Abstract

Drawing from a person-environment fit framework, we identified profiles of youth in Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) based on the extent to which they received information/resources, socializing/support, and advocacy opportunities in their GSAs and the extent to which this matched what they desired from their GSA along these three functions. Further, we examined profile differences in positive developmental competencies while accounting for community-contextual factors. In a sample of 290 youth from 42 Massachusetts GSAs, latent profile analyses dentified five subgroups. Overall, youth receiving less from their GSAs than they desired, particularly regarding opportunities for advocacy, reported lower levels of self-reflection, bravery, civic engagement, and agency than youth who received information, socializing/support, and advocacy that matched or exceeded what they desired.

Despite sizable social and political progress in the past two decades to support the civil rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations, LGBT youth continue to face considerable adversity. LGBT youth are at disproportionate risk for experiencing deleterious physical and mental health outcomes (Coker, Austin, & Schuster, 2010; Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, 2010; Saewyc, 2011), which are largely a function of experiencing identity-related victimization (Nadal et al., 2011; Russell, Toomey, Ryan, & Diaz, 2014; Saewyc, 2011). In the absence of such victimization, LGBT youth can thrive and achieve positive psychosocial outcomes in adulthood (Russell et al., 2014). Further, heterosexual cisgender allies play an important role in helping to counteract discrimination and to serve as sources of peer support for LGBT youth (Lapointe, 2015). Yet, there is a dearth of literature on programs that promote positive development among LGBT youth and their allies (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2002; Saewyc, 2011).

School-based organizations can provide appropriate contexts to foster positive development competencies, such as self-reflection, agency, bravery, and civic engagement (Mahoney, Larson, & Eccles, 2005; National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2002; Rusk et al., 2013). However, because of their stigmatized identities, LGBT youth may face additional challenges in finding safe contexts for developing these strengths. In this respect, school-based Gay-Straight Alliances (also known as Genders & Sexualities Alliances; GSAs), which are student-led and adult-advised groups for LGBT youth and heterosexual cisgender allies, represent one setting that has the potential to promote positive development among LGBT youth and their allies (Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004). Because they are positioned in schools, GSAs are uniquely situated to provide vital and consistent support to LGBT youth as well as to allies. A number of studies now show that students in schools with GSAs (inclusive of LGBT, heterosexual, and cisgender students) report fewer experiences of school-based victimization, lower depressive symptoms, higher self-esteem, greater college enrollment, and sometimes lower odds of risky substance use behaviors (Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006; Heck, Flentje, & Cochran, 2011; Konishi, Saewyc, Homma, & Poon, 2013; Kosciw, Greytak, Palmer, & Boesen, 2014; Szalacha, 2003; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2011). As the number of GSAs in the United States increases (Kosciw et al., 2014), there is a greater need to understand how to optimize their potential to promote resiliency among their members.

GSAs promote positive developmental competencies through three major functions: providing LGBT-specific information and resources, safe spaces for socializing and receiving social support, and opportunities for advocacy around LGBT and other social justice issues (GLSEN, 2007; Griffin et al., 2004). In the present study we draw from the framework of person-environment fit to consider differences among youth in GSAs according to whether their desire for these functions match what they report receiving from their GSA. To examine potential diversity in patterns of fit between what is desired on one hand, and what is received on the other, we use a person-centered analytic approach. We also investigate potential individual differences, such as along sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity that may be associated with certain patterns of person-environment fit. Further, we consider potential contextual differences based on characteristics of the broader environment in which GSAs are located, including urbanicity, representation of LGBT relationships in the community, the socioeconomic context, and the political context.

GSAs and Person-Environment Fit

The person-environment fit framework posits that optimal outcomes emerge when there is a match between the desires and goals expressed by the individual and the perceived supports and resources available in a setting (Moos & Lemke, 1983). The person-environment fit framework has been previously applied to theorize the ways in which school environments physically, programmatically, and socially institute heteronormativity and homophobia (Chesir-Teran, 2003). As a safe space, GSAs may be a valuable developmental context for LGBT students and allies to find resources and support that may be lacking in the overall school environment. A relevant variant of the person-environment fit framework—stage-development fit (Eccles et al., 1993; Eccles & Midgley, 1989)—further clarifies the importance of examining GSA participant and GSA environment match/mismatch for the optimization of positive developmental competencies. According to stage-development fit, youth whose social environments respond to their changing needs may be more likely to experience positive outcomes. For LGBT youth, adolescence is often a period of onset of identification as a sexual minority and when other sexual orientation milestones (e.g., first same-gender attractions, sexual contact, relationships) are experienced (Calzo, Antonucci, Mays, & Cochran, 2011; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006). For gender minority youth, adolescence is also a period of heightened vulnerability for school-based victimization (McGuire, Johnson, Toomey, & Russell, 2010). The emergence of LGBT identities in adolescence may thus increase exposure to identity-related social stigma and victimization (Meyer, 2003), but also motivate the pursuit of connections with LGBT resources and organizations and opportunities to engage in service and advocacy related to LGBT issues (Kosciw, Palmer, & Kull, 2015). Drawing from the person-environment fit framework, generally, and stage-development fit framework, specifically, LGBT youth may desire more information and resources from their GSAs relative to heterosexual and cisgender youth. In addition, it is possible that youth who report discrepancies between what they desire from their GSA and what they receive (e.g., desiring more opportunities for advocacy than are available from the GSA; desiring more support than the GSA can provide), regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity, will be less likely to experience positive developmental gains.

Thus far, research on GSAs has largely focused on the associations between GSA presence and students’ psychosocial functioning and educational attainment (Goodenow et al., 2006; Heck et al., 2011; Konishi et al., 2013; Kosciw et al., 2014; Szalacha, 2003; Toomey et al., 2011). These studies often speak to the positive role of GSAs, yet associations are sometimes inconsistent across such studies, potentially because simple comparisons of the presence vs. absence of a GSA – or GSA members vs. non-members – mask the variability of GSA experiences for youth involved in them. More recently, studies have examined GSAs with greater nuance by considering how youth, advisor, and structural characteristics relate to variability among members in their experiences and in their wellbeing (Heck, Lindquist, Stewart, Brennan, & Cochran, 2013; Poteat, Calzo, & Yoshikawa, 2016; Poteat, Scheer, Marx, Calzo, & Yoshikawa, 2015; Toomey & Russell, 2011; Watson, Varjas, Meyers, & Graybill, 2010). For example, advisors differ in their training backgrounds and how they approach their roles as advisors (Poteat, Yoshikawa et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2010), and students vary in how they perceive their experiences in the GSA and participate in their GSA (Heck et al., 2013; Poteat, Calzo, et al., 2016; Toomey & Russell, 2011). Recent studies on GSAs within the Massachusetts GSA Network have examined variability in the extent to which GSAs provide socializing and advocacy opportunities, and group- and individual-level factors that contribute to this variability (Blinded for Peer Review, 2015). Additional research within the network has examined factors that predict greater student agency (Blinded for Peer Review, 2016) and level of active engagement in GSAs (Blinded for Peer Review, 2016), GSA advisor self-efficacy to address issues affecting LGB youth of color and transgender youth (Blinded for Peer Review, 2016), GSA member self-efficacy to address issues around race/ethnicity and gender identity (Blinded for Peer Review, in press), and GSAs as a potential setting to discuss diverse health promotion topics (e.g., substance use, mental health, and sexual health; Blinded for Peer Review, 2017). As exemplified by these studies, GSAs are not homogenous, monolithic entities in what they do, nor do all youth members participate in their GSAs in the same way or have the same experiences. Although these studies address the nuanced effects of GSAs on multiple dimensions of positive youth development, such studies have not taken into account what GSA members desire from their GSAs, whether these desires align with what their GSAs offer, and the implications of such alignment for youth development.

