and stress with the other dyad member’s food intake) effects.

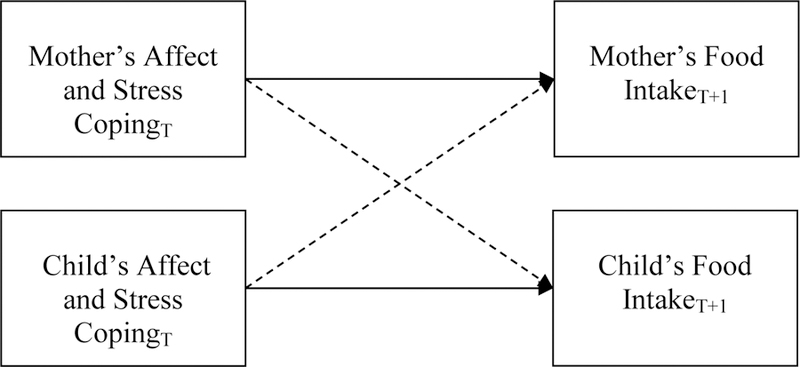

A conceptual EMA-based model of affect, ability to cope with stress, and food intake in mother-child dyads as described by APIM is displayed in Figure 1. It was hypothesized that greater within-subjects (i.e., momentary variation in a construct compared to one’s average) and between-subjects (i.e., an individual’s average score across the EMA recording period) negative affect and ability to cope with stress would predict subsequent higher likelihood of consumption of pastries/sweets, fries/chips, and fast food, and lower likelihood of consumption of fruits/vegetables, and greater between- and within-subjects positive affect would predict subsequent higher likelihood of consumption of fruits/vegetables. In addition, there would be parallel actor and partner effects such that mothers’ and children’s affect and ability to cope with stress would be associated with their own and the other dyads members food intake in a similar pattern.

Figure 1.

Conceptual multilevel actor-partner interdependence model of affect and perceived stress and food intake in mother-child dyads. Solid lines represent actor effects and dotted lines represent partner effects. Observed values were disaggregated into within-subjects effects (i.e., observed scores centered at each individual’s mean) and between-subjects effects (i.e., each individual’s average value across the ecological momentary assessment recording period). T = time.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The current study used data from three waves of data collection (Sept 2014 – May 2015) of the Mothers’ and Their Children’s Health (MATCH) Study. The MATCH study is a longitudinal examination of the effect of maternal behavior and stress on children’s obesity risk. MATCH focused on mothers because women in couples report taking greater responsibility for child care than their male partners (Yavorsky, Kamp Dush, & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2015). The MATCH Study is unique in that it utilizes multiple waves of EMA data spaced approximately 6-months apart to capture real-time information on stress, affect, and diet intake behaviors within school-age children (age 8–12) and their mothers. Additional information about the MATCH Study design can be found elsewhere (Dunton et al., 2015). An ethnically- and racially-diverse group of mothers and children were recruited from Southern California schools through study flyers distributed to classrooms, and information booths at school and community organized events. There were 310 dyads assessed for eligibility, and 248 of these dyads met eligibility criteria.

A total of 202 dyads enrolled in the study and completed Wave 1. Analyses included 191 mother-child dyads at Wave 1 who had usable EMA data for both mothers and children. Data was also included from dyads whom completed Wave 2 (n = 167) and Wave 3 (n = 152). Attrition analyses showed that dyads with boys were more likely to drop out at Wave 3; there were no predictors of attrition at Wave 2. Demographic variables from mothers and children at Wave 1 are displayed in Table 1. The mean age of children was 9.60 (SD = 0.92; Range = 8–12), and the mean age of mothers was 40.98 (SD = 6.13; Range = 26–57). Approximately 20% of children were in the overweight range and 16% were in the obese range, and 33% of mothers were in the overweight range and 33% were in the obese range. The mean BMI-z of children was 0.49 (SD = 1.06), and the mean BMI of mothers was 28.58 (SD = 6.45).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Child Gender | |

| Male | 93 (48.7) |

| Female | 98 (51.3) |

| Child Racea | |

| White | 87 (45.5) |

| Asian | 27 (14.1) |

| Black or African-American | 34 (17.8) |

| Otherb | 73 (38.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 5 (2.6) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 8 (4.2) |

| Child Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 102 (53.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | 89 (46.6) |

