Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the major epidemic of the 21st century, its prevalence rising along with improved human longevity. Early AD diagnosis is key to successful treatment, as currently available therapeutics only allow small benefits for diagnosed AD patients. By contrast, future therapeutics, including those already in preclinical or clinical trials, are expected to afford neuroprotection prior to widespread brain damage and dementia. Brain imaging technologies are developing as promising tools for early AD diagnostics, yet their high cost limits their utility for screening at-risk populations. Blood or plasma transcriptomics, proteomics, and/or metabolomics may pave the way for cost-effective AD risk screening in middle-aged individuals years ahead of cognitive decline. This notion is exemplified by data mining of blood transcriptomics from a published dataset. Consortia blood sample collection and analysis from large cohorts with mild cognitive impairment followed longitudinally for their cognitive state would allow the development of a reliable and inexpensive early AD screening tool.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, bioinformatics, mild cognitive impairment, proteomics, transcriptomics

Abstract

La Enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) es la principal epidemia del siglo XXI y su prevalencia está aumentando con el incremento de la longevidad humana. El diagnóstico precoz de la EA es clave para un tratamiento exitoso, ya que las terapias actualmente disponibles sólo permiten pequeños beneficios para los pacientes diagnosticados con EA. Al contrario, se espera que las futuras terapias, incluyendo las que ya están en ensayos preclínicos o clínicos, proporcionen una neuroprotección previo al daño cerebral generalizado y demencia. Las tecnologías de imágenes cerebrales se están desarrollando como prometedoras herramientas para diagnósticos precoces de la EA, aunque todavía su alto costo limita su empleo como evaluación en poblaciones en riesgo. La transcriptómica, proteómica ylo metabolómica sanguínea o plasmática pueden abrir la vía para una evaluación económica del riesgo de EA en individuos de edad media años antes del deterioro cognitivo. Este concepto está ilustrado por la explotación de datos de transcriptomas sanguíneos provenientes de una base de datos publicada. Un consorcio de recolección de muestras sanguíneas y de análisis de grandes cohortes con deterioro cognitivo leve, seguidas longitudinalmente en su estado cognitivo podría permitir el desarrollo de una herramienta de evaluación precoz de la EA que sea confiable y de bajo costo.

Abstract

La prévalence de la maladie d'Alzheimer (MA), épidémie principale du XXIe siècle, augmente avec l'augmentation de l'espérance de vie. Les traitements actuellement disponibles n'apportant que de faibles bénéfices pour les patients atteints, un diagnostic précoce de la maladie est essentiel pour la traiter efficacement. A l'avenir, les traitements (y compris ceux déjà en essais cliniques ou précliniques) devront assurer une protection neuronale avant même l'apparition de lésions cérébrales étendues et de signes de démence. Les techniques d'imagerie cérébrale sont des outils prometteurs pour le diagnostic précoce de MA mais leur coût élevé limite leur utilisation pour le dépistage des populations à risque. La métabolomique, la protéomique et/ou la transcritomique sanguines ou plasmatiques peuvent ouvrir la voie d'un dépistage à moindre coût du risque de MA chez des sujets d'âge moyen, des années avant le déclin cognitif. L'exploitation des données de transcriptomes sanguins à partir d'une base de données publiées, en est l'illustration. Un consortium de recueil d'échantillons sanguins et d'analyses à partir de grandes cohortes de sujets atteints de troubles cognitifs légers dont l'état cognitif est suivi longitudinalement permettra le développement d'un outil de dépistage précoce de la MA fiable et peu coûteux.

Early detection of sporadic Alzheimer disease is crucial for successful therapy

Cardiovascular diseases and cancer are currently the major cause of death among the elderly in developed countries. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) projects that by 2050, old-age dementia, most notably as result of sporadic (late-onset) Alzheimer disease (AD), will triple compared with current rates and become the major cause of death in developed as well as in low and middle-income countries.1 According to the WHO report (updated on December 2017),1 there are presently 50 million patients with dementia worldwide, with 10 million new cases diagnosed each year, and up to 70% of these diagnosed with AD. Indeed, while there are many different forms of dementia, AD is the most common one and contributes to 60% to 70% of all dementia cases. These numbers are projected to increase to 152 million by 2050, due mostly to increased life expectancies in middle- and low-income countries. Accordingly, the global societal cost is estimated to nearly triple from US$818 billion in 2015 to over US$2 trillion already by 2030.1 The current societal cost already represents 1.1% of global gross domestic product (GDP); this monetary burden is higher, on average 1.4% of the local GDP, in developed countries. For example, a recent study from France calculated annual costs of nearly €30,000 for the care of patients with advanced AD.2 Extrapolating this cost for the 152 million AD patients projected by 2050, the global cost could become as high as US$5 trillion, which represents 7% of current global GDP (though costs in low-income countries may be lower). In any scenario, future societal costs for treating AD patients represent a worrying burden for the global economy. The only sensible solution to this worrying trend would be the development of therapeutics for very early disease stages, along with affordable diagnostics for AD risk detection among middle-aged individuals and population-wide screening programs, so that the progress of dementia may be addressed (and ideally halted) prior to dementia onset.