Research from the general field of youth development programs suggests that youth participate in organized activities for different reasons and to meet distinct individual needs and preferences (Dawes & Larson, 2011; McLellan & Youniss, 2003). Applied to GSAs, such a perspective suggests that the meaning and effects of GSAs may be illuminated by understanding the fit between the needs and goals young people have for participating in a GSA, and the support and resources they gain from actual participation. For example, the needs and goals of LGBT students in GSAs may differ substantively from members who identify as allies (i.e., heterosexual and heterosexual-cisgender students) based on the need for specific minority identity-related support or sense of affinity. Students who identify as allies may be drawn to GSAs to support fellow classmates, or potentially in alignment with social justice and advocacy aspirations (Goldstein & Davis, 2010; Lapointe, 2015). Although GSAs may offer a range of experiences to meet the different interests of diverse youth, there are a number of barriers and constraints in doing so. For instance, some advisors report facing hostility from school administrators in doing certain activities, or having limited access to time and resources (Watson et al., 2010). Students also often collectively decide on the focus of meetings (Poteat, Yoshikawa et al., 2015), which could lead some youth in the minority to feel that the GSA is not focusing on their particular needs. Given some of these constraints, it is likely that some youth in GSAs may experience a degree of mismatch between the type and level of needs they have regarding their GSAs and what they believe they actually receive from their GSAs.

Potential Differences across Groups of GSA Members

From a program evaluation standpoint, the match or mismatch between individual preferences and the opportunities of a setting are a critical determinant of overall program success (Lerner, 1983; Moos, 1984). In particular, it is possible that this degree of match likely relates to youths’ sense of agency (i.e., confidence in working toward larger goals; Snyder et al., 1996), overall levels of civic engagement, and capacity for critical self-reflection. For example, settings that provide fewer opportunities for advocacy in relation to the level desired by some youth could undermine youths’ development of agency and civic engagement by providing insufficient opportunities for them to build confidence in working towards larger goals, to engage in community service, and connect to social justice or political organizations (Ballard, 2014). GSAs are also positioned to promote self-reflection by facilitating supportive and educational discussions among members related to sexual orientation and gender identity and building critical awareness of systems of oppression as part of advocacy efforts (Marx & Kettrey, 2016; Toomey & Russell, 2011). Thus, GSAs may be best able to enhance youths’ development of self-reflection when the availability of information and educational resources and advocacy opportunities are in-line with members’ levels of information seeking and desires for advocacy.

Identifying correlates of match and mismatch can also provide useful information for identifying youth who may be better served than others within GSAs, and for eventually constructing more responsive GSA-based programming. Correlates may be experiential, such as length of membership duration or number of past experiences of victimization. For example, because of their greater ongoing involvement in the GSA, longer-serving members may report desiring and receiving more information and resources, socializing and support, and opportunities for advocacy than those who more recently joined. Also, students who report experiencing victimization more frequently than others may report a greater desire for information and resources (e.g., for coping strategies), socializing and support (e.g., for peer emotional support), or advocacy (e.g., to promote anti-bullying policies); yet, it is unclear whether members who are more victimized than others perceive their GSAs to match their level of need along these dimensions.

Although GSAs aim to include members from both marginalized and dominant groups (e.g., sexual minority and heterosexual youth, or transgender and cisgender youth) to collectively support one another and counter oppression, this also raises challenges for GSAs to meet the needs of a diverse membership. Thus, correlates of match and mismatch may also be demographic. It would be important to determine if sexual minority members are more likely than heterosexual members to be represented in groups that perceive a match or mismatch between what they desire from the GSA and what they receive from the GSA. Also, in general, there remains limited attention to diversity within young LGBT populations (Del Toro & Yoshikawa, 2016; Mustanski, 2015). There have been calls to determine whether youth settings, including GSAs, adequately meet the needs or capitalize on the strengths of youth from specific marginalized backgrounds (Diaz & Kosciw, 2009; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012; Poteat & Scheer, 2016). For instance, studies have found that youth of color reported feeling less supported in their GSA than white youth (McCready, 2004; Poteat, Yoshikawa et al., 2015). Thus it would be important to note whether youth of color are more likely than White youth to be in groups that represent a mismatch between their desires and what they perceive receiving from their GSA. Similarly, given the range of unique barriers and forms of discrimination faced by transgender youth in schools (Greytak, Kosciw, & Diaz, 2009), it would be important to determine if transgender youth are more likely than cisgender youth to be in groups that represent a mismatch between their desires and what they perceive receiving from their GSA.

Finally, it is also important to situate GSAs (and students’ experiences within them) in the larger contexts of their schools and communities (Kosciw, Greytak, & Diaz, 2009). From a socioecological perspective, school and community-level variables may further shape both the desires of the students for information, socializing, support, and advocacy opportunities, and the capacity of GSAs to deliver on these opportunities. For example, as an extracurricular organization, GSAs in communities with higher poverty levels may encounter difficulties meeting the needs of their students, or providing resources and trainings to staff and teachers (Kosciw et al., 2009). Previous research has found that LGBT youth in rural communities face particularly hostile school climates (Kosciw et al., 2009), which may be attributed to a multitude of factors, including greater political conservatism (Pew Research Center, 2017) and potentially constrained access to LGBT social networks and resources in rural communities (Fisher, Irwin, & Coleman, 2013). By contrast, in communities where LGBT resources may be more available, such as in cities, GSAs can serve as a gateway for students to connect to additional resources (Porta et al., 2017). Taken together, it is possible that the local political context and urbanicity may have a distal effect on person-environment fit for students in GSAs by creating a milieu of social support for LGBT issues and increasing availability of additional resources for LGBT individuals. In addition, as prior research on macro-level indicators of LGBT well-being and health has demonstrated (Hatzenbuehler, 2011), visible indicators of LGBT integration in the local context may also shape the developmental experiences of LGBT youth. For example, prior research has found that greater density of same-gender couples in a school’s district is a protective factor among LGB youth for suicide attempts (Hatzenbuehler, 2011).

Current Study

In order to analyze the complexities of person-environment fit within the GSA context, we use latent profile analysis (LPA; Masyn, 2013; Muthen & Muthen, 2000), a person-centered technique which allows researchers to infer, from observed multivariate data, subgroups that are not directly observable within a population. In this study, we use LPA to identify different subgroups of GSA youth based on the particular combination of their levels of expressed desire across the three main dimensions of GSA functions (information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy) and their perceptions of how much they received from the GSA along these dimensions. Although groups that emerge from LPA are largely based on unobserved patterns within a dataset, and cannot generally be identified a priori, we anticipate that several groups of youth may be evident. First, we expect one group will comprise those who report wanting a high level of information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy, while also reporting that they receive high levels of these provisions from their GSA. We anticipate the emergence of this group because youth program research suggests that some youth in such settings are highly engaged and motivated to be involved in these programs and that they derive substantial benefits from their high engagement, likely because their needs and interests are well met (Fredricks, Hackett, & Bregman, 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Second, we expect another group to emerge on the opposite spectrum, in which they report low desire for information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities from the GSA, as well as report receiving low levels of these from the GSA. We suspect that this category of youth may be present because other studies suggests that some youth join programs for self-serving reasons, some youth are more externally motivated to attend programs, and because some youth may utilize GSAs as one of multiple settings in which they access opportunities and services (e.g., joining a club to spend time with friends or a favorite teacher, or to bolster a resume in preparation for college admissions; Fischer & Theis, 2014; McLellan & Youniss, 2003; Perkins et al., 2007). Third, we anticipate a group of youth who may report high levels of desire for information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities, but who perceive that they do not receive these provisions at a comparable level (i.e., a mismatch between what they desire and what they receive). This group may emerge due to the barriers faced by some GSAs to provide certain resources or opportunities as well as practical constraints for GSAs to meet the diverse needs of all youth. Based on the person-environment fit framework, we anticipate that GSA members who exhibit a mismatch will also report lower levels of positive developmental competencies compared to GSA members who exhibit a match between desired and received GSA functions. Analyses of experiential, demographic, and contextual correlates of subgroups are exploratory, but based on emerging findings in other areas of LGBT youth research, we anticipate potential differences across profiles on these variables.