| Annual Household Incomec | |

| Less than $35,000 | 51 (26.8) |

| $35,001-$74,999 | 56 (29.5) |

| $75,000-$104,999 | 37 (19.5) |

| $105,000 and above | 46 (24.2) |

| Type of Household | |

| Single parent | 41 (21.5) |

| Two parents | 150 (78.5) |

| Mother’s Education Leveld | |

| Less than high school | 14 (7.5) |

| High school graduate | 62 (33.5) |

| College graduate | 63 (34.1) |

| Graduate or professional school | 46 (24.9) |

| Mother’s Employment Statuse | 106 (56.4%) |

| Work full-time | 49 (26.1%) |

| Work-part time | 10 (5.3%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (0.5%) |

| Retired | 6 (3.2%) |

| Disabled or student | 16 (8.5%) |

| Other |

Note: N=191 mother and child dyads.

Participants were allowed to select as many race categories as applied, thus this adds up to more than 100%.

Many participants indicated “Hispanic or Latino/a for their race, which was coded as “other.”

Income missing for one participant.

Mother’s education level is missing for six participants.

Employment status missing for three participants

Inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (a) child currently in 3rd – 6th grade, (b) child resides with mother at least 50% of time, and (c) ability of both mother and child to speak and read in English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria included: (a) use of medication for thyroid or psychological condition, (b) health condition limiting ability to be physically active, (c) child enrolled in a special education program due to concerns about reduced understanding of assent, (d) currently using oral or inhalant corticosteroids for asthma, (e) pregnancy, (f) child underweight (BMI < 5th% for age and sex) due to concerns about these children having a different set of health concerns, and (g) mother works more than two evenings (between 5–9pm) during the week, or more than one 8-hour weekend shift. Mothers who work often in the evenings and the weekends would miss much of the EMA recording periods (and would be away from their children often), which would affect the ability to evaluate study hypotheses. Maternal consent and child assent were obtained prior to any study assessment. The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Southern California and Northeastern University approved all parts of this study.

The present study examines data from Waves 1–3 of the study, which consisted of in-person visits during which participants completed paper and pencil surveys and anthropometric measures and received training on ambulatory equipment. Immediately following this visit, participants completed eight days of EMA surveys. The MATCH EMA application is a custom created Java application for Android Operating System (Google, Inc). Participants were invited to download and use the app on their personal Android device, and participants without a compatible device borrowed a study phone (MotoG). Mothers and children each had their own device. Through home Wi-Fi, EMA data was securely transferred from the device to a secure cloud server managed by Google for safe storage utilizing precautions such as encryption, network restrictions, and security protection (e.g., firewall, antivirus). Participants who were not responding consistently (lower than 80%) were flagged, and reminder calls were made by study staff to help increase response rates.

Measures

Ecological momentary assessment.

Mothers and their children each received EMA survey prompts for eight days, excluding time at school. Prompts were generated in stratified random sampling windows, with one prompt randomly occurring during each window (e.g., 3–4PM, 5–6PM). Children received three prompts on weekdays and seven prompts on weekends, and mothers received four prompts on weekdays and eight prompts on weekends. Mothers were randomly prompted during the first half of each window and children during the second half of each window to prevent any contamination effects from completing surveys concurrently. Sleep and wake times were customized for each participant. Each survey required approximately 2–3 minutes to complete, and if surveys were prompted during incompatible times, participants had the option to delay. Up to two reminder prompts were initiated within 10 minutes of the initial prompt, after which time the survey was closed. Each survey question was presented on a separate screen.

Affect and ability to cope with stress.

Children’s negative affect was measured with three items: “Right before the phone went off, how (1) mad, (2) sad, and (3) stressed were you feeling?” Mother’s negative affect was measured with three items: “Right before the phone went off, how (1) frustrated/angry, (2) sad/depressed, and (3) stressed were you feeling?” Affect items were each presented to the participant on a unique screen, and the response options consisted of a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Items were combined to create a negative affect summary score for mothers and children.

Children’s positive affect was measured using two items: “Right before the phone went off, how (1) happy and (2) joyful were you feeling?” Mother’s positive affect was measured using two items: “Right before the phone went off, how (1) happy and (2) calm/relaxed were you feeling?” Positive affect items for mothers were chosen to represent both high and low activation akin to the circumplex model of affect (Posner, Russell, & Peterson, 2005). However, this was not done with children due to concerns with children’s level of understanding. Scores for these two items were combined and averaged to create a positive affect summary score for mothers and children.