Current first-line AD therapeutics include acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and glutamate signaling ligands, and are at best capable of slowing the progress of dementia. Their low therapeutic capacity reflects the fact that once an individual is diagnosed with AD the brain damage is already too extensive for such drugs to repair the widespread impairment.3,4 Many tentative AD therapeutics are still in various stages of preclinical or clinical development.5,6 It is hoped that such future “disease-modifying therapeutics” would exhibit improved efficacy in slowing brain neurodegeneration, provided that they are prescribed early on, that is, well before severe brain damage has taken place. Prospective disease-modifying therapeutics include neurotrophic factors or their synthetic mimetics and agents capable of reducing neuroinflammation or allowing clearance of soluble amyloid-β so that its aggregation and subsequent brain accumulation are drastically reduced. At this time most such tentative AD therapeutics are in early stages of development; their approval and marketing may take many years.7,8 Moreover, it has been suggested that AD may represent a disorder rather than a single distinct disease, reflecting metabolic, developmental, or cardiovascular deficits.9-11 Hence, once a larger selection of disease-modifying therapeutics become available, hopefully before 2030, successful treatment may require patient stratification according to AD subtypes for prescribing precision medicine therapeutics according to each patient's symptoms, demographics, identified insufficiencies, and comorbidities. In this manner, precision medicine for AD patients would be prescribed similarly to the already practiced successful application of biomarker-dependent precision medicine in oncology.12,13

In this commentary we suggest that identifying diagnostic biomarkers based on blood or plasma transcriptomes, proteomes, and/or metabolomes may provide the best approach for both enabling cost-effective population-wide screening for individuals at high risk to develop late-onset dementia, as well as enhancing precision medicine for such individuals prior to onset of dementia.14-16

Early Alzheimer disease diagnosis by imaging technologies

Precision medicine in oncology is typically based on DNA, RNA, and protein biomarkers detected in biopsied tumor tissues; brain biopsies are obviously not an option for CNS disorders, including neurodegenerative disorders. Thus, research on early detection of AD has focused over the past two decades on brain-imaging technologies. This topic has been extensively reviewed; see for example recent reviews on functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) imaging by Topiwala et al17 and on positron emission tomography (PET) imaging by Fantoni et al18 and by Shea et al.19 In addition to brain imaging, studies on early detection biomarkers for sporadic AD are ongoing with retinal20 and vascular imaging.21 Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples are also extensively studied as suitable biofluid for early detection of sporadic AD, in particular with protein studies on CSF amyloid-β and tau.22-25 Yet, while brain imaging tools and CSF protein analysis offer hopes for improved early AD detection, their high costs (brain imaging) and health risks (CSF sampling) prohibit their use as a population-wide screening tool. By comparison, we estimate that testing an individual for her AD risk with genomic biomarkers would cost around 500 euros. Fees for such tests will likely keep decreasing in 5 to 10 years due to reduced costs of DNA and RNA sequencing technologies.