Method

Participants and Procedure

In collaboration with the Massachusetts GSA Network, we conducted secondary data analyses of 2014 Massachusetts GSA Network statewide survey of GSA members. The network is a joint program of the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth and the Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ Students. It gathers data in an ongoing manner as part of needs assessments, program evaluations, and to identify best practices for GSAs. The data from the 2014 survey were collected at five regional conferences throughout Massachusetts and through postings to GSA advisors on their GSA-based listserv. At the regional conferences, surveys were given during a 15-minute period at the start of the conference. Through the listserv, GSA advisors requested surveys that they then made available to and collected from youth (the surveys were sent to GSAs that had not attended regional conferences). In both cases, youth voluntarily completed an anonymous short survey if their GSA advisor granted adult consent. The GSA Network uses adult consent over parent consent to avoid potential risks of inadvertently outing LGBT youth to parents. This is a common method in LGBT youth research to protect their safety and confidentiality (Mustanski, 2011). Students were told that their responses would be anonymous and that data are used for program evaluation and potentially for research purposes to produce reports or articles. Students who did not want to complete the survey at the conferences were able to do other activities. Students who did not want to complete the survey made available through their GSA advisor could elect not to ask for or pick up a survey from their advisor. We secured IRB approval from [institution masked for review] for our secondary data analysis.

The full sample included 295 youth in 42 GSAs, ranging in age from 13–20 years old. There were 4 youth in 8th Grade, 47 in 9th Grade, 90 in 10th Grade, 95 in 11th Grade, and 55 in 12th Grade; 4 youth did not report their grade level. There were 87 youth who identified as heterosexual, 73 as lesbian or gay, 59 as bisexual, 18 as questioning, and 55 self-reported other sexual orientation identities; 3 youth did not report their sexual orientation. Of the participants, 200 identified as cisgender female, 66 as cisgender male, 9 as genderqueer, 11 as transgender (10 as female to male, 1 as male to female), and 7 self-reported other gender identities; 2 youth did not report their gender. There were 201 youth who identified as White, 32 as biracial or multiracial, 18 as Latino/a, 16 as Asian or Asian American, 16 as Black or African American, 4 as Native American, and 5 self-reported other racial/ethnic identities; 3 youth did not report their race/ethnicity. The average membership duration of youth in their GSA was 1.56 years (SD = 1.22 years).

Measures

GSA functions desired and received.

For each of the three dimensions that characterize the aims and functions of GSAs (providing information and resources, socializing and support opportunities, and advocacy opportunities), participants rated the same set of items both in terms of opportunities or experiences they personally received/did and opportunities or experiences they personally desired overall in their GSAs. Items assessing components that were received were preceded by a question stem asking participants to report the extent to which they personally felt they received or did the described component (“What I get from the GSA”). Conversely, items assessing components desired were preceded by a question stem asking participants to report how much they desired the described component (“What I need/want from the GSA”). In both cases, response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot).

Youth reported the amount of information and resources they received and desired from their GSA across three items: (a) Receive training on diversity issues; (b) Receive resources on services available; (c) Learn ways to deal with stress (αReceived=0.84; αDesired=0.87). Youth reported the amount of socializing and support they received and desired from their GSA across seven items: (a) A place of safety; (b) Emotional support; (c) Validation and reassurance; (d) A place where I share any concerns; (e) Hang out with others; (f) Just be myself with others; and, (g) Meet new people or make new friends (αReceived=0.90; αDesired=0.97). Youth reported the amount of advocacy they had done and advocacy opportunities desired from their GSA across seven items: (a) Organize school events to build awareness of LGBT issues; (b) Educate those not in the GSA on diversity issues; (c) Give presentations about LGBT issues outside of our GSA; (d) Do advocacy events in the community; (e) Work with other student groups on diversity issues; (f) Speak out for LGBT issues; (g) Speak out for other minority group issues (αDone=0.87; αDesired=0.96).

Positive developmental competencies.

Indicators of positive developmental competencies included self-reflection, bravery, civic engagement, and agency. Self-reflection was assessed with 7 items from the Self-Reflection and Insight Scale for Youth (e.g., “I often think about how I feel about things”; Sauter, Heyne, Blote, van Widenfelt, & Westenberg, 2010). Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher average scale scores represent higher levels of self-reflection (α=0.93). Participants’ bravery was assessed with the 6 item measure from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; e.g., “I take frequent stands in the face of strong opposition”; Goldberg, 1999; Goldberg et al., 2006). Response options ranged from 1 (very inaccurate) to 5 (very accurate), with higher average scores across the items representing greater bravery (α=0.86). Participants indicated their level of civic engagement on the 6-item participatory citizenship scale (e.g., “I work with groups to solve problems in my community”; Flanagan, Syverstsen, & Stout, 2007), with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and higher average scores indicating greater civic engagement (α=0.93). Agency was assessed using the six-item State Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1996) that assesses agency and pathways to achieving goals (e.g., “If I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to get out of it;” “At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals”), with response options ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 8 (definitely true). Higher average scale scores represent greater sense of agency (α=0.91).

Victimization.

Participants reported past-month experiences of victimization by responding to 7 items describing potential incidents of victimization (e.g., In the last 30 days I got picked on, made fun of, or teased by others), with response options of 0 times, 1–2 times, 3–4 times, 5–6 times, and 7 or more times (scaled 0 to 4; α=0.86).

Membership duration was measured as the number of months and/or years participants had been involved in their GSA. We converted responses to be expressed as a continuous variable in the number of years.

Demographics.

Youth reported their grade (8th-12th), sexual orientation, gender identity, and their race/ethnicity. Sexual orientation response options were: lesbian or gay, bisexual, questioning, heterosexual, or other write-in responses (write-in responses represented non-heterosexual identities such as pansexual or queer). Gender identity response options were: male, female, transgender (male to female), transgender (female to male), gender-queer, or other write-in responses. Because of the limited number of youth represented in the specific transgender, gender-queer, and other write-in responses, we considered them together in a transgender/genderqueer group for our analyses (write-in responses were largely reflective of genderqueer identities such as gender fluid or non-binary/pangender). Race/ethnicity response options were: Asian/Asian American, Black or African American, Latino/a, Native American, White (non-Hispanic), bi/multiracial, or other write-in responses. We dichotomized the responses as white or racial/ethnic minority youth because of the limited number of youth represented in each specific racial/ethnic minority group.

Structural indicators.

An indicator of socioeconomic status of the overall school was measured as the percentage of students who qualify for free (or reduced-price) lunch, as indicated by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Second Education (Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2018). Urbanicity of the school was coded as urban, suburban, and rural based on urban-centric locale codes provided by the National Center on Education Statistics (National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). Liberal voting patterns for the local voting precincts where each school was located were scored as the percentage of voters who voted democrat in the 2014 Massachusetts gubernatorial election, drawing from election results from the state election results database (Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2018). Finally, an approximate measure of the sexual minority adult population in the school district area was measured using the density (per 1000 adults) living in same-gender partnered households in the county. This value was calculated by the Williams Institute utilizing 2010 US Census Data and 2011–2013 American Community Survey data (The Williams Institute - UCLA School of Law, 2016).