Ability to cope with stress was assessed with one item modified from the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) each for mothers (i.e., How certain do you feel that you can deal with all the things that you have to do RIGHT NOW?) and children (i.e., I can manage with all the things I have to do RIGHT NOW). For the ability to cope with stress items, mothers responded on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and children responded dichotomously yes or no, which were reverse-scored so that higher scores indicated less ability to cope with stress.

Food intake.

Mothers and children reported on recent dietary intake through the following EMA question: “Over the last 2 hours, which of these things have you done?” Both mothers and children indicated whether or not they had consumed the following: (a) pastries or sweets, (b) chips or fries, (c) fast food, and (d) fruits or vegetables. Participants were instructed to select all that applied. Only Fruits/vegetables were selected to represent healthy items due to concern over children’s ability to identify other healthy foods (e. g., whole grains and lean proteins). Unhealthy food items were selected to represent a range of high calorie, nutrient dense foods commonly consumed by both children and adults which are related to obesity risk (Rosenheck, 2008; Te Marenga et al., 2013). These items have been shown to have good concordance with 24-hour recall dietary assessments in children (O’Connor et al., 2018).

Statistical Analyses

EMA availability, descriptive statistics, and multilevel reliability estimates (ω; Geldhof, Preacher, & Zyphur, 2014) were computed. Little’s chi-square test was used to determine whether data was missing completely at random and appropriate missing data procedures were implemented. Multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM; Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010) via Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 2015) was used to examine prospective associations between mothers’ and their children’s affect and ability to cope with stress at a given prompt and food intake at the following prompt. Paths included in the models were mothers’ and child’s time-lagged affect and ability to cope with stress (i.e., t) as predictors of their own (i.e., actor effects) and the other dyad member’s (i.e., partner effects) food intake at the next EMA assessment point (i.e., t+1) within the same day; time between assessments varied between 2–3 hours. Negative affect, ability to cope with stress, and positive affect were examined as predictors in separate models. Also, each food outcome was examined in a separate model; outcomes included pastries/sweets, chips/fries, fast food, and fruits/vegetables.

Predictor variables were partitioned into between-subjects (individual differences) and within-subjects (momentary) effects, with individuals as the Level 2 and EMA observations as the Level 1 unit of analysis. All models were adjusted for demographic characteristics. Child outcomes were adjusted for child sex and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic); mother outcomes were adjusted for mother ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic); both mother and child outcomes were adjusted for household income. Effects are interpreted using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Effects were deemed significant if 0 was not in the CI, and CI size indicated precision.

Results

EMA Data Availability

Only assessments that had valid data for mother and child at two adjacent time points (i.e., t and t+1) were included in analyses. Across waves, there were a total of 16,404 prompts each for mothers and children. A total of 11,942 prompts were received by children and 12,056 prompts were received by mothers. Children responded to 9,223 prompts and mothers responded to 9,565 prompts. There were 3,423 prompts with valid responses from mothers and children at both the lagged and non-lagged EMA assessments.

The primary cause of incomplete case data for received prompts was prompt nonresponse in that the entire prompt, and all associated items, were missing (23% for children and 21% for mothers). Little’s chi-square test was significant suggesting that data was not missing completely at random, χ2(560)=2639.857, p<.001. Sensitivity analysis on prompt nonresponse was conducted using pattern mixture modeling (Bell & Fairclough, 2014) by first generating day-level missing data patterns by categorizing prompts as complete or incomplete cases for the set of predictors with the assumption that day-level missing data patterns may be informative. This step resulted in a number of missing data patterns of which only patterns with the highest prevalence rates and a cumulative prevalence of at least 50% of the analytic sample were considered, comprising three patterns. Binary variables indicating each of these patterns and the proportion of complete prompts for mother and child were then included as covariates of their own food intake outcomes in statistical models testing the primary hypotheses, respectively. While some of the patterns were significantly related to the outcome, none of the results for the hypothesized actor and partner effects changed appreciably suggesting that relationships of predictors and outcomes were not affected by missing data patterns.