DNA vs RNA biomarkers for early Alzheimer disease detection

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) examining the presence of common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DNA samples from unrelated individuals by using microarray technologies have dominated the search for disease risk and phenotype-associated alleles for two decades.26-28 Over the last decade, along with decreasing costs of next-generation whole genome DNA-sequencing technologies, human DNA studies have been moving from microarray-based to DNA-sequencing technologies, that yield far higher coverage of an individual's genome sequence. DNA-sequencing informs not only on the presence of common SNPs but also on rare SNPs, as well as on the presence of short insertions, deletions, duplications, and rearrangements in a donor's DNA sequence.29 Early SNP-based microarrays for human DNA studies typically examined over half-million SNPs. Next-generation whole genome DNA-sequencing (WGS) may examine nearly the entire 3.2 billion nucleotides of the human DNA sequence. Given the large DNA sequence heterogeneity among humans, such huge amounts of data mean that very large cohorts are required for deriving statistically meaningful findings about associations between disease and DNA alleles. Thus, cohorts of tens of thousands of patients along with matched controls have become the norm rather than the exception for identifying disease risk genotypes or phenome-genome associations. Indeed, recently published GWAS have featured 46 939 patients and 27 910 controls for identifying prostate cancer risk alleles30; 449 484 individuals for identifying genetic loci associated with neuroticism31; 269 867 individuals for identifying loci linked to intelligence32; 60 720 patients along with 618 527 controls for identifying allergic rhinitis risk lock33; and 498 134 individuals for a UK Biobank study on the effects of coffee drinking on mortality.34 Studying such extremely large cohorts demonstrates the utility of the GWAS approach, but at the same time, also the need for collecting samples from very large cohorts, a scheme requiring large research consortia. Such consortia illustrate the way forward for advancing genomic medicine and future precision medicine research for complex disorders. However, one must bear in mind that the power afforded by such large GWAS consortia highly depends on accurate patient phenotyping, which becomes more problematic when research teams include a large number of participating medical centers, that, when located in countries where divergent diagnostic criteria are applied, may add noise to the project's data. Such concerns have been raised for example in the context of establishing pharmacogenomic biomarkers for precision medicine35,36 and seem to be highly relevant for sporadic (late-onset) AD risk detection.

The research of sporadic AD has also benefited from GWAS studies. In 2007, a GWAS study of 1086 sporadic AD patients and controls37 verified the already established status of APOE as the major risk gene for sporadic AD, with the presence of the SNP rs4420638 near APOE yielding odds-risk ratio of 4.01 with a Bonferroni corrected P-value=5.3x10-.34 To our knowledge, this P-value remains the smallest reported to date with similarly sized patient cohorts of multigenic disorders. Further sporadic AD GWAS have so far identified major risk alleles in about 30 additional genes, some still requiring validation by larger cohort studies.16 The largest sporadic AD study to date was published by the Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project in May 201838 and featured exome sequencing of 6965 sporadic AD patients and 13 252 controls. The only gene attaining genome-wide level statistical significance (besides APOE) was SORL1 (sortilin related receptor 1), encoding a preproprotein that, following proteolytic processing, generates a receptor that likely plays a role in protein endocytosis and sorting, possibly affecting the clearance of extracellular amyloid-β.39 This finding awaits an independent validation.

However, these extensive GWAS and exome-sequencing research projects have not yet been (and in our opinion are not likely to be) translated into population-wide programs for sporadic AD risk screening. The reasons are diverse and mirror the insufficient sensitivity and specificity of data derived from DNA genotyping or sequencing alone for AD risk determination. This in turn reflects that besides DNA sequence, an individual's non-genetic factors, including lifestyle, level of education, diet, gut microbiome, comorbidities, and other external exposures contribute to the risk of acquiring sporadic AD.40,41 Such non-genetic factors may or may not be reflected by an individual's epigenome, the collective term for non-inherited DNA modifications, which have been extensively studied also in the context of AD risk prediction.42,43

In contrast with DNA genotyping or sequencing, transcriptomics, the study of gene expression profiles at the level of RNA (including also the transcribed RNA of noncoding genes, microRNAs and long-noncoding RNAs), informs not only about inherited but also, albeit indirectly, about noninherited genomic information.44,45 As such, transcriptomic studies also capture genomic information affected by individuals' environmental exposures and comorbidities; these may in part be relevant for risks of acquiring complex diseases, including sporadic AD. Thus transcriptomics appear to potentially be more informative compared with DNA genotyping or DNA sequencing for developing diagnostic tools for complex disorders, including sporadic AD.46,47 An additional advantage is derived from improved statistical power: transcriptomic technologies examine the expression levels of up to 20 000 human genes in given biological samples, that is, at least 1000-fold fewer variables are being measured compared with GWAS or DNA sequencing studies; this in turn allows more power and thus smaller cohorts.48,49 Deep sequencing may in addition detect up to twice as many long-noncoding RNAs (1ncRNAs), though the functions of most of them remain enigmatic.