Analysis

To identify groups of individuals with similar response patterns for what youth reported wanting or needing and doing along the three dimensions of GSA functions, latent profile analysis (LPA) models were estimated in Mplus with the mean information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy variables as indicators. Missing data on LPA indicators were accounted for using full-information maximum likelihood, assuming missing-at-random, in Mplus. While accounting for the clustering of participants within GSAs, two- to seven-latent profile solutions were estimated during the profile enumeration process to determine the optimal number of groups. The final group solution was selected based on: (1) substantive relevance (Marsh, Hau, & Grayson, 2005; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthen, 2007); (2) embodiment of homogeneity (i.e., strong characterization of a group based on item response) and separation (i.e., item response distinguishes subgroups; Collins & Lanza, 2010); and (3) recommended LPA fit statistics, including the log-likelihood (LL) value, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ration test (LMR-LRT; Kass & Wasserman, 1995; Masyn, 2013). Following the recommendations of Masyn (2013), BIC values were used to calculate the correct model probability (cmP). Greater LL values, lower BIC values, significant LMR-LRT values, and cmP values closer to 1 indicate better model fit. After identifying the final group solution, groups were first compared on demographic and experiential covariates (sexual orientation, gender identity, racial/ethnic background, membership duration, victimization experiences), structural indicators, and then on positive developmental competencies using the 3-step approach in Mplus. The 3-step approach in Mplus conducts overall Wald Chi-Square tests for the equality of the distribution of categorical covariates and the equality of means for continuous covariates, as well as post-hoc pair-wise comparisons (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2014).

Results

Class Enumeration

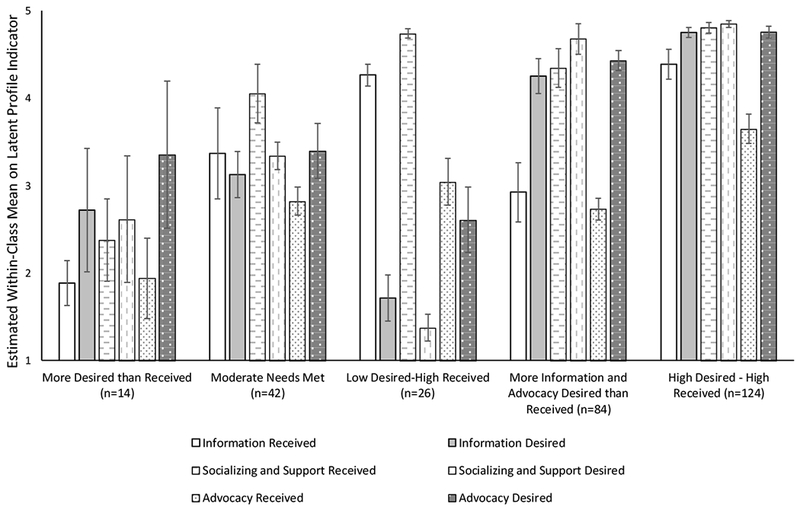

After dropping participants who were missing data on all latent profile indicators (n=5), the analysis sample consisted of 290 participants. Demographic descriptive statistics for the analysis sample are provided in Table 1. The BIC continued to decrease and the BLRT p remained significant throughout subsequent class estimation models. Although multiple class enumeration fit statistics did not converge on a similar profile solution, the class enumeration process evaluated solutions based on substantive relevance, homogeneity, and separation of classes. In contrasting the 4- and 5-profile solutions, the 5-profile solution contributed substantively relevant separation between classes with regards to potential person-environment fit that was not observed in the 6- and 7-profile solutions (which yielded additional profiles that differed modestly in mean responses on items). Based on these comparisons, as well as the diminishing decrements on the BIC values, and the clear correct model probability score (Table 2), the class enumeration process generally supported the 5-profile solution. As displayed in Figure 1, the estimated within- and between-profile means for each indicator were clearly distinguished, thus providing evidence of separation and homogeneity. With regard to substantive relevance, the patterns were highly interpretable and consistent with likely configurations of match and mismatch in person-environment fit. The largest group was the High Desired-High Received group (n=124), whose members exhibited consistently high levels of desired and received information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities from their GSA. The High Desired-High Received group was similar to the Moderate Needs Met group (n=42) in that both groups exhibited a desire for advocacy that exceeded the advocacy opportunities they received from their GSAs, but it was different from the Moderate Needs Met group in that participants in the Moderate Needs Met group generally reported receiving information and resources and opportunities to socialize and receive support that matched or exceeded what they desired. The remaining three groups exhibited large discrepancies between what they desired and received from their GSAs. Participants in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group (n=84) exhibited high overall desire and receipt of socializing and support, yet also desire for information and resources and advocacy opportunities that differed vastly from what they reported receiving from their GSAs. Participants in the Low Desired-High Received group (n=26) overall reported receiving more information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities relative to what they desired from their GSAs. Last, participants in the smallest group—More Desired than Received (n=14)—reported desiring more information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities relative to what they received from their GSAs.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Variables

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GSA Functions

(Range: 1=not at all, to 5=a lot) |

||||

| Information Received | 3.68 | 1.05 | ||

| Information Desired | 3.95 | 1.14 | ||

| Socializing/Support Received | 4.46 | 0.67 | ||

| Socializing/Support Desired | 4.13 | 1.17 | ||

| Advocacy Received | 3.12 | 0.96 | ||

| Advocacy Desired | 4.20 | 0.99 | ||

| Positive Youth Competencies | ||||

| Self-Reflection (Range: 1=Strongly disagree to 6=Strongly agree) | 4.43 | 1.27 | ||

| Bravery (Range: 1=Very inaccurate to 5=Very accurate) | 3.46 | 0.96 | ||

| Civic Engagement (Range: 1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) | 2.97 | 1.03 | ||

| Agency (Range: 1=Definitely false to 8=Definitely true) | 5.04 | 1.69 | ||

| Victimization (Range 0=0 times in past mo. to 4=7+ times in past mo.) | 0.54 | 0.72 | ||

| Membership Duration (Years) | 1.56 | 1.22 | ||

| Demographics | n | % | ||

| Grade Level | ||||

| 8th | 3 | 1.0 | ||

| 9th | 46 | 16.1 | ||

| 10th | 88 | 30.8 | ||

| 11th | 94 | 32.9 | ||

| 12th | 55 | 19.2 | ||

| Racial/Ethnic Minority Identity | 90 | 31.4 | ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 87 | 29.5 | ||

| Lesbian/Gay | 73 | 24.7 | ||

| Bisexual | 59 | 20.0 | ||

| Questioning | 18 | 6.1 | ||

| Other Identity | 55 | 18.6 | ||

| Sex and Gender Identity | ||||

| Cisgender Female | 200 | 67.8 | ||

| Cisgender Male | 66 | 22.4 | ||

| Transgender MTF | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Transgender FTM | 10 | 3.4 | ||

| Genderqueer, or other identity | 16 | 5.5 | ||

| Structural Indicators | ||||

| Students Eligible for Free Lunch at School | 31.2 | |||

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Urban | 24 | 8.3 | ||

| Suburban | 249 | 85.9 | ||

| Rural | 17 | 5.9 | ||

| Liberal Voting Pattern | 53.5 | |||

| Same-Gender Households (Density per 1000) | 8.08 | 3.66 |

Note. Descriptive statistics are reported for participant demographics, victimization experiences, and Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) functions received and desired, and positive developmental competencies. Analysis sample n=290. Structural indicators: Urbanicity was coded at the level of the school and assigned to each student. Proportion students eligible for free lunch is reported at the level of the school and represents the overall average across schools in the sample. Liberal voting pattern represents percentages voting democrat in the 2014 Massachusetts gubernatorial election within the voting precinct of the school. Same-gender households represents the density per 1000 adults in same-gender households in the county of the school. More details can be found in the Method.