Descriptive Statistics

Fruits/vegetables were consumed in 25.6% of prompts for mothers and 26.9% of prompts for children, fast food in 4.3% of prompts for mothers and 7.4% of prompts for children, chips/fries in 5.2% of prompts for mothers and 10.7% of prompts for children, and pastries/sweets in 7.8% of prompts for mothers and 14.9% of prompts for children. For children, within-subjects internal consistency reliabilities (ωs) were .90 (positive affect) and .86 (negative affect), and between-subjects ωs were .97 (positive affect) and .89 (negative affect). For mothers, within-subjects ωs were .70 (positive affect) and .82 (negative affect), and between-subjects ωs were .93 (positive affect) and .90 (negative affect).

Negative Affect and Food Intake

Results for APIMs examining between-subjects and within-subjects time-lagged associations between mothers’ and children’s negative affect and dietary intake behaviors are displayed in Table 2. In general, CIs for effects were wide with CI for between-subjects effects being wider than for within-subjects effects. For pastries/sweets, there were between-subjects actor effects for both dyad members such that mothers reporting more negative affect on average, compared to other mothers, consumed more pastries/sweets; and children reporting more negative affect on average, compared to other children, consumed more pastries/sweets. For fast food, there was a between-subjects actor effect for children only; children reporting more negative affect on average, compared to other children, consumed more fast food. Negative affect was unrelated to fruits/vegetables and chips/fries intake for mothers and children.

Table 2.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Models Examining Between- and Within-Subjects Time-Lagged Associations between Mother’s and Children’s Negative Affect and Food Intake

| Pastries/Sweets | Chips/Fries | Fast Food | Fruits/Vegetables | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | |||||||||

| Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Child | ||||||||||||||||

| WS NA | −.07 | −.29, .16 | .17 | −.10, .44 | .09 | −.17, .35 | .11 | −.23, .45 | −.15 | −.48, .19 | −.13 | −.50, .23 | −.08 | −.24, .08 | .02 | −.16, .21 |

| BS NA | 1.14* | .28, 2.00 | .33 | −.58, 1.25 | .88 | −.10, 1.87 | .21 | −.80, 1.21 | 1.06* | .26, 1.85 | .35 | −.39, 1.10 | .56 | −.33, 1.45 | −.16 | −.87, .55 |

| Mother | ||||||||||||||||

| WS NA | −.14 | −.41, .12 | −.23 | −.55, .10 | .01 | −.26, .28 | −.01 | −.36, .33 | .23 | −.10, .57 | −.05 | −.40, .29 | .09 | −.11, .29 | −.03 | −.23, .17 |

| BS NA | −.08 | −.87, .70 | 1.04* | .28, 1.80 | −.32 | −1.13, .50 | .31 | −.42, 1.04 | −.18 | −.92, .57 | .26 | −.38, .90 | −.19 | −1.01, .62 | −.30 | −.93, .33 |

Note. Child outcomes were adjusted for child sex, ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), and child’s missing data patterns; mother outcomes were adjusted for mother ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and mother’s missing data patterns; both mother and child outcomes were adjusted for household income. NA = negative affect; WS = within-subjects; BS = between subjects

p<.05

Ability to Cope with Stress and Food Intake

Results for APIMs examining between- and within-subjects time-lagged associations between mothers’ and children’s ability to cope with stress and food intake are displayed in Table 3. CIs for effects demonstrated a similar pattern as results for negative affect and food intake. For pastries/sweets, there were several significant within-subjects actor and partner effects. When mothers reported greater ability to cope with stress than their own average, they and their children were subsequently more likely to consume pastries/sweets (actor and partner effects). Also, when children reported greater ability to cope with stress than their own average, they were subsequently more likely to consume pastries/sweets (actor effect). For chips/fries, there was a within-subjects actor effect for mothers such that when mothers reported greater ability to cope with stress than their own average, they were subsequently more likely to consume chips/fries (actor effect). In addition, there was a between-subjects partner effect such that children reporting greater ability to cope with stress on average, compared to other children, had mothers who consumed more chips/fries. For fruits/vegetables, there was a between-subjects partner effect such that for those children reporting greater ability to cope with stress on average, compared to other children, their mothers consumed more fruit/vegetables on average.