It is important to keep in mind that applying RNA as early AD risk biomarkers, as well as in the context of other diseases, has its limitations: the transcriptome is highly dynamic50 and highly cell-specific51; hence RNA findings in peripheral tissues should be taken with caution, and require support by additional diagnostic tools. Moreover, mRNA levels may not faithfully reflect the corresponding protein level.52 Hence, studies are required for validation of tentative RNA biomarkers reported by transcriptomic studies with postmortem brain tissues or blood samples.

In addition to blood, saliva samples are also a likely source for early diagnosis of AD. In recent years, several notable findings in salivary samples have been reported that await confirmation in larger AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cohorts. These studies include measurements of salivary lactoferrin,53 amyloid-β,54,55 and tau.56 However, salivary tau was found unsuitable as an AD or MCI biomarker in a recent larger cohort.57 To our knowledge, no studies (as of July 2018) have reported on tentative salivary-based RNA biomarkers for AD or MCI.

As noted above, a key problem with early AD diagnostics is that the brain tissue is inaccessible for biopsy sampling, while CSF collection is not a valid option for population-wide screening; which leaves blood or saliva as the most likely optional biosamples. Blood samples have extensively been employed for searching early AD biomarkers, in particular proteomic and metabolomic biomarkers, topics beyond the scope of this article. Readers are referred to fine recent reviews on protein58-61 and metabolome62 early AD biomarkers. A roadmap for developing a blood test for early AD detection was recently proposed by Kiddle et al;61 these authors outline a plan focused on changing research approach concepts from small studies to large multicenter consortia efforts and improved data sharing between research teams, a notion with which we strongly concur as the best way forward. Below, for demonstrating the untapped potential for discovering early AD biomarkers by studying blood transcriptomic signatures from large cohorts of MCI and AD patients, we provide a demonstrative example based on data mining of a single blood gene expression dataset.