Table 2.

Class Enumeration Fit Statistics

| Classes | Free parameters | LL | BIC | cmP | LMR-LRT p | BLRT p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | −2168.51 | 4405.048 | 0.00 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 19 | −1928.63 | 3964.988 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 26 | −1817.17 | 3781.758 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 33 | −1745.03 | 3677.172 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 40 | −1705.61 | 3638.014 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 47 | −1670.13 | 3606.752 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| 7 | 54 | −1636.93 | 3580.023 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00 |

Note. Fit statistics are for the analysis of information, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities received and desired from GSAs. The chosen solution is in bold. LL=Log-likelihood; BIC=Bayesian Information Value; cmP=Correct Model Probability; LMR-LRT p= significance value from Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test, and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) p value.

Figure 1.

Estimated within-profile means (1= not at all, 5= a lot) and standard errors for information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy desired and received.

Group Differences in Positive Developmental Competencies

As displayed in Table 3, participants in the More Desired than Received group reported the lowest average scores on self-reflection, bravery, and civic engagement. By contrast, participants in the Low Desired-High Received and High Desired-High Received groups reported the highest bravery, civic engagement, and agency scores. These results are generally consistent with the expectation that match or fulfillment between what is desired and what is available in a setting can lead to optimal outcomes. Further reinforcing person-environment fit expectations, participants in the Moderate Needs Met and More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received groups—two groups that exhibited both match and mismatch between desire and receipt for GSA support functions—generally scored between the More Desired than Received and the High Desired-High-Received groups in these indicators of positive developmental competencies.

Table 3.

Profile Differences in Positive Developmental Competencies, Demographics, Victimization, and GSA Membership Duration

| Latent Profile | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | More Desired than Received (n=14) (a) | Moderate Needs Met (n=42) (b) | Low Desired-High Received (n=26) (c) | More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received (n=84) (d) | High Desired–High Received (n=124) (e) | Overall Wald Test of Equality | Post-Hoc Latent Profile Contrast (p < 0.05 level) |

| Positive Dev. Competencies (M[SE]) | |||||||

| Self-Reflection | 2.83 (0.33) | 4.29 (0.20) | 4.53 (0.22) | 4.23 (0.14) | 4.80 (0.10) | 39.93, p<0.001 | a < bcd, e; d < e |

| Bravery | 2.52 (0.23) | 3.27 (0.15) | 3.75 (0.16) | 3.17 (0.10) | 3.79 (0.08) | 46.29, p<0.001 | a < bd < ce |

| Civic Engagement | 2.00 (0.21) | 2.53 (0.15) | 3.02 (0.19) | 2.81 (0.11) | 3.36 (0.09) | 50.84, p<0.001 | a < bd, cd < ce |

| Agency | 4.01 (0.44) | 4.74 (0.25) | 5.34 (0.32) | 4.71 (0.17) | 5.55 (0.16) | 21.76, p<0.001 | abd < ce |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Grade Level (M[SE]) | 10.42 (0.27) | 10.41 (0.16) | 10.21 (0.19) | 10.56 (0.11) | 10.64 (0.09) | 4.97, p=0.290 | |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority (Prob[SE]) | 0.56 (0.14) | 0.39 (0.10) | 0.50 (0.11) | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.31 (0.05) | 13.16, p=0.011 | ac> d |

| Sexual Minority (Prob[SE]) | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 0.56 (0.15) | 0.40 (0.10) | 0.46 (0.10) | 0.21 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.04) | 10.80, p=0.029 | ac > de |

| Lesbian or Gay | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.21 (0.08) | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.29 (0.06) | 0.29 (0.05) | 4.29, p=0.368 | |

| Bisexual | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.25 (0.11) | 0.17 (0.23) | 0.18 (0.27) | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.58, p=0.965 | |

| Questioning | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.03) | 19.23, p=0.001 | a < de |

| Other | 0.08 (0.10) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.20 (0.05) | 5.278, p=0.260 | |

| Sex (Male) (Prob[SE]) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.27 (0.08) | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.31 (0.05) | 77.84, p<0.001 | a < bce, d; d < e |

| Trans. or Genderqueer (Prob[SE]) | 0.09 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.23 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.12 (0.04) | 30.37, p<0.001 | b < ce |

| Victimization (M[SE]) | 0.65 (0.23) | 0.48 (0.10) | 0.55 (0.14) | 0.49 (0.07) | 0.60 (0.08) | 1.84, p=0.766 | |

| Yrs. of GSA Membership (M[SE]) | 1.40 (0.32) | 1.51 (0.19) | 0.70 (0.14) | 1.65 (0.13) | 1.74 (0.12) | 37.07, p<0.001 | c < abde |

| Structural Indicators | |||||||

| Free Lunch Eligible (Prob [SE]) | 0.22 (0.04) | 0.33 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.04) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.02) | 6.43, p=0.169 | |

| Urbanicity | |||||||

| Urban (Prob [SE]) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.18 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.03) | 25.11, p<0.001 | a < be |

| Suburban (Prob [SE]) | 0.86 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.07) | 0.97 (0.04) | 0.91 (0.04) | 0.84 (0.04) | 8.46, p=0.076 | |

| Rural (Prob [SE]) | 0.15 (0.10) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.03) | 17.94, p=0.001 | c < e |

| Liberal Voting Pattern (Prob [SE]) | 0.52 (0.03) | 0.51 (0.02) | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.55 (0.01) | 7.95, p=0.094 | |

| Same-Gender Households (M[SE]) | 9.27 (1.24) | 8.26 (0.59) | 7.52 (0.55) | 8.55 (0.45) | 7.73 (0.30) | 4.34, p=0.362 | |