Table 3.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Models Examining Between- and Within-Subjects Time-Lagged Associations between Mother’s and Children’s Ability to Cope with Stress and Food Intake

| Pastries/Sweets | Chips/Fries | Fast Food | Fruits/Vegetables | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | |||||||||

| Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Child | ||||||||||||||||

| WS Stress | .50* | .02, .99 | .43 | −.13, 1.00 | −.15 | −.62, .32 | −.53 | −1.15, .09 | .42 | −.14, .99 | .17 | −.46, .80 | .09 | −.23, .41 | −.06 | −.40, .28 |

| BS Stress | .50 | −1.01, 2.01 | .75 | −1.23, 2.73 | −.62 | −2.76, 1.53 | 1.65 | .05, 3.24 | −.60 | −1.70, .51 | −.27 | −1.79, 1.25 | .84 | .−.75, 2.43 | 1.22* | .28, 2.15 |

| Mother | ||||||||||||||||

| WS Stress | .23* | .03, .43 | .20* | .01, .39 | .02 | −.21, .26 | .47* | .19, .75 | .03 | −.21, .28 | .22 | −.09, .53 | .02 | −.13, .17 | .07 | .−.09, .23 |

| BS Stress | −.04 | −.40, .42 | −.45 | −.92, .02 | .14 | −.34, .61 | .12 | −.39, .63 | .23 | −.18, .63 | .08 | −.33, .48 | −.21 | −.67, .24 | .00 | −.31, .31 |

Note. Child outcomes were adjusted for child sex, ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), and child’s missing data patterns; mother outcomes were adjusted for mother ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and mother’s missing data patterns; both mother and child outcomes were adjusted for household income. WS = within-subjects; BS = between-subjects; Stress = ability to cope with stress.

p<.05

Positive Affect and Food Intake

Results for APIMs examining between- and within-subjects time-lagged associations between mothers’ and children’s positive affect and food intake are displayed in Table 4. In general, CIs were much more precise for within-subjects effects for positive affect compared to negative affect and ability to cope with stress. For fruits/vegetables, there was a within-subjects actor effect for mothers. When mothers reported more positive affect than their own average, they were subsequently more likely to consume fruit/vegetables. Positive affect was unrelated to pastries/sweets, fast food, and chips/fries intake for mothers and children.

Table 4.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Models Examining Between- and Within-Subjects Time-Lagged Associations between Mother’s and Children’s Positive Affect and Food Intake

| Pastries/Sweets | Chips/Fries | Fast Food | Fruits/Vegetables | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | Child | Mother | |||||||||

| Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Child | ||||||||||||||||

| WS PA | .07 | −.08, .21 | −.10 | −.26, .07 | .10 | −.07, 27 | −.15 | −.37, .06 | .19 | −.01, .38 | .13 | −.06, .33 | .03 | .−.09, .14 | −.06 | −.18, .05 |

| BS PA | .27 | −.15, .69 | .13 | −.24, .50 | .19 | −.24, .62 | .03 | −.35, .40 | .07 | −.31, .45 | −.10 | −.49, .29 | .41 | −.06, .87 | .14 | −.16, .43 |

| Mother | ||||||||||||||||

| WS PA | .12 | −.07, .31 | .09 | −.16, .33 | .04 | −.14, .23 | .02 | −.23, .26 | −.08 | −.35, .20 | .01 | −.29, .31 | −.04 | −.19, .11 | .19* | .03, .35 |

| BS PA | −.14 | −.64, .35 | −.37 | −.83, .10 | −.27 | −.77, .23 | −.05 | −.47, .36 | −.04 | −.49, .42 | −.13 | −.57, .31 | −.21 | −.70, .27 | .26 | −.09, .62 |

Note. Child outcomes were adjusted for child sex, ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), and child’s missing data patterns; mother outcomes were adjusted for mother ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and mother’s missing data patterns; both mother and child outcomes were adjusted for household income. PA = positive affect; WS = within subjects; BS = between subjects

p<.05

Discussion

Overall, analyses provided partial confirmation of hypotheses for between- and within-subjects actor and partner associations of affect and ability to cope with stress and food intake. There were no momentary, within-subjects lagged associations between negative affect and food intake. However, there were between-subjects associations between negative affect and food intake. Mothers who reported high negative affect also indicated having consumed more pastries/sweets, and children who reported more negative affect also indicated having consumed more pastries/sweets and fast food.