MCI peripheral blood data mining example as proof of concept

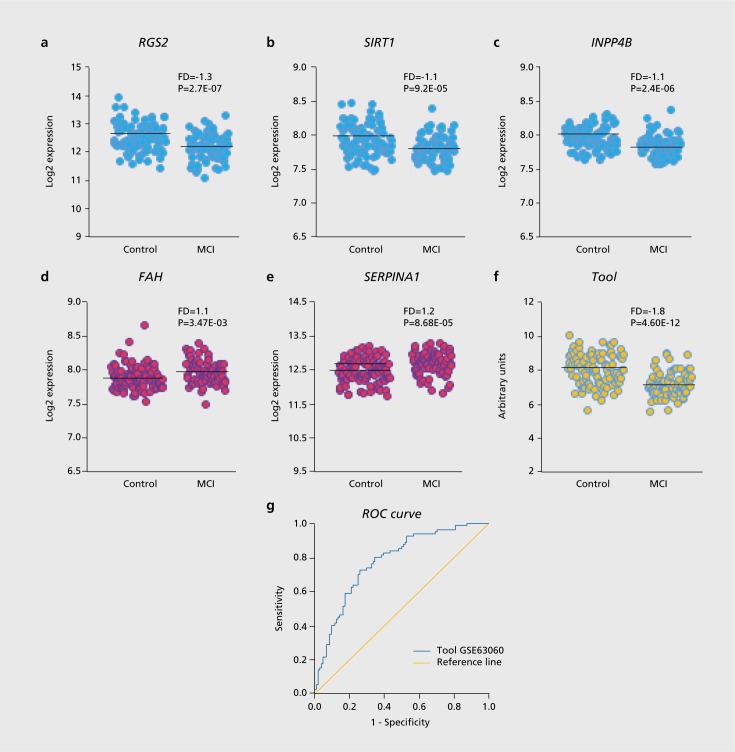

Data mining of existing blood transcriptomics datasets was performed on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/) on dataset GSE63060 (contributed by Sood et al 2015)63 using the GE02R software tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). This tool allows comparison of groups of samples whose transcriptomics datasets have been deposited on the GEO server in order to identify genes that are differentially expressed between groups of samples. We applied this tool on dataset GSE6306063 for comparing sets of candidate genes; we chose four genes reported as having differential expression in blood derived cell lines based on amyloid-β sensitivity or when comparing cell lines from AD patients and controls: RGS2, SIRT1, INPP4B, and FAH. 64,65 To this list we added a fifth gene, SERPINA1, based on the suggestion of higher serum alpha-1-antitrypsin protein as a tentative AD biomarker by Wetterling and Tegtmeyer, 1994.66 Next, the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve67 was applied for analyzing the blood expression levels of the above genes as a tentative MCI prediction tool, based on the candidate genes. ROC curves demonstrate the diagnostic capacity of classifiers as their discrimination thresholds are varied. In the context of diagnostic biomarkers, they allow the estimation of the classifier accuracy, by showing the relationships between clinical sensitivity and specificity for group differences. In a given ROC curve, the x-axis shows 1 minus specificity (false positive) fraction and the y-axis shows sensitivity (true positive) fraction. Additionally, the area under the curve (AUC) of a ROC curve of a given test can be used as a measure for its discriminative capacity. As shown in Figure 1, while each of the five genes showed a fold-difference (FD) of between 1.1 and 1.3 between MCI and nondemented controls (with significance values P=3.47E-03 and P=2.7E-07), our tentative 5-gene tool showed a superior separation between MCI and controls: FD=1. 8 and P=4.60E-12. As shown in Table I, ROC curve analysis applied on the transcriptomic dataset GSE63060, which shows gene expression levels in blood samples from AD patients (n=145), MCI patients (n=80), and nondemented age-matched controls (n=104) indicated that our tentative 5-gene tool identified MCI patients vs controls with an AUC=0.777 and P=1.20E-10. Applying the same tool on the AD patients vs controls in the same GSE63060 dataset identified AD patients with AUC=0.683 and P=8.8E-7. Less robust AUC and P-values were found for applying the same tool on GSE63061 by the same authors,63 which shows gene expression levels in blood samples from AD patients (n=139), MCI patients (n=109) and non-demented controls (n=134). Of note, in both the latter GEO datasets, ROC curve analysis of our proposed 5-gene tool indicated more robust identification of MCI patients compared with AD patients (each compared with nondemented age-matched controls). This observation suggests that our proposed tool is likely more adequate for correctly classifying MCI than AD patients. We identified two further GSE files containing transcriptomic data from at least 40 individuals, GSE85426 and GSE4229.68 However, these two files, unlike GSE63060 and GSE63061, include data derived from RNA of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) rather than whole blood, do not include MCI patients, and have considerably fewer samples (these datasets are from 90 and 18 AD patients and 90 and 22 nondemented controls, respectively). Indeed, ROC curves for the latter two datasets indicated that our example 5-gene prediction tool could not distinguish between AD patients and controls. Therefore, we cannot conclude about the plausible MCI or AD biomarker utility of transcriptomics of whole blood biosamples compared with PBMC, nor about the value of transcriptomics for identifying MCI compared with AD patients. The reasons are, unfortunately, the miniscule number of such GEO datasets currently available for bioinformatics analysis. This clearly demonstrates the need for further blood transcriptomic studies with larger MCI and AD cohorts, as well as the unmet need for open data sharing from such studies.

Figure 1. Whole blood expression levels for selected genes in 80 MCI and 104 healthy controls from dataset GSE63060 and an example MCI prediction tool. Distribution, FD and P-values for MCI vs control expression levels are shown for: (a) RGS2; (b) SIRT1; (c) INPP4B; (d) FAH; (e) SERPINA1; (f) the sum expression levels of RGS2, SIRT1 , and INPP4B minus the sum expression levels of FAH and SERPINA1. Two-tail T-test was applied for testing Equality of Means; (g) ROC curve representing a positive actual state for MCI. Smaller values indicate stronger evidence for the positive actual state. AUC=0.777±0.034, P=1.20E-10; Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval: Lower bound=0.710 and Upper bound=0.844. The ROC curve of the Tool has higher AUC compared with each of the genes by itself. For statistical analyses, SPSS 23 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. AUC: area under the curve; ROC: receiver operating characteristics. See main text for further details.