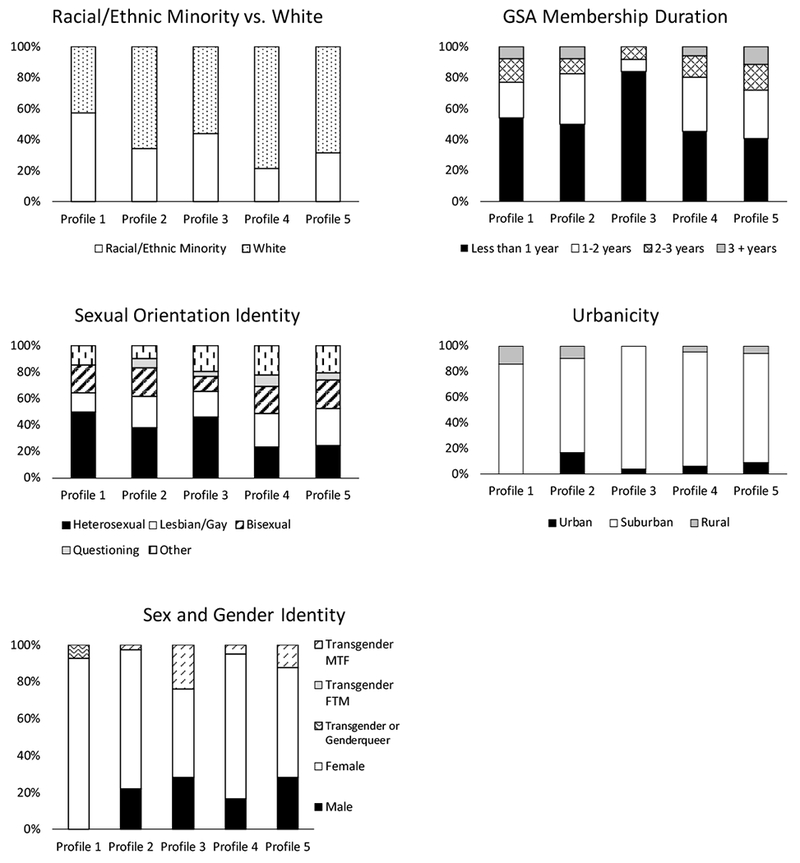

Correlates of Profile Membership

As displayed in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 3, the groups differed along several demographic and experiential dimensions. Participants in the More Desired than Received and Low Desired-High Received group had a higher probability of identifying as a racial/ethnic minority than participants in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group. Participants in the More Desired than Received and Low Desired-High Received groups also had a higher probability than those in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group of self-identifying as heterosexual. Participants in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received and High Desired-High Received groups had higher probability than those in the More Desired than Received group of self-identifying as questioning their sexual orientation. There were no cisgender males in the More Desired than Received group, and no transgender/genderqueer individuals in the Moderate Needs Met group. Participants in the Low Desired-High Received group had the lowest average number of years of GSA membership duration.

Figure 2.

Significant within-profile student characteristics and structural indicators. Profile 1= More Desired than Received (n=14); Profile 2= Moderate Needs Met (n=42); Profile 3= Low Desired-High Received (n=26); Profile 4= More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received (n=84); Profile 5= High Desired-High Received (n=124).

With regards to structural indicators, the proportions of students in the school eligible for free or reduced price lunch, liberal voting patterns in the school’s voting precinct, and county-level density of adults living in same-gender households were not associated with latent profile membership. However, urbanicity was associated with profile membership, such that participants in the More Desired than Received group had a lower probability of living in an urban region relative to participants in the Moderate Needs Met and High Desired-High Received groups. As reflected in Figure 2, all of the students in the More Desired than Received group resided in either suburban or rural communities. No participants in the Low Desired-High Received group resided in rural communities (Table 3; Figure 2).

Ancillary analyses on the sexual minority subsample.

Covariate analyses revealed sexual orientation differences in the probability of belonging to different latent profiles. Although GSAs are meant to be inclusive of both sexual and gender minority students and heterosexual and cisgender allies, the motivations that sexual and gender minority students have for joining GSAs may differ substantively from heterosexual and heterosexual-cisgender allies. For example, youth who currently identify as heterosexual and heterosexual-cisgender allies may join GSAs primarily for advocacy reasons or to support sexual and gender minority peers (Lapointe, 2015; Scheer & Poteat, 2016), and thus the degree to which they report desiring or receiving GSA-specific opportunities may differ from sexual and gender minority students. Thus, we conducted an ancillary analysis to examine whether five profiles could be identified after excluding the 87 heterosexual participants, and whether these profiles would resemble the structures of match-mismatch in person-environment fit identified in the original analysis. Results from the ancillary analysis (available upon request from the authors) supported a 5-profile solution with nearly identical configurations of person-environment match-mismatch as the profiles extracted when LPA was conducted on the overall sample.

Discussion

Previous research on GSAs as supportive developmental contexts for LGBT youth has focused on the effects of overall exposure vs. no exposure. However, from a person-environment fit perspective, the match between the desires and goals expressed by individual members and the perceived supports and resources received from a setting is a critical determinant of successful outcomes. This match may be particularly important for marginalized populations in the few settings where they may receive support for their needs, such as GSAs for LGBT populations and their allies (Chesir-Teran, 1993). This study examined the extent to which the availability of information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy opportunities matched the desires of GSA members along these functions, and whether variation in this person-environment fit were associated with positive developmental competencies. One pattern of match and four patterns of mismatch were detected in the data. These groups differed in their composition along dimensions of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and number of years of membership duration. Profiles also differed with regards to urbanicity, reflecting the possible implications of the larger community in which youth, GSAs, and schools are situated for impacting person-environment fit. Furthermore, we identified differences in positive developmental competencies based on youths’ group membership. GSA members who reported desiring more from their GSA than they received, particularly regarding opportunities for advocacy, reported lower levels of self-reflection, bravery, civic engagement, and agency than youth who received information, socializing/support, and advocacy that matched or exceeded what they desired. The findings emphasize the importance of taking into account the desires of GSA members for information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy as well as the extent to which GSAs meet these needs in order to facilitate optimal development.

One of the anticipated groups that emerged from our analyses was the High Desired-High Received group, which was the largest subgroup in the sample. We anticipated the emergence of this group based on findings among other youth programs suggesting that some students are highly motivated and engaged within certain youth programs (Fredricks et al., 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2010). Within GSAs, this group of students could represent those who have had their needs and interests met, yet continue to establish new interests and goals in the context of the GSA or in light of emergent civic engagement and social advocacy. Consistent with this interpretation, members of this profile reported the highest scores on the positive developmental competencies. In addition, although this group generally scored high on receiving all GSA functions, the group indicated desiring more advocacy than they received. With regards to other characteristics, members of this profile group tended to be longer-involved GSA members, and they were more likely to identify as transgender or genderqueer, or to identify their sexual orientation as questioning relative to members of other groups. Consistent with stage-development fit frameworks, it is possible that members in this group find their GSAs an ideal match for their current advocacy and identity development-related needs.

The person-centered analysis also identified four patterns of mismatch that are of substantive relevance. Perhaps of principal importance is the More Desired than Received group, whose members exhibited an overall pattern of disparity between what they desired in their GSAs and what they received across all three GSA functions. Although a small group, this group stood in sharp contrast to the others, with its members reporting lower self-reflection, bravery, civic engagement, and agency scores than members of other groups. More research is required to understand and more richly characterize this group of GSA members, whose desires for information and resources, socializing and support, and advocacy may be unfulfilled. The demographic and experiential data analyzed in the current study provided some insights into potential characteristics of this profile, with members of this subgroup having a high probability of identifying as a cisgender female, as a racial/ethnic minority, and as heterosexual relative to members of the other groups. The disparities reported by GSA members in this subgroup may be a reflection of encounters or perceptions of exclusion that these members experience in their GSAs (e.g., gender-based harassment; insufficient opportunities to advocate as cisgender allies or heterosexual allies). For example, prior research has found that racial/ethnic minority youth report feeling less supported in their GSAs than white youth (McCready, 2004; Poteat, Yoshikawa et al., 2015). Unfortunately, the current data do not provide opportunities for a deeper examination of these potential interpretations. By drawing contrast to the High Desired-High Received group, the results for the More Desired than Received group provide further support for the importance of taking into account person-environment fit in examining variability in how GSAs adequately meet the needs and interests of youth from different backgrounds. Given the discrepancy between their strong desire for resources and perceptions of receiving few of these resources, it may be critical for GSAs to identify more effective ways to fully meet the needs and interests of this group of youth in order to capitalize on the strong motivation of these students to be active and contributing GSA members.

In contrast to the More Desired than Received group, the Low Desired-High Received group exhibited an overall pattern of reporting greater levels of received than desired resources, most notably receiving high levels of socializing and support opportunities from their GSA. Members of this group were more likely than the High Desired-High Received group to self-identify as heterosexual, had the shortest average membership duration in the sample, and yet had comparable probability of identifying as transgender/genderqueer as participants in the High Desired-High Received group. Possible interpretations of this profile are that this subgroup includes new GSA members (e.g., who join out of curiosity and interest), heterosexual allies (i.e., who may not need LGBT-specific resources, yet nonetheless benefit from GSA functions), and GSA members whose acute social and/or support needs are met by the GSA. Despite reporting low desire for information and resources, socializing and support opportunities, and advocacy opportunities from the GSA, members of the Low-Desired-High Received group exhibited similar levels of bravery, civic engagement, and agency as members in the High Desired-High Received group. Findings from other studies suggest that some GSA members become less involved in their GSA over time as their needs are met (Poteat et al., 2015). Given their high positive developmental competencies, yet possible tendency for short membership, identifying ways to increase the membership duration of members who fit the Low Desired-High Received profile may be beneficial to GSAs.