These between-subject findings are consistent with previous EMA and survey research showing that trait level of negative affect is positively associated with unhealthy eating and diet (Jeffers et al., 2018; O’Neil et al., 2014). It is possible that the observed between-subject associations are capturing increased negative affect after the consumption of unhealthy foods (Heron, Scott, Sliwinski, & Smyth, 2014). However, this direction of association was not directly tested in our current paper. Further, unhealthy eating may impact biological pathways underpinning negative affect including inflammation and brain chemistry such that diet impacts markers of inflammation and brain areas involved in brain development, which increases risk for negative affect (O’Neil et al., 2014). Finally, unmeasured/uncontrolled trait variables (e.g., low self-control) may account for the observed between-subjects associations. For example, negative affect has been shown to decrease individuals’ ability to engage in effortful self-control, which may result in engaging in unhealthy behaviors (Cyders & Smith, 2008).

When mothers and children were less able to cope with stress than their own average, they consumed more pastries/sweets, and mothers consumed more chips/fries as well. In line with the ego depletion model, individuals having greater difficulty coping with stress may be less able to exert self-control from eating unhealthy food, particularly palatable foods high in sugar and fat. A particularly novel finding stemming from these results was a partner effect, showing that when mothers were less able to cope with stress than average, their children were more likely to consume pastries/sweets.

Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski’s (2008) model of the home food environment proposes a number of micro-level factors (e.g., parenting practices, parental eating behavior, family eating patterns) that impact children’s dietary intake patterns. These may be impacted when demands on mothers are higher than usual. Consistently, Dunton et al (2015) theorized that parenting practices are an important mediator of the association between maternal stress and children’s weight-related behaviors. When mothers are less able to cope with stress, they may practice less effortful parenting including being more permissive or less watchful of their child’s eating, or they may prepare more unhealthy meals/snacks due to ease of preparation (Deater-Deckard, 1998; Friedman & Billick, 2015). Further, mothers may choose more unhealthy foods for themselves, which they then share with their child.

With regard to positive affect findings, when mothers reported more positive affect than their own average, they were more likely to consume fruits/vegetables. This finding is analogous to prior research in adults (White, Horwath, & Conner, 2013) and shows that positive affective states may bolster individuals’ ability to make healthy eating decisions in the moment. There were no between- or within-subjects actor effects for children. Other studies have found that the link between positive affect and fruit/vegetable intake does not extend to children (e.g. O’Reilly et al., 2015). The link between positive affect and fruit/vegetable intake may not develop until adolescence or adulthood. Parental factors (e.g., encouragement, modeling) may be important in creating the affective association between positive affect and fruit and vegetable intake. In addition, children may have less control over what types of food are available to them to consume.

There were some unexpected findings that were not hypothesized. We offer a possible interpretation for these findings that should be examined in future research. Children reporting more ability to cope with stress across the EMA period had mothers who consumed more fruit/vegetables and chips/fries. It is possible that mothers of these children consume a larger variety of foods themselves. Mothers who consume a variety of foods may be less likely to use controlling feeding practices (e.g., restricting food intake) towards their children, which are associated with negative child outcomes (Loth, MacLehose, Fulkerson, Crow, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2014). In turn, less use of controlling feeding practices may be associated with better overall psychological health in children including better coping ability.

CIs for effects for negative affect and ability to cope with stress were wide, suggesting that the size of effects are not particularly stable. There are a host of time-varying and time-invariant factors that may moderate associations among between- and within-subjects negative affect and ability to cope with stress and food intake. That is, at some moments and/or for some individuals, there may be a stronger or weaker association between negative affect and ability to cope with stress and subsequent food intake. The current sample was diverse with regard to demographic characteristics, including race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, which each are related to obesity risk (Arroyo-Johnson & Mincey, 2016; McLaren, 2007) and may moderate associations between negative affect and ability to cope with stress and food intake. Also, relations between affect,stress, and food intake may change depending on time-varying factors (e.g., being alone versus with others, being at home, activity).

The strengths of this study included alleviating several limitations of prior research by using real-time data capture methodology with mother-child dyads. EMA allowed us to examine the association between mothers’ and their children’s affective states and ability to cope with stress with food intake in a novel way by testing both actor and partner effects. Additionally, the availability of repeated measures for each participant allowed us to draw more nuanced conclusions than would not be possible without the use of EMA including disaggregation of between- and within-subjects effects.