Looking ahead

The peripheral blood GSE63060 data mining example based on the expression of five candidate genes presented in Figure 1 is definitely inadequate for serving as early diagnostics for sporadic AD detection. We present it merely to illuminate the potential of transcriptomic data mining in discovering early sporadic AD biomarkers that may, in future, be utilized for population-wide screening. Table I demonstrates that at this time, our illustrative example lacks validation owing to the lack of sufficiently large open GEO datasets from MCI patients. GSE63060 includes transcriptomic data from merely 80 MCI and 104 matched nondemented individuals; as discussed above, much larger cohorts (at least several hundreds of individuals) would be needed for developing prediction tools for sporadic AD with robust specificity and sensitivity. For example, a recent transcriptomewide association study included breast tissue RNA from 229 000 women (122 977 cases and 105 974 controls) for identifying new candidate susceptibility genes for breast cancer.69 Having large cohort datasets openly shared on the GEO website would allow the application of machine learning tools70,71 for devising a reliable and affordable diagnostics tools for AD as well as other disorders of old age. Ideally, such datasets should incorporate blood transcriptomics (or microRNA profiling of plasma or serum) along with proteomic and metabolomic data.72,73 In addition, efforts must include the collection of longitudinal blood samples as well as of longitudinal cognitive score data, along the successful UK Biobank approach. With increased projected human longevity, and the expected approval and marketing of disease modifying therapeutics for neurodegenerative disorders, investing in such studies and making their data openly available seems to be the best way forward.

AUC and P-values derived from GEO datasets following ROC curve analysis by the 5-gene example tool presented in Figure 1.

| GSE# | Reference | RNA source | MCI | AD | Control | AUC (MCI vs control) | AUC (AD vs control) | Comments |

| GSE63060 | 63 | whole blood | 80 | 145 | 104 | AUC=0.777 | AUC=0.683 | |

| P=1.20E-10 | P=8.8E-7 | |||||||

| GSE63061 | 63 | whole blood | 109 | 139 | 134 | AUC=0.638 | AUC=0.627 | |

| P=2.2E-4 | P=2.7E-4 | |||||||

| GSE85426 | NA | PBMC | 0 | 90 | 90 | NA | AUC=0.472 | No INPP4B probe |

| P=0.524 | ||||||||

| GSE4229 | 68 | PBMC | 0 | 18 | 22 | NA | AUC=0.500 | No SIRT1 probe |

| P=1.000 |

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Adva Hadar, Department of Human Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry, Sackler Faculty of Medicine.