The final two groups to emerge were the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group and Moderate Needs Met group, which were the second and third largest subgroups, respectively. Both groups were similar to the High Desired-High Received group with regard to desiring more advocacy relative to what they perceived their GSAs as providing. Although both groups reported higher positive developmental competencies than the More Desired than Received group, they scored lower on all developmental competencies than the High Desired-High Received group, thus suggesting the need for additional research to understand and explore ways to address these forms of mismatch in person-environment fit in GSAs. Prior research indicates that GSA members may become more interested or motivated to participate in advocacy opportunities after having information and socializing and support needs fulfilled (Poteat et al., 2015). In turn, engagement in GSA advocacy opportunities can be a powerful behavioral context for developing positive developmental competencies, such as agency, bravery, and civic engagement. Members in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group could represent GSA members who are in GSAs that are providing adequate support, but have limited informational resources or opportunities to engage in advocacy. Approximately 29% of the participants were in the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received Group. Given the large discrepancy in desired and received information and advocacy opportunities, and their lower positive developmental competencies compared to the High Desired-High Received group, it appears that GSAs that focus primarily on providing a space for socializing and social support may be devoting less attention to important motivations and potential sources of prosocial growth among their members. The Moderate Needs Met group may represent participants with lower overall interest and motivation to engage with GSA functions relative to the High Desire-High Received group. Nevertheless, given their higher desire for advocacy relative to what they receive, it is possible that improvements in person-environment fit can potentially manifest in enhanced positive developmental competencies. For both the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group and Moderate Needs Met group, increasing opportunities to engage in advocacy, such as through organizing school events to build awareness of LGBT issues, could lead to positive shifts in developmental competencies. Although both groups indicate adequate opportunities to engage in socializing and support in GSAs, the More Information and Advocacy Desired than Received group also indicated a desire for more information, which includes learning about diversity issues, methods to cope with stress, and ways to access resources and services. Advisor and student-led advocacy trainings could also include components centered on working with other student and community groups on diversity issues, coalition building, and creating asset maps, which can further enhance prosocial development among GSA members.

Drawing from socioecological frameworks, structural indicators, such as global assessments of the socioeconomic status of students in the school, political voting patterns in the local district, and proportion of same-gender couples in the region (a proxy for potential LGB population) also were expected to be associated with the degree to which students expressed needs for resources, or degree to which GSAs could provide opportunities to meet student needs. However, most of these factors were not significantly associated with profile membership. It is possible the these structural indicators, particularly voting patterns and proportion of same-gender couples, are too distal to the school-based experiences of adolescents, or less relevant (relative to mental and behavioral health outcomes) to outcomes such as information-seeking, socializing and support, and advocacy. The only structural indicator that emerged as a significant factor was urbanicity, with results highlighting that no participants in the More Desired than Received group reside in urban areas, and no participants in the Low Desired-High Received group reside in rural areas. From a person-environment fit perspective, one possible interpretation is that urban areas provide additional resources for LGBT youth beyond those available in the school context. Prior research has indicated that greater rurality is associated with greater exposure to hostile school contexts (Kosciw et al., 2009), which is somewhat consistent with the More Desired that Received group pattern. GSAs can also serve as a facilitator of connections to other resources for students (Eisenberg et al., 2018; Porta et al., 2017); in settings with few resources (e.g., suburban or rural areas with few LGBT-specific agencies or social settings), this may not be so helpful. However, in resource rich settings, such as may be the case in some cities, this networking capacity of GSAs can be of benefit. Consistent with this possible interpretation, both the Moderate Needs Met group and High Desired-High Received group had high proportions of students in urban areas.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Research

There are several limitations of this study to note. First, data are cross-sectional; thus, it is difficult to determine directionality of effects. For example, the self-report pattern of the Low Desired-High Received group could be interpreted as youth who have received abundant support in the face of no need for support (i.e., many resources, but no need for them), or youth who have had their earlier support needs satisfied. In addition, longitudinal research could help to determine whether the positive developmental competencies examined in this study, such as civic engagement, are actually factors that motivate some youth to become members of GSAs, rather than direct outcomes of GSA person-environment fit. It is possible that there could be a reciprocal causal effect between GSA involvement and these variables. Furthermore, whereas person-environment fit research often relies upon multiple sources of information to measure environment, this study utilized single-source (i.e., participant report) measures of environment. The low number of racial/ethnic minority youth prevented us from examining potentially relevant subgroup differences in GSA experiences. Similarly, although 87 participants identified as heterosexual, the sample was not of sufficient size to fully examine relevant similarities or differences in latent profiles across sexual orientation beyond the covariate analysis. Future researchers may consider recruiting a larger sample of heterosexual and heterosexual-cisgender allies—who represent core subgroups within GSAs—to enable rigorous testing of multiple forms of latent profile similarity, such as configural (number of profiles) and structural aspects (Morin, Meyer, Creusier, & Bietry, 2016). Participants were recruited from regional meetings from the Massachusetts GSA Network, and thus their experiences may not be generalizable to GSA youth across the state or youth from other states where the sociopolitical climate may differ and where GSAs may not be as connected with one another. For instance, there may be a proportionally greater number of youth in the More Desired than Received profile in states or regions with greater hostility toward GSAs or in schools with fewer resources available to GSAs. Despite these limitations, notable strengths of the study include its application of the person-environment fit approach to understanding GSA-based experiences in relation to positive youth competencies among LGBT and ally youth, the focus on resiliency rather than pathology, and the application of LPA to examine person-environment fit patterns.

The study findings have several implications for future research and GSA practice. With regards to research, longitudinal and mixed method studies are required to further explore the directionality of effects. Multi-source and multilevel analyses can further contextualize and distinguish profiles from one another (e.g., whether certain profiles are more likely to emerge in rural vs. urban settings or based on the sociopolitical climate of the school district), as well as investigate the roles of peers and advisors in ensuring that GSAs can flexibly meet the various needs and interests of youth members to promote an optimal match between members’ needs and interests and what they receive from the GSA. Youth who perceived a discrepancy between what was offered in the GSA and what they needed, which could be construed as a position of deficit, reported the lowest levels of positive developmental competencies in the sample. The findings indicate the importance for GSA advisors and peer leaders to conduct needs assessments among members and to strategize on ways of meeting these needs throughout the course of the school year. Beyond practices such as weekly check-ins, understanding the motivations of students can help advisors and peer leaders tailor the GSA experience to meet the diverse desires for information, socializing and support, and advocacy for their members. In addition, relevant demographic and experiential differences emerged indicating that advisors and peer leaders may consider focusing on particular groups of GSA members or aspects of the GSA experience beyond those identified in a needs assessment in order to maximize positive youth development. For example, desire for advocacy appears to be associated with longer membership in the GSA, whereas youth who reported being in a GSA for fewer years indicated that their desires for advocacy, information and resources, and socializing and support were small relative to what they received from their GSAs. Longitudinal research will be an important next step for unpacking how GSAs address acute and emerging information, socializing and support, and advocacy needs among their members.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health grants R01MD009458 (Poteat) and K01DA034753 (Calzo).