However, there were several limitations worth noting as well. An inherent limitation in EMA research is that only a limited number of items can be used to assess constructs of interest in order to minimize participant burden. Therefore, in the current study, only a few number of items were used to measure affect and ability to cope with stress, which may not have fully captured the constructs of interest. Affect and stress can be conceptualized in a number of different ways. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1999) includes 60 different affect items divided into 11 sub-constructs. In addition, there are different ways stress can be conceptualized (e.g., perceived stress, stressful events, stress reactivity, stress coping). These other types of affective states and stress could be examined in relation to food intake in future EMA studies. Further, in this study “feeling stressed” was conceptualized as a form of negative affect; this decision was empirically supported by omega coefficients. However, future research should disentangle the effects of negative affect and stress.

Affect and ability to cope with stress items also differed slightly between mothers and children, which may have impacted the results. This was done to ensure that item content was age-appropriate, but may have had unintended consequences on relations between variables. Another limitation to the current study is that although we used EMA to measure intake of target food items, we did not assess portion size, and data was only collected for a limited number of food types. Despite our findings, younger children, who are often limited in their dietary intake options due to school and home food availability, are less able to cater their dietary intake to their affective demands. Unlike adults, children must rely on caregivers to supply many foods (Savage et al., 2007), and therefore they may not display as clear of a relationship between affective state and changes in subsequent dietary intake.

Children could not complete EMA recordings during the day on weekdays due to school, which resulted in missing part of the day on weekdays for mothers and children. As mentioned previously, food intake may have an impact on affect (Singh, 2014). Thus, more research is needed to understand the reciprocal nature of these constructs, and conducting a bidirectional analysis of the data will help to shed light on the nature of these associations. Finally, several exclusion criteria may have biased the sample. For example, mothers who worked much of the EMA monitoring period were excluded; although, these mothers may have had unique stressors and experiences that would be important to study in relation to food intake.

Overall, this study offers important theoretical and clinical contributions to the fields of behavioral nutrition and obesity prevention. The major theoretical contribution of the study included support for momentary ability to cope with stress as a driver of food intake in mothers and children. Further, the study findings can be used to inform novel interventions for diet intake behaviors in children and their mothers, which ultimately will be important for obesity prevention and intervention. For example, ecological momentary interventions (i.e., interventions delivered in individuals’ natural environments through mobile technology) should be developed to consider momentary feelings of stress; this may increase the efficacy of dietary interventions, which could lead to better obesity and weight loss outcomes. Specifically, health education information focused on stress management, healthy eating, and effective parenting could be delivered when individuals are experiencing momentary stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the University of Southern California Graduate School, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL119255) and the American Cancer Society (118283-MRSGT-10-012-01-CPPB).