David Gurwitz, Department of Human Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry, Sackler Faculty of Medicine; Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 69978 Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization - Dementia. 12 December 2017; http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapp T., Andrieu S., Chartier F., et al. Resource use and cost of Alzheimer's disease in France: 18-month results from the GERAS Observational Study. Value Health. 2018;21(3):295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frozza RL., Lourenco MV., De Felice FG. Challenges for Alzheimer's disease therapy: insights from novel mechanisms beyond memory defects. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:37. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampel H., Mesulam MM., Cuello AC., et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141(7):1917–1933. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings J., Lee G., Ritter A., Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2018. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:195–214. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vina J., Sanz-Ros J. Alzheimer's disease: only prevention makes sense. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;40(10):e13005. doi: 10.1111/eci.13005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn JF. Lost in translation? Finding our way to effective Alzheimer's disease therapies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(s1):S33–s39. doi: 10.3233/JAD-179930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baazaoui N., Iqbal K. A novel therapeutic approach to treat Alzheimer's Disease by neurotrophic support during the period of synaptic compensation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):1211–1218. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J., Begley P., Church SJ., et al. Graded perturbations of metabolism in multiple regions of human brain in Alzheimer's disease: Snapshot of a pervasive metabolic disorder. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862(6):1084–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendt T., Stieler J., Ueberham U. Is sporadic Alzheimer's disease a developmental disorder? J Neurochem. 2017;143(4):396–408. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iturria-Medina Y., Hachinski V., Evans AC. The vascular facet of late-onset Alzheimer's disease: an essential factor in a complex multifactorial disorder. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30(6):623–629. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampel H., O'Bryant SE., Castrillo Jl., et al. PRECISION MEDICINE - The Golden Gate for Detection, Treatment and Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3(4):243–259. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hampel H., Vergallo A., Aguilar LF., et al. Precision pharmacology for Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Res. 2018;130:331–365. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisoni GB., Boccardi M., Barkhof F., et al. Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease based on biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(8):661–676. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiba-Falek O., Lutz MW. Towards precision medicine in Alzheimer's disease: deciphering genetic data to establish informative biomarkers. Expert Rev Precis Med Drug Dev. 2017;2(1):47–55. doi: 10.1080/23808993.2017.1286227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freudenberg-Hua Y., Li W., Davies P. The role of genetics in advancing precision medicine for Alzheimer's disease-a narrative review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:108. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topiwala H., Terrera GM., Stirland L., et al. Lifestyle and neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on functional magnetic resonance imaging: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fantoni ER., Chalkidou A., JT OB., Farrar G., Hammers A. A systematic review and aggregated analysis on the impact of amyloid PET brain imaging on the diagnosis, diagnostic confidence, and management of patients being evaluated for Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(2):783–796. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shea YF., Barker W., Greig-Gusto MT., Loewenstein DA., Duara R., DeKosky ST. Impact of amyloid PET imaging in the memory clinic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(1):323–335. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao H., Zhu Z., Peng Y. Potential utility of retinal imaging for Alzheimer's Disease: a review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:188. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Head E., Powell DK., Schmitt FA. Metabolic and vascular imaging biomarkers in down syndrome provide unique insights into brain aging and Alzheimer Disease pathogenesis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:191. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie C., Smailagic N., Noel-Storr AH., Ukoumunne O., Ladds EC., Martin S. CSF tau and the CSF tau/ABeta ratio for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:Cd010803. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010803.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duits FH., Brinkmalm G., Teunissen CE., et al. Synaptic proteins in CSF as potential novel biomarkers for prognosis in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0335-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansson O., Seibyl J., Stomrud E., et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease concord with amyloid-beta PET and predict clinical progression: a study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2018. pii: S1552-5260(18)30029-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer P., Lang R., Oberstein TJ., et aI. A specific reduction in Aβ1-42 vs. a universal loss of Aβ peptides in CSF differentiates Alzheimer's disease from meningitis and multiple sclerosis. Front Aging Neuroscience. 2018;10:152. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dehghan A. Genome-wide association studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1793:37–49. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7868-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie MD., Van Steen K. The search for gene-gene interactions in genome-wide association studies: challenges in abundance of methods, practical considerations, and biological interpretation. Ann Translat Med. 2018;6(8):157. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdmann J., Kessler T., Munoz Venegas L., Schunkert H. A decade of genome-wide association studies for coronary artery disease: the challenges ahead. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114(9):1241–1257. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DePristo MA., Banks E., Poplin R., et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher FR., Al Olama AA., Berndt SI., et al. Association analyses of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):928–936. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0142-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagel M., Jansen PR., Stringer S., et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):920–927. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage JE., Jansen PR., Stringer S., et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):912–919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waage J., Standi M., Curtin JA., et al. Genome-wide association and HLA fine-mapping studies identify risk loci and genetic pathways underlying allergic rhinitis. Nat Genet. 2018;50(8):1072–1080. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loftfield E., Cornelis MC., Caporaso N., Yu K., Sinha R., Freedman N. Association of coffee drinking with mortality by genetic variation in caffeine metabolism: findings from the UK biobank. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1086–1097. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurwitz D., Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenomics: the importance of accurate phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11(4):469–470. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosslin DR., Robertson PD., Carrell DS., et al. Prospective participant selection and ranking to maximize actionable pharmacogenetic variants and discovery in the eMERGE Network. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0181-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coon KD., Myers AJ., Craig DW., et al. A high-density whole-genome association study reveals that APOE is the major susceptibility gene for sporadic late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(4):613–618. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raghavan NS., Brickman AM., Andrews H., et al. Whole-exome sequencing in 20,197 persons for rare variants in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(7):832–842. doi: 10.1002/acn3.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felsky D., Xu J., Chibnik LB., et al. Genetic epistasis regulates amyloid deposition in resilient aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(10):1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang T., Yu J-T., Tian Y., Tan L. Epidemiology and etiology of Alzheimer's disease: from genetic to non-genetic factors. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10(8):852–867. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato N., Morishita R. Roles of vascular and metabolic components in cognitive dysfunction of Alzheimer disease: short- and long-term modification by non-genetic risk factors. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:64. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenoglio C., Scarpini E., Serpente M., Galimberti D. Role of genetics and epigenetics in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):913–932. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berson A., Nativio R., Berger SL., Bonini NM. Epigenetic regulation in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2018;41(9):587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jung S., Angarica VE., Andrade-Navarro MA., Buckley NJ., Del Sol A. Prediction of chromatin accessibility in gene-regulatory regions from transcriptomics data. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4660. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04929-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raghavachari N., Garcia-Reyero N. Overview of gene expression analysis: transcriptomics. In: Gene Expression Analysis. New York, NY: Springer Nature; 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7834-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charlesworth JC., Peralta JM., Drigalenko E., et al. Toward the identification of causal genes in complex diseases: a gene-centric joint test of significance combining genomic and transcriptomic data. BMC Proc. 2009;3 Suppl 7:S92. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s7-s92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todd EV., Black MA., Gemmell NJ. The power and promise of RNA-seq in ecology and evolution. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(6):1224–1241. doi: 10.1111/mec.13526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gurwitz D. Expression profiling: a cost-effective biomarker discovery tool for the personal genome era. Genome Med. 2013;5(5):41. doi: 10.1186/gm445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gurwitz D. From transcriptomics to biological networks. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(5):267–270. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colantuoni C., Lipska BK., Ye T., et al. Temporal dynamics and genetic control of transcription in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478(7370):519. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darmanis S., Sloan SA., Zhang Y., et al. A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(23):7285–7290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507125112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szavits-Nossan J., Ciandrini L., Romano MC. Deciphering mRNA sequence determinants of protein production rate. Phys Rev Lett. 2018;120(12):128101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.128101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carro E., Bartolome F., Bermejo-Pareja F., et al. Early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease based on salivary lactoferrin. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bermejo-Pareja F., Antequera D., Vargas T., Molina JA., Carro E. Saliva levels of Abeta1-42 as potential biomarker of Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee M., Guo JP., Kennedy K., McGeer EG., McGeer PL. A method for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease based on salivary amyloid-beta protein 42 levels. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(3):1175–1182. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi M., Sui YT., Peskind ER., et al. Salivary tau species are potential biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27(2):299–305. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ashton NJ., Ide M., Scholl M., et al. No association of salivary total tau concentration with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;70:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan AT., Dobson RJ., Sattlecker M., Kiddle SJ. Alzheimer's disease: are blood and brain markers related? A systematic review. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(6):455–462. doi: 10.1002/acn3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blennow K. A review of fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease: moving from CSF to blood. Neurol Ther. 2017;6(Suppl 1):15–24. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Du Y., Wu HT., Qin XY., et al. Postmortem brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood neurotrophic factor levels in Alzheimer's Disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Mol Neurosci. 2018;65(3):289–300. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kiddle SJ., Voyle N., Dobson RJB. A blood test for Alzheimer's Disease: progress, challenges, and recommendations. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(s1):S289–s297. doi: 10.3233/JAD-179904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Leeuw FA., Peeters CFW., Kester Ml., et al. Blood-based metabolic signatures in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sood S., Gallagher IJ., Lunnon K., et al. A novel multi-tissue RNA diagnostic of healthy ageing relates to cognitive health status. Genome Biol. 2015;16:185. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0750-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadar A., Milanesi E., Squassina A., et al. RGS2 expression predicts amyloid-β sensitivity, MCI and Alzheimer's disease: genome-wide transcriptomic profiling and bioinformatics data mining. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(10):e909. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hadar A., Milanesi E., Walczak M., et al. SIRT1, miR-132 and miR-212 link human longevity to Alzheimer's Disease. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):8465. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wetterling T., Tegtmeyer KF. Serum alpha 1-antitrypsin and alpha 2-macroglobulin in Alzheimer's and Binswanger's disease. Clin Investig. 1994;72(3):196–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00189310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gerszten RE., Wang TJ. The search for new cardiovascular biomarkers. Nature. 2008;451(7181):949–952. doi: 10.1038/nature06802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maes OC., Schipper HM., Chertkow HM., Wang E. Methodology for discovery of Alzheimer's disease blood-based biomarkers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(6):636–645. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu L., Shi W., Long J., et al. A transcriptome-wide association study of 229,000 women identifies new candidate susceptibility genes for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):968–978. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0132-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ko J., Baldassano SN., Loh PL., Kording K., Litt B., Issadore D. Machine learning to detect signatures of disease in liquid biopsies - a user's guide. Lab Chip. 2018;18(3):395–405. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00955k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoo C., Ramirez L., Liuzzi J. Big data analysis using modern statistical and machine learning methods in medicine. Int Neurourol J. 2014;18(2):50–57. doi: 10.5213/inj.2014.18.2.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Havugimana PC., Hu P., Emili A. Protein complexes, big data, machine learning and integrative proteomics: lessons learned over a decade of systematic analysis of protein interaction networks. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(10):845–855. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2017.1374179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sancesario GM., Bernardini S. Alzheimer's disease in the omics era. Clin Biochem. 2018;59:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]