References

- Asparouhov T, & Muthen B (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21(3), 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard PJ (2014). What motivates youth civic involvement? Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(4), 439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Antonucci TC, Mays VM, & Cochran SD (2011). Retrospective recall of sexual orientation identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1658–1673. 10.1037/a0025508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesir-Teran D (2003). Conceptualizing and assessing heterosexism in high schools: A setting-level approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(3–4), 267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ESK, Poteat VP, Yoshikawa H, & Calzo JP (in press). Fostering youth self-efficacy to address transgender and racial diversity issues: The role of gay–straight alliances. School Psychology Quarterly. 10.1037/spq0000258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Austin SB, & Schuster MA (2010). The health and health care of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 457–477. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Del Toro J, & Yoshikawa H (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative and qualitative research in psychology. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 347–350. 10.1177/0361684316655768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz EM, & Kosciw JG (2009). Shared Differences: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Students of Color in Our Nation’s Schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Midgley C (1989). Stage-environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for adolescents. In Ames C & Ames R (Eds.), Research on Motivation in Education (pp. 13–44). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, Buchanan CM, Reuman D, Flanagan C, & Mac Iver D (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101. 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Mehus CJ, Saewyc EM, Corliss HL, Gower AL, Sullivan R, & Porta CM (2018). Helping Young People Stay Afloat: A Qualitative Study of Community Resources and Supports for LGBTQ Adolescents in the United States and Canada. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(8), 969–989. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1364944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N, & Theis D (2014). Extracurricular participation and the development of school attachment and learning goal orientation: the impact of school quality. Developmental Psychology, 50(6), 1788–1793. 10.1037/a0036705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM, Irwin JA, & Coleman JD (2013). LGBT Health in the Midlands: A Rural/Urban Comparison of Basic Health Indicators. J Homosex. 10.1080/00918369.2014.872487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan C, Syverstsen A, & Stout M (2007). Civic measurement models: tapping adolescents’ civic engagement. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Hackett K, & Bregman A (2010). Participation in Boys and Girls Club: motivation and stage environment fit. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3), 369–385. 10.1002/jcop.20369 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN. (2007). Gay-Straight Alliances: Creating safer schools for LGBT students and their allies. New York, NY. Retrieved from http://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/Gay-StraightAlliances.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, & Ostendorf F (Eds.), Personality Psychology in Europe (pp. 7–28). Tilberg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L, Johnson J, Eber H, Hogan R, MC A, Cloninger C, & HG G (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84–96. 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SB, & Davis DS (2010). Heterosexual allies: a descriptive profile. Equity & Excellence in Education, 43(4), 478–494. 10.1080/10665684.2010.505464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Szalacha LA, & Westheimer K (2006). School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43(5), 573–589. 10.1002/pits.20173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Lee C, Waugh J, & Beyer C (2004). Describing roles that gay-straight alliances play in schools: from individual support to social change. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education, 1, 7–22. 10.1300/J367v01n03_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2011). The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127(5), 896–903. 10.1542/peds.2010-3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Flentje A, & Cochran BN (2011). Offsetting risks: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(2), 161–174. 10.1037/a0023226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Lindquist LM, Stewart BT, Brennan C, & Cochran BN (2013). To Join or Not to Join: Gay-Straight Student Alliances and the High School Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youths. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 25(1), 77–101. 10.1080/10538720.2012.751764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, & McNair R (2010). Substance abuse and mental health disparities: comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Soc Sci Med, 71(4), 824–831. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, & Wasserman L (1995). A reference Bayesian test for nested hypotheses and its relationship to the Schwarz criterion. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(434), 928–934. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi C, Saewyc E, Homma Y, & Poon C (2013). Population-level evaluation of school-based interventions to prevent problem substance use among gay, lesbian and bisexual adolescents in Canada. Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 929–33. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, & Diaz EM (2009). Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 976–988. 10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, & Boesen MJ (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, & Kull RM (2015). Reflecting resiliency: openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1–2), 167–178. 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe AA (2015). Standing “Straight” Up to Homophobia: Straight Allies’ Involvement in GSAs. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(2), 144–169. 10.1080/19361653.2014.969867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (1983). A “goodness of fit” model of person-context interaction. In Human Development: An Interactional Perspective (pp. 279–294). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL, Larson RW, & Eccles JS (2005). Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Retrieved from http://ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2005-01368-000&site=ehost-live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, & Grayson D (2005). Goodness of fit evaluation in structural equation modeling. In Maydeu-Olivares & McArdle J (Eds.), Contemporary Psychometrics. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Marx RA, & Kettrey HH (2016). Gay-straight alliances are associated with lower levels of school-based victimization of LGBTQ+ youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1269–1282. 10.1007/s10964-016-0501-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2018). School and District Profiles. Retrieved May 3, 2018, from http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Masyn KE (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In Little TD (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 551–611). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCready L (2004). Some challenges facing queer youth programs in urban high schools: racial segregation and de-normalizing whiteness. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 1(3), 37–51. 10.1300/J367v01n03_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, Johnson CA, Toomey RB, & Russell ST (2010). School climate for transgender youth: a mixed method investigation of student experiences and school responses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1175–1188. 10.1007/s10964-010-9540-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan JA, & Youniss J (2003). Two systems of youth service: determinants of voluntary and required youth community service. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 47–58. 10.1023/A:1021032407300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1984). Context and coping: toward a unifying conceptual framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 12, 5–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, & Lemke S (1983). Assessing and improving social-ecological settings. In Seidman E (Ed.), Handbook of Social Intervention (pp. 143–162). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Morin AJS, Meyer JP, Creusier J, & Bietry F (2016). Multi-group analysis of similarity in latent profile solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 231–254. 10.1177/1094428115621148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B (2015). Future directions in research on sexual minority adolescent mental, behavioral, and sexual health. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 44(1), 204–19. 10.1080/15374416.2014.982756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, & Muthen LK (2000). Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Analyses: Growth Mixture Modeling With Latent Trajectory Classes. ALCOHOLISM: CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH, 24(6), 882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Wong Y, Issa M-A, Meterko V, Leon J, & Wideman M (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(1), 21–46. 10.1080/15538605.2011.554606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2006). Exhibit A: NCES’s urban-centric locale categories, released in 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2018, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2007/ruraled/exhibit_a.asp [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council, & Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. (Eccles JS& Gootman JA, Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthen B (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. 10.1080/1070551070157396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D, Borden L, Villarruel F, Carelton-Hug A, Stone M, & Keith J (2007). Participation in structured youth programs: why ethnic minority urban youth choose to participate or not to participate. Youth & Society, 38, 420–442. 10.1177/0044118X06295051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2017). The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider. Retrieved from http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/10/05162647/10-05-2017-Political-landscape-release.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Porta CM, Singer E, Mehus CJ, Gower AL, Saewyc E, Fredkove W, & Eisenberg ME (2017). LGBTQ Youth’s Views on Gay-Straight Alliances: Building Community, Providing Gateways, and Representing Safety and Support. Journal of School Health, 87(7), 489–497. 10.1111/josh.12517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Calzo JP, & Yoshikawa H (2016). Promoting Youth Agency Through Dimensions of Gay-Straight Alliance Involvement and Conditions that Maximize Associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 10.1007/s10964-016-0421-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Heck NC, Yoshikawa H, & Calzo JP (2016). Greater Engagement Among Members of Gay-Straight Alliances: Individual and Structural Contributors. American Educational Research Journal, 53(6), 1732–1758. 10.3102/0002831216674804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Heck NC, Yoshikawa H, & Calzo JP (2017). Gay-Straight Alliances as settings to discuss health topics: individual and group factors associated with substance use, mental health, and sexual health discussions. Health Education Research, 32(3), 258–268. 10.1093/her/cyx044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]