References

- Adam TC, & Epel ES (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91, 449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer E, Pavela G, & Lavie CJ (2015). The inadmissibility of what we eat in America and NHANES dietary data in nutrition and obesity research and the scientific formulation of national dietary guidelines. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Johnson C, & Mincey KD (2016). Obesity epidemiology trends by race/ethnicity, gender, and education: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2012. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 45, 571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, & Fairclough DL (2014). Practical and statistical issues in missing data for longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 23, 440–459. doi: 10.1177/0962280213476378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, & Kenny DA (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, & Birch LL (2001). Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews, 2, 159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 314–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Liao Y, Dzubur E, Leventhal AM, Huh J, Gruenewald T, … & Intille S (2015). Investigating within-day and longitudinal effects of maternal stress on children’s physical activity, dietary intake, and body composition: Protocol for the MATCH study. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 43, 142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorikhin A, & Patrick VM (2010). Positive mood and resistance to temptation: The interfering influence of elevated arousal. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 698–711. doi: 10.1086/655665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, & Ogden CL (2016). Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA, 315, 2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E, & Billick SB (2015). Unintentional child neglect: Literature review and observational study. Psychiatric Quarterly, 86, 253–259. doi: 10.1007/s11126-014-9328-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof GJ, Preacher KJ, & Zyphur MJ (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19, 72–91. doi: 10.1037/a0032138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Engel SG, Durkin N, Beach HM, … & Peterson CB (2014). Ecological momentary assessment of eating episodes in obese adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76, 747–752. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Stacy AW, Shiffman S, Baraldi AN, MacKinnon DP, Lockhart G, … Reynolds KD (2013). Sweetened drink and snacking cues in adolescents. A study using ecological momentary assessment. Appetite, 67, 61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, & Chatzisarantis NL (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron KE, Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, & Smyth JM (2014). Eating behaviors and negative affect in college women’s everyday lives. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 853–859. doi: 10.1002/eat.22292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen AM (2001). An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11, 75–85. doi: 10.1207/S15327663JCP1102_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers AJ, Mason TB, & Benotsch E (2018). Psychological eating factors, affect, and ecological momentary assessed eating behaviors Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kelly SJ, Daniel M, Dal Grande E, & Taylor A (2011). Mental ill-health across the continuum of body mass index. BMC Public Health, 11, 765. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Fulkerson JA, Crow S, & Neumark‐Sztainer D (2014). Are food restriction and pressure-to-eat parenting practices associated with adolescent disordered eating behaviors? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 310–314. doi: 10.1002/eat.22189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macht M (2008). How emotions affect eating: a five-way model. Appetite, 50, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabir S, Willett WC, Friedenreich CM, Lai GY, Boushey CJ, Matthews CE, … & Patel AV (2018). Research strategies for nutritional and physical activity epidemiology and cancer prevention. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 27, 233–244. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren L (2007). Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiologic Reviewithin-subjects, 29, 29–48. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher-Eizenman D, & Holub S (2007). Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: Validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 960–972. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén K, & Muthén BO (2015). Mplus User’s Guide, Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ng DM, & Jeffery RW (2003). Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychology, 22, 638–642. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SG, Ke W, Dzubur E, Schembre S, & Dunton GF (2018). Concordance and predictors of concordance of children’s dietary intake as reported via Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) and 24-hour recall. Public Health Nutrition doi: 10.1017/S1368980017003780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SG, Maher JP, Belcher BR, Leventhal AM, Margolin G, Shonkoff ET, & Dunton GF (2017). Associations of maternal stress with children’s weight-related behaviours: A systematic literature review. Obesity Reviews, 18, 514–525. doi: 10.1111/obr.12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil A, Quirk SE, Housden S, Brennan SL, Williams LJ, Pasco JA, … & Jacka FN (2014). Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e31–e42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly GA, Huh J, Schembre SM, Tate EB, Pentz MA, & Dunton G (2015). Association of usual self-reported dietary intake with ecological momentary measures of affective and physical feeling states in children. Appetite, 92, 314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, & Flegal KM (2010). Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA, 303, 242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J & Herman CP (1993). Etiology of binge eating: Psychological mechanisms. In Fairburn CG & Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment (pp. 173–205). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Posner J, Russell JA, & Peterson BS (2005). The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 715–734. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, & Zhang Z (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reedy J, & Krebs-Smith SM (2010). Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110, 1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R (2008). Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: A systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obesity Reviews, 9, 535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz RR, & Dzewaltowski DA (2008). Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutrition Reviews, 66, 123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage JS, Fisher JO, & Birch LL (2007). Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 35, 22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone A. a, & Hufford MR (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M (2014). Mood, food, and obesity. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Morenga L, Mallard S, & Mann J (2013). Dietary sugars and body weight: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ, 346, e7492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Cheney MM, & Chan N (2003). Exploring comfort food preferences across age and gender. Physiology and Behavior, 79, 739–747. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00203-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters SF, West TV, Karnilowicz HR, & Mendes WB (2017). Affect contagion between mothers and infants: Examining valence and touch. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146, 1043–1051. doi: 10.1037/xge0000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form Univesity of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, & Sato AF (2014). Stress and paediatric obesity: What we know and where to go. Stress and Health, 30, 91–102. doi: 10.1002/smi.2501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BA, Horwath CC, & Conner TS (2013). Many apples a day keep the blues away–Daily experiences of negative and positive affect and food consumption in young adults. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18, 782–798. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavorsky JE, Kamp Dush CM, & Schoppe-Sullivan SJ (2015). The production of inequality: The gender division of labor across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 662–679. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellner DA, Loaiza S, Gonzalez Z, Pita J, Morales J, Pecora D, & Wolf A (2006). Food selection changes under stress. Physiology & Behavior, 87, 789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]